- Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

Historical records and material culture of professional merchant organizations, including merchant guilds, provide important insights into their activities, hierarchies, and signifiers of membership. As historical examples indicate, signifiers of membership are common in cross-cultural examples of merchant guilds, and frequently include emblems inscribed on jewelry and personal objects. These guilds frequently worshiped supernatural patrons, which were commonly inscribed on membership signifiers such as rings, tokens, or cards. This article argues that the pochteca of the Aztec imperial era meets the historical definition of a guild as a self-organized, membership-based group, and reflects many of the same organizing principles observed for Medieval/Renaissance guilds in Europe. Many of the characteristics of the pochteca can also be used to identify earlier merchant organizations where written records are scarce or lacking. This article argues that copper anthropomorphic face rings depicting merchant deities emerged as signifiers for professional merchants among the Late Classic and Early Postclassic Maya of eastern Chiapas and Guatemala, many of whom held elite status, and were subsequently popularized among professional merchants in many other areas of Mesoamerica by the Late Postclassic period.

Introduction

Ancient Mesoamerica was politically and economically diverse, cross-cut by trade networks of varying scales, where independent kingdoms negotiated complex relationships with emerging expansionist empires and confederacies (Blanton and Fargher, 2012; Masson and Peraza Lope, 2014; Nichols, 2017; Smith and Berdan, 2003). Although interest in commercial economies of ancient Mesoamerica is longstanding (Blom, 1932; Berdan, 1980; Feinman and Garraty, 2010; Feldman, 1978; Foias and Bishop, 1997; Hirth, 1978; Lee and Navarrete, 1978; Navarrete, 1978; Piña Chan, 1978), there has been a flurry of recent scholarly attention on topics such as market institutions (Blanton and Fargher, 2012), market exchange (Barnard, 2021; Eppich and Freidel, 2015; Hirth, 1998; Masson and Freidel, 2012), market areas (Garraty, 2009; Ossa, 2021; Smith, 2010; Stark and Ossa, 2010), commercial networks from local to interregional scales (Clayton, 2021; Golitko et al., 2012; Feinman and Nicholas, 2010; Kepecs et al., 1994; Minc, 2006; Paris, 2008; Paris et al., 2023; Reents-Budet and Bishop, 2012; Sabloff and Rathje, 1975; Smith, 1974; Smith, 2010, 2015, 2021; Smith and Berdan, 2003; Whitecotton, 1992), currency and token use (Baron, 2018; Masson and Freidel, 2012; Paris, 2021) and marketplaces (Anaya Hernández et al., 2021; Cap, 2015a, 2015b, 2021; Chase and Chase, 2014; Chase et al., 2015; Dahlin et al., 2007, 2010; Feinman and Garraty, 2010; Hirth, 2009; Jones, 2015; King, 2015, 2021; Linares and Bye, 2016; Masson and Peraza Lope, 2014; Ruhl et al., 2018; Shaw, 2012; Terry et al., 2015), to name a few. While there has been a lengthy delay in recognizing ancient Mesoamerican market exchange compared to Old World societies (King, 2015; Masson, 2021), their archaeological identification has important implications for broader understandings of political economies, trade networks, occupational specialization, and social inequality in this region.

One of the thorniest problems in studies of ancient Mesoamerican commerce is the identification of merchants in the archaeological record, as well as how to best understand their professional organization. In contrast to ancient Mesopotamia, where names of merchants, accounts of commercial transactions, and laws governing trade are abundant in cuneiform documents (Garfinkle, 2010), explicit discussions or depictions of commerce are extremely rare in the written traditions of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. The bulk of evidence mostly derives from Spanish Contact or Early Colonial historical accounts, especially the Florentine Codex, a sixteenth-century encyclopedia of Central Mexican history, tradition, and culture, which devotes an entire book to the pochteca, professional merchants of the Aztec Empire (Sahagún, 1954, 1959, 1961). I argue, following suggestions by other scholars (Berdan, 1975, 1980, 1992; Garraty, 2006; Smith, 2015, 2021, cf. Hirth, 2016, p. 193), that the Aztec pochteca has many of the cross-cultural characteristics of a merchant guild, and that similarly to many other historical examples of guilds, they used signifiers to indicate status. Identifying the cross-cultural characteristics of historical guilds, and the degree to which they were expressed by the Aztec pochteca, allows us to systematically investigate earlier merchant organizations elsewhere in Mesoamerica, including the Maya area, and the degree to which they may also share those characteristics.

The identification and analysis of archaeological evidence for merchant signifiers can provide an important perspective on professional merchant activities where historical records are scarce or absent. While archaeological patterns of commercial activity within cities or regions can be identified through the Distributional Approach and other statistical techniques (Hirth, 1998; see also Barnard, 2021; Garraty, 2009; Golitko et al., 2012; Stark and Ossa, 2010), the identification of merchants themselves has proven extremely difficult. The rare cases where archaeologists have identified merchants are typically burials, either containing skeletal remains with specific physiological characteristics (McCafferty, 2021; Rodríguez Pérez et al., 2024), and/or ceramic vessels depicting merchant gods (Rodríguez Pérez et al., 2024; Smith and Kidder, 1951). While evidence for marketplace exchange in both Central Mexico and the Maya area significantly predates the formation of the Triple Alliance (Clayton, 2021; Hirth, 1998, 2009; Masson and Freidel, 2012), the origins of formal merchant organizations are fairly murky across Mesoamerica.

In this article, I argue that copper anthropomorphic face rings from Postclassic period sites portray merchant deities, and represent signifiers used by professional merchants. This idea was originally proposed by Warwick Bray (1977, p. 381), who called the rings ‘Aztec face rings’ or matzatzaztli after the term used in the Florentine Codex (Sahagún, 1959). Since the publication of Bray’s (1977) chapter, numerous other examples of anthropomorphic face rings have been archaeologically identified, including at least 18 examples from the Maya area, many of which are from Early Postclassic period sites in eastern Chiapas and highland Guatemala (Figure 1). These rings depict Mesoamerican merchant deities, including Ek Chuah from the Maya area, and Yacatecuhtli from Central Mexico. I suggest that these artifacts may have been commissioned by elite merchants, taking advantage of the expansion of copper alloy commodities and technologies during the Early Postclassic period.

Figure 1. Map of the Yucatan Peninsula, with selected sites mentioned in the text (drafted by the author from basemap by Sémhur, available from Wikimedia commons, CC BY-SA-3.0).

In this paper, I suggest that anthropomorphic face rings served as signifiers for professional merchants in highland Chiapas and Guatemala during the Early Postclassic period (900–1250 CE). This suggestion rests on four arguments:

1. Merchant guild signifiers are historically common in cross-cultural examples of guilds, and frequently include emblems inscribed on jewelry and personal objects.

2. Supernatural patrons of guilds are frequently incorporated into guild emblems.

3. The pochteca of the Aztec imperial era meets the historical definition of a guild as a self-organized, membership-based group, and reflects many of the same organizing principles observed for Medieval/Renaissance guilds in Europe.

4. Copper anthropomorphic face rings depicting merchant deities served as signifiers for professional merchants in Mesoamerica during the Early Postclassic period, many of whom held elite status.

While not all merchant or artisan organizations in the ancient world are best labeled as guilds, a comparative examination of merchant guilds can allow us to better identify guilds and similar professional merchant associations in contexts with limited historical records, including earlier time periods where written records may be scarce or absent, as well as material signifiers of their operation.

The characteristics of guilds and guild organization in the historical and archaeological record

The word ‘guild’ has had a number of meanings over the centuries, but is particularly associated with the historical associations of merchants or craftspersons in Medieval/Renaissance Europe (Casson, 2019). The word derives from Middle English gilde, from Old Norse gildi meaning ‘payment’ (Merriam-Webster, 2024). The emphasis on payment or dues as a condition of guild membership informs one modern definition of a guild as “an association of individuals formed for a common purpose, using a subscription model of membership” (Hunt and Murray, 1999, p. 34–5).

Scholars have argued for different definitions of historical ‘guilds’ that are more or less inclusive of applications of the term beyond Western contexts. Casson (2019, p. 159) argues that guilds may be differentiated by their primary function: religious observance, social interaction, or trade promotion; she focuses on guilds whose function is on trade promotion, and defines two principal types: merchant guilds and artisan guilds. Grafe and Gelderblom (2010, p. 481) use a fairly inclusive definition of merchants’ guilds as “more or less formally organized groups of long-distance wholesale traders.” Hirth (2016) follows Epstein’s (1991, p. 62) definition of guilds as “voluntary associations with membership based on mutual commercial interest” and argues that the defining characteristic of a guild is self-organization.

Scholarly debates are ongoing regarding the application of the term ‘guild’ to ancient and/or non-Western contexts. Mendelsohn (1940, p. 18) famously applied a guild organization framework to his studies of the Near East, arguing for the existence of craft and merchant guilds as far back as the Third Dynasty of Ur (ca. 2112–2004 BCE), as well as artisan guilds associated with high-skill crafts, such as ivory carving and metallurgical production in ancient Palestine. Other scholars have been less eager to use the label of ‘guild,’ particularly where less formal organizational structures are identified or inferred. For example, Lapidus (1984, p. 95–107) suggests that formal guilds were absent from medieval Islamic cities such as Damascus, arguing that informal trade organizations did not perform the same range of functions as guilds in medieval Europe. Similarly, in China, Moll-Murata (2008) proposes that while merchant networks and organizations of craft and manufacturing producers existed in China from at least the mid fourteenth century, they may not actually constitute ‘guilds’ as not all of them had formal regulations or were recognized by other institutions. For Central Mexico, Hirth (2009, p. 43 2016, p. 235) argues that Aztec pochteca merchants and Epiclassic artisans were not guilds as known from Medieval Europe, instead constituting clan-based corporate communities.

One might reasonably question, what is the utility of considering non-Western merchant or craft organizations as guilds, rather than as something else? Plenty of other terms exist for formal and informal economic organizations: communities of practice, kin networks, trust networks, professions, clubs, trade associations, businesses, and/or caravans (Curtin, 1984; Hanagan and Tilly, 2010; Wenger, 1998). I suggest that the term ‘guild’ is useful because the analogical exercise facilitates scholars’ ability to empirically investigate the material traces of self-organizing professions in the archaeological and historical record. Epstein’s (1991, p. 62) definition of guilds is applicable to ancient and/or non-Western contexts so long as we are able to recognize that guild structure may be difficult to distinguish from other commercial organizations in regions with spotty historical records; that guild organization may change over time; that archaeological signifiers of guild membership should be interpreted within the context of a particular culture; and that the self-organizing aspect of guilds may be difficult to detect archaeologically where historical records are scarce, absent, or incomplete.

Guilds and guild membership are only useful as cross-cultural concepts to the degree that we can see beyond a singular set of historical cases as ‘real’ guilds. Even in Europe where the term ‘guild’ originated, guilds varied between countries and over time. With these caveats in mind, I suggest that there are three characteristics of guilds that set them apart from other economic communities or associations. In addition to these three characteristics, I list several others that are common among historical examples of guilds, but may vary cross-culturally.

1. Formal organization, usually with a ranking system. A formal organizational structure is one of the most distinguishing features of guilds compared to informal groups such as communities of practice or trust networks. The head of the guild often held a special title (Mendelsohn, 1940, p. 19) and had specific responsibilities such as managing membership and conducting quality control inspections. Guilds in the ancient Near East had a chief officer, who sometimes also served as ‘chief magistrate’ for the locality (Mendelsohn, 1940, p. 19). Guilds in medieval Europe had an internal ranking system, with officials who were elected on an annual basis, and the ranks included criteria of age and/or experience (Casson, 2019). To qualify for full membership, prospective young artisans or merchants could be required to complete a formal apprenticeship with an established guild member such as a master craftsman (Casson, 2019, p. 159; Epstein, 1998).

2. Formal membership, usually contingent on the practice of a particular occupation (or craft) as a condition of inclusion. Most scholars identify membership as a key defining feature of guilds, where membership is granted by the guild and kept track of in an organized fashion (which may, but does not necessarily involve, signifiers, tokens, and/or written records). Membership may involve linguistic structures that allow a person participating in a guild to adopt a particular title or label, which is also widely recognized by the community (Mendelsohn, 1940, p. 18).

3. Signifiers of membership. In Medieval and Renaissance Europe, guild signifiers were often formal, visible, elaborate emblems such as coats of arms, incorporated into architecture and decorative arts, flags, certificates, cards, and small metal badges; these symbols could also be visibly displayed during processions or public celebrations (De Francesco, 1938, p. 427). Signet rings bearing merchant’s marks were particularly popular; in addition to serving as visible signifiers of membership, they could also be used to mark imported or exported goods that had been inspected by guild members (De Francesco, 1938, p. 460). The possession and use of these symbols was often heavily policed by the guilds themselves, as guild membership often conferred not only prestige, but material benefits (see below). The guild could threaten to repossess membership signifiers if the guild member did not fulfill their obligations (such as dues; Smethurst and Devine, 1981, p. 84). Non-material signifiers could include coded language and rites, such as passwords, handshakes, and guild-specific vocabularies (De Francesco, 1938).

Signifiers of membership were often displayed during rites of passage, including baptisms and funerals. De Francesco (1938, p. 431) states that “Every stage of life was regulated, and marked for all to see by the emblems of the guild”. In Late Medieval Florence, coffins were decorated with costly renderings of guild emblems; members of the guild bore a fellow members’ coffin to the guild; and all members of the guild had to be present at the funeral of a fellow member (De Francesco, 1938, p. 431).

The following characteristics are often recognized in comparative historical literature on guilds, but typically vary cross-culturally and based on historical context:

4. A tendency towards monopoly and restrictions on membership. As self-organized entities, guild members have historically had considerable discretion over membership criteria, and the ability to maintain monopolies over certain professions. For the period of the Second Commonwealth in ancient Palestine, Mendelsohn (1940, p. 19) specifies that “The residents of an alley can prevent one another from bringing in a tailor, or a tanner, or a teacher, or any other craftsman;” that “the wool-weavers and the dyers are permitted to form a partnership to buy up what-ever goods come to town.” In 1582 CE, the English Company of Merchant Adventurers in Antwerp achieved a monopoly to the point that they could exclude other merchants from participating in the cloth trade, preventing benefits from accruing to ‘free riders’ (Grafe and Gelderblom, 2010, p. 491). While modern guilds are typically open to all who meet membership criteria and are punctual with their dues, modern professional guilds such as SAG-AFTRA specify that working non-union jobs does not count towards meeting membership requirements, and that prospective members must provide proof of three days of employment as a performer, broadcaster or recording artist under a performer’s union in order to qualify (SAG-AFTRA, 2024).

In Medieval/Renaissance Europe, artisan guilds typically had elaborate systems of apprenticeship (Epstein, 1998). These guilds had established systems where apprentices and journeymen provided labor in exchange for learning skills and a craft, typically required for seven years before they were allowed to join the guild (ibid, p. 691). The restriction allowed the guild to exert control over membership, and restricted the ability of skilled journeymen to strike out on their own before a master craftsmen was able to recuperate the costs of room, board and training. In cases where the apprentice was not a family member, their father would typically seek out a master craftsman to request the apprenticeship, and the arrangements sometimes required an entry fee paid to the master craftsman, as well as a formal contract (ibid, p. 691).

5. Internal regulations governing the behavior of members. De Francesco (1938, p. 430), writing about European guilds in the Late Middle Ages, writes, “From birth until the hour of death the child of a guild member had to bow to the laws of the community, and obey their rules, in return for which he enjoyed all the protective privileges which the guild could confer.” In some cases, laws were created to protect trade secrets from non-members; these laws could be quite extreme. De Francesco (1938, p. 446) cites a 1539 CE law in the city of Lucca (Tuscany), “according to which any Lucchese who discovered a countryman abroad spinning silk or showing how it should be spun was to kill him on the spot, the price paid for the traitor’s head being 50 ducats.”

6. Membership services. One of the inducements for merchants or artisans to join a guild was due to the services they provided (Casson, 2019, p. 163). In the case of European guilds, these membership services were in direct compensation for payment of a member’s annual dues. These services included access to both social and financial capital. Casson (2019) outlines several types of membership services, including trade networks, infrastructure (often providing traveling members with food and lodging), training and quality control, social welfare for sick or injured members, and funeral expenses. Medieval guilds in central Europe provided mutual aid in case of disease and robbery, and even provided the first fire insurance (Allemeyer, 2007). In 18th and 19th century Britain and Ireland, membership tokens for trade unions were effectively used as passports within traveling and tramping systems; when unemployed members traveled in search of work, membership badges could be presented at the local union and in exchange, they could receive cash benefits, hospitality, and possibly even employment (Smethurst and Devine, 1981, p. 84).

7. A legal relationship with, and operation in tandem with, political structures. The relationships between guilds and local political rulers were historically quite variable. Grafe and Gelderblom (2010, p. 478) argue that because merchants often crossed political boundaries, they were historically unlikely to rely simply on the protective services and infrastructure provided by a single ruler or municipality; however, a guild’s members were still geographically situated, and constrained by local political systems. While some merchant and artisan guilds had contentious relationships with local political authorities, members of guild leadership often served as intermediaries, and could influence rulers to create favorable laws and policies (Casson, 2019; Grafe and Gelderblom, 2010).

8. Supernatural patronage. European guilds in the Late Middle Ages often had patron saints. Many British guilds founded in the 15th century were initially founded as religious fraternities that gradually changed their emphasis to economic activities (Smethurst and Devine, 1981, p. 163). Many of the patron saints for artisan guilds were depicted on signifiers for the guild, including medals or tokens (De Francesco, 1938, p. 430). For example, the 16th century medal of the tailor’s guild of Milan features the Madonna and child on one side, while the 17th century medal of the cloth-makers guild of Milan depicts St. Ambrose, patron saint of the city of Milan, holding a bolt of cloth in one hand (De Francesco, 1938, p. 433). Similarly, the Merchant Taylors’ Company of late 15th century England used symbolic attributes of John the Baptist in all of its guild emblems (De Francesco, 1938, p. 456).

9. Internal specialization in particular products or services. Casson (2019, p. 159) argues that merchant guilds, in particular, have historically been involved in the coordination of long-distance supply chains. She argues that within a merchant guild, some members were responsible for organizing internal supply chains within countries, while others were responsible for external connections with broader exchange networks. She observes that many merchant guilds specialized in particular high-demand items, which could include raw materials (wool from England; dyestuffs from France; spices from Asia) and/or finished products (wine from France, tapestries from Flanders).

10. Spatially-concentrated stores, workshops, and/or residences. Casson (2019, p. 159) suggests that historically, guilds were centered on a town or city and tended to possess a clear urban identity, even if the scope of their activities meant travel elsewhere. De Francesco (1938, p. 432) notes that in Late Medieval Europe, guild members’ workshops were typically located along the same urban street. Many cities also had a formal guild hall for each guild; they would also typically have a hostel for traveling guild members, which in smaller towns was shared by several different guilds (ibid). During the Second Commonwealth in ancient Palestine (ca. 516 BCE – 70 CE), the city of Jerusalem supported separate quarters for butchers, leather-workers, wool-dealers, and dyers, each with their own synagogues, social institutions, and cemeteries (Mendelsohn, 1940, p. 18).

It is also important to recognize that guilds were not static organizations with stable relationships to the political systems in which they were enmeshed. Historically, many merchant organizations changed in structure and membership with increased access to power and wealth (Grafe and Gelderblom, 2010, p. 478). De Francesco (1938, p. 426) emphasizes that in the late Middle Ages, guild rules and regulations were intended to serve as a protection against all arbitrary measures, from whatever side they might come; however, “at a later period, when the economic structure changed, the guilds and their members became powerful, and they who had once sought refuge in numbers were now a threat to others.” Similarly, Howell (2009) demonstrates how women were excluded from late Medieval guilds over time in northwestern Europe.

The Pochteca and the Postclassic period Mesoamerican economy

At Spanish contact, the term pochteca (also spelled puchteca) was applied to specific professional merchants operating in tandem with the Aztec Empire. The Aztec imperial economy is one of the most extensively studied economic systems in the Americas, thanks in great part to the abundance of historical period documents, including accounts of Spanish observers, Indigenous historians, and the archaeological record (see Smith, 2015). From humble beginnings, the Mexica emerged as formidable mercenaries, then established Tenochtitlan as one of many expansionist city-states in the Basin of Mexico, which then positioned them as the most powerful member of the Triple Alliance (ca. 1428 CE; Durán, 1994). By Spanish Contact (1519 CE), Tenochtitlan was the capital city of an intercultural empire that included over 200,000 residents, and over several million subjects in the empire at large (Smith, 2015, p. 72).

The Aztec imperial economy was a complex system that included commercial exchange, regular taxation on provinces, a gift tribute system, conquest-state taxation, land taxes, rotational labor taxes, various types of labor taxes (corvée labor for public works, labor by youths, labor in the houses of the Tenochca elite), and market taxes (Berdan, 1975, 1980, 1992; Berdan and Anawalt, 1992; Berdan and de Durand-Forest, 1980; Berdan et al., 2014; Blanton, 1996; Garraty, 2006; Hirth, 2016; Millhauser and Overholtzer, 2020; Smith, 2004, 2010, 2014, 2015, 2021). It did not operate in isolation, but as part of a world-system in Postclassic Mesoamerica, with exchange networks that cross-cut different states, confederacies and empires (Blanton and Feinman, 1984; Feinman and Garraty, 2010; Feinman and Nicholas, 2010; Kepecs et al., 1994; Paris, 2008; Smith and Berdan, 2003; Whitecotton, 1992). Broader analyses of the Aztec imperial economy have been detailed in these earlier works.

Among the many documents describing the Aztec economy, the Florentine Codex provides an exceptional level of detail, particularly Book 9: The Merchants (Sahagún, 1959). The Florentine Codex was authored by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, a Spanish Franciscan friar, together with Mexica authors who were principally his current and former students at the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco (Nicholson, 2002). The fact that Sahagún’s informants were from Tlatelolco gave them significant insight into the pochteca history and inner workings. Sahagún’s project began in 1545 CE, meaning that his informants were less than a generation removed from the events of the Spanish Conquest. The pochteca are also described in a variety of other histories (Durán, 1994; Zorita, 1963), including the Codex Ixtlilxochitl (Durand-Forest, 1976) and Codex Magliabechiano (1970).

The pochteca were not the first merchants in Central Mexico, nor were they the first long-distance merchants in Mesoamerica. Prior to the founding of the Triple Alliance in 1428 CE, Central Mexico supported a complex network of independent (and competitive) polities that supported commercial exchange through a dynamic system of periodic marketplaces hosted in small urban capitals (Minc, 2006; Smith, 1987, 2010, 2015). According to Lockhart (1992, p. 192), the two principal terms for professional merchants, pochtecatl [merchant] literally translates to ‘inhabitant of Pochtlan’ (Azcapotzalco; northwest Basin of Mexico) and oztomecatl [vanguard merchant] means ‘inhabitant of Oztoman’ ([Oztuma], Guerrero; Tarascan frontier), suggesting that the terms were first applied to specific groups that were famous for trading activities, and lost their ethnic connotation over time.

The Florentine Codex claims that the pochteca were founded under the first ruler (tlatoani) of Tlatelolco (Sahagún, 1959). Tlatelolco was founded by a dissident group of Mexica who split from Tenochtitlan (estimated around 1331 CE; Berdan and Anawalt, 1992, p. 32) and were reincorporated into the Aztec Empire as a tributary province following the loss of a war with Tenochtitlan in 1473 CE (Durán, 1994, p. 249–262). Following Tlatelolco’s defeat, Tenochtitlan installed a military governor, and the pochteca became subject to Aztec imperial authority, and the case of the vanguard merchants, were charged with obtaining merchandise directly on behalf of the Aztec emperor (Sahagún, 1959, p. 3). According to Durán (1994, p. 262), the Tlatelolco merchants were also required to collect a ‘tax amounting to one part for every five [20%] sold in the marketplace for the Tenochca lords.’

The Pochteca as a guild

In evaluating the Aztec pochteca as a guild, we can consider their description based on existing historical records, iconography and the archaeological record (see also Berdan, 1975, p. 148).

A formal organization, usually with a ranking system; specialization in particular products or services

The pochteca were a formal organization of professional merchants with a clearly defined ranking system, outlined in detail by Sahagún and his informants in Book 9 (Sahagún, 1959, p. 12–13, 22, 23, 24, 27) and Book 10 (Sahagún, 1961, p. 59–61). Sahagún Book 10 (Sahagún, 1961, p. 59) describes six categories, starting with the general term for a merchant (puchtecatl; [pochtecatl]) and then defining five ranks or specializations including principal merchants (puchtecatzintli puchteca tlailotlac or puchtecatlatoque), vanguard merchants (oztomecatl), slave dealers (tecoani), slave bathers (tealtiani) and exchange dealers (tlaptlac or teucuitlapatlac). All of the descriptions of these ranks or specializations include the term pochteca, suggesting that the term pochteca forms an umbrella term or category. Vanguard merchants are described as conducting official diplomatic trade missions that focused primarily on luxury gift exchanges with the leaders of allied foreign cities and ports of trade, and held a monopoly over certain types of diplomatic missions (Sahagún, 1959, p. 12). Book 9 (Sahagún, 1959, p. 21) describes an additional category of disguised merchants (naoaloztomecatl); linguistically, this suggests that they existed as sub-category of vanguard merchants. Disguised merchants entered areas outside Aztec imperial political control or alliance, such as Zinacantan in highland Chiapas, to trade in rare commodities (ibid, p. 21). Slave dealers and slave bathers conducted ceremonies that are reported in considerable detail (ibid, p. 45–49). The exchange dealer is explicitly described as a merchant in Book 10 (in tlapatlac ca puchtecatl), and the description suggests that this particular role was associated with monitoring and enforcing standardized counts, weights and measures of goods in the marketplace (Sahagún, 1961, p. 62).

The pochteca were high-ranking commoners, operating within the broader systems of social class and political ranking of Aztec society. The Aztec Empire defined two principal social classes of nobility (pipiltin) and commoners (macehualtin) with several sub-ranks; nearly all pochteca members were free commoners, but held higher status than peasants (tlalmaitl or mayeque) and enslaved people (tlacotin; Berdan, 1975, p. 38). The vanguard merchants were awarded symbols of privilege by Emperor Ahuitzotl, including gold and amber lip plugs and rabbit fur capes, but only wore them on feast days to avoid arousing the ire of the hereditary nobility. On rare occasions, merchants became wealthy enough to acquire a position as teuctli [lord] or marry the daughter of a tlatoani (provincial ruler; Lockhart, 1992, note 33). Pochteca carefully managed their own internal rankings; during feasts, members were seated in rank order; principal merchants, disguised merchants, spying merchants in warlike places, those who bathed slaves, and the slave dealers, with the youths at the end (Sahagún, 1959, p. 13).

In the Florentine Codex Book 10, being a merchant (pochtecatl) or vanguard merchant (oztomecatl) is linguistically distinguished from other types and scales of commercial activity. The term tlanecuilo has been translated as ‘retailer’ (Anderson and Dibble, 1961) or ‘regional merchant’ (Nichols, 2017, p. 25), and the term tlacemanqui is used for a ‘retailer who sells in single lots’ (Anderson and Dibble, 1961). Neither term is included in the lists of ranks of pochteca merchants in either Book 9 or 10. A broader umbrella term of ‘seller’ is used by Sahagún (1961) throughout Book 10 using the suffix “-namacac” (e.g., cacaoanamacac) which is translated as “[thing]-seller” (e.g., cacao-seller). Forty-five separate sellers are listed in Book 10, including everything from the greenstone seller (chalchiuhnamacac) to the tortilla seller (tlaxcalnamacac) to the prostitute (monamacac). The suffix - namacac appears to be an action-based descriptor that can apply to individuals of any professional rank or category: ordinary pochteca (such as the feather-seller), vanguard merchant (cacao seller), producer-seller (obsidian seller), or a regional merchant (cotton seller). For example, the cacao seller is described as “a cacao owner, an owner of cacao fields, an owner of cacao trees; or a vanguard merchant [oztomecatl], a traveler with merchandise [tlaotlatoctiani; lit. Transporter of wares], a traveler [tlanenemiti; lit. a person who walks around] or retailer who sells in single lots [tlanecuilo]” (ibid, p. 65). By this logic, a variety of people could sell cacao, including vanguard merchants, but not all ‘cacao-sellers’ were vanguard merchants (Sahagún, 1961).

Membership, usually contingent on the practice of a particular occupation (or craft) as a condition of inclusion; restrictions on membership

Membership within the pochteca was contingent on being a professional merchant. The pochteca as a formal organization expanded from its origins in Tlatelolco to include twelve cities (including Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco), all located in the Basin of Mexico (Figure 2; Sahagún, 1959, p. 49). Of these, only members of the pochteca from five cities (Tenochtitlan, Tlatelolco, Uitzilopochco [Huitzilopochco, now Churubusco], Azcapotzalco, and Quauhtitlan) could achieve the rank of vanguard merchant (ibid, p. 17). Some of the high-skill artisans in the Aztec Empire that are also mentioned Book 9 could also be argued to be members of craft guilds, including copperworkers, goldworkers, and lapidaries (Sahagún, 1959). Within the cities of Tlatelolco, Tenochtitlan and Texcoco, merchants and high-skill artisans lived in exclusive barrios (Sahagún, 1959, p. 12; Durand-Forest 1976, Vol. I, p. 326–7).

Figure 2. Map of Central Mexico, with selected sites mentioned in the text (drafted by the author from basemap by Sémhur, available from Wikimedia commons, CC BY-SA-3.0).

Notably, Sahagún (1959), Book 9, p. 16) specifically mentions merchant women [pochtecacioa, lit. ‘lady-merchant’], indicating that both men and women were allowed to be members within the guild; however, he specifies that women were not allowed to be vanguard merchants. A specialized group of pochteca women served as bathers of slaves for specific sacrificial ceremonies (see below).

Following Sahagún, the pochteca qualify as self-organized, with the ability to accept or decline new members via voluntary apprenticeship, and also to internally regulate their own members (c.f. Hirth, 2016). Sahagún (1959), Book 9, p. 14) explicitly specifies that Aztec parents could request apprenticeship for their child to be trained as a member of the pochteca, and that on the journeys of the vanguard merchants, “some were to go for the first time; perchance they were yet young boys whose mothers [and] fathers had [the merchants] take with them,” and that this type of apprenticeship was explicitly requested by the parents “quite on their own account” (ibid, p. 14). Among the apprentices, there was also internal ranking, with one apprentice “who would go as the leader of the youths” who was responsible for organizing:

“… all the loads of merchandise, all the consignments, the possessions of the principal merchants, and the goods of the merchant women, were arranged separately … and they assembled all the travel rations, the pinole … and when they had assembled indeed all the loads, they thereupon arranged them on the carrying frames; they set one each on the hired burden-carriers to carry on their backs; not very heavy, they put only a limited amount … those who were going for the first time, the small boys, they … placed upon their backs only the drinking vessels, the gourds” (ibid, p. 14-15).

This assertion directly contradicts claims from Alonso de Zorita, a royal commissioner in Guatemala and Mexico from 1548 to 1565 CE, that membership in the pochteca was exclusively hereditary. He writes, “Merchants … belonged to recognized lineages, and no man could be a merchant save by inheritance or by permission of the ruler (1963, p. 181). In both Aztec imperial Central Mexico (Berdan and Anawalt, 1992) and Late Medieval European artisanal production (De Francesco, 1938), it was very common for children to be trained in their parents’ professions and become members of the same guild. Ultimately, these are conflicting historical accounts. While Sahagún’s Tlatelolco-based informants undoubtedly have a very specific perspective, their knowledge of the pochteca’s inner workings was likely more nuanced that that of Zorita, an outside observer. The descriptions of parental solicitation and apprenticeship are detailed, and there is no obvious motivation for Sahagún’s informants to fabricate them.

A legal relationship with, and operation in tandem with, political structures

The vanguard merchants played a particularly significant role in completing trade missions on behalf of the Aztec Emperor, which also included gift exchanges to cement political alliances with foreign rulers. Cities that are specifically mentioned include Ayotlan and Coatzaqualco [Coatzacoalcos; coastal Veracruz], as well as Cimatlan [Cimatán, just west of Villahermosa] and Xicalanco [coastal Tabasco] (Sahagún, 1959, p. 17–18). The items traded by vanguard merchants are listed in detail, and specified as the specific property of Emperor Ahuitzotl. Once the vanguard merchants returned to Tenochtitlan, they delivered the items straight to the emperor’s palace (ibid, p. 18). Similarly, when the disguised merchants returned from trade missions, they reported first to the principal merchants, and then the principal merchants led them before the emperor to report their observations directly (ibid, p. 23). Zorita (1963, p. 134) states that the killing of a merchant was considered cause for war.

Internal regulations governing the behavior of members

Merchants had some degree of self-governance within their own ranks, and also over the marketplace spaces where they held authority. Principal merchants presided as judges over the marketplace, pronouncing judgments on deceitful vendors or thieves, and establishing regulations and pricing for everything in the marketplace (Sahagún, 1959, p. 24). Principal merchants also passed judgement on their own members who transgressed: “A merchant, a vanguard merchant, who did wrong, they did not take to someone else; the principal merchants, the disguised merchants, themselves alone passed judgment, executed the death penalty” (ibid.). The death penalty was imposed on any vanguard merchant who ‘misused a woman’ (ibid.). The principal merchant of Tlatelolco also appointed the leaders of expeditions by vanguard merchants and disguised merchants (Sahagún, 1959, p. 24). The principal merchants themselves were subject to the authority of the city’s ruler. Sahagún (1954, p. 69) notes, “…those who were directors of the marketplace, if they did not show concern over their office, were driven forth and made to abandon their office.”

Members of the pochteca also had specific benefits when traveling abroad. The pochteca are described as having ‘houses’ (calli) in Tochtepec, with merchants of each of the twelve ‘pochteca’ cities ‘residing together’ (Sahagún, 1959, p. 48, 51). Based on the description, these houses appear to have functioned as hostels that traveling pochteca members of all ranks could visit.

Visible signifiers of membership

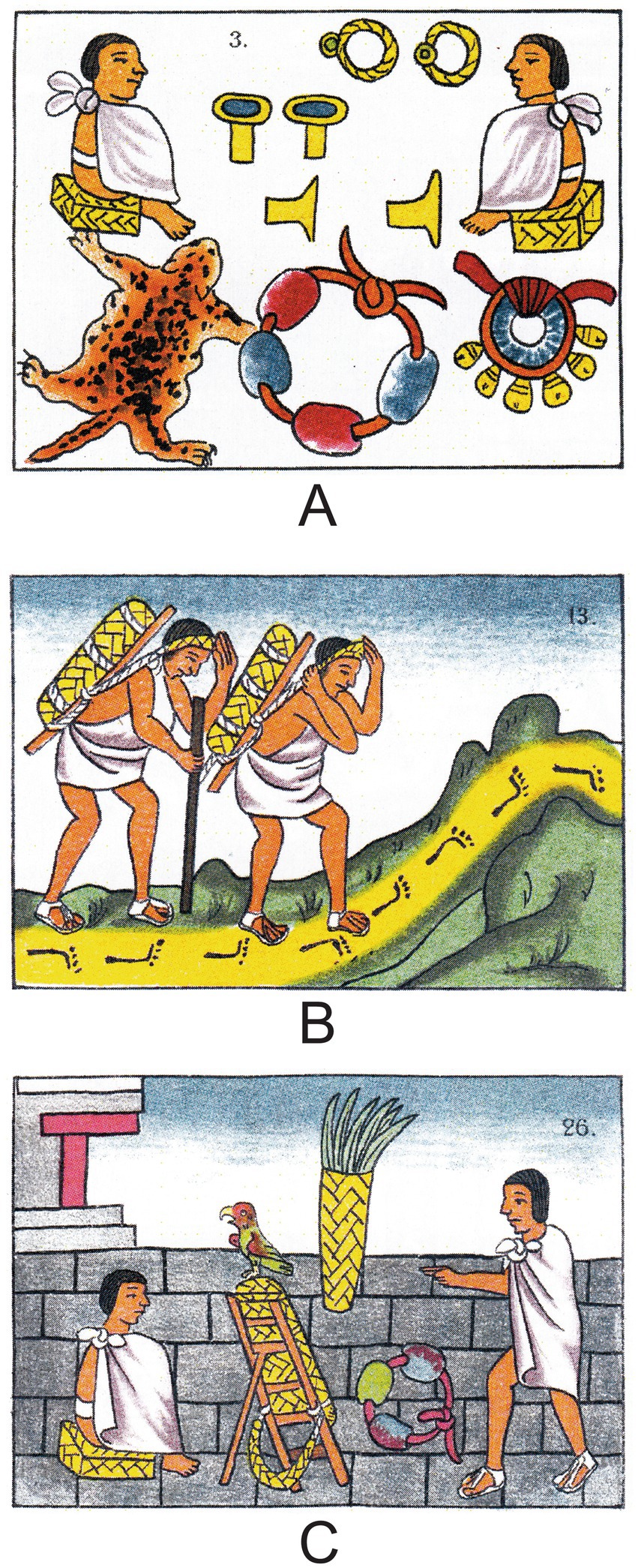

During the reign of the third ruler of Tlatelolco (Quauhtlatoatzin), Sahagún (1959, p. 2) mentions the appearance of “gold lip and ear plugs and rings for the fingers—those called matzatzaztli [or] anillo…” The accompanying Plate 3 includes illustrations of the rings, bearing some sort of device on the front, and makes it clear that they are among the imported goods obtained by the merchants (Figure 3A). Later in the passage (ibid, p. 8), he mentions that matzatzaztli were among the goods that were exclusively traded by the vanguard merchants, together with a range of other luxury and utilitarian items.

Figure 3. Merchants from the Florentine Codex, book 9: (A) plate 3, merchants and their goods; (B) plate 13, merchants on the road; (C) plate 26, merchants’ equipment. Reproduced with permission of University of Utah Press.

Merchants are illustrated in multiple instances throughout the Florentine Codex (Sahagún, 1954, Pl. 96; Sahagún, 1959, Pl. 1–40; Sahagún, 1954, Pl. 74–75, 112–115), as well as the Codex Borgia (Díaz and Rodgers, 1993, Pl. 4). Merchants engaged in travel are consistently depicted with two visible signifiers: staffs, and a backpack with tumpline (Figure 3B). Sahagún (1959, p. 9) specifies that “The vanguard merchants, wherever they went, wherever they penetrated to engage in trade, went carrying their staves.” In many instances, the merchant is shown with a live bird (usually a macaw) perched on his pack (Figures 3C, 4A; Codex Borgia, 1976, Pl. 4, P. 21; Codex Laud, 1966, Pl. 7; Codex Cospi, 1968, Pl. 4; Sahagún, 1959, Pl. 26; Sahagún, 1961, Pl. 114).

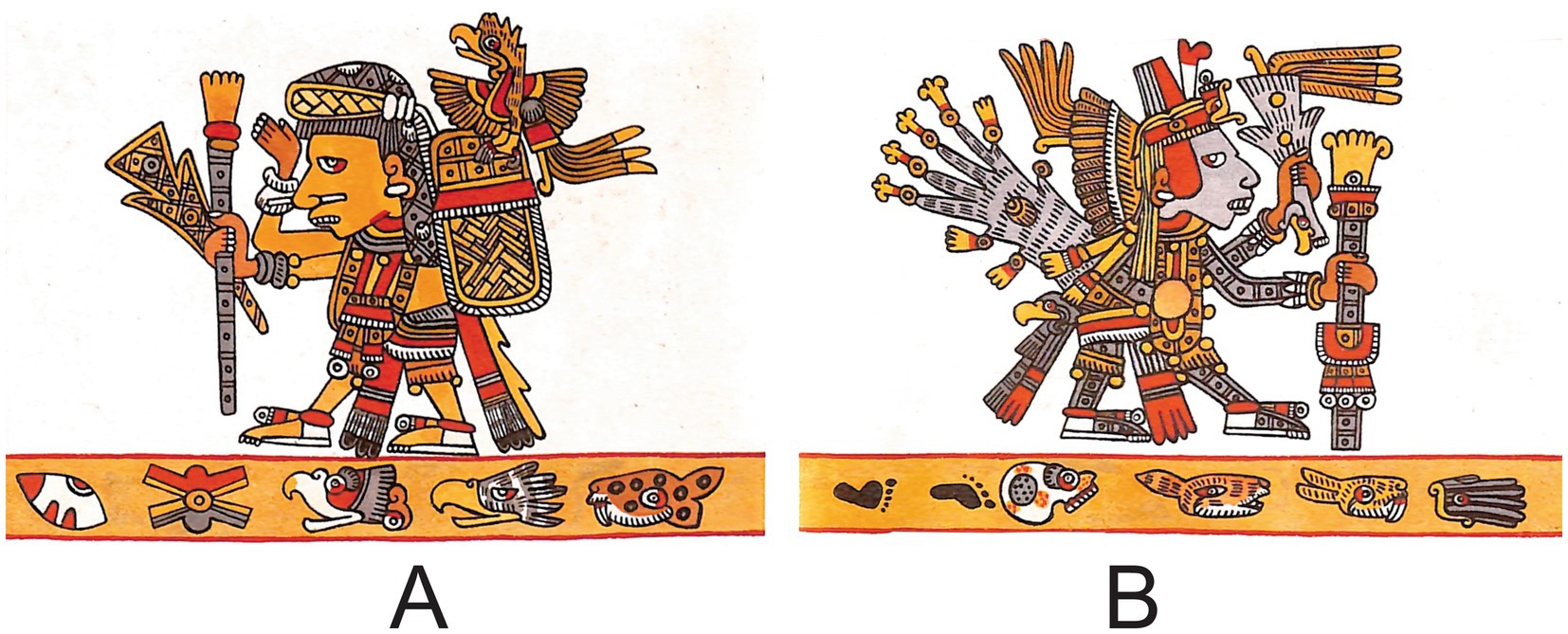

Figure 4. Merchants and merchant deities from Central Mexican codices: Codex Borgia, Pl. 55: (A) Red tezcatlipoca; (B) Yacatecuhtli. Reproduced with permission of Dover Publications.

Supernatural patronage

The principal patron deity of the pochteca was the merchant deity, Yacatecutli (Sahagún, 1959, p. 9, 27). Yacatecuhtli is a Nahuatl name meaning Lord of the Big Nose (from yacatl for ‘nose’ and tecuhtli for ‘lord”) or metaphorically, Lord of the Vanguard (Aguilar-Moreno, 2007, p. 152). In the Codex Fejérváry-Mayer (Pl. 30, 31, 36), Yacatecuhtli appears with a large, Pinocchio-like nose, blue skin, and a short beard, wearing a long necklace and a rectangular headdress with central feather element. In the Codex Laud (Pl. 5), he appears with an aquiline nose, short beard, staff, and backpack. In the Codex Borgia, Yacatecuhtli appears with an aquiline nose and clean-shaven (Figure 4B). He wears one headdress with a central upright element, and a horizontal band with a raptor (probably an eagle) as a central boss; behind his head is a second headdress element with vertical feathers, and dangling to either side of his head are long, gold elements. The deity wears a long ‘bead collar’ decorated with small, gold balls (possibly bells). He holds a staff in one hand, and an atlatl [spearthrower] in the other, suggestive of the militaristic aspects of merchant activity. Yacatecuhtli was honored in the majority of ceremonies organized by the pochteca, which are described in great detail by Sahagún (1959, p. 51), and he was honored at shrines within the merchant ‘houses’.

Other deities can occasionally also be associated with merchant activity. For example, in the Codex Borgia, Tezcatlipoca appears on Plate 4 dressed as a merchant, complete with a staff, merchant’s backpack, and a macaw perched on the top of the pack; on Plate 21, he is identified by his smoking mirror foot; and on Plate 55, he appears twice, as both Black Tezcatlipoca and Red Tezcatlipoca (Figure 4B; Byland in Díaz and Rodgers, 1993). Other deities also appear as a merchant, carrying a staff and fan, with a backpack featuring a bird, including a serpent-footed deity in Codex Fejérváry-Mayer (Pl. 35; possibly corresponding to the Maya deity K’awiil/Tohil) and other young, clean-shaven deities in the Codex Laud (Pl. 7) and the Codex Fejérváry-Mayer (Pl. 30, 36, 40).

Funerary rites for pochteca members were also highly specific. The Codex Magliabechiano (1970) depicts a merchant’s funeral, with text that reads: “This figure is when a merchant died, they burned him and buried him with his goods and jaguar pelts. And everything else that he had was placed around him: the guides and gold and jewels and fine stones that he had, and feathers, as if there in Mictlan, which they call the Place of the Dead, he was able to use them for his office” [translation by the author]. The image itself contains a seated-flexed deceased individual wrapped in a white shroud, wearing a copper bell and feather ornaments, and surrounded by a similar array of goods as depicted in association with pochteca merchants in the Florentine Codex (Sahagún, 1959, Pl. 3). Sahagún (1959, p. 25) also describes the funeral ceremony for a pochteca merchant who died abroad. Fellow merchants prepared and adorned the body, and carried it up to the top of a mountain, and leaned against a post, where “his body was consumed” (presumably cremated). Among the adornments, they “painted black the hollows around his eyes; they painted red about the lips with ochre,” evoking traits of Ek Chuah/Yacatecuhtli. When a merchant died abroad, his afterlife was considered to be the same as that of a fallen warrior, accompanying the sun (Tonatiuh) across the sky (ibid).

In summary, the pochteca of the Aztec imperial era meets the historical definition of a guild as a self-organized, membership-based group, with mechanisms for apprenticeship, supernatural patronage (by Yacatecuhtli), and material signifiers (finger rings, backpacks and staves). While not all merchant or artisan organizations in the ancient world are best labeled as guilds, the pochteca do meet these criteria, and their organization reflects many of the same organizing principles observed for Medieval/Renaissance guilds in Europe. They also provide the most historically-detailed example of a professional merchant guild operating exclusively within the regional context of ancient Mesoamerica. The example of the pochteca can be further used to identify similar characteristics of professional merchant associations among other Mesoamerican cultures, most of which do not have an equivalently-detailed manuscript as the Florentine Codex. For most other areas of Mesoamerica, historical documents are considerably less detailed, and surviving written texts from earlier periods (in hieroglyphic scripts on monuments, murals, codices and portable objects) only rarely contain details of economic organization, particularly the numerous kingdoms and confederacies comprising the Maya cultural area.

Maya professional merchants from the Late Classic period to Spanish contact

Although the origins of formal merchant organizations in Mesoamerica are unknown, merchants and their patron deities are visible in the artistic programs of the Gulf Coast and Maya area from the Late Classic period onward (~600–900 CE) to descriptions of their Spanish Contact period counterparts in the early 16th century (see Blom, 1932; King, 2015; Masson, 2021). Historical records describing professional merchants come from many different Maya polities in the eastern Gulf Coast (Scholes and Roys, 1957), Northern Yucatan (Landa in Tozzer, 1941; Piña Chan, 1978, p. 43; Roys, 1943), highland Chiapas (Torre et al., 2011, p. 187), and highland Guatemala (Feldman, 1978, 1985; Ximénez, 1929–1931). These historical records compliment several decades of archaeological research on the spatial and configurational evidence for Maya markets, increasingly visible to archaeologists though a combination of lidar mapping, geochemical traces, and distributional approaches (Anaya Hernández et al., 2021; Barnard, 2021; Cap, 2015a, 2015b, 2021; Chase and Chase, 2014; Chase et al., 2015; Dahlin et al., 2007, 2010; Eppich and Freidel, 2015; Golitko et al., 2012; Kepecs et al., 1994; King, 2015, 2021; Masson and Freidel, 2012; Masson and Peraza Lope, 2014; Ruhl et al., 2018; Terry et al., 2015).

In northern Yucatan, professional merchants were known as ppolom and traveling merchants were ah ppolom yoc (Roys, 1943). Fray Diego de Landa, writing in 1566, observes:

“The occupation to which they had the greatest inclination was trade, carrying salt and cloth and slaves to the lands of Ulua and Tabasco, exchanging all they had for cacao and stone beads, which were their money … and they had others made of certain red shells for money, and as jewels to adorn their persons; and they carried it in purses of net, which they had; and at their markets they traded in everything which there was in that country. They gave credit, lent and paid courteously and without usury” (Landa in Tozzer, 1941, p. 94-96).

Writings by other Spanish Contact-period observers also suggest that many professional merchants in Northern Yucatan were engaged in long-distance trade with lower Central America, trading cotton mantas and feathers in exchange for cacao (Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, 1944, p. 32; Torquemada, 2014, 3, XLI).

As several scholars have observed (King, 2015; McAnany, 2010, p. 256; Sabloff and Rathje, 1975; Tokovinine and Beliaev, 2013), a substantial shift appears to have occurred during the Late Classic-Early Postclassic period transition, where Maya rulers and royal family members embraced identities as traders, a pattern that was widespread by Spanish contact. Landa (in Tozzer, 1941, p. 39) explains: “The son of Cocom who escaped death through absence [from Mayapan] on account of his trading in the land of Ulua [Honduras].” Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés (1944) also claimed that in Chauaca, merchants were part of the noble class. Merchants were said to have constituted the dominant class of Acalan in the Gulf Coast, and that the wealthiest of them, a lord named Paxbolonacha, was the supreme ruler of the cacicazgo [kingdom] (Scholes and Roys, 1957, p. 4). The historical record also linguistically distinguishes between elite merchants and lower-ranking vendors. In northern Yucatan, several other sellers are described in addition to the pplom merchants; ah k’aay was a peddler who wandered from town to town buying and selling, the ah chokom konol sold small commodities such as pins and needles, and the ah lotay konol was a wholesaler or seller of bulk goods (Speal, 2014); similar distinctions were made in highland Guatemala (Feldman, 1978; King, 2015).

Some Maya cities were particularly well-known for their associations with professional merchants. In northern Yucatan, most marketplaces were located in plazas at provincial capitals and other strategically located towns (Piña Chan, 1978, p. 43). In coastal Tabasco, the polity of Acalan is described as the location of a number of flourishing ports of trade at Spanish contact. The principal cities included Xicalanco, on the edge of Laguna de Terminos, and Potonchan, on the edge of the Usumacinta delta, which played important roles in the circumpeninsular maritime trade between the Gulf Coast and Caribbean, as well as inland trade along the Candelaria River to the city of Itzamkanac (Scholes and Roys, 1957). As detailed by Sahagún (1959); see above), Aztec vanguard merchants established trade relationships with both Xicalanco and Cimatán [Cimatlan] during the Late Postclassic period. Xicalanco, in particular, is described as a center of commerce and merchant activity by several Spanish writers, including Torquemada and Cortés. Torquemada states, “There is at the present time a town named Xicalanco, where there used to be much commerce; for from various parts and distant lands merchants assembled, who went there to trade” (2014, p. 32).

The Late Postclassic period town of Zinacantan, in highland Chiapas, is famously described by Torre et al. (2011, p. 187) as a town of merchants:

“The people of this town are naturally more genteel than the rest of their nation, and all are merchants or most of them, and for this they are known in all these lands and many others … Even though the land is sterile this town abounds in all things because others come here to buy what is necessary and also to sell what they bring. They are also presumptuous and they do not value planting, or do crafts, because they say they are merchants.”

According to Sahagún (1959, p. 21), Zinacantan was sufficiently important that it was visited regularly by disguised pochteca merchants during the reign of Emperor Ahuitzotl, “before the people of [Zinacantan] had been conquered.” According to Herrera, the Mexica were able to establish a garrison at Zinacantan, but this garrison is not mentioned by either the first conquistadors to enter the region such as Díaz del Castillo (1960) and Godoy (1946), or early friars such as Las Casas (1987), although Fray de la Torre and Díaz del Castillo both describe Zinancantan as a town of merchants. Viqueira Albán (1999) and Viqueira, 2006) suggests that the Triple Alliance forged a commercial and military alliance with Zinacantan, allowing its armies and tax payments to travel safely between the Gulf Coast and the province of Xoconochco [Soconusco], avoiding the Chiapanecs in the Central Depression and Zapotecs in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

Maya merchants also had important roles as judges and exchange dealers, similar to the pochteca duties described in Sahagún (1961). According to Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés (1944), in the commercial center of Cachi, “there were their inspectors of weights and measures and judges in a house near one end of the plaza, like a town hall, where all the litigations were settled in a few words … giving to each one what was justly his.” Similarly, for highland Guatemala, Las Casas (1958, p. 353) specifies that marketplaces had a magistrate or “mayor” (juez o alcalde o fiel y secutor), who made sure that no one harmed anyone else, and settled any doubts or disputes over merchandise. Gaspar Antionio Chi (in Tozzer, 1941, p. 231) asserts that merchants operated outside social hospitality norms in northern Yucatan, and were expected to pay for food, drink, and lodging in the towns they visited.

Supernatural patrons of Maya merchants

The Maya merchant deity is commonly known as Ek Chuah (Yucatecan; Landa in Tozzer, 1941, p. 107), Ik Chaua (Chontal; Thompson, 1970, p. 306) or Ik’ Chuaj (K’iche’; Christenson, 2022, p. 39). Ik or Ek means both “black” and “star” in Yucatecan languages (Thompson, 1970). Landa mentions Ek Chuah in two separate contexts, as one of the patron gods of cacao growers, and a guardian over travelers (Tozzer, 1941, p. 164, 107). Ek Chuah likely derives from a deep tradition of merchant activity stretching back into the Classic period, combining a black-skinned merchant deity from Central Veracruz with the Classic period Maya merchant deity, God L (Taube, 1992, p. 799–88; see below). Ek Chuah is commonly featured in Late Postclassic period art; he appears in the Madrid, Dresden and Paris Codices (Figure 5), on the murals of Santa Rita Corozal (Gann, 1902), and on a variety of ceramic art (Taube, 1992; Thompson, 1957). He is typically portrayed with a black or black-and-white striped body with a distinctive red or white area marking the lips and chin, a long “Pinocchio” nose, eyes that are either hollow or marked with horseshoe elements, and a protruding lower lip. He typically carries a staff (but occasionally weapons of war, such as a spear or axe), and a merchant’s pack with tumpline and carrying frame (Figures 5A,B). His headdresses variously include a braided headband (evoking a tumpline) with frontal element (often feathers), decorated with jewels and/or beads (Figures 5A–C,E). Ek Chuah is also portrayed on effigy incense burners at Mayapan, featuring hollow eyes and a long nose, and sometimes also whiskers and/or protruding lower lip (Thompson, 1957; Peraza Lope and Masson, 2014, p. 479).

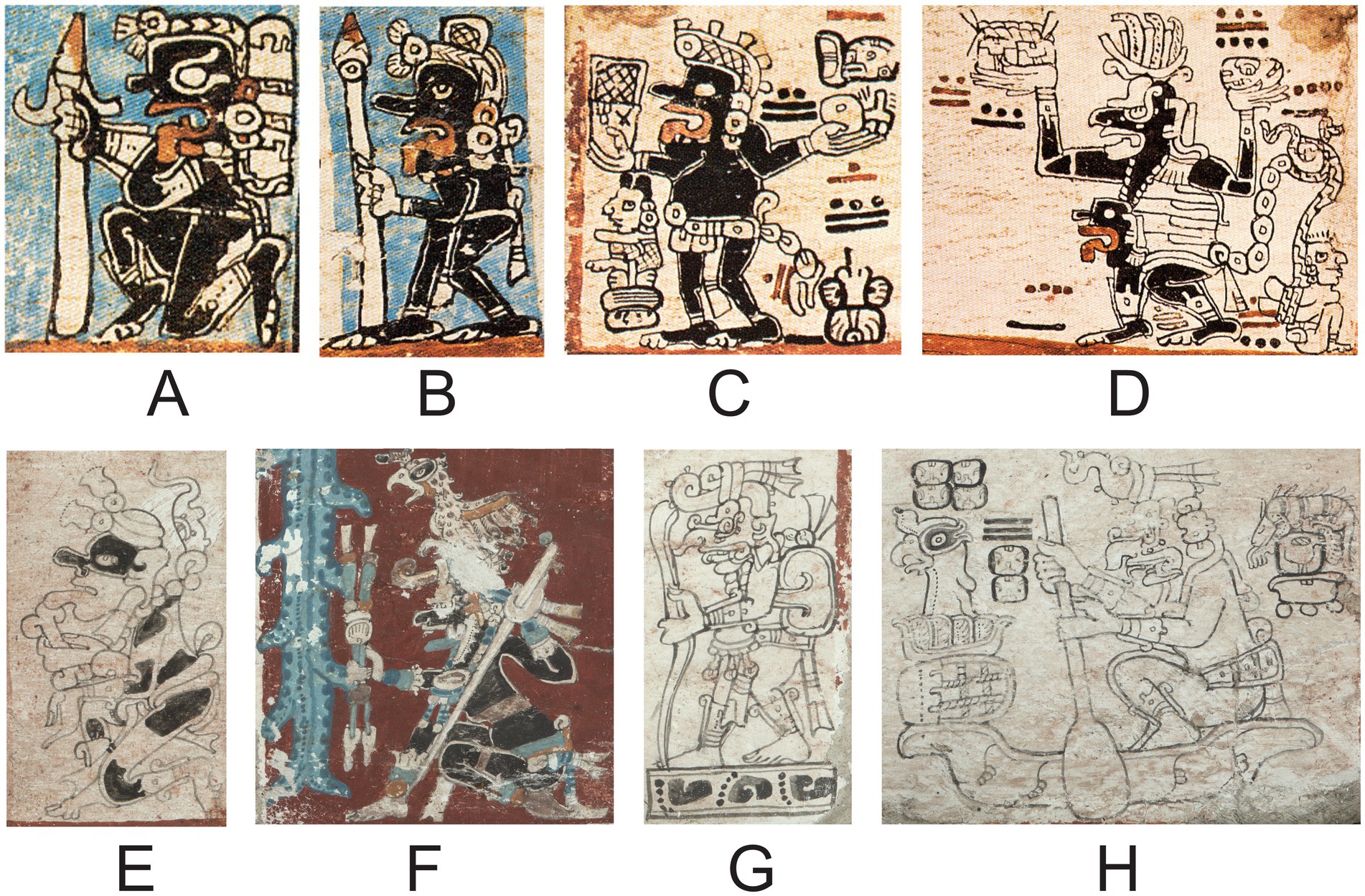

Figure 5. Merchant deities and deities as merchants. Madrid Codex: (A) Ek Chuah with merchant’s backpack and spear (p. 52); (B) Ek Chuah with tall headdress and spear (p. 54); (C) Ek Chuah with beaded headdress and a scorpion’s tail (p. 79); (D) Itzamna with a scorpion’s tail, wearing a trophy head of Ek Chuah (p. 83, Pl. XXXIV). Dresden Codex: (E) Ek Chuah (p. 16); (F) God L carrying a merchant’s staff and darts (p. 78); (G) Chaac walking along a road with a merchant’s staff and backpack (p. 69); (H) Chaac in a canoe with a merchant’s pack and God L headdress (p. 46). Madrid Codex: Museo de América, Public Domain. Dresden Codex: Sächsische Landesbibliothek, Dresden, CC BY-SA 3.0.

In the Maya Codices, the attributes of Ek Chuah are sometimes combined with Chaac, K’awiil, Itzamna and/or Tlaloc (Figures 5D,F–H; see also Taube, 1992). In one scene in the Dresden Codex, Chaac paddles a merchant’s canoe, with a pack and live macaw positioned in the bow (Figure 5H); in another, Chaac walks along a road with a merchant staff and backpack (Figure 5G). A scene of the Madrid Codex depicts Itzamna with black skin and a scorpion tail, wearing a trophy head of Ek Chuah around his neck (Figure 5D). On the Santa Rita murals (Gann, 1902), a deity with a long nose and beard (possibly Yacatecuhtli), faces a second deity holding two severed heads, one of which represents Ek Chuah and features his distinctive hollow eyes, long nose, protruding lower lip, and braided headdress (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Santa Rita Corozal murals, West Wall, Mound 1. Modified from Gann (1902): plate XXXI by the author. Public domain.

Ek Chuah has clear ties to the Classic period Maya merchant deity, God L (Taube, 1992, p. 799–88). In Classic Maya art, God L was portrayed as an underworld lord, an aged deity also often depicted with black skin, and also a patron of long-distance merchants, obsidian trade, and tobacco (Bassie-Sweet, 2021; McAnany, 2010; Taube, 1992). He is sometimes shown carrying a walking staff, with a long string of jade beads around his neck, smoking a cigar, wearing a large, broad-brimmed hat decorated with an owl’s head. God L is widely depicted on polychrome vases and mural art in the northern Yucatan and lowland sites, particularly Palenque; however, he also appears in the Classic period art of southern Veracruz, including ceramic art from Rio Blanco and Cerro de las Mesas Monument 2 (Taube, 1992, p. 85). A version of God L appears on the Cacaxtla Murals (dated the 8th-9th centuries CE; Brittenham, 2009, p. 138), with blue skin and a yellow area marking the lips and chin, wearing a jade pectoral, a decorated white cape around his shoulders, and a jaguar pelt comprising the lower half of his body. He stands in front of a stylized cacao tree; behind him is a merchant’s pack loaded with luxury goods such as tropical feathers, and a broad-brimmed hat depicting an owl’s head strapped to the back of the pack (Taube, 1992). A Late Postclassic period version of God L in the Dresden Codex appears with black skin, wearing an owl headdress, and carrying a merchant’s staff and darts (Figure 5F; see Taube, 1992).

Ek Chuah’s various traits seem to combine selected elements of both God L and Yacatecuhtli (Taube, 1992, p. 90); the high mobility of professional merchants likely resulted in ideas regarding merchant deities becoming widely shared across political and cultural boundaries. A ceramic sculpture from the site of El Zapotal (dated to 600–900 CE) portrays a merchant deity with black skin and red lips, but the proportions of the nose and lips are unexaggerated (https://lugares.inah.gob.mx; see Supplementary Table S2). A venerera deposited in a merchant’s burial at the site of Caucel (northwest Yucatan) dates to the Late Classic period (580–660 CE) and depicts a deity with both Ek Chuah and God L traits: black skin, the elongated lower lip highlighted in red associated with Ek Chuah, and the old age and smoking a cigar associated with God L; the deity also carries a staff in one hand and an unknown item (conch shell trumpet or atlatl) in the other, and is accompanied by a small dog (Rodríguez Pérez et al., 2024, p. 158). An Early Postclassic period incense burner from a merchant’s burial at Nebaj features a deity with the characteristic Pinocchio nose and an elongated lip of Ek Chuah (Smith and Kidder, 1951, p. 5). The vessel was recovered from a tomb with other trade goods including Tohil Plumbate pottery, an alabaster bowl, a piece of jade mosaic, and gold and copper ornaments; the Tohil Plumbate suggests a date of 900–1000 CE (see Neff, 2023). Additionally, Brasseur de Bourbourg collected a copper mask, possibly in Alta Verapaz (its exact provenience is unclear), representing a human head with a Pinocchio nose and an exaggerated lower lip (Thompson, 1965, p. 167; see also Bray, 1977, Figure 12).

A few Maya artworks from the Late Classic and Terminal Classic periods also depict human merchants with many of the attributes that later appear in Postclassic artwork. The Calakmul murals, dated to 620–700 CE, portray a range of vendors in a market setting, labeled by their wares as ‘salt-person,’ ‘maize gruel-person’, ‘tobacco person,’ etc. (Carrasco Vargas et al., 2009; Martin, 2012). One portion of the mural depicts a ‘bearer’ with many of the visual signifiers of merchants in later periods: holding a staff, and carrying a large olla (jar) on his back with a braided tumpline, and a large-brimmed hat perched on top of the olla featuring a large raptorial bird head (ibid.). Murals at Chichen Itza’s Temple of the Warriors (800–1050 CE) portrays merchant figures traveling along a coastal road; they carry packs with tumplines, and hold walking sticks (Kristan-Graham, 2001, p. 356).

Anthropomorphic face rings and their distribution

Beginning in the Early Postclassic period, metal objects are increasingly found at Maya sites in eastern Chiapas and western highland Guatemala. Over 100 metal items have been recovered from sites in this region, as well as neighboring areas such as the Pacific Coast (Álvarez Asomoza, 2012; Ball, 1980; Barrientos, 1987; Becquelin, 1969; Blake, 2010; Butler, 1940; Carmack, 1981; Domenici and Lee, 2012; Durand-Forest, 1976; Dutton and Hobbs, 1943; Guillemin, 1977; Lee and Bryant, 1996; Lee, 1969; Marqusee, 1980; Mencos and Moraga, 2013; Navarrete, 1966; Palka, 2023; Paris and López Bravo, 2012; Peñuelas Guerrero et al., 2012; Smith and Kidder, 1943; Strebel, 1885; Tenorio Castillejos et al., 2012; Torres et al., 1996; Voorhies and Gasco, 2004; Woodbury, 1964; Woodbury and Trik, 1953; see Supplementary Table S1). While a few metal objects have been recovered from Classic-period contexts in the Maya area (Lothrop, 1952; Pendergast, 1970), they are regularly found with Tohil Plumbate and Silho Fine Orange pottery, dating them to the period from approximately 900–1000 CE (Neff, 2023). The range of metal items recovered includes both historically-documented currency items (copper bells, small copper axes, and copper axe-monies), personal ornaments (effigy pendants, sheet metal ornaments), and tools (needles, chisels, fishhooks). As I have suggested previously (Paris and Peraza Lope, 2013, p. 164), from their earliest appearance in Maya sites, metal items became an addition to, rather than a replacement of, jade and shell commodities that played prominent roles in Late Preclassic and Classic Period exchange systems (Freidel et al., 2002).

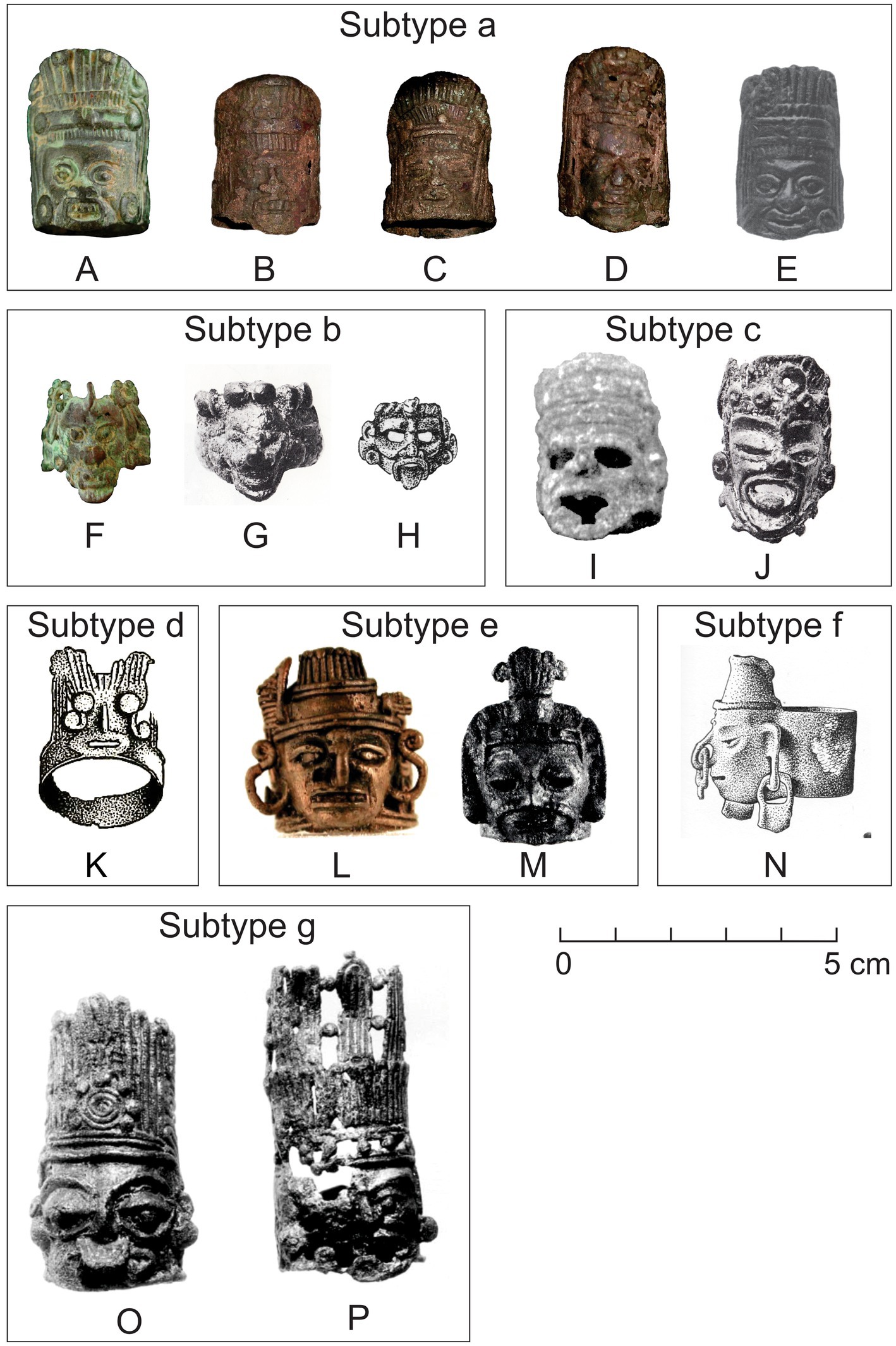

Copper anthropomorphic face rings (Bray, 1977), or as Pendergast (1962) describes them, “Band with modeled head decoration—Anthropomorphic” (Type IVC1) are a very visually-distinctive subset of copper rings. They exist in tandem with a range of other styles, including plain flat bands, plano-convex bands (single or double-wide), decorated with cables, or wirework in a variety of designs (Pendergast, 1962). Extending Pendergast’s typology, I define seven subtypes on the basis of shared stylistic conventions, such that the rings may have been fabricated by a single metalworking ‘community of practice’ (sensu Wenger, 1998). I use lower-case letters for subtypes, in order to maximize compatibility with Pendergast’s system (e.g., Type IVC1a for Subtype ‘a’).

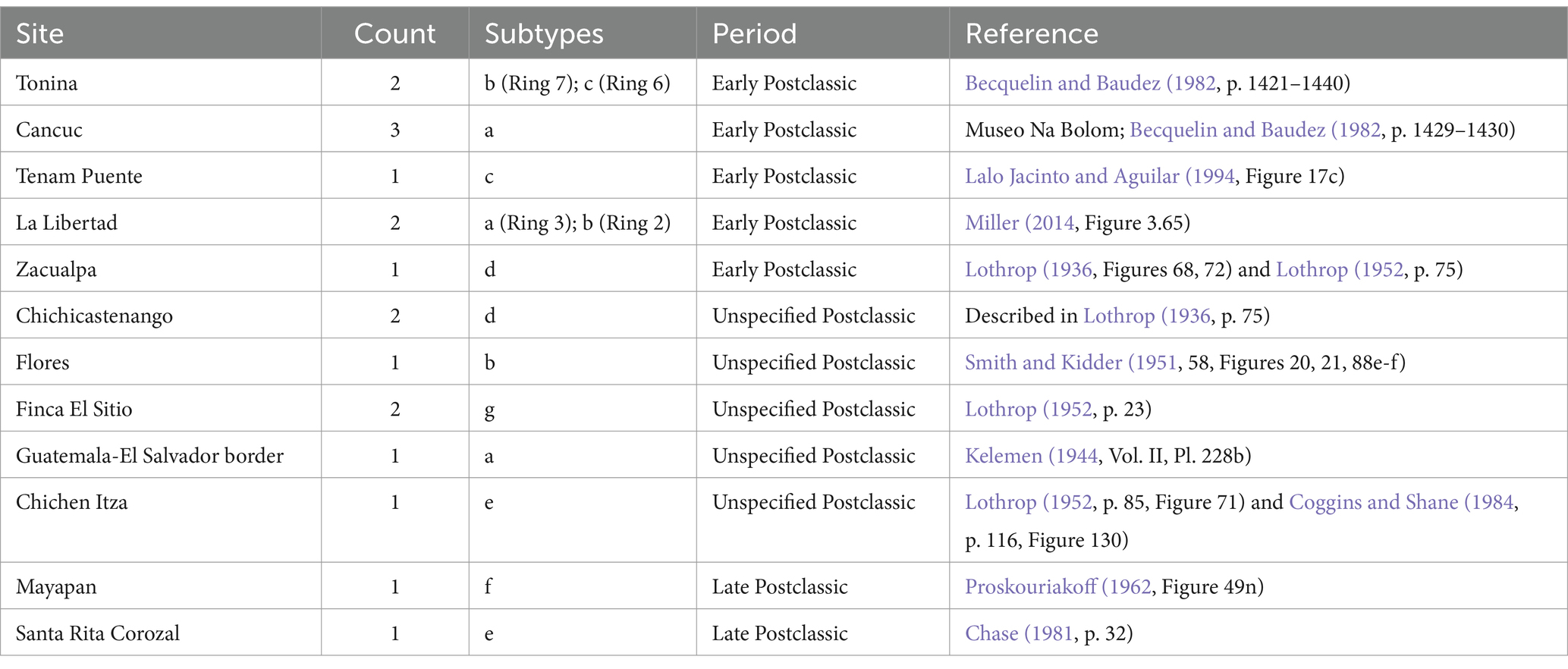

In total, there are eighteen documented anthropomorphic face rings in the Maya area, spanning both the Early Postclassic and Late Postclassic periods (Table 1). At least fourteen other examples are attributed to the Huastecs of the Gulf Coast, the Purépecha (Tarascan) Empire of West Mexico, the Mixtec cultures of northern Oaxaca, and the Mexica of Central Mexico; they are published in online museum catalogues, and mostly date to the Late Postclassic period (Supplementary Table S2).

The anthropomorphic face rings from eastern Chiapas represent known characteristics of Ek Chuah/Yacatecuhtli as detailed above (see Table 1; Figure 7). Most rings clearly depict round (sometimes hollow) eyes and a bulbous nose, features associated with both deities. Among the subset of rings from Early Postclassic contexts in eastern Chiapas/western Guatemala, Subtype ‘a’ includes low-relief rings that have the short beard, grimacing expression, and erect-feather headdress with long elements framing the face, often associated with Yacatecuhtli. Subtype ‘b’ has high-relief rings more indicative of Ek Chuah, frequently depicted with a braided or twisted cord headdress and a protruding lower lip. Subtype ‘c’ also includes high-relief rings with hollow eyes and/or mouth, combined with an erect-feather headdress. Subtype d has a simple headdress with divided, long elements (possibly feathers, but in the Codex Borgia they are depicted in gold), a hollow mouth, and large, round eyes. Two examples from Finca El Sitio (Subtype ‘g’) have high-relief faces with highly detailed, tall, erect-feather headdresses in wirework, with nose ornaments, grimacing expression, and heavily rimmed eyes similar to the depiction of Tlaloc on Tohil Plumbate pottery (Shepard, 1948); these stylistic similarities suggest an Early Postclassic period date. Beyond these two traits, most rings also portray a number of other elements that are generically associated with elite/deity status, including large earspools and round jewels adorning the headdress.

Figure 7. Anthropomorphic face rings from southeast Mesoamerica. Subtype a: (A) La Libertad Ring 3; (B) Cancuc Ring 1; (C) Cancuc Ring 2; (D) Cancuc Ring 3; (E) Guatemala-El Salvador Border. Subtype b: (F) La Libertad Ring 2; (G) Tonina Ring 7; (H) Flores. Subtype c: (I) Tenam Puente; (J) Tonina Ring 6. Subtype d: (K) Zacualpa. Subtype e: (L) Chichen Itza; (M) Santa Rita Corozal. Subtype f: (N) Mayapan. Subtype g: (O,P) Finca El Sitio. Reproduced with courteous permission of the authors/publishers: A,F. New World Archaeological Foundation; B-D. Photos by the author, courtesy of the Museo Na Bolom; E. Dover Publications; G,J. Centre d’Études Mexicaines et Centraméricaines; I. Gabriel Lalo Jacinto; H,K,N. Carnegie Science; L,O,P. The Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University; M. Diane Chase and the Corozal Postclassic Project.

The subtypes that appear in the Maya area during the Late Postclassic period are stylistically distinct from the earlier subtypes, but also have many characteristics of Ek Chuah/Yacatecuhtli (Figure 7). Subtype ‘e’ from Santa Rita Corozal has a high-relief face, hollow eyes, and whiskers; the erect feather element on the headdress is also featured on Yacatecuhtli’s headdress in the Codex Fejérváry-Mayer (1971). Subtype ‘f’ is found only at Mayapan, with the face cast in high-relief presentation, a horizontal, square headdress, and hollow eyes, nose, ears, and mouth; the nose has a dangling (mobile, T-shaped) ornament, and the perforated earlobes also have dangling ear ornaments (Proskouriakoff, 1962).

Many rings also portray elements that are less common in portrayals of Ek Chuah and Yacatecuhtli, but are still consistent with their known attributes. La Libertad Ring 3 has Tlaloc goggles encircling the eyes (Miller, 2014), and the heavily-rimmed eyes of the Finca El Sitio rings also evoke Tlaloc. La Libertad Ring 2 has a headdress with a five-petaled flower (Figure 7F), which could be, among other possibilities, cacao blossoms, since Ek Chuah is traditionally associated with the cacao trade. The mouth of the Tenam Puente ring forms the ‘Ik’ symbol, or ‘wind’ glyph (Figure 7I). Many rings, particularly Subtypes a and d, have long dangling elements framing the face (Figures 7A–E,L). While they could be quetzal feathers, the depiction of Yacatecuhtli in the Codex Borgia (Figure 4B) depicts these elements in gold. The ‘bead collar’ depicted on Tonina Ring 6 (Figure 7J) also appears on Yacatecuhtli in the Codex Borgia (Figure 4B) and on the Santa Rita Corozal murals (Figure 6).

Discussion

The proliferation of anthropomorphic face rings throughout southeast Mesoamerica is a spatially and temporally patterned phenomena, which, I argue, is related to their use as signifiers for early professional merchants. Finger rings are historically popular as merchant guild signifiers; they are light-weight, portable, and can be crafted with visually distinctive symbols such as supernatural patrons. The use of rings as signifiers of merchant guild membership was quite common in Late Medieval Europe (De Francesco, 1938; see above). A particularly early subset of rings date to the Early Postclassic period, and are associated with sites in eastern Chiapas and highland Guatemala. The Early Postclassic rings depict known traits of Ek Chuah/Yacatecuhtli in a highly patterned way, with distinguishable subtypes, which are most commonly deposited as offerings in elite burials. I argue that, following Bray’s (1977) suggestion, these rings functioned as signifiers for elite Maya professional merchants. They represent the antecedents of the matzatzaztli described in the Florentine Codex, which, if Sahagún’s (1959) informants are correct, were obtained from elite merchants at Gulf Coast cities such as Xicalanco and Potonchan by the mid-fourteenth century.

The earliest known copper face rings date to 900–1000 CE, suggesting their emergenceas merchant guild signifiers at that time

The earliest copper face rings from excavated contexts are all from Early Postclassic period sites in highland Chiapas: Tonina, Tenam Puente, and La Libertad. They are consistently found in contexts associated with Silho Fine Orange and Tohil Plumbate pottery, two fine-paste pottery types that were widely exchanged from approximately 900–1000 CE (Neff, 2023). At Tonina, the two rings were recovered from Tomb IV-7, an Early Postclassic period cremation burial of an adult woman in the site’s Acropolis, that also contained a Silho Fine vessel, a jade and spondylus bead necklace, five gold foil ornaments, and seven other copper rings (Becquelin and Baudez, 1982, p. 148). The La Libertad rings were also recovered from a funerary context of an adult male, found around the fingers, together with four other rings, also dated to the Early Postclassic period (Miller, 2014). The Tenam Puente ring was found as part of an offering in the site’s Acropolis, together with ceramic vessels attributed to the Early Postclassic period (Lalo Jacinto and Aguilar 1994, p. 31, Figure 17c). The Nebaj vessel depicting Ek Chuah was also recovered from an Early Postclassic tomb containing a Tohil Plumbate vessel and other metal objects (Smith and Kidder, 1951, p. 26). Collectively, the evidence suggests a popularization of Ek Chuah/Yacatecuhtli as a merchant deity in eastern Chiapas and highland Guatemala in tandem with long-distance exchange of Silho Fine Orange and Tohil Plumbate pottery.

In previous publications, I have outlined evidence for an intensification of exchange relationships between highland Chiapas and the Gulf Coast during the Early Postclassic period, including the importation and emulation of pottery, figurines, and portable sculpture (Paris and López Bravo, 2020; Paris et al., 2021, 2023). Since the earliest examples of Ek Chuah/Yacatecuhtli appear in Veracruz and northwest coastal Yucatan (Rodríguez Pérez et al., 2024), increased professional connections between highland Maya merchants and their Gulf Coast counterparts represents a possible avenue for the popularization of this deity. While there is a concentration of anthropomorphic face rings in eastern Chiapas, the discovery of a Subtype ‘a’ ring along the Guatemala/El Salvador border (Kelemen, 1944, Vol. II, Pl. 228b) and a Subtype ‘b’ ring at Flores Island (Smith and Kidder, 1951, p. 58, Figures 20, 21, 88e-f) suggest that the rings, along with worship of this deity, likely traveled along with professional merchants themselves: through eastern Chiapas between the Gulf Coast and Pacific Coast (Navarrete, 1978), along overland routes to the Peten (Adams, 1978), and along the Pacific Coast as far as El Salvador (Navarrete, 1978). Use of the rings continued into the Late Postclassic period as well, with the proliferation of new styles throughout the northern Yucatan, the Mixteca, and the Purépecha Empire, and eventually, by pochteca merchants from Tlatelolco.

Copper face rings were the products of several different metalworking communities, depicting a constellation of Ek Chuah/Yacatecutli traits

Metalworkers responsible for crafting Ek Chuah/Yacatecutli rings clearly had a working knowledge of the iconic features of those deities; however, the proliferation of distinct subtypes suggests that they were not single-origin, but were commissioned by different groups of metalworkers. Since multiple subtypes were found in the same burial (Subtypes ‘b’ and ‘c’ at Tonina, and Subtypes ‘a’ and ‘b’ at La Libertad), we can infer that they were used contemporaneously, and that the use of a particular subtype was not mutually exclusive with use of other subtypes. Similarly, subtypes were not hyper-local; examples of Subtype ‘a’ rings are found from Tonina south to the Guatemala-El Salvador border (approximately 575 km), while Subtype ‘b’ rings are found from La Libertad to Flores (approximately 420 km). Since a single individual could own rings of multiple subtypes, perhaps the different ring styles reflect affiliations with particular merchant organizations or trade routes.

Two anthropomorphic face rings also present Tlaloc goggles (Figures 7A,E), while the two examples from Finca El Sitio have heavily rimmed eyes similar to the depiction of Tlaloc on Tohil Plumbate pottery (Shepard, 1948). On Tohil Plumbate vessels, Tlaloc is frequently portrayed with short beard (Shepard, 1948), similarly to the way Yacatecuhtli’s beard is portrayed in Central Mexican codices. Conversely, the Tlaloc goggles on the ring from La Libertad (Figure 7A) are more similar to depictions of Tlaloc paraphernalia worn by Late Classic rulers on monuments from eastern Chiapas (Bassie-Sweet, 2021; Earley, 2023). While Tlaloc goggles are also portrayed on rings from the Purépecha Empire (02.5–06233) and the Mixteca area (07.0–05048), they are more stylistically similar to the large, round goggles depicted in Teotihuacan art (Bassie-Sweet, 2021; see Supplementary Table S2).

Notably, none of the rings explicitly portrays the Late Classic period God L (see Bassie-Sweet, 2021; Brittenham, 2009). This suggests that the increased popularity of Ek Chuah/Yacatecuhtli in eastern Chiapas during the Postclassic period developed in tandem with the proliferation of copper rings as merchant guild signifiers within a pre-existing landscape of merchant activity.

Anthropomorphic face rings were produced by skilled metalworkers, rather than casually-made products

The fabrication of anthropomorphic face rings required knowledge of foundry materials, wirework sculpting, high-temperature ceramics for mold-making, and pyrotechnical knowledge, along with technical and artistic skill to create the iconic features of Ek Chuah/Yacatecuhtli (see Hosler, 1994). This assumes the rings were crafted through remelting alone; mining and smelting would have required additional labor and expertise. Thus, these rings were specialized items, likely commissioned by elite merchants explicitly for use as signifiers or membership. Their restricted distribution suggests that these rings were not available to the general public for commercial purchase, unlike other metal items such as copper bells, needles, fishhooks, and miniature axes, which were much more widely available (see Supplementary Table S1). The vast majority of the Mesoamerican population would have lacked the raw materials, technical skill, and artistic knowledge required to make them, which would have enhanced their exclusivity by making them extremely hard to replicate by non-members.

Rings were fabricated through lost-wax casting, from sculpted stingless beeswax models (see Paris et al., 2018). Subtypes ‘b’, ‘c’, ‘e’, ‘f’ and ‘g’ reflect three-dimensional sculpting, modelling and wireworking. Subtypes ‘a’ and ‘d’ could hypothetically have been cast in a flat mold using an impressed wirework model, with the band subsequently hammered to shape; this is suggested by one of the rings from Cancuc, which appears to have a join at the reverse of the band. However, as no two rings have yet been found alike even within Subtype ‘a’, even flat castings were not simply carbon copies of a single face; or at least, a variety of faces existed.

Anthropomorphic face rings were frequently interred in elite Maya burials in the monumental zones of regionally-important cities; that elites were professional merchants; and that merchants could be both male and female

The anthropomorphic face rings from Tonina and La Libertad are specifically from funerary contexts in which an elite individual was buried with multiple copper rings, and the Tenam Punte ring was recovered from an elite offering in the site’s Acropolis. These three political centers remained occupied through the Late Classic-Early Postclassic transition. The Zacualpa ring was recovered from an elite burial with a tumbaga disk and two zoomorphic metal ornaments, also dated to the Early Postclassic (Lothrop, 1952, p. 75). In the Late Postclassic period, the Santa Rita Corozal ring was also interred in the burial of an elite woman (Chase, 1981).