- Department of Psychology, Educational Science and Human Movement, University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy

Migrant women’s wellbeing and access to health are particularly impacted by gender inequality and discrimination, traditional female roles, gendered labour market, gender-based violence and feminization of poverty. From an intersectional lens, undocumented migrant women are at the lowest tier in the hierarchy of healthcare access. This research explores the nexus of irregular migration and health spheres in a gender perspective, focusing in particular on the undocumented migrant women’s acts of citizenship. Based on the theoretical framework of fundamental causes, this research analyses the perception of street level bureaucrats, through the conduction of fifteen semi-structured interviews, in 2024–2025, on the endowment to health assets of undocumented migrant women in Sicily, by answering the following research questions: (1) how the undocumented status of migrant women affects their endowment in accessing healthcare?; (2) in what way does the socioeconomic status influence the access of undocumented migrant women to health? and (3) how can undocumented migrant women’s social capital enhance their endowment to health? The research confirms the existence of fundamental causes hindering undocumented migrant women’s access to healthcare, especially regarding the low socioeconomic status and cultural capital of the receiving country. The cause, as low economic status, influences multiple disease outcomes and enhances differential vulnerabilities of undocumented migrant women. In particular, practitioners reported the incidence of precarious housing and working conditions in women’s health.

1 Introduction

In the last decades, a strong presence of migrant women has changed the international migration panorama (Morokvaśic, 1984; Gabaccia, 2016; Pande, 2022). Worldwide, in 2019, out of the 169 million migrant workers, 99 million were males (58.5%) and 70 million were females (41.5%) (Abel, 2022). Two main factors have widely contributed to the enhancement of the feminisation of migration (Zanfrini, 2016) and; the international gendered division of reproductive labour (care work, domestic work, service work), which reinforced the stable settlement and social rooting of immigrant populations in the receiving countries and, the intensification of family reunifications and the shortened duration of the family reunification process (Bartholini, 2021). Despite women’s migration projects being usually guided by their desire to improve their socio-economic conditions, women’s wellbeing in the receiving countries is often challenged due to their positionality as migrant women, particularly access to health services, work and housing conditions (WHO, 2017).

At a macro level, migration is structurally and hierarchically formed by legal and social categories that delimit individuals’ access to fundamental rights, including the entitlement to health services and second-level care (Bilecen, 2019). According to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), migrant women’s wellbeing and access to health are particularly impacted by gender inequality and discrimination, traditional female roles, gendered labour market, gender-based violence and feminization of poverty.1 The nexus of gender and migration status collocates undocumented migrant women2 in the Social Gradient of the reception country (Wilkinson and Marmot, 1998). Undocumented migrant women are allocated in one of the lowest tiers of civic stratification3 (Torres and Young, 2016), which structurally determines their access to social, economic and cultural assets, exposing them, consequently, to multiple health inequities (Dahlgren and Whitehead, 1991; Lombardi, 2005).

Undocumented migrant women represent a specific category highly marginalised at the policy level (Pellicani and Ince-Beqo, 2024), primarily due to their irregular administrative status (Funge et al., 2020). Other factors also determine the migrant women’s entitlement to health access, such as the lack of adequate resources of reproductive health services, poor health perception (Nielsen and Krasnik, 2010), language, cultural and administrative barriers, economic status, discrimination (Pérez-Sánchez et al., 2024) and psychological and emotional distress (Barkensjö et al., 2018; Funge et al., 2020). All these factors endorse the resistance of migrant women in using specialised care (Carmona et al., 2014; Llop-Gironés et al., 2014; Saunders et al., 2021), resulting in an underutilisation of health services when compared with the autochthonous population (Pérez-Sánchez et al., 2024). Despite the plethora of obstacles in accessing health services, literature has confirmed undocumented migrant women’s Acts of citizenship4 (Isin and Nielsen, 2008), to enhance their health endowment (Bartholini, 2019). They often rely on their social capital based on their community or family members (Pérez-Sánchez et al., 2024) and third civil society stakeholders facilitating women’s healthcare access (Genova and Terraneo, 2020).

The first part of the article dissects the conceptualisation of the undocumented migrant women’s health entitlement, scrutinising the theory of Fundamental causes (Link and Phelan, 1995) and the Italian and Sicilian legal framework on the health of undocumented migrants. The second part proceeds with the empirical analysis of the undocumented migrant women’s health endowment in Sicily. Finally, this research analyses the capabilities of migrant women, as social agents with a limited Italian cultural and socio-economic capital5, negotiating in “spaces of illegality” and in a constrained setting of social policies (Ruhs and Anderson, 2007). This research, based on the theoretical framework of “fundamental causes” (Link and Phelan, 1995), explores the nexus between irregular migration and health spheres from a gender perspective, focusing on the undocumented migrant women’s acts of citizenship (Isin and Nielsen, 2008). In particular, it analyses the perception of street level bureaucrats6 regarding the endowment to health assets of undocumented migrant women in Sicily, and aims at answering the following research questions: (1) how the undocumented status of migrant women affects their endowment in accessing healthcare?; (2) in what way does the socioeconomic status influence the access of undocumented migrant women to health? and (3) how can undocumented migrant women’s social capital enhance their endowment to health?

2 Methodology

This article is part of a wider research project7 that aims to analyse the impact of social determinants of health in migrant workers who are at risk or have been victims of labour exploitation in the Veneto and Sicily regions. Relevant elements about the perception of street-level bureaucrats regarding the health endowment of undocumented migrant women have emerged during the semi-structured interviews in Sicily. Consequently, the author proceeded with an accurate desk review of the Italian and Sicilian legal frameworks on the right to health of undocumented migrants. Literature review focused on the “theory of fundamental causes” and the theme of acts of citizenship, in particular, the endowment and entitlement of undocumented migrant women regarding health.

Eight other interviews were added to the initial seven to deepen these subjects from an empirical perspective. Even if the author has extensive experience on the issue of migration in the Sicilian context, due to the complex nature and specificities of this theme, it was necessary to use snowball sampling to access relevant gatekeepers working with undocumented migrants. Fifteen interviews were conducted with relevant gatekeepers working with undocumented migrants in Sicily. In particular, three interviewees were project coordinators; two were health professionals; six were cultural mediators, one was an anti-human trafficking practitioner, two were sociolegal practitioners, and one was a public administrator. The key informants’ pluriannual experience on migration confirmed a consolidated capital on the issue of migration and gender in Sicily.

On average, the duration of the interviews was around 1 hour. All interviews were conducted in Italian, and out of fifteen interviews, eight were conducted online, since the interviewees were based in other provinces of the Sicilian Region and claimed to have time limitations to dedicate to the interview. Most interviewees are from Palermo, while four are based in Trapani, one in Ragusa, one in Siracusa, and three are responsible for all the regional territory. From an initial NVivo analysis, the fifteen interviews resulted in four macro nodes: (1) undocumented status; (2) low economic status; (3) health; and (4) cultural capital of the reception country. The macro node “low economic status” was divided into two micro nodes: “housing” and “labour”; while the macro node “health” was subdivided into the micro nodes: “COVID-19” and “reproductive health.” In a second phase, the analysis resulted in the “relations” of “social capital” with citations extracted from the nodes “cultural capital,” “undocumented status” and “health.”

3 Theoretical framework on the nexus between health and migration

Migration is a complex social construct (Ambrosini, 2020) that influences and determines all social aspects and the livelihoods of the individuals (Sannella and Lombardi, 2020). Migration structurally determines all spheres of the social life of immigrant women through the reproduction of gender norms, values and roles. The interaction between ascribed roles, such as gender and race, and social factors, such as class, female condition and irregular administrative status, collocates undocumented migrant women in one of the lowest tiers of civic stratification (Torres and Young, 2016). This positionality determines their power negotiation and access to assets. According to UNWOMEN (2022), undocumented migrant women are often exposed to inequalities, leading to hazardous working conditions, indecent work, various forms of labour exploitation, poor health, poor access to health and social services, isolation and gender-based violence.

Health is framed as a social phenomenon structurally influenced by an individual’s sociocultural context; that is, the individual’s positionality within the civic stratification can determine the individual’s social and cultural capital (Diderichsen, 2004). Individual’s health is, thus, highly influenced by distant structural determinants at a macro level, such as governance, Macroeconomic Policies, Social Policies ̶ labour and Housing policies ̶, Public Policies, regarding the education and health system and social protection, and Cultural and societal values; and at a meso level such as the individual’s Socio-economic Position, Social Class, Gender, Ethnicity, Education level, Occupation and Income. The individual’s health is also determined by proxemic determinants such as Material Circumstances, Living and Working Conditions, Food Availability, Behaviours and Biological Factors, and Psychosocial Factors (Solar and Irwin, 2010).

Based on Solar and Irwin’s (2010) Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health, we can verify a complex relation between health and migration (Bolaffi et al., 2003). The lack of an administrative status often hinders the migrant’s entitlement to accessing public health services. For instance, according to Smith et al. (2016), only 10 out of 27 EU countries provide legal access to primary health care to undocumented migrants, and Italy is one of them. The health inequity in many welfare states has led to the highlighting of several academics to decouple healthcare systems from immigration procedures, to ensure healthcare to undocumented migrants without fear of repercussions (Funge et al., 2020).

3.1 Legal framework on access to healthcare for undocumented migrants in Italy

The Italian Healthcare system is based on universalistic and solidaristic principles that guarantee the right to healthcare to every individual, even if managed at the regional level, determining significant disparities at the national level in the quality of the offered services. Art. 34 of Testo Unico dell’Immigrazione guarantees equal treatment and the right to access healthcare to third-country nationals as Italian citizens. Furthermore, the Italian legislation foresees the issue of a residence permit for medical reasons.8 However, access to public health services does not encompass all migrant categories9 (Bartholini, 2021). The registration in the Healthcare Regional System is not permitted to non-resident adult EU citizens and undocumented migrants, except migrants married to Italian citizens or considered vulnerable categories, such as third-country women who are pregnant or minors, migrants in the process of regularisation and detainees10 (NAGA-SIMM, 2024). Other non-resident migrant categories cannot access the Regional Healthcare System’s primary and secondary level care. Undocumented migrants who do not fall in these categories can directly access first-level care and specialist care, and the “outpatient clinics” for second-level care, upon the attribution of the STP-Straniero Temporaneamente Presente, hereinafter STP. The Italian legislation guarantees11 to undocumented migrants “the access to public and accredited facilities, urgent or essential outpatient and hospital care, even if continuous, for illness and injury, and preventive medicine programmes are extended to safeguard individual and collective health.”

The registration to the Regional Healthcare System, for Italians and foreigners, except third-country nationals who are assigned the X01 code12, is based on the cost-sharing fee established by the Regional Healthcare System. Although the ASL-Aziende Sanitarie Locali emits the STP, it is valid for 6 months in the entire national territory and renewable for another 6 months (Sannella and Lombardi, 2020). EU non-resident citizens who declare an indigent state can access the Regional Healthcare system by paying 242 euros or the annual emission of ENI- Europeo Non Iscritto, renewed every 6 months, that guarantees access to healthcare, as provided by the Art. 32 of the Italian Constitution (Bartholini, 2023).

Access to STP cannot be compared to registration in the Regional Healthcare system, especially regarding health prevention. Under a gender lens, the lack of access to the Regional Healthcare system means that undocumented women face delayed access to screening, treatment and care (Chauvin et al., 2015). In fact, in Italy, migrant women have a lower number of pregnancy visits and echography comparable to native women (Bartholini, 2021).

Undocumented migrant women are entitled to primary and secondary care. However, they are often unaware of it or do not have access due to fear of deportation (Barkensjö et al., 2018; Funge et al., 2020). Low adherence to healthcare hinders identifying the women’s broader health needs and promoting health prevention. Despite the importance of maternity services in ensuring the baby’s and the mother’s health (Raatikainen et al., 2007), migrant women are often reluctant to access maternity services, especially if they are in an irregular administrative position (Adewole et al., 2023). Undocumented women have limited access to contraception, often provided only during family planning visits with the general practitioner, which can result in an unplanned pregnancy (Khin et al., 2021).

3.1.1 The Sicilian healthcare system

The decentralisation of the National healthcare System, firstly at a regional level and later at a district level, led to an asymmetrical and heterogeneous implementation of the migrants’ and natives’ entitlement to healthcare (Giarelli, 2019). To analyse undocumented migrant women’s healthcare endowment, it is essential to provide an accurate framework of the regional socio-health policies regarding resident and non-resident migrants living in the Sicilian Territory.

In Sicily, the governance of migrant’s health is mainly coordinated by the Regional Health Department that has emanated in 2012 the Linee Guida per l’assistenza sanitaria ai cittadini stranieri (extracomunitari e comunitari) della Regione Siciliana13 and in 2017 the Piano di Contingenza Sanitario Regionale Migranti Modalità operative per il coordinamento degli aspetti di salute pubblica in Sicilia, along with the WHO, Italian Ministry of Health and Region of Sicily (2017).14 Recently the Regional Family, Social and Labour Policies Department has published the Piano Triennale per l’Accoglienza e Inclusione 2014–201615, previewed by the Regional Law for inclusion and receiving, no. 20 of the 29th July 2021 that also recognizes migrant’s entitlement to health.

The regional legal framework foresees the registration in the Sicilian Healthcare system and the attribution of a general practitioner for undocumented migrants with a STP. The region has nine ASP-Azienda Sanitaria Provinciale day hospitals, one in each province, and one voluntary day hospital with access to the Regional Recipe book (NAGA-SIMM, 2024). The day hospital of Palermo has a specialised team composed of two general practitioners, one social worker and a nurse specialised in the care of undocumented migrants. In addition, there is a gynaecological office open three times per week that has the support of cultural mediators in English, French, Spanish and Pidgin English. Despite an orientation service to support patients in navigating healthcare, which is exceptionally dedicated to migrants, the multidisciplinary team is limited to the Province of Palermo (Bartholini, 2023). Therefore, in Sicily, where migrant communities are widely spread in the territory, the existence of just 1 day hospital in Palermo is insufficient to respond to the necessities of all the migrant communities on the island. However, non-profit organisations, such as Medici Senza Frontiere16, MEDU-Medici per I Diritti Umani17, Emergency18 and Intersos19, tend to fulfil this gap by providing first care services to migrants in the other Sicilian provinces.

3.2 The theory of fundamental causes

In the last century, the relation between low socioeconomic status and illness has been a focus point of health sociology (Kadushin, 1964). In the 90s, scholars Link and Phelan (1995) proposed the Theory of Fundamental Causes that highlights the relation between social conditions and health outcomes. According to the authors, social conditions, such as socioeconomic status and social support, “are likely fundamental causes of disease,” because they embody access to important resources, affect multiple disease outcomes through multiple mechanisms, and consequently maintain an association with disease even when intervening mechanisms changes” (Link and Phelan, 1995: p. 80). Social conditions are “everything from relationships with intimates to positions occupied within the social and economic structures of society (…) like race, socioeconomic status, and gender” (Link and Phelan, 1995: p. 81). Social conditions, such as gender, citizenship, race/ethnicity and work class determinate the position that the individual occupies in the civic stratification (Morris, 2002).

In the last decades, more attention has been given to the contribution of forms of social, economic and political stratification to health disparities within immigrant groups (Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2012; Viruell-Fuentes et al., 2012; Carruth et al., 2021; Bilecen, 2019). In the case of undocumented migrant women, the intersection of race/ethnicity, gender and alien administrative status can create differential vulnerability, determining their power in accessing social, economic and cultural capital (FRA, 2015; Torres and Young, 2016). In fact, in terms of health access, gender and undocumented status operate as structural determinants of inequality that, in many welfare states, hinder the access of undocumented migrant women to healthcare, exposing them to multiple inequities (Dahlgren and Whitehead, 1991; Lombardi, 2005).

Undocumented migrant women represent a specific category highly marginalised at the policy level (Pellicani and Ince-Beqo, 2024), primarily due to their irregular administrative status (Funge et al., 2020). Literature highlights how the illegal status also limits their access to high economic capital in the destination country (Alarcón et al., 2012; Min et al., 2008), leading undocumented migrant women to a situation of social marginalisation and segregation (Brabeck and Xu, 2010; Chaudry et al., 2010; Yoshikawa, 2011). In particular, the lack of a legal status hinders their access to contract labour rights, often resulting in precarious work conditions, a lack of safety work measures and low income (Rosen, 1979; Aldridge et al., 2018). Consequently, a low income enhances the subalternity of undocumented women, pushing them to segregated areas with poor housing conditions, often lacking hygienic and sanitary facilities, which can highly influence their wellbeing (Dalmau-Bueno et al., 2021).

The inhabitation of undocumented migrants in a segregated milieu can restrict their interactions with native speakers, hindering the adoption of the culture of the host country, including values, roles and social norms. The lack of interaction with autochthonous, not only can result in the absence of acknowledgement of the language and the cultural codes of the reception country (Gonzales et al., 2013), but it can also hamper the undocumented migrants’ understanding of bureaucratic procedures and health literacy in the medicalised host country (Agudelo-Suárez et al., 2010; Gushulak et al., 2011; Malmusi et al., 2010). On the other hand, ingroup interactions can often develop ethnic social capital (Esser, 2004), which can be helpful for the regularisation process of undocumented migrants. In particular, co-nationals can be intermediaries between the reception culture and the country of origin and provide undocumented migrants with guidance on bureaucratic procedures and linguistic support in healthcare settings (Khin et al., 2021).

Literature reports how the individual’s network work can be a social asset (Lin, 2001), by facilitating access to work (Hyyppa, 2010) and bridging social capital and connections (Putnam, 2000). Besides ethnic social capital, undocumented migrants can also develop outgroup social capital. Civil society stakeholders can support migrants, especially third-country nationals, to enhance their endowment and diminish their exposure to differential vulnerabilities and risks (Genova and Terraneo, 2020). In particular, social capital can improve access to economic and cultural assets “that can be used to avoid risks or to minimise the consequences of disease once it occurs” (Phelan et al., 2010: p. 29).

Fundamental causes theory posits that institutional health interventions can potentially reduce health disparities rooted in low economic status, thereby improving individual well-being. An individual’s poor well-being can trigger a “give-back effect,” meaning that illness can act as a catalyst, connecting the individual to healthcare services. This connection increases knowledge about the disease and health in general, fostering greater equality (Link and Phelan, 2010). Healthcare systems, indeed, can help reduce the impact of social disparities, risks, and health inequities faced by individuals in the lower tiers of social stratification (Mackenbach, 2003). However, the confrontation with institutional settings for undocumented migrant women can be settings of distress and multilayered discrimination (Lombardi, 2005).

Women are mainly exposed to discrimination in health settings: from a utilitarian-procreative perspective, since they are often only seen as reproductive agents; from an inequality perspective (Giarelli and Venneri, 2009). Furthermore, women are often more exposed to social inequalities, having less access to economic, social and cultural capital (Lombardi, 2005). The interaction between healthcare professional and undocumented migrant women can be marked by, on one hand the deprivation of the women’s legal status and the lack of cultural capital of the reception country, that can result in the women’s emotional and psychological distress as well as on the perpetration of discriminative behaviours in healthcare and administrative settings (Barkensjö et al., 2018; Funge et al., 2020).

All these factors can expose undocumented migrant women to the inability to prevent, confront, resist and recover from the impact of the illness (Grabovschi et al., 2013). Health entitlement of undocumented migrant women does not entail their endowment; in fact, literature has identified several factors that impede women’s access to healthcare (Lombardi, 2005; Pérez-Sánchez et al., 2024; Barkensjö et al., 2018; Funge et al., 2020). The theory of fundamental causes, from an intersectional lens, can help in understanding the causes of undocumented migrant women’s healthcare exclusion as well as the contextualisation of risk factors and their incidence on the women’s health.

The access to healthcare from a gender lens requires a multilevel analysis, at a macro level, hic est, the structure of the healthcare system that does not embrace the necessities of beneficiaries with a migrant background as well as the impact of socio policies that hinder the endowment of undocumented migrant women in accessing socio-healthcare services; at a meso level ̶ the social agents, such as civil society stakeholders, migrant communities, that act as “connections” by contrasting the reproduction of intersectional inequities and facilitating the women’s endowment ̶ at a micro level, that is observable on the application of social norms at an interactional level between the women and the healthcare professionals.

The Theory of Fundamental causes affirms that the individual’s low socioeconomic status negatively impacts the disease’s outcomes, which hinders the individual’s access to resources such as money, prestige and social connections (Link and Phelan, 1995). In this article, the Theory of Fundamental causes is interpreted as it follows: (1) economic capital ̶ access to material resources; (2) cultural capital of the reception country ̶ is the totality of knowledge of Italian language and social norms of the reception country acquired by the individual; and (3) social capital ̶ the number of contacts and social relations used by the individual to pursue the individual’s integration and promotion strategies (Portes, 1998). Based on the theory of fundamental causes, this article explores the hypothesis that undocumented migrant women’s entitlement ̶ the legal right as established by the state normative ̶ differs from their endowment ̶ the effective right or part of it ̶ in accessing healthcare services in Sicily.

4 The impact of fundamental causes in the endowment of undocumented migrant women in Sicily

Undocumented migration is an under-researched issue (Triandafyllidou, 2016b). Literature presenting quantitative data regarding undocumented migrant’s wellbeing and access to health is practically unavailable (IOM, 2022). The lack of available data is not only due to the abscond nature of irregular migration and the difficulty in accessing data, but also to the complexity and fluidity of regular/irregular migration (Anderson and Ruhs, 2010). Migration of third-country nationals in the European Union often surpasses the dichotomy of legal/illegal migration, leading migrants into a fluctuating state of “in-between categories” (Sarausad, 2019). This fluctuating state between documented/undocumented migrants is mainly influenced by alterations of migration laws and policies or specific eventualities based on the change of the migrant’s characteristics (Dauvergne, 2008). For instance, in case the undocumented migrant is identified as a victim of human trafficking or claims asylum, s/he can start a regularisation process.

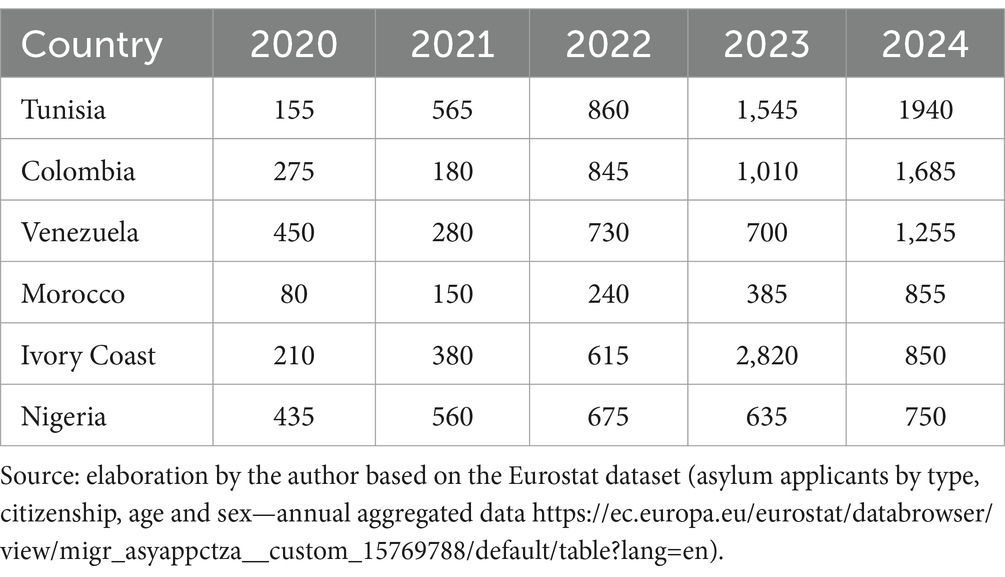

In Italy, the asylum system is one of the main regularisation procedures for third-country nationals who overstay or enter the country illegally. 20 According to Eurostat, in the last 4 years, since 2020, there has been a considerable increase in female third-country nationals claiming asylum in Italy (2020: 4725; 2021: 8530; 2022: 15385; 2023: 20830) (Table 1).21 Despite starting a regularisation process, many asylum claims did not access any form of protection (2020: 709522; 2021: 2780; 2022: 3300; 2023: 2935). This means that many of the female asylum seekers also stayed in illegal and semi-legal conditions in the national territory23 (Jauhiainen and Tedeschi, 2021).

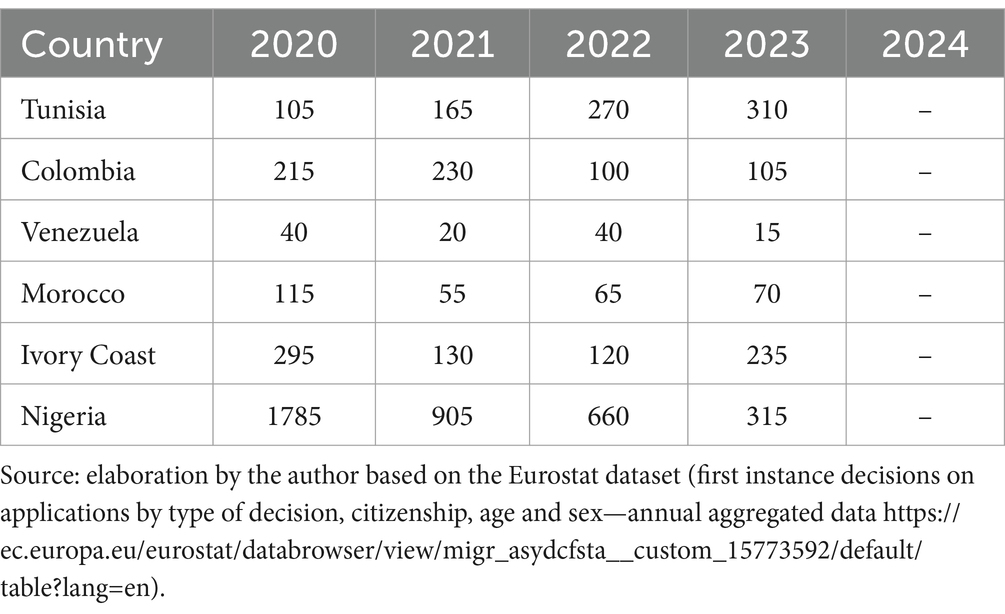

Quantitative data regarding undocumented migrants in Italy is unavailable. Therefore, it is difficult to provide a quantitative framework of undocumented migrant women, mainly segregated by Italian region, gender, and nationality. To have an approximate picture of the potential nationalities with a significant number of women in an irregular administrative situation in Italy, I analysed the rejected asylum claims of third-country nationals, segregated by nationality and gender, based on the Eurostat dataset (Table 2).

Table 1. First instance data of female asylum seekers in Italy segregated by nationality, 2020–2024.

According to Table 2, it is possible to verify that the three main nationalities that did not access any form of protection in the first instance from 2020 to 2024 were Tunisian, Nigerian and Ivorian. However, in the case of Ivorians, literature suggests that France is the leading destination country for Ivorian women (Gastaldi et al., 2024). France and Germany have also been identified as second-entry countries for Nigerian women, yet many have been returned to Italy in the Dublin procedure (Ires, 2023). Interviewed gatekeepers have mainly identified undocumented migrant women from these two countries, as well as from Morocco. According to gatekeeper no. 10, several Moroccan women arrived in Italy through the claims for immigration amnesties.24

Table 2. First instance data of asylum claims rejected to women in Italy, segregated by nationality, 2020–2024.

I know at least three women who came with the Immigration Amnesty decree and had nowhere to sleep. They paid 8,000 euros to come, but their contact person, who had done the contract, was unreachable when they arrived, so they found themselves homeless. Once they could contact their conational, he asked for 800 euros more for the hospitality (Interview no. 10, cultural mediator).

As we can see in the citation below, despite immigration amnesties being considered a legal migration channel, a high level of corruption and illegality has been observed in recent years. Consequently, it has been reported that migrants, including women, arriving in Italy with claims of amnesty are often deceived by employers who have previously agreed to employ them legally, and without a work contract, they remain illegal in the territory (Marchetti et al., 2024; Ero Straniero, 2023).

4.1 The endowment of undocumented migrant women in the regional healthcare system

Health entitlement, education, housing and labour are fundamental pillars in the social safety of the Italian welfare state. As previously mentioned, the Sicilian Regional healthcare entitles undocumented migrants to primary and secondary-level healthcare through the STP. However, poorly functioning health services and migrants’ low economic, social, and cultural capital of the receiving country can limit their access to health care. Furthermore, in most Italian regions, the long waiting lists and the absence of proximity healthcare impose a “distance” between the health professional and the patient (Pasini and Merotta, 2024). In particular, communication between the health professionals and the migrant women is often intermittent. It can hinder access to healthcare services, as many undocumented migrant women have still not acquired the Italian language, due to the lack of cultural mediators in the majority of the hospital services. In fact, due to the precarious communication, undocumented migrants are unable to express their symptoms, which can render the health professional nervous.

You're sick and go to the hospital, but maybe you have a headache and go to an emergency room. In that case, what happens? An increase in people in the emergency room, the doctors' frustration, because they don't have mediators and can't communicate with the patients. The health needs of this population are underestimated when they go to the hospital. You underestimate the patient’s problem and can't take care of the patient, so you send the person home, even if the patient has an important illness (Interview no. 7, doctor).

As soon as we move a little away from the big regional poles [two big cities], the health services for migrants get worse. In the [province], there is a strong need to enhance the knowledge regarding the healthcare system for migrants (Interview no. 15, team coordinator).

I work on another project [name of the project], which also has an area dedicated to women and health. So, several [organisations] try to fill these gaps, but on one hand, they are all faced with the rubber wall of institutions, on the other, the lack of services is real and is the same for everyone [Italians and foreigners] (Interview no. 5, sociolegal expert).

In Sicily, the lack of access to a general practitioner for some non-residents leads some undocumented migrants to go directly to the Emergency Room (ER), which, due to the shortage of health professionals, results in long waiting lists in the ER and patient dissatisfaction. The lack of health professionals hinders undocumented women’s access to healthcare, not only because of the long waiting lists, but also because the dissatisfaction of the patients can often degenerate into aggressive behaviours, leading health professionals to call the authorities, as reported by the interviewees no. 4 and no. 5.25 Consequently, undocumented migrant women are afraid to be identified by the authorities and deported (Dalmau-Bueno et al., 2021).

These people [irregular migrants] are afraid to see either the police or go to the hospitals, even if they have health problems (…). They don't have a STP or a health booklet, so they can't go because they say they don't have a residence. So, they have problems, because maybe they heard that if you don't have documents, the doctors can call the police to let them know that you don't have documents…simple as that (Interview no. 4, cultural mediator).

The vast majority cannot access services because of a logistical issue, precisely the distance from the city centre, and many other problems. Because maybe they don't have documents, they are afraid, and so on (Interview no. 5, sociolegal expert).

Academic literature reports how low familiarity with the healthcare system of the destination country was found to be a determinant of low access (Raymundo et al., 2021; Bains et al., 2021). In particular, administrative barriers are one of the main obstacles to migrant women’s health access (Schmidt et al., 2018; Sami et al., 2019; Bains et al., 2021; Giraldo et al., 2021). Despite the difficulties of bureaucratic practices, Italy’s different regional health policies and healthcare systems often confuse undocumented migrants. Furthermore, as observed in the interviews no. 7 and no. 6, the intermediaries consider the women’s health perception inadequate to the Western approach to medicine and health, which can also hinder the women’s access to health.

In Sicily, this does not happen [in another region, migrants with the STP have access to the general practitioner], so you understand that maybe a person who has been in [another region] for three months has understood [how the healthcare system works]. The migrant arrives in Sicily and does not know how to behave, because again, everything is different. So, there is also this aspect of the health system being different in each region, where the governance takes place, and it doesn't help in understanding how a system works that is already completely different from the system of departure. For most African countries, territorial medicine doesn't exist. So, you continue to be ill… (Interview no. 7, doctor).

We have personally visited these places, for example, those who live without water, they don't have that [western] perception of the psychophysical well-being, that is, unless you have an accident, unless you have a big problem, they don't go to the doctor because they don't have access to healthcare. Practically, they don't even have a clue how to do it, so they live this way. When you say: ‘Look, you have the right to the doctor, you have to be checked,’ a world opens up for them (Interview no. 6, helpdesk coordinator).

4.1.1 Gender lens

Several factors, such as nationality, gender and identity, determine the individuals’ access to healthcare (Burns, 2017). For instance, the androcentric approach in medicine has hindered women’s access to health. In the migration framework, specific health conditions are highly determined by the premigration, migration and postmigration phases (Kirmayer et al., 2011). Migrant women often arrive in the destination country with severe problems of physical, psychological and reproductive health that hamper their access to adequate health services. These problematics can be the consequence of physical, psychological and sexual violence that they are victims in their origin country, such as genital mutilation (Acharai et al., 2023), during the migration journey (Infante et al., 2013; Fleury, 2016; Bartholini, 2019), but also in the destination country (Pascoal, 2020; Freedman and Jamal, 2008).

Apart from those [problems] of gynaecological nature, etc., which, however, is a common condition to those who come from Libya, but which we also found in those who have been exploited in Italy, because it is undoubtedly a side effect of the activity they are forced to carry out. The girls who arrive after a long period in Libya need psychological support, because they have experienced trauma in Libya (Interview no. 8, anti-trafficking expert).

Indeed, there is a bit of a downturn from this point of view due to the passage and especially the stay in Libya; so, I have had many girls with deplorable sanitary conditions. Or in any case badly, in direct proportion to the months spent in Libya, which are months of total abandonment, of starvation… (Interview no. 6, helpdesk coordinator).

From an intersectional lens, pregnant women should be assisted with a beneficiary-centred approach implemented by a multiprofessional team composed of clinicians, healthcare planners, and cultural mediators (FRA, 2015). However, health services are absent, especially with an appropriate service for women who require specific assistance, such as those who have suffered genital mutilation.

The biggest problem seems to be health access, especially for women. There were a lot of women, even pregnant women, who had never had any kind of examination, with all the consequent risks, living in deplorable housing conditions, etc. (Interview no. 5, sociolegal expert).

There are a lot of specialisations lacking in the city from a gender point of view. There isn’t a specialised healthcare service for women who have undergone genital mutilation (Interview no. 9, cultural mediator).

Women often have urinary tract infections, and it depends a little on the condition of sexual exploitation. Very often, we have to accompany women to do abortions or to treat infections related to the female genital apparatus. (…) Yes [access to the voluntary pregnancy interruption], again it depends a little on where you are, in the sense that in [name of the city] there are guaranteed services, in [name of another city] it is much more difficult, even if in [name of the second city] the doctors are all objectors, so you have to make the accompaniments 70, 80 km away from the city (Interview no. 7, doctor).

Sexual violence, especially in the migration path to Italy, sexual exploitation can result in unwanted pregnancies when women cannot access contraceptive methods (Khin et al., 2021) or voluntary interruption of pregnancy in healthcare services. However, in this case, the bureaucratic process can hinder the pregnancy termination, since some women find out about their pregnancy near the 90-day limit, thus intermediaries try to accelerate the process.

In more serious cases, yes, because pregnancy is often discovered at the 90-day limit. Time becomes precious, and not to mention that they have an alien status, so you have to go through the health system before you can have an abortion. This also increases the time and delays it further (Interview no. 7, doctor).

The very long waiting list in the hospital leads many women to perform homemade pregnancy terminations (Interview no. 9, cultural mediator).

From an intersectional lens, besides the difficulty in navigating in the regional healthcare system as well as the lack of appropriate services for women, other fundamental causes can hinder undocumented migrant women’s endowment to health such as their low economic capital, their cultural capital of the reception country, including language and cultural barriers, as we will observe in the following paragraphs.

4.2 The fundamental causes

4.2.1 Low economic capital

The irregular administrative status often pushes migrant women into segregated, informal and illegal/ semilegal spaces, which can heavily determine their socioeconomic status. Economic hardship leads undocumented migrants to work in hazardous conditions and live in poor conditions that lack sanitary facilities or in overcrowded houses (Pascoal and Tortorici, 2023). In the study of Cimino and Pascoal (2024), housing conditions highly influence migrant workers’ health endowment, not only due to the lack of sanitary facilities, which leads to low hygienic conditions of migrants, but also due to the isolation of the dwelling. In particular, undocumented migrants, due to their inability to access legal residence, are only able to contract precarious, unwarranted housing in peripheral and segregated neighbourhoods that are often unprovided with public transport and lacking contact with public services (Márquez-Lameda R., 2022; Márquez-Lameda R. D., 2022).

They live in uninhabitable houses without electricity or water. We are speaking about abandoned houses that are under construction and have not been completed. (…) These houses are for two or three people, but you find ten/fifteen people. From housing exploitation to labour exploitation to health exploitation (…), all this is exploitation (…). The houses where they live are uninhabitable, but unfortunately, they live there, they are sick and cannot go to the hospital (Interview no. 4, cultural mediator).

Emergency has a mobile unit in the heart of [name of the city], and can receive patients who otherwise would not have access to healthcare. We are talking about women and minors, and we have met a lot of children whose problems are due to a lack of hygiene, because they often live in places where there is no running water, no toilets, no bathroom, and so on. There were a lot of women, even pregnant women, who had never had any kind of examination, with all the consequent risks, living in deplorable housing conditions, etc. (Interview no. 5, sociolegal expert).

In other towns, sometimes we got in touch with the general practitioner and then got the prescription, sometimes we provided the medical service directly, sometimes we referred them to the medical guard. Considering, however, that the difficulty in [the name of the place] is that the lack of transport doesn't make it easy for you to access treatment, because if you are in the abandoned cottage, you cannot get to the doctor's office (Interview no. 7, doctor).

It is possible to understand from the interviewees no. 5, no. 7 and no. 4 that poor housing conditions, in particular the lack of electricity and running water as well as sanitary facilities, tend to aggravate the women’s hygienic conditions, and consequently, determine the well-being of undocumented migrant women. Furthermore, according to Interviews no. 5 and no. 7, the peripheral dwelling location hinders the physical access to healthcare services. It is interesting to understand that this access is only allowed based on the intervention of nonprofit organisations that provide services, orientation, and healthcare services. Besides living in poor housing conditions, the subalternity of undocumented women hinders their ability to claim labour rights, which can contribute to the enhancement of health inequalities (Aldridge et al., 2018).

The lack of contracting power leads undocumented migrants to work in low-skilled sectors characterised by precarious conditions, high instability, and informal employment (Alonso-Villar and del Río, 2013; Stanek et al., 2020). In Sicily, undocumented migrant women are often unable to exercise their work rights due to their vulnerable position, which exposes them to hazardous labour conditions, such as a lack of appropriate safety materials and working several hours per day without a legal work contract (Palumbo and Sciurba, 2018). Their hazardous working conditions can result in health problems, as mentioned by interviewee no. 5. Furthermore, the undocumented migrant women’s poor work conditions often hinder their possibility to access healthcare services, as due to the distance of their work location from an hospital structure as due to the impossibility in attending medical visits during work hours (Gea-Sánchez et al., 2017; Villarroel and Artazcoz, 2016; Lombardi, 2016).

They can suffer various types of accidents at work, from the most serious to the simplest, which is perhaps a fracture, a sprain and a perennial backache. Therefore, all physical problems are linked to that kind of work without a safety device. So, we found people with crushed feet because a weight fell in their foot and they didn’t have appropriate safety material, people who couldn't get up because of back problems, because they were picking nine hours a day, and then you can't do it, etc. (Interview no. 5, sociolegal expert).

On the contrary, it is very easy for them to send you away directly, because there is no culture of work legality. So, for many, it was almost like a normal thing [not going to the hospital], let's say you get hurt, because you're in your twenties or thirties, and then you start again and so on. We are all talking about workers from countries where public health is what it is, so maybe they are already not used to, let's say, frequenting it. (…) The problem is that the hospital may also be far from their home. If you go for treatment, you must take a few days off work; it is not certain that your employer will accept this (Interview no. 5, sociolegal expert).

If you work in the countryside, you wake up very early in the morning, maybe in the middle of the afternoon, come back, eat, and then sleep because you're tired. Therefore, the doctor's office opens at 8 o'clock, and you cannot get there, even according to the timetable (Interview no. 7, doctor).

4.3 Cultural capital of the reception country and communication impairment

Communication between health professionals and patients with a migrant background has been pointed out as one of the central critical nodes in accessing care services (Goodwin et al., 2018; Giraldo et al., 2021; Khin et al., 2021; Gilder et al., 2019). The women’s inability to communicate satisfactorily in the language of the receiving country, as well as the absence of cultural mediators in healthcare settings, is a primary determinant factor that hinders their access to care services (Grotti et al., 2018; Schmidt et al., 2018; Crowther and Lau, 2019; Sami et al., 2019; Bains et al., 2021; Khin et al., 2021; Cai et al., 2022). According to the EBCOG-The European Board and College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology European Standards of Care (Smith et al., 2016), interpreting arrangements should be put in place, especially in emergency or acute situations, in a comprehensible language to undocumented migrant women. For better access to health, migrant women tend to seek support information in their native language (Cai et al., 2022) or from health professionals with the same ethnic background. Yet, these sources are often unavailable (Khin et al., 2021). Language barriers can create impatience among health professionals, usually hindering an accurate screening of the migrant’s needs (Schmidt et al., 2018).

The problem is the lack of cultural mediators, especially from Bangladesh and Romania. Therefore, we have difficulty finding cultural mediators in our territory, especially women who speak these languages (Interview no. 2, project coordinator).

The lack of cultural mediation is a problem that affects the entire Sicilian territory (Interview no. 9, 07/12/2024, cultural mediator).

The Sert26 service told me about an outpatient service, but without a cultural mediator, this person has enormous logistical problems in reaching the service. Thus, the patient would have arrived and could not express herself/himself. How do you explain your symptoms if you don't have a cultural mediator? (Interview no. 8, anti-trafficking expert).

Sometimes, to overcome language and cultural barriers, healthcare structures provide patients with cultural mediation services; however, migrant women’s unawareness of their existence limits their access to it (Schmidt et al., 2018; Bains et al., 2021). Cultural mediators facilitate linguistic communication and are essential in explaining the hospital culture to the patient and the patient’s culture to the health professionals (Morrone et al., 2017). Hospital culture and the functioning of the Regional Healthcare system are significant challenges to the individual’s health endowment (Giarelli, 2018). Migrant women’s unfamiliarity with diseases (Gilder et al., 2019) and correspondent medical terminology used by the health professionals hampers not only the women’s understanding of the staff’s instructions (Sami et al., 2019), but also their capacity in expressing their health conditions to the professionals, which consequently hinders an accurate/adequate medical diagnosis (Grotti et al., 2018).

We have to accompany them [migrants] at a logistical level, because some do not have a bicycle or a car to get from one place to another. We get there and have to accompany them linguistically, in the sense that they do not understand what they have [in terms of health], so we have to help them and explain what they need (Interview no. 4, cultural mediator).

Thus, one of the projects that has been most successful is precisely the one that provides information to working women, in most cases also through mediators, and this has enabled them to access many services, counselling centres, etc. (Interview no. 5, sociolegal expert).

This is thanks to the information one gives to people and the cultural explanation, because it is not just, as I said before, ‘look you have hepatitis’. First of all, we are trained, I am saying this starting from the person who drives the mobile clinic to the doctor, to everyone … We all have to be trained because we all have to give a complete answer, maybe a little answer that makes the person wait his/her turn to meet the doctor. Afterwards, we all have to be aware of certain dynamics (Interview no. 7, doctor).

Communication problems can lead to unfavourable experiences, originating a sense of inadequacy, distrust and embarrassment of undocumented migrant women in healthcare settings (Grotti et al., 2018; Crowther and Lau, 2019; Sami et al., 2019; Bains et al., 2021; Schmidt et al., 2018). Gender literature on migration reports the necessity of establishing a relationship of trust with the healthcare providers (Crowther and Lau, 2019; Sami et al., 2019). However, the constant change in health professionals does not allow for the establishment of a relationship based on trust between health providers and patients. Therefore, trust is mainly established with the cultural mediator accompanying the women. According to interview no. 4, reliability and establishing a trust relation are the most critical aspects to enhance undocumented women’s endowment. Establishment of trust with the intermediaries can also be challenging, as reported in interview no. 4, since often many stakeholders are providing the same service. Still, sometimes the services cannot offer concrete solutions to the beneficiaries. In this case, the constant presence of a team of health professionals can represent a safe place, where women are not only aware of their geographical presence, but are also secure in communicating with the health professionals.

If you go straight to the point, many of them retreat immediately. Thus, you must look for other ways to get there without being in a hurry. If you say, ‘If you have this problem, you can do this, and they [the association] will call you. They [the women] say no because, unfortunately, so many other associations may go around and start, but then don’t do anything. Therefore, if they tell you ‘no, forget it, they came here before and did nothing’, what do you do? It's difficult; you have to be as reliable as possible. It's a process because the person first must trust what you say; otherwise, they don't trust (Interview no. 4, cultural mediator).

Emergency is fixed in [name of the city]. Then this mobile clinic moves daily to a different place with a multidisciplinary team formed by a doctor, a nurse, a psychologist and cultural mediators who speak several languages, which does not exist in the hospital in [name of the city]. Thus, this whole series of services put together gives the undocumented migrant the chance to trust the health professionals (Interview no. 5, socio-legal expert).

I always come back to the same case of the patient who has pancreatic cancer, because you have to find the right way without frightening the person, and this is not up to me to decide. It is decided mainly by those who specialise in the psychological field, who give us indications, and by the cultural mediators, who also give their suggestions. In every country, there is the same disease, but in every country, the disease is seen differently. And we try slowly to explain to the person what the disease is, that maybe, as I was saying, pancreatic cancer, despite being a severe disease, you are not a lost case (Interview no. 7, doctor).

4.4 Social capital

Migration represents a complex framework of social relations shaped by structural frameworks, migration regimes and welfare that heavily affect the everyday livelihoods of undocumented migrants (Ambrosini, 2013; Zanfrini, 2016). As previously mentioned, migrants’ category determines the migrant’s access to institutional/political structures in different national contexts (Koopmans et al., 2006). An irregular administrative status can also shape the migrant’s social capital, limiting his/her access to cultural and economic capital, and consequently closing doors to an upward class mobility (Tedeschi and Gadd, 2021).

Undocumented migrant women’s social capital is often connected by interethnic solidarity, particularly relatives and acquaintances of the exact ethnic origin (Triandafyllidou, 2016a), who frequently act as intermediaries. Migrant networks can be resourceful sources in terms of language support and information for migrant women who have poor linguistic skills and are unable to navigate the healthcare system (Giraldo et al., 2021).

Civil society stakeholders have proven essential to claiming migrants’ rights (Isin and Nielsen, 2008) and supporting women in overcoming difficulties in accessing health services, especially regarding bureaucratic barriers (Schmidt et al., 2018). Due to misinformation and discriminatory behaviours, administrative functionaries who exercise their power discretionarily often block undocumented migrant women’s endowment. In this case, a native speaker or someone representing an Italian civil society organisation can guarantee the women’s endowment.

Thus, if I call you [health services]and say: Look, I'm sending you a person, you let them in if they come alone. I don't need to go, just the cultural mediator. All the practitioners, in general, at ASP, I mean, social workers and the authorities. I used to accompany migrants, in case of difficulty, because there was a propensity to open up when there was someone [from the organisation]to support them. If they are alone, they tend to close the doors: the Police, the ASP, the offices in general. Very common, especially at the municipality. Alone, they could never make it [go in] because they send you back. Already, we have enormous difficulties with them, but if they go alone, they certainly won't make it (Interview no. 6, helpdesk coordinator).

We explain the procedures because one of the biggest myths is: ‘I am sick, but if I go to the hospital, they will arrest me’. No, we can accompany you. For example, we went to hospitals to try to mediate with the administration to facilitate access for people. We went to the ASP to understand how to issue the STP code. For example, there is this STP service, and we took the location of the registry office and the STP outpatient clinic inside the hospital. Thus, if the person needs, we give the position directly on a sheet where everything is written in Italian with the doctor's phone number and mine. If something is needed, we can act as telephone mediators (Interview no. 7, doctor).

It is well-known that social capital and communitarian welfare resources reduce the individual’s systemics vulnerabilities (Mechanic and Tanner, 2007) and, thus, enhances the individual’s access to resources, not only on cultural capital, especially in the affirmation of claiming rights, but also to provide the information on their health entitlement and bureaucratic procedures.

We do national health service registration for those with a residence permit or apply for the STP. We do this; we always do it, so they can have the doctor even for a few months. For those who do not have a document, maybe with a certificate, you can do it for two months and in this period that allows you to do a check-up, do the exams and the urgent things that you have to do, and then try to renew it. (…) We helped many women when we had the housing, because we were giving hospitality, even if they didn't sleep there, thus we managed to renew many health records. We managed to do a lot of STPs even before the closure. We made the rounds of calls, summoned everyone, and renewed all the STPs and the treating doctor. Even if it is difficult, because if a migrant who is sick comes, but does not have a place, the ASP practically asks you for your domicile and residence. If s/he doesn't have it, you can't renew it (Interview no. 6, helpdesk coordinator).

The social and legal services of Arci Porco Rosso in Palermo support those who have health problems, or undocumented migrants with problems in having STP or the health booklet, because some don’t have documents, or they do not know about their rights in accessing healthcare. (…) And then some need to be helped because they are victims of exploitation, and they are afraid, because maybe the employer tells them that if they call the police, they will arrest them. Thus, we have to orient them to understand better what is there (Interview no. 4, cultural mediator).

As affirmed by interviewee no. 4, civil society stakeholders can guide undocumented migrant women through the different services. The intermediaries’ guidance is often fundamental to enhancing the undocumented women’s endowment, especially since they are often unaware of their positionality in a “category” and, therefore, unable to understand the bureaucratic procedure to regularise their administrative status and access healthcare services.

5 Conclusion

Undocumented migrant women are socially and structurally exposed to multiple health inequities due to discrimination, gender role, gender-based violence and feminisation of poverty. This research confirms the interdependence between health endowment and migrant categories and how “fundamental causes” can hinder the endowment of undocumented migrant women to the Sicilian healthcare, even if the regional system provides their access to primary and secondary level healthcare.

At a macro level, the lack of human resources of the public health system seriously aggravates the undocumented migrant women’s endowment to healthcare. In particular, the shortage of health professionals lengthens the patient’s waiting lists and directs migrants to the Emergency rooms. Despite the shortage of health professionals affecting both autochthones and non-natives, it has a significant impact on undocumented migrants, since health professionals often call authorities when there are fights in the Emergency rooms.

From an intersectional lens, the health staff shortage has a particular impact on undocumented migrant women. Migrant women arriving in Sicily, through the Mediterranean Central route, can suffer gender-based violence, which often results in severe problems of physical, psychological and reproductive health and sometimes pregnancy. Delaying health screenings and healthcare hampers their access to adequate health services and hampers the possibility of having a voluntary interruption of pregnancy.

The research confirms the existence of fundamental causes hindering undocumented migrant women’s access to healthcare, especially regarding the low socioeconomic status and cultural capital of the receiving country. The cause, as low economic status, influences multiple disease outcomes and enhances differential vulnerabilities of undocumented migrant women. In particular, practitioners reported the incidence of precarious housing and working conditions in women’s health. Precarious housing conditions have an impact on women’s health, especially since the dwellings lack essential services, such as electricity, hydric services and sanitary facilities, which can result in poor hygiene. Furthermore, undocumented migrants often live in isolated or peripheral areas far from public services and without public transport. Low economic capital was also translated into hazardous work conditions. Therefore, undocumented migrant women are often unable to contract decent work conditions, including the possibility to take a day off to cure a health problem.

At a micro level, undocumented migrant women’s cultural capital of the reception country also highly influences their endowment to health services, not only due to their low familiarity with the healthcare system of the destination country, but also due to language and administrative barriers. Although the economic and cultural capital of the host country have been demonstrated to be one of the leading causes that hinder women’s endowment to healthcare, social capital has been confirmed to be an essential resource.

Civil society stakeholders can attenuate migrant women’s exposure to social differentiations, risks and health inequities. Civil society intermediaries can orient them through specialised stakeholders that offer adequate services according to their “migrant legal category” and health and bureaucratic needs. Furthermore, social capital, composed of civil society entities, supports undocumented migrant women in their acts of citizenship and enhances their right to claim rights by providing them with correct information regarding their entitlement. They have a paramount role as direct providers of medical assistance to undocumented migrant women, as socio-legal and linguistic supporters. Furthermore, civil society professionals also enhance women’s rights ̶ through the presence of a cultural mediator or another practitioner ̶, especially in situations where their endowment is blocked by administrative functionaries who exercise their power discretionarily, either due to misinformation or due to discriminatory behaviours.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because only non invasive work was done. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and any institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

RP: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^CEDAW Committee, General Recommendation No. 26 about women migrant workers, para. 5.

2. ^With the term “undocumented migrant women,” the author adopts the definition of “irregular migrant” provided by the European Migration Network refers to a third country female national that “breached of a condition of entry or the expiry of their legal basis for entering and residing, lacks legal status in a transit or host country.” https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/networks/european-migration-network-emn/emn-asylum-and-migration-glossary/glossary/irregular-migrant_en.

3. ^According to Morris (2002) civic stratification is a hierarchal division of individuals within a society based on their legal and citizen status that determines their access to rights, resources and opportunities.

4. ^According to Isin and Nielsen (2008: p. 39) acts of citizenship are “those acts that transform forms (orientations, strategies, technologies) and modes (citizens, strangers, outsiders, aliens) of being political by bringing into being new actors as activist citizens (claimants of rights and responsibilities) through creating new sites and scales of struggle.”

5. ^Please see the definition of cultural capital on the paragraph 3.2 The Theory of Fundamental Causes.

6. ^Street-level bureaucrats (Lipsky, 1980) are professionals exercising a degree of freedom in their work by applying rules and incorporating other relevant considerations (Hill and Hupe, 2021).

7. ^The project is implemented with the colleague Francesca Cimino, research fellow at the University of Ca′ Foscari. The first article of this research “The relevance of multi-level governance on contrasting the social inequity health determinants of exploited migrant workers: A comparison between the Project P.I.U. Su.Pr.Eme. in the Region of Sicily and the Project Common Ground in the Veneto Region” was published in the journal Welfare e Ergonomia, 2024, 1. Doi: 10.3280/WE2024-001009.

8. ^In Italy the residence permit is foreseen in the following cases: (1) Foreign nationals who have entered in Italy with a visa for medical reasons and their caregivers (art. 36 of Legislative Decree no. 286/98); (2) Undocumented migrants in Italy who are in particularly serious health conditions (art. 19 § 2 letter d-bis of Legislative Decree no. 286/98); and (3) To undocumented migrant women in Italy in a state of pregnancy and for 6 months following the birth of their child (Art. 19, § 2, letter d-bis of Legislative Decree no. 286/98). This residency permit, as a result of the Constitutional Court’s ruling no. 376 of 27 July 2000, must also be recognised to the husband cohabiting with the pregnant woman for the same duration.

9. ^Accordo S-R, parag.i 1.2. e 2.4.

10. ^Accordo Stato-Regioni e Province Autonome, n.255/CSR, 20 December 2012, Gazzetta Ufficiale Serie Gen. n. 32 del 7-2-2013 suppl. Ordinario n. 9, paragraphs 1.1.and 2.1.

11. ^Article 35, paragraph 3.

12. ^The Decree Ministry of Economy and Finance, 17 March 2008, 8.27, all. 12 previews the payment exemption to third country nationals that declare an indigent state.

13. ^https://pti.regione.sicilia.it/portal/page/portal/PIR_PORTALE/PIR_LaStrutturaRegionale/PIR_AssessoratoSalute/PIR_Infoedocumenti/PIR_DecretiAssessratoSalute/PIR_Decreti/PIR_Decreti2012/Linee%20guida%20stranieri%2017-10-2012.pdf

14. ^https://pti.regione.sicilia.it/portal/page/portal/PIR_PORTALE/PIR_LaStrutturaRegionale/PIR_AssessoratoSalute/PIR_AreeTematiche/PIR_Altricontenuti/PIR_Pianocontingenzasanitarioregionalemigranti/piano%20contingenza%20A4-2017_Definitivo.pdf

15. ^https://www2.regione.sicilia.it/deliberegiunta/file/giunta/allegati/N.116_21.03.2024.pdf

16. ^https://www.medicisenzafrontiere.it/

17. ^https://mediciperidirittiumani.org/

18. ^https://en.emergency.it/what-we-do/italy/

19. ^https://www.intersos.org/cosa-facciamo/italia/

20. ^In 2023, Italian authorities registered a total of 130,535 asylum claims.

21. ^https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/migr_asyappctza__custom_15744912/default/table?lang=en.

22. ^The higher number of rejections does not only regard the 2020 asylum claims, but also to those of previous years. For instance, only in 2019, 10,305 women claimed for asylum in Italy.

23. ^According to Gonzales (2011: p. 605) semi-legality “moves beyond the binary categories of documented and undocumented to explore the ways in which migrants move between different statuses and the mechanisms that allow them to be regular in one sense and irregular in another.” In this particular case, asylum seekers can ask for appeal or try the reiterate procedure or other forms of permits, such for health reasons, yet it is impossible to determinate the number of rejections in the second instance.

24. ^Third country nationals who apply for a temporary work permit in the agricultural, zootechnical and personal assistance sector. In the last 3 years, the Italian government has augmented the number of claim amnesties (136.000 third country national in 2023, 151.000 in 2024, and 165.000 in 2025).

25. ^Due to the high number of aggression cases in hospitals in Italy, health professionals tend to call immediately the authorities once they see disturbance in the Emergency room. https://www.ilmessaggero.it/en/violence_against_healthcare_workers_continues_in_italy-8345564.html.

26. ^Servizi per le Tossicodipendenze: Healthcare services dedicated to individuals with addiction problems.

References

Abel (2022). Gender and migration data. KNOMAD Paper. Available online at: https://www.knomad.org/sites/default/files/2022-10/knomad_paper_44_gender_and_migration_g.abel_oct_2022_1.pdf (Accessed December 8, 2024).

Acevedo-Garcia, D., Sanchez-Vaznaugh, E. V., Viruell-Fuentes, E. A., and Almeida, J. (2012). Integrating social epidemiology into immigrant health research. Soc. Sci. Med. 75, 2060–2068. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.040

Acharai, L., Khalis, M., Bouaddi, O., Krisht, G., Elomrani, S., Yahyane, A., et al. (2023). Sexual and reproductive health and gender-based violence among female migrants in Morocco: a cross sectional survey. BMC Womens Health 23:174. doi: 10.1186/s12905-023-02307-1

Adewole, D., Adedeji, B., Bello, S., and Taiwo, J. (2023). “Access to healthcare and social determinants of health among female migrant beggars”, in Ibadan, Nigeria. J. Migr. Health 7:100160. doi: 10.1016/j.jmh.2023.100160

Agudelo-Suárez, A., Sousa, E., Benavides, F. G., Schenker, M., García, A. M., Benach, J., et al. (2010). Immigration, work and health in Spain: the influence of legal status and employment contract on reported health indicators. Int. J. Public Health 55, 443–451. doi: 10.1007/s00038-010-0141-8

Alarcón, R., Rabadán, L. E., and Ortiz, O. O. (2012). Mudando el hogar al norte: Trayectorias de integración de los inmigrantes mexicanos en Los Ángeles. Tijuana, Mexico: El Colegio de la Frontera Norte.

Aldridge, R. W., Nellums, L. B., Bartlett, S., Barr, A. L., Patel, P., Burns, R., et al. (2018). Global patterns of mortality in international migrants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 392, 2553–2566. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32781-8

Alonso-Villar, O., and del Río, C. (2013). Occupational segregation in a country of recent mass immigration: evidence from Spain. Ann. Reg. Sci. 50, 109–134. doi: 10.1007/s00168-011-0480-2

Ambrosini, M. (2013). Immigrazione irregolare e welfare invisibile. Mulino: Il lavoro di cura attraverso le frontiere.

Anderson, B., and Ruhs, M. (2010). “Migrant workers: who needs them? A framework for the analysis of shortages, immigration, and public policy” in Who needs migrant workers? Labour shortages, immigration, and public policy. eds. B. Anderson and M. Ruhs (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 15–52.

Bains, S., Skråning, S., Sundby, J., Vangen, S., Sørbye, I. K., and Lindskog, B. V. (2021). Challenges and barriers to optimal maternity care for recently migrated women – a mixed-method study in Norway. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21:686. doi: 10.1186/s12884-021-04131-7

Barkensjö, M., Greenbrook, J. T. V., Rosenlundh, J., Ascher, H., and Elden, H. (2018). The need for trust and safety inducing encounters: a qualitative exploration of women's experiences of seeking perinatal care when living as undocumented migrants in Sweden. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18:217. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1851-9

Bartholini, I. (2019). Proximity violence in migration times: A focus on some regions of Italy, France and Spain. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Bartholini, I. (2021). Fenomeni migratori, vulnerabilità femminile e accesso ai servizi sanitari presso l’ARNAS Civico di Palermo. Salute e Società, XX 3, 159–174. doi: 10.3280/SES2021-003010

Bartholini, I. (2023). Il Sistema sanitario siciliano: Uno sguardo bifocale alle traiettorie e alle prospettive. Soveria: Rubbettino.

Bilecen, B. (2019). “Social transformation(s): international mobility and health” in Refugee migration and health: Challenges for Germany and Europe (1 ed., pp. 39–48). (migration, minorities and modernity; Vol. 4). eds. A. Krämer and F. Fischer (Cham: Springer).

Bolaffi, G., Bracalensi, R., Gindro, S., and Braham, P. (2003). Dictionary of race, ethnicity and culture. London: SAGE.

Brabeck, K. M., and Xu, Q. (2010). The impact of detention and deportation on Latino immigrant children and families: a quantitative exploration. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 32, 341–361. doi: 10.1177/0739986310374053

Burns, N. (2017). The human right to health: exploring disability, migration and health. Disabil. Soc. 32, 1463–1484. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2017.1358604

Cai, D., Villanueva, P., Stuijfzand, S., Lu, H., Zimmermann, B., and Horsch, A. (2022). The pregnancy experiences and antenatal care services of Chinese migrants in Switzerland: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22:148. doi: 10.1186/s12884-022-04444-1

Carmona, R., Alcázar-Alcázar, R., Sarria-Santamera, A., and Regidor, E. (2014). Frecuentación de las consultas de medicina general y especializada por población inmigrante y autóctona: una revisión sistemática. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 88, 135–155. doi: 10.4321/S1135-57272014000100009

Carruth, L., Martinez, C., Smith, L., Donato, K., Piñones-Rivera, C., and Quesada, J. (2021). Migration and health in social context working group. Structural vulnerability: migration and health in social context. BMJ Glob. Health 6:e005109. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005109

Chaudry, A., Capps, R., Pedroza, J. M., Castañeda, R. M., Santos, R., and Scott, M. M. (2010). Facing our future: Children in the aftermath of immigration enforcement. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute.

Chauvin, P., Simonnot, N., Vanbiervliet, F., Vicart, M., and Vuillermoz, C. (2015). Access to healthcare for people facing multiple vulnerabilities in health in 26 cities across 11 countries. Report on the social and medical data gathered in 2014 in nine European countries, Turkey and Canada. Paris: Doctors of the World – Medecins du monde international network.

Cimino, F., and Pascoal, R. (2024). The relevance of multi-level governance on contrasting the social inequity health determinants of exploited migrant workers: a comparison between the project P.I.U. Su.Pr.Eme. In the region of Sicily and the project common ground in the Veneto region. Welfare e Ergonomia 1, 115–136. doi: 10.3280/WE2024-001009

Crowther, S., and Lau, A. (2019). Migrant polish women overcoming communication challenges in Scottish maternity services: a qualitative descriptive study. Midwifery 72, 30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2019.02.004

Dahlgren, G., and Whitehead, M. (1991). Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Stockholm. Sweden: Institute for Futures Studies.

Dalmau-Bueno, A., García-Altés, A., Vela, E., Clèries, M., Pérez, C. V., and Argimon, J. M. (2021). Frequency of health-care service use and severity of illness in undocumented migrants in Catalonia, Spain: a population-based, cross-sectional study. Lancet Planet Health 5, e286–e296. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00036-X

Diderichsen, F. (2004). Resource allocation for health equity: Issues and methods. Washington DC: The World Bank.

Ero Straniero (2023). La lotteria dell’ingresso per lavoro in Italia: i veri numeri del decreto flussi. Available online at: https://erostraniero.it/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Dossier-decreto-flussi-dicembre-2023.pdf (Accessed December 23, 2024).

Esser, M. (2004). Does the “new” immigration require a “new” theory of intergenerational integration? Int. Migr. Rev. 38, 1126–1159. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2004.tb00231.x

Fleury, A., (2016). Understanding women and migration: a literature review. Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration. Paper 8. Available online at: http://atina.org.rs/sites/default/files/KNOMAD%20Understaning%20Women%20and%20Migration.pdf (Accessed October 24, 2024).

FRA (2015). Cost of exclusion from health care: The case of migrants in an irregular situation. Luxembourg: European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights.

Freedman, J., and Jamal, B. (2008). Violence against migrant and refugee women, Jane Freedman and Bahija Jamal in the EuroMed region. Case studies: France, Italy, Egypt & Morocco. Available online at: https://www.cittametropolitana.bo.it/sanitasociale/Engine/RAServeFile.php/f/women_EMHRN.pdf (Accessed November 23, 2024).