- MOBILE Center of Excellence for Global Mobility Law, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

This study analyzes how the credibility of transgender asylum claimants in the Danish asylum system is assessed by decision makers. The analysis takes an empirical mixed methods approach to investigating how credibility of transgender asylum claimants is evaluated. By combining statistical analysis of a dataset with ~15,000 case summaries from the Danish Refugee Appeals Board and results from an original experimental study, we present three key findings. First, our study finds a rise in the number of claims based on sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGIE) over time, underscoring the need for a better understanding of how these claims are assessed. Second, results from our experimental study indicate that transgender claimants who have had gender-affirming medical intervention in their transition are more often deemed credible and granted refugee status. Furthermore, the experimental study observes that women and LGBT+ participants are more likely than men and non-LGBT+ participants to deem a claimant’s narrative credible and grant them refugee status. These findings suggest that transnormative ideas of how a transgender claimant ‘legitimately’ transitions has an effect on decision makers’ credibility assessments, and that the background characteristics of the decision maker has a systematic effect on their decision-making. In the article, we critically reflect on the consequences of relying on stereotypes to assess a claimant’s credibility, both in terms of non-compliance with international guidelines and of risking unjust outcomes for asylum claimants.

Introduction

Research and practice have shown that credibility assessment, or the procedure of deciding which parts of an asylum claim can be accepted as facts of the case, is often the single most important element in determining an asylum claimant’s needs for protection (Kagan, 2003; UNHCR, 2013). For claims regarding sexual orientation and/or gender identity and expression (SOGIE),1 which require decision makers to examine the authenticity of an inner experience, credibility is central (Millbank, 2009b; Jansen and Spijkerboer, 2011; Rehaag and Cameron, 2020). To add to the difficult task of assessing the authenticity of a claimant’s internal experience, claims made on the basis of SOGIE often have little external evidence compared to other claim types (Zisakou, 2021). Whereas in other claims, external evidence such as documentation of membership to a political party or attendance to public events may be available to and verifiable by migration authorities, SOGIE claims often rely solely on personal testimony and country of origin information (COI). Taken together, the difficulty of verifying the authenticity of an internal experience combined with the relative scarcity of material evidence available in SOGIE claims renders credibility assessment especially crucial for these claim types to be granted protection.

Although decision makers are given guidelines for how to conduct credibility assessments (UNHCR, 2010, 2013), research highlights that there may be significant variation in how credibility is approached on the national level, leading both national asylum authorities and scholars to debate how best to conduct credibility assessments in an effort to harmonize the practice (Liodden, 2020; Høgenhaug et al., 2023; Gill et al., 2025). To provide guidance on how to evaluate SOGIE claims, the UNHCR has published the Guidelines No. 9 (the Guidelines) on how to best interview and adjudicate claims where the motive is based on being LGBT+, including definitions of what it means to be lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (UNHCR, 2012, para. 63(iv)). These guidelines were an essential supplement to the 1951 Refugee Convention (the Convention), which does not mention sexual orientation or gender identity (UNHCR, 1951). Even as the exclusion of sexual orientation and gender identity from the wording of the Convention has in practice caused persistent issues for LGBT+ claimants (Dustin, 2018), claims made on the basis of SOGIE are now widely known to fall under the membership to a ‘particular social group’ (PSG) basis of claiming refugee status.

Alongside providing definitions for SOGIE claims, the Guidelines advise on how to conduct interviews in a sensitive way and stress that “decision makers understand both the context of each refugee claim, as well as individual narratives that do not easily map onto common experiences or labels.” In the Guidelines, the UNHCR explicitly discourages decision makers from relying on stereotypes when assessing the credibility of a claim. While the Guidelines are not legally binding, they are generally accepted as soft-law instruments that are authoritative in the context of statutory interpretation of the Convention (Lindholm, 2014). In this study, we therefore take the UNHCR Guidelines to be the normative legal standard decision makers should strive to fulfill.

According to UNHCR Guideline definitions, homosexual men and women alike are described as enduring “physical, romantic and/or emotional attraction to others of the same gender as themselves” (UNHCR, 2012, para. 10). In its definition of gay men, the guidelines make explicit that decision makers should “avoid assumptions that all gay men are public about their sexuality or that all gay men are effeminate” thereby discouraging relying on stereotypes about homosexual men. The UNHCR further highlights that because gay men numerically dominate claims based on sexual orientation and gender identity, it is important for decision makers to refrain from using gay men as a ‘template’ for other SOGIE claims.

The Guidelines note that gay and lesbian claimants may previously have engaged in heterosexual relationships, but their sexual orientation is generally presented as static and fixed. In the definitions of lesbians (but not of gay men) it is mentioned that a lesbian might have only had few or no lesbian relationships and may only later in life identify as a lesbian. Regardless, for gay men and lesbians alike there is a binary definition of a before and after coming out. In contrast, the Guidelines’ definitions of bisexual and transgender claimants emphasize fluidity in identity and expression, describing bisexuals as ‘fluid’ or ‘flexible’. Similarly, the Guidelines emphasize that transgender claimants may “dress or act in ways that are often different from what is generally expected by society on the basis of their sex assigned at birth” but that “they may not appear or act in these ways at all times” (UNHCR, 2012).

In the case of transgender claimants in particular, the Guidelines specifically note that the transition to “alter one’s birth sex” can be a complex process involving a range of legal and medical adjustments, and that “not all transgender individuals choose medical treatment or other steps to help their outward appearance match their internal identity” (UNHCR, 2012). The UNHCR explicitly states that the non-conformity to “accepted binary perceptions of being male and female” is what presents transgender individuals with a risk of persecution. It is further highlighted that “altering one’s birth sex” is not a one-step process with a ‘before’ and ‘after’, and that while many might take legal or medical steps towards affirming their gender, it is not all trans people who include these steps in their transition (UNHCR, 2012, para. 63(iv)). Similar to the recommendations for assessing lesbian claims, The Guidelines note that while probing the experience of having been ‘different’ since childhood is helpful to establish identity, some may not realize their gender identity until later in life (UNHCR, 2012, para. 63(ii)).

While the fluidity and nonlinearity of queer identity is emphasized in the Guidelines and adjudicators are dissuaded from relying on stereotypes, the Guidelines have faced criticism for understating the diversity of experience of sexual minorities around the world, leaving claimants vulnerable to hidden Western-centric biases of adjudicators (LaViolette, 2010). Further, they have been criticized for lacking an intersectional lens as to how both sexual and racialized stereotypes of adjudicators might disproportionately affect some claimants more than others (LaViolette, 2010).

In addition to the flaws imbedded in the text of the Guidelines, the discretionary nature of the task of assessing credibility leaves the procedure vulnerable to hidden biases, perhaps even unbeknownst to decision makers themselves. While the Guidelines explicitly dissuade the use of stereotypes in decision making, they presume that migration authorities have a conscious awareness of their own biases, and in turn, an ability to decide not to ‘use’ them in their decision-making. In other words, the Guidelines assume a direct relationship between what scholars previously have called decision writing and decision making, or the connection between written legal text and the legal decisions that are made by a human. As previous research has shown, the link between decision writing and decision making is not always direct, as decision makers’ actions may contradict the written explanation they give for making a decision (Rehaag and Cameron, 2020). Thus, for legal scholars interested in improving fairness in RSD for claims made on the basis of SOGIE, the analysis can be made on two levels: First, scholars can study decision writing, how the Guidelines compare to legal and psychological standards put forward by experts. And second, scholars can study decision making, how decision makers evaluate SOGIE claims in practice, and to what extent their decision-making is in compliance with the Guidelines. The research conducted for this study engages with legal decision making, investigating the hidden biases that underpin how migration authorities make decisions about credibility in SOGIE claims.

Previous research on credibility assessments has documented the large influence of decision makers’ personal biases about the claimants’ behavior, only partly in line with psychological research on memory and decision making (Herlihy et al., 2010; Skrifvars et al., 2022). Scholars have found that to establish credibility, an asylum claimant’s narrative must fit within the decision maker’s notions of what behavior is believable, such as displaying the ‘appropriate’ emotions at the ‘appropriate’ time during interviews (Spijkerboer, 2005). In one study, Millbank found Australian cases to repeatedly describe sexual orientation claims as ‘easy to make and impossible to disprove’—where, unlike other aspects of a claimant’s narrative (such as past persecution), disbelief regarding actual group membership will often doom the claim to failure (Millbank, 2009a). That SOGIE claims in particular are easy to ‘fabricate’ has been documented by Ferreira (2022) as well, finding a culture of disbelief around LGBT+ claims, building on the assumption that ‘pretending’ a certain sexual orientation or gender identity is easy for the claimant and a sure-fire way of obtaining protection. Consequently, asylum authorities’ assessment of the believability of a LGBT+ claimant’s identity, or whether they belong to the group they claim to belong to, is a central area for understanding the mechanisms of credibility assessment in asylum decisions.

Recently, more attention has been given to the adjudication of transgender and gender nonconforming claimants, who, despite apparent high success rates in asylum claims (Verman and Rehaag, 2024), represent a particularly vulnerable LGBT+ group due to the prominent role gender has as a sorting mechanism in most societies, putting people who do not conform to this binary at risk of discrimination and violence (Cerezo et al., 2014; Shaw and Verghese, 2022). Scholars have investigated the profound challenge of RSD in trans claims due to gender identity’s simultaneous related and distinct aspects of sexuality (Berg and Millbank, 2013; Avgeri, 2021) and given all too common outdated medical notions of what it means to be transgender. In a legal system where the golden standard of legitimate trans identity is reflected in ‘psychological and anatomical harmony’, gender affirming surgery and hormones assume a primary role (Sharpe, 2002). While the Guidelines emphasize fluidity in the assessment of trans claims, their consolidation with sexual orientation claims under a single PSG introduces ambiguity. Combined with the prevailing ‘culture of disbelief’ of LGBT+ claims, this raises critical questions about how decision makers conduct assessments of trans claims in practice.

Scholars such as Vogler (2019) have found that while the international legal system has recognized the malleability of gender through legal recognition of transgender claimants, there remains a cis-trans binary in which transgender asylum claimants must prove that they are ‘trans enough’ to be granted asylum. In other words, being transgender is understood as someone changing their gender to the ‘opposite’ one. Vogler found this narrative was established through suggestions that the claimant was “born in the wrong body” and that they desired to transition from one gender to its purported opposite though means of medical intervention.

Vogler’s findings of adjudicators’ failure to see beyond the binary speaks to broader concepts that queer theory scholars have investigated for years around the role of sex and gender in upholding social power structures. ‘Heteronormativity’ describes the insidious ways power operates in the construction of sexual categories, wherein those sexualities that fall outside of the hegemonic norms of heterosexuality—for example, homosexual, bisexual, trans, or queer—by not remaining fixed or falling outside dichotomies of sex/gender, are considered less ‘natural’ and thereby less moral. Notably, heteronormativity operates not only on an intersubjective level, but structurally, giving form to a broad range of cultural norms and societal institutions that assume heterosexuality as the norm (Ward and Schneider, 2009).

The concept of heteronormativity has been extended to describe ‘transnormativity’, or how binarism in gender identity is privileged and used as the standard against which transgender individuals are measured (Johnson, 2016). Johnson argues that transnormativity structures trans experience into a hierarchy dependent on medical and legal transition, favoring those who have taken most steps to transit from one binary category to the other. It has been well documented that the ‘psy’ disciplines (i.e., psychiatry, psychology, psychoanalysis, and psychotherapy) have often enshrined highly regulatory accounts of transgender people’s lives by emphasizing one particular account of what it means to be transgender (Riggs et al., 2019). However, as Johnson illustrates, trans experience is diverse—not all trans people wish to ‘pass’ or medically transition, or align their outward appearance with their inward identity, for that matter.

This hierarchy of legitimacy imbedded in transnormativity bears weight in the context of asylum claims as it highlights what is at stake when adjudicators must assess the credibility of a claimant’s gender identity or expression. While the Guidelines explicitly urge decision makers to avoid relying on stereotypical binary understandings in cases involving SOGIE claims, the inherently subjective nature of credibility assessments leaves ample space for human bias to influence outcomes. This is especially the case for transgender claimants, whose often-visible gender nonconformity puts them at increased risk of discrimination (Cerezo et al., 2014; Vogler, 2019; Shaw and Verghese, 2022). This often-visible gender nonconformity is consequential in an asylum context, where an experience or presentation that does not easily map onto stereotypical understandings of sexual orientation or gender identity can have a negative effect on credibility, as previously documented in other SOGIE claims (Millbank, 2009a; Jansen and Spijkerboer, 2011; Selim et al., 2023). If transnormative biases are found to negatively influence credibility assessments of trans claimants, it risks undermining the legitimacy of RSD as a fair process and unjustly returns individuals to environments where they may face persecution. Further, this could violate non-refoulment, a core principle of international asylum law, where people should not be returned to their country of origin if there is risk of persecution.

This article investigates the role of credibility assessment in transgender asylum claims in Denmark.2 Through a two-step empirical study, this article first provides a quantitative overview of how trans claims compare to other LGBT+ claims over time in the Danish asylum system. Second, through an experimental study, it analyzes the role that transnormative biases, specifically the effect of gender-affirming medical care and coming out at an early age, have on credibility assessment of trans claimants. Putting together the findings of our two-step study, we situate our results within relevant scholarly research and critically assess the compatibility of Danish practice with normative standards put forth by the UNHCR Guidelines.

Research design, methods, and findings

In the following section, we first outline our research design. Then, we provide context for Danish asylum practice. Next, we elaborate on the data and methods of our two-step analysis. In our data and methods section, we first present the methods and findings from our quantitative analysis of changes in SOGIE claims over time processed by the Appeals Board. Finally, we present our experimental study where we explore how compliance with transnormative ideals affects whether a trans claimant is perceived to be credible—or trans “enough” —to be considered by decision-makers as having legitimate protection needs.

Research design

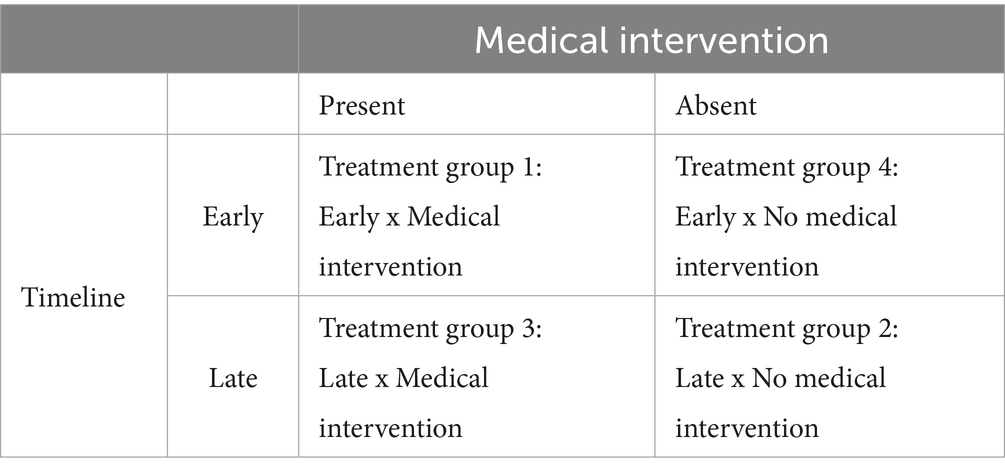

The core function that credibility assessment plays in RSD, combined with the highly intersubjective nature of the assessment, calls for further investigation into what makes a claim for asylum credible in the eyes of decision makers. To investigate this, we take a two-step approach to explore how credibility is established in cases concerning transgender claimants and how they are different to other types of SOGIE claims. In the first part, to contextualize our study of transgender claimants, we offer a statistical overview of the development in SOGIE asylum jurisprudence in Denmark between 2002 and 2021 using a dataset of case files from the Danish Refugee Appeals Board, as well as comparatively between other LGBT+ claimants (homosexuals, bisexuals, and transgender individuals). In the second part, we test two variables, the role of gender-affirming medical intervention and the timeline of a person’s coming out as trans, in an experimental study. In the study, we move beyond the legal positivist assumption of asylum decision-making resulting directly from pure legal reasoning. Rather we take a realist approach as we explore how transnormative understandings of gender as binary impacts credibility assessment. In this step, we engage with legal decision making, investigating potential underlying factors influencing credibility assessments in RSD that may not appear in the decision writing in the cases from the Appeals Board dataset. To this end, we employ students from the Faculty of Law at the University of Copenhagen as experimental participants to proxy as adjudicators in a simulated case concerning a Malaysian trans woman who fled her country of origin due to fear of discriminatory laws and harassment collectively amounting to persecution.3 Participants are randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups receiving identical information about the claimant, except for the variables tested: gender affirming medical care (hormones or no hormones), and the timeline of coming out as transgender (early or late). We compare the credibility assessments between these groups to infer the importance of adhering to transnormative ideals, and by extension, the extent to which decision makers employ stereotypes about gender as fixed and static in their assessments of SOGIE claimants’ credibility. These variables are informed by previous research on elements making up transnormative ideals, including a monolithic perception of trans people being “born in the wrong body” and a hierarchy of legitimacy that privileges medical binarism (Sharpe, 2002; Johnson, 2016; Vogler, 2019; Riggs et al., 2019).

Context: practice in Denmark

The Danish asylum system is two-tiered. When a person first arrives in Denmark and applies for asylum, the first instance to determine their protection status is at the Immigration Service. If a case follows the normal procedure, the claimant will have two, sometimes three, interviews with a case worker, who is to establish and evaluate the claimant’s identity and motivation for seeking asylum. These interviews are inquisitorial, meaning the decision maker plays an active role in helping to establish the facts of the case, and often take several hours. If a case is rejected, it is automatically appealed to the Refugee Appeals Board, who conducts another oral hearing and votes on the final outcome of the case. The Appeals Board is a quasi-judicial body consisting of a chairperson and several vice-chairpersons, who serve as judges, as well as appointees from the Danish Bar Association and a representative of Minister for Immigration and Integration.

Due to the automatic appeal upon rejection in the first instance, a significant number of cases end up going to the Appeals Board every year, where 15–20% of the decisions from Immigration Service are overturned at the Appeals level, positioning it as an integral part of the Danish asylum process and a central means to minimize the risk of refoulment (Flygtningenævnet, 2012, 2023). While the dataset we use for our analysis from the Appeals Board only contains cases that were rejected in the first instance, we maintain that despite these cases not being representative of all asylum cases in Denmark, they provide unique insights into the machinery of the Danish asylum system and how decision makers assess credibility in more complex cases.

Refugee appeals board dataset

To gauge the development of SOGIE claims for protection in Denmark over time, we draw on a large dataset of approximately 15,000 case files from the Danish Refugee Appeals Board, obtained through an agreement with the Danish Refugee Council. Working in Python and DocFetcher, we identify cases where at least part of the asylum motive is the claimant’s sexual orientation or gender identity. We identify 413 SOGIE cases adjudicated between 2002 and early 2021 and create a separate dataset with these cases. We further label the identified SOGIE cases as concerning homosexual, bisexual, and transgender claimants to scope within-group differences. Similarly, we extract the gender of the claimants, their country of origin, the year the case was finally decided, and the outcome of the case. Specifically for trans claimants, the gendered aspects of gender identity claims are complicated by decision makers’ inconsistency in their gendering of the claimants in our dataset, oftentimes referring to trans women with he/him pronouns and noting the sex assigned at birth, rather than the gender identity of the claimant. Thus, to avoid replicating the institutional harm of misgendering these claimants, we opted to exclude gender as a point of analysis for trans claimants. Because of this, we are unable to draw meaningful distinctions between trans women and trans men, excluding a potentially meaningful insight. Similarly, studies suggest there are essential differences in how gay men and lesbian women are received by decision makers in cases concerning SOGIE, however, the gendered aspects of sexual orientation claims are beyond the scope of this article (Dauvergne and Millbank, 2003; Dustin and Held, 2018).

Quantitative findings: changes in SOGIE claims over time

The majority of SOGIE claims in the dataset from the Appeals Board concern gay men (284), followed by bisexual men (68), lesbian (51), and bisexual women (15). Only 10 cases concerning transgender individuals were identified. This reflects that the vast majority asylum claimants in Denmark are men, in line with the gender distribution of asylum claims within EU countries in recent years (Eurostat, 2024). Most of the cases are from Iranian (75) and Ugandan (65) nationals, but 62 nationalities are represented amongst the 413 cases in the dataset. Meanwhile, all 10 transgender asylum claimants have different nationalities.

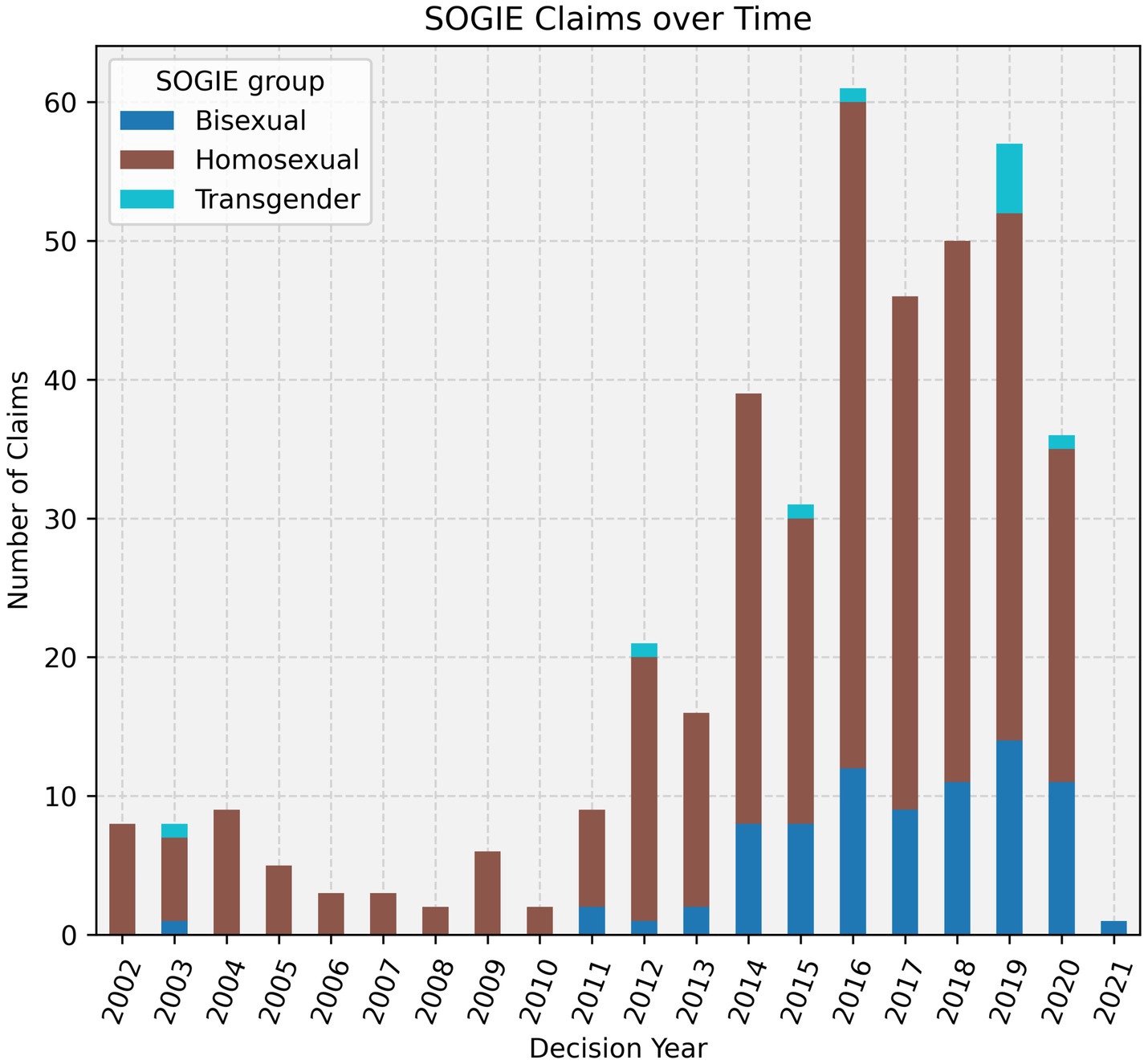

Since the earliest year in the dataset, 2002, a steep increase in SOGIE claims can be observed. While homosexuality is the most prevalent type of SOGIE claim, there has been a significant increase in claims based on bisexuality and a slight increase in transgender claims (Figure 1).

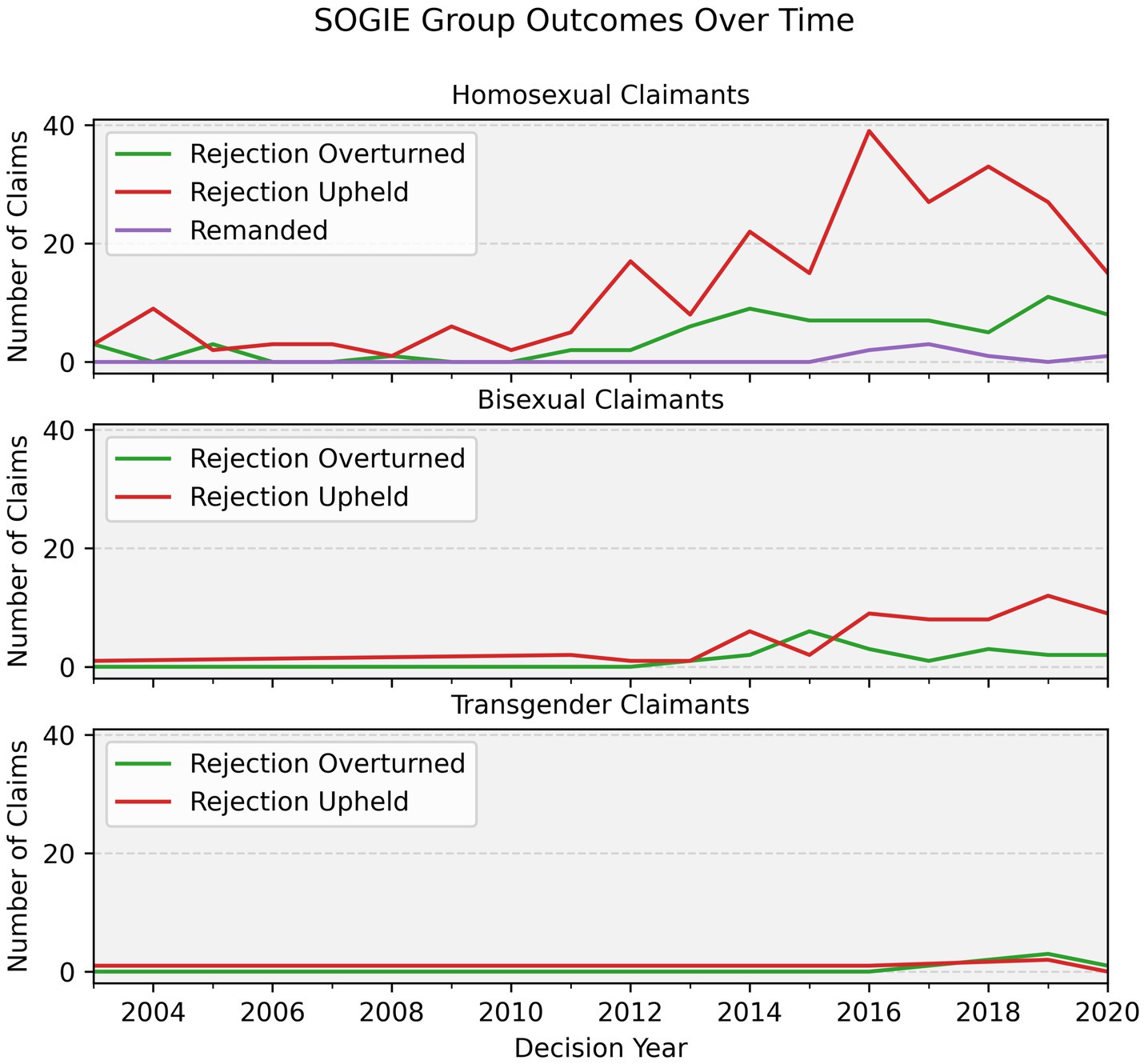

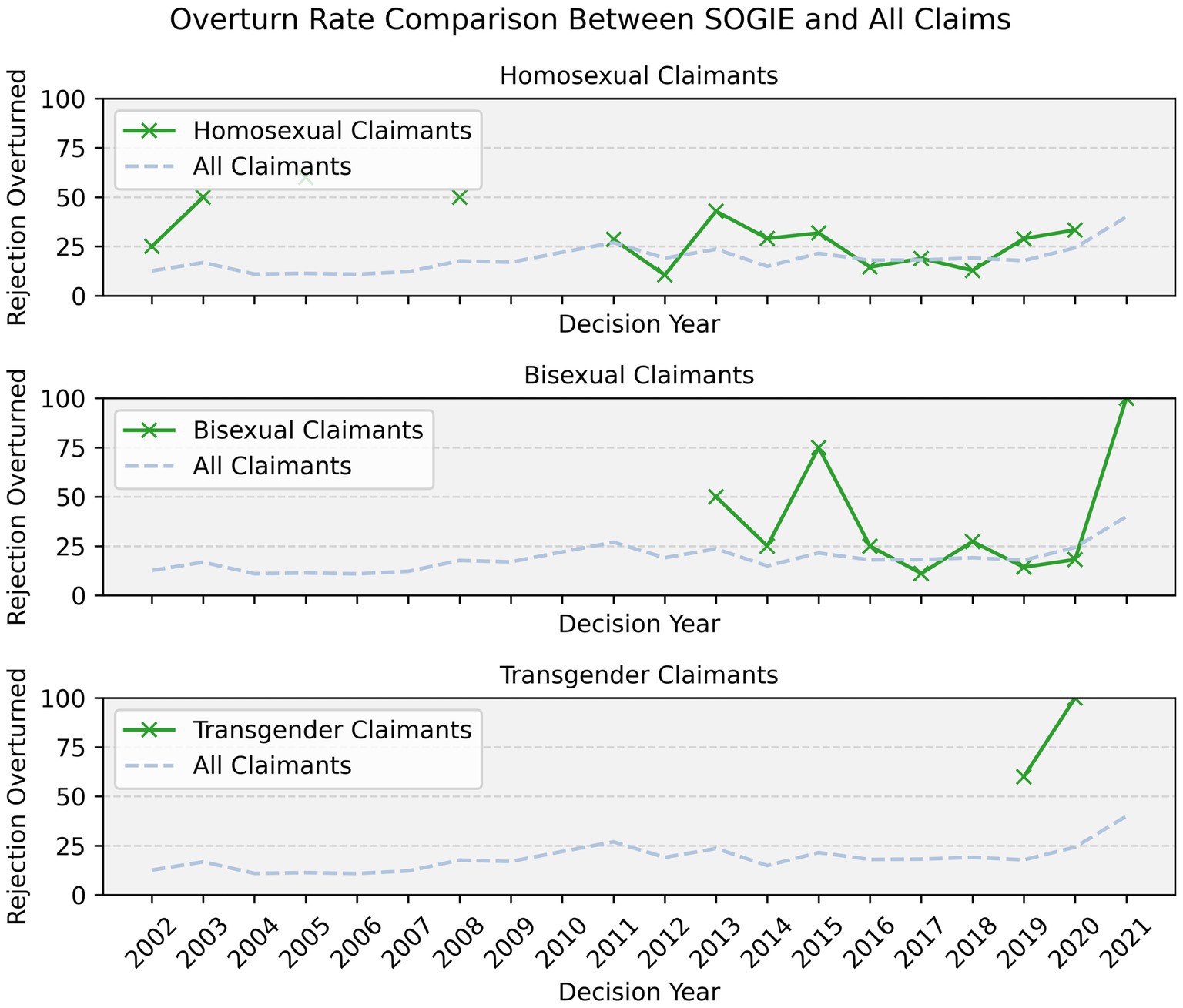

Looking to the outcomes of the cases, bisexual men were granted asylum in 28% cases (19) compared to 23% of homosexual men (64). Bisexual women were granted asylum in 20% (3) of cases and lesbians in 24% (12). In 40% (4) of cases regarding transgender claimants the initial rejection was overturned (Figure 2). Compared to the norm in other types of asylum claims (15–20%), the acceptance rates for sexual orientation claims are a little higher than the norm, while the rate for transgender individuals is double (Figure 3). The number of overall cases concerning transgender claimants is not large enough to make broader claims about the overturn rate of trans cases as compared to others, but these initial findings echo previous research on acceptance rates of transgender asylum claimants as compared to other sexual minority claimants (Verman and Rehaag, 2024).

The number of rejections in cases regarding homosexual claimants has increased (although disproportionally) along with the rising number of SOGIE claims, especially after 2015. This may reflect that more asylum claimants sought out a SOGIE motive but failed to convince the Appeals Board that their membership of the PSG was genuine. It may also reflect the Danish asylum authorities developing a more uniform approach to assessing credibility in this type of cases.

Experimental study

Experimental study design

To test the effect of transnormative ideals on the credibility assessments of trans claimants, we carry out an experiment using 249 law students from the Faculty of Law as participants. The experiment was conducted between December 2023–March 2024 and invited students to participate in a simulated assessment of an asylum case where they acted as adjudicators at the Appeals Board. The students began by reviewing a simulated case of a Malaysian asylum claimant claiming protection on grounds of fearing persecution for the reason of being transgender and as such belonging to a PSG in need of protection. Participants were informed of the evaluation that persecution of transgender individuals indeed takes place in Malaysia. While trans people face persecution and ill-treatment in many countries, Malaysia was chosen as the country of origin in the simulated case as conditions there are rarely scrutinized in politics or media in Denmark. While trans people arguably risk facing harsher criminal penalties in other countries, e.g., Nigeria and Saudi Arabia, we opted for a country of origin that is not to the same extent present in the public conversation to minimize risk of evoking feelings or associations that would compromise how well we could isolate the credibility of the claimant’s gender identity. Participants were tasked with determining whether the claimant’s testimony about their gender identity was credible, or if it was constructed for the occasion as found by the Immigration Service. Participants were provided with excerpts of the claimant’s case file, including facts of the case, the interview summary from the interviews with the Immigration Service and the Appeals Board, as well as the reasoning for the negative decision from the Immigration Service. The rejection by the Immigration Service was reasoned with a lack of credibility, i.e., the case worker did not believe that the claimant was transgender (or at least not transgender enough). In other words, had the claimant established that they were, in fact, transgender or were they lying?

Participants were told they were participating in a survey but did not know they were being exposed to different treatments to allow for unobtrusive measurement of their behavior. We added attention and manipulation checks to ensure participants understood the case, including the manipulated variables. At the start of the experiment, participants gave their consent and were given the opportunity to withdraw upon completion. Participants received debriefing on the purpose of the study.

The choice to have students act as decision makers at the Appeals level in an experimental study is motivated by three considerations: First, it allows us to ground the simulated case in the actual decision writing of adjudicators in that we could base the simulated case on real cases from the Appeals Board dataset. Second, while there are apparent differences between students’ and professional decision makers’ knowledge and experience with asylum adjudication, it has been found that both groups are equally prone to let their decisions be influenced by stereotypes when detecting deception (Granhag et al., 2005). In fact, despite no difference between the groups in detecting deceit, studies indicate that professional decision makers tend to be over-confident in their ability to assess deceptiveness (DePaulo and Pfeifer, 1986; Kassin et al., 2005). Similarly, a notable difference is that participants in our study were asked to judge credibility based on written material only, whereas professional decision makers spend hours with a person face to face. This may, in an RSD setting, render the consequences of wrongfully rejecting a claimant more startling, affecting the practical application of the benefit of the doubt principle. Despite these apparent differences between the population we study and the population of interest, we prioritize the ability to isolate our treatments as well as the accessibility and willingness of students to participate. And third, conducting an experimental study allows for an isolation of credibility where the question at hand is only regarding the credibility of the claimant’s trans identity. In other words, the risk towards transgender individuals living in Malaysia is established, and the only remaining question participants must assess is whether the claimant is believed to be part of this PSG. Being able to isolate the question of credibility at the level of affiliation with the identified PSG, in this case transgender individuals in Malaysia, minimizes the chance of participants being influenced by their perception of the conditions in the claimant’s country of origin or of what constitutes persecution.

We operationalize transnormative understandings of gender into two binary variables: the presence or absence of gender affirming medical care (hormones or no hormones), and whether the claimant came out as trans in childhood or six months prior to leaving Malaysia (early or late timeline). To examine the effect of our variables on credibility assessment, we employed a two-by-two factorial design, where each variable was tested in combination (Table 1). This enabled us to identify both the isolated and the interaction effects of the two treatments on perceived credibility. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four treatment groups.

The effect of the tested variables on credibility was measured across three outcome variables.4 To this end we asked participants to evaluate the following:

1. How likely is the claimant to face persecution if returned to their country of origin?

a) Likert scale from 1 (very unlikely) to 5 (very likely)

2. Do you support the evaluation of the Immigration Service that found the narrative was constructed for the occasion?

b) Binary, yes/no

3. And finally, would you vote to grant the claimant refugee status?

c) Binary, yes/no

The first question was analyzed using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. The two binary outcomes were analyzed using logistic regression and odds ratios. Participants were additionally given the option of providing written reasoning for their assessments. At the start of the experiment, participants were asked to provide demographic information, allowing us to measure how the background characteristics of participants may influence how credibility is evaluated. We collected participants’ self-reported gender, sexual orientation, as well as their personal experience or familiarity with the Danish asylum and migration system to explore potential heterogeneous effects of the participants’ identity with their credibility assessments.

Mathematically, our analysis can be expressed as:

1. How likely is the claimant to face persecution if returned? (Likert scale):

2. Do you support the evaluation of the Immigration Service that found the narrative was constructed for the occasion? (Binary yes/no)

3. Would you vote to grant the claimant refugee status? (Binary, yes/no)

Participant overview

The experiment had a total of 249 participants after filtering out participants who did not pass the attention and manipulation checks (n = 60). Of those, 238 answered demographic questions. Using random assignment, each treatment group saw an even distribution of participants, with the 238 total distributed across treatment groups 1 (n = 56), 2 (n = 64), 3 (n = 65), and 4 (n = 64).

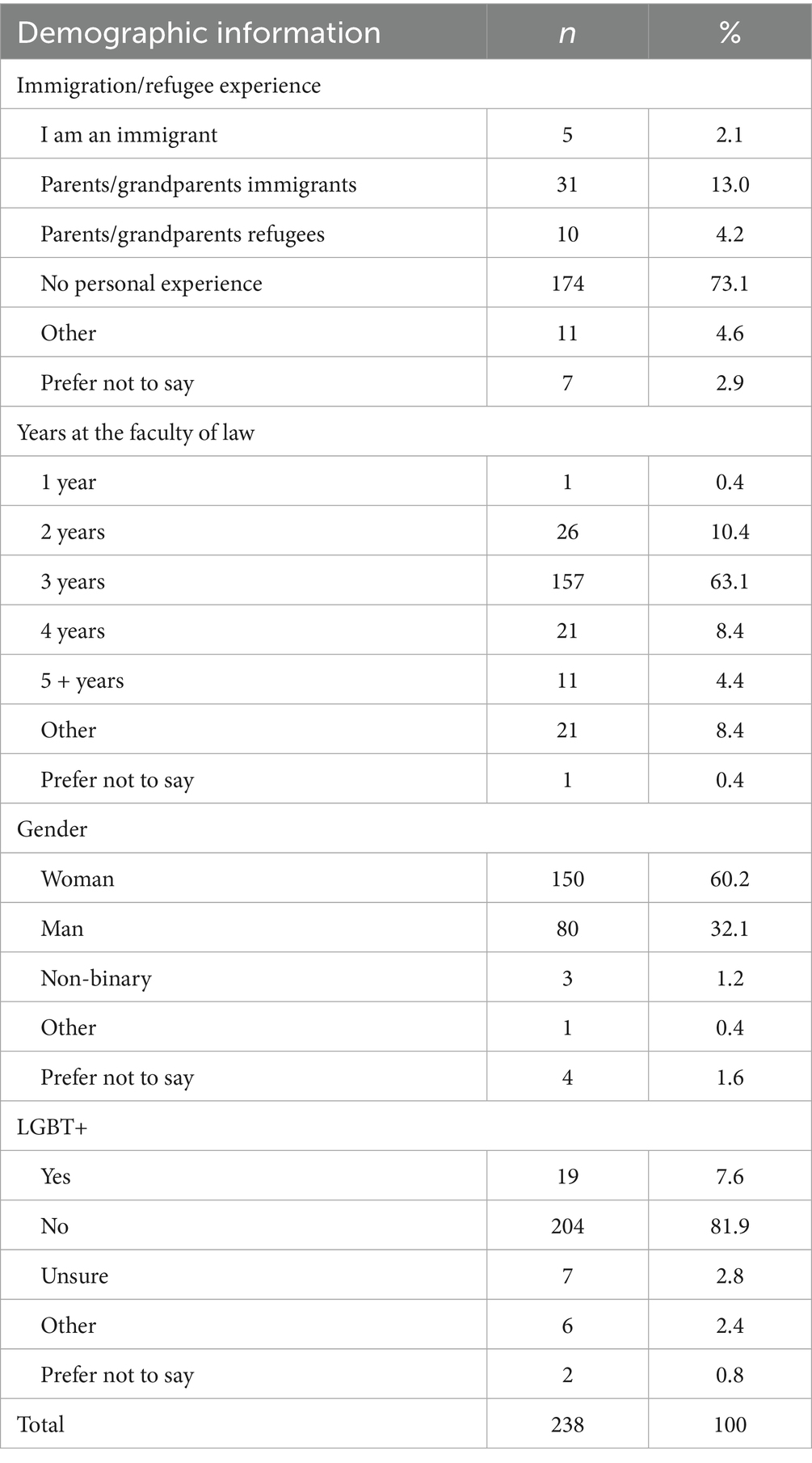

As illustrated in Table 2, most participants were women (60.2%), third year law students at the Faculty of Law (63.1%), did not identify as LGBT+ (81.9%), and were not themselves immigrants or refugees (73.1%). Roughly a third of participants were men (32.1%), while only three participants were non-binary (1.2%). A considerable number of participants had parents or grandparents with immigrant (13.0%) or refugee backgrounds (4.2%), while fewer were immigrants or refugees themselves (2.1%). While an argument could be made for grouping participants with personal experience and parents or grandparents who have experience with the immigration system in Denmark together, we ultimately decided to maintain them as separate groups as to avoid conflating personal experience with secondhand experience. This demographic measure was furthermore excluded from our analysis as the number of participants with personal experience was too low to yield meaningful results.

Experimental findings

In the following section we present the results of the experimental study which tested the effects of gender-affirming medical intervention and the timeline of coming out as transgender on claimants’ credibility. We present our results by each of the three credibility assessment questions we asked participants to evaluate, also known as our outcome variables. For each outcome variable, we summarize the results of the credibility assessments by treatment group and summarize the main and interaction effects of the treatments. Lastly, we account for the effects of participants’ background characteristics and the credibility assessment results.

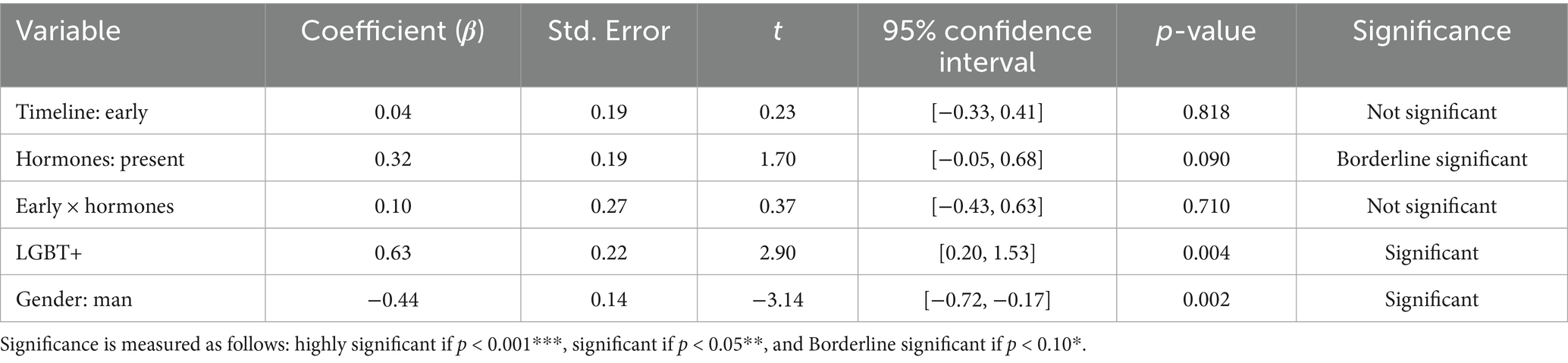

Likelihood of persecution

The first question we asked participants to evaluate in our study was the likelihood that the claimant would face persecution if returned to their country of origin. This first outcome variable measuring credibility aimed to capture participants’ assessment of the claimant’s subjective fear. For this outcome variable, only medical intervention had a borderline significant effect on the perceived likelihood of the claimant facing persecution if returned to Malaysia. In other words, those who evaluated a case where the claimant received gender-affirming medical care were 32% more likely to find that the claimant would be facing a risk of persecution compared to those who assessed a case where the claimant did not receive hormones (See Table 3 and Figure 4).

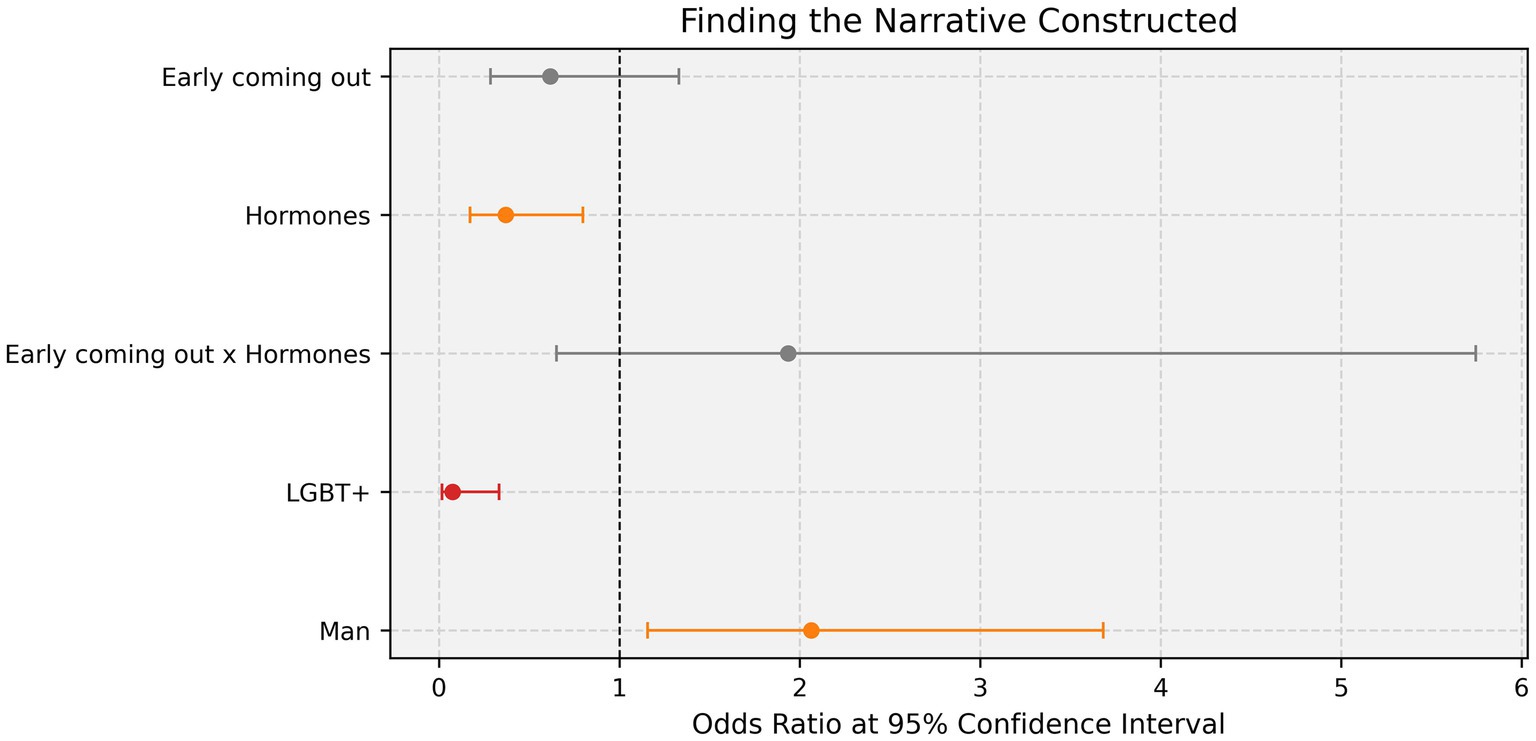

Figure 4. OLS estimates of the experimental effects on perceived persecution if returned to country of origin (95% CI). Level of significance of result are indicated by colors where red indicates highly significant, orange indicates significant, blue indicates borderline significant, and grey indicates not significant.

In our analysis of the interaction between the timeline of coming out and gender-affirming medical intervention, we saw results indicating that in some instances when the claimant had an early coming out and reported taking hormone pills, participants were more likely to find the claimant credible. Although these results were positive, they were only borderline significant. This points to the complexity of the interaction, where combining an early coming out with medical intervention does not always yield additive positive effects—some participants may question the credibility or need for protection in such cases. The borderline significant results suggest that a larger sample may yield significant results.

Looking to the demographic information, we observe that amongst our participants in all treatment groups, men were 44% less likely than other participants to deem the claimant at risk of persecution. Meanwhile, LGBT+ participants were 63% more likely to find that the claimant would be at risk of facing persecution if returned (Table 3). Both background characteristics had highly significant effects (Figure 4). If these results extend beyond this experimental study, it suggests that the gender and sexual orientation of a decision maker may have an effect on their perception of trans claimants’ likelihood of persecution (see Table 3 and Figure 4).

Narrative constructed for the occasion

To measure how participants evaluated the claimant’s credibility, we asked whether they supported the conclusion by the Immigration Service that the story was constructed for the occasion, and thus not credible. This was our second outcome variable measuring credibility, aimed at capturing whether participants thought the claimant’s narrative was true or not.

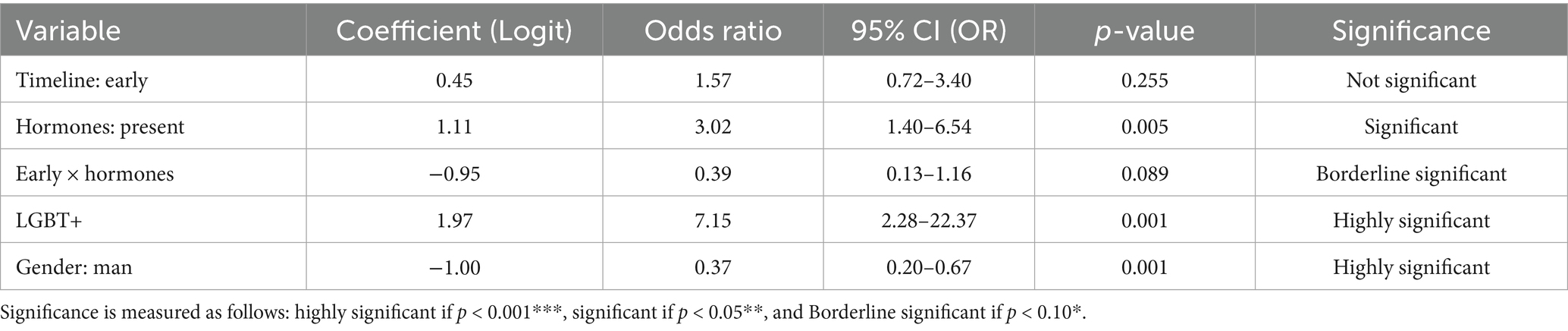

Here, results indicate that the presence of gender-affirming medical care had a statistically significant impact on participants’ assessment of the claimant’s narrative being constructed for the occasion (Table 4 and Figure 5). Participants who received information that the claimant had taken hormonal supplements were 63% less likely to support the first instance’s negative credibility findings (Table 4). The effect of this treatment is significant, meaning we can confidently conclude this is not due to chance (Table 4 and Figure 5). This is in line with the transnormative hierarchy of legitimacy described by Johnson (2016), where medical markers of gender transition ‘legitimate’ the transition from one binary category to another. As one participant elaborated: “The story seems very structured for the whole asylum process. Considering the applicant is not sure [whether] they want hormones and to undergo surgery.”5 Another student argued that the lack of hormonal treatment or other “non-reversable treatments” made the story less credible.6

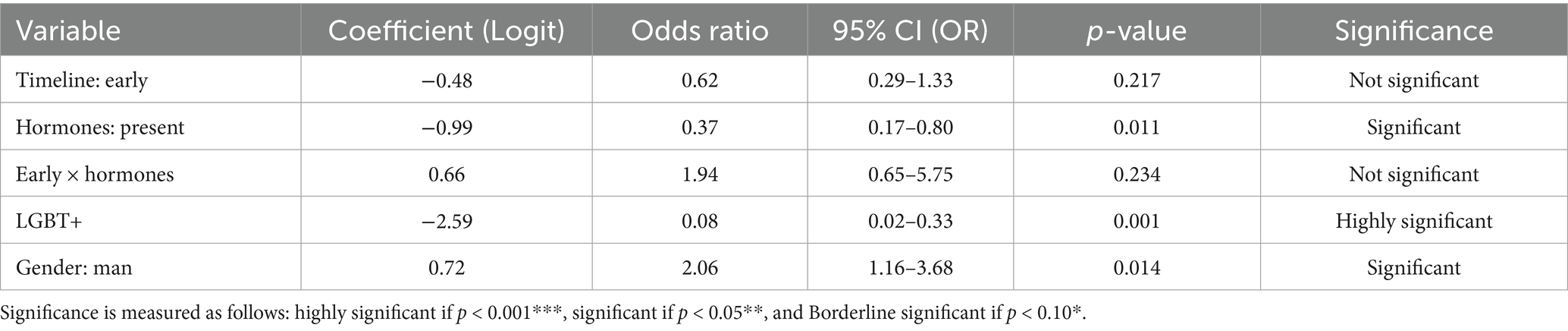

Table 4. Logistic regression and odds ratio results: supporting immigration service finding narrative constructed.

Figure 5. Estimated odds ratios for supporting immigration service finding narrative constructed: experimental and demographic effects (95% CI). Level of significance of result are indicated by colors where red indicates highly significant, orange indicates significant, blue indicates borderline significant, and grey indicates not significant.

Looking at the timeline of coming out, we observe that an earlier coming out has an effect on participants’ credibility assessment of the claimant. Our results indicate that participants exposed to the early coming out treatment, where the claimant identified as trans since childhood, were less likely to support the Immigration Services’ negative credibility finding than those exposed to a treatment where the claimant had only realized six months prior to leaving Malaysia (Figure 5). Specifically, support for the negative credibility finding was estimated to be about 48% lower in the early coming out timeline group (see Table 4 and Figure 5). However, this difference is not statistically significant, meaning we cannot confidently say that this effect is real rather than due to chance (Figure 5). Still, participants’ written explanations suggest that the timing of coming out mattered to some. As one participant put it: “I believed the applicant’s story until they mentioned that it was only six months before that they knew they were transgender. That seems unlikely, [because] what [I] have heard of is that transgender people usually have a feeling that something is different about them from a [y]oung age.”7 In this example, the participant’s logic is in line with the transnormative hierarchy of legitimacy, privileging those who have known from an early age that they were ‘born in the wrong body’ and questioning the authenticity of those that deviate from normative transition timelines (Johnson, 2016).

We further looked at whether the interaction effect of the claimant’s early coming out changed when paired with the presence of medical intervention. Although the effect of this interaction was positive with an estimated coefficient of 0.66, it was not statistically significant, meaning we cannot draw conclusions about whether the interaction meaningfully influenced credibility assessments (Table 4). However, participants’ reasonings provide insights. Participants exposed to a later timeline of coming out combined with the presence of medical intervention tended to focus less on the timeline and more on the visibility of the claimant’s gender identity and the derived risk of persecution from being visibly trans.8

Turning to effects of the participants’ background characteristics, we once again found that their identity influenced their assessment. Men were twice as likely to support the negative credibility finding (see Table 4 and Figure 5). Most significantly however, participants who themselves identified as LGBT+ were 92% less likely to support a negative credibility finding (Table 4). This effect is highly significant, suggesting substantial differences in assessment patterns based on the participant’s own identity (Figure 5).

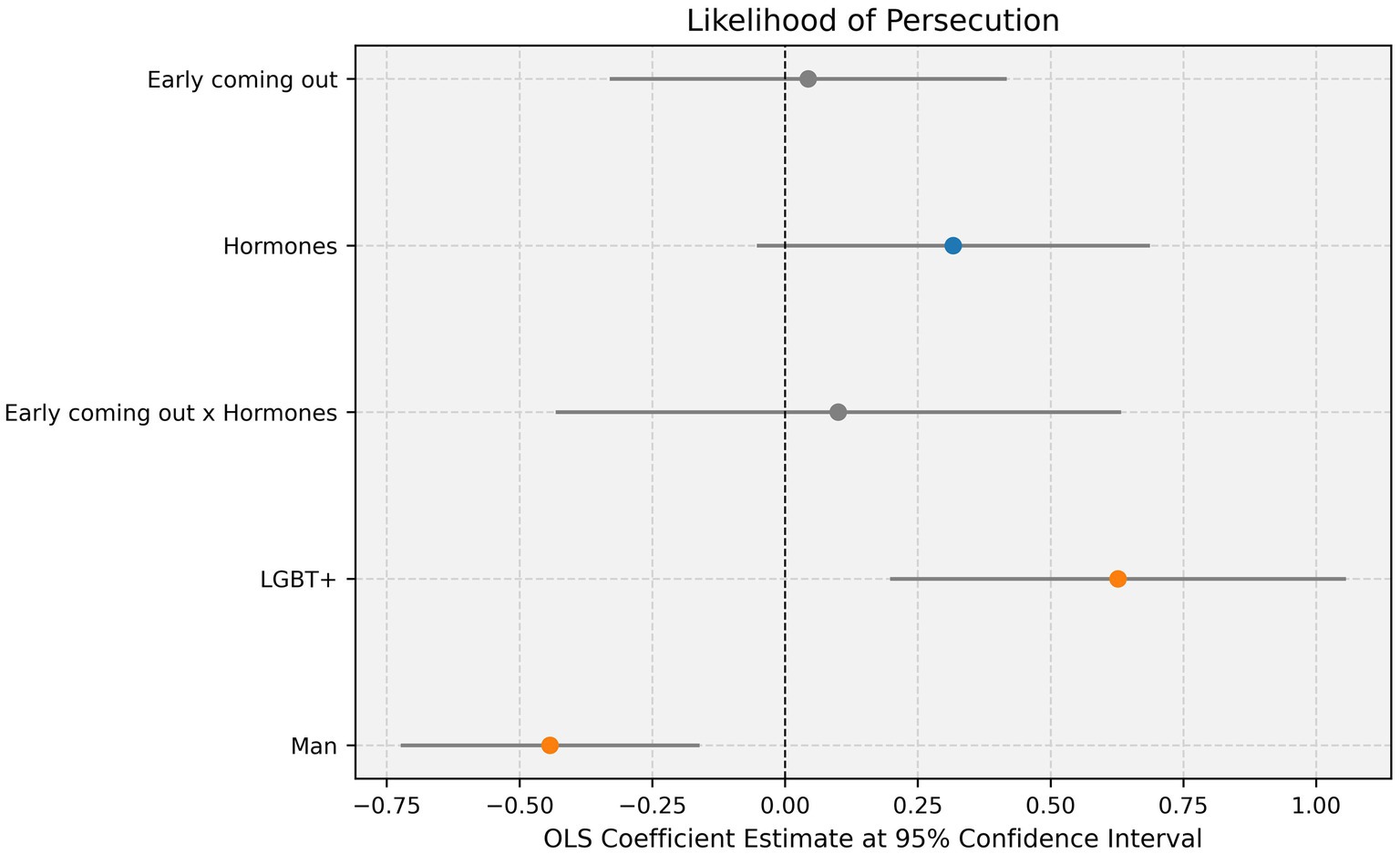

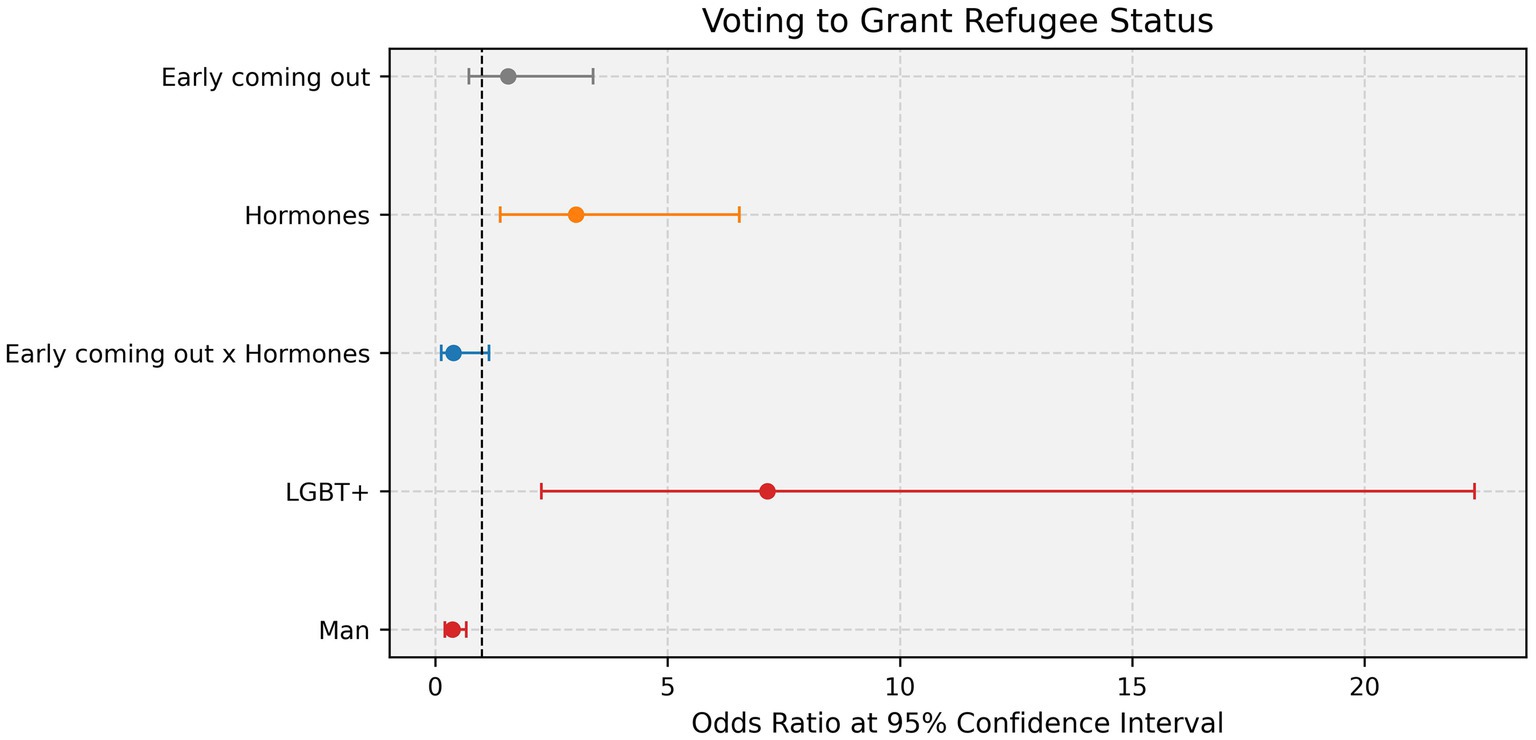

Voting to grant asylum

The final question we asked participants to evaluate was whether they would vote to grant the claimant refugee status. This last outcome variable was designed to delineate potential differences between the credibility assessment and the decision to grant refugee status, as assessing credibility and granting asylum are intrinsically related, but not always straightforwardly. The analysis reveals a significant positive effect of gender-affirming medical intervention. Participants were more than three times as likely to vote to grant asylum to a claimant if they were in a treatment group where the claimant had reported taking hormone pills. This result was significant (see Table 5), meaning there is a high level of confidence that this effect is not due to chance. As with the previous outcome variables, we see that the early coming out timeline has a positive, but insignificant effect on the outcome. In other words, there is no clear evidence that the timeline has affected the credibility assessment.

While we assumed that claimants who reported taking hormone supplements and having known of their trans identity from an early age would be placed higher in the transnormative hierarchy of legitimacy, we observe the opposite. From our experiment we see a negative effect of the interaction of these two treatments, indicating that participants who read cases of a trans claimant with an early timeline and who had also taken hormones were 61% less likely to vote in favor of granting asylum, compared to if they had read a case with a later timeline and an absence of any gender-affirming medical care (Table 5). Although these findings are borderline significant, their surprising effect calls for further investigation.

Our analysis shows that the identity of the participant has a highly significant effect on whether they would vote to grant the claimant refugee status or not (Figure 6). LGBT+ participants were seven times more likely than their non-LGBT+ counterparts to grant refugee status, while men were less than half as likely as women and non-binary participants to grant refugee status. Both were highly significant (Table 5).

Figure 6. Estimated odds ratios for voting to grant the claimant refugee status: experimental and demographic effects (95% CI). Level of significance of result are indicated by colors where red indicates highly significant, orange indicates significant, blue indicates borderline significant, and grey indicates not significant.

Next, we turn to our discussion section where we further analyze potential mechanisms underlying our findings, contextualize our results in relevant scholarship on RSD, and critically reflect on the consequences of our findings on Denmark’s compliance with international guidelines.

Discussion

Emphasizing the ‘T’ in trans

The large role that credibility plays in the assessment of SOGIE asylum claims has been researched widely by refugee scholars (Millbank, 2009b; Jansen and Spijkerboer, 2011; Rehaag and Cameron, 2020; Zisakou, 2021). Our findings echo previous research indicating that credibility is especially important for LGBT+ claimants and adds to the scholarship by analyzing how credibility of transgender claimants is approached by decision makers.

Our finding that the overall number of SOGIE claims in the Danish caseload has increased substantially over time and especially after 2015 is unsurprising, but nevertheless a valuable contribution to a field that has little historical data available on asylum claims made on the basis of being LGBT+. Additionally, finding that at the Appeals level, SOGIE cases have a considerably higher overturn rate (20–40%) than the overall case load (15–20%) points to a potential disjuncture between the first and second instance, where credibility may be the underlying explanation. This could in part be due to the 2012 practice change following the CJEU decision in X, Y and Z, abolishing the so-called ‘discretion requirement’ of concealment for LGBT+ claimants.9 Prior to this ruling, decision makers could return LGBT+ claimants to their country of origin on the basis that they could conceal their sexual orientation or gender identity, thus avoiding persecution. Whereas previously, risk of persecution was emphasized in LGBT+ claims, scholars have found that, in practice, the end of the so-called discretion requirement has led to credibility playing a larger role (Jansen, 2018). Another explanation for the relatively high overturn rate could be the 2012 publication of the UNHCR Guidelines no. 9 leading to increased attention on how SOGIE cases are assessed. This, combined with the overall increasing number of claims made on the basis of SOGIE could explain the high number of claims making it to the Appeals level. Given the automatic appeal mechanism in Danish practice, the high overturn rate of SOGIE claimants could also be understood as an intentional ‘function’ of the second instance, where it is anticipated that a considerable number of cases will be overturned. Even so, it does not explain the discrepancy in overturn rates between SOGIE cases and the general caseload.

Out of the 413 identified cases concerning SOGIE, only 10 are made by transgender claimants. Since the first documented case in 2002, it is apparent that the Board has improved their practice around gender identity claims in recent years. Over time, the reference to claimants using the correct pronouns, and generally a greater understanding of the nuances of gender identity were clear and hopeful. For example, more of the earlier cases use the term ‘transexual’ (‘transseksuel’), while recent cases tend to use the term ‘transgender’ (‘transkønnet’).10 It also appears from the dataset that pronouns are often used inconsistently, and especially many of the earlier cases use the pronouns associated with the claimant’s sex assigned at birth, as opposed to the pronouns associated with their gender identity. Notably, there were no identifiable cases concerning non-binary claimants in the dataset. Due to changes in the Appeal’s Board’s practice and self-documentation, it is not unlikely that there are more cases of transgender and gender non-conforming claimants that have made it to the Danish Appeals Board but that remain uncaptured by the dataset. These may be cases that are registered as ‘homosexual’ or ‘bisexual’, or which are not registered as a case concerning SOGIE at all.

The homogenization of the SOGIE category has been critiqued by scholars and claimants alike for flattening the experience of LGBT+ individuals, assuming the experiences of gay men apply to a wider and diverse group of individuals claiming asylum based on SOGIE (Danisi et al., 2021). Our analysis of the Appeals Board dataset, which found a wide range of overturn rates for the ‘umbrella’ of sexual orientation and gender identity claims (20–40%), offers a quantitative exposition of the variety of experiences of LGBT+ asylum claims. Consider that 40% (4/10) of claims by transgender individuals were overturned at the Appeals level, while only 20% (3/15) of claims by bisexual women were overturned. Without access to cases that were granted asylum or found manifestly unfounded before reaching the Appeals level, it is impossible to explain the differences in overturn rates. Albeit limits to generalizability considering the relatively low number of LGBT+ cases in the Appeals Board dataset, these differences in overturn rates are nonetheless informative of differential trends over time and provide insight into the machinery of the Appeals level decision-making. This reflects the need for further research on the heterogeneous experiences and challenges of LGBT+ asylum claimants.

While working exclusively with Appeals cases compromises the extent to which findings can be generalized beyond the Appeals level, the dataset represents an archive of cases that are especially important for understanding the mechanisms underlying decision making as they have faced several layers of assessment by authorities. Consequently, despite these cases not being representative of all asylum cases in Denmark, they provide insight into the cases that were not found obviously credible or not credible, which is the focus of this research.

Working with the case files from the Appeals Board, it is critical to understand the dataset as an archive recognizing that any archive is fundamentally a matter of selection and discrimination (Mbembe, 2002). While being ‘counted’ is not necessarily an unconditional good—sometimes being made more visible to a system of domination makes someone more vulnerable—being counted can be the first step in making systemic issues visible (D’Ignazio and Klein, 2020). Given that many issues of structural inequality are problems of scale, they can seem anecdotal until they are viewed as a whole. Thus, the act of counting also uncovers issues in the classification system itself, prompting further problematization of how SOGIE asylum claims are processed and categorized. The structure and labeling of the dataset from the Appeals Board presented several barriers to nuancing our analysis of transgender asylum claims. We were unable to draw meaningful distinctions between trans men and trans women and the outcomes of their cases. Similarly, we were unable to account for additional factors such as race, religion, cultural context, and age, both due to the structure of the dataset, but also due to the ethical risk of making individual claimants identifiable. By using binary variables to empirically measure the effects of transnormativity, our study inherently uses categorical divisions that oversimplify the complexities of trans and gender non-conforming claimants’ experiences and identities. Weighing the costs and benefits, we find that although we are unable to account for how transnormativity intersects with gendered and racialized experiences of transgender asylum claimants, our methods allow for a critical contribution to a research field lacking in empirical studies. Thus, our findings speak to the pressing question of how asylum law ought to contend with gender identity claims made on the basis of PSG, a complex question that lies beyond the scope of this study, but which nevertheless should be high on the agenda of further research on credibility in asylum law concerning gender identity and expression.

Medicalization legitimizes trans experiences

Previous research has documented how medical and legal institutions uphold transnormativity, facilitating a binary classification of gender identity (Johnson, 2016; Riggs et al., 2019). Little research, however, has documented the role of transnormativity in an asylum context, where access to medical and legal gender recognition may be limited, and where the stakes of misrecognition are exponentially high. Findings from our experimental study reveal several noteworthy patterns regarding factors shaping the perceived credibility of transgender asylum claimants. First, the timeline of coming out as trans did not appear to significantly influence the participants’ assessment across any of the three outcome measures. In contrast, the presence of gender affirming medical care, here exemplified with hormones, significantly increased the perceived risk or likelihood of persecution, credibility, and likelihood of being granted asylum. This effect may suggest that steps taken towards fitting a transnormative ideal influences how decision makers perceive an “authentically” trans claimant, or it may serve as a proxy for risk perception.

Operationalizing complex phenomena such as transnormative understandings of trans experience into categorical variables is inherently flawed. While nuance may be lost in the process of necessarily watering down such phenomena into categorical variables to conduct the experiment, our operationalization is informed by previous scholarship on transnormativity. There are also intrinsic limitations to the portability of experimental results to real RSD practices, which do not exist in an experimental setting where variables are isolated. We account for this limitation in generalizability by weighing the costs and benefits of experimental research, finding that the opportunity to isolate variables provides much needed empirically grounded knowledge in the field of bias in decision-making around transgender asylum claimants.

The implications of these findings are manifold. Not only are potential issues of access to medical transition critical in an asylum context, but our finding that medical intervention has a significant positive effect on trans claimants’ credibility risks reducing the diversity of trans experience into one homogenous model compliant with transnormative hierarchies. In their written responses, participants exposed to the treatment groups with no medical intervention reacted to the perceived ‘impermanency’ of a transition not mediated by medical intervention. As one participant in our study put it, “There is no evidence, and it does not seem like the applicant is serious about taking hormones—it would be ‘too easy’ to get asylum if you could claim that you wear women’s clothes at home.”11 Not only does this response reflect the disproportionate weight that medical intervention in transitioning carries on trans claimants’ credibility, it also speaks directly to the idea that SOGIE claims are easy to fabricate (Ferreira, 2022). Here, the participant’s response insinuates that had the claimant undergone medical transition through taking hormones or gender-affirming surgeries, this could have counteracted the inherent issue with transgender claims otherwise being “too easy” to fabricate, by facilitating a more permanent physical alteration to prove their claim. While the culture of disbelief around trans claimants may function differently than for other queer claimants, lay assumptions about what makes someone “authentically” trans echo prior research on sexual orientation claims in that trans claimants must be considered trans “enough” by decision makers to be deemed credible.

If findings from our experimental study are generalizable to Appeals Board decision makers, it is not unlikely that asylum authorities have similar biases imbedded in their decision-making. This is especially significant considering the framework of claiming protection under the Convention. For claimants to fulfill the requirements of belonging to a PSG, they must convince decision makers that they share a common characteristic with a group that is “innate, unchangeable, or which is otherwise fundamental to identity, conscience or the exercise of one’s human rights” (UNHCR, 2002). As observed by other asylum law scholars, this requirement can be at odds with the fluidity and complexity of gender identity and expression, and of the lived experiences of LGBT+ people (Dustin and Held, 2018; Ballin, 2023). This requirement of immutability raises the question of how transnormative understandings of gender in asylum adjudication not only privileges experiences that conform to medical-legal norms, but also how the system in turn may perpetuate and re-create transnormative conformity. Given that fear of persecution is a requirement for fulfilling Convention status protection, this requirement presents a difficult situation for trans claimants when it comes to establishing their credibility. On the one hand, it may be difficult to get access to hormones or gender-affirming surgeries which could in theory ‘increase’ their credibility as being transgender. And on the other hand, even if trans claimants can access hormones or gender-affirming surgeries, will this be perceived by migration authorities as proof of not fearing persecution in their country of origin?

Effects of background characteristics on decision-making

The influence of participants’ background characteristics on their credibility assessments remained consistent throughout the three parts of the experiment. Regardless of the experimental treatment conditions, the gender and LGBT+ identification of participants had a consistent significant effect on their responses. Men and non-LGBT+ participants were significantly less supportive, both in assessing credibility and in voting to refugee status. The finding that men were less likely to find the claimant credible contributes to the academic debate on the effects of gender on attitudes towards refugees. While one large-scaled study found no effect of the gender of the judge deciding an asylum case (Rehaag, 2011), our findings echo previous research showing that being a man, among other demographic measures, correlates with less favorable attitudes towards refugees (Anderson and Ferguson, 2018; Cowling et al., 2019).

The finding that participants’ gender and LGBT+ status had an influence on their credibility assessment measures could be explained by women and LGBT+ participants’ identification with the claimant, an interpretation in line with previous research on similarity effects and shared identity (Hellmann et al., 2021). Given that other measures such as political affiliation and education level have also been found to correlate with certain attitudes towards refugees (Anderson and Ferguson, 2018; Gregurović et al., 2016), it may be that LGBT+ status and gender similarly correlate with certain attitudes towards asylum claimants more broadly, regardless of personal identification or not. However, other studies have found little variation across age, education, and political ideology (Bansak et al., 2016), indicating empirical support both for and against this interpretation.

While our sample population is limited in size and diversity, this is a limitation that reflects a larger challenge to external validity in social science research. Many experiments rely on students from ‘WEIRD’ (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) contexts, which consequently is one of the least representative demographics globally. Despite the homogeneity of our sample, the target population is decision makers at the Appeals Board, who mostly mirror the WEIRD attributes of our participants, besides expected generational differences. Thus, this homogeneity works in favor of our study’s sample population being representative of the decision makers at the Danish Appeals Board. The external validity of our results further rests on the assumption that testimonial cues, like non-verbal cues (Granhag et al., 2005), influence both students and decision makers.

Although there remains key differences between law students and professional decision makers, such as their degree of legal knowledge, sense of adjudicative authority, and understanding of the real-world consequences of their decisions, we argue that the findings from our experiment still have wider applicability to RSD considering the systematic nature of biases, which often are deeply embedded in our cultural and societal fabric. The differences in experience and knowledge of the specificities of asylum law between the two groups may have been a greater cause for concern had the participants been asked to evaluate the persecutory threshold or existence of risk, which may have required more advanced legal knowledge, rather than the authenticity of someone’s gender identity. Nevertheless, considering the sensitivity of assessing the authenticity of someone’s gender identity, we recognize that the isolated nature of an experimental design cannot possibility replicate the ethical stakes of real-world decision making, nor the institutional power it is embedded in.

Looking forward: effective remedy and accounting for bias in decision-making

Despite Guidelines from international governing bodies discouraging otherwise, (UNHCR, 2012, 2013) stereotypes appear to have a significant effect on the credibility assessments of trans claimants. While the Guidelines on how to apply the Refugee Convention are not binding for signatory states to the Convention, they are often cited in core legal literature as an additional legal source [see, e.g., Zimmermann et al. (2024)]. Further, the extent to which SOGIE claims are treated in accordance with UNHCR Guidelines is an indication of the significance of soft law instruments on adjudicator practice, and what happens when they conflict with culturally informed perceptions of human identities.

Our findings echo other studies pointing to issues of bias in a legal field where much is left to individual discretion and empirically support the scholarly criticism that credibility assessment in RSD is both highly subjective and may to a notable extent be influenced by transnormative perceptions. Results from our analysis suggest that decision makers rely on stereotypes about what is means to be transgender, privileging an alignment with the gender binary. The favoring of this alignment is neither consistent with how the UNHCR Guidelines recommends considering medical intervention when establishing credibility of trans claimants, nor is it aligned with how the Guidelines emphasize the fluid nature of SOGIE claimants generally. If these biases negatively influence credibility assessments in actual RSD practices, the stakes are high. Not only do decision makers risk violating the core principle of non-refoulment, but claimants risk suffering the ultimate consequences if they have their case heard by the wrong adjudicator. While training modules for decision makers on bias minimization (e.g., Council of Europe, 2023) and more evidence-based interviewing techniques (EUAA, 2022; Skrifvars et al., 2025) may decrease the effects of biases that are cognizable to decision makers, institutional safeguards must accompany these efforts to protect refugees from wrongful rejections based on biases and assumptions that remain obscured from decision makers themselves and which are a result of a more systemic problem. Specifically, the role of appeal instances and increasing their review of decisions hinging on questions of facts is central.

Considering that several studies, including the present study, have shown that credibility is both a central element for outcomes in SOGIE cases and is highly dependent on the discretion of the decision maker assigned to the case, we recommend that decision makers, when rejecting a claim based on disbelief of a claimed identity, be required to extensively argue their negative credibility findings with references to relevant guidelines (e.g., UNHCR’s Guidelines no. 9). This would have two clear effects: First, formalizing this requirement would increase accountability for decision makers to actively engage with bias training and their collective and individual practice. Second, requiring elaborate reasoning for negative credibility findings would provide asylum claimants and their legal representation with specific points of reference to challenge when preparing an appeal or requesting reopening of a case. Although it may be nearly impossible to account for the insidious mechanisms through which transnormativity, or other biases for that matter, inform decision-making, requiring decision makers to provide thorough reasoning for their negative credibility findings would create clearer pathways towards justified remedies. Review of facts is central to all claims for asylum where credibility is a theme, but for those where belief in their identity is at the crux of the decision, interrogating how findings of disbelief are reached at all levels of decision making is central to ensure no refugee is refouled based on biased assumptions.

Contribution of the research

Research on transgender individuals within refugee scholarship is unfortunately scarce, even within LGBT+ research on asylum. Our research contributes to the current research gap on this important population. Beyond contributing to research on LGBT+ asylum claimants, our findings also have valuable insights to the broader scholarship on bias and stereotyping in refugee status determination, finding that the background characteristics of decision makers may influence their credibility assessments. Additionally, our mixed methods study provides an important methodological contribution to scholarship on asylum law by using empirical methods that allow for causational measurement of otherwise difficult-to-measure phenomena, like the influence of stereotypes and biases on decision-making.

Our results point to several directions for future research on the credibility of transgender asylum claimants. In our study, we tested the effect of two variables on credibility assessments, but due to the entanglement of assumptions embedded in transnormativity, future research should explore additional variables that may affect credibility and how they intersect. Topics for future research should especially explore how fluidity in gender expression is understood by decision makers, how race and racialization effect credibility of trans claimants, the role of external evidence in establishing credibility of trans claimants (especially COI), how politics of deservingness interact with and are shaped by asylum adjudication, and how sur place gender identity claims compare to claims where being transgender is central to the asylum claim from the beginning.

Conclusion

This study analyzes factors underlying credibility assessments of transgender asylum claimants in Denmark. The mixed-methods analysis is grounded in a dataset of ~15,000 case summaries from the Danish Refugee Appeals Board and is informed by scholarship on transnormativity. The study culminates in an experiment where participants act as decision makers at the Refugee Appeals Board and are tasked with assessing the credibility of a simulated case concerning a transgender woman from Malaysia claiming asylum in Denmark. The experiment tests the effect of gender-affirming medical intervention and the timeline of coming out as trans on participants’ credibility assessments of the claimant, on their perceived risk of persecution, and on their willingness to grant the claimant refugee status.

Our study first finds a rise in the number of claims based on sexual orientation and gender identity over time, with a particularly high overturn rate at the Appeals level for transgender claimants, underscoring the need for a better understanding of how these claims are assessed. Second, results from our experimental study indicate that transgender claimants who have had gender-affirming medical intervention in their transition are more often deemed credible, perceived as being at risk of persecution, and granted asylum. This reliance on medical intervention is directly discouraged in soft law, such as UNHCR guidelines, but nevertheless appears to influence decision-making. Furthermore, the study finds a striking effect of the background characteristics of participants on their decision-making. Participants who identified as LGBT+ were consistently more likely to find the claimant credible and vote to grant protection. Conversely, men were significantly more likely to agree with the first instance’s conclusion that the narrative was constructed for the occasion, and to vote not to grant protection. Together, our findings raise legal and ethical considerations regarding the role of gender-affirming medical intervention in legitimizing transgender asylum claims, highlighting the role of bias and the discretionary power of decision makers in refugee status determination.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval for anonymous survey-based research involving human subjects is not required by the Danish Research Ethics Committee. Our research strictly adheres to the University of Copenhagen’s Code of Conduct for Responsible Research and the European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MH: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Visualization, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Methodology. AJ: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Funding for this research has been provided by the Danish National Research Foundation, grant no. DNRF169, the Villum Foundation, grant no. 69198 as well as the Algorithmic Fairness for Asylum Seekers and Refugees (AFAR) Project, funded by the Volkswagen Foundation under its Challenges for Europe Program.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Correction note

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the scientific content of the article.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^We use “SOGIE” in this study to refer to sexual orientation and/or gender identity and expression or sexual characteristics. Relatedly, we use “LGBT+” and “queer” as umbrella terms for people whose sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, or sexual characteristics lie beyond the scope of a cis-heteronormative spectrum.

2. ^We use “transgender” and “trans” interchangeably to refer to individuals whose gender identity and expression transcend the sex assigned to them at birth.

3. ^As of 2024, when this experiment was carried out, transgender individuals in Malaysia face criminal prosecution for ‘cross-dressing’, are often excluded from the labor force, and subjected to ill treatment from both non-state and state actors such as law enforcement. For additional information (see: Ghoshal, 2014; Human Rights Watch, 2021; Sulathireh and Ghoshal, 2019).

4. ^We chose to measure the effect of our manipulated variables across three outcome variables to account for potential acquiescence bias and social desirability bias. Acquiescence bias is the tendency for participants to select positive response options disproportionately more frequently than neutral or negative ones. Social desirability bias is the tendency for participants to answer questions in a manner that they think will be viewed more favorably by others.

5. ^Participant ID: R_7QDF1Chx5RRmuS0.

6. ^Participant ID: R_8yKNyoWiS4HWNAB.

7. ^Participant ID: R_49j2wbYQVX5meaZ.

8. ^e.g. Participant ID: R_5NfPT3xGVtreI62.

9. ^Joint cases C-199, C-200 and C-201/12 X,Y and Z v Minister voor Immigratie, Integratie en Asiel [2013] EU:C:2013:720.

10. ^Note that ‘transexual’ is a term emerging out of a medical understanding of gender non-conforming identity. Some individuals still identify with this term, while others find issue with the entanglement of medical institutions and intervention as a prerequisite for authenticating trans identity. For additional information see The SAGE Encyclopedia of Trans Studies (2021).

11. ^Participant ID: R_1rj4oCm5yuQ54PH.

References

Anderson, J., and Ferguson, R. (2018). Demographic and ideological correlates of negative attitudes towards asylum seekers: a meta-analytic review. Aust. J. Psychol. 70, 18–29. doi: 10.1111/ajpy.12162

Avgeri, M. (2021). Assessing transgender and gender nonconforming asylum claims: towards a transgender studies framework for particular social group and persecution. Front. Hum. Dyn. 3:653583. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2021.653583

Ballin, S. (2023). Four Challenges, Three Identities and a Double Movement in Asylum Law: Queering the ‘Particular Social Group’ after Mx M. Aust. Feminist Law J. 49, 141–157. doi: 10.1080/13200968.2023.2187527

Bansak, K., Hainmueller, J., and Hangartner, D. (2016). How Economic, Humanitarian, and Religious Concerns Shape European Attitudes toward Asylum Seekers. Science 354, 217–222. doi: 10.1126/science.aag2147

Berg, L., and Millbank, J. (2013). “Developing a Jurisprudence of Transgender Particular Social Group” in Fleeing Homophobia: Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Asylum. ed. T. Spijkerboer (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge), 33.

Cerezo, A., Morales, A., Quintero, D., and Rothman, S. (2014). Trans migrations: exploring life at the intersection of transgender identity and immigration. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 1, 170–180. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000031

Council of Europe. (2023). LGBTI Persons in the Asylum Procedure | HELP Programme. Council of Europe HELP Course on LGBTI Persons in the Asylum Procedure. 2023. Available at: https://help.elearning.ext.coe.int/course/section.php?id=80356, (Accessed May 09, 2025).

Cowling, M. M., Anderson, J. R., and Ferguson, R. (2019). Prejudice-relevant correlates of attitudes towards refugees: a meta-analysis. J. Refug. Stud. 32, 502–524. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fey062

D’Ignazio, C., and Klein, L. F. (2020). “What Gets Counted Counts” in Data Feminism. eds. C. D’Ignazio and L. F. Klein (The MIT Press), 97–124.

Danisi, C., Dustin, M., Ferreira, N., and Held, N. (2021). “SOGI Asylum in Europe: Emerging Patterns” in Queering Asylum in Europe. eds. C. Danisi, M. Dustin, N. Ferreira, and N. Held (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 421–444.

Dauvergne, C., and Millbank, J. (2003). Burdened by proof: how the Australian Refugee Review Tribunal has failed lesbian and gay asylum seekers. Fed. Law Rev. 31:299. doi: 10.22145/flr.31.2.2

DePaulo, B. M., and Pfeifer, R. L. (1986). On-the-job experience and skill at detecting deception1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 16, 249–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1986.tb01138.x

Dustin, M. (2018). Many Rivers to Cross: The Recognition of LGBTQI Asylum in the UK. International Journal of Refugee Law 30, 104–127. doi: 10.1093/ijrl/eey018

Dustin, Moira, and Held, Nina. (2018). “In or out? A Queer Intersectional Approach to ‘Particular Social Group’ Membership and Credibility in SOGI Asylum Claims in Germany and the UK.” University of Sussex. Available online at: https://hdl.handle.net/10779/uos.23463953.v2.

EUAA. (2022). “Asylum Interview Method” in Training Catalogue. Available at: https://euaa.europa.eu/training-catalogue/asylum-interview-method-0 (Accessed May 09, 2025).

Eurostat. (2024). “Asylum Applications - Annual Statistics - Figure 2: First-time asylum applicants by age and sex, 2024.” https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Asylum_applications_-_annual_statistics.

Ferreira, N. (2022). Utterly Unbelievable: The Discourse of ‘Fake’ SOGI Asylum Claims as a Form of Epistemic Injustice. Int. J. Refugee Law 34, 303–326. doi: 10.1093/ijrl/eeac041

Ghoshal, N. (2014). ‘I’m Scared to Be a Woman’: Human Rights Abuses against Transgender People in Malaysia. New York, NY: Human Rights Watch.

Gill, N., Hoellerer, N., Hambly, J., and Fisher, D. (2025). “Inside Asylum Appeals: Access, Participation, and Procedure in Europe” in Law and Migration. 1st ed (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge).

Goldberg, A. E., and Beemyn, G. (Eds.) (2021). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Trans Studies. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Granhag, P. A., Strömwall, L. A., and Hartwig, M. (2005). Granting asylum or not? Migration board personnel’s beliefs about deception. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 31, 29–50. doi: 10.1080/1369183042000305672

Gregurović, M., Kuti, S., and Župarić-Iljić, D. (2016). Attitudes towards Immigrant Workers and Asylum Seekers in Eastern Croatia: Dimensions, Determinants and Differences. Migracijske i Etničke Teme Migration and Ethnic Themes 32, 91–122. doi: 10.11567/met.32.1.4

Hellmann, D. M., Fiedler, S., and Glöckner, A. (2021). Altruistic Giving Toward Refugees: Identifying Factors That Increase Citizens’ Willingness to Help. Front. Psychol. 12:689184. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.689184