- The Faculty of Law, The Independent Institute of Education’s IIEMSA, Johannesburg, South Africa

This study critically explores the concept of displaced belongings in the context of post-colonial Southern Africa. It focuses on the systemic exclusion of indigenous and traditionally mobile communities. This is with particular reference to the legal and political frameworks of recognition of the Khoisan, San, Tsonga and Venda peoples. The imposition of arbitrary colonial borders, coupled with the dominance of Western legal systems, has undermined customary law and erased indigenous identity markers. As a result, these communities often face legal precarity, erasure and limited access to rights and services. Utilising a doctrinal and socio-legal review, this study examines how post-independence citizenship regimes have failed to address the border induced fragmentation of indigenous belonging. The study traces how the colonial carving of territories disrupted cross-border kinship and spatial arrangements and how this left many communities marginalised in the very regions that they historically inhabited. The study also assesses the extent to which international legal instruments such as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the ILO Convention No. 169 offer frameworks for redress and recognition. The research advocates for a reimagining of citizenship that accommodates plural legal traditions, honours indigenous identities and responds to the unique forms of displacement that is experienced by cross border communities in Southern Africa.

1 Introduction

Contemporary borders in Africa are the enduring legacy of colonial cartographies that rarely aligned with indigenous spatial or cultural realities (Kizito, 2019). As a result, many indigenous communities today find themselves fragmented across multiple national jurisdictions. They are not necessarily displaced by physical migration, but in more instances, by the redrawing of maps that redefined who belongs where and under what terms.

This study examines the consequences of these imposed borders for the recognition and rights of the Khoisan, San, Tsonga and Venda peoples in Southern Africa. Despite increasing global commitments to diversity and indigenous rights, post-colonial states often retain legal and administrative systems grounded in Western notions of citizenship, identity and legal personhood (Blanco and Grear, 2019). These frameworks frequently fail to accommodate non-Western markers of belonging, including customary law and oral history.

The results is not just bureaucratic exclusion, but also a deeper, ontological form of displacement. Many indigenous communities face a form of non-belonging where they are rendered as invisible in legal systems and national narratives, despite a long-standing presence in that region (Koot et al., 2019). This legal and symbolic marginalisation carries tangible effects such as diminishes access to land, diminished political participation, as well as cultural expression (Madlingozi, 2018).

This study interrogates the legal, historical and socio-political mechanisms that sustain these exclusions. It adopts a critical legal lens to examine how law has operated as both a tool of dispossession and a possible avenue for redress. In doing so, it argues for a reconceptualisation of citizenship and recognition that moves beyond state-centric logics and embraces the plural legal realities and lived experiences of indigenous communities in Southern Africa.

2 Theoretical framework (the politics of belonging, decoloniality and legal pluralism)

This study frames its inquiry through the lens of the politics of belonging. Belonging is not viewed merely as a legal status granted by the state. It is a dynamic, contested process that is shaped by historical power relations and socio-political hierarchies (Yuval-Davis, 2006). In post-colonial contexts, this negotiation of belonging becomes especially fraught. For indigenous and traditionally mobile communities, belonging has always existed outside the confines of Western legal codification. Their kinship-based affiliations, oral legal systems and non-territorial identities frequently clash with state-centric models of citizenship and identity.

The politics of belonging reveals that the state does not simply recognise identities, it actively constructs, includes and excludes them (Hall, 2013). Through administrative tools such as birth registration, identity documentation and partial recognition of customary laws, the state defines who belongs and who does not (Youkhana, 2015). While this study in no way aims to disenfranchise formal documents of identification, the objective submission would be that the aforementioned decisions often result in a form of displaced belonging. Here, communities with deep rooted historical claims to place and identity are possibly denied visibility in law and subjected to likely cultural erosion.

This theoretical lens allows for an interrogation of how belonging is “weaponised.” The very mechanisms that should affirm identity are seemingly used to deligitimise it. In this instance, the state becomes not just a neutral arbiter of legal status, but a powerful gatekeeper of belonging. The Khoisan, San, Tsonga and Venda are not simply marginalised by accident, rather, it would appear that they are excluded by design.

Building on the above, this research also draws on decolonial legal theory to unpack the ensuring influence of coloniality in contemporary legal systems. While many African states achieved formal independence, their legal infrastructures often remained tethered to colonial logics. Some even argue that modern citizenship regimes are still shared by the colonial matrix of power which continues the privileging of Western legal traditions while marginalising indigenous epistemologies and systems of governance (Bhambra, 2015). This study emphasises on the harmonious co-existence of both systems and does not advocate for the eradication of either of the legal traditions. The aim would be for more recognition of indigenous epistemologies to maintain the identity and lived experiences of the majority of Africans, while drawing from and benefiting from the solutions sometimes rendered to complex issues by Western legal traditions. Decolonial theory exposes the structural inequality in recognition (Pillay, 2021). When states choose which aspects of customary law to recognise, they do not fully accommodate diversity (Kyomuhendo, 2025). They assert authority over indigenous systems which can distort or erase them in the process (Kyomuhendo, 2025). This reinforces a hierarchy of knowledge and law, with Western legal norms at the top.

Legal pluralism provides an important counterpoint. In practice, multiple legal orders operate simultaneously. State law coexists with living customary law (Olaf and Markus, 2018). But this coexistence is rarely harmonious (Olaf and Markus, 2018). State legal frameworks often impose structures that deny the legitimacy of parallel systems (Olaf and Markus, 2018). For indigenous communities, this creates a tension between legal recognition and legal erasure. Kinship based inheritance and spiritual relationships to land are frequently invalidated under the formal legal frameworks.

The struggles of the San, Tsonga and Venda peoples exemplify this. Their identities and legal traditions are not simply overlooked. Rather, they are undermined by the very state systems that claim to represent them. Through these combined lenses of belonging, decoloniality and pluralism, this article critiques the role of law, not just as a mirror of power, but rather, as its active enforcer.

3 Methodology

This study adopts a doctrinal research methodology. It is primarily analytical in nature, and it focuses on the interpretation and critique of legal texts, case law, legislation and international instruments (Vranken, 2010). The objective is to explore how indigenous identity and customary are treated within legal systems in Southern Africa. There is a particular focus on the impact of the post-colonial borders and state recognition frameworks. This research methodology allows for an examination of the law as it is. Based off of the indigenous groups examined, it also includes the analysing of statutes, constitutions and legal policies in South Africa, Botswana, Zimbabwe and Mozambique. The study reviewed judgements and government documentation to assess how legal recognition to identity is extended or denied to indigenous communities, particularly the San, Tsonga and the Venda peoples.

Secondly, literature including anthropological and historical texts was also used to contextualise the development of customary legal systems and their interaction with colonial and post-colonial regimes.

Thirdly, international legal frameworks such as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (from hereunder referred to as the “UNDRIP”) and the ILO Convention No. 169, were critically evaluated to assess their influence on domestic legal recognition as well as protection mechanisms.

No empirical or field-based research was conducted. All materials used were publicly accessible through academic databases, government websites, legal repositories and digital archives. This study did not involve human subjects and therefore falls outside the scope of research requiring ethical clearance.

4 The cartographic violence of colonialism and its hand in border controls, identity and dispossession

Colonialism fundamentally reshaped the political and social landscape of vast regions, particularly in Africa (Christopher, 2023). This reshape extended far and beyond physical occupation (Christopher, 2023). The arbitrary creation of borders during events like the Berlin Conference (1884–1885), formalised the division of the continent among the European colonial powers (Rwigema, 2025). In the process of this division, there was insufficient regard for pre-existing ethnic and cultural entities (Rwigema, 2025). This disregard for the established social structures led to fragmented communities (Eseka, 2020).

A salient illustration of border-induced identity fragmentation can be found among the Tsonga people. Historically, Tsonga people were located in Southern Mozambique and Northeastern South Africa (Madlome and Chauke, 2019). They now also present significant presence in Zimbabwe and eSwatini (Madlome and Chauke, 2019). These Tsonga communities share language, customs and heritage (Mabunda, 2023). Despite this, the colonial boundaries divided them across newly formed nation states (Madlome and Chauke, 2019). Over time, this division has contributed to their classification as ethnic minorities in each of the aforementioned countries. It also cultivated a fragmented sense of identity that is shaped more by national borders than it is by shared history.

Similarly, the Venda-speaking communities have long spanned the area that is now split by the South Africa and Zimbabwe border post (Loubser, 1989). Historically, these communities maintained adaptive and mobile practices that were not bound to the rigid territorial boundaries (Loubser, 1989). Moyo posits that their social and cultural systems have remained dynamic, highlighting the resilience of pre-colonial structures in the face of external impositions (Moyo, 2016). However, the drawing of the border state lines created legal and political consequences. As a matter of fact, it redefined these groups as minorities and introduced new forms of marginalisation that is rooted state-centric systems of recognition.

Beyond the physical demarcations, colonialism also introduced a distinct legal and epistemological framework. It either replaced or displaced existing indigenous systems of knowledge, law and even governance. The very concept of “indigeneity” was shaped within the colonial and anthropological discourses. Simpson submits that disciplines historically sought to define and categorise indigenous peoples for the purposes of administration, extraction and control (Simpson, 2007). It can be argued that in doing so, they contributed to the marginalisation of indigenous authority and ways of knowing which in turn, eroded identity.

This transformation often involved the systemic privileging of settler legal systems. Indigenous models of political organisation and communal life were not simply disregarded, rather they were often invalidated. In South Africa specifically, the long legacy of colonialism and apartheid entrenched a legal order that subordinated customary law (Simpson, 2007). Indigenous systems were recognised only when they served governance or when they could be modified to align with dominant legal norms (Chirayath et al., 2005).

The “violence of form” that is described by Simpson (2007) captures how the dominant narrative frameworks of colonial rule rendered indigenous voices and epistemologies as imperceptible. These systems of thought were not only excluded but were made unknowable within the dominant legal and academic discourses. A powerful historical example is the doctrine of terra nullius, which assumed that any land that was not governed by Western forms of tenure was legally unoccupied (Coleman, 2017). In Australia, this doctrine justified dispossession until it was overturned in 1992 (Coleman, 2017). Some similar legal constructs in Africa, while not always named as such, have a appeared in other colonial contexts and they have also produced parallel effects of identity erasure and cultural exclusion.

This process created a lasting disjuncture. Belonging became defined by the state, through its laws and borders. The “cartographic violence” extended beyond maps and borders. It reshaped identity, legitimacy and more importantly, the authority to define law. Non-Western firms of belonging, including oral traditions and customary governance, were increasingly sidelined. As Simpson (2007) notes, the historical transition from colony to nation-state often silenced the indigenous peoples’ claims to land and identity, not only by physical dispossession but also through epistemic disqualification. The imposition of colonial borders and knowledge systems continues to affect the contemporary struggles for recognition. These struggles are not only about land or citizenship, but also about authority to define identity and the validity of indigenous legal systems. The efforts to reclaim belonging often challenge the singular authority of the state by asserting plural forms of law and identity, grounded in histories that predate the state itself.

5 Customary law, legal personhood and the state’s gaze

Indigenous identity is often defined be self-identification, a strong attachment to ancestral land, the preservation of cultural distinctiveness and a shared experience of marginalisation (Jacobs, 2019). These elements form a collective way of life that exists independently of state approval. For groups like the San, identity has been shaped through decentralised structures (Taylor, 2012). These communities were traditionally organised into small kinship-based groups without any hierarchical political authority. This led some scholars to describe them as “stateless societies” (Hansen, 2015).

Their customary law systems were grounded in oral tradition (Ouzman, 2010). They reflected community norms, and they were adaptive (Ouzman, 2010). They constantly evolved to meet changing circumstances (Ouzman, 2010). Before colonial rule, such laws and practices held authority by virtue of practice and communal acceptance. Their legitimacy was not dependant on written codification, but on continuity and lived experience (Hansen, 2015).

In post-colonial legal systems, recognition of customary law has been uneven and contested. South Africa’s 1996 Constitution explicitly recognises customary law and traditional leadership as integral components of the legal system. However, the practicalities of the recognition can still be found to be enigmatic with courts and employers failing to understand, promote or uphold cultural practices in professional environments (Kugara and Chawaremera, 2024). Efforts to codify customary law such as the Republic of South Africa (1998) and the Reform of Customary Law of Succession Act (2009), were intended to harmonise traditional practices with constitutional principles. However, codification has risks. Once codified, the dynamic nature of customary law can become static. Without institutions empowered to amend these codified norms, discriminatory or outdated practices may be entrenched over time. Codification, though aimed at inclusion, may undermine the flexible, evolving and community driven character of customary systems.

The Traditional and Khoi-San Leadership Act of 2019 (from hereunder referred to as the “TKLA”) illustrates the complexity of legal recognition. While it sought to formally recognise Khoi-San leadership structures, the Act was declared unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court in 2023 due to insufficient public consultation (Osman, 2024). More critically, the Act applied different jurisdictional rules to Khoi-San leaders compared to other traditional authorities. Their councils were given authority over individuals by voluntary affiliation, rather than over land or communities within specific geographic areas (Osman, 2024). This signals selective recognition. It limits the authority of Khoi-San leadership in ways not imposed on other traditional communities. Such recognition may appear inclusive, but in practice, it actually reproduces asymmetries of power. The state defines the conditions under which customary law is recognised, often reshaping it in the process. In doing so, the state risks transforming a living legal tradition into a fixed legal category that fits state systems but not community realities. In instances as such, recognition becomes a form of control. It imposes external structures onto indigenous systems. Furthermore, it displaces traditional authority and autonomy, even while appearing to acknowledge them. This paradox resultantly perpetuates “displaced belongings” within legal frameworks designed to promote inclusion.

The legal implications of non-recognition or partial recognition are significant. Migrants from Zimbabwe, including Venda and Tsonga individuals with ancestral ties to South Africa, often face legal precarity. Despite shared histories, they are frequently viewed as outsiders and economic migrants, rather than historical kin (Moyo, 2016). The result is exclusion, insecure legal status and unfortunately, xenophobia.

The San communities in Botswana and Namibia faces similar challenges. In the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, state policies have restricted access to ancestral land and disrupted traditional livelihoods (Hitchcock, 2006). Though not stripped of citizenship, these communities face statelessness-like conditions. They are excluded from legal recognition and the right to self-determination. These conditions are often compounded by competing state interest in mining and development (Hitchcock, 2006).

Legal challenges also persist within family law. In Zimbabwe, widespread customary marriages often go unregistered (Vengesai, 2024). This undermines the property rights of women, and it limits cultural recognition (Vengesai, 2024). Civil marriages receive legal protection, while traditional unions are often left outside the formal legal system (Vengesai, 2024). While South Africa has made strides through the Republic of South Africa (1998), implementation in some instances, remains a challenge. Unfortunately, many citizens lack knowledge of the laws or access to legal services, and this undermines the law’s intended effect.

The examples scaffolded above point to a broader issue. The struggle for recognition is not just about legal rights, it is about legal authority. It challenges the post-colonial state’s monopoly over the definition of personhood, belonging and citizenship. Indigenous legal systems must be recognised and not as supplementary, but as co-existing and legitimate in their own right.

This requires more than policy reform. It calls for a shift in the legal imagination that decolonises recognition and restores power to communities to define their own systems of belonging.

6 Citizenship as a mechanism of exclusion (case studies from Southern Africa)

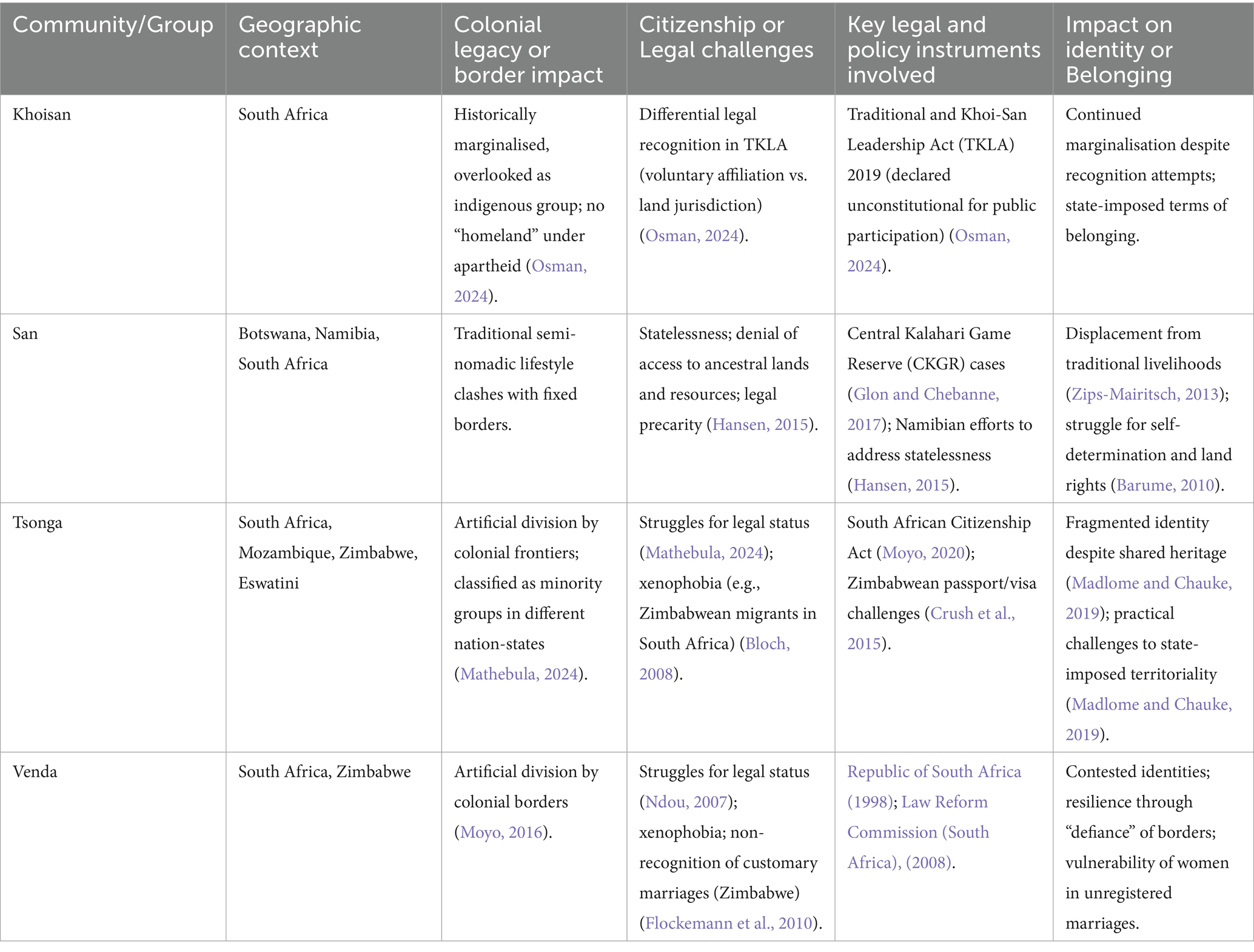

The legacies of colonial rule and the ensuring structures of state-centric citizenship are made visible in the lived experiences of indigenous and cross-border communities in Southern Africa (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2018). These communities continue to navigate legal systems that often exclude their traditional forms of belonging (Blaauw, 2007). Through comparative case studies, this section illustrates how rigid territorial frameworks and narrow definitions of legal personhood disrupt long-standing identities and undermine legal recognition. The communities that are illustrated in the Table 1 and then discussed thereafter exemplify the multiple layered ways in which colonial boundaries and modern legal systems have produced “displaced belongings.”

Table 1. Illustrative case studies on impact of citizenship regimes on indigenous and cross border communities.

6.1 The Khoisan and the San struggles for recognition and nationality

The Khoisan remain amongst the most marginalised indigenous groups in South Africa. Despite being recognised as the country’s “first people,” they were excluded from the apartheid-era homeland system. This historic omission still echoes in their present-day legal standing (Osman, 2024). The TKLA sought to address this by creating a legal mechanism for recognising Khoisan leadership. However, its eventual declaration of invalidity by the Constitutional Court in 2023 due to inadequate public participation underscores the limited space afforded to indigenous voices in the law-making processes (Osman, 2024). In this matter, the Court found that the affected communities in rural and marginal groups, particularly, were not adequately informed. This was because notices of hearings were not accessible to all, bill summaries were insufficient or unavailable, the translations were poor, and key voices were supposedly sidelined. As a result, the TKLA was passed in a way that violated sections 59 and 72 of the South African Constitution. The invalidity order was suspended for 24 months and in 2025, has now been suspended for a further 24 months to allow Parliament to draft legislation that would replace the Act.

The TKLA also introduced a different basis of jurisdiction for Khoisan councils. Unlike other traditional authorities whose jurisdiction is linked to territory, the TKLA subjected Khoisan leadership to voluntary affiliation (Osman, 2024). This placed Khoisan structures at a relative disadvantage, reinforcing the unfortunate notion that recognition is extended only on terms defined by the state. The result is then a form of constrained recognition that does not fully embrace traditional forms of governance. It reflects a broader trend in which legal recognition becomes conditional, often transforming the living systems into static and state-sanctioned categories.

The San are a semi-nomadic people with historic presence across Botswana, Namibia and South Africa (Zips-Mairitsch, 2013). They face even sharper tensions between state frameworks and indigenous mobility. Their traditional forms of social organisation which are often decentralised and kin-based, have clashed with territorialised models of statehood and legal personhood. In Botswana, the Central Kalahari Game Reserve conflict highlights how economic interests and state policies converge to displace indigenous communities (Glon and Chebanne, 2017). The forced removals from ancestral lands and denial of access to water resources represent an indirect form of dispossessions that renders traditional ways of life unsustainable.

Namibia, on the other hand, has taken steps to address the issue of statelessness among the historically marginalised groups (Shekeni, 2018). These include birth registration campaigns and naturalisation pathways (Shekeni, 2018). However, these efforts often fall short of addressing the deeper structural dissonance between indigenous belonging and formal citizenship. The San peoples’ cross-border presence, oral legal traditions and non-territorial modes of identity remain largely incompatible with dominant legal and policy frameworks. As a result, they continue to face legal precarity and barriers to full participation in national life.

6.2 The Tsonga and the Venda peoples navigating artificial divides

The Tsonga people who are found across South Africa, Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Eswatini, embody the lived consequences of colonial border-making (Madlome and Chauke, 2019). By being divided into separate states, these communities have been reclassified as ethnic minorities, despite their shared linguistic and cultural heritage (Madlome and Chauke, 2019). This division has led to fragmented identities and not because of cultural differences, but rather, because of externally imposed state structures.

The Venda-speaking communities similarly straddle the South Africa-Zimbabwe border (McNeill, 2016). Historically mobile and adaptive, they continue to participate in informal cross border activities that defy the rigidity of state boundaries (Moyo, 2016). These include trade, kinship networks and even “double identities” to access resources and legal protections in both countries (Moyo, 2016). Such practices reflect both resilience and necessity. They are survival strategies in the face of exclusionary citizenship laws that offer little accommodation for hybrid or transnational identities.

Unfortunately, formal legal systems often exacerbate these challenges. Zimbabwean Venda and Tsonga migrants in South Africa frequently face xenophobia, even when they have deep historical and familial ties to the region. Their legal status is precarious. They have to navigate passport regulations; work permits and residency laws to survive within legal systems that fail to account for ancestral belonging. These struggles are compounded by citizenship laws that rely on rigid interpretations of jus soli and jus sanguinis which limit access to formal documentation and basic services.

Recent developments in South African nationality law suggest a shift towards inclusivity. The Constitutional Court’s decision to strike down the automatic loss of South African citizenship due to acquisition of foreign nationality marks a positive step (Ernst and Young Global, 2025). It aligns the law with international efforts to prevent statelessness. However, for cross-border communities, this reform does not resolve the deeper issue of state-defined belonging. When one’s primary identity is rooted in community rather than country, legal personhood remains contingent on frameworks that fail to accommodate plural forms of identity.

The legal recognition of customary marriage provides another lens through which this disjuncture is observed. In Zimbabwe, unregistered customary marriages are common, but they lack full legal standing. This disproportionately affects women, particularly in relation to property and inheritance rights. These marriages fall outside the scope of general law, creating a tiered system that privileges civil marriages over traditional unions. South Africa’s Republic of South Africa (1998) was a progressive response to this inequality. However, its impact is limited by poor public awareness and inadequate access to legal services.

These examples point to a deeper structural issue. Legal reforms, however well-intentioned, often fail to address the lived realities of indigenous and cross-border communities. They do not account for historical and cultural contexts that shape these communities’ understanding of identity and belonging. The persistence of “displaced belongings” reveals that the state continues to exercise a monopoly over recognition. It defines who belongs, on what terms, and through which legal frameworks. Until legal pluralism is embraced fully and not just in theory, but in practice, many communities will remain on the margins as seen but not fully recognised.

7 International human rights as a framework for recognition and redress

International and regional legal frameworks provide important normative guidance for recognising indigenous rights, customary laws and nationality. These instruments reflect growing international consensus on the need to protect cultural identity and prevent statelessness. While their legal force varies, they still serve as significant refence points for critique and advocacy for legal reform.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights if Indigenous Peoples (from hereunder referred to as “UNDRIP”), adopted in 2007, is the most comprehensive international instrument on indigenous rights, It affirms the right to self-determination, equality and non-discrimination (UN General Assembly, 2007). It also recognises the right to maintain distinct political, legal, economic, social and cultural institutions (UN General Assembly, 2007). Cultural integrity is affirmed through the protection of traditional customs and practices. Crucially, Article 6 confirms that every indigenous person has the right to a nationality. The Declaration also outlines the principle of free, prior and informed consent, which requires that states engage in genuine consultation with indigenous communities before adopting measures that affect them (UN General Assembly, 2007). Although non-binding, UNDRIP sets minimum international standards, and it upholds strong normative value.

Complementing UNDRIP, is ILO Convention No. 169 on the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, adopted in 1989. Unlike UNDRIP, this Convention is a legally binding treaty for ratifying states. It recognises the legal validity of indigenous customary law, and it ensures the right to participate in decision making (International Labour Organization (ILO), 1989). The Convention acknowledges trans-border cooperation and confirms that indigenous peoples must enjoy all general rights of citizenship without discrimination (International Labour Organization (ILO), 1989). However, its global impact is limited due to low ratification rates, especially in Africa.

In the African context, the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) (1981) remains foundational. It recognises the right to self-determination and cultural identity (Organisation of African Unity (OAU), 1981). It emphasises equality and it prohibits discrimination based on ethnic or cultural affiliation. Importantly, it affirms the rights of “peoples” rather than only individuals (Organisation of African Unity (OAU), 1981). This framing allows for the collective rights of indigenous and cross border communities to be asserted, particularly in relation to cultural survival and land rights. The Charter also calls for the protection of traditional values and institutions (Organisation of African Unity (OAU), 1981). Despite these provisions, once again, implementation varies across states and its principles are often broad and general.

The African Union has taken further steps to address nationality and statelessness through the Draft Protocol on Specific Aspects of the Right to a Nationality and the Eradication of Statelessness in Africa. This Protocol acknowledges that Africa’s colonial history has produced unique challenges regarding borders and citizenship. It explicitly promotes the right to a nationality and birth registration for all children (African Union, 2024). It also prohibits discrimination in the transmission of nationality, particularly against women (African Union, 2024). The Draft Protocol pays special attention to nomadic communities, recognising their historical vulnerability to legal exclusion. Although it is progressive, the instrument is still awaiting ratification and national implementation.

Mobility within the Southern African region is also addressed by the SADC Protocol on the Facilitation of Movement of Persons (Southern African Development Community, 2005). This Protocol encourages visa-free entry and aims to eliminate obstacles to regional movement. It promotes cooperation among states on migration, security and border control (Southern African Development Community, 2005). However, its focus is on formal state regulated mobility. It does not sufficiently accommodate the lived realities of customary, informal cross-border movements rooted in kinship and culture.

Despite the normative strength of these instruments, national implementation remains uneven and slow. In many states, domestic laws continue to reflect strong state-centric models. Legal systems are often reluctant to fully incorporate customary law, especially where it appears to challenge state authority or dominant constitutional norms. Moreover, instruments such as the UNDRIP, while influential, are not legally binding. ILO Convention No. 169, though not binding, has not been widely ratified. Even progressive efforts like the AU Draft Protocol or Statelessness remain pending and unenforced. Meanwhile, regional institutions such as the African Union continue to affirm respect for colonial borders as a principle of stability. This creates a structural tension. On one hand, international norms advocate decolonial approaches to law and belonging. On the other hand, national and regional politics often prioritise sovereignty and border control. However, these instruments remain important advocacy tools. They empower marginalised communities to assert their rights on a legal and moral basis. The San people’s appeal to the United Nations in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve case illustrates this strategic use of global law. In South Africa, specifically, recent Constitutional Court Judgements have advanced more inclusive interpretations of citizenship. It aligns local practice more closely with international human rights standards.

Finally, the principle of free, prior and informed consent serves as a critical benchmark. It calls for a genuine shift in how legal recognition is approached. Rather than imposing recognition through fixed legal definitions, states are called to co-create legal frameworks with affected communities. This approach respects indigenous autonomy and affirms their right to define their own legal and cultural identities.

In sum, international and regional instruments offer a roadmap for more inclusive legal systems. However, their potential will remain unrealised unless states are willing to adopt and implement them in good faith. The challenge is not only legal but political. It requires and intentional shift in power and perspective. A shift towards pluralism and meaningful participation.

While the international and regional instruments outlined above provide a crucial normative framework, their effectiveness ultimately deepens on the extent to which they are integrated into domestic legal systems. The doctrine of incorporation or domestication remains a very decisive factor in determining whether indigenous and cross-border communities can invoke these protections in national courts. In the Southern African context, different states adopt different approaches. South Africa follows a monist approach under section 231 of the Constitution. This means that international treaties become binding once ratified by Parliament. This also allows communities to use instruments such as the African Charter and UNDRIP (albeit non-binding) as persuasive authority in litigation. By contrast, Zimbabwe and Botswana adopt more dualistic approaches. In their instances, international instruments must first be domesticated through legislation before they can have direct legal effect. This creates gaps between international commitments and lived realities on the ground.

At the national level, constitutional provisions provide an important entry point for enforcing the rights of marginalised groups. South Africa’s Bill of Rights guarantees equality (section 9), dignity (section 10) as well as cultural recognition (section 31). Section 211 of the Constitution further recognises the role of customary law and traditional leadership, subject to the Constitution. The Constitutional Court has repeatedly affirmed that customary law enjoys equal status with common law, provided it aligns with constitutional principles. This recognition has enabled indigenous communities to challenge restrictive state practices as seen in litigation surrounding the TKLA.

Regionally, in the Southeastern African context, the African Commission on Human Rights and Peoples’s Rights (from hereunder referred to as the “ACHPR”) has interpreted the African Charter to affirm the land and cultural rights of indigenous peoples. For example, in the Centre for Minority Rights Development (Kenya) and Minority Rights Group International on behalf of Endorois Welfare Council v Kenya (2009), the ACHPR issued a judgment stating that the Kenyan government had violated the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, specifically the rights to religious practice, to property, to culture, to the free disposition of natural resources, and to development. Although this is not a southern African case, it establishes persuasive regional precedent that can be invoked by communities such as the San and Khoisan to argue for recognition and redress.

When they are taken together, these layered frameworks highlight an important paradox. On paper, indigenous peoples in Southern Africa benefit from a dense web or rights across international, regional and national levels. However, in practice, enforcement is often fragmented and also selective. This therefore underscores the need not only to ratify and reference international instruments, but, also, to embed them meaningfully into domestic law and administrative practice. In reality, only then can they serve as effective tools for recognition rather than symbolic gestures.

8 Conclusion and recommendations

This study has explored how the colonial imposition of borders and the entrenchment of Western legal systems have contributed to the displacement of indigenous and cross border communities in Southern Africa. This condition of “displaced belongings” is not merely symbolic. It is material and legal. It is reflected in the denial of citizenship, the erosions of customary law, the marginalisation of traditional governance and the erasure of non-Western identity frameworks.

The case studies of the Khoisan, San Tsonga and the Venda demonstrate the lived reality of this displacement. These communities remain caught between the boundaries of modern states and their own inherited forms of belonging. While some progress has been made through constitutional protections and regional instruments, many of these communities continue to experience exclusion. The state remains the central arbiter of identity. Legal recognition often comes on the state’s terms which sometimes reproduces colonial hierarchies under the guise of post-colonial governance.

However, these communities are not passive. Their resilience is evident in the way they resist imposed identities in order to sustain their ways of life. For instance, despite being artificially divided by colonial borders, the Tsonga and Venda people continue to participate in informal cross-border activities, such as trade and kinship networks. Unfortunately, they even develop “double identities” to access resources and legal protections in both South Africa and Zimbabwe. These are not just anomalies, but rather, they are survival strategies in the face of exclusionary citizenship laws that offer little accommodation for hybrid or transnational identities. Similarly, the Khoisan and San peoples, despite facing legal precarity and marginalisation, continue to assert their land rights through legal challenges as was done in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve matter. Thes actions do demonstrate the persistence of plural forms of law and identity that predate the state itself. Their defiance of state-centric citizenship models reveals the limits of current legal and political frameworks. It also points to the possibility of a more inclusive and plural legal order that honours history, context and community.

The below policy and legal recommendations are rendered.

8.1 Decolonising citizenship laws

States should reform citizenship laws to reflect more inclusive understandings of belonging. This includes recognising customary affiliation., oral traditions and community-based identity markers. The overreliance or territorial or bloodline principles must be critically re-evaluated. Historical biases rooted in colonial kinship norms must be actively dismantled.

8.2 Genuine and dynamic recognition of customary law

Customary Law must not be reduced to static codes. Legal systems should reflect its living, evolving and community-driven nature. Recognition must be participatory and not and symbolic. The failure of the TKLA reveals the dangers of state defined recognition that lacks genuine co-creation with affected communities.

8.3 Protection of cross border and nomadic communities

Legal and policy frameworks must account for traditional mobility and cross border affiliations. These are not anomalies but long-standing modes of existence. States must ensure access to documentation, services and legal protection of these communities, irrespective of rigid territorial frameworks. Regional cooperation will be essential to combat statelessness and promote inclusive mobility.

8.4 Strengthening international and regional instruments

Ratifying and implementing instruments like the ILO Convention No. 169 should be prioritised while none binding instruments like UNDRIP must be treated as moral and legal compasses for national reforms. Furthermore, the principle of free, prior and informed consent must guide all legislative and administrative decisions affecting indigenous communities.

To belong is to be seen, heard and valued on one’s own terms. It is a human need as much as it is a legal right. In recognising and restoring displaced belongings, we do more than correct legal injustices, we affirm the dignity of people’s histories, laws and identities that have been made invisible. Belonging is not a favour granted by the state. It is a truth that must be honoured.

Author contributions

MC: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

African Union (2024). The draft protocol on specific aspects of the right to a nationality and the eradication of statelessness in Africa.

Bhambra, G. K. (2015). Citizens and others: the constitution of citizenship through exclusion. Alternatives 40, 102–114. doi: 10.1177/0304375415590911

Blaauw, L. (2007). Transcending state-centrism: New regionalism and the future of southern African regional integration. Doctoral dissertation, Rhodes University.

Blanco, E., and Grear, A. (2019). Personhood, jurisdiction and injustice: law, colonialities and the global order. J. Hum. Rights Environ. 10, 86–117. doi: 10.4337/jhre.2019.01.05

Bloch, A. (2008). Gaps in protection: undocumented Zimbabwean migrants in South Africa. Migration Studies Working Paper Series, 38, pp. 1–19.

Centre for Minority Rights Development (Kenya) and Minority Rights Group International on behalf of Endorois Welfare Council v Kenya (2009). Communication 276/2003, African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights. Available online at: https://www.escr-net.org/resources/the-endorois-case/ (Accessed August 30, 2025).

Chirayath, L., Sage, C., and Woolcock, M. (2005). Customary law and policy reform: Engaging with the plurality of justice systems.

Crush, J., Chikanda, A., and Tawodzera, G. (2015). The third wave: mixed migration from Zimbabwe to South Africa. Canadian J. Afr. Stud. 49, 363–382. doi: 10.1080/00083968.2015.1057856

Ernst and Young Global. (2025). South Africa’s Constitutional Court declares automatic loss of South African citizenship unconstitutional. Available online at: https://www.ey.com/en_gl/technical/tax-alerts/south-africas-constitutional-court-declares-automatic-loss-of-south-african-citizenship-unconstitutional (Accessed: 24 June 2025).

Eseka, E. V. (2020). “This Berlin Wall that Runs through Me”: Making Sense of the Postcolonial African Alienation. UC Santa Barbara: Undergraduate Research and Creative Activities Journal. Available online at: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2693533n.

Flockemann, M., Ngara, K., Roberts, W., and Castle, A. (2010). The everyday experience of xenophobia: performing the crossing from Zimbabwe to South Africa. Crit. Arts 24, 245–259. doi: 10.1080/02560041003786516

Glon, E., and Chebanne, A. (2017). ‘The san of the “central Kalahari game reserve”: can nature be protected without the indigenous san of Botswana?’. (no further publication details available from the provided text for full Harvard format).

Hall, S. M. (2013). The politics of belonging. Identities 20, 46–53. doi: 10.1080/1070289X.2012.752371

Hansen, J. (2015). Written in the sand; the san people, statelessness and the logic of the state. (No further publication details available from the provided text for full Harvard format).

Hitchcock, R. K. (2006). ‘We are the owners of the land’: the san struggle for the Kalahari and its resources. Senri Ethnol. Stud. 70, 229–256. doi: 10.15021/00002632

International Labour Organization (ILO). (1989). Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (No. 169). Adopted 27 June 1989, entered into force 5 September 1991. Geneva: ILO. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C169 (Accessed June 25, 2025).

Jacobs, B. (2019). Indigenous identity: summary and future directions. Stat. J. IAOS 35, 147–157. doi: 10.3233/SJI-190496

Kizito, K. K. (2019). ‘Borders as documents of violence: colonial cartography and the epidermal border’. (no further publication details available from the provided text for full Harvard format).

Koot, S., Hitchcock, R., and Gressier, C. (2019). Belonging, indigeneity, land and nature in southern Africa under neoliberal capitalism: an overview. J. South. Afr. Stud. 45, 341–355. doi: 10.1080/03057070.2019.1610243

Kugara, S. L., and Chawaremera, M. M. (2024). The tensions between Ukuthwasa and labour laws in South Africa: a human rights-based approach. E-Journal Human. Soc. Sci. Stud. 5, 2973–2985. doi: 10.38159/ehass.202451623

Kyomuhendo, A. (2025). The modern state, imperial law, and decolonial possibilities: assessing the effectiveness of law in protecting cultural heritage in Africa during and after colonialism. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 31, 477–495. doi: 10.1017/S0940739125000141

Law Reform Commission (South Africa). (2008). The Commission’s report on the Customary Law of Succession, ZALRC Report No. 1. Pretoria: ZALRC. Available at: https://www.saflii.org/za/other/ZALRC/2008/1.pdf (Accessed October 2, 2025).

Loubser, J. H. (1989). Archaeology and early Venda history. Goodwin Series 6, 54–61. doi: 10.2307/3858132

Mabunda, G. M. (2023). Expansion of South African Xitsonga terminology through importing from agrarian pursuits of Xitsonga linguistic communities in Mozambique and Zimbabwe. MA dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand

Madlingozi, T. (2018) Mayibuye iAfrika?: Disjunctive inclusions and black strivings for constitution and belonging in’south Africa’. Doctoral dissertation, Birkbeck, University of London.

Madlome, S. K., and Chauke, O. R. (2019). ‘Conflict, justice and peace from an African indigenous cultural perspective: The case of the Vatsonga people of Mozambique, South Africa, Swaziland and Zimbabwe’, Violence, Peace and Everyday Modes of Justice and Healing in Post-Colonial Africa, 327.

Mathebula, M. M. (2024). Bounding the frontiers: an assessment of the Gaza’s relations with the Hlengwe of Zimbabwe (1835–1895). New Contree 91:247. doi: 10.4102/nc.v91i0.247

McNeill, F. G. (2016). “Original Venda hustler”: symbols, generational difference and the construction of ethnicity in post-apartheid South Africa. Anthropol. South. Afr. 39, 187–203. doi: 10.1080/23323256.2016.1209725

Moyo, I. (2016). The Beitbridge–Mussina interface: towards flexible citizenship, sovereignty and territoriality at the border. J. Borderl. Stud. 31, 427–440. doi: 10.1080/08865655.2016.1188666

Moyo, I. (2020). On borders and the liminality of undocumented Zimbabwean migrants in South Africa. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 18, 60–74. doi: 10.1080/15562948.2019.1570416

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2018). ‘Decolonising borders, decriminalising migration and rethinking citizenship’, Crisis, identity and migration in post-colonial Southern Africa, 23–37.

Ndou, M. R. (2007). The gospel and Venda culture: An analysis of factors which hindered or facilitated the acceptance of Christianity by the Vhavenda. Doctoral dissertation, University of Pretoria.

Olaf, Z., and Markus, V. H. (eds.). (2018). “Processing the paradox: when the state has to deal with customary law” in The state and the paradox of customary law in Africa (New York: Routledge), 1–40.

Organisation of African Unity (OAU). (1981). African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. Adopted 27 June 1981, entered into force 21 October 1986. Nairobi: OAU. Available at: https://au.int/en/treaties/african-charter-human-and-peoples-rights (Accessed June 25, 2025).

Osman, F. (2024). An examination of the recognition of communities and partnership agreements under South Africa’s traditional and Khoi-san leadership act. Afr. Hum. Rights Law J. 24, 609–631. doi: 10.17159/1996-2096/2024/v24n2a9

Ouzman, S. (2010). Flashes of brilliance: San rock paintings of Heaven’s Things. In: Seeing and knowing: understanding rock art with and without ethnography. (eds). G. Blundell, C. Chippindale, and S Ben. (Johannesburg: Wits University Press), 11–31.

Pillay, S. (2021). The problem of colonialism: assimilation, difference, and decolonial theory in Africa. Crit. Times 4, 389–416. doi: 10.1215/26410478-9355201

Republic of South Africa. (1998). Recognition of Customary Marriages Act 120 of 1998. Pretoria: Government Printer. Available at: https://www.justice.gov.za/legislation/acts/1998-120.pdf (Accessed October 2, 2025).

Rwigema, P. C. (2025). Impact of the Berlin conference (1884–1885) on EAC development: 140 years after the divide of Africa. Rev. Int. J. Polit. Sci. Public Admin. 6, 25–47. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/390299729

Shekeni, J. N. (2018). An exploration of statelessness in Namibia: The significance of legal citizenship. Doctoral dissertation, University of Namibia

Simpson, A. (2007). On ethnographic refusal: indigeneity, ‘voice’and colonial citizenship, Junctures: the journal for thematic dialogue, (9). Available at: https://junctures.org/index.php/junctures/article/view/66

Southern African Development Community. (2005). Protocol on the Facilitation of Movement of Persons. Southern African Development Community.

Taylor, J. J. (2012). Naming the land: San identity and community conservation in Namibia’s West Caprivi. Basler Afrika Bibliographien. 12.

UN General Assembly. (2007). United Nations declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples. UN Wash, 12, pp. 1–18.

Vengesai, P. (2024). The rights of women in unregistered customary marriages in Zimbabwe: Best practices from South Africa. Law Democr. Dev. 28, 215–236.

Vranken, J. B. (2010). Methodology of legal doctrinal research. In Methodologies of legal research. Which kind of method for what kind of discipline (Hart Publishing), pp. 111–121.

Youkhana, E. (2015). A conceptual shift in studies of belonging and the politics of belonging. Soc. Inclus. 3, 10–24. doi: 10.17645/si.v3i4.150

Yuval-Davis, N. (2006). Belonging and the politics of belonging. Patterns Prejud. 40, 197–214. doi: 10.1080/00313220600769331

Keywords: indigenous identity, customary law, displaced belongings, post-colonialism, citizenship

Citation: Chawaremera MM (2025) Displaced belongings: indigenous identity, customary law and the struggles for recognition in post-colonial migration systems. Front. Hum. Dyn. 7:1655777. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2025.1655777

Edited by:

Valery Buinwi Ferim, University of Fort Hare, South AfricaReviewed by:

Joao Carlos Jarochinski Silva, Universidade Federal de Roraima, BrazilOlanike S. Adelakun, Lead City University, Nigeria

Copyright © 2025 Chawaremera. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Melisa M. Chawaremera, bWVsY2hhd2F6QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Melisa M. Chawaremera

Melisa M. Chawaremera