- Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa

This paper presents research conducted in an informal settlement in Paarl, Western Cape (South Africa). The research demonstrates the importance of team sport activities as an instrument to encourage community cohesion. It does this by demonstrating how sport facilities are planned for and provided in low income communities, and what the challenges are with regards to the provision, accessibility and maintenance of such facilities. A mixed methods approach consisting of policy analysis, spatial analysis, focus group discussions and semi structured interviews formed the basis of the research methodology. The results indicate that while policies exist to provide for sport and recreation in lower income communities, financial, institutional and logistical challenges cause these facilities to fall short in terms of communities’ requirements. However, the importance of sport both as participants and spectators have been recognised by community members themselves, consequently leading to the utilisation of informal spaces as community-driven informal sport venues.

1 Introduction

The abolishment of historical segregationist legislation and its subsequent impact on the urban landscape in South Africa have been widely documented. Urban poverty and inequality increasing since the country’s democratic regime change in 1994 have directly translated into poor quality of life for marginalised and vulnerable communities. According to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal number three-good health and well-being-74% of deaths in 2019 were caused by non-communicable diseases specifically those related to cardiovascular and diabetes. In addition to physical health challenges, the significant rise in anxiety and depression towards the later stages of the Covid-19 pandemic (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2022) are contributing to mental health challenges among South African citizens as well.

The National Development Plan of South Africa states its goal to reduce the prevalence of non-communicable chronic diseases by 28%. Promoting health through sport practices offers the potential to contribute to a healthier lifestyle. Not only does it promote physical health but also social, mental and community health, as well as social cohesion (Geidne and Van Hoye, 2021).

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many sport facilities were temporarily closed leaving participants unable to practice. This limitation on sport practices has been to the detriment of both mental and physical health. The effects thereof are still visible and reinforces the need for well-managed sport facilities (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2022). At-home gyms have been an alternative for many individuals; however, in lower-income communities where families are often confined to small and shared residential spaces, individuals wanting to practice sport are limited to community facilities (Fortuin, 2021).

This paper presents research conducted in an informal settlement in Paarl, Western Cape (South Africa). The settlement is colloquially referred to as “Chicago” by the local residents, and its location is demonstrated in Figure 1. The research demonstrates the importance of team sport activities as an instrument to encourage community cohesion. It does this by demonstrating how sport facilities are planned for and provided in low income communities, and what the challenges are with regards to the provision, accessibility and maintenance of such facilities. The research concludes that while policies exist to provide for sport and recreation in lower income communities, financial, institutional and logistical challenges cause these facilities to fall short in terms of communities’ requirements. However, the importance of sport both as participants and spectators have been recognised by community members themselves, consequently leading to the utilisation of informal spaces as community-driven informal sport venues.

2 Theoretical points of departure

Community sport activities in the form of organised sport activities like rugby, cricket and netball are low in resource use and can be financially accessible for most income groups. By creating community-organised sport experiences, community members can meet like-minded people in a safe environment while compensating for their limited access to household space. These initiatives have been practised worldwide and have been continuously promoted as part of the Millennium Development Goals. Sport for development as stated by Van der Veken et al. (2020) has been implemented in many places due to its power to address discrimination, bridge social divides, heal psychological wounds and encourage respect.

2.1 Communities and sport

Community-driven sport facilities and activities are examples of affordable alternatives to formalised sport clubs and organisations (Doherty et al., 2014; Theeboom et al., 2010). This is a bottom-up approach that is organised by members of communities themselves, aiming to narrow the gap between those that are not able to participate and those that do so formally. It also aims to address a range of cultural, social and political inequalities and challenges experienced within these communities (Schaillée et al., 2019; Theeboom et al., 2010).

The way individuals experience their living environment and neighbourhood are influenced by a number of factors; Whether they experience a sense of community, whether a community can work towards a common goal and to what extent a community poses agency to make decisions in their neighbourhood. These factors are difficult to measure since its results are based on subjective perceptions (Baum et al., 2009; Erin et al., 2012).

According to Rollero and De Piccoli (2010) there is a clear relationship between a person’s place of residence and their mental and physical health. Wilson et al. (2004) acknowledges that the concept of place attachment is the most fundamental understanding of psychology in space. The attachment to place is complex as it incorporates many different emotions and beliefs, while also examining different aspects of people and places in one space (Brown et al., 2003; Hernández et al., 2007). Wen et al. (2006) states that the neighbourhood environment can heavily influence an individual’s health, with Parkes and Kearns (2006) reiterating this in stating that a neighbourhood and the community has a multidimensional impact on people’s health. Therefore, the sense of place as well as the belonging in the community are contributing factors when an individual’s health is considered.

According to empirical evidence explored by Farrell et al. (2004), a number of health problems can be correlated with a lack of sense of community. The research indicated that there is a correlation between sense of community and neighbourhood stability as well as community health. The study indicated that members of a community that felt part of a group and shared an emotional connection handled emotional stress better while also having better overall health. These findings suggests that a stable community promotes positive relations between members of the community and their neighbours, therefore leading to the individual achieving an increase in personal well-being.

The approach taken by Farrell et al. (2004) is multi-dimensional, examining a wide range of influences to evaluate the impact they have on different health outcomes. One of the main results indicated that social disorganisation was most strongly related to poorer health. The amount of sport and leisure facilities provided did not directly correlate to a healthier community, however a lack of maintenance and poor services of the community did have a negative effect on the health of the community. Therefore, “place” does have an important role to play at different spatial scales (Lindstrom et al., 2001).

The links that exist between neighbourhood factors and the health of the individual and community will vary among different communities as certain neighbourhoods are more dependent on their community for their daily existence. People living in lower income neighbourhoods for example will rely more heavily on communal open spaces and fellow community members, while also being more vulnerable to their neighbourhood conditions and services (Boardman et al., 2001; Gordon et al., 2003; Kobetz et al., 2003). This is a result of smaller living spaces, limited household space and social dependence for daily living like child minding, frail care and transport.

An extensive study conducted by the National Research Council and Institute of Medicine (2013) states that health is largely shaped by social factors, i.e., factors that individuals experience throughout their entire lives, not just immediate factors. The disadvantages that individuals experience due to difficult living conditions can last and accumulate over generations, making it difficult to overcome and break a cycle of continued poverty (Case and Paxson, 2011; Goodman et al., 2014).

Community cohesion is established when members of a specific neighbourhood share common goals, challenges and experiences. Due to social interaction, a sense of self is developed, leading to normative behaviour which in return gives the individual a sense of purpose and building their identity. Sport takes on the role as one of the main facilitators in creating a sense of community and a sense of self (Skinner et al., 2008).

Through participation in sport (either through playing or spectating) a non-tangible benefit is created in the form of community belonging as well as identity. Sport has physical benefits, but in addition adds to an individual and a community’s life, through aspects such as unity, improved self-esteem and social inclusion (Skinner et al., 2008).

Research by Tonts (2005) adds to this sentiment in stating that sport contributes to the cultural, local and economic relations of smaller towns and regions. Through sport these towns have been building relations among the community members, which add to their identity and sense of belonging. As sport is played and enjoyed by a diverse group of people, many new friendships and associations form. Atherley (2006) reiterates this in stating that sport acts as a gateway between diverse groups to create lasting connections and social networks.

In essence, research concerning sport in communities suggest that the success of achieving social capital in communities are directly linked to the physical, environmental and social quality of life in the neighbourhood. A community with a high level of social capital therefore has a high quality physical environment and social cohesion. To foster a strong sense of social capital, the community must have a sense of belonging, civic engagement, and a strong sense of community (Kozma et al., 2016). Participation and involvement in sport clubs can help to strengthen these social mechanisms, leading to an increase in social capital. Additionally, involvement in sport clubs can boost self-confidence and self-worth, while also allowing individuals to create more positive identities. This is important in mitigating self-stigmatisation, which can lead to the decline of urban neighbourhoods and communities.

2.2 Sport infrastructure and events

A large body of literature (Coalter, 2007a; Davies, 2012; Jamieson, 2014; Levermore, 2008; Pigeassou, 2004; Thornley, 2002) exists on the benefits and importance of large sporting events such as the Olympic games and sport tourism like football leagues in Europe. While mass sporting events are engaging for a large part of a community, an increase and continuation of active sport participation has the most significant social capital gains (Davies, 2016). According to Skinner et al. (2008) the intention is to provide sport development that acts as a gateway to participation. Many community members do not physically participate in sport but are active spectators.

Sport facilities must be strategically placed and consideration given to serving of a broad community. “The success of many of the interventions piloted by the cultural and sport programs highlights the importance of ensuring that services are geographically and culturally accessible to all local residents, as well as being embedded within community venues and settings that provide ownership of the programs by those involved in them” (Skinner et al., 2008: 20).

This form of revitalisation and social capital building has been implemented in many cities, one of these examples is the Energa Arena in Gdansk, Poland. Due to the UEFA EURO 2012 football championship, Poland made massive public investments to cater for this large-scale event. Although the initial purpose was to provide for the event, the spillover effect therefore benefitted the larger community. Although this was a larger national scale project, the local effects led to revitalisation to those that needed it the most. The aim of the project was to serve tourists for the UEFA EURO football championship; however, it resulted in community upliftment and regeneration (see Taraszkiewicz and Nyka, 2017).

According to Coalter (2007b) and Taylor et al. (2015) sport-related regeneration projects have the potential to generate various intermediate and final outcomes, affecting both individuals and the community. For instance, engaging in sport activities may lead to increased self-esteem and self-efficacy for an individual, which can subsequently result in enhanced pro-social behaviour and reduced crime rates within the community. Furthermore, certain final outcomes in one area, such as reduced anti-social behaviour and increased prosocial behaviour, may act as intermediate outcomes for final outcomes in other areas, such as improved educational attainment. While these outcomes are not explicitly demonstrated in the current context, they can still occur as part of the larger framework of sport-related regeneration projects.

2.3 Community sport in South Africa

Concern over local government in South Africa’s operational efficiency to adequately deliver hard and soft infrastructure to local communities have been expressed in literature and policy. This concern mainly emanates from the country’s segregated past, and the subsequent efforts to achieve meaningful integration and equal distribution. Policymakers responded with a range of measures aimed to change the social and infrastructural fabric of the urban centres, many of which have been unsuccessful (van der Westhuizen and Dollery, 2009). The provision of sport and recreational facilities, according to schedule 5 of the Constitution of South Africa, falls within the mandate of local government. Given the institutional and fiscal difficulties facing local authorities in South Africa, more affordable alternatives are more likely to be implemented in settlements.

In South Africa, the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) published guidelines for the provision of social facilities in South African settlements that seek to provide a rational framework for the provision and distribution of social facilities and support the planning process for future settlements. An important rationale for the guidelines is to ensure equitable distribution of facilities between lower and higher urban income areas (Green and Argue, 2014).

Against a backdrop of eroded communities and poverty, The National Department of Sport and Recreation for South Africa implemented mass participation programs. The primary agenda of these programs were to operate in impoverished areas at school level. The aim was to address and mitigate against a range of manifestations of poverty such as teenage pregnancies, deviance and poor literacy rates. Benefits identified by Burnett and Hollander (2008) included “new” sport being introduced to rural schools, leading to an increase in participation. Other activities such as festivals and inter-class competitions also stimulated a healthy drive for competition and created a sporting culture. Despite the good uptake of participants, there were still institutional challenges such as a lack of maintenance, poor resources supplied and limited availability of coaches, assistants or volunteers.

Another program yielding more positive results was the Active Community Clubs Initiative, initiated by the Australian Agency for International Development. The program was launched at two different schools, one in the Eastern Cape Province, another in KwaZulu-Natal Province. Two of the main components of their success was that they had an outside-in and bottom-up approach, they sought out partnerships with local stakeholders while also including the general community to buy into the program through volunteering. The aim of including the community is to eventually transfer the program to the community once it is well established and can function independently (Burnett and Hollander, 2008).

According to Burnett (2010) the Active Community Clubs Initiative achieved success due to their mobilisation of local partners and volunteering. This “active citizenship” approach ensured mutual ground was found, while also making a real impact. This was especially true under the younger children, due to the volunteers being well known and trusted community members. This also enhanced local ownership and buy-in from parents and community leaders aiding in the mitigation of prominent social issues.

A case study conducted by Denoon-Stevens and Ramaila (2018) demonstrates that the construction of a multifunctional sport and recreation centre provided many benefits and improvements to an informal settlement in Limpopo Province, South Africa. The respondents of the area reiterated the improvement of safety, security, health and a strengthening of social capital after construction.

Studies conducted by Brangan (2012), Denoon-Stevens (2007), and Gcobo (1998) point out that sport facilities should not only be provided as a single entity, but rather clustered with social support services to ensure optimal accessibility to a range of services. To demonstrate, public open spaces such as parks are still considered dangerous, especially in low-income areas in South Africa. Providing libraries is one interventionist method to support a community and make the area safer. Therefore, the clustering of sport facilities with libraries can be much more beneficial to a community’s general safety, cohesion and learning potential.

The Mahwelereng Sport Node and Library (MSNL) was built in 2010 in Limpopo Province after a vacant field that was used as an illegal dumpsite got rehabilitated and used as the site for the MSNL. The facility accommodates a range of activities, from sport, educational, recreational, and cultural amenities. The result is a mixed-use development that does not only cater for school sport or educational activities, but rather both young and older people in the community.

Respondents in the study praised the facility as it was safe, well designed, functional, and providing a well-maintained space for social interaction between all age groups. Although the costs and operation of the facility is provided by the government, the community is very much involved in the process of facilitating new initiatives, keeping the sport teams active, running the library and providing educational programs (Denoon-Stevens and Ramaila, 2018).

3 Methodology

“Chicago” informal settlement is located in Paarl, a town situated in the Drakenstein Municipality, Western Cape Province, South Africa (Figure 1).

Paarl is the main economic hub of the municipal area, while also functioning as an important regional centre for the greater Cape Town Metropolitan area. Paarl is situated next to the N1 highway which connects the north and south of South Africa. Therefore, Paarl is an important secondary city servicing an extended area of the Western Cape and beyond.

“Chicago” (Figure 1) is a small community situated within Paarl East and has between six and seven thousand residents. “Chicago” is surrounded by the suburbs of Charleston Hill, Klippiesdal, Rabiesdale and Klein Nederburg. The study area comprises a largely low-income community with a poor socio-economic status. According to the 2011 National Census, the population was 6,722 (Statistics South Africa, 2012). Sport is a large part of their community, with teams consisting of all age categories. The main sports are cricket, netball, rugby and football as well as modern and traditional dancing.

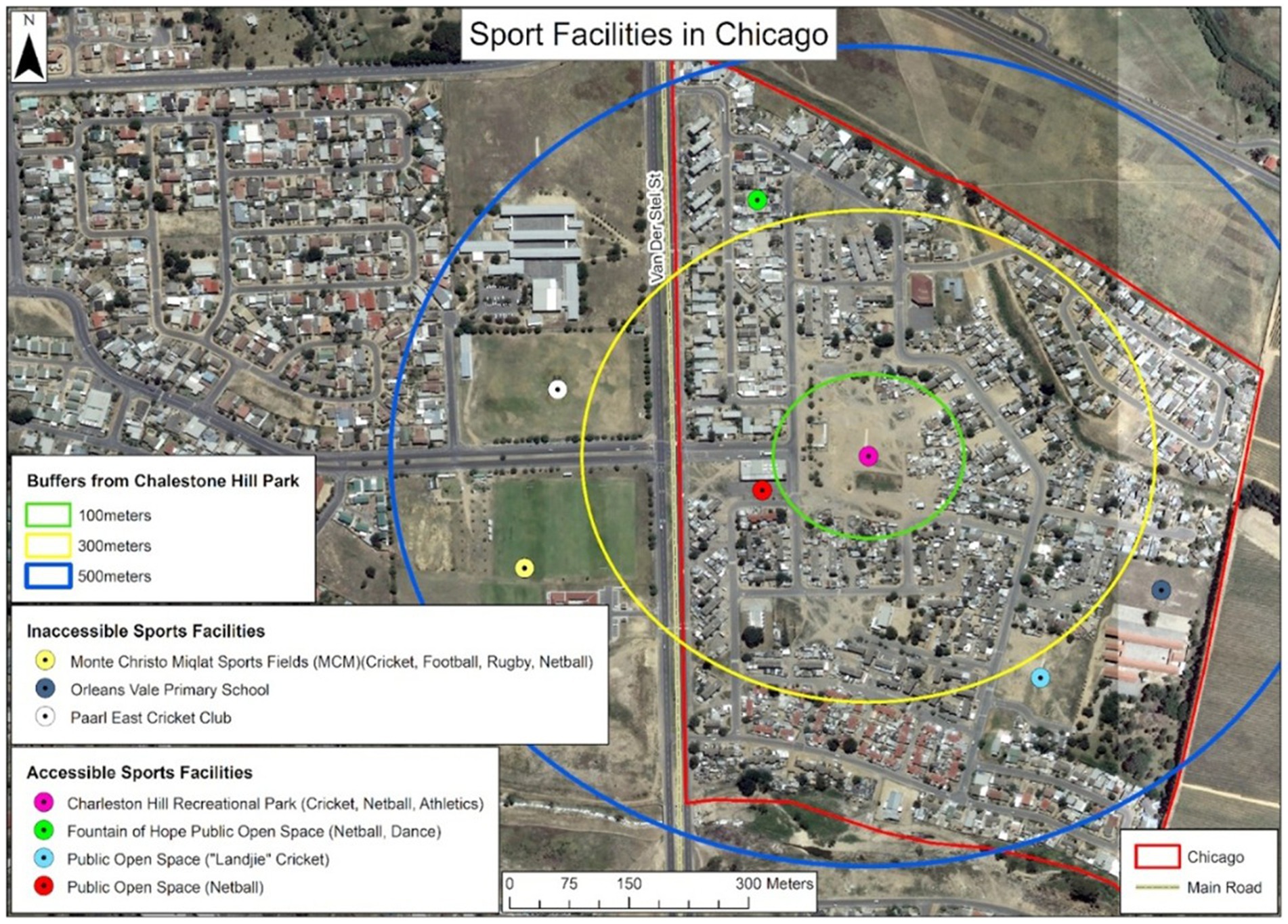

One of the main objectives of the study was to understand the spatial distribution of state-provided and community-driven sport facilities. To achieve this, GIS software such as Esri ArcMap was used as the main mapping tool, alongside Google Earth Pro, Google Maps, and Cape Farm Mapper (A product of the Western Cape Department of Agriculture). These tools were used to map the formal and informal spaces used for sport activities within a 500 m radius of “Chicago.”

A critical component of the research was the researchers formalisation with Ranyaka Community Transformation. A research partnership was established with Ranayaka Community Transformation,1 who had a pre-established project-based relationship with the community in “Chicago.” This organisation had been working in and with the members of the “Chicago” community in the 12 months prior to the researcher’s investigation. The researcher approached the organisation, and from discussions and clarification of specific objectives, was able to identify the appropriate role players and stakeholders in the community with whom discussions pertaining to the specific study would be prudent. Therefore, the researcher employed a purposive sampling approach in identifying research participants. From this approach, 16 individuals were identified based on their involvement with sport and community activities in “Chicago.” These individuals were coaches, sport managers, non-profit organisation leaders or active participants in community sports.

One formal group discussion took place with this focus group of 16 individuals, followed by a second session with smaller splinters of the group in semi-structured interview format. These engagements were followed by a Likert scale questionnaire completed by the individuals. This approach was taken to capture their opinions and attitude towards the management of sport, the role of the municipality and to capture their most pressing concerns. The processing of the questionnaires was done using Microsoft Excel, due to the Likert scale system, simple averages could be calculated, to capture the consensus of the group.

Engagements with the local community in “Chicago” was undertaken to understand the research problem from a “user” point of view. These engagements however needed to be balanced by the “provider” perspective, and therefore community engagements were followed by one semi-structured interview with a member of the CSIR to disseminate the Guidelines for Human Settlements Planning and Design (Red Book) and the thought process behind it. This was supplemented by a desktop study of municipal spatial planning documents in order to understand the planning and provision of sport and recreational facilities in Paarl and “Chicago” specifically.

4 Results

The results emanating from the mapping exercise, focus group discussions, questionnaire, semi-structured interview and desktop analysis are synthesized in this section as a summary of the current nature of informal sport practices in “Chicago.”

4.1 Overview

Criminal and antisocial behaviour is most prevalent between the ages of 16 and 18, therefore the role of sport participation is seen as a large influence in countering this behaviour. Participants of the group discussions elevated gangsterism as one of the largest issues faced by the “Chicago” area, in addition to widespread drug use. The coaches and managers of the different sport teams unanimously vouched for the influence and impact that sport coaching has made on the children and teenagers in terms of keeping them away from gangs and drugs. Due to the prevalence of alcohol and drug addiction among parents, the sport teams additionally act as a safe haven for many children. As coaches and managers go beyond what is expected and act as mentors, they educate the youth on societal issues prevalent in their community. Keeping children occupied in the afternoons and at night helps to solidify a healthy foundation, ensuring they are not occupied with delinquent behaviour like drugs or vandalism. As stated by a participant: “A child in sport is a child out of court.” These narratives are in agreement with literature findings pointing to community sport as an instrument for increased social cohesion and quality of life.

The role of sport also helps the children to protect and care for the sport facilities they use, leading to less vandalism, theft and an increased sense of ownership and responsibility.

Team coaches and managers foster good values and morals in sport teams and over time some of the children become mentors and coaches in the community as well, thereby continuing a cycle of upliftment through community sport volunteerism. The conduct of sport, i.e., being a gentleman, being respectful and being a good sport person is constantly repeated to instil good values and create a sense of self-worth. This leads to players being respectful towards their fellow players as well as their community members leading to social cohesion, humility, and a sense of belonging.

From an institutional point of view, an interview with the official from the Drakenstein Municipality’s Department of Sport and Recreation shed light on the formal management and delivery of sport facilities to the community of “Chicago.” In terms of sport, the managing thereof and the provision of sport fields and facilities, three departments are involved namely the Spatial Planning Department, the Parks and Open Spaces Division and the Sport and Recreation Division. The provision of sport facilities and fields are one of the main concerns for the Sport and Recreation Department, therefore allocating the appropriate space to accommodate this is needed. The Sport and Recreation Division are responsible to identify the sporting needs present within the municipality. This is an ongoing process which is summarised through the Key Performance Areas and Pre-Determined Objectives present within the Integrated Development Plan (IDP). The Spatial Planning Department is responsible for the planning of the built infrastructure in terms of sport facilities and fields. The department will also conduct appropriate research and work in terms of site selection, site suitability, feasibility studies and small-scale regeneration projects.

4.2 Evaluation of current sport facilities

By far the most prominent sport informally practised by “Chicago” residents is cricket. Cricket is one of the most prominent sport being played in Paarl, from mini-cricket to club cricket, “landjie”2 cricket and professional cricket. The construction of Boland Park, a multi-purpose and International Cricket Council-accredited stadium reiterates the large-scale presence of the sport in the area (Fortuin, 2021).

Cricket in “Chicago” has been shaped by the community, the facilities and the schools, which has led to an informal cricket structure. This form of cricket uses a tennis ball wrapped in white electrical tape with an added black electrical tape seam, essentially mimicking a real cricket ball with its leather seam. This form of cricket has been widely practised on the streets of Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and also South Africa (Samiuddin, 2015). In some areas, it is referred to as tennis ball cricket or tape ball cricket. “Chicago” has between 20 and 24 teams, ranging from young children to adults. The large number of participants is attributed to community leaders and coaches trying to keep children away from drugs and gangsterism while promoting social cohesion and self-respect. This sentiment is also reiterated by the results of the questionnaire, where all respondents “strongly agree” that they believe that sport help to build community cohesion.

Netball is a mainly female sport within “Chicago” but is enjoyed by all, through friendly matches, tournaments and official matches. Netball is practised in streets, parking lots, courts and other flat concrete areas where makeshift lines are used. Although netball at schools is played formally, the community has a more informal approach due to their circumstances, however, they aim to keep the game as true to the rules as possible.

In addition to these two sport, Rugby, Dancing and Football are also practised and played by “Chicago” residents both informally and formally between neighbouring communities and at school level.

Funding for the informal sport teams comes from fundraising through selling food at sport days or asking the parents to donate small amounts to aid the sporting activities. On rare occasions, donations have been made from private companies, individuals and non-profit organisations. The coaches and managers of the respective teams are the largest funders, contributing their own money into keeping the teams functional.

Funding does not only have to cover jerseys, travel costs and equipment but in many cases the goal posts, goal boxes, wickets and nets. The state of the facilities has led to the coaches having to provide equipment for the fields and courts, leading to a poor playing experience.

A lack of cooperation from the municipality and its representatives are cited as a concern by all focus group participants. Alongside their lack of cooperation, the schools in the area also do not want to partner with the teams due to a general lack of trust and safety for their property. The informal structure of the teams has led to a dead-end in terms of cooperation and compliance, there is no need or necessity from the municipality’s side to build a relationship with the different sporting groups. As one respondent has stated with reference to the schools in the area: “… they are selfish, and they want to protect their island.” Concern over the condition of the school facilities from the headmaster and the board’s side is not without reason. They do not want to create a precedent that could potentially lead to a range of other issues. However, efforts being made by the sporting “clubs” to reach out for information, cooperation and discussion, are being rejected or ignored.

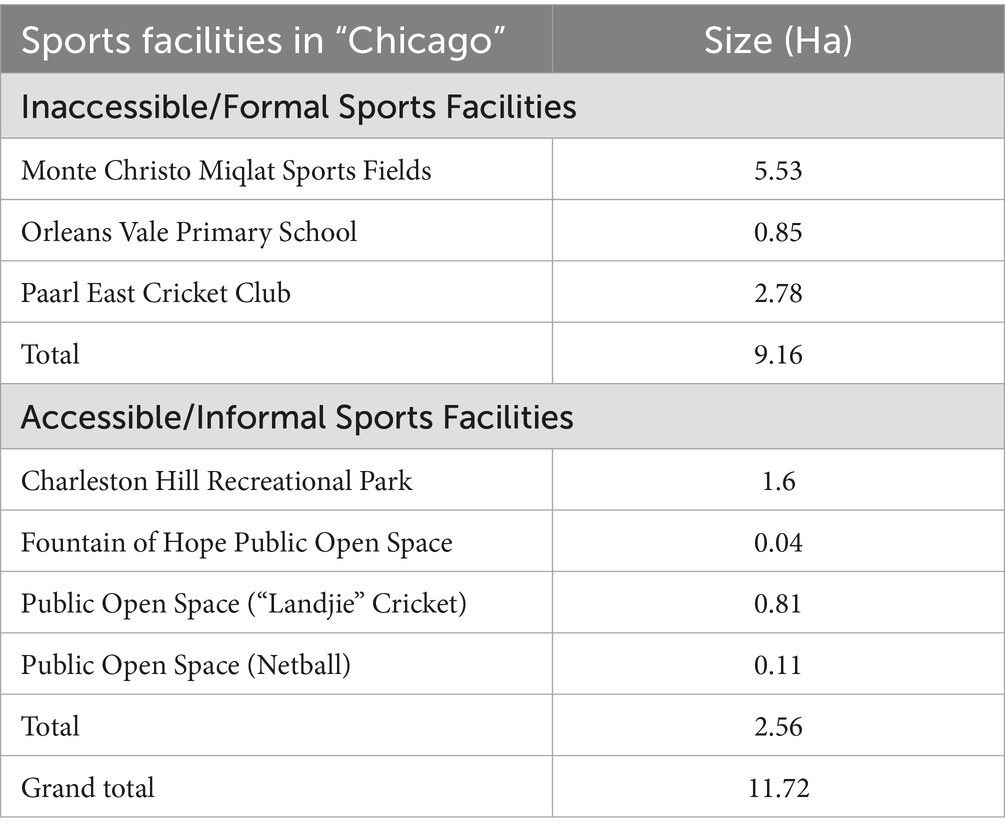

According to the census data of 2011,3 the population of “Chicago” is 6,722 people. Considering outdated data, taking the yearly increase in the population from 2011 until 2022 of South Africa into account, the population is estimated at 7,738. As stated by the CSIR guidelines, 0.56 Ha per 1,000 citizens is adequate for the use of sporting activities. Therefore, 4.33 Ha is what the guidelines are suggesting is the adequate amount necessary to accommodate the population of “Chicago.”

Table 1 indicates the accessible and inaccessible facilities, the size of the facilities and the totals. As indicated, the accessible facilities are less than the adequate amount suggested by the CSIR, however, including the inaccessible facilities, the provision would be far more than the minimum.

Figure 2 indicates the spatial distribution of the sport facilities and their accessibility to residents in “Chicago,” the proximity of each facility in relation to another, as well as the residential areas surrounding each facility. The buffers act as a guide and estimation in terms of walkability and estimated travel time. Each accessible facility has been visited and the focus group were asked to point out the issues and challenges with each facility. According to the questionnaire, an overwhelming majority of respondents are willing to walk more than 2 km to use a sport facility.

The open space area marked for “Landjie Cricket” is situated close to the Orleans Vale Primary School, consisting of a concrete cricket pitch in the centre. This public open space is used for cricket, although there is no grass, there are just patches of weeds present, and cricket is played here very frequently. As with Charleston Recreational Park, there are no spectator stands, lights, bathrooms, changing rooms or other amenities. The “field” does not have a demarcated border as needed for cricket, and the concrete pitch has been constructed to ensure longevity, it is however full of holes and needs to be levelled. This parcel of land does not have any form of fencing and is completely open, safety is therefore another concern at this facility. Whether people feel safe using their sport facilities, according to the questionnaire, is disagreed upon overwhelmingly. This supports the notion that proper safety measures are needed at the facilities (Figure 3).

The open space used for netball is not an official sport facility but rather an abandoned parking lot which has been converted into two netball courts. One is slightly larger, used by adults and older children and the other, which is smaller in size, is used by younger children. The coaches from the community bring their own netball poles and nets when they use these courts. They have painted lines on the tar parking lot to demarcate the two courts. Both courts are uneven and littered with small cracks and holes, making for a suboptimal playing space (Figure 4).

Due to the informal nature of the courts, there are no bathrooms, spectator stands, changing rooms, a source of light or any other amenities, it is, therefore, two makeshift courts in its most basic form. General debris like glass and litter are common around and on the courts. According to one of the respondents, this needs to be cleaned by them on a regular basis in order to make the courts usable.

4.3 Observations

The main concern of the coaches and team managers was the lack of proper training concerning umpires. Due to the more informal nature of cricket in “Chicago” and the low socio-economic status of the community, official umpires cannot be acquired due to a lack of funds. Therefore, other community members, coaches or lovers of the sport have to umpire for the matches or tournaments. This often leads to disagreements on the field and a prolonged match day.

Despite the physical conditions of sport facilities for participants and spectators the community buy-in and importance of sporting events cannot be overstated. All respondents in the questionnaires, interviews and focus groups reiterated especially the cricket games as a Sunday ritual in the “Chicago” community. Families would first attend a church service after which they will attend the informal cricket matches for the entire day. It is considered that these events not only make for social engagements, but serves as an activity that prevents families from isolating themselves, child neglect and alcohol abuse. The recurring Sunday tradition of spectators and participants in Landjie Cricket on a vacant portion of land in “Chicago” also reiterates the strong suggestion by other researchers that a communal goal/interest fosters cohesion.

The limited financial and organisation capacity cited by the local authority (by words of the official from the Department of Sport and Recreation) comes forward as one of the main challenges in sport practices receiving support from the municipality as a community cohesion instrument. The responsibility of managing, maintaining, and doing upgrades to sport facilities and fields are placed upon the Sport and Recreation Department. This is the norm for all facilities that are operated by the municipality themselves, however certain facilities are leased to private groups, clubs, or companies. In terms of leased facilities, the managing and maintenance fall upon the tenants.

While open spaces, parks and fields are used for sporting activity informally, it is therefore the responsibility of the Parks and Open Spaces Division at Drakenstein Municipality to manage and maintain these spaces. The current level of and spending on management is minimal due to the list of priorities present within the management of the municipality; hence sport and other recreational activities will rarely be tended to by the parks and open spaces division. This is mainly due to budgetary constraints, and the misalignment of their main functions, which is to maintain parks and open spaces, not sporting activities.

5 Conclusion

The benefits of community sport have been demonstrated by many literary sources and case studies worldwide to such an extent that it also underpins one of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. While policies in South Africa exist to encourage the trickle down of this goal into local areas, financial, logistical and institutional realities complicate the adequate provision and maintenance of community sport facilities. Lower income communities, such as the “Chicago” informal area in the Western Cape, South Africa, have recognised community organised sport as a tool towards encouraging community cohesion, in addition to mitigating community social challenges, e.g., alcohol dependence, drug abuse, teenage pregnancies and school dropouts. In the absence of formal spaces where communities can practice their informal organised sporting club events, communities utilise and construct their own sporting venues in informal spaces, that becomes beacons of social cohesion and community support.

This case study supports the limited available literature on sport as potential vehicle for community upliftment and cohesion in South African neighbourhoods. The research findings demonstrated that, where sport activities are actively involving community members as both participants and spectators, benefits to the community have been witnessed. While these benefits are currently noticeable as fewer young people participating in gangsterism, drugs, and generally receiving better education and exposure to good moral values, over time these benefits may become visible in analyses of school dropout rates and other tangible indicators.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Stellenbosch University Department of Ethics for Social Sciences. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

AH: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Supervision. WM: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Ranyaka Community Transformation is a non-profit organisation established in 2013, with the aim of providing a positive socio-economic impact to communities in need. Their approach is place-based with a large focus on collaboration between all the relevant stakeholders present within a community.

2. ^A colloquial term referring to informal cricket played on any vacant piece of land or open field in a neighbourhood.

3. ^Latest official census data in South Africa at time of publication.

References

Atherley, K. M. (2006). Sport, localism and social capital in rural Western Australia. Geogr. Res. 44, 348–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-5871.2006.00406.x

Baum, F. E., Ziersch, A. M., Zhang, G., and Osborne, K. (2009). Do perceived neighbourhood cohesion and safety contribute to neighbourhood differences in health? Health Place 15, 925–934. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.02.013

Boardman, J. D., Finch, B. K., Ellison, C. G., Williams, D. R., and Jackson, J. S. (2001). Neighborhood disadvantage, stress, and drug use among adults. J. Health Soc. Behav. 42, 151–165. doi: 10.2307/3090175

Brangan, E. (2012). “Physical activity, noncommunicable disease, and wellbeing in urban South Africa” in Doctoral thesis (Bath: University of Bath).

Brown, B., Perkins, D. D., and Brown, G. (2003). Place attachment in a revitalizing neighborhood: individual and block levels of analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 23, 259–271. doi: 10.1016/S0272-4944(02)00117-2

Burnett, C. (2010). Sport-for-development approaches in the south African context: a case study analysis. S. Afr. J. Res. Sport Phys. Educ. 32, 29–42. doi: 10.4314/sajrs.v32i1.54088

Burnett, C., and Hollander, W. J. (2008). “Baseline study of the school sport mass participation programme” in Report prepared for SRSA (Johannesburg: Department of Sport and Movement Studies, University of Johannesburg).

Case, A., and Paxson, C. (2011). The long reach of childhood health and circumstance: evidence from the Whitehall II study. Econ. J. 121, F183–F204. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0297.2011.02447.x

Coalter, F. (2007b). Sports Clubs, Social Capital and Social Regeneration: ‘ill-defined interventions with hard to follow outcomes’? Sport in society, 10, 537–559.

Davies, L. E. (2012). Beyond the games: regeneration legacies and London 2012. Leis. Stud. 31, 309–337. doi: 10.1080/02614367.2011.649779

Davies, L. E. (2016). A wider role for sport: community sports hubs and urban regeneration. Sport Soc. 19, 1537–1555. doi: 10.1080/17430437.2016.1159192

Denoon-Stevens, S. P. (2007). Towards communities, beyond settlements: Failing to take account of practice in Delft south community hall. Cape Town: University of Cape Town.

Denoon-Stevens, S. P., and Ramaila, E. (2018). Community facilities in previously disadvantaged areas of South Africa. Dev. South. Afr. 35, 432–449. doi: 10.1080/0376835X.2018.1456906

Doherty, A., Misener, K., and Cuskelly, G. (2014). Toward a multidimensional framework of capacity in community sport clubs. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 43, 124S–142S. doi: 10.1177/0899764013509892

Erin, M. H., Shepherd, D., Welch, D., Dirks, K. N., and Mcbride, D. (2012). Perceptions of neighborhood problems and health-related quality of life. J. Community Psychol. 40, 814–827. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21490

Farrell, S. J., Aubry, T., and Coulombe, D. (2004). Neighborhoods and neighbors: do they contribute to personal well-being? J. Community Psychol. 32, 9–25. doi: 10.1002/jcop.10082

Fortuin, J. (2021). The spatial distribution of cricket in Drakenstein municipal area: alternative perspectives on urban informality and marginal urban space. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University.

Gcobo, R. (1998). The provision of recreation facilities for the youth in Umlazi township: A socio-spatial perspective. Kwadlangezwa: University of Zululand.

Geidne, S., and Van Hoye, A. (2021). Health promotion in sport, through sport, as an outcome of sport, or health-promoting sport—what is the difference? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:9045. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18179045

Goodman, R. A., Bunnell, R., and Posner, S. F. (2014). What is ‘community health’? Examining the meaning of an evolving field in public health. Prev. Med. 67, S58–S61. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.07.028

Gordon, R. A., Savage, C., Lahey, B. B., Goodman, S. H., Jensen, P. S., Rubio-Stipec, M., et al. (2003). Family and neighborhood income: additive and multiplicative associations with youths’ well-being. Soc. Sci. Res. 32, 191–219. doi: 10.1016/S0049-089X(02)00047-9

Green, C., and Argue, T. (2014). Summary guidelines and standards for the planning of City of Cape Town social facilities and recreational spaces. Cape Town.

Hernández, B., Carmen Hidalgo, M., Salazar-Laplace, M. E., and Hess, S. (2007). Place attachment and place identity in natives and non-natives. J. Environ. Psychol. 27, 310–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.06.003

Jamieson, N. (2014). Sport tourism events as community builders-how social capital helps the ‘locals’ cope. J. Conv. Event Tour. 15, 57–68. doi: 10.1080/15470148.2013.863719

Kobetz, E., Daniel, M., and Earp, J. A. (2003). Neighborhood poverty and self-reported health among low-income, rural women, 50 years and older. Health Place 9, 263–271. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(02)00058-8

Kozma, G., Pénzes, J., and Molnár, E. (2016). Spatial development of sports facilities in Hungarian cities of county rank. Bull. Geogr. Socio Econ. Ser. 31, 37–44. doi: 10.1515/bog-2016-0003

Levermore, R. (2008). Sport: a new engine of development? Prog. Dev. Stud. 2, 183–190. doi: 10.1177/146499340700800204

Lindstrom, M., Hanson, B. S., and Ostergren, P.-O. (2001). Socioeconomic differences in leisure-time physical activity: the role of social participation and social capital in shaping health related behaviour. Soc. Sci. Med. 52, 441–451. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00153-2

Parkes, A., and Kearns, A. (2006). The multi-dimensional neighbourhood and health: a cross-sectional analysis of the Scottish Household Survey, 2001. Health Place 12, 1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.03.004

Pigeassou, C. (2004). Contribution to the definition of sport tourism. J. Sport Tour. 9, 287–289. doi: 10.1080/1477508042000320205

Rollero, C., and De Piccoli, N. (2010). Does place attachment affect social well-being? Rev. Eur. Psychol. Appl. 60, 233–238. doi: 10.1016/j.erap.2010.05.001

Schaillée, H., Haudenhuyse, R., and Bradt, L. (2019). Community sport and social inclusion: international perspectives. Sport Soc. 22, 885–896. doi: 10.1080/17430437.2019.1565380

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2013). U.S. Health in International Perspective: Shorter lives, Poorer health eds. S. H. Woolf and L. Aron. The National Academic Press.

Skinner, J., Zakus, D. H., and Cowell, J. (2008). Development through sport: building social capital in disadvantaged communities. Sport Manage. Rev. 11, 253–275. doi: 10.1016/S1441-3523(08)70112-8

Taraszkiewicz, K., and Nyka, L. (2017). Role of sports facilities in the process of revitalization of brownfields. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 245:042063. doi: 10.1088/1757-899X/245/4/042063

Taylor, P., Davies, L., Wells, P., Gilbertson, J., and Tayleur, W. (2015). A review of the social impacts of culture and sport. Sheffield.

Theeboom, M., Haudenhuyse, R., and de Knop, P. (2010). Community sports development for socially deprived groups: a wider role for the commercial sports sector? A look at the Flemish situation. Sport Soc. 13, 1392–1410. doi: 10.1080/17430437.2010.510677

Thornley, A. (2002). Urban regeneration and sports stadia. Eur. Plan. Stud. 10, 813–818. doi: 10.1080/0965431022000013220

Tonts, M. (2005). Competitive sport and social capital in rural Australia. J. Rural. Stud. 21, 137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2005.03.001

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2022). The sustainable development goals report. doi: 10.18356/d3229fb0-en

Van der Veken, K., Lauwerier, E., and Willems, S. J. (2020). How community sport programs may improve the health of vulnerable population groups: a program theory. Int. J. Equity Health 19:74. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01177-5

van der Westhuizen, G., and Dollery, B. (2009). Efficiency measurement of basic service delivery at south African district and local municipalities. J. Transdiscipl. Res. South. Afr. 5, 162–174. doi: 10.4102/td.v5i2.133

Wen, M., Hawkley, L. C., and Cacioppo, J. T. (2006). Objective and perceived neighborhood environment, individual SES and psychosocial factors, and self-rated health: an analysis of older adults in Cook County, Illinois. Soc. Sci. Med. 63, 2575–2590. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.025

Keywords: informal sport, local government, social facilities, South Africa, community planning

Citation: Horn A and Marais W (2025) Informal sport spaces as beacons of social cohesion: a case study of informal sport in “Chicago,” Western Cape, South Africa. Front. Hum. Dyn. 7:1667279. doi: 10.3389/fhumd.2025.1667279

Edited by:

Jesús Rodrigo-Comino, University of Granada, SpainReviewed by:

Anthony Sholanke, Covenant University, NigeriaRuslaini Ruslaini, STIE Kasih Bangsa, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Horn and Marais. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anele Horn, YW5lbGUuYnJpdHpAZ21haWwuY29t

Anele Horn

Anele Horn Willis Marais

Willis Marais