- 1M.Sc. Public Health Entomology, Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR)-Vector Control Research Centre, Department of Health Research, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India (GOI), Medical Complex, Indira Nagar, Puducherry, India

- 2Division of Vector Biology and Control, Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR)-Vector Control Research Centre, Department of Health Research, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India (GOI), Medical Complex, Indira Nagar, Puducherry, India

- 3Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR)-Vector Control Research Centre, Department of Health Research, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India (GOI), Medical Complex, Indira Nagar, Puducherry, India

Introduction: Wolbachia-based vector control strategies have been successfully implemented as a sustainable long-term solution and a promising tool for controlling Aedes mosquitoes, primarily Ae. aegypti, the main vector of major arboviral diseases. Since it is essential to rear healthy and competent adult mosquitoes for mass release under Wolbachia-based vector control strategies, optimising larval diet is essential. Therefore, the current study tested and compared four different larval diets to examine their statistical significance on the Wolbachia transinfected and uninfected Ae. aegypti life table traits.

Methods: We tested and compared the effects of four larval diets: LD1 (fish feed), LD2 (laboratory rodent diet), LD3 (mushroom powder), and LD4 (dog biscuit plus brewer’s yeast) on hatchability, pupation, adult emergence, fecundity, and adult survival of Wolbachia-transinfected (wMel and wAlbB) Puducherry strains, as Among the tested diets, fish feed (LD1) and the combination of dog biscuit with brewer’s yeast (LD4) have significant effects in both Wolbachia-transinfected and uninfected Ae. aegypti strains regarding egg hatchability, pupation, adult emergence, fecundity, and adult survival.

Results: The highest fecundity was observed under LD1 for uninfected Ae. aegypti, with approximately 84 eggs/female (84.0 ± 6.0), followed by wMel (Pud) mosquitoes (~78 eggs/female, 78.0 ± 5.2) and uninfected mosquitoes (~75 eggs/female,74.6 ± 23.3) under LD4 diet in the F0 generation. The uninfected Ae. aegypti females exhibited significantly lower mortality risk under LD2 (Hazard Ratio (HR)=0.56<1, P<0.001), with a high median survival of 57 days compared to all other diets.

Discussion: The results of this study suggest that LD1 (fish feed) can be recommended as the superior larval diet for the mass rearing of Wolbachia-transinfected strains, although both LD1 and LD4 diets demonstrated positive effects on all the Ae. aegypti strains. Meanwhile, LD4 (dog biscuit + brewer’s yeast) can be recommended for the routine rearing of uninfected Ae. aegypti colonies, as it is comparatively cost-effective and readily available in India. These findings could contribute to the large-scale mosquito rearing programs under the Wolbachia strategy, ultimately supporting the implementation of sustainable vector control approaches for arboviral disease management.

1 Introduction

Aedes aegypti is the primary vector responsible for transmitting major arboviral diseases such as dengue and chikungunya, and it is targeted through several vector control strategies. In 2024, more than 7.6 million dengue cases have been reported worldwide, including 3.4 million confirmed cases and over 3,000 deaths (1). In India, 233,400 confirmed dengue cases and 236 deaths were reported during the same period, creating a significant public health concern that necessitates integrated approaches and effective preventive control strategies (2). Although the main prevention and control strategies for dengue have largely focused on suppressing Aedes populations, their effectiveness in reducing disease incidence and outbreaks remains limited in many endemic countries due to multiple factors.

Wolbachia is a gram-negative symbiotic bacterium that occurs naturally in around 60% of insect species and has been detected in 39.5% of the 147 mosquito species studied (3). The Wolbachia pipientis (wPip) strain was originally identified in Culex pipiens mosquitoes by Hertig and Wolbach in 1924. (4). Other mosquito species harboring Wolbachia include Culex quinquefasciatus, Aedes fluviatilis, and Aedes albopictus (5). At the same time, Wolbachia has been detected at low frequency and density in Ae. aegypti, this remains inconclusive (6). Wolbachia manipulates arthropod reproduction through four primary mechanisms: feminization of males, cytoplasmic incompatibility, selective male killing, and parthenogenesis. Additionally, Wolbachia interferes with arboviral replication by competing for cellular resources like cholesterol, pre-activating the mosquito immune system, triggering the phenol-oxidase pathway, and modulating miRNA-mediated immune cascades (7).

Certain Wolbachia strains impose fitness costs on their mosquito hosts, potentially affecting their establishment in wild populations. The highly pathogenic wMelPop strain markedly decreases egg viability, shortens adult lifespan, and lowers reproductive capacity, while such impacts are either milder or not observed in the wMel and wAlbB strains. Laboratory studies have demonstrated that trans-infection of Ae. aegypti with wMelPop, wMel, and wAlbB significantly reduce vector competence for dengue virus (8). In limited field trials, Wolbachia has been effectively introduced into local Ae. aegypti populations, where it has inhibited dengue virus replication (9). Ae. aegypti mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia can be employed for either population suppression or population replacement strategies, both of which exploit Cytoplasmic Incompatibility (CI) (10).

In the population replacement strategy, the infected females are advantaged over uninfected females because they successfully mate with both infected and uninfected males, while wild females are sterilized by the infected males. Therefore, the infection is expected to spread into the population gradually, leading to its replacement with a population incapable of transmitting viruses (11, 12). In contrast, population suppression involves releasing only Wolbachia-infected males, producing inviable offspring when mating with wild females. This method requires continuous releases to maintain suppression and is most effective in isolated or controlled environments where re-infestation can be minimized (13, 14). Suppression-based field trials have yielded significant reductions in dengue incidence in various regions, including French Polynesia (15), the USA (16), China (17), Singapore (13, 18), Mexico (19), and Brazil (20).

The population suppression strategy uses both Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) and Incompatible Insect Technique (IIT) in the field for dengue vector control. The SIT induces severe mutations in the male germ line, leading to defective and infertile sperm, while IIT represents only a conditional form of sterility since males remain fully fertile when mating with females harboring the same Wolbachia strain (21). IIT is a population suppression strategy based on exploiting CI that occurs when infected males mate with uninfected females or with females harboring a different and incompatible Wolbachia strain (9). Several field trials have demonstrated the potential of both SIT and IIT in reducing vector populations and dengue incidence in intervention areas (22 & 18, 20).

The implementation of Wolbachia-transinfected Ae. aegypti in field programs require the mass rearing of large numbers of healthy and competitive adults. The optimization of larval diet is a crucial component in mass-rearing programs, as proper nutrition enhances survival rates, developmental efficiency, flight capability, and mating competitiveness, ensuring uniform mosquito quality for release. Adult longevity, a component of vectorial capacity, is a proxy for vector competence (19, 23). Optimal larval development requires sufficient reserves of proteins, glycogen, amino acids, and fatty acids (24), and nutritional deficiencies may lead to higher immature mortality, weaker adults, and reduced reproductive success (25–27).

Previous studies evaluated different larval diets for their effect on Ae. aegypti fitness. In Mexico, protein-based diets such as tilapia fish food, bovine liver powder, and porcine meal positively affected Wolbachia-infected Ae. aegypti development (28). In Sri Lanka, dry fish powder combined with brewer’s yeast promoted better larval growth, higher fecundity, and increased male longevity compared to the International Atomic Energy Agency- (IAEA) recommended diet (29). Similarly, (21) reported that laboratory rodent diets improved adult body size and fecundity due to their higher carbohydrate content. Substituting animal proteins with plant proteins in larval diets has been shown to decrease hatchability, prolong larval development, and reduce reproductive rates (30). In collaboration with the World Mosquito Program at Monash University, Australia, the Indian Council of Medical Research-Vector Control Research Centre (ICMR-VCRC) developed two Wolbachia-infected Ae. aegypti strains native to Puducherry (referred to as Pud strains). This was achieved by backcrossing wild-type Puducherry males with Australian females carrying the wMel and wAlbB Wolbachia strains. These newly established strains were assessed for biological fitness, Wolbachia stability, and sensitivity to insecticides (31). The findings indicated that both wMel and wAlbB infections enhanced traits such as wing size, reproductive output, egg viability, and adult longevity when compared to the uninfected population.

Based on these findings, the present study was designed to evaluate the effects of various larval diets on the life table traits of Wolbachia-transinfected wMel (Pud) and wAlbB (Pud) strains compared to uninfected Ae. aegypti laboratory colonies. Therefore, this study compared the standard diet with alternative diets, including fish feed, laboratory rodent diet, and mushroom powder, to assess their impact on life table characteristics. It was hypothesized that these larval diets would significantly influence developmental and reproductive traits and could be optimized for mass rearing of Wolbachia-transinfected mosquitoes. The study evaluated these effects across two generations to assess how larval nutrition may influence adult traits and be inherited by progeny. Life table characteristics such as hatchability, pupation rate, adult emergence, adult Male-Female ratio, fecundity, and adult survival were assessed and compared across F0 and F1 generations.

2 Materials and methods

The study was conducted at the ICMR-VCRC, Puducherry, from May 2024 to August 2024. The effects of different larval diets, such as laboratory rodent diet, mushroom powder (Agaricus bisporus), fish feed (TetraBits), and a combination of dog biscuit with brewer’s yeast (3:2), were evaluated on Wolbachia transinfected Ae. aegypti (wMel (Pud) & wAlbB (Pud) strains) and laboratory-reared uninfected Ae. aegypti mosquitoes. Life table parameters such as hatchability, pupation rate, adult emergence, and adult survival were assessed for mosquitoes reared on each diet (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Experimental design for evaluating the effects of four larval diets on life table parameters in three Aedes aegypti strains: wAlbB (Pud), wMel (Pud), and Wolbachia-free (lab-reared, Puducherry strain). Each experimental group consisted of 100 larvae per replicate, with three replicates per treatment (n = 300 larvae per mosquito strain per diet).

2.1 Larval diets

Although recommended larval diets for mass rearing have been established based on previous research, the availability of easily accessible and cost-effective larval diets remains important in the Indian context. Therefore, four commercially available larval diets were selected for the present study: (1) Fish feed (Tetra, Germany), (2) Laboratory rodent diet (VRK Nutritional solutions, Pune, Maharashtra, India), (3) Mushroom powder (Transdelta Agro Products, Maharashtra, India) and (4) Dog biscuit (60%) with brewer’s yeast (40%) (in the ratio of 3:2). Additionally, fish feed has shown promising larval growth for Wolbachia-transinfected mosquito rearing at the ICMR-VCRC insectary.

Dog biscuits serve as an excellent source of proteins, animal fat, calcium, and vitamins (32), while brewer’s yeast contains high levels of proteins, starch, sugar, minerals, and vitamins (Supplementary Table S1). The mushroom powder, derived from 100% natural button mushroom (A. bisporus), offers an alternative plant-based protein source and contains both high proteins and carbohydrates, which are essential for energy storage, utilization, and larval growth (29, 30, 33).

For convenience, the diets were coded as follows: LD1 for fish feed (TetraBits), LD2 for laboratory rodent diet, LD3 for mushroom powder, and LD4 for dog biscuit with brewer’s yeast LD1 granules and LD2 pellets were dried and ground into powder form before being fed to the larvae. Each diet was stored in a separate clean container. The larval feeding dosage was assessed based on larval age, following the method described by Jeffrey Gutiérrez et al. (34), and food was provided on alternate days. All diet experiments were initiated simultaneously, with three replicates for each mosquito strain under each diet regimen (4 diets × 3 strains × 3 replicates). The trays were regularly monitored to assess water loss due to evaporation and larval food intake.

2.2 Laboratory colonization of the mosquitoes

First instar larvae of wMel (Pud) and wAlbB (Pud) strains of Ae. aegypti (Pud) and uninfected laboratory-reared Ae. aegypti were obtained from the routine cyclical colony maintained at ICMR-VCRC. The experimental design employed three biological replicates of 100 larvae (n=300) for each mosquito strain and diet regimen. This sample size meets WHO guidelines for insect bioassays, which recommend 25–100 individuals per experiment (35). First instar larvae were transferred within 24 hours of hatching to labeled enamel trays (45 cm L × 30 cm W × 5 cm H), each containing 3 L of water, following World Mosquito Program protocols (36). Mosquito colonies were maintained at 27 ± 2 °C temperature and 80 ± 10% Relative Humidity (RH) under a 12-hour photoperiod. All replicates containing pupae were transferred to Bugdorm cages (30cm × 30cm × 30 cm) for adult emergence. Adult mosquitoes were maintained at a 10% sucrose solution, and after five days, female mosquitoes received chicken blood meals using the wax pot-collagen membrane method (36). Three days post-blood feeding, oviposition cups (200 mL capacity) partially filled with tap water were introduced for two days. Egg-laid papers were collected on the third day, air-dried at ambient conditions (27 ± 1 °C temperature, 80 ± 10% RH), and stored in sealed containers with saturated potassium chloride solution. The identical rearing procedure was repeated for the F1 generation, maintaining the same experimental design.

2.3 Life table analysis

A life table is a dataset that describes mortality rates across various age groups within a population of organisms (37). The present study focused on life table traits such as hatchability, pupation rate, adult emergence rate, fecundity rate, and survivorship of Wolbachia-transinfected wAlbB (Pud) and wMel (Pud) strains of Ae. aegypti, in comparison to Wolbachia-free laboratory-reared Ae. aegypti mosquitoes. Developmental progression from eggs to larvae, larvae to pupae, and pupae to adults was observed daily and recorded for each larval diet group. The hatchability of the F0 generation was not considered in the analysis, as the study was initiated with first instar larvae. The first generation of adults was designated as the F0 generation, and the eggs they laid were considered the next generation. Therefore, the first instar larvae hatched from each generation were used to continue the subsequent generation experiment.

The pupation rate was defined as the proportion of larvae that successfully pupated, while hatchability referred to the percentage of eggs that hatched into larvae. Daily mortality was recorded for each developmental stage under each diet regimen. For fecundity, the total number of eggs laid in all oviposition cups was counted, and the average number of eggs laid per female per gonotrophic cycle was calculated.

The adult survival rate of wMel (Pud), wAlbB Ae. aegypti (Pud) strains and uninfected Ae. aegypti strains were analyzed using a separate cohort of 100 adult mosquitoes (50 males: 50 females) per replicate for each strain and diet. To ensure equal numbers of both sexes, a separate cohort of pupae reared under the same dietary conditions was utilized to initiate the experiment. A 10% sucrose solution was provided weekly, and females were blood-fed using chicken blood. Three days post-blood feeding, oviposition cups were placed inside the cages for egg laying. Mortality of both males and females was recorded daily until all the adults died. The entire procedure was repeated for the next generation.

2.4 Data analysis

Data for hatchability, pupal formation, adult emergence and fecundity rates were expressed as mean ± standard deviation for each generation separately. Mixed-effects regression models were applied to evaluate differences among diets for each outcome variable, considering the hierarchical structure of the experiment. Generation (two levels) and replicate were included as random effects to account for between-generation and between-replicate variability, while diet was treated as a fixed effect. This modeling approach ensured accurate estimation of diet effects while accounting for the non-independence of observations. The Shapiro wilk test was used to assess whether the data follow a normal distribution or not. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The mixed model-regression analysis results are detailed in the supplementary file no.2. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated for males and females of each mosquito strain, and the log-rank test was used to compare the median survival times (50%) among strains. To assess mortality risk, a Cox proportional hazards model was employed, providing hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals separately for males and females. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 14.2 (Texas, USA) and Microsoft Excel.

3 Results

3.1 Life table analysis

3.1.1 Hatchability

Based on the hatchability data, both the LD1 and LD4 diets had significant positive effects on all three Ae. aegypti lines. For the uninfected strain, hatchability was significantly higher on LD1. For the wAlbB strain, hatchability was significantly lower on LD2 and LD3 compared to LD1,but showed no significant difference on LD4. For the wMel strain, hatchability was significantly higher on LD4.

In the F1 generation, the hatchability ranged from 80.0% to 95.0% across the four diets for uninfected Ae. aegypti (Table 1). For the wAlbB (Pud) strain, hatchability was highest in LD4 (92.3%) and LD1 (89.7%), while for the wMel (Pud) strain, it was similarly highest in LD4 (87.7%) and LD1 (78.3%). In the F2 generation, hatchability ranged from 77.0% (LD2) to 94.3% (LD1) in uninfected Ae. aegypti, from 71.3% (LD3) to 86.3% (LD1) in the wAlbB (Pud) strain, and from 28.0% (LD2) to 84.7% (LD4) in the wMel (Pud) strain.

Table 1. Life table traits of the three Ae. aegypti strains under four different diets in both F0 and F1 generations.

Based on the mixed effect regression model, the hatchability rate was significantly lower in LD2 [β (SE) = -16.17 (2.64), P < 0.001], LD3 [β (SE) = -5.83 (2.64), P = 0.027], and LD4 [β (SE) = -5.83 (2.64), P = 0.027] compared to LD1 in the uninfected Ae. aegypti strains. Similarly, for the wAlbB (Pud) strain, the hatchability rate was significantly lower in LD2 [β (SE) = -13.33 (1.94), P < 0.001] and LD3 [β (SE) = -15.50 (1.94), P < 0.001], but not significantly different in LD4 [β (SE) = 2.50 (1.94), P = 0.197] compared to LD1. For the wMel strain, hatchability was significantly lower in LD2 [β (SE) = -48.67 (1.48), P < 0.001] and LD3 [β (SE) = -34.67 (1.48), P < 0.001], and significantly higher in LD4 [β (SE) = -7.83 (1.48), P < 0.001] relative to LD1.The diet with the highest hatchability is recommended for mass rearing in Wolbachia-based vector control. While all diets showed significant effects, only LD3 had a negative biological impact on hatchability.

3.1.2 Pupation

The pupation rate was significantly lower in LD2 and LD3 compared to LD1 in the uninfected Ae. aegypti strains, while LD4 showed no significant difference. For the wAlbB (Pud) strain, the pupation rate was significantly lower in LD2 but not significantly different in LD4 compared to LD1. For the wMel strain, pupation was significantly lower only in LD2 showed no significant differences relative to the LD1diet.

In the F0 generation, pupation ranged from 95.7% to 99.0% across the four diets in uninfected Ae. aegypti. For the wAlbB (Pud) strain, the highest pupation was observed in LD1 (97.3%), followed closely by LD2 (97.0%). In the wMel (Pud) strain, pupation was highest in LD2 (98.0%) and LD4 (96.7%). In the F1 generation, pupation ranged from 85.0% (LD3) to 97.3% (LD1) in uninfected Ae. aegypti, from 85.0% (LD3) to 99.0% (LD1) in the wAlbB (Pud) strain, and from 78.0% (LD2) to 99.3% (LD4) in the wMel (Pud) strain.

The pupation rate was significantly lower in LD2 [β (SE) = -5.00 (1.89), P = 0.008] and LD3 [β (SE) = -7.50 (1.89), P < 0.001] compared to LD1 in the uninfected Ae. aegypti strains, while LD4 showed no significant difference [β (SE) = -2.33 (1.89), P = 0.218]. For the wAlbB (Pud) strain, the pupation rate was significantly lower in LD2 [β (SE) = -7.17 (2.11), P = 0.001] and LD3 [β (SE) = -9.67 (2.11), P < 0.001], but not significantly different in LD4 [β (SE) = -1.33 (2.11), P = 0.528] compared to LD1. For the wMel strain, pupation was significantly lower only in LD2 [β (SE) = -8.50 (3.23), P = 0.009], while LD3 [β (SE) = -1.33 (3.23), P = 0.680] and LD4 [β (SE) = 1.33 (3.23), P = 0.680] showed no significant differences relative to the LD1diet.

3.1.3 Adult emergence

The adult emergence rate was significantly higher in the LD1& LD4 uninfected Ae. aegypti strains. For the wAlbB (Pud) strain, it was significantly lower in LD2 and LD3 but did not differ significantly different in LD4 compared to LD1. For the wMel strain, adult emergence was significantly higher in the LD1 diet. In the F0 generation, adult emergence ranged from 95.7% to 99.0% across the four diets in uninfected Ae. aegypti. For the wAlbB (Pud) strain, the highest adult emergence was observed in LD1 (97.3%) and LD2 (96.3%), followed by LD4 (96.0%). In the wMel (Pud) strain, adult emergence was highest in LD2 (97.0%) and LD4 (96.7%). In the F1 generation, adult emergence ranged from 85.0% (LD3) to 96.0% (LD4) in uninfected Ae. aegypti, from 85.0% (LD2) to 98.0% (LD1) in the wAlbB (Pud) strain, and from 78.0% (LD2) to 96.3% (LD1 and LD3) in the wMel (Pud) strain. Based on the mixed effect regression model, the adult emergence rate was significantly lower in LD2 [β (SE) = -4.00 (1.85), P = 0.031] and LD3 [β (SE) = -6.50 (1.85), P < 0.001] compared to LD1 in the uninfected Ae. aegypti strains, while LD4 showed no significant difference [β (SE) = -1.33 (1.85), P = 0.472]. For the wAlbB (Pud) strain, the adult emergence rate was significantly lower in LD2 [β (SE) = -7.00 (2.02), P = 0.001] and LD3 [β (SE) = -9.33 (2.02), P < 0.001], but not significantly different in LD4 [β (SE) = -0.83 (2.02), P = 0.679] compared to LD1. For the wMel strain, adult emergence was significantly lower only in LD2 [β (SE) = -8.00 (3.08), P = 0.009], while LD3 [β (SE) = -0.17 (3.08), P = 0.957] and LD4 [β (SE) = 0.00 (3.08), P = 0.999] showed no significant differences relative to the LD1 diet.

3.1.4 Male–female ratio

The male-to-female ratio of emerged adults was recorded for each diet across all Ae. aegypti strains. Males consistently outnumbered females across all diets and mosquito strains. Female percentage ranged from 47.8-49.5% (F0) and 48.3-49.0% (F1) in uninfected Ae. aegypti. For wAlbB (Pud), the highest female percentages were LD1 (49.7%) in F0 and LD2 (47.9%) in F1. For wMel (Pud), the highest were LD2 (49.1%) in F0 and LD1 (48.5%) in F1. The female percentage showed no significant differences in uninfected Ae. aegypti: LD2 [β=-1.09(0.63), P = 0.084], LD3 [β=-0.88(0.63), P = 0.160], LD4 [β=-0.70(0.63), P = 0.262]. Similarly, wMel strain showed no effects: LD2 [β=-0.46(0.50), P = 0.356], LD3 [β=-0.28(0.50), P = 0.573], LD4 [β=-0.50(0.50), P = 0.310]. However, the wAlbB strain had a significant reduction in LD3 [β=-2.09(1.04), P = 0.045].

3.1.5 Fecundity

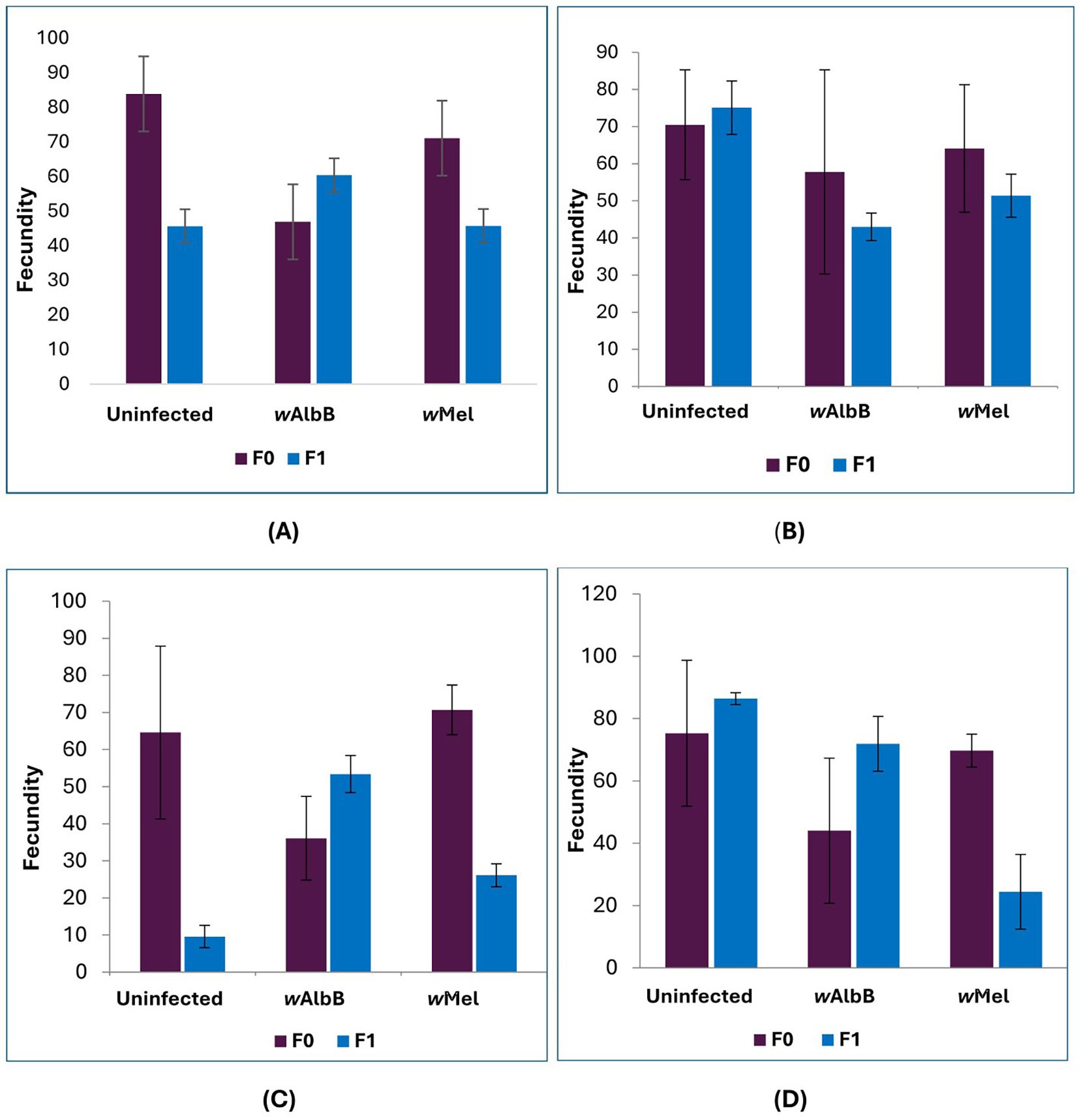

Fecundity was significantly lower only in LD3 compared to LD1 in the uninfected Ae. aegypti strains, while LD2 and LD4 showed no significant differences. For both Wolbachia-infected strains, no significant dietary effects on fecundity were observed. The fecundity ranged from 68.8 to 83.9 eggs per female across the four diets in uninfected Ae. aegypti in the F0 generation (Figure 2). For the wAlbB (Pud) strain, the highest fecundity was observed in LD2 (61.8 eggs), followed by LD1 (46.9 eggs) and LD4 (42.0 eggs). In the wMel (Pud) strain, fecundity was highest in LD4 (78.0 eggs) and LD3 (72.7 eggs). In the F1 generation, fecundity ranged from 9.6 (LD3) to 86.4 (LD4) eggs per female in uninfected Ae. aegypti, from 43.0 (LD2) to 71.9 (LD4) in the wAlbB (Pud) strain, and from 24.5 (LD4) to 51.4 (LD2) in the wMel (Pud) strain. The fecundity was significantly lower only in LD3 [β (SE) = -25.50 (11.11), P = 0.022] compared to LD1 in the uninfected Ae. aegypti strains, while LD2 [β (SE) = 8.46 (11.11), P = 0.446] and LD4 [β (SE) = 15.81 (11.11), P = 0.155] showed no significant differences. For both Wolbachia-infected strains, no significant dietary effects on fecundity were observed. In the wAlbB (Pud) strain: LD2 [β (SE) = -1.15 (9.40), P = 0.903], LD3 [β (SE) = -9.23 (9.40), P = 0.326], and LD4 [β (SE) = 3.44 (9.40), P = 0.715]. Similarly, for the wMel strain: LD2 [β (SE) = 0.21 (6.89), P = 0.976], LD3 [β (SE) = -9.06 (6.89), P = 0.189], and LD4 [β (SE) = -7.17 (6.89), P = 0.298] all remained non-significant compared to the LD1 diet.

Figure 2. Fecundity (mean ± SE) of uninfected, wAlbB, and wMel strains of Ae. aegypti (Puducherry strain) females across two generations (F0 and F1) under four larval diets: (A) LD1 – Fish feed; (B) LD2 – Laboratory rodent diet; (C) LD3 – Mushroom powder; (D) LD4 – Dog biscuit with Brewer’s yeast (3:2). Each bar represents the mean fecundity from three replicates of 100 larvae per mosquito line per diet (n = 3 replicates per group). Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean, representing the variability of the sample estimate for each group.

3.1.6 Adult survival

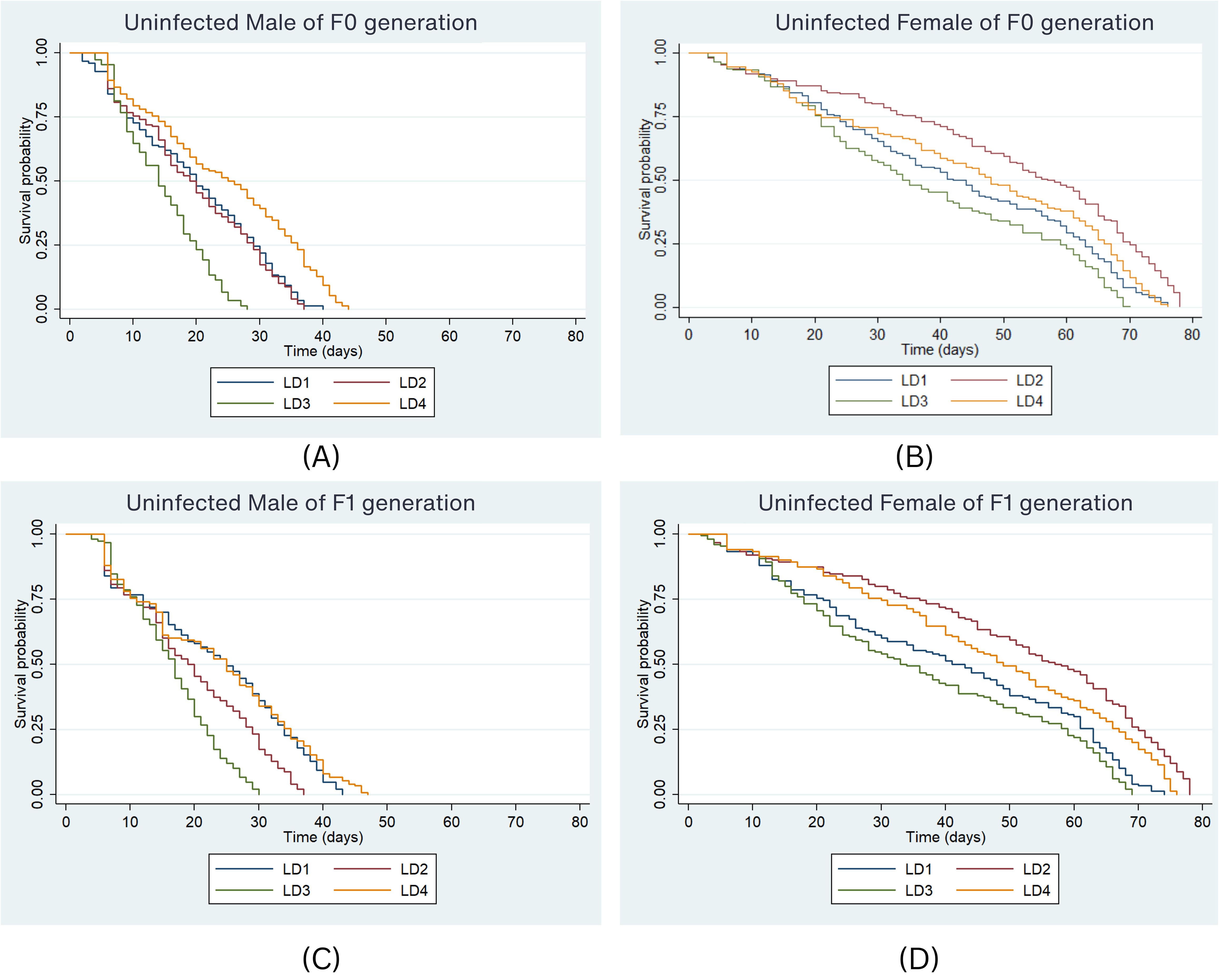

The impact of different diets on adult mosquito survival over time was examined. In the F0 generation, the median survival duration of uninfected male Ae. aegypti was 20 days under the LD1 diet (Figure 3A), i.e., 50% of males survived for 20 days on LD1. Under the LD2 diet, the median survival was 19 days, while in LD3 and LD4, 50% of males survived for 14 and 25 days, respectively. Survival curves significantly differed between larval diets for uninfected males (P < 0.001, Log-rank test). The risk of death was significantly higher in LD3 (HR = 2.03, P < 0.001) compared to LD1, while significantly lower mortality was observed in LD4 (HR = 0.55, P < 0.001) compared to LD1. Among females, the lowest median survival was 34 days under LD3, whereas median survival was 42, 57, and 48 days under LD1, LD2, and LD4, respectively (Figure 3B). The risk of death was significantly lower in LD2 (HR = 0.56, P < 0.001) compared to all other diets. No significant difference was observed for LD3 (HR = 1.35, P = 0.074) or LD4 compared to LD1.

Figure 3. Survival probability of uninfected Ae. aegypti male and female in F0 (A, B) & F1 (C, D) generation under the four larval diets. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were graphically presented to compare the impact of different diets on survival. The log-rank test was used to compare the median survival times (50%) among lines and the Cox proportional hazards model was employed, providing hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals separately for males and females.

In the F1 generation, 50% of males survived up to 25 days under LD1 and LD4 (Figure 3C). Survival probabilities differed significantly among larval diets (P < 0.001, Log-rank test). The risk of death was significantly higher in LD2 (HR = 1.61, P < 0.001) and LD3 (HR = 2.47, P < 0.001) compared to LD1. No significant difference was observed for LD4 (HR = 0.89, P = 0.333) compared to LD1. Among females, median survival was 41 days under LD1, while 50% survived up to 57, 33, and 49 days in LD2, LD3, and LD4, respectively (Figure 3D). The risk of death was highest under LD3 in both males and females across generations (HR = 1.58, 95% CI: 1.41–1.78, P < 0.001). Compared to females, males consistently had a higher risk of death across both generations (HR = 5.35, 95% CI: 4.79–5.97, P < 0.001). However, no significant difference in mortality risk was observed between generations in the uninfected Ae. aegypti strain.

For the wAlbB strain in the F0 generation, 50% of males survived for 27 days in LD4 and 26 days in LD1 (Figure 4A). The risk of death was significantly higher in LD2 (HR = 2.25, P < 0.001) and LD3 (HR = 3.51, P < 0.001) compared to LD1, with no significant difference in LD4 (HR = 1.03, P = 0.80). Among females, the highest median survival was 52 days under LD1, followed by 42 and 37 days in LD4 and LD3, respectively (Figure 4B). Significant differences were observed under LD2 (HR = 4.88, P < 0.001), LD3 (HR = 2.15, P < 0.001), and LD4 (HR = 1.76, P < 0.001) compared to LD1.

Figure 4. Survival probability of wAlbB male and female in F0 (A, B) & F1 (C, D) generation under the four larval diets. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were graphically presented to compare the impact of different diets on survival. The log-rank test was used to compare the median survival times (50%) among lines and the Cox proportional hazards model was employed, providing hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals separately for males and females.

In F1, 50% of wAlbB males survived for 23 days under LD1 (Figure 4C). Median survival was 18 days in LD2, and 14 and 20 days in LD3 and LD4, respectively. Survival curves differed significantly across larval diets (P < 0.001, log-rank test). The risk of death was significantly higher in LD2 (HR = 1.97, P < 0.001) and LD3 (HR = 3.15, P < 0.001), but not in LD4 (HR = 1.2, P = 0.11) compared to LD1. Among females, median survival was highest in LD4 (44 days) (Figure 4D). The risk of death was significantly higher in LD2 (HR = 2.50, P < 0.001), while significant differences were also recorded in LD2 (HR = 2.50, P < 0.001) and LD4 (HR = 0.77, P < 0.001) compared to LD1. Overall, the risk of death was significantly higher among males under LD2 (HR = 2.36, 95% CI: 2.09–2.66, P < 0.001) and LD3 (HR = 1.94, 95% CI: 1.72–2.18, P < 0.001). Lower mortality risk (HR < 1) was observed under LD1 and LD4, but not statistically significant (P > 0.001). Males exhibited significantly higher mortality than females across both generations (HR = 3.45–4.21, P < 0.001), though no significant variation was observed between generations (HR = 1.13, 95% CI: 1.04–1.22, P > 0.001).

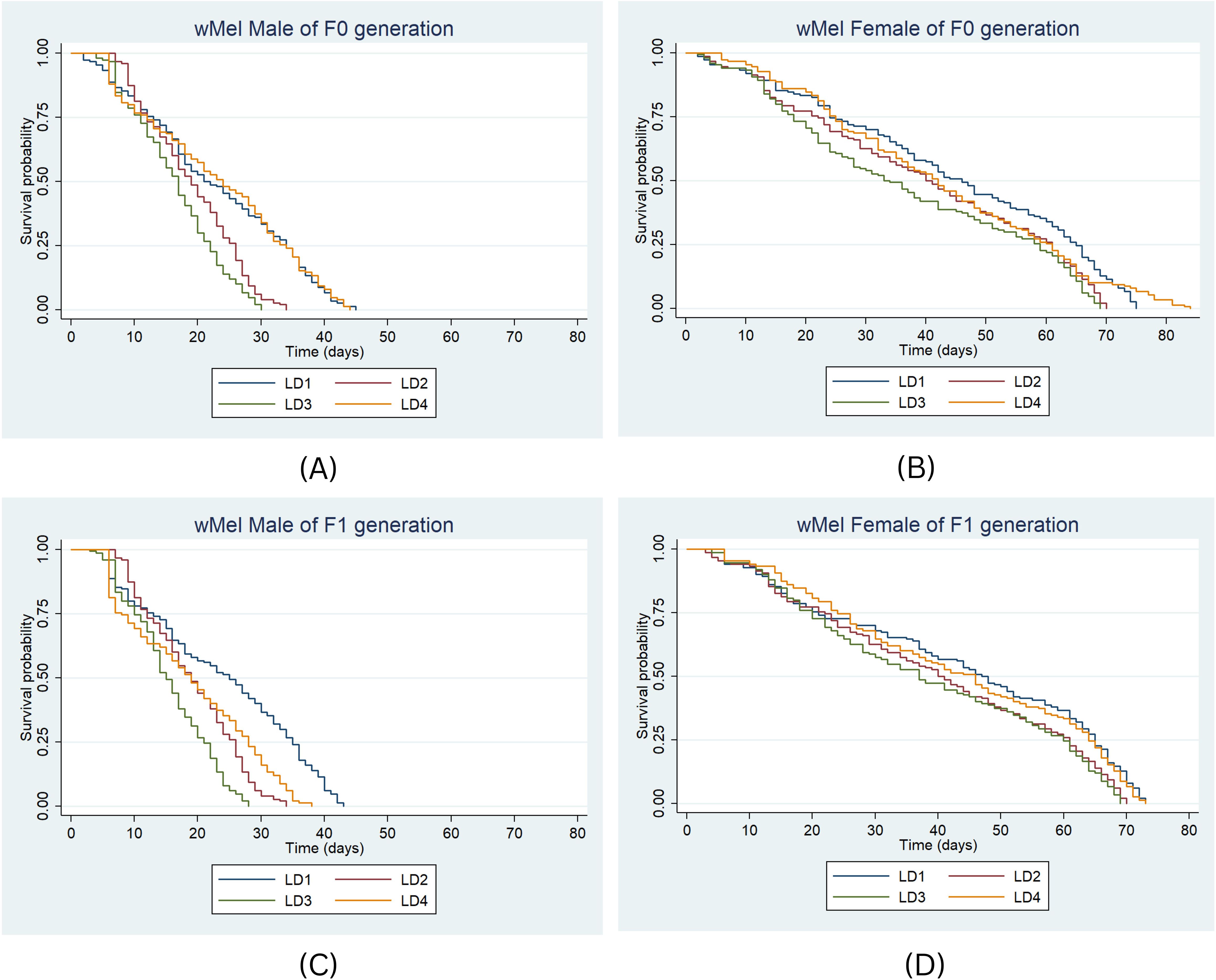

For the wMel strain in F0, median survival durations for males differed significantly across diets: LD2 (HR = 1.94, P < 0.001), LD3 (HR = 2.53, P < 0.001), and LD4 (HR = 0.97, P < 0.001) compared to LD1 (Figure 5A). For females, the highest median survival was 46 days under LD1 and the lowest was 33 days under LD3 (Figure 5B). Significant differences were found for LD2 (HR = 1.51, P < 0.001) and LD3 (HR = 1.53, P < 0.001) compared to LD1.

Figure 5. Survival probability of wMel male and female in F0 (A, B) & F1 (C, D) generation under the four larval diets. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were graphically presented to compare the impact of different diets on survival. The log-rank test was used to compare the median survival times (50%) among lines and the Cox proportional hazards model was employed, providing hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals separately for males and females.

In the F1 generation, 50% of wMel males survived for 25 days under LD1 (Figure 5C). Median survival was 19 days in LD2, and 15 and 19 days in LD3 and LD4, respectively. The risk of death was significantly higher in LD2 (HR = 2.3, P < 0.001), LD3 (HR = 3.5, P < 0.001), and LD4 (HR = 1.9, P = 0.11) compared to LD1. For females, median survival durations were 47 days in LD1, and 40, 37, and 46 days in LD2, LD3, and LD4, respectively (Figure 5D). The risk of death was significantly higher under LD3 (HR = 1.5, P < 0.001) and LD2 (HR = 1.4, P < 0.001), while a significant difference was not observed for LD4 (HR = 1.08, P = 0.47) compared to LD1.

In summary, among the wMel strains, the death risk was significantly higher under LD2 (HR = 1.49, 95% CI: 1.33–1.67, P < 0.001) and LD3 (HR = 1.83, 95% CI: 1.63–2.05, P < 0.001). Males consistently exhibited higher mortality than females (HR = 4.83, 95% CI: 4.34–5.38, P < 0.001), whereas no significant difference was observed between generations (HR = 1.06, 95% CI: 0.98–1.15, P > 0.001).

4 Discussion

Sustainable vector control tools are consistently in demand to suppress vector populations and prevent vector-borne diseases. Integrated Vector Control Management (IVM) is a comprehensive approach that ensures the sustainability of vector control methods, explicitly targeting the control of dengue vectors (38). Trans infection of symbiotic bacteria into a targeted vector and releasing them into the field for population replacement/suppression is one of these comprehensive approaches to tackling vector populations (39, 40). It is a long-term solution and a promising tool for controlling Aedes mosquitoes, mainly Ae. aegypti, the principal vector of major arboviral diseases. Continuous use of insecticides has resulted in resistance among the mosquito population and has made them no longer effective against the vectors. Hence, the Wolbachia-based vector control strategy offers an alternative that may be less prone to resistance issues, helping maintain effective control measures in the long run (41).

Multiple countries have successfully released Wolbachia-transinfected Aedes mosquitoes for population replacement, with the World Mosquito Program introducing Wolbachia in 14 countries (42). The wMel and wAlbB strains have been successfully established in wild Ae. aegypti populations in Australia and Malaysia (43–45). Laboratory studies demonstrate a notable reduction in virus transmission capacity, particularly for dengue (8, 46, 47). Wolbachia infection enhances diet-related nutritional stress, reducing dengue susceptibility (48) and competes with pathogens for nutrients, inhibiting replication and shortening vector lifespan (49, 50). Field studies following releases confirm effectiveness, with mass releases of Wolbachia-transinfected males significantly reducing egg hatch rates through cytoplasmic incompatibility and decreasing Zika virus transmission compared to control areas (16, 51).

Field release of Wolbachia-transinfected Ae. aegypti requires fitness evaluation, as successful spread depends on efficient maternal transmission without substantial fitness costs (46, 47). Sadanandane et al. (31) assessed wMel (Pud) and wAlbB (Pud) strain fitness, examining life-history parameters, infection persistence, maternal transmission, cytoplasmic incompatibility, and insecticide susceptibility. Proper larval nutrition is crucial for the mass release of competent mosquitoes and high-quality transinfected females (52, 53).

The two primary dietary formulations are widely utilized in mosquito laboratory studies: The IAEA-standardized diet and formulations based on commercial fish food products like TetraMin. Despite of this, previous studies evaluated different larval diets for their effect on Ae. aegypti fitness. In Mexico, protein-based diets such as tilapia fish food, bovine liver powder, and porcine meal positively affected Wolbachia-infected Ae. aegypti development (28). Similarly, a study conducted in Sri Lanka revealed that a combination of dry fish powder and brewer’s yeast enhanced larval development, increased reproductive output, and extended male lifespan when compared to the standard IAEA dietary formulation (29). Correspondingly, Bond et al. (21) found that laboratory rodent feed formulations resulted in larger adult mosquitoes and enhanced fecundity, attributed to their elevated carbohydrate composition. Conversely, replacing animal-derived proteins with plant-based protein sources in larval nutrition negatively affected egg viability, extended developmental periods, and diminished reproductive performance (30). A recent study by Yatim et al. (54) revealed that uninfected mosquito strains demonstrated superior overall fitness performance across all tested dietary formulations, including plant-based diet, Khan diet, fish food, and IAEA diet, compared to wMelM and wAlbB trans-infected strains. While previous studies have compared established larval diet formulations such as IAEA, Khan diet, and fish feed-based diets for mass production of Ae. aegypti, the current study optimized practical larval dietary approaches for scaling up mass production of Wolbachia transinfected Ae.aegypti (wMel and wAlbB) strains in resource-limited settings. The current study evaluated four commercially available larval diets: fish feed (LD1), laboratory rodent diet (LD2), mushroom powder (LD3), and dog biscuits with brewer’s yeast (LD4) on two Wolbachia-transinfected strains compared to uninfected Ae. aegypti. Fish feed (TetraBits) and dog biscuits with brewer’s yeast are routinely used at ICMR-VCRC, while mushroom powder was included despite a higher cost to compare plant versus animal protein effects. The study examined two generations (F0 and F1) to understand how larval nutrition influences adults and progeny, evaluating life table characteristics including hatchability, pupation rate, adult emergence, sex ratio, fecundity, and survival.

4.1 Effect of larval diets on life table traits

Fish feed (LD1) and dog biscuit with yeast (LD4) significantly impacted hatchability of the three Ae. aegypti strains compared to other diets, with no significant difference between generations (F1 & F2). High egg hatchability is crucial for mass rearing, ensuring sufficient viable larvae for mosquito production (55). These findings line up with Salim et al. (30), who reported the highest hatchability with the IAEA diet containing fish meal (73.9%) and the lowest with mushroom powder (40.7%), while Bond et al. (21) found higher hatchability (~80%) with the laboratory rodent diet compared to the IAEA diet.

A larger number of pupae would contribute to a higher number of adult emergences, a key parameter in the life table of the mosquito (30). Similar to hatchability, the diets, LD1 and LD4, had a significant impact, resulting in a higher percentage of pupation in all Ae. aegypti strains. We recorded the highest pupation rate for the wAlbB strain under LD1 and LD4. The wMel strain also showed higher pupation under LD1 and LD4. However, the uninfected Ae. aegypti strain showed a comparatively lower percentage of pupation in all the diets. In a recent study by Yatim et al. (2025), it was found that uninfected mosquito strains demonstrated superior overall fitness performance across all tested dietary formulations, including a plant-based diet, Khan diet, fish food, and IAEA diet, compared to wMelM and wAlbB infected strains. On the contrary, Contreras-Perera et al. (28) observed no significant differences between the percentage pupation of Wolbachia-transinfected and wild-type lab-established strain, Ae. aegypti at the different diets used in their study.

In an impact study comparing Khan’s and IAEA-2 larval diets, the IAEA-2 diet resulted in higher pupation rates and produced larger adult mosquitoes in Wolbachia-uninfected Ae. aegypti, with improved male longevity (56). Their findings demonstrate that both diets have significant positive effects across all the life table traits, making them suitable for sterile insect technique applications. Similarly, Gunathilaka et al. (57) reported the highest pupation rate at the highest larval feed concentration compared to the lowest, supporting the significant influence of larval nutritional resources on pupation success.

Adult emergence in the three mosquito strains was proportional to pupation rates. Under the LD1 diet, Wolbachia-transinfected strains (wMel and wAlbB) showed higher emergence than uninfected Ae. aegypti in F1 generation, with the opposite trend in F0 generation, though differences were not statistically significant. LD1 and LD4 diets produced no significant variation between strains or generations, achieving >90% emergence across all three strains. On the other hand, LD2 and LD3 diets showed significant differences between strains and generations. Males consistently outnumbered females across all strains and diets, but larval diets did not significantly affect the male-to-female ratio in either generation. This consistent sex ratio across diets supports Wolbachia population replacement strategies, which require equal proportions of both sexes for mass rearing. These findings contrast with Bond et al. (21), who reported higher male proportions under the IAEA diet compared to the laboratory rodent diets.

Significant variability in hatchability, pupation, adult emergence, male–female ratio, fecundity, and adult survival among Wolbachia-transinfected Ae. aegypti strains and diets is primarily explained by differences in larval diet composition and mosquito infection status. Larval diets that are balanced in nutrients (such as LD1 and LD4) support higher hatchability and overall fitness, likely due to optimal protein and carbohydrate ratios, which enhance development and egg viability. In contrast, diets deficient or imbalanced in nutrients (such as LD3 and LD2) can restrict larval development, reduce energy reserves, and lead to lower hatchability, pupation, and survival rates. Wolbachia infection status also contributes to observed variability, as different strains respond distinctly to dietary composition, influencing life table parameters beyond diet alone. The interplay of genetic background, nutrient intake, and microbial symbionts (Wolbachia) underscores the biological basis for significant differences in mosquito population outcomes across experimental groups. Thus, both dietary quality and infection status are key drivers of the significant variability observed in Ae. aegypti life table parameters.

4.2 Influence on mosquito reproductive traits and survival

A significant positive effect on fecundity was observed among mosquito strains under LD1 and LD4 diets, supporting the importance of diet composition in influencing reproductive fitness. In contrast, LD2 and LD3 diets failed to produce a significant impact, likely due to suboptimal nutritional content or poorer assimilation efficiency. These findings are consistent with earlier observations by Sadanandane et al. (31), who reported higher fecundity in wAlbB compared to both wild-type and wMel strains when reared under fish feed diets. A similar study also observed that wMel strains persistently had low fecundity compared to wAlbB and the uninfected strains of Ae. aegypti in all the diets (Plant-based, Khan’s, Fish feed and IAEA diets) tested (Yatim et al, 2025). Our study results revealed that the fecundity of all the mosquito strains was high under LD1 and LD2 diets, and the wAlbB strain of Ae. aegypti showed comparatively high fecundity under all the diets. Collectively, these results underscore the interplay between Wolbachia strain, generation, and larval diet in shaping reproductive capacity. Importantly, the improved fecundity of transinfected strains such as wAlbB under specific diet conditions suggests a potential pathway for optimizing mass-rearing protocols for the release of Wolbachia-transinfected Ae. aegypti into the field.

The highest survival was observed in uninfected females reared on the LD2 diet, with a lifespan of 57 days in both the F0 and F1 generations, indicating that this diet provides optimal nutritional support for adult longevity. In contrast, the LD3 diet resulted in the shortest survival (33 days) for both uninfected and wMel-infected females, reflecting its inadequate nutritional composition. Notably, the LD1 and LD4 diets significantly increased median survival in uninfected F0 males, highlighting the protective effects of these protein-rich diets. Similarly, Sasmita et al. (56) demonstrated that both Khan’s and IAEA-2 larval diets significantly enhanced adult body size and survival parameters, supporting their suitability for SIT applications. Furthermore, Gunathilaka et al. (57) found that increasing larval food supply resulted in adults with higher fecundity and greater survival rates, underscoring the critical influence of nutritional quality and quantity on mosquito life-history traits.

4.3 Implications for Wolbachia transmission and vector control

The study highlights cost-effective larval diets for mass rearing Wolbachia-transinfected and uninfected Ae. aegypti. Fish feed (LD1) and dog biscuit with brewer’s yeast (LD4) significantly improved life table traits compared to mushroom powder and laboratory rodent diets, highlighting the importance of protein-rich nutrition for larval development and survival (29, 58). These findings support adopting a low-cost diet for Indian mass-rearing facilities. A balanced mosquito diet enhances Wolbachia density and stability within the mosquitoes, strengthening pathogen blocking. Diet quality throughout a mosquito’s life influences adult size, lifespan, and biting behavior, and pathogen transmission capacity (59). The diet with significant effects is recommended for mass rearing in Wolbachia-based vector control. However, statistical significance alone doesn’t guarantee practical benefits. While all diets showed significant effects, only LD3 had a negative biological impact on hatchability. This highlights the importance of considering both statistical and biological relevance in diet selection for vector control programs. This study validated suitable larval diets for mass rearing transinfected mosquitoes, with life table traits significantly impacted by recommended diets. Mosquito survival and wild population establishment for Wolbachia dissemination is fundamental for successful vector control strategies, potentially contributing to reduced dengue and arboviral disease burden as a promising control tool.

4.4 Limitations of the study

The limitation of this study is the absence of formal sample size calculation and power analysis. As an exploratory experimental study designed to screen and compare artificial larval diets, the primary goal was to assess feasibility and biological plausibility rather than detect a pre-specified effect size. Following WHO guidelines for bioassay, 100 third-instar larvae per replicate were used for each of the three Wolbachia strains. This approach may limit the statistical power and generalizability of the findings, which will be addressed in future, more comprehensive studies.

5 Conclusion

This study demonstrates that fish feed (LD1) and dog biscuit with brewer’s yeast (LD4) are superior, cost-effective larval diets for mass-rearing Wolbachia-transinfected Ae. aegypti. These protein-rich diets significantly enhanced critical life table parameters; hatchability, pupation rates, adult emergence, fecundity, and survival across both infected and uninfected strains over two generations. The wAlbB strain showed particularly robust performance under these optimal dietary conditions. The results of this study suggest that LD1 (fish feed) can be recommended as the superior larval diet for the mass rearing of Wolbachia-transinfected strains, although both LD1 and LD4 diets demonstrated positive effects on all the Ae. aegypti strains. Meanwhile, LD4 (dog biscuit + brewer’s yeast) can be recommended for the routine rearing of uninfected Ae. aegypti colonies, as it is comparatively cost-effective and readily available in India. These findings could contribute to the large-scale mosquito rearing programs under the Wolbachia strategy, ultimately supporting the implementation of sustainable vector control approaches for arboviral disease management.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The manuscript presents research on animals that do not require ethical approval for their study.

Author contributions

YG: Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Formal analysis. VP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SA: Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. VB: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SAN: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MR: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The study was financially supported by internal funding from the Indian Council of Medical Research-Vector Control Research Centre (ICMR-VCRC) for the fulfillment of the M.Sc. dissertation work.

Acknowledgments

This research is a part of Ms. G. Yazhini’s dissertation work, submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the M.Sc. in Public Health Entomology at Pondicherry University (Puducherry, India). The study was financially supported by internal funding from the ICMR-Vector Control Research Centre. We sincerely thank Mr. Manimaran, Mr. Mohan, and Mr. C. Vengadessane for their invaluable help with mosquito rearing. We also express our heartfelt appreciation to Ms. Kayalvizhi, Mrs. Esther, Mrs. Devi, Ms. Alosia, Mr. Amal Raj, Mr. Vinodh Kumar, Mr. Jithumon, Mrs. Ranjana Devi, Ms. Amrutha Vijayan, and Ms. Pavithra for their dedicated efforts in maintaining the Wolbachia-infected mosquito colonies.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/finsc.2025.1679816/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Table 1 | Larval diets and their composition (As per manufacturer’s standard).

Supplementary File 1 | Mixed-effect linear regression model results.

Supplementary File 2 | Raw data of mosquito survival in each stage under different diets (F0 & F1 generation).

References

1. World Health Organisation. Disease outbreak news (2024). Available online at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2024-DON518 (Accessed July 11, 2025).

2. National Center For Vector Borne Diseases Control. National center for vector borne diseases control (NCVBDC)—Government of India (2024). National Center For Vector Borne Diseases Control. Available online at: https://ncvbdc.mohfw.gov.in/index4.php?lang=1&level=0&linkid=431&lid=3715 (Accessed July 11, 2025).

3. Dorigatti I, McCormack C, Nedjati-Gilani G, and Ferguson NM. Using wolbachia for dengue control: insights from modelling. Trends Parasitol. (2018) 34:102–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2017.11.002

4. Bonneau M, Atyame C, Beji M, Justy F, Cohen-Gonsaud M, Sicard M, et al. Culex pipiens crossing type diversity is governed by an amplified and polymorphic operon of Wolbachia. Nat Commun. (2018) 9:319. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02749-w

5. Yang Y, He Y, Zhu G, Zhang J, Gong Z, Huang S, et al. Prevalence and molecular characterization of Wolbachia in field-collected Aedes albopictus, Anopheles sinensis, Armigeres subalbatus, Culex pipiens and Cx. Tritaeniorhynchus in China. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2021) 15:e0009911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009911

6. Reyes JIL, Suzuki T, Suzuki Y, and Watanabe K. Detection and quantification of natural Wolbachia in Aedes aEgypti in Metropolitan Manila, Philippines using locally designed primers. Front Cell Infection Microbiol. (2024) 14:1360438. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2024.1360438

7. Hughes GL and Rasgon JL. Transinfection: A method to investigate Wolbachia –host interactions and control arthropod-borne disease. Insect Mol Biol. (2014) 23:141–51. doi: 10.1111/imb.12066

8. Axford JK, Ross PA, Yeap HL, Callahan AG, and Hoffmann AA. Fitness of wAlbB Wolbachia Infection in Aedes aEgypti: Parameter Estimates in an Outcrossed Background and Potential for Population Invasion. Am Soc Trop Med Hygiene. (2016) 94:507–16. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0608

9. Moretti R, Lim JT, Ferreira AGA, Ponti L, Giovanetti M, Yi CJ, et al. Exploiting wolbachia as a tool for mosquito-borne disease control: pursuing efficacy, safety, and sustainability. Pathogens. (2025) 14:285. doi: 10.3390/pathogens14030285

10. Liang X, Tan CH, Sun Q, Zhang M, Wong PSJ, Li MI, et al. Wolbachia wAlbB remains stable in Aedes aEgypti over 15 years but exhibits genetic background-dependent variation in virus blocking. PNAS Nexus. (2022) 1:pgac203. doi: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgac203

11. Fox T, Sguassero Y, Chaplin M, Rose W, Doum D, Arevalo-Rodriguez I, et al. Wolbachia -carrying Aedes mosquitoes for preventing dengue infection. Cochrane Database Systematic Rev. (2023) 2023. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD015636

12. Montenegro D, Cortés-Cortés G, Balbuena-Alonso MG, Warner C, and Camps M. Wolbachia-based emerging strategies for control of vector-transmitted disease. Acta Tropica. (2024) 260:107410. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2024.107410

13. Soh S, Ho SH, Ong J, Seah A, Dickens BS, Tan KW, et al. Strategies to mitigate establishment under the wolbachia incompatible insect technique. Viruses. (2022) 14:1132. doi: 10.3390/v14061132

14. Yen P-S and Failloux A-B. A review: wolbachia-based population replacement for mosquito control shares common points with genetically modified control approaches. Pathog (Basel Switzerland). (2020) 9:404. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9050404

15. O’Connor L, Plichart C, Sang AC, Brelsfoard CL, Bossin HC, and Dobson SL. Open release of male mosquitoes infected with a wolbachia biopesticide: field performance and infection containment. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2012) 6:e1797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001797

16. Mains JW, Kelly PH, Dobson KL, Petrie WD, and Dobson SL. Localized Control of Aedes aEgypti (Diptera: Culicidae) in Miami, FL, via Inundative Releases of Wolbachia-Infected Male Mosquitoes. J Med Entomology. (2019) 56:1296–303. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjz051

17. Zheng X, Zhang D, Li Y, Yang C, Wu Y, Liang X, et al. Incompatible and sterile insect techniques combined eliminate mosquitoes. Nature. (2019) 572:56–61. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1407-9

18. Lim JT, Bansal S, Chong CS, Dickens B, Ng Y, Deng L, et al. Efficacy of Wolbachia-mediated sterility to reduce the incidence of dengue: A synthetic control study in Singapore. Lancet Microbe. (2024) 5:e422–32. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(23)00397-X

19. Martín-Park A, Che-Mendoza A, Contreras-Perera Y, Pérez-Carrillo S, Puerta-Guardo H, Villegas-Chim J, et al. Pilot trial using mass field-releases of sterile males produced with the incompatible and sterile insect techniques as part of integrated Aedes aEgypti control in Mexico. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2022) 16:e0010324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010324

20. de Castro Poncio L, Apolinário Dos Anjos F, de Oliveira DA, de Oliveira da Rosa A, Piraccini Silva B, Rebechi D, et al. Prevention of a dengue outbreak via the large-scale deployment of Sterile Insect Technology in a Brazilian city: A prospective study. Lancet Regional Health Americas. (2023) 21:100498. doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2023.100498

21. Bond JG, Ramírez-Osorio A, Marina CF, Fernández-Salas I, Liedo P, Dor A, et al. Efficiency of two larval diets for mass-rearing of the mosquito Aedes aEgypti. PloS One. (2017) 12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187420

22. de Castro Poncio L, Dos Anjos FA, de Oliveira DA, Rebechi D, de Oliveira RN, Chitolina RF, et al. Novel sterile insect technology program results in suppression of a field mosquito population and subsequently to reduced incidence of dengue. J Infect Dis. (2021) 224:1005–14. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab049

23. Kavran M, Puggioli A, Šiljegović S, Čanadžić D, Laćarac N, Rakita M, et al. Optimization of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) Mass Rearing through Cost-Effective Larval Feeding. Insects. (2022) 13:6. doi: 10.3390/insects13060504

24. Clements AN. The sources of energy for flight in mosquitoes. J Exp Biol. (1955) 32:547–54. doi: 10.1242/jeb.32.3.547

25. Araújo Md-S, Gil LHS, and e-Silva Ad-A. Larval food quantity affects development time, survival and adult biological traits that influence the vectorial capacity of Anopheles darlingi under laboratory conditions. Malaria J. (2012) 11:261. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-261

26. Gunathilaka P. A. D. H. N., Uduwawala UMHU, Udayanga N. W. B. A. L., Ranathunge RMTB, Amarasinghe LD, and Abeyewickreme W. Determination of the efficiency of diets for larval development in mass rearing Aedes aEgypti (Diptera: Culicidae). Bull Entomological Res. (2018) 108:583–92. doi: 10.1017/S0007485317001092

27. Medici A, Carrieri M, Scholte E-J, Maccagnani B, Dindo ML, and Bellini R. Studies on aedes albopictus larval mass-rearing optimization. J Economic Entomology. (2011) 104:266–73. doi: 10.1603/EC10108

28. Contreras-Perera Y, Flores-Pech JP, Pérez-Carillo S, Puerta-Guardo H, Geded-Moreno E, Correa-Morales F, et al. Different larval diets for Aedes aEgypti (Diptera: Culicidae) under laboratory conditions: in preparation for a mass-rearing system. Biologia. (2023) 78:3387–99. doi: 10.1007/s11756-023-01469-5

29. Senevirathna U, Udayanga L, Ganehiarachchi GASM, Hapugoda M, Ranathunge T, and Silva Gunawardene N. Development of an alternative low-cost larval diet for mass rearing of aedes aEgypti mosquitoes. BioMed Res Int. (2020) 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2020/1053818

30. Salim M, Kamran M, Khan I, Saljoqi AUR, Ahmad S, Almutairi MH, et al. Effect of larval diets on the life table parameters of dengue mosquito, Aedes aEgypti (L.) (Diptera: Culicidae) using age-stage two sex life table theory. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:11969. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-39270-8

31. Sadanandane C, Gunasekaran K, Panneer D, Subbarao SK, Rahi M, Vijayakumar B, et al. Studies on the fitness characteristics of wMel- and wAlbB-introgressed Aedes aEgypti (Pud) strains in comparison with wMel- and wAlbB-transinfected Aedes aEgypti (Aus) and wild-type Aedes aEgypti (Pud) strains. Front Microbiol. (2022) 13:947857. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.947857

32. Morelli G, Fusi E, Tenti S, Serva L, Marchesini G, Diez M, et al. Study of ingredients and nutrient composition of commercially available treats for dogs. Veterinary Rec. (2018) 182:351. doi: 10.1136/vr.104489

33. Xu X, Yan H, Chen J, and Zhang X. Bioactive proteins from mushrooms. Biotechnol Adv. (2011) 29:667–74. doi: 10.1016/j.bioteChadv.2011.05.003

34. Jeffrey Gutiérrez EH, Walker KR, Ernst KC, Riehle MA, and Davidowitz G. Size as a proxy for survival in aedes aEgypti (Diptera: culicidae) mosquitoes. J Med Entomology. (2020) 57:1228–38. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjaa055

35. World Health Organization, (2022). Manual for Monitoring Insecticide Resistance in Mosquito Vectors and Selecting Appropriate Interventions; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland.

36. World Mosquito Program. World mosquito program (2017). Available online at: https://www.worldmosquitoprogram.org/en/home (Accessed April 5, 2024).

37. Pearl R and Miner JR. Experimental studies on the duration of life. XIV. The comparative mortality of certain lower organisms. Q Rev Biol. (1935) 10:60–79. doi: 10.1086/394476

38. World Mosquito Program [WMP] (2018). Mosquito Production. SOP on Blood Feeding Using Beewax Pots: World Mosquito Program.

39. Dodson BL, Andrews ES, Turell MJ, and Rasgon JL. Wolbachia effects on Rift Valley fever virus infection in Culex tarsalis mosquitoes. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2017) 11:e0006050. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006050

40. Minwuyelet A, Petronio GP, Yewhalaw D, Sciarretta A, Magnifico I, Nicolosi D, et al. Symbiotic Wolbachia in mosquitoes and its role in reducing the transmission of mosquito-borne diseases: Updates and prospects. Front Microbiol. (2023) 14:1267832. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1267832

41. Van Den Berg H, Da Silva Bezerra HS, Al-Eryani S, Chanda E, Nagpal BN, Knox TB, et al. Recent trends in global insecticide use for disease vector control and potential implications for resistance management. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:23867. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-03367-9

42. Lin Y-H, Joubert DA, Kaeser S, Dowd C, Germann J, Khalid A, et al. Field deployment of Wolbachia -infected Aedes aEgypti using uncrewed aerial vehicle. Sci Robotics. (2024) 9:eadk7913. doi: 10.1126/scirobotics.adk7913

43. O’Neill SL, Ryan PA, Turley AP, Wilson G, Retzki K, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, et al. Scaled deployment of Wolbachia to protect the community from Aedes transmitted arboviruses. Gates Open Res. (2018) 2:36. doi: 10.12688/gatesopenres.12844.1

44. Nazni WA, Hoffmann AA, NoorAfizah A, Cheong YL, Mancini MV, Golding N, et al. Establishment of Wolbachia Strain wAlbB in Malaysian Populations of Aedes aEgypti for Dengue Control. Curr Biol. (2019) 29:4241–4248.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.11.007

45. Ryan PA, Turley AP, Wilson G, Hurst TP, Retzki K, Brown-Kenyon J, et al. Establishment of wMel Wolbachia in Aedes aEgypti mosquitoes and reduction of local dengue transmission in Cairns and surrounding locations in northern Queensland, Australia. Gates Open Res. (2020) 3:1547. doi: 10.12688/gatesopenres.13061.2

46. Fraser JE, De Bruyne JT, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Stepnell J, Burns RL, Flores HA, et al. Novel Wolbachia-transinfected Aedes aEgypti mosquitoes possess diverse fitness and vector competence phenotypes. PloS Pathog. (2017) 13:e1006751. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006751

47. Liu W-L, Yu H-Y, Chen Y-X, Chen B-Y, Leaw SN, Lin C-H, et al. Lab-scale characterization and semi-field trials of Wolbachia Strain wAlbB in a Taiwan Wolbachia introgressed Ae. aEgypti strain. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2022) 16:e0010084. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010084

48. Caragata EP, Rezende FO, Simões TC, and Moreira LA. Diet-induced nutritional stress and pathogen interference in wolbachia-infected aedes aEgypti. PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2016) 10:e0005158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005158

49. Geoghegan V, Stainton K, Rainey SM, Ant TH, Dowle AA, Larson T, et al. Perturbed cholesterol and vesicular trafficking associated with dengue blocking in Wolbachia-infected Aedes aEgypti cells. Nat Commun. (2017) 8:526. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00610-8

50. De Oliveira S, Villela DAM, Dias FBS, Moreira LA, and Maciel De Freitas R. How does competition among wild type mosquitoes influence the performance of Aedes aEgypti and dissemination of Wolbachia pipientis? PloS Negl Trop Dis. (2017) 11:e0005947. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005947

51. Beebe NW, Pagendam D, Trewin BJ, Boomer A, Bradford M, Ford A, et al. Releasing incompatible males drives strong suppression across populations of wild and Wolbachia -carrying Aedes aEgypti in Australia. Proc Natl Acad Sci. (2021) 118:e2106828118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2106828118

52. Benedict MQ, Knols BG, Bossin HC, Howell PI, Mialhe E, Caceres C, et al. Colonisation and mass rearing: Learning from others. Malaria J. (2009) 8:S4. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-S2-S4

53. Dutra HLC, Rodrigues SL, Mansur SB, De Oliveira SP, Caragata EP, and Moreira LA. Development and physiological effects of an artificial diet for Wolbachia-infected Aedes aEgypti. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:15687. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16045-6

54. Yatim MF, Ross PA, Gu X, and Hoffmann AA. (2025). Impact of larval diet on fitness outcomes of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes infected with wAlbB and wMelM. Parasit Vectors. (2025). 18(1):386. doi: 10.1186/s13071-025-06978-7

55. Balestrino F, Puggioli A, Mamai W, Bellini R, and Bouyer J. A mass rearing method to aliquot and hatch Aedes mosquito eggs using capsules. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:30276. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-81385-z

56. Sasmita HI, Tu WC, Bong LJ, and Neoh KB. Effects of larval diets and temperature regimes on life history traits, energy reserves and temperature tolerance of male Aedes aEgypti (Diptera: Culicidae): optimizing rearing techniques for the sterile insect programmes. Parasites Vectors. (2019) 12(1):578. doi: 10.1186/s13071-019-3830-z

57. Gunathilaka N, Upulika H, Udayanga L, and Amarasinghe D. Effect of larval nutritional regimes on morphometry and vectorial capacity of Aedes aEgypti for dengue transmission. BioMed Res Int. (2019), 3607342. doi: 10.1155/2019/3607342

58. Li Q, Wei T, Sun Y, Khan J, and Zhang D. Optimizing cost-effective larval diets for mass rearing of aedes mosquitoes in vector control programs. Insects. (2025) 16:483. doi: 10.3390/insects16050483

Keywords: Wolbachia, larval diet, mass rearing, Aedes aegypti, life table, adult survival, fecundity, India

Citation: Gunasekaran Y, Pachalil Thiruvoth V, Annamalai S, Balakrishnan V, Nagarajan SA and Rahi M (2025) Life table variations in Wolbachia-transinfected (wMel & wAlbB strains) and uninfected Aedes aegypti: the role of various larval diets. Front. Insect Sci. 5:1679816. doi: 10.3389/finsc.2025.1679816

Received: 05 August 2025; Accepted: 19 November 2025; Revised: 06 November 2025;

Published: 12 December 2025.

Edited by:

Emma J. Hudgins, The University of Melbourne, AustraliaReviewed by:

Riccardo Moretti, Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development (ENEA), ItalyLi-Hsin Wu, National Pingtung University of Science and Technology, Taiwan

Copyright © 2025 Gunasekaran, Pachalil Thiruvoth, Annamalai, Balakrishnan, Nagarajan and Rahi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vidhya Pachalil Thiruvoth, dmlkaHlhbGVlbGE5MEBnbWFpbC5jb20=; cHQudmlkaHlhQGljbXIuZ292Lmlu

†Present address: Vijayakumar Balakrishnan, Division of Biostatistics, Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR)-National Institute for Research in Tuberculosis, Chennai, India

Yazhini Gunasekaran1

Yazhini Gunasekaran1 Vidhya Pachalil Thiruvoth

Vidhya Pachalil Thiruvoth Sakthivel Annamalai

Sakthivel Annamalai Vijayakumar Balakrishnan

Vijayakumar Balakrishnan Shriram Ananganallur Nagarajan

Shriram Ananganallur Nagarajan Manju Rahi

Manju Rahi