Abstract

Background:

The new antenatal care (ANC) contact model is recommended to be initiated within the first trimester of pregnancy, specifically before 12 weeks of gestation. The health of expectant mothers and the unborn children can be improved by early identification and treatment of preexisting and pregnancy-related conditions. However, in Ethiopia, there is limited evidence to support this. This study aimed to evaluate the extent of timely initiation, knowledge, attitude, and related aspects toward the new ANC contact model among pregnant women attending Munessa Health facilities.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study was carried out in a facility with 482 participants between April and May of 2024. The necessary sample was chosen by the use of a systematic sampling technique. Data were gathered from pregnant women who were visiting the prenatal care facility using an interviewer-administered questionnaire. Data were coded and entered using Epidata version 3.1 and analyzed by SPSS version 25. Binary and multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to identify possible determinants, and an odds ratio was used to measure the strength of associations at a p-value of <0.05.

Results:

The study revealed that 127 (26.5%) women initiated ANC on time. Generally, 215 (44.8%) pregnant women had a positive attitude toward and 83 (17.3%) of them had good knowledge of the new ANC contact model. Attending non-formal learning (AOR, 0.094, 95% CI 0.13, 0.56), being tested for pregnancy by urine (AOR, 6.4; 95% CI: 3.51, 12.03), having had no prior history of abortion (AOR = 0.47; 95% CI: 0.23, 0.97), and having no history of ANC complications (AOR = 0.076, 95% CI 0.03, 0.06) were significantly associated with the timely initiation of ANC contact.

Conclusion:

This study highlights the significance of exerting considerable effort to expand the coverage of timely ANC initiation. Consequently, raising mothers’ attitudes and level of awareness about ANC services and pregnancy hazard signals is crucial for expanding the coverage of timely ANC contact initiation.

Introduction

Antenatal care (ANC) is the term used to describe the treatment that expectant mothers receive from trained medical professionals during their pregnancy. It protects the health of pregnant women and their fetuses during the pregnancy (1). In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed a new ANC model to improve the quality of prenatal care. It is advised that prior to the gestational age of 12 weeks, each pregnant woman should begin her first ANC contact (2, 3). This model suggests a minimum of 8 ANC contacts, with the first contact occurring in the first trimester of gestation followed by the second and third trimesters2 and 5 contacts, respectively (2). There are more maternal and fetal evaluations when ANC is started on time. Pregnant women who undergo these evaluations are more likely to have a successful pregnancy because these assessments can detect complications and improve communication between health providers and pregnant women, increasing the likelihood of positive pregnancy outcomes (4). Evidence shows that starting ANC within the first trimester facilitates the adoption of preventive measures, the early detection of diseases, and the provision of relevant and up-to-date information (5). It can also encourage the integration of clinical practices, the provision of psychosocial and emotional support, the reduction of pregnancy-related complications, and the elimination of health inequalities (6). Initiating ANC visits during the first trimester provides the best opportunity for conveying the key components of maternity healthcare services and increasing retention within the maternity care pathway (6, 7). Even though early ANC initiation has been shown to have benefits, many pregnant women begin ANC later than is recommended. Globally, the ANC initiation rate is 58.6%, however it varies per continent. The estimated rates of early ANC visits are 84.8% in nations with high incomes and 48.1% in low-income countries (4). Within the first trimester, 38.0% of ANC visits occur in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). The percentage varies from 14.5% in Mozambique to 68.6% in Liberia (1, 8). In 2019, the Mini Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) revealed that just 28% of women received their first antenatal care visit in the first trimester. This rate also varies across geographic regions (9). Previous research revealed regional and intraregional variations in the prevalence and related variables. Moreover, differences in the interpretation of when to initiate ANC were noted (6, 7). Considering the differences of ANC initiation of the previous model, WHO recommended early initiation of ANC attendance, a minimum number of ANC contacts and a minimum standard of care for the effective operationalization of ANC services (8). According to published research, a number of variables are linked to when the first ANC encounter occurs. These include maternal age, women’s level of education, marital status, ethnicity, and women’s involvement in decision making (3, 10). Though, there are some existing studies on timely initiation of the previous focused ANC visit in Ethiopia and in Oromia as well, no studies have been conducted considering the WHO new model ANC contact in Ethiopia. Furthermore, given the range of socioeconomic characteristics of the study population that may affect the timing of ANC beginning, there aren’t many studies exploring the timely initiation of the new ANC model and its associated factors in the study settings (Munessa district). Therefore, the findings of this study assist stakeholders and health officials in creating public health policies and strengthening social and familial support networks for expectant mothers in their communities. Thus, the objective of this study was to assess the magnitude of timely initiation of a new ANC contact model, knowledge, attitude and its associated factors among pregnant women at Munessa District health facilities, Ethiopia.

Materials and methods

Study design, area and period

A cross-sectional study design based on quantitative data was carried out between April and May 2024 among pregnant women receiving ANC at medical facilities in Munessa district, Oromia Region, Ethiopia. Munessa is one of the districts in Arsi Zone, Oromia Region, and is located 236 km from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. In the district, there are 7 health centers, 1 primary hospital, and more than 162 health professions. There are 166,539 people living in this woreda as of the 2007 national census, with a 2.5% annual growth rate. Of these, 82,559 are men and 83,980 are women. One primary hospital and seven health centers exist in the woreda. Currently, around 8,748 pregnant women visit the hospital and health centers for ANC services per year.

Study source and study population

The source population consisted of all pregnant women who visited public ANC clinics in the Munessa area, while the study population consisted of all sampled pregnant women who visited public health facilities’ ANC clinics during the data collection period. Since it was believed that they would not be able to supply the required information, pregnant women with mental illnesses and those who were deaf or hard of hearing were not allowed to participate in the study.

Sample size

We used the single population proportion formula to determine the sample size with the following assumptions: the proportion of timely initiation of new model ANC contact was taken from the study conducted in Nigeria (24%) (8) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and a margin of error of 4%.

Considering a non-response rate of 10%, the sample size was 482 women who initiated ANC contact.

Sampling procedure

Using the simple random sampling method, four of the eight health facilities in the Munessa district were chosen. Before starting the study, the average monthly caseload of ANC visits at each chosen healthcare facility was evaluated. The population proportion to size for each chosen health facility was then used to determine the sample size for the study facilities. Finally, the study participants were questioned at each health facility either during the first or follow-up prenatal care. Consequently, N/n = 2 was used to determine the sampling frame and the total number of clients who received ANC from all institutions under study. A rigorous sampling strategy was used to interview every second client from all medical facilities. A random selection was made to interview the first client. As a result, the four chosen medical facilities had the following monthly client counts: Kersa Primary Hospital = 238; Kanchare Health Center = 64; Egoo Health Center = 83; and Kersa Health Center = 97.

Data collection tool and quality control

A structured interviewer-administered questionnaire adapted from different literatures was used to collect the data (2, 3, 8). After being created in English, the tool was translated into Afaan Oromo, the local language, and then back into English by professionals to ensure consistency (reliability). Also, we used the Cronbach’s alpha to check the internal consistency of the multiple questions and scales of the tool (0.71 and 0.8 respectively). Four qualified data collectors with bachelor’s degrees in midwifery were recruited to fill the tools, and two midwives having master’s degree in clinical midwifery were recruited to supervise the data collection process. To avoid conflict of interest during the data collection process the data collectors and supervisors were recruited from the study sites. Data collectors and supervisors who took part in the pre-test and data collection received 2 days of training. To ensure the validity of the instrument, questions and ambiguities noted in the questionnaire were discussed after the pretest was completed. Following the conclusion of the pre-test, the questionnaire was finally revised. The supervisor and the lead investigator closely monitored and controlled the daily data collection. As the process progressed, data entry and code were verified. After data entry was complete, data cleaning was done.

Variables

Dependent variable

The dependent variable is the timely initiation of ANC new model contact.

Independent variables

Sociodemographic factors such as age, educational status, marital status, occupation of respondents, monthly income, place of residence, religion, ethnicity, and husbands’ educational status and occupation, pregnancy-related variables (such as the number of deliveries, gravidity, and abortion history), types of pregnancy and means of recognizing pregnancy, and knowledge of women related to ANC visits are the independent variables.

Operational definition

Timely initiation of new model ANC contact

This means that the first antenatal contact was before 12 weeks (during the first trimester) (2).

Knowledge regarding ANC service

It was assessed using 10 items, with a correct answer being given a score of “1” and an incorrect answer being given a score of “0.” Respondent’s overall knowledge was categorized, using a modified Bloom’s cut-off point, as good if the score was between 80 and 100%, moderate if the score was between 50 and 79%, and poor if the score was less than 50% (4).

Attitude on new ANC model

To measure the attitude level, 10 statements with 5-point Likert scale agreement options were used. Marks ranged from 1 to 5. There was a minimum of 10 and a maximum of 50 available points.

Data analysis

After data were entered using Epi-Data version 3.1, it was exported to the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 25.0 program for analysis. The main findings were compiled and presented using frequency and proportion. To choose candidate variables for the multivariable logistic regression, a bivariate logistic regression analysis was first used. The variables in the multivariable logistic regression model were those with a p-value of ≤ 0.25 in the bivariate logistic regression analysis. In order to adjust for potential confounders and identify the independent related factors of the outcome variable, it was carried out. An odds ratio was accepted at a 95% CI, and a p-value of < 0.05 was stated as statistically significant. Model fitness was checked by the Hosmer and Lomeshow goodness-of-fit tests (p-value = 0.773). Collinearity between independent variables was checked by taking the variance inflation factor (VIF) 10 as the cut point. In this case, VIF was 7.1. Finally, graphs, tables, and charts were used to present both the descriptive and analytical results accordingly.

Ethical approval and clearance

The Institutional Review Board of Arsi University College of Health Sciences granted ethical permission (Number A/U/H/S/120/239/2015). Additionally, the healthcare facilities provided their legal consent. The goal and purpose of the study, as along with the freedom to discontinue participation at any moment, were explained to respondents. Written consent was then acquired from each respondent. For study participants under the age of 18, informed consent was acquired from a parent or guardian. Confidentiality was preserved by excluding personal identifiers such as names and addresses from the study.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

Out of 482 study samples only 480 (99.6% response rate) pregnant women responded in the study. The mean age of the respondents was 27.2 years (± 6.6 years), with approximately 37.7% of the women in the 25–29 age range. The respondents’ ethnic identity was Oromo (89.6%) and religion was Islam (62.1%). Nine out of ten pregnant women had completed primary education or above, and 99.4% of the participants were married. Regarding their occupation 56.1% pregnant women were housewives and 72.5% were rural residents, whereas 63.5% participants were located within a 30-min distance from the health facilities (Table 1).

Table 1

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of participant in years | 15–19 | 47 | 9.8 |

| 20–24 | 133 | 27.7 | |

| 25–29 | 181 | 37.7 | |

| 30–39 | 97 | 20.2 | |

| 40–49 | 22 | 4.6 | |

| Marital status | Single | 1 | 0.2 |

| Married | 477 | 99.4 | |

| Divorced | 2 | 0.4 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 158 | 32.9 |

| Catholic | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Muslim | 298 | 62.1 | |

| Protestant | 23 | 4.8 | |

| Ethnicity | Oromo | 430 | 89.6 |

| Amhara | 44 | 9.2 | |

| Gurage | 6 | 1.2 | |

| Mother’s education level | No education /never attended | 70 | 14.6 |

| Primary | 255 | 53.1 | |

| Secondary | 123 | 25.6 | |

| Higher | 32 | 6.7 | |

| Mother’s occupation | Housewife | 271 | 56.4 |

| Employee | 56 | 11.7 | |

| Merchant | 30 | 6.3 | |

| Student | 3 | 0.6 | |

| Farmer | 120 | 25.0 | |

| Husband’s occupation | Private employee | 82 | 17.1 |

| Government employee | 75 | 15.6 | |

| Merchant | 35 | 7.3 | |

| Student | 6 | 1.3 | |

| Farmer | 282 | 58.2 | |

| Area of residence | Rural | 348 | 72.5 |

| Urban | 132 | 27.5 | |

| Distance from ANC service (h) | Less than 30 min | 305 | 63.5 |

| 30 min-1 h | 143 | 29.8 | |

| More than 1 h | 32 | 6.7 | |

| Family monthly income (Ethiopian birr) | 1,651–3,200 | 7 | 1.5 |

| 3,200–5,250 | 269 | 56 | |

| 5,251–7,800 | 179 | 37.3 | |

| 7,801–10,900 | 19 | 4.0 | |

| ≥10,900 | 6 | 1.3 |

Sociodemographic characteristics of pregnant mothers at Munessa health facilities.

Obstetrics history of the respondents

Among pregnant mothers interviewed, the majority, i.e., 396 (82.5%), of them had more than one previous pregnancy and 99 (20.6%) had a history of abortions. Nearly 186 (38.7%) pregnant women had three or more children alive, and 92 (19.2%) pregnant women had a history of adverse pregnancy outcome. Ninety-two (19.2%) women had experienced pregnancy-related complications. In terms of current pregnancies, 293 (61%) women have planned to become pregnant. A urine test confirming pregnancy by measuring the HCG hormone revealed a value of 151 (31.5%).

Timing of first ANC contact initiation

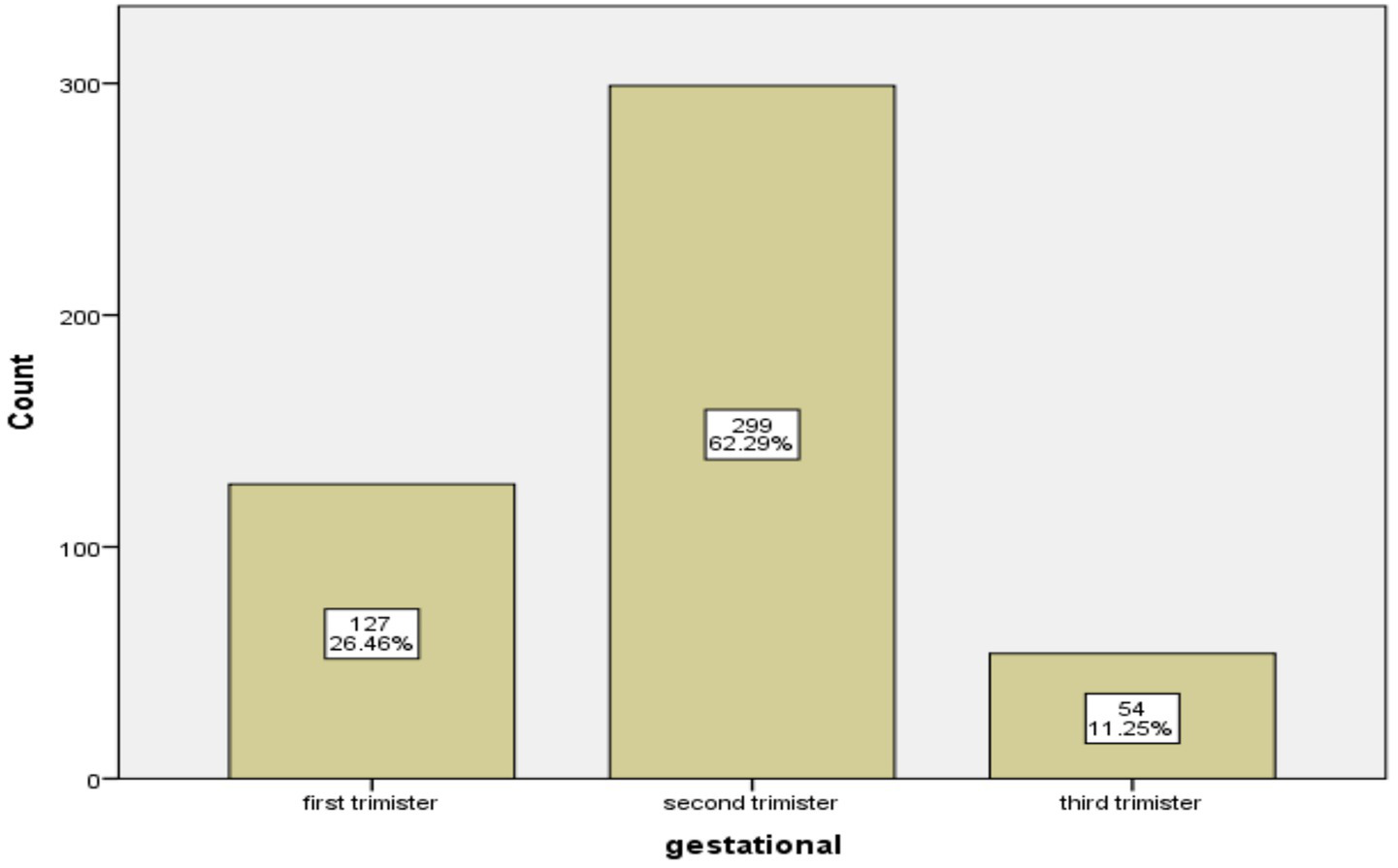

Nearly 127 (26.5%) pregnant women started their first ANC contact on time (less than 12 weeks of gestation). The first ANC appointment was scheduled between 7 and 40 weeks of pregnancy, and the average ANC visit time was 20.2 weeks (± 7.2 weeks). In the second trimester, 299 pregnant women (62.3%) began their first ANC initiation (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Distribution of first ANC contact among pregnant mothers in public health facilities of Munessa district (n = 480).

Attitude toward the new ANC contact model

All respondents (100%) believe that all pregnant women should have ANC follow-up. Nearly 61.7% of the pregnant women perceived that eight ANC visits were better than four ANC visits for pregnancy and the fetus. A majority of respondents (98.4%) believe that husbands should be present during ANC contact, and 456 (95.1%) believed that ANC contact could reduce prenatal and postnatal problems. The majority of women (97.1%) strongly agree that iron and folic acid supplementation for all pregnant women is necessary, and 98.1% of the respondents perceived that having an ultrasound check-up is mandatory before 24 weeks. Overall, 215 (44.8%) pregnant women had a positive attitude toward ANC contact and timely ANC initiation, while 265 (55.2%) pregnant women had a negative attitude (Table 2).

Table 2

| ANC is highly important to the health of the mother | Strongly agree | 472 | 98.3 |

| Agree | 8 | 1.7 | |

| ANC is highly important to the health of the fetus | Strongly agree | 406 | 84.6 |

| Agree | 7 | 1.5 | |

| Neutral | 53 | 11.0 | |

| Disagree | 14 | 2.9 | |

| Antenatal booking is necessary for women before the 3rd month of pregnancy. | Strongly agree | 323 | 67.3 |

| Agree | 26 | 5.4 | |

| Neutral | 131 | 27.3 | |

| Pregnant women need to come for eight ANC contacts | Strongly agree | 299 | 62.3 |

| Agree | 20 | 4.2 | |

| Neutral | 160 | 33.3 | |

| Disagree | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Eight ANC contacts better than four ANC visits for pregnancy and fetus | Strongly agree | 272 | 56.7 |

| Agree | 24 | 5.0 | |

| Neutral | 161 | 33.3 | |

| Disagree | 23 | 4.8 | |

| Supplying iron and folic acid is good for the mother and fetus | Strongly agree | 4.6 | 95.4 |

| Agree | 8 | 1.7 | |

| Neutral | 14 | 2.9 | |

| All pregnant women should have ANC follow-up | Strongly agree | 472 | 98.3 |

| Agree | 8 | 1.7 | |

| Over all attitude | Positive attitude | 215 | 44.8 |

| Negative attitude | 265 | 55.2 |

Attitudes of respondents toward the ANC contact model at Munesa.

Knowledge toward the new ANC contact model

The definition of prenatal care was understood by nearly 73.3% of mothers, and 99.6% were aware of the significance of ANC for both the mother’s and the fetus’s health. However, only 24.5% of them were aware that ANC should begin within 12 weeks. Three hundred ninety-one (81.5%) pregnant women knew that ANC contact decreases maternal and fetal complications. Nearly 48.1% of women knew the correct time for an ultrasound scan, while 81% of them knew the recommended period of iron and folic acid (IFA) supplementation. Overall, in terms of participants’ knowledge of the new ANC contact model, 192 (40%) had good knowledge, 48 (10%) had moderate knowledge and 240 (50%) had poor knowledge level (Table 3).

Table 3

| Variable | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition of Antenatal care ANC | Yes | 352 | 73.3 |

| No | 128 | 26.7 | |

| ANC is highly important to the health of the mother and the fetus | Yes | 478 | 99.6 |

| No | 2 | 0.4 | |

| ANC booking before 12 weeks | Yes | 118 | 24.5 |

| No | 362 | 75.5 | |

| Number of ANC contacts (eight contacts) | Yes | 32 | 6.7 |

| No | 448 | 93.3 | |

| Pregnant women need to come for at least eight antenatal checks throughout her pregnancy | Yes | 27 | 5.6 |

| No | 453 | 94.4 | |

| ANC contact decreases antenatal and postnatal complications | Yes | 391 | 81.5 |

| No | 89 | 18.5 | |

| Husbands should be present during the ANC contact | Yes | 448 | 93.3 |

| No | 92 | 6.7 | |

| Service given in ANC contacts | Yes | 89 | 18.5 |

| No | 391 | 81.5 | |

| Gestational age of Ultrasound scan done less than 24 weeks | Yes | 231 | 48.1 |

| No | 249 | 51.9 | |

| Gestational age of IFA supplementation is less than 12 weeks | Yes | 389 | 81.0 |

| No | 91 | 19.0 | |

| Knowledge level toward ANC service | Good knowledge | 192 (40%) | |

| Moderate knowledge | 48 (10%) | ||

| Poor knowledge | 240 (50%) | ||

Knowledge of respondents on ANC contact model at Munessa health facilities.

Factors associated with the timely initiation of the new ANC contact model

Both the bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses, as shown in Table 4, revealed significant associations with mothers’ educational level, history of abortion, adverse pregnancy, prior pregnancy difficulties, and pregnancy confirmation methods. Women with no formal education and those with only primary education had 90.6 and 76%, respectively, lower odds of initiating ANC on time compared to women with higher education (AOR = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.13–0.67; and AOR = 0.24, 95% CI: 0.073–0.84). Respondents who confirmed their current pregnancy using a urine test were 6.4 times more likely to initiate ANC on time compared to those who confirmed it by a missed menstrual period (AOR = 6.4, 95% CI: 3.51–12.03). Conversely, pregnant women without a history of abortion were 53% less likely to initiate ANC early compared to those with a history of abortion (AOR = 0.47, 95% CI: 0.23–0.97). Mothers who experienced adverse effects during pregnancy were five times more likely to initiate ANC on time compared to those without such effects (AOR = 5.09, 95% CI: 2.58–10.03). In contrast, women with a history of normal previous pregnancy had 92.4% lower odds of timely ANC initiation compared to those who experienced complications in a previous pregnancy (AOR = 0.076, 95% CI: 0.03–0.16) (Table 4).

Table 4

| Variable | Timing of ANC initiation | Odds ratio with 95% CI | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | COR | AOR | |||

| Educational status of the mother | No formal education | 9 | 61 | 0.13 (0.04, 0.34) | 0.94 (0.13, 0.67)* | 0.019 |

| Primary | 68 | 187 | 0.32 (0.15, 0.67) | 0.24 (0.073, 0.84)* | 0.026 | |

| Secondary | 36 | 87 | 0.36 (0.16, 0 0.80) | 0.33 (0.10, 1.302) | 0.079 | |

| Higher | 17 | 15 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Educational status of the husband | No formal education | 4 | 39 | 0.14 (0.04, 0.44) | 1.11 (0.11, 11.49) | 0.99 |

| Primary | 57 | 167 | 0.49 (0.298, 0.80) | 1.62 (0.63, 4.175) | 0.31 | |

| Secondary | 28 | 85 | 0.47 (0.26, 0.85) | 0.91 (0.35, 2.38) | 0.71 | |

| Higher | 41 | 59 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Residence | Rural | 76 | 272 | 1 | 1 | |

| Urban | 54 | 78 | 2.47 (1.61, 3.81) | 1.36 (0.66, 2.33) | 0.39 | |

| Distance from ANC service in hour | Less than 30 min | 98 | 207 | 1 | 1 | |

| 30 min–1 h | 27 | 116 | 0.49 (0.30, 0.79) | 0.98 (0.430, 2.25) | 0.97 | |

| More than 1 h | 5 | 27 | 0.39 (0.146, 1.04) | 0.86 (0.16, 4.50) | 0.86 | |

| Media access | Yes | 109 | 209 | 3.50 (2.095, 5.85) | 1.38 (0.61, 3.13) | 0.43 |

| No | 21 | 141 | 1 | 1 | ||

| History of abortion | Yes | 53 | 46 | 1 | 1 | |

| No | 77 | 304 | 0.22 (0.13, 0.35) | 0.47 (0.23, 0.97)* | 0.04 | |

| Adverse effects of pregnancy | Yes | 61 | 31 | 9.09 (5.49, 15.06) | 5.09 (2.58, 10.03)* | 0.001 |

| No | 69 | 319 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Previous pregnancy complication | No | 58 | 330 | 0.04 (0.02, 0.08) | 0.076 (0.03, 0.16)* | 0.001 |

| Yes | 72 | 20 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Planned pregnancy | Planned | 107 | 186 | 4.1 (2.49, 6.74) | 1.73 (0.73, 4.06) | 0.20 |

| Unplanned | 23 | 164 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Received information on ANC | Yes | 80 | 123 | 2.95 (1.94, 4.47) | 1.41 (0.694, 2.89) | 0.33 |

| No | 50 | 227 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Methods of pregnancy confirmation | Missed period | 55 | 274 | 1 | 1 | |

| By urine test | 75 | 76 | 4.91 (3.19, 7.56) | 6.42 (3.51, 12.03)* | 0.001 | |

Factors associated with timely new model ANC initiation at Munesa (n = 480).

*shows a significant of p < 0.05.

Discussion

Timely initiation of ANC is a key strategy for meeting the new ANC model guidelines (the WHO’s 2016 recommendation) for a positive pregnancy experience (4). In this study, the prevalence of timely initiation of the new ANC contact model was observed to be 26.5%, which was similar to the rates reported in studies conducted in Hawasa (21.71%) (11) and Southwest Ethiopia, Illu Aba Bor zone (28.8%) (12). By contrast, a lower prevalence of timely initiation of ANC was observed in this study compared to those of studies conducted in Bahir Dar (48.6%) (6), Hosanna (34.3%) (4), Agaro (41.9%) (7), and Jimma (48%) cities of Ethiopia (10). It is possible that the greater percentages of timely ANC initiation resulted from the earlier research being carried out in a town district, where women are more knowledgeable about maternal health services. The fact that much of the earlier research concentrated on the ANC visit may possibly help to explain this discrepancy. The study revealed that most pregnant women had limited knowledge and a negative attitude toward the new ANC contact model and the correct timing of ANC initiation. Providing appropriate counseling on the recommended timing of ANC visits could encourage mothers to initiate care on time; when informed about the proper starting point, they are more likely to follow the guidance received. The results of this study also show that the prevalence of timely initiation of ANC services was lower compared to those in other countries, such as Benin (45.6%) (13), Ghana (68.0%) (14) and Uganda (50%) (15). This variation may be attributed to differences in socioeconomic status, access to services, and awareness levels. It could also be influenced by disparities in study settings and sample sizes. According to this study, ANC initiation at the WHO-recommended period (the first 12 weeks of pregnancy) was more common among women with secondary or higher education than among those without formal education. This may be explained by the fact that women who receive formal education are more likely to use appropriate maternity and child healthcare since they have a greater understanding of multiple aspects of health. This finding is also in line in with previous studies conducted in Hosana, Tigray, and Gahana (4, 14, 16). In addition, the greater likelihood of employment and higher income among educated women may provide them with better opportunities to access information and maternal health services compared to their less educated counterparts.

The likelihood of starting ANC on time was 6.4 times higher for respondents who used a urine test to establish their pregnancy than for those who relied on a missed menstrual period. This result aligns with an earlier study carried out in Southwest Ethiopia (7). This association may be due to urine tests being conducted at medical facilities, where women are often enrolled in ANC upon pregnancy confirmation. Early confirmation likely motivates women to initiate ANC sooner, as they become more aware of their pregnancy status. This study found that pregnant women without a history of abortion were 53% less likely to initiate ANC early compared to those with a prior abortion. This may be because women who have experienced previous pregnancy complications are more cautious and more likely to seek care earlier. This finding is consistent with results from the University of Gondar Hospital (17). This might be due to the fact that women who have experienced previous abortions may have a higher awareness of the importance of early ANC. They may understand the potential risks and complications associated with pregnancy and want to ensure they receive appropriate medical attention as soon as possible, and they may have learned from their previous experience that early detection and management of any potential issues can lead to better outcomes for both the mother and the baby (6). Furthermore, in this study, the odds of timely initiation of ANC were five times higher in mothers who had adverse effects of pregnancy as compared to those who had no adverse effects of pregnancy. This is supported by a study conducted in Ethiopia (18). The reason for this association might be that mothers who have experienced adverse effects and pregnancy complications during a previous pregnancy may have emotional and psychological factors that motivate them to seek timely initiation of ANC. Additionally, they may experience concerns or anxieties stemming from their previous pregnancy and seek to ensure they receive appropriate care and support during their current pregnancy.

Limitations of the study

This study identified the magnitude and factors associated with timely initiation of the new ANC model; however, its cross-sectional design limits causal inference. Excluding women attending private health facilities affects generalizability, and a lack of similar studies in Ethiopia limits comparison. Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable insights into late ANC initiation and its associated factors in the study population.

Conclusion

Most women in this study initiated their first ANC contact late. Key factors associated with delayed initiation included maternal education, history of abortion, pregnancy complications, and method of pregnancy confirmation. Overall, the finding that low maternal education and poor knowledge of the new WHO ANC contact schedule are significant barriers to timely ANC initiation has direct and specific implications for guiding health policy, intervention design, and health worker training in the Munessa district. Strengthening health education and community support systems is recommended, and the findings can inform policymakers and stakeholders in improving maternal health services by enhancing early ANC mode initiation.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was obtained from Institutional Review Board of Arsi University College of Health Sciences (Number A/U/H/S/120/239/2015). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants rovided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

EH: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GM: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to forward our deepest gratitude to Arsi zone and Munessa district health bureau for the permission and information they provided us. Very special thanks go to all study participants for their willingness and for the time they devoted to provide the information required for the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

ANC, Antenatal Care; AOR, Adjusted Odds Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval; HCG, Human Chorionic Gonadotropin; OR, Odd Ratio.

References

1.

Alem AZ Yeshaw Y Liyew AM Tesema GA Alamneh TS Worku MG et al . Timely initiation of antenatal care and its associated factors among pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa: a multicountry analysis of demographic and health surveys. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0262411–7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0262411

2.

WHO . Recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience: evidence base. Geneva: WHO (2016).

3.

Daniels-Donkor SS Afaya A Daliri DB Laari TT Salia SM Avane MA et al . Factors associated with timely initiation of antenatal care among reproductive age women in the Gambia: a multilevel fixed effects analysis. Arch Public Health. (2024) 82:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13690-024-01247-y

4.

Tessema D Kassu A Teshome A Abdo R . Timely initiation of antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women attending at Wachemo university Nigist Eleni Mohammed memorial comprehensive specialized hospital, Hossana, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. J Pregnancy. (2023) 2023:4381. doi: 10.1155/2023/7054381

5.

Lattof SR Moran AC Kidula N Moller AB Jayathilaka CA Diaz T et al . Implementation of the new WHO antenatal care model for a positive pregnancy experience: a monitoring framework. BMJ Glob Health. (2020) 5:1–11. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002605

6.

Ambaye E Regasa ZW Hailiye G . Early initiation of antenatal care and its associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care at public health centres in Bahir Dar Zuria zone, Northwest Ethiopia, 2021: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2023) 13:e065169–7. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-065169

7.

Redi T Seid O Bazie GW Amsalu ET Cherie N Yalew M . Timely initiation of antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Southwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0273152–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0273152

8.

Fagbamigbe AF Olaseinde O Fagbamigbe OS . Timing of first antenatal care contact, its associated factors and state-level analysis in Nigeria: a cross-sectional assessment of compliance with the WHO guidelines. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e047835–14. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047835

9.

EDHS . Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) [Ethiopia] and ICF Ethiopia mini demographic and health survey: final report. Rockville, Maryland, USA: EPHI and ICF (2019).

10.

Tadele F Getachew N Fentie K Amdisa D . Late initiation of antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women in Jimma zone public hospitals, Southwest Ethiopia, 2020. BMC Health Serv Res. (2022) 22:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08055-6

11.

Geta MB Yallew WW . Early initiation of antenatal care and factors associated with early antenatal care initiation at health facilities in southern Ethiopia. Adv Public Health. (2017) 2017:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2017/1624245

12.

Tola W Negash E Sileshi T Wakgari N . Late initiation of antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic of Ilu Ababor zone, Southwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0246230–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246230

13.

Ekholuenetale M Nzoputam CI Barrow A Onikan A . Women’s enlightenment and early antenatal care initiation are determining factors for the use of eight or more antenatal visits in Benin: further analysis of the demographic and health survey. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. (2020) 95:13. doi: 10.1186/s42506-020-00041-2

14.

Anaba EA Afaya A . Correlates of late initiation and underutilisation of the recommended eight or more antenatal care visits among women of reproductive age: insights from the 2019 Ghana malaria indicator survey. BMJ Open. (2022) 12:1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-058693

15.

Dunn AM Hofmann OS Waters B Witchel E (2011). Cloaking malware with the trusted platform module. Available online at: https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenix-security-11/cloaking-malware-trusted-platform-module (Accessed April 10, 2024).

16.

Gebresilassie B Belete T Tilahun W Berhane B Gebresilassie S . Timing of first antenatal care attendance and associated factors among pregnant women in public health institutions of Axum town, Tigray, Ethiopia, 2017: a mixed design study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. (2019) 19:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2490-5

17.

Belayneh T Adefris M Andargie G . Previous early antenatal service utilization improves timely booking: cross-sectional study at university of Gondar hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. J Pregnancy. (2014) 2014:132494. doi: 10.1155/2014/132494

18.

Shewaye M Cherie N Molla A Tsegaw A Yenew C Tamiru D et al . A mixed-method study examined the reasons why pregnant women late initiate antenatal care in Northeast Ethiopia. PLoS One. (2023) 18:e0288922–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0288922

Summary

Keywords

antenatal care contact, knowledge, new model, pregnant women, timely initiation

Citation

Hailu E, Bekele D and Megersa G (2025) Timely initiation of new antenatal care contact model and its associated factors among pregnant women at Munessa health facilities, Ethiopia: a facility-based cross-sectional study. Front. Med. 12:1532041. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1532041

Received

21 November 2024

Revised

23 October 2025

Accepted

14 November 2025

Published

02 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Monica Ewomazino Akokuwebe, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

Reviewed by

Eddie-Williams Owiredu, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United States

Narila Mutia Nasir, Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University Jakarta, Indonesia

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Hailu, Bekele and Megersa.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniel Bekele, bekeled46@gmail.com

ORCID: Daniel Bekele, orcid.org/0000-0002-8688-9386

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.