- 1Department of Ophthalmology, The Second Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, China

- 2Jilin Provincial Engineering Laboratory of Ophthalmology, Changchun, China

Background: Age-related eye diseases are the main causes of progressive and irreversible vision loss in aging populations worldwide. Carotenoids, as a group of common natural antioxidants, can suppress free radicals produced by complex physiological reactions, thereby protecting the eyes from the effects of oxidative stress, cell apoptosis, and mitochondrial dysfunction. The present study aims to explore the association between serum carotenoid concentrations and risk of major age-related eye diseases among middle-aged and older adults in the United States.

Methods: This study involved 1,478 participants aged ≥50 years from the 2005–2006 cycles of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Multivariate logistic regression was used to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of prevalence of cataract, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and age-related macular degeneration (AMD) in relation to serum carotenoid concentrations.

Results: Compared to participants in the first quartile, those in highest quartile of serum α-carotene (OR: 0.37; 95% CI: 0.21–0.64), β-carotene (OR: 0.57; 95% CI: 0.33–0.95), lutein/zeaxanthin (OR: 0.45; 95% CI: 0.27–0.76), and total carotenoid (OR: 0.58; 95% CI: 0.35–0.97) were negatively associated with risk of cataract; those in highest quartile of serum β-carotene (OR: 0.30; 95% CI: 0.11–0.77) and β-cryptoxanthin (OR: 0.28; 95% CI: 0.12–0.68) were negatively associated with risk of diabetic retinopathy; and those in highest quartile of lycopene (OR: 0.37; 95% CI: 0.18–0.78) was negatively associated with risk of AMD. In addition, subgroup analysis results indicated that participants in highest quartile of serum α-carotene (OR: 0.16; 95% CI: 0.08–0.32), β-carotene (OR: 0.40; 95% CI: 0.21–0.75), lycopene (OR: 0.46; 95% CI: 0.24–0.87), lutein/zeaxanthin (OR: 0.45; 95% CI: 0.25–0.84), and total carotenoid (OR: 0.41; 95% CI: 0.22–0.77) concentrations were negatively associated with risk of any ocular disease among female participants. By contrast, no associations were observed among male participants.

Conclusion: Our study demonstrated that higher serum concentrations of carotenoids were negatively associated with the risk of age-related eye diseases, particularly among middle-aged and older female participants.

1 Introduction

With the rapid growth of middle-aged and older adult populations, the prevalence of common age-related eye diseases has increased, including cataract, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and age-related macular degeneration (AMD), which are the main causes of progressive and irreversible vision loss in aging populations worldwide (1–3). Globally, 285 million people have moderate to severe visual impairment or blindness, of whom 65% of the visually impaired and 82% of all blind people are aged 50 or older (4). In the United States, the prevalence of most eye diseases increases with age among individuals aged ≥50 years, and such diseases impose a substantial socioeconomic burden (5). Furthermore, age-related eye diseases can reduce the quality of life of older adults and independently increase their mortality (6–8). Because of their overall health implications, age-related eye diseases are a major health concern among middle-aged and older adults, and new strategies for preventing or delaying disease progression must be identified.

Studies have reported that the cells of the tissues of the eyes are sensitive to oxidative stress, triggering and exacerbating age-related ocular abnormalities (9). Carotenoids are a group of common natural antioxidants and fat-soluble phytochemicals that are synthesized only by specific microorganisms and plants (10, 11). To the best of our knowledge, α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, lutein, and zeaxanthin account for more than 95% of the carotenoids in circulation (11, 12). Because ocular carotenoids absorb light in the visible light region, they protect the retina and lens from the potential photochemical damage caused by light exposure (13, 14). Carotenoids can also suppress the free radicals produced by complex physiological reactions, thereby protecting the eyes from the effects of oxidative stress, cell apoptosis, mitochondrial dysfunction, and inflammation (13). Several previous studies have reported that dietary carotenoid supplementation had a potential beneficial association with reduced risk of cataract, preserved macular health in glaucoma and promoted retinal health, and improved visual function in diabetic retinopathy (15–18). In addition, the Age-Related Eye Diseases Study (AREDS) Research Group demonstrated that dietary lutein/zeaxanthin supplementation was significantly associated with late AMD progression and can serve as an appropriate replacement for beta carotene, which increased the risk of lung cancer (19, 20).

To date, the majority of previous studies have focused on the association between dietary carotenoid intake and eye diseases (21, 22), whereas epidemiological evidence regarding the relationship between serum carotenoid concentrations and the risk of age-related eye diseases remains limited. Serum concentrations provide a direct measure of absorbed, metabolically processed carotenoids, reflecting interindividual differences in digestion, absorption, and metabolism that dietary assessments cannot capture. A cross-sectional study demonstrated that a higher concentration of serum α-carotene is associated with a lower risk of diabetic retinopathy (23). Furthermore, higher blood concentrations of α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, and lutein/zeaxanthin are associated with a lower risk of cataract among individuals aged ≥50 years (24). A case–control study reported that higher serum concentrations of carotenoids, particularly zeaxanthin and lycopene, were associated with a lower likelihood of developing exudative AMD in an older Chinese population (25). Notably, most of the aforementioned studies have mainly focused on the association between the serum carotenoid concentration and single eye diseases in Asian populations. To date, few studies have comprehensively explored the association between serum carotenoids and various age-related eye diseases among populations in the United States.

In the present population-based cross-sectional study, we examined the association of the serum carotenoid concentration with the risk of major age-related eye diseases, including cataract, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and AMD, in a nationally representative sample of the middle-aged and older adult population in the United States.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study population

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is an ongoing cross-sectional study conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to assess the health and nutritional status of a nationally representative sample of the civilian population in the United States. Data from the 2005–2006 cycle of the NHANES were used for this analysis. The protocols for the NHANES study were approved by the Research Ethics Review Board of the NCHS. Each participant provided written informed consent.

In the NHANES 2005–2006, there were a total of 10,348 participants, and the present analysis was limited to 2,214 participants aged 50 and older. We excluded participants with missing data for serum carotenoid concentrations (n = 220) and major eye diseases (n = 516), including cataract, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and AMD. Finally, 1,478 participants were included in the present study.

2.2 Assessment of carotenoids

Serum carotenoids, including α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, and lutein/zeaxanthin, were quantified at the CDC’s National Center for Environmental Health using validated high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with multiwavelength photodiode-array absorbance detection. The laboratory procedures involved mixing serum with a buffer and ethanol containing internal standards—retinyl butyrate and nonapreno-beta-carotene (C45)—followed by extraction into hexane. The combined hexane extracts were then redissolved in ethyl acetate, diluted in mobile phase, and injected onto a C18 reversed-phase column for isocratic elution. Carotenoids were detected by absorbance at 450 nm. The coefficient of variation (CV) was generally below 5% for β-carotene and below 20% for minor carotenoids. Total serum carotenoid concentration was calculated as the sum of the five individual carotenoids. Detailed quality control methods and analytical protocols have been described elsewhere (12, 26).

2.3 Assessment of major eye disease

The NHANES database provided retinal imaging results, which were used to examine the presence of diabetic retinopathy and AMD. Diabetic retinopathy was determined by any signs of retinopathy and the diagnosis of diabetes (27). Based on the fundus photographs, the retinopathy was graded by four levels, including no retinopathy, mild non-proliferative retinopathy (NPR), moderate, or severe NPR. Diabetes was defined as a self-report of a previous diagnosis of the disease or a hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level≥6.5% according to the American Diabetes Association’s diagnostic criteria for diabetes (28). According to the modified Wisconsin Age-Related Maculopathy Grading Classification Scheme, early AMD is defined by the presence or absence of drusen and/or pigmentary abnormalities; late AMD is defined by exudative AMD signs and/or geographic atrophy. In the present study, participants were divided into two groups: no AMD and AMD. A range of quality control measures was implemented to ensure the accuracy and reliability of retinal image grading. Fundus images were assessed by a team of nine trained graders, including a preliminary grading coordinator, two preliminary graders, and six detail graders. Grading was conducted in a semi-quantitative manner using EyeQ Lite software, with high-resolution monitors for detailed evaluation. The process involved three stages: an initial review for detectable pathology, preliminary grading, and detailed grading. Each image was independently evaluated by at least two graders. In case of disagreement, the image was evaluated by an adjudicator who made a final decision. Further details are available in the NHANES Digital Grading Protocol.

Furthermore, NHANES provided self-reported personal interview data on vision status, including cataract and glaucoma. The cataract status in all participants was based on their answers to the question, “Have you ever had a cataract operation?” Glaucoma was defined by the question: “Have you ever been told you had glaucoma, sometimes called high pressure in eyes?” The questions were asked using the Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing system (CAPI), which was programmed with built-in consistency checks to reduce data entry errors.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of continuous variables and numbers (percentages) of categorical variables. Demographic characteristics between quartiles of serum total carotenoid concentrations were compared by one-way ANOVA tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categoric variables. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of prevalence of cataract, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and AMD in relation to serum carotenoid concentrations. p-values for trend were obtained by including the quartile number as a continuous variable in the regression model. The multivariate adjusted model was adjusted for age (continuous), sex (male or female), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, black, Mexican-American, other Hispanic, or other race/ethnicity), education level (less than high school, high school or equivalent, college or above, or missing), family income-to-poverty ratio (FIR) (<1.3, 1.3 to ≤3.5, >3.5, or missing), body mass index (BMI) (<18.5, 18.5 to <25, 25 to <30, ≥30 kg/m2, or missing), drinking status (non-drinker or drinker), smoking status (never smoker, former smoker, current smoker, or missing), HbA1c (<6.5%, ≥6.5%, or missing), hypertension (yes, no, or missing), and hypercholesterolemia (yes, no, or missing). We selected these confounders on the basis of their associations with the outcomes of interest or a change in the effect estimate of more than 10% (29, 30). Model goodness-of-fit was assessed using Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and residual plots. We used the restricted cubic spline regression models to investigate dose–response associations between serum α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, lutein/zeaxanthin, and total carotenoid concentrations and risk of any ocular disease. Sensitivity analyses by excluding participants with missing data on covariates were also conducted. Furthermore, interaction and stratified analyses were conducted according to sex (male vs. female) and smoking status (never smoker vs. former or current smoker), and P for interaction was calculated using the likelihood ratio test. Significance for pre-specified subgroup interactions (sex and smoking status) was assessed using a Bonferroni-corrected threshold of a p-value of < 0.025 to account for multiple testing. All statistical analyses were conducted using R Statistical Software (Version 4.2.2).

3 Results

3.1 Demographic characteristics of the study participants

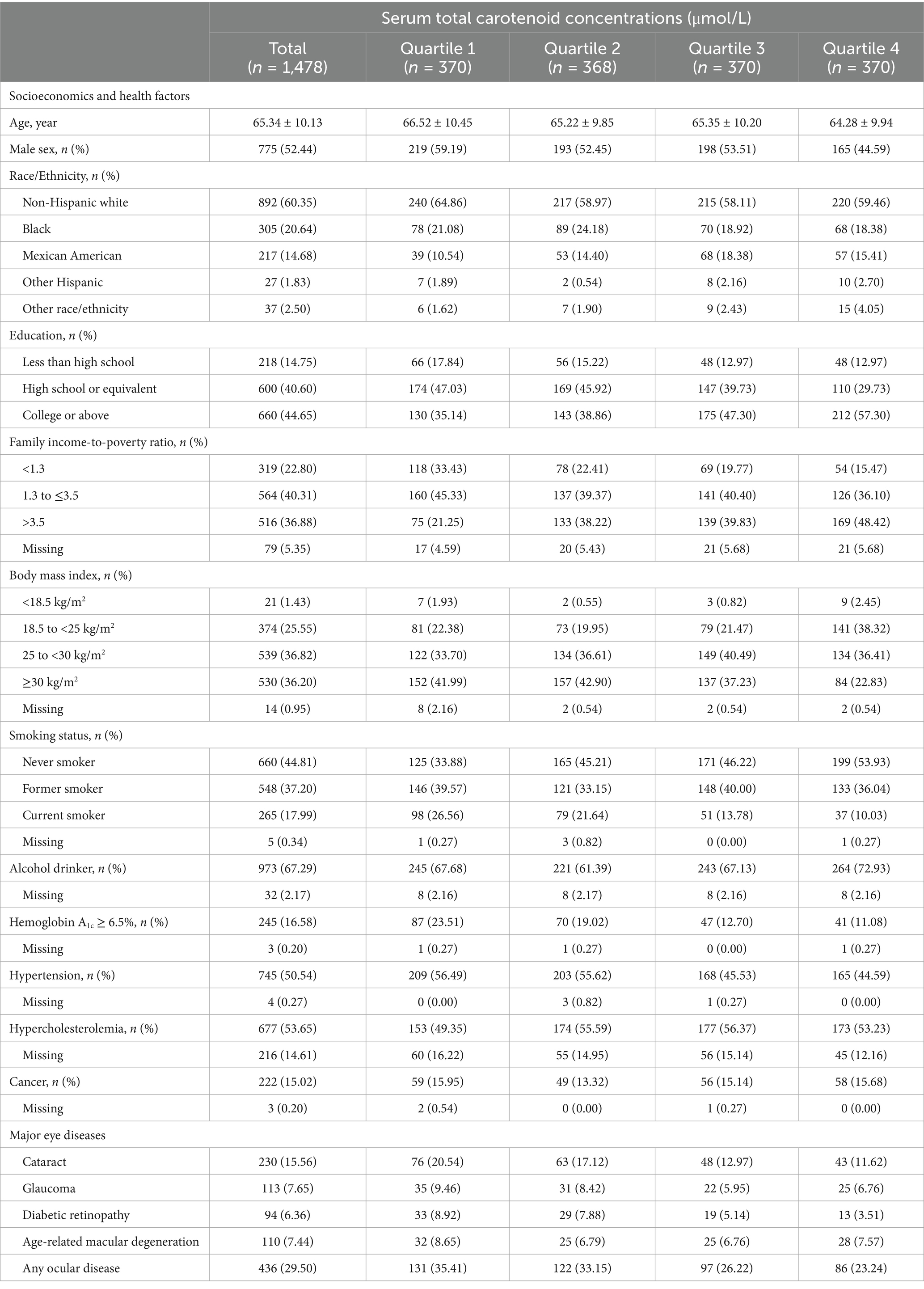

The demographic characteristics of participants are summarized in Table 1. Among 1,478 participants, there were 775 (52.44%) males and 703 (47.56%) females, with an average age of 65.34 ± 10.13 years. There were differences in age, sex, race, education, FIR, BMI, smoking status, and proportion of alcohol drinkers, diabetes, and hypertension between quartiles of serum total carotenoid concentrations (all p < 0.05). Participants with higher serum total carotenoid concentrations were younger, more likely to be female and alcohol drinkers, less likely to be non-Hispanic whites, obese, and current smokers, and tended to have greater education and FIR level, a lower proportion of HbA1 ≥ 6.5% and hypertension. Comparison of serum carotenoid concentrations among participants, stratified by sex, is shown in Supplementary Table 1. The results showed that female participants have lower carotenoid levels compared to male participants.

3.2 Association between serum carotenoid concentrations and risk of major age-related eye diseases

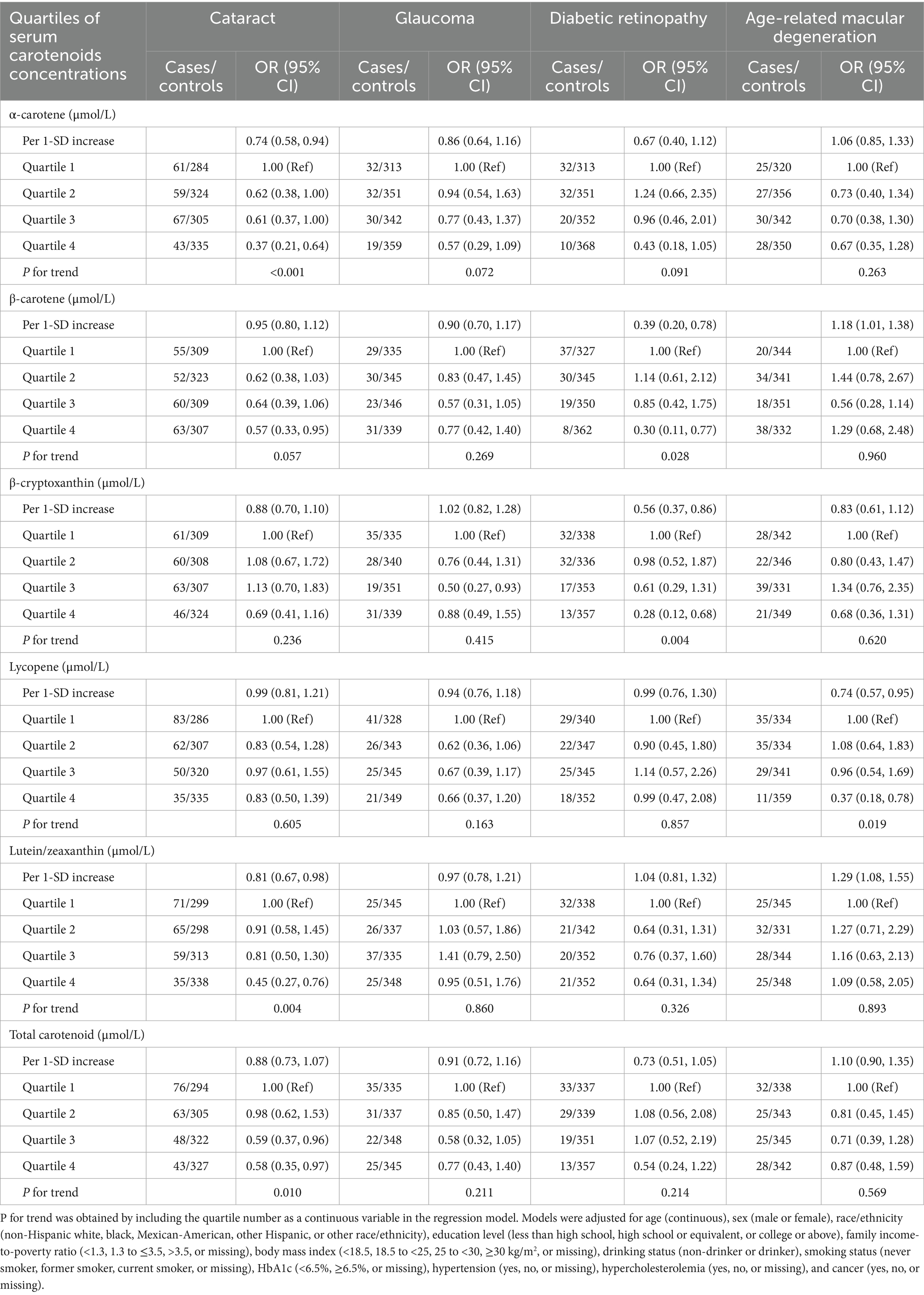

The association between serum carotenoid concentrations and risk of major eye diseases among middle-aged and older adults is presented in Table 2. After multivariable adjustment, compared to participants in the first quartile (Q1), those in highest quartile (Q4) of serum α-carotene (OR: 0.37; 95% CI: 0.21–0.64), β-carotene (OR: 0.57; 95% CI: 0.33–0.95), and lutein/zeaxanthin (OR: 0.45; 95% CI: 0.27–0.76) were negatively associated with risk of cataract; those in higher quartile (Q3) of serum β-cryptoxanthin (OR: 0.50; 95% CI: 0.27–0.93) was negatively associated with risk of glaucoma; those in highest quartile of serum β-carotene (OR: 0.30; 95% CI: 0.11–0.77) and β-cryptoxanthin (OR: 0.28; 95% CI: 0.12–0.68) were negatively associated with risk of diabetic retinopathy; and those in highest quartile of lycopene (OR: 0.37; 95% CI: 0.180.78) was negatively associated with risk of AMD. In addition, the highest quartile of serum total carotenoid concentrations was negatively associated with risk of cataract (OR: 0.58; 95% CI: 0.35–0.97) compared to the first quartile. Similar results were also observed in univariate analysis of the association between serum carotenoid concentrations and risk of major age-related eye diseases (Supplementary Table 2). Sensitivity analysis, which included additional adjustment for dietary carotenoid intake, showed that the association between serum carotenoids and the risk of age-related eye diseases remained largely unchanged (Supplementary Table 3). In addition, the sensitivity analysis to assess the possible effects of missing data yielded results was also conducted, and the results showed that these associations were robust across sensitivity analyses excluding participants with missing data on covariates (Supplementary Table 4).

Table 2. Association between serum carotenoid concentrations and risk of major age-related eye diseases among middle-aged and older adults.

3.3 Association between serum carotenoid concentrations and risk of any ocular disease among middle-aged and older adults

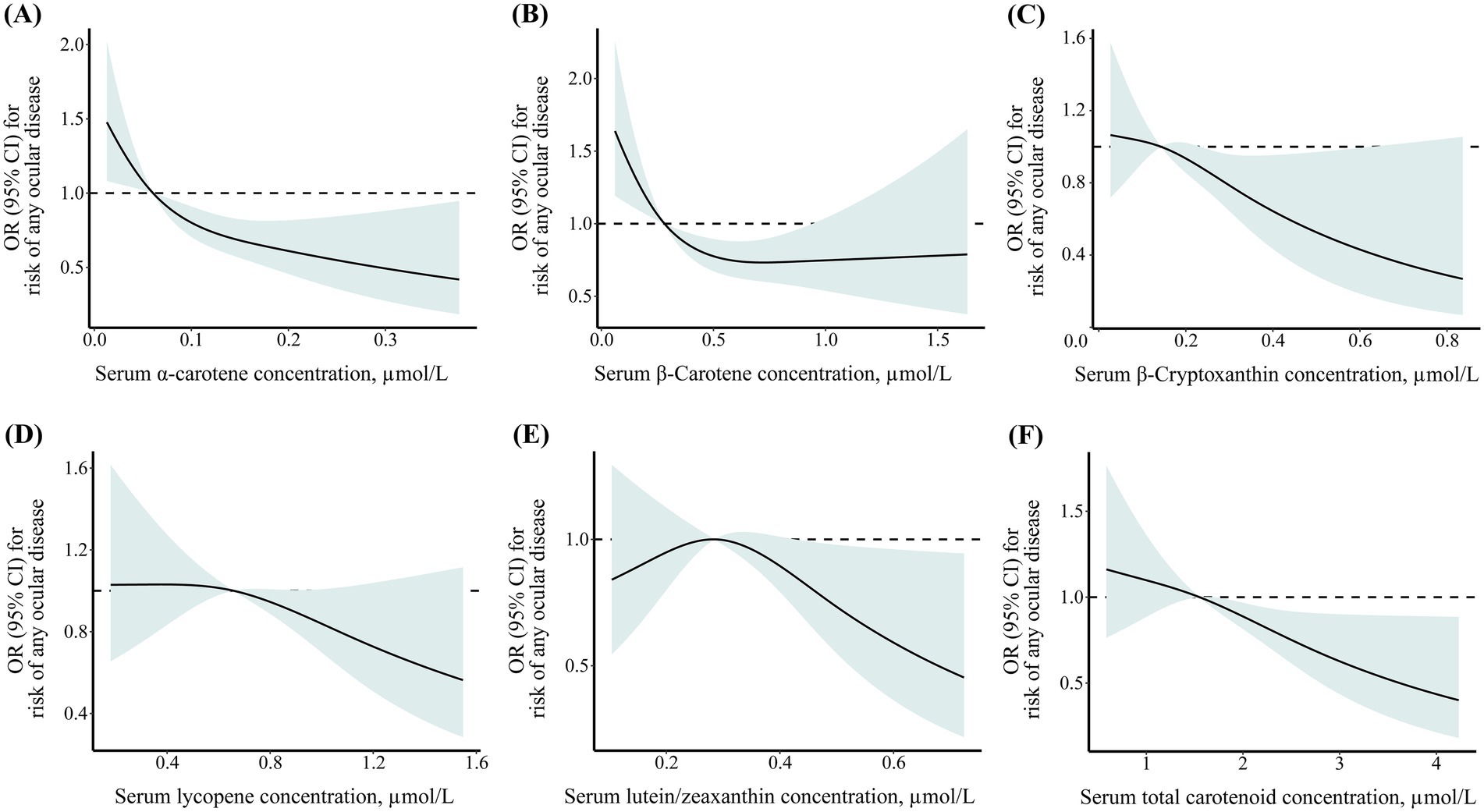

As shown in Figure 1, the restricted cubic spline results showed that the negative dose–response association between serum α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, lutein/zeaxanthin, and total carotenoid concentrations and risk of any ocular disease among middle-aged and older adults. In addition, multivariable adjustment model results showed that compared to participants in the first quartile, those in highest quartile of serum α-carotene (OR: 0.47; 95% CI: 0.31–0.71), β-carotene (OR: 0.54; 95% CI: 0.36–0.81), β-cryptoxanthin (OR: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.45–0.99), lycopene (OR: 0.62; 95% CI: 0.42–0.91), and total carotenoid (OR: 0.63; 95% CI: 0.42–0.92) concentrations were negatively associated with risk of any ocular disease (Table 3). The associations between serum carotenoid concentrations and risk of any ocular disease were also robust across sensitivity analyses excluding participants with missing data on covariates (Supplementary Table 5).

Figure 1. Dose–response association between geriatric nutritional risk index and cognitive function level among older adults with cardiometabolic disease. (A) α-carotene; (B) β-carotene; (C) β-cryptoxanthin; (D) lycopene; (E) lutein/zeaxanthin; (F) total carotenoid.

Table 3. Association between serum carotenoid concentrations and risk of ocular disease among middle-aged and older adults.

3.4 Subgroup analysis

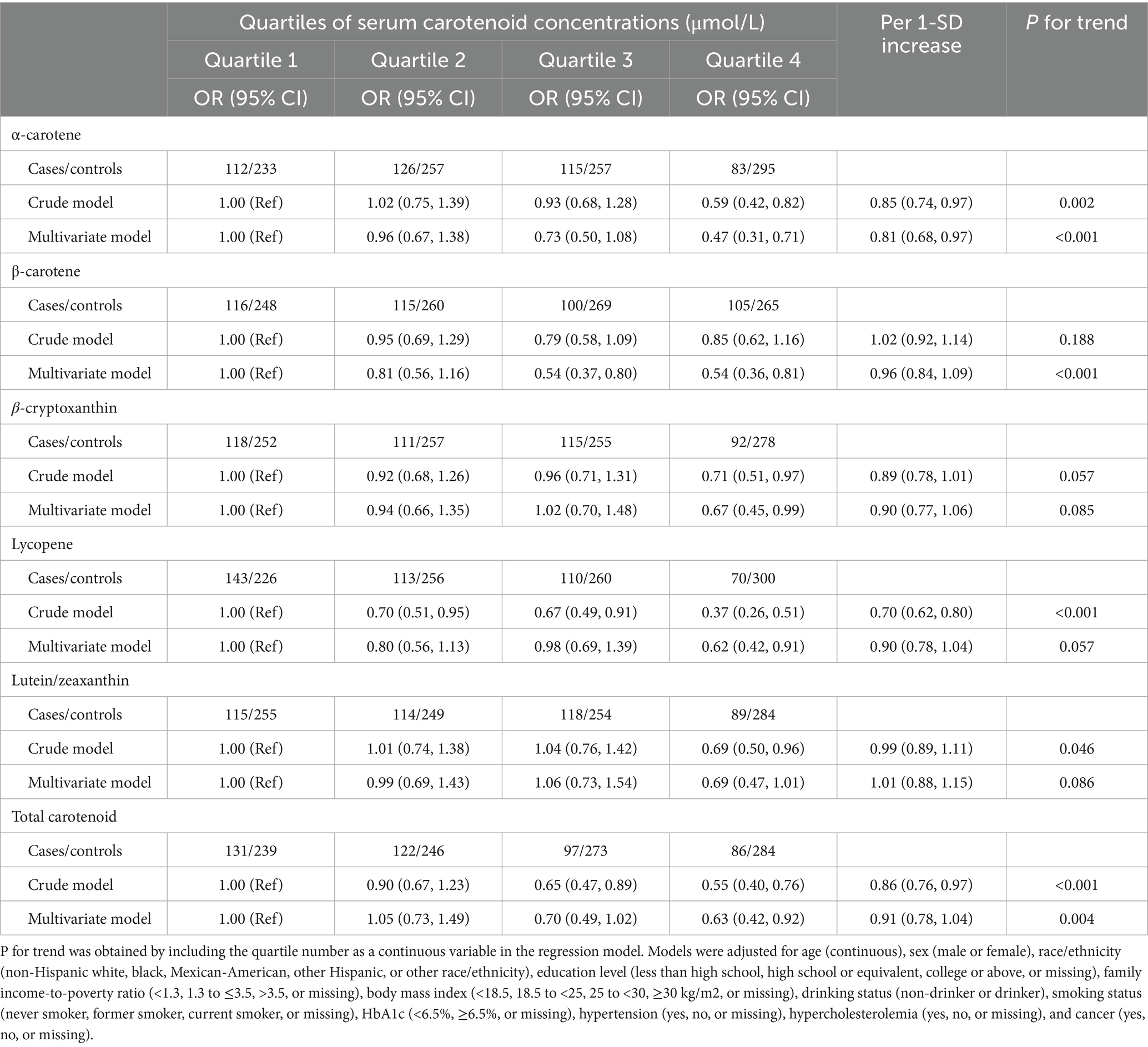

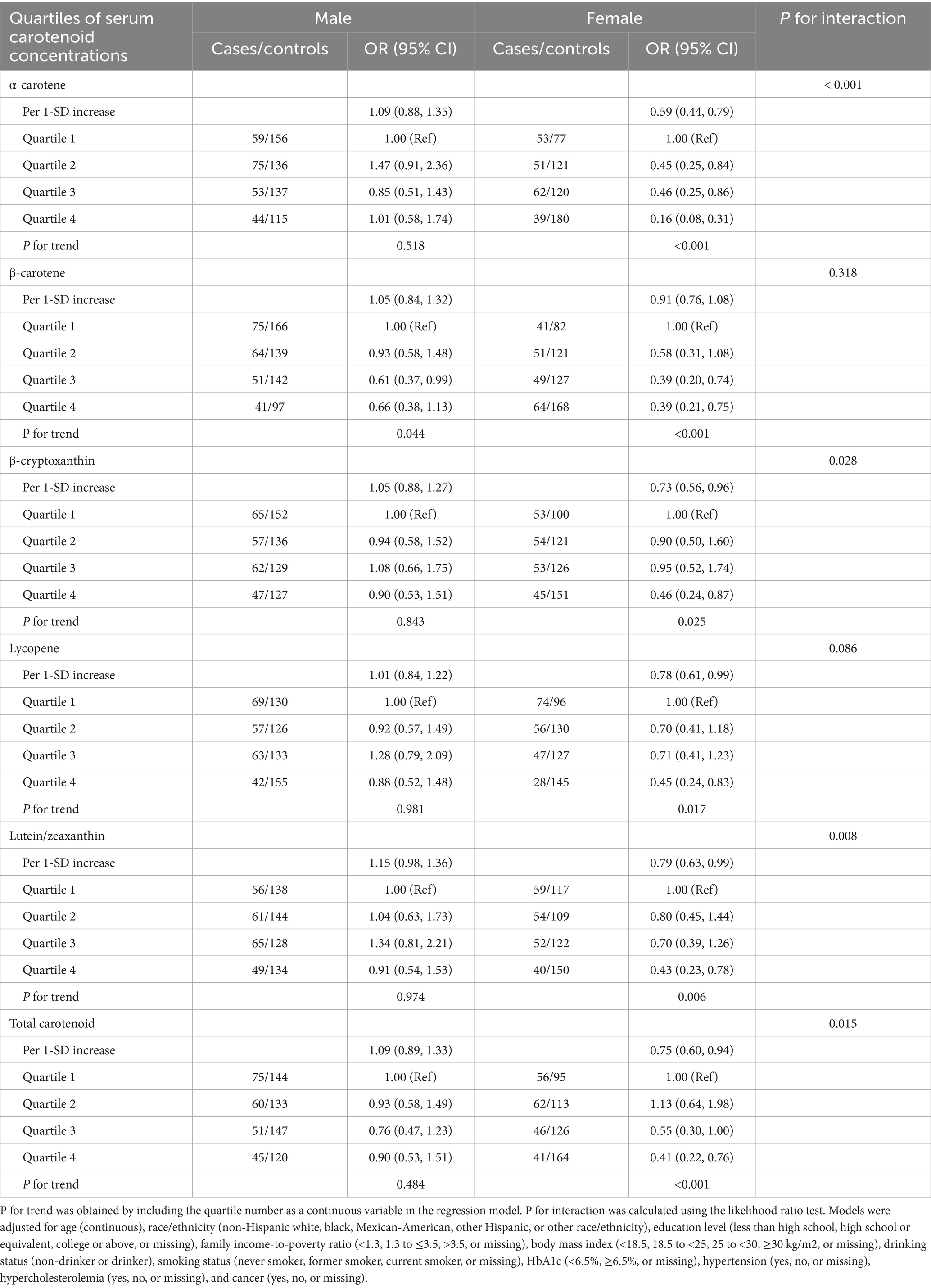

Subgroup analysis stratified by sex was conducted to examine the association between serum carotenoid concentrations and risk of any ocular disease (Table 4). Compared to participants in the first quartile, those in highest quartile of serum α-carotene (OR: 0.16; 95% CI: 0.08–0.31), β-carotene (OR: 0.39; 95% CI: 0.21–0.75), β-cryptoxanthin (OR: 0.46; 95% CI: 0.24–0.87), lycopene (OR: 0.45; 95% CI: 0.24–0.83), lutein/zeaxanthin (OR: 0.43; 95% CI: 0.23–0.78), and total carotenoid (OR: 0.41; 95% CI: 0.22–0.76) concentrations were negatively associated with risk of any ocular disease among female participants. By contrast, no association was observed between serum total carotenoid concentrations and risk of any ocular disease among male participants (all P for trend>0.05).

Table 4. Association between serum carotenoid concentrations and risk of ocular disease among middle-aged and older adults by sex.

Furthermore, compared to those in the first quartile, the highest quartile of serum α-carotene (OR: 0.15; 95% CI: 0.06–0.36), β-carotene (OR: 0.42; 95% CI: 0.18–0.97), lutein/zeaxanthin (OR: 0.26; 95% CI: 0.11–0.61), and total carotenoid (OR: 0.35; 95% CI: 0.15–0.80) concentrations were negatively associated with risk of cataract among female participants (Supplementary Table 6); the highest quartile of serum α-carotene (OR: 0.24; 95% CI: 0.09–0.67) was negatively associated with risk of glaucoma among female participants (Supplementary Table 7); those in highest quartile of serum α-carotene (OR: 0.22; 95% CI: 0.06–0.82) and β-carotene (OR: 0.24; 95% CI: 0.06–0.95) were negatively associated with risk of diabetic retinopathy among female participants; those in highest quartile of serum β-cryptoxanthin (OR: 0.25; 95% CI: 0.07–0.88) was also negatively associated with risk of diabetic retinopathy among male participants (Supplementary Table 8); and those in the highest quartile of serum lycopene (OR: 0.14; 95% CI: 0.03, 0.67) was negatively associated with risk of AMD among female participants (Supplementary Table 9). In addition, we performed stratified analyses by smoking status, and did not find a statistically significant interaction between smoking status and β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lutein/zeaxanthin, lycopene, and total carotenoid levels on the risk of age-related ocular diseases in our analysis (Supplementary Table 10).

4 Discussion

The present study investigated the associations between the serum carotenoid concentration and the risk of major age-related eye diseases in a nationally representative sample of the middle-aged and older adult population in the United States. The findings indicated that higher serum concentrations of α-carotene, β-carotene, and lutein/zeaxanthin were negatively associated with the risk of cataracts; a higher serum concentration of β-cryptoxanthin was negatively associated with the risk of glaucoma; higher serum concentrations of β-carotene and β-cryptoxanthin were negatively associated with the risk of diabetic retinopathy; and a higher serum concentration of lycopene was negatively associated with the risk of AMD. In addition, we discovered that serum concentrations of α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, and total carotenoids were inversely associated with the risk of any ocular disease, particularly among the female participants of the present study.

Although the causes of age-related eye diseases are complex and multifactorial, oxidative stress is widely recognized as a common factor that contributes to the development of age-related eye diseases in middle-aged and older adults (31, 32). The eyes are particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress due to factors such as direct exposure to ultraviolet light, a high content of mitochondria, and high metabolic activity (2, 33). Studies have demonstrated that reactive oxygen species (ROS) can cause cataracts by damaging cell membrane fibers and crystalline proteins (34). The complex non-enzymatic and enzymatic antioxidant system in the lens can scavenge ROS for preserving lens proteins, whereas the weakening of this antioxidant defense system can cause damage to lens molecules and disrupt their repair mechanisms (35). Furthermore, in several studies examining the superoxide dismutase-knockdown mouse model, mice with lower levels of antioxidants were reported to exhibit higher ROS levels; these mice also displayed various AMD characteristics, including drusen, thickened Bruch’s membrane, and choroidal neovascularization (36–38). Oxidative stress has been speculated to be involved in diabetic retinopathy. For example, studies have demonstrated that oxidative stress can alter the blood–retinal barrier and increase vascular permeability, which are the most prominent characteristics of diabetic retinopathy (39). Therefore, antioxidants may alleviate diabetic retinopathy. A study reported that the long-term administration of antioxidants inhibited the development of early-stage diabetic retinopathy in diabetic rats (40).

A growing body of evidence suggests that carotenoids have antioxidant effects and that higher circulating concentrations of carotenoids are associated with lower risks of various oxidative stress–related chronic diseases, such as diabetes, hypertension, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (11, 26, 41, 42). Because carotenoids may be involved in cellular signaling pathways related to inflammation and oxidative stress, they may inhibit oxidative stress and inflammation (43). However, to date, no systematic evaluation has examined the associations between the serum concentrations of various carotenoids and the development of age-related eye diseases, and most studies have mainly focused on single eye diseases. A meta-analysis of observational studies indicated that the serum concentration of β-carotene was associated with a reduced risk of cataracts (44). Similarly, inverse associations were observed between the serum concentrations of α-carotene, lutein, and zeaxanthin and the risk of cataracts (45), corresponding to our findings. To the best of our knowledge, no study has evaluated the associations between serum concentrations of carotenoids and the risk of glaucoma. Only one study reported that the dietary intake of α-carotene, β-carotene, or lutein/zeaxanthin was associated with a decreased risk of glaucoma among older African-American women. The present study also identified negative associations between the serum concentration of α-carotene and the risk of glaucoma among female participants (46). Regarding the associations between the serum concentrations of carotenoids and the risk of diabetic retinopathy, a study reported that the plasma levels of carotenoids, including α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, and lutein/zeaxanthin, were lower in individuals with diabetic retinopathy than in those without diabetic retinopathy (47). Similar to our findings, the results of a cross-sectional study conducted in a Chinese population indicated that a higher serum concentration of β-carotene is associated with a lower risk of diabetic retinopathy, suggesting that β-carotene plays a protective role against diabetic retinopathy (23). Furthermore, in a matched case–control study of 164 patients with AMD, higher concentrations of carotenoids, including β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, and lutein/zeaxanthin, were revealed to be inversely associated with the risk of AMD (48). Our study also revealed an inverse association between the serum concentration of lycopene and the risk of AMD.

The results of the present study suggested that serum concentrations of α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene, lutein/zeaxanthin, and total carotenoids were associated with a decreased risk of any ocular disease among the female participants. By contrast, no association was identified between the serum concentrations of carotenoids and the risk of any ocular disease among the male participants. While this finding is intriguing, the underlying mechanisms remain uncertain and should be interpreted with caution. A possible explanation for this phenomenon is that relative to men, women are typically more sensitive to oxidative stress and tend to exhibit higher levels of oxidative stress (49–51). In particular, for postmenopausal women, the lack of estrogen often leads to increased oxidative stress (52). In addition, women may have a higher risk of age-related eye diseases than men because of various socioeconomic factors and the effects of estrogen withdrawal during menopause (4). In addition, the stronger inverse associations observed in women may reflect estrogen’s modulation of carotenoid metabolism and absorption. For instance, scavenger receptor class B member 1 (SR-B1) is a multiligand receptor that facilitates the uptake of cholesteryl esters from high-density lipoproteins (HDLs) and the transport of carotenoids. Its expression is transcriptionally upregulated by estrogen through the direct binding of estrogen receptors to estrogen response elements (EREs) in its promoter (53). This is supported by our supplementary analysis showing lower carotenoid levels in female participants compared to male participants (54). However, it is important to note that these explanations remain hypothetical. Residual confounding by unmeasured socioeconomic or lifestyle factors. Therefore, our results should be seen as generating a hypothesis that warrants further investigation in studies designed specifically to explore causal mechanisms behind sex differences in carotenoid metabolism and ocular protection.

The present study has several strengths. First, we comprehensively assessed the associations between the serum concentrations of various carotenoids and the risk of various age-related eye diseases, including cataract, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and AMD. Notably, our study is the first to explore the dose–response relationship between the serum concentrations of various carotenoids and the risk of any ocular disease. Second, because we used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, which is a nationally representative database, our findings can be generalized to the community-dwelling population in the United States. Third, our analyses were adjusted for an extensive set of confounders, including socioeconomic and health factors. Finally, serum carotenoid levels provide a more robust and biologically relevant measure than dietary intake estimates for studying age-related eye diseases. Unlike questionnaire-based dietary data, serum concentrations objectively reflect bioavailable carotenoid exposure, integrating absorption efficiency, metabolic variation, and contributions from both diet and supplements. Crucially, they exhibit stronger physiological plausibility for antioxidant protection in ocular tissues and, in our analyses, remained independently associated with disease risk even after adjustment for dietary intake, highlighting their value as a superior biomarker in nutritional ophthalmology research.

Nonetheless, the present study still has several limitations. First, because of the cross-sectional design of our study, we could not explore the causal relationship between the serum concentrations of the studied carotenoids and the development of age-related eye diseases. Second, the cohort consisted predominantly of non-Hispanic White participants, with underrepresented groups comprising a smaller proportion, which limits the generalizability of our findings. Third, our study is limited by the classification of diabetic retinopathy within the NHANES database, which did not separately identify proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR). Consequently, our analysis was restricted to non-proliferative stages, potentially diluting the observed effect sizes and preventing an assessment of whether higher carotenoid levels are associated with a reduced risk of progressing to sight-threatening PDR. This may result in a conservative underestimation of the true protective association. Fourth, cataract and glaucoma were defined based on self-reported data obtained during a personal interview. This method does not allow differentiation between primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) and ocular hypertension (OHT). Since OHT is not associated with the optic nerve damage characteristic of POAG, this misclassification likely biases the observed associations toward null, thereby potentially underestimating the relationship between carotenoid levels and neurodegenerative glaucomatous pathology. Future prospective studies should incorporate detailed clinical assessments, such as optic nerve head imaging, visual field testing, to improve diagnostic accuracy and better distinguish between glaucoma subtypes. Fifth, due to constraints in the NHANES dataset, we did not exclude participants with non-age-related ocular conditions (e.g., uveitis and traumatic cataract) or a history of cataract surgery, which may introduce some potential for confounding. Furthermore, the findings of the present study could have been influenced by residual confounders, such as dietary supplementation (AREDS formulations, multivitamins) and medication use (statins, corticosteroids). Finally, the sample size of the present study was small because limited data were available, and the associations between the serum concentrations of several carotenoids and the development of age-related eye diseases approached statistical significance. Although the FDR correction was applied to mitigate the risk of false positives resulting from multiple comparisons, some significant findings may still be attributable to type I error. Therefore, our overall findings must be further verified through prospective studies with larger sample sizes.

5 Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that higher serum concentrations of carotenoids, particularly α-carotene, β-carotene, β-cryptoxanthin, and lycopene, were associated with a lower risk of age-related eye diseases. The present findings need to be verified in prospective studies with a larger sample size.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Research Ethics Review Board of the US Centers for Disease Control and the National Center for Health Statistics. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. YM: Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft. JC: Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Health Special Fund of the Jilin Provincial Department of Finance (Project No. 2019SCZT020) and the Capacity Building for Jilin Provincial Ophthalmic Engineering Laboratory (Project No. 2022C006).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the investigators, the staff, and the participants of NHANES for their valuable contributions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1596799/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Wong, WL, Su, X, Li, X, Cheung, CM, Klein, R, Cheng, CY, et al. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. (2014) 2:e106–16. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(13)70145-1

2. Bungau, S, Abdel-Daim, MM, Tit, DM, Ghanem, E, Sato, S, Maruyama-Inoue, M, et al. Health benefits of polyphenols and carotenoids in age-related eye diseases. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. (2019) 2019:1–22. doi: 10.1155/2019/9783429

3. Rauf, A, Imran, M, Suleria, HAR, Ahmad, B, Peters, DG, and Mubarak, MS. A comprehensive review of the health perspectives of resveratrol. Food Funct. (2017) 8:4284–305. doi: 10.1039/c7fo01300k

4. Zetterberg, M. Age-related eye disease and gender. Maturitas. (2016) 83:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.10.005

5. Voleti, VB, and Hubschman, JP. Age-related eye disease. Maturitas. (2013) 75:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.01.018

6. Ehrlich, JR, Ramke, J, Macleod, D, Burn, H, Lee, CN, Zhang, JH, et al. Association between vision impairment and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. (2021) 9:e418–30. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(20)30549-0

7. Ghanbarnia, MJ, Hosseini, SR, Ghasemi, M, Roustaei, GA, Mekaniki, E, Ghadimi, R, et al. Association of age-related eye diseases with cognitive frailty in older adults: a population-based study. Aging Clin Exp Res. (2023) 35:1731–40. doi: 10.1007/s40520-023-02458-z

8. Knudtson, MD, Klein, BE, and Klein, R. Age-related eye disease, visual impairment, and survival: the beaver dam eye study. Arch Ophthalmol. (2006) 124:243–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.2.243

9. Karakuş, MM, and Çalışkan, UK. Phytotherapeutic and natural compound applications for age-related, inflammatory and serious eye ailments. Curr Mol Pharmacol. (2021) 14:689–713. doi: 10.2174/1874467213666201221163210

10. Rodriguez-Concepcion, M, Avalos, J, Bonet, ML, Boronat, A, Gomez-Gomez, L, Hornero-Mendez, D, et al. A global perspective on carotenoids: metabolism, biotechnology, and benefits for nutrition and health. Prog Lipid Res. (2018) 70:62–93. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2018.04.004

11. Xiao, ML, Chen, GD, Zeng, FF, Qiu, R, Shi, WQ, Lin, JS, et al. Higher serum carotenoids associated with improvement of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults: a prospective study. Eur J Nutr. (2019) 58:721–30. doi: 10.1007/s00394-018-1678-1

12. Qiu, Z, Chen, X, Geng, T, Wan, Z, Lu, Q, Li, L, et al. Associations of serum carotenoids with risk of cardiovascular mortality among individuals with type 2 diabetes: results from NHANES. Diabetes Care. (2022) 45:1453–61. doi: 10.2337/dc21-2371

13. Johra, FT, Bepari, AK, Bristy, AT, and Reza, HM. A mechanistic review of β-carotene, lutein, and zeaxanthin in eye health and disease. Antioxidants. (2020) 9:1046. doi: 10.3390/antiox9111046

14. Widjaja-Adhi, MAK, Ramkumar, S, and von Lintig, J. Protective role of carotenoids in the visual cycle. FASEB J. (2018) 32:6305–15. doi: 10.1096/fj.201800467R

15. Lem, DW, Gierhart, DL, and Davey, PG. A systematic review of carotenoids in the management of diabetic retinopathy. Nutrients. (2021) 13:2441. doi: 10.3390/nu13072441

16. Brown, L, Rimm, EB, Seddon, JM, Giovannucci, EL, Chasan-Taber, L, Spiegelman, D, et al. A prospective study of carotenoid intake and risk of cataract extraction in US men. Am J Clin Nutr. (1999) 70:517–24. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.4.517

17. Jiang, H, Yin, Y, Wu, CR, Liu, Y, Guo, F, Li, M, et al. Dietary vitamin and carotenoid intake and risk of age-related cataract. Am J Clin Nutr. (2019) 109:43–54. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy270

18. Loughman, J, Loskutova, E, Butler, JS, Siah, WF, and O'Brien, C. Macular pigment response to lutein, zeaxanthin, and meso-zeaxanthin supplementation in open-angle glaucoma: a randomized controlled trial. Ophthalmol Sci. (2021) 1:100039. doi: 10.1016/j.xops.2021.100039

19. Chew, EY, Clemons, TE, Agrón, E, Domalpally, A, Keenan, TDL, Vitale, S, et al. Long-term outcomes of adding lutein/zeaxanthin and ω-3 fatty acids to the AREDS supplements on age-related macular degeneration progression: AREDS2 report 28. JAMA Ophthalmol. (2022) 140:692–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2022.1640

20. Satia, JA, Littman, A, Slatore, CG, Galanko, JA, and White, E. Long-term use of beta-carotene, retinol, lycopene, and lutein supplements and lung cancer risk: results from the VITamins and lifestyle (VITAL) study. Am J Epidemiol. (2009) 169:815–28. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn409

21. Zhang, J, Xiao, L, Zhao, X, Wang, P, and Yang, C. Exploring the association between composite dietary antioxidant index and ocular diseases: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. (2025) 25:625. doi: 10.1186/s12889-025-21867-5

22. Xiong, R, Yuan, Y, Zhu, Z, Wu, Y, Ha, J, Han, X, et al. Micronutrients and diabetic retinopathy: evidence from the National Health and nutrition examination survey and a meta-analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. (2022) 238:141–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2022.01.005

23. She, C, Shang, F, Zhou, K, and Liu, N. Serum carotenoids and risks of diabetes and diabetic retinopathy in a Chinese population sample. Curr Mol Med. (2017) 17:287–97. doi: 10.2174/1566524017666171106112131

24. Dherani, M, Murthy, GV, Gupta, SK, Young, IS, Maraini, G, Camparini, M, et al. Blood levels of vitamin C, carotenoids and retinol are inversely associated with cataract in a north Indian population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2008) 49:3328–35. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1202

25. Zhou, H, Zhao, X, Johnson, EJ, Lim, A, Sun, E, Yu, J, et al. Serum carotenoids and risk of age-related macular degeneration in a Chinese population sample. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2011) 52:4338–44. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6519

26. Zhu, X, Shi, M, Pang, H, Cheang, I, Zhu, Q, Guo, Q, et al. Inverse association of serum carotenoid levels with prevalence of hypertension in the general adult population. Front Nutr. (2022) 9:971879. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.971879

27. Li, HY, Yang, Q, Dong, L, Zhang, RH, Zhou, WD, Wu, HT, et al. Visual impairment and major eye diseases in stroke: a national cross-sectional study. Eye (Lond). (2023) 37:1850–5. doi: 10.1038/s41433-022-02238-5

28. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. (2011) 34 Suppl 1:S62–9. doi: 10.2337/dc11-S062

29. Jaddoe, VW, de Jonge, LL, Hofman, A, Franco, OH, Steegers, EA, and Gaillard, R. First trimester fetal growth restriction and cardiovascular risk factors in school age children: population based cohort study. BMJ (Clinical research ed). (2014) 348:g14. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g14

30. Kernan, WN, Viscoli, CM, Brass, LM, Broderick, JP, Brott, T, Feldmann, E, et al. Phenylpropanolamine and the risk of hemorrhagic stroke. N Engl J Med. (2000) 343:1826–32. doi: 10.1056/nejm200012213432501

31. Choo, PP, Woi, PJ, Bastion, MC, Omar, R, Mustapha, M, and Md Din, N. Review of evidence for the usage of antioxidants for eye aging. Biomed Res Int. (2022) 2022:5810373. doi: 10.1155/2022/5810373

32. Blasiak, J, Sobczuk, P, Pawlowska, E, and Kaarniranta, K. Interplay between aging and other factors of the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Ageing Res Rev. (2022) 81:101735. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2022.101735

33. Shoham, A, Hadziahmetovic, M, Dunaief, JL, Mydlarski, MB, and Schipper, HM. Oxidative stress in diseases of the human cornea. Free Radic Biol Med. (2008) 45:1047–55. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.07.021

34. Spector, A. Oxidative stress-induced cataract: mechanism of action. FASEB J. (1995) 9:1173–82. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.12.7672510

35. Heruye, SH, Maffofou Nkenyi, LN, Singh, NU, Yalzadeh, D, Ngele, KK, Njie-Mbye, YF, et al. Current trends in the pharmacotherapy of cataracts. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland). (2020) 13:15. doi: 10.3390/ph13010015

36. Imamura, Y, Noda, S, Hashizume, K, Shinoda, K, Yamaguchi, M, Uchiyama, S, et al. Drusen, choroidal neovascularization, and retinal pigment epithelium dysfunction in SOD1-deficient mice: a model of age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2006) 103:11282–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602131103

37. Justilien, V, Pang, JJ, Renganathan, K, Zhan, X, Crabb, JW, Kim, SR, et al. SOD2 knockdown mouse model of early AMD. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2007) 48:4407–20. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0432

38. Goodman, D, and Ness, S. The role of oxidative stress in the aging eye. Life (Basel, Switzerland). (2023) 13:837. doi: 10.3390/life13030837

39. Frey, T, and Antonetti, DA. Alterations to the blood-retinal barrier in diabetes: cytokines and reactive oxygen species. Antioxid Redox Signal. (2011) 15:1271–84. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.3906

40. Kowluru, RA, Tang, J, and Kern, TS. Abnormalities of retinal metabolism in diabetes and experimental galactosemia. VII. Effect of long-term administration of antioxidants on the development of retinopathy. Diabetes. (2001) 50:1938–42. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.8.1938

41. Zhu, R, Chen, B, Bai, Y, Miao, T, Rui, L, Zhang, H, et al. Lycopene in protection against obesity and diabetes: a mechanistic review. Pharmacol Res. (2020) 159:104966. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104966

42. Wang, M, Tang, R, Zhou, R, Qian, Y, and Di, D. The protective effect of serum carotenoids on cardiovascular disease: a cross-sectional study from the general US adult population. Front Nutr. (2023) 10:1154239. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1154239

43. Yao, Y, Goh, HM, and Kim, JE. The roles of carotenoid consumption and bioavailability in cardiovascular health. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland). (2021) 10:1978. doi: 10.3390/antiox10121978

44. Wang, A, Han, J, Jiang, Y, and Zhang, D. Association of vitamin a and β-carotene with risk for age-related cataract: a meta-analysis. Nutrition. (2014) 30:1113–21. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2014.02.025

45. Cui, YH, Jing, CX, and Pan, HW. Association of blood antioxidants and vitamins with risk of age-related cataract: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J Clin Nutr. (2013) 98:778–86. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.053835

46. Giaconi, JA, Yu, F, Stone, KL, Pedula, KL, Ensrud, KE, Cauley, JA, et al. The association of consumption of fruits/vegetables with decreased risk of glaucoma among older African-American women in the study of osteoporotic fractures. Am J Ophthalmol. (2012) 154:635–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.03.048

47. Shalini, T, Jose, SS, Prasanthi, PS, Balakrishna, N, Viswanath, K, and Reddy, GB. Carotenoid status in type 2 diabetes patients with and without retinopathy. Food Funct. (2021) 12:4402–10. doi: 10.1039/d0fo03321a

48. Jiang, H, Fan, Y, Li, J, Wang, J, Kong, L, Wang, L, et al. The associations of plasma carotenoids and vitamins with risk of age-related macular degeneration: results from a matched case-control study in China and Meta-analysis. Front Nutr. (2022) 9:745390. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.745390

49. Vassalle, C, Maffei, S, Boni, C, and Zucchelli, GC. Gender-related differences in oxidative stress levels among elderly patients with coronary artery disease. Fertil Steril. (2008) 89:608–13. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.03.052

50. Dreyer, L, Prescott, E, and Gyntelberg, F. Association between atherosclerosis and female lung cancer--a Danish cohort study. Lung Cancer. (2003) 42:247–54. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00295-2

51. Zhou, Q, Chen, X, Chen, Q, and Hao, L. Independent and combined associations of dietary antioxidant intake with bone mineral density and risk of osteoporosis among elderly population in United States. J Orthop Sci. (2023) 29:1064–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jos.2023.07.014

52. Shi, WQ, Liu, J, Cao, Y, Zhu, YY, Guan, K, and Chen, YM. Association of dietary and serum vitamin E with bone mineral density in middle-aged and elderly Chinese adults: a cross-sectional study. Br J Nutr. (2016) 115:113–20. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515004134

53. Valacchi, G, and Pecorelli, A. Role of scavenger receptor B1 (SR-B1) in improving food benefits for human health. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. (2025) 16:403–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-111523-121935

Keywords: serum carotenoids, cataract, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration, NHANES

Citation: Che S, Ma Y and Cao J (2025) Association between serum carotenoid concentrations and risk of major age-related eye diseases among middle-aged and older adults. Front. Med. 12:1596799. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1596799

Edited by:

Livio Vitiello, Azienda Sanitaria Locale Salerno, ItalyReviewed by:

Dario Rusciano, Consultant, Catania, ItalyMianli Xiao, University of South Florida, United States

Copyright © 2025 Che, Ma and Cao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jinfeng Cao, amNhb0BqbHUuZWR1LmNu

Songtian Che1

Songtian Che1 Jinfeng Cao

Jinfeng Cao