Abstract

Background:

Worldwide, millions of people suffer from snakebites every year. In Ecuador, as of epidemiological week 30 of 2024, approximately 271 cases have been reported.

Clinical case:

A 54-year-old male patient suffered a snakebite from the Viperidae family 24 h ago, on his right upper limb. Classified as moderate envenomation, he was given antivenom and admitted to the hospital. During his stay, he began to show clinical and paraclinical alterations, including sinus bradycardia on the electrocardiogram and acute renal injury, requiring dialysis therapy sessions. In daily ECG controls on day 13, the heart rate normalized. However, after day 22, he was discharged but remained under triweekly dialysis therapy.

Conclusion:

Complications from snakebites are rare, both cardiovascular and renal, but can be potentially fatal without early detection and timely treatment.

1 Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), it is estimated that between 4.5 and 5.4 million people are bitten by snakes each year, of which between 1.8 and 2.7 million develop clinical symptoms, and between 81,000 and 138,000 die from complications (1). Several acute systemic syndromes have been described, including coagulopathy with hemorrhagic effects, neurotoxicity, myotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, and cardiotoxicity (2). The venom of the snake Lachesis acrochorda has been described to induce blood coagulation by promoting platelet aggregation. In contrast, envenomation by Bothrops jararaca causes hemostatic disturbances characterized by ecchymosis, petechiae, purpura, epistaxis, and gingival bleeding (3, 4).

In Ecuador, according to official data obtained from the National Institute of Statistics and Census (INEC), a mortality rate of 0.07 (range: 0.03–0.10) per 100,000 inhabitants was recorded during the period from 2014 to 2019. In addition, according to SIVE-ALERTA-MSP, during the period from 2016 to 2020, 7,569 cases were recorded, with an annual average of 1,514 cases (5). By 2023, 1,407 cases of snakebites had been recorded, and by epidemiological week 30 of 2024, 271 cases had been reported (6). The region with the highest incidence rate is the Amazon, with 55–78 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. A study carried out in the northern Ecuadorian Amazon, during the period from 2017 to 2021, identified 147 cases (29.4 per year), of which 20 (13.6%) were mild, 90 (61.2%) were moderate, and 37 (25.2%) were severe (5).

The snakes of primary toxicological interest identified in Ecuadorian territory include 17 species from the Viperidae family and 18 species from the Elapidae family. In western Ecuador, the Viperidae family includes the species Bothriechis schlegelii (parrot parrot), Bothrops asper (equis), and Lachesis acrochorda (verrugosa); and in the Elapidae family, Micrurus mipartitus decussatus (coral) is present (7). In the Ecuadorian Amazon, the Viperidae family includes Bothriopsis bilineata smaragdina (lorita machacui, orito machacui, lora), Bothriopsis taeniata (shishin), Bothrocophias hyoprora (padlock head), Bothrocophias microphthalmus (rotten leaf, macanchilla), Bothrops atrox (equis, pitalala), and Lachesis muta (verrugosa, yamunga); and in the Elapidae family, Micrurus helleri (coral) is present (7).

Cardiac complications are rare but can be fatal if not detected in time. Among the described cardiac complications are bradycardia or tachycardia, cardiac arrhythmias, hypertension, atrioventricular block, QT interval alterations, ST segment elevation, T wave inversion, acute myocardial infarction, hypotension, bundle branch block, myocarditis, cardiac arrest, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, pulmonary hypertension, cardiogenic shock, and heart failure (8–11). Kim et al., in their review, described the presence of cardiovascular events in 13.8% of patients. They reported myocardial injury in 13.8% of patients, elevated hs-TnI levels in 10.8%, ischemic changes detected by ECG in 3.1%, and shock in 3.1% of patients (12). Isbister et al., for their part, reported the presence of cardiovascular collapse in 157 individuals who had been bitten by snakes (13). The snake families involved in cardiac complications include Viperidae (e.g., envenomation by Daboia russelii has been described to cause atrial fibrillation), Elapidae (Bungarus cf. sindanus has been reported to induce ventricular tachycardia and impaired left ventricular systolic function, while Bungarus caeruleus can lead to the development of cardiogenic pulmonary edema), Colubridae (e.g., bites from Ahaetulla nasuta have been associated with biphasic T wave inversions), and Lamprophiidae (Atractaspis spp. envenomation may cause precordial pain, bradycardia, cardiac arrhythmia, and hypertension) (14–18). The pathophysiology of cardiovascular implications in snakebites is poorly understood, although several mechanisms have been hypothesized (Figure 1): (1) direct damage to the cardiac cell membrane, (2) toxin-mediated arrhythmias, (3) coronary syndromes secondary to hypercoagulable states, (4) coronary spasm secondary to toxins, (5) hyperkalemia following renal failure, and (6) inflammatory processes due to hypersensitivity to venom (9).

Figure 1

Mechanism of action of snakes venom to cause cardiac and renal complications.

On the other hand, within renal complications, acute kidney injury (AKI) is a known potentially fatal systemic effect of snake envenomation, especially from the Viperidae and Elapidae families (2). The incidence of AKI ranges from 8 to 60%, with between 15 and 92% of patients requiring some form of renal replacement therapy, and an overall mortality rate of up to 45% (2). Additionally, it has been observed that between 8 and 50% of patients with AKI develop chronic kidney disease. Several pathophysiological mechanisms have been proposed to explain snakebite-induced renal injury, including (Figure 1): (1) thrombotic microangiopathy due to the accumulation of fibrin in the glomerular capillaries, (2) cytotoxic action of the venom on renal tubules mediated by various cytokines, adhesion molecules, complement activation, and release of free radicals, (3) formation of microaneurysms and damage to the podocytes mediated by the proteolytic activity of the venom, and (4) pigmentary nephropathy triggered by phospholipase A2, which leads to rhabdomyolysis and myopathy (19).

The following article aims to describe the first case report of sinus bradycardia and acute kidney injury following a Viperidae snakebite in an Ecuadorian male patient who required permanent dialysis therapy at the Marco Vinicio Iza General Hospital, located in the northern Ecuadorian Amazon.

2 Case report

The case of a 54-year-old male patient is described. He lives in a rural area; is mestizo. He has a medical history of type II diabetes mellitus and hypertension (HTA) without medical treatment. He presented to the emergency department, reporting that approximately 24 h ago, he was bitten by a snake identified as a “lora” on his right shoulder while walking on an Amazon trail. The geographic location of the snakebite was Parroquia 10 de Agosto, north of Lago Agrio Canton, in the province of Sucumbíos. It is approximately 19 km from Hospital Marco Vinicio Iza. He complained of moderate pain at the affected site, with a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) score of 7/10, without any other accompanying symptoms.

On physical examination, the following vital signs were noted upon admission: BP 130/77 mmHg, HR 54 bpm (before the snakebite, the patient had normal HR. According to the Health Care Registration Platform System (PRASS), the heart rate data were as follows: 74 bpm on 26/09/2023 and 84 bpm on 27/09/2023.), RR 20 rpm, T° 36.7°C, SatO2 98%. Anthropometric measurements: Weight 82 kg, Height 1.68 meters. The regional examination revealed blisters and edema (++/+++) at the shoulder level of the right upper limb, extending to the middle third of the forearm (two segments). Distal pulses were present (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Anatomical site of snake bite. The black arrow indicates the site of the bite, and the red arrow points to the ecchymosis.

A capillary blood glucose test was performed, resulting in 112 mg/dL, and a coagulation test was positive (no coagulation after 20 min). The patient was classified as having a moderate toxic effect from snake venom, and 8 vials of antivenom were prescribed initially. During the administration of antivenom, the patient did not experience any adverse reactions. The antivenom used was a lyophilized polyvalent antivenom produced by the Clodomiro Picado Institute in Costa Rica. Each vial contains less than 1.2 g of equine immunoglobulins. Each 10 mL vial is capable of neutralizing no less than 30 mg of Bothrops asper venom, 20 mg of Crotalus simus venom, 30 mg of Lachesis stenophrys venom, and 30 mg of Bothrops atrox venom.

Admission paraclinical tests showed the following results: Leukocytes: 12.05, Neutrophils: 74.7%, Lymphocytes: 14.8%, Monocytes: 10%, Hemoglobin: 13.2 g/dL, Hematocrit: 40.9%, Platelets: 100,000, PT: 13.8, PTT: 55.2, INR: 1.7, Glucose: 109 mg/dL, Urea: 83 mg/dL, Creatinine: 5.2 mg/dL, Electrolytes: (Sodium 135.94, Potassium 3.85, Chlorine 100.08).

An electrocardiogram (ECG) was performed, which showed sinus bradycardia (Figure 3A). Twenty-four hours after admission, an abdominal ultrasound was conducted, revealing a simple renal cyst in the right kidney with no other abnormalities.

Figure 3

ECG performed on the patient. (A) Admission electrocardiogram, showing sinus bradycardia with a heart rate of 47 beats per minute. (B) ECG performed on the sixth day of hospital stay showed persistent sinus bradycardia with a heart rate of 56 beats per minute. (C) ECG performed on the thirteenth day of hospital stay, sinus rhythm was evident with a heart rate of 63 beats per minute.

On the second day of hospitalization, the patient progressively developed elevated blood pressure, an icteric tint, and abdominal distension. Complementary studies revealed thrombocytopenia, prolonged coagulation times, severe anemia, and increased nitrogen levels, requiring transfusions of blood products (fresh frozen plasma, red blood cell concentrate, and platelets). Tests for dengue and hematogenous organisms were negative (Table 1). A follow-up abdominal ultrasound on the third day revealed bilateral pleural effusion and ascites (Figure 4). At the sixth day the ECG continued to show persistent sinus bradycardia (Figure 3B).

Table 1

| Data | Value | Reference value | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admission | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 7 | Day 8 | Day 9 | Day 10 | Day 11 | Day 13 | Day 14 | Day 15 | Day 18 | Day 19 | Day 20 | ||

| Complete blood count | ||||||||||||||||||

| Leukocytes | 12.05 | 10.39 | 8.69 | 7.86 | 13.32 | 10.1 | 12.25 | 12.98 | 12.54 | 14.01 | 15.87 | 9.66 | 8.44 | 8.86 | 8.36 | 5.00–15.00 × 103/uL | ||

| Neutrophils | 74.7 | 70.3 | 74.5 | 78.9 | 90.3 | 91.1 | 85.6 | 73.3 | 76.3 | 77.9 | 83.3 | 74.4 | 77.9 | 72.6 | 71.5 | 46–62% | ||

| Lymphocytes | 14.8 | 21.4 | 14.7 | 18.8 | 5 | 5.3 | 8.9 | 19 | 16.2 | 15.6 | 12.3 | 17.7 | 12.5 | 14.8 | 16.9 | 28–44% | ||

| Eosinophils | 0.1 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 4.1 | 1–6% | ||

| Platelets | 100 | 46 | 30 | 30 | 35 | 46 | 94 | 161 | 154 | 187 | 247 | 318 | 218 | 181 | 171 | 150–450 × 103/uL | ||

| Red Blood Cells | 4.35 | 3.83 | 3.42 | 3.31 | 2.57 | 2.48 | 2.4 | 2.35 | 2.55 | 3.58 | 3.65 | 3.84 | 3.61 | 3.36 | 3.54 | 4.30–5.70 × 103/uL | ||

| Hemoglobin | 13.2 | 11.4 | 10 | 9.7 | 7.8 | 7.3 | 7.3 | 6.9 | 7.7 | 10.5 | 10.7 | 11.5 | 10.6 | 10.3 | 10.4 | 13.20–17.80 g/dL | ||

| Blood chemistry | ||||||||||||||||||

| Glucose | 97 | 82 | 148 | 141 | ||||||||||||||

| Urea | 83 | 108 | 137 | 229 | 221 | 450 | 209 | 215 | 159 | 183 | 141 | 164 | 159 | 10–48.5 mg/dL | ||||

| Creatinine | 5.2 | 7.3 | 8.6 | 11.7 | 10.7 | 13.3 | 9.1 | 8.1 | 6 | 6.2 | 4.7 | 5 | 4.6 | 0.80–1.30 mg/dL | ||||

| Uric acid | 6.1 | 3.6–8.20 mg/dL | ||||||||||||||||

| Total cholesterol | 109 | 120–200mg/dL | ||||||||||||||||

| AST | 117.23 | 88.07 | 45.82 | 32.92 | 18.57 | 15.41 | 0.00–35.00 U/L | |||||||||||

| ALT | 65.28 | 59.50 | 52.35 | 42.38 | 31.22 | 20.35 | 0.00–45.00 U/L | |||||||||||

| Total bilirubin | 8.13 | 7.47 | 7.68 | 3.84 | 2.32 | 1.51 | 1.09 | 0.30–1.10 mg/dL | ||||||||||

| Direct bilirubin | 2.63 | 2.95 | 4.11 | 1.84 | 1.08 | 0.79 | 0.51 | 0.10–0.40 mg/dL | ||||||||||

| Indirect bilirubin | 5.50 | 4.52 | 3.57 | 2 | 1.24 | 0.72 | 0.58 | 0–0.90 mg/dL | ||||||||||

| GGT | 25.69 | 37.78 | 39.87 | 11–61 U/L | ||||||||||||||

| Amylase | 105.63 | 108.02 | 28–100 U/L | |||||||||||||||

| Lipase | 30.81 | 36.14 | 0–60 U/L | |||||||||||||||

| Total proteins | 5.02 | 3.64 | 6.60–8.70 g/dL | |||||||||||||||

| Albumin | 3.33 | 3.37 | 3.97–4.94 g/Dl | |||||||||||||||

| IgM Dengue | 0.70 (negative) | Positive >1.1 Indeterminate 0.9–1.0 Negative < 0.9 |

||||||||||||||||

| Dengue NS-1 | 0.86 (negative) | Positive >1.1 Indeterminate 0.9–1.0 Negative < 0.9 |

||||||||||||||||

| Electrolytes | ||||||||||||||||||

| Na | 135.94 | 135.96 | 138.61 | 132.32 | 135.95 | 142.11 | 139.94 | 144.70 | 135–145 mmoL/mL | |||||||||

| K | 3.85 | 4 | 3.84 | 4.96 | 4.62 | 3.59 | 3.80 | 4.11 | 3.50–5.50 mmoL/mL | |||||||||

| Cl | 100.08 | 105.41 | 108.03 | 105.47 | 104.19 | 105.22 | 104.68 | 104.42 | 96–100 mmoL/mL | |||||||||

| Cardiac enzymes | ||||||||||||||||||

| CK-MB | 3.9 | 3–100 ng/mL | ||||||||||||||||

| Troponi I | 0.35 | 0.01–15 ng/mL | ||||||||||||||||

| Coagulation times | ||||||||||||||||||

| PT | 13.8 | 16.5 | 15.7 | 15.5 | 13.6 | 15.6 | 63.3 | 14.1 | 13.8 | 12.6 | 13.9 | 16.0 | 15.5 | 15 | 9.5–14 s | |||

| APTT | 55.2 | 42.7 | 44.7 | 43 | 33.8 | 35.9 | Does not clot | 30.2 | 31.1 | 34.3 | 28.2 | 34.6 | 36.7 | 38.8 | 22–40 s | |||

| INR | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 6.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0.85–1.30 | |||

| D-Dimere | 15.03 | 11.64 | <1.0 | |||||||||||||||

| Vital signs | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admis sion | Day 1 | Day 2 | Da y 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Da y 7 | Day 8 | Da y 9 | Day 10 | Day 11 | Day 13 | Day 14 | Day 15 | Day 18 | Day 19 | Day 20 | Day 21 | Day 22 | |

| Systolic pressure mmHg | 130 | 116 | 115 | 123 | 122 | 167 | 107 | 107 | 115 | 157 | 164 | 139 | 113 | 139 | 100 | 138 | 135 | 110 | 106 |

| Diastolic pressure mmHg | 77 | 74 | 70 | 74 | 79 | 97 | 64 | 57 | 68 | 81 | 89 | 100 | 70 | 81 | 64 | 74 | 67 | 63 | 59 |

| Heart rate | 80 | 52 | 56 | 58 | 56 | 58 | 54 | 56 | 62 | 64 | 48 | 54 | 58 | 56 | 72 | 72 | 70 | 72 | 70 |

Laboratory tests during hospital stay.

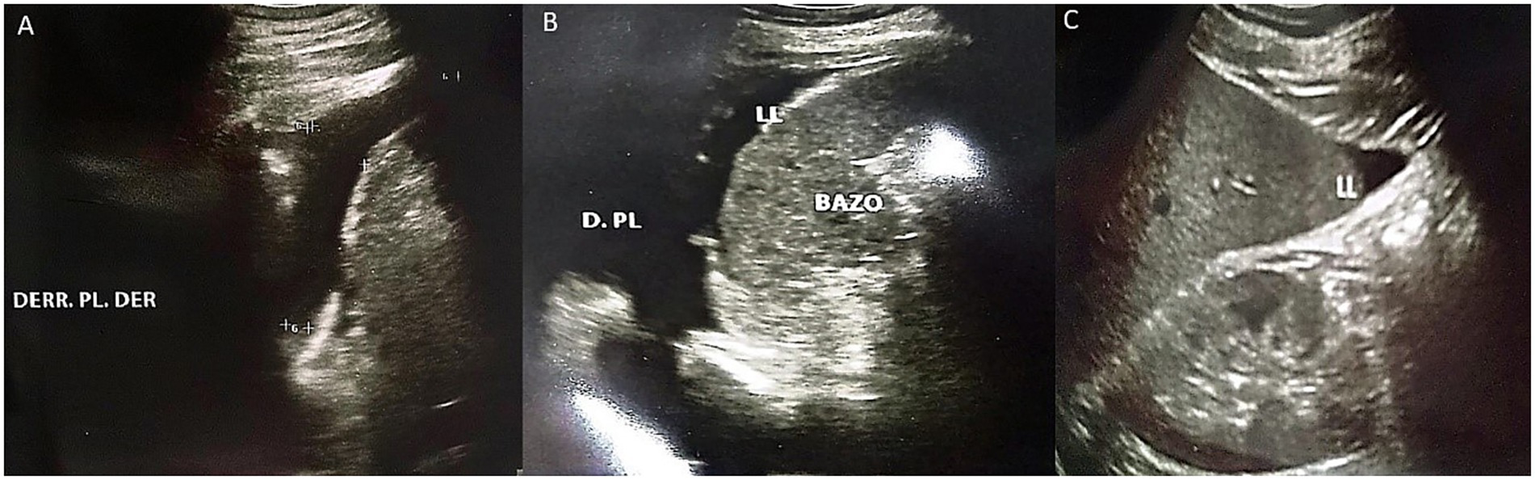

Figure 4

Abdominal ultrasound performed on the third day of hospitalization. (A) Presence of right pleural effusion is evident. (B) Presence of left pleural effusion is evident, as well as free fluid bordering the spleen. (C) Presence of free fluid bordering the liver.

Given the clinical deterioration and the paraclinical results, the patient required 8 sessions of dialysis therapy, with subsequent controls showing a decrease in nitrogen levels. He was also monitored with daily ECGs, which showed persistent sinus bradycardia until day 13, when the heart rate normalized to greater than 63 beats per minute (Figure 3C).

The patient was hospitalized for 22 days. Upon discharge, he was prescribed antihypertensive medication (nifedipine 10 mg every 12 h) and continued follow-up with nephrology, receiving dialysis every 3 weeks.

3 Discussion

Cardiovascular complications, especially sinus bradycardia, are rare, as is acute kidney injury, which in many cases requires temporary and/or definitive dialysis therapy. Early detection poses a challenge for healthcare personnel, considering that most snakebite incidents occur in rural areas with limited infrastructure and medical resources, making it difficult to collect detailed data (9, 19). In the present case, the patient developed thrombocytopenia, which is one of the main hematotoxic effects of snake venom. This condition is often secondary to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and venom-induced coagulopathy (20, 21). Anemia was also observed. Snakebite envenomation has been reported to cause consumption coagulopathy, and some patients may develop thrombotic microangiopathy, which manifests as microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (22). Moreover, the association between microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, acute kidney injury, and thrombocytopenia with venom-induced consumption coagulopathy has been recognized (23).

3.1 Sinus bradycardia after snakebite

With respect to the type of snake, cases of bradycardia have been reported in snakes from the Viperidae family (24). In this case report, the patient identified the species Bothriopsis bilineata smaragdina, known as “lora,” which belongs to the Viperidae family. It is important to highlight that in the patient, myocardial injury markers (troponin I and CK-MB) were normal, but there was cardiac alteration (sinus bradycardia). Studies in animal models have indicated that the negative inotropic effect induced by the venom is not related to cardiac toxicity and occurs through the NO/cGMP/PKG pathway. This was observed in a study analyzing the venom of Crotalus durissus cascavella in rats (25).

A study conducted by Nayak et al. in 30 patients observed cardiotoxicity in 25% of cases due to Viperidae snakes; among these, bradycardia was observed in 10% (26). ECG studies in patients with envenomation often show nonspecific changes, such as sinus arrest with junctional escape rhythm and retrograde P waves, with a heart rate of 40 beats/min, suggestive of sinus node dysfunction. However, on the third day of hospitalization for snake envenomation, a repeat ECG showed normal sinus rhythm (10). In another case report, sinus bradycardia followed by pulseless electrical activity was evident, requiring two rounds of advanced cardiac life support before return of spontaneous circulation (27). A possible direct effect of the venom on the atrioventricular node has been considered as a cause of bradycardia (24). Additionally, it has been proposed that bradycardia may occur due to parasympathetic stimulation, possibly induced by fear (11).

Different components of snake venom can affect heart rate. Bradykinin-potentiating peptides decrease the concentration of angiotensin II, leading to a reduction in blood pressure. Additionally, these peptides increase bradykinin levels, which have vasodilatory properties and can also act on receptors in the nucleus ambiguus to induce bradycardia (28, 29). On the other hand, beta-cardiotoxin, a three-finger toxin, exhibits β-blocker activity, as evidenced by its negative chronotropic effects and its ability to bind to β1- and β2-adrenergic receptors, causing bradycardia (30, 31). Cysteine-rich secretory proteins have also been reported to exert non-enzymatic inhibitory activity on L-type Ca2+ channels, leading to the development of bradycardia (32, 33). Furthermore, natriuretic peptides present in various snake species promote vascular relaxation and reduce myocardial contractility (28).

Studies using venom from various snake species have been conducted in animal models. Simões et al. analyzed the influence of Crotalus durissus cascavella venom on cardiac activity in rats. The results revealed that the venom induced hypotension and bradycardia, and they noted that the venom-induced negative inotropic effect occurs through the NO/cGMP/PKG signaling pathway, which likely leads to both hypotension and bradycardia (25). Similarly, Angel-Camilo et al. observed comparable findings in their studies analyzing the effects of Lachesis acrochorda venom on cardiovascular parameters in rats. Their results showed that the venom induced blood coagulation, platelet aggregation, hypotension, and bradycardia, in addition to increased P and T waves, prolonged QT interval, and elevated serum CK and CK-MB levels (3, 34).

In a study analyzing 80 cases of snakebite, bradycardia was observed in 10 cases (18.5%) (35). Greene et al. reported the case of a patient who was bitten by a Naja kaouthia cobra. The patient developed mild hypotension and transient bradycardia, and upon being admitted to the intensive care unit, experienced another episode of bradycardia that was corrected with atropine (36). Sachett et al. reported the case of a 65-year-old patient who was bitten by a Bothrops atrox snake, which led to the development of bradycardia (37).

Sartim et al., in their study evaluating plasma markers in 80 patients who had suffered bites from Bothrops atrox, observed elevated levels of FABP3 in at least 98.7% of the patients, troponin I in 12.5%, and CK-MB in 8.8%. Additionally, plasma levels of fibrin/fibrinogen degradation product, tissue factor, and factor VII were positively correlated with troponin I concentrations, leading to the conclusion that myocardial injury is directly associated with venom-induced coagulopathy (38).

Additionally, it is important to highlight endothelial dysfunction, particularly in the coronary vasculature. This dysfunction can be triggered by the inflammatory response induced by various components present in snake venom. Among them, phospholipase A₂ (PLA₂) stands out, as it promotes the rupture of the cell membrane, leading to the release of arachidonic acid (39). This, in turn, contributes to the production of PGE₂, leukotrienes, lipoxins, and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, which can initiate the inflammatory (39). Metalloproteinases, on the other hand, stimulate the release of inflammatory mediators such as ICAM-1, IL-8, TNF-α, and MCP-1 from endothelial cells, leading to apoptosis. Meanwhile, cysteine-rich secretory protein increases the expression of IL-6 and plays a role in sustaining inflammation (39). Snake venom can also directly affect endothelial cells by delaminating the endothelial monolayer from the underlying matrix and disrupting endothelial cell membranes (40). Another important mechanism to highlight regarding snake venom is the production of reactive oxygen species, which, when accumulated, induce oxidative stress. Free radicals can damage cellular DNA, leading to cell dysfunction, cell cycle arrest, and cell death. Hydrogen peroxide has been shown to increase the activity of caspases and pro-apoptotic enzymes, cause the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, and degrade DNA (41–43).

Regarding treatment, this typically includes anti-venom therapy, hemodynamic support, and treatment of the specific cause if applicable. It has been suggested that anti-venom therapy alone may be sufficient for snakebites with cardiac involvement. According to Bhatt et al., in their case report, a resolution of bundle branch block following snakebite was evident with anti-venom therapy (44).

3.2 Acute kidney injury after snakebite

At the renal level, histopathological changes secondary to a snakebite have been observed, including acute cortical necrosis, thrombotic microangiopathy, diffuse mesangial proliferation, isolated glomerular thrombosis, acute tubular necrosis, acute interstitial nephritis, pigment-induced nephropathy, necrotizing arteritis, and thrombophlebitis (45). An observational study of 184 patients following a hemotoxic snakebite demonstrated higher mortality rates in patients with stage 3 AKI, according to the KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) scale [relative risk (RR) 4.45 (95% CI 1.14–17.42)] (46). Additionally, a study conducted at the HGMVI showed that out of 147 patients who suffered a snakebite, 2 patients developed acute kidney injury (5).

Among the factors associated with the development of AKI, the following have been identified: age, body surface area, the age of the snake, amount of venom inoculated, potency and composition of the venom, bite location, time between the accident and the administration of anti-venom, hospitalization duration, hypotension, prolonged coagulation times, anemia, hyperbilirubinemia, elevated LDH, hypoalbuminemia, leukocytosis, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (47, 48). Furthermore, the presence of comorbidities increases the susceptibility of patients to the venom, including arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, and underlying kidney disease (47). This patient, in particular, was identified as having hypertension and diabetes mellitus, which were not under medical treatment.

On the other hand, it is important to highlight two concepts. The first is the cardiorenal syndrome, which encompasses a wide range of interrelated disorders that may be acute or chronic, with the heart or kidneys as the primary affected organs, thus emphasizing the bidirectional nature of cardiorenal interactions (49). Both type 1 and type 2 cardiorenal syndromes lead to kidney injury. This occurs because, when fluid overload develops as a result of worsening cardiac function, venous pressure increases and is transmitted to the efferent arterioles, causing a decrease in glomerular filtration pressure and kidney injury (50). Moreover, when cardiac output and mean arterial pressure decrease, renal blood flow is reduced, which activates the renin–angiotensin system, reduces nitric oxide in the endothelium, activates the sympathetic nervous system, and induces inflammatory mediators. All of these factors cause structural and functional damage to both the kidneys and the heart (51). In addition, oxidative stress triggers the release of IL-6, IL-1, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, impairing renal compensatory mechanisms (52).

The second is the cardiovascular-renal-metabolic syndrome, a disorder attributable to the relationship between obesity, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular diseases (57). It has been described that when diabetes mellitus and hypertension coexist (as in the case of this patient with untreated type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension), their impact on the kidneys becomes even more severe (53). This is because hyperglycemia stimulates the production of reactive oxygen species, leading to oxidative stress and the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). Moreover, AGEs interact with receptors for advanced glycation end products on vascular and renal cells, contributing to tissue stiffening and the activation of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic mechanisms (53).

It is estimated that approximately one in five patients with acute heart disease has experienced acute kidney injury or worsening of renal function. Moreover, cardiovascular disease accounts for more than half of all deaths in patients with cardiorenal syndrome—10 to 20 times more than in individuals of the same age without this syndrome (52, 54). The management of cardiorenal syndrome focuses on addressing the underlying etiology and improving the syndrome’s complications. In individuals who exhibit a positive diuretic response, every effort should be made to achieve fluid removal using diuretics, either through continuous infusion or intravenous bolus administration (50, 54). Additionally, inotropic agents can be used in refractory cases and may even help improve cardiac function and reduce venous congestion (50). In the case of cardiorenal metabolic syndrome, treatment includes lifestyle modifications, dietary intervention, and increased physical activity aimed at achieving weight loss. In addition to addressing comorbidities associated with cardiovascular, renal, and metabolic conditions, the use of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists has been shown to be effective in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (55). Optimal blood pressure levels (<130/80 mmHg) should also be maintained in these patients, for which ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) can be used (55).

The treatment for managing acute kidney injury after a snakebite is based on anti-venom therapy, along with the reduction of nitrogen and hyperkalemia, which in most cases requires dialysis therapy (56). Additional measures include maintaining adequate blood pressure levels and avoiding compartment syndrome, the latter due to the risk of metabolic acidosis and rhabdomyolysis (2, 19).

4 Conclusion

Complications from snakebites, both cardiovascular and renal, are rare but potentially fatal without early detection and timely treatment. Additionally, it is important to note that factors such as the patient’s underlying diseases contribute to worsening the complications caused by the snakebite, and in this case, the patient’s conditions were even untreated. Early administration of antivenom remains the cornerstone of treatment, along with comprehensive and multidisciplinary monitoring and management of complications, which, as observed in this case report, occurred simultaneously.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

EG-C: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. AP-P: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. HO-C: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. NO: Writing – original draft. GG-C: Writing – original draft. MR: Writing – review & editing. JV-G: Writing – review & editing. EO-P: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

WHO . Snakebite. Geneva: WHO (2024).

2.

Sarkar S Sinha R Chaudhury AR Maduwage K Abeyagunawardena A Bose N et al . Snake bite associated with acute kidney injury. Pediatr Nephrol. (2021) 36:3829–40. doi: 10.1007/s00467-020-04911-x

3.

Angel-Camilo K. L. Guerrero-Vargas J. A. Carvalho E. F. de Lima-Silva K. de Siqueira R. J. B. Freitas L. B. N. et al . (2020). Disorders on cardiovascular parameters in rats and in human blood cells caused by Lachesis acrochorda snake venom. Toxicon, 184, 180–191. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2020.06.009

4.

Senise LV Yamashita KM Santoro ML . Bothrops jararaca envenomation: pathogenesis of hemostatic disturbances and intravascular hemolysis. Exp Biol Med. (2015) 240:1528–36. doi: 10.1177/1535370215590818

5.

Calvopiña M Guamán-Charco E Ramírez K Dávalos F Chiliquinga P Villa-Soxo S et al . Epidemiología y características clínicas de las mordeduras de serpientes venenosas en el norte de la Amazonía del Ecuador (2017-2021). Biomedica. (2023) 43:93–106. doi: 10.7705/biomedica.6587

6.

MSP . Dirección Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica. Quito: Ministerio de Salud Pública (2024).

7.

MSP . Manual de normas y procedimientos sobre prevención y tratamiento de accidentes ocasionados por mordedura de serpientes. Quito: MSP (2008).

8.

Bastidas AAR Flórez MA Muñoz JAH Ramírez MG Piedrahita DRE . Insuficiencia cardíaca secundaria a mordedura de serpiente. La visión del intensivista: Reporte de caso. Rev Fac Med Hum. (2024) 24:179–85.

9.

Liblik K Byun J Saldarriaga C Perez GE Lopez-Santi R Wyss FQ et al . Snakebite envenomation and heart: systematic review. Curr Probl Cardiol. (2022) 47:100861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2021.100861

10.

Pouokam I Temgoua MN Tcheunkam LW Tochie JN . Electrocardiography patterns of snake envenomations. PAMJ-One Health. (2020) 2:917. doi: 10.11604/pamj-oh.2020.2.23.24917

11.

Varuni K Sivansuthan S Pratheepan G Gajanthan S . A case report on bradycardia: A rare manifestation of saw scaled viper bite. Jaffna Med J. (2019) 31:37–9. doi: 10.4038/jmj.v31i1.66

12.

Kim OH Lee JW Kim HI Cha K Kim H Lee KH et al . Adverse cardiovascular events after a venomous snakebite in Korea. Yonsei Med J. (2016) 57:512–7. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2016.57.2.512

13.

Isbister GK Isoardi KZ Chiew AL Jenkins S Buckley NA . Early cardiovascular collapse after envenoming by snakes in Australia, 2005–2020: an observational study (ASP-31). Med J Aust. (2025) 222:313–7. doi: 10.5694/mja2.52622

14.

Agarwal R Singh AP Aggarwal AN . Pulmonary oedema complicating snake bite due to Bungarus caeruleus. Singapore Med J. (2007) 48:e227–30.

15.

Chippaux J-P Madec Y Amta P Ntone R Noël G Clauteaux P et al . Snakebites in Cameroon by species whose effects are poorly described. Trop Med Infect Dis. (2024) 9:300. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed9120300

16.

Pillai LV Ambike D Husainy S Khaire A Captain A Kuch U . Severe neurotoxic envenoming and cardiac complications after the bite of a “Sind krait” (Bungarus cf. Sindanus) in Maharashtra, India. Trop Med Health. (2012) 40:103–8. doi: 10.2149/tmh.2012-08c

17.

Sriranga R Sudhakar P Shivakumar B Shankar S Manjunath CN . Acute coronary syndrome from Green Snake envenomation. J Emerg Med. (2021) 60:355–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.10.024

18.

Virmani S Bhat R Rao R Kapur R Dsouza S . Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation due to venomous snake bite. J Clin Diagn Res. (2017) 11:OD01–2. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/27553.9971

19.

Zuluaga Gomez M Gómez López JC Berrouet Mejía MC . Lesión Renal Aguda con requerimiento de terapia de reemplazo renal secundario a accidente bothrópico: A propósito de un caso. Rev Toxicol. (2022) 39:11–5.

20.

Abukamar A Abudalo R Odat M Al-Sarayreh M Issa MB Momanie A . Arabian levantine viper bite induces thrombocytopenia—a case report. J Med Life. (2022) 15:867–70. doi: 10.25122/jml-2021-0283

21.

Zhang C Zhang Z Liang E Gao Y Li H Xu F et al . Platelet Desialylation is a novel mechanism and therapeutic target in Daboia siamensis and Agkistrodon halys envenomation-induced thrombocytopenia. Molecules. (2022) 27:7779. doi: 10.3390/molecules27227779

22.

Noutsos T Currie BJ Isoardi KZ Brown SGA Isbister GK . Snakebite-associated thrombotic microangiopathy: an Australian prospective cohort study [ASP30]. Clin Toxicol. (2022) 60:205–13. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2021.1948559

23.

Enjeti AK Lincz LF Seldon M Isbister GK . Circulating microvesicles in snakebite patients with microangiopathy. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. (2018) 3:121–5. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12164

24.

Etaee F Hesselson AB . A patient with severe bradycardia five years after copperhead snake bite. Intern Med Med Investig J. (2019) 4:1–3.

25.

Simões LO Alves QL Camargo SB Araújo FA Hora VRS Jesus RLC et al . Efecto cardíaco inducido por el veneno de Crotalus durissus cascavella: Evidencia morfofuncional y mecanismo de acción. Toxicol Lett. (2021) 337:121–33. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2020.11.019

26.

John Binu A Kumar Mishra A Gunasekaran K Iyadurai R . Cardiovascular manifestations and patient outcomes following snake envenomation: A pilot study. Trop Dr. (2019) 49:10–3. doi: 10.1177/0049475518814019

27.

Cao D Domanski K Hodgman E Cardenas C Weinreich M Hutto J et al . Thromboelastometry analysis of severe north American pit viper-induced coagulopathy: A case report. Toxicon. (2018) 151:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2018.06.079

28.

Averin AS Utkin YN . Cardiovascular effects of Snake toxins: cardiotoxicity and Cardioprotection. Acta Nat. (2021) 13:4–14. doi: 10.32607/actanaturae.11375

29.

Petko B Tadi P . Neuroanatomy, nucleus Ambiguus. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing (2025).

30.

Lertwanakarn T Suntravat M Sanchez EE Boonhoh W Solaro RJ Wolska BM et al . Suppression of cardiomyocyte functions by β-CTX isolated from the Thai king cobra (Ophiophagus hannah) venom via an alternative method. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis. (2020) 26:e20200005. doi: 10.1590/1678-9199-JVATITD-2020-0005

31.

Rajagopalan N Pung YF Zhu YZ Wong PTH Kumar PP Kini RM . Beta-cardiotoxin: A new three-finger toxin from Ophiophagus hannah (king cobra) venom with beta-blocker activity. FASEB J. (2007) 21:3685–95. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8658com

32.

Messadi E . Snake venom components as therapeutic drugs in ischemic heart disease. Biomolecules. (2023) 13:1539. doi: 10.3390/biom13101539

33.

Shah K Seeley S Schulz C Fisher J Gururaja Rao S . Calcium channels in the heart: disease states and drugs. Cells. (2022) 11:943. doi: 10.3390/cells11060943

34.

Ángel-Camilo KL Bueno-Ospina ML Bolaños Burgos IC Ayerbe-González S Beltrán-Vidal J Acosta A et al . Cardiotoxic effects of Lachesis acrochorda Snake venom in anesthetized Wistar rats. Toxins. (2024) 16:377. doi: 10.3390/toxins16090377

35.

Gupta P Mahajan N Gupta R Gupta P Chowdhary I Singh P et al . Cardiotoxicity profile of snake bite. JK Sci. (2013) 15:169–73.

36.

Greene SC Osborn L Bower R Harding SA Takenaka K . Monocled cobra (Naja kaouthia) Envenomations requiring mechanical ventilation. J Emerg Med. (2021) 60:197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.10.014

37.

Sachett JAG Mota da Silva A Dantas AWCB Dantas TR Colombini M Moura da Silva AM et al . Cerebrovascular accidents related to snakebites in the Amazon—two case reports. Wilderness Environ Med. (2020) 31:337–43. doi: 10.1016/j.wem.2020.04.009

38.

Sartim MA Raimunda da Costa M Bentes KO Mwangi VI Pinto TS Oliveira S et al . Lesión miocárdica y su asociación con la coagulopatía inducida por veneno tras el envenenamiento por mordedura de serpiente Bothrops atrox. Toxicon. (2025) 258:108312. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2025.108312

39.

Luo P Ji Y Liu X Zhang W Cheng R Zhang S et al . Affected inflammation-related signaling pathways in snake envenomation: A recent insight. Toxicon. (2023) 234:107288. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2023.107288

40.

Bittenbinder MA Bonanini F Kurek D Vulto P Kool J Vonk FJ . Using organ-on-a-chip technology to study haemorrhagic activities of snake venoms on endothelial tubules. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:11157. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-60282-5

41.

Bittenbinder MA van Thiel J Cardoso FC Casewell NR Gutiérrez J-M Kool J et al . Tissue damaging toxins in snake venoms: mechanisms of action, pathophysiology and treatment strategies. Commun Biol. (2024) 7:358. doi: 10.1038/s42003-024-06019-6

42.

Pavuluri LA Bitla AR Vishnubotla SK Rapur R . Oxidative stress, DNA damage, inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in snakebite-induced acute kidney injury. Indian J Nephrol. (2025) 35:349–54. doi: 10.25259/ijn_545_23

43.

Resiere D Mehdaoui H Neviere R . Inflammation and oxidative stress in snakebite envenomation: A brief descriptive review and clinical implications. Toxins. (2022) 14:802. doi: 10.3390/toxins14110802

44.

Bhatt A Menon AA Bhat R Ramamoorthi K . Myocarditis along with acute ischaemic cerebellar, pontine and lacunar infarction following viper bite. BMJ Case Rep. (2013) 2013:bcr2013200336. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-200336

45.

Meena P Bhargava V Gupta P Panda S Bhaumik S . The kidney histopathological spectrum of patients with kidney injury following snakebite envenomation in India: scoping review of five decades. BMC Nephrol. (2024) 25:112. doi: 10.1186/s12882-024-03508-y

46.

Priyamvada PS Jaswanth C Zachariah B Haridasan S Parameswaran S Swaminathan RP . Prognosis and long-term outcomes of acute kidney injury due to snake envenomation. Clin Kidney J. (2019) 13:564–70. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfz055

47.

Abuabara-Franco E Rico-Fontalvo JE Leal-Martínez V Pájaro-Galvis N Bohórquez-Rivero J Barrios N d J et al . Lesión renal aguda secundaria a mordedura de serpiente del género bothrops: A propósito de un caso. Rev Colomb Nefrol. (2022) 9:536. doi: 10.22265/acnef.9.1.536

48.

Dharod MV Patil TB Deshpande AS Gulhane RV Patil MB Bansod YV . Clinical predictors of acute kidney injury following snake bite envenomation. North Am J Med Sci. (2013) 5:594–9. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.120795

49.

Ronco C Haapio M House AA Anavekar N Bellomo R . Cardiorenal syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2008) 52:1527–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.051

50.

Kousa O Mullane R Aboeata A . Cardiorenal syndrome. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing (2025).

51.

Ismail Y Kasmikha Z Green HL McCullough PA . Cardio-renal syndrome type 1: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Semin Nephrol. (2012) 32:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2011.11.003

52.

Peng X Zhang H-P . Acute Cardiorenal syndrome: epidemiology, pathophysiology, assessment, and treatment. Rev Cardiovasc Med. (2023) 24:40. doi: 10.31083/j.rcm2402040

53.

Mutruc V Bologa C Șorodoc V Ceasovschih A Morărașu BC Șorodoc L et al . Cardiovascular–kidney–metabolic syndrome: a new paradigm in clinical medicine or going back to basics?J Clin Med. (2025) 14:833. doi: 10.3390/jcm14082833

54.

Prastaro M Nardi E Paolillo S Santoro C Parlati ALM Gargiulo P et al . Cardiorenal syndrome: pathophysiology as a key to the therapeutic approach in an under-diagnosed disease. J Clin Ultrasound. (2022) 50:1110–24. doi: 10.1002/jcu.23265

55.

Sebastian SA Padda I Johal G . Cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome: A state-of-the-art review. Curr Probl Cardiol. (2024) 49:102344. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2023.102344

56.

Aroca-Martinez G Freja A Ruiz E Bautista E Navas E . Insuficiencia renal aguda inducida por mordedura de serpiente Bothrops. Salud Uninorte. (2014) 30:258–61.

57.

Ndumele CE Rangaswami J Chow SL Neeland IJ Tuttle KR Khan SS et al . Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Health: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation. (2023) 148:1606–35. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001184

Summary

Keywords

snakebite, sinus bradycardia, acute kidney injury, Viperidae, snakebite envenomation

Citation

Guamán-Charco ED, Paredes-Ponce A, Orellana-Chimbay H, Omares N, Guamán-Charco G, Rubio M, Vasconez-Gonzalez J and Ortiz-Prado E (2025) Sinus bradycardia and acute renal injury secondary to Viperidae snakebite: first case report. Front. Med. 12:1600067. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1600067

Received

25 March 2025

Accepted

22 July 2025

Published

04 August 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Isadora Sousa de Oliveira, University of São Paulo, Brazil

Reviewed by

Marco Aurelio Sartim, Universidade Nilton Lins, Brazil

Arun Rabindra Katwaroo, The University of the West Indies St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago

Karen Leonor Angel Camilo, University of Cauca, Colombia

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Guamán-Charco, Paredes-Ponce, Orellana-Chimbay, Omares, Guamán-Charco, Rubio, Vasconez-Gonzalez and Ortiz-Prado.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Esteban Ortiz-Prado, e.ortizprado@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.