Abstract

Importance:

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) are common causes of morbidity, with systemic risk factors shared. Clarifying the association between the two is crucial to guiding comprehensive management.

Objective:

This study aimed to systematically review current and latest evidence on the influence of CKD on AMD prevalence. An investigation was performed into various AMD stages and how different CKD severities exert their effects.

Data sources:

Databases of PubMed and Embase were searched from their inception to 11 November 2024. Reference lists of studies were reviewed, and relevant researchers were contacted. The study was accepted and registered with PROSPERO (CRD420250612669).

Study selection:

Eligible studies of the current review are observational, peer-reviewed, and include quantitative comparisons of AMD prevalence between populations with and without CKD. Studies with overlapping data or investigating AMD incidence were excluded. Twenty studies met the inclusion criteria from the 3,218 initially identified.

Data extraction and synthesis:

We extracted data and assessed study quality using the Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS) tool for cross-sectional studies. Our meta-analyses followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines and were conducted with Review Manager 5.4.1. Risk of bias was evaluated using the AXIS quality appraisal tool, and the overall certainty of evidence was qualitatively assessed following the GRADE approach.

Main outcomes and measures:

Primary outcomes are the prevalence of all-stage, early-stage, and late-stage AMD among CKD and non-CKD patients. Secondary outcomes investigated AMD prevalence among patients with different CKD stages. We reported in our analyses the risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results:

All-stage AMD prevalence was found to be higher among CKD patients (RR: 1.65; 95% CI: 1.49–1.83). Similarly, early-stage AMD was more prevalent among CKD patients (RR: 1.47; 95% CI: 1.26–1.71). In late-stage AMD, an even stronger association was shown (RR: 3.72; 95% CI: 2.14–6.45). Meanwhile, there was no significant difference in AMD prevalence between moderate and advanced CKD stages (RR: 1.08; 95% CI: 0.48–2.46).

Conclusion and relevance:

Our findings indicate that CKD is significantly associated with higher AMD prevalence. These findings suggest the effects of shared systemic mechanisms and underscore the need for ophthalmic screening in CKD patients. Further studies are needed to strengthen causality and expand generalizability beyond the Asian population.

Systematic review registration:

The systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD420250612669).

1 Introduction

The macula is the part of the retina with the highest concentration of cone photoreceptor cells, which are fundamental to central vision (1). Age-related macular degeneration (AMD), or simply macular degeneration, affects one in eight individuals aged 60 years or older (2) and is recognized as one of the leading causes of irreversible blindness globally (3). Early AMD is manifested by a slow and progressive degeneration of the retinal pigment epithelium and photoreceptors, with drusen and pigmentary changes. Late AMD, on the other hand, is manifested by geographical atrophy (dry AMD) or neovascularization (wet AMD) (4, 5).

By the year 2021, more than 850 million people were estimated suffer from some form of kidney disease, as indicated by a joint statement from the American Society of Nephrology, European Renal Association, and International Society of Nephrology (6). According to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline, chronic kidney disease (CKD) is defined as abnormalities of kidney structure or function, present for a minimum of 3 months, with implications for health (6). Both as end-organ targets of systemic diseases, the comorbidity of the kidney and eye has been linked to factors such as diabetes, hypertension, and uremia (7, 8). As a result, the relationship between AMD and CKD has become a focus of research in many studies. CKD features the accumulation of uremic toxins (e.g., indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate) that drive endothelial dysfunction, vascular calcification, and pro-inflammatory signaling in the vasculature (9, 10). In AMD, oxidative stress-driven retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) dysfunction with impaired phagocytosis/autophagy and disturbed angiogenic responses are key pathological processes (11). Mendelian randomization evidence further links systemic inflammatory regulators with AMD risk (12). Together, these systemic and retinal alterations provide a plausible mechanistic bridge between impaired renal clearance and retinal degeneration (13). Two previous reviews (3, 14) have provided insight into the correlation between the two diseases. However, there exists a need for a meta-analytic update since both reviews included studies that the other did not, and there are relevant studies never included in previous reviews (15, 16).

Hence, the objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to review the latest clinical evidence on the relationship between AMD and CKD (measured in eGFR) and to provide a comprehensive conclusion for relevant clinical care providers.

2 Methods

2.1 Data sources

Relevant studies were retrieved from PubMed and Embase databases that were published from the inception of the databases to 11 November 2024, irrespective of language. In addition, the Cochrane Library was screened to identify relevant systematic reviews and to cross-check reference lists for completeness. This supplementary search was reflected in the PRISMA flow diagram for transparency. However, systematic reviews themselves were not included in the quantitative synthesis; only original observational studies were analyzed.

While searching for eligible studies, we applied the following search terms and medical subject headings in various combinations: “macular degeneration,” “age-related macular degeneration,” “age-related maculopathy,” “kidney,” “renal,” and “chronic kidney disease.” Furthermore, the reference sections of retrieved studies were manually investigated, and known researchers with relevant expertise were contacted. The current systematic review and meta-analysis was prospectively registered in the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD420250612669). No separate review protocol was publicly posted prior to data collection, and no major deviations from the registered protocol were made during the review process. PICOS question and objective. The research question was structured according to the PICOS framework: P (Population): adults with chronic kidney disease (CKD); I (Exposure): reduced renal function measured by estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) or a clinical diagnosis of CKD; C (Comparator): individuals without CKD or with normal renal function; O (Outcome): presence or stage of age-related macular degeneration (AMD); and S (Study design): observational studies (cross-sectional, case–control, or cohort). Accordingly, the objective of this review was to quantify the association between CKD and AMD across disease stages using meta-analytic synthesis. Definition of eGFR. The term eGFR refers to estimated glomerular filtration rate, a standard indicator of kidney function derived from serum creatinine-based equations [e.g., Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) or Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD)].

With regard to studies from the Asian Eye Epidemiology Consortium (AEEC), data were derived from a previously published systematic review by Rim et al., which synthesized epidemiologic findings from the AEEC cohorts. From this review, 10 eligible studies were identified and included in our meta-analysis (17).

2.2 Study selection

We included studies that provided a quantitative comparison of AMD prevalence between populations with and without CKD. We excluded studies based on the following criteria: overlapping patient cohorts in two or more studies with identical outcomes or studies focused on the incidence of AMD.

All records were screened independently at each stage following predefined eligibility criteria. Disagreements during study selection were resolved through consensus, with arbitration applied when necessary. Data extraction was conducted independently and cross-checked to ensure consistency and accuracy.

2.3 Data extraction and quality assessment

Potentially eligible studies were initially screened based on their article titles and abstracts. Then, their full-text versions were retrieved for further evaluation. Two independent reviewers (Ting-Han Lin and Peng-Tai Tien) assessed studies for inclusion. They extracted the study data using a standardized procedure, while a third reviewer (Lei Wan) assisted in resolving disagreements and discrepancies. We contacted the study authors for additional information as needed.

Data on the study design, patient characteristics (e.g., gender, age, and diagnosis of AMD), the definition of CKD, and analytical outcomes were extracted. Using the Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS), Ting-Han Lin performed the risk-of-bias analysis for the included studies. Extracted variables also included sample size, geographic region, study year, AMD classification (early, late, or overall), CKD stage based on eGFR thresholds, and laboratory indicators such as serum creatinine or estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) used to define CKD status.

2.4 Data synthesis and analysis

Studies that investigated the relationship between the disease status of CKD and AMD were assessed in separate meta-analyses. Since there are studies that did not explicitly indicate their definition of CKD, we universally applied “eGFR <60” to the CKD group and “eGFR ≥60” to the non-CKD group (shown in Table 1). Subgroups were introduced to provide elucidation on the effects of CKD on the various stages of AMD and whether the severity of CKD affects the prevalence of AMD. Our primary outcomes include the comparisons between CKD and non-CKD patients on the prevalence of all-stage, early-stage, and late-(advanced)stage AMD. Our secondary outcome compared between the moderate stage and advanced stage of CKD on the prevalence of AMD.

Table 1

| Author [Year] | Study design | Male, n (%) | Age, year, mean ± SD | Diagnosis of AMD | Type of AMD | Exposure (CKD Definition) | Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neelamegam 2024 | Cross-sectional |

eGFR >60: 1944 (45.9) eGFR <60: 166 (29.8) |

eGFR >60: 65.49 ± 5.98 eGFR <60: 68.40 ± 7.01 |

Grading as per the International ARM Epidemiological Study Group | Early, Dry, Wet | eGFR <60 (Moderate to severe CKD) |

eGFR >60 (No to mild CKD) |

| Jung 2023 | Data used: Cross-sectional; Initial design: Retrospective cohort |

Non-AMD: 2013798 (48.5) AMD: 22783 (42.5) |

Non-AMD: 60.6 ± 8.3 AMD: 67.4 ± 8.4 |

ICD-10 | AMD with VD, AMD without VD | †eGFR <60 | †eGFR ≥60 |

| Zhu 2020 | Cross-sectional | 2762 (50.1) | 56.9 ± 0.40 (SE) | Modified Wisconsin Age-Related Maculopathy Grading Classification Scheme | Any | eGFR <60 | eGFR ≥60 |

| Chen 2017 | Cross-sectional | 79,175 (51.59) | 54.9 ± 15.7 | ICD-9 | Any, advanced | Adult w/ ICD-9 diagnosis of CKD (excluding advanced CKD, dialysis or renal transplantation) |

Non-CKD |

| Chong 2014 | Cross-sectional |

Cystatin C level

Top decile: 367 (51.6) Bottom nine deciles: 2858 (46.8) |

Cystatin C level

Top decile: 70.0 ± 9.5 Bottom nine deciles: 61.4 ± 10.0 |

Early: either presence of any soft drusen and pigmentary abnormalities or reticular drusen, in the absence of signs of late end-stage AMD | Early | eGFR ≤60 | eGFR >60 |

| Choi 2011 | Cross-sectional | Non-CKD: 1482 (62.4) CKD: 343 (54.2) |

Non-CKD: 56.7 ± 6.3 CKD: 62.1 ± 7.5 |

Modification of the Wisconsin AMD Grading System | Early | eGFR ≤60 | eGFR >60 |

| Deva 2011 | Cross-sectional | CKD Stages 3 to 5: 96 (64) CKD Stages 1 to 2: 96 (64) |

Median=62 (range 20 to 85) | Graded by an ophthalmologist and trained observer | Any, severe | CKD Stages 3 to 5 (eGFR <60 for at least 3 mth) |

CKD Stages 1 to 2 (eGFR ≥60) |

| Gao 2011 | Cross-sectional | 5941 (61.6) | 52.8 ± 16.0 | Large drusen and pigmentary changes on ophthalmoscopes | Any | eGFR <60 and/or proteinuria | Non-CKD |

| Weiner 2011 | Cross-sectional | 3695 (48.2) | 59.3 ± 13.1 |

Early: either soft drusen (≥63μm, consistent w/ Grade 3 drusen in WARMGS) or any drusen type w/ areas of depigmentation/hypopigmentation of retinal pigment epithelium w/o any visibility of choroidal vessels or w/ increased retinal pigment in macular area Late: signs of exudative macular degeneration or geographic atrophy |

Early, Late | †eGFR <60 | †eGFR ≥60 |

| Nitsch 2009 | Cross-sectional | 1292 (44.9) | N/A (aged 75 years or over) | Did not mention | eGFR <60 | eGFR ≥60 | |

| BES | Cross-sectional | 646 (41.3) | 64.4± 9.6 | Modified WARMGS | Any, early, late | eGFR <60 | eGFR ≥60 |

| CIEMS | Cross-sectional | 2160 (46.5) | 49.4± 13.4 | Modified WARMGS | Any, early, late | eGFR <60 | eGFR ≥60 |

| HDES | Cross-sectional | 2089 (44.8) | 50.9± 10.6 | Modified WARMGS | Any, early, late | eGFR <60 | eGFR ≥60 |

| KNHANES | Cross-sectional | 7374 (43.0) | 57.5± 11.4 | International classification and grading system for age-related maculopathy and AMD | Any, early, late | eGFR <60 | eGFR ≥60 |

| SCES | Cross-sectional | 1580 (50.1) | 59.3± 9.7 | Modified WARMGS | Any, early, late | eGFR <60 | eGFR ≥60 |

| SiMES | Cross-sectional | 1464 (48.3) | 58.8± 10.9 | Modified WARMGS | Any, early, late | eGFR <60 | eGFR ≥60 |

| SINDI | Cross-sectional | 1617 (50.9) | 57.4± 9.9 | Modified WARMGS | Any, early, late | eGFR <60 | eGFR ≥60 |

| SNDREAMS | Cross-sectional | 2110 (44.0) | 65.8± 6.2 | Beckman Initiative for Macular Research | Any, early, late | eGFR <60 | eGFR ≥60 |

| TMCS | Cross-sectional | 2154 (54.3) | 62.4± 7.5 | Modified WARMGS | Any, early, late | eGFR <60 | eGFR ≥60 |

| UEMS | Cross-sectional | 2044 (40.1) | 58.7± 10.6 | Beckman Initiative for Macular Research | Any, early, late | eGFR <60 | eGFR ≥60 |

Characteristics of included trials.

Abbreviations: ARM: age-related maculopathy; BES = Beijing Eye Study; CIEMS = Central India Eye and Medical Study; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate (unit in ml/min/1.73 m2) ; HDES = Handan Eye Study; ICD- 9=International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision; ICD-10=International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision; KNHANES = Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; SiMES = Singapore Malay Eye Study; SINDI = Singapore Indian Eye Study; SCES = Singapore Chinese Eye Study; SNDREAMS = Sankara Nethralaya-Diabetic Retinopathy Epidemiology and Molecular Genetic Study; TMCS = Tsuruoka Metabolomics Cohort Study; UEMS = Ural Eye and Medical Study; VD = visual disability; WARMGS: Wisconsin Age-related Maculopathy Grading System

Defined by the current study.

We calculated risk ratios (RRs) by dividing the prevalence of AMD in the CKD (or advanced CKD) group by that in the non-CKD (or moderate CKD) group. We also computed 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for these values. We used the Review Manager statistical package (version 5.4.1; The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020) to conduct all analyses. We followed the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (18). To assess heterogeneity across the studies, chi-square statistics and I2 tests were used. Random-effects models (DerSimonian–Laird) were applied when significant heterogeneity was detected (I2 > 50%); otherwise, fixed-effects models were used. Subgroup analyses (by ethnicity and study design) and leave-one-out sensitivity analyses were performed to assess robustness. Publication bias was examined using funnel plots and Egger’s test. The overall certainty of evidence was evaluated according to the GRADE framework, considering consistency, precision, and directness of results. Potential publication bias was assessed through the visual inspection of funnel plots and Egger’s regression test, although the limited number of included studies precluded definitive conclusions. The certainty of evidence for each outcome was qualitatively appraised based on consistency, precision, and directness of results, referencing the GRADE framework. As all included studies were observational, the overall certainty was rated as low to moderate.

3 Results

3.1 Characteristics of the included studies

Our initial search yielded 3,218 articles, of which 948 were duplicate records and were excluded (Figure 1). Screening excluded 1,743 articles that were judged to be non-relevant. Of the 527 remaining articles, 507 failed to meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded. Therefore, 20 studies were eligible for our meta-analysis (3, 15, 16, 19–26).

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection. Summary of identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and final inclusion of 20 observational studies evaluating the association between chronic kidney disease (CKD) and age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

All except one (16) included studies are cross-sectional studies. While the one different study (16) was initially designed as a retrospective cohort; their data were applicable in our analysis as a cross-sectional study. Therefore, all included studies were analyzed as cross-sectional studies (Table 1). Most of the included studies stated their compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, except for three studies (27–29). As Chen (29) used deidentified secondary data from the National Health Insurance (NHI) dataset; the study was exempted from institutional review board review.

Notably, 10 studies, including the Beijing Eye Study and Singapore Chinese Eye Study, were within the Asian Eye Epidemiology Consortium (AEEC). Since the majority of the data were provided to the AEEC but not published, we retrieved them from a previously conducted systematic review (3).

3.2 Risk-of-bias assessment

An evaluation of the methodological quality of the included studies using the AXIS tool’s 20-item checklist can be found in Table 2. Each study was assessed across criteria such as clarity of objectives, representativeness of the population base, adequacy of statistical reporting, and reporting of ethical approval and patient consent. While most studies demonstrate strengths in fields such as clearly defined objectives and appropriate study designs, their common limitation is most remarkable in the lack of justification for sample size. Notably, 10 studies within the AEEC were marked with “Not Applicable” across many items, reflecting the limited availability of the unpublished data.

Table 2

| Author [Year] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Neelamegam 2024 | Y | Y | N | Y | ? | ? | N | Y | ? | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Jung 2023 | Y | Y | N | ? | ? | ? | NA | Y | ? | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | Y | NA | Y | Y | N | Y, NA |

| Zhu 2020 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Chen 2017 | Y | Y | N | Y | ? | ? | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA |

| Chong 2014 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | ? | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Choi 2011 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y, N |

| Deva 2011 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y | ? | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y |

| Gao 2011 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ? | ? | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Weiner 2011 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | ? | Y | Y | Y | N | ? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Nitsch 2009 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | ? | Y | Y | ? | Y | ? | N | N | Y | Y | ? | N | Y | N | Y, N |

| BES | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Y |

| CIEMS | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Y |

| HDES | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Y |

| KNHANES | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Y |

| SCES | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Y |

| SiMES | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Y |

| SINDI | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Y |

| SNDREAMS | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Y |

| TMCS | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Y |

| UEMS | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Y |

Risk-of-bias assessment with AXIS (color-coded summary of individual studies).

Abbreviations: BES = Beijing Eye Study; CIEMS = Central India Eye and Medical Study; HDES = Handan Eye Study; KNHANES = Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; N=No; NA=Not applicable; SiMES = Singapore Malay Eye Study; SINDI = Singapore Indian Eye Study; SCES = Singapore Chinese Eye Study; SNDREAMS = Sankara Nethralaya-Diabetic Retinopathy Epidemiology and Molecular Genetic Study; TMCS = Tsuruoka Metabolomics Cohort Study; UEMS = Ural Eye and Medical Study; Y=Yes; ?=Unclear; Color codes indicate the level of risk of bias across AXIS domains: green = low risk, yellow = unclear, red = high, gray = not applicable.

†<20% non-responder = low (No for bias); 20–30% non-responder = intermediate (Unclear for bias); >30% non-responder = high (Yes for bias).

3.3 Primary outcomes

3.3.1 Prevalence of all-stage AMD

Seventeen studies compared between CKD and non-CKD patients on the prevalence of all AMD stages. The meta-analysis revealed a significantly higher prevalence of all AMD stages for CKD patients than for those without CKD (RR: 1.65, 95% CI: 1.49–1.83, p < 0.00001; Figure 2).

Figure 2

![Forest plot showing risk ratios for CKD versus Non-CKD across various studies. Each study displays its events, total, weight percentage, and risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals. The combined risk ratio is 1.65 [1.49, 1.83]. Heterogeneity statistics include Tau² = 0.03, Chi² = 108.78, and I² = 85%. The overall effect is significant with Z = 9.48 and P < 0.00001.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1635766/xml-images/fmed-12-1635766-g002.webp)

Forest plot of all-stage AMD prevalence comparing CKD and non-CKD populations. Risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals showing a significantly higher prevalence of all-stage AMD in patients with CKD.

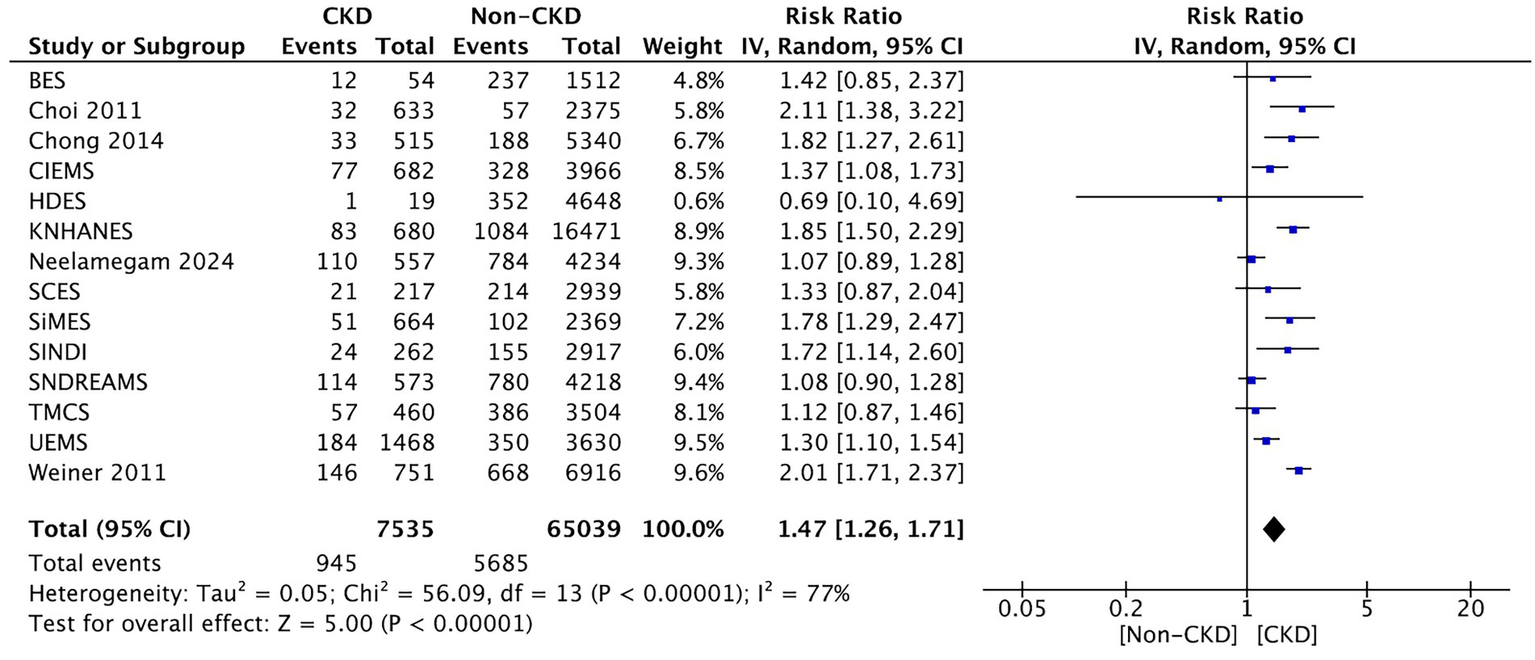

3.3.2 Prevalence of early-stage AMD

Thirteen studies compared between CKD and non-CKD patients on the prevalence of early-stage AMD. The meta-analysis revealed a significantly higher prevalence of early-stage AMD for CKD patients than for those without CKD (RR: 1.47, 95% CI: 1.26–1.71, p < 0.00001; Figure 3).

Figure 3

Forest plot of early-stage AMD prevalence comparing CKD and non-CKD populations. Meta-analysis results demonstrating increased early-stage AMD prevalence among CKD patients.

3.3.2.1 Subgroup analyses

Stratified results showed higher pooled risk in advanced CKD (eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2) than in moderate CKD (eGFR 30–59), particularly for late-stage AMD. By geographical region, East-Asian cohorts exhibited a comparable direction of effect to non-Asian cohorts, with overlapping CIs. The results were consistent across study designs (population-based vs. clinic-based), and leave-one-out analyses did not materially alter pooled estimates.

3.3.3 Prevalence of late-(advanced-)stage AMD

Fourteen studies compared between CKD and non-CKD patients on the prevalence of late-stage AMD. The term “severe macular degeneration,” which was found in one study (19), is considered equivalent to “late AMD” in the current study. The meta-analysis revealed a significantly higher prevalence of late-stage AMD in CKD patients than those without CKD (RR: 3.72, 95% CI: 2.14–6.45, p < 0.00001; Figure 4).

Figure 4

![Forest plot showing risk ratios comparing CKD versus non-CKD groups across multiple studies. Risk ratios and confidence intervals vary, with the overall risk ratio being 3.72 [2.14, 6.45]. Individual study results are plotted with blue squares and confidence intervals. Total events are 256 for CKD and 701 for non-CKD, with heterogeneity indicated by Tau² = 0.74, Chi² = 97.21, and I² = 87%. The test for overall effect shows Z = 4.67 (P < 0.00001).](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1635766/xml-images/fmed-12-1635766-g004.webp)

Forest plot of late-stage AMD prevalence comparing CKD and non-CKD populations. Summary of pooled RRs indicating a strong association between CKD and late-stage AMD.

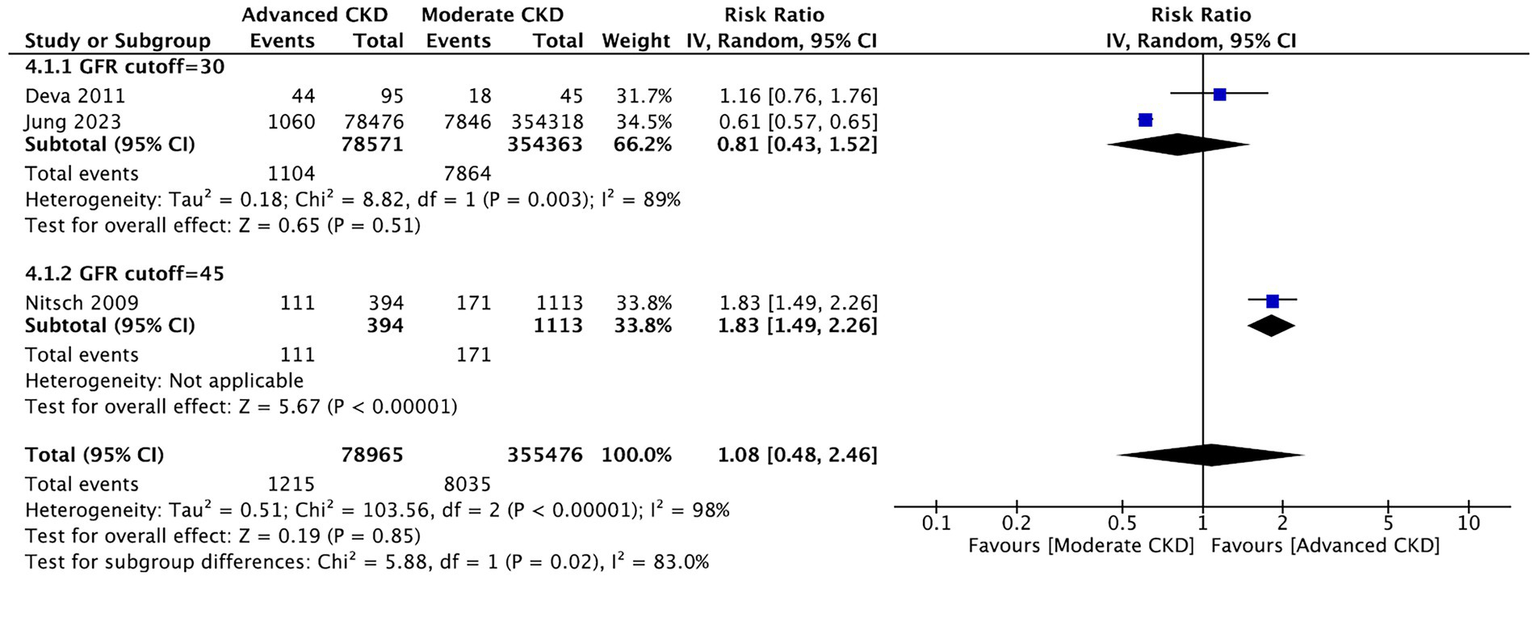

3.4 Secondary outcomes

3.4.1 Comparison between the moderate and advanced stages of CKD about the prevalence of AMD

Three studies compared between the moderate stage and advanced stages of CKD on the prevalence of AMD. We did not observe a significant difference in the prevalence of AMD between patients of moderate and advanced CKD stages (RR: 1.08, 95% CI: 0.48–2.46, p = 0.85; Figure 5). Sensitivity analyses excluding each study sequentially did not materially change the pooled estimates, indicating the robustness of the synthesized results. Additional analyses according to extracted variables (e.g., eGFR range, serum creatinine, and study region) demonstrated consistent directions of effect.

Figure 5

Comparison of AMD prevalence between moderate and advanced CKD stages. Forest plot showing no significant difference in AMD prevalence between moderate (eGFR 30–59) and advanced (eGFR <30) CKD groups.

4 Discussion

The current systematic and meta-analytic review indicates a positive relationship between the diseases of CKD and AMD. Our results revealed that, regardless of the AMD stages, the positive status of CKD was associated with a higher prevalence of AMD.

Clinically, this association underscores the importance of cross-disciplinary disease surveillance between nephrology and ophthalmology. CKD patients frequently exhibit systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial injury, all of which are also key contributors to retinal degeneration. Accordingly, regular ophthalmologic evaluations should be incorporated into the routine management of CKD, especially among elderly individuals or those with diabetes and hypertension. Early detection of subclinical AMD in this population may enable timely preventive interventions, such as lifestyle modification, antioxidant supplementation, and anti-inflammatory therapy, to delay disease progression.

From a mechanistic standpoint, CKD-related uremic toxins such as indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate can penetrate the blood–retinal barrier, promote oxidative injury, and compromise retinal pigment epithelium integrity. Dysregulation of the complement pathway, particularly involving complement factor D, is implicated in both CKD-associated chronic inflammation and AMD pathogenesis. Furthermore, endothelial dysfunction and microvascular calcification, which are frequently observed in CKD, may reduce choroidal perfusion and induce retinal hypoxia, ultimately contributing to photoreceptor loss.

Collectively, these findings suggest that a multidisciplinary approach involving nephrologists and ophthalmologists is warranted. For patients with declining renal function, routine retinal imaging and visual function assessment may allow an earlier diagnosis of AMD. Conversely, ophthalmologists managing AMD should be aware of the underlying renal impairment, as systemic inflammation and metabolic imbalance could influence treatment response and disease progression.

In addition to the diagnostic and preventive perspectives, potential therapeutic implications can also be derived from the shared pathophysiology of CKD and AMD. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory therapies have shown promise in attenuating oxidative injury in both renal and retinal tissues. Agents, such as N-acetylcysteine, vitamin E, and resveratrol analogs, may mitigate the accumulation of reactive oxygen species and improve endothelial function. Similarly, lifestyle modifications such as smoking cessation, dietary control, and optimization of blood pressure and glycemic status can synergistically protect both renal and ocular microvasculature.

Targeting the complement pathway is another emerging approach. Complement factor D inhibitors (e.g., lampalizumab and other anti-CFD biologics) have been demonstrated to reduce geographic atrophy progression in AMD, and comparable anti-complement strategies are under investigation in CKD to curb chronic inflammation. This overlap supports the notion that systemic complement regulation could simultaneously benefit both organs.

Moreover, endothelial-protective and renoprotective agents—such as SGLT2 inhibitors, renin–angiotensin system blockers, and nitric oxide–enhancing compounds—have been shown to improve vascular integrity in CKD populations, and such vascular benefits may extend to retinal microcirculation (30). Their potential to stabilize choroidal and retinal circulation may represent a promising therapeutic avenue for patients with dual CKD–AMD pathology.

Collectively, these findings emphasize that the management of CKD should not only be limited to renal endpoints alone but should also aim to preserve retinal health through systemic anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory strategies.

Common risk factors have been proposed to explain the co-existence of CKD and AMD, one of which is the action of complements on the inflammatory process. The complement factor D (CFD) is an activator of the alternative complement pathway. As CFD elevation is considered to be linked to chronic inflammation in CKD (31), CFD being identified as a possible target in the treatment of AMD (32) should explain the correlation between CKD and AMD. Recent mechanistic and clinical evidence further supports complement dysregulation and systemic inflammation as shared drivers of CKD–AMD pathology. A bidirectional Mendelian randomization study demonstrated that elevated systemic inflammatory regulators are causally associated with a higher risk of AMD, reinforcing the role of chronic inflammation beyond local retinal processes (12). Dysregulated activation of the complement cascade—particularly complement factor D—links renal and retinal microvascular inflammation, providing a unifying explanation for their coexistence.

In addition, phase 3 clinical data have confirmed the translational relevance of this pathway: the OAKS and DERBY trials showed that complement C3 inhibition with pegcetacoplan significantly slowed the progression of geographic atrophy secondary to AMD over 24 months (33). These findings highlight that complement-targeted therapy can effectively attenuate retinal degeneration and suggest that modulating complement activity may also benefit patients with concurrent CKD by mitigating inflammation-driven microvascular injury.

Indoxyl sulfate (IS) and p-cresol sulfate (PCS) are two protein-bound uremic toxins in CKD. They are reported to generate oxidative stress (9), endothelial dysfunction (10) and vascular calcification (34). From a structural perspective, the blood–retinal barrier (BRB) is made up of retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) cells and the retinal vessel endothelium. RPE cell functionality impairment, which is the hallmark of AMD, was indicated to arise from oxidative stress (11). Consistently, a bidirectional Mendelian randomization study linked systemic inflammatory regulators to AMD risk, reinforcing the plausibility that CKD-related systemic inflammation contributes to retinal degeneration (12). Where endothelial dysfunction is concerned, circulating endothelial cells, a potential biomarker for such a disorder (35), were suggested to possibly promote AMD (36). With regards to calcification, a pro-calcific environment hampers ischemia-driven angiogenesis (37). Thus, IS and PCS are expected to decrease angiogenesis, which, along with the subsequently decreased RPE cell survival, may lead to dry AMD (13). With the above considered, we speculate that the actions of IS and PCS are built on their ability to trespass the BRB, as a rat model reported that IS breaches the BRB and accumulates in the intraocular fluid (38), while another previous study showed that PCS damages the blood–brain barrier function, whose inner layer shares similarity with the BRB (39).

Another risk factor is the acceleration of atherosclerosis, which has been indicated in CKD due to multiple speculated mechanisms. These mechanisms include elevated serum homocysteine (40) and lipoprotein (41). With studies also supporting the connection between atherosclerosis and AMD (42, 43), it would be feasible to attribute the prevalence of AMD in CKD patients to the influence of atherosclerosis.

In the current review, no significant difference was observed in the prevalence of AMD between patients of moderate and advanced CKD stages (Figure 5), which is opposite to what we originally hypothesized. However, only three studies (16, 19, 20) were considered eligible for meta-analysis on this subtopic, and the current result appears to be lopsided by the large number of patients in one of the studies (16). Therefore, further analyses are required when more relevant studies that grade kidney functions become available.

To the best of our knowledge, there was only one previous meta-analysis that addressed the connection between CKD and AMD (14). Incorporating 12 observational studies (with 3 cohorts, 2 case controls, and 7 cross-sectionals), this study suggested a significant association between the 2 diseases.

There are several limitations to the current study. First, the majority of the included patients in our study are Asian, which restricted the generalizability of our article. Second, since we included only cross-sectional studies, the inherent weakness of our results is the causal inference. In addition, the review process was limited by the potential omission of gray literature and non-English-language publications, which may contribute to selection bias. Data extraction was performed by two reviewers, but no automation tools were used, which could introduce human error. Other causes that might result from the prevalence of AMD in the CKD population were not fully considered. Reviews that investigate the incidence of AMD in CKD are required to strengthen our findings. Finally, the influence of sex difference has not been investigated in the current study. The above limitations are expected to be addressed by future studies to provide a more comprehensive view of the current topic.

Furthermore, most of the included studies were conducted among Asian populations, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other ethnic or geographic groups. Differences in genetic background, dietary habits, and environmental exposures could alter both the prevalence and the strength of the CKD–AMD association. For example, risk variants in the CFH and ARMS2 genes show different allele frequencies between Asian and Western populations, potentially affecting susceptibility to AMD and the inflammatory response related to CKD. Therefore, caution should be exercised when extrapolating our results to non-Asian populations. Future large-scale studies incorporating multi-ethnic and regionally diverse cohorts are warranted to validate these findings and enhance external validity.

Based on our findings from the current study, we concluded that CKD is a risk factor for AMD. Our findings highlight the need for closer ophthalmic surveillance in patients with chronic kidney disease, especially among those with declining eGFR or metabolic comorbidities. Early fundus screening may facilitate timely detection and intervention for AMD in this population. Clinicians should also be aware that systemic inflammation and vascular dysfunction observed in CKD could modify the response to AMD therapy. Future research should validate these associations through longitudinal and multi-ethnic cohorts, integrating biochemical markers (e.g., complement factors and uremic toxins) and imaging biomarkers to clarify causal pathways and optimize individualized management strategies.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

T-HL: Investigation, Writing – original draft. Y-YL: Writing – review & editing. Y-TH: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Y-CH: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. P-TT: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. LW: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. H-JL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Research funding was provided in part by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, R.O.C. (MOST107-2320-B-039-049-MY3; 111-2314-B-039 -054-; 111-2314-B-039 -053-MY3; and NSTC-112-2314-B-039-029), the China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan (DMR-112-012; DMR-112-103), and Taichung Tzu Chi Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan (TTCRD 111-14).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Hobbs SD Tripathy K Pierce K . Wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing LLC (2024).

2.

Vyawahare H Shinde P . Age-related macular degeneration: epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Cureus. (2022) 14:e29583. doi: 10.7759/cureus.29583

3.

Xue CC Sim R Chee ML Yu M Wang YX Rim TH et al . Is kidney function associated with age-related macular degeneration? Findings from the Asian eye epidemiology consortium. Ophthalmology. (2024) 131:692–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2023.12.030

4.

Cheung CM Wong TY . Is age-related macular degeneration a manifestation of systemic disease? New prospects for early intervention and treatment. J Intern Med. (2014) 276:140–53. doi: 10.1111/joim.12227

5.

Fernandes AR Zielińska A Sanchez-Lopez E dos Santos T Garcia ML Silva AM et al . Exudative versus nonexudative age-related macular degeneration: physiopathology and treatment options. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23:2592. doi: 10.3390/ijms23052592

6.

Feng X Xu K Luo MJ Chen H Yang Y He Q et al . Latest developments of generative artificial intelligence and applications in ophthalmology. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). (2024) 13:100090. doi: 10.1016/j.apjo.2024.100090

7.

Nusinovici S Sabanayagam C Teo BW Tan GSW Wong TY . Vision impairment in CKD patients: epidemiology, mechanisms, differential diagnoses, and prevention. Am J Kidney Dis. (2019) 73:846–57. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.12.047

8.

Raja N Rajagopalan A Arunachalam J Prasath A Durai R Rajendran M . Uremic optic neuropathy: a potentially reversible complication of chronic kidney disease. Case Rep Nephrol Dial. (2022) 12:38–43. doi: 10.1159/000519587

9.

Liu WC Tomino Y Lu KC . Impacts of indoxyl Sulfate and p-cresol Sulfate on chronic kidney disease and mitigating effects of AST-120. Toxins (Basel). (2018) 10:367. doi: 10.3390/toxins10090367

10.

Stafim da Cunha R Gregorio PC Maciel RAP Favretto G Franco CRC Gonçalves JP et al . Uremic toxins activate CREB/ATF1 in endothelial cells related to chronic kidney disease. Biochem Pharmacol. (2022) 198:114984. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2022.114984

11.

Si Z Zheng Y Zhao J . The role of retinal pigment epithelial cells in age-related macular degeneration: phagocytosis and autophagy. Biomolecules. (2023) 13:901. doi: 10.3390/biom13060901

12.

Liu X Cao Y Wang Y Kang L Zhang G Zhang J et al . Systemic inflammatory regulators and age-related macular degeneration: a bidirectional mendelian randomization study. Front Genet. (2024) 15:1391999. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2024.1391999

13.

Venkatesh P . Hypo-angiogenesis: a possible pathological factor in the development of dry age-related macular degeneration and a novel therapeutic target. Med Hypothesis Discov Innov Ophthalmol. (2021) 10:185–90. doi: 10.51329/mehdiophthal1437

14.

Chen YJ Yeung L Sun CC Huang CC Chen KS Lu YH . Age-related macular degeneration in chronic kidney disease: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J Nephrol. (2018) 48:278–91. doi: 10.1159/000493924

15.

Zhu Z Liao H Wang W Scheetz J Zhang J He M . Visual impairment and major eye diseases in chronic kidney disease: the National Health and nutrition examination survey, 2005-2008. Am J Ophthalmol. (2020) 213:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.01.002

16.

Jung W Park J Jang HR Jeon J Han K Kim B et al . Increased end-stage renal disease risk in age-related macular degeneration: a nationwide cohort study with 10-year follow-up. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:183. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-26964-8

17.

Rim TH Kawasaki R Tham YC Kang SW Ruamviboonsuk P Bikbov MM et al . Prevalence and pattern of geographic atrophy in Asia: the Asian eye epidemiology consortium. Ophthalmology. (2020) 127:1371–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.04.019

18.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann T Mulrow C et al . The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

19.

Deva R Alias MA Colville D Tow FKNFH Ooi QL Chew S et al . Vision-threatening retinal abnormalities in chronic kidney disease stages 3 to 5. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. (2011) 6:1866–71. doi: 10.2215/cjn.10321110

20.

Nitsch D Evans J Roderick PJ Smeeth L Fletcher AE . Associations between chronic kidney disease and age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. (2009) 16:181–6. doi: 10.1080/09286580902863064

21.

Xu L Wang S Li Y Jonas JB . Retinal vascular abnormalities and prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in adult Chinese: the Beijing eye study. Am J Ophthalmol. (2006) 142:688–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.05.028

22.

Yang K Liang YB Gao LQ Peng Y Shen R Duan XR et al . Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in a rural Chinese population: the Handan eye study. Ophthalmology. (2011) 118:1395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.12.030

23.

Nangia V Jonas JB Kulkarni M Matin A . Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in rural Central India: the Central India eye and medical study. Retina. (2011) 31:1179–85. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181f57ff2

24.

Park SJ Lee JH Woo SJ Ahn J Shin JP Song SJ et al . Age-related macular degeneration: prevalence and risk factors from Korean National Health and nutrition examination survey, 2008 through 2011. Ophthalmology. (2014) 121:1756–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.03.022

25.

Bikbov M Fayzrakhmanov RR Kazakbaeva G Jonas JB . Ural eye and medical study: description of study design and methodology. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. (2018) 25:187–98. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2017.1384504

26.

Neelamegam V Surya RJ Venkatakrishnan P Sharma T Raman R . Association of eGFR with stages of diabetic retinopathy and age-related macular degeneration in Indian population. Indian J Ophthalmol. (2024) 72:968–75. doi: 10.4103/IJO.IJO_2558_23

27.

Gao B Zhu L Pan Y Yang S Zhang L Wang H . Ocular fundus pathology and chronic kidney disease in a Chinese population. BMC Nephrol. (2011) 12:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-12-62

28.

Weiner DE Tighiouart H Reynolds R Seddon JM . Kidney function, albuminuria and age-related macular degeneration in NHANES III. Nephrol Dial Transplant. (2011) 26:3159–65. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr022

29.

Chen C-Y Dai C-S Lee C-C Shyu YC Huang TS Yeung L et al . Association between macular degeneration and mild to moderate chronic kidney disease: a nationwide population-based study. Medicine (Baltimore). (2017) 96:6405. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006405

30.

Thomas MC Neuen BL Twigg SM Cooper ME Badve SV . SGLT2 inhibitors for patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD: a narrative review. Endocr Connect. (2023) 12:5. doi: 10.1530/EC-23-0005

31.

Chmielewski M Cohen G Wiecek A Jesús Carrero J . The peptidic middle molecules: is molecular weight doing the trick?Semin Nephrol. (2014) 34:118–34. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2014.02.005

32.

Yaspan BL Williams DF Holz FG Regillo CD Li Z Dressen A et al . Targeting factor D of the alternative complement pathway reduces geographic atrophy progression secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Sci Transl Med. (2017) 9:1443. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf1443

33.

Heier JS Lad EM Holz FG Rosenfeld PJ Guymer RH Boyer D et al . Pegcetacoplan for the treatment of geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration (OAKS and DERBY): two multicentre, randomised, double-masked, sham-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet. (2023) 402:1434–48. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01520-9

34.

Opdebeeck B Maudsley S Azmi A de Maré A de Leger W Meijers B et al . Indoxyl Sulfate and p-cresyl Sulfate promote vascular calcification and associate with glucose intolerance. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2019) 30:751–66. doi: 10.1681/asn.2018060609

35.

Farinacci M Krahn T Dinh W Volk HD Düngen HD Wagner J et al . Circulating endothelial cells as biomarker for cardiovascular diseases. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. (2019) 3:49–58. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12158

36.

Machalińska A Safranow K Dziedziejko V Mozolewska-Piotrowska K Paczkowska E Kłos P et al . Different populations of circulating endothelial cells in patients with age-related macular degeneration: a novel insight into pathogenesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2011) 52:93–100. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5756

37.

Mulangala J Akers EJ Solly EL Bamhare PM Wilsdon LA Wong NKP et al . Pro-calcific environment impairs ischaemia-driven angiogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23:3363. doi: 10.3390/ijms23063363

38.

Zhou L Sun H Chen G Li C Liu D Wang X et al . Indoxyl sulfate induces retinal microvascular injury via COX-2/PGE(2) activation in diabetic retinopathy. J Transl Med. (2024) 22:870. doi: 10.1186/s12967-024-05654-1

39.

Shah SN Knausenberger TB-A Pontifex MG Connell E Le Gall G Hardy TAJ et al . Cerebrovascular damage caused by the gut microbe/host co-metabolite p-cresol sulfate is prevented by blockade of the EGF receptor. Gut Microbes. (2024). 16:2431651. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2024.243165

40.

Robinson K Gupta A Dennis V Arheart K Chaudhary D Green R et al . Hyperhomocysteinemia confers an independent increased risk of atherosclerosis in end-stage renal disease and is closely linked to plasma folate and pyridoxine concentrations. Circulation. (1996) 94:2743–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.94.11.2743

41.

Bostom AG Shemin D Lapane KL Sutherland P Nadeau MR Wilson PWF et al . Hyperhomocysteinemia, hyperfibrinogenemia, and lipoprotein (a) excess in maintenance dialysis patients: a matched case-control study. Atherosclerosis. (1996) 125:91–101. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(96)05865-0

42.

Vingerling JR Dielemans I Bots ML Hofman A Grobbee DE de Jong PT . Age-related macular degeneration is associated with atherosclerosis. The Rotterdam study. Am J Epidemiol. (1995) 142:404–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117648

43.

Wang J Zhang H Ji J Wang L Lv W He Y et al . A histological study of atherosclerotic characteristics in age-related macular degeneration. Heliyon. (2022) 8:e08973. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08973

Summary

Keywords

chronic kidney disease, age-related macular degeneration, macular degeneration, age-related maculopathy, oxidative stress

Citation

Lin T-H, Lin Y-Y, Huang Y-T, Huang Y-C, Tien P-T, Wan L and Lin H-J (2025) Chronic kidney disease increases the risks of age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 12:1635766. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1635766

Received

27 May 2025

Accepted

27 October 2025

Published

27 November 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Hsueh-Te Lee, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taiwan

Reviewed by

Ivan Antonio Garcia-Montalvo, National Institute of Technology of Mexico, Mexico

Nádia Fernandes, Instituto Politécnico de Lisboa, Portugal

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Lin, Lin, Huang, Huang, Tien, Wan and Lin.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Peng-Tai Tien, miketien913@gmail.com; Lei Wan, lei.joseph@gmail.com; Hui-Ju Lin, irisluu2396@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.