Abstract

Objective:

This study aimed to examine the effect of opioid-free anesthesia (OFA) on postoperative outcome indicators and explore its application in thoracoscopic or laparoscopic as well as non-thoracoscopic or laparoscopic surgeries, providing a scientific basis for clinical decision-making.

Method:

A systematic search was conducted for clinical studies comparing OFA and opioid-based anesthesia (OBA) published from the establishment of the databases to May 2025 using databases such as PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and Cochrane Library. The primary outcome was the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV). Secondary outcomes included perioperative recovery indicators, the need for postoperative emergency analgesia, postoperative pain score (VAS, NRS), and adverse reactions.

Results:

A total of 3,766 relevant studies were initially identified, and 68 randomized controlled trials involving 5,426 patients were ultimately included. Compared with OBA, OFA significantly reduced the risks of PONV (RR = 0.50, 95% CI: 0.39–0.64), nausea alone (RR = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.25–0.46), vomiting alone (RR = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.25–0.46), and the need for postoperative emergency analgesia (RR = 0.61, 95% CI: 0.51–0.72). OFA was also associated with lower 24 h postoperative NRS pain scores (SMD = −0.32, 95% CI: −0.53 to −0.10). For outcomes with high heterogeneity (I2 > 75%), the systematic review showed that most studies did not find a significant reduction in postoperative VAS pain scores with OFA. However, over two-thirds of the studies have shown that OFA can improve the quality of postoperative recovery (QoR-40). Approximately half of the studies suggested that OFA may prolong extubation time, while most found no significant difference in PACU stay time.

Conclusion:

In summary, OFA not only significantly reduces postoperative PONV, but also lowers the demand for analgesic drugs and improves the quality of postoperative recovery. However, its effect on some postoperative recovery indicators is limited, and further high-quality studies are required to confirm these findings. OFA is expected to serve as a safe and effective anesthesia strategy to optimize the perioperative outcomes of patients.

1 Introduction

The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) program has gained significant attention (1) and is widely used in perioperative management across various surgical specialties. Opioids, the cornerstone of perioperative analgesia, are associated with adverse effects such as intestinal motility inhibition, sedation, respiratory depression, urinary retention, postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), pruritus, and hyperalgesia (2). Additionally, opioids can exacerbate sleep apnea and increase the risk of critical respiratory events (CREs) during postoperative recovery, posing a serious threat to patient safety (3). Opioid-free anesthesia (OFA) is a multimodal approach that aims to eliminate the use of opioids throughout the perioperative period by integrating various strategies, thereby reducing opioid-related adverse effects while maintaining patient comfort (4). The increasing adoption of OFA reflects a growing response to the risks associated with opioid adverse drug events. However, its application remains highly controversial. Given the inconsistent findings across studies, further investigation is warranted. Currently, there is a lack of unified guidelines for implementing OFA. Clinicians' attitudes toward OFA are characterized by a coexistence of active exploration and cautious implementation, largely due to the absence of high-level evidence. Consequently, the benefits and drawbacks of OFA remain a matter of uncertainty for clinicians. Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have examined the impact of OFA on postoperative recovery, analgesic efficacy, and opioid-related side effects. For example, Minke (5) conducted a systematic review summarizing the effects of OFA on both acute and chronic postoperative pain. However, significant heterogeneity exists in the research on OFA, and the level of evidence is generally medium to low (6). The external validity of OFA in improving postoperative recovery remains to be further confirmed. These studies offer preliminary evidence supporting the clinical application of OFA. Nevertheless, given the continuous emergence of new research, some recent high-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have not been included in previous analyses, and earlier meta-analyses are often limited by small sample sizes and high heterogeneity. While OFA has attracted attention for its potential to reduce opioid-related adverse effects, the conclusions of prior studies have been inconsistent. Therefore, we conducted this meta-analysis. Based on the latest literature, we systematically reviewed all available evidence regarding opioid and OFA and their impacts on postoperative outcomes, aiming to provide more comprehensive, up-to-date, and high-quality evidence for clinical practice.

In this study, we strictly adhered to the PICOS framework to ensure transparency and reproducibility. Specifically, the population (P) included surgical patients undergoing general anesthesia with ASA physical status I to III. The intervention (I) was OFA, defined as complete avoidance of opioid use during the perioperative period. The comparator (C) was conventional opioid-based anesthesia (OBA). The primary outcome (O) was the incidence of PONV, while secondary outcomes included quality of recovery (QoR-40 score), postoperative emergency analgesic requirement, adverse events, length of hospital stay, postoperative pain scores (NRS or VAS), extubation time, and post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) stay duration. The study design (S) consisted of a systematic review and meta-analysis, including RCTs published up to May 2025, following the PRISMA guidelines.

2 Methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the checklist recommended by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) (7).

2.1 Research objects and retrieval strategies

The research subjects were patients receiving general anesthesia. Databases such as PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and Cochrane Library were systematically retrieved to comprehensively collect studies that met the inclusion criteria. The retrieval time ranged from the establishment of the databases to May 2025 to ensure the coverage of the latest research results. The search terms are as follows: non-opioid, opioid-free, general anesthesia, randomized controlled trial.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: (1) Surgical patients receiving general anesthesia, with ASA grades I–III; (2) Compare anesthesia without opioid anesthetic drugs with that containing opioid anesthetic drugs; (3) The research design stipulates the sample size; Exclusion criteria: (1) The research lacks original data or has incomplete materials, making it impossible to extract the data; (2) Secondary studies such as meta-analysis, case reports, reviews, abstracts, and non-original literature studies; (3) Animal experiments, etc. This study ensured the homogeneity of the research subjects and the repeatability of the results through strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, thereby more reliably evaluating the impact of OFA on postoperative outcomes.

2.3 Data extraction

During the data extraction stage, a data extraction table is first created. Then, two researchers screened all the studies according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria and then extracted the relevant data from the studies for statistical analysis. If the two researchers arrive at different results and fail to reach a consensus after discussion, the third researcher will re-extract the data for analysis and obtain the results. Finally, the three researchers cross-reviewed and confirmed the accuracy of all the data. If the data in an article is ambiguous or controversial, contact the original author to obtain the accurate original data. The extracted research characteristics include: first author, publication year, country, number of patients, type of OBA protocol, type of anesthesia protocol in the OFA group, outcome indicators, and study type. The primary outcome measure was the incidence of PONV. If the study divided it into two indicators, nausea and vomiting, they would be studied separately. Secondary outcome measures included postoperative recovery quality (QoR-40 score), the incidence of requiring emergency analgesia, postoperative adverse reactions, perioperative recovery indicators, and pain score. If the pain score and QoR-40 score were reported at multiple time points after the operation, the scores at the time point closest to 24 h after the operation were collected for meta-analysis.

2.4 Quality assessment

To assess the risk bias in the included studies, this study used the risk bias assessment tool RoB 2 (8) (Risk of Bias 2) recommended by Cochrane to conduct a systematic review of all RCTS. Each assessment result is classified as “low risk,” “some concern,” or “high risk.” The assessment work was independently completed by two researchers. If there were any differences, the final judgment would be determined after the participation of a third researcher in the discussion.

2.5 Statistical analysis

A meta-analysis was performed using Stata 18.0 statistical software. Binary categorical variables were expressed as relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI); If the included studies report the mean and standard deviation, the effect size is expressed as the mean difference. For studies involving three study groups, the means of the two study groups between the two OFA or OBA groups were estimated. For studies that use other descriptive methods, such as median and quartile ranges, the standardized mean difference is calculated. All the included studies were divided into two groups according to the surgical methods: the “thoracoscopic or laparoscopic group” and the “non-thoracoscopic or laparoscopic group.” The heterogeneity was evaluated by the Cochran Q test and the I2 value (9). A random-effects model was used for all analyses for two main reasons: (1) the Q test is characterized by low statistical power for between-study heterogeneity, which is especially relevant when few studies are available; (2) the random-effects model is a more conservative choice when heterogeneity is present, whereas it reduces to the fixed-effects model when heterogeneity is absent. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. When substantial heterogeneity is detected (I2 > 75%), a meta-analysis is deemed inappropriate. In such cases, a systematic review with qualitative synthesis is conducted instead (10). For all the analyses, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Subgroup analyses were performed to evaluate the effects of OFA across different surgical types, including thoracoscopic surgery, laparoscopic surgery, and other non-laparoscopic/thoracoscopic procedures. Additional subgroup analyses were conducted based on anesthetic techniques, specifically comparing total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) and combined intravenous-inhalation anesthesia. Furthermore, the impact of regional nerve block (RNB) use was also examined to assess its influence on postoperative outcomes within the OFA group. Then, the sensitivity analysis was conducted using the following two methods: (1) The elimination method was applied step-by-step, with each study, to observe whether the effect size changed; (2) Low-quality literature (“high-risk” or “some concerns”) is excluded, and a meta-analysis is re-conducted to explore the impact of low-quality studies on the overall effect. Publication bias was analyzed by using Begg's funnel plot (11) and Egger's test (12) when the number of studies was >10. If publication bias is detected, the “trim and fill method” should be used to adjust the results (13). Meta-regression analysis was performed to further explore the impact of clinical factors on postoperative outcomes. Variables included surgical type, anesthetic technique, and the use of regional nerve blocks. The analysis used a random-effects model to assess their impact on key outcomes, with results presented as regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals.

3 Results

3.1 Literature search

Through systematic retrieval, a total of 3,766 relevant studies were identified. After removing duplicates, the remaining articles were screened based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria by thoroughly reviewing their titles, abstracts, and full-text contents. Ultimately, 68 studies were included in this analysis. For detailed information on the literature retrieval and study selection process, please refer to the Supplementary Table 1. A total of 5,426 patients participated in these studies, with 2,732 assigned to the experimental group and 2,694 to the control group. The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1, and the literature screening process is illustrated in Figure 1. The specific dosing regimen is detailed in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 1

| First author/year | Country | Population (Surgical type) | Sample size (OFA/OA) | Outcomes | Intraoperative regimen in the opioid–free anesthesia group | Intraoperative regimen in the control group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barakat (27) 2025 | Lebanon | Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy | 40/43 | Opioid consumption during the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU); Intraoperative hemodynamic stability; Time to extubation; PACU stay duration; Opioid consumption during the first 48 h; Anti-emetic requirements | Dexmedetomidine, lidocaine, propofol, rocuronium, ketamine, sevofurane | Propofol, fentanyl, ketamine, rocuronium, remifentanil, sevofurane |

| Zeng (54) 2025 | China | Tonsillectomy | 22/22 | Pain score; The time to first food ingestion, sleep quality, nausea, vomiting; Respiratory depression, insufficient analgesia, number of children requiring hydromorphone rescue analgesia, and differences in psychological symptoms; Postoperative bleeding, and caregiver satisfaction | Sevoflurane, propofol, cisatracurium, esketamine, dexmedetomidine | Sevoflurane, propofol, cisatracurium, fentanyl, remifentanil |

| Bao (1) 2024 | China | Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery | 86/88 | Incidence of PONV; PONV severity; Postoperative pain; Haemodynamic changes during anesthesia; Length of stay (LOS) in the recovery ward and hospital | Dexmedetomidine, dexamethasone, midazolam, propofol, rocuronium, lidocaine, magnesium sulfate, cisatracurium | Dexmedetomidine, dexamethasone, midazolam, propofol, rocuronium, sufentanil, propofol, remifentanil, cisatracurium |

| Chassery (14) 2024 | France | Hip arthroplasty | 40/40 | The opioid consumption: median cumulative OME consumption in the PACU; Pain scores; Walking recovery time; Adverse events | Dexmedetomidine | Sufentanil |

| Copik (55) 2024 | Poland | Video-assisted thoracic surgery | 25/25 | NRS and PHHPS; Total dose of postoperative oxycodone; Opioid related adverse events | Lidocaine, ketamine | Fentanyl |

| Leger (56) 2024 | France | Major surgery | 65/68 | Early postoperative quality of recovery (Quality of Recovery-15); Quality of Recovery-15 at 48 and 72 h; Incidence of chronic pain; Quality of life at 3 months | Clonidine, magnesium sulfate, lidocaine, ketamine | Sufentanil, remifentanil, ketamine |

| Minqiang (57) 2024 | China | Thoracoscopic sympathectomy | 78/73 | Perioperative complications; Vital signs, blood gas indices, visual analog scale (VAS) scores, adverse events, patient satisfaction | Propofol, dezocine, dexmedetomidine, intercostal nerve block | Propofol, fentanyl, cisatracurium, remifentanil |

| Ma (58) 2024 | America | Arthroscopic temporomandibular joint surgery | 30/30 | The highest documented pain score; Perioperative opioid consumption, utilization, dosage, and timing of rescue analgesia; Postoperative nausea and vomiting in the PACU and at home; Pain satisfaction levels, occurrence of opioid-related adverse effects, duration of PACU and hospital stays; Total consumption of oxycodone-acetaminophen tablets | Lidocaine, ketamine, dexmedetomidine, sevoflurane | Fentanyl, sevoflurane |

| Bhardwaj (59) 2024 | India | Breast cancer surgery | 50/50 | Comparison of analgesic efficacy; NRS pain scores; NLR and number of NKCs, T helper cells, cytotoxic T cells; Side effects | Propofol, cisatracurium, dexamethasone, sevofurane, dexmedetomidine, magnesium sulfate | Propofol, cisatracurium, dexamethasone, sevofurane, fentanyl |

| Wang (60) 2024 | China | Thyroid and parathyroid surgery | 197/197 | Postoperative nausea and vomiting; Severity of PONV; Need for rescue anti-emetics; Need for rescue analgesics; Interventions for haemodynamic events; Desaturation after tracheal extubation; dizziness, headache, nightmare or hallucination; Time to tracheal extubation; duration of PACU and postoperative hospital stay; Patient satisfaction, rated using a 5-point Likert scale (ACS NSQIP) | Propofol, esketamine, lidocaine, dexmedetomidine, cisatracurium, | Propofol, sufentanil, lidocaine, cisatracurium |

| Zhou (61) 2024 | China | Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy | 35/36 | Aantiemetic rescue; Pain scores, analgesic needs, extubation time, complications, the hemodynamic changes, and duration of hospital stay | Esketamine, dexmedetomidine, midazolam, propofol, rocuronium, sevoflurane, cisatracurium, TAP | Sufentanil, midazolam, propofol, rocuronium, sevoflurane, cisatracurium |

| Jose (36) 2023 | India | Modified radical mastectomy | 60/60 | Intraoperative hemodynamic variables: Anesthetic requirement, Extubation response, Recovery profile | Propofol, lignocaine, succinylcholine, nitrous oxide in an oxygen mixture (66:33), atracurium, dexmedetomidine | Propofol, lignocaine, succinylcholine, nitrous oxide in an oxygen mixture (66:33), atracurium, morphine, bupivacaine |

| Cha (15) 2023 | China | Hysteroscopy | 45/45 | The quality of recovery 24 h postoperatively (QoR-40 questionnaire); PONV; Time to extubation | Lidocaine, propofol, scoline | Sufentanil, propofol, scoline |

| Chen (62) 2023 | China | Gynecological laparoscopic surgery | 39/38 | Visual Analog Scale (VAS); Intraoperative hemodynamic variables; Awakening and orientation recovery times; Number of postoperative rescue analgesia required; PONV; Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) perioperatively | Esketamine, dexmedetomidine, TAP | Sufentanil, midazolam, propofol, cis-atracurium, TAP |

| Dai (63) 2023 | China | Lower abdominal or pelvic surgery | 62/20 | BP, pulse oxygen saturation, reaction entropy, state entropy, and SPI values; Steward score; Dosage of propofol, dexmedetomidine, rocuronium, and diltiazem; Extubation time; and awake time | Propofol, rocuronium, QLB | Propofol, remifentanil, rocuronium, QLB |

| Elahwal (64) 2023 | Egypt | Scoliosis surgery | 25/25 | Total postoperative morphine consumption at 24 h; Number of patients needed intraoperative magnesium; Time of first postoperative analgesic requirement; Visual analog scale (VAS); Side effects (PONV, hypotension, bradycardia, respiratory depression) | Midazolam, propofol, atracurium, dexmedetomidine, lidocaine, ketamine | Midazolam, propofol, atracurium, fentanyl |

| Krishnasamy Yuvaraj (35) 2023 | India | Breast cancer surgeries | 30/30 | The quality of recovery in the postoperative period (QoR-40 score) | Dexmedetomidine, ketamine, lidocaine, propofol, vecuronium, D-SAPB | Fentanyl, propofol, vecuronium, D-SAPB |

| Liu (65) 2023 | China | Thyroid surgery | 33/33 | Incidence of nausea, Incidence of vomiting, and the visual analog score (VAS) scores; The quality of recovery 40 40-questionnaire (QoR-40) scores | Dexmedetomidine, etomidate, ketamine, lidocaine, propofol, rocuronium | Etomidate, remifentanil, propofol, rocuronium |

| Orhon Ergun (66) 2023 | Turkey | Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery | 37/37 | Postoperative morphine requirement, postoperative pain; Visual analog scale (VAS); Intraoperative vital parameters; Recovery quality using the Quality of Recovery-40 (QoR-40) questionnaire; Opioid-related complications | Propofol, ketamine, rocuronium, dexmedetomidine | Propofol, remifentanil, rocuronium |

| Toleska (16) 2023 | Republic of Macedonia | Colorectal surgery | 20/20 | VAS: the total amount of morphine; the Amount of fentanyl given intravenously; The occurrence of PONV; The total amount of bupivacaine | Dexamethasone, paracetamol, lidocaine, propofol, ketamine, rocuronium bromide, lidocaine, ketamine, magnesium, bupivacaine | Lidocaine, fentanyl, propofol, rocuronium bromide, fentanyl, bupivacaine |

| Yan (67) 2023 | China | Thoracoscopic surgery | 80/79 | Chronic pain rates, Acute pain rates, Postoperative side effects, Perioperative variables | Dexmedetomidine, propofol, rocuronium, esketamine | Propofol, fentanyl, propofol, ocuronium |

| Yu (68) 2023 | China | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 75/75 | The consumption of rescue analgesics; Time to LMA removal, time to orientation recovery; VAS, PONV, GSS; Time to unassisted walking, sleep quality on the night of surgery, time to first flatus, hemodynamics during induction of general anesthesia | Dexmedetomidine, propofol, lidocaine, cisatracurium, ropivacaine | Propofol, remifentanil, cisatracurium, dexmedetomidine, ropivacaine |

| Choi (69) 2022 | Korea | Gynecological laparoscopy | 37/38 | Quality of Recovery-40 (QoR-40) questionnaire; Postoperative pain score; Intraoperative and postoperative adverse events; Stress hormones levels | Dexmedetomidine, lidocaine | Remifentanil |

| An (70) 2022 | China | Laparoscopic radical colectomy | 51/50 | Pain intensity during the operation; Wavelet index, lactic levels, and blood glucose concentration; Visual analog scale (VAS); Rescue analgesic consumption; Side-effects of opioids | Dexmedetomidine, sevofurane, bilateral paravertebral blockade (dexmedetomidine and ropivacaine per side) | Remifentanil, sevofurane, bilateral paravertebral blockade (0.5% ropivacaine per side) |

| Ibrahim (71) 2022 | Saudi Arabia | Sleeve gastrectomy | 51/52 | Quality of recovery assessed by QoR-40; Postoperative opioid consumption; Time to ambulate; Time to tolerate oral fluid; Time to readiness for discharge | Dexmedetomidine, propofol, ketamine, lidocaine, cisatracurium, OSTAP | Propofol, fentanyl, cisatracurium, OSTAP |

| Menck (17) 2022 | Brazil | Laparoscopic gastroplasty | 30/30 | VNS; Morphine consumption; Adverse effects of opioids | Magnesium sulfate, ketamine, lidocaine, dexmedetomidine, propofol, rocuronium | Fentanyl, propofol, rocuronium |

| Saravanaperumal (28) 2022 | India | Oocyte retrieval | 31/31 | Quality of recovery using QOR-15 questionnaire; Bradycardia, post-operative nausea and vomiting, usage of rescue analgesia, and total consumption of propofol | Dexmedetomidine, propofol | Fentanyl, propofol |

| Tochie (72) 2022 | Cameroon | Gynecological surgery | 18/18 | The success rate of OFA, isoflurane consumption, and intraoperative anesthetic complications; Postoperative pain intensity, postoperative complications; Patient satisfaction assessed using the QoR-40 questionnaire, and the financial cost of anesthesia | Magnesium sulfate, lidocaine, ketamine, dexamethasone, propofol, rocuronium, isoflurane, calibrated, ketamine, clonidine | Dexamethasone, diazepam, fentanyl, propofol, rocuronium, isoflurane |

| Toleska (73) 2022 | Republic of Macedonia | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 40/40 | PONV | Dexamethasone, paracetamol, midazolam, lidocaine, propofol, ketamine, rocuronium bromide, magnesium sulfate | Midazolam, fentanyl, propofol, and rocuronium bromide |

| Van Loocke (74) 2022 | Belgium | Laparoscopic bariatric surgery | 20/19 | Blood glucose level; The total dose of opioids given; The postoperative pain using the VAS (visual analog scale) score; Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), duration of surgery, and surgical and/or anesthetic complications | Dexmedetomidine, lidocaine, esketamine, magnesium | Sufentanil |

| Beloeil (75) 2021 | France | Non-cardiac surgery | 157/157 | Severe postoperative opioid-related adverse event; Episodes of postoperative pain; Opioid consumption; Postoperative nausea and vomiting | Dexmedetomidine, propofol, desflurane, lidocaine, ketamine, neuromuscular blockade, dexamethasone | Remifentanil, propofol, desflurane, lidocaine, ketamine, neuromuscular blockade, dexamethasone |

| An (76) 2021 | China | Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery | 49/48 | Intraoperative PTI; WLI reading, MAP, and HR; Arterial partial pressure of oxygen, blood glucose concentration, and lactic acid value; Total consumption of anesthesia medications; Time to passage of flatus; PONV, length of stay, pH, and SpO2 | Dexmedetomidine, sevoflurane, thoracic paravertebral blockade, etomidate, cisatracurium, cisatracurium | Remifentanil, sevoflurane, thoracic paravertebral blockade, etomidate, cisatracurium |

| Taskaldiran (30) 2021 | Turkey | Lumbar herniated disc surgery | 30/30 | Fentanyl consumption and visual analog scale (VAS) score | Propofol, fentanyl, rocuronium, lidocaine, sevoflurane, erector spinae plane block, sugammadex | Propofol, fentanyl, rocuronium, lidocaine, sevoflurane, remifentanil, paracetamol, tramadol, sugammadex |

| Shah (77) 2020 | India | Modified radical mastectomy | 35/35 | VAS-scores; Hemodynamics; Postoperative complication | Dexmedetomidine, propofol, esmolol, atracurium, paracetamol, PECS blocks, ketamine | Fentanyl, propofol, atracurium, paracetamol, morphine, sevoflurane |

| Loung (78) 2020 | Vietnam | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 47/47 | VAS; Side-effects | Lidocaine, magnesium, ketamine, ketorolac, propofol | Fentanyl, propofol |

| Hakim (79) 2019 | Egypt | Ambulatory gynecologic laparoscopy | 40/40 | QOR-40 at 24 h postoperative; Postoperative numerical rating scale (NRS); Time to first rescue analgesia; Number of rescue tramadol analgesia; PONV | Dexmedetomidine, propofol, cisatracurium | Fentanyl, propofol, cisatracurium |

| Toleska (80) 2019 | Republic of Macedonia | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 30/30 | Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scores; Opioid requirements | Dexamethasone, paracetamol, midazolam, lidocaine, propofol, rocuronium bromide, ketamine, magnesium sulfate | Midazolam, fentanyl, propofol, and rocuronium bromide |

| Bhardwaj (59) 2019 | India | Laparoscopic urological procedures | 40/40 | Respiratory depression, mean analgesic consumption, and time to rescue analgesia; Hemodynamic parameters, mean SpO2, respiratory rate, and postanesthesia care unit (PACU) discharge time | Dexmedetomidine, propofol, atracurium, lignocaine, ketamine | Fentanyl, propofol, atracurium |

| Gazi (37) 2018 | Turkey | Hysteroscopies | 15/15 | ANI and VAS; Hemodynamics and complications | Dexmedetomidine, propofol, rocuronium | Remifentanil, propofol, rocuronium |

| Choi (21) 2017 | Korea | Thyroidectomy | 40/40 | PONV; Pain intensity; Sedation score; Extubation time; Hemodynamics | Dexmedetomidine | Remifentanil |

| Mogahed (81) 2017 | Egypt | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 40/40 | Ramsay Sedation Scale (RSS); Visual Analog Scale (VAS); PONV and the need for additional analgesics or antiemetics | Propofol, rocuronium bromide, sevoflurane, dexmedetomidine | Propofol, rocuronium bromide, sevoflurane, remifentanil |

| Subasi (82) 2017 | Turkey | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 20/20 | Spontaneous respiration, extubation, and response to verbal commands; Aldrete score ≥9 times, postoperative pain scores, and vital parameters; Total analgesic consumption, patients' first analgesic needs | Propofol, rocuronium, fentanyl, dexmedetomidine | Propofol, rocuronium, fentanyl, remifentanil |

| Hontoir (83) 2016 | Belgium | Breast cancer surgery | 31/33 | QoR-40 score; Postoperative NRS at different timings; Ramsey sedation scale | Clonidine, ketamine, lidocaine, propofol | Remifentanil, ketamine, lidocaine, propofol |

| Choi (22) 2016 | Korea | Laparoscopic hysterectomy | 30/30 | Pain VAS scores; The modified OAA/S scores, the BIS; Vital signs, and the perioperative side effects | Lidocaine, propofol, rocuronium, N2O, desflurane, dexmedetomidine | Lidocaine, propofol, rocuronium, N2O, desflurane, remifentanil |

| Bakan (84) 2015 | Turkey | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 40/40 | Postoperative fentanyl consumption; Pain intensity scores (NRS); Incidence of PONV; Other adverse events | Dexmedetomidine, lidocaine, propofol, vecuroniumat | Fentanyl, remifentanil, propofol, lidocaine, vecuroniumat |

| Hwang (18) 2015 | South Korea | Spinal surgery | 19/18 | Visual analog scale (VAS) score; PCA dosage administered; Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) | Dexmedetomidine, propofol, rocuronium | Remifentanil, propofol, rocuronium |

| Senol Karataş (23) 2015 | Turkey | Major abdominal surgery | 16/16 | Meperidine consumption, VAS scores, Side effects | Atropine sulfate, midazolam, thiopental sodium, vecuronium, desflurane, paracetamol | Atropine sulfate, midazolam, thiopental sodium, vecuronium, desflurane, paracetamol, remifentanil |

| White (85) 2015 | America | Superficial surgical | 50/50 | Number of coughing episodes; Vital signs; Dosages of all anesthetic drugs; Duration of surgery and anesthesia; VRS scores and side effects | Lidocaine, propofol, desflurane | Fentanyl, lidocaine, propofol, desflurane |

| Sahoo (19) 2015 | India | Laparoscopic gynecological surgeries | 80/80 | pain intensity, analgesic requirements, and postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) | Dexmedetomidine, vercuronium, propofol | Remifentanyl, propofol, vercuronium |

| Mansour (20) 2013 | Egypt | Bariatric surgery | 15/13 | Hemodynamics; Pain monitoring (VAS); Post-operative nausea and vomiting; Patient satisfaction and acute pain nurse satisfaction | Propofol, ketamine, rocuronium, sevoflurane | Propofol, fentanyl, rocuronium, sevoflurane |

| Lee (86) 2013 | Korea | Endoscopic sinus surgery | 32/34 | Surgical conditions, hemodynamic parameters, intraoperative blood loss, time to extubation, sedation, and pain | Propofol, desflurane, dexmedetomidine | Propofol, desflurane, remifentanil |

| Techanivate (87) 2012 | Thailand | Gynecologic laparoscopy | 20/20 | Pain intensity using verbal rating score (VRS); The severity of sedation; The episode of intraoperative and postoperative side effects | Propofol, atracurium, desflurane, dexmedetomidine | Propofol, atracurium, desflurane, nitrous oxide, fentanyl |

| Lee (31) 2012 | Korea | Laparoscopic hysterectomy | 25/28 | Pain score, Total volume of administered patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), and PONV | Glycopyrrolate, midazolam, thiopental sodium, rocuronium, desflurane, nitrous oxide | Glycopyrrolate, midazolam, thiopental sodium, rocuronium, desflurane, nitrous oxide, sufentanil |

| Lee (29) 2011 | Korea | Tonsillectomy | 30/30 | Degree of pain severity, First postoperative requirement, Analgesic dose required | Sevoflurane | Sovoflurane, remifentanil |

| Jung (24) 2011 | Korea | Laparoscopic hysterectomy | 25/25 | Visual analog scale (VAS) scores; Alertness (OAA/S) score; Postoperative side-effects; BIS, VAS scores, modified OAA/S scores of sedation, vital signs, respiratory rates, and end-tidal carbon dioxide levels | Lidocaine, propofol, rocuronium, nitrous oxide, desflurane, dexmedetomidine | Lidocaine, propofol, rocuronium, nitrous oxide, desflurane, remifentanil |

| De (26) 2010 | France | Minor hand surgery | 30/30 | Postoperative pain; Postoperative vomiting; Time to discharge from the recovery room; Time to discharge home | Midazolam, sevoflurane, mix of O2/N2O (33%/66%), by wrist blocks | Alfentanil, propacetamol, niflumic acid |

| Ryu (88) 2009 | Korea | Middle ear surgery | 40/40 | Haemodynamic variables, surgical conditions, postoperative pain, and adverse effects | Propofol, sevoflurane, magnesium sulfate | Propofol, sevoflurane, remifentanil |

| Salman (89) 2009 | Turkey | Gynecologic laparoscopic surgery | 30/30 | Demographic, hemodynamic data, postoperative pain scores, and discharge time; Time to extubation, to orientation to person, to place, and date; Postoperative nausea, vomiting, and analgesic requirements | Propofol, vecuronium bromide, dexmedetomidine | Propofol, vecuronium bromide, remifentanil |

| Collard (90) 2007 | Canada | Cholecystectomy | 30/28 | VRS; PONV; Itching, urinary retention; White-song score | Midazolam, remifentanil or fentanyl, propofol, rocuronium | Midazolam, esmolol, propofol, rocuronium |

| Feld (91) 2006 | America | Bariatric surgery | 10/10 | Patient-evaluated pain scores; Morphine use by patient-controlled analgesia pump | Dexmedetomidine, midazolam, lidocaine, thiopental, succinylcholine | Fentanyl, lidocaine, thiopental, succinylcholine |

| Shirakami (92) 2006 | Japan | Major breast cancer surgery | 26/25 | Postoperative nausea and vomiting and postanesthesia recovery | Propofol, lidocaine, diclofenac sodium, local infiltration anesthesia (0.5% lidocaine, 200 mg × 2; total, 400 mg) | Propofol, lidocaine, diclofenac sodium, local infiltration anesthesia (0.5% lidocaine, 200 mg × 2; total, 400 mg), fentanyl |

| Feld (91) 2005 | America | Bariatric surgery | 10/10 | Patient-evaluated pain scores; Morphine use by patient-controlled analgesia pump | Midazolam, dexmedetomidine, lidocaine, thiopental, succinylcholine | Fentanyl, lidocaine, thiopental, succinylcholine, desflurane |

| Hansen (32) 2005 | Denmark | Major abdominal surgery | 18/21 | Patient-controlled analgesia with morphine for 24 h post-operatively; Morphine consumption; Assessment of pain; Side-effects and levels of sensory block | Triazolam, thoracic epidural anesthesia, thiopental, rocuronium, sevoflurane | Triazolam, thoracic epidural anesthesia, thiopental, rocuronium, sevoflurane, remifentanil |

| Feld (33) 2003 | America | Gastric bypass surgery | 15/15 | Visual analog scale; Morphine use by patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump | Ventilated, sevoflurane, ketorolac, clonidine, lidocaine, ketamine, magnesium sulfate, methylprednisolone | Sevoflurane, fentanyl |

| Curry (25) 1996 | America | Electrocautery tubal ligation | 22/22 | Patient assessments of visual analog scales (VAS); Cumulative opioid requirements. | Propofol, lidocaine, vecuronium, nitrous oxide, isoflurane, neostigmine, glycopyrrolate | Propofol, lidocaine, vecuronium, nitrous oxide, isoflurane, neostigmine, glycopyrrolate, fentanyl |

| Katz (93) 1996 | Canada | Abdominalhysterectomy | 15/15 | Pain and morphine consumption; Plasma levels of aljentanil; Adverse effects | Midazolam, thiopentone, isoflurane, N2O, vecuronium | Midazolam, aIfentanil, N2O, vecuronium |

| Sukhani (94) 1996 | America | Ambulatory gynecologic laparoscopy | 39/38 | Post-analgesic effect; sequelae of vomiting; recovery characteristics (awakening, Walking, and discharge) | Lidocaine, propofol, atracurium, nitrous oxide, ketorolac | Lidocaine, propofol, atracurium, nitrous oxide, fentanyl |

| Tverskoy (34) 1994 | Israel | Lective hysterectomy | 9/9 | VAS | Ketamine, thiopental, isoflurane | Fentanyl, thiopental, isoflurane |

Basic characteristics of the study.

OFA, Opioid-Free Anesthesia; OBA, Opioid-Based Anesthesia; PONV, Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting; LOS, length of stay in hospital; VAS, Visual Analog Scale; NRS, Numeric Rating Scale; QoR-40, Quality of Recovery-40; OSTAP, Oblique Subcostal Transversus Abdominis Plane block; QLB, Quadratus Lumborum Block; TAP, Transversus Abdominis Plane block; D-SAPB, Deep Serratus Anterior Plane Block.

Figure 1

Flowchart of literature screening.

3.2 Risk of bias assessment of the included studies

Overall, 43 trials were classified as having a low risk of bias, 15 trials as having an unclear risk of bias, and 10 trials as having a high risk of bias. Among the 68 trials, randomization procedures were fully described in 55 trials (81%), and the concealment of treatment allocation was described in 52 trials (76%). One study had unclear or high-risk incomplete outcome data. The evaluation of study quality using the RoB 2 tool is provided in Supplementary Table 3. The proportion of each methodological quality item is shown in Figure 2A, and the methodological quality assessment of the included studies is shown in Figure 2B.

Figure 2

(A) The proportion of each methodological quality item. (B) The methodological quality assessment.

3.3 Meta-analysis results

3.3.1 Primary outcome indicator

3.3.1.1 PONV

A total of 23 studies reported on the incidence of postoperative PONV. The results indicated that the risk of PONV was significantly lower in the OFA group compared with the OBA group (RR = 0.50, 95% CI: 0.39–0.64, I2 = 54.7%, Ph = 0.001, Figure 3A). Subgroup analyses revealed significant reductions in PONV risk in both the thoracoscopic/laparoscopic surgery group (RR = 0.64, 95% CI: 0.49–0.85, I2 = 45.7%, Ph = 0.042, Figure 3A) and the non-thoracoscopic/laparoscopic surgery group (RR = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.23–0.51, I2 = 40.1%, Ph = 0.081, Figure 3A). Additional subgroup analyses are presented in Table 2. Sensitivity analysis was initially performed using a stepwise exclusion method, with consistent results (Figure 3B). After excluding low-quality studies (14–20), the combined effect size remained stable (RR = 0.47, 95% CI: 0.33–0.66, I2 = 55.5%, Ph = 0.005, Figure 3C). The funnel plot distribution and the result of Egger's test (P = 0.002) suggested the presence of publication bias. Adjustment using the trim and fill method (Figure 3D) maintained a robust pooled effect (RR = 0.566, 95% CI: 0.442–0.726) without changing the overall direction of the result. The GRADE assessment for PONV is shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

Figure 3

(A) The forest plot of the impact of OFA on PONV. (B) The sensitivity analysis plot of the impact of OFA on PONV. (C) The forest plot of the impact of OFA on PONV after excluding low-quality studies. (D) Trim and fill method for PONV.

Table 2

| Outcome | Grouping method | No. of studies | Results of meta-analysis | The meta-regression analysis results of the total combined analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | I 2 (%) | P h | Coefficient (95% CI) | SE | t | P | |||

| PONV | |||||||||

| Overall | 23 | 0.50 (0.39–0.64) | 54.7 | 0.001 | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Surgical type | Thoracic/laparoscopic surgery | 12 | 0.64 (0.49–0.85) | 45.7 | 0.042 | −0.624 (−1.187−0.061) | 0.269 | −2.32 | 0.032 |

| Non-Thoracic/laparoscopic surgery | 11 | 0.34 (0.23–0.51) | 40.1 | 0.081 | |||||

| Anesthetic technique | TIVA | 14 | 0.53 (0.39–0.72) | 47.9 | 0.023 | 0.079 (−0.501–0.659) | 0.277 | 0.289 | 0.779 |

| Intravenous inhalational anesthesia | 9 | 0.44 (0.27–0.69) | 61.9 | 0.007 | |||||

| Regional nerve block | Yes | 4 | 0.50 (0.27–0.93) | 62.6 | 0.045 | 0.140 (−0.515–0.795) | 0.313 | 0.447 | 0.660 |

| No | 19 | 0.49 (0.36–0.66) | 55.6 | 0.002 | |||||

| Nausea | |||||||||

| Overall | 22 | 0.34 (0.25–0.46) | 27.5 | 0.115 | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Surgical type | Thoracic/laparoscopic surgery | 12 | 0.29 (0.20–0.42) | 0.8 | 0.436 | 0.238 (−0.347–0.823) | 0.278 | 0.85 | 0.404 |

| Non-Thoracic/laparoscopic surgery | 10 | 0.40 (0.24–0.64) | 44.9 | 0.060 | |||||

| Anesthetic technique | TIVA | 14 | 0.66 (0.36–1.21) | 28.7 | 0.199 | 0.809 (0.162–1.455) | 0.308 | 2.63 | 0.017 |

| Intravenous inhalational anesthesia | 8 | 0.28 (0.21–0.37) | 0.0 | 0.755 | |||||

| Regional nerve block | Yes | 2 | 0.21 (0.08–0.53) | 0.0 | 0.525 | −0.444 (−1.554–0.666) | 0.528 | −0.84 | 0.412 |

| No | 20 | 0.36 (0.26–0.49) | 30.2 | 0.100 | |||||

| Vomiting | |||||||||

| Overall | 23 | 0.34 (0.25–0.46) | 0.0 | 0.596 | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Surgical type | Thoracic/laparoscopic surgery | 14 | 0.33 (0.23–0.48) | 8.0 | 0.365 | −0.107 (−0.991–0.776) | 0.422 | −0.25 | 0.802 |

| Non-Thoracic/laparoscopic surgery | 9 | 0.28 (0.13–0.60) | 0.0 | 0.715 | |||||

| Anesthetic technique | TIVA | 13 | 0.19 (0.11–0.30) | 0.0 | 0.999 | 1.073 (0.333–1.814) | 0.354 | 3.03 | 0.007 |

| Intravenous inhalational anesthesia | 10 | 0.50 (0.34–0.74) | 0.0 | 0.574 | |||||

| Regional nerve block | Yes | 3 | 0.42 (0.24–0.76) | 0.0 | 0.441 | −0.212 (−1.026–0.602) | 0.389 | −0.54 | 0.592 |

| No | 20 | 0.31 (0.22–0.45) | 0.0 | 0.563 | |||||

| Postoperative emergency analgesia needs | |||||||||

| Overall | 26 | 0.61 (0.51–0.72) | 48.8 | 0.003 | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Surgical type | Thoracic/laparoscopic surgery | 15 | 0.61 (0.50–0.75) | 43.5 | 0.037 | 0.048 (−0.378–0.473) | 0.205 | 0.23 | 0.819 |

| Non-Thoracic/laparoscopic surgery | 11 | 0.54 (0.38–0.78) | 56.5 | 0.011 | |||||

| Anesthetic technique | TIVA | 16 | 0.57 (0.45–0.73) | 52.5 | 0.007 | 0.143 (−0.249–0.534) | 0.189 | 0.76 | 0.458 |

| Intravenous inhalational anesthesia | 10 | 0.65 (0.51–0.84) | 44.9 | 0.060 | |||||

| Regional nerve block | Yes | 3 | 0.80 (0.60–1.07) | 10.5 | 0.327 | 0.397 (−0.181–0.975) | 0.279 | 1.42 | 0.169 |

| No | 23 | 0.57 (0.47–0.70) | 49.3 | 0.004 | |||||

| LOS | |||||||||

| Overall | 9 | −0.06 (−0.18–0.06) | 26.5 | 0.208 | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Surgical type | Thoracic/laparoscopic surgery | 5 | 0.04 (−0.15–0.22) | 36.5 | 0.178 | −0.278 (−0.668–0.112) | 0.152 | −1.83 | 0.127 |

| Non-Thoracic/laparoscopic surgery | 4 | −0.12 (−0.28–0.02) | 0.0 | 0.413 | |||||

| Anesthetic technique | TIVA | 4 | −0.09 (−0.26–0.09) | 51.8 | 0.101 | −0.157 (−0.639–0.325) | 0.188 | −0.84 | 0.441 |

| Intravenous inhalational anesthesia | 5 | −0.04 (−0.19–0.12) | 10.7 | 0.345 | |||||

| Regional nerve block | Yes | 5 | −0.02 (−0.16–0.13) | 0.0 | 0.424 | 0.345 (−0.189–0.879) | 0.208 | 1.66 | 0.158 |

| No | 4 | −0.14 (−0.34–0.06) | 50.3 | 0.110 | |||||

| Postoperative respiratory dysfunction | |||||||||

| Overall | 9 | 0.29 (0.09–0.91) | 68.5 | 0.001 | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Surgical type | Thoracic/laparoscopic surgery | 7 | 0.47 (0.15–1.46) | 50.8 | 0.058 | 1.215 (−2.310–4.739) | 1.371 | 0.89 | 0.416 |

| Non-Thoracic/laparoscopic surgery | 2 | 0.10 (0.02–0.57) | 30.5 | 0.230 | |||||

| Anesthetic technique | TIVA | 7 | 0.21 (0.07–0.61) | 26.5 | 0.227 | 0.434 (−3.420–4.288) | 1.499 | 0.29 | 0.784 |

| Intravenous inhalational anesthesia | 2 | 0.69 (0.11–4.12) | 50.1 | 0.157 | |||||

| Regional nerve block | Yes | 2 | 0.69 (0.12–4.12) | 49.4 | 0.160 | 0.455 (−3.410–4.300) | 1.499 | 0.30 | 0.779 |

| No | 7 | 0.21 (0.07–0.61) | 26.5 | 0.227 | |||||

| Bradycardia | |||||||||

| Overall | 14 | 1.04 (0.63–1.70) | 42.1 | 0.048 | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Surgical type | Thoracic/laparoscopic surgery | 7 | 1.10 (0.62–1.96) | 52.3 | 0.050 | −0.121 (−1.696–1.454) | 0.707 | −0.17 | 0.867 |

| Non-Thoracic/laparoscopic surgery | 7 | 0.87 (0.30–2.53) | 38.2 | 0.137 | |||||

| Anesthetic technique | TIVA | 9 | 0.91 (0.49–1.69) | 42.6 | 0.083 | 0.127 (−1.403–1.658) | 0.687 | 0.19 | 0.857 |

| Intravenous inhalational anesthesia | 5 | 1.39 (0.59–3.25) | 20.4 | 0.285 | |||||

| Regional nerve block | Yes | 3 | 1.55 (0.72–3.31) | 65.8 | 0.054 | 0.820 (−0.799–2.440) | 0.727 | 1.13 | 0.285 |

| No | 11 | 0.77 (0.39–1.53) | 33.2 | 0.133 | |||||

| Postoperative intestinal dysfunction | |||||||||

| Overall | 5 | 0.25 (0.14–0.46) | 0.0 | 0.624 | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Anesthetic technique | TIVA | 3 | 0.27 (0.14–0.54) | 0.0 | 0.826 | −0.577 (−4.890–3.736) | 1.002 | −0.58 | 0.623 |

| Intravenous inhalational anesthesia | 2 | 0.18 (0.03–1.03) | 50.5 | 0.155 | |||||

| Regional nerve block | Yes | 1 | 0.24 (0.10–0.56) | NR | NR | −0.341 (−4.480–3.798) | 0.962 | −0.35 | 0.757 |

| No | 4 | 0.26 (0.11–0.61) | 0.0 | 0.460 | |||||

Subgroup meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis of OFA outcomes by surgical type, anesthetic technique, and use of regional nerve block.

RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval; I2, heterogeneity statistic; Ph, p-value for heterogeneity test; Coefficient (95% CI), the regression coefficient and its 95% confidence interval; SE, Standard error; t, t-test value; p, p-value, with values < 0.05 indicating statistical significance; NR, not reported.

Data are grouped by: anesthesia technique (TIVA, intravenous inhalational anesthesia) and regional nerve block status (yes/no).

PONV, Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting; LOS, Length of Stay.

Since all cases of Postoperative intestinal dysfunction were non-thoracoscopic and non-laparoscopic surgeries, subgroup analysis by surgical approach was not conducted. The coefficients in this table were derived by incorporating all three factors (Surgical Type, Anesthetic Technique, and Regional Nerve Block) simultaneously into the meta-regression model, rather than analyzing each factor individually. This approach reflects the impact on the incidence of PONV when considering these factors collectively.

Bold values in the table indicate p-values < 0.05, which are statistically significant.

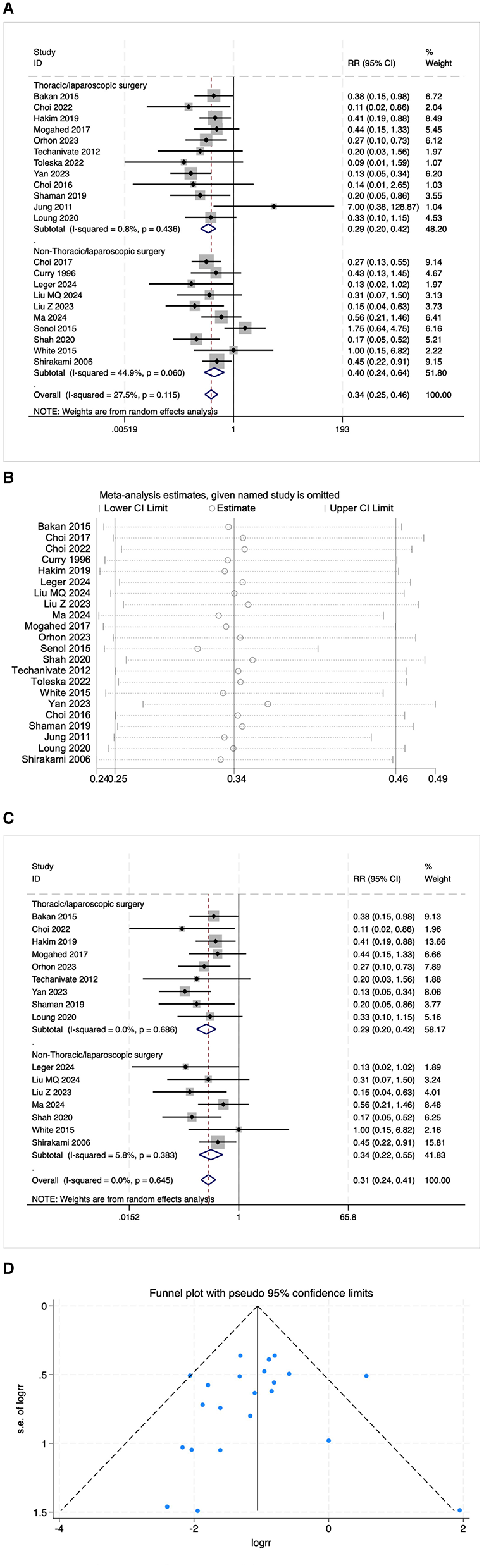

3.3.1.2 Nausea and vomiting

Some studies reported PONV as postoperative nausea and postoperative vomiting, respectively. This review included 22 studies on postoperative nausea and 23 studies on postoperative vomiting. The results indicated that the risk of postoperative nausea in the OFA group was lower than that in the OBA group (RR = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.25–0.46, I2 = 27.5%, Ph = 0.115, Figure 4A). The results of subgroup analysis showed that both the thoracoscopic/laparoscopic surgery group (RR = 0.29, 95% CI: 0.20–0.42, I2 = 0.8%, Ph = 0.436, Figure 4A) and the non-thoracoscopic/laparoscopic surgery group (RR = 0.40, 95% CI: 0.24–0.64, I2 = 44.9%, Ph = 0.060, Figure 4A) demonstrated a significant risk reduction. Additional subgroup analyses are detailed in Table 2. The elimination method was applied step-by-step, and the results were consistent (Figure 4B). After excluding low-quality studies (16, 21–25), the combined effect size remained stable (RR = 0.31, 95% CI: 0.24–0.41, I2 = 0.00%, Ph = 0.645, Figure 4C). The distribution of the funnel plot (Figure 4D) and the result of Egger's test (P = 0.543) also showed no significant publication bias.

Figure 4

(A) The forest plot of the impact of OFA on nausea. (B) The sensitivity analysis plot of the impact of OFA on nausea. (C) The forest plot of the impact of OFA on nausea after excluding low-quality studies. (D) The funnel plot of the impact of OFA on nausea.

The risk of postoperative vomiting in the OFA group was also lower than that in the OBA group (RR = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.25–0.46, I2 = 0.0%, Ph = 0.596, Figure 5A). The results of subgroup analysis showed that both the thoracoscopic/laparoscopic surgery group (RR = 0.33, 95% CI: 0.23–0.48, I2 = 8.0%, Ph = 0.365, Figure 5A) and the non-thoracoscopic/laparoscopic surgery group (RR = 0.28, 95% CI: 0.13–0.60, I2 = 0.00%, Ph = 0.715, Figure 5A) demonstrated a significant risk reduction. Additional subgroup analyses are detailed in Table 2. The elimination method was applied step-by-step, and the results were consistent (Figure 5B). After excluding low-quality studies (16, 21–26), the combined effect size remained stable (RR = 0.35, 95% CI: 0.25–0.48, I2 = 0.0%, Ph = 0.474, Figure 5C). The result of Egger's test (P = 0.156) indicated the presence of publication bias, but the distribution of the funnel plot appears asymmetrical when using the trim and fill method for adjustment (Figure 5D). The pooled effect remained robust (RR = 0.39, 95% CI: 0.27–0.55) without changing the direction of the result. The GRADE assessment for nausea and vomiting is shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

Figure 5

(A) The forest plot of the impact of OFA on vomiting. (B) The sensitivity analysis plot of the impact of OFA on vomiting. (C) The forest plot of the impact of OFA on vomiting after excluding low-quality studies. (D) Trim and fill method for vomiting.

3.3.2 Secondary outcome indicators

The perioperative recovery quality indicators in this study include: postoperative analgesic demand (whether emergency analgesia is needed); length of stay in hospital (LOS); postoperative adverse reactions; pain scores; postoperative quality of recovery (QoR-40) score; extubation time; duration of stay in PACU.

3.3.2.1 Postoperative emergency analgesia needs

Twenty-six RCTS reported the need for postoperative emergency analgesia. The results indicated that the number of patients in the OFA group requiring emergency analgesia after surgery was significantly lower than that in the OBA group (RR = 0.61, 95% CI: 0.51–0.72, I2 = 48.8%, Ph = 0.003, Figure 6A). The results of subgroup analysis indicated that both the thoracoscopic/laparoscopic surgery group (RR = 0.61, 95% CI: 0.50–0.75, I2 = 43.5%, Ph = 0.037, Figure 6A) and the non-thoracoscopic/laparoscopic surgery group (RR = 0.54, 95% CI: 0.38–0.78, I2 = 56.5%, Ph = 0.011, Figure 6A) demonstrated a significant risk reduction. Additional subgroup analyses are detailed in Table 2. The elimination method was applied step-by-step, and the results were consistent (Figure 6B). After excluding low-quality studies (17, 18, 21, 27, 28), the combined effect size remained stable (RR = 0.57, 95% CI: 0.46–0.71, Figure 6C). The distribution of the funnel plot and the result of Egger's test (P = 0.005) indicated the presence of publication bias. The combined result of the trim and fill method (Figure 6D) was RR = 0.484 (95% CI: 0.330–0.710), without reversal. The GRADE assessment for postoperative emergency analgesia needs is presented in Supplementary Figure 1.

Figure 6

(A) The forest plot of the impact of OFA on postoperative emergency analgesia needs. (B) The sensitivity analysis plot of the impact of OFA on postoperative emergency analgesia needs. (C) The forest plot of the impact of OFA on postoperative emergency analgesia needs after excluding low-quality studies. (D) Trim and fill method for postoperative emergency analgesia needs.

3.3.2.2 LOS

The LOS was evaluated in nine trials. There was no significant difference in the length of hospital stay between the OFA group and the OBA group (SMD = −0.06, 95% CI: −0.18–0.06, I2 = 26.5%, Ph = 0.208, Figure 7). Further subgroup analysis was conducted in the thoracoscopic/laparoscopic surgery group (SMD = 0.04, 95% CI: −0.15–0.22, I2 = 36.5%, Ph = 0.178, Figure 7) and the non-thoracoscopic/laparoscopic surgery group (SMD = −0.12, 95% CI: −0.28–0.03, I2 = 0.00%, Ph = 0.413, Figure 7), both of which showed stability. Additional subgroup analyses are detailed in Table 2. The GRADE assessment for LOS is shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

Figure 7

The forest plot of the impact of OFA on LOS.

3.3.2.3 Postoperative adverse reactions

Nine studies reported the incidence of postoperative respiratory dysfunction. The results indicated that the incidence in the OFA group was lower than that in the OBA group (RR = 0.29, 95% CI: 0.09–0.91, I2 = 68.5%, Ph = 0.001, Figure 8A). Five studies reported postoperative intestinal dysfunction. The results indicated that the incidence of postoperative intestinal dysfunction in the OFA group was lower than that in the OBA group (RR = 0.25, 95% CI: 0.14–0.46, I2 = 0.00%, Ph = 0.624, Figure 8B). Fourteen studies reported bradycardia. The results indicated that there was no significant difference in the incidence of bradycardia during the operation between the OFA group and the OBA group (RR = 1.04, 95% CI: 0.63–1.70, I2 = 42.1%, Ph = 0.048, Figure 8C), after excluding low-quality studies (14, 22, 24, 29) and the combined effect size remained stable (RR = 1.01, 95% CI: 0.54–1.87, I2 = 52.4%, Ph = 0.026, Figure 8D). Additional subgroup analyses are detailed in Table 2. The GRADE assessment for postoperative adverse reactions is depicted in Supplementary Figure 1.

Figure 8

(A) The forest plot of the impact of OFA on postoperative respiratory dysfunction. (B) The forest plot of the impact of OFA on postoperative intestinal dysfunction. (C) The forest plot of the impact of OFA on bradycardia. (D) The forest plot of the impact of OFA on bradycardia after excluding low-quality studies.

3.3.2.4 NRS scores

The pain score was calculated using NRS or VAS at 24 h after the operation. Five studies statistically analyzed the NRS scores 24 h after the operation. The results showed that the NRS pain score in the OFA group was lower than that in the OBA group (SMD = −0.32, 95% CI: −0.53 to −0.10, I2 = 0.00%, Ph = 0.870, Figure 9). The GRADE assessment for NRS is shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

Figure 9

The forest plot of the impact of OFA on NRS.

3.4 Meta-regression analysis

Meta-regression was performed to evaluate the influence of surgical type, anesthetic technique, and the use of nerve block on postoperative outcomes and to identify potential sources of heterogeneity. The analysis revealed that both surgical type and anesthetic technique significantly affected certain postoperative outcomes. Specifically, thoracic/laparoscopic surgery (compared with non-thoracic/laparoscopic surgery) was associated with a higher risk of PONV (coefficient = −0.624, P = 0.032, Table 2). However, surgical type did not significantly influence the need for postoperative emergency analgesia, LOS, or postoperative respiratory dysfunction, suggesting that heterogeneity in these outcomes may not be primarily attributable to surgical type.

Additionally, the use of intravenous inhalational anesthesia (compared with TIVA) was associated with a higher risk of nausea (coefficient = 0.809, P = 0.017, Table 2) and vomiting (coefficient = 1.073, P = 0.007, Table 2). In contrast, anesthetic technique did not significantly impact the need for postoperative emergency analgesia, LOS, or postoperative respiratory dysfunction, suggesting that other factors may be more influential in these cases. The use of nerve block did not show significant associations with any of the examined outcomes. Overall, these results emphasize the importance of considering surgical type and anesthetic technique when evaluating postoperative outcomes, as they may significantly influence specific adverse events such as PONV, nausea, and vomiting.

3.5 Results of systematic review

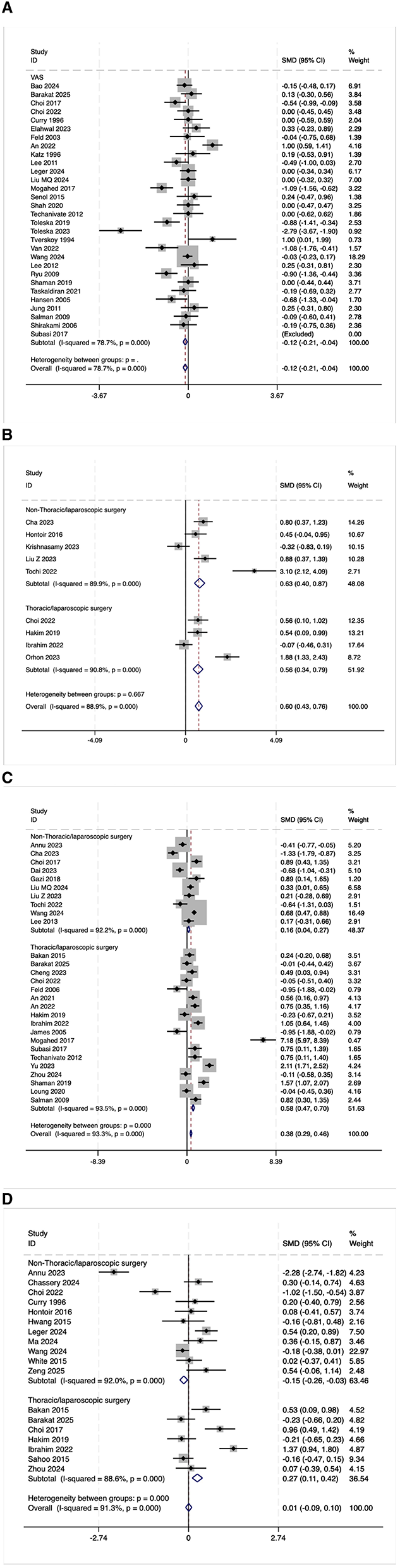

3.5.1 VAS scores

The VAS scores 24 h after the operation were statistically analyzed in 30 trials. However, due to the high heterogeneity observed (I2 = 78.7%, Figure 10A), a meta-analysis was not conducted. Among these 30 studies, eight (27%) reported lower VAS scores in the OFA group, two (7%) reported higher scores, and 20 (66%) reported no significant difference between the groups. After excluding 12 low-quality studies (16, 21, 23–25, 27, 29–34), 18 high-quality studies were re-evaluated. In this subset, four (22%) reported lower VAS scores in the OFA group, one (6%) reported higher scores, and 13 (72%) reported no significant difference between the two groups. These findings suggest that although a subset of studies indicated a potential benefit of OFA in reducing postoperative pain, the majority of studies did not demonstrate a significant difference in VAS scores between the OFA and OBA groups.

Figure 10

(A) The forest plot of the impact of OFA on VAS. (B) The forest plot of the impact of OFA on QOR-40. (C) The forest plot of the impact of OFA on postoperative extubation time. (D) The forest plot of the impact of OFA on postoperative PACU stay time.

3.5.2 QoR-40

Nine randomized trials reported the overall score of QoR-40. Due to the high heterogeneity observed (I2 = 88.9%, Figure 10B), a meta-analysis was not conducted. Among the nine studies, seven (78%) reported higher QoR-40 scores in the OFA group, one (11%) reported lower scores, and one (11%) found no significant difference between the groups. After excluding two low-quality studies (15, 35), seven high-quality studies were re-evaluated. In this subset, six (86%) reported higher QoR-40 scores in the OFA group, zero (6%) reported lower scores, and one (14%) reported no significant difference between the two groups. These findings indicate that OFA may have certain advantages in terms of postoperative satisfaction.

3.5.3 Postoperative extubation time

The postoperative extubation time was evaluated in 28 trials. Due to high heterogeneity (I2 = 93.3%, Figure 10C), a meta-analysis was not conducted. Among the 28 studies, five (18%) reported a shorter extubation time in the OFA group, 14 (50%) reported a longer time, and nine (32%) reported no significant difference between the two groups. After excluding five low-quality studies (15, 21, 27, 36, 37), 23 high-quality studies were re-evaluated. In this subset, three (13%) reported a shorter extubation time in the OFA group, 12 (52%) reported a longer time, and eight (35%) reported no significant difference between the two groups. Overall, half of the studies suggest that OFA may prolong the extubation time, and OFA was possibly associated with a longer extubation time.

3.5.4 Postoperative PACU stay time

The postoperative PACU stay time was evaluated in 18 trials. Due to the high heterogeneity observed (I2 = 91.3%, Figure 10D), a meta-analysis was not conducted. Among the 18 studies, two (11%) reported a shorter PACU stay time in the OFA group, four (22%) reported a longer time, and 12 (67%) reported no significant difference between the two groups. After excluding seven low-quality studies (14, 18, 19, 21, 25, 27, 36), 11 high-quality studies were re-evaluated. In this subset, one (9%) reported a shorter PACU stay time in the OFA group, three (27%) reported a longer time, and seven (64%) reported no significant difference between the two groups. Most studies did not find a statistically significant difference in PACU stay time, and current evidence does not support a definitive advantage of either approach in this outcome.

4 Discussion

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) emphasizes reducing opioid use during hospitalization and minimizing opioid prescriptions after discharge to mitigate the side effects associated with their use (38). PONV is a common complication and is ranked among the five most undesirable surgical outcomes by patients. PONV not only compromises patient comfort but can also lead to serious complications such as dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, wound dehiscence, and aspiration, thereby increasing the medical burden. This meta-analysis demonstrates that compared with OBA, OFA significantly reduces the incidence of postoperative PONV and the need for rescue analgesia while improving QoR-40 scores. In the present study, we comprehensively assessed postoperative recovery quality using the QoR-40 score. The results showed a potential advantage of the OFA group in terms of postoperative satisfaction and overall recovery quality. Despite some heterogeneity, the majority of high-quality studies (86%) reported higher QoR-40 scores in the OFA group, indicating that patients experienced better comfort and functional status during the early postoperative recovery period. This finding underscores the potential of OFA to enhance patient-centered outcomes. Although there were no significant differences in length of hospital stay, VAS score, PACU stay duration, or intraoperative bradycardia, OFA might prolong extubation time; it exhibited potential benefits in reducing postoperative respiratory and intestinal dysfunction.

Previous studies have reported findings consistent with ours. For example, Zhang (39) demonstrated a significant reduction in postoperative PONV risk with OFA, supporting our results with a larger sample size and increased representativeness. Additionally, Zhang (40) found that OFA improved QoR-40 scores, which is consistent with and complemented by the more extensive data in our study. Alexander (41) reported that OFA significantly decreased intraoperative and postoperative adverse events, further strengthening the potential value of OFA in preventing and controlling postoperative adverse reactions. Meanwhile, Minke (5) combined VAS and NRS pain scores to reveal lower pain levels with OFA. Although these two scales are correlated, they have measured different aspects and thus cannot be used interchangeably. Finally, Cheng (42) found no significant difference in PACU stay time between OFA and OBA groups after laparoscopic surgery, which aligns with our findings.

Surgical factors that increase the risk of PONV primarily include surgical stimuli such as artificial pneumoperitoneum and traction reactions, as well as the use of anesthetic drugs (43, 44). Opioid drugs directly act on the μ-opioid receptors in the chemoreceptor trigger zone, thereby activating the vomiting reflex center and inducing vomiting (45). Studies have shown that the use of drugs such as dexmedetomidine and lidocaine during surgery, as well as the implementation of multimodal analgesic strategies, can effectively reduce the incidence of PONV (46). In laparoscopic surgery, the initial establishment of pneumoperitoneum can lead to rapid abdominal expansion, which in turn causes traction on mechanical receptors and increased synthesis of serotonin (5-HT), contributing to PONV (47). A retrospective analysis reported that laparoscopic surgery and prolonged operative time are independent predictors of high-risk PONV (48). Previous meta-analyses have predominantly focused on thoracoscopic (49) or laparoscopic (42) surgeries to evaluate the safety and efficacy of OFA, demonstrating that OFA may provide more significant analgesic and anti-PONV advantages in these minimally invasive procedures. This suggests that the type of surgery may be an important factor influencing the effectiveness of OFA. Both thoracoscopic and laparoscopic surgeries are minimally invasive endoscopic procedures. Minimally invasive endoscopic surgeries are characterized by less trauma, reduced intraoperative blood loss, shorter hospital stays, fewer severe postoperative complications, and faster recovery. These characteristics may influence postoperative recovery indicators under OFA, such as PONV, analgesic demand, and QoR-40 scores. Studies have shown that an operation time exceeding 1 h significantly increases the incidence of PONV (50). The average operation time for laparoscopic surgery is ~40 min longer than that for open surgery (51). For video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS), it is usually about 65.56 min longer than that for open surgery (52). Given that longer operation times are associated with higher PONV risk, treating these surgeries as a separate subgroup helps clarify whether OFA still holds an advantage in this context. Therefore, all studies were divided into two groups: the “thoracoscopic or laparoscopic group” and the “non-thoracoscopic or laparoscopic group” for analysis, to evaluate the effect of OFA accurately. Compared with previous meta-analyses, this study included a larger number of studies and, for the first time, conducted subgroup analyses based on whether the surgery was thoracoscopic or laparoscopic, providing preliminary evidence for the applicability of OFA in different surgical procedures. It should be noted that the current OFA protocol has not been standardized. Differences in the selection of anesthetic drugs (such as dexmedetomidine, lidocaine, etc.), dosage, and administration methods across studies may lead to significant fluctuations in outcome indicators, such as analgesic effect, risk of nausea and vomiting, and extubation time. Future research needs to develop a standardized plan for the use of anesthetic drugs to facilitate better implementation and promotion. The significant heterogeneity observed in some outcomes may not only be related to differences in study design and anesthesia regimens but also to the characteristics of the included patients and the complexity of the surgeries. In this study, subgroup and meta-regression analyses were conducted to explore the sources of heterogeneity in the effects of OFA vs. OBA on various postoperative outcomes. The results indicated that surgical type and anesthetic technique significantly influenced specific outcomes such as PONV and nausea. Specifically, thoracic and laparoscopic surgeries were associated with a higher risk of PONV, while intravenous inhalational anesthesia increased the risk of nausea and vomiting compared to TIVA. The use of nerve blocks did not show significant associations with any of the examined outcomes. These findings underscore the importance of considering surgical type and anesthetic technique when interpreting pooled results. They suggest that optimizing anesthesia and surgical management strategies could improve specific postoperative outcomes. Future research should focus on identifying additional factors contributing to the heterogeneity of other outcomes and on exploring interventions that can further enhance postoperative recovery. Furthermore, female patients are at a higher risk of developing PONV compared to male patients (53). Moreover, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is often more complex than cholecystectomy. These differences in surgical complexity, combined with varying intraoperative and postoperative management strategies, can influence indicators such as analgesic needs, extubation time, and the speed of postoperative recovery, thereby leading to differences in postoperative outcome measures. Previous studies have directly pooled data for outcome indicators with high heterogeneity (I2 > 75%), which may compromise the reliability of the conclusions. In contrast, this study adopted a systematic review approach for such indicators, thereby avoiding the interference of heterogeneity on the combined results. This methodological approach not only enhances the scientific rigor of the conclusions but also strengthens the explanatory power and credibility of the research findings.

This study has several limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, the majority of current studies focus on short-term outcomes within 24 h post-surgery, leaving a gap in evidence regarding the long-term effects of OFA on outcomes such as quality of life and chronic pain. Second, although we analyzed the overall score of the QoR-40 scale, we did not conduct subgroup analyses of its five dimensions. This limitation restricts a more granular understanding of patient recovery quality. Third, despite being one of the most comprehensive meta-analyses on OFA to date, our search strategies may have missed some relevant studies. Finally, we did not conduct stratified analysis based on specific OFA and OBA protocols, which might have masked some clinically significant differences during the combined analysis. These indicators are crucial for assessing postoperative recovery and directly reflect patients' experiences and feelings.

In conclusion, OFA, as an anesthetic strategy for reducing opioid use, has demonstrated significant advantages in terms of postoperative comfort and recovery quality. Future studies should incorporate multi-dimensional subgroup analyses with larger sample sizes to enhance the persuasiveness and clinical relevance of the research conclusions. With the implementation of more high-quality research and the accumulation of practical experience, OFA is expected to be more widely applied in clinical anesthesia practice.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

JQ: Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization, Software, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Project administration. JZ: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JB: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Software. XM: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Software, Formal analysis. XH: Software, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1639968/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

OFA, Opioid-Free Anesthesia; OBA, Opioid-Based Anesthesia; PONV, Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting; LOS, length of stay in hospital; VAS, Visual Analog Scale; NRS, Numeric Rating Scale; ERAS, Enhanced Recovery After Surgery; RCT, Randomized Controlled Trial; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; QoR-40, Quality of Recovery-40.

References

1.

Bao R Zhang WS Zha YF Zhao ZZ Huang J Li JL et al . Effects of opioid-free anaesthesia compared with balanced general anaesthesia on nausea and vomiting after video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: a single-centre randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. (2024) 14:e079544. 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-079544

2.

Nair AS Seelam S Naik V Rayani BK . Opioid-free mastectomy in combination with ultrasound-guided erector spinae block: a series of five cases. Indian J Anaesth. (2018) 62:632–4. 10.4103/ija.IJA_314_18

3.

Lam KK Kunder S Wong J Doufas AG Chung F . Obstructive sleep apnea, pain, and opioids: is the riddle solved?Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. (2016) 29:134–40. 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000265

4.

Beloeil H Laviolle B Menard C Paugam-Burtz C Garot M Asehnoune K et al . SFAR research network. POFA trial study protocol: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, controlled clinical trial comparing opioid-free versus opioid anaesthesia on postoperative opioid-related adverse events after major or intermediate non-cardiac surgery. BMJ Open. (2018) 8:e020873. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020873

5.

Feenstra ML Jansen S Eshuis WJ van Berge Henegouwen MI Hollmann MW Hermanides J . Opioid-free anesthesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth. (2023) 90:111215. 10.1016/j.jclinane.2023.111215

6.

Liu Y Ma W Zuo Y Li Q . Opioid-free anaesthesia and postoperative quality of recovery: a systematic review and meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. (2025) 44:101453. 10.1016/j.accpm.2024.101453

7.

Liberati A Altman DG Tetzlaff J Mulrow C Gøtzsche PC Ioannidis JP et al . The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. (2009) 6:e1000100. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

8.

Sterne JAC Savović J Page MJ Elbers RG Blencowe NS Boutron I et al . RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. (2019) 366:l4898. 10.1136/bmj.l4898

9.

DerSimonian R Laird N . Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. (1986) 7:177–88. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2

10.

Byambasuren O Stehlik P Clark J Alcorn K Glasziou P . Effect of COVID-19 vaccination on long COVID: systematic review. BMJ Med. (2023) 2:e000385. 10.1136/bmjmed-2022-000385

11.

Begg CB Mazumdar M . Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. (1994) 50:1088–101. 10.2307/2533446

12.

Egger M Smith DG Schneider M Minder C . Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br Med J. (1997) 315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

13.

Duval S Tweedie Trim R . and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. (2000) 56:455–63. 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x

14.

Chassery C Atthar V Marty P Vuillaume C Casalprim J Basset B et al . Opioid-free versus opioid-sparing anaesthesia in ambulatory total hip arthroplasty: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Anaesth. (2024) 132:352–8. 10.1016/j.bja.2023.10.031

15.

Cha NH Hu Y Zhu GH Long X Jiang JJ Gong Y . Opioid-free anesthesia with lidocaine for improved postoperative recovery in hysteroscopy: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. (2023) 23:192. 10.1186/s12871-023-02152-7

16.

Toleska M Dimitrovski A Dimitrovska NT . Comparation among opioid-based, low opioid and opioid free anesthesia in colorectal oncologic surgery. Pril. (2023) 44:117–26. 10.2478/prilozi-2023-0013

17.

Menck JT Tenório SB de Oliveira MR Strobel R dos Santos BB Junior AF et al . Opioid-free anesthesia for laparoscopic gastroplasty. A prospective and randomized trial. Open Anesth J. (2022) 16:e258964582208110. 10.2174/25896458-v16-e2208110

18.

Hwang W Lee J Park J Joo J . Dexmedetomidine versus remifentanil in postoperative pain control after spinal surgery: a randomized controlled study. BMC Anesthesiol. (2015) 15:21. 10.1186/s12871-015-0004-1

19.

Sahoo J Sujata P Sahu MC . Comparative study betweeen dexmedetomidine and remifentanyl for efficient pain and ponv management in propofol based total intravenous anesthesia after laparoscopic gynaecological surgeries. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. (2016) 36:212–6. Available online at: https://globalresearchonline.net/journalcontents/v36-1/38.pdf

20.

Mansour MA Mahmoud AA Geddawy M . Nonopioid versus opioid based general anesthesia technique for bariatric surgery: a randomized double-blind study. Saudi J Anaesth. (2013) 7:387–91. 10.4103/1658-354X.121045

21.

Choi EK Seo Y Lim DG Park S . Postoperative nausea and vomiting after thyroidectomy: a comparison between dexmedetomidine and remifentanil as part of balanced anesthesia. Korean J Anesthesiol. (2017) 70:299–304. 10.4097/kjae.2017.70.3.299

22.

Choi JW Joo JD Kim DW In JH Kwon SY Seo K et al . Comparison of an intraoperative infusion of dexmedetomidine, fentanyl, and remifentanil on perioperative hemodynamics, sedation quality, and postoperative pain control. J Korean Med Sci. (2016) 31:1485–90. 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.9.1485

23.

Senol Karataş S Eti Z Saraçoglu KT Gögüş FY . Does perioperative opioid infusion increase postoperative opioid requirement?Agri. (2015) 27:47–53. 10.5505/agri.2015.71676

24.

Jung HS Joo JD Jeon YS Lee JA Kim DW In JH et al . Comparison of an intraoperative infusion of dexmedetomidine or remifentanil on perioperative haemodynamics, hypnosis and sedation, and postoperative pain control. J Int Med Res. (2011) 39:1890–9. 10.1177/147323001103900533

25.

Curry CS Darby JR Janssen BR . Evaluation of pain following electrocautery tubal ligation and effect of intraoperative fentanyl. J Clin Anesth. (1996) 8:216–9. 10.1016/0952-8180(95)00233-2

26.

De Windt AC Asehnoune K Roquilly A Guillaud C Le Roux C Pinaud M et al . An opioid-free anaesthetic using nerve blocks enhances rapid recovery after minor hand surgery in children. Eur J Anaesthesiol. (2010) 27:521–5. 10.1097/EJA.0b013e3283349d68

27.

Barakat H Gholmieh L Nader JA Karam VY Albaini O Helou ME et al . Opioid-free versus opioid-based anesthesia in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a single-center, randomized, controlled trial. Perioper Med. (2025) 14:16. 10.1186/s13741-024-00486-5

28.

Saravanaperumal G Udhayakumar P . Opioid-free TIVA improves post- operative quality of recovery (QOR) in patients undergoing oocyte retrieval. J Obstet Gynaecol India. (2022) 72:59–65. 10.1007/s13224-021-01495-w

29.

Lee C Song YK Lee JH Ha SM . The effects of intraoperative adenosine infusion on acute opioid tolerance and opioid induced hyperalgesia induced by remifentanil in adult patients undergoing tonsillectomy. Korean J Pain. (2011) 24:7–12. 10.3344/kjp.2011.24.1.7

30.

Taşkaldiran Y . Is opioid-free anesthesia possible by using erector spinae plane block in spinal surgery?Cureus. (2021) 13:e18666. 10.7759/cureus.18666

31.

Lee JY Lim BG Park HY Kim NS . Sufentanil infusion before extubation suppresses coughing on emergence without delaying extubation time and reduces postoperative analgesic requirement without increasing nausea and vomiting after desflurane anesthesia. Korean J Anesthesiol. (2012) 62:512–7. 10.4097/kjae.2012.62.6.512

32.

Hansen EG Duedahl TH Rømsing J Hilsted KL Dahl JB . Intra-operative remifentanil might influence pain levels in the immediate post-operative period after major abdominal surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. (2005) 49:1464–70. 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2005.00861.x

33.

Feld JM Laurito CE Beckerman M Vincent J Hoffman WE . Non-opioid analgesia improves pain relief and decreases sedation after gastric bypass surgery. Can J Anaesth. (2003) 50:336–41. English, French. 10.1007/BF03021029

34.

Tverskoy M Oz Y Isakson A Finger J Bradley EL Jr Kissin I . Preemptive effect of fentanyl and ketamine on postoperative pain and wound hyperalgesia. Anesth Analg. (1994) 78:205–9. 10.1213/00000539-199402000-00002

35.

Krishnasamy Yuvaraj A Gayathri B Balasubramanian N Mirunalini G . Patient comfort during postop period in breast cancer surgeries: a randomized controlled trial comparing opioid and opioid-free anesthesia. Cureus. (2023) 15:e33871. 10.7759/cureus.33871

36.

Jose A Kaniyil S Ravindran R . Efficacy of intravenous dexmedetomidine-lignocaine infusion compared to morphine for intraoperative haemodynamic stability in modified radical mastectomy: a randomised controlled trial. Indian J Anaesth. (2023) 67:697–702. 10.4103/ija.ija_581_22

37.

Gazi M Abitagaoglu S Turan G Köksal C Akgün FN Ari DE . Evaluation of the effects of dexmedetomidine remifentanil on pain with the analgesia nociception index in the perioperative period in hysteroscopies under general anesthesia. A randomized prospective study. Saudi Med J. (2018) 39:1017–22. 10.15537/smj.2018.10.23098

38.

Maurer LR El Moheb M Cavallo E Antonelli DM Linov P Bird S et al . Enhanced recovery after surgery patients are prescribed fewer opioids at discharge: a propensity-score matched analysis. Ann Surg. (2023) 277:e287–93. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005042

39.

Zhang Y Ma D Lang B Zang C Sun Z Ren S et al . Effect of opioid-free anesthesia on the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Medicine. (2023) 102:e35126. 10.1097/MD.0000000000035126

40.