- 1Queen Elizabeth School, Kowloon, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 2Cognitio College (Kowloon), Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 3Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, Pok Fu Lam, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 4School of Nursing, Tung Wah College, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Rationale and background

The advancement of artificial intelligence has substantially transformed modern healthcare, particularly in diagnostic fields such as medical imaging, genomics, and clinical decision support (1). Algorithms are now capable of detecting early signs of cancer from imaging scans (2), classifying pathology slides (3), and predicting disease risks with increasing precision (4). However, these technologies rely heavily on structured digital inputs and large volumes of labeled data. The collection, annotation, and processing of such data often require costly infrastructure, specialized software, and trained personnel, which can limit their accessibility in community settings and low-resource environments (5, 6).

This limitation invites us to consider whether natural biological systems, such as the canine sense of smell, could serve as a complementary approach. Dogs possess an extraordinarily powerful olfactory system that allows them to detect subtle chemical signatures, including volatile organic compounds present in human biological samples (7, 8). When trained using structured protocols, dogs have demonstrated the ability to identify diseases such as cancer (9–11), malaria (12), and most recently, COVID-19 (13). Recent studies and reviews further highlight their potential role in cancer detection, with growing evidence that trained dogs can discriminate cancer-related scent signatures from biological samples (10, 11). In several countries, trained detection dogs were successfully used to screen for COVID-19 infection in public settings, including airports and mass gatherings, with high reported sensitivity (96%) and specificity (95%) (13).

These findings suggest that trained dogs could offer an innovative, non-invasive method for population-based disease screening. Their ability to process complex scent information in real time makes them a valuable addition to the broader diagnostic toolkit, particularly in contexts where conventional testing may be logistically challenging or economically prohibitive.

Local relevance in Hong Kong

Cancer is the leading cause of death in Hong Kong and accounts for about 25% of all registered fatalities in 2022 (14). Despite this considerable burden, cancer screening programs remain limited in scope and availability (15). At present, only a colorectal cancer screening program is offered to individuals between the ages of 50 and 75 (16). Other common cancers such as lung, liver, breast, and pancreatic cancers lack structured public screening initiatives. As a result, many patients are diagnosed at later stages when treatment is more complex and survival rates are reduced.

In this context, the need for innovative, accessible methods for early detection is growing. Hong Kong presents a unique opportunity to pilot new approaches due to its dense population (17), advanced healthcare infrastructure (18), and experience in public health operations. One promising direction may involve leveraging trained detection dogs. The use of detection dogs by the Hong Kong Customs and Excise Department to identify illegal drugs, firearms, and contraband goods has demonstrated their reliability in high-traffic, real-world settings (19). However, it is important to note that medical biodetection is considerably more complex, as volatile organic compound profiles associated with disease are more variable and subtle than contraband odors. Consequently, training techniques from law enforcement contexts cannot be directly applied and must be specifically adapted for medical detection. This established success in high-traffic environments such as airports and border control points demonstrates the reliability of detection dogs in complex, real-world scenarios. Nonetheless, hospitals and healthcare facilities represent different working environments that may require dogs with distinct temperaments and tailored training approaches. This established success in high-traffic environments such as airports and border control points highlights the feasibility of applying detection dogs for rapid, accurate screening in real-world healthcare settings (20). However, Hong Kong's unique environment, including high levels of urban air pollution and dense, overlapping scent profiles, may interfere with the accuracy of dogs' ability to detect cancer-related volatile organic compounds. Pilot studies should therefore carefully evaluate how these environmental factors affect canine performance and adapt training protocols to ensure reliable use in both community and clinical settings.

Building on their established use in public health during the COVID-19 pandemic, medically trained detection dogs could be further adapted to support early cancer detection initiatives. If trained to recognize scent patterns associated with cancer, these dogs could be integrated into community clinics or screening centers to support prescreening. In practice, this would most feasibly involve analyzing biological samples (e.g., breath, urine, or saliva) collected from individuals, rather than direct person-to-person screening, as the training and implementation constraints differ significantly between these approaches. This approach would require collaboration across sectors, including veterinary science, oncology, public health, and behavioral training but could serve as an effective supplement to conventional diagnostic tools.

Evidence base: remarkable nose of the dog

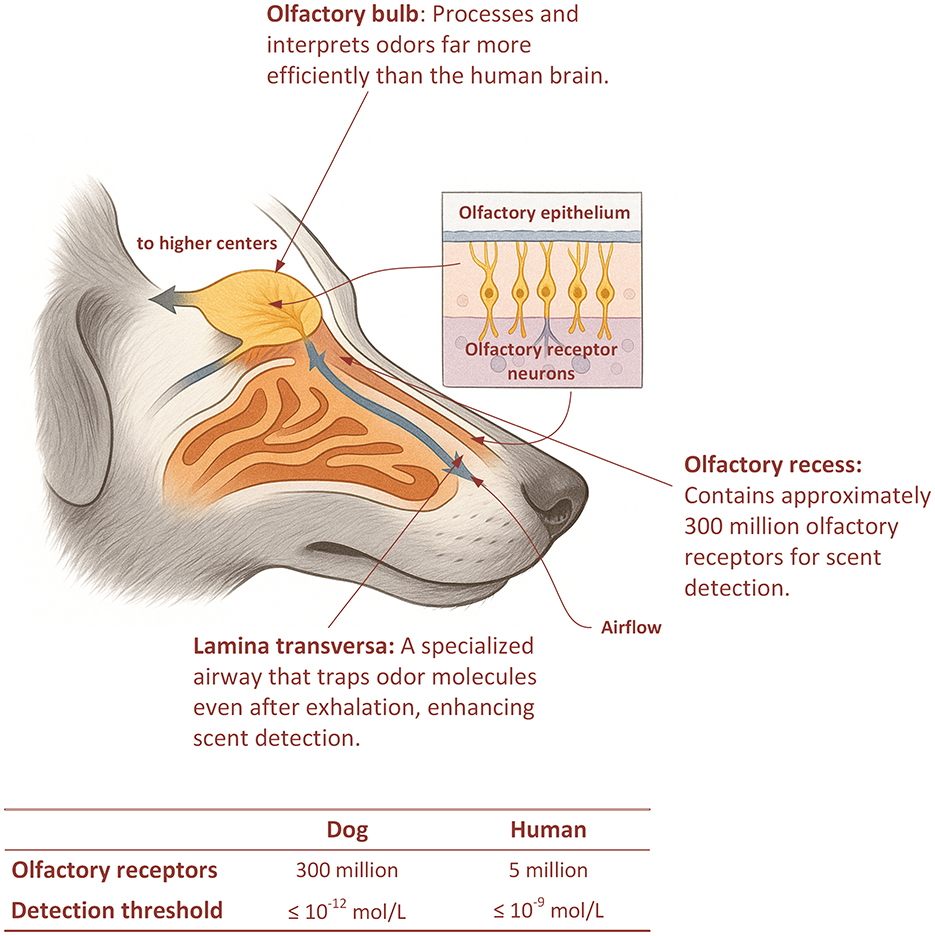

The dog (Figure 1) has one of the most advanced olfactory systems in the animal kingdom (24). Inside its nose are hundreds of millions of scent receptors, along with a highly developed olfactory bulb that processes chemical signals with exceptional precision. Dogs can detect minute amounts of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) released by the human body, including those linked to infections, metabolic changes, and even cancer (7, 25). However, a key limitation is that non-cancer factors such as infections, inflammation, diet, medications, or pollution may also alter VOC profiles (7, 26). Further research is needed to confirm whether dogs can consistently distinguish cancer-specific VOCs from these confounding sources. Nonetheless, their demonstrated ability to detect subtle volatile compounds provides the scientific rationale for training programs that harness this capacity for medical detection and early diagnosis.

Figure 1. Anatomy and comparative capacity of the canine olfactory system. The olfactory epithelium lining the turbinates contains approximately 300 million olfactory receptors, enabling detection of minute concentrations of volatile organic compounds associated with disease. Airflow through the lamina transversa facilitates odor capture even during exhalation, while neural signals are processed in the olfactory bulb and relayed to higher brain centers. Inset: olfactory receptor neurons within the epithelium. Table: comparison of canine vs. human olfactory capacity (olfactory receptors = 300 million vs. = 5 million; representative detection thresholds ≤10−12 mol/L vs. ≤ 10−9 mol/L, depending on odorant (21, 22). Illustration created by the authors using Adobe Illustrator, adapted from anatomical descriptions in Craven et al. (21) and Hermanson and De Lahunta (23).

For example, studies have shown that trained dogs can identify infectious diseases such as malaria and COVID-19 with high sensitivity and specificity (12, 27), and can also detect metabolic changes such as hypoglycemia in diabetes (28). These findings highlight the breadth of conditions detectable through canine olfaction and provide a stronger foundation for considering their application in medical contexts.

Evidence base: training medical detection dogs

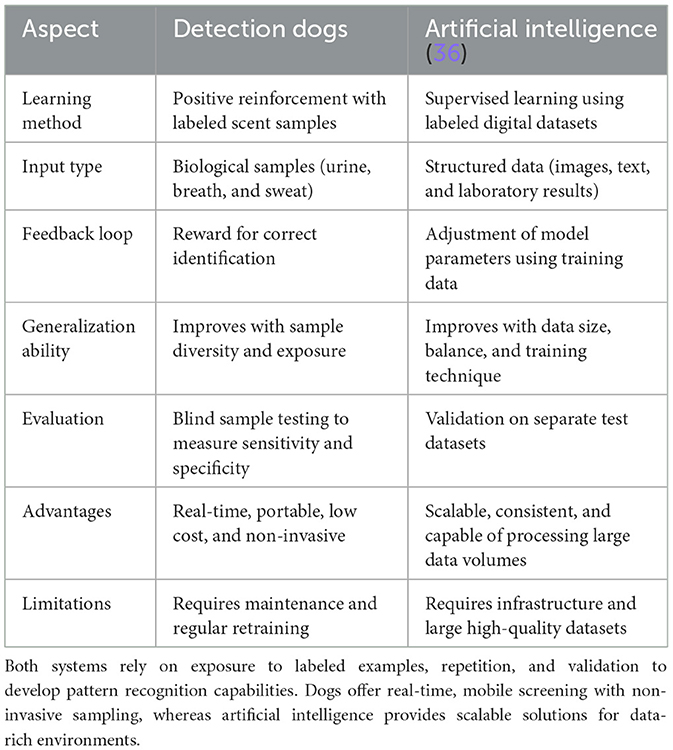

Just as artificial intelligence systems learn by analyzing large amounts of labeled data, medical detection dogs are trained through repeated exposure to biological samples collected from unique individuals. To ensure robust learning, these training sets should include samples from patients with confirmed cancer diagnoses (29), from individuals with other diseases that may mimic cancer-related scents, and from healthy controls drawn from similar environments as the cases and controls. Through positive reinforcement techniques, dogs learn to associate specific scent patterns, such as those released by cancer cells, with a reward. Importantly, these scent signatures may derive not only from the cancer cells themselves but also from the body's physiological and metabolic responses to the disease. Over time, they develop the ability to identify these scent markers with remarkable accuracy (30). However, one major challenge for wider adoption is the lack of standardized training protocols, sample collection methods (e.g., breath, urine, sweat), handling, and reward systems (29). Collaborative efforts across veterinary science, oncology, and public health are needed to develop rigorous, universally accepted guidelines. This training is similar to supervised learning in artificial intelligence, where a model improves its predictions by studying known examples. In both cases, structured training, validation, and continuous assessment are essential to ensure consistent performance in real-world conditions.

Evidence base: dog training and its analogy to artificial intelligence

Training a medical detection dog shares important similarities with how artificial intelligence models are developed in healthcare. In supervised machine learning, an algorithm learns to recognize patterns in structured data by analyzing numerous labeled examples (31). These labels, such as “cancer” or “non-cancer”, allow the model to adjust and improve its predictions based on experience.

Similarly, detection dogs are exposed to biological samples from individuals with known medical conditions (30). Trainers present scent samples collected from patients diagnosed with cancer and reward the dog each time it correctly identifies a positive case. Through repetition and reinforcement, the dog learns to recognize scent profiles linked to disease. Crucially, effective biodetection training requires dogs not only to identify cancer-related VOC signatures but also to discriminate them from samples of individuals with other illnesses and from healthy controls, while generalizing across diverse individual scent backgrounds. The greater the diversity and quality of the training samples, the better the dog becomes at identifying new and unfamiliar cases, much like a data model that has been trained on a comprehensive dataset (29).

Evaluation plays a key role in both methods. Dogs are assessed with blind testing to measure their ability to identify disease without prior cues correctly, just as machine learning models are evaluated on separate validation sets. While dogs and artificial intelligence differ in form, they share a process of structured learning and performance measurement (Table 1). Dogs offer the advantage of mobility, fast response, and an ability to detect disease without relying on imaging or laboratory tools, which makes them suitable for use in community and field settings.

Implementation pathway: strategy and relevance to Hong Kong

To harness the diagnostic potential of medical detection dogs, Hong Kong can adopt a flexible, community-centered implementation model. In countries such as the United Kingdom and Finland, trained dogs have been successfully deployed at healthcare facilities, transport hubs, and community screening events. Their agility and low operational burden make them particularly suitable for non-clinical settings (32, 33).

In Hong Kong, the Hospital Authority could integrate detection dogs into existing primary care services, including general outpatient clinics and public screening programs. A notable parallel is the colorectal cancer screening scheme, which has demonstrated that early detection substantially increases diagnosis rates compared with the general population (34). Hong Kong's Colorectal Cancer Screening Program reported a detection rate of 736.0 per 100,000 among screened participants, nearly double the incidence rate of 393.7 per 100,000 observed in the general population (34). A similar two-tiered strategy could be developed: canine prescreening to identify individuals with suspicious scent profiles, followed by targeted diagnostic imaging or laboratory testing for confirmation.

Importantly, the mobility of detection dogs opens further opportunities. These animals can be brought directly into community centers, residential care homes, and even individual residences. Nonetheless, training and maintaining a sufficient number of skilled detection dogs and handlers to cover Hong Kong's large population would pose logistical and financial challenges. For this reason, canine detection is best positioned as a prescreening tool or targeted intervention in high-risk or underserved groups, rather than a universal screening solution. Many old adults face mobility challenges and may not have easy access to magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography scans. Canine screening could provide a rapid, noninvasive first step that identifies at-risk individuals who might otherwise go undiagnosed.

This strategy offers potential clinical and economic advantages. However, a comprehensive assessment of feasibility would need to consider costs such as initial and ongoing training, handler support, veterinary care, and the number of screenings each dog can realistically perform. Early identification facilitates timely intervention, reduces the need for advanced-stage treatment, and can decrease long-term healthcare costs. The scalable, portable nature of dog-based screening also enables outreach to underserved populations, which aligns with goals of public health equity and preventive care.

Ethics, welfare, limitations, and conclusion

The integration of trained medical detection dogs into healthcare systems presents a unique opportunity to enhance early disease detection, particularly in settings where traditional diagnostics may be inaccessible, costly, or time consuming. In the era of artificial intelligence and advanced medicine, the remarkable sensory capabilities of dogs should not be overlooked. These capabilities are natural tools developed through evolution and successfully demonstrated in real-world applications, including the detection of cancers and infectious diseases. It is important to note that much of the current research on detection dogs has focused on training them to identify single cancer types, such as lung, breast, or pancreatic cancer (9, 25). However, recent studies suggest that trained dogs are capable of detecting a variety of cancers across different biological samples, indicating broader potential applications (10, 11). This highlights the need for cancer-specific training datasets and validation before broad application.

In Hong Kong, where an aging population and growing healthcare demands present substantial challenges, adopting a mobile, non-invasive, and cost-effective screening approach offers clear advantages. Whether positioned at outpatient clinics, community health centers, or brought to the homes of elderly individuals, detection dogs could serve as the first step in a tiered diagnostic model. Their role would be to identify individuals who may benefit from follow up investigations using imaging or laboratory testing. Importantly, practical and ethical aspects must be considered, including appropriate training methods, handler expertise, welfare safeguards (such as workload limits, rest periods, and veterinary oversight), and long-term sustainability. In addition, detection dogs should not be regarded merely as tools, but as sentient beings whose welfare must be safeguarded. Ethical safeguards should also include the consistent use of positive-reinforcement training, structured retirement planning, and transparent monitoring systems to ensure long-term welfare. These measures help maintain both animal wellbeing and public trust in the responsible deployment of medical detection dogs. Lessons learned from COVID-19 detection dog programs provide valuable insights into these challenges and their relevance for cancer detection (35).

The authors encourage public health authorities, researchers, and policymakers to explore pilot programs that assess the feasibility, accuracy, and value of canine-based screening in Hong Kong. Supporting this innovative, biologically grounded strategy can advance a new model of preventive healthcare, one that uses natural ability and modern science to improve access, equity, and outcomes for patients.

Author contributions

TL: Validation, Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. BT: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Validation. KN: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Conceptualization. SL: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Barański J. Intelligent revolution in medicine—the application of artificial intelligence (AI) in medicine: overview, benefits, and challenges. Przegl Epidemiol. (2024) 78:287–302. doi: 10.32394/pe/194484

2. Ardila D, Kiraly AP, Bharadwaj S, Choi B, Reicher JJ, Peng L, et al. End-to-end lung cancer screening with three-dimensional deep learning on low-dose chest computed tomography. Nat Med. (2019) 25:954–61. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0447-x

3. Coudray N, Ocampo PS, Sakellaropoulos T, Narula N, Snuderl M, Fenyö D, et al. Classification and mutation prediction from non-small cell lung cancer histopathology images using deep learning. Nat Med. (2018) 24:1559–67. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0177-5

4. Khera AV, Chaffin M, Aragam KG, Haas ME, Roselli C, Choi SH, et al. Genome-wide polygenic scores for common diseases identify individuals with risk equivalent to monogenic mutations. Nat Genet. (2018) 50:1219–24. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0183-z

5. Erickson BJ, Korfiatis P, Akkus Z, Kline TL. Machine learning for medical imaging. Radiographics. (2017) 37:505–15. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017160130

6. Kelly CJ, Karthikesalingam A, Suleyman M, Corrado G, King D. Key Challenges for delivering clinical impact with artificial intelligence. BMC Med. (2019) 17:195. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1426-2

7. Angle C, Waggoner LP, Ferrando A, Haney P, Passler T. Canine detection of the volatilome: a review of implications for pathogen and disease detection. Front. Vet. Sci. (2016) 3:47. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2016.00047

8. Walker DB, Walker JC, Cavnar PJ, Taylor JL, Pickel DH, Hall SB, et al. Naturalistic quantification of canine olfactory sensitivity. Appl Anim Behav Sci. (2006) 97:241–54. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2005.07.009

9. Liu SF, Lu HI, Chi WL, Liu GH, Kuo HC. Sniffer dogs diagnose lung cancer by recognition of exhaled gases: using breathing target samples to train dogs has a higher diagnostic rate than using lung cancer tissue samples or urine samples. Cancers (2023) 15:1234. doi: 10.3390/cancers15041234

10. Malone LA, Pellin MA, Valentine KM. Trained dogs can accurately discriminate between scents of saliva samples from dogs with cancer versus healthy controls. J Am Vet Med Assoc. (2023) 261:819–26. doi: 10.2460/javma.22.11.0486

11. Pellin MA, Malone LA, Ungar P. The use of sniffer dogs for early detection of cancer: a one health approach. Am J Vet Res. (2024) 85:1–5. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.23.10.0222

12. Guest C, Pinder M, Doggett M, Squires C, Affara M, Kandeh B, et al. Trained dogs identify people with malaria parasites by their odour. Lancet Infect Dis. (2019) 19:578–80. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30220-8

13. Ungar PJ, Pellin MA, Malone LA, A. One Health perspective: covid-sniffing dogs can be effective and efficient as public health guardians. J Am Vet Med Assoc. (2024) 262:13–6. doi: 10.2460/javma.23.10.0550

14. Hong Kong Cancer S. Overview of Cancer Statistics in Hong Kong Hong Kong: Hong Kong Cancer Strategy (2024). Available online at: https://www.cancer.gov.hk/en/hong_kong_cancer_of_cancer_statistics_in_hong_kong.html (Accessed November 11, 2025).

15. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. (2021) 71:209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

16. Chu CY, Huang J, Liew JJM, Sawhney A, Liu X, Zhong C. et al. Perceptions and attitudes toward utilizing a non-invasive biomarker for colorectal cancer screening: a qualitative study. Cancer Rep. (2025) 8:e70140. doi: 10.1002/cnr2.70140

17. Xie J, Wei N, Gao Q. Assessing spatiotemporal population density dynamics from 2000 to 2020 in megacities using urban and rural morphologies. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:14166. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-63311-5

18. Tse G, Lee Q, Chou OHI, Chung CT, Lee S, Chan JSK, et al. Healthcare big data in hong kong: development and implementation of artificial intelligence-enhanced predictive models for risk stratification. Curr Prob Cardiol. (2024) 49:102168. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2023.102168

19. Hong Kong C, Excise D. Customs Detector Dogs Hong Kong: Hong Kong Customs and Excise Department (n.d.). Available online at: https://www.customs.gov.hk/en/about-us/distinctive-customs/customs-detector-dogs/index.html (Accessed November 11, 2025).

20. Kantele A, Paajanen J, Turunen S, Pakkanen SH, Patjas A, Itkonen L, et al. Scent dogs in detection of COVID-19: triple-blinded randomised trial and operational real-life screening in airport setting. BMJ Global Health. (2022) 7:e008024. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-008024

21. Craven BA, Paterson EG. Settles GS. The fluid dynamics of canine olfaction: unique nasal airflow patterns as an explanation of macrosmia. J Royal Soc Interface (2010) 7:933–43. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2009.0490

22. McGann JP. Poor human olfaction is a 19th-century myth. Science (2017) 356:eaam7263. doi: 10.1126/science.aam7263

23. Hermanson JW, De. Lahunta A. Miller and Evans' Anatomy of the Dog-E-Book. Amsterdam: Elsevier Health Sciences (2018).

25. Willis CM, Church SM, Guest CM, Cook WA, McCarthy N, Bransbury AJ, et al. Olfactory detection of human bladder cancer by dogs: proof of principle study. BMJ (2004) 329:712. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7468.712

26. Leemans M, Bauër P, Cuzuel V, Audureau E. Fromantin I. Volatile organic compounds analysis as a potential novel screening tool for breast cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Inform. (2022) 17:11772719221100709. doi: 10.1177/11772719221100709

27. Grandjean D, Sarkis R, Lecoq-Julien C, Benard A, Roger V, Levesque E, et al. Can the detection dog alert on COVID-19 positive persons by sniffing axillary sweat samples? A proof-of-concept study. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0243122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243122

28. Rooney NJ, Guest CM, Swanson LCM. Morant SV. How effective are trained dogs at alerting their owners to changes in blood glycaemic levels?: Variations in performance of glycaemia alert dogs. PLoS ONE. (2019) 14:e0210092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210092

29. Pirrone F, Albertini M. Olfactory detection of cancer by trained sniffer dogs: a systematic review of the literature. J. Vet. Behav. (2017) 19:105–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jveb.2017.03.004

30. Sonoda H, Kohnoe S, Yamazato T, Satoh Y, Morizono G, Shikata K, et al. Colorectal cancer screening with odour material by canine scent detection. Gut (2011) 60:814–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.218305

32. Maughan MN, Best EM, Gadberry JD, Sharpes CE, Evans KL, Chue CC, et al. The use and potential of biomedical detection dogs during a disease outbreak. Front Med. (2022) 9:848090. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.848090

33. Wright S, McAree H, Hosey M, Tantam K, Connolly B. Animal-assisted intervention services across UK intensive care units: a national service evaluation. J Intens Care Soc. (2025) 26:68–79. doi: 10.1177/17511437241301000

34. Law C-C, Wong CHN, Chong PSK, Mang OWK, Lam AWH, Chak MMY, et al. Effectiveness of population-based colorectal cancer screening programme in down-staging. Cancer Epidemiol. (2022) 79:102184. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2022.102184

35. Otto CM, Sell TK, Veenema TG, Hosangadi D, Vahey RA, Connell ND, et al. The promise of disease detection dogs in pandemic response: lessons learned from COVID-19. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. (2021) 17:e20. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2021.183

Keywords: medical detection dogs, cancer screening, volatile organic compounds, artificial intelligence analogy, public health

Citation: Lo TQ, Tsui BCB, Ng KS and Lam SC (2025) Can dogs sniff out cancer? Exploring the role of medical detection dogs in Hong Kong's early diagnosis strategies. Front. Med. 12:1644112. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1644112

Received: 09 June 2025; Revised: 16 October 2025; Accepted: 10 November 2025;

Published: 24 November 2025.

Edited by:

Victoria Bunik, Lomonosov Moscow State University, RussiaReviewed by:

Katia Pinello, Veterinary Oncology Network (Vet-Onconet), PortugalCynthia M. Otto, University of Pennsylvania, United States

Huihua Zheng, Zhejiang Agriculture and Forestry University, China

Laurie Malone, University of Alabama at Birmingham, United States

Copyright © 2025 Lo, Tsui, Ng and Lam. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Simon Ching Lama, c2ltb25sYW1AdHdjLmVkdS5oaw==; c2ltbGNAYWx1bW5pLmN1aGsubmV0

†These authors share first authorship

Timothy Quan Lo

Timothy Quan Lo Bryden Chung Bun Tsui2†

Bryden Chung Bun Tsui2† Kei Shing Ng

Kei Shing Ng Simon Ching Lam

Simon Ching Lam