Abstract

Introduction:

Virtual Reality (VR) is an advanced technological system which, besides its use in entertainment and education, has been permanently introduced over the past quarter-century into physical and psychiatric rehabilitation as well as medicine. Its effectiveness has been demonstrated in pain management during medical and rehabilitation procedures in burn patients, alleviation of cancer pain, and reduction of labor pain. VR is increasingly used during routine medical procedures in children, such as blood sampling, intravenous cannulation, and vaccination, and holds promise for chronic pain management.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to assess pain during the treatment of hard-to-heal wounds of vascular origin using VR as an adjunct non-pharmacological pain therapy.

Materials and methods:

An observational study was conducted in a chronic wound care clinic involving 100 patients. The mean age was 68.02 ± 10.0 years. All participants had hard-to-heal wounds of vascular origin. The mean wound duration was 7.16 ± 5.08 months, with an average wound area of 39.18 ± 71.83 cm2 (range 2 cm2 to 625 cm2). Patients were randomly assigned to a group distracted with VR goggles and a control group receiving standard care without VR. Pain intensity was assessed using the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) at three time points, and the McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) before the procedure, during wound debridement, and 10 min after completion.

Results:

Statistically significant differences were observed in pain assessment before and during wound debridement (p < 0.05). In the VR group, higher pain scores were recorded before wound care compared to the control group. Ten minutes before wound debridement, the mean pain intensity in the VR group was 2.60 ± 1.63, higher than 2.0 ± 1.53 in the control group. During wound debridement, pain intensity was higher in the control group (4.94 ± 1.53) compared to the VR group (4.32 ± 2.17). Pain intensity 10 min after debridement was similar in both groups: control (2.24 ± 1.41) and VR (2.36 ± 1.71). These findings support the hypothesis that VR goggles reduce pain intensity. No statistically significant differences in NRS pain scores were found between patients with different wound types in either group (p > 0.05). Variables such as wound duration and wound size influenced pain levels 10 min before wound care. No association was found between sex and pain intensity (p > 0.005).

Conclusion:

Increased pain during procedures involving manipulation of damaged tissues and wound debridement is a common phenomenon. This study confirmed that the use of VR goggles reduces perceived pain levels. The assessment of pain experience and intensity varies depending on the assessment tools used; therefore, a combined quantitative and qualitative evaluation is recommended to accurately determine the usefulness of innovative tools in clinical practice.

1 Introduction

In recent years, there has been a steadily growing interest in modern technologies in medicine, which are opening new avenues for non-pharmacological support in alleviating acute pain associated with medical procedures, as well as for multimodal chronic pain management. One of the most promising technologies in this regard is Virtual Reality (VR), which is being increasingly applied across various areas of medicine, including the treatment of chronic wounds and the mitigation of procedural pain (1). In the medical context, Virtual Reality is defined as a three-dimensional, computer-generated environment, often delivered through a Head-Mounted Display (HMD), which fully immerses the user in a digital world and enables interaction with the generated surroundings (2).

Debridement, i.e., the removal of necrotic tissue, biofilm, and inflammatory debris from wounds, is a key component of the management of non-healing wounds, including those of vascular origin such as venous, arterial, and mixed pressure injuries. While this procedure offers significant therapeutic benefits—accelerating granulation tissue formation and reducing infection risk—it is frequently associated with severe, difficult-to-control pain (3, 4). Pain resulting from mechanical stimulation of the wound bed is often a major factor limiting patient cooperation and adversely affecting quality of life. Physical and psychological preparation, including education and basic psychological support, is particularly important in out-of-hospital settings where infiltration anesthesia options are limited (5, 6). Among patients receiving non-institutional care (long-term, hospice, or outpatient care), non-pharmacological pain-relief methods are of particular importance due to restricted access to specialized analgesics. An effective chronic wound management approach should focus not only on clinical aspects (e.g., selecting the appropriate debridement method) but also on patient comfort, engagement, and psychological well-being—by reducing distress related to dressing removal and wound preparation for re-dressing. These interventions align with the wound hygiene concept, whereby refreshing the wound bed and eliminating devitalized tissue reduces inflammation and strongly predicts healing outcomes (7, 8). In conventional clinical practice, procedural pain management during debridement relies primarily on pharmacological agents such as opioids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. However, these medications may cause adverse effects, especially in elderly patients who constitute the majority of those with vascular wounds. This has prompted the search for non-pharmacological solutions that are safe, effective, and suitable for home-based use. In this context, the implementation of innovative, non-invasive technologies—such as Virtual Reality—may serve as a valuable adjunct to standard interventions (9).

As a psychological intervention tool, Virtual Reality shows potential in modulating pain perception through mechanisms such as distraction and sensory immersion. Research indicates that patients undergoing VR therapy during painful procedures report lower pain intensity and improved psychological comfort (9, 10). This technology allows for the creation of interactive, engaging environments that divert the patient’s attention from painful stimuli to visually and acoustically attractive content. A growing body of evidence suggests that VR can be an effective tool for pain reduction in clinical care. In studies involving individuals with chronic pain, the use of VR during care procedures significantly reduced pain intensity and anxiety without the need for increased analgesic dosages. Such findings open new possibilities for holistic patient care (11, 12).

In non-institutional care settings, the acceptability and usability of VR technology by both patients and healthcare professionals are of critical importance. VR interfaces are becoming increasingly intuitive, and the devices themselves more affordable and portable, enabling easy integration into care environments (13). Moreover, some VR systems have already been adapted for use with telemedicine platforms, allowing for real-time monitoring of therapeutic outcomes and content adjustment. A crucial dimension of VR research in the context of vascular wounds is the psychological aspect. Chronic pain, fear of procedures, and limited mobility contribute to social isolation and depression among many patients with venous ulcers. Virtual Reality can serve not only as an analgesic tool but also as a motivational and emotionally supportive intervention (14). Interactive VR environments have been shown to improve mood, reduce anxiety, and enhance the overall perception of the treatment process. Given the new opportunities afforded by VR, a research initiative was undertaken to assess pain intensity using two standardized scales (the McGill Pain Questionnaire—MPQ and the Numeric Rating Scale—NRS) during the application of VR as a non-pharmacological intervention in the debridement of chronic, non-healing vascular wounds.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Ethics

The study received a favorable opinion from the Bioethics Committee of the University of Rzeszów, as documented in Resolution No. 054/12/2024 dated December 20, 2024. Additionally, approval for the study was granted by the Director of the Specialist Hospital, Podkarpackie Oncology Center in Brzozów. The entire research process was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring informed participation and the right to withdraw from the study at any stage without pressure from the researcher, without the need to provide a reason for withdrawal, and with the guarantee that participants would continue to receive standard medical care appropriate to their condition (15).

2.2 Study objective

The aim of the study was to assess pain using two scales (MPQ and NRS) during the debridement of hard-to-heal wounds of vascular origin using surgical tools (sharp debridement performed by nursing staff), by applying VR as an adjunctive method of non-pharmacological pain relief. A prospective quantitative-qualitative study design was used, based on the observation of 100 patients selected according to established inclusion and exclusion criteria. The study was conducted in the largest facility in southeastern Poland providing services in the treatment of chronic and non-healing wounds, selected due to the general availability of free healthcare services for insured individuals and its ability to care for a sufficient number of patients to determine a sample size necessary to detect differences. To this end, a power analysis was conducted and calculations were performed using G*Power software with the following assumptions: effect size d = 0.6; alpha = 0.05; power = 0.8. The analysis showed that a minimum sample size of 47 participants was necessary to obtain reliable results. The study was conducted over a four-month period from December 2024 to March 2025 at the Wound Treatment Outpatient Clinic of the Podkarpackie Oncology Center in Brzozów. Participation in the study was offered to patients receiving treatment for chronic and hard-to-heal wounds of vascular origin at this facility.

A purposive sampling approach was used, which meant that all clinic visits over the 6 months preceding the study (2,521 visits) involving 365 patients were analyzed. Patients with cancer-related wounds, ongoing wound and skin infections, pressure injuries, and improperly healing postoperative wounds were excluded from further consideration. This selection process identified a group of 123 patients who met the established inclusion criteria for the study sample. These criteria included the presence of venous ulceration classified as active, full preservation of auto- and allopsychic orientation, ability to communicate and express emotions, with wound area >10 cm2, and patients with diabetic foot disease (DFD) meeting the following conditions: wound area >2 cm2, WIFI >1, wound duration of at least 4 weeks and no more than 18 months, and pain level assessed on the NRS scale <4. In the case of patients with diabetic foot disease, individuals with smaller wound areas were included; however, due to the aggressive nature of the disease, these patients were at high risk of deep tissue and bone damage. Patients with wounds of non-vascular etiology and those reporting pain experiences >4 on the NRS scale were excluded from the study, including individuals presenting extreme pain sensations accompanied by excessive emotional responses (n = 6). Additional exclusion criteria included active inflammatory conditions or immunological disorders confirmed by the following findings: body temperature >38 °C, heart rate >90 beats/min, leukocytosis >12,000 or <4,000. The application of these inclusion and exclusion criteria resulted in the selection of 123 patients; however, 23 patients were ultimately disqualified due to analgesia, and none of the enrolled patients declined participation in the study, meaning they did not report any pain experience—even minimal—during sharp wound debridement (tissue manipulation with a surgical curette and scissors, debridement using a wound pad, or during surgical necrectomy). Ultimately, questionnaires from 100 patients who provided informed consent to participate after receiving complete information about the study objectives and procedures were included in the statistical analysis. None of the enrolled participants had uncorrected visual or hearing impairments, nor age-related conditions that would have prevented them from providing informed consent to participate in the study. The main study involved observing and comparing pain experiences occurring during the peri-procedural period (before starting the wound debridement, during the procedure, and 10 min after the medical intervention). Wound debridement and dressing changes were performed aseptically and gently, in accordance with current procedures, using topical anesthesia with 2% lidocaine gel applied to the surface of the skin and damaged tissues 3–5 min before starting the intervention. A simple randomization method was employed. Patients were randomly assigned (using the “random” function in Excel 2019) to Group A, which did not use VR goggles, and Group B, which used VR goggles during the wound debridement procedure. Each participant was informed of their group allocation. In Group B, VR goggles (Oculus Meta Quest 3, 128 GB, produced by Meta Platforms, Inc., Menlo Park, California, USA) were used for attention distraction during the wound care procedures. During the study, short films selected according to patient preferences were shown with accompanying sound. The films focused on nature and architectural themes and included one of four options: exotic beaches, forest trails, the underwater world, and the most fascinating buildings and landmarks in the world. VR projections began a few minutes before the start of the wound debridement and dressing change procedure and lasted until the end of the intervention, which in some cases required the looping of the video to play multiple times. During the study, the VR goggles were disinfected after each use according to established hospital procedures and the principles for disinfecting reusable equipment. None of the participants undergoing the VR sessions reported any adverse effects such as dizziness, eye fatigue, or nausea. Sample photos from the study are presented in Photo 1.

PHOTO 1

Use of VR during sharp debridement of vascular etiology wounds in the context of outpatient nursing care.

2.3 Data collection

The research protocol consisted of two parts. The first part involved collecting sociodemographic data (gender, age, place of residence, marital status, education, and economic status), assessing self-care levels using the Barthel Index, and evaluating tissue injury characteristics (type, size, depth of the wound, and duration of pathological changes). Wound assessment employed a simple classification of partial-thickness skin injury, full-thickness injury, and damage involving deeper tissues, alongside the EPUP/NPIAP scale, WIfI, and RYB classifications. The second part gathered information on pain experiences in both groups A and B, using the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) and the McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ, R. Melzack). Patients easily indicated pain intensity on the NRS (0 = no pain; 10 = worst possible pain), but given pain’s individual and subjective nature, qualitative assessment was also performed using the Polish-adapted McGill Pain Questionnaire by Kołłątaj et al. (16, 17). This instrument assesses sensory (groups 1–10), emotional (groups 11–15), and subjective (group 16) pain dimensions, along with additional categories (groups 17–20). Participants were instructed to read all descriptors in each group at least once and select only those accurately describing their pain. The questionnaire characterized pain by the number of words chosen (NWC), the pain rating index (PRI) based on mean and rank values, and the Present Pain Intensity (PPI) on a six-point scale (0 = no pain; 5 = excruciating pain). It also included items assessing pain’s impact on daily activities, sleep, and nutrition, and characterized pain temporal patterns (continuous, intermittent, momentary). Patients could indicate pain location on a front-and-back human figure diagram.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 21. To accurately assess relationships between variables, descriptive statistics, histograms, and boxplots were employed, alongside Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests for normality of distributions. Spearman’s rank-order correlation (rho), Kruskal–Wallis tests, and Mann–Whitney U tests were used to evaluate differences in the distributions of dependent variables across categories of independent variables.

3 Results

3.1 Characteristics of respondents

The mean age of participants was 68.02 ± 10.0 years, with a median of 70; in group A (without VR goggles), the mean age was 67.46 ± 11.27, median 67, and in group B (with VR goggles), 68.58 ± 8.63, median 70. The age range for the entire cohort was 43 to 89 years (group A: 43–89 years, group B: 46–85 years). Over 30% of all participants were aged up to 64 years, 45.0% were between 65 and 74 years old, and 25.0% were older than 75 years. The gender distribution was nearly equal, with 51% female and 49% male participants (group A—females 46.0%, males 54.0%; group B—females 56.0%, males 44.0%). Regarding place of residence, 62.0% of participants lived in rural areas, while 38.0% were urban residents (group A: city 48.0%, rural 52.0%; group B: city 28.0%, rural 72.0%). Respondents were assessed for self-care ability using the Barthel Index, achieving an overall mean score (M ± SD) of 89 ± 12.53, with a median of 90 (group A: 88.2 ± 13.69, median 90; group B: 89.80 ± 11.34, median 90). Across the entire cohort and within groups A and B, Barthel Index scores ranged from 40 to 100. The majority of participants (61.0%) were classified as self-care competent, scoring between 86 and 100 (group A—62.0%, group B—60%), while 39.0% exhibited mild self-care deficits, scoring between 21 and 85 (group A—38.0%, group B—40.0%). None of the participants were classified as unable to perform self-care. The use of the McGill Pain Questionnaire also allowed for the assessment of subjective symptoms accompanying pain experienced by participants, as well as the impact of pain on daily activity, sleep, and nutrition. In the entire group, 89.0% reported good nutrition, followed by 6.0% reporting reduced nutrition and 2.0% reporting limited nutrition. Seventy percent reported good sleep quality, 25.0% experienced restless sleep, and 3.0% complained of insomnia.

3.2 Characteristics of wounds and pain treatment

In the studied cohort, venous ulcers predominated (49.0%), followed by mixed ulcers (35.0%), diabetic foot ulcers (DFU) (10%), and arterial ulcers (6.0%). The mean duration of ulcer existence was 7.16 ± 5.08 months, with a median of 5 months (group A: 5.92 ± 4.49 months, median 4; group B: 8.40 ± 5.36 months, median 7). Analysis of ulcer location revealed the following distribution: medial part of the lower leg (55.0%), lateral part of the lower leg (25.0%), foot (14.0%), and circumferential lesion on the lower leg (6.0%). The average wound size in cm2 was 39.18 ± 71.83, with a median of 17 (group A: 23.61 ± 30.29, median 15; group B: 54.74 ± 94.94, median 29). The wound area ranged from 2 to 625 cm2 overall (group A: 3–150 cm2; group B: 2–625 cm2). Tissue destruction analysis according to the NPIAP classification showed a mean score of 2.68 ± 0.62, median 3, indicating that over half of the patients (52.0%) had full-thickness skin ulcers (grade 3 tissue destruction). Partial-thickness skin wounds (grade 2 NPIAP) accounted for 40.0% of the group, and 8.0% had wounds penetrating deeper tissues (grade 4). The wound assessments according to the NPIAP, RYB, and WIfI classifications are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

| Total Group | Group A | Without VR Goggles | Group B | With VR Goggles | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Tissue destruction assessment according to NPIAP classification | ||||||

| Grade 2 (partial-thickness skin damage) | 40 | 40.0% | 22 | 44.0% | 18 | 36.0% |

| Grade 3 (full-thickness skin damage) | 52 | 52.0% | 24 | 48.0% | 28 | 56.0% |

| Grade 4 (penetrating wound) | 8 | 8.0% | 4 | 8.0% | 4 | 8.0% |

| Total | 100 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% |

| Wound assessment using the RYB scale | ||||||

| Red | 8 | 8.0% | 7 | 14.0% | 1 | 2.0% |

| Red-yellow | 67 | 67.0% | 31 | 62.0% | 36 | 72.0% |

| Yellow | 22 | 22.0% | 11 | 22.0% | 11 | 22.0% |

| Black | 3 | 3.0% | 1 | 2.0% | 2 | 4.0% |

| Total | 100 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% |

| WIfI assessment | ||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1.0% | 1 | 2.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| 2 | 11 | 11.0% | 5 | 10.0% | 6 | 12.0% |

| 3 | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Not specified | 88 | 88.0% | 44 | 88.0% | 44 | 88.0% |

| Total | 100 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% |

Wound assessment according to NPIAP, RYB, and WIfI classifications.

All patients included in the study underwent wound cleansing prior to dressing application. Among the selected debridement methods, scraping was the most commonly used (overall 70.0%, group A 68.0%, group B 72.0%), followed by scraping combined with removal of devitalized tissue (overall 27.0%, group A 30.0%, group B 24.0%), and necrosectomy (overall 3.0%, group A 1.0%, group B 2.0%). Nearly three-quarters of the vascular ulcer cohort used analgesics on an as-needed basis (overall 72.0%, group A 74.0%, group B 70.0%), while 28.0% of the total cohort took analgesics regularly and in a planned manner (group A 26.0%, group B 30.0%). The majority used first-step analgesics from the WHO analgesic ladder, most commonly over-the-counter drugs (75.0%). Weak opioids combined with other non-opioid drugs were used by 23.0% of respondents, whereas third-step analgesics were prescribed to 2.0% of patients. Analysis of patients’ pain experiences and their impact on other daily activities, as reported in the MPQ questionnaire before wound treatment, showed that most participants complained of intermittent pain (54.0%), momentary pain (40.0%), and continuous pain (5.0%).

3.3 Pain symptoms during wound cleansing

Pain intensity was assessed using the NRS and MPQ scales at two time points: 10 min before wound debridement and during the wound cleansing procedure. The mean pain intensity in the entire cohort 10 min before the procedure was 2.30 ± 1.60, with a median of 2 (group A: 2.0 ± 1.53, median 2; group B: 2.60 ± 1.63, median 3). During wound cleansing, pain intensity increased overall to a mean of 4.63 ± 1.89 (group A: 4.94 ± 1.53, median 5; group B: 4.32 ± 2.17, median 4). Significant differences in pain assessment between groups A and B were observed both 10 min before and during wound cleansing. Ten minutes prior, the median pain score was higher in group B than in group A; however, during the procedure, this trend reversed, with group A reporting higher median pain scores than group B. These findings suggest that focusing attention on a VR-displayed video and sparing patients from unpleasant visual stimuli such as devitalized tissue, pus, and blood reduces pain perception and helps alleviate pain during wound cleansing and dressing changes. The results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

| Assessment 10 min before wound cleansing | Assessment during wound cleansing | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Group A—without VR goggles | Group B—with VR goggles | Total | Group A—without VR goggles | Group B—with VR goggles | |

| Mean | 2.30 | 2.00 | 2.60 | 4.63 | 4.94 | 4.32 |

| SD | 1.60 | 1.53 | 1.63 | 1.89 | 1.53 | 2.17 |

| Median | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Min | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Max | 4 | 4 | 4 | 10 | 8 | 10 |

| Q1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Q3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 5 |

| n | 100 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 50 | 50 |

Pain intensity measured by NRS 10 minutes before and during wound cleansing in the overall cohort and groups A and B.

A similar assessment was conducted using the McGill Pain Questionnaire developed by R. Melzack at identical time points—10 min before wound treatment and during the cleansing process. The questionnaire consists of multiple components, each evaluated separately. The Pain Rating Index (PRI) before the medical intervention averaged 3.68 ± 3.35 with a median of 3 in the entire group (Group A: 3.36 ± 2.75; Group B: 4.0 ± 3.87). During wound treatment, the PRI averaged 3.49 ± 2.66 with a median of 3 overall (Group A: 3.9 ± 3.08; Group B: 3.08 ± 2.13). Results are presented in Table 3 and illustrated by a boxplot (Figure 1).

Table 3

| Assessment 10 min before wound treatment | Assessment during wound treatment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Group A—without VR goggles | Group B—with VR goggles | Total | Group A—without VR goggles | Group B—with VR goggles | |

| Mean | 3.68 | 3.36 | 4.00 | 3.49 | 3.90 | 3.08 |

| SD | 3.35 | 2.75 | 3.87 | 2.66 | 3.08 | 2.13 |

| Median | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Min | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Max | 24 | 9 | 24 | 12 | 12 | 8 |

| Q1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Q3 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 4 |

| n | 100 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 50 | 50 |

Pain rating index (PRI) 10 minutes before and during wound treatment.

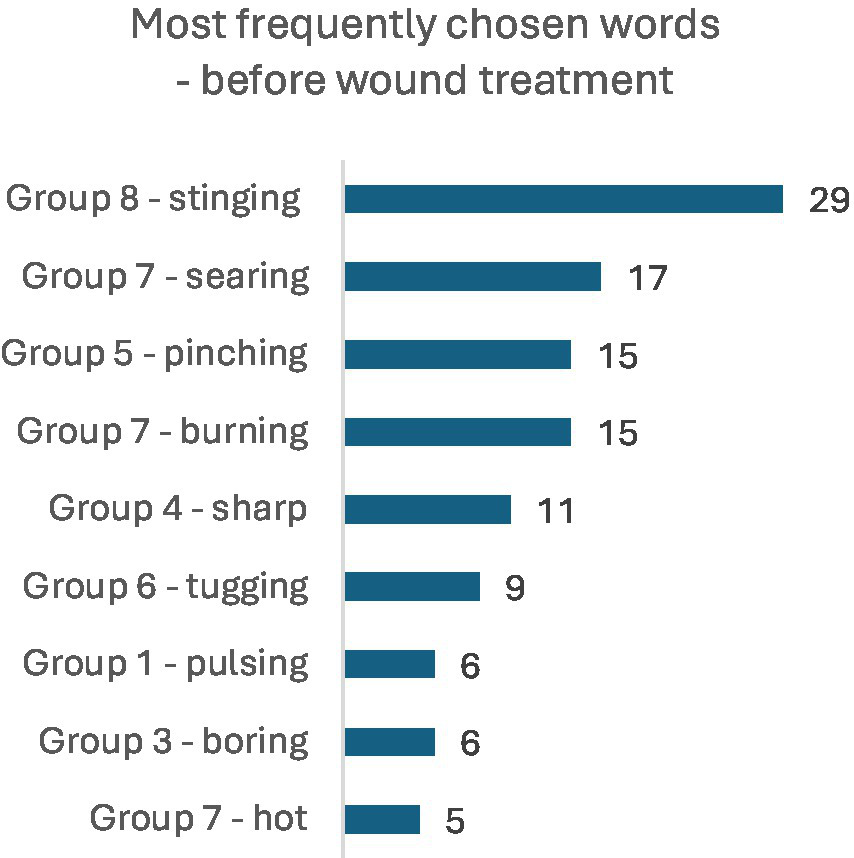

Figure 1

Most frequently chosen words in the MPQ 10 min before wound treatment (NWC).

The next evaluated indicator was the Number of Words Chosen (NWC) to describe pain experiences. Ten minutes before wound cleansing, the overall mean in this category was 1.59 ± 1.16, with a median of 2 (Group A: 1.54 ± 1.09, median 1; Group B: 1.64 ± 1.22, median 2). During wound cleansing, the overall mean NWC value was 1.55 ± 0.93, with a median of 1 (Group A: 1.80 ± 1.01, median 2; Group B: 1.30 ± 0.78, median 1). The results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4

| Assessment 10 min before wound treatment | Assessment during wound treatment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Group A—without VR goggles | Group B—with VR goggles | Total | Group A—without VR goggles | Group B—with VR goggles | |

| Mean | 1.59 | 1.54 | 1.64 | 1.55 | 1.80 | 1.30 |

| SD | 1.16 | 1.09 | 1.22 | 0.93 | 1.01 | 0.76 |

| Median | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Min | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Max | 8 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Q1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Q3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| n | 100 | 50 | 50 | 100 | 50 | 50 |

Number of words chosen (NWC) at 10 minutes before and during wound cleansing.

Based on the Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test, it can be concluded that the distributions of the PRI and NWC variables significantly differ from a normal distribution (Table 5).

Table 5

| Group | Kolmogorov–Smirnov | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | df | Significance | ||

| Pain Rating Index—10 min before | Group A—no VR goggles | 0.132 | 50 | 0,029 |

| Group B –VR goggles | 0.179 | 50 | 0.000 | |

| Pain Rating Index—during | Group A—no VR goggles | 0.195 | 50 | 0.000 |

| Group B—VR goggles | 0.154 | 50 | 0.005 | |

| Number of Words Chosen—10 min before | Group A—no VR goggles | 0.210 | 50 | 0.000 |

| Group B—VR goggles | 0.304 | 50 | 0.000 | |

| Number of Words Chosen—during | Group A—no VR goggles | 0.246 | 50 | 0.000 |

| Group B—VR goggles | 0.293 | 50 | 0.000 | |

Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality tests of PRI and NWC distributions 10 minutes before and during wound treatment in groups A and B.

In the statistical evaluation using the Mann–Whitney U test, the comparison of PRI distributions 10 min before and during wound treatment between groups A and B showed no statistically significant differences at either time point. However, for the NWC, no significant difference was found between groups A and B in the distribution of selected words 10 min before wound treatment (p > 0.05). A significant difference was observed in the distribution of NWC during wound treatment (p = 0.016). The median in group B (with VR goggles) was lower than in group A (without VR goggles), indicating that group B, on average, chose fewer words describing pain than group A. The data are presented in Table 6.

Table 6

| Pain rating index - 10 min before | Pain rating index - during | Number of words chosen - 10 min before | Number of words chosen - during | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mann–Whitney U | 1150.000 | 1125.000 | 1201.000 | 923.500 |

| Wilcoxon W | 2425.000 | 2400.000 | 2476.000 | 2198.500 |

| Z | −0.695 | −0.871 | −0.355 | −2.420 |

| Asymptotic significance (2-tailed) | 0.487 | 0.384 | 0.722 | 0.016 |

Mann–Whitney U test statistics—comparison of PRI and NWC distributions 10 minutes before and during wound treatment between groups A and B.

Present Pain Intensity (PPI) assessed using the MPQ questionnaire 10 min before the examination indicates low pain intensity in the overall group (1.29 ± 0.87), in Group A (1.14 ± 0.76), and in Group B (1.44 ± 0.95). However, during the examination, an increase in pain intensity was recorded, with the mean value rising to 2.69 ± 0.97 in the overall group, 2.90 ± 0.91 in Group A, and 2.48 ± 0.97 in Group B. Very severe pain sensations were not confirmed in the MPQ assessment (Tables 7, 8).

Table 7

| CPI | Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | A - no VR Goggles | B - VR Goggles | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 0-no pain | 16 | 16.0% | 9 | 18.0% | 7 | 14.0% |

| 1-mild | 50 | 50.0% | 27 | 54.0% | 23 | 46.0% |

| 2-discomforting | 23 | 23.0% | 12 | 24.0% | 11 | 22.0% |

| 3-distressing | 11 | 11.0% | 2 | 4.0% | 9 | 18.0% |

| 4-horrible | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| 5-exruciating | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Total | 100 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% |

MPQ present pain intensity (PPI) before wound treatment in groups A and B.

Table 8

| PPI | Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | A - no VR Goggles | B - VR Goggles | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 0-no pain | 3 | 3.0% | 1 | 2.0% | 2 | 4.0% |

| 1-mild | 9 | 9.0% | 4 | 8.0% | 5 | 10.0% |

| 2-discomforting | 22 | 22.0% | 5 | 10.0% | 17 | 34.0% |

| 3-distressing | 48 | 48.0% | 29 | 58.0% | 19 | 38.0% |

| 4-horrible | 18 | 18.0% | 11 | 22.0% | 7 | 14.0% |

| 5-exruciating | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Total | 100 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% | 50 | 100.0% |

MPQ present pain intensity (PPI) during wound treatment in groups A and B.

A comparison was made of pain experiences measured by the NRS scale and collected using the MPQ questionnaire. In both groups, fairly high and statistically significant correlation coefficients were observed between the NRS scores and the Pain Rating Index (PRI) as well as the Number of Words Chosen (NWC) before the procedure. The obtained data indicate that assessments made prior to the procedure are consistent (p < 0.05). However, pain measurements taken during wound treatment show divergence when comparing these tools. The correlation coefficients of the analyzed variables during the procedure are low, yet statistically significant (p < 0.05), especially in the area of Present Pain Intensity (PPI). The data are presented in Table 9.

Table 9

| n = 50 per group | NRS 10 min before the procedure | NRS during the procedure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman’s rho | Sig (2-sided) |

Spearman’s rho | Sig (2-sided) |

|

| Group A | ||||

| PPI (Present Pain Intensity) 10 min before the procedure | 0.587 | 0.000 | ||

| PPI (Present Pain Intensity) during the procedure | 0.358 | 0.011 | ||

| PRI (Pain Rating Index) 10 min before the procedure | 0.660 | 0.000 | ||

| PRI (Pain Rating Index) during the procedure | 0.215 | 0.134 | ||

| NWC (Number of Words Chosen) 10 min before the procedure | 0.641 | 0.000 | ||

| NWC (Number of Words Chosen) during the procedure | 0.259 | 0.069 | ||

| Group B | ||||

| PPI (Present Pain Intensity) 10 min before the procedure | 0.906 | 0.000 | ||

| PPI (Present Pain Intensity) during the procedure | 0.774 | 0.000 | ||

| PRI (Pain Rating Index) 10 min before the procedure | 0.639 | 0.000 | ||

| PRI (Pain Rating Index) during the procedure | 0.253 | 0.076 | ||

| NWC (Number of Words Chosen) 10 min before the procedure | 0.578 | 0.000 | ||

| NWC (Number of Words Chosen) during the procedure | 0.185 | 0.199 | ||

Spearman’s rho correlation coefficients between NRS and MPQ (PPI, NWC, and PRI) in groups A and B before and during the procedure.

Among the most frequently chosen words describing pain in the MPQ 10 min before wound treatment, the dominant terms were: stinging (n = 29), searing (n = 17), pinching and burning (n = 15), and sharp (n = 11). Next in frequency were: tugging (n = 9), pulsing and boring (6 persons each), and hot (n = 5). The set of selected words changed during wound treatment, with the most commonly chosen words being: stinging (n = 22), annoying and searing (15 persons each), burning (n = 12), boring (n = 10), pinching (n = 9), hot (n = 6), and pulsing (n = 5). Detailed results are illustrated in the figures. The set of pain descriptors indicates the presence of pain of a neuralgia type (Figures 1, 2).

Figure 2

Most frequently chosen words in the MPQ during wound treatment (NWC).

4 Discussion

In recent decades, intensified research on pain has led to the development of the biopsychosocial paradigm, followed by an updated definition of pain in 2020 by experts from the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). Pain is now defined as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage” (18). The recognition of pain as a subjective experience influenced by both biological and psychosocial factors introduces certain challenges in assessment—particularly in cases involving individual perception and confounding factors such as older age, gender, and personal constitutional characteristics. In the present study, which examined the potential use of virtual reality (VR) during wound cleansing procedures, several interesting variables and distracting factors were observed that may influence pain intensity ratings (10). It was noted that individuals with ischemic wounds, women, and those reporting fatigue and restless sleep demonstrated a heightened pain threshold. Subjective assessments of pain were conducted using two clinical scales (NRS and MPQ). Additional statistical analyses were carried out to explore the main research aim: investigating the relationship between patient distraction using an advanced VR system and the experience of potential pain before and during the cleansing of vascular wounds.

Over the past decade, researchers have increasingly pointed to virtual reality (VR) in the context of emotional, affective, and cognitive responses that influence the complex system of pain modulation (19–21). In an effort to understand the mechanistic origin of VR-induced analgesia, analyses have focused on the neurobiological interaction between cortical brain activity and neurochemistry, as well as processes related to attention, emotional regulation, and cognition. One of the significant milestones in this area is the Gate Control Theory proposed by Melzack and Wall, which suggested a correlation between levels of attention and emotion related to pain and the subsequent perception and interpretation of pain experiences (22). An extension of this theory came from McCaul and Malott, who argued that due to the limited capacity of attention, a person must focus on a stimulus for it to be perceived as painful. This led to the hypothesis that if one’s attention is engaged elsewhere, painful stimuli—although present—will be perceived as less intense (23). A further breakthrough was the Multiple Resources Theory introduced by Wickens, which demonstrated the independent functioning of resources across different sensory systems. These findings support the rationale for using multimodal distractions (visual, auditory, tactile, and olfactory) through VR technologies and their implementation in medical practice (24).

In a prospective observational study conducted within a wound care outpatient clinic, Oculus Meta Quest® 3 goggles were used during the procedure of wound debridement and dressing (scraping and removal of necrotic tissue). Of the 123 patients with chronic vascular wounds, 100 were included in the analysis: 49.0% (n = 49) men and 51.0% (n = 51) women. The participants’ ages ranged from 43 to 89 years, with a mean age of 68.02 ± 10.0 years. During the qualification process, patients were randomly assigned to two groups: Group B (with VR goggles) and Group A (without goggles). Prior to the procedure, all patients received lignocaine gel for local anesthesia of the wound bed. The majority had venous (49.0%) or mixed etiology wounds (35.0%), most commonly located on the medial (55.0%) or lateral (25.0%) aspects of the lower leg. Most participants were self-sufficient in daily care (61.0%), while 39.0% presented with minor deficits. Only 28.0% of patients were on regular analgesic treatment; the remainder used painkillers occasionally in response to increasing pain. Before the therapeutic procedures, pain intensity did not exceed 4 points on the NRS, with a mean of 2.3 ± 1.8 across both groups. Pain intensity was assessed using two scales: the MPQ and the NRS. The MPQ questionnaire was used before and during the wound debridement, while the NRS scale was applied for direct subjective assessment before, during, and 10 min after the procedure. According to NRS scores, participants in the VR group (B) reported lower pain intensity before the procedure (2.0 ± 1.53) compared to the non-VR group (A) (2.6 ± 1.63). During the procedure, lower pain ratings were again recorded in Group B (4.32 ± 2.17) compared to Group A (4.94 ± 1.53) (p < 0.05). Ten minutes after the procedure, a reduction in pain intensity was observed: 2.24 ± 1.41 in Group A and 2.36 ± 1.71 in Group B. In the VR group, the median NRS pain score increased by 3 points during the procedure, whereas in the non-VR group, it increased by only 1 point. The McGill Pain Questionnaire is a quantitative and qualitative tool used to assess pain of various etiologies. It consists of 20 pain descriptors (Number of Words Chosen—NWC), a Pain Rating Index (PRI), and a measure of Present Pain Intensity (PPI).

Among the most frequently chosen words describing pain in the McGill Pain Questionnaire 10 min before wound care, the predominant descriptors were: stinging (n = 29), searing (n = 17), pinching and burning (n = 15), and sharp (n = 11). The next most frequent descriptors included: tugging (n = 9), pulsing and boring (n = 6), and hot (n = 5). The repertoire of chosen words changed during the wound care procedure, with the most frequently selected descriptors being: stinging (n = 22), annoying (n = 15), searing (n = 15), burning (n = 12), boring (n = 10), pinching (n = 9), hot (n = 6), and pulsing (n = 5). The range of words describing pain in patients’ assessments indicates the presence of pain associated with nerve ending irritation, suggestive of neuralgia. The pain assessment index before the start of the medical intervention in the entire study group averaged 3.68 ± 3.35, median 3 (in group A: 3.36 ± 2.75, in group B: 4.0 ± 3.87), whereas during wound care the Pain Rating Index (PRI) was 3.49 ± 2.66, median 3 (group A: 3.9 ± 3.08, group B: 3.08 ± 2.13). Statistical evaluation using the Mann–Whitney U test showed no significant differences in Pain Rating Index (PRI) distributions between groups A and B at the two time points (p > 0.05). Similarly, no statistically significant differences were observed between groups A and B in the distribution of the Number of Words Chosen (NWC) 10 min before wound care (p > 0.05). However, significant differences were found in the distribution of NWC during wound care (p = 0.016). The median NWC in group B (with VR goggles) was lower than in group A (without VR goggles), indicating that group B on average selected fewer pain descriptors than group A. Considering parameters defining Present Pain Intensity (PPI), very interesting observations were made based on the Likert scale assessment (no pain, mild, discomforting, distressing, horrible, excruciating). A comparison was made between pain sensation data measured by the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) and data collected via the MPQ questionnaire. Both groups showed relatively high and statistically significant correlation coefficients between the NRS score and the Pain Rating Index (PRI), as well as the Number of Words Chosen (NWC) before the procedure. These data indicate consistency in pre-procedure assessments (p < 0.05). However, pain measurements conducted during wound care showed discrepancies between these tools. The correlation coefficients for the analyzed features during the procedure remained statistically significant (p < 0.05), especially in the PPI domain. Although the assessments using the two scales differ, they clearly indicate lower pain experiences in the group where VR goggles were used. Assessment of pain intensity using numerical and analog scales is straightforward but not without errors, as it represents subjective perception of negative sensations, which is individual to each patient. Researchers studying pain intensity phenomena should be aware that patients may overestimate or underestimate pain by reporting extreme values depending on the context. In our study, several extreme cases related to pain sensations were excluded, specifically 3 women reporting pain intensity above 10 points without typical symptoms indicating very severe pain stimuli. The correlation between NRS pain scores and MPQ questionnaire assessment was low. Similar observations were reported by Nugent et al. in a study evaluating somatic pain in a group of opioid users; the authors concluded that standardized pain assessments during care are moderately correlated with research-administered pain intensity measures and could be improved by incorporating more robust measures of pain-related functioning, mental health, and quality of life in health (25). Despite the interesting confirmed observations related to the assessment of pain intensity, the present study has certain limitations. In our research, no adjustment was made for confounding variables affecting pain experiences, such as emotional state. Although, in the overall study, anxiety as a trait and as a state was assessed, these data were not presented in this material (no association was found between pain and the severity of anxiety as a trait or as a state). Cognitive functions of the participants were also not assessed in detail, although the inclusion criteria specified the level of communication and ability to cooperate. Multivariable models were likewise not used to control for other variables influencing pain. During the course of the study, it was observed that individuals living alone, without support or assistance, exhibited stronger emotional reactions compared to the rest of the group. These variables may affect the reliability of the results. Although medical history regarding analgesic use was obtained and pain sensations were assessed, such parameters may be insufficient.

One of the most extensively studied applications of VR technology in alleviating pain and anxiety during medical interventions and rehabilitation processes has been research involving burn patients. In a randomized controlled trial, Das et al. demonstrated the superior effectiveness of analgesia combined with VR in reducing pain and distress during procedures in burn-injured children aged 5 to 18 years compared to standard analgesia alone (26). The effectiveness of VR technology in pediatric burn care has also been confirmed in other studies by Hoffman et al. He investigated the use of VR during burn wound cleaning procedures conducted in a water environment and during physiotherapy sessions in burn patients, confirming that VR effectively reduces pain by engaging patients in play, as well as resulting in lower pain ratings and increased range of motion during physiotherapy when VR was used in addition to pharmacological anesthesia (27–29). Sharar et al. reported findings from three studies confirming reductions in pain intensity, unpleasantness, and the amount of time spent thinking about pain symptoms in patients who received VR combined with standard anesthesia (30). Similar results in groups of burn patients undergoing physiotherapy/rehabilitation were obtained by Carrougher et al. (31). In our study, VR was implemented with interesting effects in a group of patients with chronic wounds. This is one of the few recent studies conducted in Poland demonstrating the potential of VR use in outpatient care. Existing evidence of VR’s ability to reduce pain and anxiety during medical and rehabilitation procedures has broadened research interests toward the use of VR hypnosis (Virtual Reality Hypnosis, VRH), which has been shown to lower pain and anxiety levels (32–34). Our own results, obtained using the NRS and MPQ scales, justify the conclusion that the use of VR during wound care procedures reduces perceived pain intensity by distracting patients. However, assessments obtained via the individual tools are not consistent. This observation warrants further investigation in future studies, with particular attention to evaluations using the simple numerical scale (which tends to overestimate pain) and the more comprehensive quantitative-qualitative tool, the MPQ. Our study highlighted that qualitative assessment of pain intensity in scientific contexts is more desirable, as it precisely identifies symptoms and sensations rather than merely measuring pain intensity alone. In summarizing the conducted project, attention was also drawn to the costs associated with the procurement and maintenance of VR equipment in medical facilities providing inpatient, outpatient, and home care services. The purchase and upkeep of the equipment are commensurate with the potential benefits arising from increased patient satisfaction, which results from pain reduction through distraction and the alleviation of negative emotions related to observing the removal of dressings, wound cleansing procedures, including the sight of devitalized, necrotic tissue, pus, and blood. However, for VR-based procedures to become widespread and standard practice in Poland, public funding would be necessary. The broad implementation of this innovation would require further studies focusing on cost-effectiveness and feasibility analyses. It should be noted that VR can also be utilized for other ambulatory diagnostic procedures, especially in pediatric populations and individuals with heightened sensitivity, such as blood sampling for biochemical tests or other interventions where exposure to bodily excretions and secretions may induce anxiety and exacerbate negative emotional experiences.

Previous research on the use of VR in the treatment of vascular wounds has been limited in scale and often focused on hospital settings. Therefore, there is an urgent need to deepen knowledge regarding the potential application of VR during debridement procedures conducted outside the hospital, where organizational challenges, personnel shortages, and technical limitations affect the quality of care. This study addresses that knowledge gap by analyzing the effectiveness of VR in alleviating pain during the cleansing of vascular wounds in outpatient care settings.

5 Conclusion

The increase in pain experiences during procedures involving manipulation of damaged tissues and wound debridement is a well-known phenomenon. This study confirmed a reduction in perceived pain levels during the use of VR goggles, which occurred due to distraction of attention and limitation of the unpleasant view of devitalized tissues, pus, and blood. Pain sensation and intensity assessments differ depending on the selected evaluation tools; therefore, a combined quantitative and qualitative assessment of pain sensations and intensity is recommended to accurately indicate the usefulness of innovative tools in clinical practice. The use of VR as an adjunct strategy to reduce pain intensity and pain sensations during the management of hard-to-heal wounds may be recommended in healthcare; however, it requires further observational studies in various clinical situations.

6 Study limitations

A limitation of the study was the exclusion of patients whose pain level during their first visit to the wound care clinic, assessed using the NRS scale, exceeded 4 points. This criterion was adopted to prevent escalation of pain experiences during wound cleansing. Patients receiving strong opioid medications were also excluded due to the risk of data distortion, as well as individuals who recorded extreme pain intensity ratings during the procedure. A limitation of the study was the lack of control and monitoring of the medications regularly taken by patients, including analgesics, which might have influenced the level of perceived pain immediately before the intervention and after wound cleansing. Another limitation was the absence of physiological marker recordings, such as heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate. Another limitation was data collection at only two time points—10 min before the wound care intervention and during the wound care procedure in groups A and B—without assessments conducted within 10 min after the intervention or at later times (e.g., 2 h post-intervention), which could have revealed associations with the persistence or normalization of patient pain symptoms. Future studies should consider analyzing the influence of mental, emotional, and social factors on pain experiences during wound cleansing interventions with and without VR. The study was conducted solely in outpatient settings (wound care clinic); no assessments were performed in home environments during chronic wound care. Considering the home environment in future research would provide valuable insights.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the study was conducted in accordance with the Decla-ration of Helsinki, and approved by the Bioethics Committee at the University of Rzeszów (RES-OLUTION no. 054/12/2024 dated 20 December 2024). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

JP-M: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. DB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. AS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. AK: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JB: Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Elżbieta Lesińska for her support in preparing the database and statistical analysis, and Marta Wójcik-Czerwińska for the translation of the text.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Garrett B Taverner T Masinde W . A rapid evidence assessment of immersive virtual reality as an adjunct therapy in acute pain management in clinical practice. Clin J Pain. (2018) 34:691–701.

2.

Abbas A Bashir S Sarwar MF Malik HA . What is virtual reality? A healthcare-focused systematic review of definitions. Health Policy Technol. (2023) 12:100741. doi: 10.1016/j.hlpt.2023.100741

3.

Strohal R Dissemond J Jordan O'Brien J Piaggesi A Rimdeika R Young T et al . EWMA document: debridement. An updated overview and clarification of the principle role of debridement. J Wound Care. (2013) 22:5. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2013.22.Sup1.S1

4.

Sibbald RG Elliott JA Persaud-Jaimangal R Goodman L Armstrong DG Harley C et al . Wound bed preparation 2021. Adv Skin Wound Care. (2021) 34:183–95. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000733724.87630.d6

5.

Rajhathy EM Meer JV Valenzano T Laing LE Woo KY Beeckman D et al . Wound irrigation versus swabbing technique for cleansing noninfected chronic wounds: a systematic review of differences in bleeding, pain, infection, exudate, and necrotic tissue. J Tissue Viability. (2023) 32:136–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jtv.2022.11.002

6.

Skórka M Bazaliński D Gajdek M Szymańska P Strzałko B . Debridement of hard-to-heel wounds provided in the home-care setting. Practical and legal possibilities. Lecz Ran. (2022) 19:84–93. doi: 10.5114/lr.2022.120199

7.

Atkin L Bućko Z Conde Montero E Cutting K Moffatt C Probst A et al . Implementing TIMERS: the race against hard-to-heal wounds. J Wound Care. (2019) 23:S1–S50. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2019.28.Sup3a.S1

8.

Murphy C Atkin L Swanson T Tachi M Tan YK Vega de Ceniga M et al . International consensus document. Defying hard-to-heal wounds with an early antibiofilm intervention strategy: wound hygiene. J Wound Care. (2020) 29:S1–S26. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2020.29.Sup3b.S1

9.

Huang Q Lin J Han R Peng C Huang A . Using virtual reality exposure therapy in pain management: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Value Health. (2022) 25:288–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2021.04.1285

10.

Bazaliński D Wójcik A Pytlak K Bryła J Kąkol E Majka D et al . The use of virtual reality as a non-pharmacological approach for pain reduction during the debridement and dressing of hard-to-heal wounds. J Clin Med. (2025) 14:4229. doi: 10.3390/jcm14124229

11.

Mallari B Spaeth EK Goh H Boyd BS . Virtual reality as an analgesic for acute and chronic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Res. (2019) 12:2053–85. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S200498

12.

Tashjian VC Mosadeghi S Howard AR . Virtual reality for management of pain in hospitalized patients: results of a controlled trial. JMIR Ment Health. (2018) 5:e9

13.

Indovina P Barone D Gallo L Chirico A De Pietro G Giordano A . Virtual reality as a distraction intervention to relieve pain and distress during medical procedures: a comprehensive literature review. Clin J Pain. (2018) 34:858–77. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000599

14.

Chan EA Wong F Cheung MYE Lee JMH . Using narrative inquiry and ethnography to understand the impact of VR distraction for pain management in the home setting. J Clin Nurs. (2020) 29:4194–203.

15.

World Medical Association . (2024). Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Available online at: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ (Accessed June 15, 2025).

16.

Melzack R . The mcgill pain questionnaire: major properties scoring methods. Pain. (1975) 1:277–99. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(75)90044-5

17.

Kołłątaj M Wordliczek J Dobrogowski J . The McGill pain questionnaire (MPQ) and the shortened version of the McGill pain questionnaire. Ból [Pain]. (2013) 14:10–3.

18.

Raja SN Carr DB Cohen M Finnerup NB Flor H Gibson S et al . The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain. (2020) 161:1976–82. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001939

19.

Cieślik B Mazurek J Rutkowski S Kiper P Turolla A Szczepańska-Gieracha J . Virtual reality in psychiatric disorders: a systematic review of reviews. Complement Ther Med. (2020) 52:102480. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2020.102480

20.

Jordan M Richardson EJ . Effects of virtual walking treatment on spinal cord injury-related neuropathic pain: pilot results and trends related to location of pain and at-level neuronal hypersensitivity. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. (2016) 95:390–6.

21.

Rodriguez ST Jimenez RT Wang EY Zuniga-Hernandez M Titzler J Jackson C et al . Virtual reality improves pain threshold and recall in healthy adults: a randomized, crossover study. J Clin Anesth. (2025) 103:111816. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2025.111816

22.

Melzack R Wall PD . Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science. (1965) 150:971–9. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3699.971

23.

McCaul KD Malott JM . Distraction and coping with pain. Psychol Bull. (1984) 95:516–33. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.516

24.

Wickens CD . Multiple resources and mental workload. Hum Factors. (2008) 50:449–55. doi: 10.1518/001872008X288394

25.

Nugent SM Lovejoy TI Shull S Dobscha SK Morasco BJ . Associations of pain numeric rating scale scores collected during usual care with research administered patient reported pain outcomes. Pain Med. (2021) 22:2235–41. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnab110

26.

Das DA Grimmer KA Sparon AL McRae SE Thomas BH . The efficacy of playing a virtual reality game in modulating pain for children with acute burn injuries: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. (2025) 5:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-5-1

27.

Hoffman HG Patterson DR Seibel E Soltani M Jewett-Leahy L Sharar SR . Virtual reality pain control during burn wound debridement in the hydrotank. Clin J Pain. (2008) 24:299–304. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318164d2cc

28.

Hoffman HG Patterson DR Carrougher CJ . Use of virtual reality for adjunctive treatment of adult burn pain during physical therapy. Clin J Pain. (2000) 16:244–50. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200009000-00010

29.

Hoffman HG Patterson DR Carrougher CJ Sharar SR . Effectiveness of virtual reality-based pain control with multiple treatments. Clin J Pain. (2001) 17:229–35. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200109000-00007

30.

Sharara SR Carrougher GJ Nakamura D Hoffman HG Blough DK Patterson DR . Factors influencing the efficacy of virtual reality distraction analgesia during postburn physical therapy: preliminary results from 3 ongoing studies. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2007) 88:S43–9. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.09.004

31.

Carrougher GJ Hoffman HG Nakamura D Lezotte D Soltani M Leahy L et al . The effect of virtual reality on pain and range of motion in adults with burn injuries. J Burn Care Res. (2009) 30:785–91. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181b485d3

32.

Patterson DR Hoffman HG Palacios AG Jensen MJ . Analgesic effects of posthypnotic suggestions and virtual reality distraction on thermal pain. J Abnorm Psychol. (2006) 115:834–41. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.834

33.

Oneal BJ Patterson DR Soltani M Teeley A Jensen MO . Virtual reality hypnosis in the treatment of chronic neuropathic pain: a case report. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. (2008) 56:451–61. doi: 10.1080/00207140802255534

34.

Konstantatos AH Angliss M Costello V Cleland H Stafrace S . Predicting the effectiveness of virtual reality relaxation on pain and anxiety when added to PCA morphine in patients having burns dressings changes. Burns. (2009) 35:491–9. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2008.08.017

Summary

Keywords

wound debridement, virtual reality, pain monitoring, nurse, wound cleaning, outpatient care

Citation

Przybek-Mita J, Bazaliński D, Surmacz A, Kołodziej A and Bryła J (2025) Monitoring pain during use of virtual reality in debridement procedures of vascular wounds in outpatient care settings. Front. Med. 12:1658190. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1658190

Received

02 July 2025

Accepted

21 October 2025

Published

03 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Rahul Kashyap, WellSpan Health, United States

Reviewed by

Marcos Brioschi, University of São Paulo, Brazil

Saurabh Sharma, Sawai Man Singh Hospital, India

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Przybek-Mita, Bazaliński, Surmacz, Kołodziej and Bryła.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Joanna Przybek-Mita, joprzybek@ur.edu.pl

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.