Abstract

Introduction:

Hand–foot–skin reaction (HFSR) is one of the major mucocutaneous adverse events of multi-kinase inhibitors (MKIs). Its overall incidence is 35.0%. It negatively impacts the quality of life of the patient and compliance with chemotherapy. Present management of HFSR is largely anecdotal, and the common treatment is dose regulation or discontinuation of chemotherapy. In Ayurveda, the clinical presentation of HFSR may be understood as pitta rakta-pradhana agantuja vraṇa in hasta and pada caused by MKIs. The present study aimed to evaluate the Ayurveda treatment protocol as an add-on to the standard of care.

Methodology:

This is a double-arm-controlled interventional study with a quasi-experimental design, registered in the Clinical Trial Registry of India under CTRI/2022/03/040929, with 22 participants from the Medical Oncology Department and Integrative Medicine, Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, Kochi. The study group received an add-on treatment to the standard of care (SOC). This included Yasṭimadhu Kashaya pariseka (from days 1 to 30), followed by Satadhauta ghrita Lepana (from days 6 to 30) twice daily immediately after pariseka. A gap of 1 h was maintained between the Ayurveda treatment and SOC as prescribed by the oncologist.

Results and conclusion:

The study group demonstrated a significant reduction in pain (VAS) and improvement in quality of life (HF-QoL) compared to the control group. Yasṭimadhu is vrana sandhaneeya, varnya, daha prashamana, shothahara, and shonitasthapana. Ghrita is Vata pittahara, sheeta veerya, and dahaprashamana, and it facilitates ropana. HF-QoL improved due to effective management of symptoms. The pilot study suggested that an integrated therapy is feasible in HFSR patients, which can possibly support improving the quality of life for cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Clinical trial registration:

CTRI/2022/03/040929, https://www.ctri.nic.in/Clinicaltrials/pmaindet2.php?EncHid=NjMwMTE=&Enc=&userName=.

1 Introduction

Multi-kinase inhibitors (MKIs) are targeted chemotherapy agents that have proven to be clinically effective in the treatment of a wide range of cancers (1). However, they are associated with many adverse events, and the major mucocutaneous adverse event of MKIs is the hand–foot–skin reaction (HFSR) (2). HFSR affects the skin on the palmar and plantar surfaces. Beginning as a mild skin reaction, the condition can quickly progress into a painful, debilitating condition. It affects the person’s ability to perform activities and has an undesirable influence on the quality of life of the patient and also compliance with cancer therapy (2). Present management of HFSR is largely anecdotal, and the most common method of treatment for grade 2 and grade 3 HFSR is dose regulation or discontinuation of chemotherapy (3). The cessation of chemotherapy because of unbearable symptoms of HFSR could increase the mortality rate of cancer patients. While analyzing the effect of MKIs on the body, they seem to possess guna similar to those described in Ayurveda treatises as visa guna (attributes of poison), such as tiksna (sharply acting), asu (rapid acting), vyavayi (which pervades the whole body before getting digested), suksma (subtleness), usna (hot), and ruksa (dryness) (4). These attributes cause pitta rakta pradhana tridosha dusti (ulcer with clinical presentation of three doshas with predominance of pitta and rakta) in the body (5). In Ayurveda, the clinical presentation of HFSR may be understood as pitta rakta pradhana agantuja vrana (exogenous ulcer) in hasta and pada (hand and foot) caused due to tiksnadi gunas (attributes of poison, such as sharply acting) of MKIs. The first line of management of agantuja vrana is pittavat sita kriya (6) (medicines and therapies that are cold, intended to pacify pitta). In order to manage pitta rakta pradhana dusti (clinical presentation of impairment of rakta), bahya prayogas (topical applications) that are sita (cold) in guna are indicated (7). Evidences suggest that Glycyrrhiza glabra (Yashtimadhu) and ghee have anti-inflammatory activity and wound-healing potential (8). Wayal et al. reported that the process of satadhauta or washing ghee with water 100 times, increases the moisture content in ghee, which may be useful for skin hydration and cooling while used topically (9). The present study aims to evaluate the feasibility of an Ayurveda treatment protocol containing pariseka or wash, with Yastimadhu (Glycyrrhiza glabra) Kashaya, followed by lepana (anointment) with satadhauta ghrita as add-on therapy in reducing the symptoms of HFSR due to MKIs.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design and ethical considerations

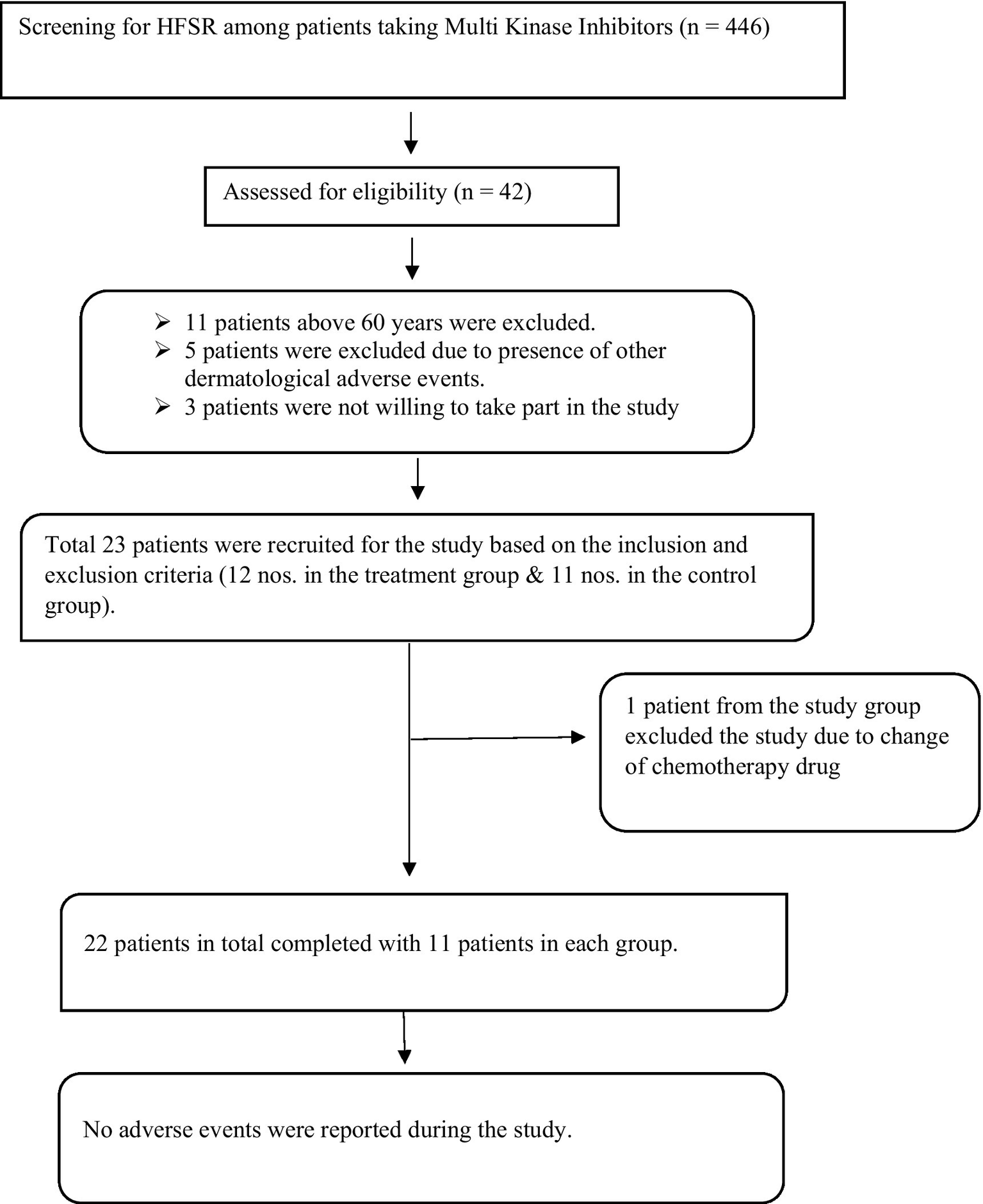

This is a double-arm, interventional study with a control. Participants were selected from the OPD and IPD of Medical Oncology and the Department of Integrative Medicine, Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, Kochi. The trial was conducted between March 2022 and September 2022, and a diagrammatic presentation of the patient flow is provided (Figure 1). The Clinical Research Act (enacted 14 April 2017) and the amended October 2013 Declaration of Helsinki have been followed in this investigation. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences under IEC-AIMS-2021-AYUR-068A. Furthermore, all relevant regional, national, and international laws have been followed. This study is registered in the Clinical Trial Registry of India under CTRI/2022/03/040929.

Figure 1

Methodology.

2.2 Participant selection

Participants who had undergone chemotherapy with MKIs and were consequently diagnosed with HFSR by a medical oncologist, based on CTCAE v5.0 criteria, were screened and selected based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.2.1 Inclusion criteria

Age: 18 years–60 years.

Diagnosed with a malignant tumor with pathological or cytological findings as evidence.

An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ≤3.

Treatment with MKIs and consequent occurrence of hand–foot–skin reaction of any grade.

Life expectancy >3 months.

Those who are willing to participate in this study and have signed the informed consent forms.

To confirm the presence of HFSR in patients, the CTCAE v5.0 grading system was utilized (10). Although there is no specific grading for HFSR within this system, it is noted that the grading criteria for HFS (palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia) are applicable and can be used equivalently as follows:

2.2.1.1 Grade 1

Minimal skin changes or dermatitis (e.g., erythema, edema, or hyperkeratosis) without pain.

2.2.1.2 Grade 2

Skin changes (e.g., peeling, blisters, bleeding, fissures, edema, or hyperkeratosis) with pain, limiting instrumental ADL.

2.2.1.3 Grade 3

Severe skin changes (e.g., peeling, blisters, bleeding, fissures, edema, or hyperkeratosis) with pain, limiting self-care ADL.

2.2.2 Exclusion criteria

Dermatological toxicities were not induced by MKIs.

Concurrent acne vulgaris, eczema, psoriasis, and other skin diseases.

Abnormal cognition and speech causing difficulty with comprehension, expression, and obtaining informed consent.

2.3 Enrolment and intervention

The eligible participants were explained regarding SOC and the add-on traditional therapies and further left to his/her choice to select either the SOC alone or the same with add-on traditional therapies, including pariseka and lepa. Henceforth, they were assigned to either the control or study group as per their choice.

In both the control and study groups, the standard of care (SOC) was prescribed as per the respective grade of HFSR. In grade 1 HFSR, the primary interventions include the application of moisturizing creams and topical keratolytics such as urea and salicylic acid creams. Additionally, cushioning of the affected areas is recommended, and no dose reduction of chemotherapy. For grade 2 HFSR, the same symptomatic measures as in grade 1 are used, and the treatment is enhanced by the application of potent corticosteroids and analgesics to inflammatory lesions. In this grade, a dose reduction or interruption of chemotherapy may be considered. In cases of grade 3 HFSR, the interventions from grade 2 are continued, with the addition of antiseptic treatment for blisters and erosions. Clinical management may include dose reduction, re-escalation, or even the interruption or discontinuation of chemotherapy, depending on clinical judgment and patient preferences (11, 12).

The study group received an add-on treatment to the SOC. This included pariseka with Yastimadhu Kashaya (1 liter at room temperature for each administration). The participants had to prepare kashaya for pariseka as per the instructions given. A measure of 62.5 g of coarse Yastimadhu Churna (powder) had to be boiled in 4 liters of water, reduced to 2 liters, and left to cool to room temperature. It was then divided into two equal portions to be used in the morning and evening for pariseka, or washed over the affected area for 15 min twice daily from days 1 to 30, followed by lepana with shatadhauta ghrita (QS) twice daily immediately after pariseka from days 6 to 30. An interval of 1 h was maintained between the Ayurveda treatment and SOC as prescribed by an oncologist.

2.4 Outcome measures

The principal objective was the evaluation of alterations in HFSR grades from baseline to the 30-day mark, using the CTCAE v5.0 criteria; evaluation of variations in pain severity, gauged through the VAS score; and analysis of quality of life utilizing the HF-QoL questionnaire (13).

2.5 Sample size

Being an exploratory study using non-probability sampling, a minimum sample size of 30 was planned for the 6-month trial period. However, due to the constraints of the recruitment timeline, only 23 participants were ultimately enrolled in the study.

2.6 Trial drugs

Both Satadhauta ghrita (Batch No.: #8281) and Yashtimadhu Churna were procured from A V Oushadhasala, Thattarkonam, Kollam, Kerala – 691005, a GMP-certified company. The drugs were stored in airtight polythene containers arranged in almirahs.

2.7 Statistical analyses

The effect of the intervention within the group was assessed using a paired t-test, while the between-group effect was assessed using an independent t-test. Descriptive statistics were used for demographic variable analysis using IBM SPSS version 20. The significance level was set at a p-value of <0.05, considered statistically significant, and a p-value of <0.001 was regarded as highly significant. Results with a p-value of >0.05 were deemed insignificant.

3 Results

The patients who were undergoing chemotherapy via MKIs were screened based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Informed consent was obtained from 23 patients. During the study period, one participant was excluded from the study. She was a known case of clear cell carcinoma with metastasis. She was under treatment with pazopanib and presented with grade 2 HFSR. She followed the Ayurveda treatment protocol till day 13. After the 13th day, she discontinued the treatment for HFSR because her chemotherapy drug was changed to immunotherapy due to the progression of cancer (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Patients’ inflow chart.

3.1 Patient demographics and clinical characteristics of the HFSR population

The demographic data and clinical characteristics of the population experiencing HFSR are summarized in Table 1. Both the study and control groups were tested for homogeneity and were found to be homogeneous with respect to baseline data. The mean age of patients was 55.9 years in the treatment group and 50.8 years in the control group. In both groups, the female population exceeded the male population by 9%.

Table 1

| Characteristics | Treatment group | Control group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 55.9 (±2.7) | 50.8 (±9.4) | |

| 35–40 | 0 (0%) | 2 (18.2%) | |

| 40–45 | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) | |

| 50–55 | 5 (45.5%) | 3 (27.3%) | |

| 55–60 | 6 (54.5%) | 5 (45.4%) | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 6 (54.5%) | 6 (54.5%) | |

| Male | 5 (45.5%) | 5 (45.5%) | |

| Site of cancer | |||

| Appendix | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Colon | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) | |

| Kidney | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (9.1%) | |

| Liver | 4 (36.3%) | 5 (45.4%) | |

| Lung | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) | |

| Ovary | 2 (18.2%) | 1 (9.1%) | |

| Rectum | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Soft tissue | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) | |

| Thyroid | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) | |

| Urinary bladder | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Uterus | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Chemotherapy drug | |||

| Gefitinib | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) | |

| Lenvatinib | 2 (18.2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Pazopanib | 4 (36.3%) | 2 (18.2%) | |

| Regorafenib | 3 (27.3%) | 2 (18.2%) | |

| Sorafenib | 2 (18.2%) | 6 (54.5%) | |

| HFSR on hands | 3 (27.3%) | 1 (9.1%) | |

| HFSR on foot | 10 (90.9%) | 10 (90.9%) | |

| HFSR grade | 1.9 (±0.09) | 1.8 (±0.12) | p = 0.56 |

| Quality of life | 40 (±22.6) | 26.6 (±18.8) | p = 0.15 |

| VAS scale | 6.7 (±2.7) | 5.8 (±3.2) | p = 0.48 |

Baseline data.

The primary site of cancer was the liver, i.e., 45.4% in the control group and 36.3% in the treatment group. A smaller proportion of participants in each group were diagnosed with cancer at other sites, including the appendix, colon, kidney, lung, rectum, soft tissue, thyroid, urinary bladder, and uterus. It is observed that half of the participants in the treatment group and 18% in the control group received sorafenib. Additionally, 36.3% of the treatment group and 18% of the control group received pazopanib. Treatment with regorafenib was observed in 27% of the treatment group and 18% of the control group, while only one participant in the control group received gefitinib. HFSR predominantly occurred on the feet in the majority of participants in both groups. The mean HFSR grade before treatment was 1.9 (±0.09) in the treatment group and 1.8 (±0.12) in the control group. The mean Hand-Foot Quality of Life (HFQoL) score prior to treatment was 40 (±22.6) in the treatment group, compared to 26.6 (±18.8) in the control group. Furthermore, the mean visual analog scale (VAS) score before treatment was 6.7 (±2.7) in the treatment group, whereas it was 3.2 (±3.2) in the control group.

3.2 Effect on the grade of HFSR

The mean grade of HFSR according to CTCAE v5.0 in the control group before intervention was 1.82 (±0.405), which remained the same after treatment. There was no progression of HFSR to a higher grade.

The mean grade of HFSR according to CTCAE v5.0 in the treatment group before intervention was 1.91 (±0.302), which remained the same after treatment. There was no progression of HFSR to a higher grade.

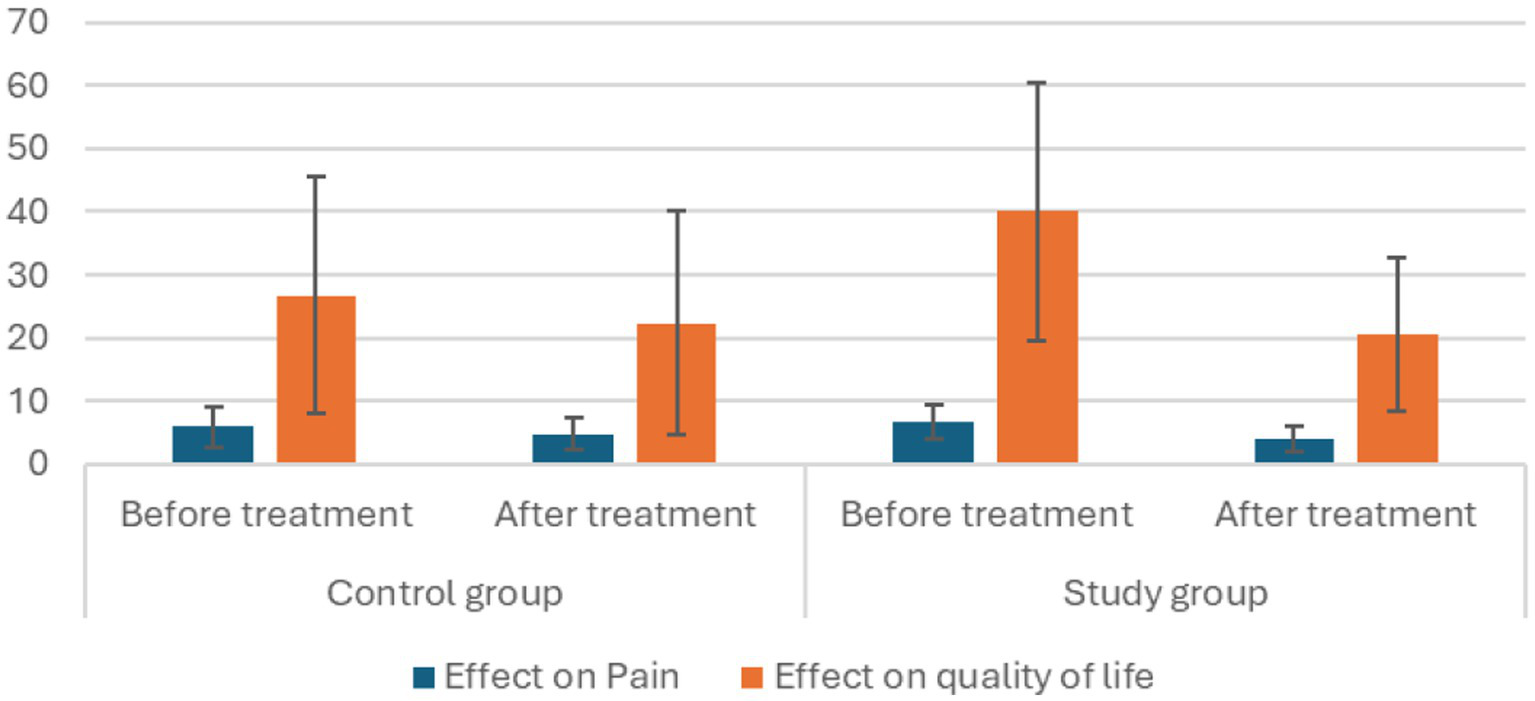

3.3 Effect on pain

In the control group, the mean VAS score before the intervention was 5.8 (± 3.2). After the intervention, it decreased to 4.7 (±2.6), with a significant reduction of 1.09 points. The t-value for this change was 4.4, with a p-value of 0.001, indicating statistical significance (Table 2; Figure 3).

Table 2

| Statistical parameters | Effect on pain | Effect on QOL | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | Treatment group | Control group | Treatment group | ||||||

| B.T. | A.T. | B.T. | A.T. | B.T. | A.T. | B.T. | A.T. | ||

| Total Number | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | |

| Mean | 5.8 | 4.7 | 6.7 | 4.0 | 26.64 | 22.36 | 40.0 | 22.6 | |

| Standard deviation | 3.2 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 18.8 | 17.7 | 20.5 | 12.3 | |

| BT-AT Mean | 1.09 | 2.7 | 4.3 | 19.5 | |||||

| Standard deviation | o.8 | 1.6 | 3.9 | 12.3 | |||||

| Standard error mean | 0.25 | 0.49 | 1.2 | 3.7 | |||||

| 95% confidence interval | L | 0.532 | 1.640 | 1.7 | 11.3 | ||||

| U | 1.649 | 3.814 | 6.9 | 27.8 | |||||

| T-value | 4.4 | 5.6 | 3.7 | 5.3 | |||||

| P-value | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.000 | |||||

Effect of therapy on pain and QOL within the groups.

QOL, quality of life; BT, before treatment; AT, after treatment; L, lower; U, upper.

Figure 3

Effect of therapy on pain and QoL within the groups.

In the treatment group, the mean VAS score before the intervention was 6.7 (±2.7), which decreased to 4.0 (±2.1) post-intervention. This represents a significant reduction of 2.7 points, with a t-value of 5.6 and a p-value of <0.001, showing a highly significant improvement (Table 2; Figure 3).

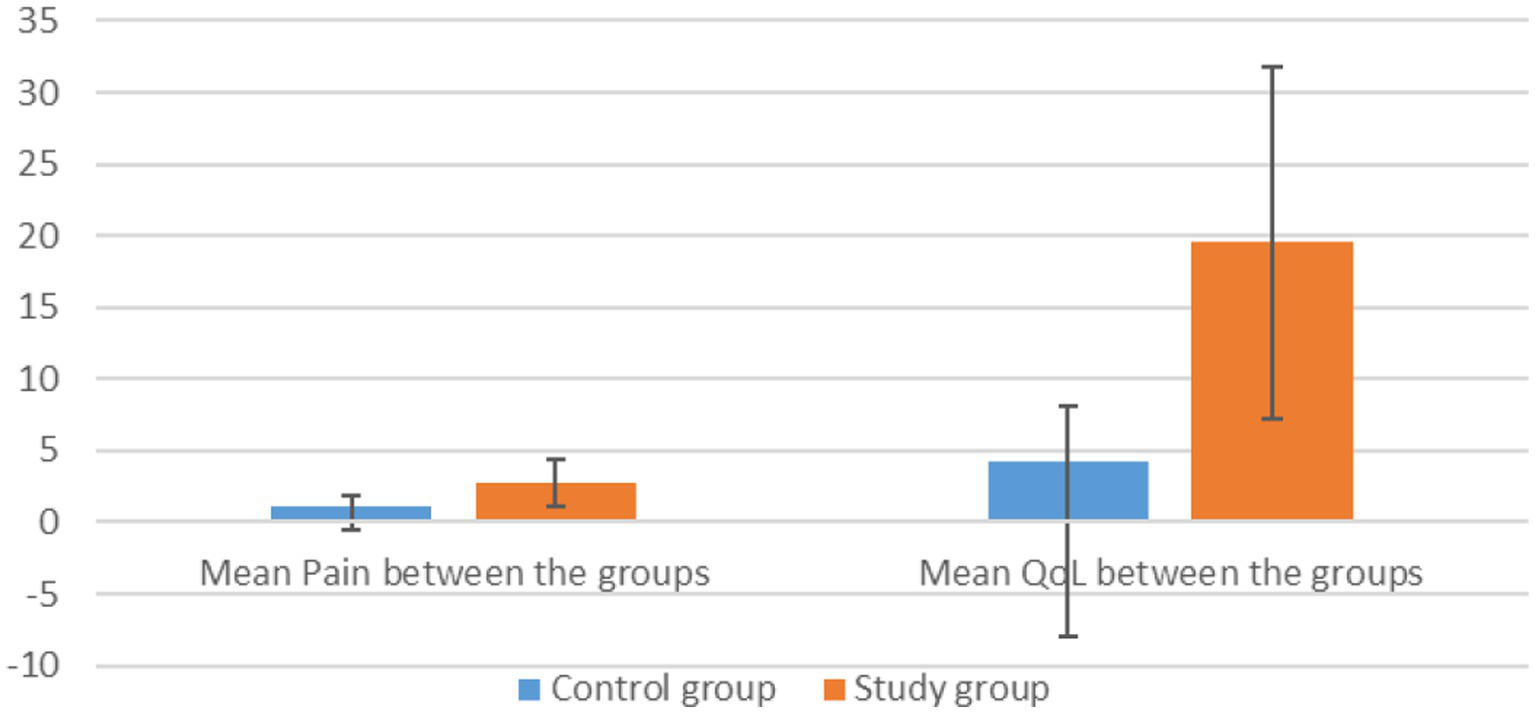

Comparing the mean differences in pain reduction between the treatment and control groups, a significant difference is noted (Figure 4). The treatment group showed a greater reduction in pain (mean difference = 2.7) compared to the control group (mean difference = 1.09). The t-test results indicate that this difference is statistically significant, with a p-value of 0.007 under the assumption of equal variances and 0.009 when variances are not assumed (Tables 3, 4). These results suggest that the treatment was more effective than the control intervention in reducing pain.

Figure 4

Effect of therapy on pain and QoL between the groups.

Table 3

| Statistical parameters | Effect on pain | Effect on QOL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | Treatment group | Control group | Treatment group | |

| Total number | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Mean | 1.09 | 2.73 | 4.27 | 19.55 |

| Standard deviation | 0.831 | 1.618 | 3.875 | 12.275 |

| Standard error mean | 0.251 | 0.488 | 1.168 | 3.701 |

Effect of therapy on pain and QOL between the groups.

Table 4

| Statistical parameters | Levene’s test for equality of variances | t-test for equality of means | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | ||||||||||

| F | Sig. | t | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | Mean difference | Std. Error difference | Lower | Upper | ||

| Mean difference pain | Equal variances assumed | 2.668 | 0.118 | 2.983 | 20 | 0.007 | 1.636 | 0.548 | 0.492 | 2.780 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 2.983 | 14.934 | 0.009 | 1.636 | 0.548 | 0.467 | 2.806 | |||

| Mean difference HFQoL | Equal variances assumed | 15.138 | 0.001 | 3.935 | 20 | 0.001 | 15.273 | 3.881 | 7.177 | 23.369 |

| Equal variances not assumed | 3.935 | 11.974 | 0.002 | 15.273 | 3.881 | 6.815 | 23.731 | |||

Independent sample test.

3.4 Effect on quality of life

In the control group, the mean HFQoL score before intervention was 26.64 (±18.8). Following intervention, it decreased to 22.36 (±17.7), indicating a significant reduction of 4.3 points. This suggested an improvement in the quality of life for individuals in the control group. The t-value for this change was 3.7, with a p-value of 0.004 (Table 2; Figure 3).

In the treatment group, the mean HFQoL score before intervention was 40 (±22.6). After intervention, it significantly decreased to 20.5 (±12.4), showing a substantial reduction of 19.5 points. This marked an improvement in the quality of life of individuals in the intervention group. The t-value for this change was 5.3, with a p-value of less than 0.001 (Table 2; Figure 3).

The treatment group demonstrated a significantly greater improvement in quality of life compared to the control group, with a mean difference of 15.273 points on the HFQoL score (Figure 4). This difference is statistically significant, with a p-value of less than 0.01, indicating a high level of significance in the observed improvement (Tables 3, 4).

4 Discussion

The treatment group demonstrated a significant relief of 40%, calculated based on the VAS Score. A significant mean difference in pain between the two groups was noted, with the treatment group experiencing better pain relief than the control group.

The inflammation associated with HFSR leads to erythema, swelling, hyperkeratotic plaques, blistering, ulceration, bleeding, and pain (14). Pain linked to inflammation typically resolves as the underlying pathology heals. Various studies have investigated the anti-inflammatory and wound-healing properties of Glycyrrhiza glabra (GG) and ghee.

Siriwattanasatorn et al. (15) reported that ethanolic extracts of GG could lessen the generation of superoxide anion, curtail nitric oxide production, enhance fibroblast proliferation, and hasten wound closure. The anti-inflammatory effects of glabridin, a compound in GG, have been demonstrated in vitro through its inhibition of superoxide anion production and cyclooxygenase activities (16). Glycyrrhizin acid has also been shown to reduce erythema, edema, and itching scores through topical application in a double-blind clinical trial (16). According to Castangia et al. (17), the high antioxidant content in the topical application of liquorice extract formulations helps counteract oxidative stress damage and maintain skin homeostasis. An experimental study on excision wounds in adult Wistar albino rats explored the wound-healing potential of aqueous extracts of GG and cow’s ghee. The wound-healing efficacy was assessed using immunohistochemical (IHC) parameters, focusing on the inflammatory response, assessed by the level of interleukin-1β (IL1β) and tissue remodeling through the activity of myofibroblasts (8).

Regarding the effect on myofibroblasts, GG exhibited anti-inflammatory and skin regeneration activities. Proliferation of dermal fibroblasts was observed. The process of dermal fibrosis was found to decelerate significantly due to glycyrrhizin, by its potential to reduce collagen content and the number of myofibroblasts (8). GG-treated wound healed better, pointing to optimal myofibroblast activity. It amplified myofibroblast activity during the early phases of healing, helping with contraction and wound closure. Fibrosis and scar formation were further absent in the process of wound healing as GG reduced myofibroblast activity, thereby decreasing excessive collagen deposition at the end of the healing phase.

Saturated fatty acids and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), such as linolenic acid (n-3), linoleic acid (n-6), and oleic acid (n-9), are the major components of ghee (18). PUFAs, in addition to their structural role, can modulate cell–cell interaction and intracellular signal transduction (19). n-3 and n-6 PUFAs can stimulate epithelial cell proliferation in vitro, playing a fundamental role during healing (20). Prasad and Dorle (27) report that the topical application of ghee leads to early epithelialization, due to an increase in the volume of hydroxy proline (21). Moreover, ghee-treated wounds showed significantly higher activity of myofibroblasts initially. Later, its activity was significantly reduced. This reaffirms the role of ghee in early wound closure without scar formation (8).

The percentage of relief calculated based on the HFQoL score showed a significant relief of 48.8% in the treatment group. There was a significant difference in the mean difference in the HFQoL score between the two groups. The treatment group had a better quality of life than the control group.

The reduction in the score of HFQoL, pointing to improvement in the quality of life, is mainly due to effective management of symptoms such as reduction of swelling, redness, and pain. The relief from pain and intolerance to touch improves the participant’s ability to perform self-care and other activities, which in turn improves their psychology and social life (13).

The combined actions of the formulations and the therapy, along with the standard of care, would have contributed to an improvement in the quality of life of participants in the treatment group compared to the control group.

4.1 Probable mode of action of pariseka with Yastimadhu Kashaya

Anusna pariseka (not too hot), according to the Dvivraneeya chikitsa in the Sushruta Samhita, is a bahya prayoga (external application) indicated for Pitta-Rakta-Abhighata-Visa Nimittaja Vrana (ulcer with the clinical presentation of pitta and rakta caused due to poisoning). For Anusna pariseka, sweet (madhura) drugs, such as those of the kakolyadi gana, are prescribed in this context (22). Yastimadhu is a madhura rasa drug and is also sheeta (cooling) in nature. Acharya Charaka describes Yastimadhu as vrana sandhaneeya (wound healing), varnya (enhancing complexion), daha prashamana (alleviating burning sensation), and shonitasthapana (stopping bleeding). Madanadi Nighantu describes Yaṣṭimadhu as vrana shodhana (cleansing wounds), ropana (healing wounds), varnakrut (enhancing complexion), and rakta pitta hara (alleviating blood-related disorders). It can aid in controlling swelling (shopha) and creates an environment conducive to the healing (ropana) of wounds (vrana) (23).

4.2 Probable mode of action of lepana with shatadhauta ghrita

Lepana is described in the Vranaalepanabandhanavidhi adhyaya as pacifying doshas (dosha shamana), alleviating burning sensation (dahahara), pain-relieving (rujahara), soothing the skin (tvak prasadana), and purifying the blood (rakta prasadana) (24). Ghrita (clarified butter) is considered Vata Pittahara (pacifying Vata and Pitta doshas), sheeta in veerya (cooling in potency), and dahaprashamana (alleviating burning sensation), and it facilitates healing (ropana). Hema Sharma Dutta et al. suggest that the topical application of cow ghee on wounds can act as both samshodhana (cleansing) and samshamana (pacifying) (25). Shatadhauta ghrita is indicated in conditions such as agni visarpa, which involves pronounced pitta-rakta dushti (imbalance of Pitta and blood). In the nibandha sangraha vyakhya, it is recommended for external application in pitta-rakta predominant wounds and wounds caused by visha (poison) (22). Wayal et al. (9) suggested that the process of manufacturing shatadhauta ghrita, i.e., washing ghee in water 100 times, increases the cooling effect of the topical application (9). According to Barkin et al. (28), the nerve conduction velocity slows down on cold application to the skin, a phenomenon called cold-induced neuropraxia. This also induces an analgesic effect by reducing muscle spindle activity and causes vasoconstriction, which slows blood flow and reduces swelling (9).

5 Conclusion

Chemotherapy is a prevalent method for treating cancer, yet it presents notable advantages and disadvantages. The efficacy of traditional chemotherapy is often hindered by significant side effects such as hepatotoxicity, nausea, fatigue, hair loss, and hand-foot syndrome. Despite these limitations, chemotherapy remains a vital treatment option for various cancers, complementing surgery, radiotherapy, and targeted therapies. To address these challenges, researchers are investigating the potential for combined therapies incorporating herbal products and dietary supplements to improve outcomes and reduce adverse effects (26).

The addition of Ayurvedic interventions has demonstrated a beneficial effect on addressing the challenges associated with chemotherapy by reducing pain and enhancing the quality of life for patients. Although the Ayurveda add-on did not alter the severity of hand–foot–skin reaction (HFSR), its integration into chemotherapy regimens was beneficial in allowing patients to continue their treatment with reduced discomfort. This suggests that an integrated therapy is feasible in HFSR patients and can play a supportive role in improving the quality of life for cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.

5.1 Limitations of the study

The study duration was 30 days per participant. Within this period, there was no change in the grade of HFSR in both groups. As the study was time-bound, long-term follow-up to assess the sustained efficacy, as well as the assessment of long-term safety of the integrative approach, was not possible. The study being an exploratory one, non-probability sampling was used, and following the rules of thumb, a small sample was adopted here.

Moreover, the study included vulnerable participants. They were in pain due to HFSR and with reduced QOL. They were left to choose the treatment modality they preferred, and hence, randomization was not possible. This sort of allocation of participants would have introduced bias into the study.

The interventions included in this study were external therapies. The introduction of sham procedures as a control would add a burden to the participants, as they are less likely to contribute to alleviating the condition in those who are already in pain. Hence, the study was taken up with only conventional management in the control group and conventional management with add-on Ayurveda topical interventions in the study group. This limited the study to being blinded.

The potential confounding factors, including patient expectation and attention effect, were not addressed in the study. As an exploratory study, our primary aim was to generate preliminary evidence. We focused on variables such as pain, HFSR grade, and QoL in the sample to establish a foundation for more focused research. Moreover, controlling these complex psychological variables was beyond our scope with an exploratory design.

5.2 Suggestions

A clinical trial to assess the effectiveness of the integrative approach to the prophylactic management of HFSR is recommended. More in vivo studies are needed to analyze the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of the drugs. Additionally, a three-arm study could be conducted: one arm receiving standard care alone, another arm receiving integrative treatment, and a third arm receiving Ayurveda care alone for managing the complications of chemotherapy.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

This study involving humans was approved by IEC, Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, Kochi. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AS: Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SK: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Resources. NC: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Resources. PK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. APC is funded by Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Chapner BA Longo DL . Cancer chemotherapy and biotherapy: Principles and practice. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: WOLTERS KLUWER business (2011).

2.

Lacouture ME Robert C Atkins MB Kong HH Guitart J Garbe C . Evolving strategies for the Management of Hand-Foot Skin Reaction Associated with the multitargeted kinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib oncologist ® symptom management and supportive care. Oncologist. (2008) 8:1001–11. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0131

3.

Anderson R Jatoi A Robert C Wood LS Keating KN Lacouture ME . Search for evidence-based approaches for the prevention and palliation of hand–foot skin reaction (HFSR) caused by the multikinase inhibitors (MKIs). Oncologist. (2009) 14:291–302. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0237

4.

Trikamji VJ Kavyatheertha NR eds. Susrutha Samhita of Susruta Kalpasthana, Chapter 2, sloka number 19–20, verse 65. Choukambha Orientalia, Varanasi: Choukambha Orientalia, reprint edition (2018). 565 p.

5.

Trikamji VJ Kavyatheertha NR eds. Susrutha Samhita of Susruta Kalpasthana, Chapter 2, sloka number 20–22, verse 65. Choukambha Orientalia, Varanasi: Choukambha Orientalia, reprint edition (2018). 565 p.

6.

Susrutha Acharya , Susrutha Samhita with Nibandha Sangraha of Dalhana, edited by PV Sharma, published by Chaoukhambha Viswabharati, (2010), Chikitsasthana ¼, p 251.

7.

Susrutha Acharya , Susrutha Samhita with Nibandha Sangraha of Dalhana, edited by PV Sharma, published by Chaoukhambha Viswabharati. (2010). Chikitsasthana 1/17, p 252–253.

8.

Kotian S Bhat K Pai S Nayak J Souza A Gourisheti K et al . The role of natural medicines on wound healing: a biomechanical, histological, biochemical and molecular study. Ethiop J Health Sci. (2018) 28:759–70. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v28i6.11

9.

Wayal SR . Gurav S S Bhallatakadi ghrita: development and evaluation with reference to Murchana and Shatadhauta process. J Ayurveda Integr Med. (2020) 11:261. doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2020.05.005

10.

Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) version 5.0 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (2017).

11.

Arruebo M Vilaboa N Sáez-Gutierrez B Lambea J Tres A Valladares M et al . Assessment of the evolution of cancer treatment therapies. Cancers (Basel). (2011) 3:3279–330. doi: 10.3390/cancers3033279

12.

Unit M . Report on medical certification cause of death 2018. MCCD Rep (2018). Available online at: https://censusindia.gov.in/2011-Documents/mccd_Report1/MCCD_Report-2018.pdf (accessed 12/01/2021).

13.

Anderson RT Keating KN Doll HA Camacho F . The hand-foot skin reaction and quality of life questionnaire: an assessment tool for oncology. Oncologist. (2015) 20:831–8. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0219

14.

Chanprapaph K Rutnin S Vachiramon V . Multikinase inhibitor-induced hand–foot skin reaction: a review of clinical presentation, pathogenesis, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. (2016) 17:387–402. doi: 10.1007/s40257-016-0197-1

15.

Siriwattanasatorn M Itharat A Thongdeeying P Ooraikul B . In vitro wound healing activities of three most commonly used Thai medicinal plants and their three markers. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2020) 2020:6795383. doi: 10.1155/2020/6795383 (accessed 12/01/2021).

16.

Halder RM Richards GM . Topical agents used in the management of hyperpigmentation. Skin Therapy Lett (2004) 9:1–3. Available online at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15334278/.

17.

Castangia I Caddeo C Manca ML Casu L Latorre AC Díez-Sales O et al . Delivery of liquorice extract by liposomes and hyalurosomes to protect the skin against oxidative stress injuries. Carbohydr Polym. (2015) 134:657–63. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.08.037

18.

Mehta B. Comparative appraisal of physical, chemical, instrumental and sensory evaluation methods for monitoring oxidative deterioration of ghee (doctoral dissertation, AAU, Anand). (2014). Available at: http://krishikosh.egranth.ac.in/handle/1/5810054508

19.

Ruthig DJ Meckling-Gill KA . Both (n-3) and (n-6) fatty acids stimulate wound healing in the rat intestinal epithelial cell line, IEC-6. J Nutr. (1999) 129:1791–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.10.1791

20.

Calder PC . Polyunsaturated fatty acids, inflammation, and immunity. Lipids. (2001) 36:1007–24. doi: 10.1007/s11745-001-0812-7

21.

Karandikar YS . Comparison between the effect of cow ghee and butter on memory and lipid profile of wistar rats. J Clin Diagn Res. (2016) 10:FF11–5. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/19457.8512

22.

Susrutacharya , Susruta Samhita, with Nibandhasangraha commentary of Dalhana Acharya, edited by Priya Vrat Sharma. Chaukambha Visvabharati, Oriental Publishers & Distributors: Varanasi, India (2010), Chikitsasthana 1/17, p. 252–253.

23.

Candranandana , Madanadi Nighantu, edited by Dr. P. Visalakshy, published by Dr. P. Viasalakshy, Reader in charge, Oriental Research Institute & Manuscripts Library for the University of Kerala, Thiruvananthapuram, (2005), Prathama Gana/2. p.21

24.

Susrutacharya , Susruta Samhita, with Nibandhasangraha commentary of Dalhana acharya, edited by Priya Vrat Sharma. Chaukambha Visvabharati, Oriental Publishers: Varanasi, India (2010), Sutrasthana Chapter 18, p. 193–212.

25.

Assar DH Elhabashi N Mokhbatly A-AA Ragab AE Elbialy ZI Rizk SA et al . Wound healing potential of licorice extract in rat model: antioxidants, histopathological, immunohistochemical and gene expression evidences. Biomed Pharmacother. (2021) 143:112151. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112151

26.

Mustapha AA Ismail AE-TM Abdullahi SU Hassan ON Ugwunnaji PI Berinyuy EB . Cancer chemotherapy: a review update of the mechanisms of actions, prospects, and associated problems. Biomed Nat Appl Sci. (2021) 1:1–19. doi: 10.53858/bnas01010119

27.

Prasad V Dorle AK . Evaluation of ghee based formulation for wound healing activity. J Ethnopharmacol. (2006) 107:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.02.006

28.

Barkin RL . The pharmacology of topical analgesics. Postgrad Med. (2013) 125:7–18. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2013.1110566911

Summary

Keywords

Ayurveda, pariseka , Yastimadhu Kashaya , lepana , satadhauta ghrita , hand–foot–skin reaction

Citation

Sharma S, Somaletha A, Kartha S, Chockan N, Keechilat P and Soman D (2025) Integration of Ayurveda in managing chemotherapy-induced hand–foot–skin reaction—an exploratory quasi experimental study. Front. Med. 12:1664832. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1664832

Received

12 July 2025

Accepted

07 October 2025

Published

11 November 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Anand Dhruva, University of California, San Francisco, United States

Reviewed by

Azeem Ahmad, Central Council for Research in Ayurvedic Science, India

Prashant Gupta, University of Delhi, India

Subhajit Hazra, LIFE-To & Beyond, India

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Sharma, Somaletha, Kartha, Chockan, Keechilat and Soman.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Devipriya Soman, priya3656@gmail.com

† Present address: Aiswarya Somaletha, Raha Integrated Speciality Hospital and Ortho Neuro Rehab, Kochi, Kerala, India

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.