- 1Department of Geriatrics, The First Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu Medical College, Chengdu Medical College, Chengdu, Sichuan, China

- 2Sichuan Geriatrics Clinical Medical Research Center, Chengdu, Sichuan, China

Purpose: Frailty, a common syndrome involving multisystem impairment in older adults, is a significant preoperative concern for hip fracture patients. However, its specific link to postoperative complications remains unclear. This systematic review and meta-analysis investigates the association between preoperative frailty and adverse surgical outcomes in this geriatric population.

Methods: We comprehensively searched several databases, including China National Knowledge Infrastructure PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, (China National Knowledge Infrastructure, CNKI), Wanfang, VIP and the Cochrane Library from January 1, 2000, to September 2024. We focused on cohort studies that examine how frailty affects prognosis after hip fracture surgery in older adults. Two researchers independently screened literature, extracted data, and assessed the quality of included studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). We used Stata 15.0 to perform the meta-analyses.

Results: This review included 27 cohort studies, consisting of 19 retrospective and 8 prospective studies, involving a total of 243,264 patients. When compared to non-frail patients, frailty statistically significantly increases the risk of postoperative mortality following hip fracture. Specifically, frailty is associated within-hospital mortality [(relative risk, RR) = 3.20, 95% (confidence interval, CI): 1.93, 5.31], 30-day mortality (RR = 3.91, 95%CI: 1.89, 8.07), and 1-year mortality (RR = 1.50, 95%CI: 1.39, 1.61). Frailty also increases the rate of complications (RR = 2.81, 95%CI: 1.67, 4.74), postoperative delirium (RR = 4.44, 95%CI: 2.34, 8.41), pneumonia (RR = 4.09, 95%CI: 2.39, 7.01), and 30-day readmission (RR = 1.75, 95%CI: 1.56, 1.96).

Conclusion: Frailty increases both short-term and long-term mortality following hip fracture surgery in older patients. Additionally, frailty is associated with a higher overall rate of complications, including the 30-day readmission.

Introduction

Hip fracture, the most prevalent type of fracture among older adults, represents a major global health burden. Projections indicate that the annual number of hip fractures worldwide will reach approximately 6.26 million by 2050, with nearly half of these cases occurring in Asia, underscoring the urgent need for effective management strategies (1, 2). The consequences are severe, with 1-year postoperative mortality rates as high as 36% (3, 4). Although surgery remains the cornerstone of treatment, postoperative complications and readmission rates remain persistently high (5), highlighting a pressing need for reliable risk stratification tools.

In this context, frailty has emerged as a key prognostic factor. Defined as a state of decreased physiological reserve and increased vulnerability, frailty is highly prevalent in older populations and is known to exacerbate adverse outcomes across multiple conditions (6, 7). Its assessment is therefore critical in perioperative management. However, a major challenge lies in the absence of a definitive diagnostic gold standard, which has led to the reliance on a variety of subjective assessment tools in both clinical practice and research, such as the Frailty Phenotype (FP), Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS), and Frailty Index (FI) (8–11). Although these instruments aim to capture the multidimensional nature of frailty, heterogeneity in their components and operational definitions complicates both clinical application and evidence synthesis.

While numerous studies have suggested an association between frailty and poor postoperative outcomes in hip fracture patients (12, 13), the evidence remains inconsistent. Some studies report strong correlations, whereas others have found weak or non-significant associations (14). These discrepancies may stem from differences in the frailty assessment tools used, patient populations, or outcome measures. The 2022 systematic review by Ma et al. provided the first relatively comprehensive synthesis regarding the predictive role of frailty in hip fracture outcomes; however, limited by the number of studies available at the time, the predictive reliability for certain endpoints such as 30-day readmission remained unclear (15). Recent larger-scale clinical studies published in the past 2 years may have altered the predictive landscape for some of these outcomes.

In light of this, we conducted the present systematic review and meta-analysis. Our objectives were not only to synthesize the existing evidence on the association between preoperative frailty and postoperative outcomes in older hip fracture patients but also to perform a comparative analysis of the most commonly used frailty scales. Through this approach, this study aims to provide critical insights to help clinicians select the most appropriate frailty assessment tool, thereby ultimately contributing to improved risk prediction and personalized care for this vulnerable population.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to report this systematic review. We searched the following databases: CNKI, Wanfang, VIP, CBM, PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library on September 2024. The search employed both Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keyword searches. The search terms PubMed include “Fractures, Hip” OR “Intertrochanteric Fractures” OR “Fractures, Intertrochanteric” OR “Trochanteric Fractures” OR “Trochanteric Fractures, Femur” OR “Trochanteric Fracture, Femoral” OR “Trochanteric Fractures, Femoral” OR “Subtrochanteric Fractures” OR “Fractures, Subtrochanteric” AND “Frailties” OR “Frailness” OR “Frailty Syndrome” OR “Debility” OR “Debilities.” Using standardized Excel templates, two investigators independently retrieved data from the included studies; an independent third researcher then cross-checked the extracted data. In cases of disagreement, a third reviewer will arbitrate to reach a consensus.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for this systematic review are as follows: (1) Studies published in Chinese or English; (2) Study designs limited to cohort studies, either prospective or retrospective; (3) Study population restricted to older patients with hip fractures, specifically those aged 60 years or older; (4) Research focusing on the impact of preoperative frailty on the prognosis of hip fracture patients; (5) Studies must report at least one of the following outcomes: mortality, postoperative complications such as delirium or pneumonia, and 30-day readmission rates. The exclusion criteria are (1) Studies with incomplete datasets or lacking sufficient statistical analysis; (2) Non-empirical articles, such as commentaries, letters, editorials, conference proceedings, and basic or laboratory-based research; (3) Duplicate publications or multiple reports based on the same dataset, with preference given to the most informative and comprehensive report.

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently abstracted data from eligible studies using a pre-defined Excel template, with oversight from a third reviewer. Data abstraction included first author, publication year, country of origin, age, study design, sample size, assessment tools, and outcome measures. Mortality was our primary outcome, which included in-hospital mortality, 30-day and 1-year mortality. Secondary outcomes included total complications, postoperative delirium, pneumonia, and 30-day readmission rates.

Quality assessment

Two reviewers independently assessed the quality of the included cohort studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), with verification from a third reviewer. The NOS is a 9-point scale divided into three domains: selection of the study population (0–4 points), comparability of groups (0–2 points), and ascertainment of exposure (0–3 points). Studies with an NOS score of 7 or higher are considered to have high quality.

Statistical analysis

In this systematic review, we calculated relative risk (RR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) for mortality, 30-day readmissions, and postoperative complications. We conducted subgroup analyses to explore variations by study type and frailty assessment instrument. We assessed the heterogeneity of eligible studies using the I2 statistic. For I2 values of 50% or less, which indicate low heterogeneity, we employed a fixed-effect model in the meta-analysis. For I2 values greater than 50%, we used a random-effects model. When we encountered significant heterogeneity, we conducted sensitivity analyses by sequentially excluding each study. We also performed meta-regression to identify potential sources of heterogeneity. We used funnel plot analysis (for meta-analyses including 10 or more studies), Begg’s and Egger’s tests to evaluate the potential publication bias. In our systematic review, we considered a P < 0.05 to be statistically significant. We performed all analyses using Stata 15.0.

Results

Study screening

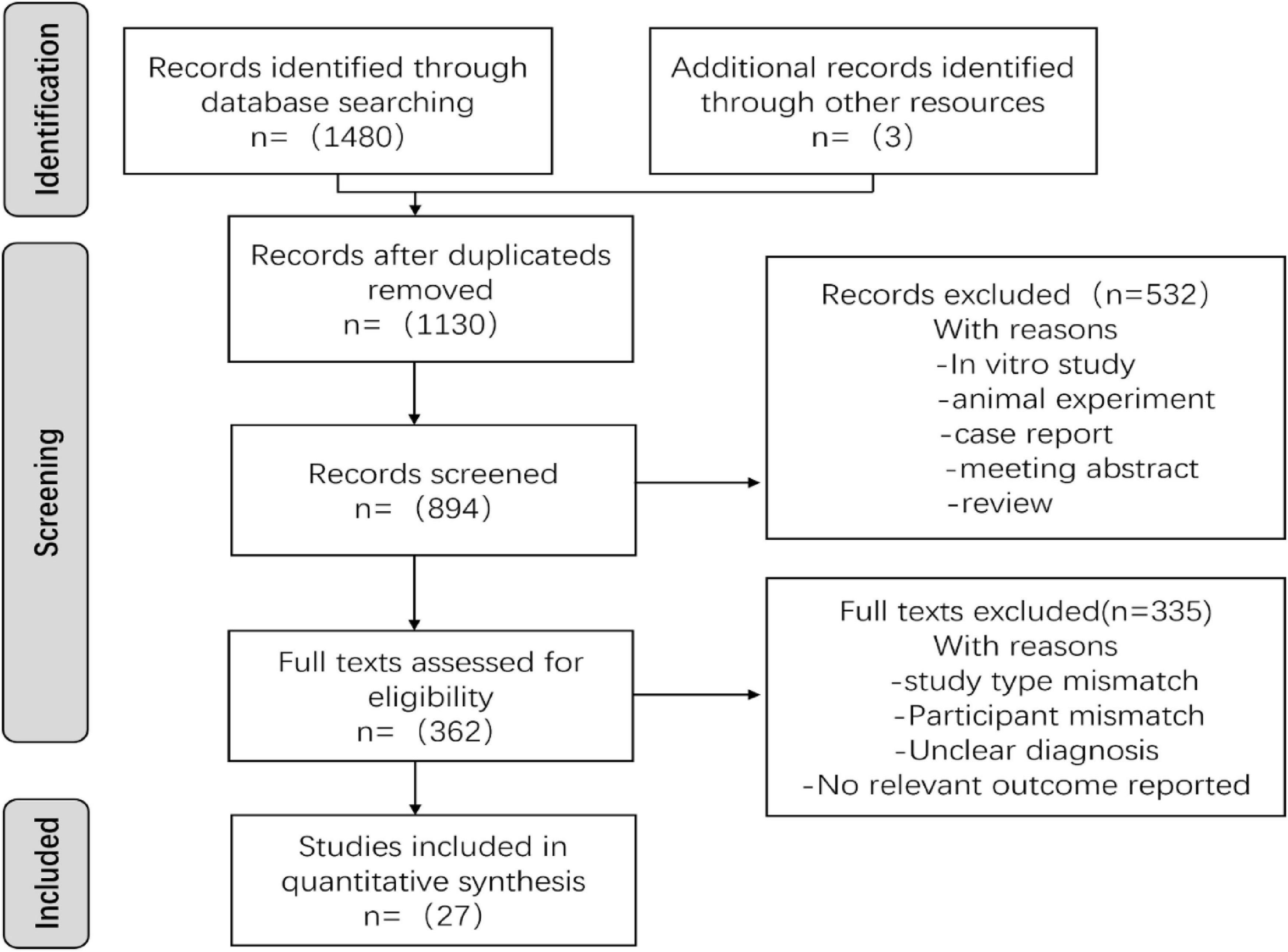

In this study, we identified a total of 1,483 records. After conducting initial abstract and full-text screening, we ultimately included 27 studies, as shown in Figure 1.

Study characteristics

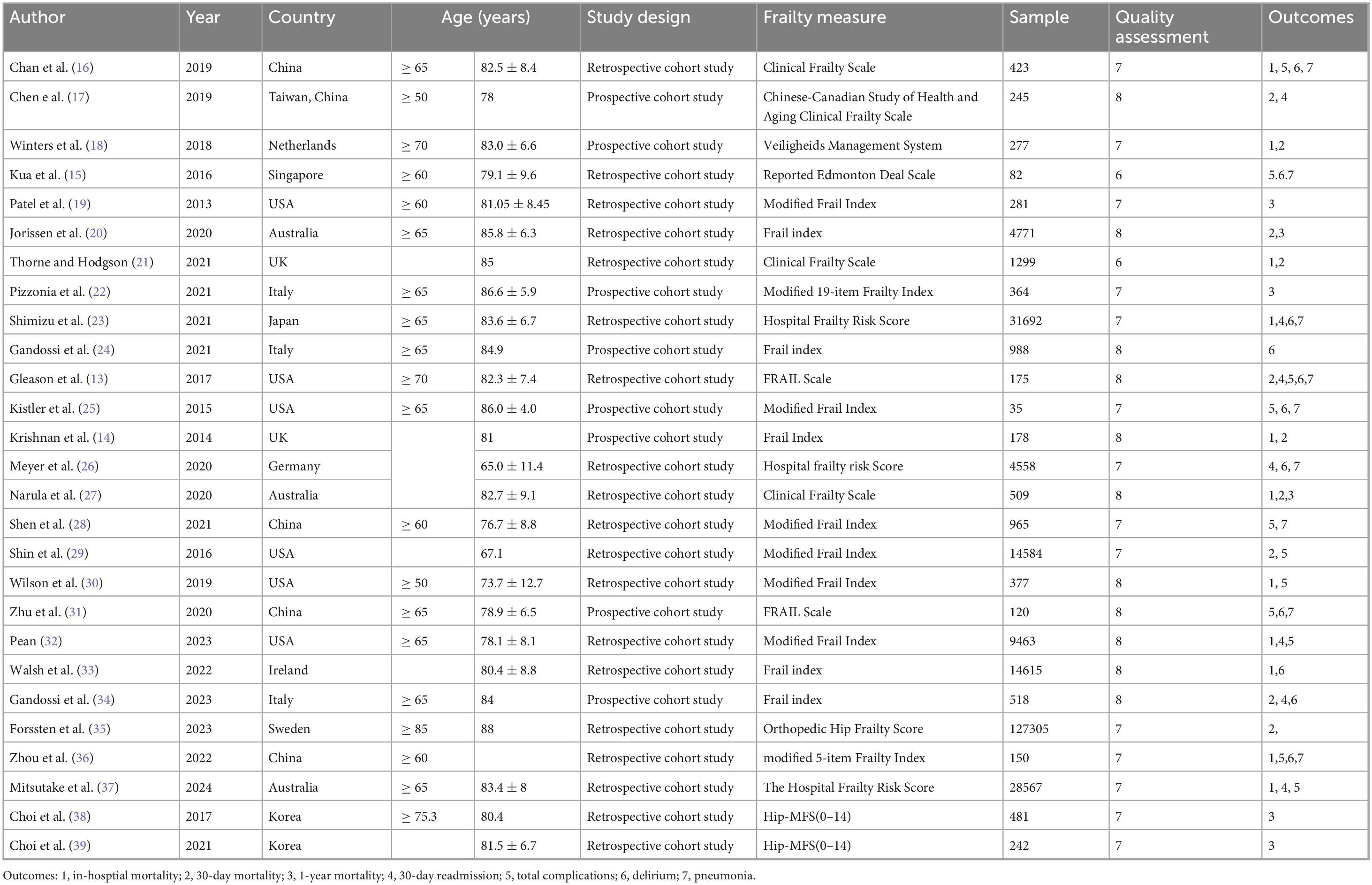

This systematic review included 243,264 patients across 27 cohort studies (8 prospective and 19 retrospective studies) conducted in 12 countries. Among the 27 studies, 25 were classified as high quality, while 2 were rated as moderate quality, as shown in Table 1. The characteristics of the nine different frailty scales in Table 2.

Mortality

In-hospital mortality

Ten studies involving 61,206 patients examined the impact of preoperative frailty on in-hospital mortality after hip fracture surgery. The meta-analysis revealed high heterogeneity (I2 = 90.5%); therefore, we used a random-effects model. The results indicated that frailty was statistically significantly associated with in-hospital mortality (RR = 3.20, 95%: CI: 1.93, 5.31), as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Forest plot of mortality rates in frail patients. (a) In-hospital mortality. (b) 30-day mortality. (c) One-year mortality.

Thirty-day mortality

Ten studies involving 141,164 patients reported the impact of preoperative frailty on 30-day mortality after hip fracture surgery. The meta-analysis revealed high heterogeneity (I2 = 95.8%). Therefore, a random-effects model was employed, which indicated that preoperative frailty was significantly associated with an increased risk of 30-day mortality (RR = 3.91, 95% CI: 1.89, 8.07), as shown in Figure 2.

One-year mortality

Seven studies involving 7,715 patients reported 1-year mortality following hip fracture surgery. The meta-analysis revealed high heterogeneity (I2 = 91.4%). It using the random-effects model indicated that preoperative frailty was statistically significantly associated with 1-year mortality (RR = 1.50, 95%CI: 1.39, 1.61), as illustrated in Figure 2.

Overall complications

A meta-analysis of 10 studies, which included 54,791 patients, was conducted to assess the overall complications following hip fracture surgery with high heterogeneity (I2 = 96.8%). Frailty significantly increased the risk of complications (RR = 2.81, 95% CI: 1.67, 4.74) in the random-effects model meta-analysis, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Forest plot of complications in frail patients. (a) All complications. (b) Deliruim. (c) Pneumonia.

Delirium

In a meta-analysis of 10 studies involving 44,537 patients who underwent hip fracture surgery with a high level of heterogeneity (I2 = 96.5%). Frailty was associated with a significantly increased risk of delirium (RR = 4.44, 95% CI: 2.34, 8.41) in the random-effects model meta-analysis (Figure 3).

Pneumonia

Nine studies reported the incidence of postoperative pneumonia in 32,012 patients following hip fracture surgery with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 63%). Frailty significantly increased the risk of pneumonia (RR = 4.09, 95% CI: 2.39, 7.01), according to the random-effects model meta-analysis presented in Figure 3.

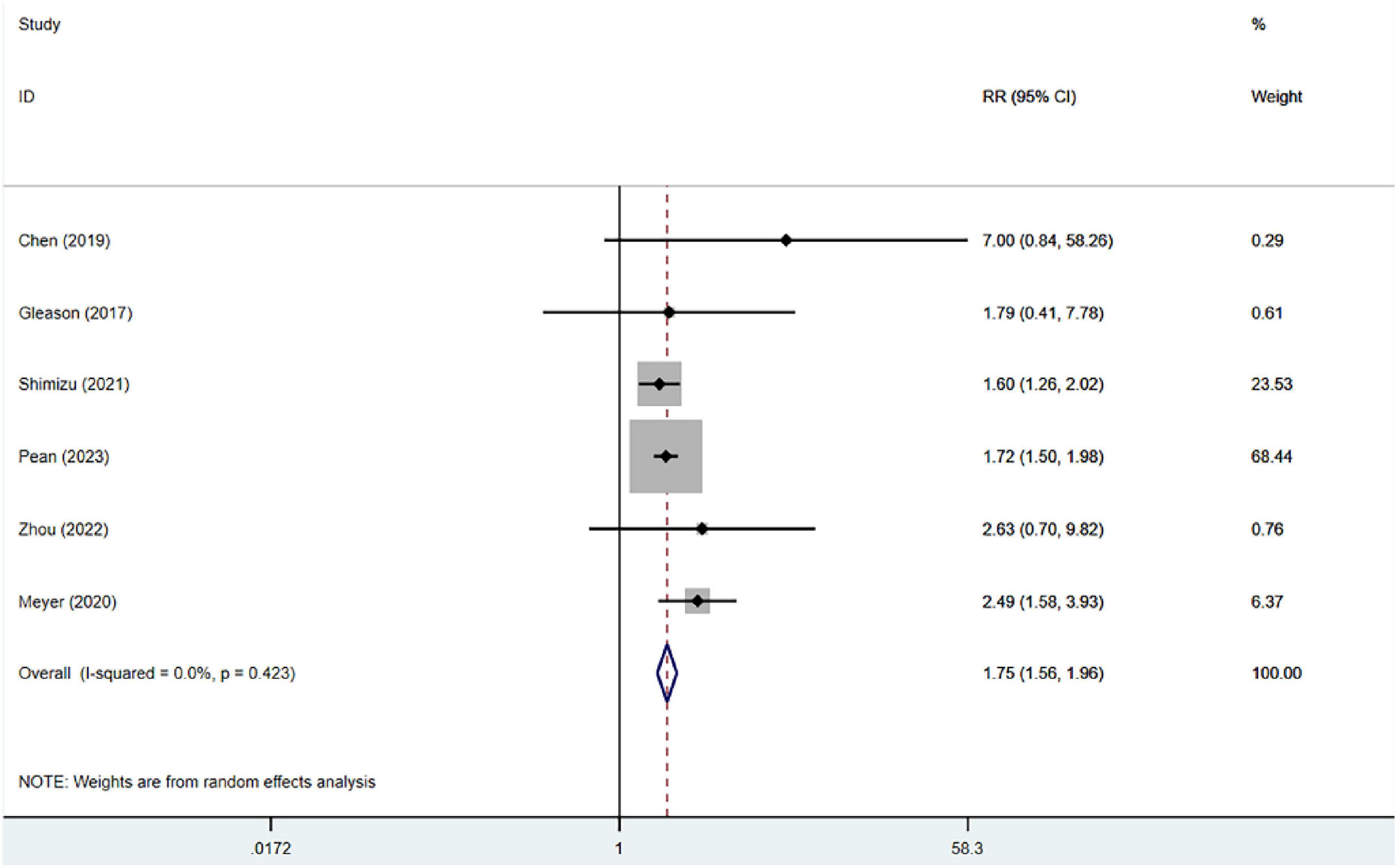

Thirty-day readmission

Six studies, which included 40,429 patients, reported on 30-day readmissions following hip fracture surgery. The heterogeneity analysis revealed no significant statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). Frailty was significantly associated with 30-day readmission (RR = 1.75, 95% CI: 1.56, 1.96) in the fixed-effects model meta-analysis, as shown in Figure 4.

Sensitivity and subgroup analysis

Sensitivity analysis identified the study by Walsh as the primary source of heterogeneity for in-hospital mortality. Exclusion of this study substantially reduced heterogeneity (I2 = 40.1%), (RR = 2.08, 95% CI: 1.86, 2.33), though the results remained unstable.

Similarly, for 30-day mortality which exhibited substantial heterogeneity, sensitivity analysis revealed the study by Forssten as the major contributing factor. After removing this study, heterogeneity was reduced (I2 = 71.9%), (RR = 2.09, 95% CI: 1.70, 2.40), yet the results continued to demonstrate instability.

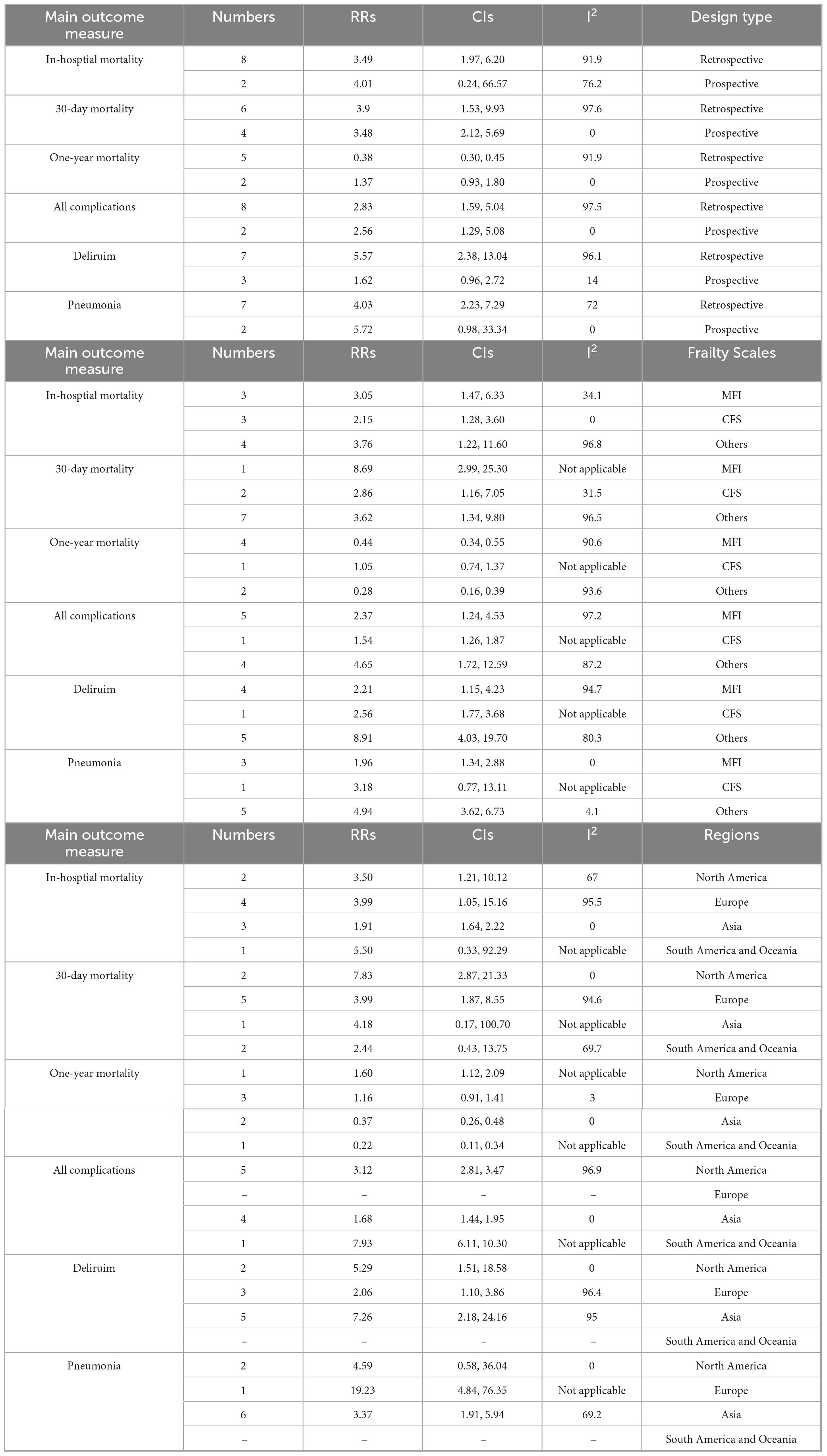

Subgroup analyses revealed significant variability in results from retrospective studies and certain frailty assessment tools, such as the CFS, demonstrated less heterogeneity. Geographical regions revealed considerable heterogeneity across most outcome measures (Table 3). Meta-regression identified the study design and the frailty assessment tools as the primary sources of this variability.

Publication bias

The overall risk of publication bias was low; however, funnel plot asymmetry was observed for the specific outcome of 1-year mortality, with both Begg’s test and Egger’s test indicating potential heterogeneity. The trim-and-fill method was subsequently employed to adjust for this bias. Following four iterations, the algorithm imputed two hypothetical studies. After incorporating these studies, bringing the total to nine, the analysis no longer indicated the presence of publication bias. Notably, the adjusted pooled effect size (RR = 6.17, 95% CI: 3.88, 11.36) substantially altered the initial conclusion.

Discussion

This systematic review demonstrates that hip fracture patients with frailty have a significantly elevated risk of postoperative adverse events compared to their non-frail counterparts. Subgroup analyses further support this conclusion: across different study designs, assessment tools, and geographical regions, outcome indicators including 30-day mortality after discharge, overall complications, postoperative delirium, postoperative pneumonia, and 30-day readmission rates consistently show a stable association between frailty and adverse outcomes.

However, for the specific outcome of in-hospital mortality, different study designs revealed inconsistent strength of association. Retrospective studies indicated that frailty significantly increased the risk of in-hospital mortality, whereas this association did not reach statistical significance in prospective studies. We posit that this discrepancy may be related to the high heterogeneity in frailty assessment tools used across prospective studies (e.g., varied frailty indices, hospital frailty risk scores). Inconsistencies in measurement tools lead to differences in the definition and measurement criteria of key exposure factors; even within the subgroup of higher-quality prospective studies, such heterogeneity may introduce additional variability, thereby diluting the true pooled effect size and reducing statistical power. Furthermore, the analysis of 1-year mortality suggested the presence of publication bias. After adjustment using the trim-and-fill method, the effect size was attenuated and lost statistical significance, indicating that the current evidence for this outcome is limited. In summary, this study supports preoperative frailty as an important predictor of multiple adverse postoperative outcomes in hip fracture patients. However, conclusions regarding specific outcomes such as in-hospital mortality require further validation through more high-quality, prospective cohort studies with standardized measurement tools.

Frailty manifests as diminished physiological reserve and impaired stress response capacity (40), and is closely associated with musculoskeletal disorders. As a serious complication of osteoporosis in older adults (41), hip fracture typically requires surgical intervention, with mortality representing a critical prognostic indicator (42). Previous studies have confirmed that preoperative frailty is significantly associated with in-hospital and post-discharge mortality at various time points among elderly hip fracture patients (43), particularly in the very old population. For instance, an Italian study reported a 1-year postoperative mortality rate of 50% in frail patients, markedly higher than the 10% observed in non-frail counterparts (22). Through this larger-scale systematic review, we further substantiate that preoperative frailty demonstrates strong correlation with 30-day postoperative mortality in hip fracture patients.

Regarding postoperative complications, this systematic review demonstrates a significant association between frailty and the risk of overall postoperative complications. However, substantial heterogeneity was observed in the definition of “overall complications” across studies. While some studies encompassed a broad range of events, including deep vein thrombosis, pneumonia, delirium, and pressure ulcers, others were restricted to only deep vein thrombosis and pneumonia. This inconsistency in definitions, combined with variations in the assessment tools used for frailty, collectively contributed to the heterogeneity in the complication analysis. Sensitivity analysis revealed that the pooled results changed significantly after excluding the studies by Shin and Mitsutake (28, 37). Furthermore, meta-regression confirmed that differences in assessment tools were the primary source of this heterogeneity.

The 30-day readmission rate serves as a crucial quality-of-care indicator (44), with its elevation being closely associated with increased postoperative complication rates. Early readmission following hip fracture surgery not only elevates patient mortality risk but also imposes a substantial financial burden on healthcare systems (45). Furthermore, the study by Ma demonstrated that frailty adversely affects the maintenance of healthy lifespan in older patients, as evidenced by a 1.4-fold higher rate of trauma-related readmissions within 6 months among frail patients compared to their non-frail counterparts (15). Our findings are consistent with this evidence, supporting the clinical value of frailty as a valid predictor for readmission risk.

Heterogeneity analysis revealed substantial heterogeneity across several outcome measures, primarily attributable to highly influential individual studies. Notably, the heterogeneity in in-hospital mortality was mainly driven by the study by Walsh et al., which employed a multidimensional frailty assessment tool and had a large sample size (n = 14,625), granting it considerable weight in the pooled analysis. The exclusion of this study resulted in significant changes to the results, indicating limited robustness for this particular outcome. Conversely, heterogeneity in 30-day mortality predominantly originated from the study by Forssten et al. (35), which enrolled an exceptionally large cohort (n = 127,305) with a mean age ≥ 85 years, potentially explaining its effect size divergence from the overall trend. These findings suggest that the reliability of the affected outcomes requires further validation through additional high-quality studies with improved methodological consistency.

Comparative assessment of frailty screening instruments demonstrated that although various tools exhibited comparable performance in predicting mortality, complications, and readmission, the choice of instrument remained a major source of heterogeneity. The nine tools examined in this study showed substantial variations in structure and time requirements, ranging from comprehensive multidimensional assessments like the Frailty Index to brief instruments such as the FRAIL scale, with administration times varying from seconds to 60 min. Notably, the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) demonstrated particular advantage in predicting in-hospital mortality (46, 47), while both the 5-item modified Frailty Index (mFI-5) and CFS-given their rapid administration, device-independent nature, and minimal training requirements-proved particularly suitable for mobility-restricted hip fracture patients, indicating high clinical feasibility.

Methodologically, this systematic review possesses several methodological strengths as the first to comprehensively evaluate the relationship between frailty and hip fracture outcomes by incorporating both Chinese and English databases. First, we restricted inclusion to cohort studies, thereby effectively minimizing selection and recall biases commonly associated with cross-sectional designs. Second, beyond employing random-effects models for data synthesis and reporting heterogeneity estimates, we conducted sensitivity analyses and meta-regression to trace heterogeneity sources, and performed subgroup analyses based on study design, assessment tools, and geographical regions-collectively demonstrating a comprehensive approach to verifying the robustness of our findings.

Notwithstanding the significantly elevated mortality risk associated with frailty, surgical intervention remains the essential treatment for hip fractures. Based on the accumulated evidence, we recommend implementing either the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) or 5-item modified Frailty Index (mFI-5) as standardized preoperative screening tools. Patients identified as frail through these instruments should be enrolled in a systematic perioperative management pathway incorporating prehabilitation interventions, minimally invasive surgical strategies, multimodal analgesia, and targeted postoperative care.

The clinical urgency of this approach is underscored by epidemiological data: frailty prevalence reaches 14.9–31.9% among community-dwelling older adults (48) and is substantially higher in hospitalized populations (49). Moreover, frail individuals face a 1.8-fold increased risk of falls compared to robust counterparts (50). Integrating these epidemiological insights with our findings demonstrating the robust frailty-outcome association, we have identified a critical clinical pathway: “frailty → falls → fracture → postoperative complications.” This cascade represents a significant threat to elderly health.

Therefore, the integration of standardized frailty assessment into routine clinical practice constitutes not only a crucial measure for improving surgical outcomes but also a foundational element in advancing healthy aging. Within future healthcare frameworks, frailty assessment should serve as a cornerstone for risk stratification, systematically informing clinical decision-making across the continuum from community-based prevention to comprehensive perioperative management.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. These include the relatively limited sample sizes of some included studies, absence of detailed data on fracture-specific locations, heterogeneity in frailty assessment tools across studies, and potential publication bias. While this meta-analysis of observational studies can confirm an association, it cannot infer a causal relationship due to potential unmeasured or residual confounding factors. Furthermore, future investigations are warranted with larger-scale prospective designs and standardized assessment protocols to better elucidate the underlying mechanisms through which frailty influences hip fracture outcomes.

Conclusion

Preoperative frailty is likely to have a substantial impact on the prognosis of hip fracture patients, markedly elevating the risk of patient mortality, postoperative complications, and 30-day readmission rates. The heterogeneity attributable to varying frailty assessment tools is considerable, and future research should prioritize the development of frailty assessment tools tailored for preoperative hip fracture evaluations.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

PT: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Data curation. YY: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Validation, Formal analysis, Project administration. TH: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Methodology, Data curation, Investigation. LW: Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Supervision. QZ: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Investigation. YC: Data curation, Supervision, Writing – review editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Provincial Health Care Foundation (Grant No. 2023-2301).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

CNKI, China National Knowledge Infrastructure; NOS, Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; MRR, Relative Risk; CI, Confidence Interval; CFS, Clinical Frailty Scale; MeSH, Medical, Subject Headings; mFI, modified Frailty Index; DVT, Deep Vein Thrombosis; CSHA, Canadian Study of Health and Aging; mFI-5, 5-item modified Frailty Index.

References

1. Handoll HH, Cameron ID, Mak JC, Panagoda CE, Finnegan TP. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for older people with hip fractures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2021). 11:Cd007125.

2. Gullberg B, Johnell O, Kanis JA. World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporos Int. (1997) 7:407–13.

3. Hu F, Jiang C, Shen J, Tang P, Wang Y. Preoperative predictors for mortality following hip fracture surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury. (2012) 43:676–85.

4. Karres J, Kieviet N, Eerenberg JP, Vrouenraets BC. Predicting early mortality after hip fracture surgery: the hip fracture estimator of mortality Amsterdam. J Orthop Trauma. (2018) 32:27–33.

5. Chen X, Shen Y, Hou L, Yang B, Dong B, Hao Q. Sarcopenia index based on serum creatinine and cystatin C predicts the risk of postoperative complications following hip fracture surgery in older adults. BMC Geriatr. (2021) 21:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02522-1

6. Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, Voshaar RCO. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2012) 60:1487–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04054.x

7. Hoogendijk EO, Afilalo J, Ensrud KE, Kowal P, Onder G, Fried LP. Frailty: implications for clinical practice and public health. Lancet (2019) 394:1365–75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31786-6

8. Woolford SJ, Sohan O, Dennison EM, Cooper C, Pate HP. Approaches to the diagnosis and prevention of frailty. Aging Clin Exp Res. (2020) 32:1629–37. doi: 10.1007/s40520-020-01559-3

9. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2001) 56:M146–56.

10. Mitnitski AB, Mogilner AJ, Rockwood K. Accumulation of deficits as a proxy measure of aging. ScientificWorldJournal. (2001) 1:323–36.

11. Morley JE, Malmstrom TK, Miller DK. A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J Nutr Health Aging. (2012) 16:601–8. doi: 10.1007/s12603-012-0084-2

12. Kua J, Ramason R, Rajamoney G, Chong MS. Which frailty measure is a good predictor of early post-operative complications in elderly hip fracture patients? Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. (2016) 136:639–47. doi: 10.1007/s00402-016-2435-7

13. Gleason LJ, Benton EA, Alvarez-Nebreda ML, Weaver MJ, Harris MB, Javedan H. FRAIL questionnaire screening tool and short-term outcomes in geriatric fracture patients. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2017) 18:1082–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.07.005

14. Krishnan M, Beck S, Havelock W, Eeles E, Hubbard RE, Johansen A. Predicting outcome after hip fracture: using a frailty index to integrate comprehensive geriatric assessment results. Age Ageing. (2014) 43:122–6.

15. Ma Y, Wang A, Lou Y, Peng D, Jiang Z, Xia T. Effects of frailty on outcomes following surgery among patients with hip fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). (2022) 9:829762.

16. Chan S, Wong EKC, Ward SE, Kuan D, Wong CL. The predictive value of the clinical frailty scale on discharge destination and complications in older hip fracture patients. J Orthop Trauma. (2019) 33:497–92. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001518

17. Chen CL, Chen CM, Wang CY, Ko PW, Chen CH, Hsieh CP, et al. Frailty is associated with an increased risk of major adverse outcomes in elderly patients following surgical treatment of hip fracture. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:19135. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55459-2

18. Winters AM, Hartog LC, Roijen H, Brohet RM, Kamper AM. Relationship between clinical outcomes and Dutch frailty score among elderly patients who underwent surgery for hip fracture. Clin Interv Aging. (2018) 13:2481–6. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S181497

19. Patel KV, Brennan KL, Brennan ML, Jupiter DC, Shar A, Davis ML. Association of a modified frailty index with mortality after femoral neck fracture in patients aged 60 years and older. Clin Orthop Relat Res. (2014) 472:1010–7.

20. Jorissen RN, Lang C, Visvanathan R, Crotty M, Inacio MC. The effect of frailty on outcomes of surgically treated hip fractures in older people. Bone. (2020) 136:115327.

21. Thorne G, Hodgson L. Performance of the nottingham hip fracture score and clinical frailty scale as predictors of short and long-term outcomes: a dual-centre 3-year observational study of hip fracture patients. J Bone Miner Metab. (2021) 39:494–500. doi: 10.1007/s00774-020-01187-x

22. Pizzonia M, Giannotti C, Carmisciano L, Signori A, Rosa G, Santolini F, et al. Frailty assessment, hip fracture and long-term clinical outcomes in older adults. Eur J Clin Invest. (2021) 51:e13445.

23. Shimizu A, Maeda K, Fujishima I, Kayashita J, Mori N, Okada K, et al. Hospital frailty risk score predicts adverse events in older patients with hip fractures after surgery: analysis of a nationwide inpatient database in Japan. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. (2022) 98:104552. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2021.104552

24. Gandossi CM, Zambon A, Oliveri G, Codognola M, Szabo H, Cazzulani I, et al. Frailty, post-operative delirium and functional status at discharge in patients with hip fracture. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2021) 36:1524–30.

25. Kistler EA, Nicholas JA, Kates SL, Friedman SM. Frailty and short-term outcomes in patients with hip fracture. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. (2015) 6:209–14.

26. Meyer M, Parik L, Leib F, Renkawitz T, Grifka J, Weber M. Hospital frailty risk score predicts adverse events in primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. (2020) 35:3498.e–504.e.

27. Narula S, Lawless A, D’Alessandro P, Jones CW, Yates P, Seymour H. Clinical frailty scale is a good predictor of mortality after proximal femur fracture: a cohort study of 30-day and one-year mortality. Bone Jt Open. (2020) 1:443–9. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.18.BJO-2020-0089.R1

28. Shen Y, Hao Q, Wang Y, Chen X, Jiang J, Dong B, et al. The association between preoperative modified frailty index and postoperative complications in Chinese elderly patients with hip fractures. BMC Geriatr. (2021) 21:370.

29. Shin JI, Keswani A, Lovy AJ, Moucha CS. Simplified frailty index as a predictor of adverse outcomes in total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. (2016) 31:2389–94. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.04.020

30. Wilson JM, Boissonneault AR, Schwartz AM, Staley CA, Schenker ML. Frailty and malnutrition are associated with inpatient postoperative complications and mortality in hip fracture patients. J Orthop Trauma. (2019) 33:143–8.

31. Zhu SQ, Xing YH, Zhang L, Chen LJ, Liu XS, Gu EW. Predictive value of frailty scale versus frailty, phenotypic assessment for postoperative outcomes in elderly hip fracture patients. J Clin Anesth. (2020) 36:962–5.

32. Pean CA, Thomas HM, Singh UM, DeBaun MR, Weaver MJ, von Keudell AG. Use of a six-item modified frailty index to predict 30-day adverse events, readmission, and mortality in older patients undergoing surgical fixation of lower extremity, pelvic, and acetabular fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. (2023) 7:e22.00286. doi: 10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-22-00286

33. Walsh M, Ferris H, Brent L, Ahern E, Coughlan T, Romero-Ortuno R. Development of a frailty index in the Irish hip fracture database. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. (2023) 143:4447–54. doi: 10.1007/s00402-022-04644-6

34. Gandossi CM, Zambon A, Ferrara MC, Tassistro E, Castoldi G, Colombo F, et al. Frailty and post-operative delirium influence on functional status in patients with hip fracture: the GIOG 2.0 study. Aging Clin Exp Res. (2023) 35:2499–506. doi: 10.1007/s40520-023-02522-8

35. Forssten MP, Mohammad ISMAILA, Ioannidis I, Wretenberg P, Borg T, Cao Y, et al. The mortality burden of frailty in hip fracture patients: a nationwide retrospective study of cause-specific mortality. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. (2023) 49:1467–75. doi: 10.1007/s00068-022-02204-6

36. Zhou Y, Wang L, Cao A, Luo W, Xu Z, Sheng Z, et al. Modified frailty index combined with a prognostic nutritional index for predicting postoperative complications of hip fracture surgery in elderly. J Invest Surg. (2022) 35:1739–46.

37. Mitsutake S, Sa Z, Long J, Braithwaite J, Levesque JF, Watson DE, et al. The role of frailty risk for fracture-related hospital readmission and mortality after a hip fracture. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. (2024) 117:105264. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2023.105264

38. Choi JY, Cho KJ, Kim SW, Yoon SJ, Kang MG, Kim KI, et al. Prediction of mortality and postoperative complications using the hip-multidimensional frailty score in elderly patients with hip fracture. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:42966.

39. Choi JY, Kim JK, Kim KI, Lee YK, Koo KH, Kim CH. How does the multidimensional frailty score compare with grip strength for predicting outcomes after hip fracture surgery in older patients? A retrospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. (2021) 21:234. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02150-9

40. Morley JE, Vellas B, van Kan GA, Anker SD, Bauer JM, Bernabei R, et al. Frailty consensus: a call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2013) 14:392–7.

41. Greco EA, Pietschmann P, Migliaccio S. Osteoporosis and sarcopenia increase frailty syndrome in the elderly. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2019) 10:255. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00255

42. Pioli G, Bendini C, Pignedoli P, Giusti A, Marsh D. Orthogeriatric co-management - managing frailty as well as fragility. Injury. (2018) 49:1398–402. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2018.04.014

43. Xu BY, Yan S, Low LL, Vasanwala FF, Low SG. Predictors of poor functional outcomes and mortality in patients with hip fracture: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. (2019) 20:568. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2950-0

44. Mcilvennan CK, Eapen ZJ, Allen LA. Hospital readmissions reduction program. Circulation. (2015) 131:1796–803.

45. Curry SD, Carotenuto A, Deluna DA, Maar DJ, Huang Y, Samson KK, et al. Higher readmission rates after hip fracture among patients with vestibular disorders. Otol Neurotol. (2021) 42:e1333–8. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000003277

46. Rockwood K, Song X, Macknight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. (2005) 173:489–95.

47. Bishwajit G, O’LEARY DP, Ghosh S, Yaya S, Shangfeng T, Feng Z. Physical inactivity and self-reported depression among middle- and older-aged population in South Asia: World health survey. BMC Geriatr. (2017) 17:100. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0489-1

48. Ziller C, Braun T, Thiel C. Frailty phenotype prevalence in community-dwelling older adults according to physical activity assessment method. Clin Interv Aging. (2020) 15:343–55.

49. Hammami S, Zarrouk A, Piron C, Almas I, Sakly N, Latteur V. Prevalence and factors associated with frailty in hospitalized older patients. BMC Geriatr. (2020) 20:144.

Keywords: frailty, hip fracture, mortality, systematic review, observational studies

Citation: Tian P, Yang Y, He T, Wang L, Zhang Q and Cai Y (2025) Impact of frailty on postoperative complications in older adults after hip fracture: a systematic review of observational studies. Front. Med. 12:1667462. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1667462

Received: 16 August 2025; Revised: 31 October 2025; Accepted: 06 November 2025;

Published: 24 November 2025.

Edited by:

Cristiano Capurso, University of Foggia, ItalyReviewed by:

Mengcun Chen, University of Pennsylvania, United StatesAna Maria Dumitriu, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Romania

Copyright © 2025 Tian, Yang, He, Wang, Zhang and Cai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yingying Cai, YzE4MDMwODA1NDEzQDEyNi5jb20=

Peng Tian

Peng Tian Yi Yang1

Yi Yang1