Abstract

Background:

Co-infection with HIV in patients infected with the mpox virus (MPXV) may pose a potential risk of influencing neurological manifestations. We aimed to synthesize the central nervous system (CNS) symptoms reported by mpox patients without HIV co-infection.

Methods:

We conducted a search for studies on mpox published in PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane, CNKI, Wanfang Data, and Weipu Data till 2023/11/19. The type of studies included were cohort studies, case series, case–control trials, and randomized controlled trials. Reviews, editorials, pre-prints, and conference proceedings were excluded. We only included studies that reported neurological manifestations in mpox patients without HIV. STATA (version 16.0) was used to create forest plots that pooled the mean scores of CNS symptoms in mpox patients. Outcomes were presented with 95% confidence interval (95% CI), and heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic.

Results:

We identified 2,311 unique studies, of which 14 (with a total of 989 patients) met the inclusion criteria. The quality of each study was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) tool. The majority of the included articles were rated as medium quality. The major CNS clinical features were myalgia, headache, and fatigue/asthenia, with pooled mean scores of 0.22 (95% CI: 0.13–0.31), 0.25 (95% CI: 0.17–0.33) and 0.28 (95% CI: 0.21–0.37) in mpox patients without HIV. The results of the sensitivity analysis showed that the meta-analysis results were stable. Additionally, Egger’s test (p < 0·05) suggested that a low risk of publication bias in the included literature.

Conclusion:

The MPXV may cause clinical nervous system injuries, including headache, myalgia, and fatigue/asthenia, as observed in approximately 25% (±3%) of the studied population.

Systematic review registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42024464199, CRD42024464199.

1 Introduction

On 23 July 2022 and again on 14 August 2024, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the ongoing mpox outbreak a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC). The mpox virus (MPXV), which belongs to the Orthopoxvirus genus of the Poxviridae family, is a double-stranded DNA virus that affects humans and livestock. In 1958, MPXV was first discovered in monkeys (1). The first detected human case of mpox infection occurred in a 9-month-old child who had not received a smallpox vaccination in the Congo in 1970 (2). Following this initial case, mpox was mainly limited to epidemics and outbreaks in some countries in Central and Western Africa (3, 4). Furthermore, the recent mpox outbreak mainly affected bisexual men who have sex with men (MSM) or explicitly identified gay individuals (5). The majority of mpox patients predominantly presented with systemic symptoms that included fever, skin rash, headache, lymphadenopathy, and myalgia, among others (6).

Interestingly, patients with MPXV have recently been found to exhibit a number of neurological symptoms, including headache, myalgia, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, and other manifestations. In fact, it has been previously reported that MPXV can infect nerve cells through the olfactory epithelium and can spread through infected monocytes/macrophages in animals (7). In addition, animal studies have revealed that MPXV is capable of crossing the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and reaching brain tissue (8). However, it is reported that 38–50% of mpox patients have HIV infection (9). Furthermore, previous studies have suggested that early HIV infection can also cause central nervous system (CNS) manifestations in early stages (10). This raises the question of whether the clinically observed CNS symptoms are caused by MPXV or HIV.

To date, CNS symptoms in mpox patients, whether HIV-positive or HIV-negative, remain poorly understood and characterized due to an evident lack of literature. Accordingly, in this meta-analysis, we focus exclusively on mpox cases that are HIV-negative to eliminate the effect of HIV co-infection and comprehensively confirm whether the clinical neurological manifestations are caused by MPXV.

2 Methods

2.1 Search strategy and selection criteria

The study protocol for this meta-analysis followed the PRISMA guidelines and was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42024464199). Electronic databases that included PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane, CNKI, Wanfang Data, and Weipu Data were searched for articles published till 2023/11/19. Keywords included (“mpox” OR “monkeypox” OR “monkeypox virus”) AND (“fever” OR “chill” OR “myalgia” OR “headache” OR “fatigue” OR “asthenia” OR “malaise” OR “pruritus” OR “nausea” OR “vomit” OR “photophobia” OR “altered conscious” OR “agitation” OR “anorexia”). Details of the search strategy are presented in Supplementary material. We included studies that reported the prevalence of at least two CNS clinical features in HIV-negative mpox patients, provided that there were at least 10 cases. There were no language-based exclusion criteria, and participants could be of any age and ethnicity as long as they were infected with mpox. Cohort studies, case series, case–control trials, and randomized controlled trials were included. The exclusion criteria are as follows: (1) duplicate publications; (2) studies that are reviews, books, documents, and meta-analysis papers; (3) articles without accessible full text; (4) single case reports and studies involving fewer than 10 MPXV-infected individuals; and (5) articles that are not related to mpox or those focusing on HIV-negative individuals. We only used data included in the articles, and we did not contact the authors of the included research. We also did not search trial registry platforms or request information from any unpublished studies identified. Screening of titles and abstracts for each article was conducted independently by two authors. Subsequently, potential qualifying studies were identified by examining full texts. Any disagreement between the two authors was arbitrated by a third author.

2.2 Data analysis

Two authors independently screened citations using a standardized form with predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria and extracted data. Duplicate studies were excluded, and two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of the identified research articles. They then reviewed the full text of the studies that met the eligibility criteria. We excluded studies with fewer than 10 cases to reduce publication bias. For studies that met the inclusion criteria, we extracted the following data: (1) first author; (2) publication year; (3) start and end year of inclusion; (4) study design; (5) sample size; (6) characteristics of cases (sex assigned at birth, age, country, ethnicity, sexual orientation including heterosexual, MSM, and bisexual, and HIV status); and (7) the outcome of interest: the proportion of any CNS clinical features in humans infected with MPXV.

Two reviewers employed quality assessment tools to evaluate the included studies. The quality of the included cohort studies was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) (11), while the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) tool was used for the appraisal of cross-sectional studies (12). Utilizing NOS scores, the included studies were categorized as follows: overall scores of 0–3 indicate poor quality, 4–6 indicate fair quality, and 7–9 indicate good quality. The AHRQ tool has 11 items; a score of 1 is given for each item that is determined to be “Yes,” and a score of 0 is given for “No” or “Unclear.” Studies with total scores of 0 to 3 are considered low quality. Those with scores between 4 and 7 are typically regarded as medium quality, while scores ranging from 8 to 11 are classified as high quality. If two reviewers could not reach an agreement, a third reviewer would independently evaluate the study to resolve the conflict.

Each included study was summarized under the following headings: study design, participants (sample size, age, sex assigned at birth, ethnicity), and CNS manifestations. The data were then organized into a table. We collected the clinical data of mpox patients, of which the HIV-negative patients were extracted for further analysis. The medians and interquartile ranges of continuous data were converted to means and standard deviations. Forest plots were used to display the proportion of CNS symptoms reported in each study, along with the overall pooled prevalence estimates. Additionally, all analyses were performed using STATA (version 16·0), and the outcomes were presented with 95% confidence interval (95% CI). For all meta-analyses, the Cochrane Q, p-value, and I2 statistic were applied to check heterogeneity. When the p-value is greater than 0.1 or I2 is less than 50%, indicating no significant heterogeneity among the studies, the fixed-effect model was used to combine the data. Otherwise, a random-effects model was used (13), followed by further subgroup analysis. The reliability and robustness of the model were evaluated through sensitivity analysis. Additionally, we investigated the presence of publication bias using Egger’s test (14), with a p-value of less than 0.05 indicating the presence of publication bias.

3 Results

Seven databases, namely PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library, CNKI, Wanfang Data, and Weipu Data, were initially retrieved to obtain 2,311 potentially relevant articles. After the automatic and manual removal of duplicates, 2 independent authors screened the titles and abstracts of 1,403 studies and assessed the eligibility of the full text for 178 potential articles. Finally, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 14 articles were eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis (15–28). The full literature retrieval and screening process are presented in Figure 1. Overall, the articles included were published between 2022 and 2023, confirming a total of 989 cases of individuals with MPXV who did not have HIV infection. The sample size ranged from 10 to 266 participants. The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. All studies confirmed mpox infection through nucleic acid tests (NATs), except for one article that did not mention it (15). Furthermore, the studies focused on adult patients. The median age across nine studies varied from 25.5 to 37 years (n = 447), with the majority of the participants being men. The study populations primarily consisted of patients drawn from hospitals or centers for infectious diseases (17–21, 23, 24, 27, 28), laboratories (15, 25, 26), health systems (22), and the GeoSentinel Network (16). Then, the sample size ranged from 10 to 266 patients with mpox infection who did not have HIV. In terms of geographical distribution, the majority of the studies were conducted in Europe, Asia, North America, and South America.

Figure 1

PRISMA flow chart illustrating the selection procedure of the included studies.

Table 1

| Study | Location | Study population | Study type | Specimen detection | N | Time period of data collection | Age, years mean ± SD/median (IQR) | Sex (male/female) | Ethnic group | Neurological manifestations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zaqout et al. (28) | Qatar | Communicable Diseases Center in Doha, Qatar | Observational study | PCR | 12 | 13 May 2022–30 November 2022 | 33·5(24·5–37·5) | 10/2 | ·· | Fever 7/12, myalgia 3/12, fatigue/asthenia 3/12 |

| Kowalski et al. (23) | Central Europe | Hospital for Infectious Diseases in Warsaw, Poland | Cohort study | RT-PCR | 48 | 16 May 2022–30 October 2022 | 32 (26–37) | 48/0 | ·· | Fever 37/48, headache 4/48, myalgia 13/48, fatigue/asthenia/malaise 26/48 |

| Silva et al. (27) | Brazil | A major referral center for Infectious Diseases in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | Cohort study | RT-PCR | 96 | 12 June 2022–19 August 2022 | 31 (25–37·5) | 91(Cisgender men)/5(Cisgender women) | Black 34/65, Pardo (mixed) 14/65, White 18/65 | Fever 50/96, headache 32/96, myalgia 16/96, fatigue/asthenia 23/96, nausea 2/96 |

| Kim et al. (22) | USA | Two large health systems in South Florida | Retrospective observational study | PCR | 98 | 01 January 2020–10 September 2022 | 33 (28–42) | 89/9 | White 68/98, Black 24/98, Other 6/98 | Fever 33/98, headache 3/98, myalgia 18/96, fatigue/asthenia/malaise 13/96 |

| Pilkington et al. (26) | UK | Department of Sexual Health at King’s College Hospital in South-East London, UK | Retrospective observational study | PCR | 86 | May 2022–December 2022 | 34 (29–40) | 85/1 | White 11/86, Non-White 14/86, Unknown 61/86 | Fever 52/86, headache 18/86, myalgia 14/86 |

| Jun et al. (21) | China | Hangzhou Xixi Hospital | Retrospective study | NAT | 10 | 15 Jun 2023–05 August 2023 | 25·5 (23–31) |

10/0 | Yellow 10/10 | Fever 7/10, headache 3/10, myalgia 2/10, fatigue/asthenia 1/10 |

| Chen et al. (18) | China | Shenzhen Third People’s Hospital | Retrospective study | PCR | 19 | 09 June 2023–08 July 2023 | ·· | 19/0 | Yellow 19/19 | Fever 16/19, headache 3/19, myalgia 6/19, fatigue/asthenia 3/19 |

| Núñez et al. (25) | Mexico | National epidemiologic case report | Observational study | RT-RCR | 266 | 24 May 2022–05 September 2022 | ·· | 250/16 | ·· | Fever 205/266, headache 112/266, myalgia 119/266, fatigue/asthenia 85/266, nausea 5/266, vomiting 4/266 |

| Hoffmann et al. (20) | Germany | 42 German centers | Retrospective cohort study | PCR | 58 | 19 May 2022–30 June 2022 | 37 | 58/0 | ·· | Fever 28/52, headache 19/52 |

| Caria et al. (17) | Portugal | A Portuguese hospital | Retrospective observational study | NAAT | 16 | 05 May 2022–26 July 2022 | 31·0 (8·0) | 15/1 | ·· | Fever 8/16, headache 1/16, myalgia 2/16, fatigue/asthenia 2/16 |

| Fu et al. (19) | China | six major infectious disease hospitals and one Center for Disease Control and Prevention in China | Cross-sectional study | PCR | 50 | 01 June 2023–31 July 2023 | ·· | 50/0 | Yellow 50/50 | Fever 36/50, headache 8/50, myalgia 10/50, fatigue/asthenia 10/50 |

| Angelo et al. (16) | GeoSentinel Network (29 countries) | 71 clinical sites in 29 countries | Cross-sectional study | PCR | 134 | 01 May 2022–01 July 2022 | ·· | 134/0 | ·· | Fever 75/134, headache 20/134, myalgia 19/134, fatigue/asthenia malaise 57/134, nausea 2/134 |

| Kowalski et al. (23) | Portugal | ·· | Retrospective study | ·· | 20 | ·· | 32·5 ± 8·1 | 20 (cisgender men)/0 | ·· | Fever 12/20, headache 10/20, myalgia 12/20 |

| Maronese et al. (24) | Italy | Five dermatology referral centers in Italy | Retrospective study | PCR | 76 | 01 June 2022–31 October 2022 | ·· | ·· | ·· | Fever 47/76, headache 17/76, myalgia 23/76, fatigue/asthenia 29/76 |

Baseline study characteristics of mpox patients without HIV included in the study.

PCR, polymerase chain reaction; RT-PCR, real-time PCR; NAT, nucleic acid test; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test.

A total of 12 observational cohort studies were assessed using the NOS quality assessment tool, while 2 cross-sectional studies were evaluated using the AHRQ tool. Our results are summarized in Supplementary Tables S1, S2. The analysis of the existing literature revealed that only one study was of high quality (27), 12 studies were of medium quality (16–26, 28), and one study was of low quality (15). The majority of cohort studies lost points on comparability in the NOS due to the absence of a control group. In the AHRQ tool, the risk of bias stemmed mainly from items 2, 5, 7, 8, 9, and 11.

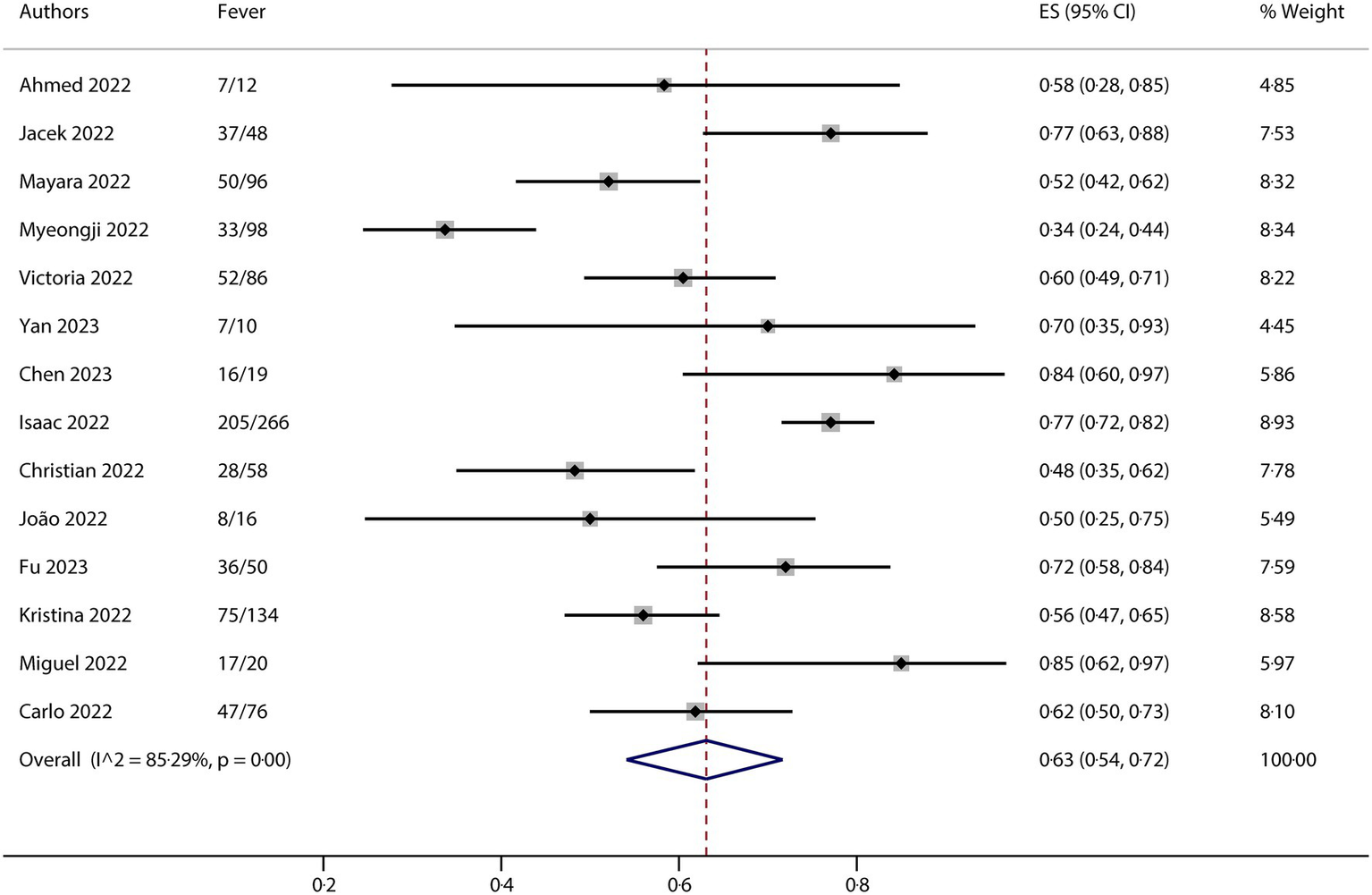

All studies included in this meta-analysis contained at least one neurological manifestation. A total of 14 studies were included in the analysis. The neurological manifestations were headache (13 studies), myalgia (13 studies), and fatigue/asthenia (12 studies), whereas fever (14 studies) was a comparative characteristic of non-neurological manifestations for mpox infection. The metaprop (version 1.06) was used to pool the effects and conduct the analysis. Forest plots demonstrated that all meta results of these characteristics exhibited substantial heterogeneity, with I2 ranging from 79.31 to 90.00% (Figures 2–5). Therefore, the random-effects model was employed to pool the mean scores, which were presented with weighted effect sizes and 95% CI. The mean pooled scores for headache, myalgia, fatigue/asthenia, and fever were 0.22 (95% CI: 0.13–0.31) (Figure 2), 0.25 (95% CI: 0.17–0.33) (Figure 3), 0.28 (95% CI: 0.21–0.37) (Figure 4), and 0.63 (95% CI: 0.54–0.72) (Figure 5) in mpox patients without HIV, respectively.

Figure 2

Forest plot of headache and comparative character in mpox patients without HIV co-infection.

Figure 3

Forest plot of myalgia and comparative character in mpox patients without HIV co-infection.

Figure 4

Forest plot of fatigue/asthenia and comparative character in mpox patients without HIV co-infection.

Figure 5

Forest plot of fever and comparative character in mpox patients without HIV co-infection.

The results of this meta-analysis suggested that there was high heterogeneity in clinical characteristics. For exploring potential sources of heterogeneity, we conducted a series of subgroup analyses for each of the clinical characteristics. The entire group is divided into different subgroups based on different factors, such as region, ethnicity, gender, and MSM ratio. The subgroup analysis was also conducted using metaprop (version 1.06), which indicated that the region might be the most important factor contributing to the observed heterogeneity (any subgroup containing no more than three studies would yield no results in the metaprop calculations). For headache, the total I2 is 90.00%, while it is 76.02% in the Europe subgroup. Although there are no results for the Asia, America, and Mixed subgroups because each contains three or fewer studies, we observed relatively good consistency across the different subgroups (Supplementary Figure S1A). For myalgia, the total I2 is 84.64%, while it is 0% in the Asia subgroup. As shown in Supplementary Figure S1B, there is a notable absence of outcomes in other subgroups. For fatigue/asthenia, the total I2 is 79.31%, but again, it is 0% in the Asia subgroup, with relatively good consistency observed in the other subgroups without results (Supplementary Figure S1C). Regarding the presence of fever, the total I2 is 85.29%. However, in the Asia and Europe subgroups, the values are 0% and 67.02%, respectively. The data indicated relatively good consistency in the American and Mixed subgroups, which also did not yield results (Supplementary Figure S1D).

We performed Egger’s test to assess the publication bias, and the results are presented in Supplementary Figure S2. The analysis of clinical research indicators in the literature showed that there was no risk of publication bias for each characteristic. The p-values for headache, myalgia, fatigue/asthenia, and fever were 0.089, 0.827, 0.930, and 0.543 (p < 0.05), respectively. The results of the bias analysis implied that there were no small-study effects in the analysis.

A sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the reliability and robustness. The results of the sensitivity analysis indicated that heterogeneity was not significantly impacted by the literature data selected for the meta-analysis. The conclusion was found to be relatively stable (Supplementary Figure S3).

4 Discussion

The most frequently reported neurological manifestations of human mpox were headache, myalgia, fatigue, and photophobia. Furthermore, MPXV can lead to potentially fatal illnesses, including seizures, encephalitis, visual deficits, and coma (29). It was found that MSM, particularly those infected with HIV, were the most affected group when having mpox infections (30). Any possible correlation between MPXV and CNS manifestations may potentially be further complicated by the impact of co-infection with HIV. Our meta-analysis aimed to explore the CNS symptoms of mpox patients who were not infected with HIV in order to exclude the effects of HIV on neurological manifestations. Studies including more than 10 cases of mpox without HIV were selected for this research. Overall, the results of the meta-analysis regarding neurological manifestations indicated that MPXV can indeed lead to clinical signs of nervous system infection. The findings of our pooled analysis revealed that the most prevalent CNS symptoms reported among patients infected with monkeypox were headache, myalgia, and fatigue/asthenia. In addition, the findings of the meta-analysis demonstrated strong consistency in the penetrance of three CNS symptoms, which ranged from 22 to 28%, suggesting that the overall rate of patients with clinical neurological symptoms of MPXV infection was approximately 25% (±3%). Notably, as an autoimmune clinical manifestation rather than a CNS symptom, fever symptom result manifests that the consistency of nervous system traits is not a random and accidental phenomenon. This highlights the significant impact of MPXV on the nervous system, indicating a need for further clinical attention. Additionally, the neurological manifestations observed are heterogeneous, with I2 values ranging from 79.31% to 90.00%. A subgroup analysis was conducted, which reduced the heterogeneity observed. These findings suggest that a particular region may be the primary contributor to the observed variability. The differences are likely related to distinct MPXV clades across various geographical regions, differing modes of transmission, and the inclusion of studies with limited sample sizes. Other understudied factors that may contribute to this heterogeneity include significant variations within regions. Some regions studied were grouped, and the ethnic demographics included individuals from diverse ethnic backgrounds, such as Indians, Europeans, and South Americans, which may also have contributed to the observed diversity.

Notably, the exact pathophysiology of the neuroinvasive and neurotropic nature of MPXV remains to be elucidated. However, studies conducted using animal models have suggested two probable mechanisms: (i) the olfactory epithelium route and (ii) the infection of macrophages/monocytes, which may allow the virus to permeate brain tissue by crossing the BBB (7, 8). It is noteworthy that a recent article emphasizes the potential brain cell tropism and neurovirulent activity of MPXV. The study highlights that MPXV preferentially infects astrocytes, causing the proteolytic cleavage of gasdermin B (GSDMB), which is an essential stage in the process of pyroptosis. Furthermore, this infection results in the death of inflammatory cells. Interestingly, treatment with dimethyl fumarate (DMF) has been shown to reduce MPXV infection and cell death (31). These findings provide possible treatment alternatives and shed light on the previously identified neuropathogenic effects of MPXV in humans. Further research is necessary to explore the specific routes by which the MPXV invades the brain as well as to understand the neurological manifestations experienced by mpox patients. It is important to note that the clinical manifestations of mpox and smallpox show significant similarities, particularly regarding neurological effects (32). Patients present common signs such as headache and lymphadenopathy during the prodromal phase of both mpox and smallpox (33). While mpox can lead to a range of neurological manifestations and very rarely results in encephalitis, encephalitis caused by smallpox is linked to significant morbidity and mortality (32). Further research is required to elucidate the nuances of neurological complications in both infections. Recently, there are no fully approved treatments or vaccines for MXPV. Since mpox and smallpox share a genetic resemblance, antiviral medications against orthopoxviruses such as tecovirimat, brincidofovir, and cidofovir, along with vaccinia immune globulin (VIG) and supportive care, can be used to treat mpox infection. ACAM2000 and JYNNEOS vaccinations have been suggested as possible prophylactic measures for adults who are highly susceptible to contracting smallpox and mpox (34). Interestingly, one recent study summarized the potential regulatory role of microRNA in the CNS during mpox infection, indicating that microRNAs could also be a possible target to treat mpox CNS symptoms (35). Further research is recommended to explore improved strategies and identify potential drug targets.

However, this meta-analysis does have some limitations. In terms of assessing the quality of the included studies, 13 of the studies analyzed were rated as having medium or low quality, highlighting the relatively underexplored nature of CNS symptoms in the context of the MPXV outbreak. In addition, the predominance of retrospective studies and the absence of a randomized controlled trial limited the relevance of our findings. Notably, there is a risk that neurological manifestations may not be accurately documented and reported. Comparatively, only 63% of MPXV infections were associated with fever, suggesting that a larger proportion of MPXV patients may actually have a nervous system infection. Establishing criteria for neurological severity is a challenging endeavor. Another potential limitation is that few articles have reported the diagnosis of neurological symptoms before the onset of the MPXV infection. Furthermore, patients with MPXV experienced other uncommon neurological manifestations such as nausea and vomiting. Nevertheless, due to a lack of sufficient research, we were unable to assess this phenomenon. Overall, our ability to synthesize data was hindered by factors such as the clade of MPXV, the ethnicity of mpox patients without HIV, and the uncertainty regarding the severity of CNS manifestations. In summary, our analysis presents the classical CNS symptoms associated with MPXV, including myalgia, headache, and fatigue/asthenia, and emphasizes the need for clinical attention to the neurological symptoms caused by mpox.

5 Conclusion

This meta-analysis demonstrates that MPXV can lead to significant neurological symptoms, with approximately 25% of patients exhibiting CNS manifestations, such as headache, myalgia, and fatigue/asthenia. The findings suggest that these neurological presentations are attributed to MPXV rather than HIV. However, further prospective studies are necessary to achieve a more comprehensive understanding and quantification of the severity of these clinical neurological manifestations.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. WL: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. XiW: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. YD: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. XuW: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. LZ: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82272306), the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2024MH180 and ZR2024MH017), the Taishan Scholars Program (tstp20221142), and the Joint Innovation Team for Clinical & Basic Research (202409).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1672518/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Cho CT Wenner HA . Monkeypox virus. Bacteriol Rev. (1973) 37:1–18. doi: 10.1128/br.37.1.1-18.1973,

2.

Ladnyj ID Ziegler P Kima E . A human infection caused by monkeypox virus in Basankusu territory, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Bull World Health Organ. (1972) 46:593–7.

3.

Heymann DL Szczeniowski M Esteves K . Re-emergence of monkeypox in Africa: a review of the past six years. Br Med Bull. (1998) 54:693–702. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011720,

4.

Yinka-Ogunleye A Aruna O Dalhat M Ogoina D McCollum A Disu Y et al . Outbreak of human monkeypox in Nigeria in 2017-18: a clinical and epidemiological report. Lancet Infect Dis. (2019) 19:872–9. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(19)30294-4,

5.

Gessain A Nakoune E Yazdanpanah Y . Monkeypox. N Engl J Med. (2022) 387:1783–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2208860,

6.

Harapan H Setiawan AM Yufika A Anwar S Wahyuni S Asrizal FW et al . Knowledge of human monkeypox viral infection among general practitioners: a cross-sectional study in Indonesia. Pathog Glob Health. (2020) 114:68–75. doi: 10.1080/20477724.2020.1743037,

7.

Sepehrinezhad A Ashayeri Ahmadabad R Sahab-Negah S . Monkeypox virus from neurological complications to neuroinvasive properties: current status and future perspectives. J Neurol. (2023) 270:101–8. doi: 10.1007/s00415-022-11339-w,

8.

Nakhaie M Pirmoradi Z Bashash D Rukerd MRZ Charostad J . Beyond skin deep: shedding light on the neuropsychiatric consequences of Monkeypox (Mpox). Acta Neurol Belg. (2024) 124:1189–97. doi: 10.1007/s13760-023-02361-4,

9.

Mitjà O Alemany A Marks M Lezama Mora JI Rodríguez-Aldama JC Torres Silva MS et al . Mpox in people with advanced HIV infection: a global case series. Lancet. (2023) 401:939–49. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(23)00273-8,

10.

Valcour V Chalermchai T Sailasuta N Marovich M Lerdlum S Suttichom D et al . Central nervous system viral invasion and inflammation during acute HIV infection. J Infect Dis. (2012) 206:275–82. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis326,

11.

Stang A . Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. (2010) 25:603–5. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z,

12.

Rostom A Dubé C Cranney A Saloojee N Sy R Garritty C et al . Celiac disease. Evid Rep Technol Assess. (2004) 104:1–6.

13.

Higgins JP Thompson SG Deeks JJ Altman DG . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. (2003) 327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

14.

Egger M Davey Smith G Schneider M Minder C . Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. (1997) 315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629,

15.

Alpalhão M Sousa D Frade JV Patrocínio J Garrido PM Correia C et al . Human immunodeficiency virus infection may be a contributing factor to monkeypox infection: analysis of a 42-case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2023) 88:720–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.09.029,

16.

Angelo KM Smith T Camprubí-Ferrer D Balerdi-Sarasola L Díaz Menéndez M Servera-Negre G et al . Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patients with monkeypox in the GeoSentinel network: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis. (2023) 23:196–206. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(22)00651-x,

17.

Caria J Pinto R Leal E Almeida V Cristóvão G Gonçalves AC et al . Clinical and epidemiological features of hospitalized and ambulatory patients with human Monkeypox infection: a retrospective observational study in Portugal. Infect Dis Rep. (2022) 14:810–23. doi: 10.3390/idr14060083,

18.

Chen C Wu W Peng L Cao M Feng S Li J et al . Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of monkeypox in Shenzhen. Electron J Emerg Infect Dis. (2023) 8:1–5. doi: 10.19871/j.cnki.xfcrbzz.2023.04.001

19.

Fu L Wang B Wu K Yang L Hong Z Wang Z et al . Epidemiological characteristics, clinical manifestations, and mental health status of human mpox cases: a multicenter cross-sectional study in China. J Med Virol. (2023) 95:e29198. doi: 10.1002/jmv.29198,

20.

Hoffmann C Jessen H Wyen C Grunwald S Noe S Teichmann J et al . Clinical characteristics of monkeypox virus infections among men with and without HIV: a large outbreak cohort in Germany. HIV Med. (2023) 24:389–97. doi: 10.1111/hiv.13378,

21.

Jun Y Zhongdong Z Dingyan Y Feng L Rongrong Z Jinchuan S et al . Clinical characteristics of monkeypox patients with HIV positive or HIV negative. Chin J Clin Infect Dis. (2023) 16:262–6. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-2397.2023.04.005

22.

Kim M Acevedo Martinez E Suárez Moscoso NP Niu J Abbo LM Rosa R et al . A retrospective study on 198 mpox cases in South Florida: clinical characteristics and outcomes with focus on human immunodeficiency virus status. Int J STD AIDS. (2023) 34:884–9. doi: 10.1177/09564624231185812,

23.

Kowalski J Cielniak I Garbacz-Łagożna E Cholewińska-Szymańska G Parczewski M . Comparison of clinical course of Mpox among HIV-negative and HIV-positive patients: a 2022 cohort of hospitalized patients in Central Europe. J Med Virol. (2023) 95:e29172. doi: 10.1002/jmv.29172,

24.

Maronese CA Ramoni S Avallone G Giacalone S Quattri E Gaspari V et al . Monkeypox: an Italian, multicentre study of 104 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2024) 38:e312–6. doi: 10.1111/jdv.19587,

25.

Núñez I García-Grimshaw M Ceballos-Liceaga SE Toledo-Salinas C Carbajal-Sandoval G Sosa-Laso L et al . Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patients with human monkeypox infection in Mexico: a nationwide observational study. Lancet Reg Health Am. (2023) 17:100392. doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2022.100392,

26.

Pilkington V Quinn K Campbell L Payne L Brady M Post FA . Clinical presentation of Mpox in people with and without HIV in the United Kingdom during the 2022 global outbreak. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. (2023) 39:581–6. doi: 10.1089/aid.2023.0014,

27.

Silva MST Coutinho C Torres TS Peixoto E Ismério R Lessa F et al . Ambulatory and hospitalized patients with suspected and confirmed mpox: an observational cohort study from Brazil. Lancet Reg Health Am. (2023) 17:100406. doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2022.100406,

28.

Zaqout A Daghfal J Munir W Abdelmajid A Albayat SS Abukhattab M et al . Clinical manifestations and outcome of Mpox infection in Qatar: an observational study during the 2022 outbreak. J Infect Public Health. (2023) 16:1802–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2023.09.001,

29.

Khan SA Parajuli SB Rauniyar VK . Neurological manifestations of an emerging zoonosis-human monkeypox virus: a systematic review. Medicine. (2023) 102:e34664. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000034664,

30.

Liu Q Fu L Wang B Sun Y Wu X Peng X et al . Clinical characteristics of human Mpox (Monkeypox) in 2022: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Pathogens. (2023) 12:146. doi: 10.3390/pathogens12010146,

31.

Miranzadeh Mahabadi H Lin YCJ Ogando NS Moussa EW Mohammadzadeh N Julien O et al . Monkeypox virus infection of human astrocytes causes gasdermin B cleavage and pyroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2024) 121:e2315653121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2315653121,

32.

Alissa M Alghamdi A Alghamdi SA . Overview of reemerging mpox infection with a focus on neurological manifestations. Rev Med Virol. (2024) 34:e2527. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2527,

33.

Billioux BJ Mbaya OT Sejvar J Nath A . Neurologic complications of smallpox and Monkeypox: a review. JAMA Neurol. (2022) 79:1180–6. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.3491,

34.

Nyame J Punniyakotti S Khera K Pal RS Varadarajan N Sharma P . Challenges in the treatment and prevention of monkeypox infection; a comprehensive review. Acta Trop. (2023) 245:106960. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2023.106960,

35.

Soltani S Shahbahrami R Jahanabadi S Siri G Emadi MS Zandi M . Possible role of CNS microRNAs in human Mpox virus encephalitis-a mini-review. J Neurovirol. (2023) 29:135–40. doi: 10.1007/s13365-023-01125-3,

Summary

Keywords

mpox, MPXV, central nervous system symptoms, meta-analysis, neurological manifestations

Citation

Luan J, Lv W, Wang X, Du Y, Wang X and Zhang L (2025) Central nervous system symptoms in mpox patients without HIV co-infection: a meta-analysis. Front. Med. 12:1672518. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1672518

Received

25 July 2025

Revised

27 October 2025

Accepted

18 November 2025

Published

09 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

U. K. Misra, Apollo Medics Super Speciality Hospital, India

Reviewed by

Debashis Dutta, University of Nebraska Medical Center, United States

Arnaud John Kombe Kombe, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Luan, Lv, Wang, Du, Wang and Zhang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Leiliang Zhang, armzhang@hotmail.com

†These authors share first authorship

ORCID: Leiliang Zhang, orcid.org/0000-0002-7015-9661

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.