Abstract

Objective:

As a core indicator of healthy aging, intrinsic capacity (IC) may be adversely impacted by polypharmacy. Leveraging data from the WHO Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE) pilot in China, this study examines the association between polypharmacy and IC decline in older adults, aiming to provide evidence-based insights for optimizing geriatric pharmacotherapy.

Methods:

A cross-sectional analysis was conducted using data from community-dwelling and institutionalized adults aged ≥60 years enrolled at the Lianyungang (LYG) pilot site of the WHO ICOPE China program. Medication histories, demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors, and chronic disease profiles were collected via structured questionnaires. The WHO ICOPE screening tool was employed to assess five IC domains: cognition, mobility, sensory function, nutrition, and psychology. Polypharmacy was defined as concurrent use of ≥5 medications. Multivariable logistic regression models evaluated the polypharmacy-IC decline association, with stratification analyses assessing subgroup heterogeneity.

Results:

The study enrolled 467 participants, comprising a polypharmacy cohort (≥5 medications, n = 33) and a non-polypharmacy cohort (n = 434). Mean IC score was 3.5 ± 1.5. In unadjusted analyses, polypharmacy is associated with greater odds of IC decline (OR = 2.81, 95% CI: 1.06–7.43, p = 0.037). This association persisted in Model 1 (demographic-adjusted: OR = 2.82, 95% CI: 1.05–7.56, p = 0.039), Model 2 (socioeconomic-adjusted: OR = 3.65, 95% CI: 1.33–9.98, p = 0.012), and Model 3 (functional/geriatric-adjusted: OR = 3.23, 95% CI: 1.13–9.28, p = 0.029). However, in the fully adjusted Model 4 (including comorbidities), the OR attenuated to 2.31 (95% CI: 0.77–6.88, p = 0.134), retaining a positive but non-significant association. After full covariate adjustment, each additional medication was associated with a 22% increase in the likelihood of IC decline (OR = 1.22, 95% CI: 1.01–1.47, p = 0.04). Patients with IC decline demonstrated significantly higher medication counts than those with preserved IC (p < 0.05). Stratified analyses confirmed stable associations across subgroups (all interaction p > 0.05).

Conclusion:

An increase in the number of medications used by older adults may be positively associated with a decline in intrinsic capacity (IC). The prevalence of IC decline is significantly higher among individuals taking ≥5 medications compared to those using fewer medications. These findings suggest that polypharmacy is associated with IC decline and could serve as a potential indicator for IC decline. Prospective studies are needed to validate the causal relationship.

1 Introduction

The acceleration of global population ageing has driven a paradigm shift in healthcare from disease-centred to function-centred models to address challenges of profound ageing. In its World Report on Ageing and Health, the World Health Organization (WHO) established “healthy ageing” as the development and maintenance of functional ability enabling wellbeing in older age. Within this framework, WHO introduced the innovative construct of “intrinsic capacity” (IC)—defined as the composite of an individual’s physical and mental attributes—encompassing five domains: cognition, mobility, psychological, sensory (vision and hearing), and vitality (1), this conceptual advance signifies a critical transition from pathology-focused to function-oriented care (2). Complementing this, WHO has issued the Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE) Guidelines, comprising the Manual: Person-Centered Assessment and Primary Care Pathway Guidelines, which establish standards for community interventions and clinical practice (3).

Over the past two decades, polypharmacy prevalence among older adults has risen substantially, emerging as a critical global public health challenge. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines polypharmacy as the concurrent use of five or more medications (4), evidence indicates that adverse drug reaction (ADR) incidence increases from 6% in older adults using two medications to 50% with five medications, approaching 100% when eight or more are administered (5). Among community-dwelling older adults, polypharmacy prevalence ranges from 4 to 86.6% (6), while in China, 66.4–75.3% exhibit impaired intrinsic capacity (7). These phenomena are mechanistically linked: approximately 69.1% of Chinese older adults experience decline in at least one intrinsic capacity domain (8), heightening vulnerability to polypharmacy. Notably, diminished intrinsic capacity constitutes a risk factor for potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) use in hospitalised elderly patients (9), IC decline and polypharmacy can accelerate functional decline, affect quality of life, and increase healthcare burden.

Polypharmacy poses a significant threat to the intrinsic capacity (IC) of older adults. This risk is primarily driven by the convergence of age-related pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) alterations (e.g., reduced clearance, altered drug distribution), drug–drug interactions (DDIs), and cumulative drug toxicities (e.g., anticholinergic/sedative burden). These mechanisms collectively heighten vulnerability to adverse drug reactions and functional impairment across multiple IC domains. Existing evidence has established associations between polypharmacy and specific health impairments, including functional decline (10), cognitive deficits (11), elevated fall risk (12), and adverse drug events (13). Nevertheless, the holistic impact of polypharmacy on IC—mediated through the aforementioned synergistic mechanisms, particularly the dose–response relationship—remains inadequately characterized. To address this knowledge gap, we utilized data from the WHO ICOPE pilot program in Lianyungang, China. We aimed to investigate the association between polypharmacy and comprehensive intrinsic capacity (IC) decline using the WHO ICOPE integrated assessment framework.

2 Methods

2.1 Data and population

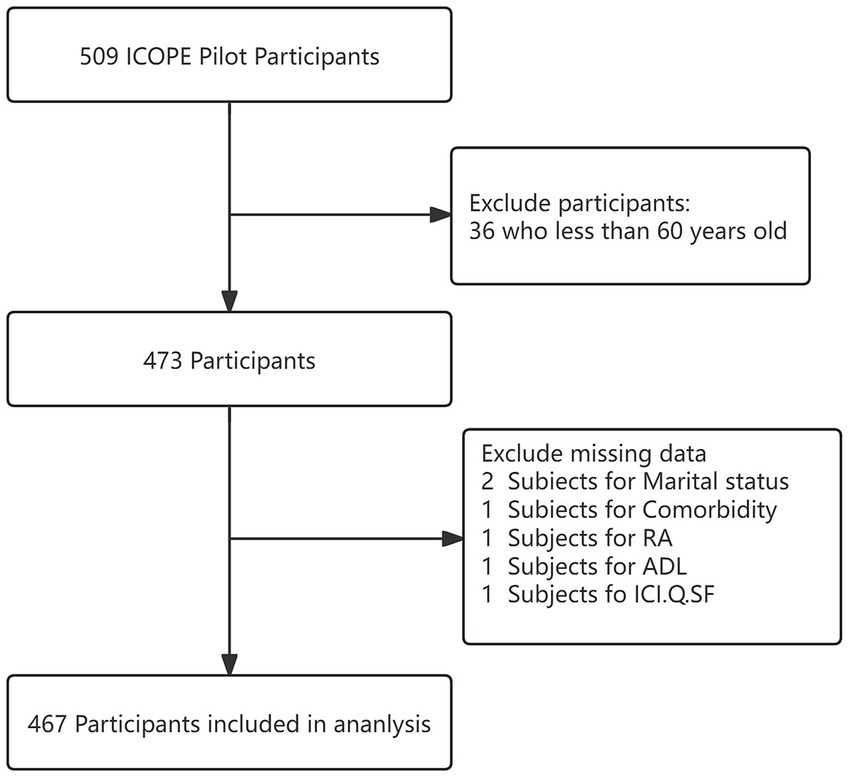

This cross-sectional analysis utilised data from the WHO Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE) pilot in Lianyungang City. Between March and April 2024, we enrolled adults aged ≥60 years residing locally for ≥6 months (community-dwelling and institutionalised populations) via convenience sampling at community health centres and long-term care facilities. Inclusion required: (1) baseline communication capacity for assessment completion; and (2) family member consent for participation support. Exclusion criteria comprised: (1) acute conditions necessitating urgent intervention; (2) incomplete baseline data; or (3) terminal illness with <6-month life expectancy. Of 509 screened participants, 467 met eligibility criteria and were analysed (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Flow chart of the study population.

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Lianyungang First People’s Hospital on December 9, 2022, with ethics number QT-20221118001-02. The study complied with STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines. Trained researchers administered pretested structured questionnaires using validated instruments. Rigorous quality control measures included: dual independent data entry, logic consistency validation, and outlier detection protocols throughout data collection.

2.2 Intrinsic capacity

Intrinsic capacity (IC) was assessed using the WHO ICOPE screening tool (3), comprising six domains: cognition, mobility, nutrition, vision, hearing, and psychological status. The reliability and validity of the tool have been well verified (14). Participants with positive initial screening results underwent further clinical evaluation. Cognition was quantified via the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; score range 0–30), with impairment thresholds adjusted for educational attainment: ≤17 for illiterate individuals, ≤20 for primary school education, ≤22 for middle school, and ≤23 for university-level education.

Mobility assessment employed the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), where scores ≤9 indicated impairment. Nutritional status was evaluated using the Mini Nutritional Assessment-Short Form (MNA-SF), defining malnutrition as MNA-SF scores ≤11 (15).

Those with positive results of visual acuity and hearing were further evaluated by comprehensive geriatric assessment tools commonly used by famous medical institutions in China (e.g., Peking Union Medical College Hospital and Beijing Geriatric Hospital). In-depth evaluation of visual acuity included the following: difficulty in reading/walking/watching TV, or occlusion or defect of vision, distortion of vision. A “no” score of 0 (good vision) was assigned for all three items, a “yes” score of 1 (poor vision) was assigned for 1–2 items, and a “yes” score of 2 (bad vision) was assigned for all three items. An in-depth hearing assessment includes the following questions: complaints about the volume of the television, the need for repetition, and difficulty listening to the phone. A “no” score for all three items was 0 (good hearing), a “yes” score for 1–2 items was 1 point (poor hearing), and a “yes” score for all three items was 2 points (bad hearing) (16).

According to the ICOPE guidelines (WHO, 2019) (17), the Psychological capacity dimension focuses on managing depressive symptoms. Its screening criteria are clear: If an individual has experienced any of the symptoms of “feeling down,” “feeling depressed,” “feeling hopeless” or “lack of interest/pleasure” in the past two weeks, they can be defined as having depressive symptoms.

Calculation of composite IC score: A composite IC score (range: 0–8) was derived by summing the scores assigned to each of the six domains. Cognition, mobility, nutrition, and psychological status (depressive symptoms) were scored dichotomously (0 = no impairment, 1 = impairment). Vision and hearing were scored on a three-level scale (0 = good, 1 = moderate impairment, 2 = severe impairment). IC decline (DIC) was defined as a composite score ≥ 2, while scores <2 denoted normal IC (non-DIC).

2.3 Polypharmacy

Polypharmacy is defined as the prescription of five or more different medications taken daily. The types of medications included in polypharmacy encompass both prescription and over-the-counter drugs (18), while herbal remedies and supplements were excluded. During the baseline survey, the number of medications taken by patients was assessed by asking, “What medications have you been taking daily for the past three months?” to gather information on their recent medication use.

2.4 Covariates

Key sociodemographic and clinical covariates were adjusted for in the analyses. Sociodemographic factors encompassed: age (<80 vs. ≥80 years), marital status (married/unmarried), educational attainment (illiterate/primary school vs. ≥junior high school), residential setting (urban/suburban), nursing home residence (yes/no), and caregiver availability (yes/no). Clinical covariates incorporated frailty status, social functioning (assessed via Social Participation Frequency, SPF), basic activities of daily living (ADL), urinary incontinence (UI), and Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) scores.

Frailty was assessed using the K-FRAIL scale (19), comprising five criteria: fatigue, resistance, ambulation, illnesses, and weight loss (20). Each criterion was scored dichotomously (0/1), with total scores categorised as: robust (0), pre-frail (1–2), or frail (≥3).

Social Participation Function (SPF) was evaluated through a validated instrument assessing five domains (21): appropriate social adaptation (score 0), adaptation to simple environments with undetectable cognitive issues at initial contact (score 1), social withdrawal with passive interaction, impaired initiation, and inappropriate remarks increasing deception vulnerability (score 2), limited interactions with unclear speech/inappropriate expressions (score 3), markedly impaired social engagement (score 4), total SPF scores defined functional levels: intact (0–2), mild (3–7), moderate (8–13), or severe impairment (14–20).

Activities of daily living (ADL) were measured using the modified Barthel index (MBI; range 0–100), classifying dependency as: complete independence (100), mild (91–99), moderate (61–90), severe (21–60), or total dependence (≤20).

The International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI SF) assesses the severity of urinary incontinence (UI) symptoms. It comprises three questions: Question 1 quantifies the frequency of urine leakage, Question 2 evaluates the amount of leakage, and Question 3 measures the impact of UI on daily life. The total ICIQ score ranges from 0 to 21. A score of 0 indicates no incontinence; 1–5: mild incontinence; 6–12: moderate incontinence; 13–21: severe incontinence (22).

Comorbidity burden was quantified using the Charlson comorbidity index and Cumulative Illness Rating Scale-Geriatrics (CIRS-G), supplemented by clinical expertise. Seventeen disease categories (e.g., myocardial infarction, chronic pulmonary disease, malignancies) were graded 1–6 based on severity. Total scores ≥1 indicated comorbidity presence, with higher scores reflecting greater burden (0 = no comorbidity) (23).

2.5 Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics characterised baseline participant characteristics: normally distributed continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation (SD), non-normally distributed variables as median (interquartile range, IQR), and categorical variables as frequency (percentage). Group comparisons used independent samples t-tests or Mann–Whitney U tests for continuous variables, and χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables.

Multivariable logistic regression examined polypharmacy (≥5 medications)-intrinsic capacity (IC) associations. To address confounding and validate robustness, covariates were selected through: univariate analysis with p < 0.05 (Supplementary Table 1); ≥10% change-in-estimate criterion; clinically relevant variables per expert consensus. Four adjusted models generated odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs. Subgroup analyses assessed associations across strata. We employed the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis H test to compare differences in medication counts among the high-, medium-, and low-level intrinsic capability (IC) groups. Given minimal missing data (0–6%), case deletion was applied. All analyses were conducted using the statistical software packages R (http://www.r-project.org, The R Foundation) and Free Statistics software versions, with a two-sided p-value <0.05 considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Patient characteristics

The cohort comprised 467 older adults (Figure 1), stratified into non-polypharmacy (<5 medications, n = 434) and polypharmacy (≥5 medications, n = 33) groups. The prevalence of DIC was 67.9% (317/467). Compared with the non-polypharmacy group, the polypharmacy group demonstrated significantly higher proportions of comorbidities, frailty, urban residency, vision disorder and married status (p < 0.05; Table 1). IC scores were marginally elevated in polypharmacy users (mean ± SD: 4.0 ± 1.5 vs. 3.5 ± 1.5; p = 0.054), with significantly increased incidence of IC decline (84.8% vs. 66.6%; p = 0.03). No significant intergroup differences were observed in: sex distribution, age stratification, BMI, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores, malnutrition, depression, SPF, sleep quality, and ADL levels (all p > 0.05).

Table 1

| Variables | Total (n = 467) | Number of medications | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <5 (n = 434) | ≥5 (n = 33) | |||

| IC, mean ± SD | 3.5 ± 1.5 | 3.5 ± 1.5 | 4.0 ± 1.5 | 0.054 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.21 | |||

| Male | 206 (44.1) | 188 (43.3) | 18 (54.5) | |

| Female | 261 (55.9) | 246 (56.7) | 15 (45.5) | |

| Age, n (%) | 0.208 | |||

| <80 years | 190 (40.7) | 180 (41.5) | 10 (30.3) | |

| ≥80 years | 277 (59.3) | 254 (58.5) | 23 (69.7) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) mean ± SD | 25.0 ± 5.6 | 25.0 ± 5.5 | 25.3 ± 6.7 | 0.742 |

| Comorbidity, median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.0, 3.0) | 1.0 (0.0, 2.0) | 4.0 (1.0, 7.0) | < 0.001 |

| ICIQ-SF, n (%) | 0.056 | |||

| No | 361 (77.3) | 340 (78.3) | 21 (63.6) | |

| Mild | 48 (10.3) | 40 (9.2) | 8 (24.2) | |

| Moderate | 34 (7.3) | 31 (7.1) | 3 (9.1) | |

| Severe | 24 (5.1) | 23 (5.3) | 1 (3) | |

| Frail, n (%) | 0.001 | |||

| No | 380 (81.4) | 360 (82.9) | 20 (60.6) | |

| Yes | 87 (18.6) | 74 (17.1) | 13 (39.4) | |

| Education, n (%) | 0.07 | |||

| Illiterate | 158 (33.8) | 150 (34.6) | 8 (24.2) | |

| Primary school | 141 (30.2) | 134 (30.9) | 7 (21.2) | |

| Junior high school and above | 168 (36.0) | 150 (34.6) | 18 (54.5) | |

| Residential area (RA), n (%) | 0.004 | |||

| Suburban | 163 (34.9) | 159 (36.6) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Urban | 304 (65.1) | 275 (63.4) | 29 (87.9) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.045 | |||

| Married | 247 (52.9) | 224 (51.6) | 23 (69.7) | |

| Unmarried | 220 (47.1) | 210 (48.4) | 10 (30.3) | |

| Nursing home, n (%) | 0.247 | |||

| No | 252 (54.0) | 231 (53.2) | 21 (63.6) | |

| Yes | 215 (46.0) | 203 (46.8) | 12 (36.4) | |

| MMSE, n (%) | 0.245 | |||

| No | 341 (73.2) | 314 (72.5) | 27 (81.8) | |

| Yes | 125 (26.8) | 119 (27.5) | 6 (18.2) | |

| Malnutrition, n (%) | 0.109 | |||

| No | 403 (86.3) | 378 (87.1) | 25 (75.8) | |

| Yes | 64 (13.7) | 56 (12.9) | 8 (24.2) | |

| Depression, n (%) | 0.111 | |||

| No | 17 (3.6) | 14 (3.2) | 3 (9.1) | |

| Yes | 450 (96.4) | 420 (96.8) | 30 (90.9) | |

| SPPB, n (%) | 0.075 | |||

| No | 355 (76.3) | 334 (77.3) | 21 (63.6) | |

| Yes | 110 (23.7) | 98 (22.7) | 12 (36.4) | |

| Vision, n (%) | 0.001 | |||

| Good | 333 (71.3) | 319 (73.5) | 14 (42.4) | |

| Moderate | 94 (20.1) | 80 (18.4) | 14 (42.4) | |

| Poor | 40 (8.6) | 35 (8.1) | 5 (15.2) | |

| Hearing, n (%) | 0.891 | |||

| Good | 310 (66.4) | 289 (66.6) | 21 (63.6) | |

| Moderate | 52 (11.1) | 48 (11.1) | 4 (12.1) | |

| Poor | 105 (22.5) | 97 (22.4) | 8 (24.2) | |

| SPF, n (%) | 0.159 | |||

| No impairments | 382 (81.8) | 352 (81.1) | 30 (90.9) | |

| Impairments | 85 (18.2) | 82 (18.9) | 3 (9.1) | |

| Sleep, n (%) | 0.213 | |||

| No impairments | 390 (83.5) | 365 (84.1) | 25 (75.8) | |

| Impairments | 77 (16.5) | 69 (15.9) | 8 (24.2) | |

| ADL, n (%) | 0.15 | |||

| High level | 334 (71.5) | 314 (72.4) | 20 (60.6) | |

| Low level | 133 (28.5) | 120 (27.6) | 13 (39.4) | |

| DIC, n (%) | 0.03 | |||

| No | 150 (32.1) | 145 (33.4) | 5 (15.2) | |

| Yes | 317 (67.9) | 289 (66.6) | 28 (84.8) | |

Characteristics of the older participants.

IC, intrinsic capacity; DIC, decreased intrinsic capacity; BMI, body mass index; ICIQ-SF, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form; RA, residential area; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MNA-SF, Mini Nutritional Assessment-Short Form; SPF, Social Participation Function; ADL, activities of daily living.

3.2 The association between polypharmacy and intrinsic capacity

Table 2 presents the multivariable regression analyses, which indicate a positive association between the number of medications and decline in intrinsic capacity (IC). When treated as a continuous variable, each additional medication was associated with greater odds of IC decline in the crude model (OR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.10–1.52, p = 0.002). After sequential adjustment for demographic characteristics (Model 1: OR = 1.28, 95% CI: 1.09–1.51, p = 0.003), socioeconomic factors (Model 2: OR = 1.36, 95% CI: 1.15–1.62, p < 0.001), functional status indicators (Model 3: OR = 1.30, 95% CI: 1.08–1.55, p = 0.005), and comorbidities (Model 4: OR = 1.22, 95% CI: 1.01–1.47, p = 0.04), these associations remained statistically significant.

Table 2

| Variable | N = 467 | Crude model | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Number of medications | 467 | 1.29 (1.09–1.51) | 0.002 | 1.28 (1.09–1.51) | 0.003 | 1.36 (1.15–1.62) | <0.001 | 1.3 (1.08–1.55) | 0.005 | 1.22 (1.01–1.47) | 0.04 |

| Number of medications | |||||||||||

| <5 | 434 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | |||||

| ≥5 | 33 | 2.81 (1.06–7.43) | 0.037 | 2.82 (1.05–7.56) | 0.039 | 3.65 (1.33–9.98) | 0.012 | 3.23 (1.13–9.28) | 0.029 | 2.31 (0.77–6.88) | 0.134 |

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of the association between intrinsic capacity and polypharmacy.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Crude model: unadjusted.

Model 1: Gender, age, BMI.

Model 2: Gender, age, BMI, marital, residential area, education.

Model 3: Gender, age, BMI, marital, residential area, education, nursing home, ADL, SPF, ICIQ-SF, frail.

Model 4: Gender, age, BMI, marital, residential area, education, nursing home, ADL, SPF, ICIQ-SF, frail, comorbidity.

When stratified by medication threshold (with <5 medications as the reference group), polypharmacy (≥5 medications) was significantly associated with a decline in intrinsic capacity (IC) in the unadjusted model (OR = 2.81, 95% CI: 1.06–7.43, p = 0.037). This association was maintained in Model 1 (OR = 2.82, 95% CI: 1.05–7.56, p = 0.039) and further amplified in Model 2 (OR = 3.65, 95% CI: 1.33–9.98, p = 0.012). However, in Model 4, after adjusting for comorbidities, the odds ratio decreased to 2.31 (95% CI: 0.77–6.88, p = 0.134), no longer reaching statistical significance.

In Supplementary Table 2, we demonstrated a significant association between medication burden and vision impairment. Each additional medication increased the odds of vision impairment by 43% (OR = 1.43, 95% CI: 1.24–1.63, p < 0.001). Likewise, polypharmacy was significantly associated with elevated odds of vision impairment (OR = 3.76, 95% CI: 1.83–7.75, p < 0.001). Concurrently, a positive trend was observed between increasing medication count and impairments in locomotion, nutritional risk, and hearing, although these associations failed to reach statistical significance.

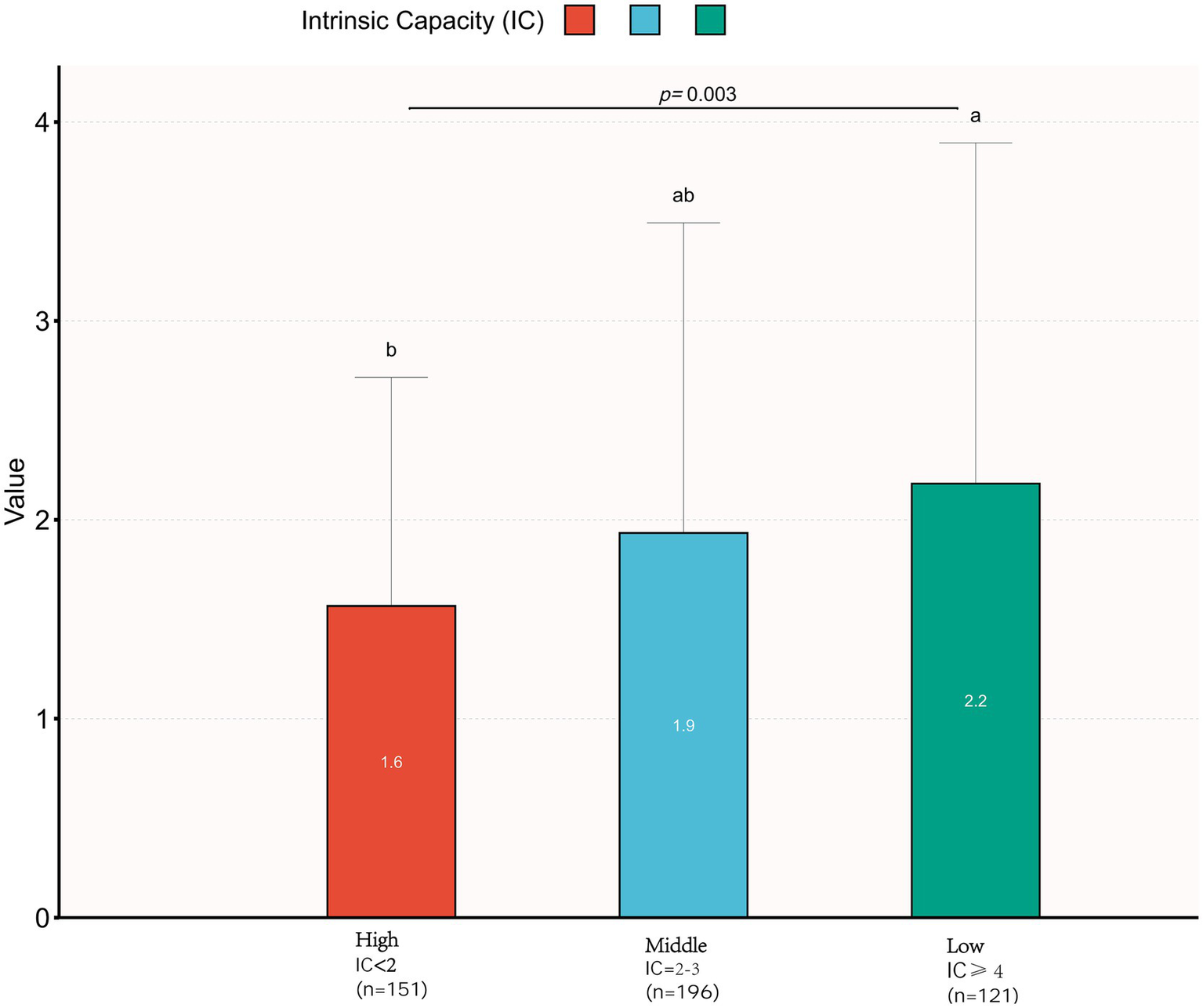

Figure 2 demonstrates significant differences in the distribution of medication numbers among different intrinsic capacity (IC) level groups (Kruskal–Wallis H = 12.80, p < 0.05). The high IC group (<2 points) had the lowest median number of medications (1.6), followed by the medium IC group (2–3 points) with 1.9 medications, and the low IC group (≥4 points) had the highest (2.2 medications), demonstrating an increasing trend in medication numbers with decreasing IC levels.

Figure 2

Comparison of number of medications across intrinsic capability (IC) levels. A statistically significant difference in medication counts was observed among IC-level groups (Kruskal–Wallis H test: H = 12.801). Groups marked with different superscript letters denote significant pairwise differences based on Dunn’s post hoc test with Bonferroni correction (p < 0.05).

3.3 Subgroup analyses

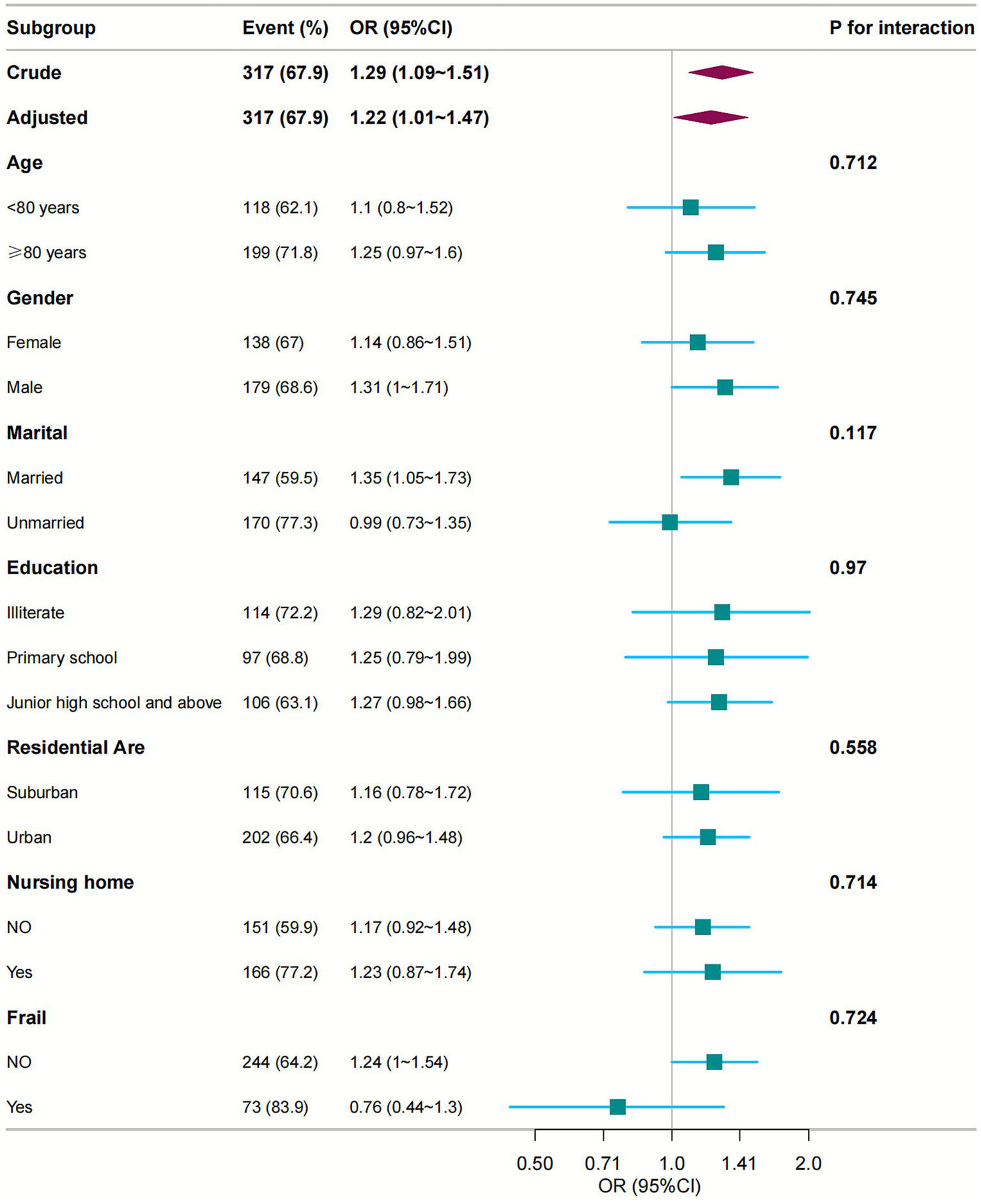

We conducted subgroup analyses to evaluate potential effect modifiers in the medication count-diminished intrinsic capacity association. Participants were stratified by age (<80 vs. ≥80 years), sex (female/male), marital status (married/unmarried), education level, residential area, and institutional care status. Forest plots were generated to visualise trend consistency across strata. Notably, no significant interaction effects were detected for any subgroup variable (all interaction p-values >0.05; Figure 3).

Figure 3

Subgroup analyses of the relationship between number of medications and intrinsic capacity. Odds ratios were adjusted for variables as in Model 4 (Table 2) except for the corresponding stratification variable. CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratios.

4 Discussion

This study utilized data from the World Health Organization (WHO) Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE) pilot program in China to investigate the association between polypharmacy and intrinsic capacity (IC) in older adults. The findings revealed that: each additional medication was associated with a 22% increased likelihood of decline in intrinsic capacity. Notably, polypharmacy (≥5 medications) was significantly associated with a higher prevalence of IC decline (84.8% vs. 66.6%). Older adults with lower IC levels had a higher average number of medications (see Figure 2). Subgroup analyses systematically evaluated effect modification across different demographic subgroups. The robust positive association between polypharmacy and IC impairment remained consistent across all subgroups (p for interaction >0.05), indicating significant population generalizability of this association. These observations are consistent with existing evidence. Previous studies have identified five distinct patterns of intrinsic capacity impairment, among which “depression with cognitive impairment” and “pan-domain impairment” are strongly associated with excessive polypharmacy (1), this indicates that polypharmacy exacerbates IC decline and increases the risk of adverse health outcomes (24).

Our investigation detected diminished intrinsic capacity (IC) in 67.9% of elderly participants, consistent with worldwide patterns. Chinese research involving 376 seniors recorded 69.1% exhibiting ≥1 affected IC domain (8). Parallel findings emerged from a WHO-associated French center, where the 9-item ICOPE screen revealed 92.6% IC impairment prevalence among 755 older adults (25). Cumulatively, these outcomes confirm compromised IC as a widespread geriatric condition. Significantly, research on Chinese subjects aged ≥50 years initially indicated poorer IC in polypharmacy recipients, although age adjustment nullified this correlation statistically (7). Such inconsistency potentially stems from age-medication collinearity: progressive aging typically heightens multimorbidity probability, thereby augmenting polypharmacy likelihood. To resolve this, we performed stratified age analyses (<80 versus ≥80 years). Outcomes verified markedly increased IC deterioration in octogenarians. Crucially, age-adjusted models maintained statistically significant polypharmacy-IC links, positioning medication overload as an autonomous predictor of IC deterioration irrespective of biological aging.

Progressive aging increases susceptibility to chronic disorders and geriatric syndromes in older adults, frequently requiring multidrug regimens for symptom control. For instance, a US meta-analysis documented significantly higher polypharmacy prevalence among individuals aged ≥65 years compared with younger populations (26). Indicating extensive medication burden in senescence. While polypharmacy inherently reflects comorbid disease presence, it may also directly compromise intrinsic capacity through pharmacological mechanisms. Notably, our analysis observed marked attenuation of the polypharmacy-intrinsic capacity association following comorbidity adjustment in Model 4. This attenuation likely reflects multicollinearity between medication burden and comorbidity measures. Although Yoshida et al. (10) detected no significant multimorbidity-polypharmacy interaction effect on physical function, polypharmacy remains plausible to accelerate functional deterioration through drug–drug interactions and drug-disease incompatibilities. Future research using longitudinal designs is needed to disentangle their independent effects on functional decline.

Beyond comorbidity influences, polypharmacy subgroups demonstrated higher proportions of metropolitan dwellers and married individuals. Urban populations typically exhibit enhanced health consciousness and financial capacity, compounded by greater healthcare resource availability in cities, collectively facilitating improved medical access. These determinants synergistically promote medication intensification among urban residents. Concurrently, marital status provides spousal engagement and socio-emotional support, potentially fostering proactive health monitoring and prompt healthcare-seeking behaviour (27). Consequently, urban residency and marital union emerge as salient contributing factors to polypharmacy patterns.

Studies indicate that polypharmacy is strongly associated with impaired intrinsic capacity (IC) and geriatric syndromes, including frailty, cognitive decline, and falls (28, 29). Evidence suggests a bidirectional relationship wherein polypharmacy exacerbates frailty and functional decline (30). While multimorbidity-driven therapeutic complexity perpetuates medication overload. Notably, regimens involving ≥5 medications are linked to significantly higher risks of frailty (2.5-fold) (31), mobility impairment, and mortality (29, 30), whereas limited regimens (1–4 drugs) may exert protective effects (10). Our analysis demonstrates a clinically significant association between pharmacological burden and visual impairment, with each additional medication conferring a 43% increased odds of vision loss. Notably, commonly prescribed drug classes—including anticholinergics, corticosteroids, and psychoactive agents—may induce cataract formation, glaucoma progression, or retinal toxicity (32). Vision loss functionally compromises activities of daily living (ADL) (33), thereby accelerating intrinsic capacity (IC) decline. Critically, as visual function constitutes a core IC component within the WHO Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE) framework, its impairment directly diminishes global IC scores. These findings collectively underscore the detrimental impact of polypharmacy on physical function and intrinsic capacity (34, 35). The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying polypharmacy-induced IC impairment may stem from drug–drug interactions, cumulative adverse effects (e.g., anticholinergic burden) (36, 37), and age-related pharmacokinetic decline (38, 39). Though this complex relationship remains incompletely elucidated.

To mitigate the adverse effects of polypharmacy on the intrinsic capacity (IC) of older adults, we recommend establishing a structured, community-based, multidisciplinary management pathway (8). This pathway should actively engage physicians and nurses, clinical pharmacists, nutritionists, psychologists, and rehabilitation therapists by: implementing Electronic Health Record (EHR) alerts during clinical consultations to flag polypharmacy; integrating polypharmacy management into the training curricula of relevant healthcare professionals. We have identified polypharmacy as a significant and dose-dependent risk marker, making it a practical lever for intervention. During the initial stages of ICOPE screening, priority should be given to individuals taking five or more medications for comprehensive medication reviews and in-depth assessments, leading to the development of personalized care plans that include deprescribing strategies and medication optimization. This integrated approach, combining ICOPE integration, clearly defined multidisciplinary pathways, and targeted policy interventions, aims to optimize medication use and preserve intrinsic capacity in the older population.

4.1 Limitations

Methodological strengths of this study include its integration with the World Health Organization (WHO) Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE) pilot program. By rigorously adhering to the ICOPE protocol and including both community-dwelling and nursing home residents, we established a dose–response relationship between the number of medications and intrinsic capacity (IC). However, the following limitations should be noted. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inference regarding the relationship between polypharmacy and IC. Due to the post-hoc nature of the subgroup analyses, the relatively small sample size in the polypharmacy subgroup limited the statistical power of some analyses, and the results warrant cautious interpretation. Potential multicollinearity among covariates (such as comorbidity burden) may have been present; the observed effect of polypharmacy was attenuated after adjusting for comorbidities in the multivariate regression analysis. Furthermore, reliance on self-reported medication data (susceptible to recall bias) and the lack of prescription details (e.g., drug classes, potentially inappropriate medications) may have influenced the findings. Although we adjusted for key covariates including age, comorbidities, and functional status, the potential impact of unmeasured confounders must be considered. Factors such as social support, lifestyle and diet, and medication adherence could concurrently influence both prescribing patterns and IC trajectories (40). Future research should employ multi-center, prospective, large-sample cohort designs, incorporate a broader range of variables, and track IC trajectories over time to further elucidate the causal relationship and underlying mechanisms between polypharmacy and intrinsic capacity.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, based on the analysis of WHO ICOPE pilot data from China, increased medication burden appears associated with declining intrinsic capacity (IC) in older adults. Individuals with polypharmacy (≥5 medications) exhibited higher prevalence of IC deterioration, suggesting that polypharmacy may be associated with IC decline and could serve as an indicator for IC decline. These findings underscore the necessity of addressing polypharmacy risks in comprehensive care for older adults. Future validation studies should integrate medication categories with longitudinal tracking of intrinsic capacity functional trajectories.

Statements

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: the datasets generated during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to YD, dylzu_lnyx@163.com.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol (“Clinical Application of Integrated Care for the Elderly People in Geriatrics and Guidance for the Establishment of a Continuous Elderly Care Service System,” Grant No. QT-20221118001-02) was reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of The First People’s Hospital of Lianyungang on December 9, 2022. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

XY: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft. JW: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. AG: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. ZG: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. QS: Project administration, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JX: Visualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. QJ: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. YD: Supervision, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the 2025 Lianyungang Science & Technology Program (Clinical Application of Foreign-Expert-Guided Integrated Care for Older People in the Department of Geriatrics, Grant No. WZ2501), the 2025 National Standardization Pilot Project (Health and Wellness Field) (the Standardization Pilot Project for Integrated Elderly Care at the First People's Hospital of Lianyungang, Jiangsu Province, Grant No. 2025203-WJ-32), the 2023 Lianyungang Health Science and Technology Project (a prospective randomized controlled study on improving the comprehensive assessment of frail elderly people based on a national multi?center integrated elderly care pilot, Grant No. 202307), and the Pilot Project of WHO Integrated Care for Older People in China (National Multi-center Medical and Nursing Integrated Care Pilot).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the study participants and clinical staff for their support and contribution to this project. 2025 Lianyungang Science & Technology Program (Clinical Application of Foreign-Expert-Guided Integrated Care for Older People in the Department of Geriatrics). Measurement tool copyright statement: An unauthorized version of the Chinese MMSE was used by the study team without permission, however this has now been rectified with PAR. The MMSE is a copyrighted instrument and may not be used or reproduced in whole or in part, in any form or language, or by any means without written permission of PAR (www.parinc.com).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1673885/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Meng L-C Hsiao F-Y Huang S-T Lu W-H Peng L-N Chen L-K . Intrinsic capacity impairment patterns and their associations with unfavorable medication utilization: a nationwide population-based study of 37,993 community-dwelling older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. (2022) 26:918–25. doi: 10.1007/s12603-022-1847-z,

2.

Cesari M Araujo de Carvalho I Amuthavalli Thiyagarajan J Cooper C Martin FC Reginster J-Y et al . Evidence for the domains supporting the construct of intrinsic capacity. J Gerontol A. (2018) 73:1653–60. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gly011,

3.

Lu F Li J Liu X Liu S Sun X Wang X . Diagnostic performance analysis of the integrated care for older people (ICOPE) screening tool for identifying decline in intrinsic capacity. BMC Geriatr. (2023) 23:509. doi: 10.1186/s12877-023-04180-x,

4.

Varghese D Ishida C Patel P Haseer KH . Polypharmacy In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing (2024)

5.

Pei R . Analysis of the relationship of polypharmacy with frailty in elderly patients with chronic diseases in community hospitals. Qinhuangdao: North China University of Science and Technology (2021).

6.

Nicholson K Liu W Fitzpatrick D Hardacre KA Roberts S Salerno J et al . Prevalence of multimorbidity and polypharmacy among adults and older adults: a systematic review. Lancet Healthy Longev. (2024) 5:e287–96. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(24)00007-2,

7.

Leung AYM Su JJ Lee ESH Fung JTS Molassiotis A . Intrinsic capacity of older people in the community using WHO Integrated Care for Older People (ICOPE) framework: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. (2022) 22:304. doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-02980-1,

8.

Ma L Chhetri JK Zhang Y Liu P Chen Y Li Y et al . Integrated Care for Older People screening tool for measuring intrinsic capacity: preliminary findings from ICOPE pilot in China. Front Med. (2020) 7:576079. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.576079,

9.

Zhang Y Wang J Shen H . Correlation between potentially inappropriate medication and decline of intrinsic capacity in elderly inpatients. Chin Mult Organ Dis Elderly. (2024) 23:111. doi: 10.11915/j.issn.1671-5403.2024.07.111

10.

Yoshida Y Ishizaki T Masui Y Miura Y Matsumoto K Nakagawa T et al . Effects of multimorbidity and polypharmacy on physical function in community-dwelling older adults: a 3-year prospective cohort study from the SONIC. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. (2024) 126:105521. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2024.105521,

11.

Borda MG Castellanos-Perilla N Tovar-Rios DA Oesterhus R Soennesyn H Aarsland D . Polypharmacy is associated with functional decline in Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body dementia. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. (2021) 96:104459. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2021.104459,

12.

Dhalwani NN Fahami R Sathanapally H Seidu S Davies MJ Khunti K . Association between polypharmacy and falls in older adults: a longitudinal study from England. BMJ Open. (2017) 7:e016358. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016358,

13.

Matsumoto A Yoshimura Y Nagano F Bise T Kido Y Shimazu S et al . Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medications in stroke rehabilitation: prevalence and association with outcomes. Int J Clin Pharm. (2022) 44:749–61. doi: 10.1007/s11096-022-01416-5,

14.

George PP Lun P Ong SP Lim WS . A rapid review of the measurement of intrinsic capacity in older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. (2021) 25:774–82. doi: 10.1007/s12603-021-1622-6,

15.

Ma Y-C Ju Y-M Cao M-Y Yang D Zhang K-X Liang H et al . Exploring the relationship between malnutrition and the systemic immune-inflammation index in older inpatients: a study based on comprehensive geriatric assessment. BMC Geriatr. (2024) 24:19. doi: 10.1186/s12877-023-04604-8,

16.

Yu R Leung G Leung J Cheng C Kong S Tam LY et al . Prevalence and distribution of intrinsic capacity and its associations with health outcomes in older people: the jockey club community eHealth care project in Hong Kong. J Frailty Aging. (2022) 11:302–8. doi: 10.14283/jfa.2022.19,

17.

WHO . Integrated care for older people (ICOPE): guidance for person-centred assessment and pathways in primary care. Geneva: World Health Organization (2019).

18.

Halli-Tierney AD Scarbrough C Carroll D . Polypharmacy: evaluating risks and deprescribing. Am Fam Physician. (2019) 100:32–8.

19.

Jung H-W Yoo H-J Park S-Y Kim S-W Choi J-Y Yoon S-J et al . The Korean version of the FRAIL scale: clinical feasibility and validity of assessing the frailty status of Korean elderly. Korean J Intern Med. (2016) 31:594–600. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2014.331,

20.

Lee D Cho I Kwak D . Comparison of the frailty phenotype and the Korean version of the FRAIL scale. Healthcare. (2025) 13:1352. doi: 10.3390/healthcare13111352,

21.

Xu X-Y . Aging prevention and social work intervention: social participation of the elderly from the perspective of active aging. Soc Work Manag. (2019) 19:52–60. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-623X.2019.05.007

22.

Grøn Jensen LC Boie S Axelsen S . International consultation on incontinence questionnaire—urinary incontinence short form ICIQ-UI SF: validation of its use in a Danish speaking population of municipal employees. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0266479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0266479,

23.

Wei X Huang X Zhang Y Zhu L Shen H Xie Y . Charlson comorbidity index and health-related quality of life in middle-aged and elderly osteoporosis patients. Chin J Orthop Traumatol. (2023) 36:145–50. doi: 10.12200/j.issn.1003-0034.2023.02.010

24.

Chang Y-H Hung C-C Chiang Y-Y Chen C-Y Liao L-C Ma MH-M et al . Effects of osteoporosis treatment and multicomponent integrated care on intrinsic capacity and happiness among rural community-dwelling older adults: the Healthy Longevity and Ageing in Place (HOPE) randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. (2025) 54:afaf017. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaf017,

25.

Tavassoli N Piau A Berbon C De Kerimel J Lafont C De Souto Barreto P et al . Framework implementation of the INSPIRE ICOPE-CARE program in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO) in the Occitania region. J Frailty Aging. (2021) 10:103–9. doi: 10.14283/jfa.2020.26,

26.

Young EH Pan S Yap AG Reveles KR Bhakta K . Polypharmacy prevalence in older adults seen in United States physician offices from 2009 to 2016. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0255642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255642,

27.

Xiong S Peoples N Østbye T Olsen M Zhong X Wainaina C et al . Family support and medication adherence among residents with hypertension in informal settlements of Nairobi, Kenya: a mixed-method study. J Hum Hypertens. (2022) 37:74–9. doi: 10.1038/s41371-022-00656-2,

28.

Mehta RS Kochar BD Kennelty K Ernst ME Chan AT . Emerging approaches to polypharmacy among older adults. Nat Aging. (2021) 1:347–56. doi: 10.1038/s43587-021-00045-3,

29.

Liu Y Huang L Hu F Zhang X . Investigating frailty, polypharmacy, malnutrition, chronic conditions, and quality of life in older adults: large population-based study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. (2024) 10:e50617. doi: 10.2196/50617,

30.

Bolina AF Gomes NC Marchiori GF Pegorari MS Tavares DMDS . Potentially inappropriate medication use and frailty phenotype among community-dwelling older adults: a population-based study. J Clin Nurs. (2019) 28:3914–22. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14976,

31.

Liu X Zhao R Zhou X Yu M Zhang X Wen X et al . Association between polypharmacy and 2-year outcomes among Chinese older inpatients: a multi-center cohort study. BMC Geriatr. (2024) 24:748. doi: 10.1186/s12877-024-05340-3,

32.

Li J Tripathi RC Tripathi BJ . Drug-induced ocular disorders. Drug Saf. (2008) 31:127–41. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200831020-00003,

33.

Xu XJ Tan MP . Anticholinergics and falls in older adults. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. (2022) 15:285–94. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2022.2070474,

34.

Manias E Soh CH Kabir MZ Reijnierse EM Maier AB . Associations between inappropriate medication use and (instrumental) activities of daily living in geriatric rehabilitation inpatients: RESORT study. Aging Clin Exp Res. (2022) 34:445–54. doi: 10.1007/s40520-021-01946-4,

35.

Martins GA de Assis Acurcio F do Carmo Castro Franceschini S Priore SE Ribeiro AQ . Use of potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly in Viçosa, Minas Gerais State, Brazil: a population-based survey. Cad Saude Publica. (2015) 31:2401–12. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00128214

36.

Du L Koscik RL Chin NA Bratzke LC Cody K Erickson CM et al . Prescription medications and co-morbidities in late middle-age are associated with greater cognitive declines: results from WRAP. Front Aging. (2021) 2:759695. doi: 10.3389/fragi.2021.759695,

37.

Alhumaidi RM Bamagous GA Alsanosi SM Alqashqari HS Qadhi RS Alhindi YZ et al . Risk of polypharmacy and its outcome in terms of drug interaction in an elderly population: a retrospective cross-sectional study. J Clin Med. (2023) 12:3960. doi: 10.3390/jcm12123960,

38.

Verde Z García de Diego L Chicharro LM Bandrés F Velasco V Mingo T et al . Physical performance and quality of life in older adults: is there any association between them and potential drug interactions in polymedicated octogenarians. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:4190. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16214190,

39.

Zazzara MB Palmer K Vetrano DL Carfì A Onder G . Adverse drug reactions in older adults: a narrative review of the literature. Eur Geriatr Med. (2021) 12:463–73. doi: 10.1007/s41999-021-00481-9,

40.

Ma L Chhetri JK Zhang L Sun F Li Y Tang Z . Cross-sectional study examining the status of intrinsic capacity decline in community-dwelling older adults in China: prevalence, associated factors and implications for clinical care. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e043062. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043062,

Summary

Keywords

polypharmacy, intrinsic capacity (IC), older adults, ICOPE, integrated care

Citation

Yun X, Wang J, Guo AX, Gu ZJ, Sun Q, Xia JM, Jiang Q, Zhang Y and Dong Y (2025) The association of polypharmacy with intrinsic capacity: an analysis of the WHO ICOPE pilot data from Lianyungang, China. Front. Med. 12:1673885. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1673885

Received

26 July 2025

Revised

24 October 2025

Accepted

21 November 2025

Published

05 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Marios Kyriazis, National Gerontology Centre, Cyprus

Reviewed by

Nicolas Martínez-Velilla, Navarrabiomed, Spain

Ninie Yan Wang, Johns Hopkins University, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Yun, Wang, Guo, Gu, Sun, Xia, Jiang, Zhang and Dong.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yan Dong, dylzu_lnyx@163.com; Qian Sun, 710552013@qq.com; Jia Ming Xia, 1304870813@qq.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.