Abstract

Objective:

Early diagnosis of Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) is critical for improving patient outcomes. This study aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the research landscape and to identify key metabolic biomarkers and pathways associated with AKI through bibliometric analysis and meta-analysis.

Methods:

We conducted a bibliometric analysis of scientific articles on metabolomics in AKI published between 2005 and 2025. Building on this bibliometric foundation, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to delve deeper into the synthesis of findings on diagnostic metabolites.

Results:

(1) Bibliometric analysis shows rapid growth and international collaboration in AKI metabolomics research. Studies focused on risk factors, management, and underlying mechanisms. (2) Meta-analysis reveals that decreased glycine, lysine, and cystine, along with increased tryptophan, distinguish AKI patients from healthy controls. These metabolites are sensitive diagnostic biomarkers. (3) Enriched pathways identified by Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) suggest that amino acid metabolism are key contributors to AKI pathogenesis.

Discussion:

This systematic review highlights the significant diagnostic and mechanistic value of metabolomics in AKI. The identified metabolite panel and associated pathways offer promising targets for early diagnosis and elucidate critical aspects of the disease’s underlying biology.

1 Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common, complex disease with significant clinical variation (1). Studies in Canada and elsewhere show AKI incidence has risen to 1.14–1.62%. Yearly mortality rates range from 27.8 to 32.8% (2). This increase is linked to AKI’s rapid onset. Without early diagnosis and proper treatment, renal function can worsen and lead to multi-organ failure and death (3, 4).

AKI develops through complex, multifactorial mechanisms (5–7). Early and accurate diagnosis, plus timely intervention, is vital to halt or reverse disease progression (6). Traditional diagnostic markers, such as serum creatinine and urine output, often lack real-time sensitivity and may delay assessment (8). New approaches, particularly metabolomics, provide opportunities to elucidate AKI mechanisms and identify reliable early biomarkers (9, 10).

To address this diagnostic challenge, our study maps AKI research activity using bibliometric methods (11). We then systematically review and meta-analyze published studies on metabolomics in AKI (12). This structured process helps identify and validate relevant biomarkers and their associated metabolic pathways.

2 Materials and methods

The primary data for this study were derived from previously published research, all of which had already obtained ethical approval from their respective ethics committees. Therefore, the current study is considered exempt from additional ethical review.

2.1 Bibliometric analysis

2.1.1 Database selection and search strategy

With the assistance of an information specialist, we searched the Web of Science (2005–2025) for studies on AKI and metabolomics, utilizing comprehensive search terms. No language or other restrictions were applied. References of selected articles were checked, and experts were consulted for additional studies. After excluding unrelated articles, we extracted data (title, country, institution, first author, publication year, corresponding author, journal, citation count, publication type), assigning affiliation/country by the corresponding author’s institution.

2.1.2 Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were refined for data-driven studies and relevance. Studies were included if they met these three conditions: (1) Article Type: “ar” (articles); (2) Publication stage: “final”; (3) Language: English.

2.1.3 Data extraction and quality assessment

We extracted the following information from each study using a standardized data extraction form:

-

(1) General information: first author, corresponding author, the affiliated country and organization, year of publication, and journal.

-

(2) Study design, subject Information, and keywords.

To ensure consistency, two team members independently piloted data extraction on 50 random documents. Results were discussed to align the criteria. During extraction, two researchers independently collected data, discussing discrepancies, and a third researcher resolved any unresolved differences.

2.1.4 Data analysis

We used CiteSpace (v5.7. R5W) for bibliometric analysis (13, 14), including visualization and network analysis of author, institution, and keyword relationships. Bibliometric indicators (e.g., publication/citation counts, co-authorship stats) and graphical representations (bar charts, network maps) were generated to provide insights into publication trends, collaboration, and research directions in AKI (13, 15, 16).

2.2 Meta-analysis and systematic review

2.2.1 Database selection and search strategy

This review was conducted by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (17). We conducted a comprehensive search of PubMed, Ovid, Cochrane, and Web of Science databases to identify relevant studies published online. We also searched two additional preprint repositories (ESAY and medRxiv). The search strategy utilized the subject termsearch terms “metabolomics,” “lipidomics,” “acute kidney injury,” and their variants.

2.2.2 Study selection and eligibility criteria

We used EndNote X9 (Stanford University, United States) to remove duplicate records. Two researchers independently screened article titles, abstracts, and full texts. A third researcher resolved disagreements regarding selection or inclusion. Studies were included if they met all of the following:

-

(1) Human studies on AKI using case–control, cross-sectional, or cohort designs;

-

(2) Comparisons between AKI and non-AKI samples;

-

(3) Use of high-throughput metabolomics technologies (such as gas chromatography, liquid chromatography (LC), mass spectrometry (MS), or combinations) for metabolite identification in biological fluids or tissue samples;

-

(4) Analysis of human biospecimens collected prior to surgery.

Studies were excluded if they:

-

(1) Involved animal models or pregnant women;

-

(2) were non-original research (reviews, commentaries, editorials, or letters) or duplicate publications;

-

(3) did not use metabolomics methods to assess metabolite changes;

-

(4) focused on intracellular metabolite profiling;

-

(5) were from grey literature lacking sufficient information.

2.2.3 Data extraction and quality assessment

We extracted the following information from each study using a standardized data extraction form:

-

(1) General information: first author, year of publication, journal;

-

(2) Demographic information: participant location, age, sample size, biospecimen type, control type;

-

(3) Methodological information: detection methods used;

-

(4) Outcome measures: analytical data including means and standard deviations (SD), or odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for association trends;

-

(5) Study design.

Two researchers independently extracted data; disagreements were resolved with a third researcher. Study quality was assessed using the 9-point Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) (18), which reviews population selection, comparability, and exposure or outcome. Studies scoring ≥6 were considered moderate to high quality.

2.2.4 Data synthesis and meta-analysis

Following data extraction and assessment, we synthesized the results and performed meta-analysis as described below.

We used R software (version 4.2.1) to perform meta-analyses on biomarkers and metabolic pathways with available metabolite data. Studies with insufficient data or low-quality scores were excluded from the meta-analysis. The original literature in this study employed various metabolite detection techniques, primarily liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS). To integrate data from different platforms and conduct pathway analysis, we focused on the directional changes—upregulation or downregulation—of metabolites in the disease group compared to controls, rather than on absolute concentration values. We identified principal metabolic pathways associated with reported metabolites using the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (19). We used the standardized mean difference (SMD) to estimate the effect size. For studies reporting means, SD, and sample sizes, SMD were calculated using Cohen’s d method. For studies reporting only OR and 95% CI, the Hasselblad and Hedges method was used to convert these into SMD and their standard errors (SE) before inclusion.

In studies with multiple control groups, we selected the control group most age-matched to the AKI group. When multiple analytical methods were employed, we prioritized results obtained using commercial kits over those obtained through internal analytical methods. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using Cochran’s Q test and I2 statistics. Significant heterogeneity was defined as I2 > 50% and p-value ≤ 0.10 (20, 21). For results with significant heterogeneity (I2 > 50%), we performed pooled analyses using the random-effects model. Furthermore, we also specified subgroup analyses to explore potential sources of heterogeneity based on the following factors: patient age (<60 years vs. ≥60 years). Differences between subgroups were formally tested using Cochran’s Q statistic for subgroup differences, with a p-value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 General trends in metabolomics of AKI research

A total of 227 studies have been published in the field of metabolomics in AKI. Figure 1 presents the publication trend and total citation frequency. Research in this area began in 2005, with a slow increase in publications from 2005 to 2010, followed by a gradual rise after 2011. The number of studies increased sharply to 15 in 2020, peaked at 34 in 2021, declined to 31 in 2022, remained stable in 2023, and rose again to 42 in 2024 before decreasing to 9 in 2025. The rapid development and adoption of multi-omics technologies, including metabolomics, contributed to this accelerated growth. The increasing proportion of highly cited papers indicates ongoing improvements in research quality.

Figure 1

The annual distribution of publications and total citations.

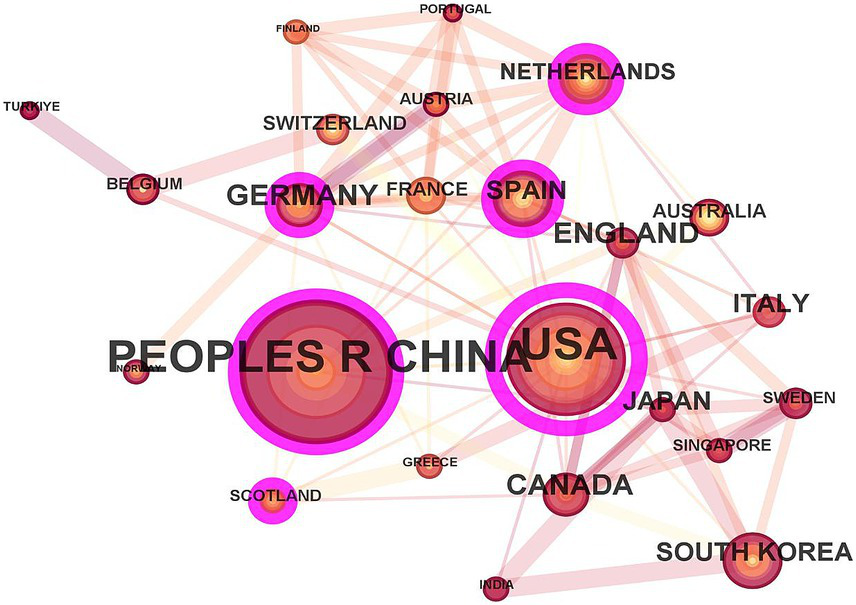

From the perspective of international collaboration networks (Figure 2), the United States acts as a central hub, frequently collaborating across regions with China and Italy. European countries, such as Germany, France, Spain, and the Netherlands, form a close-knit group. Although China has a relatively large number of publications, its cross-border cooperation is relatively less. This reflects the coexistence of globalization and regionalization in the field of metabolomics research related to AKI.

Figure 2

The scientific cooperation network among countries.

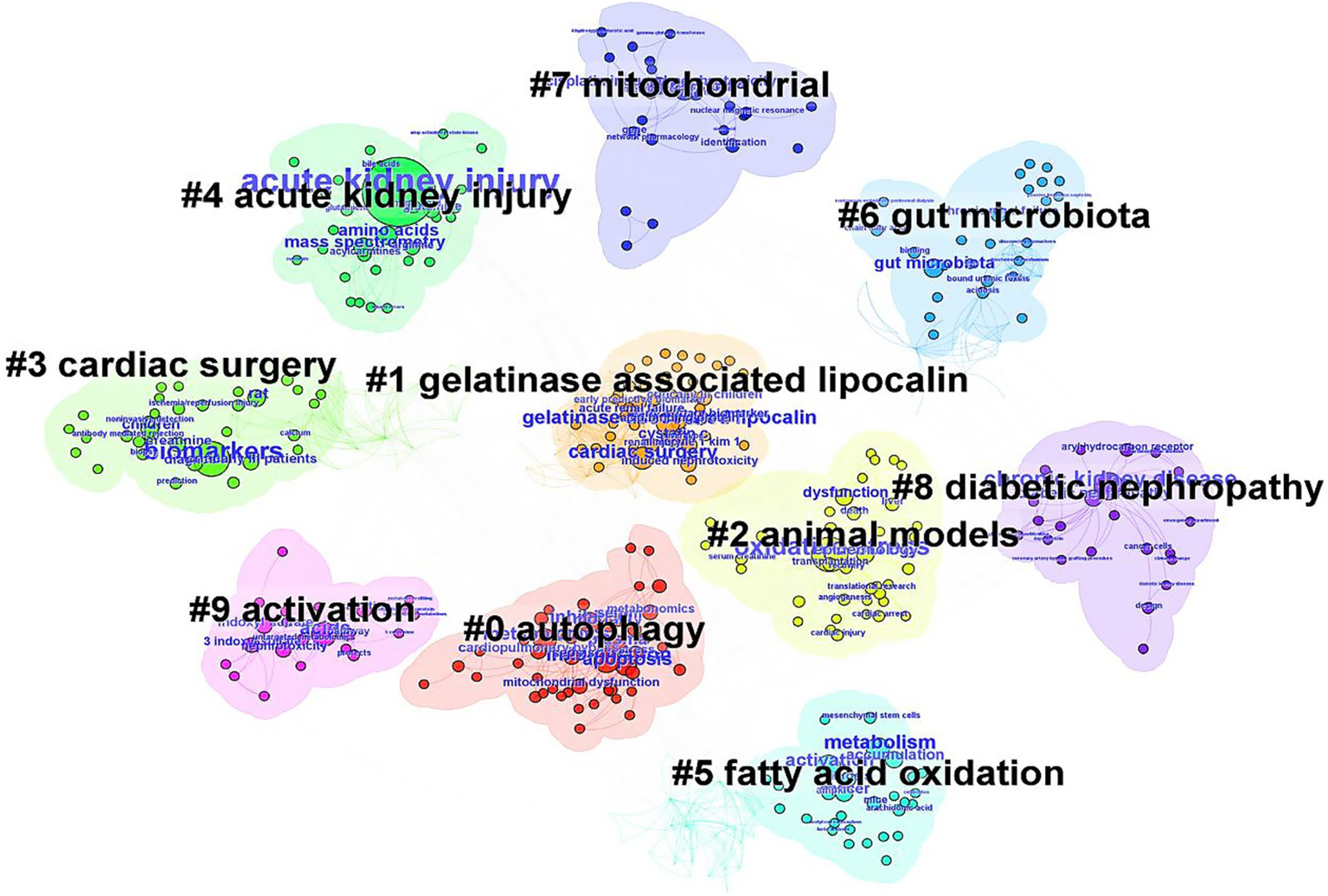

The co-citation situation of the literature was analyzed (Figure 3). The study with the highest number of citations was “De novo NAD+ biosynthetic impairment in acute kidney injury in humans” published by Mehr et al. in Nature Medicine in 2018, which was cited 19 times. Among the top 10 most co-cited articles, only 1 was published in 2014, while the remaining 9 were published between 2017 and 2020. The first authors of the 1-Keyword clusters represent the core themes of the research. A keyword co-occurrence analysis identified 343 terms, with 35 appearing at least five times and 14 appearing ten times or more. Notably, oxidative stress and inflammation emerged as prominent keywords. Visualization of keyword co-occurrence (Figure 4) highlights frequently co-occurring terms, revealing research hotspots in AKI metabolomics. Autophagy and gelatinase-associated lipocalin are also significant co-occurring keywords. These findings indicate an increasing research focus on the intrinsic mechanisms of AKI and its potential clinical applications.

Figure 3

The citation co-occurrence network. The color bar from bottom (blue) to top (red) indicates the year from 2005 to 2025.

Figure 4

The keyword clusters network in metabolomics of AKI from 2005 to 2025.

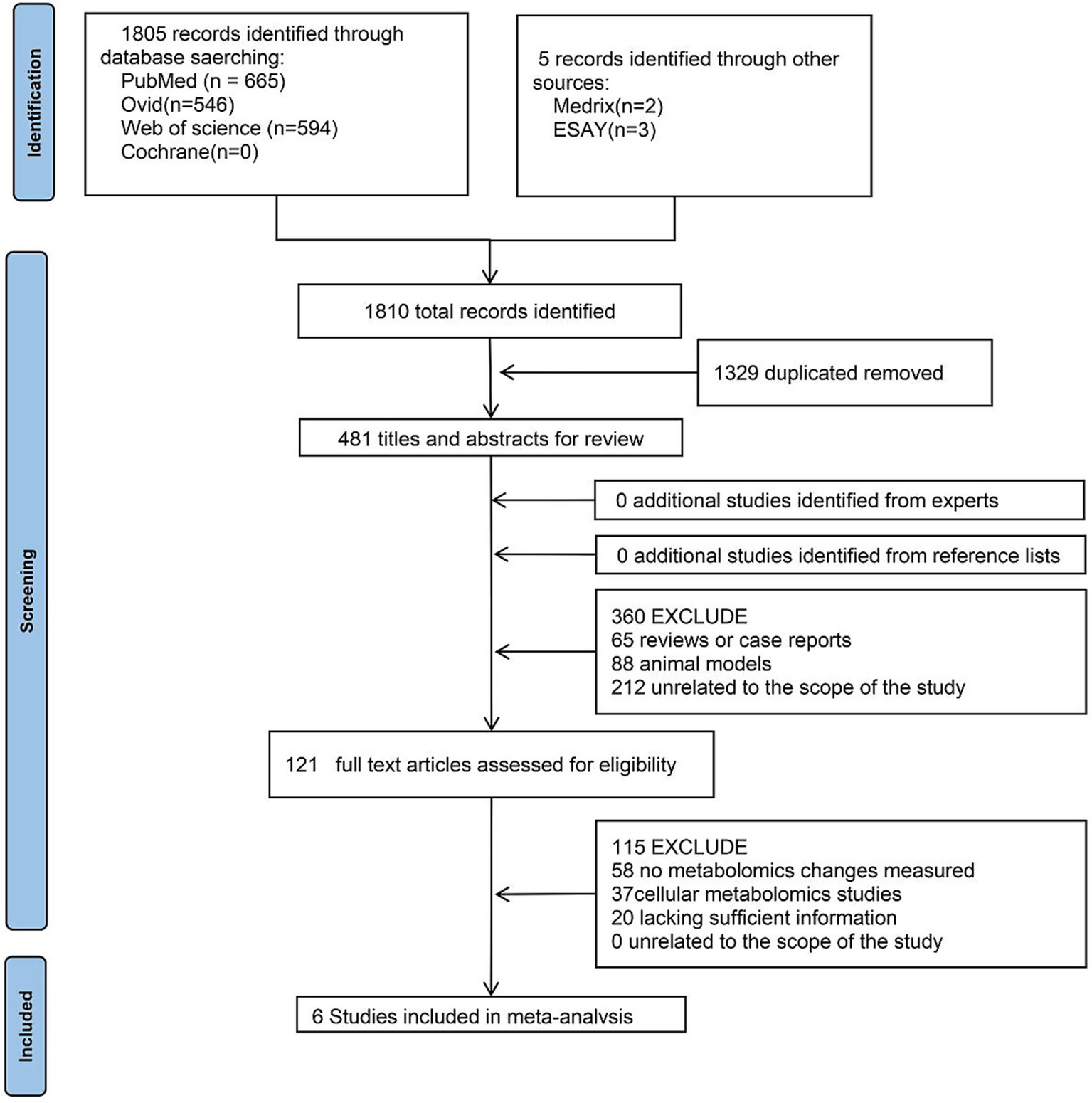

3.2 Literature search results for the meta-analysis

Figure 5 shows the literature search and study selection process. An initial database search yielded 1,810 articles. After removing duplicates, 481 articles remained, and their titles and abstracts were independently screened by two reviewers, leading to the exclusion of 360 articles. Manual reference list screening and expert consultation did not identify any additional relevant studies. The full texts of the remaining 121 articles were reviewed, of which 115 were excluded. Ultimately, six studies with extractable data were included in the systematic review.

Figure 5

Flowchart of meta-analysis.

3.3 Characteristics and quality assessment of included studies

Six studies were included and summarized in Table 1 based on extractable data. These studies were published between 2016 and 2024, with sample sizes ranging from 44 to 159 participants (median: 80). All six employed untargeted metabolomics analyses. The geographic distribution included two European studies, three from Asia, and one from North America. Four studies analyzed blood samples, while two analyzed urine samples. These six studies, in terms of both their publication time and sources, align with the annual and regional trends identified through our bibliometric analysis. This provides indirect confirmation of the research trends in bibliometrics and also indicates that the meta-analysis data are representative.

Table 1

| First author | Publication date | Journal (JCR classification) | Participant location | Age | Sample size (number of AKI) | Biological sample type | Control type | Detection method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sammy Elmariah, MD (67) | 2016 | Journal of the American Heart Association (Q1) | Massachusetts General Hospital (United States) | 81.90 ± 8.50 | 44 (9) | Plasma | Case–control | LC–MS |

| Feng Zhang (71) | 2018 | Science Reports (Q2) | Shanghai Changzheng Hospital (CHN) | 32.71 ± 7.80 | 66 (30) | Plasma | Case–control | LC–MS/MS |

| Hyun-Seung Lee (72) | 2021 | Antioxidants (Q1) | Samsung Medical Center, School of Medicine, Singkyunwan University, South Korea (KOR) | 60.20 ± 13.10 | 97 (28) | Serum | Case–control | LC–MS/MS |

| Meice Tian (73) | 2021 | Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (Q1) | Fuwai Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CHN) | 64 (59–67) | 159 (55) | Urine | Cohort studies | LC–MS |

| Sevilay Erdogan Kablan (68) | 2024 | Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry (Q4) | Ankara City Hospital, Turkey (TR) | – | 107 (9) | Plasma | Case–control | LC–MS |

| Claudia Muhle-Goll (74) | 2020 | International Journal of Molecular Science (Q1) | Heidelberg Children’s Hospital, Germany (GER) | 3.90 (0 ~ 18) | 65 (53) | Urine | Case–control | LC–MS |

Six studies included in the meta-analysis.

“–” Age was not reported in the article; Age (age range); age ± standard deviation.

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess study quality, with scores ranging from 6 to 6.5. The mean score was 6.38 ± 1.1 (mean ± SD), and all six studies were considered to be of moderate to high quality (score ≥ 6).

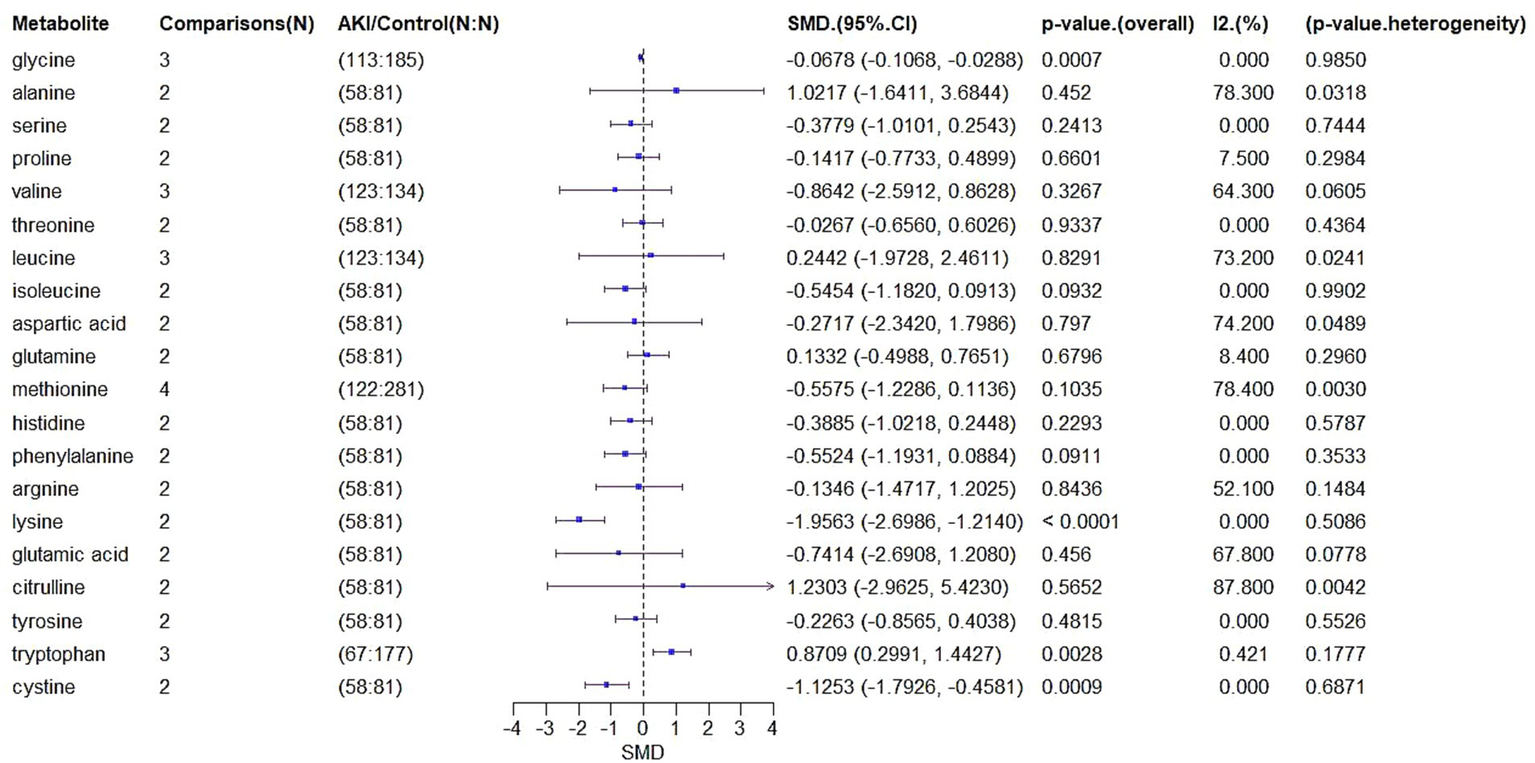

3.4 Meta-analysis of biomarker expression in AKI

We extracted SMD and SE for 61 metabolites from the six studies (Figure 6). A total of 135 biomarkers were reported, and a meta-analysis was conducted on 20 metabolites that appeared across multiple studies (Table 2).

Figure 6

Forest plot of SMD in metabolite levels.

Table 2

| Metabolite | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-adenosylhomocysteine | Leucine | Histidine | Beta-alanine | N.Anserine |

| Glycine | Isoleucine | Phenylalanine | Aminoadipic acid | Alpha-aminobutyric acid |

| Serine | Aspartic acid | Argnine | Gamma-aminobutyric acid | Beta-aminoisobutyric acid |

| Proline | Glutamine | Citrulline | Asparagine | Carnosine |

| Valine | Lysine | Hippuric | Cystathionine | Ethanolamine |

| Threonine | Glutamic acid | Tyrosine | Homocysteine | Dehydroxylysine |

| Oxoproline | Methionine | Symmetric dimethyl arginine | Hydroxyproline | Methylhistidine |

| Citrulline | Cystathionine | Cystine | 3-methylhistidine | Ornithine |

| O-phosphoethanolamine | O-phosphoserine | Sarcosine | Taurine | Tyrosine |

| Argininosuccinic acid | Homocitrulline | All-isoleucine | Serotonin | 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid |

| Deoxycholic acid glycine conjugate | 5-Acetylamino-6-amino-3-methyluracil | L-Methionine | Tyrosyl-gamma-glutamate | Arginylarginine |

| 2-Piperidone | 3-Indolelactic acid | Leucrose | Methyl palmitate | Sophorose |

| Uracil | ||||

Differential metabolites related to AKI in six studies.

For glycine, which was analyzed in three comparisons involving 113 AKI patients and 185 controls, the SMD was −0.0678 (95% CI: −0.1068 to −0.0288, p = 0.0007), indicating significantly lower levels in AKI patients. Heterogeneity was negligible (I2 = 0%, p = 0.985).

Alanine, based on two comparisons involving 58 AKI patients and 81 controls, showed an SMD of 1.0217 (95% CI: −1.6411 to 3.6844, p = 0.452), indicating no significant difference but substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 78.3%, p = 0.0318).

Other metabolites including serine (SMD = −0.3779, p = 0.2413), proline (SMD = −0.1417, p = 0.6601), valine (SMD = −0.8642, p = 0.3267), threonine (SMD = −0.0267, p = 0.9337), leucine (SMD = 0.2442, p = 0.8291), isoleucine (SMD = −0.5454, p = 0.0932), aspartic acid (SMD = −0.2717, p = 0.797), and glutamine (SMD = 0.1332, p = 0.6796) also showed no significant differences. However, several exhibited moderate to high heterogeneity.

Notably, lysine (SMD = −1.9563, 95% CI: −2.6986 to −1.214, p < 0.0001) and cystine (SMD = −1.1253, 95% CI: −1.7926 to −0.4581, p = 0.0009) showed significantly reduced levels in AKI patients, with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). Tryptophan levels increased significantly (SMD = 0.8709, 95% CI: 0.2991 to 1.4427, p = 0.0028, I2 = 42.1%).

These findings suggest that glycine, lysine, cysteine, and tryptophan may be candidate biomarkers for AKI, while other metabolites either showed inconsistent trends or lacked statistical significance.

3.5 Meta-analysis of metabolic pathway expression in AKI

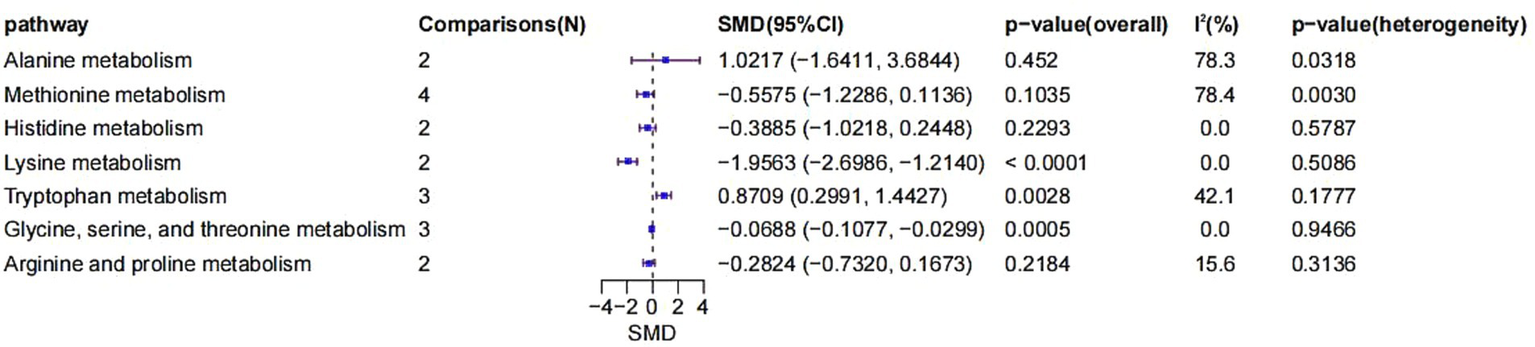

The included studies also enabled the comparison of metabolite expression across various metabolic pathways (Figure 7). First, two comparisons were included in the alanine metabolism pathway. The SMD was 1.0217 (95% CI: −1.6411 to 3.6844, p = 0.4520), indicating no significant difference. However, heterogeneity was high (I2 = 78.3%, p = 0.0318), suggesting considerable inconsistency across studies.

Figure 7

Forest plot of SMD in metabolomic pathways.

Four comparisons were analyzed for methionine metabolism, with an SMD of −0.5575 (95% CI: −1.2286 to 0.1136, p = 0.1035). Although not statistically significant, a noticeable negative trend was observed. Heterogeneity was significant (I2 = 78.4%, p = 0.0030).

Histidine metabolism involved two comparisons, yielding an SMD of −0.3885 (95% CI: −1.0218 to 0.2448, p = 0.2293), indicating no significant change. Heterogeneity was absent (I2 = 0%, p = 0.5787).

Lysine metabolism, based on two comparisons, showed a significantly negative SMD of −1.9563 (95% CI: −2.6986 to −1.2140, p < 0.0001), with no observed heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, p = 0.5086).

For tryptophan metabolism, three comparisons yielded a significantly positive SMD of 0.8709 (95% CI: 0.2991 to 1.4427, p = 0.0028), with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 42.1%, p = 0.1777).

Glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism, based on three comparisons, presented a significantly negative SMD of −0.0688 (95% CI: −0.1077 to −0.0299, p = 0.0005), with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, p = 0.9466).

Lastly, for arginine and proline metabolism, two comparisons yielded an SMD of −0.2824 (95% CI: −0.7320 to 0.1673, p = 0.2184), which was not statistically significant. Heterogeneity was low (I2 = 15.6%, p = 0.3136).

In summary, significant negative changes were found in lysine and glycine-serine–threonine metabolism, while tryptophan metabolism demonstrated a significant positive alteration. These results suggest that specific metabolic pathways may play crucial roles in the development and progression of AKI, particularly through their involvement in oxidative stress, inflammation, and dysfunction of energy metabolism.

3.6 The subgroup analysis based on age revealed the possible sources of heterogeneity

We compared the effect sizes between the <60-year-old and ≥60-year-old groups using the method suggested by Cochrane. A statistically significant effect modification by age was observed for three metabolites: alanine (Q = 4.61, df = 1, p = 0.0318), aspartic acid (Q = 3.88, df = 1, p = 0.0489), and citrulline (Q = 8.18, df = 1, p = 0.0042), suggesting a more pronounced intervention-associated alteration in these metabolites among patients aged ≥60 years. No significant subgroup differences were detected for proline, leucine, arginine, or glutamine (all p > 0.05). Methionine was excluded from this analysis as data were available from only one study that did not report the mean age.

At the pathway level, we applied the same age-stratified subgroup analysis to several key metabolic pathways. A significant subgroup difference was identified for the alanine metabolism pathway (Q = 4.61, df = 1, p = 0.0318), providing further evidence that its response to the intervention varies by age. In contrast, a subgroup analysis for the methionine metabolism pathway was not feasible due to a lack of age-stratified data in the relevant studies.

4 Discussion

4.1 The research on the metabolomics of AKI has developed rapidly

Bibliometric analysis indicates that metabolomics studies related to AKI are gaining increasing attention, with a year-by-year rise in publication volume. However, regional disparities persist—most notably, the United States and China exhibit the most significant growth, reflecting associations with demographic changes (22) and economic development (23). Although collaborations exist among researchers and institutions, international cooperation has substantial gaps. The United States maintains strong ties with other developed countries while developing nations lag in research output and collaborative engagement. The current research focuses on (1) risk factors and management strategies, (2) clinical causes and interventions, and (3) pathophysiological mechanisms of AKI. In the early stages of disease occurrence, the body’s metabolic level can undergo sensitive changes (24). Metabolomics provides novel insights into risk factors, pathophysiological mechanisms, and therapeutic approaches (10). Biomarkers identified through metabolomics can facilitate early detection and intervention, which is helpful for precision and personalized medicine (25, 26). While some investigators have explored AKI using metabolomics, our bibliometric findings suggest that these efforts remain relatively limited. Identifying sensitive biomarkers related to AKI is not only beneficial for formulating tertiary prevention policies for community and clinical management, but also enables the development of medication regimens by revealing the pathogenesis. Therefore, based on the analysis of bibliometric data, we further explored the current limited research and employed a meta-analysis method to investigate the changes in biomarkers and metabolic pathways in depth.

4.2 Differences in amino acid metabolism can be used for the early diagnosis of patients with AKI

Given the kidney’s central role in amino acid metabolism, AKI can disrupt this balance (27). An important component for the body to maintain amino acid metabolic homeostasis is the nephron filtration/reabsorption mechanism occurring in the renal cortex, as well as the amino acid metabolism of renal cells (28–30). The common pathophysiological processes of AKI include endothelial dysfunction and renal tubular cell injury (31). AKI can not only affect the amino acid reabsorption process of renal tubules (32), but also damage renal cells, causing disorders in amino acid metabolism (33, 34). Therefore, Abnormal amino acid metabolism may occur in the early stage of AKI disease and be accompanied by the progression of the disease.

Our research results verify and emphasize the importance of amino acid metabolism differences in the early diagnosis of AKI. Glycine, lysine, and cystine levels were significantly decreased in AKI patients, while tryptophan levels increased, highlighting their potential as early diagnostic markers. Conversely, isoleucine approached statistical significance but may have limited diagnostic value. Currently, in clinical practice, the diagnosis and monitoring of the condition are primarily based on changes in serum creatinine levels and urine output, employing a single approach that is limited to the overall manifestations of the disease. The aforementioned metabolites show more sensitive changes and provide a more direct and intuitive reflection of the degree and source of kidney damage. Therefore, in future studies, the identified metabolites should be combined with traditional markers, such as serum creatinine and/or Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), to improve the sensitivity and time curves of different indicators and construct a superior integrated diagnostic model.

4.3 The amino acid metabolism differences in AKI patients are caused by filtration/reabsorption disorders and metabolic disorders

After amino acids are freely filtered by the glomerulus, glycine is mainly transported and reabsorbed through XT2 (SLC618) (27), while lysine (35) and cystine (36) are reabsorbed from the ultrafiltrate through rBAT/b0,+AT (SLC3A1/SLC7A9). The significant decrease in the levels of these three amino acids may be related to the reabsorption disorder caused by AKI. More importantly, the metabolic disorders are caused by the cell damage triggered by AKI. Serine can be converted into glycine by serine hydroxymethyltransferase in the kidneys using tetrahydrofolate as a cofactor (37). AKI can lead to a decrease in serine hydroxymethyltransferase levels, thereby blocking the production process of glycine (38). Meanwhile, metabolic acidosis induced by AKI led to an increase in the renal activity of the glycine cleavage enzyme complex, which further caused the decomposition of glycine (39, 40). Lysine is an essential amino acid that humans cannot produce. Its catabolism has two main directions, namely the saccharopine pathway and the pipecolate pathway, which primarily occur in the liver and brain, respectively (35). However, the kidneys can convert lysine into carnitine and lysine conjugates through enzymes. AKI can lead to an increase in the activity of lysine methyltransferase, causing lysine methylation to produce lysine conjugates and thereby reducing lysine levels (36). The cystine/glutamate antiporter in renal tubular cells can take up cystine and regulate intracellular glutathione synthesis to maintain cellular redox balance (41). AKI can cause an imbalance in this process and may be another reason for the decrease in cystine (42). Decreased renal function can lead to a decrease in the excretion of tryptophan and its metabolites, resulting in their accumulation in the body (27, 43). Tryptophan is an essential amino acid for humans, with 95% of it being metabolized through the kynurenine pathway. The key enzymes are indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) (44). Under normal physiological conditions, tryptophan is mainly metabolized by TDO. However, during the inflammation or stress period concurrent with AKI, the activity of TDO is inhibited, tryptophan metabolism is abnormal, and its level increases, and IDO is rapidly activated. The pathway of tryptophan metabolism shifts from being dominated by liver TDO to being dominated by extrahepatic IDO (45). Our research results emphasize the diagnostic value of amino acid metabolism alterations in AKI, which may be caused by complex disorders affecting filtration/reabsorption, as well as metabolic disorders. Further studies are needed to clarify their relationship.

4.4 Amino acid metabolism disorder reveals the pathogenesis of AKI

Pathway-level analysis revealed the pathogenesis of AKI. AKI caused by ischemia–reperfusion injury can induce a significant increase in lysine-specific demethylase 1 expression through the AKT pathway, thereby affecting the lysine metabolic pathway and generating oxidative stress and ferroptosis via the TLR4/NOX4 pathway (46). Another epigenetic regulatory mechanism involving lysine suggests that histone lysine crotonylation exists during AKI (47). Histone lysine crotonylation may be related to the increase in inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK), indicating that inflammation is also an important pathogenesis of AKI (48). Lysine supplementation, in contrast, may exert renal protective effects through diuresis, conjugate formation, and reduced albumin uptake (49).

Suppressed glycine-serine–threonine metabolism implies involvement in oxidative stress (50) and inflammation (51). Glycine can trigger the opening of the GlyR ion channel, resulting in rapid hyperpolarization, a decrease in calcium, and a reduction in the synthesis of pro-inflammatory mediators, likely via the tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) receptor signaling pathway (52). Glycine production and reabsorption decrease during the AKI process. Low levels of glycine can reduce the protective effect of cells as mentioned above, exacerbate inflammation, and aggravate kidney damage. The decrease in glycine levels may also have a significant impact on long-term renal function through this change in microcirculation structure (53).

The tryptophan metabolic pathway includes kynurenine and indoxyl sulfate. AKI can lead to disorders in the kynurenine pathway and indolethiol sulfate activity (54). Kynurenine and indoxyl sulfate downregulated β-catenin through the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) (55). This will lead to a decrease in microvessel density, affecting the blood flow function of the kidneys. Kynurenine can also induce immune tolerance by interfering with the development and expansion of regulatory T cells and T helper 2 through AHR (56). Furthermore, IDO, involved in the kynourine pathway, is highly expressed in antigen-presenting cells. AKI leads to the inhibition of TDO activity, and IDO is activated, which limits the proliferation and normal function of T cells (45, 56).

The decrease or increase in the metabolic pathways of these several amino acids and the occurrence and development of AKI have a sensitive and reciprocal relationship. It particularly reveals that oxidative stress, inflammation, and immune dysfunction all play a significant role in this process. This aligns with the current research hotspots, as summarized by our bibliometric analysis. This fully demonstrates that regulating these processes may have therapeutic potential.

4.5 The application potential and future development direction of metabolomics in the field of biomarkers for the early diagnosis of AKI

Our research summarized several sensitive amino acids that can be used for the early diagnosis of AKI. There are also some amino acids that have high heterogeneity. The high heterogeneity indicates significant differences among the studies. We attempted to explore the sources of heterogeneity through subgroup analysis and found that age might be an important factor contributing to the high heterogeneity. Some metabolites with high heterogeneity, such as alanine, showed statistically significant differences based on age. Age, gender, race, and other demographic characteristics are all directly related to kidney function status (57). We suggest that future studies should fully consider the differences in population characteristics when diagnosing and treating AKI, and establish metabolomics analyses for samples from diverse populations. Furthermore, variations in detection techniques across the original studies—such as differences in sample preparation (58), chromatography columns (59), instrument conditions (60, 61), and data processing strategies (62, 63)—have led to differences in the coverage of metabolite groups, introducing heterogeneity that may compromise the comprehensiveness and accuracy of pathway analysis. Consequently, the findings of this study primarily highlight recurrent and relatively stable metabolic pathway perturbations observed across different studies, rather than capturing the full spectrum of alterations within the metabolic network. More unified and standardized research is needed in the future to confirm the diagnostic value of these findings. Linking amino acid levels directly to immune dysfunction or ferroptosis is speculative and not directly supported by the meta-analyzed studies. However, our bibliometric data also reveal key research hotspots, providing a direction for future experimental research.

This meta-analysis only included six studies, and the available data were limited. Our analysis was limited by the inability to stratify studies by sample type, AKI etiology, or disease stage (64, 65). AKI subtypes (such as prerenal, intrinsic, and postrenal), etiologies (drugs, infections, ischemia, etc.), and progression stages are closely related (66). To enhance the adaptability and interpretability of future findings, it will be crucial to utilize larger, more diverse cohorts and conduct detailed, stratified analyses. Furthermore, a deeper investigation into the specificity and underlying mechanisms of metabolic alterations in specific pathologies is warranted.

Overall, this study advances our understanding of metabolomics in AKI and identifies key challenges. Metabolomics can comprehensively capture the functional metabolic responses of the body in a diseased state, sensitively identifying characteristic metabolic disturbances that occur before clinical observation indicators, such as decreased glomerular filtration rate and elevated serum creatinine (67, 68). Therefore, it is recommended that future research establish baseline metabolic profiles for patients with high-risk factors for AKI (such as diabetes, heart failure, old age.) and healthy controls; establish metabolic database for different etiologies of AKI (such as ischemia–reperfusion, sepsis, contrast agent.); perform dynamic metabolomics analysis at different time points of acute kidney injury (early stage, peak stage, recovery stage/transitional stage to chronic kidney disease stage), and conduct statistical correlation and integration with existing clinical observation indicators; and integrate transcriptomic and proteomic data for comprehensive biomarker mining and pathway enrichment analysis (69); and conduct a series of metabolomics monitoring before and after implementing intervention measures (such as drug treatment, nutritional support) on patients. With continued AI development, predictive models based on metabolomics and clinical features may further enhance diagnosis and treatment (70). Thus, systematic, full-course, and precise disease early diagnosis, management, and intervention can be achieved.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

ZK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KY: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. JL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. YL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Natural Science Research Project of Basic Research Programme in Shanxi Province under Grant number 202203021221268 and Young Scientists Fund of National Natural Science foundation of China under Grant number 82305030.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Ostermann M Lumlertgul N Jeong R See E Joannidis M James M . Acute kidney injury. Lancet. (2025) 405:241–56. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)02385-7

2.

Sawhney S Bell S Black C Christiansen CF Heide-Jørgensen U Jensen SK et al . Harmonization of epidemiology of acute kidney injury and acute kidney disease produces comparable findings across four geographic populations. Kidney Int. (2022) 101:1271–81. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2022.02.033

3.

Kellum JA Romagnani P Ashuntantang G Ronco C Zarbock A Anders HJ . Acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2021) 7:52. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00284-z

4.

Zhu Z Hu J Chen Z Feng J Yang X Liang W et al . Transition of acute kidney injury to chronic kidney disease: role of metabolic reprogramming. Metabolism. (2022) 131:155194. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2022.155194

5.

Bai Y Chi K Zhao D Shen W Liu R Hao J et al . Identification of functional heterogeneity of immune cells and tubular-immune cellular interplay action in diabetic kidney disease. J Transl Int Med. (2024) 12:395–405. doi: 10.2478/jtim-2023-0130

6.

Molitoris BA . Low-flow acute kidney injury: the pathophysiology of prerenal Azotemia, abdominal compartment syndrome, and obstructive uropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. (2022) 17:1039–49. doi: 10.2215/CJN.15341121

7.

Li ZL Li XY Zhou Y Wang B Lv LL Liu BC . Renal tubular epithelial cells response to injury in acute kidney injury. EBioMedicine. (2024) 107:105294. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2024.105294

8.

Kellum JA Ronco C Bellomo R . Conceptual advances and evolving terminology in acute kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2021) 17:493–502. doi: 10.1038/s41581-021-00410-w

9.

Pereira PR Carrageta DF Oliveira PF Rodrigues A Alves MG Monteiro MP . Metabolomics as a tool for the early diagnosis and prognosis of diabetic kidney disease. Med Res Rev. (2022) 42:1518–44. doi: 10.1002/med.21883

10.

Qiu S Cai Y Yao H Lin C Xie Y Tang S et al . Small molecule metabolites: discovery of biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2023) 8:132. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01399-3

11.

Agarwal A Durairajanayagam D Tatagari S Esteves SC Harlev A Henkel R et al . Bibliometrics: tracking research impact by selecting the appropriate metrics. Asian J Androl. (2016) 18:296–309. doi: 10.4103/1008-682X.171582

12.

Hernandez AV Marti KM Roman YM . Meta-analysis. Chest. (2020) 158:S97–S102. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.003

13.

Jiang S Liu Y Zheng H Zhang L Zhao H Sang X et al . Evolutionary patterns and research frontiers in neoadjuvant immunotherapy: a bibliometric analysis. Int J Surg. (2023) 109:2774–83. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000492

14.

Zhang P Zhang J Wang M Feng S Yuan Y Ding L . Research hotspots and trends of neuroimaging in social anxiety: a citespace bibliometric analysis based on web of science and Scopus database. Front Behav Neurosci. (2024) 18:1448412. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2024.1448412

15.

Afuye GA Kalumba AM Busayo ET Orimoloye IR . A bibliometric review of vegetation response to climate change. Environ Sci Pollut Res. (2021) 29:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-16319-7

16.

Alkhammash R . Bibliometric, network, and thematic mapping analyses of metaphor and discourse in COVID-19 publications from 2020 to 2022. Front Psychol. (2023) 13:1062943. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1062943

17.

Sarkis-Onofre R Catalá-López F Aromataris E Lockwood C . How to properly use the PRISMA statement. Syst Rev. (2021) 10:117. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01671-z

18.

Stang A . Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. (2010) 25:603–5. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z

19.

Anwar AM Ahmed EA Soudy M Osama A Ezzeldin S Tanios A et al . Xconnector: retrieving and visualizing metabolites and pathways information from various database resources. J Proteome. (2021) 245:104302. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2021.104302

20.

Hedges LV Olkin I . Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Orlando: Academic Press (1985).

21.

Higgins J Thompson SG Deeks JJ Altman DG . A meta-analysis on the effectiveness of smart-learning. BMJ. (2003) 327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

22.

Francis A Harhay MN Ong ACM Tummalapalli SL Ortiz A Fogo AB et al . Chronic kidney disease and the global public health agenda: an international consensus. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2024) 20:473–85. doi: 10.1038/s41581-024-00820-6

23.

Cullis B McCulloch M Finkelstein FO . Development of PD in lower-income countries: a rational solution for the management of AKI and ESKD. Kidney Int. (2024) 105:953–9. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2023.11.036

24.

Liu C Liu T Zhang Q Song M Zhang Q Shi J et al . Temporal relationship between inflammation and metabolic disorders and their impact on cancer risk. J Glob Health. (2024) 16:04041. doi: 10.7189/jogh.14.04041

25.

Wishart DS . Metabolomics for investigating physiological and pathophysiological processes. Physiol Rev. (2019) 99:1819–75. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00035.2018

26.

Lin C Tian Q Guo S Xie D Cai Y Wang Z et al . Metabolomics for clinical biomarker discovery and therapeutic target identification. Molecules. (2024) 29:2198. doi: 10.3390/molecules29102198

27.

Knol MGE Wulfmeyer VC Müller RU Rinschen MM . Amino acid metabolism in kidney health and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2024) 20:771–88. doi: 10.1038/s41581-024-00872-8

28.

Li X Zheng S Wu G . Amino acid metabolism in the kidneys: nutritional and physiological significance. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2020) 1265:71–95. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-45328-2_5

29.

Bröer S Gauthier-Coles G . Amino acid homeostasis in mammalian cells with a focus on amino acid transport. J Nutr. (2022) 152:16–28. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxab342

30.

Makrides V Camargo SM Verrey F . Transport of amino acids in the kidney. Compr Physiol. (2014) 4:367–403. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130028

31.

Ostermann M Liu K . Pathophysiology of AKI. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. (2017) 31:305–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2017.09.001

32.

Ho KM Morgan DJR . The proximal tubule as the pathogenic and therapeutic target in acute kidney injury. Nephron. (2022) 146:494–502. doi: 10.1159/000522341

33.

Li Z Liu Z Luo M Li X Chen H Gong S et al . The pathological role of damaged organelles in renal tubular epithelial cells in the progression of acute kidney injury. Cell Death Discov. (2022) 8:239. doi: 10.1038/s41420-022-01034-0

34.

Li N Wang Y Wang X Sun N Gong YH . Pathway network of pyroptosis and its potential inhibitors in acute kidney injury. Pharmacol Res. (2022) 175:106033. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.106033

35.

Tan Y Chrysopoulou M Rinschen MM . Integrative physiology of lysine metabolites. Physiol Genomics. (2023) 55:579–86. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00061.2023

36.

Zhou X Chen H Li J Shi Y Zhuang S Liu N . The role and mechanism of lysine methyltransferase and arginine methyltransferase in kidney diseases. Front Pharmacol. (2022) 13:885527. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.885527

37.

Wang W Wu Z Dai Z Yang Y Wang J Wu G . Glycine metabolism in animals and humans: implications for nutrition and health. Amino Acids. (2013) 45:463–77. doi: 10.1007/s00726-013-1493-1

38.

Wei J Zhang J Wei J Hu M Chen X Qin X et al . Identification of AGXT2, SHMT1, and ACO2 as important biomarkers of acute kidney injury by WGCNA. PLoS One. (2023) 18:e0281439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0281439

39.

Hamid AK Pastor Arroyo EM Calvet C Hewitson TD Muscalu ML Schnitzbauer U et al . Phosphate restriction prevents metabolic acidosis and curbs rise in FGF23 and mortality in murine folic acid-induced AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2024) 35:261–80. doi: 10.1681/ASN.0000000000000291

40.

Lowry M Hall DE Brosnan JT . Increased activity of renal glycine-cleavage-enzyme complex in metabolic acidosis. Biochem J. (1985) 231:477–80. doi: 10.1042/bj2310477

41.

Shimomura T Hirakawa N Ohuchi Y Ishiyama M Shiga M Ueno Y . Simple fluorescence assay for cystine uptake via the xCT in cells using Selenocystine and a fluorescent probe. ACS Sens. (2021) 6:2125–8. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.1c00496

42.

Ma Y Fei S Chen X Gui Y Zhou B Xiang T et al . Chemerin attenuates acute kidney injury by inhibiting ferroptosis via the AMPK/NRF2/SLC7A11 axis. Commun Biol. (2024) 7:1679. doi: 10.1038/s42003-024-07377-x

43.

Hui Y Zhao J Yu Z Wang Y Qin Y Zhang Y et al . The role of tryptophan metabolism in the occurrence and progression of acute and chronic kidney diseases. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2023) 67:e2300218. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.202300218

44.

Klaessens S Stroobant V De Plaen E Van den Eynde BJ . Systemic tryptophan homeostasis. Front Mol Biosci. (2022) 9:897929. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2022.897929

45.

Zhao L Hao Y Tang S Han X Li R Zhou X . Energy metabolic reprogramming regulates programmed cell death of renal tubular epithelial cells and might serve as a new therapeutic target for acute kidney injury. Front Cell Dev Biol. (2023) 11:1276217. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2023.1276217

46.

Feng R Xiong Y Lei Y Huang Q Liu H Zhao X et al . Lysine-specific demethylase 1 aggravated oxidative stress and ferroptosis induced by renal ischemia and reperfusion injury through activation of TLR4/NOX4 pathway in mice. J Cell Mol Med. (2022) 26:4254–67. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.17444

47.

Jiang G Li C Lu M Lu K Li H . Protein lysine crotonylation: past, present, perspective. Cell Death Dis. (2021) 12:703. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-03987-z

48.

Ruiz-Andres O Sanchez-Niño MD Cannata-Ortiz P Ruiz-Ortega M Egido J Ortiz A et al . Histone lysine crotonylation during acute kidney injury in mice. Dis Model Mech. (2016) 9:633–45. doi: 10.1242/dmm.024455

49.

Rinschen MM Palygin O El-Meanawy A Domingo-Almenara X Palermo A Dissanayake LV et al . Accelerated lysine metabolism conveys kidney protection in salt-sensitive hypertension. Nat Commun. (2022) 13:4099. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31670-0

50.

Wu X Liu C Yang S Shen N Wang Y Zhu Y et al . Glycine-serine-threonine metabolic Axis delays intervertebral disc degeneration through antioxidant effects: an imaging and Metabonomics study. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. (2021) 2021:5579736. doi: 10.1155/2021/5579736

51.

He W Xi Q Cui H Zhang P Huang R Wang T et al . Liang-Ge decoction ameliorates acute lung injury in septic model rats through reducing inflammatory response, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and modulating host metabolism. Front Pharmacol. (2022) 13:926134. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.926134

52.

Aguayo-Cerón KA Sánchez-Muñoz F Gutierrez-Rojas RA Acevedo-Villavicencio LN Flores-Zarate AV Huang F et al . Glycine: the smallest anti-inflammatory micronutrient. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:11236. doi: 10.3390/ijms241411236

53.

Wildman SS Dunn K Van Beusecum JP Inscho EW Kelley S Lilley RJ et al . A novel functional role for the classic CNS neurotransmitters, GABA, glycine, and glutamate, in the kidney: potent and opposing regulators of the renal vasculature. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. (2023) 325:F38–49. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00425.2021

54.

Zakrocka I Załuska W . Kynurenine pathway in kidney diseases. Pharmacol Rep. (2022) 74:27–39. doi: 10.1007/s43440-021-00329-w

55.

Arinze NV Yin W Lotfollahzadeh S Napoleon MA Richards S Walker JA et al . Tryptophan metabolites suppress the Wnt pathway and promote adverse limb events in chronic kidney disease. J Clin Invest. (2022) 132:e142260. doi: 10.1172/JCI142260

56.

Krupa A Krupa MM Pawlak K . Kynurenine pathway-an underestimated factor modulating innate immunity in Sepsis-induced acute kidney injury?Cells. (2022) 11:2604. doi: 10.3390/cells11162604

57.

Yu S Yang H Wang B Guo X Li G Sun Y . Nomogram for predicting risk of mild renal dysfunction among general residents from rural Northeast China. J Transl Int Med. (2024) 12:244–52. doi: 10.2478/jtim-2023-0003

58.

Zheng R Brunius C Shi L Zafar H Paulson L Landberg R et al . Prediction and evaluation of the effect of pre-centrifugation sample management on the measurable untargeted LC-MS plasma metabolome. Anal Chim Acta. (2021) 1182:338968. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2021.338968

59.

Harrieder EM Kretschmer F Böcker S Witting M . Current state-of-the-art of separation methods used in LC-MS based metabolomics and lipidomics. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. (2022) 1188:123069. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2021.123069

60.

Chen CJ Lee DY Yu J Lin YN Lin TM . Recent advances in LC-MS-based metabolomics for clinical biomarker discovery. Mass Spectrom Rev. (2023) 42:2349–78. doi: 10.1002/mas.21785

61.

Roca M Alcoriza MI Garcia-Cañaveras JC Lahoz A . Reviewing the metabolome coverage provided by LC-MS: focus on sample preparation and chromatography-a tutorial. Anal Chim Acta. (2021) 1147:38–55. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2020.12.025

62.

Pang Z Xu L Viau C Lu Y Salavati R Basu N et al . MetaboAnalystR 4.0: a unified LC-MS workflow for global metabolomics. Nat Commun. (2024) 15:3675. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-48009-6

63.

Xu S Bai C Chen Y Yu L Wu W Hu K . Comparing univariate filtration preceding and succeeding PLS-DA analysis on the differential variables/metabolites identified from untargeted LC-MS metabolomics data. Anal Chim Acta. (2024) 1287:342103. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2023.342103

64.

Wu Q Li J Sun X He D Cheng Z Li J et al . Multi-stage metabolomics and genetic analyses identified metabolite biomarkers of metabolic syndrome and their genetic determinants. EBioMedicine. (2021) 74:103707. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103707

65.

Miller HA Yin X Smith SA Hu X Zhang X Yan J et al . Evaluation of disease staging and chemotherapeutic response in non-small cell lung cancer from patient tumor-derived metabolomic data. Lung Cancer. (2021) 156:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2021.04.012

66.

Turgut F Awad AS Abdel-Rahman EM . Acute kidney injury: medical causes and Pathogenesis.J. Clin Med. (2023) 12:375. doi: 10.3390/jcm12010375

67.

Elmariah S Farrell LA Daher M Shi X Keyes MJ Cain CH et al . Metabolite profiles predict acute kidney injury and mortality in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Heart Assoc. (2016) 5:e002712. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002712

68.

Erdoğan Kablan S Yılmaz A Syed H Kocabeyoğlu SS Kervan Ü Özaltın N et al . Metabolomics profiling for diagnosis of acute renal failure after cardiopulmonary bypass. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. (2024) 38:e9728. doi: 10.1002/rcm.9728

69.

Wörheide MA Krumsiek J Kastenmüller G Arnold M . Multi-omics integration in biomedical research - a metabolomics-centric review. Anal Chim Acta. (2021) 1141:144–62. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2020.10.038

70.

Gong Y Ding W Wang P Wu Q Yao X Yang Q . Evaluating machine learning methods of Analyzing multiclass metabolomics. J Chem Inf Model. (2023) 63:7628–41. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.3c01525

71.

Zhang F Wang Q Xia T Fu S Tao X Wen Y et al . Diagnostic value of plasma tryptophan and symmetric dimethylarginine levels for acute kidney injury among tacrolimus-treated kidney transplant patients by targeted metabolomics analysis. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:14688. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32958-2

72.

Lee HS Kim SM Jang JH Park HD Lee SY . Serum 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid and ratio of 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid to serotonin as metabolomics indicators for acute oxidative stress and inflammation in vancomycin-associated acute kidney injury. Antioxidants (Basel). (2021) 10:895. doi: 10.3390/antiox10060895

73.

Tian M Liu X Chen L Hu S Zheng Z Wang L et al . Urine metabolites for preoperative prediction of acute kidney injury after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2023) 165:1165–1175.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2021.03.118

74.

Muhle-Goll C Eisenmann P Luy B Kölker S Tönshoff B Fichtner A et al . Urinary NMR profiling in Pediatric acute kidney injury-a pilot study. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:1187. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041187

Summary

Keywords

acute kidney injury, metabolomics, biomarker, bibliometric investigation, meta-analysis

Citation

Kai Z, Yun K, Su Y, Li J and Liu Y (2025) Metabolomics biomarkers and related pathways in acute renal injury: a bibliometric investigation, meta-analysis, and systematic review. Front. Med. 12:1679349. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1679349

Received

04 August 2025

Accepted

06 October 2025

Published

20 October 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Ying-Yong Zhao, Northwest University, China

Reviewed by

Wei Wei, Harbin Medical University, China

Hailing Zhao, China-Japan Friendship Hospital, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Kai, Yun, Su, Li and Liu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yuxiang Liu, liuyuxiang@tmu.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.