- 1Department of Nursing, Women and Children’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Xiamen University, Xiamen, Fujian, China

- 2School of Nursing, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 3Department of Interventional Radiology Center, School of Medicine, Xiamen Cardiovascular Hospital of Xiamen University, Fujian Branch of National Clinical Research Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Xiamen, Fujian, China

- 4Department of Breast Diseases, Women and Children’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Xiamen University, Xiamen, Fujian, China

- 5Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Women and Children’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Xiamen University, Xiamen, Fujian, China

Objective: To systematically evaluate stigma levels and its influencing factors among Chinese postoperative breast cancer patients, providing evidence for culturally adapted interventions.

Methods: Chinese and English databases, such as China Biology Medicine Disc (CBM), China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang Data Knowledge Service Platform (WangFang), China Science and Technology Journal Database (The VIP), Cochrane Library, PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Medline, Web of Science, and grey literature from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), were searched. The time limit of the search for literature on the factors affecting the level of stigma in Chinese postoperative breast cancer patients was from the establishment of the databases to 14 July 2025. Two researchers independently screened studies, extracted data, and assessed quality using AHRQ criteria. Meta-analyses were performed using Stata 18.0.

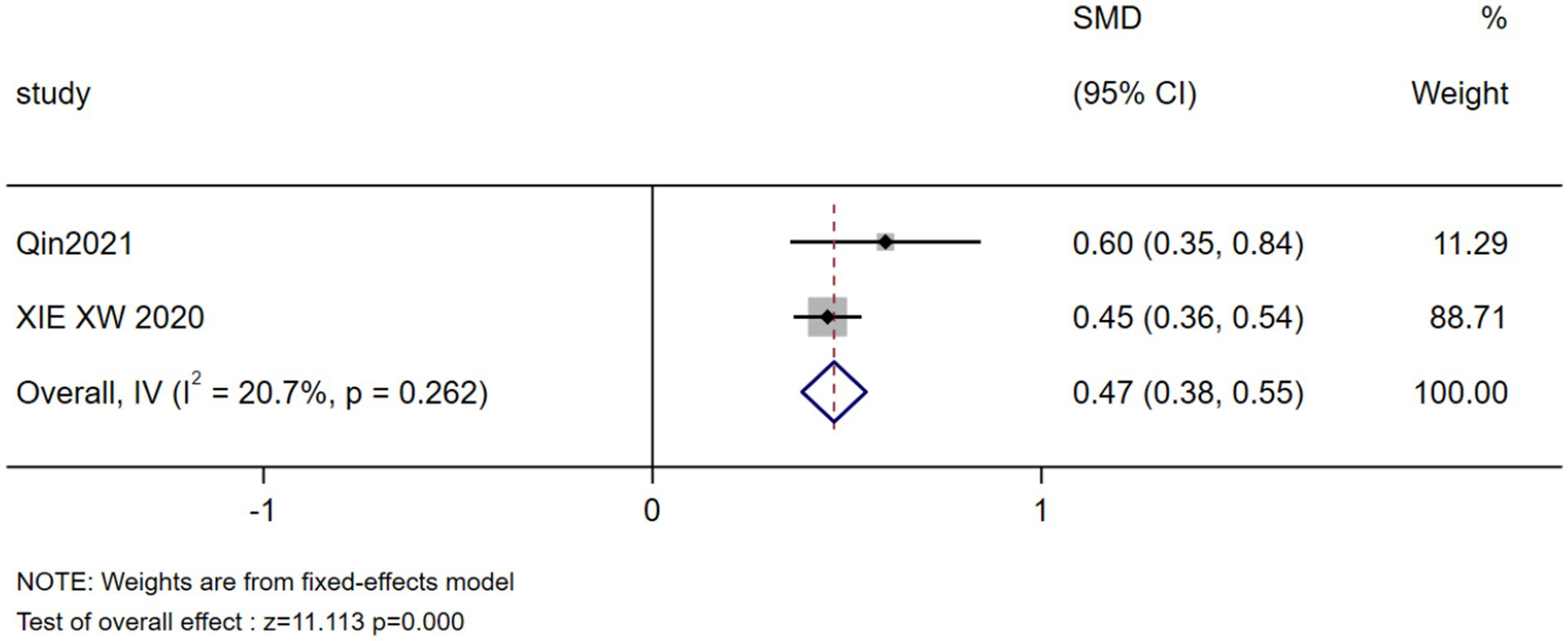

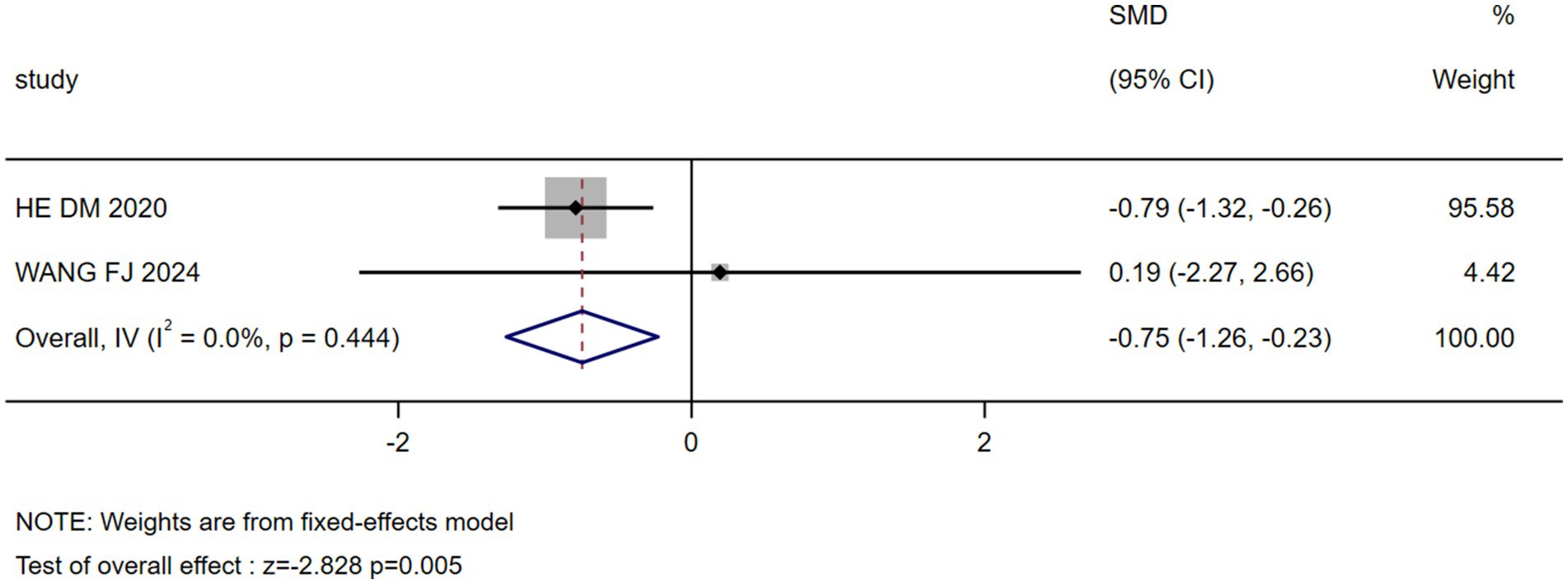

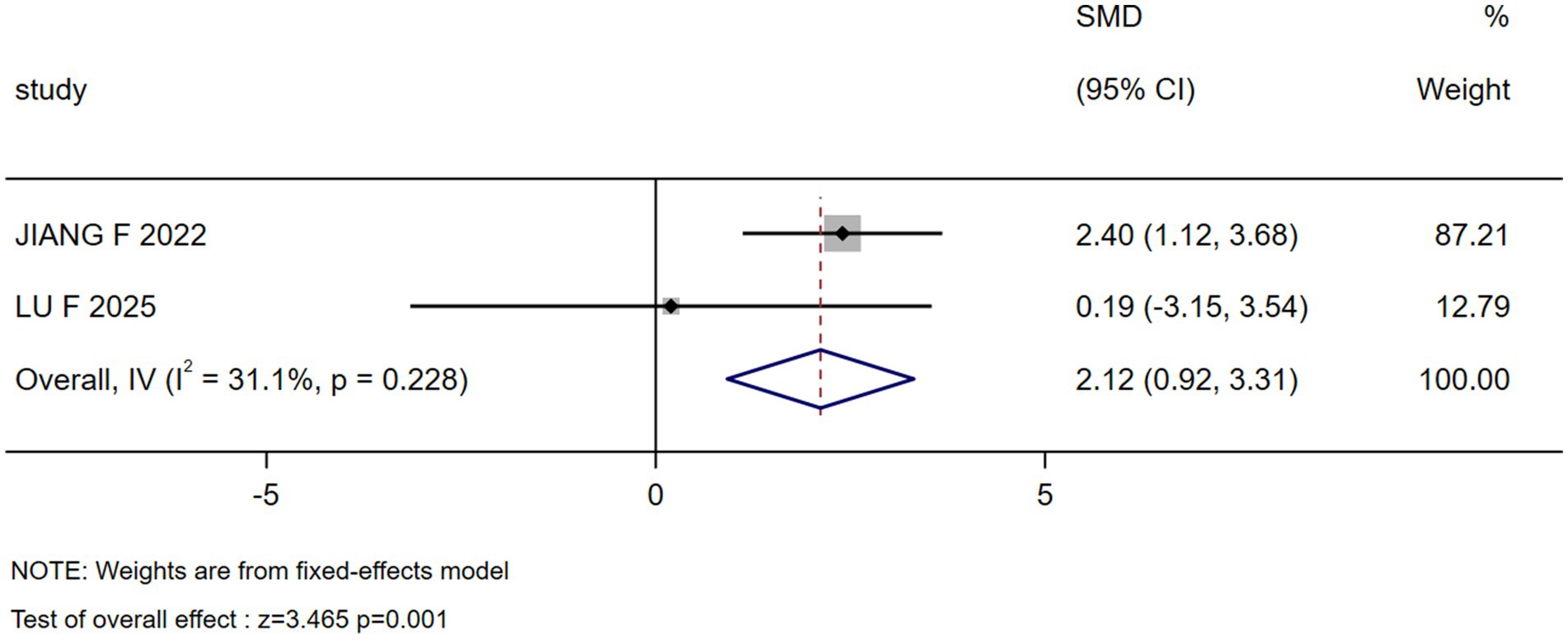

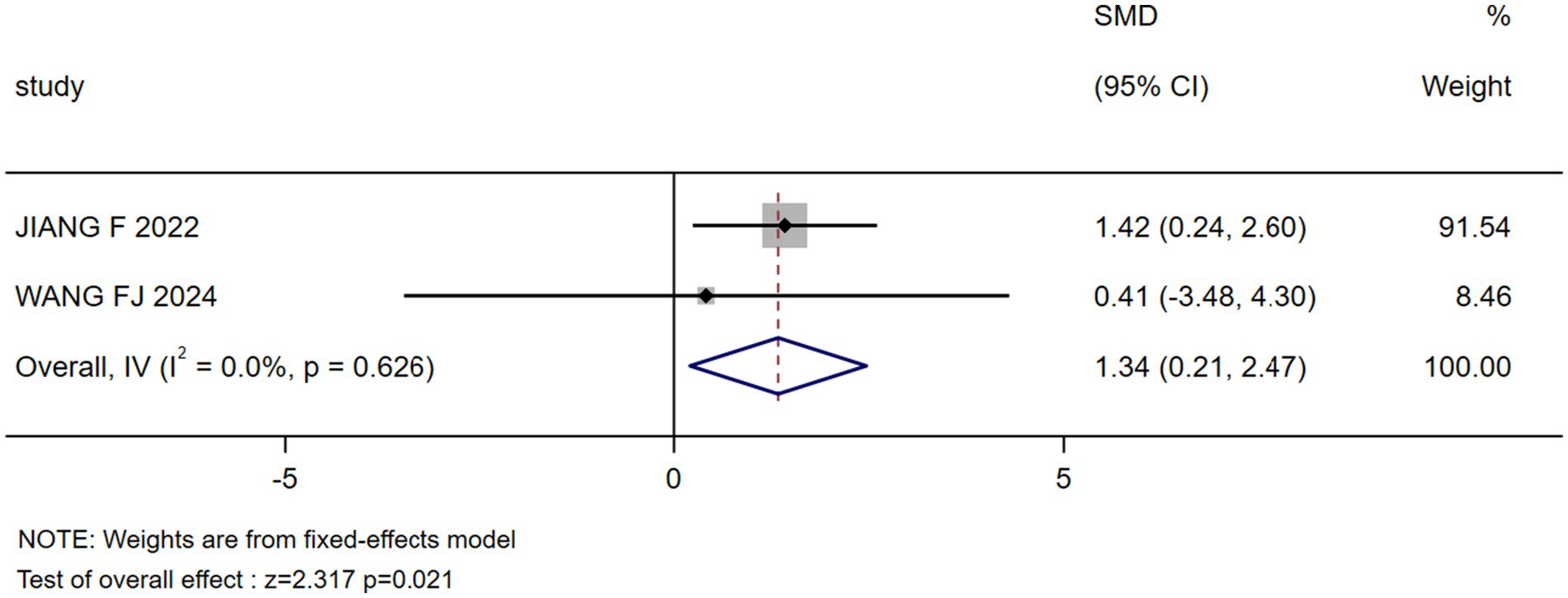

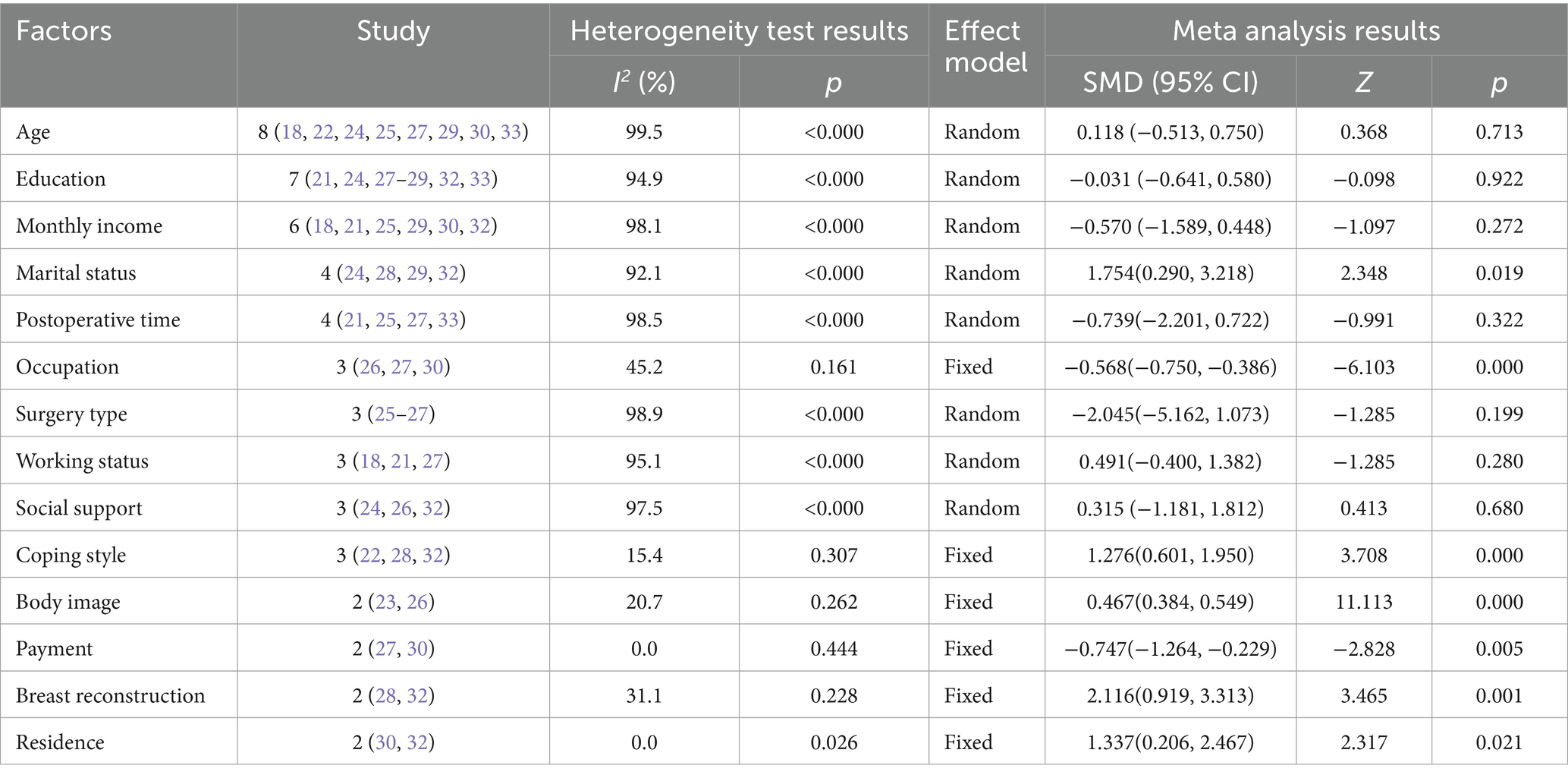

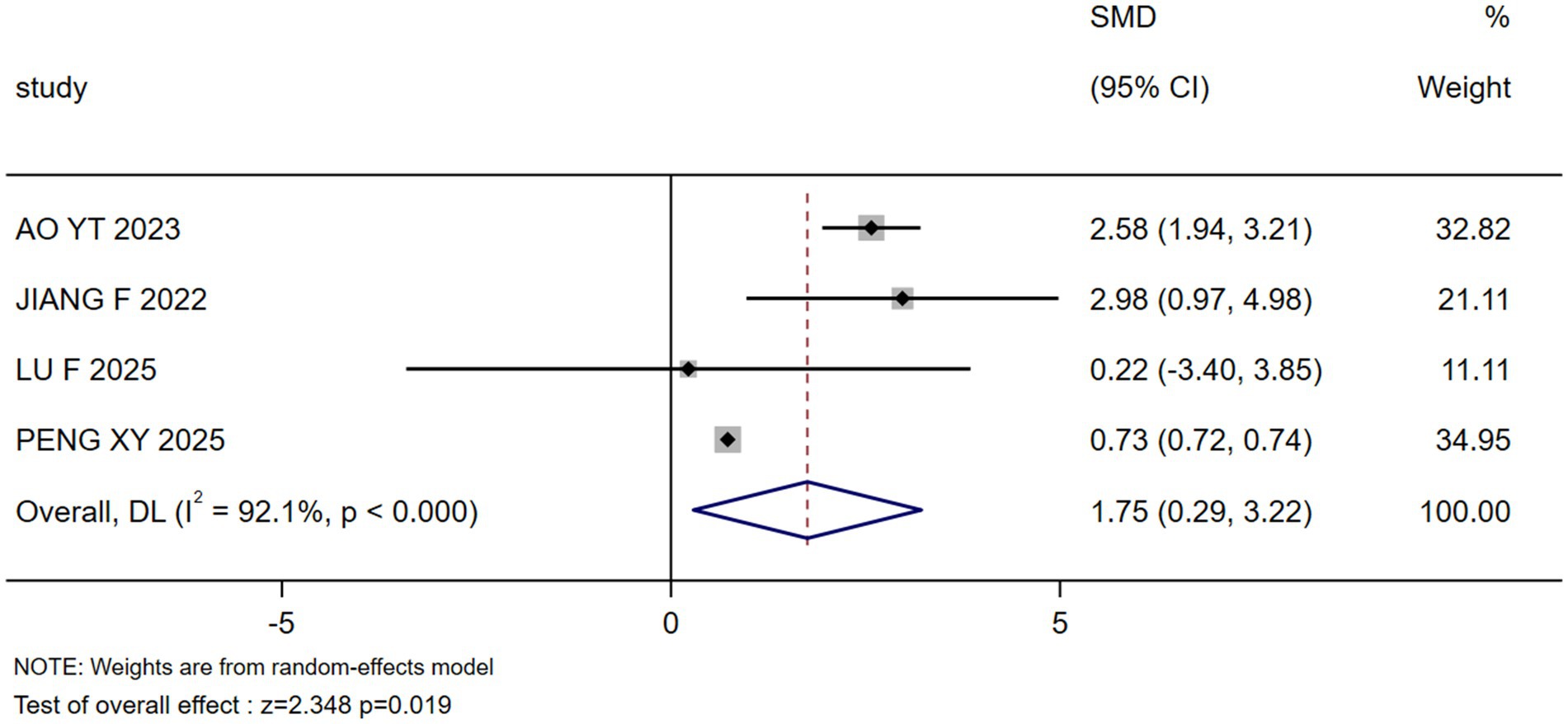

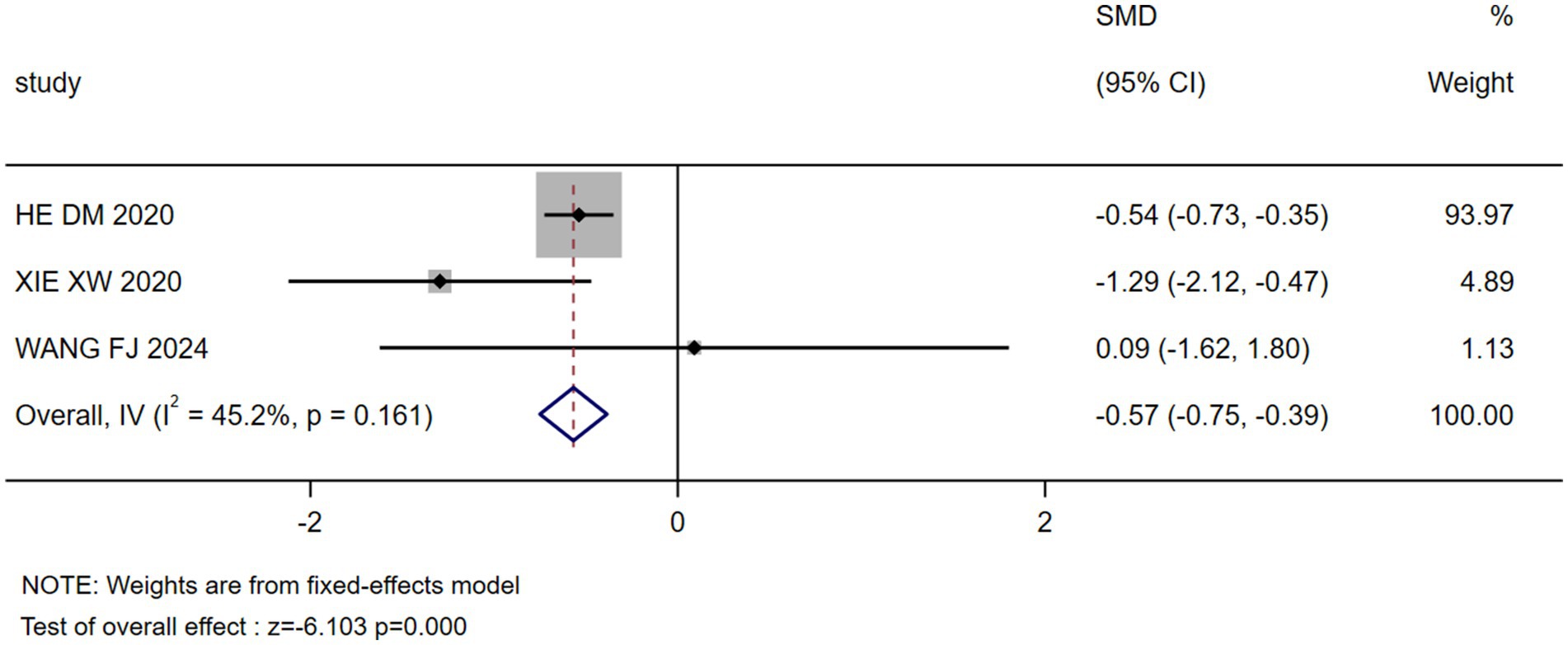

Results: Fourteen cross-sectional studies (total n = 2,873 patients) revealed a high stigma burden among Chinese postoperative breast cancer patients, with pooled Social Impact Scale (SIS) scores of 58.22 (95%CI: 55.30—61.15)—significantly exceeding rates in comparable populations. Meta-analysis identified seven culturally embedded predictors (p < 0.05): higher stigma was associated with unmarried/divorced/widowed status (SMD = 1.754), rural residence (SMD = 1.337), negative body image (SMD = 0.467), and yielding coping styles (SMD = 1.276); conversely, lower stigma correlated with occupational engagement (SMD = −0.568), breast reconstruction (SMD = −2.116), and self-payment status (SMD = −0.747). Paradoxically, spousal support intensified stigma (β = 1.336), while broader social support showed no significant association (p = 0.680).

Conclusion: Chinese breast cancer survivors face severe stigma shaped by Confucian familial norms, economic pressures, and healthcare disparities. Interventions must prioritize marital counseling, occupational reintegration, accessible reconstruction, and rural mental health services. Longitudinal studies are needed to establish causality.

Systematic review registration: CRD42024502898, https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/recorddashboard.

1 Introduction

Breast cancer, as the most prevalent malignant tumor among Chinese women, has seen its disease burden continuously exacerbated by population aging and lifestyle changes (1). The 2022 National Cancer Report indicates that China reports approximately 357,200 new breast cancer cases annually, with projections suggesting this number will exceed 500,000 by 2030 (2). A younger onset trend (peak incidence: 45–54 years) and high proportion of late-stage diagnoses (>30%) constitute distinctive national characteristics (3, 4). Although China’s age-standardized incidence rate (33.0/100,000) remains lower than Western countries, the annual increase rate over the past decade reached 3.9%, ranking among the highest globally (5, 6). More notably, while the 5-year relative survival rate for Chinese patients has significantly improved to 83% (7, 8), quality-of-life issues due to physiological impairment and psychological trauma are increasingly prominent (9). Currently, surgery remains the cornerstone of treatment for localized breast cancer (10), with the vast majority of patients undergoing surgical intervention. Therefore, understanding the psychosocial experiences of this specific postoperative population is critical.

China’s unique sociocultural context shapes the experience of stigma among breast cancer patients in distinct ways (11). Influenced by traditional gender-role expectations, breast loss is often perceived as a deficiency in female identity, which may lead patients to face a three-fold dilemma: marital crisis, workplace discrimination, and social isolation (12, 13). Notably, one study reported that 76.7% of Chinese patients conceal their condition due to fear of discrimination (14), which highlights a significant “burden of silence” within this population. This concealment can directly reduce treatment adherence and double the risk of depression. Current breast cancer research in China reveals two major gaps: First, insufficient localization of influencing factors. Existing international stigma prediction models (e.g., body image, social support) inadequately consider China-specific familial power structures and urban–rural healthcare disparities (15). Second, contradictory empirical conclusions: While some studies show no significant correlation between marital status and stigma (16), others indicate that being unmarried/divorced/widowed is an independent influencing factor for stigma in postoperative breast cancer patients, with stigma scores 5.425 times higher than married individuals (p < 0.05) (17, 18). These discrepancies highlight the moderating effect of cultural variables.

Therefore, this study will focus exclusively on the Chinese population for the first time, aiming to integrate evidence on stigma influencing factors in mainland China through systematic review and meta-analysis, to provide an evidence base for analysing how healthcare system characteristics regulate stigma and constructing China-specific intervention strategies.

2 Methods

2.1 Registration and protocol

This review has been registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), and the registered number is CRD42024502898. This systematic review was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement (19).

2.2 Search strategy

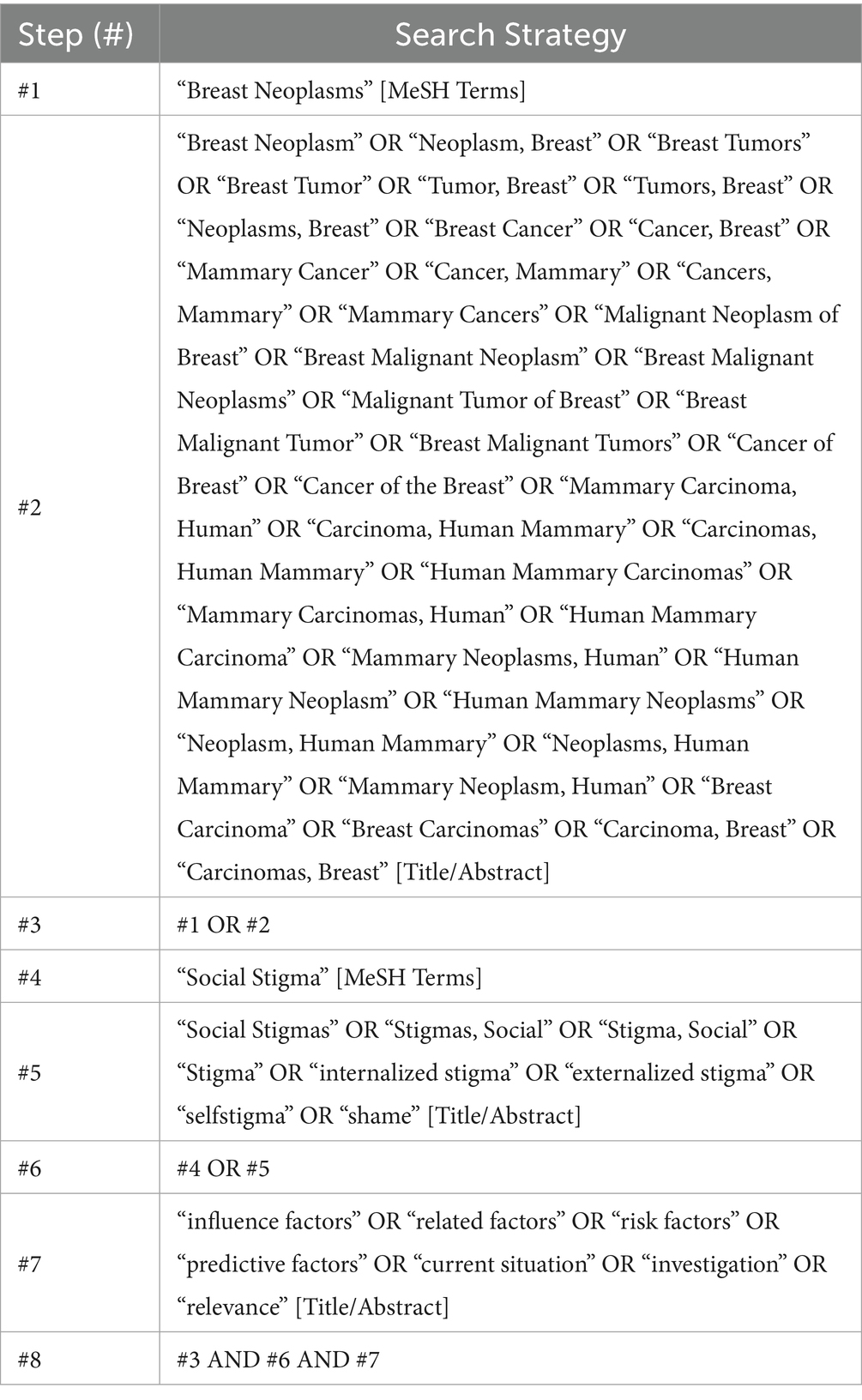

The Chinese and English databases searched were as follows: (a) the Chinese databases included China Biology Medicine Disc (CBM), China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang Data Knowledge Service Platform (WangFang), and China Science and Technology Journal Database (The VIP); (b) the English databases included Cochrane Library, PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Medline, and Web of Science; and (c) grey databases were also searched, including the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The search included all observational studies that described the level of stigma and factors influencing it in postoperative breast cancer patients. The search period was from the establishment of each database to 14 July 2025. Table 1 shows an example of one of the databases searched, namely, PubMed. The search formula and related information are detailed in Supplementary material 1.

2.3 Eligibility criteria

2.3.1 Inclusion criteria

(1) Study design: Observational studies (case–control, cohort, cross-sectional) reporting current stigma status and its influencing factors in Chinese postoperative breast cancer patients.

(2) Participants: Chinese breast cancer patients (≥18 years old) with histologically confirmed diagnosis who underwent surgical treatment.

(3) Outcome measures:

• Report the level of stigma and include the application of at least one stigma-related scales

• Report results in Linear regression models: Providing standardized regression coefficients (β) with SEs or complete data for SMD calculation (means, SDs, sample sizes)

(4) Predictors: Report ≥2 statistically quantified predictors of stigma.

(5) Data availability: Sufficient data including Means ± SDs or regression coefficients with SEs.

(6) Languages: Publications in Chinese or English.

(7) Geographic scope: Studies conducted in mainland China.

2.3.2 Exclusion criteria

1. Duplicate publications from the same author/research group.

2. Journal articles duplicating dissertation content.

3. Unrecoverable incomplete data (after contacting authors).

4. Studies reporting only significance levels (p-values) without quantitative effect measures.

5. Studies using non-validated or non-standard stigma assessments.

2.4 Literature screening and data extraction

All potentially relevant studies were imported into Covidence for the purpose of eliminating duplicate studies and subsequent screening. Two reviewers (Yan WJ and Zhou HJ) independently conducted a comprehensive literature search and imported the relevant articles into the literature management software EndNote. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were strictly followed to determine the selection of the literature, which was cross-checked for accuracy. Any disagreements between the researchers were resolved through discussion, with consultation from a third researcher (Zhang YF) when necessary. Additionally, data extraction was performed separately by two researchers (Yan WJ and Zhou HJ), including information such as authors, year of publication, country of origin, study design, stigma identification methods, sample size, stigma scores, and influential factors.

2.5 Literature quality evaluation

The included literature was independently evaluated by two researchers (Yan WJ and Zhou HJ) according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ) criteria for assessing the risk of bias in observational studies (20). The evaluation consisted of 11 entries, with a score of 0 to 3 indicating low quality, 4 to 7 moderate quality, and 8 to 11 high quality. After completing the quality evaluation, the results were discussed and negotiated, and the quality of the included literature was categorized as high quality (Grade A), moderate quality (Grade B), and low quality (Grade C). Grade C literature was excluded.

2.6 Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 18.0 software. The analytical approach comprised two distinct phases addressing separate research objectives.

2.6.1 Phase 1: meta-analysis of stigma scores

A single-arm synthesis was conducted to estimate pooled mean stigma scores. Raw mean values with corresponding standard deviations (or standard errors) served as the primary data for synthesis. The DerSimonian-Laird random-effects model was applied to account for anticipated heterogeneity across studies. The use of means and standard deviations for meta-analysis is conventional for continuous outcome data and assumes that the stigma scores from the included studies approximate a normal distribution and can be treated as parametric data. Subgroup analyses were stratified by measurement scale type to examine instrument-specific effects. Results were expressed as weighted mean values with 95% confidence intervals.

2.6.2 Phase 2: meta-analysis of influencing factors

For factors reported in <2 studies, descriptive synthesis was performed by reporting individual study effect sizes without quantitative pooling. For factors reported in ≥2 studies, standardized mean differences (SMD) were computed as the comparative effect measure. All factors were analyzed using inverse-variance weighted fixed-effects or random-effects models, selected based on the results of heterogeneity tests.

2.6.3 Heterogeneity assessment

Between-study heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistic, with statistical significance assessed via Cochran’s Q-test employing an α-threshold of 0.10. Model selection adhered to predefined criteria whereby random-effects models were applied when I2 ≥ 50% or Q-test p-value ≤0.10, while fixed-effects models were utilized when I2 < 50% and Q-test p-value >0.10.

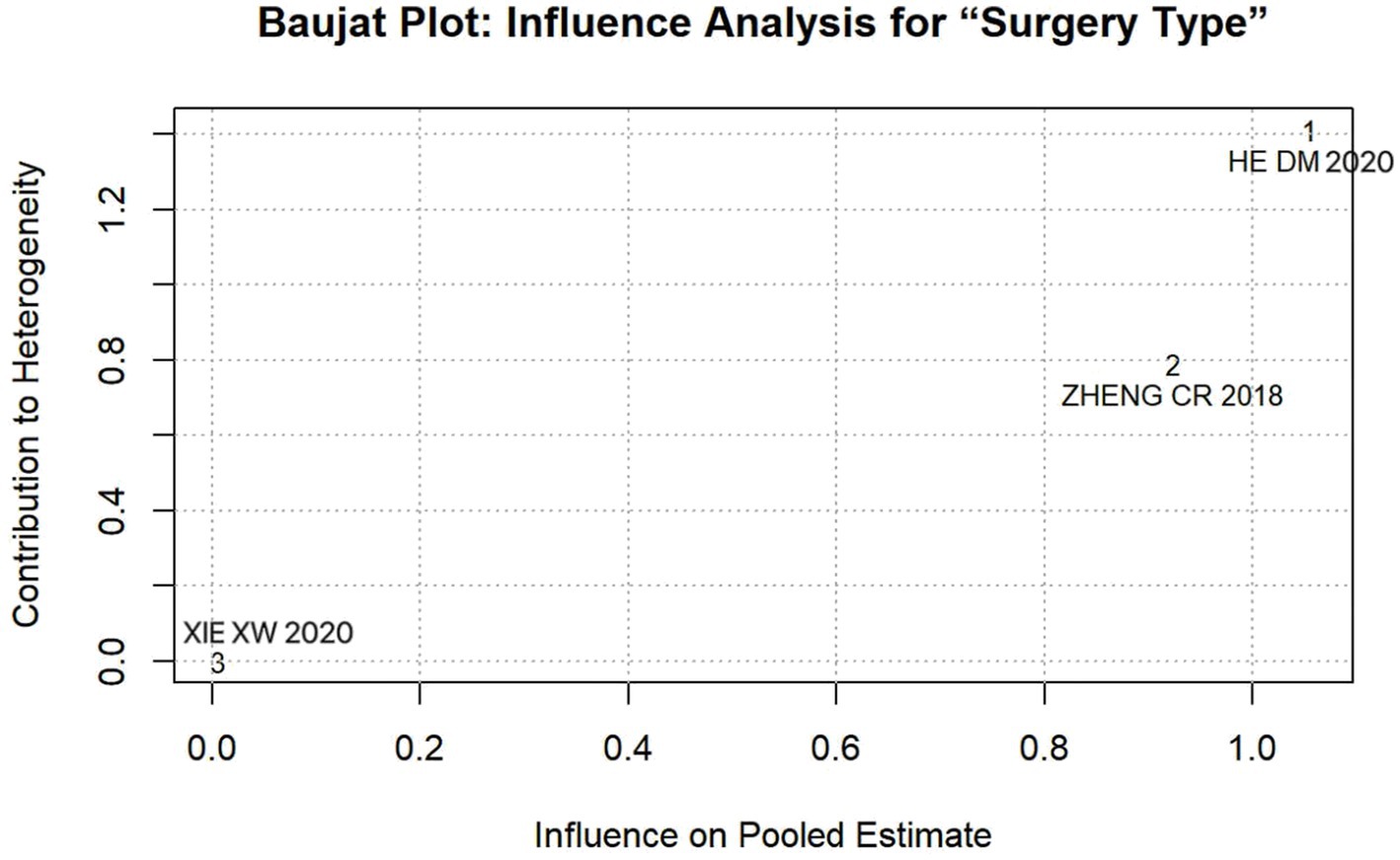

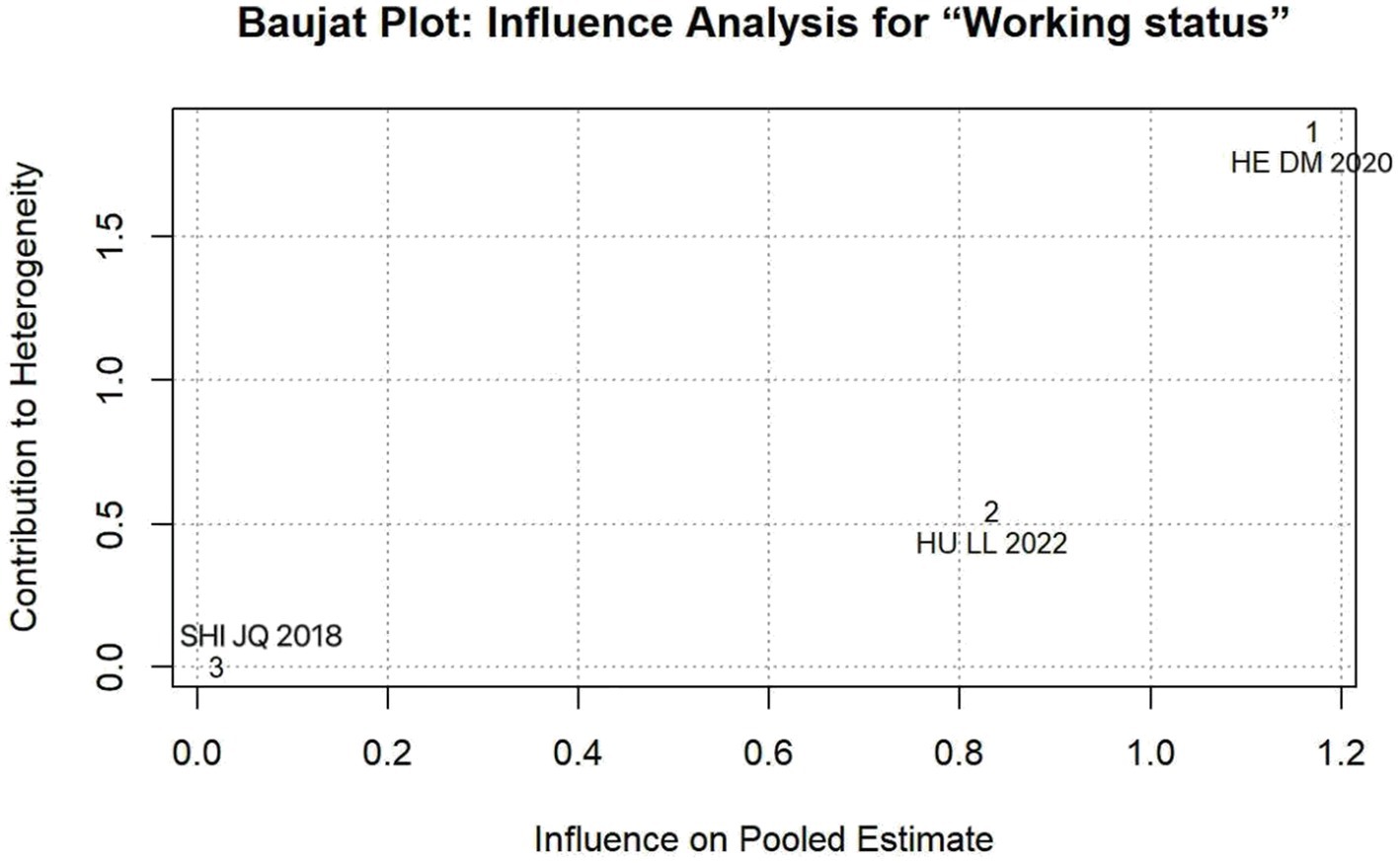

2.6.4 Sensitivity analysis

To evaluate result robustness, we performed model consistency comparisons between fixed and random effects estimates, supplemented by sequential exclusion procedures involving iterative removal of individual studies. For factors where sensitivity analysis indicated instability and substantial heterogeneity (I2 ≥ 50%), we further employed Baujat plots to objectively identify and visualize outlying studies that exerted a disproportionate influence on both the pooled effect size and the between-study heterogeneity. This method provides a quantitative and graphical assessment of influence, complementing the sequential exclusion approach. All influence diagnostics were conducted using the R software (version 4.5.1).

2.6.5 Publication bias assessment

Potential publication bias was assessed using visual funnel plot inspection applied to factors with ≥10 studies, where p > 0.10 indicated no significant bias.

3 Results

3.1 Study selection

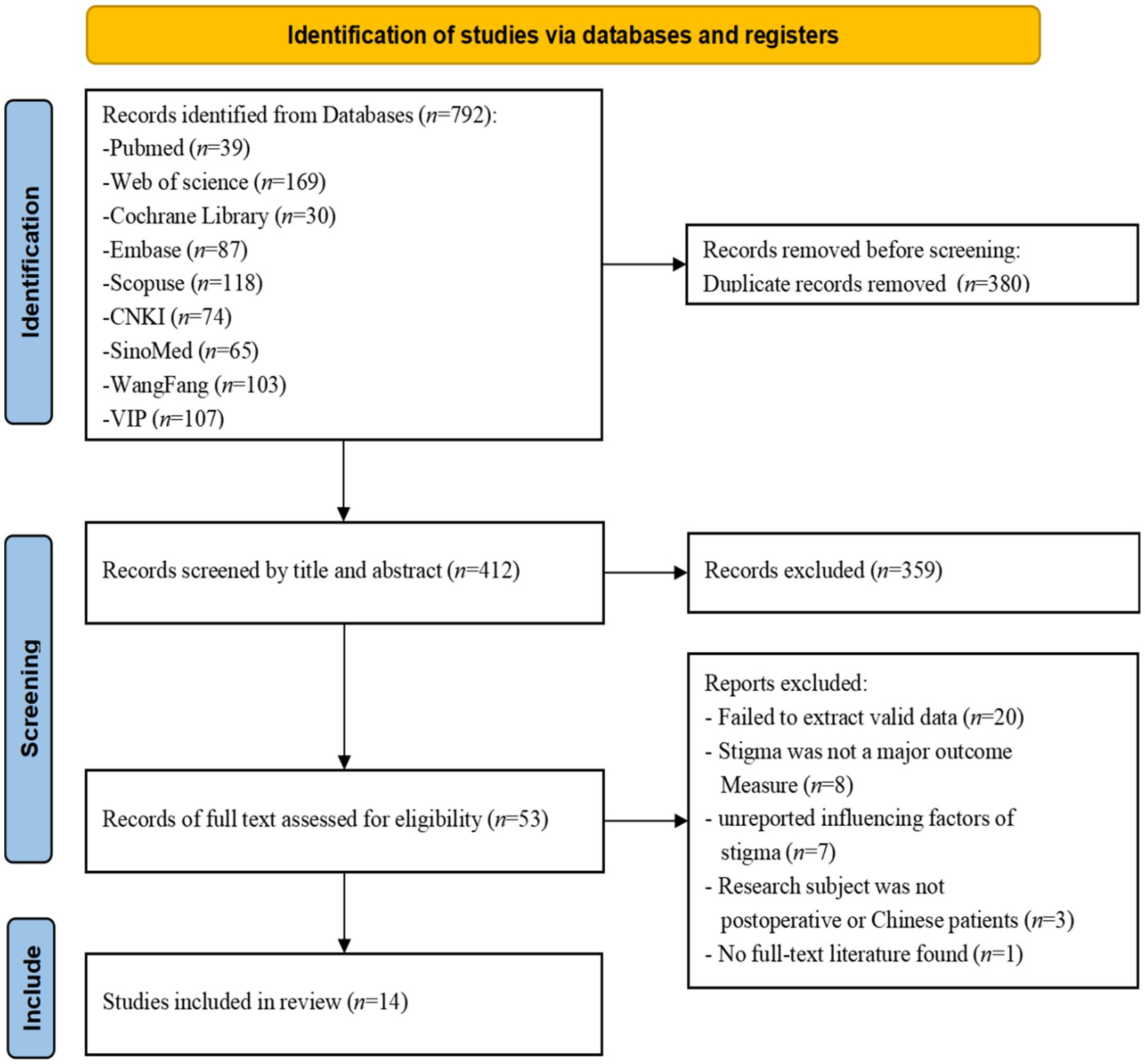

A total of 792 potentially eligible literature articles were extracted from various databases, of which 380 were removed based on duplicated records. The remaining 412 articles were checked manually by Covidence and EndNote software; 359 articles were eliminated after reading the titles and abstracts, and 39 articles were eliminated after reading the entire texts. Ultimately, 14 studies with a total of 2,873 patients satisfied the inclusion requirements (see Figure 1). The excluded studies and reasons are detailed in Supplementary material 2.

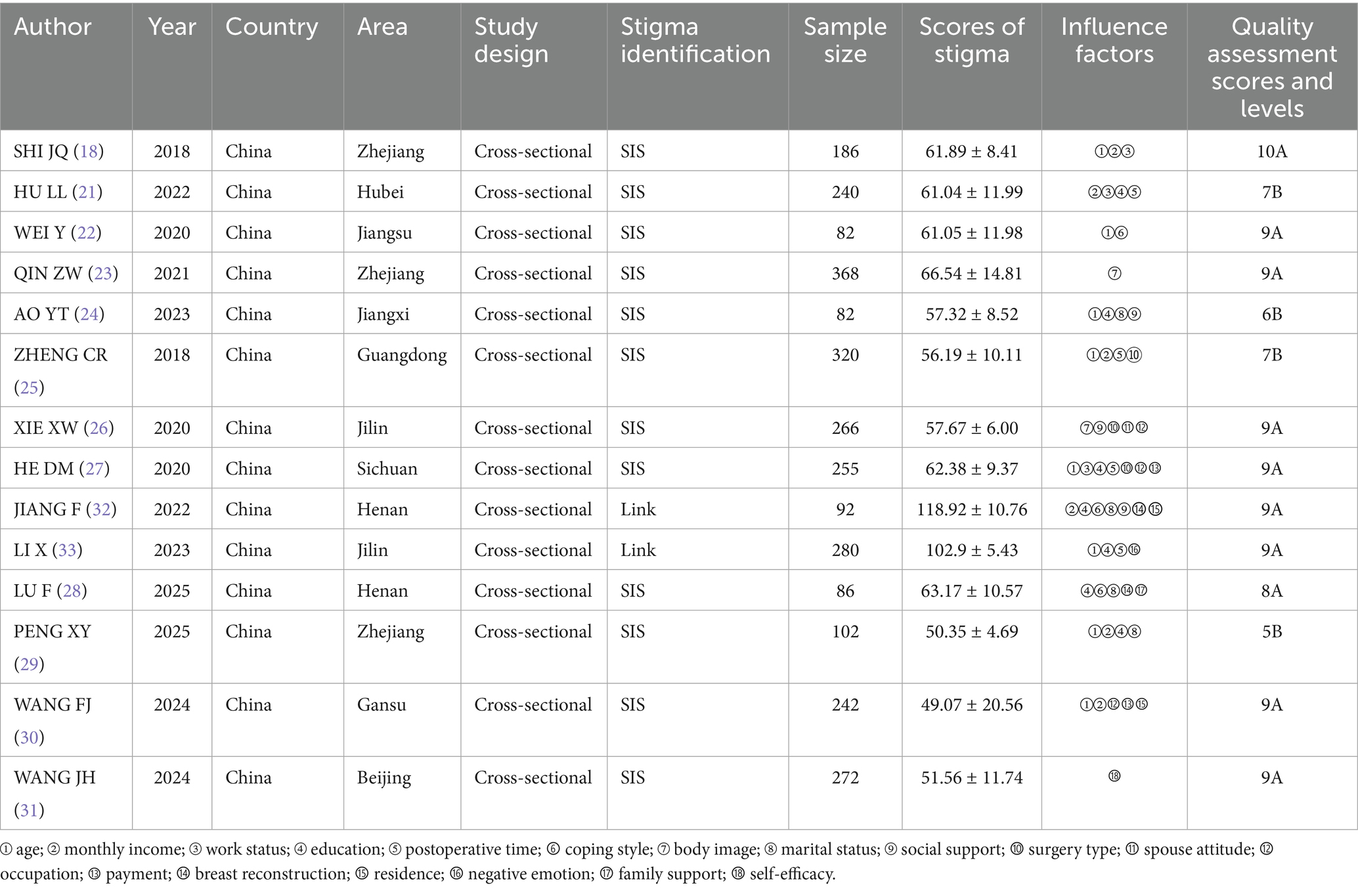

3.2 Basic information and methodological quality assessment of the included studies

The 14 included studies were cross-sectional studies, and in terms of tools for evaluating patients’ stigma, 12 studies (18, 21–31) used the Social Impact Scale (SIS), two studies (32, 33) used the Link Stigma Series Scale (Link). Quality evaluation was performed according to the AHRQ’s recommended criteria for evaluating the risk of bias regarding observational studies. This resulted in 14 included studies that were all Grade A and Grade B literature. The details are shown in Table 2. The original data of the article are detailed in Supplementary material 3.

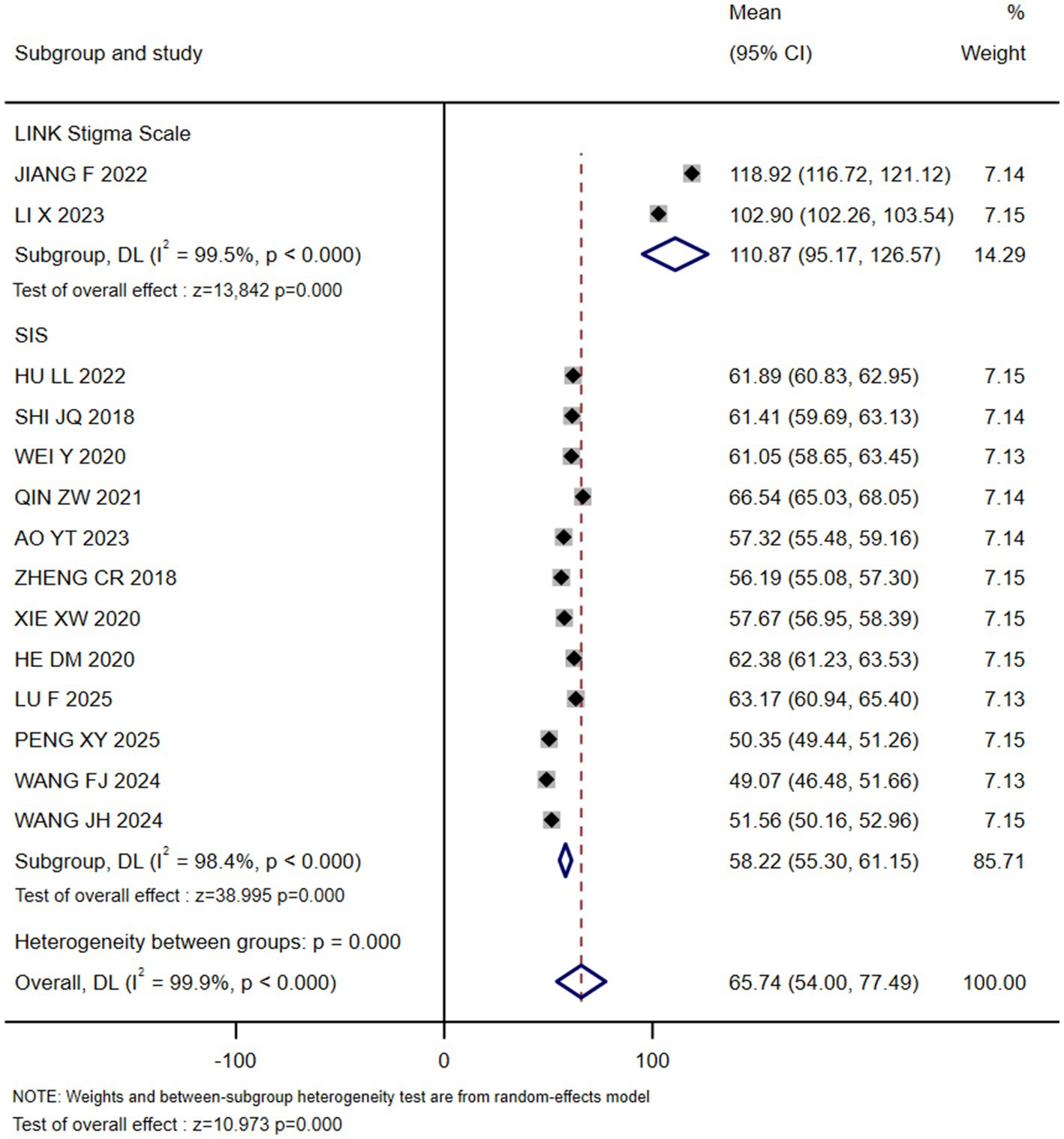

3.3 Meta-analysis results

3.3.1 Status of stigma in postoperative breast cancer patients

12 studies used the SIS (18, 21–31), and the subgroup concordance results showed a stigma score of 58.22 (55.30, 61.15); and two studies used the Link Stigma Series Scale (32, 33), and the subgroup concordance results showed a stigma score of 110.87 (95.17, 126.57) (see Figure 2). The results of all 14 studies indicated that stigma was prevalent to varying degrees in postoperative breast cancer patients.

3.3.2 Influencing factors of stigma in postoperative breast cancer patients

3.3.2.1 Descriptive statistics

Eighteen potential influencing factors were identified across the 14 included studies. The following influencing factors were each reported by a single study: XIE XW et al. (26) found that spouse attitude was an independent predictor of stigma (β = 1.336, p < 0.01). Notably, when the spouse attitude was “caring,” the level of stigma significantly increased. Concurrently, the study by LI X et al. (33) reported a strong positive correlation between the total score of negative emotions and the sense of stigma (r = 0.530, p < 0.01). On the other hand, protective factors were also shown to effectively reduce these feelings. LU F et al. (28) found that good family support could enhance patients’ courage and confidence in facing external pressure, thereby reducing postoperative stigma (β = 0.277, p < 0.001). Similarly, WANG JH et al. (30) confirmed that the total score of self-compassion was significantly negatively correlated with stigma (r = −0.349, p < 0.01), which can independently explain 12.2% of the variation in stigma (R2 = 0.122, p < 0.001).

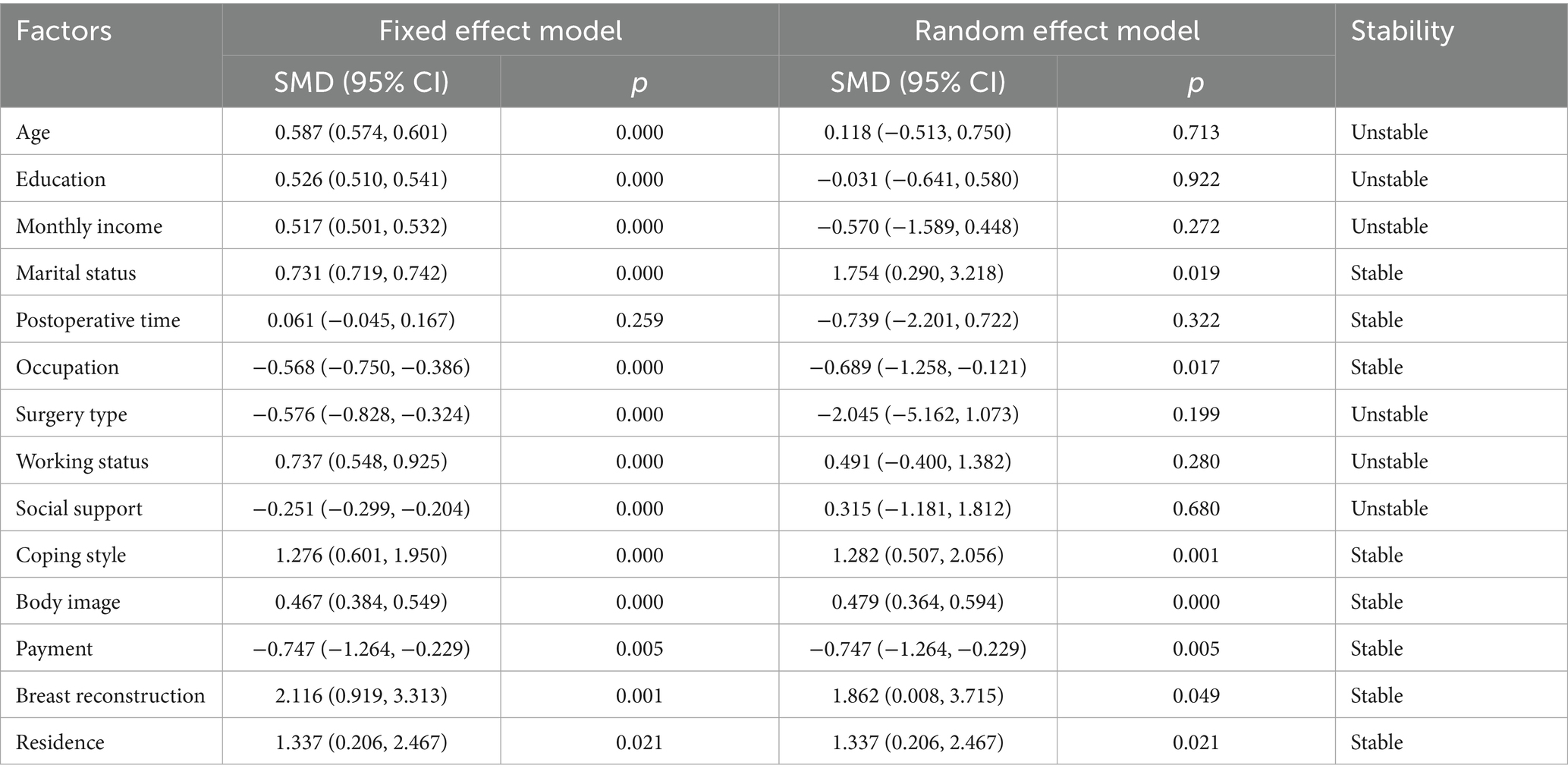

3.3.2.2 Meta-analysis findings

The results of the meta-analysis showed that marital status, occupation, coping style, body image, payment, breast reconstruction and residence were the influencing factors of stigma in postoperative breast cancer patients (p < 0.05), as shown in Table 3. Forest plots visualizing seven significant associations are presented in Figures 3–9.

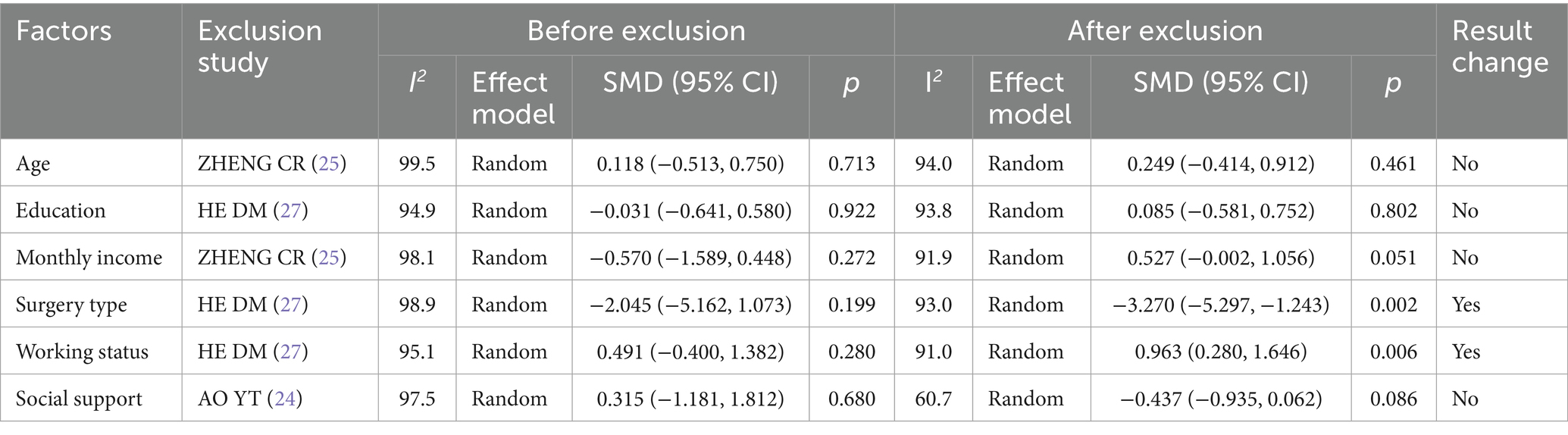

3.3.2.3 Sensitivity analysis

The results of the sensitivity analysis indicated that the effect (95% CI) and p value of six influencing factors, namely age, education, monthly income, surgery type, working status, and social support, underwent significant changes between fixed- and random-effects models, indicating instability (see Table 4). To pinpoint the source of this instability, we performed leave-one-out analyses (see Table 5). This procedure revealed that the study by He et al. (27) was solely responsible for the instability in the factors “surgery type” and “working status.” Specifically, the exclusion of He et al. (27) transformed the pooled effect for both factors from non-significant to statistically significant (p < 0.05), while simultaneously reducing heterogeneity substantially. This finding was objectively confirmed using Baujat plots for influence diagnostics (Figures 10, 11). The plots visually identified He et al. (27) as a clear outlier, located in the upper-right quadrant, indicating its strong and disproportionate influence on both the overall result and heterogeneity for these two factors. Therefore, the results for “surgery type” and “working status” should be interpreted with caution due to their dependence on a single, influential study, highlighting the need for future research to verify these associations.

Table 4. Sensitivity analysis of influencing factors of stigma in breast cancer patients after surgery.

Table 5. Exclusion analysis of influencing factors of stigma instability in patients after breast cancer surgery.

3.3.2.4 Publication bias

There were no influencing factors of ≥10 in the included literature in this study. Considering that the effectiveness of the publication bias analysis was low and had little significance when the number of included literature was less than 10, this study did not conduct publication bias analysis one by one for the influencing factors.

4 Discussion

4.1 Interpretation of results and comparison with previous research

This systematic review and meta-analysis synthesizes evidence on stigma among Chinese postoperative breast cancer patients, revealing a clinically significant burden. Pooled results from studies utilizing the Social Impact Scale (SIS) indicate a stigma score of 58.22 (95%CI: 55.30–61.15), which is significantly higher than that observed in Indian postoperative breast cancer patients [41.00 (IQR: 38.00–44.20)] (34). This finding echoes China’s distinctive “burden of silence” phenomenon—specifically, the fact that 76.7% of patients conceal their condition due to fear of discrimination (15) further underscores the profound impact of stigma within this population. Notably, this study has additionally identified seven culturally embedded influencing factors, which provide a critical perspective for explaining the uniqueness of stigma among Chinese breast cancer patients.

However, it is crucial to acknowledge that the measurement tools used to assess stigma exhibit certain limitations across the included studies. While instruments such as the SIS and Link Stigma Scale were widely used, they are general stigma measures and may not fully capture the breast cancer-specific and culturally nuanced aspects of stigma experienced by Chinese women. In China, validated disease-specific instruments such as the Breast Cancer Stigma Scale (BCSS-China) have been developed (35) and demonstrate higher sensitivity to the lived experiences of breast cancer patients. Similarly, international tools like the Breast Cancer Stigma Assessment Scale (BCSAS) have been recently validated (36). The absence of such tailored instruments in current observational studies represents a significant limitation, potentially leading to underestimation of stigma’s cultural and gender-specific dimensions. Future research should prioritize the adoption of these validated, context-sensitive tools to enhance measurement accuracy and intervention relevance.

The most striking finding concerns marital status. Contrary to some studies framing married status as a risk factor (37), unmarried/divorced/widowed Chinese postoperative breast cancer patients had significantly higher stigma than their married counterparts (SMD = 1.754, p = 0.019) in this study. We hypothesize that this inversion may stem from Confucian familial expectations, where being unmarried or losing a spouse can lead to a profound loss of social identity and support within a family-centric culture (38). Furthermore, the paradoxical finding that spousal concern intensified stigma (β = 1.336, p < 0.01) (26) could be interpreted as such support translating into implicit pressure to fulfill traditional gender roles post-mastectomy, rather than providing unconditional emotional solace. This suggests a culturally specific mechanism that warrants further qualitative investigation. Similarly, occupational engagement reduced stigma (SMD = −0.568, p < 0.001), underscoring work’s role in preserving identity—a phenomenon amplified in China’s collectivist culture where social contribution defines individual worth (39). Beyond these social and cultural correlates, body image (SMD = 0.467, p < 0.001) and breast reconstruction (SMD = 2.116, p = 0.001) emerged as core drivers of stigma. The 30% late-diagnosis rate (3, 4) necessitates radical surgeries, exacerbating “body integrity stigma.” While reconstruction alleviated this burden, its limited accessibility (especially in rural areas) reflects disparities in healthcare resource allocation. Residence-based disparities were quantifiable: rural patients suffered higher stigma (SMD = 1.337, p = 0.021), likely compounded by fragmented mental health services and entrenched cancer taboos (40).

Two findings warrant methodological reflection: First, social support showed no significant association with postoperative breast cancer stigma (p = 0.680), contradicting findings from Kang et al. (41), who reported that social support, as a critical coping resource, was significantly associated with reduced psychosocial distress related to cancer stigma among Korean breast cancer survivors (r = −0.49, p < 0.001). We cautiously put forward the explanation that the concept of “obligatory support” prevalent in Chinese families, where the concept of support is often intertwined with familial duties and expectations for rapid recovery, might potentially dilute its protective effect. This hypothesis regarding the qualitative nature, rather than the quantity, of support could explain the discrepancy and should be tested in future research. Second, economic factors showed differential effects: while monthly income level was not significantly associated with stigma (SMD = −0.570, p = 0.272), self-payment status emerged as a significant predictor (SMD = −0.747, p = 0.005). This suggests that economic influence may operate indirectly financial toxicity from out-of-pocket expenses could amplify perceived familial burden, particularly within the context of Chinese familial responsibility ethics (42).

It is also worth noting that the conceptual understanding of stigma in breast cancer has been advanced by recent theoretical work. Wu et al. (43) conducted a concept analysis specific to breast cancer patients, identifying key attributes such as impaired body image, negative stereotypes, avoidance, and experienced discrimination. Their work provides a valuable theoretical framework that aligns with several of our empirical findings, particularly regarding the roles of body image and social isolation. Incorporating this conceptual model helps contextualize our results within a broader theoretical narrative and strengthens the interpretative depth of this review. Furthermore, while our study focuses specifically on postoperative patients, it is important to acknowledge that the vast majority of women diagnosed with localized breast cancer undergo surgery as part of standard treatment (10). This contextual detail reinforces the relevance and generalizability of our findings to the broader population of breast cancer patients in China. Finally, a recent meta-analysis examined correlates of stigma across a broader range of cancer types (44). While that review included breast cancer patients, it did not focus specifically on the postoperative phase nor on the Chinese cultural context. Our study thus adds value by providing a more targeted analysis of the unique factors operating in this specific subgroup and setting.

4.2 Implications for practice, policy and research

For clinical practice, culturally adapted interventions are imperative: Psychological support should prioritize unmarried/divorced women through acceptance-commitment therapy to address identity crises, while integrating spouses into counseling to reframe care as empowerment rather than obligation (45). Concurrently, surgical decision-making must emphasize shared deliberation on breast reconstruction, highlighting its psychosocial benefits, with standardized preoperative protocols to address body image concerns (46).

Policy reforms must bridge structural gaps: Expanding insurance reimbursement to cover reconstruction surgery and evidence-based psychosocial interventions (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy) is critical. Pilot programs integrating mental health services into rural cancer survivorship care should be prioritized. Anti-stigma efforts require media collaboration to normalize breast cancer narratives, potentially adopting strategies from established campaigns like Hong Kong’s Pink Revolution (47).

Research priorities should center on mechanistic studies that employ mixed methods to unpack paradoxes, intervention trials that develop stepped-care models, and longitudinal designs that track stigma trajectories from the point of diagnosis through to survivorship.

4.3 Strengths and limitations

This study demonstrates significant strengths. Methodologically, it strictly adhered to the PRISMA statement and AHRQ criteria, with all included studies rated moderate-to-high quality (Grades A/B). The dual-reviewer screening and data extraction process, augmented by third-party arbitration for discrepancies, enhanced reliability. Substantively, it represents the first systematic review and meta-analysis focusing exclusively on postoperative breast cancer patients in mainland China, addressing the critical gap of cultural specificity absent in international models. Furthermore, robust sensitivity analyses confirmed the stability of seven core influencing factors (marital status, occupation, coping style, body image, payment method, breast reconstruction, residence), reinforcing their credibility.

However, limitations merit consideration: (1) Causality and Design Limitation: The cross-sectional design of all included studies prevents definitive causal conclusions regarding the relationships between influencing factors and stigma. Furthermore, the variability in the definition of the “postoperative” phase across studies may have introduced heterogeneity, as stigma mechanisms may differ across these phases. (2) Heterogeneity and Measurement Limitations: Significant unresolved heterogeneity was observed for certain factors such as surgery type and working status. While sensitivity analyses improved stability after excluding outlier studies, these associations require further validation. Additionally, the reliance on general stigma scales (e.g., SIS, Link) rather than breast cancer-specific instruments (e.g., BCSS-China, BCSAS) may have limited the cultural and clinical sensitivity of stigma measurement. (3) Publication Bias Assessment Limitation: In accordance with Cochrane guidelines, this study only assessed potential publication bias via funnel plot asymmetry for factors where ≥10 studies were available. For the majority of influencing factors with fewer studies, statistical evaluation of small-study effects was not feasible, and thus the results for these factors should be interpreted with appropriate caution.

5 Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis confirms that Chinese postoperative breast cancer patients face a significant stigma burden, which is higher than in some other populations and linked to China’s “burden of silence” due to fear of discrimination. Key culturally specific influencing factors include marital status, occupational engagement, coping style, body image, breast reconstruction, rural residence, and self-payment status, with paradoxical effects noted in spouses’ attitudes and social support. These findings highlight the need for culturally adapted clinical interventions, policy reforms, and further research to mitigate stigma and improve patients’ psychosocial well-being.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

WY: Data curation, Writing – original draft. HZ: Writing – original draft. YH: Writing – review & editing. YZ: Writing – review & editing. SW: Writing – review & editing. XY: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Science and Technology Plan Project for High-quality Development of Health Commission of Xiamen (2024GZL-QN025).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all authors of the original studies included in this systematic review.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1681487/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Bray, F, Laversanne, M, Sung, H, Ferlay, J, Siegel, RL, Soerjomataram, I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. (2024) 74:229–63. doi: 10.3322/caac.21834

2. Han, B, Zheng, R, Zeng, H, Wang, S, Sun, K, Chen, R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2022. J Natl Cancer Cent. (2024) 4:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jncc.2024.01.006

3. Zhang, X, Yang, L, Liu, S, Cao, LL, Wang, N, Li, HC, et al. Interpretation on the report of global cancer statistics 2022. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. (2024) 46:710. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112152-20240416-00152

4. Arnold, M, Morgan, E, Rumgay, H, Mafra, A, Singh, D, Laversanne, M, et al. Current and future burden of breast cancer: global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast. (2022) 66:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2022.08.010. Epub 2022 Sep 2

5. Cao, MD. Interpretation on the global cancer statistics of GLOBOCAN 2022. Chin J Front Med Sci. (2024) 16:1–5. doi: 10.12037/YXQY.2024.06-01

6. Zheng, RS, Chen, R, Han, BF, Wang, SM, Li, L, Sun, KX, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2022. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. (2024) 46:221–31. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112152-20240119-00035

7. Gradishar, WJ, Moran, MS, Abraham, J, Abramson, V, Aft, R, Agnese, D, et al. Breast cancer, version 3.2024, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. (2024) 22:331–57. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2024.0035

8. Tao, X, Li, T, Gandomkar, Z, Brennan, PC, and Reed, WM. Incidence, mortality, survival, and disease burden of breast cancer in China compared to other developed countries. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. (2023) 19:645–54. doi: 10.1111/ajco.13958

9. Hou, LJ, Liu, LY, Wang, F, Yu, LX, and Yu, ZG. Psychological problems in breast cancer patients should be taken seriously. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. (2024) 62:110–5. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112139-20231016-00175

10. Miller, KD, Nogueira, L, Devasia, T, Mariotto, AB, Yabroff, KR, Jemal, A, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, (2022). CA Cancer J Clin. (2022) 72:409–36. doi: 10.3322/caac.21731

11. Greenlee, H, DuPont-Reyes, MJ, Balneaves, LG, Carlson, LE, Cohen, MR, Deng, G, et al. Clinical practice guidelines on the evidence-based use of integrative therapies during and after breast cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. (2017) 67:194–232. doi: 10.3322/caac.21397

12. Khan, TM, Leong, JP, Ming, LC, and Khan, AH. Association of knowledge and cultural perceptions of Malaysian women with delay in diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer: a systematic review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. (2015) 16:5349–57. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.13.5349

13. Fan, ZM. (2023). Case work intervention study on reducing stigma in cancer patients. Wuhan, China: Huazhong Agricultural University.

14. Amini-Tehrani, M, Zamanian, H, Daryaafzoon, M, Andikolaei, S, Mohebbi, M, Imani, A, et al. Body image, internalized stigma and enacted stigma predict psychological distress in women with breast cancer: a serial mediation model. J Adv Nurs. (2021) 77:3412–23. doi: 10.1111/jan.14881

15. Fujisawa, D, Umezawa, S, Fujimori, M, and Miyashita, M. Prevalence and associated factors of perceived cancer-related stigma in Japanese cancer survivors. Jpn J Clin Oncol. (2020) 50:1325–9. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyaa135

16. Kong, RH. (2015). The status and influencing factors of stigma in young patients with breast cancer. Jinan, China: Shandong University.

17. Xiao, HM, Zhou, XY, Zhang, XJ, Li, N, and Li, XZ. Influencing factors of stigma in breast cancer patients after operation and its relationship with self-esteem, quality of life and psychosocial adaptability. Prog in Mod Biomed. (2021) 21:4522–6. doi: 10.13241/j.cnki.pmb.2021.23.026

18. Shi, JQ, Ma, JL, Hu, FH, and Ye, HZ. Correlation of stigma, coping style and self-esteem among patients after breast modified radical mastectomy. Chin J Mod Nurs. (2018) 24:332–5. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-2907.2018.03.020

19. Page, MJ, McKenzie, JE, Bossuyt, PM, Boutron, I, Hoffmann, TC, Mulrow, CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 29:372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

20. Dougherty, DMAgency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Alphascript Publishing (2001) 73:81–83.

21. Hu, LL, Zhou, XF, Wang, YB, Zhou, Y, Ren, HH, and Yao, F. Influencing factors of stigma after modified radical mastectomy in patients with breast cancer. Chin Med Her (2022) 19:100–103. Chinese.

22. Wei, Y, Chen, LL, and Tao, FL. Correlation between stigma, coping style and self-esteem in patients undergoing modified radical mastectomy for breast cancer. Nurs Prac Res. (2020) 17:78–80. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-9676.2020.04.029

23. Qin, ZW, Shen, C, Wei, WF, and Chen, SQ. Relationship between self-identity, self-image and stigma of breast cancer patients. Nurs Rehabil Mag. (2021) 20:68–71. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-9875.2021.11.019

24. Ao, YT. Analysis of the current situation and risk factors of postoperative stigma in patients with breast cancer surgery. Med Equip (2023) 36:145–147. Chinese. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-2376.2023.01.047

25. Zheng, CR, and Wang, HZ. Analysis of stigma status and influencing factors of breast cancer patients after operation. J Nurs (2018) 25:7–9. Chinese. doi: 10.16460/j.issn1008-9969.2018.02.007

26. Xie, XW. (2020). Study on the relationship between body image level, social support and stigma in patients with breast cancer after surgery. Jilin, China: Yanbian University.

27. He, DM. Study on the mediating effect of coping modes between patients’ stigma and marital quality after radical mastectomy. Nanchong: Chuanbei Medical College (2020).

28. Lu, F, Jiao, SS, Lu, SC, and Niu, ZZ. Analysis of related factors of stigma in patients with early breastcancer after radical mastectomy based on linear regressionand to formulate intervention measures. J Med Forum. (2025) 46:1034–8. doi: 10.20159/j.cnki.jmf.2025.10.006

29. Peng, XY. Investigation on the status Ouo of stigma and its analysis of influencing factors in patients with BreastCancer after modified radical mastectomy. Refl Rehabil Med. (2025) 6:171–3. doi: 10.16344/j.cnki.10-1669/r4.2025.02.044.29

30. Wang, FJ. A study on postoperative stigma, self-efficacy and quality of life in patients with breast. Gansu: Gansu University of Chinese Medicine (2024).

31. Wang, JH, Bai, P, and Wei, YT. The status of postoperative stigma of breast cancer patients and its correlation with self-compassion in a grade-a tertiary hospital in Beijing. Med Soc. (2024) 37:138–44. doi: 10.13723/j.yxysh.2024.06.020

32. Jiang, F, Zhou, F, and Xiao, H. The related factors of disgust feeling after radical correction breast cancer in the young and mid aged patients. J Int Psychl. (2022) 49:1074–7. doi: 10.13479/j.cnki.jip.2022.06.001

33. Li, X.. (2023). The study on the status quo and influencing factors of shame sense in postoperative patients with breast cancer and its correlation with negative emotions and coping styles. Jilin, China: Beihua University.

34. Tripathi, L, Datta, SS, Agrawal, SK, Chatterjee, S, and Ahmed, R. Stigma perceived by women following surgery for breast Cancer. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. (2017) 38:146–52. doi: 10.4103/ijmpo.ijmpo_74_16

35. Bu, X, Li, S, Cheng, ASK, Ng, PHF, Xu, X, Xia, Y, et al. Breast Cancer stigma scale: a reliable and valid stigma measure for patients with breast Cancer. Front Psychol. (2022) 13:841280. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.841280

36. Cenit-García, J, Buendia-Gilabert, C, Contreras-Molina, C, Puente-Fernández, D, Fernández-Castillo, R, and García-Caro, MP. Development and psychometric validation of the breast Cancer stigma assessment scale for women with breast Cancer and its survivors. Healthcare (Basel). (2024) 12:420. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12040420

37. Yıldız, K, and Koç, Z. Stigmatization, discrimination and illness perception among oncology patients: a cross-sectional and correlational study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. (2021) 54:102000. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2021.102000

38. Jiang, C, Wang, Y, Jiang, W, Cai, J, Wang, L, and Wu, X. Metaphors and stigma in Confucian culture: a qualitative study of Cancer risk communication dilemmas for Cascade screening among hereditary Cancer families from China. Psychooncology. (2025) 34:e70205. doi: 10.1002/pon.70205

39. Mao, B, Shen, Y, Chen, Y, Zhou, P, and Pan, Y. Experiences of healthcare professionals returning to work post breast cancer diagnosis in China: a descriptive qualitative study. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:1938. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-82893-8

40. Jiang, MF, Gao, J, Yang, L, Lu, YM, Qian, J, and Li, JZ. The mediating role of loneliness and social support between stigma and social avoidance in rural breast cancer survivors. Chin J Gen Pract. (2023) 21:2000–4. doi: 10.16766/j.cnki.issn.1674-4152.003276

41. Kang, NE, Kim, HY, Kim, JY, and Kim, SR. Relationship between cancer stigma, social support, coping strategies and psychosocial adjustment among breast cancer survivors. J Clin Nurs. (2020) 29:4368–78. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15475

42. Hu, RY, Wang, JY, Chen, WL, Zhao, J, Shao, CH, Wang, JW, et al. Stress, coping strategies and expectations among breast cancer survivors in China: a qualitative study. BMC Psychol. (2021) 9:26. doi: 10.1186/s40359-021-00515-8

43. Wu, J, Zeng, N, Wang, L, and Yao, L. The stigma in patients with breast cancer: a concept analysis. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. (2023) 10:100293. doi: 10.1016/j.apjon.2023.100293

44. Tang, WZ, Yusuf, A, Jia, K, Iskandar, YHP, Mangantig, E, Mo, XS, et al. Correlates of stigma for patients with breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. (2022) 31:55. doi: 10.1007/s00520-022-07506-4

45. Mesko, B, deBronkart, D, Dhunnoo, P, Arvai, N, Katonai, G, and Riggare, S. The evolution of patient empowerment and its impact on health care's future. J Med Internet Res. (2025) 27:e60562. doi: 10.2196/60562

46. Williams, T, Fine, K, Duckworth, E, Adam, T, Bozigar, C, McFarland, A, et al. Patient decision aids in breast surgery and breast reconstruction reduce decisional conflict: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. (2025) 213:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10549-025-07752-0

47. Hong Kong Cancer Fund (2020) Shop for charity in pink revolution’s “shop for pink” programme. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Cancer Fund. Available online at: https://www.cancer-fund.org/en/blog/shop-charity-pink-revolutions-shop-pink-programme/

Keywords: breast neoplasms, social stigma, risk factors, Chinese patients, systematic review, meta-analysis

Citation: Yan W, Zhou H, Huang Y, Zhang Y, Wang S and Yu X (2025) Factors influencing stigma in Chinese postoperative breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 12:1681487. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1681487

Edited by:

Zodwa Dlamini, Pan African Cancer Research Institute (PACRI), South AfricaReviewed by:

Atefeh Zandifar, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, IranJudit Cenit Garcia, Granada Biosanitary Research Institute (ibs.GRANADA), Spain

Copyright © 2025 Yan, Zhou, Huang, Zhang, Wang and Yu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yinying Huang, eG1meWh5eUAxNjMuY29t; Yunfei Zhang Mjc5MDY5Njk3NkBxcS5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

‡OCRID: Huang Yinying, orcid.org/0000-0002-5232-0861

Zhang Yunfei, orcid.org/0000-0002-8132-5426

Wenjuan Yan

Wenjuan Yan Hongjuan Zhou

Hongjuan Zhou Yinying Huang1*‡

Yinying Huang1*‡ Yunfei Zhang

Yunfei Zhang

![Forest plot displaying the standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals for three studies: WEI Y 2020, JIANG F 2022, and LU F 2025. The overall effect estimate is 1.28 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.60 to 1.95. WEI Y 2020 has an SMD of 1.11, JIANG F 2022 has 2.01, and LU F 2025 has 0.19. Weights are from a fixed-effects model, with overall heterogeneity statistics of \[I^2 = 15.4%\] and \(p = 0.307\). The test of overall effect shows z = 3.708, p = 0.000.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1681487/fmed-12-1681487-HTML/image_m/fmed-12-1681487-g005.jpg)