Abstract

Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE) is defined as a clinical-radiological-physiological syndrome characterized by upper-lobe emphysema and fibrosis predominantly in the lower lobes. The diagnosis of CPFE remains challenging due to the opposing pathophysiological effects of emphysema and fibrosis, which can mask their characteristic clinical and imaging features. Although an international committee proposed standardized terminology for CPFE in 2022, uniform diagnostic criteria and optimal management strategies have not yet been established. Patients with CPFE exhibit reduced overall survival and higher mortality compared to those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). This may be due to increased disease severity, as assessed by CT findings (the extent of fibrosis and emphysema), advanced age, and associated complications such as lung cancer, acute exacerbations, and pulmonary arterial hypertension. This narrative review synthesizes the literature on CPFE from 1990 to 2024, covering its historical background, epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation, diagnostic features (imaging and pulmonary function), disease course (diagnosis, prognosis, complications), and management.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), emphysema, and interstitial lung disease (ILD) are the most prevalent chronic respiratory conditions. Nonetheless, it is becoming increasingly acknowledged that certain individuals may have both emphysema and ILD. This condition is known as a combination of pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE). Originally described by Cottin et al., this condition features upper lung-predominant emphysema and lower lung-predominant fibrosis (1–4).

Although diagnostic criteria exist, the clinical identification of CPFE remains challenging. The challenge is exacerbated when assessing dyspneic patients, as CPFE-related anomalies may be obscured by comorbidities. Emphysema leads to a decrease in elastic recoil (i.e., increased compliance), whereas fibrosis results in enhanced elastic recoil (i.e.decreased compliance). When these opposing mechanisms balance each other, pulmonary function tests may show lung capacity and vital capacity measurements within normal ranges, thereby masking underlying severe pathology and leading to delayed or missed diagnosis (5).

.In this review, we summarize the clinical aspects of CPFE, including epidemiology, diagnostic features (including pulmonary fibrosis subtypes and functional assessment), characteristic imaging findings, treatments, complications, prognostic outcomes, and future directions.

Pathogenesis and risk factors

To date, the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of CPFE are unclear. Previous studies have shown that smoking is one of the risk factors for CPFE (6, 7). This exposure causes recurrent airway inflammation, facilitates immune complex accumulation in the lung interstitium, and disrupts inflammatory healing processes, cumulatively leading to pulmonary fibrosis. Concurrent small airway and alveolar epithelial damage from smoking triggers emphysematous changes, resulting in combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (Figure 1) (8–13). Long-term occupational exposure to asbestos, coal dust, talcum powder, trichloroethylene, pesticides, or welding fumes is associated with an elevated risk for CPFE development (14, 15). Furthermore, CPFE development is acknowledged in nonsmoking populations, especially among those with connective tissue diseases (CTD). Ariani et al. identified CPFE in 43 out of 470 individuals with systemic sclerosis by high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the chest. A multicenter investigation demonstrated markedly increased serum antinuclear antibody (ANA) levels in patients with CPFE relative to controls with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

Figure 1

The pathogenesis of emphysema and pulmonary fibrosis is initiated by persistent damage to lung tissue as a result of smoking or environmental exposure. (1) In pulmonary emphysema, the core mechanism involves a protease–antiprotease imbalance. Activated macrophages and neutrophils release excess proteases (e.g., MMP-9, neutrophil elastase), degrading alveolar structural components such as elastic fibers and collagen, ultimately leading to irreversible airspace enlargement. (2) In pulmonary fibrosis, chronic inflammation promotes TGF-β-dependent Smad2/3 phosphorylation and non-Smad signaling through alveolar epithelial cell injury and M2 macrophage polarization. This cascade drives fibroblast-to-myofibroblast differentiation and excessive deposition of ECM proteins (e.g., collagen I/III), resulting in honeycomb-like fibrotic lesions. Created in BioRender. Zeng, W. (2025) https://biorender.com/lrhpgdf.

Additionally, a recent population-based cohort analysis further revealed elevated CPFE prevalence among lung cancer patients, particularly those with comorbid rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (16–20). Together, these findings indicate that CTD may act as both a risk factor and a pathogenic component in CPFE; however, the link between CTD and CPFE remains inadequately defined. Significant knowledge gaps remain regarding the clinical characteristics, prognosis, and heterogeneity across CTD subtypes in the CPFE-CTD overlap syndrome. Therefore, focused mechanistic research and clinical validation studies are essential to elucidate the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms.

Emerging evidence indicates that genetic factors also contribute to the development of CPFE.

Several studies have implicated specific genetic factors, including peptidase D (PEPD), telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT), surfactant protein C (SFTPC), and adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette subfamily A member 3 (ABCA3) gene mutations (21–24). Telomeres, nucleoprotein complexes located at the termini of eukaryotic chromosomes, inhibit the activation of the DNA damage response at chromosomal ends (25, 26). Telomere dysfunction triggers DNA damage signaling, leading to p53 activation and culminating in cellular senescence and apoptosis. Persistent p53 activation during progressive telomere shortening exacerbates tissue-specific pathologies, including pulmonary fibrosis, aplastic anemia, and cirrhotic liver disease (27). Through Mendelian randomization analysis, Anna et al. established a causal link between telomere attrition and IPF, particularly in patients with co-existing IPF and COPD. In animal models exposed to cigarette smoke and bleomycin, mice with telomere shortening and dysfunction exhibited increased incidence and severity of both pulmonary emphysema and fibrosis.

Overall, CPFE pathogenesis involves a multifactorial interplay of environmental exposures and genetic determinants (28, 29).

Clinical features

Patients with CPFE are predominantly male smokers aged 60–80 years, who typically present with gradually progressive exertional dyspnea and a persistent chronic cough. Common clinical manifestations are presented in Figure 2. On physical examination, bibasilar fine inspiratory crackles are commonly observed, along with diminished breath sounds in the upper lung zones. Digital clubbing may also be present in some cases (2, 14, 30, 31).

Figure 2

Common clinical manifestations in patients with CPFE. Created in BioRender. Zeng, W. (2025) https://BioRender.com/7szy1o8.

Diagnostic testing

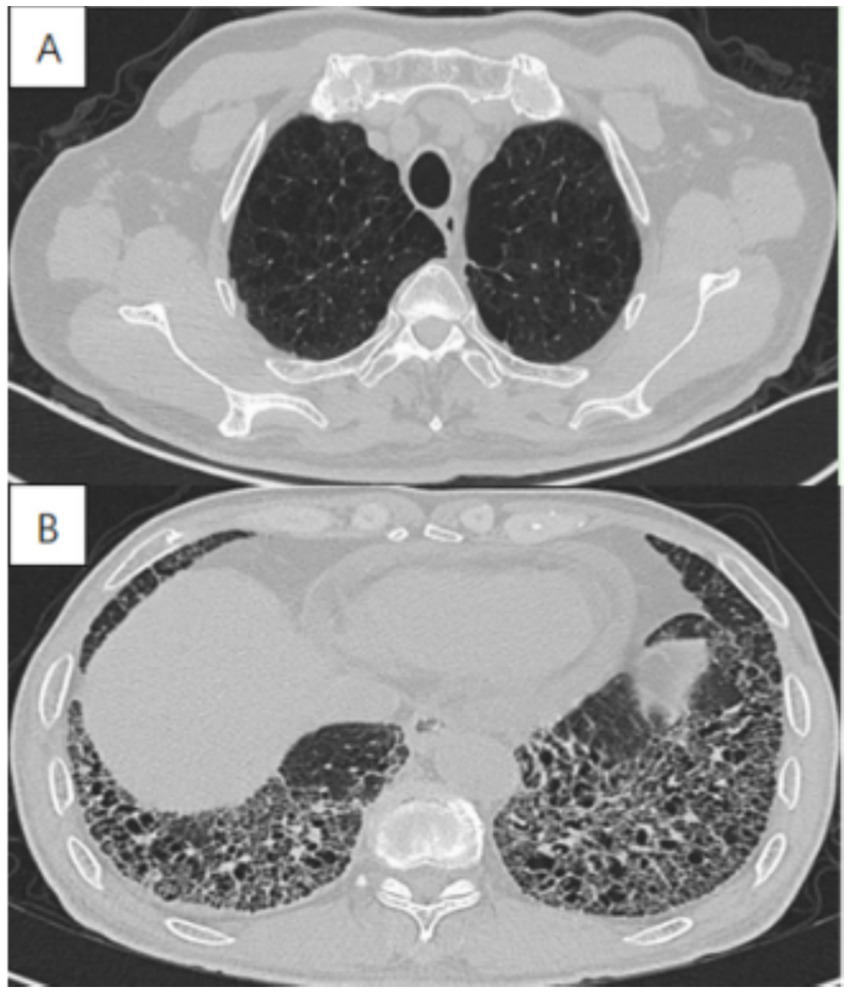

Imaging in CPFE reveals a characteristic dual pattern of upper-lobe emphysema and lower-lobe interstitial fibrosis (Figure 3). The emphysematous alterations in the upper lobes primarily consist of centrilobular and paraseptal bullae, exhibiting a distinct distribution pattern relative to pure COPD. Whereas centrilobular emphysema is predominant in COPD patients, paraseptal involvement is observed in approximately two-thirds of CPFE patients—a signature feature of this syndrome (Table 1) (14, 32, 33). While emphysema and fibrosis are usually distinguishable on HRCT, their differentiation can be challenging during early disease stages or when both pathologies are diffusely distributed throughout the lungs. Hyperinflation leads to reduced pulmonary vascular markings and diaphragmatic flattening, which are hallmark radiographic features of advanced emphysema. Conversely, advancing fibrosis reduces the lung volume, reversing emphysema-associated overinflation. Mori et al. reported that, in comparison with patients with COPD alone, CPFE patients had considerably elevated KL-6 levels (20). These findings suggest that KL-6 has potential as a practical screening indicator for CPFE. Therefore, future studies should establish validated biomarkers for early CPFE detection and develop tools to discriminate fibrotic from emphysematous components.

Figure 3

High-resolution computed tomography in a 72-year-old male with CPFE, showing (A) paraseptal emphysema in the upper lobe, (B) lower-zone-predominant fibrosis.

Table 1

| Component | Examples | Remark |

|---|---|---|

| Fibrosis | UIP | The most common type of fibrosis in CPFE |

| Fibrotic NSIP | ||

| Desquamative interstitial pneumonia | ||

| Unclassifiable fILD | ||

| AEF, SRIF, Etc. | ||

| Emphysema | Centrilobular | The most common emphysema type in CPFE |

| Paraseptal | ||

| Mixed (paraseptal and centrilobular) | ||

| Admixed (with fibrosis) | ||

| Thick-walled large cysts | ||

| Emphysema, pattern not specified. |

Imaging characteristics of pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema.

UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia; NSIP, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; fILD, fibrosing interstitial lung disease; AEF, airspace enlargement with fibrosis; SRIF, smoking-related interstitial fibrosis.

CPFE is characterized by distinct pulmonary function features that differentiate it from either emphysema or IPF alone. Ventilatory parameters—such as FVC, FEV₁—typically remain normal or show only mild impairment, whereas diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) is frequently severely reduced. Certain patients display isolated DLCO impairment; concurrently, emphysema evolves via elastic recoil deficiency-induced compliance elevation, resulting in airway collapse and alveolar dilation (3, 30, 34, 35). Conversely, pulmonary fibrosis increases elastic recoil and decreases compliance, thereby maintaining airway patency through traction. When these opposing effects counterbalance each other, patients with CPFE may exhibit preserved lung volumes and vital capacity, potentially resulting in delayed diagnosis.

Diagnosis

Currently, there are no universally accepted diagnostic criteria for CPFE (2). In practice, some studies define CPFE by quantifying emphysema severity, employing diagnostic thresholds of ≥10% or ≥20% emphysema concurrently with ≥10% or ≥15% fibrosis (Table 2) (36–40). The most authoritative consensus to date, which was jointly issued in 2022 by the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS), and the Japanese Respiratory Society, now serves as the widely recognized clinical guideline for the CPFE (41).

Table 2

| Phase | The subsequent phase of research (2005–2022) | Quantitative Imaging Thresholds | Landmark Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial conceptualization Phase(2005) |

|

Absence of a clearly defined quantitative threshold | Cottin et al. (2) |

| The subsequent research stage (2005–2022) |

|

Diagnostic thresholds adopted: ① Emphysema: LAA-950 > 10% ② Pulmonary fibrosis >15% involvement of total lung volume |

Kim et al. (70); Jacob et al. (12) |

| The standardized consensus development process (2022) | Requires concurrent presence of both:

|

— | Cottin et al. (41) |

Diagnostic criteria for CPFE across different temporal periods.

Future large-scale, multicenter cohort studies are needed to establish critical thresholds for emphysema and pulmonary fibrosis in CPFE, such as AI-driven automated lesion segmentation combined with HRCT density histograms and airway parameter analysis. To guide targeted interventions, CPFE patients are categorized based on the combined severity of emphysema and fibrosis. In those with predominant emphysema, inhaled pharmacotherapy forms the mainstay of treatment, whereas patients with predominant fibrosis receive combination antifibrotic therapy.

Furthermore, additional research is necessary to investigate blood biomarkers(such as KL-6 and SP-D) for objective quantification of lesion extent. Such efforts should also aim to develop a multidimensional CPFE staging system that incorporates imaging, functional, and clinical parameters, and to create a phenotype-based individualized treatment decision tree for evidence-based targeted interventions.

Prognosis and complications

Previous research has demonstrated that the median survival of CPFE patients varies from 0.9 to 8.5 years (33, 42). Prognostic determinants include age, CT-defined disease severity (extent of fibrosis and emphysema), and major comorbidities such as lung cancer (LC), acute exacerbation(AE), and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) (41).

PAH is present in 47–90% of CPFE patients, with a mean sPAP of 41.9 ± 19.7 mmHg (43–45). Sugino et al.’s echocardiographic sPAP analysis demonstrated greater annual pulmonary arterial pressure progression in CPFE than in IPF. Patients with CPFE and PAH exhibit a worse prognosis than those with CPFE or IPF alone, with a 1-year survival rate of approximately 60%, as reported in previous studies (40, 46).

LC is also a common complication in patients with CPFE, primarily affecting elderly male smokers. The lesions typically occur in the lower lobes of the lungs, often in areas of pulmonary fibrosis. The predominant pathological subtypes are adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (47–52). Upon diagnosis of lung cancer, patients with CPFE often present with advanced-stage disease. Owing to nonspecific clinical symptoms, detection and diagnosis are frequently delayed. More significantly, the tumor may be obscured by underlying pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema, complicating timely detection via chest CT scans and potentially leading to misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis (53, 54). Both emphysema and pulmonary fibrosis independently increase the risk of LC in patients with CPFE. Multiple studies confirm a significantly elevated risk of malignancy compared to either condition alone (38, 40, 55–57). Additionally, smoking, family history of cancer, body mass index (BMI), fibrinogen levels, and serum C3 levels are independently associated with LC development in patients with CPFE (54, 58). Compared with IPF-LC, COPD-LC, or CPFE alone, patients with CPFE-LC exhibit reduced overall survival (30, 48, 59–61). This poor prognosis may be associated with the severity and type of pulmonary fibrosis, the emphysema phenotype, the stage of lung cancer, and the implementation of treatment strategies.

Current evidence indicates that the following factors may serve as predictors of prognosis in CPFE-LC patients: lung function indicators (e.g., carbon monoxide diffusion capacity, forced expiratory volume in the first second and forced vital capacity), disease severity (e.g., the extent of pulmonary fibrosis or emphysema and TNM staging of lung cancer), AE, the composite physiologic index and higher normal lung scores (62–68).

AE critically increase CPFE mortality risk and are potentially associated with COPD or ILD. Lee et al. found that pulmonary infection was the main cause of AE in patients with CPFE. Environmental factors, such as air pollution and smoking, represent established risk factors for AE (69–71). Notably, loxoprofen, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, has been implicated in triggering exacerbations of CPFE (72). Current evidence remains limited, but decreased FVC, DLCO, LC, and elevated GAP scores constitute established predictors of AE (73, 74). In addition, it is unclear whether the incidence of AE-COPD in CPFE patients is consistent with that in patients with single-disease COPD.

Treatment

Currently, there is no effective treatment for CPFE. Evidence supports the benefits of smoking cessation, oxygen therapy, pulmonary rehabilitation, and vaccination in the management of CPFE (41). Although the efficacy of pulmonary rehabilitation has not been definitively established in CPFE, it is nevertheless recommended for most patients due to its potential to improve exertional dyspnea and quality of life. Simone et al. demonstrated that moderate-intensity aerobic exercise combined with breathing training for 4 weeks significantly improved physical fitness, quality of life, and mood in rehabilitation patients. However, pulmonary function showed no significant improvement following this intervention (75, 76). Currently, high-quality studies evaluating the efficacy of pulmonary rehabilitation in CPFE remain limited. In the future, more research should focus on developing individualized exercise rehabilitation regimens for patients with CPFE. Oxygen therapy should be initiated in patients with hypoxemia at rest or during exertion. Long-term oxygen therapy may prevent complications of chronic hypoxemia (77). Infection is a significant contributing factor to the progression of both COPD and pulmonary fibrosis. Clinical guidelines accordingly advise vaccination in affected individuals. For patients with CPFE, appropriate vaccinations (such as influenza, novel coronavirus, and pneumococcal vaccines) are recommended to prevent infection, decrease the frequency of AE, and slow disease progression (78).

Currently, no targeted pharmacological therapies are available for CPFE. However, due to the inherent heterogeneity of interstitial lung diseases and the frequent coexistence of emphysema, separate management of pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema is warranted. Treatment selection for CPFE depends on whether the disease is predominantly inflammatory or fibrotic, guiding the use of anti-inflammatory or antifibrotic agents. For patients with CPFE who have progressive fibrosis, antifibrotic agents such as Nintedanib or pirfenidone may be considered. However, the therapeutic efficacy of antifibrotic agents in CPFE remains inconsistent. One study employed ultrasound imaging of lung fissures to assess pirfenidone, demonstrating limited therapeutic benefit in CPFE (79–81). By contrast, a phase III clinical trial investigated the efficacy of Nintedanib in progressive pulmonary fibrosis and showed that this agent can slow disease progression. A separate study compared antifibrotic agents (including Nintedanib and pirfenidone) in patients with IPF and CPFE. This investigation found that long-term use (≥12 months) of these agents was associated with improved survival in both groups.

Evidence supports the use of bronchodilators in CPFE patients with reversible airflow obstruction. However, their efficacy in those without airflow limitation remains poorly established. Dong et al. demonstrated that ICS/LABA therapy improved pulmonary function and reduced both the frequency and severity of acute exacerbations in patients with CPFE (82). However, these findings do not establish a therapeutic benefit of bronchodilators in CPFE, as the study was constrained by a small sample size (45 patients receiving bronchodilators vs. 24 patients not receiving bronchodilator therapy), non-randomized design with potential selection bias, and a lack of adjustment for disease severity. Lung transplantation remains the only life-extending treatment for patients with CPFE and represents the preferred intervention for those with end-stage disease. In a large-scale study, Takahashi et al. reported a 5-year post-transplant survival rate of 79% in CPFE patients (14, 44, 83).

In summary, CPFE arises from synergistic interactions between the pathological processes of pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. Clinical management remains challenging and is guided by the relative extent, subtypes, and severity of these two components. Inhaled bronchodilator therapy should be considered for patients with CPFE and significant airflow obstruction. Antifibrotic therapy may be an option for CPFE patients with progressive pulmonary fibrosis. Inhaled bronchodilator therapy should be considered for patients with CPFE and significant airflow obstruction. For those with progressive pulmonary fibrosis, antifibrotic therapy may represent an option. However, the need for and modality of treatment in patients without significant airflow limitation or progressive fibrosis remain unclear and require further investigation. Prospective, large-scale clinical trials are necessary to evaluate the efficacy of antifibrotic agents and bronchodilators in specific CPFE subtypes. Lung transplantation is the only intervention proven to prolong survival in end-stage CPFE.

Conclusion

CPFE is a clinical imaging syndrome. It is characterized by the interaction (not simply superimposition) of pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. Owing to the interference and mutual masking of the imaging characteristics of pulmonary emphysema and early pulmonary fibrosis on HRCT, early identification is limited. Therefore, future research should employ AI-driven quantitative imaging analysis integrated with multimodal biomarkers and clinical data to achieve early detection, precise phenotyping, and personalized treatment. Currently, no targeted therapies are available for CPFE; management focuses on supportive measures such as smoking cessation, vaccination, oxygen therapy, and treatment of comorbidities. Advancing targeted phase II/III clinical trials and establishing integrated imaging-biomarker-clinical phenotype prognostic models are imperative to optimize individualized treatment strategies and improve quality of life.

Statements

Author contributions

WZ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Project administration, Investigation, Methodology, Data curation, Software, Formal analysis. BL: Validation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. XO: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Supervision, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31671189) and the Sichuan Province Science and Technology Support Program (Grant No. 2018SZ0109).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Wiggins J Strickland B Turner-Warwick M . Combined cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis and emphysema: the value of high resolution computed tomography in assessment. Respir Med. (1990) 84:365–9. doi: 10.1016/S0954-6111(08)80070-4

2.

Cottin V Nunes H Brillet PY Delaval P Devouassoux G Tillie-Leblond I et al . Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: a distinct underrecognised entity. Eur Respir J. (2005) 26:586–93. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00021005

3.

Gredic M Karnati S Ruppert C Guenther A Avdeev SN Kosanovic D . Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: when Scylla and Charybdis ally. Cells. (2023) 12:1278. doi: 10.3390/cells12091278

4.

Calaras D Mathioudakis AG Lazar Z Corlateanu A . Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: comparative evidence on a complex condition. Biomedicine. (2023) 11:1636. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11061636

5.

Nemoto M Koo CW Scanlon PD Ryu JH . Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. Mayo Clin Proc. (2023) 98:1685–96. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2023.05.002

6.

Portillo K Morera J . Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema syndrome: a new phenotype within the Spectrum of smoking-related interstitial lung disease. Pulm Med. (2012) 2012:867870. doi: 10.1155/2012/867870

7.

Kumar A Cherian SV Vassallo R Yi ES Ryu JH . Current concepts in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and Management of Smoking-Related Interstitial Lung Diseases. Chest. (2018) 154:394–408. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.11.023

8.

Bellou V Belbasis L Evangelou E . Tobacco smoking and risk for pulmonary fibrosis: a prospective cohort study from the UK biobank. Chest. (2021) 160:983–93. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.04.035

9.

Chae KJ Jin GY Jung HN Kwon KS Choi H Lee YC et al . Differentiating smoking-related interstitial fibrosis (SRIF) from usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) with emphysema using CT features based on pathologically proven cases. PLoS One. (2016) 11:e0162231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162231

10.

Antoniou KM Walsh SL Hansell DM Rubens MR Marten K Tennant R et al . Smoking-related emphysema is associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and rheumatoid lung. Respirology. (2013) 18:1191–6. doi: 10.1111/resp.12154

11.

Ye Q Huang K Ding Y Lou B Hou Z Dai H et al . Cigarette smoking contributes to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis associated with emphysema. Chin Med J. (2014) 127:469–74. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.20131684

12.

Jacob J Bartholmai BJ Rajagopalan S Kokosi M Maher TM Nair A et al . Functional and prognostic effects when emphysema complicates idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. (2017) 50:1700379. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00379-2017

13.

Escalon JG Girvin F . Smoking-related interstitial lung disease and emphysema. Clin Chest Med. (2024) 45:461–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2023.08.016

14.

Lin H Jiang S . Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE): an entity different from emphysema or pulmonary fibrosis alone. J Thorac Dis. (2015) 7:767–79. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.04.17

15.

Asif H Braman SS . Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema in a patient with chronic occupational exposure to trichloroethylene. Mil Med. (2024) 189:e907–10. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usad359

16.

Antoniou KM Margaritopoulos GA Goh NS Karagiannis K Desai SR Nicholson AG et al . Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema in scleroderma-related lung disease has a major confounding effect on lung physiology and screening for pulmonary hypertension. Arthritis Rheum. (2016) 68:1004–12. doi: 10.1002/art.39528

17.

Jacob J Song JW Yoon HY Cross G Barnett J Woo WL et al . Prevalence and effects of emphysema in never-smokers with rheumatoid arthritis interstitial lung disease. EBioMedicine. (2018) 28:303–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.01.038

18.

Ariani A Silva M Bravi E Parisi S Saracco M De Gennaro F et al . Overall mortality in combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema related to systemic sclerosis. RMD Open. (2019) 5:e000820. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000820

19.

Tzouvelekis A Zacharis G Oikonomou A Mikroulis D Margaritopoulos G Koutsopoulos A et al . Increased incidence of autoimmune markers in patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. BMC Pulm Med. (2013) 13:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-13-31

20.

Mori S Ueki Y Hasegawa M Nakamura K Nakashima K Hidaka T et al . Impact of combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema on lung cancer risk and mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. (2024) 19:e0298573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0298573

21.

Cottin V Nasser M Traclet J Chalabreysse L Lèbre AS Si-Mohamed S et al . Prolidase deficiency: a new genetic cause of combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema syndrome in the adult. Eur Respir J. (2020) 55:1901952. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01952-2019

22.

Nunes H Monnet I Kannengiesser C Uzunhan Y Valeyre D Kambouchner M et al . Is telomeropathy the explanation for combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema syndrome?: report of a family with TERT mutation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2014) 189:753–4. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1724LE

23.

Cottin V Reix P Khouatra C Thivolet-Béjui F Feldmann D Cordier JF . Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema syndrome associated with familial SFTPC mutation. Thorax. (2011) 66:918–9. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.151407

24.

Epaud R Delestrain C Louha M Simon S Fanen P Tazi A . Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema syndrome associated with ABCA3 mutations. Eur Respir J. (2014) 43:638–41. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00145213

25.

Molina-Molina M Borie R . Clinical implications of telomere dysfunction in lung fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. (2018) 24:440–4. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000506

26.

Hoffman TW van Moorsel CHM Borie R Crestani B . Pulmonary phenotypes associated with genetic variation in telomere-related genes. Curr Opin Pulm Med. (2018) 24:269–80. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000475

27.

Roake CM Artandi SE . Control of cellular aging, tissue function, and Cancer by p53 downstream of telomeres. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. (2017) 7:a026088. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a026088

28.

Duckworth A Gibbons MA Allen RJ Almond H Beaumont RN Wood AR et al . Telomere length and risk of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet Respir Med. (2021) 9:285–94. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30364-7

29.

Alder JK Guo N Kembou F Parry EM Anderson CJ Gorgy AI et al . Telomere length is a determinant of emphysema susceptibility. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2011) 184:904–12. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0520OC

30.

Hage R Gautschi F Steinack C Schuurmans MM . Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE) clinical features and management. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. (2021) 16:167–77. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S286360

31.

Tokuda Y Miyagi S . Physical diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Intern Med. (2007) 46:1885–91. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.0455

32.

Cottin V Cordier JF . Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema in connective tissue disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med. (2012) 18:418–27. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e328356803b

33.

Jankowich MD Rounds SIS . Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema syndrome: a review. Chest. (2012) 141:222–31. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-1062

34.

Papaioannou AI Kostikas K Manali ED Papadaki G Roussou A Kolilekas L et al . Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: the many aspects of a cohabitation contract. Respir Med. (2016) 117:14–26. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.05.005

35.

Alsumrain M De Giacomi F Nasim F Koo CW Bartholmai BJ Levin DL et al . Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema as a clinicoradiologic entity: characterization of presenting lung fibrosis and implications for survival. Respir Med. (2019) 146:106–12. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2018.12.003

36.

Ryerson CJ Hartman T Elicker BM Ley B Lee JS Abbritti M et al . Clinical features and outcomes in combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. (2013) 144:234–40. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2403

37.

Yoon H Kim TH Seo JB Lee SM Lim S Lee HN et al . Effects of emphysema on physiological and prognostic characteristics of lung function in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology. (2019) 24:55–62. doi: 10.1111/resp.13387

38.

Kwak N Park CM Lee J Park YS Lee SM Yim JJ et al . Lung cancer risk among patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. Respir Med. (2014) 108:524–30. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.11.013

39.

Swigris JJ . Towards a refined definition of combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. Respirology. (2019) 24:9–10. doi: 10.1111/resp.13426

40.

Sugino K Ishida F Kikuchi N Hirota N Sano G Sato K et al . Comparison of clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema versus idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis alone. Respirology. (2014) 19:239–45. doi: 10.1111/resp.12207

41.

Cottin V Selman M Inoue Y Wong AW Corte TJ Flaherty KR et al . Syndrome of combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT research statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2022) 206:e7–e41. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202206-1041ST

42.

Choi SH Lee HY Lee KS Chung MP Kwon OJ Han J et al . The value of CT for disease detection and prognosis determination in combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE)Zulueta JJ, editor.PLoS One. (2014) 9:e107476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107476

43.

Cottin V . Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: bad and ugly all the same?Eur Respir J. (2017) 50:1700846. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00846-2017

44.

Caminati A Cassandro R Harari S . Pulmonary hypertension in chronic interstitial lung diseases. Eur Respir Rev. (2013) 22:292–301. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00002713

45.

Malli F . Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema characteristics in a Greek cohort. ERJ Open Res. (2018) 5:2018. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00014-2018

46.

Cottin V Le Pavec J Prévot G Mal H Humbert M Simonneau G et al . Pulmonary hypertension in patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema syndrome. Eur Respir J. (2010) 35:105–11. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00038709

47.

Fujiwara A Tsushima K Sugiyama S Yamaguchi K Soeda S Togashi Y et al . Histological types and localizations of lung cancers in patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. Thorac Cancer. (2013) 4:354–60. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12023

48.

Li C Wu W Chen N Song H Lu T Yang Z et al . Clinical characteristics and outcomes of lung cancer patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 studies. J Thorac Dis. (2017) 9:5322–34. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.12.72

49.

Koo HJ Do KH Lee JB Alblushi S Lee SM . Lung cancer in combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. (2016) 11:e0161437. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161437

50.

Zhang M Yoshizawa A Kawakami S Asaka S Yamamoto H Yasuo M et al . The histological characteristics and clinical outcomes of lung cancer in patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. Cancer Med. (2016) 5:2721–30. doi: 10.1002/cam4.858

51.

Gao L Xie S Liu H Liu P Xiong Y Da J et al . Lung cancer in patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema revisited with the 2015 World Health Organization classification of lung tumors. Clin Respir J. (2018) 12:652–8. doi: 10.1111/crj.12575

52.

Wei Y Yang L Wang Q . Analysis of clinical characteristics and prognosis of lung cancer patients with CPFE or COPD: a retrospective study. BMC Pulm Med. (2024) 24:274. doi: 10.1186/s12890-024-03088-5

53.

Nemoto M Koo CW Ryu JH . Diagnosis and treatment of combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema in 2022. JAMA. (2022) 328:69–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.8492

54.

Feng X Duan Y Lv X Li Q Liang B Ou X . The impact of lung Cancer in patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE). JCM. (2023) 12:1100. doi: 10.3390/jcm12031100

55.

Nasim F Moua T . Lung cancer in combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: a large retrospective cohort analysis. ERJ Open Res. (2020) 6:00521–2020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00521-2020

56.

Wilson DO Weissfeld JL Balkan A Schragin JG Fuhrman CR Fisher SN et al . Association of radiographic emphysema and airflow obstruction with lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2008) 178:738–44. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200803-435OC

57.

Chen Q Liu P Zhou H Kong H Xie W . An increased risk of lung cancer in combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema patients with usual interstitial pneumonia compared with patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis alone: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Adv Respir Dis. (2021) 15:17534666211017050. doi: 10.1177/17534666211017050

58.

Kawaguchi T Koh Y Ando M Ito N Takeo S Adachi H et al . Prospective analysis of oncogenic driver mutations and environmental factors: Japan molecular epidemiology for lung Cancer study. J Clin Oncol. (2016) 34:2247–57. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.2322

59.

Lee CH Kim HJ Park CM Lim KY Lee JY Kim DJ et al . The impact of combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema on mortality. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. (2011) 15:1111–6. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0491

60.

Kumagai S Marumo S Yamanashi K Tokuno J Ueda Y Shoji T et al . Prognostic significance of combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema in patients with resected non-small-cell lung cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. (2014) 46:e113–9. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu384

61.

Portillo K Perez-Rodas N García-Olivé I Guasch-Arriaga I Centeno C Serra P et al . Lung Cancer in patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. A descriptive study in a Spanish series. Arch Bronconeumol. (2017) 53:304–10. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2016.10.004

62.

Lee G Kim KU Lee JW Suh YJ Jeong YJ . Serial changes and prognostic implications of CT findings in combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: comparison with fibrotic idiopathic interstitial pneumonias alone. Acta Radiol. (2017) 58:550–7. doi: 10.1177/0284185116664227

63.

Ueno F Kitaguchi Y Shiina T Asaka S Miura K Yasuo M et al . The preoperative composite physiologic index may predict mortality in lung Cancer patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. Respiration. (2017) 94:198–206. doi: 10.1159/000477587

64.

Homma S Bando M Azuma A Sakamoto S Sugino K Ishii Y et al . Japanese guideline for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Investig. (2018) 56:268–91. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2018.03.003

65.

Ogura T Takigawa N Tomii K Kishi K Inoue Y Ichihara E et al . Summary of the Japanese respiratory society statement for the treatment of lung cancer with comorbid interstitial pneumonia. Respir Investig. (2019) 57:512–33. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2019.06.001

66.

Miyamoto A Kurosaki A Moriguchi S Takahashi Y Ogawa K Murase K et al . Reduced area of the normal lung on high-resolution computed tomography predicts poor survival in patients with lung cancer and combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. Respir Investig. (2019) 57:140–9. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2018.10.007

67.

Nemoto M Nei Y Bartholmai B Yoshida K Matsui H Nakashita T et al . Automated computed tomography quantification of fibrosis predicts prognosis in combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema in a real-world setting: a single-Centre, retrospective study. Respir Res. (2020) 21:275. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01545-3

68.

Oh JY Lee YS Min KH Hur GY Lee SY Kang KH et al . Impact and prognosis of lung cancer in patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. (2020) 37:e2020020. doi: 10.36141/svdld.v37i4.7316

69.

Ko FW Chan KP Hui DS Goddard JR Shaw JG Reid DW et al . Acute exacerbation of COPD. Respirology. (2016) 21:1152–65. doi: 10.1111/resp.12780

70.

Kim V Aaron SD . What is a COPD exacerbation? Current definitions, pitfalls, challenges and opportunities for improvement. Eur Respir J. (2018) 52:1801261. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01261-2018

71.

Oh JY Lee YS Min KH Hur GY Lee SY Kang KH et al . Presence of lung cancer and high gender, age, and physiology score as predictors of acute exacerbation in combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: a retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore). (2018) 97:e11683. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011683

72.

Ando M Nagase H Satonaga Y Yamatani I Yabe M Kan T et al . Acute exacerbation of combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema due to suspected loxoprofen-induced lung injury. Geriatr Gerontol Int. (2024) 24:1241–3. doi: 10.1111/ggi.14974

73.

Zantah M Dotan Y Dass C Zhao H Marchetti N Criner GJ . Acute exacerbations of COPD versus IPF in patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. Respir Res. (2020) 21:164. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01432-x

74.

Ikuyama Y Ushiki A Kosaka M Akahane J Mukai Y Araki T et al . Prognosis of patients with acute exacerbation of combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: a retrospective single-Centre study. BMC Pulm Med. (2020) 20:144. doi: 10.1186/s12890-020-01185-9

75.

Tomioka H Mamesaya N Yamashita S Kida Y Kaneko M Sakai H . Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: effect of pulmonary rehabilitation in comparison with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMJ Open Respir Res. (2016) 3:e000099. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2015-000099

76.

De Simone G Aquino G Di Gioia C Mazzarella G Bianco A Calcagno G . Efficacy of aerobic physical retraining in a case of combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Rep. (2019) 2019:85. doi: 10.1186/s13256-015-0570-3

77.

Wenger HC Cifu AS Lee CT . Home oxygen therapy for adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or interstitial lung disease. JAMA. (2021) 326:1738–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.12073

78.

Cottin V Bonniaud P Cadranel J Crestani B Jouneau S Marchand-Adam S et al . French practical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis - 2021 update. Full-length version. Respir Med Res. (2023) 83:100948. doi: 10.1016/j.resmer.2022.100948

79.

Flaherty KR Wells AU Cottin V Devaraj A Walsh SLF Inoue Y et al . Nintedanib in progressive Fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. N Engl J Med. (2019) 381:1718–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908681

80.

Charleston-Villalobos S Castaneda-Villa N Gonzalez-Camarena R Mejia-Avila M Mateos-Toledo H Aljama-Corrales T (2016). “Acoustic evaluation of pirfenidone on patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis emphysema syndrome.” In 2016 38th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC) [Internet]. p. 3175–8.

81.

Oltmanns U Kahn N Palmowski K Träger A Wenz H Heussel CP et al . Pirfenidone in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: real-life experience from a German tertiary referral center for interstitial lung diseases. Respiration. (2014) 88:199–207. doi: 10.1159/000363064

82.

Dong F Zhang Y Chi F Song Q Zhang L Wang Y et al . Clinical efficacy and safety of ICS/LABA in patients with combined idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema. Int J Clin Exp Med. (2015) 8:8617–25. PMID:

83.

Takahashi T Terada Y Pasque MK Liu J Byers DE Witt CA et al . Clinical features and outcomes of combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema after lung transplantation. Chest. (2021) 160:1743–50. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.06.036

Summary

Keywords

combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema, diagnosis, prognosis, complications, management

Citation

Zeng W, Liang B and Ou X (2025) Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: a narrative review. Front. Med. 12:1683252. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1683252

Received

10 August 2025

Accepted

11 September 2025

Published

04 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Ilias C. Papanikolaou, General Hospital of Corfu, Greece

Reviewed by

Alexandru Corlateanu, Nicolae Testemiţanu State University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Moldova

Cheng Sheng Yin, Yijishan Hospital of Wannan Medical College, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Zeng, Liang and Ou.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xuemei Ou, ouxuemeihx123@126.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.