Abstract

Background/purpose:

Standardized training for emergency nurses should include effective methods to develop rapid response, teamwork, and stress resistance. Traditional simulation-based training may lack the intensity and unpredictability of real emergencies. This study evaluated a progressive real rescue participation strategy compared to traditional simulation training.

Methods:

A retrospective analysis included 235 emergency standardized training nurses from May 2022 to April 2025. They were divided into a Traditional Training group (n = 126, simulation and theory only) and a Real Rescue Training group (n = 109, simulation/theory plus phased participation in actual resuscitation). Validated scales assessed rapid response (TDMI), team climate (TCI), resilience (CD-RISC), burnout (MBI), and critical thinking (CTDI-CV) before and after the 6-month training. Department exit assessments and nursing satisfaction were also compared.

Results:

Baseline characteristics were comparable. Both groups improved significantly on all post-training scales. However, the Real Rescue group showed significantly greater improvement than the Traditional group in all dimensions of rapid response (TDMI subscales, all p < 0.05), team collaboration (TCI subscales, all p < 0.05), stress resistance (CD-RISC subscales, all p < 0.05), critical thinking (CTDI-CV subscales, all p < 0.05), and reduced burnout (MBI subscales, all p < 0.01). The Real Rescue group also scored higher on theoretical (p = 0.02) and clinical skills exit assessments (p = 0.01) and achieved significantly higher nursing satisfaction (p = 0.01).

Conclusion:

Real-rescue training is more effective than traditional methods in improving emergency nurses’ critical skills and psychological resilience. This approach should be integrated into standardized training programs to better prepare nurses for real-world emergencies.

1 Introduction

Emergency departments are characterized as high-pressure environments due to the critical nature of medical interventions required and the potential for significant consequences on patient outcomes. Patient outcomes critically depend on nurses’ abilities to respond rapidly. Nurses must also collaborate seamlessly within multidisciplinary teams and maintain performance under intense pressure. Standardized training programs for new emergency nurses aim to build these essential competencies (1, 2). Traditionally, these programs have heavily relied on simulation-based training. Simulation-based training offers a safe, controlled environment to practice skills and protocols using manikins and scripted scenarios. It allows for repeated practice, standardized experiences, and immediate feedback without patient risk. These benefits make simulation a cornerstone of modern clinical education (3, 4).

However, despite its advantages, simulation training has inherent limitations in replicating the full complexity and psychological demands of actual emergency resuscitation. The controlled nature of simulations can reduce the psychological stress and cognitive load experienced in real life. Simulations may lack the chaotic elements, true urgency, unpredictable patient responses, simultaneous competing demands, and high-stakes consequences inherent in real resuscitation. Consequently, nurses trained primarily through simulation might experience a significant performance gap when transitioning to real clinical practice. It potentially impacts patient safety and nurse confidence (5, 6).

This gap highlights the necessity for training strategies that effectively connect simulated practice with real-world application. Experiential learning theory emphasizes that deep learning occurs through direct experience and reflection (7). Bandura’s social learning theory further suggests that observing and gradually participating in real performances within a team context is crucial for skill acquisition and confidence building (8). Therefore, carefully structured exposure to actual emergency resuscitation during training holds significant potential. Such exposure could provide the missing elements of genuine stress, authentic team dynamics, and the need for real-time adaptive decision-making under pressure (9).

While the potential benefits of real clinical experience are acknowledged, integrating it systematically into standardized training programs presents challenges. Concerns include patient safety, ethical considerations regarding novice participation, potential for increased stress leading to burnout, and the need for structured progression to ensure learning without overwhelming trainees. A phased approach, moving from observation to assisted participation and finally to defined core tasks under close supervision, could mitigate these risks while maximizing learning (10, 11).

Given the global shortage of emergency nurses, optimizing training strategies is essential for sustaining healthcare systems. This study investigates whether a structured program of progressive participation in real emergency resuscitation, integrated alongside traditional simulation and didactic teaching, is more effective than traditional simulation-based training alone. We specifically evaluated its impact on developing the core competencies of rapid response capability, team collaboration, stress resistance, critical thinking, and overall job readiness among emergency standardized training nurses. This study contributes to the evidence base by comparing real-rescue and traditional training through rigorous, multidimensional assessments.

Rapid response, team collaboration, and stress resistance represent core competencies for emergency nurses. In high-acuity settings such as the emergency department, seconds often determine patient survival; delays in triage or decision-making are associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Equally critical is team collaboration, as resuscitation and trauma care demand seamless role clarity, communication, and coordination breakdowns in teamwork are repeatedly linked to preventable errors and poorer outcomes. Finally, stress resistance is indispensable: emergency nurses are routinely exposed to high-stakes, emotionally charged, and unpredictable events, which, if unmanaged, can precipitate burnout, impaired judgment, and compromised care delivery. Together, these domains underpin not only individual clinical performance but also the collective safety culture of emergency departments.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Inclusion and grouping of objects

A retrospective analysis was conducted on 235 nurses who completed standardized training in the Department of Emergency of our hospital from May 2022 to April 2025. Inclusion criteria were: (a) newly hired nurses undergoing emergency standardized training; (b) possession of a nursing practice qualification certificate; (c) completion of pre-job training; and (d) voluntary participation in the standardized training program.

Exclusion criteria included those who could not fully participate in the training due to study trips, extended leave (≥ 2 weeks), or job transfers during the training period.

Nurses were divided into two groups based on practical differences in historical training records: the traditional training group (n = 126) and the real rescue training group (n = 109). Nurses in the traditional training group were defined as those who only participated in simulation scene-based training and theoretical instruction without real rescue training (no signature on the rescue registration book), while nurses in the real rescue training group were defined as those who, in addition to traditional training, also participated in real rescue scenarios. All nurses completed 6 months of standardized training in the Department of Emergency.

2.2 Training methods

2.2.1 Traditional training method

Before the training, a training team consisting of the head nurse of the emergency department and two clinical instructors from the same department was formed to develop a training outline guided by the core competencies training curriculum system (12). During the training process, a “teach-first, then practice” approach was adopted, where the instructors taught emergency nursing theory and emergency operational skills, with each session lasting 45 to 60 min, held once a week.

Nurses in the traditional training group received a variety of simulation scenarios ranging from simple to moderately complex based on real emergency rescue situations, such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), endotracheal intubation, defibrillation, trauma first aid, and the rescue of critically ill patients. The selected cases were representative, covering all the basic knowledge and skills required for emergency rescue comprehensively. Simulation rescue training was conducted once a week, each session lasting 1 h. Nurses took on roles including doctors, patients, rescue-involved nurses, and family members. After the drills, teaching instructors and resident nurses jointly summarized and reflected on the experience. During the rest of the time, standardized training nurses observed and learned in the actual emergency room, assisted in completing non-critical tasks to help stabilize patients, and became familiar with the department’s workflow and equipment.

Upon completion of the training, standardized training nurses participated in both theoretical and practical examinations (with a maximum score of 100 for each). In addition, patient or family satisfaction surveys were conducted (unified exclusion of critically ill cases), with the overall satisfaction rate calculated as the sum of the satisfied and moderately satisfied rates.

2.2.2 Real rescue training method

Unlike the simulation scenarios of traditional training groups, nurses in the real rescue training group received progressive participation training based on traditional methods. This training was conducted entirely in real emergency resuscitation settings. During the initial phase (months 1–2), standardized training nurses participated as “observers,” focusing on observing the division of labor and collaboration within the resuscitation team, key operational procedures (such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation and airway management), and healthcare communication models (such as SBAR reports). After each resuscitation, they wrote observation notes under the guidance of clinical instructors, summarizing critical response points and teamwork essentials during the resuscitation. In months 3–4, depending on the nurse’s adaptation, their role was adjusted to “assistant participant.” Under the supervision of clinical instructors, they undertook basic resuscitation tasks such as establishing intravenous access, preparing resuscitation medications, and recording vital signs. Instructors provided real-time corrections for any delays or procedural oversights and conducted “one-on-one” feedback sessions within 1 hour after the resuscitation, focusing on response speed (e.g., “Establishing intravenous access took 30 s longer than the standard time; optimize the procedure”) and operational stability under pressure. By months 5–6, nurses with developed capabilities transitioned to the “core participant” role, taking on specific critical tasks within the team (such as assisting with defibrillation, verifying medical orders, and participating in patient condition assessments).

A pilot phase with 10 trainees was conducted to ensure feasibility and refine supervision procedures prior to the main study, though pilot data were not included in the final analysis.

2.3 Multidimensional evaluation

Before and after the training, demographic questionnaires, the Triage Decision-Making Inventory (TDMI), Team Climate Inventory (TCI), Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), and Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory-Chinese Version (CTDI-CV) were distributed. These were completed anonymously, with both the recovery rate and the validity rate being 100%. The primary evaluation indicators were rapid response, team collaboration, and stress resistance. Secondary evaluation indicators included occupational burnout, critical thinking ability, department exit assessment, and nursing satisfaction.

2.3.1 Quick responsiveness ability

The Triage Decision-Making Inventory (TDMI) was used to assess rapid response ability, as it captures cognitive behavior, intuition, and decision-making under time pressure. The TDMI comprises four dimensions: cognitive behavior, experience, intuition, and critical thinking, with a total of 37 items. Each item is rated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (1 point) to “strongly agree” (6 points). The total score is 222, with higher scores indicating quicker responsiveness abilities. Previous studies report excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α ≈ 0.95) and good construct validity in healthcare learners. Chinese nursing studies have further confirmed acceptable reliability and stable factorial validity, supporting its use in this population (13).

2.3.2 Teamwork ability

The Team Climate Inventory (TCI) was used to measure team collaboration, focusing on shared vision, interaction, and participatory safety. The TCI includes five subscales: vision, interaction and information sharing, innovation support, task orientation, and participation safety, comprising a total of 38 items. It uses a 7-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”), with each subscale score calculated as the average of all items in that subscale multiplied by 10 (to convert to a percentage scale). Higher scores indicate a more positive team collaboration atmosphere and stronger collaboration abilities. The Cronbach’s α coefficients for the five subscales range from 0.83 to 0.93 (14).

2.3.3 Ability to withstand pressure

The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) was used to evaluate stress resistance, including toughness, strength, and optimism under adversity. The CD-RISC consists of 25 items covering resilience, sense of strength, and optimism. It employs a 5-point Likert scale (0 = “never” to 4 = “always”), with total scores ranging from 0 to 100; higher scores indicate greater psychological resilience. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of this scale is 0.89 (15).

2.3.4 Occupational burnout

The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) was included to assess occupational burnout, which is closely linked to nurses’ ability to sustain performance in high-stress environments. The MBI includes three dimensions: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment. The scale consists of 22 items, rated on a 7-point Likert scale (0 = “never” to 6 = “every day”). Higher scores in emotional exhaustion (0–54 points) and depersonalization (0–30 points) indicate stronger occupational burnout, while higher scores in personal accomplishment (0–48 points) indicate weaker occupational burnout. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale is 0.86 (16).

2.3.5 Critical thinking ability

The Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory–Chinese Version (CTDI-CV) was used to evaluate critical thinking ability, encompassing truth-seeking, open-mindedness, and systematicity. This scale includes seven dimensions: truth-seeking, open-mindedness, analytical ability, systematicity, confidence in critical thinking, inquisitiveness, and cognitive maturity. Each dimension contains 10 items, rated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (1 point) to “strongly agree” (6 points). Higher scores indicate a stronger disposition toward critical thinking. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale is 0.85 (17).

These instruments were selected because they map directly onto the study’s primary constructs. The TDMI captures decision-making speed and accuracy under triage conditions (rapid response). The TCI reflects perceptions of teamwork and collaboration climate. The CD-RISC evaluates resilience and stress resistance. The MBI provides a countermeasure for stress impact (burnout), while the CTDI-CV assesses critical thinking, which underpins adaptive responses in emergencies.

2.4 Ethical approval

This study strictly conforms to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and has been reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Xijing Hospital. Given that this is a retrospective study with anonymized data, participant-informed consent was waived.

2.5 Data analysis

All statistical analyses in this study were performed using SPSS statistical software (version 29.0; developed by SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD) based on normality assessed by the Shapiro–Wilk test, while categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages [n (%)]. Group differences for continuous variables were analyzed using independent samples t-tests, and chi-square tests were used for categorical variables. A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Demographics

In Table 1, we present a comparison of the demographics and baseline characteristics between the traditional training group (n = 126) and the real rescue training group (n = 109). Our analysis revealed no significant differences in age (p = 0.397), gender distribution (p = 0.594), height (p = 0.203), weight (p = 0.099), educational background (p = 0.932), marital status (p = 0.864), living situation (dormitory) (p = 0.980), work experience before joining (p = 0.827), pre-job theoretical score (p = 0.102), skill operation score (p = 0.201), as well as prior rotation experience in ICU (p = 0.879) and CCU (p = 0.855) between the two groups. All p values were above the significance level of 0.05, indicating that the two groups were comparable in terms of these baseline parameters.

Table 1

| Parameter | Traditional group (n = 126) | Real rescue group (n = 109) | t/χ2 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 24.32 ± 1.46 | 24.17 ± 1.38 | 0.849 | 0.397 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.284 | 0.594 | ||

| Male | 18 (14.3) | 13 (11.9) | ||

| Female | 108 (85.7) | 96 (88.1) | ||

| Height (cm) | 166.28 ± 3.51 | 165.73 ± 2.93 | 1.276 | 0.203 |

| Weight (kg) | 56.26 ± 5.63 | 57.31 ± 4.06 | 1.657 | 0.099 |

| Educational background, n (%) | 0.007 | 0.932 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or above | 100 (79.4) | 87 (79.8) | ||

| Junior college | 26 (20.6) | 22 (20.2) | ||

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.029 | 0.864 | ||

| Married | 13 (10.3) | 12 (11.0) | ||

| Single | 113 (89.7) | 97 (89.0) | ||

| Living situation (dormitory), n (%) | 0.001 | 0.980 | ||

| Yes | 112 (88.9) | 97 (89.0) | ||

| No | 14 (11.1) | 12 (11.0) | ||

| Work experience, n (%) | 0.048 | 0.827 | ||

| Yes | 15 (11.9) | 14 (12.8) | ||

| No | 111 (88.1) | 95 (87.2) | ||

| Pre-job training score (points) | ||||

| Theoretical score | 91.93 ± 2.47 | 92.45 ± 2.34 | 1.644 | 0.102 |

| Skill operation score | 92.36 ± 1.79 | 92.08 ± 1.51 | 1.284 | 0.201 |

| Prior rotation experience, n (%) | ||||

| ICU | 37 (29.4) | 33 (30.3) | 0.023 | 0.879 |

| CCU | 29 (23.0) | 24 (22.0) | 0.033 | 0.855 |

Comparison of baseline characteristics between the traditional training and the real rescue training groups.

3.2 Quick responsiveness ability

When comparing the Triage Decision-Making Inventory (TDMI) scores between the Traditional training group and the Real rescue training group, no significant differences were observed in cognitive behavior, experience sharing, intuition, and critical thinking before training (all p > 0.05) (Table 2). However, after completing their respective training programs, all assessed parameters showed significant improvements within each group (all p < 0.05). For cognitive behavior, the Real rescue training group showed a significant increase compared to the Traditional training group (p = 0.009). Similarly, in experience sharing, the Real rescue training group exhibited higher scores than the Traditional training group (p = 0.01). Regarding intuition, the Real rescue training group scored significantly higher than the Traditional training group (p = 0.009). For critical thinking, the Real rescue training group also demonstrated significantly higher scores compared to the Traditional training group (p = 0.001). In summary, while both training methods led to significant improvements in participants’ triage decision-making skills, the Real rescue training group outperformed the Traditional training group in every measured aspect post-training. This suggests that the Real rescue training approach may be more effective in enhancing specific skills related to quick responsiveness ability in triage settings.

Table 2

| Parameter | Timepoint | Traditional group (n = 126) | Real rescue group (n = 109) | t | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive behavior | Before training | 21.52 ± 2.13 | 21.38 ± 2.07 | 0.533 | 0.595 |

| After training | 35.76 ± 3.25ᵃ | 36.84 ± 2.97ᵃ | 2.623 | 0.009 | |

| Experience sharing | Before training | 19.87 ± 1.92 | 19.95 ± 1.88 | 0.324 | 0.746 |

| After training | 32.85 ± 2.78ᵃ | 33.72 ± 2.51ᵃ | 2.507 | 0.013 | |

| Intuition | Before training | 22.63 ± 2.34 | 22.95 ± 3.38 | 0.813 | 0.417 |

| After training | 38.65 ± 3.42ᵃ | 39.72 ± 2.85ᵃ | 2.619 | 0.009 | |

| Critical thinking | Before training | 22.62 ± 2.05 | 22.14 ± 2.11 | 1.754 | 0.081 |

| After training | 41.48 ± 3.16ᵃ | 42.81 ± 2.94ᵃ | 3.314 | 0.001 |

Comparison of TDMI scores between traditional and real rescue training groups (points, mean ± SD).

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. p-values were obtained using independent-samples t-test.

TDMI, Triage Decision-Making Inventory.

ᵃ p < 0.05 compared with the same group before training.

3.3 Teamwork ability

In comparing the Team Climate Inventory (TCI) scores between the Traditional training group and the Real rescue training group, no significant differences were observed in any parameters before training, including vision, interaction, and information sharing, support for innovation, task orientation, and participation safety (all p > 0.05) (Table 3). After completing their respective training programs, all assessed parameters showed significant improvements within each group compared to their pre-training scores (all p < 0.05). Post-training comparisons revealed that the Real rescue training group consistently scored higher than the Traditional training group across all evaluated parameters. Specifically, the Real rescue training group demonstrated better performance in vision (p = 0.02). Similarly, the Real rescue training group outperformed the Traditional training group in interaction and information sharing (p = 0.006). The Real rescue training group also exhibited higher scores in support for innovation (p = 0.01). Furthermore, in task orientation, the Real rescue training group achieved higher scores (p = 0.007). Lastly, the Real rescue training group showed superior results in participation safety (p = 0.006). These findings suggest that while both training methods significantly enhanced participants’ teamwork abilities, the Real rescue training approach may be more effective in fostering a positive team climate and enhancing specific teamwork skills.

Table 3

| Parameter | Timepoint | Traditional group (n = 126) | Real rescue group (n = 109) | t | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vision | Before training | 32.15 ± 4.27 | 32.08 ± 4.31 | 0.117 | 0.907 |

| After training | 38.82 ± 3.95ᵃ | 39.87 ± 3.12ᵃ | 2.294 | 0.023 | |

| Interaction & information sharing | Before training | 34.62 ± 3.85 | 34.73 ± 3.91 | 0.211 | 0.833 |

| After training | 42.05 ± 3.62ᵃ | 43.25 ± 2.98ᵃ | 2.787 | 0.006 | |

| Support for innovation | Before training | 29.87 ± 3.42 | 29.95 ± 3.38 | 0.186 | 0.853 |

| After training | 37.74 ± 3.28ᵃ | 38.72 ± 2.85ᵃ | 2.442 | 0.015 | |

| Task orientation | Before training | 36.41 ± 4.13 | 36.35 ± 4.05 | 0.119 | 0.906 |

| After training | 43.93 ± 3.75ᵃ | 45.12 ± 2.93ᵃ | 2.741 | 0.007 | |

| Participation safety | Before training | 31.28 ± 3.67 | 31.33 ± 3.72 | 0.110 | 0.912 |

| After training | 40.15 ± 3.41ᵃ | 41.33 ± 3.05ᵃ | 2.788 | 0.006 |

Comparison of TCI scores between traditional and real rescue training groups (points, mean ± SD).

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. p-values were obtained using an independent-samples t-test.

TCI, Team Climate Inventory.

ᵃ p < 0.05 compared with the same group before training.

3.4 Ability to withstand pressure

In the comparison of Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) scores between the Traditional training group and the Real rescue training group, no significant differences were observed in any parameters before training: toughness (p = 0.571), strength (p = 0.348), and optimism (p = 0.879) (Figure 1). After completing their respective training programs, all assessed parameters showed significant improvements within each group compared to their pre-training scores (all p < 0.05). Post-training comparisons revealed that the Real rescue training group consistently scored higher than the Traditional training group across all evaluated parameters. Specifically, for toughness, the Real rescue training group demonstrated better resilience with a lower p value indicating statistical significance (p = 0.01). Similarly, in strength, the Real rescue training group outperformed the Traditional training group (p = 0.01), showing greater improvement in this aspect. Furthermore, for optimism, the Real rescue training group also achieved higher scores compared to the Traditional training group (p = 0.003), reflecting more positive outlooks and attitudes. These findings suggest that while both training methods significantly enhanced participants’ resilience as measured by the CD-RISC, the Real rescue training group exhibited superior outcomes in all assessed dimensions of resilience post-training.

Figure 1

Comparison of the CD-RISC score between the two groups before and after training. (A) Toughness; (B) Strength; (C) Optimism; CD-RISC, Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale. Ns, No significant difference; *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01; a: p < 0.05, compared to the same group before training.

3.5 Occupational burnout

In assessing the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) scores between the Traditional training group and the Real rescue training group, initial comparisons indicated no significant differences in any parameters before training: emotional exhaustion (EE) (p = 0.903), depersonalization (DP) (p = 0.881), and personal accomplishment (PA) (p = 0.940) (Table 4). Following the completion of their respective training programs, all parameters demonstrated notable improvements within each group relative to pre-training levels (all p < 0.05). Post-training evaluations revealed that the Real rescue training group exhibited more favorable outcomes compared to the Traditional training group across all measured aspects. Specifically, regarding emotional exhaustion, the Real rescue training group showed a greater reduction (p = 0.008), indicating lower levels of burnout. Similarly, for depersonalization, participants in the Real rescue training group reported significantly lower scores (p = 0.001), reflecting diminished feelings of detachment or cynicism. In addition, in terms of personal accomplishment, the Real rescue training group achieved higher scores (p = 0.008), suggesting enhanced perceptions of efficacy and achievement. These results indicate that while both training methods contributed to reducing burnout and enhancing personal accomplishment, the Real Rescue training approach was particularly effective in achieving these outcomes (Table 5).

Table 4

| Parameter | Timepoint | Traditional group (n = 126) | Real rescue group (n = 109) | t | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional exhaustion (EE) | Before training | 28.73 ± 5.42 | 28.65 ± 5.37 | 0.122 | 0.903 |

| After training | 24.25 ± 5.83ᵃ | 22.41 ± 4.72ᵃ | 2.665 | 0.008 | |

| Depersonalization (DP) | Before training | 12.85 ± 3.16 | 12.78 ± 3.21 | 0.150 | 0.881 |

| After training | 11.21 ± 3.45ᵃ | 9.85 ± 2.93ᵃ | 3.216 | 0.001 | |

| Personal accomplishment (PA) | Before training | 32.13 ± 4.25 | 32.17 ± 4.32 | 0.075 | 0.940 |

| After training | 38.25 ± 4.52ᵃ | 39.72 ± 3.85ᵃ | 2.658 | 0.008 |

Comparison of MBI scores between traditional and real rescue training groups (points, mean ± SD).

ᵃ p < 0.05 compared with the same group before training.

Table 5

| Parameter | Timepoint | Traditional group (n = 126) | Real rescue group (n = 109) | t | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Truth seeking | Before training | 36.93 ± 3.07 | 37.13 ± 3.22 | 0.478 | 0.633 |

| After training | 38.17 ± 3.53ᵃ | 39.19 ± 3.82ᵃ | 2.141 | 0.033 | |

| Open-mindedness | Before training | 36.21 ± 3.04 | 36.63 ± 3.32 | 1.015 | 0.311 |

| After training | 38.23 ± 3.32ᵃ | 39.31 ± 3.25ᵃ | 2.522 | 0.012 | |

| Analyticity | Before training | 35.93 ± 2.72 | 36.44 ± 2.83 | 1.403 | 0.162 |

| After training | 38.02 ± 3.13ᵃ | 39.05 ± 3.72ᵃ | 2.290 | 0.023 | |

| Systematicity | Before training | 37.97 ± 3.07 | 38.31 ± 3.06 | 0.851 | 0.396 |

| After training | 38.96 ± 3.16ᵃ | 40.02 ± 3.09ᵃ | 2.589 | 0.010 | |

| Critical thinking self-confidence | Before training | 35.97 ± 3.05 | 36.13 ± 3.26 | 0.404 | 0.687 |

| After training | 39.17 ± 3.29ᵃ | 40.18 ± 3.42ᵃ | 2.308 | 0.022 | |

| Inquisitiveness | Before training | 36.93 ± 3.27 | 37.22 ± 3.42 | 0.653 | 0.514 |

| After training | 39.33 ± 2.96ᵃ | 40.25 ± 3.17ᵃ | 2.298 | 0.022 | |

| Cognitive maturity | Before training | 38.06 ± 2.38 | 38.55 ± 3.52 | 1.228 | 0.221 |

| After training | 40.07 ± 3.24ᵃ | 41.25 ± 3.23ᵃ | 2.795 | 0.006 |

Comparison of CTDI-CV score between two groups (points, M ± SD).

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. p-values were obtained using an independent-samples t-test.

CTDI-CV, Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory–Chinese Version.

ᵃ p < 0.05 compared with the same group before training.

3.6 Critical thinking ability

In the comparison of Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory-Chinese Version (CTDI-CV) scores between the Traditional training group and the Real rescue training group, no significant differences were observed in any parameters before training, including truth seeking, open-mindedness, analyticity, systematicity, critical thinking self-confidence, inquisitiveness, and cognitive maturity (all p > 0.05). After completing their respective training programs, all assessed parameters showed significant improvements within each group compared to their pre-training scores (all p < 0.05). Post-training comparisons revealed that the Real rescue training group consistently scored higher than the Traditional training group across all evaluated parameters. Specifically, for truth seeking, the Real rescue training group demonstrated better performance (p = 0.03). Similarly, in open-mindedness, the Real rescue training group outperformed the Traditional training group (p = 0.01). The Real rescue training group also exhibited higher scores in analyticity (p = 0.02). For systematicity, the Real rescue training group achieved higher scores (p = 0.010). In terms of critical thinking self-confidence, the Real rescue training group showed superior results (p = 0.02). In addition, for inquisitiveness, the Real rescue training group also performed better (p = 0.02). Lastly, the Real rescue training group showed higher scores in cognitive maturity (p = 0.006). These findings suggest that while both training methods significantly improved participants’ critical thinking dispositions, the Real rescue training approach was more effective in fostering these skills.

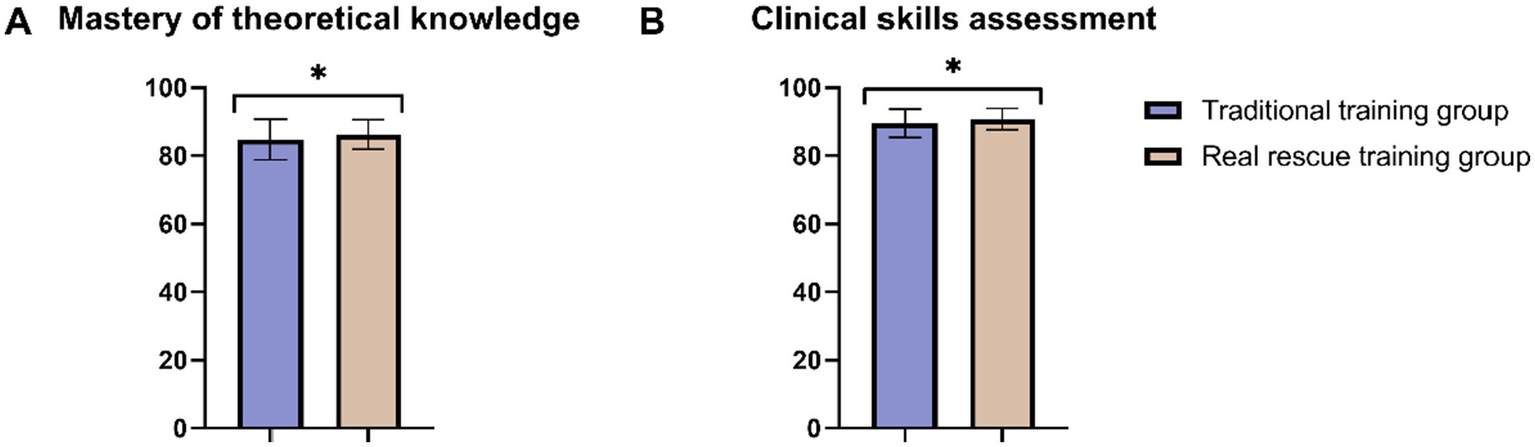

3.7 Department exit assessment

In the comparison of department exit assessment scores between the Traditional training group and the Real rescue training group, significant differences were observed in both evaluated parameters post-training (Figure 2). The Real rescue training group demonstrated higher mastery of theoretical knowledge compared to the Traditional training group (p = 0.02), indicating a stronger grasp of essential concepts. In addition, in the clinical skills assessment, the Real rescue training group also outperformed the Traditional training group (p = 0.01), showcasing superior practical abilities. These results highlight that while both training methods are effective, the Real rescue training approach appears to be more efficacious in enhancing both theoretical knowledge and practical skills.

Figure 2

Comparison of department exit assessment between two groups. (A) Mastery of theoretical knowledge; (B) Clinical skills assessment. *: p < 0.05.

3.8 Nursing satisfaction

In evaluating the nursing satisfaction between the Traditional training group and the Real rescue training group, significant differences were observed in the overall satisfaction rates (Table 6). The Real rescue training group reported a higher overall satisfaction rate compared to the Traditional training group (p = 0.01). Specifically, while the proportion of nurses who were satisfied was slightly higher in the Real rescue training group, the most notable difference was in the dissatisfied category, where only 0.92% of nurses in the Real rescue training group expressed dissatisfaction compared to 7.94% in the Traditional training group. The proportion of nurses reporting moderate satisfaction was similar between the two groups. These findings indicate that the Real rescue training approach not only achieves a higher overall satisfaction rate but also significantly reduces the proportion of dissatisfied nurses.

Table 6

| Parameter | Traditional training group (n = 126) | Real rescue training group (n = 109) | χ 2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall satisfaction rate | 116 (92.06%) | 108 (99.08%) | 6.453 | 0.011 |

| Satisfied | 86 (68.25%) | 81 (74.31%) | ||

| Moderately satisfied | 30 (23.81%) | 27 (24.77%) | ||

| Dissatisfied | 10 (7.94%) | 1 (0.92%) |

Comparison of nursing satisfaction between two groups [n (%)].

4 Discussion

This study investigated whether a structured program of progressive participation in real emergency resuscitations embedded alongside standard simulation and classroom teaching improves core competencies in newly hired nurses compared with traditional simulation-only training. Across validated instruments, the real rescue group showed greater post-training gains in rapid decision-making (TDMI), team climate (TCI), resilience (CD-RISC), burnout (MBI), and critical-thinking dispositions (CTDI-CV), as well as superior performance on department exit assessments and higher training satisfaction.

Real rescue participation yielded broader and larger improvements than traditional training alone. The pattern of effects suggests complementary mechanisms. First, experiential learning in authentic, time-pressured contexts likely accelerated schema formation and application, consistent with the theory that knowledge is consolidated through concrete experience and reflective observation (18, 19). Second, the social learning inherent in real teams observing experts, rehearsing roles, and receiving immediate interprofessional feedback appears to strengthen communication, role clarity, and psychological safety, aligning with your TCI improvements (20, 21). Third, stress inoculation via graded exposure → observer → assistant → supervised participant likely enhanced coping and self-efficacy, explaining the resilience gains and burnout reductions (22–24).

Beyond these established mechanisms, two additional factors may help explain the breadth of benefits observed. First, elements of cognitive-load optimization, briefing, role priming, and focused task assignment may have reduced extraneous load and preserved working memory for clinical reasoning, which is consistent with the stronger gains in TDMI and CTDI-CV. Second, the “consequential validity” of real cases (i.e., decisions with real patient impact) can heighten attentional engagement and memory encoding, plausibly contributing to the meaningful improvements you observed across instruments.

The results are directionally consistent with work showing that high-fidelity and scenario-based learning improves clinical decision-making, teamwork, and adaptability under pressure, while authentic exposure can potentiate stress resilience (22–28). The present study extends that evidence by demonstrating advantages of supervised real-case participation over simulation alone across multiple validated domains concurrently, including critical-thinking dispositions (29, 30) and practical exit assessments (31). This concurrent, cross-construct improvement strengthens the case that authentic clinical participation adds value beyond simulation-based mastery of protocols.

Findings support embedding a phased “observe-assist-perform under supervision” pathway into orientation for emergency nurses. Programs should formalize instructor-to-trainee ratios, pre-brief/debrief structures, and real-time coaching checklists to safeguard patient safety and learner well-being. Where real-case opportunities are limited, hybrid models (simulation priming followed by targeted real-case participation) may achieve similar competency gains while maintaining safety and feasibility. Given the reductions in depersonalization and emotional exhaustion, linking real rescue curricula with wellness resources (peer debriefs, resilience micro-skills) may further buffer burnout. Hospitals planning scale-up should consider implementation supports (scheduling, case selection criteria, competency sign-offs, and documentation standards) to ensure fidelity.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

Strengths include the use of multiple validated instruments spanning decision-making, teamwork, resilience/burnout, and critical thinking; a graded participation design aligned with experiential and stress-inoculation principles; and convergent improvements in both psychometric scores and exit-assessment performance. Important limitations remain. This was a single-center, non-randomized study with assessments immediately post-training, limiting causal inference and durability claims. Instruments were self-report (albeit validated), which may not fully capture real-time performance. Unmeasured confounding (e.g., informal mentorship, prior informal exposure) could contribute to effects. Potential Hawthorne and expectancy effects heightened motivation in the real rescue cohort, cannot be excluded. Finally, resource and ethical safeguards (supervision capacity, patient consent processes, escalation thresholds) may affect generalizability across settings.

4.2 Future directions

Multi-center randomized or stepped-wedge trials are needed to test causal effects and estimate the durability of gains at 3–12 months. Objective performance endpoints (time-to-intervention, protocol adherence, error rates in simulated code events, team communication metrics) should complement self-report. Dose–response evaluations (number/intensity of real cases) can guide efficient program design. Implementation studies should examine feasibility, staffing, and cost-effectiveness, and equity/ethics frameworks (psychological safety, patient consent) should be prospectively embedded. Comparative trials of hybrid models (simulation→targeted real cases) versus simulation-only can clarify the incremental value of authentic exposure while maintaining safety.

As for application, the emergency department’s rescue training approach may be effectively scaled to other acute-care settings, including intensive care units, coronary care units, and trauma services, where swift response, collaboration, and resilience are paramount. To guarantee safe and successful implementation, training must adhere to a systematic progression, initiating with observation, progressing to assistance roles, and concluding with supervised active involvement. Supportive supervision and planned debriefings are equally crucial, as they alleviate psychological strain and enhance reflective learning. Institutional adaptation may necessitate customization based on available resources, patient demographics, and staff-to-patient ratios; nonetheless, the fundamental premise of integrating genuine, supervised clinical experience into standardized training might enhance nurse readiness in many high-stakes settings.

5 Conclusion

This study demonstrates that a structured program of progressive participation in real emergency resuscitations, integrated with traditional simulation and didactic teaching, is highly effective for emergency nurse standardized training. Compared to traditional simulation-based training alone, this approach improves rapid response capability, team collaboration, stress resistance, and critical thinking more significantly. It also results in lower occupational burnout, higher assessment scores, and substantially greater job satisfaction among trainees. The phased model, progressing from Observer to Assistant Participant to Core Participant with close supervision and dedicated debriefing, is essential for maximizing learning while managing risks. The compelling advantages advocate for the integration of meticulously designed real rescue experiences as a fundamental element of emergency nursing education, enhancing nurses’ preparedness for the realities of clinical practice. Future multi-center randomized trials with long-term outcome assessment and incorporation of objective performance measures would further strengthen the evidence base.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

This study strictly conforms to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and has been reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Xijing Hospital. Given that this is a retrospective study with anonymized data, participant informed consent was waived. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

TF: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Investigation, Software. LH: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Data curation. YY: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. CD: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Software. JL: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Xijing Hospital Nursing Discipline Boosting Program (No. XJHL22D101), and the Xijing Hospital Technical Skills Enhancement Project for Nursing Staff (No. 2024HLXJS29).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Drennan J Murphy A Mccarthy VJC Ball J Duffield C Crouch R et al . The association between nurse staffing and quality of care in emergency departments: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. (2024) 153:104706. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2024.104706

2.

Pearce S Marr E Shannon T Marchand T Lang E . Overcrowding in emergency departments: an overview of reviews describing global solutions and their outcomes. Intern Emerg Med. (2024) 19:483–91. doi: 10.1007/s11739-023-03477-4

3.

Elendu C Amaechi DC Okatta AU Amaechi EC Elendu TC Ezeh CP et al . The impact of simulation-based training in medical education: a review. Medicine. (2024) 103:e38813. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000038813

4.

Pietersen PI Bjerrum F Tolsgaard MG Konge L Andersen SAW . Standard setting in simulation-based training of surgical procedures: a systematic review. Ann Surg. (2022) 275:872–82. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005209

5.

Alyateem S Al-Ruzzieh M Shtayeh B Alloubani A . Comparing the efficacy of single-skill and multiple-skill simulation scenarios in advancing clinical nursing competency. Heliyon. (2024) 10:e29931. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29931

6.

Kiessling A Amiri C Arhammar J Lundbäck M Wallingstam C Wikner J et al . Interprofessional simulation-based team-training and self-efficacy in emergency medicine situations. J Interprof Care. (2022) 36:873–81. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2022.2038103

7.

Dawood E Alshutwi SS Alshareif S Shereda HA . Evaluation of the effectiveness of standardized patient simulation as a teaching method in psychiatric and mental health nursing. Nurs Rep. (2024) 14:1424–38. doi: 10.3390/nursrep14020107

8.

Bandura A Walters RH . Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall (1977).

9.

Meshel A Iavicoli L Dilos B Agriantonis G Kessler S Fairweather P et al . Strategic educational expansion of trauma simulation initiative via a plan-do-study-act ramp. West J Emerg Med. (2023) 24:76–8. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2022.12.57735

10.

Wallander Karlsen MM Sørensen AL Finsand C Sjøberg M Lieungh M Stafseth SK . Combining clinical practice and education in critical care nursing-a trainee program for registered nurses. Nurs Open. (2023) 10:3666–76. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1617

11.

Eickelmann AK Waldner NJ Huwendiek S . Teaching the technical performance of bronchoscopy to residents in a step-wise simulated approach: factors supporting learning and impacts on clinical work - a qualitative analysis. BMC Med Educ. (2021) 21:597. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-03027-6

12.

Xie L Feng M Cheng J Huang S . Developing a core competency training curriculum system for emergency trauma nurses in China: a modified Delphi method study. BMJ Open. (2023) 13:e066540. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-066540

13.

Smith A Kj C . Triage decision-making skills: a necessity for all nurses. J Nurses Staff Dev. (2010) 26:E14–9. doi: 10.1097/NND.0b013e3181bec1e6

14.

Ouwens M Hulscher M Akkermans R Hermens R Grol R Wollersheim H . The team climate inventory: application in hospital teams and methodological considerations. Qual Saf Health Care. (2008) 17:275–80. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2006.021543

15.

Connor K Davidson J . Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor‐Davidson resilience scale (CD‐RISC). Depress Anxiety. (2003) 18:76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113

16.

Coker AC Omoluabi PF . Validation of Maslach burnout inventory. Ife Psychol. (2009) 17:231–42. doi: 10.4314/ifep.v17i1.43750

17.

Hwang SY Yen M Lee BO Huang MC Tseng HF . A critical thinking disposition scale for nurses: short form. J Clin Nurs. (2010) 19:3171–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03343.x

18.

Lowe AE Kraft C Kortepeter MG Hansen KF Sanger K Johnson A et al . Developing a rapid response single Irb model for conducting research during a public health emergency. Health Sec. (2022) 20:S-60–70. doi: 10.1089/hs.2021.0181

19.

Senken B Welch J Sarmiento E Weinstein E Cushman E Kelker H . Factors influencing emergency medicine worker shift satisfaction: a rapid assessment of wellness in the emergency department. JACEP Open. (2024) 5:e13315. doi: 10.1002/emp2.13315

20.

Dawe J Cronshaw H Frerk C . Learning from the multidisciplinary team: advancing patient care through collaboration. Br J Hosp Med. (2024) 85:1–4. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2023.0387

21.

Hosseini M Heydari A Reihani H Kareshki H . Resuscitation team members 'experiences of teamwork: a qualitative study. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. (2022) 27:439–45. doi: 10.4103/ijnmr.ijnmr_294_21

22.

Lapierre A Lavoie P Castonguay V Lonergan AM Arbour C . The influence of the simulation environment on teamwork and cognitive load in novice trauma professionals at the emergency department: piloting a randomized controlled trial. Int Emerg Nurs. (2023) 67:101261. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2022.101261

23.

Joseph A Jose TP . Coping with distress and building resilience among emergency nurses: a systematic review of mindfulness-based interventions. Indian J Crit Care Med. (2024) 28:785–91. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-24761

24.

Lan L Zhou M Wang L Chen X Dai M Zhang J . Enhancing emergency nurses' disaster nursing ability and psychological resilience: a randomized controlled trial. Emerg Med Int. (2023) 2023:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2023/6108057

25.

Wang Y Liang Y Zheng X Zhang X Feng L . Exploring the genuine psychological experiences of novice nurses at emergency resuscitation events: a qualitative interview study. Heliyon. (2024) 10:e35153. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e35153

26.

Kavakli O Konukbay D . How simulation training for nursing students in emergency internships affects triage decision-making and anxiety: a quasi-experimental study. Heliyon. (2024) 10:e35626. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e35626

27.

Murphy M Mccloughen A Curtis K . Using theories of behaviour change to transition multidisciplinary trauma team training from the training environment to clinical practice. Implement Sci. (2019) 14:43. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0890-6

28.

Arnal-Velasco D Heras-Hernando V . Learning from errors and resilience. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. (2023) 36:376–81. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000001257

29.

Choi MJ Kim KJ . Effects of team-based mixed reality simulation program in emergency situations. PLoS One. (2024) 19:e0299832. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0299832

30.

Blissett S Skinner J Banner H Cristancho S Taylor T . How do residents respond to uncertainty with peers and supervisors in multidisciplinary teams? Insights from simulations with epistemic fidelity. Adv Simul. (2024) 9:8. doi: 10.1186/s41077-024-00281-8

31.

Panda S Dash M John J Rath K Debata A Swain D et al . Challenges faced by student nurses and midwives in clinical learning environment - a systematic review and meta-synthesis. Nurse Educ Today. (2021) 101:104875. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104875

Summary

Keywords

emergency nursing, standardized training, real rescue, rapid response, team collaboration, stress resistance

Citation

Feng T, Hu L, Yang Y, Du C and Li J (2025) Effective strategies for cultivating rapid response, team collaboration, and stress resistance in emergency standardized training nurses during real rescue. Front. Med. 12:1683359. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1683359

Received

11 August 2025

Accepted

22 September 2025

Published

06 October 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Michael J. Wolyniak, Hampden–Sydney College, United States

Reviewed by

Ali Malik Tiryag, University of Basrah, Iraq

Tammy Sadighi, Florida Gulf Coast University, United States

Qiulan Hu, Ganmei Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University (The First People's Hospital of Kunming), China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Feng, Hu, Yang, Du and Li.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Junjie Li, 19118934160@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.