Abstract

Haemophilus influenzae is a bacterium that typically colonizes the human respiratory tract. However, it can also infect the eyes, potentially leading to endophthalmitis. The general prognosis of endophthalmitis is often poor, frequently resulting in decreased visual acuity. We present the case of a 71-year-old male who experienced sudden blurring of vision, pain, and a significant hypopyon in the fundus of his right eye resulting from Haemophilus influenzae. According to previous reports, many cases of Haemophilus influenzae endophthalmitis have poor outcomes, often resulting in permanent visual impairment. However, the patient achieved an excellent prognosis in our case due to prompt diagnosis and emergent treatment.

Introduction

Haemophilus influenzae (H. influenzae) typically colonizes the human respiratory tract and is known to cause meningitis and epiglottitis in children and pneumonia in adults. However, H. influenzae can occasionally colonize the eyes. This bacterium can be classified into encapsulated and unencapsulated strains, with encapsulated strains being more virulent. It is primarily transmitted through airborne droplets or direct contact with secretions from infected individuals (1).

Endophthalmitis is an inflammatory condition of the intraocular fluids, including the vitreous and aqueous humor. It is categorized into three types: postoperative endophthalmitis, post-traumatic endophthalmitis, and endogenous endophthalmitis (EE). EE accounts for approximately 2 to 8% of all cases of endophthalmitis.

Without timely diagnosis and treatment, endophthalmitis can lead to severe complications and poor visual outcomes. Prompt treatment is, therefore, essential for visual recovery. Studies have shown that EE primarily occurs in immunocompromised individuals, such as those with diabetes or suppressed immune systems (2). Common EE-associated pathogens include Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Candida albicans, and Aspergillus. However, H. influenzae is a rare causative agent of EE (2).

According to previous literature, the prognosis of H. influenzae endophthalmitis is generally poor (2). However, in the case we present, the outcome was remarkably favorable. The patient showed no conjunctival congestion, a clear cornea, and no hypopyon in the anterior chamber. Most notably, the patient reported that his visual acuity returned to its pre-illness baseline.

Case report

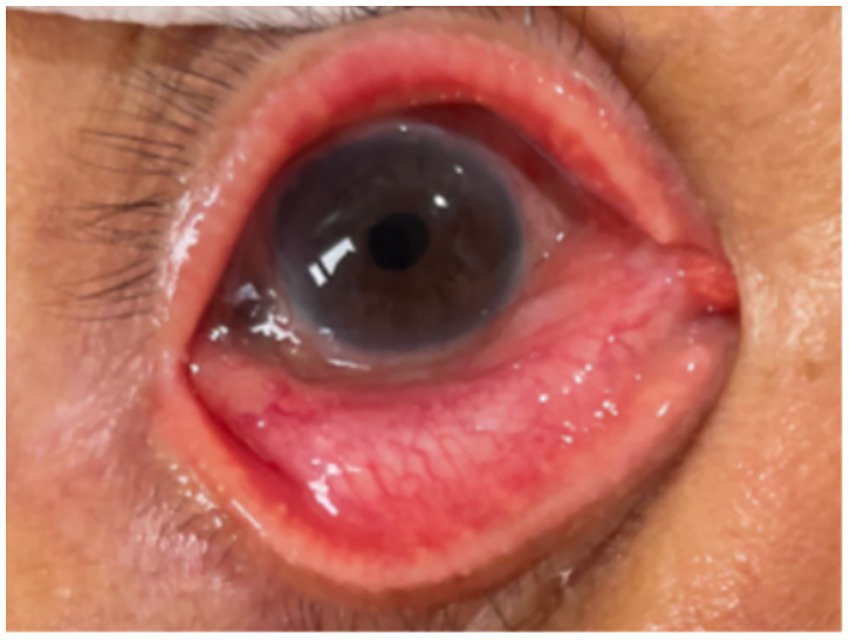

We present the case of a 71-year-old man who experienced a sudden onset of blurred vision and mild pain in his right eye. He had no recent history of ocular surgery or trauma. Ocular examination revealed hypopyon in the right eye (Figure 1). His underlying medical conditions included oral cancer, Behçet’s disease, and benign prostatic hyperplasia. For the management of his Behçet’s disease, the patient was receiving Leflunomide (20 mg daily), a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD).

Figure 1

PSO 1 day. Hypopyon in the right eye. *PSO: post-symptom onset.

Upon arrival at the emergency department (ED), his vital signs were stable: blood pressure of 157/79 mmHg, heart rate of 96 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute, body temperature of 37.1 °C, and oxygen saturation (SpO₂) of 98%. Laboratory tests showed no leukocytosis or elevated C-reactive protein (CRP).

A slit-lamp ophthalmic examination of the right eye revealed the following: Best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of hand movement (HM) at 1meter, IOP (intraocular pressure) of 35 mmHg, congested conjunctiva, mild corneal edema with diffuse fine keratic precipitates (KPs), the cell grade of the anterior chamber of 3+, the grade of aqueous flare of 1 + and the fundus being veiled due to vitreous opacity. Blood culture results confirmed Haemophilus influenzae.

In the ED, the patient was prescribed Combigan (brimonidine tartrate and timolol maleate) (twice daily), Econopred (prednisolone acetate 1% per ml) (every 3 h), and Levofloxacin (5 mg/mL) (every 2 h) eye drops. He received an immediate intravitreal injection (IVI) of vancomycin, ceftazidime, and dexamethasone, with a repeat IVI administered three days later and three additional weekly injections.

In the infection ward, initial systemic antibiotic treatment with Cefoperazone (1 g every 12 h) and Sulbactam (1 g every 12 h) was later switched to ceftriaxone (2 g every 12 h) after being confirmed as H. influenzae.

Extensive investigations were performed to identify the primary infection focus. The patient remained afebrile during his hospital stay. Abdominal CT, cardiac echocardiography, and brain CT angiography showed no abscess, vegetation, valvular disease, or intracranial lesion. Tumor marker screening revealed no evidence of metastasis or malignancy contributing to the vision defect.

After approximately four weeks of ceftriaxone treatment and ocular treatments, the patient’s BCVA improved to 0.1. This was a significant improvement from hand movement at 1 meter upon presentation, and the patient considered this outcome to be a restoration of his functional baseline vision. The patient showed no conjunctival congestion, a clear cornea, and no hypopyon in the anterior chamber (Figure 2). Following this, his topical regimen was adjusted to include Sinomin (sulfamethoxazole 4%) eye drops for two months and Flucason (fluorometholone 0.1%) eye drops for three months, which were gradually tapered. His intraocular pressure (IOP) was well-controlled with the continuous use of Timoptol XE (timolol maleate 0.5%) eye drops. The patient’s condition, including visual acuity and IOP, remained stable throughout the five-month follow-up period.

Figure 2

PSO 25 days. Resolution of hypopyon. *PSO: post-symptom onset.

Discussion

While intraocular fluid culture is the diagnostic gold standard for endophthalmitis, this procedure was deferred. Given the patient’s positive blood culture clearly identifying H. influenzae and the critical need to preserve vision, the clinical team prioritized immediate therapeutic intervention over the procedural risks of a vitreous tap or biopsy. Similarly, further characterization of the bacterial strain through biotyping or serotyping was not performed, as this is not standard procedure in our clinical laboratory. These factors represent limitations in our case report.

Our patient, who was immunocompromised due to squamous cell carcinoma and Behçet’s disease, was at increased risk for endophthalmitis and possibly had poor outcomes. Nevertheless, he remarkably recovered due to timely and appropriate treatments, including intravitreal injections and systemic antibiotics.

Endogenous endophthalmitis is a rare but serious condition, accounting for only 5–15% of all endophthalmitis cases. H. influenzae is an uncommon cause of endogenous endophthalmitis (2).

We summarized the 23 H. influenzae-related endogenous endophthalmitis cases, including the four cases reported by A. Gupta (3). One case worsened to a visual acuity (VA) 4/60, two cases required evisceration, and one case progressed to enucleation. However, the report did not mention the patient’s background. We organized 19 cases in Table 1, including detailed patient backgrounds (1, 4–6). Most of them (17/19) were immunocompetent, and only two (2/19) of them resolved (1, 5). Overall, nearly 90% resulted in poor visual outcomes. The Endophthalmitis Vitrectomy Study (EVS), focusing on the management of endophthalmitis, did not include data on H. influenzae (3). No evidence to support aggressive treatment for endophthalmitis caused by H. influenza. Therefore, close monitoring and clinical judgment remain the most important considerations (3).

Table 1

| Case, reference, year published | Age, sex | Immune status | Clinical presentation | outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Boomla and Quilliam (1981) (1) | 20-month-old, F | Healthy | Red right eye, hazy cornea without ulceration, and hypopyon obscuring the fundus | Resolved with subconjunctival gentamicin and systemic ampicillin, cloxacillin, and gentamicin. |

| 2. Yoder et al. (2004) (4) | 16 patients, median age of 68 years (range, 6 months–83 years) | Healthy | post-trabeculectomy (n = 7), post–cataract surgery (n = 6), post–pars plana vitrectomy (n = 1), post–secondary intraocular lens insertion (n = 1), Post-suture removal (extracapsular cataract wound) (n = 1) |

Poor visual outcomes despite prompt intravitreal antibiotic treatment, which was effective against the organisms. |

| 3. Haruta et al. (2017) (5) | 1-year-old, F | Hyposplenism | Cloudy cornea in the right eye, IP = 43 mmHg, 8-day fever. | Resolved with intravenous meropenem/vancomycin, topical gatifloxacin/cefmenoxime drops, and vitrectomy. VA was 20/40. |

| 4. Tabuenca Del Barrio et al. (2021) (6) | 13-year-old, M | immunocompetent | right eye pain with floaters and decreased VA | Poor visual outcome |

Haemophilus influenzae-related endogenous endophthalmitis cases from the literature.

VA: Visual Acuity, IP: intraocular pressure, F: Female, M: Male.

A key aspect of our case is the favorable outcome, which contrasts with the poor prognosis reported in nearly 90% of previous cases. Our therapeutic strategy, which involved a total of five intravitreal injections and a prolonged four-week course of systemic ceftriaxone, represents an aggressive management approach. This intensive regimen may be a key factor in our patient’s successful visual recovery and could serve as a potential model for future cases. The issue of antibiotic resistance is a growing concern in ophthalmology. As noted, H. influenzae strains, particularly non-typeable strains (NTHi), increasingly exhibit beta-lactamase production and resistance to multiple drug classes. This underscores the importance of appropriate antibiotic selection and stewardship. In light of rising resistance, exploring alternative or adjunctive therapies is warranted. For instance, the use of broad-spectrum antiseptics is gaining attention as a therapeutic approach due to their nonselective mechanisms of action, which may circumvent conventional resistance pathways (7). While not applied in our case, such strategies may become increasingly important in managing ocular infections.

Regarding the reason why H. influenzae infects human eyes, it is associated with systemic infection, and bacteria may spread from the infection focus to the eyes through the bloodstream. The source of the infection may also come from the upper respiratory tract (8). Endogenous bacteria can cause endophthalmitis by crossing the blood-ocular barrier of the eyes, originating from an infection focus in distant organs. Infection sources may come from endocarditis, meningitis, or urinary tract infection. In our patient, extensive investigations including abdominal CT, cardiac echocardiography, and brain CT angiography were performed, but they did not reveal a definitive primary focus of infection. However, considering that the upper respiratory tract is the natural reservoir for H. influenzae, a subclinical infection or colonization at this site represents the most likely portal of entry for hematogenous spread. Besides, patients with immune deficiency are more prone to endophthalmitis, such as diabetes mellitus (DM), cancer, use of immunosuppressive medication, or old age (9). However, an immunocompetent host can still develop endophthalmitis (6).

Regarding the new insights on H. influenzae, it is classified into eight biotypes and six serotypes. Biotypes and serotypes may determine the patterns of colonization of H. influenzae and influence the severity of the infection. Alrawi AM group found that endophthalmitis is mainly caused by Biotype II of H. influenzae (8). Recent studies found that biotype II of non-encapsulated H. influenzae covered most ocular H. influenzae isolates. However, recent studies could not conclude the direct relationship between H. influenzae subtype and location of ocular infection. The spleen plays a crucial role in eliminating encapsulated bacteria like H. influenzae. Patients with hyposplenism may be prone to bloodstream infection of H. influenzae and endogenous endophthalmitis (5).

For the current antibiotic resistance status of H. influenzae, many strains produce beta-lactamase enzymes to resist ampicillin. There are also minor strains that belong to non-beta-lactam-resistance types, showing resistance to macrolides, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (10). Since the introduction of the H. influenzae type b (Hib) vaccine in 1985 in the United States and 1996 in Taiwan, the Hib infection rate has gradually decreased, and the younger generation is now infected mainly by non-typeable H. influenzae (NTHi) (8). NTHi strains often exhibit increased beta-lactam resistance due to their production of beta-lactamase. Besides, the rise of multidrug-resistant (MDR) (NTHi) is becoming an increasingly serious public health concern in Taiwan (11).

Many studies showed that endophthalmitis resulting from H. influenzae infection typically leads to poor visual outcomes even with prompt antibiotic treatment and often requires vitrectomy (6). Endophthalmitis resulting from H. influenzae may not lead to death, but endophthalmitis caused by filamentous fungi may be more prone to causing death (12). Recently, medical management consists of intravitreal antibiotics, systemic antibiotics, topical and subconjunctival antibiotics, corticosteroids, and surgical management. Our case, even in the immunocompromised conditions, presented with a good clinical outcome under appropriate and aggressive treatments. The best way to prevent a worse outcome in endophthalmitis caused by H. influenzae may be to use the proper treatment promptly, carefully monitor the patient’s condition, and adjust the treatment accordingly.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional review board of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

CT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation. L-TL: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. EH: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. S-YS: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. J-JT: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Formal analysis, Data curation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Boomla K Quilliam RP . Haemophilus influenzae endophthalmitis. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). (1981) 282:989–90. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6268.989-c

2.

Gajdzis M Figuła K Kamińska J Kaczmarek R . Endogenous Endophthalmitis-the clinical significance of the primary source of infection. J Clin Med. (2022) 11:1183. doi: 10.3390/jcm11051183

3.

Gupta A Orlans HO Hornby SJ Bowler ICJW . Microbiology and visual outcomes of culture-positive bacterial endophthalmitis in Oxford, UK. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. (2014) 252:1825–30. doi: 10.1007/s00417-014-2658-7

4.

Yoder DM Scott IU Flynn HW Jr Miller D . Endophthalmitis caused by Haemophilus influenzae. Ophthalmology. (2004) 111:2023–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.05.018

5.

Haruta M Yoshida Y Yamakawa R . Pediatric endogenous Haemophilus influenzae endophthalmitis with presumed hyposplenism. Int Med Case Rep J. (2017) 10:7–9. doi: 10.2147/IMCRJ.S123524

6.

Del Barrio LT Cuadrado MM Silva EC De Madrid DAP Mulero HH . Haemophilus Influenzae endogenous Endophthalmitis in an immunocompetent host. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. (2021) 29:1381–3. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2020.1767794

7.

Dell’Annunziata F Morone MV Gioia M Cione F Galdiero M Rosa N . Broad-Spectrum antimicrobial activity of Oftasecur and Visuprime ophthalmic solutions. Microorganisms. (2023) 11:503. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11020503

8.

Alrawi AM Chern KC Cevallos V Lietman T Whitcher JP Margolis TP et al . Biotypes and serotypes of Haemophilus influenzae ocular isolates. Br J Ophthalmol. (2002) 86:276–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.3.276

9.

Cunningham ET Flynn HW Relhan N Zierhut M . Endogenous Endophthalmitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. (2018) 26:491–5. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2018.1466561

10.

Bispo PJM Sahm DF Asbell PA . A systematic review of multi-decade antibiotic resistance data for ocular bacterial pathogens in the United States. Ophthalmol Ther. (2022) 11:503–20. doi: 10.1007/s40123-021-00449-9

11.

Wan TW Huang YT Lai JH Chao QT Yeo HH Lee TF et al . The emergence of transposon-driven multidrug resistance in invasive nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae over the last decade. Int J Antimicrob Agents. (2024) 64:107319. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2024.107319

12.

Sheu SJ . Endophthalmitis. Korean J Ophthalmol. (2017) 31:283–9. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2017.0036

Summary

Keywords

endogenous endophthalmitis, haemophilus influenzae , intravitreal injection, oral cancer, Behçet disease

Citation

Tsai CH, Liu L-T, Hsu EC, Sung S-Y and Tsai J-J (2025) Case Report: An endogenous endophthalmitis case caused by Haemophilus influenzae. Front. Med. 12:1692870. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1692870

Received

27 August 2025

Accepted

09 October 2025

Published

27 October 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Ryoji Yanai, Tokushima University, Japan

Reviewed by

Ferdinando Cione, University of Salerno, Italy

Cao Gu, Second Military Medical University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Tsai, Liu, Hsu, Sung and Tsai.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jih-Jin Tsai, jijits@cc.kmu.edu.tw

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.