Abstract

Background:

The development of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HCT) remains an unresolved clinical problem. However, developing a risk stratification tool for BOS risk is challenging as numerous factors contribute to its development. Moreover, allo-HCT may lead to a decrease in respiratory mucosal surface defense function, resulting in recurrent inflammation and fibrosis. Previous studies have shown that immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgA levels significantly decrease after lung transplantation and are associated with BOS. Therefore, we hypothesized that immunoglobulin levels of patients may also decrease after allo-HCT, and may even be risk factor for the development of BOS.

Methods:

In this retrospective study, a total of 134 patients were enrolled. According to the presence of BOS, these patients were divided into BOS and non-BOS groups. Clinical information and immunoglobulin levels were analyzed between the two groups. Immunoglobulin levels of patients before and after transplantation were compared. Binary logistic regression and Cox regression were used to identify variables with independent prognostic significance.

Results:

ABO incompatible, human leukocyte antigen (HLA) mismatch, lung infection within 100 days post-transplantation, cytomegalovirus (CMV) serology positivity, and pre-transplant IgA immunoglobulin deficiency were risk factors for BOS after allo-HCT. Following transplantation, IgA and IgM levels significantly decreased, and many patients had levels below the reference values. In addition, the serum IgA levels prior to transplantation were lower in the BOS group than the non-BOS group. In multivariate models, pre-transplant IgA deficiency was a risk factor for BOS.

Conclusion:

Following allo-HCT, IgA and IgM levels decreased, and numerous patients had levels below the reference values. In multivariate models, pre-transplant IgA deficiency was identified as a risk factor for BOS.

1 Introduction

Bronchiolitis obliterans (BO) is characterized by persistent inflammation and fibrosis of the small airways, resulting in narrowing and/or complete occlusion of the airway lumen (1); ultimately, this condition may even lead to lung failure. Injury and small airway inflammation can be caused by various factors, such as infection, graft-versus-host immune responses, rejection, chemical inhalation, and autoimmune diseases. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) is characterized by airflow obstruction and small airway disease features on high-resolution computed tomography in patients undergoing lung transplantation or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HCT), without the need for pathological confirmation of BO (2).

Respiratory virus infection (3), human leukocyte antigen (HLA) mismatch (4), and positive serology in patients with cytomegalovirus (CMV) (5) are risk factors for the occurrence of BOS. However, the development of a risk stratification tool for BOS is challenging. Currently, there is no specific treatment for BOS; thus, it is important to reduce the incidence of BOS by implementing certain measures.

The respiratory mucosal surface area exceeds 400 m2 and contains a large number of potential pathogens (6). The barrier function on the mucosal surface, secretion of antimicrobial peptides and proteins, and body fluids of the immune system, especially immunoglobulin A (IgA) and IgG, can inhibit the pathogenic effects of pathogens. Previous studies have shown that hypogammaglobulinemia was common after organ transplantation and associated with surgical infection complications (7). Following lung transplantation, IgG and IgA levels significantly decreased and were associated with BOS (8). Given the incidence of immunoglobulin deficiency after organ transplantation and the role of low immunoglobulin in the pathogenesis of BOS, we hypothesized that immunoglobulin deficiency, particularly IgA deficiency, is an important driving factor for BOS after HCT. Moreover, further understanding the role of immunoglobulin in BOS can promote the development of targeted immunotherapy, thereby delaying or preventing the occurrence and development of BOS.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design

In this retrospective study, a total of 134 patients were enrolled. The inclusion criteria were: (1) the guardians of the patients agreed to receive allo-HCT at the First Affiliated Hospital Zhengzhou University and provided written informed consent (transplantation period: January 1, 2019—December 31, 2022); (2) patient age ranging: 0–16 years; (3) clear diagnosis of the primary disease and meeting the indications of allo-HCT; (4) complete clinical data; and (5) survival for at least 100 days after allo-HCT. The exclusion criteria were: (1) refusal to follow up; and (2) diagnosis of pulmonary disease or dysfunction (e.g., asthma, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, post-infection BO, cystic fibrosis, pulmonary hypertension) prior to transplantation. This study was approved by the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University.

2.2 Definition of BOS after allo-HCT

Following allo-HCT, the diagnosis of BOS was based on the following diagnostic criteria (9) of the pulmonary function test in the revised NIH standard (10): (1) forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) < 75% of predicted or a decrease of the FEV1 by 10% in comparison to the pretransplant value; (2) FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) < 70%; (3) residual volume (RV) or RV/total lung capacity (TLC) > 120% of predicted; and (4) evidence of air trapping on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT).

2.3 Measurements of immunoglobulin levels

The levels of IgA, IgG, IgM, C3 and C4 were collected before allo-HCT related immunosuppression or myeloablative treatment and after allo-HCT. The normal reference values for IgG, IgA, and IgM are > 7, > 1, > 0.4 g/L, respectively, as previously reported (11). Immunoglobulin deficiency is defined as serum levels below the lower limit of the predicted normal value.

2.4 Clinical information

Clinical parameters data were collected, including age at onset, recipient sex, recipient age, donor sex, underlying disease, time from diagnosis to transplant, months, donor type, ABO blood type, HLA, use of busulfan, antithymocyte globulin (ATG), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), pulmonary infection within 100 days prior to transplant, pulmonary infection within 100 days after transplantation, and infection with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) or CMV following transplantation.

2.5 Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed by SPSS version 27.0 software. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov method was used to analyze the normality of continuous variables. For normally distributed data, the independent t-test was used to compare the differences between continuous variables; for non-normally distributed data, the Mann–Whitney U-test was used. Categorical data analysis and comparison of the two groups were conducted using the chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests. Paired t-tests were performed to compare data obtained before and after allo-HCT in patients. The results were presented as the mean ± standard deviation for numerical variables and number (percent) for categorical data. Binary logistic regression was used to analyze risk factors for BOS. Cox regression was used to identify variables with independent prognostic significance. P < 0.05 indicate statistically significant difference.

3 Results

3.1 Clinical and transplant features of patients

A total of 134 patients who underwent allo-HCT at the First Affiliated Hospital Zhengzhou University from January 1, 2019 to December 31, 2022 were enrolled in this study. The clinical and transplant characteristics are shown in Table 1. Pulmonary function tests of BOS group after transplantation were as follows: FEV1% (51.89 ± 15.892)%, FEV1/FVC (62.76 ± 8.179)%, maximum mid-term expiratory flow rate (28.26 ± 10.269) L/s, FEF75% (23.76 ± 10.181)%. And air trapping signs can be seen on lung CT of children in the BOS group. There were no differences in the age at onset and the age of recipients between the BOS and non-BOS group. Moreover, there were no differences between the two groups in the sex ratio of donors and recipients, the usage of busulfan, ATG, and MSCs. Patients had higher ratio of ABO incompatibility (79% vs. 48%, p = 0.046), HLA mismatch (86% vs. 52%, p = 0.022), and co-existence of rejection and infection after-transplantation in the BOS group than the non-BOS group. Additionally, more patients in the BOS group had lung infection within 100 days after-transplantation (79% vs. 51%, p = 0.049) and CMV infection after-transplantation (50% vs. 20%, p = 0.012) compared with the non-BOS group. The probability of developing extrapulmonary organ rejection was higher for patients with BOS than for those without BOS (79% vs. 42%, p = 0.012). However, since chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) was included as one of the criteria in defining BOS in this study, it was not included for the subsequent analysis of BOS risk factors.

TABLE 1

| Clinical variable | BOS (n = 14) | Non-BOS (n = 120) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset age (month) | 70.9 ± 45.083 | 92.8 ± 48.282 | 0.108 |

| Recipient age (month) | 86.7 ± 52.60 | 107.9 ± 47.02 | 0.117 |

| Recipient sex, male | 8(57) | 82(68) | 0.548 |

| Donor sex, male | 8(57) | 79(66) | 0.561 |

| Underlying disease | |||

| AA | 5(36) | 55(46) | 0.511 |

| ALL | 4(28.5) | 19(16) | |

| AML | 4(28.5) | 27(22) | |

| Other | 1(7) | 19(16) | |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant, months | 15.9 ± 24.95 | 15.2 ± 24.78 | 0.92 |

| Donor type | |||

| Sibling/unrelated | 5(36)/9(64) | 70(58)/50(42) | 0.154 |

| ABO | |||

| Compatibility/incompatibility | 3(21)/11(79) | 62(52)/58(48) | 0.046 |

| HLA | |||

| Full match/mismatch | 2(14)/12(86) | 57(48)/63(52) | 0.022 |

| Busulfan-based/other | 13(93)/1(7) | 91(76)/29(24) | 0.191 |

| ATG/other | 12(86)/2(14) | 97(81)/23(19) | 0.742 |

| MSCs/other | 11(79)/3(21) | 84(70)/36(30) | 0.559 |

| Acute GVHD/other | 8(57)/6(43) | 45(38)/75(62) | 0.247 |

| Extrapulmonary organ rejection/other | 11(79)/3(21) | 51(42)/69(58) | 0.012 |

| Pulmonary infection within 100 days pre-transplantation | 8(57)/6(43) | 46(38)/74(62) | 0.249 |

| Pulmonary infection within 100 days after-transplantation | 11(79)/3(21) | 61(51)/59(49) | 0.049 |

| Infection within 100 days after-transplantation | 11(79)/3(21) | 69(58)/51(42) | 0.128 |

| EB virus infection after transplantation | 0(0)/14(100) | 4(3)/116(97) | 0.488 |

| CMV virus infection after transplantation | 7(50)/7(50) | 24(20)/96(80) | 0.012 |

| Rejected organ | |||

| Lung | 2(14) | 0(0) | < 0.001 |

| Skin | 4(29) | 31(26) | |

| Liver | 0(0) | 2(2) | |

| Intestine | 0(0) | 7(6) | |

| Two or more organs | 7(50) | 11(9) | |

| None | 1(7) | 69(57) | |

| Co-existence of rejection and infection after-transplantation | 6(43) | 8(7) | < 0.001 |

Clinical characteristics of patients with and without BOS.

AA, aplastic anemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; ABO, ABO blood group; ATG, anti-human thymoglobulin; BOS, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome; CMV virus, Cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells. Data are expressed as median ± standard deviation or numbers (%).

3.2 Lower immunoglobulin levels after allo-HCT

However, the immunoglobulin levels in children before and after allo-HCT remain unknown. Therefore, in this study, we analyzed the immunoglobulin levels of the children before and after allo-HCT. The results showed that 38.3%, 17.9, and 14.2% of the patients were IgA-deficient (1.25 ± 0.762 g/liter), IgM-deficient (0.90 ± 0.531 g/L), and IgG-deficient (10.27 ± 4.206 g/liter) (Figure 1), respectively, before allo-HCT related immunosuppression or myeloablative treatment. Only modest correlations were observed between IgM and IgA levels, IgG and IgA levels, and IgG and IgM levels (r = 0.229, p = 0.008; r = 0.326, p < 0.001; r = 0.247, p = 0.004). The levels of IgA (0.47 ± 0.362 vs. 1.25 ± 0.762, p < 0.001), IgM (0.58 ± 0.518 vs 0.90 ± 0.531, p < 0.001) and C3 (1.09 ± 0.184 vs. 1.15 ± 0.210, p = 0.017) after-transplant were significantly lower after transplantation than before transplantation. However, there was no significant change in the levels of IgG and C4 after allo-HCT (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

Immunoglobulin levels before and after transplantation. The levels of IgA and IgM and C3 were significantly lower post-transplantation than before transplantation (A,B,D). There were no significant differences in the levels of IgG and C4 before and after transplantation (C,E). IgA, immunoglobulin A; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M.*p < 0.05 vs. pre-transplant.

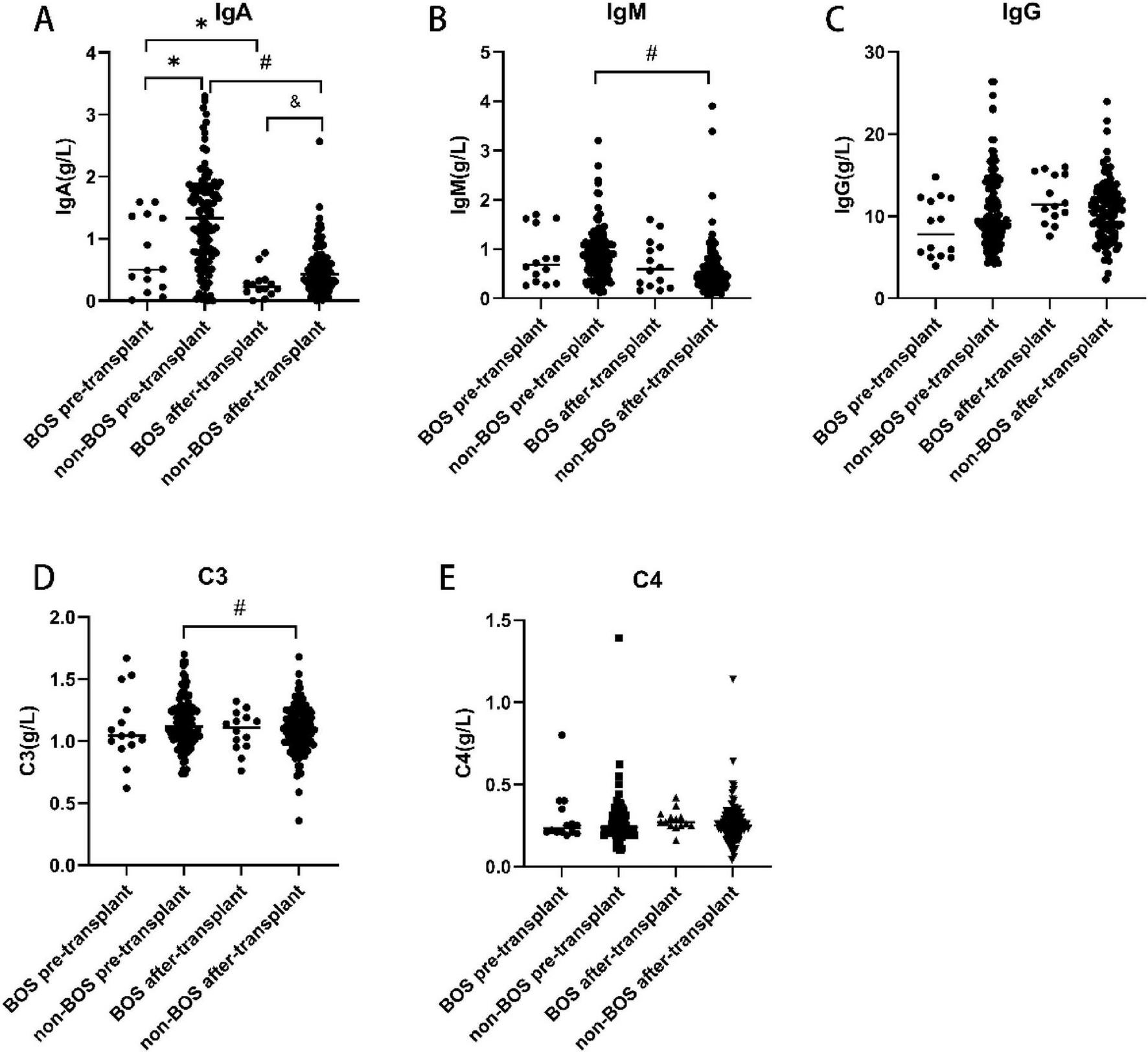

3.3 Immunoglobulin levels before and after allo-HCT in BOS and non-BOS groups

Both the BOS group (0.27 ± 0.216 g/L vs. 0.76 ± 0.620 g/L, p = 0.013) and non-BOS group had lower IgA levels after transplantation than before transplantation (0.49 ± 0.367 g/L vs. 1.31 ± 0.751 g/L, p < 0.001). In addition, the IgA levels before (p = 0.012) and after (p = 0.027) transplantation were significantly lower in the BOS group than the non-BOS group. The levels of IgM (0.57 ± 0.522 g/L vs. 0.91 ± 0.531 g/L, p < 0.001) and C3 (1.09 ± 0.187 vs. 1.15 ± 0.199, p = 0.011) after transplantation were also significantly lower in the non-BOS group than the non-BOS group. In the BOS group, the IgM levels were lower after transplantation than before transplantation; however, the difference was not statistically significant. Of note, there were no difference in IgG and C4 levels between the groups (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2

Immunoglobulin levels before and after transplantation in the BOS and non-BOS group. The levels of IgA were significantly lower in the BOS group than the non-BOS group (before and following transplantation) (A). In the non-BOS group, the levels of IgM and C3 were markedly lower after transplantation than before transplantation (B,D). There were no differences in IgG and C4 levels among groups (C,E). BOS, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome; IgA, immunoglobulin A; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M. *p < 0.05 vs. BOS pre-transplant, #p < 0.05 vs. non-BOS pre-transplant, &p < 0.05 vs. BOS after-transplant.

3.4 Serum IgA levels before transplantation were associated with prevalence and incidence of BOS

The results of the multivariate analysis of IgA and IgM levels were summarized in Tables 2, 3. Recipient age was identified as independent predictors of low post-transplantation serum IgA levels (Table 2). Recipient age was identified as an independent predictor of low post-transplantation serum IgM levels (Table 3).

TABLE 2

| Variables | β (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | ||

| Onset age (month) | 0.002(0.000, 0.003) | 0.009 |

| Recipient age (month) | 0.002(0.001, 0.004) | < 0.001 |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant, months | 0.002(0.000, 0.005) | 0.060 |

| Presence of BOS | −0.225(−0.424, −0.027) | 0.027 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||

| Recipient age (month) | 0.002(0.001, 0.003) | 0.002 |

Factors significantly associated with serum IgA level after transplantation.

CI, confidence interval.

TABLE 3

| Variables | β (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | ||

| Onset age (month) | 0.002(0.001, 0.004) | 0.051 |

| Recipient age (month) | 0.003(0.001, 0.004) | 0.004 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||

| Recipient age (month) | 0.004(0.001, 0.008) | 0.020 |

Factors significantly associated with serum IgM level after transplantation.

CI, confidence interval.

Predictors for BOS are summarized in Table 4. In the univariate analysis, ABO, HLA, pulmonary infection within 100 days after transplantation, CMV infection after transplantation, and IgA levels before and after transplantation were identified predictors. In a multivariate model, lower serum IgA levels before transplantation (hazard ratio,0.259; 95%confifidence interval, 0.081−0.824; p = 0.022) were associated with a higher incidence of BOS.

TABLE 4

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | ||

| ABO (incompatibility) | 3.92(1.041, 14.759) | 0.043 |

| HLA (mismatch) | 5.429(1.165, 25.303) | 0.031 |

| Pulmonary infection within 100 days after-transplantation | 3.546(0.942, 13.353) | 0.061 |

| CMV serology positivity | 4.00(1.280, 12.496) | 0.017 |

| IgA before transplantation | 0.307(0.118, 0.798) | 0.015 |

| IgA after transplantation | 0.038(0.002, 0.621) | 0.022 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||

| IgA before transplantation | 0.259(0.081, 0.824) | 0.022 |

Factors significantly associated with bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome.

CI, confidence interval.

4 Discussion

The present results showed a significant decrease in serum IgA and IgM levels after allo-HCT, with many patients having levels below the reference values. In addition, the serum IgA levels were lower in the BOS group than the non-BOS group prior to transplantation. Moreover, pre-transplantation IgA deficiency was a risk factor for BOS onset in multivariate modeling.

Allo-HCT provides the best chance for cure in many patients with malignant and non-malignant hematologic disorder, such as acute myeloid leukemia (AML), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), myelodysplastic syndrome, aplastic anemia (AA), Mediterranean anemia, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (12), certain solid tumors (13), autoinflammatory disorders (14), and other diseases. The development of BOS after allo-HCT remains an unresolved clinical issue, as once it occurs, treatment becomes difficult (15).

BOS is defined by a progressive obstructive ventilatory impairment resulting from obliterative bronchiolitis (16). Its pathogenesis following allo-HCT involves chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), which arises from a breakdown in central tolerance and dysregulated B-cell activity with autoantibody production (17). Azithromycin represents the most effective initial therapy for BOS, although treatment response rates remain modest, ranging from 29 to 50% (18). Montelukast, an oral agent targeting cysteinyl leukotriene (CysLT) receptors in the airways, has been associated with neuropsychiatric adverse effects—including depression, anxiety, sleep disturbances, agitation, and paresthesia—particularly in patients with a pre-existing psychiatric history (19), regardless of age. Second-line therapeutic options include extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP) and total lymphoid irradiation (TLI) (20). However, ECP is limited by its high cost, limited availability, and logistical challenges. While TLI has been shown to attenuate the decline in FEV1 among BOS patients, the supporting evidence is derived primarily from small observational studies (21). For carefully selected patients who fail first- and second-line therapies, lung re-transplantation represents the principal therapeutic alternative in cases of refractory allograft dysfunction (22). Thus, it is important to prevent its occurrence by implementing appropriate measures. However, the development of a risk stratification tool for BOS is challenging. Peripheral blood as a stem cell source (10), busulfan-based conditioning, unrelated donors, female donors (23), respiratory viral infections (3), HLA mismatch (4), CMV serology positivity (5), etc. are risk factors for the development of BOS. Our results also showed that ABO incompatibility, HLA mismatch, pulmonary infection within 100 days after-transplantation, CMV serology positivity, and pre-transplant IgA deficiency were risk factors for BOS following allo-HCT. Since chronic GVHD was included in the diagnostic criteria, we did not analyze its role as a risk factor for BOS. Therefore, the discovery of additional factors that can exert protective effects on patients receiving allo-HCT plays an important role in preventing the occurrence of BOS.

Immunoglobulin is a heterodimeric protein composed of two heavy chains and two light chains. According to the constant domain of the immunoglobulin heavy chain, it is divided into five categories, namely IgM, IgG, IgA, IgD, and IgE isotypes (24). Immunoglobulin has two main functions of immunoglobulin. Firstly, as a cell surface receptor, it binds to antigens, transmits cell signals, and activates cells. Secondly, as a soluble effector molecule, it independently binds and neutralizes antigens within a certain distance (25). IgM antibodies participate in primary immune responses and are often used clinically to diagnose acute pathogen infections. IgG is a major isotype found in the body that directly contributes to immune responses, including neutralizing toxins and viruses. The levels of IgA in serum are often higher than those of IgM, but markedly lower than the levels of IgG (26). However, IgA is the most abundant immunoglobulin in the mucosa, playing a key role in host defense against inhaled and ingested pathogens and mucosal immune regulation (27). IgA deficiency is physiologic in infants (28). Secretions, such as saliva and breast milk, contain high levels of IgA; IgA in breast milk can provide protection for the intestines of infants. Investigations have shown that a lack of IgA in the bloodstream suggests a similar deficiency in local mucosal IgA, and IgA in the bloodstream plays an important role in lung mucosal defense (11). Previous studies have demonstrated that humoral immunity plays an important role in the evolution of BOS (29) in patients with BOS following lung transplantation (1). Furthermore, IgA (11) and IgG deficiencies after lung transplantation (30, 31) were identified as risk factors for BOS. Our results showed that the levels of IgA and IgM were significantly lower after transplantation than before transplantation. In addition, the serum IgA levels prior to transplantation were lower in the BOS group than the non-BOS group. These results indicate that airway mucosal immunity and acute infection immune response are reduced after allo-HCT, and initial airway mucosal immunity plays an important role in the occurrence and development of BOS. Therefore, except for the recipient age, we hypothesize that the occurrence of BOS can be reduced by improving the immune function of patients.

The present study had certain limitations. This was a single-center retrospective investigation involving a short study period and 14 patients diagnosed with BOS. Research including longer study periods and more patients is warranted to further examine the levels of immunoglobulin in this setting. Furthermore, it is necessary to increase the number of time points for the detection of immunoglobulin levels after transplantation to better understand the changes.

5 Conclusion

Following allo-HCT, IgA and IgM levels decreased, and numerous patients had levels below the reference values. In multivariate models, pre-transplant IgA deficiency was identified as a potential risk factor for BOS.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (Number: 2025-KY-1097–002). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. The manuscript presents research on animals that do not require ethical approval for their study.

Author contributions

YY: Funding acquisition, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Software, Writing – original draft, Investigation. KY: Formal analysis, Resources, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization, Project administration. SL: Software, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Visualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Validation. SZ: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82100092), the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (232300420255 and 222300420334), Henan Provincial Science and Technology Research Project (LHGJ20200380 and LHGJ20200341), and Key Provincial and Ministry Co-construction Projects under the Henan Provincial Medical Science and Technology Tackling Program (SBGJ202102106).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

AA, aplastic anemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; allo-HCT, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; ATG, antithymocyte globulin; BO, bronchiolitis obliterans; BOS, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CysLT, cysteinyl leukotriene; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; ECP, extracorporeal photopheresis; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; HRCT, high-resolution computed tomography; IgA, immunoglobulin A; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; RV, residual volume; TLC, total lung capacity; TLI, total lymphoid irradiation.

References

1.

Deng K Lu G . Immune dysregulation as a driver of bronchiolitis obliterans.Front Immunol. (2024) 15:1455009. 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1455009

2.

Cordier JF . Challenges in pulmonary fibrosis. 2: bronchiolocentric fibrosis.Thorax. (2007) 62:638–49. 10.1136/thx.2004.031005

3.

Khalifah AP Hachem RR Chakinala MM Schechtman KB Patterson GA Schuster DP et al Respiratory viral infections are a distinct risk for bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome and death. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2004) 170:181–7. 10.1164/rccm.200310-1359OC

4.

Walton DC Hiho SJ Cantwell LS Diviney MB Wright ST Snell GI et al HLA matching at the eplet level protects against chronic lung allograft dysfunction. Am J Transplant. (2016) 16:2695–703. 10.1111/ajt.13798

5.

Duque-Afonso J Rassner P Walther K Ihorst G Wehr C Marks R et al Evaluation of risk for bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation with myeloablative conditioning regimens. Bone Marrow Transplant. (2024) 59:1744–53. 10.1038/s41409-024-02422-z

6.

Bäckhed F Ley RE Sonnenburg JL Peterson DA Gordon JI . Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine.Science. (2005) 307:1915–20. 10.1126/science.1104816

7.

Robertson J Elidemir O Saz EU Gulen F Schecter M McKenzie E et al Hypogammaglobulinemia: incidence, risk factors, and outcomes following pediatric lung transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. (2009) 13:754–9. 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2008.01067.x

8.

Heng D Sharples LD McNeil K Stewart S Wreghitt T Wallwork J . Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome: incidence, natural history, prognosis, and risk factors.J Heart Lung Transplant. (1998) 17:9883768.

9.

Jagasia MH Greinix HT Arora M Williams KM Wolff D Cowen EW et al National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: i. The 2014 Diagnosis and Staging Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2015) 21:389–401.e1. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.12.001.

10.

Rhee CK Ha JH Yoon JH Cho BS Min WS Yoon HK et al Risk factor and clinical outcome of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Yonsei Med J. (2016) 57:365–72. 10.3349/ymj.2016.57.2.365

11.

Chambers DC Davies B Mathews A Yerkovich ST Hopkins PM . Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome, hypogammaglobulinemia, and infectious complications of lung transplantation.J Heart Lung Transplant. (2013) 32:36–43. 10.1016/j.healun.2012.10.006

12.

Lv M Huang XJ . Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in China: where we are and where to go.J Hematol Oncol. (2012) 5:10. 10.1186/1756-8722-5-10

13.

D’Souza A Fretham C Lee SJ Arora M Brunner J Chhabra S et al Current use of and trends in hematopoietic cell transplantation in the United States. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2020) 26:e177–82. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2020.04.013

14.

Kanegane H Miyamoto S Kamiya T Ohnishi H Nishikomori R Gennery AR et al Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for autoinflammatory disorders. Int J Hematol. (2025) 122:190–8. 10.1007/s12185-025-04021-0

15.

Duque-Afonso J Ihorst G Waterhouse M Zeiser R Wäsch R Bertz H et al Impact of lung function on bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome and outcome after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation with reduced-intensity conditioning. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2018) 24:2277–84. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.06.024

16.

Verleden GM Glanville AR Lease ED Fisher AJ Calabrese F Corris PA et al Chronic lung allograft dysfunction: definition, diagnostic criteria, and approaches to treatment-A consensus report from the Pulmonary Council of the ISHLT. J Heart Lung Transplant. (2019) 38:493–503. 10.1016/j.healun.2019.03.009

17.

Jaing TH Wang YL Chiu CC . Time to rethink bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome following lung or hematopoietic cell transplantation in pediatric patients.Cancers. (2024) 16:3715. 10.3390/cancers16213715

18.

Gerhardt SG McDyer JF Girgis RE Conte JV Yang SC Orens JB . Maintenance azithromycin therapy for bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome: results of a pilot study.Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2003) 168:121–5. 10.1164/rccm.200212-1424BC

19.

Paljarvi T Forton J Luciano S Herttua K Fazel S . Analysis of neuropsychiatric diagnoses after montelukast initiation.JAMA Netw Open. (2022) 5:e2213643. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.13643

20.

Benden C Haughton M Leonard S Huber LC . Therapy options for chronic lung allograft dysfunction-bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome following first-line immunosuppressive strategies: a systematic review.J Heart Lung Transplant. (2017) 36:921–33. 10.1016/j.healun.2017.05.030

21.

Fisher AJ Rutherford RM Bozzino J Parry G Dark JH Corris PA . The safety and efficacy of total lymphoid irradiation in progressive bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after lung transplantation.Am J Transplant. (2005) 5:537–43. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00709.x

22.

Rucker AJ Nellis JR Klapper JA Hartwig MG . Lung retransplantation in the modern era.J Thorac Dis. (2021) 13:6587–93. 10.21037/jtd-2021-25

23.

Gazourian L Rogers AJ Ibanga R Weinhouse GL Pinto-Plata V Ritz J et al Factors associated with bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome and chronic graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Am J Hematol. (2014) 89:404–9. 10.1002/ajh.23656

24.

Kirkham PM Schroeder HW . Antibody structure and the evolution of immunoglobulin V gene segments.Semin Immunol. (1994) 6:347–60. 10.1006/smim.1994.1045

25.

Schroeder HW Cavacini L . Structure and function of immunoglobulins.J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2010) 125(2 Suppl 2):S41–52. 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.09.046

26.

Woof JM Mestecky J . Mucosal immunoglobulins.Immunol Rev. (2005) 206:64–82. 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00290.x

27.

Bertrand Y Sánchez-Montalvo A Hox V Froidure A Pilette C . IgA-producing B cells in lung homeostasis and disease.Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1117749. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1117749

28.

Cunningham-Rundles C . Physiology of IgA and IgA deficiency.J Clin Immunol. (2001) 21:303–9. 10.1023/a:1012241117984

29.

Magro CM Ross P Kelsey M Waldman WJ Pope-Harman A . Association of humoral immunity and bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome.Am J Transplant. (2003) 3:1155–66. 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00168.x

30.

Kawut SM Shah L Wilt JS Dwyer E Maani PA Daly TM et al Risk factors and outcomes of hypogammaglobulinemia after lung transplantation. Transplantation. (2005) 79:1723–6. 10.1097/01.tp.0000159136.72693.35

31.

Husain S Mooney ML Danziger-Isakov L Mattner F Singh N Avery R et al A 2010 working formulation for the standardization of definitions of infections in cardiothoracic transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. (2011) 30:361–74. 10.1016/j.healun.2011.01.701

Summary

Keywords

bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, immunoglobulin, child, deficiency

Citation

Yue Y, Yan K, Liu S and Zhang S (2026) Immunoglobulin levels of children with bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Front. Med. 12:1692881. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1692881

Received

26 August 2025

Revised

24 November 2025

Accepted

26 November 2025

Published

05 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Lazaros Ignatios Sakkas, University of Thessaly, Greece

Reviewed by

Amrita Dosanjh, Rady Children’s Hospital, United States

Laureline Berthelot, INSERM U1064 Centre de Recherche en Transplantation et Immunologie, France

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Yue, Yan, Liu and Zhang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Suqin Zhang, Qinsu321@126.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.