Abstract

Background:

Failure to extubate successfully from mechanical ventilation is a critical event associated with poor prognosis in ICU patients, significantly prolonging hospital stays and increasing mortality rates. It is widely accepted in academic circles that developing prediction models for extubation failure can facilitate precise extubation decisions. Despite the rapid proliferation of relevant prediction models, their methodological quality and bedside applicability remain ambiguous.

Objective:

This study aims to outline the predictive factors associated with the risk of extubation failure in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and to summarize the existing predictive models.

Methods:

We searched the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang Database, VIP Database, China Biomedical Database, PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library. We included both prospective and retrospective studies that developed or validated risk prediction models for extubation failure in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation in the ICU. The Prediction Model Risk of Bias Assessment Tool (PROBAST) was used to assess the bias and applicability of the models.

Results:

This analysis includes 14 studies. Frequency analysis of the predictors revealed that there are 15 predictors that appeared at least twice, among which mechanical ventilation duration, GCS score, APACHE II score, age, and hemoglobin were the most common predictors. From the perspective of the models, only 2 studies conducted both internal and external validation, 3 studies ultimately employed machine learning, while 11 studies utilized traditional modeling methods. However, we found that many studies faced issues such as insufficient sample sizes, missing crucial methodological information, and all models being rated as having a high risk of bias.

Conclusion:

Most published predictive models lack methodological rigor, leading to a heightened risk of bias. Future research should prioritize the enhancement of methodological rigor and the external validation of risk prediction models for extubation failure in ICU patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Additionally, it is essential to emphasize adherence to scientific methods and transparent reporting to improve the accuracy and generalizability of research findings.

Systematic review registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/recorddashboard, Registration number:CRD420251124371.

1 Introduction

The Intensive Care Unit (ICU) is a department that focuses on the centralized treatment of critically ill patients (1). Due to the critical condition of severely ill patients, their ability to maintain spontaneous breathing is significantly diminished. When patients exhibit respiratory insufficiency, there is a risk of hypoxia, or they may have already shown signs of hypoxia; thus, mechanical ventilation treatment becomes necessary (2). Mechanical ventilation (MV) is one of the standard life support technologies in the ICU, with approximately 50% of ICU patients requiring MV (3). However, prolonged mechanical ventilation can lead to complications in patients, including Ventilator Associated Pneumonia (VAP), (4) barotrauma (5), airway injuries (6), and catheter-associated pressure injuries (7). During the treatment period, as the patient’s condition improves and respiratory function gradually returns to normal, the demand for mechanical ventilation support stabilizes and begins to decrease. Considering discontinuing mechanical ventilation and proceeding with extubation as early as possible is necessary.

Extubation, the gradual withdrawal of mechanical ventilation support, is a critical process through which critically ill patients regain their ability to breathe spontaneously and are liberated from the ventilator (8). This phase is essential for patients transitioning out of the intensive care unit. Extubation failure is the patient’s inability to sustain spontaneous breathing following extubation from the ventilator. This condition necessitates reconnection to the ventilator or occurs when spontaneous breathing lasts less than 48 h without ventilator support, requiring interventions such as non-invasive ventilation, high-flow oxygen therapy, re-intubation, terminal extubation, or tracheostomy (9). The offline process consists of three steps: offline screening, procedures, and extubation (10). The expert group of the Critical Care Medicine Branch of the Chinese Medical Association emphasizes in the “Clinical Application Guidelines for Mechanical Ventilation” that when the causes of respiratory failure in ICU patients are effectively controlled or improved, we should conduct weaning therapy as early as possible to achieve optimal therapeutic effects and prognosis (11). Determining the optimal timing for withdrawing mechanical ventilation is crucial in treatment. An appropriate extubation moment prevents unnecessary medical resource consumption and helps alleviate the financial burden on patients’ families. Related research reports that 5–30% of ICU patients experience weaning failure (12). Inappropriately delaying weaning from mechanical ventilation may increase the risk of complications such as pneumonia or ventilator-associated lung injury in patients on mechanical ventilation (13). This risk leads to increased medical costs and prolonged hospital stays for patients and may significantly elevate the overall mortality risk (14). Although successful extubation is an important goal in ICU treatment, an overly aggressive weaning process may lead to inadequate oxygen supply, respiratory muscle fatigue, and incomplete recovery of airway protective functions, which may increase the risk of extubation failure (15). It is noteworthy that extubation failure is not the result of a single pathological process, but rather the consequence of the combined effects of abnormalities across multiple systems, including the respiratory system (e.g., respiratory muscle fatigue, airway secretion retention) (16), the cardiovascular system (e.g., left ventricular overload) (17), neuromuscular function (e.g., myasthenia) (18), and metabolic status (e.g., malnutrition, frailty) (19).

Therefore, the early identification of high-risk populations for mechanical ventilation weaning failure in the ICU, along with timely and effective interventions for their risk factors, is of significant importance in reducing the incidence of mechanical ventilation extubation failure among ICU patients and improving clinical outcomes. Risk prediction models use mathematical formulas to assess the existence of specific conditions or the future risk of certain events, effectively identifying risk factors for diseases and quantifying the magnitude of risk associated with each factor (20). Multiple countries have developed various risk prediction models for extubation failure in ICU patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. However, these different models’ predictive capabilities and clinical applicability remain unclear. Furthermore, no studies have been found that systematically evaluate these models. Therefore, this study aims to systematically evaluate the risk prediction models for extubation failure in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation in the ICU, with the intention of providing a basis for clinical medical staff to select or develop appropriate risk prediction models for extubation failure in ICU mechanical ventilation patients.

2 Materials and methods

This systematic review has been registered in PROSPERO (Registration ID: CRD420251124371).

2.1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

2.1.1 Study types

Cohort studies, case–control studies, and cross-sectional studies.

2.1.2 Research subjects

Patients aged ≥18 years requiring invasive mechanical ventilation in the ICU.

2.1.3 Research content

The construction and/or validation of a prediction model for extubation failure in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation in the Intensive Care Unit.

2.1.4 Exclusion criteria

① Non-Chinese or Non-English literature; ② Literature that only analyzes risk factors without establishing a risk prediction model; ③ Literature for which the original text cannot be obtained or data is incomplete; ④ Studies that have been published repeatedly; ⑤ Studies where the number of predictive variables included in the model is less than 2.

2.2 Literature retrieval strategy

A comprehensive search was conducted in various databases, including CNKI, Wanfang Data, China Biomedical Literature Database, VIP, PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, Cochrane Library, and CINAHL, regarding research on risk prediction models for extubation failure in patients on mechanical ventilation in the ICU. The search timeframe was from the establishment of the database until August 8, 2025. The search was restricted to English- and Chinese-language publications; no additional language filters were applied during the initial retrieval, but all non-English/non-Chinese articles were subsequently excluded in line with the pre-specified inclusion criteria. The search strategy combined both subject headings and free-text terms, focusing primarily on keywords such as “Intensive Care Units,” “ICU,” “Intubation, Intratracheal,” “Respiration, Artificial,” and “Risk Assessment.” This comprehensive approach ensures a thorough exploration of relevant literature in the context of critical care management. For the complete search strategy, please refer to Appendix A. Additionally, we employed the PICOTS framework recommended by the CHARMS checklist (21) for key evaluations and data extraction in systematic reviews to describe the key elements of this systematic review as follows. The detailed search strategy is provided in Appendix A.

P (Population, P): patients aged ≥18 years in the ICU receiving mechanical ventilation.

I (Intervention model, I): development and/or validation of a risk prediction model for extubation failure in ICU patients on mechanical ventilation.

C (Comparator, C): none. O (Outcome, O): The outcome is defined as extubation failure in patients on mechanical ventilation during their ICU stay.

T (Timing, T): before extubation in patients on mechanical ventilation in the ICU.

S (Setting, S): the intended use of this prediction model is for risk stratification in the ICU to assess the risk of extubation failure, thereby enabling timely preventive measures.

2.3 Literature screening and data extraction

Initially, two researchers (ZX and CXJ) independently screened the literature and extracted data based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. If necessary, a third reviewer (QXY) participated. The literature screening method involved using NoteExpress software to remove duplicate records, reading titles and abstracts for initial screening, excluding obviously irrelevant literature, and then further reading the full texts for secondary screening to determine the final included literature. Subsequently, standardized forms were developed for data extraction based on the Critical Appraisal and Data Extraction for Systematic Reviews of Prediction Modelling Studies (CHARMS) (21).

2.4 Assessment of bias risk in included studies

Two researchers employed the Prediction Model Risk of Bias Assessment Tool (PROBAST) (22) to evaluate the risk of bias and applicability of the models included in the literature.

2.4.1 Bias risk assessment

PROBAST comprises four domains: study population, predictors, outcomes, and analysis. Each question can be answered as “Yes,” “Probably Yes,” “Probably No,” “No,” or “No Information.” If any domain is rated as “No” or “Probably No,” that domain is considered high risk; only when all questions are answered as “Yes” or “Probably Yes” is the domain considered low risk. If all four domains are assessed as low risk, the overall risk of bias (ROB) is rated as “Low”; if one or more domains are rated as uncertain risk while the remaining domains are low risk, the overall risk is classified as “Unclear.” The applicability assessment is similar to the bias risk assessment but uses only the first three domains to determine the applicability of the prediction model. The first two researchers (ZX and CXJ) conducted the assessments independently, with the final judgment made by a third reviewer (QXY).

2.4.2 Applicability assessment

The applicability assessment encompasses three domains: the study subjects, the predictive factors, and the outcomes. The judgment process is similar to bias risk, where the overall applicability of the predictive model is rated as ‘low’, ‘high’, or ‘unclear’. The overall rating is deemed ‘low risk’ only when all domains are assessed as ‘low risk’. If one or more domains are rated as ‘high risk’, the applicability is classified as ‘high risk’. If a particular domain is rated as ‘unclear’, but all other domains are rated as ‘low risk’, the applicability is considered ‘unclear’.

3 Results

3.1 Literature screening process and results

A preliminary search yielded 15,467 relevant articles. After removing duplicates, 11,944 articles remained. A gradual screening process ultimately included 14 articles (23–36). The literature screening process and results are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Flowchart of the literature search, screening, and final included.

3.2 Basic characteristics of included studies and bias risk assessment results

Among the included literature are 8 studies from China (28, 30–36), 2 from the United States (26, 27), 1 from Brazil (25), 1 from Colombia (24), and 1 from France (23). Additionally, there is 1 multi-national collaborative study (29). In the past 5 years, 10 studies have been published (27–36). Among the 14 studies, 9 are retrospective studies (24, 27, 30–36), while 5 are prospective studies (23, 25, 26, 28, 29). The basic characteristics of the included literature are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

| Author (year) | Country | Study design | Participants | Sample size | Outcome indicators | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Totality | Case | |||||

| Godet et al. (2017) (23) | France | Prospective study | MV patients with craniocerebral injury in the ICU | 140 | 43 | Re-intubation within 48 h after extubation |

| Sará-Ochoa et al. (2017) (24) | Colombia | Retrospective study | MV patients in the ICU | 1,017 | 157 | Re-intubation within 48 h after extubation |

| Dos Reis et al. (2017) (25) | Brazil | Prospective study | MV patients with traumatic brain injury in the ICU | 311 | 43 | Re-intubation within 48 h after extubation |

| Hsieh et al. (2018) (26) | USA | Prospective study | MV patients in the ICU | 3,602 | 185 | Re-intubation or death within 72 h after extubation |

| Bansal et al. 2022 (27) | USA | Retrospective study | MV patients in the ICU | 6,161 | 746 | Re-intubation within 72 h after extubation |

| Zhao et al. (2021) (28) | China | Prospective study | MV patients in the ICU | 16,191 | 2,807 | Re-intubation within 48 h after extubation |

| Cinotti et al. (2022) (29) | Multiple countries | Prospective study | MV patients in the ICU | 1,512 | 231 | Extubation failure within 5 days |

| Wang et al. (2023) (30) | China | Retrospective study | MV patients in the ICU | 546 | 131 | Need for non-invasive or invasive ventilatory support, or death, within 48 h after extubation |

| Li (2023) (31) | China | Retrospective study | MV patients in the ICU | 548 | 230 | Re-intubation within 48 h after extubation |

| Yang et al. (2023) (32) | China | Retrospective study | MV patients in the NICU | 310 | 60 | Re-intubation within 48 h after extubation |

| Zhao et al. (2023) (33) | China | Retrospective study | MV patients in the ICU | 670 | 133 | Death within 48 h after extubation or inability to resume spontaneous breathing within 48 h after extubation. |

| Hu et al. (2024) (34) | China | Retrospective study | MV elderly severe-pneumonia patients in the ICU | 330 | 117 | Requirement for non-invasive or invasive ventilatory support, or death, within 48 h after extubation. |

| Xu et al. (2024) (35) | China | Retrospective study | MV patients in the ICU | 487 | 164 | Re-intubation within 48 h after extubation |

| Sun et al. (2025) (36) | China | Retrospective study | MV patients in the EICU | 138 | 11 | Re-intubation within 48 h after extubation |

The basic characteristics of the included studies.

3.3 Establishment of the models included

A total of 28 predictive models for the offline failure risk were reported in the studies included. The number of candidate predictive variables in each study ranged from 9 to 105. Regarding variable selection, 11 studies (23–27, 30–34, 36) employed univariate and multivariate analyses, 2 studies (28, 35) utilized recursive feature elimination, and 1 study (29) applied Lasso regression for variable selection. In the handling of continuous variables, 3 studies (32, 34, 36) converted continuous variables into categorical variables, while the remaining eleven studies (23–31, 33, 35) maintained the continuity of the continuous variables. In the area of missing data handling, 10 studies (25–27, 30–36) did not report the missing data and the methods used for handling it. 2 studies (28, 29) only reported the use of multiple imputation to supplement the missing data. However, it did not specify the exact number of missing data points. 1 study (23) directly deleted the missing data, while only 1 study (24) reported the missing data and the method of mean imputation employed. Regarding model establishment methods, 10 studies (23, 25, 27, 29–34, 36) utilized only Logistic Regression for modeling, while 1 study (26) employed Neural Networks for modeling. Another study (28) applied Machine Learning methods for modeling. Additionally, one study (35) utilized five methods: LR, RF, SVM, XG Boost, and Light GBM for modeling. 7 studies (23, 24, 26, 27, 29, 33, 35) conducted only internal validation, 2 studies (30, 36) performed only external validation, and 2 studies (28, 31) employed a combination of internal and external validation methods for evaluation. The remaining 3 studies (25, 32, 34) did not conduct either internal or external validation. 4 studies (23, 26, 32, 36) did not report the model calibration methods, while 10 studies (24, 25, 27–31, 33–35) provided calibration information, typically in the form of the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. See Tables 2–4.

Table 2

| Author (year) | Number of candidate variables | Variable selection method | Continuous variable handling | Missing data | Modeling approach | Model performance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data | Handling methods | Performance | Calibration method | |||||

| Godet et al. (2017) (23) | 9 | Univariate and multivariate stepwise regression | Retained in continuous form | 1,276 | Direct deletion | LR | A: 0.820 | — |

| Sará-Ochoa et al. (2017) (24) | 21 | Univariate and multivariate analysis | Retained in continuous form | 8 | Mean imputation | — | A: 0.689 | H–L test |

| Dos Reis et al. (2017) (25) | 17 | Univariate and multivariate analysis | Retained in continuous form | — | — | LR | A: 0.810 | H–L test |

| Hsieh et al. (2018) (26) | 37 | Univariate and multivariate analysis | Retained in continuous form | — | — | ANN | A: 0.850 | — |

| Bansal et al. 2022 (27) | 21 | Univariate and multivariate analysis | Retained in continuous form | — | — | LR | A: 0.720 | H–L test |

| B: 0.720 | ||||||||

| Zhao et al. (2021) (28) | 89 | Recursive feature elimination | Retained in continuous form | — | Multiple imputation | ML | A1: 0.774 | Calibration curve |

| A2: 0.779 | ||||||||

| A3: 0.819 | ||||||||

| A4: 0.829 | ||||||||

| A5: 0.830 | ||||||||

| A6: 0.835 | ||||||||

| A7: 0.821 | ||||||||

| A8: 0.802 | ||||||||

| A9: 0.780 | ||||||||

| A10: 0.765 | ||||||||

| A11: 0.722 | ||||||||

| B1: 0.714 | ||||||||

| B2: 0.743 | ||||||||

| B3: 0.688 | ||||||||

| B4: 0.770 | ||||||||

| B5: 0.771 | ||||||||

| B6: 0.803 | ||||||||

| B7: 0.717 | ||||||||

| B8: 0.700 | ||||||||

| B9: 0.713 | ||||||||

| B10: 0.712 | ||||||||

| B11: 0.736 | ||||||||

| Cinotti et al. (2022) (29) | 20 | Lasso regression | Retained in continuous form | — | Multiple imputation | LR | A: 0.790 | H–L test, calibration curve |

| B: 0.710 | ||||||||

| Wang et al. (2023) (30) | 29 | Univariate and multivariate analysis | Retained in continuous form | — | — | LR | A: 0.926 | H–L test |

| Li (2023) (31) | 105 | Univariate and multivariate analysis | Retained in continuous form | — | — | LR | A: 0.773 | H–L test, calibration curve |

| B: 0.738 | ||||||||

| Yang et al. (2023) (32) | 12 | Univariate and multivariate analysis | Converted into a categorical variable | — | — | LR | A: 0.722 | — |

| Zhao et al. (2023) (33) | 22 | Univariate and multivariate analysis | Retained in continuous form | — | — | LR | A: 0.870 | H–L test, calibration curve |

| B: 0.867 | ||||||||

| Hu et al. (2024) (34) | 18 | Univariate and multivariate analysis | Partially converted to categorical variables | — | — | LR | A: 0.970 | H-L test、Calibration curve |

| Xu et al. (2024) (35) | 34 | Recursive feature elimination | Retained in continuous form | — | — | LR, RF, SVM, XG Boost, Light GBM | A1: 0.766 | Calibration curve |

| A2:0.788 | ||||||||

| A3:0.805 | ||||||||

| A4:0.800 | ||||||||

| A5:0.799 | ||||||||

| Sun et al. (2025) (36) | 23 | Univariate and multivariate analysis | Converted into a categorical variable | — | — | LR | A: 0.821 | — |

Model construction methods and performance.

A, Model Development Group; B, Model Validation Group; LR, Logistic Regression; RF, Random Forest; ANN, Artificial Neural Network; ML, Machine Learning; DT, Decision; SVM, Support Vector Machine; XG Boost, eXtreme Gradient Boosting; Light GBM, Light Gradient Boosting Machine. H–L test, Hosmer–Lemeshow.

A1: Logistic Regression; A2: Support Vector Machine; A3: Random Forest; A4: eXtreme Gradient Boosting; A5: Light Gradient Boosting Machine; A6: Cat Boost; A7: Gradient Boosting Decision Tree; A8: AdaBoost; A9: Multi-Layer Perceptron; A10: K-Nearest Neighbor; A11: Naive Bayes; B1: Logistic Regression; B2: Support Vector Machine; B3: Random Forest; B4: eXtreme Gradient Boosting; B5: Light Gradient Boosting Machine; B6: Cat Boost; B7: Gradient Boosting Decision Tree; B8: AdaBoost; B9: Multi-Layer Perceptron; B10: K-Nearest Neighbor; B11: Naive Bayes. “—”: No mentioned.

Table 3

| Author (year) | Validation method | Model presentation format | Final predictors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal validation | External validation | |||

| Godet et al. (2017) (23) | Bootstrap resampling | — | Risk score | Cough response, swallowing ability, swallowing reflex, CRS visual score |

| Sará-Ochoa et al. (2017) (24) | Bootstrap resampling | — | Model equation | BUN, oxygenation index, APACHE II, cumulative fluid balance, hemoglobin |

| Dos Reis et al. (2017) (25) | — | — | Risk score | Duration of mechanical ventilation, female, GCS motor score, secretions, cough response |

| Hsieh et al. (2018) (26) | Random split validation, K-fold cross-validation | — | — | TISS score, hemodialysis, rsbi, pre-extubation heart rate, pre-extubation oxygenation index, MEP |

| Bansal et al. 2022 (27) | Random split validation | — | Risk score | Duration of mechanical ventilation, body mass index, Glasgow Coma Scale score, mean airway pressure at 1 min of spontaneous breathing trial, fluid balance in the 24 h before extubation |

| Zhao et al. (2021) (28) | Random split validation | Spatial validation | Web calculator | Age, body mass index, stroke, heart rate, respiratory rate, mean arterial pressure, oxygen saturation, temperature, pH, central venous pressure, tidal volume, positive end-expiratory pressure, mean airway pressure, Pressure support level in pressure support ventilation mode, duration of mechanical ventilation, number of successful spontaneous breathing trials, fluid balance in the 24 h before extubation, type of antibiotics |

| Cinotti et al. (2022) (29) | Random split validation | — | Risk score | TBI, strong cough, gag reflex, swallowing ability, endotracheal suction ≤2 times per hour, GCS motor score, temperature on the day of extubation |

| Wang et al. (2023) (30) | — | Temporal validation | Model equation | Duration of mechanical ventilation, diaphragmatic excursion, diaphragmatic thickness variation, RSBI, inferior vena cava variability |

| Li (2023) (31) | Bootstrap resampling | Temporal validation | Nomogram | Duration of mechanical ventilation, APACHE II score, ROX index, COPD, PaO2, hemoglobin |

| Yang et al. (2023) (32) | — | — | Model equation | Duration of mechanical ventilation, age, GCS score, smoking index, MODS, underlying respiratory disease |

| Zhao et al. (2023) (33) | Random split validation | — | Nomogram | Duration of mechanical ventilation, APACHE II score, SOFA score, PaCO2, ventilator-induced diaphragmatic dysfunction |

| Hu et al. (2024) (34) | — | — | Nomogram | Duration of mechanical ventilation, age, COPD, smoking, D-dimer, oxygenation index |

| Xu et al. (2024) (35) | Five-fold cross-validation | — | Model equation | APACHE II, respiratory rate during SBT, GCS score, hemoglobin |

Model validation and final predictors.

Table 4

| Predictive factor | Temporal attribute | Measurement method | Intervenability | Clinical significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of mechanical ventilation | Cumulative | Vital sign | No | Reflects the risk of respiratory muscle disuse atrophy |

| GCS score | Pre-extubation | Score | No | Related to the level of consciousness and airway protective capacity |

| APACHE II score | Pre-extubation | Score | No | Comprehensively assesses the severity of the disease |

| Age | Baseline | Demographic | No | Respiratory muscle reserve function declines with age |

| Hemoglobin | Pre-extubation | Lab | Yes | Oxygen delivery capacity affects respiratory muscle endurance |

| Respiratory rate | Pre-extubation | Vital Sign | Yes | Reflects the balance between respiratory drive and load |

| Serum albumin | Pre-extubation | Lab | Yes | Nutritional status is related to respiratory muscle protein synthesis |

Classification table of predictors.

3.4 Model performance and included predictive factors

Among the 14 studies included, the AUC values of the 28 models ranged from 0.688 to 0.970, with 26 models having an AUC greater than 0.7, indicating good predictive performance. Definitions of extubation failure and their time windows differed across studies; therefore AUCs are presented descriptively without quantitative synthesis, avoiding inflation of performance due to definitional heterogeneity. The final presentation formats of the models varied; 5 studies (24, 30, 32, 35, 36) presented the models in the form of equations, 4 studies (23, 25, 27, 29) utilized risk scores, 3 studies (31, 33, 34) presented the models as nomograms, and 1 study (26) did not specify the final presentation format of the model. The number of predictive factors included in the final models ranged from 4 to 17, with the top five most frequently occurring predictive factors being: mechanical ventilation duration, GCS score, APACHE II score, age, and hemoglobin. Predictive factors that appeared with a frequency of ≥2 times are shown in Figure 2, Tables 3–5

Figure 2

Results of the bias assessment of 14 studies.

Table 5

| Author (year) | Data source | AUC | Calibration accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zhao et al. (2021) (28) | Cardiac Surgical ICU of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University | 0.80 (0.74–0.83) | — |

| Wang et al. (2023) (30) | Department of Critical Care Medicine, Weifang People’s Hospital, Weifang, Shandong | 0.924 (0.886–0.961) | H-L (p = 0.629) |

| Li (2023) (31) | Department of Critical Care Medicine, First Hospital of Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, Gansu | 0.738 (0.630–0.846) | — |

| Sun et al. (2025) (36) | Department of Critical Care Medicine, Kaifeng Central Hospital, Kaifeng, Henan | — | — |

Model external validation performance.

H–L, Hosmer–Lemeshow test.

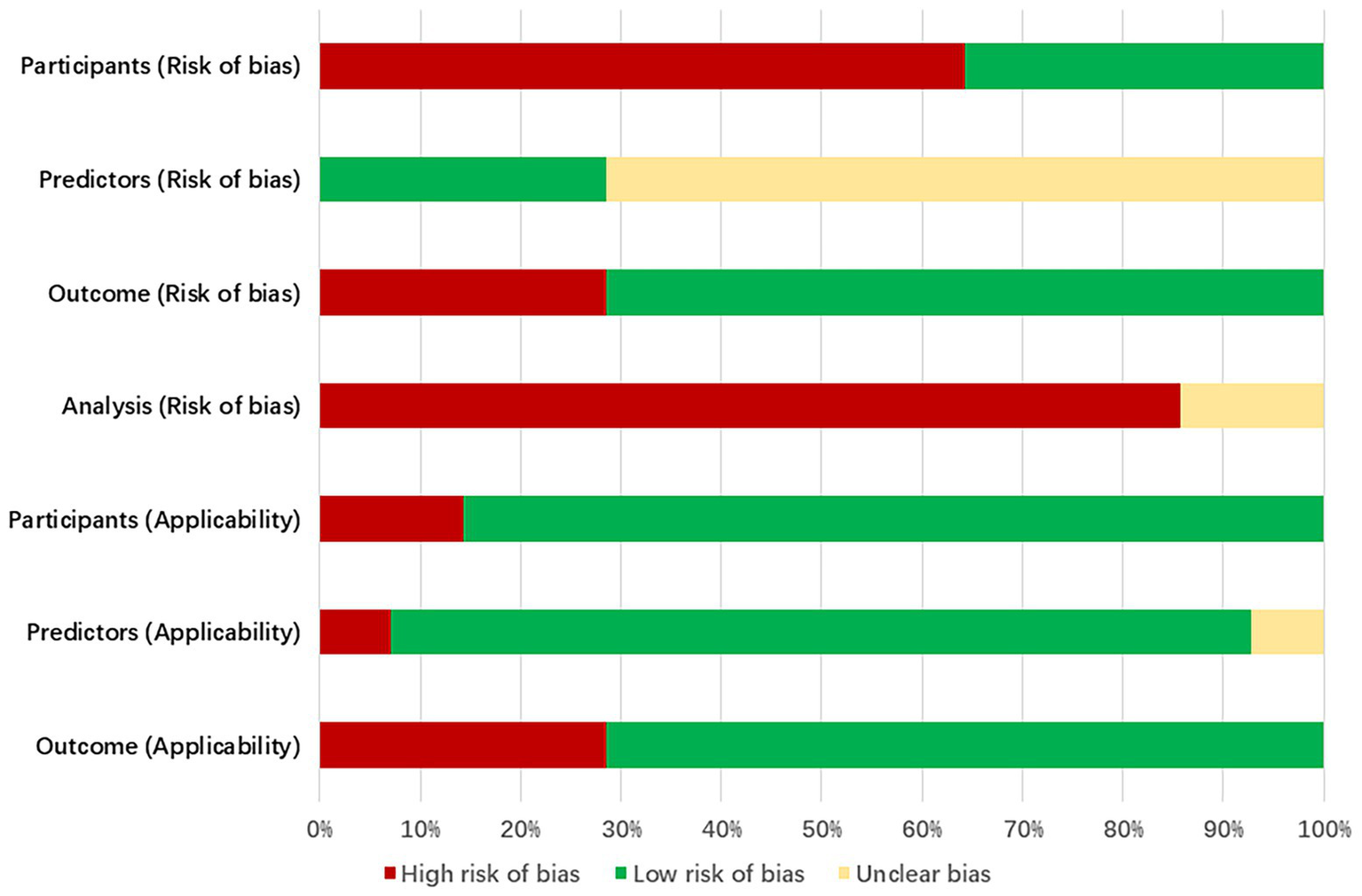

3.5 Assessment of bias risk and applicability

The bias assessment tool PROBAST was employed to evaluate the bias risk and applicability of the included literature. All studies were rated as having a high risk of bias, indicating methodological issues present in the development or validation process of the extubation failure models for ICU patients on mechanical ventilation. Specific results can be found in Figure 3, Table 6 and Appendix B.

Figure 3

Predictor frequency distribution.

Table 6

| Author (year) | ROB | Applicability | Overall | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | Predictors | Outcome | Analysis | Participants | Predictors | Outcome | ROB | Applicability | |

| Godet et al. (2017) (23) | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | − |

| Sará-Ochoa et al. (2017) (24) | − | ? | + | − | + | + | + | − | + |

| Dos Reis et al. (2017) (25) | + | ? | + | ? | + | + | + | − | − |

| Hsieh et al. (2018) (26) | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | + |

| Bansal et al. (2022) (27) | − | ? | − | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| Zhao et al. (2021) (28) | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + |

| Cinotti et al. (2022) (29) | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | + |

| Wang et al. (2023) (30) | − | ? | + | − | + | + | + | − | + |

| Li (2023) (31) | − | ? | + | ? | + | + | + | − | + |

| Yang et al. (2023) (32) | − | ? | + | − | + | ? | + | − | + |

| Zhao et al. (2023) (33) | − | ? | + | − | + | + | + | − | + |

| Hu et al. (2024) (34) | − | ? | + | − | − | + | + | − | − |

| Xu et al. (2024) (35) | − | ? | + | − | + | + | + | − | + |

| Sun et al. (2025) (36) | − | ? | − | − | − | + | − | − | + |

PROBAST results of the included studies.

PROBAST, Prediction Model Risk of Bias Assessment Tool; ROB, risk of bias; + indicates low ROB/low concern regarding applicability; − indicates high ROB/high concern regarding application;? indicates unclear ROB/unclear concern regarding applicability.

3.5.1 Bias in the field of study

9 studies (24, 27, 30–36) (64%, 9/14) exhibited a high risk of bias. This is attributed to the retrospective nature of the studies, which may introduce recall bias. Important predictive factors related to the failure of extubation from mechanical ventilation in ICU patients could not be obtained solely through the review of medical records.

3.5.2 Bias in predictive factor

Research 5 studies (23, 25, 26, 28, 29) (36%, 5/14) were assessed as having a low risk of bias in the predictive factor domain, while 9 studies (24, 27, 30–36) (64%, 9/14) were rated as unclear. The reason for this is that the 5 studies were prospective in nature, with the measurement of predictive factors conducted prior to the occurrence of outcomes, utilizing a blind method by default. The remaining 9 studies were retrospective, and it remains unclear whether the assessment of predictive factors was conducted without knowledge of the outcome data.

3.5.3 Bias in outcome domains

11 studies (23–25, 28, 30–36) (79%, 11/14) were rated as low risk in the predictor domain, while 3 studies (26, 27, 29) (21%, 3/14) were rated as high risk. This may be because ten studies not only utilized standardized guidelines but also had clear and consistent definitions of outcome indicators. The remaining three studies were rated high risk due to offline assessment of outcomes exceeding 48 h.

3.5.4 Analysis of bias in the field

Fourteen studies exhibited a high risk of bias in the analysis. The issues identified include: ① In 13 studies (23–27, 29–36), the number of outcome events was insufficient (EPV < 20); ② 3 studies (32, 34, 36) improperly transformed continuous variables into categorical variables, indicating an inappropriate variable handling method; ③ 10 studies (25–27, 30–36) did not report missing data and the methods for handling it; ④ 11 studies (23–27, 30–34, 36) selected predictive factors based on univariate analysis without employing appropriate variable selection methods; ⑤ 3 studies (25, 32, 34) did not perform internal or external validation of the models; ⑥ None of the 14 studies addressed the issue of model overfitting or underfitting.

3.5.5 Applicability assessment

11 studies (24, 26–33, 35, 36) demonstrated overall good applicability, while 3 studies (23, 25, 34) exhibited relatively low overall applicability. Among them, 2 studies (23, 25) were limited to mechanically ventilated patients with traumatic brain injuries in the ICU, and one study (34) focused on elderly patients with severe pneumonia.

4 Discussion

4.1 Quality of research on extubation failure risk prediction models is acceptable but contains certain biases

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of prediction models to identify the extubation failure risk in adult patients undergoing mechanical ventilation in the ICU. A total of 28 prediction models were included, with AUC values ranging from 0.688 to 0.970. Among these, 26 models exhibited an AUC greater than 0.7, indicating good predictive performance. The high risk of bias is primarily concentrated in the analytical domain, mainly due to insufficient outcome event numbers, improper handling of variables, the selection of predictive factors based on univariate analysis, failure to report missing data information, incomplete model performance evaluation, and lack of reporting on model fit.

4.1.1 Data sources

In terms of research type, this study includes 9 retrospective cohort studies (24, 27, 30–36). The predictive factors incorporated into the model may not be comprehensive, and there is a potential risk of data omission, which could lead to biased results. In prospective studies, the measurement of predictive factors occurs before the outcomes, effectively standardizing the assessment methods for these factors. This standardization significantly enhances the reliability of the model results. The PROBAST evaluation tool suggests that to mitigate the risk of overfitting in model development research, the number of outcome events should be at least 20 times the number of candidate predictors. This implies that the events per variable (EPV) should exceed 20. Given that the risk prediction model for extubation failure in ICU patients on mechanical ventilation includes numerous candidate predictors, it becomes challenging to satisfy the EPV > 20 criterion. Consequently, future model studies should include a sufficiently large sample size. Future research should prioritize the pre-selection of clinically significant and potentially predictive variables through methods such as clinical expertise, literature review, or univariate analysis before formal modeling. It is generally advised that the final model include no more than 10 to 15 predictor variables, ensuring that the events per variable (EPV) ratio approaches or exceeds 20. This approach serves to mitigate the risk of overfitting.

4.1.2 Data analysis

① In the handling of continuous variables, Collins et al. (37) point out that when constructing risk prediction models, converting continuous variables into two or more categorical variables can increase the risk of the model. Among the studies included in this research, 3 studies (32, 34, 36) converted continuous variables into categorical variables, which may lead to a higher risk of bias in the included studies. Future studies should retain continuous predictors in their original form or model them with flexible functions such as restricted cubic splines; this preserves information, avoids arbitrary cut-point bias, and improves both discrimination and calibration. Owing to substantial heterogeneity in data sources, candidate predictor sets, and modelling methods across studies, we could not directly compare AUCs or calibration between models that kept variables continuous and those that converted them to categories. Future work should use a single dataset and an identical modelling pipeline to test both approaches and thereby quantify their true effects on discrimination and calibration. ② In the realm of missing data handling, 12 studies (25–36) did not report any missing data, whereas 1 study (23) explicitly excluded subjects with missing data, which indicates inadequate handling of this issue. Such an approach may result in the loss of valuable hidden information within the excluded subjects, potentially leading to bias in the model. Missing data can significantly impact the quality of data analysis and the accuracy of models, making the preprocessing of missing data particularly important. The PROBAST guidelines suggest that missing values should not be deleted directly; instead, multiple imputation should be employed (38). Multiple imputation methods can effectively reduce the adverse effects of missing data on statistical analysis and model stability, thereby improving research accuracy and reliability (39). Future researchers should provide a comprehensive account of missing values and the methods employed to handle them during the model construction process. It is recommended that multiple imputation techniques be utilized to address these missing values effectively. ③ Selection of Predictors in this study, the predictors were primarily identified through univariate analysis to find statistically significant variables, followed by Logistic Regression analysis to incorporate these significant variables into the model. This method of screening predictors can reduce the workload but may overlook important risk factors. Therefore, it is recommended that future research utilize stepwise regression to mitigate multicollinearity issues effectively. LASSO regression, which employs the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator, can perform parameter estimation and variable selection simultaneously. ④ In terms of model validation, only 2 studies (28, 31) conducted internal and external validation, while 7 studies (23, 24, 26, 27, 29, 33, 35) performed only internal validation (Bootstrap resampling and random grouping validation) 0.2 studies (30, 36) conducted only external validation, and three studies (25, 32, 34) did not perform either internal or external validation. Therefore, future researchers may choose high-quality predictive models for external validation for the risk of extubation failure in ICU patients on mechanical ventilation based on the results of this study.

Despite the high risk of bias associated with all studies, which somewhat limits the clinical application of the models, valuable insights can still be gained from the recommendation processes of the models. Cinotti et al. (29) conducted a prospective multicenter study involving 1,512 neurocritical patients across 73 intensive care units (ICUs) in 18 countries, effectively mirroring clinical decision-making scenarios. The authors utilized LASSO regression for the data-driven automatic selection of candidate variables and employed ten-fold cross-validation to identify independent predictive factors. This approach effectively addresses multicollinearity issues while maintaining the model’s simplicity and robustness, establishing a strong foundation for subsequent extrapolation applications in diverse medical environments. Zhao et al. (28) conducted a study utilizing the MIMIC-IV database, which comprised a training set of 16,189 patients, and performed an independent prospective validation with 502 patients from the cardiac surgery ICU at Zhongshan Hospital, affiliated with Fudan University. This methodology effectively balanced sample size and generalizability, mitigating the overfitting risk. The CatBoost algorithm inherently accommodates missing values and categorical variables, eliminating the necessity for additional imputation and dummy variable encoding. The study ultimately retained only 17 readily obtainable bedside indicators by integrating a SHAP-based recursive feature elimination strategy. The internal validation set achieved an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.835. In contrast, the external validation set reached an AUROC of 0.803, significantly surpassing traditional scoring systems such as the RSBI and SOFA (p < 0.01). Furthermore, the research team developed a plug-and-play web-based prediction tool that outputs risk probabilities in real-time based on input variables, thereby providing a visual and generalizable digital foundation for clinical extubation decisions.

4.2 Predictive factors for extubation failure

Variations and commonalities arise due to differences in research types and the variables included, leading to inconsistencies in the predictive factors identified across various studies. Nonetheless, this study identifies commonalities among the predictive factors recognized in different research efforts. Specifically, this research explores five risk predictive factors that frequently appear: duration of mechanical ventilation, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, APACHE II score, age, and hemoglobin levels. Prolonged mechanical ventilation can result in diaphragmatic disuse atrophy and decreased contractile function. Research indicates that diaphragmatic dysfunction occurs in up to 37% of long-term mechanical ventilation patients and is significantly associated with weaning failure (40, 41). Prolonged mechanical ventilation can lead to ICU-acquired muscle weakness, which decreases the contractile strength of respiratory muscles, including the diaphragm and accessory respiratory muscles. This muscle weakness significantly increases the risk of weaning failure by a factor ranging from 2.64 to 19.07 (42). Prolonged mechanical ventilation increases the risk of complications, including ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) and barotrauma, which may further exacerbate respiratory function impairment (43).

The APACHE II scoring system is used to assess the severity of illness and mortality risk in ICU patients. A higher score indicates a more severe condition and an increased risk of death. A higher APACHE II score indicates more severe systemic physiological disturbances and organ failure, which can directly increase the risk of offline failure through multiple pathways. Patients with elevated scores frequently experience severe hypoxemia, acidosis, hemodynamic instability, and multiple organ dysfunction, resulting in an imbalance between respiratory work and oxygen consumption (44). The severe inflammatory response, malnutrition, and accelerated muscle protein breakdown lead to a synchronous decline in the strength of the diaphragm and peripheral muscles (45). A high APACHE II score frequently suggests the necessity for deep sedation, larger doses of vasopressors, or continuous renal replacement therapy (46). These interventions can suppress the respiratory drive of the central nervous system, thereby delaying the recovery of consciousness and re-establishing airway protective reflexes. Consequently, this may lead to a significant reduction in the success rate of spontaneous breathing trials and an increased likelihood of re-intubation and mortality in the ICU (47).

Vidotto et al. (48) found that when the patient’s GCS is less than 8, the extubation success rate drops sharply to 33%, indicating that the level of consciousness is a key threshold variable in predicting weaning outcomes. The degree of consciousness impairment is linearly negatively correlated with the integrity of airway protection and respiratory drive. As the GCS score decreases, the cough reflex arc is inhibited, and the sensitivity of the respiratory center to hypercapnia and hypoxemia significantly diminishes. Consequently, patients struggle to maintain adequate tidal volume and rhythmic stability during spontaneous breathing trials, which leads to an extension of mechanical ventilation duration and an exponential increase in the risk of extubation failure (49). A decrease in the GCS score may also be accompanied by dysfunction in other organ systems, such as an increase in the SOFA score, further complicating the weaning process (50). Therefore, healthcare professionals should enhance airway management for patients with altered consciousness based on the GCS score and proactively implement targeted interventions to reduce weaning difficulties.

As individuals age, their bodily functions gradually decline. With increasing age, a person’s respiratory reserve diminishes, leading to a heightened risk of decompensation. As age increases, there is a reduction in type II muscle fibers in the diaphragm, accompanied by mitochondrial dysfunction. This results in an exponential decline in the endurance and strength of the respiratory muscles, leading to a higher likelihood of diaphragm fatigue during spontaneous breathing tests. Consequently, this triggers instability in central-ventilatory coupling (51). Immunosenescence and chronic low-grade inflammation significantly increase the susceptibility of elderly patients to volume overload, ventilator-associated diaphragm dysfunction, and nosocomial infections, triggering a systemic inflammatory response syndrome and delaying diaphragm repair (52). Elderly patients frequently demonstrate a decline in cardiac functional reserve, pulmonary vascular remodeling due to arteriosclerosis, and neurodegenerative disorders. These comorbidities further exacerbate the adverse effects of aging on the extubation outcomes of ICU patients receiving mechanical ventilation by diminishing cardiopulmonary coupling efficiency, extubation respiratory drive, and impairing central integration capabilities (53).

Hemoglobin, a crucial carrier of oxygen in the bloodstream, exhibits abnormal levels that significantly impact the extubation outcomes of patients undergoing mechanical ventilation in the ICU. In a state of low hemoglobin, the oxygen supply capability of tissues in patients decreases, leading to impaired respiratory muscle function, affecting respiratory drive and endurance (54). Relevant research indicates that a decrease in hemoglobin concentration directly reduces arterial blood oxygen content, leading to a hypoxic state in peripheral tissues and respiratory muscles. This hypoxia not only diminishes the contractile ability of the respiratory muscles but may also extend the duration of mechanical ventilation required for patients (55). Conversely, elevated hemoglobin levels adversely affect pulmonary blood circulation by increasing blood viscosity. This increase in blood viscosity results in heightened microcirculatory resistance, consequently diminishing the adequate perfusion of lung tissue and further impairing gas exchange efficiency (56). Additionally, elevated hemoglobin levels may promote the formation of microthrombi, thereby exacerbating pulmonary vascular resistance and potentially leading to offline failure.

5 Limitations

Although this study provides a comprehensive summary of the prediction models for extubation failure in ICU patients on mechanical ventilation, certain limitations persist. Firstly, this study exclusively included retrievable literature in both Chinese and English, which may introduce publication bias. Secondly, the imposed English/Chinese language restriction could have omitted relevant studies published in other languages, potentially limiting the generalisability of our findings. Thirdly, due to variations in inclusion criteria and study designs across different studies, only a qualitative analysis of the research results was conducted, precluding a quantitative analysis. This review could not standardise the original definitions; a consensus core outcome (e.g., re-intubation within 48 h) with broader criteria analysed separately in sensitivity analyses should be adopted in future work.

6 Conclusion

This paper comprehensively evaluates predictive models for extubation failure in patients undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation in the ICU. The findings suggest that current models are susceptible to bias due to several methodological flaws identified during the model development process, and some models lack external validation. To enhance the quality of future research, the research team should adhere to the PROBAST and TRIPOD guidelines for model construction, design, and reporting processes. Additionally, validating existing models across various regions will improve the external generalizability of risk prediction models. The research community should prioritise independent replication of the remaining models rather than creating new ones, so as to consolidate the evidence base before widespread implementation.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

XZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PL: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. JC: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. ZC: Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. XQ: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1695394/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Rajsic S Breitkopf R Bachler M Treml B . Diagnostic modalities in critical care: point-of-care approach. Diagnostics. (2021) 11:2202. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11122202

2.

Pham T Brochard LJ Slutsky AS . Mechanical ventilation: state of the art. Mayo Clin Proc. (2017) 92:1382–400. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.05.004

3.

Tadesse EE Tilahun AD Yesuf NN Nimani TD Mekuria TA . Mortality and its associated factors among mechanically ventilated adult patients in the intensive care units of referral hospitals in Northwest Amhara, Ethiopia, 2023. Front Med. (2024) 11:1345468. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1345468

4.

Hraiech S Ladjal K Guervilly C Hyvernat H Papazian L Forel JM et al . Lung abscess following ventilator-associated pneumonia during COVID-19: a retrospective multicenter cohort study. Crit Care. (2023) 27:385. doi: 10.1186/s13054-023-04660-x

5.

Hagan R Gillan CJ Spence I McAuley D Shyamsundar M . Comparing regression and neural network techniques for personalized predictive analytics to promote lung protective ventilation in intensive care units. Comput Biol Med. (2020) 126:104030. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.104030

6.

Kangas-Dick A Gazivoda V Ibrahim M Sun A Shaw JP Brichkov I et al . Clinical characteristics and outcome of pneumomediastinum in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. (2021) 31:273–8. doi: 10.1089/lap.2020.0692

7.

Choi BK Kim MS Kim SH . Risk prediction models for the development of oral-mucosal pressure injuries in intubated patients in intensive care units: a prospective observational study. J Tissue Viability. (2020) 29:252–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jtv.2020.06.002

8.

Jia Y Kaul C Lawton T Murray-Smith R Habli I . Prediction of weaning from mechanical ventilation using convolutional neural networks. Artif Intell Med. (2021) 117:102087. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2021.102087

9.

Le Neindre A Philippart F Luperto M Wormser J Morel-Sapene J Aho SL et al . Diagnostic accuracy of diaphragm ultrasound to predict weaning outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. (2021) 117:103890. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103890

10.

Schönhofer B Geiseler J Dellweg D Fuchs H Moerer O Weber-Carstens S et al . Prolonged weaning: S2k guideline published by the german respiratory society. Respiration. (2020) 99:982–1084. doi: 10.1159/000510085

11.

Chinese Society of Critical Care Medicine . Guidelines for clinical application of mechanical ventilation (2006). Chin Crit Care Med. (2007) 19:65–72. doi: 10.3760/j.issn:1003-0603.2007.02.002

12.

Baptistella AR Mantelli LM Matte L Carvalho MEDRU Fortunatti JA Costa IZ et al . Prediction of extubation outcome in mechanically ventilated patients: development and validation of the extubation predictive score (ExPreS). PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0248868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248868

13.

Taran S Angriman F Pinto R Ferreyro BL Amaral ACK-B . Discordances between factors associated with withholding extubation and extubation failure after a successful spontaneous breathing trial*. Crit Care Med. (2021) 49:2080–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005107

14.

Van Hollebeke M Ribeiro Campos D Muller J Gosselink R Langer D Hermans G . Occurrence rate and outcomes of weaning groups according to a refined weaning classification: a retrospective observational study*. Crit Care Med. (2023) 51:594–605. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005814

15.

Pham T Heunks L Bellani G Madotto F Aragao I Beduneau G et al . Weaning from mechanical ventilation in intensive care units across 50 countries (WEAN SAFE): a multicentre, prospective, observational cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. (2023) 11:465–76. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00449-0

16.

Dres M Rozenberg E Morawiec E Mayaux J Delemazure J Similowski T et al . Diaphragm dysfunction, lung aeration loss and weaning-induced pulmonary oedema in difficult-to-wean patients. Ann Intensive Care. (2021) 11:99. doi: 10.1186/s13613-021-00886-6

17.

Sanfilippo F Di Falco D Noto A Santonocito C Morelli A Bignami E et al . Association of weaning failure from mechanical ventilation with transthoracic echocardiography parameters: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. (2021) 126:319–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.07.059

18.

Khazaei O Laffey CM Sheerin R McNicholas BA Pham T Heunks L et al . Impact of comorbidities on management and outcomes of patients weaning from invasive mechanical ventilation: insights from the WEAN SAFE study. Crit Care. (2025) 29:114. doi: 10.1186/s13054-025-05341-7

19.

Laffey CM Sheerin R Khazaei O McNicholas BA Pham T Heunks L et al . Impact of frailty and older age on weaning from invasive ventilation: a secondary analysis of the WEAN SAFE study. Ann Intensive Care. (2025) 15:13. doi: 10.1186/s13613-025-01435-1

20.

Collins GS Dhiman P Ma J Schlussel MM Archer L Van Calster B et al . Evaluation of clinical prediction models (part 1): from development to external validation. BMJ. (2024) 384:e074819. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2023-074819

21.

Moons KGM De Groot JAH Bouwmeester W Vergouwe Y Mallett S Altman DG et al . Critical appraisal and data extraction for systematic reviews of prediction modelling studies: the CHARMS checklist. PLoS Med. (2014) 11:e1001744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001744

22.

Wolff RF Moons KGM Riley RD Whiting PF Westwood M Collins GS et al . PROBAST: a tool to assess the risk of bias and applicability of prediction model studies. Ann Intern Med. (2019) 170:51–8. doi: 10.7326/M18-1376

23.

Godet T Chabanne R Marin J Kauffmann S Futier E Pereira B et al . Extubation failure in brain-injured patients: risk factors and development of a prediction score in a preliminary prospective cohort study. Anesthesiology. (2017) 126:104–14. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001379

24.

Sará-Ochoa JE Hernández Ortíz OH Jaimes FA . Development of a predictive model for extubation failure in weaning from mechanical ventilation: a retrospective cohort study. Trends Anaesth Crit Care. (2017) 17:21–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tacc.2017.10.060

25.

Dos Reis HFC Gomes-Neto M Almeida MLO Da Silva MF Guedes LBA Martinez BP et al . Development of a risk score to predict extubation failure in patients with traumatic brain injury. J Crit Care. (2017) 42:218–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.07.051

26.

Hsieh M-H Hsieh M-J Chen C-M Hsieh C-C Chao C-M Lai C-C . An artificial neural network model for predicting successful Extubation in intensive care units. J Clin Med. (2018) 7:240. doi: 10.3390/jcm7090240

27.

Bansal V Smischney NJ Kashyap R Li Z Marquez A Diedrich DA et al . Reintubation summation calculation: a predictive score for extubation failure in critically ill patients. Front Med. (2022) 8:789440. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.789440

28.

Zhao Q-Y Wang H Luo J-C Luo M-H Liu L-P Yu S-J et al . Development and validation of a machine-learning model for prediction of extubation failure in intensive care units. Front Med. (2021) 8:676343. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.676343

29.

Cinotti R Mijangos JC Pelosi P Haenggi M Gurjar M Schultz MJ et al . Extubation in neurocritical care patients: the ENIO international prospective study. Intensive Care Med. (2022) 48:1539–50. doi: 10.1007/s00134-022-06825-8

30.

Wang JH Sun SQ Zhang XD Yang XX Wang YJ Lu JB et al . Construction of a weaning risk prediction model for mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU. J Shandong Univ Health Sci. (2023) 61:86–93. doi: 10.3760/j.issn:1003-0603.2007.02.002

31.

Li W. R. . Construction and validation of a re-intubation risk prediction model for mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU (master’s thesis). Lanzhou: Lanzhou University (2023). p. 76

32.

Yang XW Tong ZR Wu J Wang Y . Development of a predictive model for weaning failure in mechanically ventilated neurosurgical critically ill patients. Mil Nurs. (2023) 40:9–12. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2097-1826.2023.06.003

33.

Zhao WT Zhou DW Yang XM Zheng HY . Development and validation of a nomogram model for predicting weaning failure in critically ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. J Pract Cardiovasc Pulm Dis. (2023) 31:59–65. doi: 10.12114/j.issn.1008-5971.2023.00.141

34.

Hu MM Liu L Zhang SQ . Development and validation of a risk prediction model for weaning failure in elderly patients with severe pneumonia receiving mechanical ventilation. Chin J Respir Crit Care Med. (2024) 23:321–6. doi: 10.7507/1671-6205.202310039

35.

Xu H Ma Y Zhuang Y Zheng Y Du Z Zhou X . Machine learning-based risk prediction model construction of difficult weaning in ICU patients with mechanical ventilation. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:20875. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-71548-3

36.

Sun X Liu DX Wei ZJ Zhai HR Li YJ Luo SP . Analysis of risk factors and development of a prediction model for extubation failure in mechanically ventilated patients with severe pneumonia. J Intern Emerg Crit Care Med. (2025) 31:65–8. doi: 10.11768/nkjwzzzz20250112

37.

Collins GS Reitsma JB Altman DG Moons KGM . Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. Ann Intern Med. (2015) 162:55–63. doi: 10.7326/M14-0697

38.

Moons KGM Wolff RF Riley RD Whiting PF Westwood M Collins GS et al . PROBAST: a tool to assess risk of bias and applicability of prediction model studies: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. (2019) 170:W1–W33. doi: 10.7326/M18-1377

39.

Heymans MW Twisk JWR . Handling missing data in clinical research. J Clin Epidemiol. (2022) 151:185–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.08.016

40.

Dres M De Abreu MG Merdji H Müller-Redetzky H Dellweg D Randerath WJ et al . Randomized clinical study of temporary transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation in difficult-to-wean patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2022) 205:1169–78. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202107-1709OC

41.

Virolle S Duceau B Morawiec E Fossé Q Nierat M-C Parfait M et al . Contribution and evolution of respiratory muscles function in weaning outcome of ventilator-dependent patients. Crit Care. (2024) 28:421. doi: 10.1186/s13054-024-05172-y

42.

Menis AA Tsolaki V Papadonta ME Vazgiourakis V Zakynthinos E Makris D . A study on the diagnostic accuracy of tidal volume-diaphragmatic contraction velocity: a novel index for weaning outcome prediction. Crit Care Med. (2025) 53:e1214–23. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000006660

43.

Tashiro N Hasegawa T Nishiwaki H Ikeda T Noma H Levack W et al . Clinical utility of diaphragmatic ultrasonography for mechanical ventilator weaning in adults: a study protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Sci Rep. (2023) 6:e1378. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.1378

44.

Rodríguez Villamizar P Thille AW Márquez Doblas M Frat J-P Leal Sanz P Alonso E et al . Best clinical model predicting extubation failure: a diagnostic accuracy post hoc analysis. Intensive Care Med. (2025) 51:106–14. doi: 10.1007/s00134-024-07758-0

45.

Matejovic M Huet O Dams K Elke G Vaquerizo Alonso C Csomos A et al . Medical nutrition therapy and clinical outcomes in critically ill adults: a European multinational, prospective observational cohort study (EuroPN). Crit Care. (2022) 26:143. doi: 10.1186/s13054-022-03997-z

46.

Hernández G Paredes I Moran F Buj M Colinas L Rodríguez ML et al . Effect of postextubation noninvasive ventilation with active humidification vs high-flow nasal cannula on reintubation in patients at very high risk for extubation failure: a randomized trial. Intensive Care Med. (2022) 48:1751–9. doi: 10.1007/s00134-022-06919-3

47.

Zarrabian B Wunsch H Stelfox HT Iwashyna TJ Gershengorn HB . Liberation from invasive mechanical ventilation with continued receipt of vasopressor infusions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2022) 205:1053–63. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202108-2004OC

48.

Vidotto MC Sogame LCM Calciolari CC Nascimento OA Jardim JR . The prediction of extubation success of postoperative neurosurgical patients using frequency–tidal volume ratios. Neurocrit Care. (2008) 9:83–9. doi: 10.1007/s12028-008-9059-x

49.

Da Silva AR Novais MCM Neto MG Correia HF . Predictors of extubation failure in neurocritical patients: a systematic review. Aust Crit Care. (2023) 36:285–91. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2021.11.005

50.

Zhang Z Tang W Ren Y Zhao Y You J Wang H et al . Prediction of ventilator weaning failure in postoperative cardiac surgery patients using vasoactive-ventilation-renal score and nomogram analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. (2024) 11:1364211. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2024.1364211

51.

Yayan J Schiffner R . Weaning failure in elderly patients: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Clin Med. (2024) 13:6429. doi: 10.3390/jcm13216429

52.

Ajoolabady A Pratico D Tang D Zhou S Franceschi C Ren J . Immunosenescence and inflammaging: mechanisms and role in diseases. Ageing Res Rev. (2024) 101:102540. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2024.102540

53.

Michels-Zetsche JD Röser E Ersöz H Neetz B Dahlhoff JC Joves B et al . Influence of age on outcomes in prolonged weaning from mechanical ventilation. BMJ Open Respir Res. (2025) 12:e002730. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2024-002730

54.

Oknińska M Mackiewicz U Zajda K Kieda C Mączewski M . New potential treatment for cardiovascular disease through modulation of hemoglobin oxygen binding curve: myo-inositol trispyrophosphate (ITPP), from cancer to cardiovascular disease. Biomed Pharmacother. (2022) 154:113544. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113544

55.

Megaritis D Wagner PD Vogiatzis I . Ergogenic value of oxygen supplementation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Intern Emerg Med. (2022) 17:1277–86. doi: 10.1007/s11739-022-03037-2

56.

Raberin A Burtscher J Connes P Millet GP . Hypoxia and hemorheological properties in older individuals. Ageing Res Rev. (2022) 79:101650. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2022.101650

Summary

Keywords

Intensive Care Unit, mechanical ventilation, extubation failure, risk prediction model, systematic review

Citation

Zeng X, Chen XJ, Lai P, Chen J, Chen Z and Qi X (2025) Risk prediction models for extubation failure in critically ill patients on mechanical ventilation: a systematic review. Front. Med. 12:1695394. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1695394

Received

29 August 2025

Accepted

28 October 2025

Published

20 November 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Luigi Vetrugno, Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Friuli Centrale, Italy

Reviewed by

Luh Karunia Wahyuni, RSUPN Dr. Cipto Mangunkusumo, Indonesia

Wei Jun Dan Ong, National University Health System (Singapore), Singapore

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Zeng, Chen, Lai, Chen, Chen and Qi.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiyu Qi, 3901088462@qq.com

‡These authors share first authorship

† Present address: Xiyu Qi, Nursing Department, Chongqing JiangJin District Hospital of Chinese Medicine, Chongqing, China

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.