Abstract

Bioadhesives have emerged as a promising alternative to conventional sutures, offering rapid and robust tissue integration while overcoming limitations such as time-consuming procedures and risks of secondary tissue damage. However, the bonding strength and degradation kinetics of most existing adhesives remain difficult to precisely control, limiting their adaptability to diverse tissue types and clinical scenarios. In this context, smart responsive bioadhesives have attracted significant attention due to their tunable adhesion properties, on-demand detachment capability, and tissue-matching mechanical properties. These materials can respond to biological environmental stimuli, enabling dynamic interactions with biological systems and opening new avenues for applications in wearable devices, controlled drug delivery, tissue repair, and smart bioelectronic interfaces. Nevertheless, a systematic review summarizing the synthesis strategies, adhesion mechanisms, and application prospects of such advanced adhesives remains lacking. Herein, we comprehensively analyzes the design strategies, working principles, and biomedical applications of smart responsive adhesives over the past decade. Furthermore, we discuss current limitations and propose future directions aimed at accelerating the translation of smart responsive adhesives from laboratory research to clinical practice. This review aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of these materials and offer valuable insights for researchers engaged in developing advanced tissue adhesives for practical applications.

1 Introduction

Adhesion is ubiquitous in nature. Octopuses and mussels anchor themselves to rocks, and remora fishes attach to other marine creatures, and geckos cling to walls (1–3). Inspired by these natural adhesion phenomenon, human beings have created various adhesives that can be applied to practical scenarios. The earliest adhesives in history could date back to the early days of humanity when people used water and clays to simply bind objects together. However, such adhesion methods were difficult to achieve long-lasting and strong bonding effects (4). As human society developed, more and more adhesives were gradually invented and began to gain recognition in human history. In particular, the discovery of polymer materials pushed the development of synthetic adhesives to a new height (5). These adhesives are now widely used in medicine, aerospace, machinery and other manufacturing industries.

For medical applications, compared to traditional techniques, medical tissue adhesives can achieve faster and more convenient tissue suturing and fixation (6). Additionally, due to their ease of use, tissue adhesives require less technical expertise from operators (7). Currently, medical tissue adhesives used in clinical practice are divided into natural adhesives and synthetic adhesives (8). Natural tissue adhesives cause less inflammation and foreign body reactions with higher biocompatibility, while they fail to achieve an ideal adhesion effect. Generally, natural adhesives can be divided into fibrin adhesives, gelatin-based adhesives, albumin-based adhesives, and polysaccharide-based adhesives (9). However, natural adhesives weaken with moisture and heat, exhibit inconsistent quality, and have limited bonding strength. These shortcomings drive the shift to synthetic alternatives, which offer superior durability, water resistance, and reliable performance in diverse conditions. In contrast, synthetic adhesives can provide strong and durable bonding effects, but their poor biocompatibility leads to severe inflammation and rejection reactions (10, 11). And synthetic tissue adhesives can be divided into polycyanoacrylate (PCA)-based adhesives, polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based adhesives, and polyurethane (PU)-based adhesives (10, 12).

Despite significant progress in the development of tissue adhesives, there are still some drawbacks that cannot be ignored. (1) The adhesion strength of adhesives is uncontrollable (13, 14). Although the adhesion strength of some tissue adhesives can ensure their bonding effect, the fault tolerance is low, resulting in secondary damage and bleeding to newly formed tissue during the detachment process, which has negative impacts on the ideal healing of the wound (15). (2) The adhesives do not match the elastic modulus of various of tissues (16). Tissue adhesives should ensure the normal physiological functions of tissues when bonding tissues, otherwise it will cause adverse consequences to organs and the human body itself, such as pulsation of the heart and blood vessels, and flexible movement at joints, respiratory function in the lungs (17). (3) The degradation rate of adhesives does not match the rate of tissue regeneration, making it difficult for granulation tissues to grow into damaged tissues and prolonging tissue healing and exposure time (18, 19). Wounds are more susceptible to get bacteria contamination and scar healing. Therefore, smart responsive tissue adhesives with advantages such as good biocompatibility, controllable adhesive strength, and a better match between degradation rate and tissue regeneration rate have been proposed (19, 20).

The development of highly biocompatible smart responsive tissue adhesives that allow for on-demand and non-invasive detachment has gradually become a current research focus. This review aims to introduce the reversible adhesion mechanisms of various smart responsive tissue adhesives, as well as the research progress and hotspots in biomedical applications.

2 Reversible adhesion mechanism

Reversibility is a prominent advantage of smart responsive tissue adhesives, implying that the adhesive strength can be controlled for on-demand detachment (21). According to adhesion mechanisms, they can be categorized into four main types, namely thermally responsive (22–24), chemically responsive (25, 26), mechanically responsive (27) and other reversible mechanisms (28–30) (Figure 1). This section introduces the reversible adhesion mechanisms of the different types of smart responsive tissue adhesives (Figure 2) and their minimal and maximal adhesion strength are listed in Tables 1–4, respectively.

FIGURE 1

Schematic diagram of reversible adhesion mechanisms of smart responsive tissue adhesives.

FIGURE 2

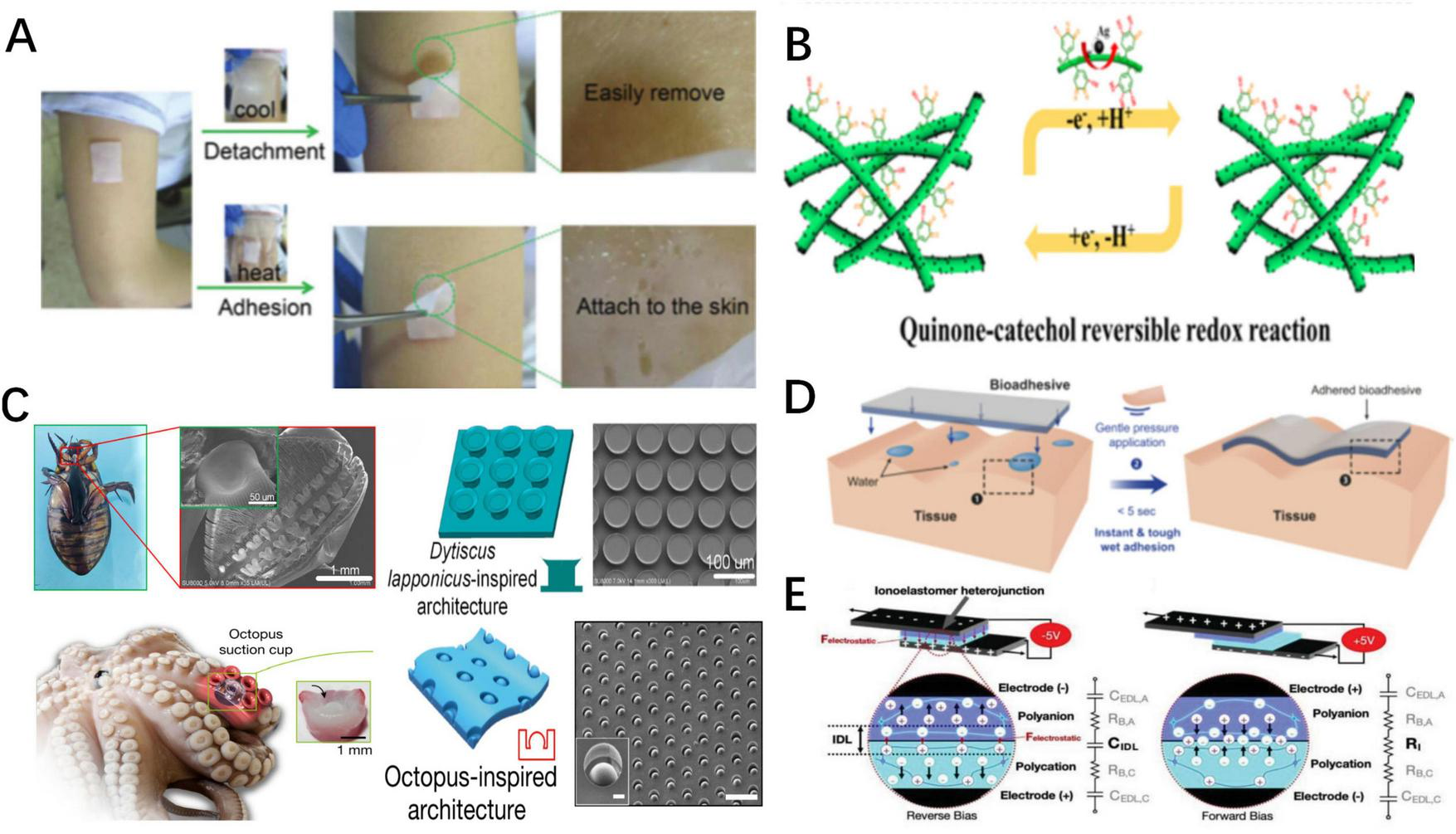

Schematic representation of various of responsive adhesives. (A). Schematic representation of thermally responsive adhesion (38). (B) Schematic representation of dynamic balance between chemical functional groups of chemically responsive adhesion (111). As the balance is broke, the adhesion states change. (C) Schematic depiction of constructions of Dytiscus lapponicus-inspired adhesion structure (DIAS) and octopus-inspired architectures (OIAs) (65, 66). (D) Schematic representation of water-assist adhesion (57). (E) Schematic representation of and electro-adhesion (124).

TABLE 1

| Reversible adhesion mechanism | Adhesives | Substrate | Testing method | Adhesion | Response time | Peeling | Durability | Rupture strain | Biocompatibility | Application | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum | Minimum | |||||||||||

| Thermally response adhesives | Hydrogen bond | Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-Clay-polydopamine nanoparticles/poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-Clay bilayer hydrogel (NC-PDA/NC (34)) | Dry porcine skin | Tensile adhesion test | 4.83 kpa (Room Temperature) | ∼0 kpa (37 °C) | / | Without any residue | Remains 4.8 Kpa after 3 cycles of cyclic peel-off tests | 850% | NIH-3T3 | Wearable electronic devices |

| Dynamic multiscale contact synergy hydrogel adhesive (DMCS) (35) | Dry glass/Wood | / | ∼21 kpa/32 kpa (10–20 °C) | ∼0.4 kpa/0.13 kpa (60 °C) | 0.4 s | / | Reversibly switched about 50 times | Stretch to more than 7 times its original length | / | Intelligent robotics | ||

| Poly(3,4-dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine)-adamantine -methoxyethyl acrylate-poly(N-iso-propylacrylamide-β-cyclodextrin (pDOPA-AD-MEA -pNIPAM-CD) (36) | Wet silicon substrate | Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) | ∼23 nN (40 °C) | 2.2 nN (25 °C) | / | / | Maintains a strong adhesion strength after 50 cycles | / | / | Intelligent robotics | ||

| Octopus-inspired hydrogel adhesive (OHA) (37) | Dry porcine skin | / | ∼0.3 mN (25 °C) | ∼0.1 mN (45 °C) | / | Without secondary damage | Maintain highly robust adhesion after 1,000 attachment/detachment cycles | / | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells(HUVECs) | Target drug delivery system | ||

| Chitosan–Catechol–poly (N-isopropyl acrylamide) (Chitosan–Catechol–pNIPAM) (38) | Dry Human arm | 90° peeling test | 0.038 N (40 °C) | ∼0.0039 N (20 °C) | With NIR Laser for 30 s | Without any residue | / | / | Rabbit knee chondrocytes | Hemostatic adhesive materials | ||

| 2-(dimethylamino) ethyl metharcylate and N-isopropylacrylamide (DMAEMA/NIPAM) (39) | Dry glass | Peeling test | 317.8 J/m2 (37 °C) | / | / | / | 10 repeated peel tests | Stretching to 200% strain | / | Artificial skin sensing system | ||

| Gelatin-sodium alginate- Tris/protocatechualdehyde/ferric chloride (GT-SA-TPF) (40) | Dry porcine skin | Lap shear test | 38 kPa (37 °C) | 11 kpa (25 °C) | few minutes | Peeled easily | Recover to original value after 5 temperature cycles | / | Murine fibroblast (L 929)/Rat | Acute wound dressings | ||

| Quaternized chitosan-polyacrylic acid hydrogel (QAAH) (44) | Dry porcine skin | lap-shear adhesion | 37.4 kpa (37 °C) | 6.8 kpa (20 °C) | several seconds | Easy to detach | / | / | HUVECs | Artificial skin sensing system | ||

| Quaternized chitosan@poly(1-vinyl-3-butyl imidazolium bromide)-co-methacryloyloxyethyl trimethylammonium chloride QCS/[BVIm][Br]/DMC (43) | Porcine skin/Glass | Tension-shear test | 26.45 kpa/33.70 kPa (20 °C) | / | / | Easily removed | Remains above 71%/96% of the original after the cycles for 10 times | / | L929/Hemolysis performance | Multiple function wound dressing | ||

| Polymerizing acrylamide (AM) monomer -polyethylenimine (PEI) -Glycerol-Ionic hybrid hydrogel (45) | Iron sheet | Tensile adhesion test | 1.1 Mka (−40 °C) | 102 Kpa (20 °C) | Do not attenuate for at least 5 cycles. | More than 300 times of its initial length | / | wearable electronic devices | ||||

| Dynamic metal-ligand bonds | Cu2+-curcumin-imidazole-polyurethane hydrogel adhesives (CIPUs: Cu2+) (48) | Aluminum sheet | Tensile adhesion test | 2.46 Mpa (RT) | / | Exposed to the NIR light for 30 s | Loss of adhesion ability | CIPUs:Cu2 + can largely maintain after multiple repeated sticking/peeling operations | Maximum value of the tensile strength is 2.05 MPa | / | / | |

| Melting/crystallization | 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide crystal fiber ([EMIM]Br) (50) | Glass | Lap-shear test | 3.47 kpa (20 °C) | 0.016 kpa (60 °C) | Exposed to the NIR light (1 W) for 15 s | Without residue | remained the stable 3.31 ± 0.32 MPa after 10 cycles | / | Bioelectronics | ||

Summary of reversible adhesion mechanism, maximal and minimal adhesion strength and biomedical applications of thermally responsive tissue adhesives.

TABLE 2

| Reversible adhesion mechanism | Adhesives | Substrate | Trigger | Testing method | Adhesion | Response time | Peeling | Durability | Rupture strain | Biocompatibility | Application | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum | Minimum | ||||||||||||

| Chemically response adhesives | Catechol-metal bonds | Caffeic acid modified gelatin oxidized dextran-ZnO (CaGOD/ZnO) (54) | Porcine skin | Medical metal-chelating agent, ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) | Lap shear test | 26.9 kpa | 4.3 kpa | / | Easily removed | / | Withstand the gravity of 100 g | NIH-3T3/hemolysis ratio | Multifunctional wound dressings |

| Quaternized chitosan-ferric iron (protocatechualdehyde)3 QCS-PA@Fe (53) | Porcine skin | Medical metal-chelating agent, Deferoxamine mesylate (DFO) | Lap shear tests | 10.4 kpa | 1.3 kpa | / | Without secondary injury of the wound. | / | / | L929/mice | Multifunctional wound dressings | ||

| Poly(acrylic acid-co-3-((8,11,13)-pentadeca-trienyl) benzene-1,2-diol –chitosan P(AA-co-UCAT)-CS (74) | Porcine skin | Metal solution (Fe3 +)/pH 8.0 aq. solution | 180-degree peeling test | 1664 J/m2 | 300 J/m2/752.4 J/m 2 | / | Complete detachment | Maintains adhesion strength of 180 kPa after 20 adhering-peeling cycles | Highly stretchable (1,300–2,600%) | L929 | Artificial skin sensors and wearable devices | ||

| Disulfide bond | Aldehyde cellulose polyethylenimine -acrylic acid-3-sulfonic acid propyl methyl acrylic acid potassium - caffeic acid/polyethylene glycol diacrylate- carboxylated cellulose - acrylic acid CNC-CHO-PEI- AA- MASEP- CA/PEGDA- CNC-COOH- AA (CPAMC/PCA) (56) | Wet porcine myocardium tissue | Oxidized glutathione | Lap-shear tests | 223.14 kpa | / | / | Quickly separate and remove | More than 30 cycles of attachment/detachmen | Did not get rupture after compressing to 60% strain | Cardiomyocytes | Multifunctional cardiac patch | |

| Polyvinyl alcohol-poly(acrylic acid) -N-hydroxysuccinimide (PVA-PAA-NHS) (57) | Wet por- cine skin | Solution consisting of sodium bicarbonate (SBC) and glutathione (GSH) | 180° peel test | 400J/m2 | / | 5 minutes | Nearly complete detachment | / | / | Sprague–Dawley rats | Removable implantable devices | ||

| Hydrogen bonds | Tannin–europium coordination complex -citrate-based mussel-inspired bio-adhesives (TE-CMBA) (61) | Wet porcine skin | Borax solution | Lap shear strength tests | 38.5 kpa | / | 1.5–15 min | Leaving nearly no residue | Fully restored after four cycles. | The tensile strengths were > 400 kPa | HUVECs/L929 cells | Diabetic wound dressings | |

| Polyethylene glycol diacrylate/tannic acid (PEGDA/TA hydrogels) (62) | Underwater p orcine skin | Dimethyl-sulfoxide (DMSO) or urea | Tensile pull-off test | 158.4 kpa | <5 kpa | 15 s | / | 20 cycles of adhesion tests | fracture energy:17.9 ± 2.1 kJ/m2 | NIH-3T3/Sprague Dawley rats | Multifunctional wound dressings | ||

| PEDOT: PSS @poly(vinyl alcohol)/poly(acrylic acid) (PEDOT: PSS PVA/PAA) (98) | Porcine skin | / | Lap shear test | 15.9 kPa | / | Remained almost the same over 20 cycles | 6 times of its original length | / | Wearable soft electronic devices | ||||

| Functional groups balance | Phenylboronic acid/Zn-CuO@ Graphite oxide nanosheets biofoam adhesive (PBA/Zn-CuO@GO) (63) | Human skin | Hydroxy-rich glucose solutions | / | Effectively attach | Dissociate and detachment | / | Easily removed | / | / | Human lung cancer cells (A549) | Multifunctional wound dressings | |

| Ag/Tannic acid -Cellulose nanofibers (Ag/TA-CNF) (111) | Porcine skin | / | Tensile adhesion tests | 36.2 kPa | / | / | Without residual and damage | 20 adhering peeling cycles | Maximum fracture energy of 2200 J/m2 | L929 cells | Target drug delivery system | ||

Summary of reversible adhesion mechanism, maximal and minimal adhesion strength and biomedical applications of chemically responsive adhesives.

TABLE 3

| Reversible adhesion mechanisms | Adhesive | Substrate | Trigger | Testing method | Adhesion | Response time | Peeling | Durability | Rupture strain | Biocompatibility | Application | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum | Minimum | ||||||||||||

| Mechanically Responsive Adhesion | Peeling-off force | D. lapponicus-inspired adhesion structure (DIAS) (65) | Dry/underwater glass dry/underwater porcine skin | Peeling-off force | Lap shear test | 205/133 kpa ∼14 kpa/∼2 kpa | / | / | No residue | 60 repeating cycles | / | / | Electronic skin-attachable devices |

| Octopus-inspired architectures (OIAs) (66) | Wet/underwater/oil Silicon sheet on porcine skin | Peeling-off force | Adhesion Tester, Neo-Plus | 37/41/154 kPa ∼25 kPa; | / | / | / | / | / | / | Applied over skin or wounds | ||

| Soft-rigid hybrid smart artificial muscle (SRH-SAM) (67) | Dry glass | Peeling-off force | Custom-made apparatus | 1.65N | 0.88 N | / | / | / | Maximum contraction strain of 40% | / | Artificial muscles of soft grippers. | ||

| Shear force | Alginate and polyacrylamide- N-fluorenylmethoxy-carbonyl-L-tryptophan (Alg/PAM-FT) (68) | Human skin | Peeling-off force | 180° peel test | 72 J/m2 | 20 J/m2 | / | No residue | / | / | / | Pharmaceutical and electronic adhesives | |

Summary of reversible adhesion mechanism, maximal and minimal adhesion strength and biomedical applications of mechanically responsive tissue adhesives.

TABLE 4

| Reversible adhesion mechanism | Adhesives | Substrate | Trigger | Testing method | Adhesion | Response time | Peeling | Durability | Rupture strain | Biocompatibility | Application | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum | Minimum | ||||||||||||

| Other Stimuli-responsive adhesion | Water-assisted reversible adhesion | Polyvinyl alcohol/boric acids film (PVA/BA) (71) | Glass/transcutane | Water | Transcutaneous tensile test | 570 N/cm2 | 49 N/cm2 | 30 s/dissolved in water for 2 hours | Easily peeled off | Adhesive strength increased back to 330 N/cm2 again | (> 200% strain | / | Wound dressing adhesives |

| Polyvinyl alcohol/borax/oligomeric procyanidin hydrogels (PBO) (72) | Porcine skin | Lap shear test | 29.2 kpa | / | 10 min | Rapidly degrade | / | Highest storage modulus (G’): 3722.1 Pa | L929/mice | Smart hemostatic material | |||

| Poly (acrylic acid-co-acrylamide) [poly (AA-co-AM)] (101) | Porcine skin | Shear adhesion tests | 61.7 ka | / | / | Discharged automatically | Fibro-blast cells (FBs)/HUVECs | Skin flap transplantation | |||||

| Electroadhesion | Quaternized dimethyl aminoethyl methacrylate gel (QDM gel) (76) | Bovine tissue | Lap-shear test | 20 kpa | / | / | Be peeled off intact | / | Same as the adhesion strength | Multifunctional wound dressings | |||

Summary of reversible adhesion mechanism, maximal and minimal adhesion strength and biomedical applications other stimuli responsive tissue adhesives.

2.1 Thermally responsive adhesion

Thermally responsive adhesives are the most common type, which are synthesized by mixing thermal-sensitive materials with adhesive materials (31). In such adhesives, the temperature is controlled to alter the state of chemical bonds or the adhesion state, thereby modulating the adhesive strength (22).

Reversible hydrogen bonds formed by thermosensitive materials and water molecules confer thermally responsive characteristics. Poly(N-isopropyl acrylamide) (pNIPAM) is an ideal thermosensitive material whose amide groups form hydrogen bonds with water molecules, increasing the hydrophilicity of adhesives at low temperatures. These hydrogen bonds break at high temperatures, turning the adhesives hydrophobic (32, 33). Based on the above mechanism, adhesives containing pNIPAM achieve temperature-controlled adhesion through four mechanisms. (1) Temperature-Controlled Exposure of Adhesive Functional Groups: Di and Zhang et al. developed pNIPAM-Clay-polydopamine nanoparticles/pNIPAM-Clay (NC-PDA/NC) bilayer hydrogel adhesives and dynamic multiscale contact synergy (DMCS) hydrogel adhesives, respectively (34, 35). At room temperature, the pNIPAM inside the adhesives becomes hydrophilic, increasing the exposure of hydrophobic adhesive groups, thereby leading to enhanced adhesion. As the temperature rises, the hydrogen bonds break, resulting in reduced exposure of the adhesive functional groups, leading to decreased adhesive strength. Conversely, Zhao et al. synthesized a wet adhesive composed of guest copolymer 3,4-dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine (DOPA)-polymer-adamantine (AD)-methoxyethyl acrylate (MEA) and host copolymer pNIPAM-β-cyclodextrin (pNIPAM-CD), which absorbs water and swells at low temperatures (36). This effectively restricts the hydrophilic adhesive groups, thereby lowering the adhesive strength. As the temperature rises, the adhesive strength is enhanced due to the increased exposure of adhesive groups. (2) Temperature-Controlled Effective Bonding Area: Lee et al. designed an octopus-inspired hydrogel adhesive (OHA) that absorbs water and swells at low temperatures, thus increasing the effective bonding area and adhesion strength (37). As the temperature rises, the adhesive area decreases, leading to reduced adhesive strength. (3) Temperature-Controlled Sol-Gel State Change: Xu et al. prepared a Chitosan-Catechol-pNIPAM adhesive that absorbs water and remains in a sol state at low temperatures, exhibiting low friction and adhesive strength. However, the adhesive dehydrates and gels at high temperatures, increasing the friction and adhesion strength (38). (4) Temperature controlled effective bonding force strength. Sun et al. proposed the 2-(Dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate/PNIPAM hydrogel (PDMAEMA/PNIPAM), which forms electrostatic complexations with tissues to achieve adhesion (39). However, at low temperatures, the electrostatic complexations fail and the adhesive can be removed easily.

Other thermosensitive materials can also be used to confer thermally responsive properties through hydrogen bonds. Using the temperature phase transition characteristic of gelatin (GT), Liang et al. synthesized a thermally responsive GT-sodium alginate (SA)-TPF (a compound composed of Tris, PA, and Fe3+) hydrogel adhesive, named GT-SA-TPF (40–42). In this case, GT-related hydrogen bonds break at high temperatures, decreasing the cohesiveness of the adhesive and increasing the exposure of adhesive groups and adhesion. At low temperatures, the exposure of adhesive groups decreases, leading to decreased adhesion. Hydrogen bonds formed by ionic liquids (ILs) within the adhesives’ networks break at high temperatures, promoting hydrophobic interactions and increasing adhesive strength, whereas the adhesive strength decreases at lower temperatures. Zhang et al. created an IL-based hydrogel adhesive, quaternized chitosan (QCS)@poly(ILs)-co-methacryloyloxyethyl trimethylammonium chloride, QCS@P(IL-co-DMC), with temperature-controlled adhesion (43). Additionally, polyacrylic acid (PAA) releases a large number of carboxyl groups upon heating, which interact with other groups to form hydrogen bonds, thereby increasing adhesive strength. Shi and Wu utilized this mechanism to design QCS-polyacrylic acid hydrogel (QAAH), where the adhesion mechanism weakens or even disappears in low-temperature environments, enabling reversible adhesion (44). Yan et al. designed a low-temperature resistant glycerol-ionic hybrid hydrogel with reversible adhesion (45). At low temperatures, the hydrogen bonds, interface interactions, and tensile strength simultaneously increase and collaboratively enhance the adhesive strength. Therefore, the adhesive strength at −40°C is significantly higher than that at room or higher temperatures.

Moreover, dynamic metal-ligand bonds also provide thermally responsive properties to adhesives (46, 47). Xu et al. introduced Cu ions to prepare Cu2+-curcumin-imidazole-polyurethane hydrogel adhesives (CIPUs: Cu2+), which achieve high adhesion by interacting with tissues through Cu-ligand bonds (48). The metal-ligand bonds break under near infrared (NIR) assisted photothermal effects, resulting in reduced adhesion; however, the metal-ligand bonds reform at room temperature, restoring the adhesion.

Furthermore, thermally-responsive adhesives can achieve reversible adhesion through physical mechanisms (2, 49). Xi et al. developed a 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide ([EMIM]Br) crystal fiber-reinforced polymer gel, EBrH-GEL, based on crystal melting/crystallization mechanisms (50). The crystals within the EBrH-GEL melt at high temperatures and adhere to the substrates tightly, which then in situ crystallize at low temperatures, anchoring to the tissues and forming strong adhesion.

In summary, temperature changes can dynamically control the adhesion strength of thermally responsive adhesives through various mechanisms, including phase transitions, reversible hydrogen bonding, and metal coordination bonding.

2.2 Chemically responsive adhesion

Chemically responsive adhesives achieve controllable adhesive strength by disrupting the chemical bonds within adhesives or between adhesives and tissues. These chemical bonds mainly include catechol-metal bonds, redox-sensitive disulfide bonds, and hydrogen bonds (51).

Introducing catechol-metal bonds into adhesives can enhance their adhesion (52) Cheng et al. and Liang et al. developed hydrogel adhesives with strong tissue adhesion. One is composed of caffeic acid-modified gelatin (CaG), oxidized dextran (ODex), and ZnO (referred to as CaGOD/ZnO), and contains catechol-Zn bonds; the other is composed of quaternized chitosan-Ferri iron (protocatechualdehyde)3 (PA@Fe) (QCS-PA@Fe), containing catechol-Fe bonds (53, 54). Medical metal chelators, such as: ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) and deferoxamine mesylate (DFO), can disrupt these catechol-metal bonds to reduce their adhesive strength. Ultimately, chemically responsive adhesives can be removed by minimally invasive methods.

In addition, disulfide bonds can be disrupted by redox reactions (55). Researchers have introduced disulfide bonds into adhesives in various ways to prepare redox-responsive adhesives. He et al. introduced disulfide bonds through crosslinkers to create a CPAMC/PCA Janus hydrogel (56). Chen and Yu et al. prepared polyvinyl alcohol-poly(acrylic acid)-N-hydroxysuccinimide (PVA-PAA-NHS) by forming disulfide bonds through the reaction of -NHS ester and PAA (57). These adhesives can adhere tightly to various tissues but can also be easily removed with glutathione, which disrupts the disulfide bonds in adhesives (58).

Reversible hydrogen bonds formed between catechol groups and tissues could be replaced by interference from other groups (59). Fu et al. designed tannin–europium coordination complex crosslinked citrate-based mussel-inspired bio-adhesives (TE-CMBA), in which the catechol-hydrogen bonds were replaced by boric acid ester bonds after treatment with borax solutions, making the adhesives soluble and removable (60, 61). Similarly, Chen produced polyethylene glycol diacrylate/tannic acid (PEGDA/TA) hydrogels in which the catechol-hydrogen bonds were replaced after treatment with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or urea, resulting in reduced adhesion (62). Upon tissue healing, the adhesive can be on-demand removed by adding DMSO or urea to prevent secondary damage during separation.

Some chemically responsive adhesives maintain adhesion by sustaining a dynamic balance between functional groups, such as the phenylboronic acid (PBA)/Zn-CuO@GO nanosheet biofoam adhesive (PBA/Zn-CuO@GO) developed by Liu et al. (63). The adhesive takes advantage of the dynamic balance of phenylboronic acid/cis-diol interactions to sustain its adhesive property. When the balance is disrupted by competitive inhibitors (hydroxy-rich glucose solution), the adhesive strength decreases, leading to dissolution and detachment (64).

Chemically responsive adhesives typically achieve controlled debonding by introducing easily breakable chemical bonds in the cross-linked network. When these chemical bonds are broken, the cross-linking network collapses, and the adhesive becomes inactive and detached.

2.3 Mechanically responsive adhesion

As opposed to the aforementioned adhesive mechanisms, mechanical adhesives do not rely on environmental changes or additional reagents. Instead, they leverage the unique properties of materials or structures to achieve reversible adhesion (27).

Inspired by natural adhesive structures, researchers have developed bio-inspired adhesives that can be detached using peeling forces. Li et al. created a Dytiscus lapponicus-inspired adhesion structure (DIAS) that mimics the adhesive setae of Dytiscus lapponicus and can be removed with peeling force (65). Furthermore, the octopus-inspired architectures (OIAs) designed by Baik et al. are also structural adhesives relying on peeling force for detachment (66). These adhere to tissues through suction generated by structural deformations, which are easily broken by peeling force.

Zhao and Tian et al. designed a soft gripper consisting of an adhesive film and artificial muscles, soft-rigid hybrid smart artificial muscle. In the absence of electricity, the muscles remain relaxed and the adhesive film layer generates high adhesion strength through van der Waals forces and capillary forces. However, when the gripper is electrified and the artificial muscles contract, the edges of the film deform and break the adhesion mechanism, resulting in the detachment of the adhesive (67).

N-Fluorenylmethoxy-carbonyl-L-tryptophan (FT) is prone to disassembly under shear force. Wang et al. incorporated FT into the hydrogel network of alginate (Alg) and polyacrylamide (PAM) to synthesize the Alg/PAM-FT hydrogel (68). The networks within the hydrogel break under external shear forces, and the adhesion fails.

The mechanical force-responsive adhesives can achieve debonding without external stimulation or causing additional damage to adjacent tissues and objects. This capability demonstrates potential for practical applications and clinical translation.

2.4 Other stimuli-responsive adhesions

In addition, researchers have proposed other types of responsive adhesives, such as water-assisted adhesives active by moisture, and electrically responsive adhesives triggered by specific current directions; both represent good innovations.

Water-assisted reversible adhesion mechanisms include two types. (1) Water-dissociable chemical bonds, such as boronic ester bonds: When water-assisted reversible adhesives contact with a small amount of water, the boronic ester bonds within adhesives dissociate partially and rebond with tissues (69, 70). When immersed in excess water, the bonds in adhesives completely break, reducing the adhesion. Both the polyvinyl alcohol/boric acids (PVA/BA) film reported by Chen et al. and the PBA/borax/oligomeric procyanidin (OPC) hydrogels (PBO) reported by He et al. contain reversible boronic ester bonds and exhibit the above-mentioned reversible adhesion (71, 72). (2) The second mechanism employs water absorption to adjust the amount of effective adhesive bonds and the contact area (73). Using acrylic acid (AA) and acrylamide (AM), Zhou et al. designed poly(AA-co-AM) hydrogel adhesive, which wrinkles and softens when absorbing moisture from wet tissue to increase the effective adhesive area and the amount of hydrogen bonds, thereby enhancing adhesion. When exposed to excess water, wrinkles flatten or even disappear, lowering the adhesion (74).

Furthermore, electro-adhesion represents another reversible adhesion mechanism, in which two substances with opposite electrodes adhere directionally under the effects of electricity (75). The exact mechanism remains unclear but may result from molecular rearrangement under the influence of electrical fields (76). Broden et al. designed a positively charged quaternized dimethyl aminoethyl methacrylate gel (QDM) that can generate an adhesion strength of 25 kPa on bovine aorta when a specific directional current is applied. Reversing the electric field immediately reduces the adhesion strength to 5 kPa, allowing for rapid, non-invasive detachment (76).

In a word, the smart responsive mechanisms mentioned above are currently the focus of research, and the smart responsive adhesives mentioned above can effectively achieve reversible adhesion effects. Their relevant information can be seen in Tables 1–4, and parts of smart responsive tissue adhesives’ minimal and maximal adhesion strength are shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3

![Bar chart comparing the adhesion strength of various smart responsive tissue adhesives, measured in kilopascals (kPa) and megapascals (MPa). Adhesives range from CIPUs: Cu2+ with the highest adhesion strength at 2.61 MPa to [EMIM]Br with the lowest at 1.2 kPa. Data points are labeled along each bar indicating specific adhesion strengths for different adhesives.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1696667/xml-images/fmed-12-1696667-g003.webp)

Part of smart responsive tissue adhesives’ minimal and maximal adhesion strength.

3 Biomedical applications of smart responsive tissue adhesives

Cyanoacrylates (e.g., Epiglu®, Dermabond®) and fibrin sealants are clinically approved and extensively utilized, showing superior efficacy compared to traditional suturing in multiple clinical trials, however, they lack smart responsiveness. Consequently, the development of intelligent adhesives with controllable adhesion properties holds significant clinical potential. To achieve reversible adhesion, non-invasive detachment, and residue-free removal, smart responsive tissue adhesives have been increasingly studied in the biomedical fields. Currently, the primary applications of smart responsive tissue adhesives include tissue adhesives (9), artificial skin sensors (77), and drug delivery systems (78). This section briefly introduces the research progress in these biomedical fields (Figures 4, 5).

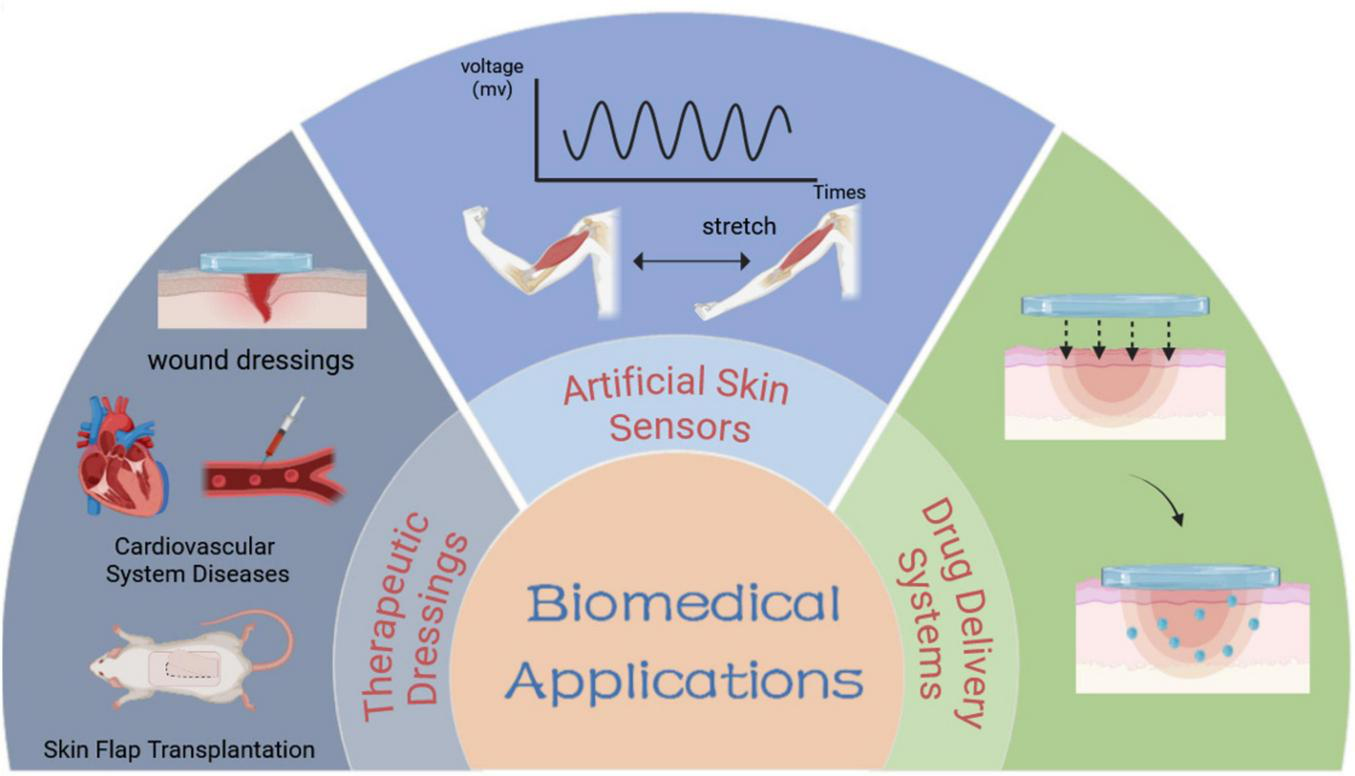

FIGURE 4

Schematic diagram of biomedical applications of smart responsive tissue adhesives.

FIGURE 5

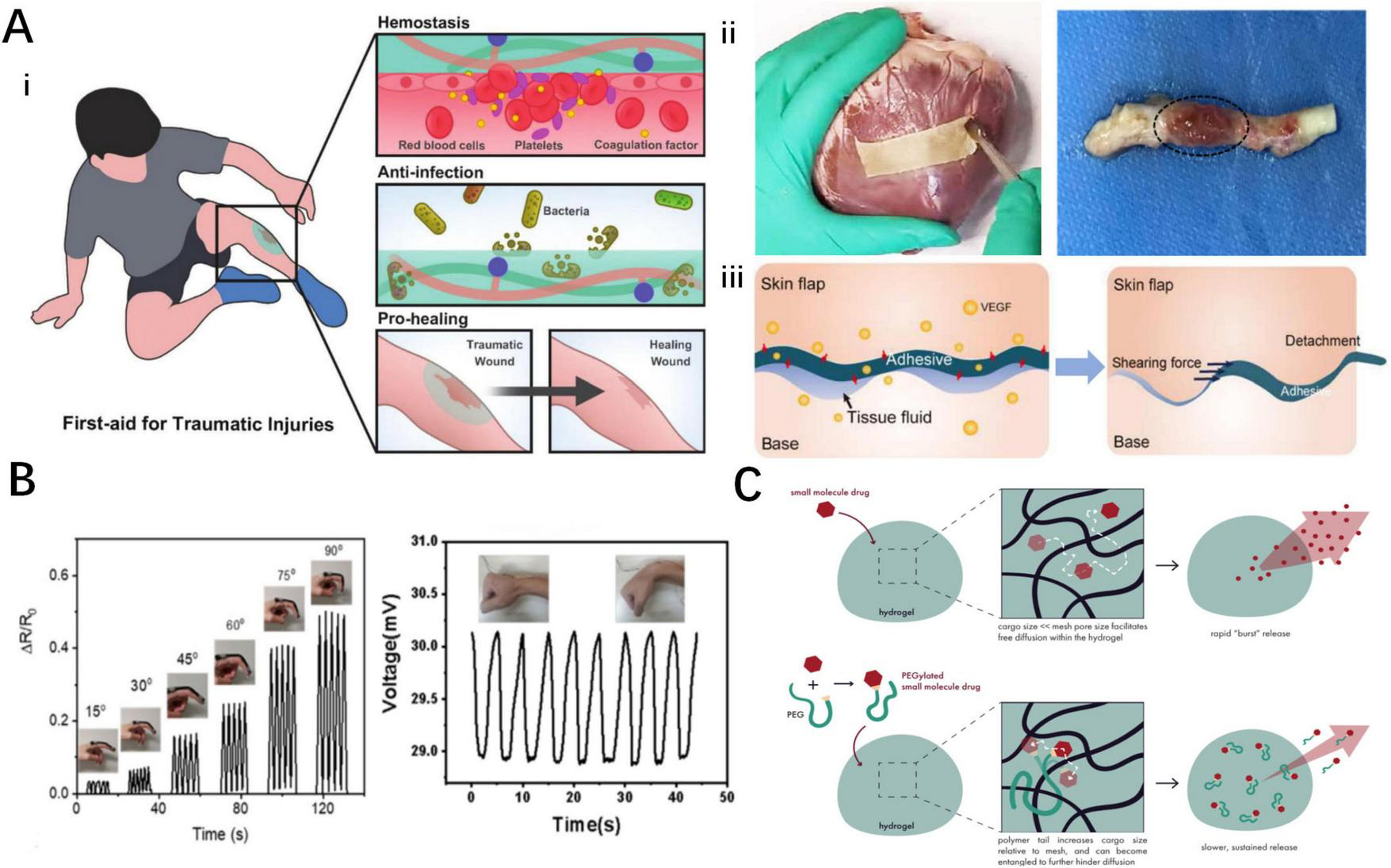

Biomedical applications of smart responsive tissue adhesives. (A) Smart responsive tissue adhesives for therapeutic dressings: (i) wound dressings for acute injuries (54), (ii) dressings for cardiovascular system diseases (56, 94), (iii) dressings for skin flap transplantation (101). (B) Smart responsive tissue adhesives for artificial skin sensors (39, 98). (C) Smart responsive tissue adhesives for drug delivery system (125).

3.1 Therapeutic dressings

Tissue adhesives can be applied in multiple clinical scenarios, such as wound dressings, cardiovascular system diseases and surgical incisions, and skin flap transplantations. Damaged tissues in direct contact with the external environment may lead to serious complications if they are not treated promptly and effectively. Therefore, the development of multifunctional therapeutic dressings holds significance (79, 80).

3.1.1 Wound dressings

Acute wounds are often accompanied by significant bleeding and bacterial contamination, while chronic wounds are typically in a state of prolonged inflammation and slow healing (9, 81). Conventional gauze used in clinical practice has limitations such as poor hemostatic effect, lack of antimicrobial effect, and the potential to damage newly formed tissue upon removal (82). Multifunctional smart wound dressings can address these deficiencies.

The wound bed after damage is susceptible to bacterial contamination, highlighting the importance of antibacterial properties in adhesive dressings (83). A widely adopted strategy involves incorporating antibacterial materials into the adhesives, such as nanoparticles bearing antibacterial properties. Liu et al. have developed the PBA/ZnCuO@GO biofoam based on Zn-CuO@GO nanosheets, which can kill 98% of Escherichia coli (E. coli) (63). Another antibacterial strategy involves using photothermal conversion materials to locally generate heat and denature the enzymes, thereby decreasing bacterial viability (84). In addition, Liang et al. incorporated iron ions into quaternized chitosan to prepare QCS-PA@Fe hydrogel adhesives with controllable NIR-assisted photothermal effect, which can kill bacteria without damaging normal tissues (53).

The hemostatic performance of medical adhesives plays a crucial role in acute bleeding wounds (79, 85). He et al. synthesized a rapidly hemostatic dressing with porous structures, named PBO hydrogel. This adhesive can effectively seal wounds and promote the aggregation of blood cells and the formation of blood clots to reduce bleeding time and volume (72).

Proper inflammation promotes the orderly healing of wounds, whereas excessive inflammation stimulates scar formation (86, 87). The phenolic groups in TA inhibit reactive oxygen species and free radicals to prevent excessive inflammation in the early stages of wound healing (88, 89). Concurrently, Chen et al. developed anti-inflammatory PEGDA/TA hydrogels. Wounds treated with this adhesive exhibited milder inflammation, faster healing, richer fibroblasts, and more orderly wound healing (62).

In chronic and difficult-to-heal wounds, wound dressings that promote angiogenesis can accelerate healing (90, 91). Lanthanide ion europium has been found to promote neovascularization. For this purpose, Fu et al. proposed tannin–europium coordination complex crosslinked citrate-based mussel-inspired bio-adhesives (TE-CMBAs) containing Eu-phenol ligands. In this adhesive, Eu ions promote the formation of new blood vessels, granulation tissue, and richer skin appendages, combined with the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of TA (61).

The aforementioned properties are vital for wound adhesive dressings. Hence, the development of all-in-one multifunctional wound adhesive dressings has become a major research focus (92). Fortunately, the wound adhesives currently under development not only simultaneously address the above-mentioned properties but also maintain their respective characteristics, thereby presenting broad application prospects (93).

3.1.2 Cardiovascular system diseases

The cardiovascular system plays a crucial role in maintaining circulation. Severe cardiovascular diseases typically have poor prognosis; in recent years, tissue adhesives have introduced new strategies for treating these conditions (94).

Trauma is one of the most common sources of peripheral vascular injuries (95). Vascular sealants with excellent hemostatic properties have promising applications. Liang et al. designed GT-SA-TPF, and Borden et al. developed an electrically-triggered QDM gel (40, 96). Both of them can adhere tightly to animal vascular tissues and withstand burst pressures higher than normal human blood pressure, making them ideal materials for sealing damaged vessels. Peripheral vascular damage can also be caused by injections. Xu et al. proposed a temperature-controlled chitosan-catechol-pNIPAM hydrogel coating for syringes (38). Mouse femoral vein models showed that it could effectively seal post-injection vessels and reduce bleeding.

Cardiovascular injuries usually result in significant bleeding and high mortality rates, while timely and effective hemostatic measures can improve the prognosis of severely injured patients (97, 98). Cheng et al. created the CaGOD/ZnO hydrogel by incorporating zinc ions to accelerate coagulation. Mouse cardiac perforation bleeding models demonstrated that the CaGOD/ZnO hydrogel not only reduced bleeding time and volume but also adhered stably to the ventricular wall, improving survival rates in cardiovascular injuries (54).

Myocardial ischemia (MI) and infarction are common cardiovascular diseases where inflammation induced by dying myocardial cells worsens the prognosis (99, 100). To address this issue, He et al. proposed the CPAMC/PCA Janus hydrogel cardiac patch (56). Containing ion-promoting agents, the CPAMC/PCA Janus hydrogel exhibits good electrical conductivity which could promote the maturation and functional recovery of myocardial cells. The patch contains large amounts of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory groups, effectively removing free radicals at the infarction site and reducing local inflammation. Additionally, echocardiography and histological analysis were performed in mouse heart attack models, revealing that the patch promotes neovascularization and structural and functional recovery of the myocardium, thereby improving the prognosis of MI (56).

3.1.3 Skin flap transplantation

Flap transplantation is a common clinical surgery, but flap survival rates remain suboptimal. Zhou et al. designed a pattern-tunable wrinkle hydrogel film adhesive to stabilize graft flaps and inhibit inflammation, while stimulating angiogenesis, thus improving graft flap survival (101).

3.2 Artificial skin sensors

Skin is a multifunctional organ that receives various stimuli from the external environment and provides corresponding feedback to the brain. Inspired by the human skin, the concept of artificial skin sensors has been proposed (102). They can sensitively monitor human biological signals, such as blood pressure, heart rates, and temperature to assess the overall health condition (103).

Artificial skin sensors achieve conductivity by introducing ions or ion channels into hydrogels to alter their electrical conductivity (104, 105). Di et al. developed a thermosensitive reversible nanocomposite hydrogel adhesive (NC-PDA/NC) containing a large number of freely mobile ions (34). This hydrogel is highly responsive to changes in compression and stretching states, leading to alterations in its resistance and conductivity. Additionally, some materials can form ion channels after ion binding. For instance, the QAAH hydrogel prepared by Shi et al. contains many ion channels and exhibits excellent electrical conductivity, enabling the detection of both temperature and pressure; the resulting changes in resistance achieve signal perception and transmission (44).

Introducing conductive polymers could also endow hydrogel adhesives with signal sensing and conduction capabilities (106, 107). Peng et al. incorporated the conductive polymer PEDOT: PSS into a double network hydrogel of poly(vinyl alcohol)/poly(acrylic acid) (PVA/PAA) to prepare PEDOT: PSS@PVA/PAA hydrogel (98). Under different tensile strains, the resistance of the PEDOT: PSS@PVA/PAA hydrogel changes responsively. This hydrogel has been tested to detect small human activities, such as wrist pulses and neck vocal cord vibrations, and has yielded satisfactory results (98).

Furthermore, Sun et al. proposed a special self-powered gradient hydrogel that showed strong adhesion with tissues via hydrophobic interactions (39). The self-induced electric potential changes with its thickness. Specifically, when the thickness of the hydrogel is altered by external pressure, the internal ion concentrations and the maximum output voltages of the hydrogel also change. This hydrogel can detect external signals, provide sensitive signal feedback, and return to its initial state rapidly when the pressure is released (39).

3.3 Drug delivery systems

Targeted drug delivery systems ensure that drugs reach therapeutic sites accurately, while controlled-release systems sustain local drug concentrations (108). Both types of drug delivery systems can improve therapeutic efficiency, reduce treatment costs, and minimize wastage. However, achieving on-demand regulation of drug delivery system duration remains a challenge.

Innovative micro drug delivery systems aim to release drugs at the targeted sites via minimally invasive debonding under external interventions (109). Lee et al. designed a temperature-sensitive adhesive inspired by octopus suckers, known as octopus-inspired hydrogel adhesive (OHA), which is applied as the base of microrobots (37). These microrobots can adhere tightly to the targeted sites and detach and exit from the bodies with minimal invasiveness after treatments under human interventions.

Controlled drug release can be achieved by introducing materials with drug dispersion advantages into highly biocompatible intelligent hydrogel adhesives (110) Chen et al. introduced electrospun polyurethane nanofibers (NF) into a hydrogel composed of Ag/TA -Cellulose nanofibers (Ag/TA-CNF) to prepare a bilayer nanocomposite hydrogel (NF@HG) (111). This adhesive adheres tightly to tissues through catecholamine chemistry and releases drugs slowly and sustainably in situ, thereby enhancing local drug concentrations.

4 Research hotspots and challenges

Current tissue adhesives possess multiple functions but cannot be applied in all environments for the reasons such as unstable adhesion in wet environments (112, 113), rupture of cross-linked networks under stress (114, 115), and non-compliance with the elastic modulus of the application site (16, 116). These unresolved issues limit the application of adhesives and hinder physiological activities. Researchers have proposed various solutions to address these problems (Figure 6).

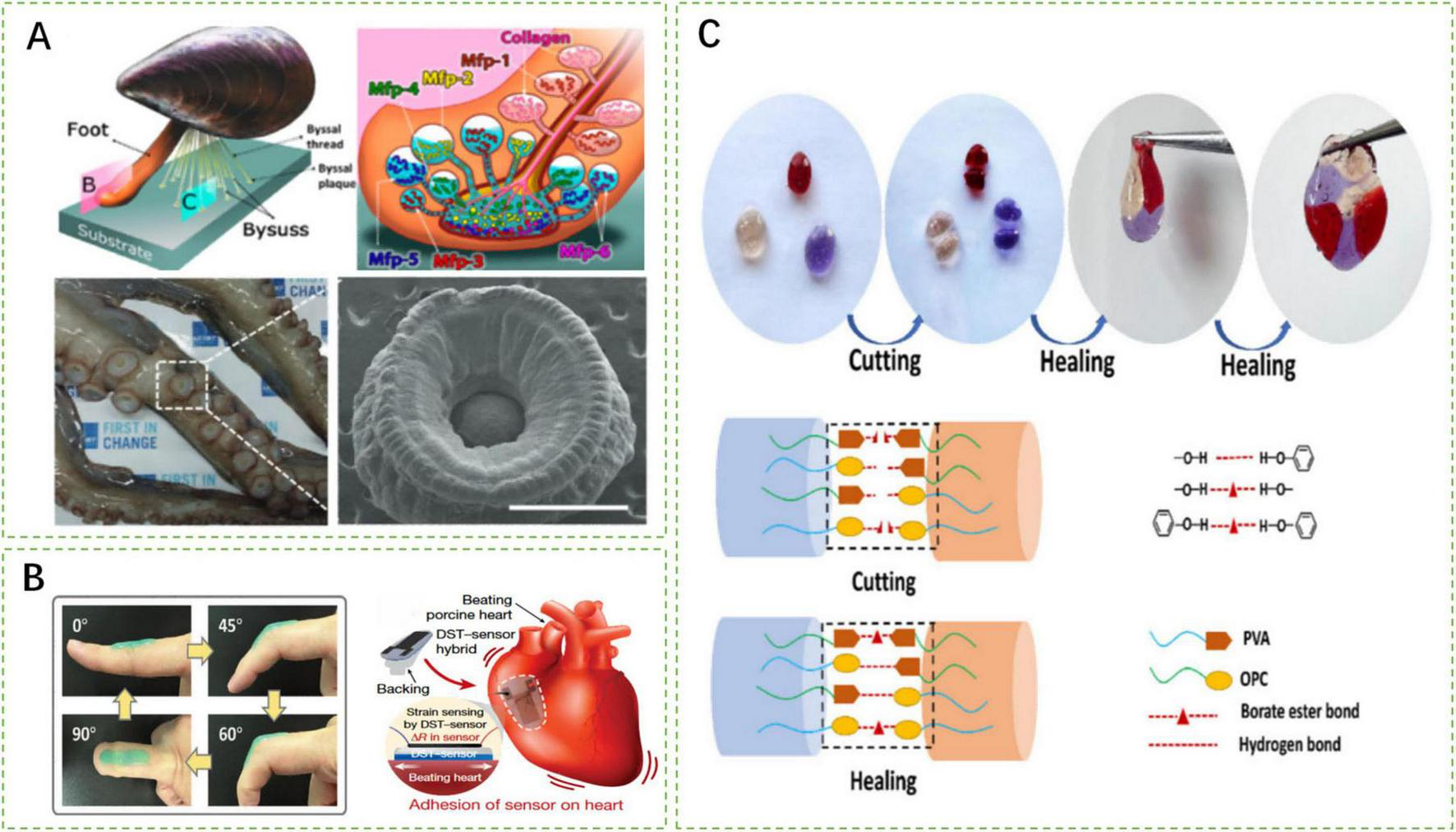

FIGURE 6

Schematic representation of research hotspots and challenges of smart responsive tissue adhesives. (A) Wet adhesion mechanism inspired by mussel foot protein and octopus suckers (112, 114). (B) Smart responsive tissue adhesives compliant with tissue elastic modulus (54, 115). (C) Mechanisms of self-healing characteristic of smart responsive tissue adhesives (72).

4.1 Wet adhesion

Normal physiological activities and disease recovery processes require a large amount of tissue fluid, such as in the gastrointestinal environment, cardiovascular system, or wound healing process. However, excessive exudation of tissue fluid negatively impacts the adhesion strength of adhesives (117). Therefore, the wet adhesion capability of smart responsive tissue adhesives is crucial.

Inspired by mussel foot proteins, researchers have discovered that the catechol-based adhesion of dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA) enables high-strength adhesion in moist environments. Fan et al. developed a poly(acrylic acid-co-3-((8,11,13)-pentadeca-trienyl) benzene-1,2-diol (UCAT)-chitosan hydrogel (P(AA-co-UCAT)-CS) that interacts with -NH2 and -SH groups on tissues to maintain good adhesion even underwater (118). The adhesive retains an adhesion strength of 1200 J/m2 after soaking in water for 6 h. Furthermore, Zhao et al. formulated a thermally responsive adhesive coating using DOPA polymer, adamantine (AD), methoxyethyl acrylate (MEA) monomer, poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (pNIPAM), and β-cyclodextrin (β-CD) (36). This adhesive coating achieves an adhesion strength of 4370 mJ/m2 to silicon substrates underwater.

The adhesion mechanisms and special structures of octopus suckers provide physical inspiration for wet adhesion (1). Inspired by the adhesive suction force generated by the deformation of suckers, Baik et al. proposed octopus-inspired architectures (OIAs) (66). Under preload, this structure achieves adhesion strengths of 41 and 154 kPa underwater and in silicone oil environments, respectively. Additionally, mimicking the protruding structures inside the suckers, Lee et al. designed OHA composed of pNIPAM (37). This adhesive absorbs water and swells at room temperature with its wet adhesion strength increasing as the effective adhesion area enlarges.

4.2 Self-healing properties

Hydrogel adhesives deform within the range of applied stress. However, when the stress exceeds this range, the crosslinked networks of adhesives collapse, and the integrity and mechanical properties are compromised (115). Self-healing properties could maintain adhesive integrity, preventing tissues or wounds from direct contact with the external environment to avoid contamination (114).

Smart tissue adhesives employ reversible chemical bonds to achieve the characteristic of self-healing, such as metal-ligand bonds, borate bonds, and hydrogen bonds, which congregate at incisions when the adhesives are cut (119). When the incised sides are approximated, complexation occurs, restoring the integrity of the adhesive. Xu et al. developed a CIPU: Cu2+ adhesive that takes advantage of the reformation of reversible Cu2+-ligand bonds (114). Moreover, the PBO hydrogel synthesized by He et al. realizes self-healing through reversible borate bonds and hydrogen bonds (72). With self-healing characteristics, smart tissue adhesives could maintain similar mechanical properties as before (113, 120).

4.3 Compliance with tissue elastic modulus

Different human tissues have varying elastic modulus. Adhesives with mismatched elastic modulus have a short lifespan, thereby limiting the normal physiological activities of tissues or organs (121). For tissue adhesives, appropriate elastic modulus is crucial and cannot be overlooked.

If the elastic modulus of cardiovascular adhesives does not match that of cardiovascular tissues, the adhesive is prone to detach or limit heart pumping functions during the contraction-relaxation cycles of hearts (122). He et al. developed a bilayer CPAMC/PCA hydrogel patch for cardiac applications, which not only exhibits excellent on-demand adhesion but also has a suitable elastic modulus that ensures that the adhesive performs its intended functions without affecting the heart’s normal activities (56).

Peripheral vessels are exposed to high-pressure blood flow, and vascular sealing adhesives must possess sufficient burst pressure thresholds to ensure normal blood flow without the patch deforming or rupturing (123). Borden et al. developed an electroadhesion QDM gel with a burst pressure reaching up to 252 mmHg higher than human blood pressure (76). Although the burst pressure decreases with increased vessel rupture size, it can be enhanced by introducing multiple gel layers.

Additionally, different tissues have different requirements for adhesive elastic modulus, such as joints and other flexible areas. Li and Liu et al. created a D. lapponicus-inspired adhesion structure (DIAS) capable of providing stable adhesive strength in various environments (65). Its excellent extensibility ensures a secure attachment during repeated flexion-extension cycles at the wrist.

4.4 Biocompatibility and safety

Thermosensitive adhesives typically operate within biologically safe temperature ranges. While formulations containing freely released copper or iron ions may induce cytotoxicity through oxidative stress, strategic material design-such as controlling ion release and employing biocomplexes-can effectively mitigate these risks while maintaining antibacterial efficacy.

Current tissue adhesives face clinical challenges such as insufficient wet adhesion, weak mechanical toughness, and potential biocompatibility issues, which may lead to adhesion failure or inflammatory responses. From a regulatory perspective, their classification as Class III medical devices demands rigorous evidence of safety and efficacy, while the lack of standardized evaluation protocols further prolongs the approval process.

5 Conclusion

Smart tissue adhesives not only retain the characteristics of convenience, ease of use, and low technical requirements of traditional tissue adhesives but also innovatively demonstrate advantages such as reversible adhesion, minimally invasive detachment, and matched degradation rates. Compared to conventional adhesives, smart responsive tissue adhesives better align with the demands of biomedical applications. This review introduced the reversible adhesion mechanisms, biomedical application scenarios, and recent research hotspots of smart tissue adhesives. With opportunities come challenges, and it is believed that with the advancement of biomedical and materials science, multifunctional smart responsive tissue adhesive systems will become more sophisticated, find wider applications, and ultimately benefit clinical practice.

Statements

Author contributions

SL: Writing – original draft, Visualization. QJ: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. JW: Writing – review & editing. SW: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. YZ: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant no. 2024M752888) and the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (grant no. LQN25H150001).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Hwang GW Lee HJ Kim DW Yang TH Pang C . Soft microdenticles on artificial octopus sucker enable extraordinary adaptability and wet adhesion on diverse nonflat surfaces.Adv Sci. (2022) 9:e2202978. 10.1002/advs.202202978

2.

Xu Q Wan Y Hu TS Liu TX Tao D Niewiarowski PH et al Robust self-cleaning and micromanipulation capabilities of gecko spatulae and their bio-mimics. Nat Commun. (2015) 6:8949. 10.1038/ncomms9949

3.

Li L Wang S Zhang Y Song S Wang C Tan S et al Aerial-aquatic robots capable of crossing the air-water boundary and hitchhiking on surfaces. Sci Robot. (2022) 7:eabm6695. 10.1126/scirobotics.abm6695

4.

Liu Z Yan F . Switchable Adhesion: on-demand Bonding and Debonding.Adv Sci. (2022) 9:e2200264. 10.1002/advs.202200264

5.

Han GY Kwack HW Kim YH Je YH Kim HJ Cho CS . Progress of polysaccharide-based tissue adhesives.Carbohydr Polym. (2024) 327:121634. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2023.121634

6.

Annabi N Tamayol A Shin SR Ghaemmaghami AM Peppas NA Khademhosseini A . Surgical materials: current challenges and nano-enabled solutions.Nano Today. (2014) 9:574–89. 10.1016/j.nantod.2014.09.006

7.

Annabi N Yue K Tamayol A Khademhosseini A . Elastic sealants for surgical applications.Eur J Pharm Biopharm. (2015) 95(Pt A):27–39. 10.1016/j.ejpb.2015.05.022

8.

Silva M Ferreira FN Alves NM Paiva MC . Biodegradable polymer nanocomposites for ligament/tendon tissue engineering.J Nanobiotechnology. (2020) 18:23. 10.1186/s12951-019-0556-1

9.

Nam S Mooney D . Polymeric tissue adhesives.Chem Rev. (2021) 121:11336–84. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00798

10.

Singer AJ Quinn JV Hollander JE . The cyanoacrylate topical skin adhesives.Am J Emerg Med. (2008) 26:490–6. 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.05.015

11.

Zöller K To D Bernkop-Schnürch A . Biomedical applications of functional hydrogels: innovative developments, relevant clinical trials and advanced products.Biomaterials. (2025) 312:122718. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2024.122718

12.

Han GY Hwang SK Cho KH Kim HJ Cho CS . Progress of tissue adhesives based on proteins and synthetic polymers.Biomater Res. (2023) 27:57. 10.1186/s40824-023-00397-4

13.

Xiong J Duan M Zou X Gao S Guo J Wang X et al Biocompatible tough ionogels with reversible supramolecular adhesion. J Am Chem Soc. (2024) 146:13903–13. 10.1021/jacs.4c01758

14.

Tan D Wang X Liu Q Shi K Yang B Liu S et al Switchable adhesion of micropillar adhesive on rough surfaces. Small. (2019) 15:e1904248. 10.1002/smll.201904248

15.

Jiang Y Trotsyuk AA Niu S Henn D Chen K Shih CC et al Wireless, closed-loop, smart bandage with integrated sensors and stimulators for advanced wound care and accelerated healing. Nat Biotechnol. (2023) 41:652–62. 10.1038/s41587-022-01528-3

16.

Larson C Peele B Li S Robinson S Totaro M Beccai L et al Highly stretchable electroluminescent skin for optical signaling and tactile sensing. Science. (2016) 351:1071–4. 10.1126/science.aac5082

17.

Hartmann B Fleischhauer L Nicolau M Jensen THL Taran FA Clausen-Schaumann H et al Profiling native pulmonary basement membrane stiffness using atomic force microscopy. Nat Protoc. (2024) 19:1498–528. 10.1038/s41596-024-00955-7

18.

Freedman BR Uzun O Luna NMM Rock A Clifford C Stoler E et al Degradable and removable tough adhesive hydrogels. Adv Mater. (2021) 33:e2008553. 10.1002/adma.202008553

19.

Zeng Q Han K Zheng C Bai Q Wu W Zhu C et al Degradable and self-luminescence porous silicon particles as tissue adhesive for wound closure, monitoring and accelerating wound healing. J Colloid Interface Sci. (2022) 607(Pt 2):1239–52. 10.1016/j.jcis.2021.09.092

20.

Bhagat V Becker ML . Degradable adhesives for surgery and tissue engineering.Biomacromolecules. (2017) 18:3009–39. 10.1021/acs.biomac.7b00969

21.

Sirolli S Guarnera D Ricotti L Cafarelli A . Triggerable patches for medical applications.Adv Mater. (2024) 36:e2310110. 10.1002/adma.202310110

22.

Zhang H Guo M . Thermoresponsive On-demand adhesion and detachment of a polyurethane-urea bioadhesive.ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. (2024) 16:43180–8. 10.1021/acsami.4c10778

23.

Moon HJ Ko du Y Park MH Joo MK Jeong B . Temperature-responsive compounds as in situ gelling biomedical materials.Chem Soc Rev. (2012) 41:4860–83. 10.1039/c2cs35078e

24.

Babaee S Pajovic S Kirtane AR Shi J Caffarel-Salvador E Hess K et al Temperature-responsive biometamaterials for gastrointestinal applications. Sci Transl Med. (2019) 11:eaau8581. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau8581

25.

Tan H Jin D Qu X Liu H Chen X Yin M et al A PEG-Lysozyme hydrogel harvests multiple functions as a fit-to-shape tissue sealant for internal-use of body. Biomaterials. (2019) 192:392–404. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.10.047

26.

Kim K Kim K Ryu JH Lee H . Chitosan-catechol: a polymer with long-lasting mucoadhesive properties.Biomaterials. (2015) 52:161–70. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.02.010

27.

Davidson MD Ban E Schoonen ACM Lee MH D’Este M Shenoy VB et al Mechanochemical adhesion and plasticity in multifiber hydrogel networks. Adv Mater. (2020) 32:e1905719. 10.1002/adma.201905719

28.

Ruffatto D Shah J Spenko M . Increasing the adhesion force of electrostatic adhesives using optimized electrode geometry and a novel manufacturing process.J Electrostat. (2014) 72:147–55. 10.1016/j.elstat.2014.01.001

29.

Cacucciolo V Shea H Carbone G . Peeling in Electroadhesion Soft Grippers.Extreme Mech Lett. (2022) 50:101529. 10.1016/j.eml.2021.101529

30.

Hou H Yin J Jiang X . Reversible diels-alder reaction to control wrinkle patterns: from dynamic chemistry to dynamic patterns.Adv Mater. (2016) 28:9126–32. 10.1002/adma.201602105

31.

Zhu CH Lu Y Chen JF Yu SH . Photothermal poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)/Fe3O4 nanocomposite hydrogel as a movable position heating source under remote control.Small. (2014) 10:2796–800. 10.1002/smll.201400477

32.

Nagase K Yamato M Kanazawa H Okano T . Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-based thermoresponsive surfaces provide new types of biomedical applications.Biomaterials. (2018) 153:27–48. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.10.026

33.

Zhu J Guan S Hu Q Gao G Xu K Wang P . Tough and pH-sensitive hydroxypropyl guar gum/polyacrylamide hybrid double-network hydrogel.Chem Eng J. (2016) 306:953–60. 10.1016/j.cej.2016.08.026

34.

Di X Kang Y Li F Yao R Chen Q Hang C et al Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)/polydopamine/clay nanocomposite hydrogels with stretchability, conductivity, and dual light- and thermo- responsive bending and adhesive properties. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. (2019) 177:149–59. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.01.058

35.

Zhang Z Qin C Feng H Xiang Y Yu B Pei X et al Design of large-span stick-slip freely switchable hydrogels via dynamic multiscale contact synergy. Nat Commun. (2022) 13:6964. 10.1038/s41467-022-34816-2

36.

Zhao Y Wu Y Wang L Zhang M Chen X Liu M et al Bio-inspired reversible underwater adhesive. Nat Commun. (2017) 8:2218. 10.1038/s41467-017-02387-2

37.

Lee YW Chun S Son D Hu X Schneider M Sitti M . A tissue adhesion-controllable and biocompatible small-scale hydrogel adhesive robot.Adv Mater. (2022) 34:e2109325. 10.1002/adma.202109325

38.

Xu R Ma S Wu Y Lee H Zhou F Liu W . Adaptive control in lubrication, adhesion, and hemostasis by Chitosan-Catechol-pNIPAM.Biomater Sci. (2019) 7:3599–608. 10.1039/c9bm00697d

39.

Sun D Peng C Tang Y Qi P Fan W Xu Q et al Self-powered gradient hydrogel sensor with the temperature-triggered reversible adhension. Polymers. (2022) 14:5312. 10.3390/polym14235312

40.

Liang Y Xu H Li Z Zhangji A Guo B . Bioinspired injectable self-healing hydrogel sealant with fault-tolerant and repeated thermo-responsive adhesion for sutureless post-wound-closure and wound healing.Nanomicro Lett. (2022) 14:185. 10.1007/s40820-022-00928-z

41.

Zheng J Zhu M Ferracci G Cho N-J Lee BH . Hydrolytic stability of methacrylamide and methacrylate in gelatin methacryloyl and decoupling of gelatin methacrylamide from gelatin methacryloyl through hydrolysis.Macromol Chem Phys. (2018) 219:1800266. 10.1002/macp.201800266

42.

Feng Q Wei K Zhang K Yang B Tian F Wang G et al One-pot solvent exchange preparation of non-swellable, thermoplastic, stretchable and adhesive supramolecular hydrogels based on dual synergistic physical crosslinking. NPG Asia Mater. (2018) 10:e455–455. 10.1038/am.2017.208

43.

Zhang T Guo Y Chen Y Peng X Toufouki S Yao S . A multifunctional and sustainable poly(ionic liquid)-quaternized chitosan hydrogel with thermal-triggered reversible adhesion.Int J Biol Macromol. (2023) 242(Pt 4):125198. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125198

44.

Shi X Wu PA . Smart patch with on-demand detachable adhesion for bioelectronics.Small. (2021) 17:e2101220. 10.1002/smll.202101220

45.

Yan Y Huang J Qiu X Cui X Xu S Wu X et al An ultra-stretchable glycerol-ionic hybrid hydrogel with reversible gelid adhesion. J Colloid Interface Sci. (2021) 582(Pt A):187–200. 10.1016/j.jcis.2020.08.008

46.

Yuan W Li Z Xie X Zhang ZY Bian L . Bisphosphonate-based nanocomposite hydrogels for biomedical applications.Bioact Mater. (2020) 5:819–31. 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.06.002

47.

Arias S Amini S Horsch J Pretzler M Rompel A Melnyk I et al Toward artificial mussel-glue proteins: differentiating sequence modules for adhesion and switchable cohesion. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. (2020) 59:18495–9. 10.1002/anie.202008515

48.

Xu H Zhao S Yuan A Zhao Y Wu X Wei Z et al Exploring self-healing and switchable adhesives based on multi-level dynamic stable structure. Small. (2023) 19:e2300626. 10.1002/smll.202300626

49.

Xue L Sanz B Luo A Turner KT Wang X Tan D et al Hybrid surface patterns mimicking the design of the adhesive toe pad of tree frog. ACS Nano. (2017) 11:9711–9. 10.1021/acsnano.7b04994

50.

Xi S Tian F Wei G He X Shang Y Ju Y et al Reversible dendritic-crystal-reinforced polymer gel for bioinspired adaptable adhesive. Adv Mater. (2021) 33:e2103174. 10.1002/adma.202103174

51.

Nguyen MK Alsberg E . Bioactive factor delivery strategies from engineered polymer hydrogels for therapeutic medicine.Prog Polym Sci. (2014) 39:1236–65. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2013.12.001

52.

Hu S Yang Z Zhai Q Li D Zhu X He Q et al An All-in-One “4A Hydrogel”: through first-aid hemostatic, antibacterial, antioxidant, and angiogenic to promoting infected wound healing. Small. (2023) 19:e2207437. 10.1002/smll.202207437

53.

Liang Y Li Z Huang Y Yu R Guo B . Dual-dynamic-bond cross-linked antibacterial adhesive hydrogel sealants with on-demand removability for post-wound-closure and infected wound healing.ACS Nano. (2021) 15:7078–93. 10.1021/acsnano.1c00204

54.

Cheng J Wang H Gao J Liu X Li M Wu D et al First-aid hydrogel wound dressing with reliable hemostatic and antibacterial capability for traumatic injuries. Adv Healthc Mater. (2023) 12:e2300312. 10.1002/adhm.202300312

55.

Perreault SD Wolff RA Zirkin BR . The role of disulfide bond reduction during mammalian sperm nuclear decondensation in vivo.Dev Biol. (1984) 101:160–7. 10.1016/0012-1606(84)90126-x

56.

He Y Li Q Chen P Duan Q Zhan J Cai X et al A smart adhesive Janus hydrogel for non-invasive cardiac repair and tissue adhesion prevention. Nat Commun. (2022) 13:7666. 10.1038/s41467-022-35437-5

57.

Chen X Yuk H Wu J Nabzdyk CS Zhao X . Instant tough bioadhesive with triggerable benign detachment.Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2020) 117:15497–503. 10.1073/pnas.2006389117

58.

Zhang P Wu J Xiao F Zhao D Luan Y . Disulfide bond based polymeric drug carriers for cancer chemotherapy and relevant redox environments in mammals.Med Res Rev. (2018) 38:1485–510. 10.1002/med.21485

59.

Ding X Li G Zhang P Jin E Xiao C Chen X . Injectable self-healing hydrogel wound dressing with cysteine-specific on-demand dissolution property based on tandem dynamic covalent bonds.Adv Funct Mater. (2021) 31:2011230. 10.1002/adfm.202011230

60.

Bei Z Lei Y Lv R Huang Y Chen Y Zhu C et al Elytra-mimetic aligned composites with air-water-responsive self-healing and self-growing capability. ACS Nano. (2020) 14:12546–57. 10.1021/acsnano.0c02549

61.

Fu M Zhao Y Wang Y Li Y Wu M Liu Q et al On-demand removable self-healing and ph-responsive europium-releasing adhesive dressing enables inflammatory microenvironment modulation and angiogenesis for diabetic wound healing. Small. (2023) 19:e2205489. 10.1002/smll.202205489

62.

Chen K Lin Q Wang L Zhuang Z Zhang Y Huang D et al An all-in-one tannic acid-containing hydrogel adhesive with high toughness, notch insensitivity, self-healability, tailorable topography, and strong, instant, and on-demand underwater adhesion. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. (2021) 13:9748–61. 10.1021/acsami.1c00637

63.

Liu J Zheng Z Luo J Wang P Lu G Pan J . Engineered reversible adhesive biofoams for accelerated dermal wound healing: intriguing multi-covalent phenylboronic acid/cis-diol interaction.Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. (2023) 221:112987. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2022.112987

64.

Liang S Chen H Chen Y Ali A Yao S . Multi-dynamic-bond cross-linked antibacterial and adhesive hydrogel based on boronated chitosan derivative and loaded with peptides from Periplaneta americana with on-demand removability.Int J Biol Macromol. (2024) 273(Pt 2):133094. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.133094

65.

Li S Liu H Tian H Wang C Wang D Wu Y et al Dytiscus lapponicus-inspired structure with high adhesion in dry and underwater environments. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. (2021) 13:42287–96. 10.1021/acsami.1c13604

66.

Baik S Kim DW Park Y Lee TJ Ho Bhang S Pang C . A wet-tolerant adhesive patch inspired by protuberances in suction cups of octopi.Nature. (2017) 546:396–400. 10.1038/nature22382

67.

Zhao L Tian H Liu H Zhang W Zhao F Song X et al Bio-inspired soft-rigid hybrid smart artificial muscle based on liquid crystal elastomer and helical metal wire. Small. (2023) 19:e2206342. 10.1002/smll.202206342

68.

Wang C Gao X Zhang F Hu W Gao Z Zhang Y et al Mussel inspired trigger-detachable adhesive hydrogel. Small. (2022) 18:e2200336. 10.1002/smll.202200336

69.

Chakma P Konkolewicz D . Dynamic covalent bonds in polymeric materials.Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. (2019) 58:9682–95. 10.1002/anie.201813525

70.

Chen WP Hao DZ Hao WJ Guo XL Jiang L . Hydrogel with ultrafast self-healing property both in air and underwater.ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. (2018) 10:1258–65. 10.1021/acsami.7b17118

71.

Chen M Wu Y Chen B Tucker AM Jagota A Yang S . Fast, strong, and reversible adhesives with dynamic covalent bonds for potential use in wound dressing.Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2022) 119:e2203074119. 10.1073/pnas.2203074119

72.

He Y Liu K Zhang C Guo S Chang R Guan F et al Facile preparation of PVA hydrogels with adhesive, self-healing, antimicrobial, and on-demand removable capabilities for rapid hemostasis. Biomater Sci. (2022) 10:5620–33. 10.1039/d2bm00891b

73.

Okada M Xie SC Kobayashi Y Yanagimoto H Tsugawa D Tanaka M et al Water-mediated on-demand detachable solid-state adhesive of porous hydroxyapatite for internal organ retractions. Adv Healthc Mater. (2024) 13:e2304616. 10.1002/adhm.202304616

74.

Fan X Fang Y Zhou W Yan L Xu Y Zhu H et al Mussel foot protein inspired tough tissue-selective underwater adhesive hydrogel. Mater Horiz. (2021) 8:997–1007. 10.1039/d0mh01231a

75.

Kristof J Blajan MG Shimizu K . A review on advancements in atmospheric plasma-based decontamination and drug delivery (Invited Paper).J Electrostat. (2025) 137:104083. 10.1016/j.elstat.2025.104083

76.

Borden LK Gargava A Raghavan SR . Reversible electroadhesion of hydrogels to animal tissues for suture-less repair of cuts or tears.Nat Commun. (2021) 12:4419. 10.1038/s41467-021-24022-x

77.

Liang Y Zhao X Hu T Chen B Yin Z Ma PX et al Adhesive hemostatic conducting injectable composite hydrogels with sustained drug release and photothermal antibacterial activity to promote full-thickness skin regeneration during wound healing. Small. (2019) 15:e1900046. 10.1002/smll.201900046

78.

Spotnitz WD Burks S . Hemostats, sealants, and adhesives: components of the surgical toolbox.Transfusion. (2008) 48:1502–16. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01703.x

79.

Ma Z Bao G Li J . Multifaceted design and emerging applications of tissue adhesives.Adv Mater. (2021) 33:e2007663. 10.1002/adma.202007663

80.

Peña OA Martin P . Cellular and molecular mechanisms of skin wound healing.Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2024) 25:599–616. 10.1038/s41580-024-00715-1

81.

He H Zhou W Gao J Wang F Wang S Fang Y et al Efficient, biosafe and tissue adhesive hemostatic cotton gauze with controlled balance of hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity. Nat Commun. (2022) 13:552. 10.1038/s41467-022-28209-8

82.

Zhao C Zhou L Chiao M Yang W . Antibacterial hydrogel coating: strategies in surface chemistry.Adv Colloid Interface Sci. (2020) 285:102280. 10.1016/j.cis.2020.102280

83.

Liu Y Xiao Y Cao Y Guo Z Li F Wang L . Construction of chitosan-based hydrogel incorporated with antimonene nanosheets for rapid capture and elimination of bacteria.Adv Funct Mater. (2020) 30:2003196. 10.1002/adfm.202003196

84.

Lu X Liu Z Jia Q Wang Q Zhang Q Li X et al Flexible bioactive glass nanofiber-based self-expanding cryogels with superelasticity and bioadhesion enabling hemostasis and wound healing. ACS Nano. (2023) 17:11507–20. 10.1021/acsnano.3c01370

85.

Coentro JQ Pugliese E Hanley G Raghunath M Zeugolis DI . Current and upcoming therapies to modulate skin scarring and fibrosis.Adv Drug Deliv Rev. (2019) 146:37–59. 10.1016/j.addr.2018.08.009

86.

Zhou Z Xiao J Guan S Geng Z Zhao R Gao BA . hydrogen-bonded antibacterial curdlan-tannic acid hydrogel with an antioxidant and hemostatic function for wound healing.Carbohydr Polym. (2022) 285:119235. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119235

87.

Eming SA Wynn TA Martin P . Inflammation and metabolism in tissue repair and regeneration.Science. (2017) 356:1026–30. 10.1126/science.aam7928

88.

Lin S Cheng Y Zhang H Wang X Zhang Y Zhang Y et al Copper tannic acid coordination nanosheet: a potent nanozyme for scavenging ros from cigarette smoke. Small. (2020) 16:e1902123. 10.1002/smll.201902123

89.

Liu T Lei H Qu L Zhu C Ma X Fan D . Algae-inspired chitosan-pullulan-based multifunctional hydrogel for enhanced wound healing.Carbohydr Polym. (2025) 347:122751. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2024.122751

90.

Zhao X Luo J Huang Y Mu L Chen J Liang Z et al Injectable antiswelling and high-strength bioactive hydrogels with a wet adhesion and rapid gelling process to promote sutureless wound closure and scar-free repair of infectious wounds. ACS Nano. (2023) 17:22015–34. 10.1021/acsnano.3c08625

91.

Chin LC Kumar P Palmer JA Rophael JA Dolderer JH Thomas GP et al The influence of nitric oxide synthase 2 on cutaneous wound angiogenesis. Br J Dermatol. (2011) 165:1223–35. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10599.x

92.

Wu SJ Yuk H Wu J Nabzdyk CS Zhao X . A multifunctional origami patch for minimally invasive tissue sealing.Adv Mater. (2021) 33:e2007667. 10.1002/adma.202007667

93.

Liu T Hao Y Zhang Z Zhou H Peng S Zhang D et al Advanced Cardiac Patches for the Treatment of Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. (2002) 149:2002–20. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.067097

94.

Hong Y Zhou F Hua Y Zhang X Ni C Pan D et al A strongly adhesive hemostatic hydrogel for the repair of arterial and heart bleeds. Nat Commun. (2060) 10:2060. 10.1038/s41467-019-10004-7

95.

Wang X Ansari A Pierre V Young K Kothapalli CR von Recum HA et al Injectable extracellular matrix microparticles promote heart regeneration in mice with post-ischemic heart injury. Adv Healthc Mater. (2022) 11:e2102265. 10.1002/adhm.202102265

96.

Deng J Yuk H Wu J Varela CE Chen X Roche ET et al Electrical bioadhesive interface for bioelectronics. Nat Mater. (2021) 20:229–36. 10.1038/s41563-020-00814-2

97.

Hoekstra A Struszczyk H Kivekäs O . Percutaneous microcrystalline chitosan application for sealing arterial puncture sites.Biomaterials. (1998) 19:1467–71. 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00060-x

98.

Peng X Wang W Yang W Chen J Peng Q Wang T et al Stretchable, compressible, and conductive hydrogel for sensitive wearable soft sensors. J Colloid Interface Sci. (2022) 618:111–20. 10.1016/j.jcis.2022.03.037

99.

Stegman BM Newby LK Hochman JS Ohman EM . Post-myocardial infarction cardiogenic shock is a systemic illness in need of systemic treatment: is therapeutic hypothermia one possibility?J Am Coll Cardiol. (2012) 59:644–7. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.010

100.

Zheng Y Li Z Yin M Gong X . Heme oxygenase-1 improves the survival of ischemic skin flaps (Review).Mol Med Rep. (2021) 23:235. 10.3892/mmr.2021.11874

101.

Zhou Y Yang L Liu Z Sun Y Huang J Liu B et al Reversible adhesives with controlled wrinkling patterns for programmable integration and discharging. Sci Adv. (2023) 9:eadf1043. 10.1126/sciadv.adf1043

102.

Liu C Wang Y Shi S Zheng Y Ye Z Liao J et al Myelin sheath-inspired hydrogel electrode for artificial skin and physiological monitoring. ACS Nano. (2024) 18:27420–32. 10.1021/acsnano.4c07677

103.

Amdursky N Głowacki ED Meredith P . Macroscale biomolecular electronics and ionics.Adv Mater. (2019) 31:e1802221. 10.1002/adma.201802221

104.

Hu W Ren Z Li J Askounis E Xie Z Pei Q . New dielectric elastomers with variable moduli.Adv Funct Materials. (2015) 25:4827–36. 10.1002/adfm.201501530

105.

Green R Abidian MR . Conducting polymers for neural prosthetic and neural interface applications.Adv Mater. (2015) 27:7620–37. 10.1002/adma.201501810

106.

Kohestani AA Xu Z Baştan FE Boccaccini AR Pishbin F . Electrically conductive coatings in tissue engineering.Acta Biomater. (2024) 186:30–62. 10.1016/j.actbio.2024.08.007

107.

Grassiri B Zambito Y Bernkop-Schnürch A . Strategies to prolong the residence time of drug delivery systems on ocular surface.Adv Colloid Interface Sci. (2021) 288:102342. 10.1016/j.cis.2020.102342

108.

Bokatyi AN Dubashynskaya NV Skorik YA . Chemical modification of hyaluronic acid as a strategy for the development of advanced drug delivery systems.Carbohydr Polym. (2024) 337:122145. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2024.122145

109.

Huang D Li D Wang T Shen H Zhao P Liu B et al Isoniazid conjugated poly(lactide-co-glycolide): long-term controlled drug release and tissue regeneration for bone tuberculosis therapy. Biomaterials. (2015) 52:417–25. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.02.052

110.

Zhang C Wu B Zhou Y Zhou F Liu W Wang Z . Mussel-inspired hydrogels: from design principles to promising applications.Chem Soc Rev. (2020) 49:3605–37. 10.1039/c9cs00849g

111.

Chen Y Zhang Y Mensaha A Li D Wang Q Wei Q . A plant-inspired long-lasting adhesive bilayer nanocomposite hydrogel based on redox-active Ag/Tannic acid-Cellulose nanofibers.Carbohydr Polym. (2021) 255:117508. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117508

112.

Ahn BK . Perspectives on mussel-inspired wet adhesion.J Am Chem Soc. (2017) 139:10166–71. 10.1021/jacs.6b13149

113.

Li X Fan D Sun Y Xu L Li D Sun B et al Porous magnetic soft grippers for fast and gentle grasping of delicate living objects. Adv Mater. (2024) 36:e2409173. 10.1002/adma.202409173

114.

Lee H Um DS Lee Y Lim S Kim HJ Ko H . Octopus-inspired smart adhesive pads for transfer printing of semiconducting nanomembranes.Adv Mater. (2016) 28:7457–65. 10.1002/adma.201601407

115.

Yuk H Varela CE Nabzdyk CS Mao X Padera RF Roche ET et al Dry double-sided tape for adhesion of wet tissues and devices. Nature. (2019) 575:169–74. 10.1038/s41586-019-1710-5

116.

Lee MW An S Yoon SS Yarin AL . Advances in self-healing materials based on vascular networks with mechanical self-repair characteristics.Adv Colloid Interface Sci. (2018) 252:21–37. 10.1016/j.cis.2017.12.010

117.

Hu O Lu M Cai M Liu J Qiu X Guo CF et al Mussel-bioinspired lignin adhesive for wearable bioelectrodes. Adv Mater. (2024) 36:e2407129. 10.1002/adma.202407129

118.

Pinnaratip R Bhuiyan MSA Meyers K Rajachar RM Lee BP . Multifunctional Biomedical Adhesives.Adv Healthc Mater. (2019) 8:e1801568. 10.1002/adhm.201801568

119.

Xu Y Rothe R Voigt D Hauser S Cui M Miyagawa T et al Convergent synthesis of diversified reversible network leads to liquid metal-containing conductive hydrogel adhesives. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:2407. 10.1038/s41467-021-22675-2

120.

Li CH Zuo JL . Self-healing polymers based on coordination bonds.Adv Mater. (2020) 32:e1903762. 10.1002/adma.201903762

121.

McCain ML Agarwal A Nesmith HW Nesmith AP Parker KK . Micromolded gelatin hydrogels for extended culture of engineered cardiac tissues.Biomaterials. (2014) 35:5462–71. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.03.052

122.

Nam S Lou J Lee S Kartenbender JM Mooney DJ . Dynamic injectable tissue adhesives with strong adhesion and rapid self-healing for regeneration of large muscle injury.Biomaterials. (2024) 309:122597. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2024.122597

123.

Yang Y He G Pan Z Zhang K Xian Y Zhu Z et al An injectable hydrogel with ultrahigh burst pressure and innate antibacterial activity for emergency hemostasis and wound repair. Adv Mater. (2024) 36:e2404811. 10.1002/adma.202404811

124.

Levine DJ Lee OA Campbell GM McBride MK Kim HJ Turner KT et al A low-voltage, high-force capacity electroadhesive clutch based on ionoelastomer heterojunctions. Adv Mater. (2023) 35:e2304455. 10.1002/adma.202304455

125.

Li J Mooney DJ . Designing hydrogels for controlled drug delivery.Nat Rev Mater. (2016) 1:16071. 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.71

Summary

Keywords

tissue adhesive, reversible, detachment, medical, mechanism

Citation