Abstract

Sepsis is a critical illness initiated by infection and characterized by a dysregulated inflammatory and oxidative stress response, leading to high mortality rates and impaired long-term quality of life. It is noteworthy that many sepsis patients have insufficient levels of vitamin C, an essential micronutrient. Due to its diverse physiological roles, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and antimicrobial-enhancing effects, vitamin C has gained significant attention as a potential adjunctive therapy for sepsis. However, the specific mechanisms by which vitamin C acts in sepsis are still not fully understood. Recent preclinical studies have shown that it can help reduce sepsis-induced organ damage, but clinical trials assessing its effectiveness have produced mixed results. Importantly, vitamin C's pharmacological effects depend on its concentration, and it has complex pharmacokinetics, which makes establishing an appropriate dosage regimen critical for achieving therapeutic outcomes in patients. This review aims to synthesize the current evidence regarding the therapeutic mechanisms of vitamin C in sepsis, identify limitations in the existing clinical research, and highlight future directions for investigation.

1 Introduction

Sepsis, a life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection, represents a major global public health concern, with an incidence of 677.5 cases per 100,000 people and a mortality rate of 148.1 per 100,000—accounting for 19.7% of global deaths (1). The primary pathological mechanism of sepsis-induced organ injury involves microcirculatory dysfunction, in which the endothelial glycocalyx—a critical layer of negatively charged polysaccharides and proteins essential for maintaining microvascular homeostasis—plays an important role. This structure regulates vascular tone and permeability while inhibiting leukocyte and platelet adhesion to the endothelium. During sepsis, activation of Toll-like receptors by pathogen- and damage-associated molecular patterns triggers dysregulated inflammation and oxidative stress. This cascade disrupts glycocalyx structural integrity and induces endothelial damage, exacerbating capillary leakage, microvascular immunothrombosis, and microcirculatory failure, ultimately leading to multiorgan dysfunction (2–5).

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) is an essential micronutrient, and most sepsis patients present with insufficiency, primarily due to metabolic consumption (6–9). Despite receiving standard nutritional support in the ICU, 88% of septic shock patients developed hypovitaminosis C (plasma concentration <23 μM), with 38% falling into the criteria for severe deficiency (<11 μM) (6). Importantly, initial vitamin C deficiency was significantly associated with increased 28-day mortality risk in patients with septic shock (adjusted RR: 2.65, 95% CI: 1.08–6.52, P = 0.032) (10), and lower vitamin C levels were also associated with more severe disease in children with sepsis (8). However, the effectiveness of vitamin C treatment regimens, whether administered alone or in combination with other agents, in improving organ function and mortality in sepsis patients remains a subject of debate (11–13). Several recent cohort studies have suggested that moderate-dose, longer-duration vitamin C regimens may significantly reduce mortality in patients with sepsis (14–16).

Functioning as an electron donor, vitamin C exhibits concentration-dependent redox effects (17). At concentrations ranging from 1 to 100 μM, it better protected endothelial function and improved microcirculation by increasing tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) levels, a coenzyme of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). However, concentrations exceeding 1 mM may produce pro-oxidant effects that interfere with BH4 elevation, underscoring the importance of an appropriate dosage regimen (18, 19).

Considering the substantial burden of sepsis, the widespread vitamin C insufficiency among patients, and the ongoing controversies regarding clinical outcomes, this review aims to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of vitamin C-mediated organ protection. Additionally, it will critically assess the limitations and controversies present in current clinical research and identify key directions for future investigation.

2 Organ-protective mechanisms of vitamin C

In addition to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, vitamin C protects organs in sepsis by targeting different pathways. The following sections delineate the organ-protective mechanisms and therapeutic outcomes substantiated by experimental and clinical evidence. Figure 1 shows a comprehensive overview of the key molecular pathways involved.

Figure 1

Molecular protective mechanisms of vitamin C in sepsis-induced organ injury. Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 and heme oxygenase-1 pathway; MAPK pathway, Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway; NF-κB pathway, Nuclear factor kappa B pathway; PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway; JAK2/STAT3 pathway, Janus Kinase2/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 pathway; PINK1-PARK2 pathway, PTEN-induced kinase 1-Parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase pathway; PD-1, Programmed death receptor-1.

2.1 Cardioprotective effects

Vitamin C protected against sepsis-induced cardiac injury through multiple pathways. First, it significantly reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine levels (interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α) in cardiac tissues while increased anti-inflammatory mediators (interleukin-10). This effect was mediated by suppressing phosphorylation in several critical signaling pathways, including P38, Erk1/2, and JNK in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway; nuclear factor kappa B and IKKα/β in the NF-κB pathway (20, 21); and the Janus Kinase 2/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 pathway (22). Simultaneously, it mitigated oxidative damage by markedly augmenting myocardial antioxidant enzyme activities (including catalase, glutathione, glutathione peroxidase, and superoxide dismutase) and decreasing levels of oxidative stress markers like myeloperoxidase and malondialdehyde (20, 23). Additionally, vitamin C enhanced cellular autophagy through inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway, evidenced by increased Beclin-1 expression, an elevated LC3-II/LC3-I ratio, and reduced P62 expression in myocardial tissue, while concurrently suppressed apoptotic processes (21). Finally, vitamin C alleviated myocardial injury by downregulating NADPH oxidase 4 expression in cardiomyocytes, which diminished reactive oxygen species (ROS) production; this inhibition of ROS subsequently blocked activation of the ROS-protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway, ultimately suppressing pyroptosis (24). Clinically, 3 g/day vitamin C reduced the levels of cardiac injury markers (e.g., troponin I and B-type natriuretic peptide) in sepsis patients (25).

2.2 Neuroprotective effects

The hippocampus, essential for learning and memory, is vulnerable to inflammation, which directly suppresses long-term potentiation and impairs cognition (26). Moreover, sepsis-induced endothelial glycocalyx degradation releases heparan sulfate fragments that cross the blood-brain barrier and accumulate in the hippocampus to impair long-term potentiation by inhibiting the brain-derived neurotrophic factor/tropomyosin receptor kinase B signaling pathway (27). Critically, inflammatory mediators suppress expression of the sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter 2, thereby reducing neuronal vitamin C uptake (28) and leading to a sharp decline in brain vitamin C levels (29). Supplementation with vitamin C reduced the levels of proinflammatory cytokines, activated the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 and heme oxygenase-1 pathways to counteract oxidative stress, and mitigated damage to the blood-brain barrier caused by matrix metalloproteinase-9 (endothelial glycocalyx-degrading enzyme). These effects significantly attenuated sepsis-induced pathological alterations, particularly CA1 pyramidal neuron loss, ultimately improving spatial learning and recognition memory (30, 31). Additionally, by inhibiting sepsis-induced overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor and the resulting increase in vascular permeability, sodium ascorbate reduced cerebral edema, thereby restoring cerebral perfusion and rapidly reversing the cerebral ischemia-hypoxia (32).

2.3 Pulmonary protection

The pulmonary endothelial glycocalyx, which is significantly thicker than in other microvascular beds, is critically involved in sepsis-induced acute lung injury (33). Its early degradation correlates with injury severity (34). For example, tumor necrosis factor-α activates heparanase to degrade heparan sulfate, a process that significantly reduces glycocalyx thickness (33). This is reflected clinically by a 23-fold increase in circulating heparan sulfate among patients with sepsis-induced lung injury compared to healthy controls (35) and higher syndecan-1 levels, another marker of glycocalyx degradation, in septic shock patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) compared with those without it (36).

Inhibiting the inflammatory response and protecting the endothelial glycocalyx layer constitute a pivotal therapeutic strategy against sepsis-induced lung injury. Studies found that vitamin C effectively attenuated lung inflammatory responses (e.g., by increasing peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor levels) and oxidative stress (e.g., by increasing the levels of arylesterase and paraoxonase) in a septic mouse model (37, 38). Clinically, vitamin C-treated patients with sepsis-associated ARDS exhibited attenuated syndecan-1 elevation and concurrent improvement in PaO2/FiO2 ratios at 48 h post-intervention. Specifically, for every 1 ng/ml reduction in syndecan-1 levels, the PaO2/FiO2 ratio increased by 8.85 (95% CI: 0.19–17.50; P = 0.045), suggesting that vitamin C improves lung function partly through endothelial glycocalyx preservation (39, 40). This effect on PaO2/FiO2 enhancement was also observed in critically ill COVID-19 patients (41). Furthermore, early vitamin C administration reduced the incidence of ARDS and ventilator-associated pneumonia in sepsis patients requiring mechanical ventilation (42).

2.4 Splenic immunomodulation

The septic mouse model induced significant pathological alterations in the spleen, manifested by enhanced cellular apoptosis, necrotic manifestations, and structural disorganization, accompanied by a substantial reduction in CD3+ T lymphocytes (43). During sepsis progression, the elevated expression of programmed death receptor-1 and its ligand suppressed T lymphocyte activation and induced T-cell exhaustion, resulting in a significant immunosuppressive phenotype (44, 45). Vitamin C intervention downregulated programmed death receptor-1 expression levels by inhibiting the phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 at the Y701 site, thereby reducing immune cell apoptosis and improving pathological changes in the spleen, ultimately reversing the sepsis-induced immunosuppression (43).

2.5 Renal protective mechanisms

Sepsis frequently induces acute kidney injury, which occurs in approximately 50% of patients and confers a higher mortality than non-septic acute kidney injury (46–48). Accumulating evidence underscores a protective role for vitamin C. Knocking out sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter-1 and−2 blocks ascorbic acid uptake, increasing the susceptibility of renal tubular cells to lipopolysaccharide-induced caspase-3-dependent apoptosis. Conversely, vitamin C supplementation promoted PTEN-induced kinase 1-Parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase axis-mediated mitophagy and inhibited apoptosis in human renal tubular cells (49). Combined therapy with hydrocortisone and vitamin C, or the combination of hydrocortisone, vitamin C, and thiamine (HAT), mitigated renal pathological injury during sepsis by attenuating inflammatory responses and oxidative stress (50, 51). Additionally, vitamin C downregulated the expression of drug-resistance genes and biofilm-associated genes in uropathogenic Escherichia coli, suppressed bacterial proliferation, and ultimately diminished inflammatory cell infiltration coupled with histopathological lesions in bladder and renal tissues (52, 53). Clinically, a multicenter randomized controlled trial reported reduced need for renal replacement therapy with vitamin C supplementation (OR: 0.28, 95% CI: 0.078–1.0; P = 0.05) (54), and large observational datasets indicated that vitamin C reduced mortality in patients with sepsis-induced acute kidney injury (55). However, conflicting evidence exists. One cohort study reported an increased acute kidney injury risk among sepsis patients treated with vitamin C (adjusted OR: 1.61, 95% CI: 1.09–2.39; P = 0.02) (56), and a randomized controlled trial found higher renal replacement therapy rates—though the interpretability of the latter finding is compromised by a high baseline renal replacement therapy rate in the vitamin C group (57). Consequently, large-scale, high-quality randomized controlled trials are warranted to clarify the true efficacy of vitamin C in sepsis-associated kidney injury.

3 Restoration of microcirculatory dynamics by vitamin C

Microcirculatory dysfunction is closely associated with the progression of sepsis and does not always improve in parallel with the stabilization of macrocirculation (2, 58). Theoretically, vitamin C mitigates oxidative stress and inhibit the secretion of inflammatory mediators, which suppress the overexpression of glycocalyx degrading enzyme, maintain the structural integrity of endothelial glycocalyx (40, 59), thereby preserving microcirculatory function (60–62). Nevertheless, a clinical study of high-dose intravenous vitamin C in sepsis patients requiring norepinephrine found this effect did not persist long-term (63). Additionally, the nitric oxide produced by eNOS is a key mediator of vasodilation. A critical aspect of eNOS function involves BH4, an essential cofactor readily oxidized to dihydrobiopterin during sepsis. Vitamin C stabilizes BH4 by inhibiting this oxidation. This action reduces dihydrobiopterin binding to eNOS, decreases ROS production, and maintains BH4 bioavailability, thereby preserving eNOS catalytic function and nitric oxide generation (18, 64–66). Furthermore, vitamin C scavenges superoxide anion radicals, preventing their reaction with nitric oxide to form peroxynitrite (67–69). These effects were substantiated by clinical research. Lavillegrand et al. (70) reported that intravenous vitamin C administration significantly improved mottling scores and capillary refill times in septic shock patients. When forearm endothelium-dependent microvascular reactivity was assessed via acetylcholine challenge tests, a marked elevation in cutaneous microvascular blood flow within 1 h after vitamin C administration. Furthermore, Wang's research (71) demonstrated that, compared to hydrocortisone monotherapy, HAT therapy significantly improved Perfusion Vessel Density, Total Vessel Density, and Microvascular Flow Index in septic shock patients. These specific sublingual microcirculation parameters were shown by meta-analysis to be lower in non-survivors than survivors (72). Collectively, these findings support the therapeutic value of vitamin C in the microcirculation of septic shock patients.

4 Clinical outcomes: evidence and controversies

Clinical trials of vitamin C for sepsis have yielded inconsistent outcomes (Table 1). The CITRIS-ALI trial (2019) reported that high-dose vitamin C significantly reduced 28-day all-cause mortality in sepsis patients with ARDS and increased ICU-free days between days 28 and 60 (39). Subsequently, the ViCTOR (76) and ORANGES trials (77) employing HAT reported accelerated shock resolution, consistent with findings from vitamin C monotherapy studies (42, 75). However, other trials evaluating either vitamin C monotherapy or HAT observed no reduction in vasopressor duration (78–82). Among these studies, the ViCTOR and ORANGES trials initiated treatment early (within 6 and 12 h of diagnosis, respectively). In contrast, the study by Lyu et al. (80), while also employing early intervention, exclusively enrolled patients with established septic shock and used a relatively high vitamin C dose (8 g/day). The neutral outcomes reported by Lyu et al. (80) align with a meta-analysis suggesting that high-dose vitamin C (≥6 g/day or 100 mg/kg/day) does not facilitate shock reversal in patients with septic shock, though a benefit may be maintained for those with sepsis without shock at enrollment (83). This underscores the critical influence of treatment timing and dosing strategy, a point explored in the next section.

Table 1

| Author, year | Study type | Study population | Sample size | Patient's age (year) | Dosing regimen | Primary site of infection | SOFA score | Short-term mortality (vitamin C group vs. control group) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C group/ control group | Vitamin C group | Control group | Vitamin C group | Control group | ||||||

| Fowler, 2019 (39) | Multicenter, double- blind, placebo randomized controlled trial | Adult patients with sepsis and ARDS | 84/83 | 54 (39, 67)a | 57 (44, 70) | 50 mg/kg every 6 h for 96 h | Thorax: 82.1%; Abdomen: 7.1%; Urinary tract: 3.6%; Central nervous system: 1.2% | Thorax: 69.9%; Abdomen: 15.7%; Urinary tract: 2.4%; Central nervous system: 3.6 | Difference in SOFA score change at 96 h between groups:−0.10 (95% CI: −1.23 to 1.03); P = 0.86 | 29.8 vs. 46.3%; P = 0.03 |

| Lamontagne, 2022 (73) | Multicenter, double- blind, placebo randomized controlled trial | Adult patients with proven or suspected infection and receiving a vasopressor | 429/433 | 65.0 ±14.0b | 65.2 ± 13.8 | 50 mg/kg every 6 h for 96 h | Pulmonary: 33.8%; Gastrointestinal or intra-abdominal: 31.0%; Blood: 12.8%; Skin or soft tissue: 12.8%; Urinary: 11.4% | Pulmonary: 36.7%; Gastrointestinal or intra-abdominal: 25.9%; Blood: 13.6%; Skin or soft tissue: 14.3%; Urinary: 12.7% | Difference in SOFA score at 96 h between groups: −0.03 (95% CI: −0.90 to 0.85); P >0.05 | 35.4 vs. 31.6%; P > 0.05 |

| Rosengrave, 2022 (74) | Single-center, double- blind, placebo randomized controlled trial | Adult patients with septic shock | 20/20 | 69 (64, 76) | 66 (57, 71) | 25 mg/kg every 6 h for 96 h | Abdominal: 40.0%; Pulmonary: 15.0%; Skin/soft tissue: 20.0%; Blood: 15.0%; Urinary tract: 10.0% | Abdominal: 30.0%; Pulmonary: 30.0%; Skin/soft tissue: 15.0%; Blood: 20.0%; Urinary tract: 5.0% | Difference in SOFA score at 96 h between groups: 1.2 (95% CI: −3.8 to 6.1); P = 0.64 | 30.0 vs. 35.0%; P > 0.05 |

| El Driny 2022, (42) | Single-center, double- blind, placebo randomized controlled trial | Adult patients with sepsis and required mechanical ventilation within 24 h from ICU admission | 20/20 | 53.0 ± 23.3 | 52.1 ± 18.8 | 1.5 g every 6 h for 96 h | Central venous catheter: 35.0%; Urinary tract infection: 25.0%; Abdominal: 20.0%; Skin and soft tissue: 10.0% | Central venous catheter: 30.0%; Urinary tract infection: 30.0%; Abdominal: 10.0%; Skin and soft tissue: 20.0% | Comparison of SOFA scores at 96 h: 5.2 ± 2.0 in the vitamin C group vs. 9.0 ± 2.6 in the control group; P < 0.01 | 15.0 vs. 45.0%; P = 0.04 |

| Wacker, 2022 (57) | Multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled trial | Adult patients with septic shock | 60/64 | 68.9 (60.1, 79.9) | 73.0 (60.8, 80.0) | 1 g intravenous injection followed by 250 mg/h infusion for 96 h or 24 h vasopressor-free (whichever first) | Pulmonary: 21.6%; Urinary: 26.6%; Gastrointestinal/ biliary: 20%; Soft tissue/skin: 6.7%; Bacteremia: 10.0% | Pulmonary: 25.0%; Urinary: 21.9%; Gastrointestinal/ biliary: 21.9%; Soft tissue/skin: 10.9%; Bacteremia: 6.2% | No significant difference in SOFA score change between groups | 26.7 vs. 40.6%; P = 0.1 |

| Belousoviene, 2023 (63) | Single-center, double- blind, placebo randomized controlled trial | Adult patients with sepsis requiring norepinephrine | 12/11 | 66 (56, 78) | 60 (50, 76) | 50 mg/kg every 6 h for 96 h | Pneumonia: 33.3%; Abdomen: 58.4%; Urinary tract: 8.3% | Pneumonia: 45.5%; Abdomen: 9.1% Urinary tract: 27.3% | Comparison of SOFA scores change at 96 h: 0 (0, 4) in the vitamin C group vs. 2 (0, 4) in the control group; P = 0.36 | 58.3 vs. 54.5%; P = 0.85 |

| Li, 2024 (65) | Single-center, double-blind randomized controlled trial | Adult patients with septic shock | High-dose vitamin C group: 20; low-dose vitamin C group: 20 control group: 18 | High-dose vitamin C group:72.00 ± 14.67; low-dose vitamin C group: 63.30 ± 17.13 | 67.78 ± 13.53 | High-dose vitamin C (150 mg/kg/d) and low-dose vitamin C (50 mg/kg/d) for 96 h | High-dose vitamin C group: lungs: 40.0%; Biliary tract: 30.0%; Blood: 20.0%; Abdomen: 10.0% low-dose vitamin C group: lungs: 60.0%; Biliary tract: 10.0%; Blood: 10.0%; Abdomen: 20.0% | Lungs: 66.67%; Biliary tract: 11.1%; Blood: 11.1% Abdomen: 11.1% | Comparison of SOFA scores change at 96 h: −0.27 ± 0.24 in the high-dose vitamin C group vs. −0.46 ± 0.34 in the low-dose vitamin C group vs. −0.27 ± 0.22 in the control group; P > 0.05 | High-dose vitamin C group: 0% vs. low-dose vitamin C group: 10.0% vs. control group: 16.7%; no significant pairwise differences |

| Jiang, 2024 (25) | Randomized controlled trial | Patients with sepsis and APACHE II Scores ≥12 | 42/41 | 53.25 ± 13.21 | 53.28 ± 13.18 | 3 g everyday for 72 h | None | None | Post-treatment SOFA scores significantly lower in the vitamin C group compared to control group; P < 0.05 | 9.52 vs. 29.27%; P < 0.05 |

| Mishra, 2024 (75) | Randomized controlled trial | Adult patients with suspected infection, having temperature >38 °C, heart rate >100 beats per minute, and quick SOFA scores ≥2 | 25/25 | None | None | 2.5 g every 8 h for 5 days | Surgical patients | Surgical patients | Comparison of SOFA scores at 6 days: 3.91 ± 2.76 in the vitamin C group vs. 6.00 ± 3.64 in the control group; P = 0.04 | 12.0 vs. 24.0%; P = 0.52 |

| Vandervelden, 2025 (54) | Multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled trial | Adult patients with a suspected infection and a National Early Warning Scores ≥5 | 147/145 | 64.7 ± 16.2 | 67.0 ± 13.9 | 1.5 g every 6 h for 96 h | Respiratory: 46.3%; Gastro-intestinal: 7.5%; Urinary: 19.1%; Skin or soft tissue: 11.6% | Respiratory: 53.1%; Gastro-intestinal: 8.3%; Urinary: 23.5%; Skin or soft tissue: 6.9% | Comparison of the average post-baseline SOFA scores on day 2 to 5: 1.98 (95% CI: 1.69 to 2.32) in the vitamin C group vs. 2.19 (95% CI: 1.87 to 2.56) in the control group; P = 0.30 | 12.0 vs. 7.9%; P = 0.27 |

Characteristics of recent randomized controlled trials of vitamin C monotherapy in sepsis.

ARDS, Acute respiratory distress syndrome; APACHE, Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation; SOFA, Sequential organ failure assessment; CI, Confidence intervals.

aMedian (interquartile range).

bMean ± Standard deviation.

With the exception of the VITAMINS trial (82), which reported an unadjusted improvement in sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) scores, other major randomized controlled trials have not shown mortality or SOFA benefits with HAT (76–80, 84, 85). The unclear efficacy of vitamin C monotherapy is compounded by its combination with corticosteroids and thiamine, complicating the evaluation of its independent role and synergy.

More concerningly, the LOVIT trial revealed not only lack of mortality benefit with high-dose vitamin C in septic shock but an increased risk of death or persistent organ dysfunction (73), with no differential effects across inflammatory phenotypes (86). This finding was reinforced by a Bayesian reanalysis indicating vitamin C significantly increased adverse outcomes (28-day mortality or organ dysfunction) in critically ill patients with confirmed/suspected infections requiring vasoactive medications (RR 1.20, 95% CI 1.04–1.39; 99% probability of harm) (87). Conversely, similar to the CITRIS-ALI approach, recent studies targeting precise populations (such as mechanically ventilated patients or those with acute kidney injury) found vitamin C reduced sepsis mortality risk (42, 55). These conflicting results indicate heterogeneous treatment responses to vitamin C among different sepsis phenotypes. Future studies should aim to delineate these subgroups, particularly since cohort data have already suggested survival differences stratified by infection site in patients receiving vitamin C (16).

5 Optimizing clinical applications: challenges and research priorities

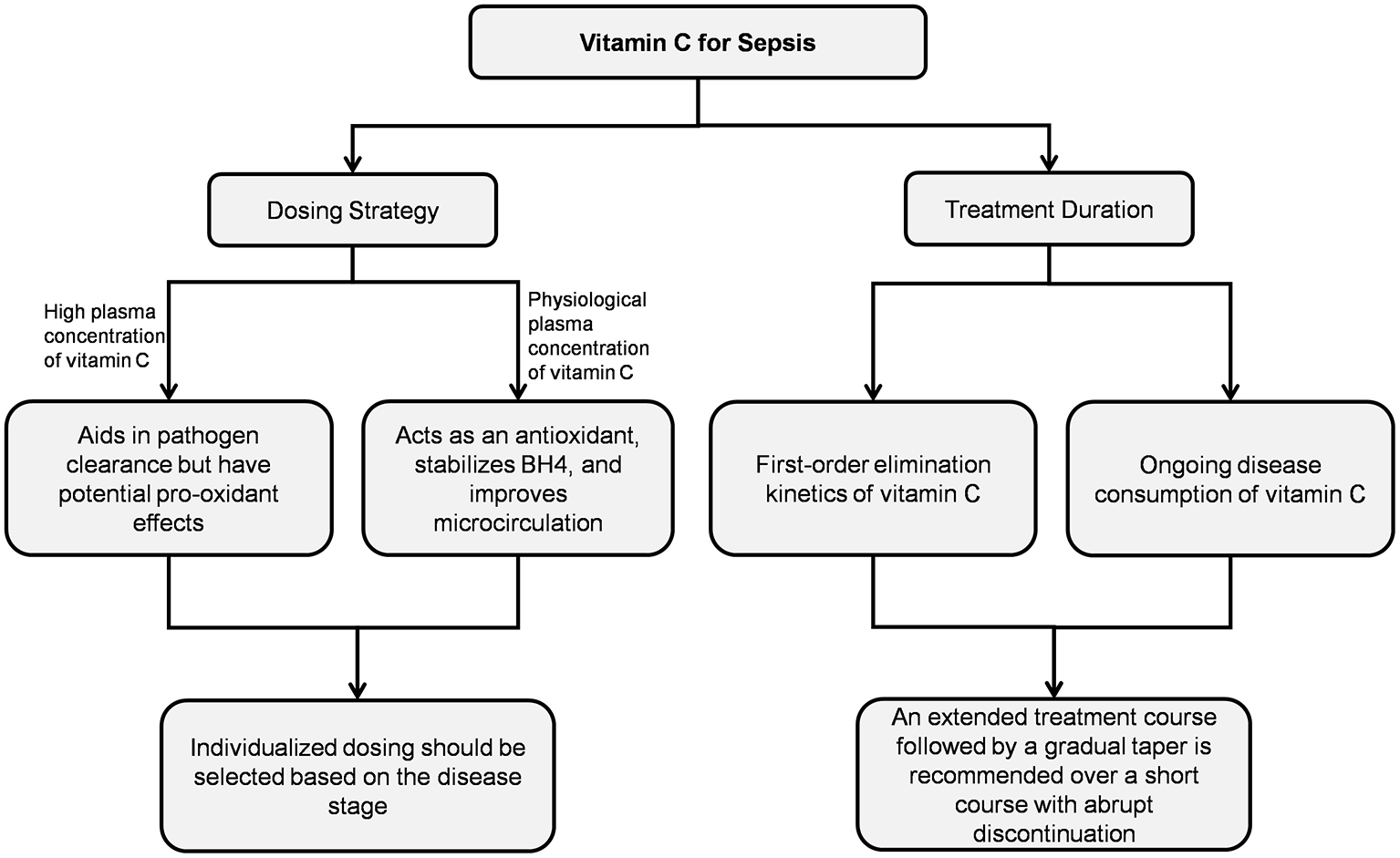

Animal studies have demonstrated that vitamin C exerts multiple protective effects against sepsis-induced organ damage, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and pro-autophagy. Furthermore, in vitro human studies found that vitamin C selectively inhibited lipopolysaccharide-induced cytokine secretion in a concentration-dependent manner (88–91). However, clinical trial results remain controversial. These inconsistencies suggest that the actual clinical efficacy of vitamin C in sepsis patients may be modulated by multiple factors (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Vitamin C treatment regimens.

5.1 Dosing strategies

The plasma concentration of vitamin C determines its distinct biological effects. Clinical studies on critical illnesses used wide dosing ranges (450–24,000 mg/day) (92), and high-dose short-course regimens represent the mainstream therapeutic strategy for vitamin C in sepsis-related research. However, subgroup data from the meta-analysis revealed that vitamin C at effective doses of 25–100 mg/kg/day significantly improved mortality in sepsis patients (OR: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.65–0.97; P = 0.03). No survival benefit was observed at doses exceeding 100 mg/kg/day, indicating the importance of dosage optimization in clinical decision-making (93).

5.1.1 Effects at physiological concentrations

At physiological concentrations (1–100 μM), vitamin C chemically stabilized BH4, saturating at 100 μM to preserve eNOS function (18). Research has found that a single intravenous injection of 40 mg/kg vitamin C significantly improved skin microvascular blood flow in septic shock patients at 1 h (70). Administering 1.5 g per dose every 6 h significantly improved microcirculatory blood flow in shock patients within 24 h (71). However, when the plasma vitamin C concentration reached 1 mM, the BH4 concentration did not increase but instead slightly decreased. This effect was likely related to the pro-oxidant activity of high-concentration vitamin C interfering with BH4 levels (18).

5.1.2 Implications of high-dose administration

High plasma concentrations of vitamin C contributed to pathogen clearance but may also carry potential adverse effects. Salmonella-derived glyoxalate inhibited host TET2 DNA dioxygenase, aiding bacterial antibiotic resistance. Research has demonstrated that administration of 400 mg/kg vitamin C suppresses glyoxalate production, reactivates TET2, and reverses glyoxalate-induced downregulation of pro-inflammatory genes (Nos2, Cxcl9, and Cxcl10) essential for infection defense (94). However, intravenous administration of 200 mg/kg/day vitamin C in sepsis patients could yield serum concentrations of 3,082 μM (95). At millimolar concentrations in extracellular fluids, ascorbic acid promoted H2O2 generation in a concentration-dependent manner (19). Although normal tissues efficiently decompose H2O2 due to abundant catalase and glutathione peroxidase, septic tissues exhibit reduced levels of these antioxidant enzymes (96–98) and accumulate elevated intracellular free iron ions (99, 100). Under these conditions, high-dose vitamin C may potentially exacerbate oxidative stress via the Fenton reaction. Additionally, neutrophils from sepsis patients showed reduced neutrophil extracellular trap formation at vitamin C concentrations ≤ 1 mM, whereas ≥5 mM concentrations enhanced chemotaxis, phagocytic activity, and neutrophil extracellular trap generation (101). Although neutrophil extracellular trap combat microbial infections, excessive neutrophil extracellular trap formation could exacerbate inflammatory responses, promote immunothrombosis, cause host tissue damage, and ultimately lead to adverse clinical outcomes (102–106). Such drug-induced damage cannot be overlooked in sepsis patients experiencing hyperinflammatory states.

5.1.3 Translational gaps between preclinical and clinical studies

Most preclinical studies administer high-dose intravenous vitamin C within hours of sepsis model induction or preemptively (21, 23, 43, 64, 98), a timing that is clinically challenging to replicate due to the difficulty in promptly identifying sepsis in patients (107). However, this timing discrepancy proves critical, as demonstrated by one septic animal model where high-dose vitamin C administered 12 h post-modeling failed to achieve the therapeutic efficacy observed with immediate administration (64). Consequently, very early high-dose vitamin C administration in animal models effectively clear pathogens, thereby attenuating infection-induced excessive inflammation and oxidative stress. But its potential pro-oxidant effects may exacerbate oxidative stress in septic shock—a state characterized by ongoing depletion of already diminished antioxidant enzymes. This divergence was indirectly supported by meta-analysis findings: vitamin C at ≥6g/day or 100 mg/kg/day reduced mortality in sepsis patients without shock upon enrollment but not in those with established shock (83). Collectively, these findings indicate that the stage of sepsis is critical, and high-dose vitamin C may be unsuitable for patients with established shock.

5.2 Treatment duration considerations

5.2.1 Pharmacokinetics of vitamin C

The lack of the L-gluconolactone oxidase gene in humans results in an inability to synthesize endogenous vitamin C and requires additional supplementation. Vitamin C exists in vivo in two biochemical forms: ascorbic acid and dehydroascorbic acid. Ascorbic acid undergoes oxidation to dehydroascorbic acid, whereas dehydroascorbic acid irreversibly degrades into oxalic acid that undergoes renal excretion via urinary pathways. Following high-dose intravenous administration, vitamin C was eliminated with first-order kinetics at a rapid rate. The elimination half-life is approximately 2 h in cancer patients, while in septic shock patients, it is approximately 6.9 h (108–110). This forms the basis for the every 6-h dosing schedule in many experimental protocols.

5.2.2 Influence of treatment duration on efficacy

Recent survival curves in a septic mouse model demonstrated that consecutive 8-day vitamin C treatment significantly improved survival rates compared to the placebo group, while a shorter 4-day regimen showed no beneficial effect (111). This is consistent with a cohort study (16) in which sepsis patients receiving prolonged therapy (≥5 days, mean daily dose ~6 g) achieved superior clinical outcomes compared to those with shorter durations (1–2 days or 3–4 days), with significantly reduced in-hospital mortality and 90-day mortality. However, most randomized controlled trials investigating vitamin C for sepsis employed treatment durations of 3–7 days, predominantly ≤ 4 days (91). It should be noted that 15% of patients with multiple organ dysfunction receiving vitamin C therapy (2 g/day or 10 g/day) exhibited serum concentrations dropping to deficiency levels within 48 h post-treatment discontinuation (112). Analysis of the LOVIT trial, which used a 4-day treatment course, revealed no mortality difference during the treatment period itself; however, the vitamin C group experienced significantly more deaths within 1 week after treatment cessation (RR: 1.9, 95% CI: 1.2–2.9; P =0.004) (113). This may be attributable to the rapid decline in serum vitamin C concentration and resultant redox imbalance following abrupt discontinuation. A recent study found that sepsis patients with baseline SOFA scores ≥6 receiving 6 g/day vitamin C for 4 days showed significantly lower SOFA scores than controls, though with no significant mortality difference (54). In comparison, another study using the same dose (6 g/day) demonstrated a 46% reduction in mortality among sepsis patients with SOFA scores ≥9 when vitamin C supplementation was maintained throughout their ICU stay (15). These findings underscore the significance of determining an appropriate duration of vitamin C therapy in sepsis patients to avert rebound adverse effects associated with abrupt treatment termination.

5.3 Identification of responsive patient populations

Researchers have classified sepsis into four distinct phenotypes: the α phenotype, characterized by minimal vasopressor requirements; the β phenotype, typically observed in older patients with multiple underlying chronic conditions and renal insufficiency; the γ phenotype, predominantly exhibiting inflammatory responses and pulmonary dysfunction; and the δ phenotype, more frequently associated with hepatic insufficiency and septic shock. Mortality rates and inflammatory responses varied across these phenotypes, underscoring the heterogeneity of sepsis (114). Vitamin C primarily exerts antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Observational studies revealed that patients receiving vitamin C therapy derive significantly greater benefit if they belong to a high-inflammatory response group compared to a low-inflammatory response group (115, 116). Moreover, an in vitro study demonstrated that vitamin C suppressed the release of inflammatory cytokines and ROS in human whole blood induced by Escherichia coli, but not by Staphylococcus aureus (117). This suggests a differential effect of vitamin C treatment depending on the type of sepsis, although further confirmation through randomized controlled trials is required.

6 Conclusion

In conclusion, vitamin C represents a promising adjunctive therapy in sepsis, conferring organ protection through multiple mechanisms. However, its complex pharmacokinetics and the heterogeneity of sepsis necessitate optimized timing and individualized regimens. As demonstrating its universal mortality benefit is challenging, future efforts should prioritize identifying patient subgroups with a favorable response to vitamin C. A proper assessment of its utility should integrate a spectrum of measures that encompass both direct biological measures, such as oxidative stress markers (e.g., total oxidant status, total antioxidant status) and inflammatory markers (e.g., Interleukin-6), and indirect functional parameters, including microcirculatory hemodynamics and organ function scores, to comprehensively evaluate therapeutic efficacy.

Statements

Author contributions

YX: Conceptualization, Data curation, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FG: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing. LZ: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. CG: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by Hunan Province Science and Technology Innovation Program Project (Project No. 2023SK2020).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Rudd KE Johnson SC Agesa KM Shackelford KA Tsoi D Kievlan DR et al . Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990-2017: analysis for the global burden of disease study. Lancet. (2020) 395:200–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32989-7

2.

Aksu U Yavuz-Aksu B Goswami N . Microcirculation: current perspective in diagnostics, imaging, and clinical applications. J Clin Med. (2024) 13:6762. doi: 10.3390/jcm13226762

3.

Zhan JH Wei J Liu YJ Wang PX Zhu XY . Sepsis-associated endothelial glycocalyx damage: a review of animal models, clinical evidence, and molecular mechanisms. Int J Biol Macromol. (2025) 295:139548. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.139548

4.

Zhu L Dong H Li L Liu X . The mechanisms of sepsis induced coagulation dysfunction and its treatment. J Inflamm Res. (2025) 18:1479–95. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S504184

5.

Zhang W Jiang L . Sepsis-induced endothelial dysfunction: permeability and regulated cell death. J Inflamm Res. (2024) 17:9953–73. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S479926

6.

Carr AC Richards PC Berry S Chambers S Marshall J Shaw GM . Hypovitaminosis C and vitamin C deficiency in critically ill patients despite recommended enteral and parenteral intakes. Crit Care. (2017) 21:300. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1891-y

7.

Spencer E Rosengrave P Williman J Shaw G Carr AC . Circulating protein carbonyls are specifically elevated in critically ill patients with pneumonia relative to other sources of sepsis. Free Radic Biol Med. (2022) 179:208–12. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.11.029

8.

McWhinney B Ungerer J LeMarsey R Phillips N Raman S Gibbons K et al . Serum levels of vitamin C and thiamin in children with suspected sepsis: a prospective observational cohort study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. (2024) 25:171–6. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000003349

9.

Hu J Zhang J Li D Hu X Li Q Wang W et al . Predicting hypovitaminosis C with lasso algorithm in adult critically ill patients in surgical intensive care units: a bi-center prospective cohort study. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:5073. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-54826-y

10.

Park JE Shin TG Jeong D Lee GT Ryoo SM Kim WY et al . Association between vitamin C deficiency and mortality in patients with septic shock. Biomedicines. (2022) 10:2090. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10092090

11.

Pei H Qu J Chen JM Zhang YL Zhang M Zhao GJ et al . The effects of antioxidant supplementation on short-term mortality in sepsis patients. Heliyon. (2024) 10:e29156. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29156

12.

Saghafi F Moghadam ZB Salehi-Abargouei A Beigrezaei S Sohrevardi SM Jamialahmadi T et al . Therapeutic role of hat therapy in sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Med Chem. (2025) 32:3258–82. doi: 10.2174/0109298673245464231121094448

13.

Deng J Zuo QK Venugopal K Hung J Zubair A Blais S et al . Efficacy and safety of hydrocortisone, ascorbic acid, and thiamine combination therapy for the management of sepsis and septic shock: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. (2024) 185:997–1018. doi: 10.1159/000538959

14.

Wazir K Abubakar M Anwar A Rahat Rashid F Adil A Sajjad M . Vitamin C in sepsis: exploring its role in modulating inflammation and oxidative stress. Cureus. (2025) 17:e81386. doi: 10.7759/cureus.81386

15.

Gonzalez-Vazquez SA Gomez-Ramirez EE Gonzalez-Lopez L Gamez-Nava JI Peraza-Zaldivar JA Santiago-Garcia AP et al . Intravenous vitamin C as an add-on therapy for the treatment of sepsis in an intensive care unit: a prospective cohort study. Medicina. (2024) 60:464. doi: 10.3390/medicina60030464

16.

Jung SY Lee MT Baek MS Kim WY . Vitamin C for ≥ 5 days is associated with decreased hospital mortality in sepsis subgroups: a nationwide cohort study. Crit Care. (2022) 26:3. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03872-3

17.

Lykkesfeldt J Carr AC Tveden-Nyborg P . The pharmacology of vitamin C. Pharmacol Rev. (2025) 77:100043. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmr.2025.100043

18.

Heller R Unbehaun A Schellenberg B Mayer B Werner-Felmayer G Werner ER . L-ascorbic acid potentiates endothelial nitric oxide synthesis via a chemical stabilization of tetrahydrobiopterin. J Biol Chem. (2001) 276:40–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004392200

19.

Chen Q Espey MG Sun AY Lee JH Krishna MC Shacter E et al . Ascorbate in pharmacologic concentrations selectively generates ascorbate radical and hydrogen peroxide in extracellular fluid in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2007) 104:8749–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702854104

20.

Üstündag H Demir Ö Huyut MT Yüce N . Investigating the individual and combined effects of coenzyme Q10 and vitamin C on Clp-induced cardiac injury in rats. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:3098. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-52932-5

21.

Cui YN Tian N Luo YH Zhao JJ Bi CF Gou Y et al . High-dose vitamin C injection ameliorates against sepsis-induced myocardial injury by anti-apoptosis, anti-inflammatory and pro-autophagy through regulating Mapk, Nf-?b and Pi3k/Akt/Mtor signaling pathways in rats. Aging. (2024) 16:6937–53. doi: 10.18632/aging.205735

22.

Han RD Tian N Sun ZG Liu AB Wang S Shen Y et al . Vitamin C protects against myocardial damage induced by sepsis by regulating the Jak2/Stat3 and Nf-?b signaling pathways. J Surg Res. (2025) 314:209–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2025.07.009

23.

Shati AA Zaki MSA Alqahtani YA Al-Qahtani SM Haidara MA Dawood AF et al . Antioxidant activity of vitamin C against Lps-induced septic cardiomyopathy by down-regulation of oxidative stress and inflammation. Curr Issues Mol Biol. (2022) 44:2387–400. doi: 10.3390/cimb44050163

24.

Zhang P Zang M Sang Z Wei Y Yan Y Bian X et al . Vitamin C alleviates Lps-induced myocardial injury by inhibiting pyroptosis via the Ros-Akt/Mtor signalling pathway. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. (2022) 22:561. doi: 10.1186/s12872-022-03014-9

25.

Jiang N Li N Huang J Ning K Zhang H Gou H et al . Impact of vitamin C on inflammatory response and myocardial injury in sepsis patients. Altern Ther Health Med. (2024) 30:427–31. doi: not available.

26.

Rothwell NJ Hopkins SJ . Cytokines and the nervous system II: actions and mechanisms of action. Trends Neurosci. (1995) 18:130–6. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93890-A

27.

Hippensteel JA Anderson BJ Orfila JE McMurtry SA Dietz RM Su G et al . Circulating heparan sulfate fragments mediate septic cognitive dysfunction. J Clin Invest. (2019) 129:1779–84. doi: 10.1172/JCI124485

28.

Subramanian VS Teafatiller T . Effect of lipopolysaccharide and Tnfα on neuronal ascorbic acid uptake. Mediators Inflamm. (2021) 2021:4157132. doi: 10.1155/2021/4157132

29.

Consoli DC Jesse JJ Klimo KR Tienda AA Putz ND Bastarache JA et al . A cecal slurry mouse model of sepsis leads to acute consumption of vitamin C in the brain. Nutrients. (2020) 12:911. doi: 10.3390/nu12040911

30.

Zhang N Zhao W Hu ZJ Ge S Huo Y Liu L et al . Protective effects and mechanisms of high-dose vitamin C on sepsis-associated cognitive impairment in rats. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:14511. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93861-x

31.

Lubis B Lelo A Amelia P Prima A . The effect of thiamine, ascorbic acid, and the combination of them on the levels of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (Mmp-9) and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 (Timp-1) in sepsis patients. Infect Drug Resist. (2022) 15:5741–51. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S378523

32.

May CN Ow CP Pustovit RV Lane DJ Jufar AH Trask-Marino A et al . Reversal of cerebral ischaemia and hypoxia and of sickness behaviour by megadose sodium ascorbate in ovine gram-negative sepsis. Br J Anaesth. (2024) 133:316–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2024.04.058

33.

Schmidt EP Yang Y Janssen WJ Gandjeva A Perez MJ Barthel L et al . The pulmonary endothelial glycocalyx regulates neutrophil adhesion and lung injury during experimental sepsis. Nat Med. (2012) 18:1217–23. doi: 10.1038/nm.2843

34.

Urban C Hayes HV Piraino G Wolfe V Lahni P O'Connor M et al . Colivelin, a synthetic derivative of humanin, ameliorates endothelial injury and glycocalyx shedding after sepsis in mice. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:984298. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.984298

35.

Schmidt EP Li G Li L Fu L Yang Y Overdier KH et al . The circulating glycosaminoglycan signature of respiratory failure in critically ill adults. J Biol Chem. (2014) 289:8194–202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.539452

36.

Kajita Y Terashima T Mori H Islam MM Irahara T Tsuda M et al . A longitudinal change of syndecan-1 predicts risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome and cumulative fluid balance in patients with septic shock: a preliminary study. J Intensive Care. (2021) 9:27. doi: 10.1186/s40560-021-00543-x

37.

Canbolat N Ozkul B Sever IH Sogut I Eroglu E Uyanikgil Y et al . Vitamins C and E protect from sepsis-induced lung damage in rat and Ct correlation. Bratisl Lek Listy. (2022) 123:828–32. doi: 10.4149/BLL_2022_132

38.

Üstündag H Demir Ö Çiçek B Huyut MT Yüce N Tavaci T . Protective effect of melatonin and ascorbic acid combination on sepsis-induced lung injury: an experimental study. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. (2023) 50:634–46. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.13780

39.

Fowler AA III Truwit JD Hite RD Morris PE DeWilde C Priday A et al . Effect of vitamin C infusion on organ failure and biomarkers of inflammation and vascular injury in patients with sepsis and severe acute respiratory failure: the CITRIS-ALI randomized clinical trial. Jama. (2019) 322:1261–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.11825

40.

Qiao X Kashiouris MG . L'Heureux M, Fisher BJ, Leichtle SW, Truwit JD, et al. Biological effects of intravenous vitamin C on neutrophil extracellular traps and the endothelial glycocalyx in patients with sepsis-induced ARDS. Nutrients. (2022) 14:4415. doi: 10.3390/nu14204415

41.

Zhang J Rao X Li Y Zhu Y Liu F Guo G et al . Pilot trial of high-dose vitamin C in critically ill covid-19 patients. Ann Intensive Care. (2021) 11:5. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00792-3

42.

El Driny WA Esmat IM Shaheen SM Sabri NA . Efficacy of high-dose vitamin C infusion on outcomes in sepsis requiring mechanical ventilation: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiol Res Pract. (2022) 2022:4057215. doi: 10.1155/2022/4057215

43.

Zhang X Ji W Deng X Bo L . High-dose ascorbic acid potentiates immune modulation through STAT1 phosphorylation inhibition and negative regulation of Pd-L1 in experimental sepsis. Inflammopharmacology. (2023) 32:537–50. doi: 10.1007/s10787-023-01319-5

44.

Lee SI Kim NY Chung C Park D Kang DH Kim DK et al . Il-6 and Pd-1 antibody blockade combination therapy regulate inflammation and T lymphocyte apoptosis in murine model of sepsis. BMC Immunol. (2025) 26:3. doi: 10.1186/s12865-024-00679-z

45.

Chen Y Guo DZ Zhu C Ren S Sun C Wang Y et al . The implication of targeting Pd-1:Pd-L1 pathway in treating sepsis through immunostimulatory and anti-inflammatory pathways. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1323797. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1323797

46.

Lorencio Cárdenas C Yébenes JC Vela E Clèries M Sirvent JM Fuster-Bertolín C et al . Trends in mortality in septic patients according to the different organ failure during 15 years. Crit Care. (2022) 26:302. doi: 10.1186/s13054-022-04176-w

47.

Takeuchi T Flannery AH Liu LJ Ghazi L Cama-Olivares A Fushimi K et al . Epidemiology of sepsis-associated acute kidney injury in the ICU with contemporary consensus definitions. Crit Care. (2025) 29:128. doi: 10.1186/s13054-025-05351-5

48.

White KC Serpa-Neto A Hurford R Clement P Laupland KB See E et al . Sepsis-associated acute kidney injury in the intensive care unit: incidence, patient characteristics, timing, trajectory, treatment, and associated outcomes. A Multicenter, Observational Study. Intens Care Med. (2023) 49:1079–89. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-2857053/v1

49.

Chen ZD Hu BC Shao XP Hong J Zheng Y Zhang R et al . Ascorbate uptake enables tubular mitophagy to prevent septic AKI by PINK1-PARK2 axis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2021) 554:158–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.03.103

50.

Kim J Stolarski A Zhang Q Wee K Remick D . Hydrocortisone, ascorbic acid, and thiamine therapy decrease renal oxidative stress and acute kidney injury in murine sepsis. Shock. (2022) 58:426–33. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001995

51.

Xu YY Xu CZ Liang YF Jin DQ Ding J Sheng Y et al . Ascorbic acid and hydrocortisone synergistically inhibit septic organ injury via improving oxidative stress and inhibiting inflammation. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. (2022) 44:786–94. doi: 10.1080/08923973.2022.2082978

52.

Hassuna NA Rabie EM Mahd WKM Refaie MMM Yousef RKM Abdelraheem WM . Antibacterial effect of vitamin C against uropathogenic E. coli in vitro and in vivo. BMC Microbiol. (2023) 23:112. doi: 10.1186/s12866-023-02856-3

53.

Amábile-Cuevas CF . Ascorbate and antibiotics, at concentrations attainable in urine, can inhibit the growth of resistant strains of Escherichia Coli cultured in synthetic human urine. Antibiotics. (2023) 12:985. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics12060985

54.

Vandervelden S Cortens B Fieuws S Eegdeman W Malinverni S Vanhove P et al . Early administration of vitamin C in patients with sepsis or septic shock in emergency departments: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled trial: the C-EASIE trial. Crit Care. (2025) 29:160. doi: 10.1186/s13054-025-05383-x

55.

He Y Liu J . Vitamin C Improves 28-day survival in patients with sepsis-associated acute kidney injury in the intensive care unit: a retrospective study. Front Nutr. (2025) 12:1600224. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1600224

56.

McCune TR Toepp AJ Sheehan BE Sherani MSK Petr ST Dodani S . High dose intravenous vitamin C treatment in sepsis: associations with acute kidney injury and mortality. BMC Nephrol. (2021) 22:387. doi: 10.1186/s12882-021-02599-1

57.

Wacker DA Burton SL Berger JP Hegg AJ Heisdorffer J Wang Q et al . Evaluating vitamin C in septic shock: a randomized controlled trial of vitamin C monotherapy. Crit Care Med. (2022) 50:e458–e67. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005427

58.

De Santis P De Fazio C Franchi F Bond O Vincent J Creteur J et al . Incoherence between systemic hemodynamic and microcirculatory response to fluid challenge in critically ill patients. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:507. doi: 10.3390/jcm10030507

59.

Wang D Wang K Liu Q Liu M Zhang G Feng K et al . A novel drug candidate for sepsis targeting heparanase by inhibiting cytokine storm. Adv Sci. (2024) 11:e2403337. doi: 10.1002/advs.202403337

60.

Foote CA Soares RN Ramirez-Perez FI Ghiarone T Aroor A Manrique-Acevedo C et al . Endothelial glycocalyx. Compr Physiol. (2022) 12:3781–811. doi: 10.1002/j.2040-4603.2022.tb00232.x

61.

Soubihe Neto N de Almeida MCV Couto HO Miranda CH . Biomarkers of endothelial glycocalyx damage are associated with microvascular dysfunction in resuscitated septic shock patients. Microvasc Res. (2024) 154:104683. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2024.104683

62.

Belousoviene E Kiudulaite I Pilvinis V Pranskunas A . Links between endothelial glycocalyx changes and microcirculatory parameters in septic patients. Life. (2021) 11:309. doi: 10.3390/life11080790

63.

Belousoviene E Pranskuniene Z Vaitkaitiene E Pilvinis V Pranskunas A . Effect of high-dose intravenous ascorbic acid on microcirculation and endothelial glycocalyx during sepsis and septic shock: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. BMC Anesthesiol. (2023) 23:309. doi: 10.1186/s12871-023-02265-z

64.

Madokoro Y Kamikokuryo C Niiyama S Ito T Hara S Ichinose H et al . Early ascorbic acid administration prevents vascular endothelial cell damage in septic mice. Front Pharmacol. (2022) 13:929448. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.929448

65.

Li W Zhao R Liu S Ma C Wan X . High-dose vitamin C improves norepinephrine level in patients with septic shock: a single-center, prospective, randomized controlled trial. Medicine. (2024) 103:e37838. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000037838

66.

Takeshita N Kawade N Suzuki W Hara S Horio F Ichinose H . Deficiency of ascorbic acid decreases the contents of tetrahydrobiopterin in the liver and the brain of ODS rats. Neurosci Lett. (2020) 715:134656. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2019.134656

67.

Panday S Kar S Kavdia M . How does ascorbate improve endothelial dysfunction? - a computational analysis. Free Rad Biol Med. (2021) 165:111–26. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.01.031

68.

Aisa-Álvarez A Pérez-Torres I Guarner-Lans V Manzano-Pech L Cruz-Soto R Márquez-Velasco R et al . Randomized clinical trial of antioxidant therapy patients with septic shock and organ dysfunction in the ICU: sofa score reduction by improvement of the enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant system. Cells. (2023) 12:1330. doi: 10.3390/cells12091330

69.

Pérez-Torres I Aisa-Álvarez A Casarez-Alvarado S Borrayo G Márquez-Velasco R Guarner-Lans V et al . Impact of treatment with antioxidants as an adjuvant to standard therapy in patients with septic shock: analysis of the correlation between cytokine storm and oxidative stress and therapeutic effects. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:16610. doi: 10.3390/ijms242316610

70.

Lavillegrand JR Raia L Urbina T Hariri G Gabarre P Bonny V et al . Vitamin C improves microvascular reactivity and peripheral tissue perfusion in septic shock patients. Crit Care. (2022) 26:25. doi: 10.1186/s13054-022-03891-8

71.

Wang J Song Q Yang S Wang H Meng S Huang L et al . Effects of hydrocortisone combined with vitamin C and vitamin B1 versus hydrocortisone alone on microcirculation in septic shock patients: a pilot study. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. (2023) 84:111–23. doi: 10.3233/CH-221444

72.

Tang A Shi Y Dong Q Wang S Ge Y Wang C et al . Prognostic value of sublingual microcirculation in sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Intensive Care Med. (2024) 39:1221–30. doi: 10.1177/08850666241253800

73.

Lamontagne F Masse MH Menard J Sprague S Pinto R Heyland DK et al . Intravenous vitamin C in adults with sepsis in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. (2022) 386:2387–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2200644

74.

Rosengrave P Spencer E Williman J Mehrtens J Morgan S Doyle T et al . Intravenous vitamin C administration to patients with septic shock: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Crit Care. (2022) 26:26. doi: 10.1186/s13054-022-03900-w

75.

Mishra PK Kumar A Agrawal S Doneria D Singh R . A comparison of the efficacy of high-dose vitamin c infusion and thiamine (Vitamin B1) infusion in patients with sepsis: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Cureus. (2024) 16:e75296. doi: 10.7759/cureus.75296

76.

Mohamed ZU Prasannan P Moni M Edathadathil F Prasanna P Menon A et al . Vitamin C therapy for routine care in septic shock (victor) trial: effect of intravenous vitamin C, thiamine, and hydrocortisone administration on inpatient mortality among patients with septic shock. Indian J Crit Care Med. (2020) 24:653–61. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23517

77.

Iglesias J Vassallo AV Patel VV Sullivan JB Cavanaugh J Elbaga Y . Outcomes of metabolic resuscitation using ascorbic acid, thiamine, and glucocorticoids in the early treatment of sepsis: the oranges trial. Chest. (2020) 158:164–73. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.02.049

78.

Sharma S Paneru HR Shrestha GS Shrestha PS . Acharya SP. Evaluation of the effects of a combination of vitamin C, thiamine and hydrocortisone vs hydrocortisone alone on ICU outcome in patients with septic shock: a randomized controlled trial. Indian J Crit Care Med. (2024) 28:1147–52. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-24852

79.

Mohamed A Abdelaty M Saad MO Shible A Mitwally H Akkari AR et al . Evaluation of hydrocortisone, vitamin C, and thiamine for the treatment of septic shock: a randomized controlled trial (the HYVITS Trial). Shock. (2023) 59:697–701. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000002110

80.

Lyu QQ Zheng RQ Chen QH Yu JQ Shao J Gu XH . Early administration of hydrocortisone, vitamin C, and thiamine in adult patients with septic shock: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Crit Care. (2022) 26:295. doi: 10.1186/s13054-022-04175-x

81.

Sankar J Manoharan A Lodha R Sharma HP Kabra SK . Vitamin C versus placebo in pediatric septic shock (VITAcIPS) - a randomised controlled trial. J Intensive Care Med. (2025) 24:8850666251362121. doi: 10.1177/08850666251362121

82.

Fujii T Luethi N Young PJ Frei DR Eastwood GM French CJ et al . Effect of vitamin C, hydrocortisone, and thiamine vs hydrocortisone alone on time alive and free of vasopressor support among patients with septic shock: the vitamins randomized clinical trial. Jama. (2020) 323:423–31. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.22176

83.

Zeng Y Liu Z Xu F Tang Z . Intravenous high-dose vitamin C monotherapy for sepsis and septic shock: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine. (2023) 102:e35648. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000035648

84.

Sevransky JE Rothman RE Hager DN Bernard GR Brown SM Buchman TG et al . Effect of vitamin C, thiamine, and hydrocortisone on ventilator- and vasopressor-free days in patients with sepsis: the VICTAS randomized clinical trial. Jama. (2021) 325:742–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.24505

85.

Moskowitz A Huang DT Hou PC Gong J Doshi PB Grossestreuer AV et al . Effect of ascorbic acid, corticosteroids, and thiamine on organ injury in septic shock: the acts randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2020) 324:642–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.11946

86.

Rynne J Mosavie M Masse MH Ménard J Battista MC Maslove DM et al . Sepsis subtypes and differential treatment response to vitamin C: biological sub-study of the LOVIT trial. Intensive Care Med. (2025) 51:82–93. doi: 10.1007/s00134-024-07733-9

87.

Angriman F Muttalib F Lamontagne F Adhikari NKJ . Iv vitamin C in adults with sepsis: a Bayesian reanalysis of a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. (2023) 51:e152–6. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005871

88.

Lauer A Burkard M Niessner H . Ex vivo evaluation of the sepsis triple therapy high-dose vitamin C in combination with vitamin B1 and hydrocortisone in a human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCS) model. Nutrients. (2021) 13:2366. doi: 10.3390/nu13072366

89.

Liu XQ Lin QM Zhang CW Zhang HL Li MJ Li RY et al . Vitamin C inhibits LPS-induced secretion of inflammatory cytokines in peripheral blood. Pak J Pharm Sci. (2025) 38:249–59. doi: 10.36721/PJPS.2025.38.1.REG.249-259.1

90.

Härtel C Strunk T Bucsky P Schultz C . Effects of vitamin C on intracytoplasmic cytokine production in human whole blood monocytes and lymphocytes. Cytokine. (2004) 27:101–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2004.02.004

91.

Schmidt T Kahn R Kahn F . Ascorbic acid attenuates activation and cytokine production in sepsis-like monocytes. J Leukoc Biol. (2022) 112:491–8. doi: 10.1002/JLB.4AB0521-243R

92.

Lee ZY Ortiz-Reyes L Lew CCH Hasan MS Ke L Patel JJ et al . Intravenous vitamin C monotherapy in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials with trial sequential analysis. Ann Intensive Care. (2023) 13:14. doi: 10.1186/s13613-023-01116-x

93.

Liang B Su J Shao H Chen H Xie B . The outcome of IV vitamin C therapy in patients with sepsis or septic shock: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care. (2023) 27:109. doi: 10.1186/s13054-023-04392-y

94.

Cheng ZL Zhang S Wang Z Song A Gao C Song JB et al . Pathogen-derived glyoxylate inhibits Tet2 DNA dioxygenase to facilitate bacterial persister formation. Cell Metab. (2025) 37:1137–51.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2025.01.019

95.

Fowler AA III Syed AA Knowlson S Sculthorpe R Farthing D DeWilde C et al . Phase I safety trial of intravenous ascorbic acid in patients with severe sepsis. J Transl Med. (2014) 12:32. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-12-32

96.

Kumar S Gupta E Kaushik S Kumar Srivastava V Mehta SK Jyoti A . Evaluation of oxidative stress and antioxidant status: correlation with the severity of sepsis. Scand J Immunol. (2018) 87:e12653. doi: 10.1111/sji.12653

97.

Lee WJ Chen YL Chu YW Chien DS . Comparison of glutathione peroxidase-3 protein expression and enzyme bioactivity in normal subjects and patients with sepsis. Clin Chim Acta. (2019) 489:177–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2017.10.031

98.

Üstündag H Doganay S Kalindemirtaş FD Demir Ö Huyut MT Kurt N et al . A new treatment approach: melatonin and ascorbic acid synergy shields against sepsis-induced heart and kidney damage in male rats. Life Sci. (2023) 329:121875. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2023.121875

99.

Liu P Feng Y Li H Chen X Wang G Xu S et al . Ferrostatin-1 alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury via inhibiting ferroptosis. Cell Mol Biol Lett. (2020) 25:10. doi: 10.1186/s11658-020-00205-0

100.

Li N Wang W Zhou H Wu Q Duan M Liu C et al . Ferritinophagy-mediated ferroptosis is involved in sepsis-induced cardiac injury. Free Radic Biol Med. (2020) 160:303–18. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.08.009

101.

Sae-Khow K Tachaboon S Wright H Edwards S Srisawat N Leelahavanichkul A et al . Defective neutrophil function in patients with sepsis is mostly restored by ex vivo ascorbate incubation. J Inflamm Res. (2020) 13:263–74. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S252433

102.

Wigerblad G Kaplan MJ . Neutrophil extracellular traps in systemic autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. (2023) 23:274–88. doi: 10.1038/s41577-022-00787-0

103.

Sha HX Liu YB Qiu YL Zhong WJ Yang NS Zhang CY et al . Neutrophil extracellular traps trigger alveolar epithelial cell necroptosis through the CGAS-Sting pathway during acute lung injury in mice. Int J Biol Sci. (2024) 20:4713–30. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.99456

104.

Guo W Gong Q Zong X Wu D Li Y Xiao H et al . GPR109A controls neutrophil extracellular traps formation and improve early sepsis by regulating ROS/PAD4/Cit-H3 signal axis. Exp Hematol Oncol. (2023) 12:15. doi: 10.1186/s40164-023-00376-4

105.

Margraf S Lögters T Reipen J Altrichter J Scholz M Windolf J . Neutrophil-derived circulating free DNA (Cf-DNA/Nets): a potential prognostic marker for posttraumatic development of inflammatory second hit and sepsis. Shock. (2008) 30:352–8. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31816a6bb1

106.

Maneta E Aivalioti E Tual-Chalot S Emini Veseli B Gatsiou A Stamatelopoulos K et al . Endothelial dysfunction and immunothrombosis in sepsis. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1144229. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1144229

107.

Meyer NJ Prescott HC . Sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. (2024) 391:2133–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2403213

108.

Chen P Reed G Jiang J Wang Y Sunega J Dong R et al . Pharmacokinetic evaluation of intravenous vitamin C: a classic pharmacokinetic study. Clin Pharmacokinet. (2022) 61:1237–49. doi: 10.1007/s40262-022-01142-1

109.

Lykkesfeldt J Tveden-Nyborg P . The pharmacokinetics of vitamin C. Nutrients. (2019) 11:2412. doi: 10.3390/nu11102412

110.

Hudson EP Collie JT Fujii T Luethi N Udy AA Doherty S et al . Pharmacokinetic data support 6-hourly dosing of intravenous vitamin C to critically ill patients with septic shock. Crit Care Resusc. (2019) 21:236–42. doi: 10.1016/S1441-2772(23)00548-3

111.

Kim OH Kim TW Kang H Jeon TJ Chang ES Lee HJ et al . Early, very high-dose, and prolonged vitamin C administration in murine sepsis. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:17513. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-02622-7

112.

de Grooth HJ Manubulu-Choo WP Zandvliet AS . Spoelstra-de Man AME, Girbes AR, Swart EL, et al. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics in critically ill patients: a randomized trial of four IV regimens. Chest. (2018) 153:1368–77. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.02.025

113.

Hemilä H Chalker E . Abrupt termination of vitamin C from ICU patients may increase mortality: secondary analysis of the LOVIT trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. (2023) 77:490–4. doi: 10.1038/s41430-022-01254-8

114.

Seymour CW Kennedy JN Wang S Chang CH Elliott CF Xu Z et al . Derivation, validation, and potential treatment implications of novel clinical phenotypes for sepsis. JAMA. (2019) 321:2003–17. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.5791

115.

You SH Kweon OJ Jung SY Baek MS Kim WY . Patterns of inflammatory immune responses in patients with septic shock receiving vitamin C, hydrocortisone, and thiamine: clustering analysis in Korea. Acute Crit Care. (2023) 38:286–97. doi: 10.4266/acc.2023.00507

116.

Kim WY Jung JW Choi JC Shin JW Kim JY . Subphenotypes in patients with septic shock receiving vitamin C, hydrocortisone, and thiamine: a retrospective cohort analysis. Nutrients. (2019) 11:2976. doi: 10.3390/nu11122976

117.

Medeiros PMC Schjalm C Christiansen D Sokolova M Pischke SE Würzner R et al . Vitamin C, Hydrocortisone, and the combination thereof significantly inhibited two of nine inflammatory markers induced by Escherichia coli but not by Staphylococcus aureus- when incubated in human whole blood. Shock. (2021) 57:72–80. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001834

Summary

Keywords

sepsis, septic shock, vitamin C, ascorbic acid, mechanism

Citation

Xiao Y, Gong F, Zhang L and Gui C (2025) Vitamin C for sepsis: from mechanisms to individualized therapy. Front. Med. 12:1700351. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1700351

Received

06 September 2025

Revised

18 November 2025

Accepted

27 November 2025

Published

18 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Amit Prasad, Indian Institute of Technology Mandi, India

Reviewed by

Margreet C. M. Vissers, University of Otago, New Zealand

Yuchang Wang, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Xiao, Gong, Zhang and Gui.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chunmei Gui, g19936865822@outlook.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.