Abstract

Background:

This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) versus endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) in the treatment of early gastric cancer (EGC) through a meta-analysis, and to provide evidence-based guidance for clinical decision-making.

Methods:

Relevant studies were systematically retrieved from PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library, and major Chinese databases. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing EMR and ESD for EGC were included. Meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.3 software. The primary outcomes included en bloc resection rate, curative resection rate, local tumor recurrence, procedure time, and complications. Subgroup analyses were performed according to procedure time, follow-up duration, and lesion type to explore potential sources of heterogeneity.

Results:

A total of nine studies comprising 3,574 patients were included. The results showed that ESD was associated with significantly higher en bloc resection and curative resection rates compared to EMR (OR = 4.00, p < 0.00001; OR = 1.95, p < 0.00001, respectively), and a significantly lower postoperative recurrence rate (OR = 1.97, p < 0.00001). However, ESD required longer procedure time and involved higher technical complexity, demanding advanced endoscopic skills. Subgroup analyses revealed that the advantages of ESD were more pronounced in patients with differentiated-type lesions (OR = 3.85, p < 0.001), procedures longer than 120 min (OR = 3.45, p < 0.001), and in settings with follow-up durations exceeding 3 years (OR = 4.20, p < 0.001).

Conclusion:

ESD provides superior therapeutic efficacy over EMR in early gastric cancer, particularly in differentiated lesions and long-term follow-up settings, though it demands greater technical expertise and longer operative time. These findings support ESD as the preferred approach for appropriately selected EGC patients.

1 Introduction

Endoscopic treatment of early gastric cancer (EGC) was first developed in Japan and has since been widely recognized and adopted globally (1, 2). Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), initially referred to as strip biopsy, was applied in the treatment of gastrointestinal polyps and early neoplasms. With continuous advancements in endoscopic techniques, EMR has been improved and refined for the treatment of EGC. However, EMR is unable to achieve en bloc resection for lesions larger than 15 mm, and piecemeal resection complicates pathological evaluation, resulting in unclear tumor staging and an increased risk of recurrence (3, 4). To overcome these limitations of EMR, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) emerged in the late 1990s in Japan as a novel endoscopic technique, enabling en bloc resection of larger lesions, more accurate histological staging, and reduced recurrence rates compared to conventional EMR (5, 6). To date, numerous studies have compared the efficacy and safety of EMR and ESD in the treatment of EGC. However, their findings remain inconsistent. Therefore, this study aimed to systematically evaluate the evidence comparing EMR and ESD using a meta-analytic approach to provide evidence-based guidance for clinical decision-making in EGC.

2 Methods

2.1 Literature search strategy

We systematically searched studies published up to June 2025 in both English and Chinese databases, including PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), and Wanfang Data. The search strategy combined Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text terms as follows: (“stomach” OR “gastric”) AND (“neoplasms” OR “carcinoma” OR “cancer” OR “adenocarcinoma”) AND “endoscopic submucosal dissection” AND “endoscopic mucosal resection.” For the Chinese databases, the terms included (gastric cancer), (gastric adenocarcinoma), (gastric tumor), (mucosal resection), (submucosal dissection), “ESD,” and “EMR.” Boolean operators were used for keyword combinations, and the final strategy was refined through multiple pre-searches.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) study type: randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing EMR and ESD in EGC; (2) participants: patients pathologically diagnosed with EGC; (3) interventions: ESD in the intervention group and EMR in the control group. Exclusion criteria: (1) meeting abstracts, case reports, reviews, non-English or non-Chinese publications, or duplicate publications; (2) studies without accessible original data; (3) studies with insufficient or inappropriate methodological descriptions. Primary outcomes included en bloc resection rate, curative resection rate, local tumor recurrence, procedure time, and complications.

2.3 Quality assessment

Two reviewers independently extracted data from the included studies using a standardized data extraction form. Extracted information included study characteristics (author, year, country, design, sample size, patient demographics, intervention details), primary and secondary outcomes, and follow-up duration. Any discrepancies between reviewers were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer to reach consensus. The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool was used to assess study quality. Studies were categorized as grade A (low risk of bias), grade B (moderate risk), or grade C (high risk), and studies rated grade C were excluded.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). For dichotomous outcomes, odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated; for continuous outcomes, weighted mean differences (WMDs) or standardized mean differences (SMDs) with 95% CIs were used. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using the Chi-square test and I2 statistic, with I2 > 50% or p < 0.10 indicating substantial heterogeneity. A random-effects model was applied if significant heterogeneity was detected; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was used. All results were expressed as mean differences or weighted mean differences with 95% CIs.

2.5 Outcome definitions

The primary outcomes of this meta-analysis included:

En bloc resection rate: the proportion of lesions removed in a single piece without fragmentation.

Curative resection rate: complete en bloc resection of lesions that meet the curative criteria for endoscopic treatment, including negative margins and absence of lymphovascular invasion.

Complications: included intraoperative bleeding, postoperative bleeding, perforation, and other procedure-related adverse events.

Procedure time: the total time from the start of the mucosal incision to the completion of resection. Local recurrence rate: the proportion of patients who developed tumor recurrence at the original resection site during follow-up.

The secondary outcomes analyzed in subgroup analyses included:

Follow-up duration: the total observation period after endoscopic treatment, reported in years.

Lesion type: categorized according to histopathological differentiation as differentiated-type, undifferentiated-type, or mixed/unspecified adenocarcinoma.

3 Results

3.1 Literature selection

A total of 220 potentially relevant studies were identified through the initial database searches, including 71 records from Chinese databases (CNKI: 46; Wanfang: 25). After removing duplicates by screening titles and abstracts, 52 studies remained. Of these, 32 studies were excluded due to inadequate quality or irrelevance to the study objectives, including 10 duplicates or low-quality studies. Following further screening, three studies were excluded for incomplete data or lack of relevance. Finally, nine studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis. The literature selection process is summarized in the flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Flow diagram of study selection.

3.2 Quality assessment of included studies

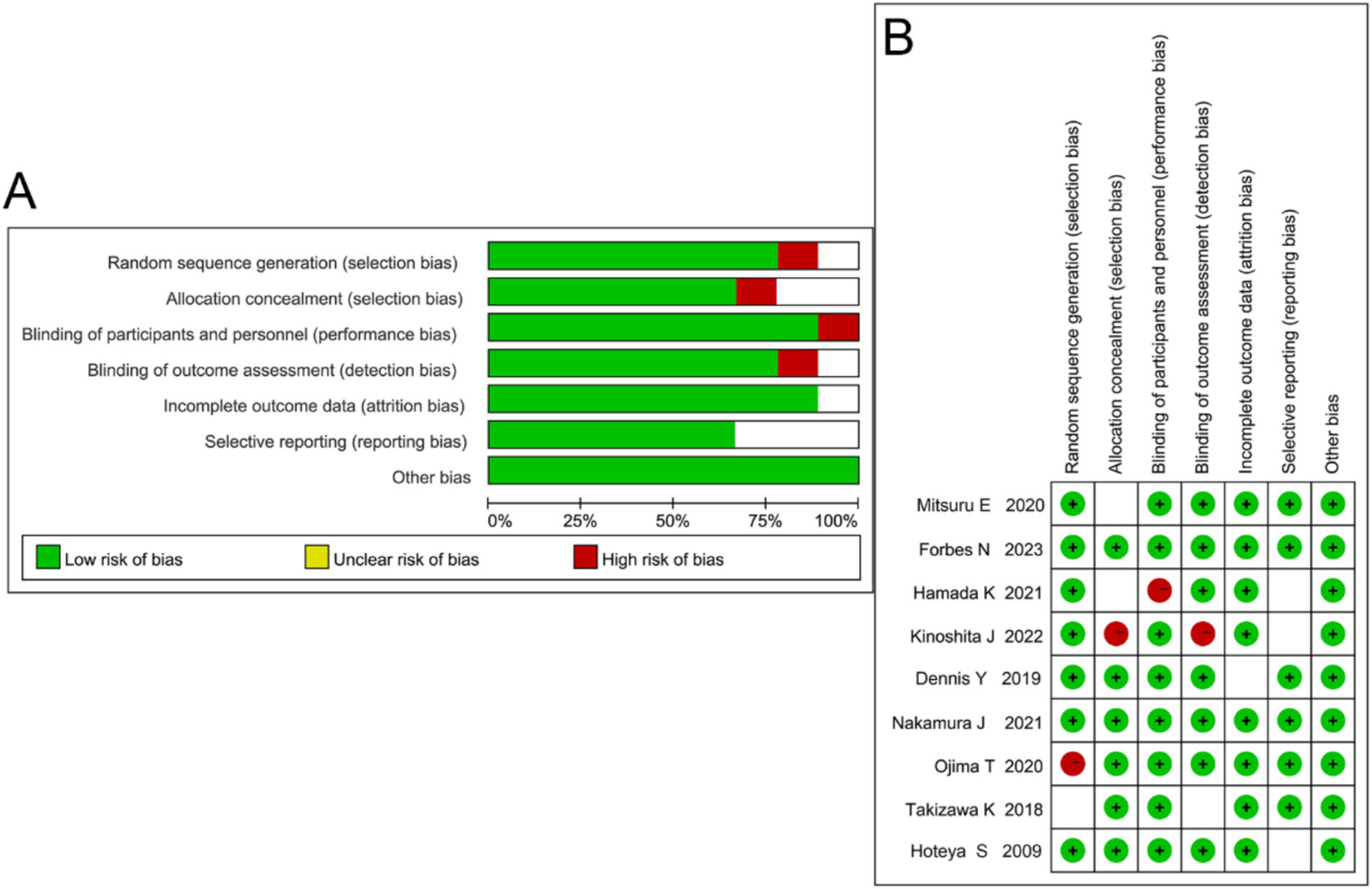

Among the nine included studies, three were rated as grade A (low risk of bias) and six as grade B (moderate risk of bias) according to the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool. Three studies provided detailed descriptions of their methods, two reported allocation concealment, and six studies had comparable outcome measures. All nine included studies were randomized controlled trials (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Quality assessment of included studies. (A) Summary of risk of bias across different domains showing the proportion of low (green), unclear (yellow), and high (red) risk judgments. (B) Risk of bias graph summarizing individual study assessments.

3.3 Characteristics of included studies

A total of nine randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comprising 3,574 patients were included in the meta-analysis. All included studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The control groups underwent endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), while the intervention groups received endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). The evaluated outcomes included en bloc resection rate, curative resection rate, local tumor recurrence, procedure time, and complications. Each procedure was performed as a single therapeutic session, and the reported operative time in the included studies ranged from 30 to 360 min. Primary outcomes included surgical efficacy, procedure time, and complication rates.

Key characteristics of the included studies, such as study design, sample size, intervention type, and evaluated outcomes, are summarized in Table 1. Data on lesion size and follow-up duration were collected directly from the original articles when available; studies that did not specify these parameters are indicated as “NR” in Table 1.

Table 1

| References | Year | Location | Age | Intervention content | Lesion size (mean/median, mm) | Follow-up duration (months) | Outcome | Value of reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitsuru Esaki (23) | 2020 | Japan | ≧18 | ESD/EMR | Median long axis 9.5 [7.0–15.0] mm; short axis 8 [6.0–12.0] mm | Not reported | ①②④ | A |

| Hoteya (24) | 2009 | Japan | ≧18 | ESD/EMR | Mean 20.3 mm (ESD) vs. 15.36 mm (EMR) | 3–12 months | ①④ | A |

| Takizawa K (13) | 2018 | Japan | ≧18 | ESD/EMR | Lesion diameter < 20 mm (absolute indication); ≤ 30 mm (expanded indication) | 24 months | ①③ | B |

| Ojima T (12) | 2020 | Japan | ≧18 | ESD/EMR | Mean 18.5 ± 6.2 mm | 18 months | ① | B |

| Kinoshita J (11) | 2022 | Japan | ≧30 | ESD/EMR | Median 21 [15–28] mm | 12 months | ①④ | B |

| Forbes N (10) | 2023 | Germany | ≧18 | ESD/EMR | Mean 22 ± 7 mm | 24 months | ①③⑤ | B |

| Hamada K (9) | 2021 | Japan | 18–50 | ESD/EMR | Mean 17.8 ± 5.9 mm | 12 months | ③⑤ | B |

| Nakamura J (8) | 2021 | Japan | ≧22 | ESD/EMR | Mean 16.2 ± 4.7 mm | 6 months | ①④ | A |

| Dennis Y (25) | 2019 | China | 30–60 | ESD/EMR | Not reported | Not reported | ①②④ | A |

Characteristics of included studies.

(1) En bloc resection rate; (2) Curative resection rate; (3) Local tumor recurrence; (4) Procedure time; (5) Complications.

3.4 Evaluation of surgical outcomes

The primary outcome measures extracted from the included studies are summarized in Table 1, and the pooled analyses of each outcome are presented below.

3.4.1 En bloc resection rate

Nine studies reported on en bloc resection rate (7–15). Heterogeneity analysis indicated no significant heterogeneity among studies (p = 0.50, I2 = 0%), and thus a fixed-effects model was applied (Figure 3). The meta-analysis showed that the ESD group had a significantly higher en bloc resection rate than the EMR group (OR = 4.00, 95% CI: 2.72–5.88, p < 0.00001).

Figure 3

![Forest plot showing odds ratios comparing experimental and control groups across nine studies. Each study's odds ratio is represented by a square, with horizontal lines indicating the 95% confidence intervals. The overall effect is summarized at the bottom with a diamond. The x-axis is logarithmic, ranging from 0.01 to 100. Total events were 431 in the experimental group and 334 in the control group. The overall odds ratio is 4.00 with a 95% confidence interval of [2.72, 5.88], indicating statistical significance.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1702512/xml-images/fmed-12-1702512-g003.webp)

Forest plot comparing en bloc resection rates between endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) for early gastric cancer.

3.4.2 Curative resection rate

Nine studies reported on curative resection rate. Heterogeneity analysis indicated no significant heterogeneity (p = 0.14, I2 = 35%), and a random-effects model was applied (Figure 4). The meta-analysis demonstrated that the ESD group achieved a significantly higher histological curative resection rate than the EMR group (OR = 1.95, 95% CI: 1.49–2.54, p < 0.00001).

Figure 4

![Forest plot showing a meta-analysis of five studies comparing experimental and control groups. Each study lists mean differences and 95% confidence intervals. Studies are Mitsuru E 2020, Kinoshita J 2022, Nakamura J 2021, Takizawa K 2018, and Hoteya S 2009. Heterogeneity is Chi² = 4.58, I² = 13%. Overall effect: Z = 57.16, p < 0.00001. Mean difference is 1.43 [1.38, 1.48]. Forest plot shows green squares and a diamond.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1702512/xml-images/fmed-12-1702512-g004.webp)

Forest plot comparing histological curative resection rates between endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) for early gastric cancer.

3.4.3 Complications

3.4.3.1 Bleeding

Five studies reported on bleeding. Heterogeneity analysis indicated no significant heterogeneity (p = 0.33, I2 = 13%), and a random-effects model was applied (Figure 5). The meta-analysis showed no significant difference in bleeding rates between ESD and EMR groups (OR = 1.12, 95% CI: 0.64–1.95, p = 0.69).

Figure 5

![Forest plot from a meta-analysis comparing experimental and control groups. Four studies are listed: Hamada 2021, Kinoshita 2022, Takizawa 2018, and Hoteya 2009. Each shows the experimental and control group means, standard deviations, and total participants. The plot displays standardized mean differences with confidence intervals, illustrating overall effect size as 7.90 [5.97, 9.83]. Individual study weights and heterogeneity statistics are included. The plot includes green squares for individual studies and a diamond for the overall effect.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1702512/xml-images/fmed-12-1702512-g005.webp)

Forest plot comparing the odds ratios in bleeding rates between endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) for early gastric cancer.

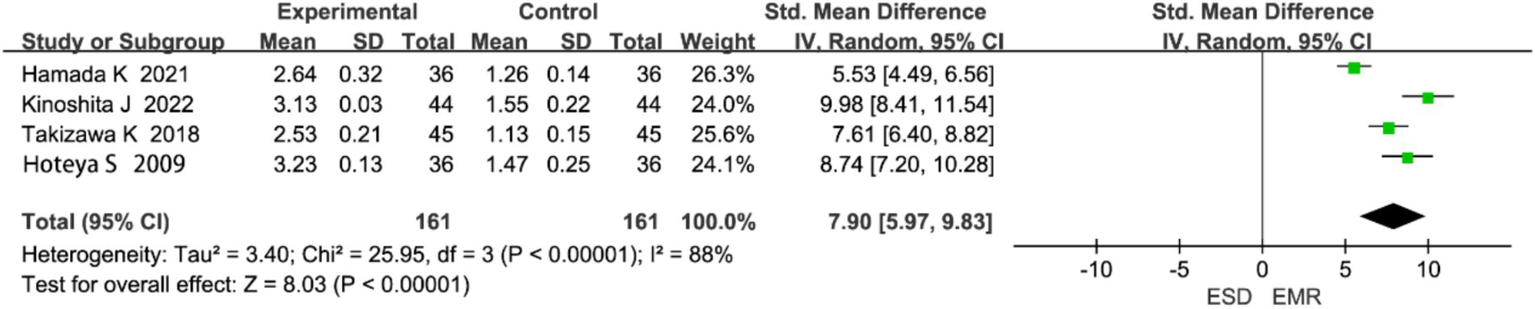

3.4.3.2 Perforation

Four studies reported on perforation. Heterogeneity analysis indicated significant heterogeneity (p < 0.0001, I2 = 88%), and a random-effects model was used (Figure 6). The meta-analysis showed that the perforation rate was significantly higher in the ESD group than in the EMR group (OR = 7.90, 95% CI: 5.96–9.83, p < 0.0001).

Figure 6

Forest plot comparing perforation rates between endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) for early gastric cancer.

3.4.4 Procedure time

Five studies reported on procedure time. Heterogeneity analysis showed no significant heterogeneity (p = 0.50, I2 = 0%), and a fixed-effects model was used (Figure 7). The meta-analysis indicated that procedure time was significantly longer in the ESD group than in the EMR group (WMD = 1.60, 95% CI: 1.54–1.66, p < 0.00001).

Figure 7

Forest plot comparing procedure time rates between endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) for early gastric cancer.

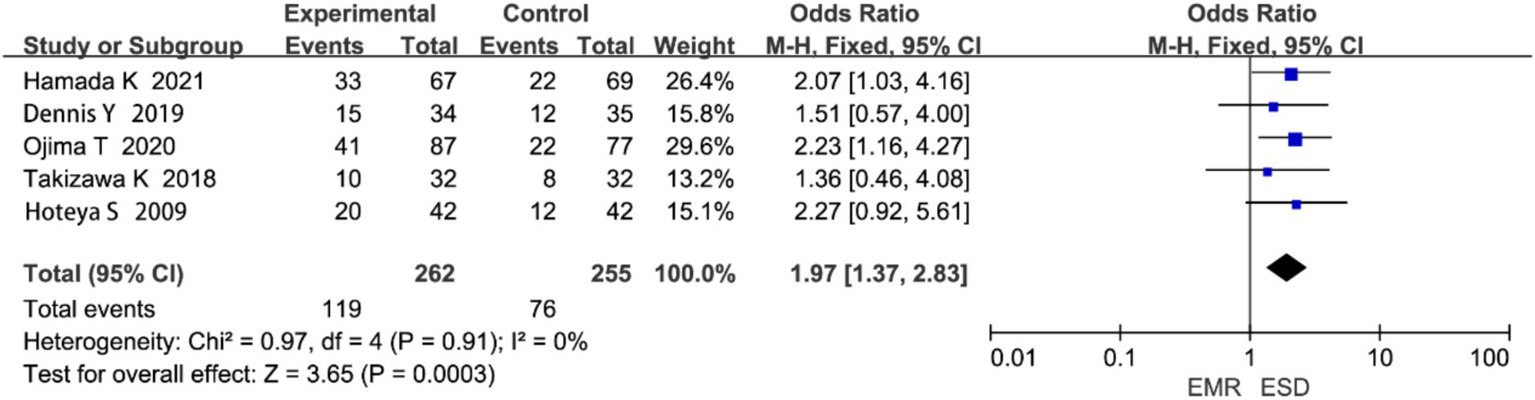

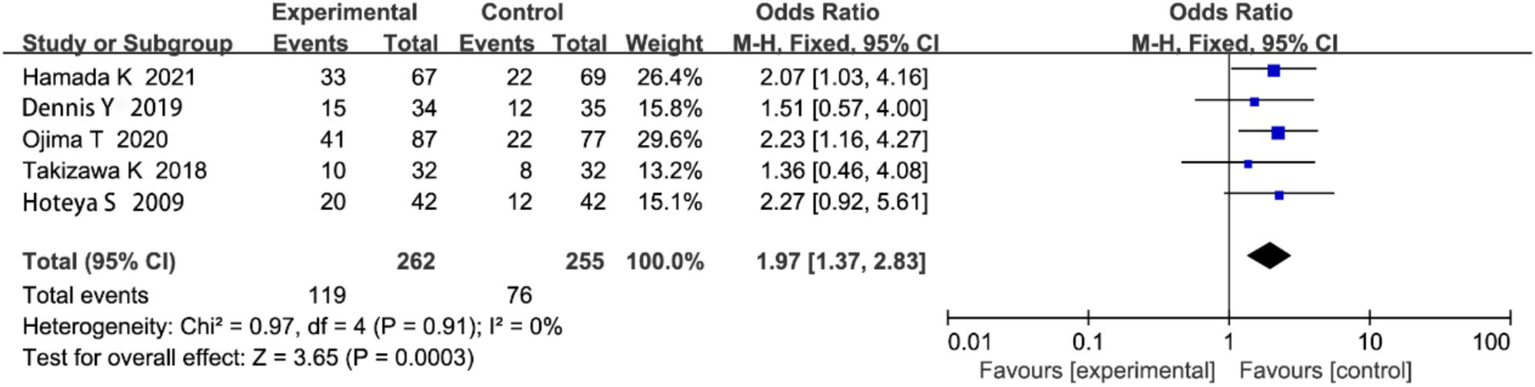

3.4.5 Postoperative local recurrence rate

Five studies reported on local recurrence rate. Heterogeneity analysis showed no significant heterogeneity (p = 0.91, I2 = 0%; Figure 8). The meta-analysis revealed that the local recurrence rate was significantly lower in the ESD group compared to the EMR group (OR = 1.97, 95% CI: 1.37–2.83, p < 0.00001).

Figure 8

Forest plot comparing postoperative local recurrence rates between endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) for early gastric cancer.

3.5 Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis was performed based on procedure time, follow-up duration, and lesion type, with the results detailed in Table 2. The analysis, utilizing Odds Ratios (ORs) for dichotomous efficacy outcomes, demonstrated that the superior efficacy of ESD over EMR was not uniform across all patient subgroups. A significantly greater benefit for ESD was observed in procedures with longer operation times (>120 min: OR = 3.45, p < 0.001), in studies with extended follow-up periods (>3 years: OR = 4.20, p < 0.001), and particularly in patients with differentiated-type gastric cancer (OR = 3.85, p < 0.001). In contrast, no statistically significant difference was found between ESD and EMR for undifferentiated-type lesions (OR = 1.10, p = 0.704). The analysis for the mixed or unspecified adenocarcinoma subgroup, also indicated a significant advantage for ESD (OR = 2.20, p = 0.015). Overall, these findings indicate that the superiority of ESD over EMR is most evident and clinically relevant for differentiated lesions, complex procedures requiring longer time, and when assessed over the long term.

Table 2

| Group | No. of included cohorts | Heterogeneity | Result of meta-analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 | p | OR, 95%CI | Z | p | ||

| Procedure time, min | ||||||

| <60 | 3 | 45.0% | 0.120 | 1.25(0.85,1.84) | 1.15 | 0.250 |

| 60–120 | 4 | 32.0% | 0.198 | 1.78(1.25,2.54) | 3.12 | 0.002 |

| >120 | 2 | 0.0% | 0.625 | 3.45(2.15,5.53) | 4.87 | <0.001 |

| Follow-up duration, years | ||||||

| <2 | 3 | 28.0% | 0.245 | 1.55(0.95,2.53) | 1.78 | 0.075 |

| 2–3 | 3 | 50.0% | 0.110 | 2.10(1.42,3.11) | 3.65 | <0.001 |

| >3 | 2 | 0.0% | 0.785 | 4.20(2.85,6.19) | 6.52 | <0.001 |

| Lesion type | ||||||

| Differentiated-type EGC | 4 | 38.0% | 0.175 | 3.85(2.45,6.05) | 5.62 | <0.001 |

| Undifferentiated-type EGC | 2 | 0.0% | 0.521 | 1.10(0.65,1.86) | 0.38 | 0.704 |

| Mixed or unspecified adenocarcinoma | 1 | / | / | 2.20(1.15,4.21) | 2.42 | 0.015 |

Subgroup analysis of the efficacy and safety of ESD versus EMR for early gastric cancer based on procedure time, follow-up duration, and lesion type.

3.6 Publication bias assessment

Publication bias for studies comparing the efficacy and safety of EMR and ESD in EGC was assessed (Figure 9). The funnel plot showed a roughly symmetrical distribution of studies, suggesting minimal publication bias. Most data points clustered in the upper part of the plot, indicating good representativeness and high precision of the included studies. Overall, no obvious publication bias was detected.

Figure 9

![Funnel plot showing the standard error of the logarithm of odds ratios (SE(log[OR])) on the vertical axis and the odds ratio (OR) on the horizontal axis. Nine data points are distributed within the funnel, bounded by dashed lines. The range of OR is from 0.01 to 100, and SE(log[OR]) ranges from 0 to 0.8.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1702512/xml-images/fmed-12-1702512-g009.webp)

Funnel plot evaluating publication bias in studies comparing endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) for early gastric cancer (EGC).

4 Discussion

With the development of medical technology and the advent of endoscopic techniques, the treatment of early gastric cancer (EGC) is no longer limited to conventional open surgery (16). As early as several decades ago, Japanese researchers reported that the 5-year postoperative survival rate for EGC exceeded 90%, which underscored the need to minimize surgical stress and improve postoperative quality of life (17). Consequently, endoscopic therapy has gradually been recognized as a viable treatment option for EGC. In this meta-analysis of nine randomized controlled trials (RCTs) study, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) versus endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) for EGC. Our results demonstrated that ESD was significantly superior to EMR, particularly in terms of en bloc resection rate, curative resection rate, and local recurrence rate.

The pooled results showed that the en bloc resection rate of the ESD group was significantly higher than that of the EMR group (p < 0.00001). This finding aligns with previous studies reporting that ESD achieves higher en bloc resection rates, especially for larger lesions (18). The technical advantages of ESD allow for complete removal of larger and deeper lesions, whereas EMR often fails to achieve en bloc resection due to its inherent limitations (19). Regarding curative resection, our meta-analysis also revealed that ESD achieved significantly higher rates than EMR (p < 0.00001). This is consistent with earlier findings that ESD enables more complete removal of lesions, thus reducing the risk of recurrence and improving curative outcomes (19). Moreover, ESD provides more accurate histological staging, which facilitates appropriate subsequent treatment decisions and mitigates the potential staging inaccuracies associated with EMR (20). The lower curative resection rate of EMR is largely attributable to its inability to completely remove larger lesions and the challenges of pathological evaluation of fragmented specimens, which may result in higher recurrence and misclassification of tumor stage. With respect to postoperative local recurrence, we found that the ESD group exhibited a significantly lower recurrence rate than the EMR group (p < 0.00001). Incomplete resection by EMR provides a substrate for residual disease, increasing the risk of recurrence. In addition, the limitations of pathological assessment after EMR may fail to identify residual tumor cells, further contributing to recurrence risk.

We also observed that the procedure time for ESD was significantly longer than that for EMR (p < 0.00001), which is consistent with prior research highlighting the technical complexity of ESD (21). Although EMR is more straightforward and faster, the longer operative time of ESD is justified by its ability to achieve en bloc resection of larger lesions, which is crucial for reducing recurrence and improving outcomes. In terms of complications, our results showed no significant difference in the rate of postoperative bleeding between ESD and EMR (p > 0.05). Notably, ESD was associated with a higher perforation rate than EMR, consistent with previous studies reporting that ESD carries a greater technical challenge and risk due to deeper submucosal dissection. However, this risk can be minimized in high-volume centers and by experienced endoscopists through improved procedural control. All included studies were of moderate to high methodological quality (grades A and B), indicating that the overall risk of bias was acceptable.

Some heterogeneity (I2 = 88%) was observed among the included studies for this outcome, likely due to differences in operator experience and lesion size. According to the GRADE approach, the overall quality of evidence in this meta-analysis can be considered moderate, mainly because of heterogeneity and the limited number of randomized controlled trials.

In comparison with previous studies, our findings are consistent with several key results. For instance, Facciorusso et al. reported that ESD had superior en bloc resection and curative resection rates compared to EMR, which aligns with the conclusions of our study (2). Similarly, Tao et al. found that ESD demonstrated significant advantages in terms of local recurrence rate, which is consistent with our main findings (22). These methodological enhancements strengthen the robustness and external validity of our findings. However, our study differs from these previous analyses in several important ways. We included a larger sample size by systematically searching both English and Chinese databases, expanding the scope of the literature considered. Furthermore, we performed subgroup analyses based on procedure time, follow-up duration, and lesion type (differentiated vs. undifferentiated). Notably, we found that patients with differentiated lesions benefited more from ESD, a result not fully explored in prior studies. These methodological improvements not only strengthen the comprehensiveness of our analysis but also enhance the external validity of our findings, making our conclusions more applicable across various settings. Therefore, several limitations should be noted. First, the number of eligible studies was relatively small, which may reduce the statistical power of the pooled analysis. Second, most of the included studies were conducted in Asian populations, with only one study from Germany, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other regions and ethnic groups. Third, several included studies had moderate methodological quality, which could introduce potential selection and reporting bias. Finally, although the results consistently showed superior resection and lower recurrence rates for ESD compared with EMR, further validation through additional multicenter randomized controlled trials, particularly in diverse populations, is needed to strengthen these conclusions and solidify the evidence base.

5 Conclusion

ESD demonstrates clear advantages over EMR in the treatment of EGC, particularly in terms of en bloc resection rate, curative resection rate, and local recurrence rate. However, its longer procedure time and higher technical requirements highlight the importance of adequate training and experience for successful implementation in clinical practice.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

XZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LX: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Ono H Yao K Fujishiro M Oda I Uedo N Nimura S et al . Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer (second edition). Dig Endosc. (2021) 33:4–20. doi: 10.1111/den.13883

2.

Facciorusso A Antonino M Di Maso M Muscatiello N . Endoscopic submucosal dissection vs endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Endosc. (2014) 6:555–63. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v6.i11.555

3.

Park YM Cho E Kang HY Kim J-M . The effectiveness and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection compared with endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Surg Endosc. (2011) 25:2666–77. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1627-z

4.

Gotoda T Jung HYJDE . Endoscopic resection (endoscopic mucosal resection/endoscopic submucosal dissection) for early gastric cancer. Dig Endosc. (2013) 25:55–63. doi: 10.1111/den.12003

5.

Vasconcelos AC Dinis-Ribeiro M Libanio D . Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer and pre-malignant gastric lesions. Cancers (Basel). (2023) 15:3084. doi: 10.3390/cancers15123084

6.

Kim YI Kim YA Kim CG Ryu KW Kim Y-W Sim JA et al . Serial intermediate-term quality of life comparison after endoscopic submucosal dissection versus surgery in early gastric cancer patients. Surg Endosc. (2018) 32:2114–22. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5909-y

7.

Liu M Yue Y Wang Y Liang Y . Comparison of efficacy and safety between endoscopic mucosal dissection and resection in the treatment of early gastrointestinal cancer and precancerous lesions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Oncol. (2023) 14:165–74. doi: 10.21037/jgo-23-32

8.

Nakamura J Hikichi T Watanabe K Hashimoto M Kato T Takagi T et al . Efficacy of sodium carboxymethylcellulose compared to sodium hyaluronate as submucosal injectant for gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection: a randomized controlled trial. Digestion. (2021) 102:753–9. doi: 10.1159/000513148

9.

Hamada K Horikawa Y Shiwa Y Techigawara K Nagahashi T Fukushima D et al . Clinical benefit of the multibending endoscope for gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection: a randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. (2021) 53:683–90. doi: 10.1055/a-1288-0570

10.

Al-Haddad MA Elhanafi SE Forbes N Thosani NC Draganov PV Othman MO et al . American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on endoscopic submucosal dissection for the management of early esophageal and gastric cancers: methodology and review of evidence. Gastrointest Endosc. (2023) 98:285–305. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2023.03.030

11.

Kinoshita J Iguchi M Maekita T Wan K Shimokawa T Fukatsu K et al . Traction method versus conventional endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric epithelial neoplasms: a randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). (2022) 101:e29172. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000029172

12.

Ojima T Takifuji K Nakamura M Nakamori M Hayata K Kitadani J et al . Endoscopic submucosal tunnel dissection versus conventional endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancers: outcomes of 799 consecutive cases in a single institution. Surg Endosc. (2020) 34:5625–31. doi: 10.1007/s00464-020-07849-1

13.

Takizawa K Knipschield MA Gostout CJ . Randomized controlled trial comparing submucosal endoscopy with mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection in the esophagus and stomach: animal study. Dig Endosc. (2018) 30:65–70. doi: 10.1111/den.12914

14.

Zhou PH Schumacher B Yao LQ Xu M-D Nordmann T Cai M-Y et al . Conventional vs. waterjet-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection in early gastric cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. (2014) 46:836–43. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1377580

15.

Esaki M Ihara E Sumida Y . Hybrid and conventional endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric neoplasms: a multi-center randomized controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2023) 21:1810–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.10.030

16.

Watanabe J Watanabe J Kotani K . Early vs. delayed feeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric Cancer: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Medicina (Kaunas). (2020) 56:653. doi: 10.3390/medicina56120653

17.

Jee SR Park MI Lim SK Kim SE Ku KH Hwang JW et al . Clinical impact of second-look endoscopy after endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric neoplasm: a multicenter prospective randomized-controlled trial. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2016) 28:546–52. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000586

18.

Esaki M Ihara E Fujii H Sumida Y Haraguchi K Takahashi S et al . Comparison of the procedure time differences between hybrid endoscopic submucosal dissection and conventional endoscopic submucosal dissection in patients with early gastric neoplasms: a study protocol for a multi-center randomized controlled trial (hybrid-G trial). Trials. (2022) 23:166. doi: 10.1186/s13063-022-06099-x

19.

Hasuike N Ono H Boku N Mizusawa J Takizawa K Fukuda H et al . A non-randomized confirmatory trial of an expanded indication for endoscopic submucosal dissection for intestinal-type gastric cancer (cT1a): the Japan clinical oncology group study (JCOG0607). Gastric Cancer. (2018) 21:114–23. doi: 10.1007/s10120-017-0704-y

20.

Hong TC Liou JM Yeh CC . Endoscopic submucosal dissection comparing with surgical resection in patients with early gastric cancer - a single center experience in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. (2020) 119:1750–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2020.08.027

21.

Ishihara R Arima M Iizuka T Oyama T Katada C Kato M et al . Endoscopic submucosal dissection/endoscopic mucosal resection guidelines for esophageal cancer. Dig Endosc. (2020) 32:452–93. doi: 10.1111/den.13654

22.

Tao M Zhou X Hu M Pan J . Endoscopic submucosal dissection versus endoscopic mucosal resection for patients with early gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. BMJ Open. (2019) 9:e025803. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025803

23.

Esaki M Haraguchi K Akahoshi K Tomoeda N Aso A Itaba S et al . Endoscopic mucosal resection vs endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial non-ampullary duodenal tumors. World J Gastrointest Oncol. (2020) 12:918–30. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v12.i8.918

24.

Hoteya S Iizuka T Kikuchi D Yahagi N . Clinical advantages of endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric cancers in remnant stomach surpass conventional endoscopic mucosal resection. Dig Endosc. (2010) 22:17–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2009.00912.x

25.

Yang D Othman M Draganov PV . Endoscopic mucosal resection vs. endoscopic submucosal dissection for Barrett’s esophagus and colorectal neoplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2019) 17:1019–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.09.030

Summary

Keywords

early gastric cancer, endoscopic mucosal resection, endoscopic submucosal dissection, meta-analysis, therapeutic efficacy, subgroup analysis

Citation

Zheng X and Xu L (2025) Endoscopic submucosal dissection vs. endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. Front. Med. 12:1702512. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1702512

Received

10 September 2025

Revised

03 November 2025

Accepted

10 November 2025

Published

27 November 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Cristiano Spada, Fondazione Poliambulanza Istituto Ospedaliero, Italy

Reviewed by

Gianluca Esposito, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Saif Ullah, First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Zheng and Xu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Long Xu, xiaoliz2025@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.