Abstract

Bloodstream infections caused by anaerobic bacteria present a serious threat to patients. Rapid and accurate diagnosis is crucial for treatment and patient prognosis. Herein, we report a rare case of Clostridium paraputrificum bacteremia in an 82-year-old woman who developed an infection after undergoing necrotic small bowel resection. The patient was treated with 5-day anti-infective therapy with meropenem and linezolid, successfully controlling the disease. We also constructed a phylogenetic tree with other similar bacteria using gene sequencing and showed the virulence and antimicrobial resistance of C. paraputrificum. Additionally, the clinical features and antibiotic treatment of this case were reviewed and discussed in the existing literature. This case and review illustrate the insidious nature of C. paraputrificum infections, emphasizing the need for greater clinician awareness and improved diagnostic and treatment strategies.

1 Introduction

Bacteria can be classified according to their oxygen requirements into aerobes, anaerobes, and facultative anaerobes (1). Anaerobes are bacteria that thrive better under anaerobic conditions than in aerobic environments (2). Clostridium species are Gram-positive anaerobic bacilli, including 210 species and 5 subspecies. Clinically significant Clostridia species include C. tetani, C. perfringens, C. botulinum, and Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) (3). Anaerobic bacteremia is a serious threat to the life and health of patients, with a mortality rate as high as 63% (4). If the mucosal barrier is compromised, it can enter the bloodstream and develop severe and potentially harmful infectious diseases. C. paraputrificum infections have now been reported in only 1% of all cases of Clostridium infections, and their clinical significance has not been fully described (5). Herein, we report an 82-year-old woman who developed C. paraputrificum bacteremia after undergoing a necrotizing small bowel resection for intestinal obstruction with necrosis. Timely antibiotic treatment effectively controlled the infection, gradually stabilizing the patient’s condition. This is likely the first reported case of bloodstream infection caused by C. paraputrificum in China.

2 Case presentation

An 82-year-old woman with a history of appendectomy was urgently admitted due to intermittent abdominal colic. On admission, vital signs were as follows: temperature, 36.5 °C; pulse, 84 beats/min; respiratory rate, 22 breaths/min; and blood pressure, 173/84 mmHg. Blood tests were unremarkable. Examination showed diffuse abdominal pain with pronounced rebound tenderness. CT indicated intra-abdominal hernia, intestinal ischemia, and obstruction in the right middle and lower abdomen, leading to the diagnosis of intestinal obstruction with necrosis. The following day, the patient underwent resection of the necrotic small intestine under general anesthesia.

Five days postoperatively, the patient developed chills that persisted for approximately 2 h, with her body temperature reaching 37.5 °C and peaking in the evening. A blood culture was performed immediately, and a repeat computed tomography scan revealed discontinuity in the anastomotic wall, accompanied by localized peritoneal fluid collection, confirming an anastomotic fistula. Given the persistent symptoms and radiological findings, she underwent a second laparotomy, during which the necrotic segment of the small bowel adjacent to the previous anastomosis was resected, and an ileal single-lumen fistula was created to divert intestinal contents.

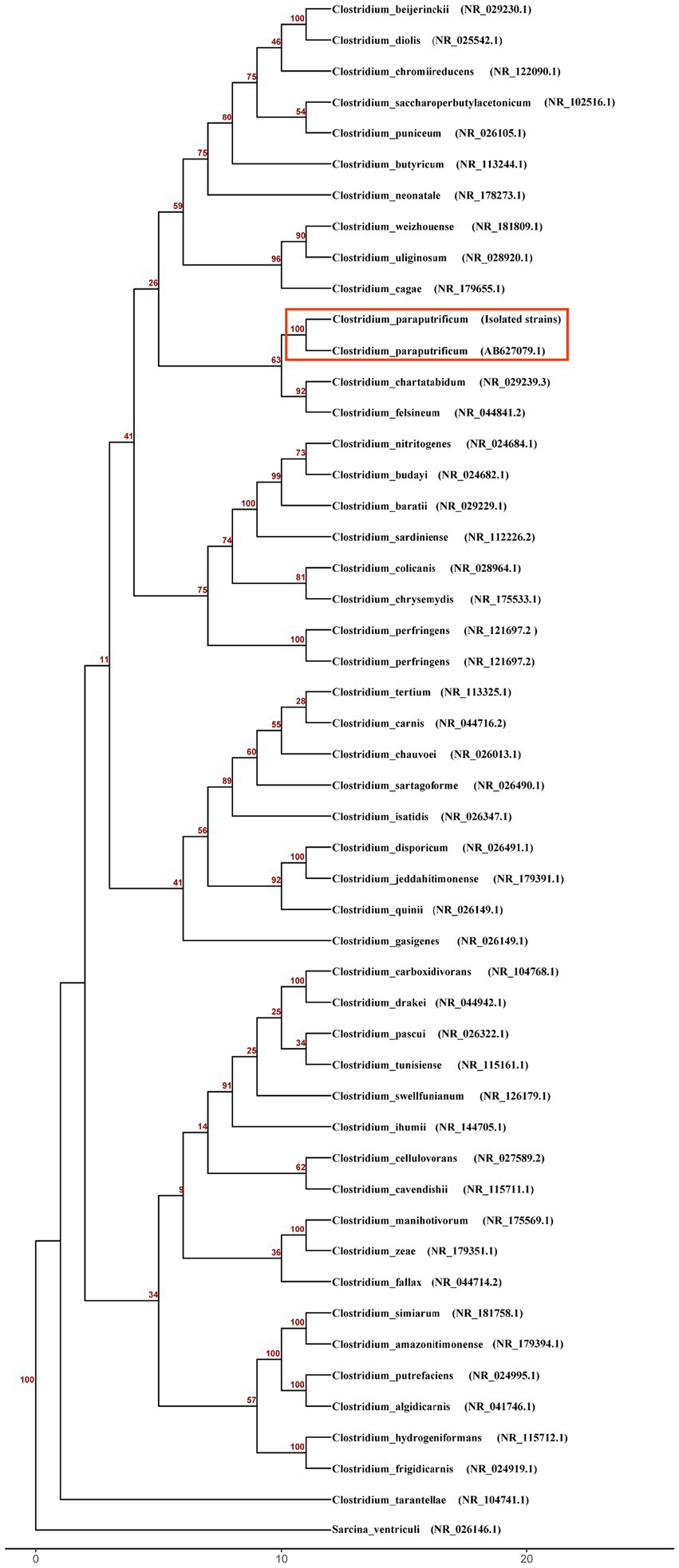

Three days after the second laparotomy, both anaerobic bottles of two sets of blood cultures turned positive. Gram staining showed Gram-positive rods (Figure 1a). Subculture on blood agar at 35 °C yielded no growth aerobically, but anaerobic incubation for 48 h produced grayish-white, irregular colonies with scalloped edges (Figure 1b). Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (Bruker LVD MALDI Biotyper) identified the bacterium as C. paraputrificum (score 2.07) (Figure 1c), with confirmation via whole-genome sequencing (Illumina, Inc., USA, Illumina NovaSeq 6,000) and 16S rRNA analysis (NCBI). Genomic analysis included phylogenetic tree construction using a custom R script, along with analysis of virulence-associated genes using the Virulence Factor Database (VFDB) (6) and identification of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes through the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) and MEGARes database (7, 8). This integrated approach revealed multiple genes associated with both virulence and AMR (Figure 2; Table 1).

Figure 1

(a) Gram stain of a blood culture showing gram-positive rods (×100). Arrows show the bacteria under the microscope. (b) Colonies were seen on a blood agar plate after a 2-day anaerobic conditions culture transferred from the positive blood culture bottles (an anaerobic environment of 35 °C). (c) Matrix-assisted laser desorption and ionization time-of-flight mass spectra from the cultured colony.

Figure 2

Phylogenetic analysis of Clostridium species based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. The neighbor-joining tree was constructed using the Kimura 2-parameter model and rooted with Sarcina ventriculi as the outgroup. Bootstrap values from 100 replicates are shown as decimal numbers at the nodes. Scale bar represents the number of nucleotide substitutions per site.

Table 1

| Sequence | Start | End | Strand | Gene | Database | Accession |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP373A1_19 | 157,965 | 158,773 | – | hasB | VFDB | WP_009880737.1 |

| CP373A1_19 | 162,461 | 163,443 | – | cps4J | VFDB | WP_000077424.1 |

| CP373A1_26 | 352,996 | 353,396 | – | clpP | VFDB | NP_465991 |

| CP373A1_32 | 171,576 | 173,134 | – | clpC | VFDB | NP_463763 |

| CP373A1_28 | 77,979 | 78,481 | – | efrB | CARD/MEGARes | WP_002289400.1 |

| CP373A1_32 | 91,351 | 91,855 | – | efrB | CARD/MEGARes | WP_002289400.1 |

| CP373A1_28 | 79,694 | 80,522 | – | efrA | MEGARes | WP_104671188.1 |

Virulence analysis and antimicrobial resistance analysis of Clostridium paraputrificum.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed based on the identified pathogen to guide targeted therapy. The Anaerobe ID&AST Test Card (Mindray Bio-Medical, China) showed C. paraputrificum was sensitive to ampicillin/sulbactam, piperacillin/tazobactam, cefoxitin, meropenem, metronidazole, chloromycetin, and vancomycin, but resistant to tetracycline and clindamycin. The patient was treated with meropenem (1 g every 8 h) and linezolid (0.6 g every 12 h). After 5 days of antibiotic treatment, the inflammatory markers—C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin (PCT)—returned to normal levels, indicating that the infection was under control (Figure 3). The patient was then transferred to a specialized department for further treatment and was discharged after 10 days when her condition stabilized.

Figure 3

CRP and PCT in the blood throughout the treatment duration.

3 Literature review and discussion

Anaerobic bacterial infections are diverse and common in abdominal, pelvic, complex skin, soft tissue, and bloodstream infections (2). In cases of intestinal necrosis or postintestinal resection, the anaerobic bacteria can translocate through damaged intestinal mucosa, with C. paraputrificum being particularly rare in such contexts. These infections usually involve mixed aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, where aerobes reduce environmental oxygen to facilitate anaerobe growth. Anaerobic cultures require specialized environments, and traditional identification methods are complex and time-consuming, making rare species such as C. paraputrificum easily overlooked (9). Additionally, anaerobes have complex genetic structures and act as potential reservoirs of AMR genes from other species (10).

Clostridium is a gram-positive, anaerobic or microaerophilic, coarse bacillus, causing diseases such as tetanus and gas gangrene (11). Clostridium bacteremia has a mortality rate of 29–35% (12). C. paraputrificum is rare, accounting for only 1% of reported Clostridium infections, and is even less frequently associated with intestinal necrosis or postabdominal surgery bloodstream infections compared to other Clostridium species.

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of C. paraputrificum bloodstream infection in China, highlighting the infection′s complexity and insidious nature. Babenco et al. first reported a C. paraputrificum bacteremia case in 1976 involving an elderly man with myeloproliferative disease and necrotizing colon cancer who died from an infected aneurysm (13). Our review of 12 cases (Table 2) shows that these infections are linked to patient-specific factors, including advanced age (5, 13, 14), HIV infection (15, 16), digestive tract malignancies (13, 17), and gastrointestinal disorders (14, 18). These risk factors increase the likelihood of C. paraputrificum bloodstream infections by weakening immune function, enhancing inflammatory responses, or impairing mucosal barrier function. Impaired immune function leads to defective defense mechanisms, making it easier for pathogens to multiply and harder to clear, thereby significantly increasing the risk of bloodstream infections. Similarly, inflammatory mediators released by inflammatory responses will damage the vascular endothelium throughout the body and facilitate the invasion of pathogens. Age is also a significant risk factor. With aging, intestinal epithelial tight junction proteins may undergo remodeling, leading to increased colonic permeability. Increased intestinal permeability will make it easier for bacteria to pass through the intestinal wall and enter the bloodstream, causing bloodstream infections.

Table 2

| Year | Age | Sex | Source of infection | Underlying disease | Treatment | Outcome | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1976 | 88 | Male | Necrotic colonic carcinoma | Polycythemia vera, adenocarcinoma in the colon | / | Died | (28) |

| 1980 | 10 | Female | / | Sickle cell disease | Penicillin | Cured | (29) |

| 1982 | 65 | Male | Aspiration Pneumonia | Hepatic disease | Penicillin | Cured | (30) |

| 1988 | 32 | Female | Necrotizing enterocolitis | Chronic non-cyclic neutropenia | Ampicillin | Cured | (31) |

| 1996 | 32 | Male | Obstructive duodenal | AIDS, Kaposi’s sarcoma | Metronidazole | Died | (16) |

| 2015 | 65 | Male | Colonic necrosis | AIDS | Vancomycin, Piperacillin/Tazobactam, Metronidazole | Cured | (15) |

| 2017 | 88 | Male | / | Hypertension, pyogenic spondylitis | Ampicillin/Sulbactam | Cured | (5) |

| 2018 | 23 | Female | Pyogenic liver abscesses | Hepatic adenoma | Vancomycin, Levofloxacin, Metronidazole | Cured | (32) |

| 2020 | 78 | Male | Colon neoplasm | Intestinal carcinoma, liver neoplastic | Metronidazole | Cured | (17) |

| 2021 | 74 | Male | Pseudomembranous colitis | Hypertension, iron deficiency, anemia | Vancomycin, Meropenem, Metronidazole |

Died | (33) |

| 2023 | 77 | Male | Colonic pseudo-obstruction | Prostate cancer, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hyperuricemia, | Ampicillin/Sulbactam | Cured | (18) |

| 2023 | 59 | Male | / | AIDS, HCV, HBV, diabetes, and hypertension | Meropenem, Vancomycin | Died | (34) |

Summary of the reported cases of Clostridium paraputrificum bloodstream infection.

3.1 Gene of virulence and AMR

We analyzed the genome sequence of C. paraputrificum and identified several virulence and antibiotic resistance-related genes using the VFDB, CARD, and MEGARes databases. According to the VFDB, C. paraputrificum activates the virulence genes hasB, cps4J, clpP, and clpC. AMR analysis using CARD and MEGARes indicated the presence of efrA and efrB in C. paraputrificum. These genes are associated with bacterial virulence, stress response, and antibiotic resistance. The hasB is essential for hyaluronic acid capsule synthesis and contributes to virulence by facilitating immune evasion (19). The cps4J gene participates in capsular polysaccharide synthesis and immune modulation, thereby enhancing bacterial virulence and immune evasion (20). ClpP and ClpC function together as a proteolytic complex (ClpCP) that maintains protein homeostasis and regulates bacterial stress tolerance and virulence, making them important contributors to pathogenicity (21, 22). EfrAB is an ATP-dependent multidrug efflux pump that exports various antimicrobial agents, particularly fluoroquinolone antibiotics, thereby lowering their intracellular concentration and contributing to multidrug resistance (23, 24). Additionally, studies have shown that antibiotic-resistance genes in human intestinal bacteria can be exchanged within the microbiota and transferred to other bacteria (18). Such bacteria may serve as a potential reservoir for antibiotic resistance genes in other species.

3.2 Drug choice

Selecting antibiotics for anaerobic bacteria presents significant challenges. Research indicates that anaerobic infections are predominantly mixed infections (25). Therefore, it is crucial to remain vigilant with high-risk patients to avoid misdiagnosis. Moreover, increasing evidence shows that anaerobic bacteria are developing resistance to antibiotics, including high-grade options such as imipenem, piperacillin-tazobactam, ampicillin-sulbactam, and metronidazole (26). Suboptimal antibiotic treatment may select resistant bacteria and even induce shifts in resistance determinants. C. paraputrificum is rarely isolated clinically, and research on its antibiotic sensitivity is extremely limited. Therefore, selecting the appropriate antibiotic for patients diagnosed with C. paraputrificum infection is a major challenge. Inappropriate antibiotic use can lead to the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria and increase patient mortality (27). We reviewed all available literature on C. paraputrificum infections (Table 2). Empirical treatment should consider antibiotics such as vancomycin, metronidazole, and imipenem, either alone or in combination. Given the reported resistance to clindamycin, erythromycin, tetracycline, and penicillin, these should not be used as empirical treatments.

4 Conclusion

In conclusion, this case reports a C. paraputrificum bloodstream infection following necrotic small bowel resection, confirmed via anaerobic blood culture and mass spectrometry. Notably, the infection exhibits an insidious clinical profile, characterized by mild fever despite markedly elevated inflammatory markers, underscoring the need for vigilant monitoring of high-risk populations such as postintestinal necrosis patients and timely blood culture testing. Furthermore, genome sequencing clarified the isolate′s phylogenetic position and identified critical virulence and AMR genes, offering insights into its pathogenic mechanisms. Finally, both in vitro susceptibility data and literature evidence support vancomycin, metronidazole, or imipenem as monotherapy or in combination for effectively managing C. paraputrificum bloodstream infections.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee at the People’s Hospital of Deyang City. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

CJ: Methodology, Writing – original draft. KW: Software, Writing – original draft. ZC: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. EJ: Methodology, Writing – original draft. YJ: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZH: Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. WH: Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Sichuan Provincial Science and Technology Department (2025ZNSFSC1561) and the Deyang Science and Technology Bureau (2024SZY001).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Correction note

A correction has been made to this article. Details can be found at: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1761583.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Pedraz L Blanco-Cabra N Torrents E . Gradual adaptation of facultative anaerobic pathogens to microaerobic and anaerobic conditions. FASEB J. (2020) 34:2912–28. doi: 10.1096/fj.201902861R,

2.

Lassmann B Gustafson DR Wood CM Rosenblatt JE . Reemergence of anaerobic bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. (2007) 44:895–900. doi: 10.1086/512197,

3.

Leal J Gregson DB Ross T Church DL Laupland KB . Epidemiology of Clostridium species bacteremia in Calgary, Canada, 2000-2006. J Infect. (2008) 57:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.06.018,

4.

De Keukeleire S Wybo I Naessens A Echahidi F Van der Beken M Vandoorslaer K et al . Anaerobic bacteraemia: a 10-year retrospective epidemiological survey. Anaerobe. (2016) 39:54–9. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2016.02.009,

5.

Fukui M Iwai S Sakamoto R Takahashi H Hayashi T Kenzaka T . Clostridium paraputrificum bacteremia in an older patient with no predisposing medical condition. Intern Med. (2017) 56:3395–7. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.8164-16,

6.

Liu B Zheng D Zhou S Chen L Yang J . VFDB 2022: a general classification scheme for bacterial virulence factors. Nucleic Acids Res. (2022) 50:D912–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1107,

7.

Alcock BP Huynh W Chalil R Smith KW Raphenya AR Wlodarski MA et al . CARD 2023: expanded curation, support for machine learning, and resistome prediction at the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. (2023) 51:D690–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac920,

8.

Bonin N Doster E Worley H Pinnell LJ Bravo JE Ferm P et al . MEGARes and AMR++, v3.0: an updated comprehensive database of antimicrobial resistance determinants and an improved software pipeline for classification using high-throughput sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. (2023) 51:D744–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac1047,

9.

Lagier J-C Edouard S Pagnier I Mediannikov O Drancourt M Raoult D . Current and past strategies for bacterial culture in clinical microbiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. (2015) 28:208–36. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00110-14,

10.

Snydman DR Jacobus NV McDermott LA Golan Y Hecht DW Goldstein EJC et al . Lessons learned from the anaerobe survey: historical perspective and review of the most recent data (2005-2007). Clin Infect Dis an Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. (2010) 50:S26–33. doi: 10.1086/647940

11.

Vijayvargiya P Garrigos ZE Rodino KG Razonable RR Abu Saleh OM . Clostridium paraputrificum septic arthritis and osteomyelitis of shoulder: a case report and review of literature. Anaerobe. (2020) 62:102105. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2019.102105,

12.

Wilson JR Limaye AP . Risk factors for mortality in patients with anaerobic bacteremia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. (2004) 23:310–6. doi: 10.1007/s10096-004-1111-y,

13.

Babenco GO Joffe N Tischler AS Kasdon E . Gas-forming clostridial mycotic aneurysm of the abdominal aorta. A case report. Angiology. (1976) 27:602–9. doi: 10.1177/000331977602701007,

14.

Mostel Z Hernandez A Tatem L . Clostridium paraputrificum bacteremia in a patient with presumptive complicated appendicitis: a case report. IDCases. (2022) 27:e01361. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2021.e01361,

15.

Shinha T Hadi C . Clostridium paraputrificum bacteremia associated with colonic necrosis in a patient with AIDS. Case Rep Infect Dis. (2015) 2015:1–3. doi: 10.1155/2015/312919

16.

Smith KL Wilson M Hightower AW Kelley PW Struewing JP Juranek DD . Clostridium paraputrificum bacteremia in a patient with AIDS and duodenal Kaposi’s sarcoma. Clin Infect Dis. (1996) 23:1995–6.

17.

Intra J Milano A Sarto C Brambilla P . A rare case of Clostridium paraputrificum bacteremia in a 78-year-old Caucasian man diagnosed with an intestinal neoplasm. Anaerobe. (2020) 66:102292. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2020.102292,

18.

Kaneko M Moriyama C Masuda Y Sawachika H Shikata H Matsukage S . Presumptive complicating Clostridium paraputrificum bacteremia as a presenting manifestation in a patient with undiagnosed ulcerative colitis followed by acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. IDCases. (2023) 31:e01652. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2022.e01652,

19.

Li S Xu G Guo Z Liu Y Ouyang Z Li Y . International Immunopharmacology deficiency of hasB accelerated the clearance of Streptococcus equi subsp. Zooepidemicus through gasdermin d-dependent neutrophil extracellular traps. Int Immunopharmacol. (2024) 140:112829. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2024.112829

20.

Abdugheni R Liu C Liu F-L Zhou N Jiang C-Y Liu Y et al . Comparative genomics reveals extensive intra- species genetic divergence of the prevalent gut commensal Ruminococcus gnavus. Microb Genom. (2023) 9:1–12. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.001071

21.

Bhandari V Wong KS Zhou JL Mabanglo MF Batey RA Houry WA . The role of ClpP protease in bacterial pathogenesis and human diseases. ACS Chem Biol. (2018) 13:1413–25. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.8b00124,

22.

Aljghami ME Barghash MM Majaesic E . Cellular functions of the ClpP protease impacting bacterial virulence. Front Mol Biosci. (2022) 9:1054408. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2022.1054408,

23.

Lee E Huda MN Kuroda T Mizushima T Tsuchiya T . EfrAB, an ABC multidrug efflux pump in Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. (2003) 47:3733–8. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.12.3733

24.

Shiadeh SMJ Hashemi A Fallah F Lak P Azimi L Rashidan M . First detection of efrAB, an ABC multidrug efflux pump in Enterococcus faecalis in Tehran, Iran. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. (2019) 66:57–68. doi: 10.1556/030.65.2018.016

25.

Novak A Rubic Z Dogas V Goic-Barisic I Radic M Tonkic M . Antimicrobial susceptibility of clinically isolated anaerobic bacteria in a university hospital Centre Split, Croatia in 2013. Anaerobe. (2015) 31:31–6. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.10.010,

26.

Boyanova L Kolarov R Mitov I . Recent evolution of antibiotic resistance in the anaerobes as compared to previous decades. Anaerobe. (2015) 31:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.05.004,

27.

Kim J Lee Y Park Y Kim M Choi JY Yong D et al . Anaerobic bacteremia: impact of inappropriate therapy on mortality. Infect Chemother. (2016) 48:91–8. doi: 10.3947/ic.2016.48.2.91,

28.

Mycotic GO Joffe N Tischler AS Kasdon E . Gas-forming clostridial mycotic aneurysm of the abdominal aorta. A case report. Angiology. (1976) 27:602–609. doi: 10.1177/000331977602701007

29.

Brook I Gluck RS . Clostridium paraputrificum sepsis in sickle cell anemia. South Med J. (1980) 73:1644–5. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198012000-00033,

30.

Nachamkin I Deblois GEG Dalton HP . Clostridium paraputrificum bacteremia associated with aspiration pneumonia. South Med J. (1982) 75:1023–4. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198208000-00030,

31.

Shandera WX Humphrey RL Berle Stratton L . Necrotizing enterocolitis associated with clostridium paraputrificum septicemia. South Med J. (1988) 81:283–4. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198802000-00037,

32.

Kwon YK Cheema FA Maneckshana BT Rochon C Sheiner PA . Clostridium paraputrificum septicemia and liver abscess. World J Hepatol. (2018) 10:388–95. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v10.i3.388,

33.

Haider A Alavi F Siddiqa A Abbas H Patel H . Fulminant pseudomembranous colitis leading to Clostridium Paraputrificum bacteremia. Cureus. (2021) 13:e13763–7. doi: 10.7759/cureus.13763,

34.

Hosin N Abu-Ali BM Al Rashed AS Al-Warthan SM Diab AE . Clostridium paraputrificum bacteremia in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection: a case report and literature review. Infect Drug Resist. (2023) 16:1449–54. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S400490,

Summary

Keywords

Clostridium paraputrificum , anaerobic bloodstream infections, necroticsmall bowel resection, case report, whole-genome sequencing, literature review

Citation

Ji C, Wang K, Chen Z, Jianfei E, Jiang Y, Huang Z and Huang W (2025) A rare case of Clostridium paraputrificum bloodstream infection in a patient with intestinal necrosis: case report and literature review. Front. Med. 12:1702526. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1702526

Received

10 September 2025

Revised

10 November 2025

Accepted

14 November 2025

Published

03 December 2025

Corrected

06 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Shisan (Bob) Bao, The University of Sydney, Australia

Reviewed by

Keiji Nagano, Health Sciences University of Hokkaido, Japan

Yingmiao Zhang, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Ji, Wang, Chen, Jianfei, Jiang, Huang and Huang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yayun Jiang, dyjiangyayun@163.comZiqian Huang, hzq-fy25@outlook.comWei Huang, 1337539781@qq.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.