Abstract

Background:

Whether the erector spinae plane block (ESPB) truly relieves pain after arthroscopic shoulder surgery (ASS) is still unsettled. We therefore examined whether ESPB sharpens post-operative pain control in these patients.

Methods:

We systematically searched the Cochrane Library, PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing ESPB with any comparator (no block, sham block, or alternative regional block) in patients undergoing ASS. The primary outcome was cumulative opioid consumption within the first 24 h postoperatively. Secondary outcomes included pain scores at rest and during movement, incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), time to first rescue analgesic request, and patient-reported satisfaction with analgesia.

Results:

Six RCTs comprised of 365 patients met inclusion criteria. ESPB did not reduce 24-h opioid consumption versus control (SMD −1.11; 95% CI −2.55 to 0.33; p = 0.13, I2 = 96%). Pain scores were lower with ESPB at 2 h (SMD −0.83; 95% CI −1.30 to −0.37; p = 0.0005, I2 = 35%) and 48 h (SMD −0.64; 95% CI −1.08 to −0.20; p = 0.004, I2 = 95%), but not at 4 h. Furthermore, time to first rescue analgesic was prolonged by ESPB (SMD 4.04; 95% CI 0.77–7.31; p = 0.02, I2 = 99%). However, ESPB did not reduce the rest and movement pain scores at 2 h (SMD −0.87; 95% CI −2.98 to 1.24; p = 0.42; I2 = 97%; SMD −0.98; 95% CI −3.00 to 1.04; p = 0.34; I2 = 97%) and 4 h (SMD −0.43; 95% CI −2.31 to 1.46; p = 0.66; I2 = 97%; SMD −0.89; 95% CI −2.57 to 0.80; p = 0.30; I2 = 96%), respectively. PONV and other adverse events were comparable. Subgroup analysis of single-injection ESPB also showed no opioid-sparing effect (SMD −1.46; 95% CI −3.21 to 0.30; p = 0.10, I2 = 97%). Patient-reported satisfaction revealed no significant difference between ESPB and control group.

Conclusion:

The ESPB fails to reduce 24-h opioid consumption, pain scores at rest and movement at early stage, and the incidence of PONV. Nevertheless, it prolonged the time to first rescue analgesic without elevating the risk of adverse events.

Systematic review registration:

PROSPERO, registration number CRD 42023395027, https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42023395027.

1 Introduction

Modern arthroscopic techniques have converted most shoulder operations into true day-case procedures (1), yet 54% of patients still experience moderate-to-severe pain afterwards, a burden that can derail early mobilization and precipitate unplanned readmission (1, 2). Effective, early analgesia is therefore the linchpin of rapid rehabilitation and shortened length of stay. Regional blockade has become the cornerstone of any multimodal regimen for these patients; the interscalene brachial-plexus block long held pride of place (3), but its well-documented collateral effects have fueled an active search for safer alternatives (3).

Recent work shows that a suprascapular-nerve block (SSNB) can deliver reliable analgesia while leaving the phrenic nerve untouched (4). Yet the lingering side-effects of opioids, Interscalene brachial plexus block (ISB) or even SSNB continue to complicate effective pain relief (3). Because sound rehabilitation and the functional gains that follow hinge on keeping pain in check after arthroscopic shoulder surgery (ASS), a truly efficient analgesic strategy is indispensable for improving outcomes. Introduced by Forero et al. in 2016 for refractory thoracic pain (5), the erector-spinae plane block (ESPB) has since migrated into the peri-operative arena. When injected at the correct spinal level the technique is technically undemanding and can bathe dermatomes from T1 to L3 (3, 6–11). Forero’s group subsequently showed that a high-thoracic ESPB also tames chronic shoulder pain (4), and Taysser et al. reported superior analgesia after ASS compared with intra-articular bupivacaine (12). Bahadir et al. likewise found ESPB outperforming sham injection (13), yet a head-to-head trial against the ISB favored the latter (3). These conflicting signals leave the block’s true worth in ASS uncertain, prompting a fresh wave of randomized trials that now invite quantitative synthesis.

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to synthesize evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to evaluate the analgesic efficacy and safety of ultrasound-guided ESPB in patients undergoing ASS. By addressing these research questions, we seek to provide clinicians with evidence-based recommendations for integrating ESPB into multimodal analgesic regimens, ultimately optimizing postoperative outcomes in this patient population.

2 Methods

The present systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in strict accordance with the PRISMA 2020 statement and the AMSTAR-2 checklist to ensure transparent reporting and methodological rigor (13). An a-priori protocol detailing the review question, eligibility criteria, search strategy, data-extraction procedures, and statistical analyses was prepared and registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (ROSPERO, registration number CRD 42023395027) before any study selection began. Throughout the project we followed this protocol without deviation, used only anonymized summary data already available in the public domain, and collected no new information from living individuals. Consequently, the work was deemed secondary research and was formally exempted from institutional review-board approval and from the requirement for informed consent.

2.1 Search strategy

We systematically interrogated the Cochrane Library, PubMed, Embase and Web of Science from inception to March 2023, with no language or date restrictions initially imposed, coupling MeSH headings with free-text strings and imposing neither language nor date limits. The search was built around the concepts of “arthroscopic shoulder surgery” (shoulder arthroscopy, total shoulder arthroplasty, shoulder surgery) and “erector spinae plane block” (erector spinae muscle), using Boolean operators and truncation to capture every relevant permutation (full line-by-line strategy supplied in Supplementary Digital Content 1). To pre-empt duplication and benchmark our methods against earlier syntheses, we also ran parallel retrieval for existing systematic reviews. Grey literature was hunted manually through conference proceedings, trial registries and thesis repositories, while the reference lists of every eligible article were snowballed to ensnare any overlooked trials.

2.2 Study selection criteria

Two reviewers working independently screened every record against the prespecified criteria, first on title and abstract and then on the full text. Each made the final inclusion or exclusion decision without knowledge of the other’s choice; disagreements were settled by open discussion until consensus was reached. We retained randomized controlled trials that enrolled adults having arthroscopic shoulder surgery includes arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, labral repair, and arthroscopic-assisted total shoulder arthroplasty under general anesthesia, compared any form of ESPB (single-shot, a single intraoperative or preoperative injection of local anesthetic; or continues ESPB, involving an indwelling catheter for continuous local anesthetic infusion) with an alternative regional technique, sham injection, or no block, and quantified post-operative opioid consumption in both study arms. Case reports, observational studies, conference abstracts, letters and trials still recruiting were all excluded.

2.3 Data extraction

Two reviewers working independently extracted data from every included study with a standardized, pre-piloted form. Whenever their entries diverged, a third reviewer was consulted to reach consensus. The form captured bibliographic details (authors, year, country, sample size, sex distribution, ASA class), design elements (randomization method, control and intervention descriptions), pain-related endpoints (cumulative opioid dose in the first 24 h, pain scores at rest and on movement, time to first rescue analgesic), and additional metrics (postoperative complications, patient satisfaction scores). Cumulative opioid consumption at 24 h postoperatively was predefined as the primary outcome; all other variables were classified as secondary.

For the quantitative synthesis, means and standard deviation (SD) were retrieved for continuous or ordinal endpoints such as opioid use or pain intensity, while event counts were collected for binary outcomes like postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV). When authors reported medians, interquartile ranges, or full ranges, we converted these statistics to means and SD with the approximation algorithms proposed by Hozo and colleagues or those outlined in the Cochrane Handbook (14, 15). All opioid doses were translated into oral morphine equivalents (OME) with a validated conversion table (16). Pain at rest or movement was measured with either the visual analogue scale (VAS) or the numeric rating scale (NRS); because the two instruments behave interchangeably (17), each score was linearly transformed to a common 0–10 metric. Assessments were scheduled at fixed intervals: on arrival in the post-anesthesia care unit and at 1, 2, 4, 8, 24, and 48 h after surgery.

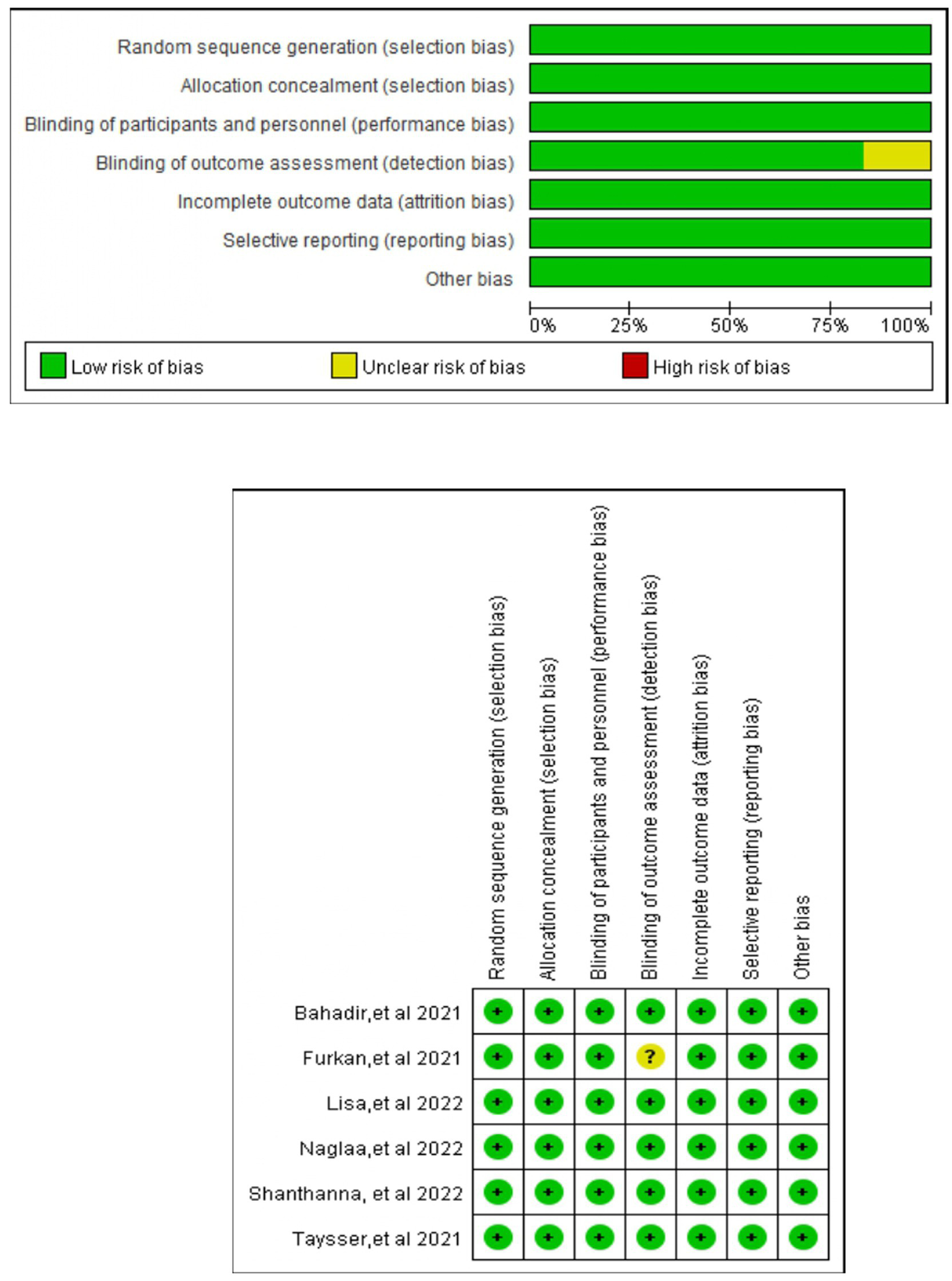

2.4 Assessment of methodological quality

Two reviewers independently appraised the methodological rigor of every trial. For the randomized controlled trials, we applied the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool (18), which scrutinizes seven domains: random-sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, completeness of outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and any additional threats to validity. Each domain was classified as low, high, or unclear risk, informing an overall judgment of the study’s susceptibility to selection, performance, detection, attrition, or reporting bias. The certainty of evidence for each pooled outcome was graded with the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) approach, considering study limitations, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias (19).

2.5 Statistical analysis

Continuous endpoints included 24-h opioid consumption, pain intensity, time-to-first analgesic request, and patient satisfaction scores were pooled as standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence interval (CI) under a random-effects inverse-variance model, chosen because the metric is clinically interpretable across heterogeneous scales (20). Dichotomous events, including PONV, respiratory depression, pruritus, or local-anesthetic toxicity were summarized as risk ratios (RR) with 95% CI via the Mantel–Haenszel method (20). Heterogeneity was quantified with Cochran’s Q and I2; I2 > 50% flagged substantial inconsistency (20). A random-effects framework was retained throughout to accommodate variation in block technique among operators. Subgroup comparisons were restricted to the primary outcome, OME use within 24 h, among trials that delivered a single-injection ESPB. Robustness was explored by leave-one-out sensitivity analysis for the same endpoint. Funnel-plot asymmetry tests (21) evaluated small-study effects in the primary outcomes. Due to the small number of included studies, Egger’s regression and Begg’s rank correlation tests were not performed, as these tests have lower power for less than 10. Two-tailed p < 0.05 defined statistical significance. All computations were performed in Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.3.

3 Results

3.1 Identification of studies

The PRISMA flow-chart (Figure 1) illustrates the step-by-step study selection process. Ninety-nine suitable articles, journals, and abstracts were found in the initial literature review. After thoroughly analyzing the papers and removing any duplicates, six of these studies (3, 11, 12, 22–24) were retained in the current systematic review.

Figure 1

The PRISMA flow diagram of included study of this network-meta-analysis.

Table 1 summarizes the key attributes of the six original research articles that met inclusion criteria (3, 11, 12, 22–24), all of which were registered on the Clinical Trials website. Across the six trials, 365 participants, 166 allocated to ESPB and 199 to control group contributed data to the present analysis. One trial (12) compared ESPB with shame block with 30 mL 0.9% saline at T2, and five trials with other blocks (3, 11, 22–24) (IAI with 20 mL 0.25% bupivacaine, ISB with 30 mL 0.25% bupivacaine, PAI with 30 mL 0.25% bupivacaine, and SSNB with 0.25% 10 mL, respectively). Two studies (22, 24) compared ESPB with continue-ISB (CISB) under different local anesthetics and found that ISB was superior to ESPB (22), however, CESPB could provide a phrenic nerve-sparing alternative analgesia efficacy to CISB (22).

Table 1

| Study | Regime | No. of patients | Age | Gender (M/F) | ASA | Anesthesia | Surgery | Intervention | Control | Sensory test | Multimodal analgesia protocol | Pain scale (rest and movement) | Outcomes | Findings | Registry website |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taysser et al. (11) | Egypt | 30 vs. 30 | 33.3 ± 9.08 vs. 35.7 ± 9.52 | 17/13 vs. 11/19 | I-II | GA | ASS | ESPB at T2 with 20 mL 0.25% bupivacaine + sham IAI with 20 mL saline | IAI with 20 mL 0.25% bupivacaine + sham ESBP with mL saline | NA | NA | VAS | [1, 2, 3, 5] | ESPB superior to IAI | ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04483323) |

| Bahadir et al. (12) | Turkey | 30 vs. 30 | 47.6 ± 13.01 vs. 49 ± 10.26 | 10/20 vs. 16/14 | I-II | GA | ASS | ESPB at T2 with 30 mL 0.25% bupivacaine | Sham block at T2 with 30 mL 0.9% saline | Cold test | ① 400 mg ibuprofen and 100 mg tramadol ② PCA |

VAS | [1, 2, 3] | ESPB superior to sham block | ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04081948) |

| Furkan et al. (22) | Turkey | 30 vs. 30 | 47.03 ± 13.3 vs. 45.07 ± 14.72 | 15/15 vs. 17/13 | I-II | GA | ASS | ESPB at T2 with 30 mL 0.25% bupivacaine | ISB at T2 with 30 mL 0.25% bupivacaine | Cold test | ① 400 mg ibuprofen and 100 mg tramadol ② PCA |

VAS (both) | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5] | ISB provided more effective analgesia than ESPB | ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04083287) |

| Shanthanna et al. (23) | Canada | 31 vs. 31 | 44.8 ± 15.8 vs. 43.8 ± 15.8 | 26/5 vs. 18/13 | I-III | GA | ASS | ESPB at T2 with 30 mL bupivacaine 0.25% with 5 μg.ml-1 adrenaline +PAI | PAI with 30 mL 0.25% bupivacaine with 5 μg.ml-1 adrenaline +ESPB | Cold test | ① 650 mg acetaminophen. | NRS (both) | [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] | ESPB was not superior to PAI | ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03691922). |

| Lisa et al. (24) | USA | 12 vs. 14 | 72.3 ± 6.5 vs. 70.4 ± 12.4 | 7/5 vs. 10/4 | I-III | GA | TSA | Continue ESPB at T1/T2 with 0.5% ropivacaine | ISB with 0.5% ropivacaine | NA | acetaminophen, gabapentin, oxycodone, and hydromorphone | NRS | [1, 3, 4, 5, 6] | CESPB provided alternative analgesia efficacy | ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03807505) |

| Naglaa et al. (3) | Egypt | 33 vs. 32 vs. 32 | 45.9 ± 6.7 vs. 47.5 ± 7.9 | 25/7 vs. 22/10 | I-II | GA | ASS | ESPB at T2 with 30 mL of the LA bupivacaine 0.25% and epinephrine 5 μg/mL | ① SSNB with 0.25% 10 mL bupivacaine with epinephrine 5 μg/mL; ② no block | Cold test | acetaminophen (1 g PO) | NRS (both) | [1, 2, 3, 5] | SSNB not inferior to ESPB | ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04669639) |

Overview of demographic details of ESPB in arthroscopic shoulder surgery.

ASS, Arthroscopic Shoulder Surgery; ESPB, erector spinae plane block; SSNB, Suprascapular nerve block; NRS, Numeric Rating Scale; IAI, Intraarticular injection; VAS, Visual analogue scale; PCA, patient control analgesia; ISB, Interscalene brachial plexus block; PAI, Peri-articular injection; TSA, Total shoulder arthroplasty; ASA, American society of Anesthesiologist; CESPB, Continue erector spinae plane block. Outcomes: [1] Pain scores at different points (NRS, VAS). [2] Postoperative opioids consumption (morphine, fentanyl use). [3] Rescue analgesics. [4] Opioids related complications. [5] Postoperative complications (postoperative nausea, itching, vomiting, and so on). [6] Patient satisfaction with analgesia.

Four studies investigated the postoperative opioid consumption at 24 h (3, 12, 22, 24). Three studies (11, 12, 24) investigated the pain scores (where there is no distinction between resting and movement pain), two studies looked at rest and movement at different points (3, 22) (NRS/VAS scores). Two studies found intraoperative fentanyl consumption (3, 12), two looked at the prevalence of PONV (3, 23), and two looked at nausea (12, 22) and vomiting (12, 22). Respiratory depression was investigated in three studies (3, 12, 23), postoperative itching was investigated in three studies. LAST linked to regional analgesia techniques was discovered in two studies (23, 24), the first use of rescue analgesics was recorded in three studies (3, 11, 23), patients’ satisfaction with analgesia methods demonstrated in two studies (23, 24). Table 2 collates the secondary outcomes and the GRADE certainty ratings. Across the six RCTs (365 participants) the Cochrane RoB-2 assessment showed low risk for randomization and incomplete outcome data in every trial, whereas allocation concealment remained unclear in four studies and blinding of participants/personnel was impossible (high risk) in three; detection bias was rated unclear in four trials, although the objective nature of the primary opioid-consumption outcome mitigates concern. No selective reporting or additional biases were detected. Overall, two studies were classified as low risk, three as “some concerns,” and one as high risk; yet leave-one-out sensitivity analyses confirmed that excluding the high-risk or any unclear-risk trial did not alter the significance or direction of the pooled estimates, indicating that the review’s conclusions are robust to the identified methodological limitations.

Table 2

| Outcomes | Included studies | Participants | Mean difference (95% CI) | I2 (%) | p-value | Quality of evidence (GRADE) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain scores at different points (VAS/NRS) | |||||||

| Pain scores at PACU | 2 | 86 | 0.28 (− 0.94 to 1.50) | 84 | 0.66 | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕⊕ | (11, 24) |

| Pain scores at 1 h postoperatively | 2 | 120 | −2.24 (− 5.48 to 1.00) | 98 | 0.18 | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕⊕ | (11, 12) |

| Pain scores at 2 h postoperatively | 2 | 120 | − 0.83 (− 1.30 to − 0.37) | 35 | 0.0005 | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕⊕ | (11, 12) |

| Pain scores at 4 h postoperatively | 2 | 120 | 1.74 (4.18 to − 7.65) | 99 | 0.56 | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕⊕ | (11, 12) |

| Pain scores at8h postoperatively | 2 | 120 | −2.45 (− 5.34 to 0.44) | 99 | 0.56 | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕⊕ | (11, 12) |

| Pain scores at 24 h postoperatively | 3 | 146 | −1.37 (− 3.30 to 0.57) | 96 | 0.17 | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕⊕ | (11, 12, 24) |

| Pain scores at 48 h postoperatively | 2 | 86 | − 0.64 (− 1.08 to − 0.20) | 95 | 0.03 | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕⊕ | (12, 24) |

| Pain score at rest at 2 h postoperatively | 2 | 190 | −0.87 (− 2.98 to1.24) | 97 | 0.42 | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕⊕ | (3, 22) |

| Pain score at rest at 4 h postoperatively | 2 | 190 | −0.43 (− 2.31 to1.46) | 97 | 0.66 | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕⊕ | (3, 22) |

| Pain score at movement at 2 h postoperatively | 2 | 190 | −0.98 (− 3.00 to1.04) | 97 | 0.34 | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕⊕ | (3, 22) |

| Pain score at movement at 4 h postoperatively | 2 | 190 | −0.89 (− 2.57 to 0.80) | 96 | 0.30 | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕⊕ | (3, 22) |

| Postoperative complications | |||||||

| Nausea | 2 | 120 | −0.89 (− 2.57 to 0.80) | 89 | 0.89 | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕⊕ | (12, 22) |

| Vomiting | 2 | 120 | 1.01(0.14–2.51) | 78 | 0.99 | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕⊕ | (12, 22) |

| Respiratory depression | 3 | 252 | 1.00(0.40–2.51) | – | 1.00 | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕⊕ | (3, 12, 22) |

| Itching | 3 | 183 | 1.14(0.16–8.22) | 65 | 0.90 | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕⊕ | (12, 22, 23) |

| Local anesthetics poisoning | 2 | 88 | 7.0(0.38–130.10) | – | 0.19 | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕⊕ | (23, 24) |

| PONV | 2 | 192 | 0.55(0.23–1.35) | 36 | 0.19 | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕⊕ | (3, 23) |

| The first time of rescue analgesics | 3 | 250 | 4.04(0.77–7.31) | 99 | 0.02 | ⊕ ⊕ ⊕⊕ | (3, 11, 23) |

Summary of the secondary outcomes and quality of evidence using GRADE.

NRS, Numeric Rating Scale; VAS, Visual analogue scale; PACU, Post-anesthesia care unit; PONV, Postoperative nausea and vomiting; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations.

Figure 2 displays the Cochrane risk-of-bias judgments. It is a two-part graphic that color-codes the RoB-2 judgments for the six trials: the left bar chart shows, for each bias domain, the percentage of studies rated green (low risk), yellow (unclear) or red (high risk)—revealing unanimous low risk for randomization and incomplete data, two-thirds unclear for allocation concealment and assessor blinding, and half high risk for participant/personnel blinding—while the right matrix displays the same traffic-light symbols trial-by-trial, allowing readers to pinpoint which individual studies contribute the dominant concerns. Across the six trials, unclear allocation concealment and lack of participant blinding were the dominant methodological concerns. All studies had been prospectively registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (3, 11, 12, 22–24).

Figure 2

Risk of bias graph and summary: review authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies. Green, red, and yellow circles indicate low, high, and unclear risks of bias, respectively (for interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article).

3.2 Opioid consumption in the first 24 h after surgery

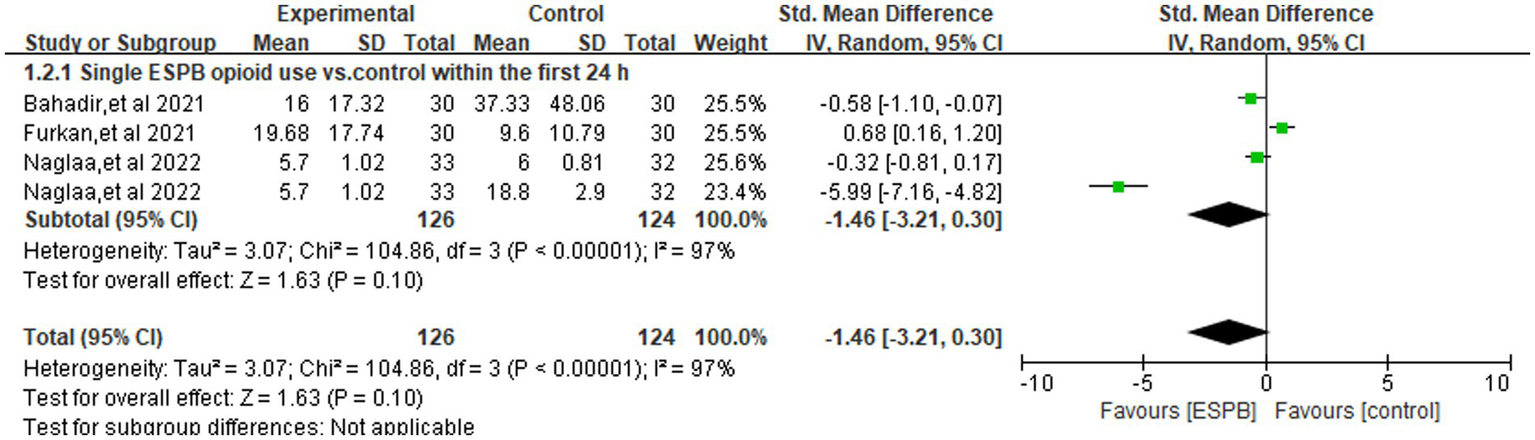

Figure 3 illustrates the pooled comparison of 24-h opioid consumption between ESPB (single-shot or continuous) and control groups across four trials (3, 12, 22, 24), revealed there is no significant difference (SMD -1.11; 95% CI −2.55 to 0.33; =0.13, I2 = 96%). In a subgroup analysis limited to studies using a single-injection ESPB compared with control group (Figure 4), the reduction in opioid consumption was more pronounced but remained non-significant (SMD −1.46; 95% CI −3.21 to 0.30; p = 0.10, I2 = 97%). The funnel plot showed a little asymmetry, as shown in Supplementary Figure 3. Leave-one-out sensitivity analyses confirmed that the pooled estimate for 24-h morphine consumption remained directionally consistent and statistically non-significant after the sequential removal of any single trial, indicating that no individual study exerted undue leverage on the overall result, as shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Figure 3

![Forest plot showing a meta-analysis comparing single or continued ESPB opioid use versus control within the first 24 hours. Five studies are listed with standard mean differences and 95 percent confidence intervals. The pooled estimate is -1.11 [-2.55, 0.33], indicating no significant overall effect. The heterogeneity is high with I-squared at 96 percent.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1702898/xml-images/fmed-12-1702898-g003.webp)

Forest plot comparing single or continued ESPB opioid use (orals morphine milligram equivalents) versus control within the first 24 h following surgery.

Figure 4

Forest plot comparing single ESPB opioid use (orals morphine milligram equivalents) versus control within the first 24 h following surgery.

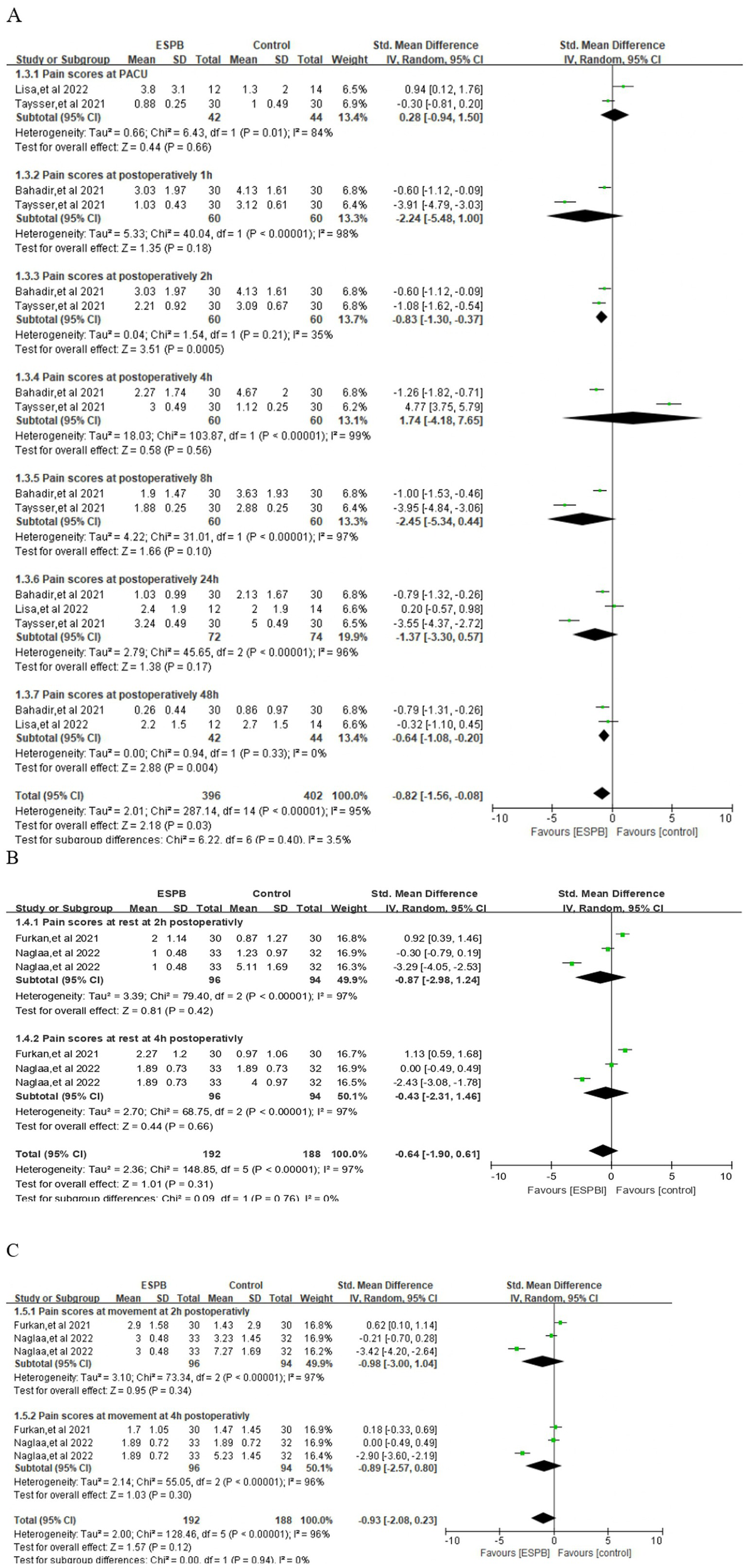

3.3 Pain scores at different points postoperatively

ESPB produced a statistically and clinically meaningful reduction in pain at 2 h (SMD −0.83; 95% CI −1.30 to −0.37; p = 0.0005; I2 = 35%) and 48 h (SMD −0.64; 95% CI −1.08 to −0.20; p = 0.03; I2 = 95%) when compared with control (Figure 5A). In contrast, no reliable separation between groups was detected in the PACU (SMD 0.28; 95% CI −0.94 to 1.50; p = 0.66; I2 = 84%) or at 1 h (SMD −2.24; 95% CI −5.48 to 1.00; p = 0.18; I2 = 98%), 4 h (SMD 1.74; 95% CI −4.18 to 7.65; p = 0.56; I2 = 99%), 8 h (SMD −2.45; 95% CI −5.34 to 0.44; p = 0.56; I2 = 99%), or 24 h (SMD −1.37; 95% CI −3.30 to 0.57; p = 0.17; I2 = 96%) (Figure 5A).

Figure 5

(A) Forest plots of the pain score at different point postoperatively. (B) Pain scores at rest at different point. (C) Pain scores at movement at different point.

3.4 Pain scores at rest or during movement

At rest, ESPB did not achieve a statistically significant reduction in pain severity at 2 h (SMD −0.87; 95% CI −2.98 to 1.24; p = 0.42; I2 = 97%) or at 4 h (SMD −0.43; 95% CI −2.31 to 1.46; p = 0.66; I2 = 97%) post-operatively (Figure 5B). Similarly, pain scores recorded while patients were mobilizing or coughing also revealed no meaningful separation between groups at 2 h (SMD −0.98; 95% CI −3.00 to 1.04; p = 0.34; I2 = 97%) or 4 h (SMD −0.89; 95% CI −2.57 to 0.80; p = 0.30; I2 = 96%) (Figure 5C). However, time to first rescue analgesic was prolonged by ESPB (SMD 4.04; 95% CI 0.77 to 7.31; p = 0.02, I2 = 99%) (Supplementary Figure 2).

3.5 Postoperative complications

Two trials (12, 22) reported the incidence of postoperative nausea, and pooled analysis revealed no significant difference between the ESPB and control groups (RR = 1.15; 95% CI, 0.15–8.59; p = 0.89; I2 = 89%). Vomiting data were available from the same pair of studies (12, 22), and no inter-group disparity was detected (RR = 1.01; 95% CI, 0.14–7.32; p = 0.99; I2 = 99%) (Supplementary Figure 1). PONV was documented in two trials (3, 23), pooled results also revealed no meaningful contrast between ESPB and control (RR 0.55; 95% CI 0.23–1.35; p = 0.19; I2 = 36%). Likewise, three studies (3, 12, 22) recorded respiratory depression, with no significant difference observed (RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.40–2.51; p = 1.00) (Supplementary Figure 1). Post-operative pruritus was extractable from three reports (12, 22, 23); the aggregated risk was virtually identical in ESPB and control arms (RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.16–8.22; p = 0.90; I2 = 65%), with wide confidence limits reflecting the low event rate (Supplementary Figure 1). Similarly, no case of definite LAST was observed in either group across two investigations that explicitly screened for it (23, 24) (RR 7.00, 95% CI 0.38–130.10; p = 0.19).

3.6 Other outcome measures

Patient satisfaction with regional analgesia was reported in two trials (23, 24). However, these studies utilized different metrics to assess satisfaction, one analyzing satisfaction scores and the other evaluating the incidence of satisfied patients and neither demonstrated a significant difference between the ESPB and control groups. Our protocol pre-specified evaluation of small-study effects with funnel-plot asymmetry and, if ≥10 trials were available, Egger’s regression and Begg’s rank test. Only six studies contributed to the primary outcome (24-h opioid consumption), so formal tests lack power and were omitted. The funnel plot (Supplementary Figure 3) shows slight asymmetry (one small trial lying outside the pseudo-confidence limits), but with so few data points this could reflect either true heterogeneity or chance. We therefore interpret the pooled estimate cautiously and emphasize the need for additional large RCTs before confident conclusions about ESPB efficacy in arthroscopic shoulder surgery can be drawn.

4 Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that ESPB lowers the pain scores at 2 and 48 h postoperatively in patients undergoing ASS. Additionally, ESPB also prolonged the first time to rescue analgesic request compared with control group. However, pooled data showed no clinically relevant advantage for ESPB over control in 24-h opioid consumption, or the incidence of PONV, respiratory depression, pruritus or LAST among patients undergoing ASS. Although ESPB may not be superior to ISB (22), it could offer promising postoperative analgesic efficacy compared with no blocks or sham blocks (11, 12). Moreover, CESPB provided alternative and phrenic nerve-sparing analgesic efficacy to ISB (24). ESPB outperformed IAI and PAI and had comparable analgesic efficacy to SNNB (3, 11, 23).

Although opioid sparing and early pain control were the anticipated benefits of ESPB, the demonstrable gains were modest reductions in pain scores at 2 and 48 h and time-to-first rescue analgesia; cumulative morphine use, and all other analgesic metrics remained statistically unchanged. ESPB did not show the merits of increased opioid consumption or the first evidence of analgesic efficacy in patients undergoing ASS. One recent meta-analysis of ESPB in liver surgery involving six studies also revealed that, compared with controls, ESPB did not reduce opioid consumption or lower the pain scores postoperatively (8). This may be a disclosure, though ESPB could offer analgesic efficacy compared with no block or sham block but not be superior to other conventional regional analgesia methods. However, these two meta-analyses only included small sample sizes and insufficient studies with high heterogeneity. Interestingly, ESPB has been employed across a wide spectrum of surgical procedures, reflecting its versatility in selecting the appropriate spinal segment for blockade (5, 7).

A recent investigation demonstrated that, in patients undergoing breast or thoracic procedures, ESPB not only outperformed no-block care but also achieved analgesia comparable to thoracic paravertebral block (TPVB) (5). Moreover, a meta-analysis of 12 trials evaluating ESPB in lumbar surgery found that the block significantly cut 24-h opioid consumption and produced lower pain scores at multiple time-points up to 48 h post-operatively (9). ESPB also increased the patient satisfaction score, decreased the PONV, and minimized the length of hospital stay (9). The inconsistent analgesic profile of ESPB across surgical specialties probably reflects three interacting factors. First, the magnitude of tissue trauma and hence the nociceptive load varies markedly among operations; minimally invasive breast surgery generates a different pain signature from open spinal instrumentation. Second, published RCTs are uniformly underpowered and employ heterogeneous local-anesthetic regimens (ropivacaine 0.2–0.5%, bupivacaine 0.25–0.375%, volumes 15–30 mL), making dose- response inferences impossible. Third, cadaveric and imaging studies (25–27) show that injectate spread and consequent dermatomal anesthesia depend on surgical site: cephalad diffusion is limited after lumbar injection, whereas thoracic deposits reliably reach the paravertebral space and ventral rami, explaining why benefits cluster around thoracic and breast procedures but dissipate in shoulder or hip surgery. Though the majority of studies revealed ESPB, compared with no block or sham block, could offer promising analgesic efficacy by reducing pain scores and opioid consumption, the pain-related results should emphasize the minimally clinically important difference (MCID) (28).

In terms of postoperative complications, despite the theoretical appeal of reducing opioid-related side effects, ESPB failed to translate any putative analgesic gain into higher patient satisfaction or a lower incidence of PONV. This finding is clinically relevant because PONV remains the most distressing opioid-associated complication and a proven driver of prolonged length of stay (29). Indeed, when patients are asked to rank post-operative outcomes, they most wish to avoid, freedom from nausea consistently outranks even pain relief (30). The current evidence therefore indicates that, in the context of ASS, ESPB does not deliver the patient-centered benefit package, such as less PONV, greater satisfaction, which might have been expected from an effective regional technique. One of the included studies showed that a single injection of ESPB was inferior to ISB (22). In contrast to ISB, CESPB may provide an alternative form of postoperative analgesia efficacy (24). ESPB catheterization could extend analgesia and be more effective than a single injection. Furthermore, no serious adverse events, included LAST, pneumothorax, or permanent neurological injury were documented in either the ESPB or control arms. The theoretical safety advantage of ESPB stems from the target plane’s distance from the pleura, major vessels, and neuraxis (31), making catastrophic needle misplacement less likely than with paravertebral or interscalene techniques. Nevertheless, isolated case reports (7) have recorded ropivacaine-induced seizures after high-volume ESPB, and transient ipsilateral motor weakness has been described in several small series (32, 33).

4.1 Limitations of current study

The current study is subject to several limitations. First, ESPB is still in the evolutionary stage; investigators have explored different vertebral levels, volumes, concentrations and timings. This legitimate scientific exploration inevitably increases between-study variance and attenuates the strength of any pooled estimate. Second, individual sample sizes were relatively small, the largest ESPB arm contained only 97 patients. Third, high heterogeneity may weekend the reliable of current study due to the heterogenous control arms, variable ESPB protocols, and differences in multimodal analgesia. Fourth, one study published in 2024 we did not include in the analysis due to the search timeline, which may weaken the robustness of the current conclusion (34). Last but not least, the pooled sample is insufficient to confirm the inherent safety of the block; larger surveillance studies are required before rare but potentially severe complications can be confidently quantified.

5 Conclusion

This meta-analysis of six RCTs (365 patients) evaluates the analgesic efficacy and safety of ESPB in ASS. ESPB reduces pain scores at 2 and 48 h postoperatively and prolongs time to first rescue analgesic without increasing adverse events (e.g., PONV, respiratory depression). However, it fails to reduce 24-h opioid consumption or early resting/movement pain scores. While ESPB is not superior to ISB, it offers a phrenic nerve-sparing alternative and outperforms intra-articular/peri-articular injections. High heterogeneity and small sample sizes limit conclusions. Standardized ESPB protocols and larger trials are needed to confirm its role in multimodal analgesia for ASS. Certainty of evidence ranged from very low to moderate (GRADE), underscoring the need for larger, methodologically rigorous trials before definitive clinical recommendations can be made.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

YW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. QY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Correction note

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the scientific content of the article.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1702898/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Table S1Sensitivity analysis of postoperative opioid consumption at 24 h (oral morphine equivalent) between ESPB and control group. ESPB, Erector spinae plane block.

Supplementary Figure S1Forest plot comparing postoperative complications between ESPB and control group.

Supplementary Figure S2Forest plot comparing the first time of rescue analgesics between ESPB and control group.

Supplementary Figure S3Funnel plot of the ESPB compared with control groups in the opioid consumption at 24 h postoperatively.

References

1.

Narouze SN Govil H Guirguis M Mekhail NA . Continuous cervical epidural analgesia for rehabilitation after shoulder surgery: a retrospective evaluation. Pain Physician. (2009) 12:189–94. doi: 10.36076/ppj.2009/12/189,

2.

Ritchie ED Tong D Chung F Norris AM Miniaci A Vairavanathan SD . Suprascapular nerve block for postoperative pain relief in arthroscopic shoulder surgery: a new modality?Anesth Analg. (1997) 84:1306–12. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199706000-00024,

3.

Abdelhaleem NF Abdelatiff SE Abdel Naby SM . Comparison of erector spinae plane block at the level of the second thoracic vertebra with suprascapular nerve block for postoperative analgesia in arthroscopic shoulder surgery. Pain Physician. (2022) 25:577–85.

4.

Forero M Rajarathinam M Adhikary SD Chin KJ . Erector spinae plane block for the management of chronic shoulder pain: a case report. Bloc du plan des muscles érecteurs du rachis pour la prise en charge de la douleur chronique à l’épaule: une présentation de cas. Can J Anaesth. (2018) 65:288–93. doi: 10.1007/s12630-017-1010-1

5.

Huang W Wang W Xie W Chen Z Liu Y . Erector spinae plane block for postoperative analgesia in breast and thoracic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth. (2020) 66:109900. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2020.109900,

6.

Krishna SN Chauhan S Bhoi D Kaushal B Hasija S Sangdup T et al . Bilateral erector spinae plane block for acute post-surgical pain in adult cardiac surgical patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. (2019) 33:368–75. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2018.05.050,

7.

Huang X Wang J Zhang J Kang Y Sandeep B Yang J . Ultrasound-guided erector spinae plane block improves analgesia after laparoscopic hepatectomy: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Anaesth. (2022) 129:445–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2022.05.013

8.

Bhushan S Huang X Su X Luo L Xiao Z . Ultrasound-guided erector spinae plane block for postoperative analgesia in patients after liver surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis on randomized comparative studies. Int J Surg. (2022) 103:106689. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2022.106689,

9.

Oh SK Lim BG Won YJ Lee DK Kim SS . Analgesic efficacy of erector spinae plane block in lumbar spine surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth. (2022) 78:110647. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2022.110647,

10.

Lennon MJ Isaac S Currigan D O'Leary S Khan RJK Fick DP . Erector spinae plane block combined with local infiltration analgesia for total hip arthroplasty: a randomized, placebo controlled, clinical trial. J Clin Anesth. (2021) 69:110153. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2020.110153,

11.

Abdelraheem TM Ewais WM Lotfy MA . Erector spinae plane block versus intraarticular injection of local anesthetic for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing shoulder arthroscopy: a randomized controlled study. Egypt J Anaesth. (2021) 37:501–6. doi: 10.1080/11101849.2021.1995280

12.

Ciftci B Ekinci M Gölboyu BE Kapukaya F Atalay YO Kuyucu E et al . High thoracic erector spinae plane block for arthroscopic shoulder surgery: a randomized prospective double-blind study. Pain Med. (2021) 22:776–83. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnaa359,

13.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al . The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. (2021) 88:105906. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

14.

Hozo SP Djulbegovic B Hozo I . Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2005) 5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13,

15.

Luo D Wan X Liu J Tong T . Optimally estimating the sample mean from the sample size, median, mid-range, and/or mid-quartile range. Stat Methods Med Res. (2018) 27:1785–805. doi: 10.1177/0962280216669183,

16.

Nielsen S Degenhardt L Hoban B Gisev N . A synthesis of oral morphine equivalents (OME) for opioid utilisation studies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. (2016) 25:733–7. doi: 10.1002/pds.3945,

17.

Kollltveit J Osaland M Reimers M Berle M . A comparison of pain registration by visual analog scale and numeric rating scale – a cross-sectional study of primary triage registration. medRxiv. (2020) 20225367. doi: 10.1101/2020.11.03.20225367

18.

Higgins JP Altman DG Gøtzsche PC Jüni P Moher D Oxman AD et al . The cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. (2011) 343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928

19.

Guyatt G Oxman AD Akl EA Kunz R Vist G Brozek J et al . GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. (2011) 64:383–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026,

20.

Higgins JP Thompson SG Deeks JJ Altman DG . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. (2003) 327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557,

21.

Suurmond R van Rhee H Hak T . Introduction, comparison, and validation of Meta-essentials: a free and simple tool for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. (2017) 8:537–53. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1260,

22.

Kapukaya F Ekinci M Ciftci B Atalay YO Gölboyu BE Kuyucu E et al . Erector spinae plane block vs interscalene brachial plexus block for postoperative analgesia management in patients who underwent shoulder arthroscopy. BMC Anesthesiol. (2022) 22:142. doi: 10.1186/s12871-022-01687-5,

23.

Shanthanna H Czuczman M Moisiuk P O'Hare T Khan M Forero M et al . Erector spinae plane block vs. peri-articular injection for pain control after arthroscopic shoulder surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Anaesthesia. (2022) 77:301–10. doi: 10.1111/anae.15625

24.

Sun LY Basireddy S Gerber LN Lamano J Costouros J Cheung E et al . Continuous interscalene versus phrenic nerve-sparing high-thoracic erector spinae plane block for total shoulder arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Can J Anaesth. (2022) 69:614–23. doi: 10.1007/s12630-022-02216-1,

25.

Chin KJ El-Boghdadly K . Mechanisms of action of the erector spinae plane (ESP) block: a narrative review. Can J Anaesth. (2021) 68:387–408. doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01875-2,

26.

Saadawi M Layera S Aliste J Bravo D Leurcharusmee P Tran Q . Erector spinae plane block: a narrative review with systematic analysis of the evidence pertaining to clinical indications and alternative truncal blocks. J Clin Anesth. (2021) 68:110063. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2020.110063,

27.

Elkoundi A Mustapha B Koraichi AE . Potential mechanism for bilateral sensory effects after a unilateral erector spinae plane block. Can J Anaesth. (2020) 67:909–10. doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01580-0,

28.

Laigaard J Pedersen C Rønsbo TN Mathiesen O Karlsen APH . Minimal clinically important differences in randomised clinical trials on pain management after total hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth. (2021) 126:1029–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.01.021,

29.

Kovac AL . Postoperative nausea and vomiting in pediatric patients. Paediatr Drugs. (2021) 23:11–37. doi: 10.1007/s40272-020-00424-0,

30.

Macario A Weinger M Carney S Kim A . Which clinical anesthesia outcomes are important to avoid? The perspective of patients. Anesth Analg. (1999) 89:652–8. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199909000-00022,

31.

De Cassai A Bonvicini D Correale C Sandei L Tulgar S Tonetti T . Erector spinae plane block: a systematic qualitative review. Minerva Anestesiol. (2019) 85:308–19. doi: 10.23736/S0375-9393.18.13341-4,

32.

Missair A Flavin K Paula F Benedetti de Marrero E Benitez Lopez J Matadial C . Leaning tower of Pisa? Avoiding a major neurologic complication with the erector spinae plane block. Reg Anesth Pain Med. (2019) 44:713–4. doi: 10.1136/rapm-2018-100360,

33.

Selvi O Tulgar S . Ultrasound guided erector spinae plane block as a cause of unintended motor block. Bloqueo en el plano del erector de la columna ecoguiado como causa de bloqueo motor imprevisto. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. (2018) 65:589–92. doi: 10.1016/j.redar.2018.05.009

34.

Zhu M Zhou R Wang L Ying Q . The analgesic effect of ultrasound-guided cervical erector spinae block in arthroscopic shoulder surgery: a randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Anesthesiol. (2024) 24. Published 2024 Jun 3:196. doi: 10.1186/s12871-024-02586-7,

Summary

Keywords

erector spinae plane block, analgesia efficacy, arthroscopic shoulder surgery, pain management, meta-analysis

Citation

Wang Y, Yang Q, Jie W, Liu Y and Jiang F (2025) Analgesic efficacy of erector spinae plane block for managing pain in arthroscopic shoulder surgery: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 12:1702898. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1702898

Received

26 September 2025

Revised

24 November 2025

Accepted

26 November 2025

Published

12 December 2025

Corrected

16 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Abhijit Nair, Ministry of Health, Oman

Reviewed by

Marco Echeverria-Villalobos, Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, United States

Ujjwalraj Dudhedia, Hiranandani Hospital, India

Tuhin Mistry, Ganga Hospital, India

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Wang, Yang, Jie, Liu and Jiang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fenglin Jiang, jiangfenglin0125@163.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.