Abstract

Chronic hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection is increasingly recognized as a significant cause of post-transplant hepatitis in immunosuppressed patients. Although HEV genotype 3 is the most prevalent in Europe, the clinical significance of subgenotypic diversity remains poorly defined. We report two kidney transplant recipients (KTR) diagnosed with chronic HEV infection during routine follow-up. Both patients presented with abnormal liver function tests in the absence of overt clinical symptoms. A broad-spectrum nested RT-PCR assay targeting the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) gene of the ORF1 region of the HEV genome was performed, followed by sequencing and phylogenetic analysis. Viral sequences detected in stool samples clustered with HEV-3c and HEV-3ra subtypes, the latter being a zoonotic variant associated with rabbits. Immunosuppressive reduction alone was insufficient for viral clearance, and both patients achieved sustained virologic response after six-month ribavirin therapy. These findings are consistent with established features of chronic HEV infection in KTR but also extend current knowledge by documenting the first case of HEV-3ra in this population. The present work underscores the importance of systematic HEV surveillance and routine molecular characterization in transplant medicine, reinforcing the need for timely initiation of antiviral therapy to prevent progression to advanced forms of liver disease.

Introduction

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is an emerging cause of viral hepatitis globally (1, 2). Phylogenetic analysis have identified several genotypes, HEV-1 to HEV-8, of which HEV-1, HEV-2, HEV-3, HEV-4, and HEV-7 are known to infect humans (3). While HEV-1 and HEV-2 have been found only in humans and are associated with waterborne outbreaks in developing countries, HEV-3 and HEV-4 have a broader host range and cause zoonotic infections in humans mainly through the consumption of raw or undercooked pork meat or contact with infected swine (4). While most HEV-3 and HEV-4 infections remain asymptomatic or self-limiting, immunocompromised patients are at risk of chronic liver disease that may progress rapidly to cirrhosis and liver failure (5, 6). HEV-3 represents the leading cause of chronic infection in immunosuppressed patients, in particular solid organ transplant recipients (7, 8). Kidney transplant recipients represent a particularly vulnerable group, in whom chronic HEV infection can compromise both hepatic and graft outcomes (9).

Genotype 3 displays considerable genetic, geographic and host heterogeneity, with subgenotypes 3a-3f prevailing in Europe and North America and 3g-3j mainly reported in Asia (10, 11). Rabbit associated hepatitis E virus (raHEV) was first identified in farmed and wild rabbits in France between 2007 and 2010 (12), and subsequent molecular characterization established it as a distinct subgenotype within genotype 3 (HEV-3ra), widely distributed among rabbit populations across Europe and Asia (13). Recent surveillance studies have confirmed HEV-3ra or closely related clades in regions where rabbit farming and consumption are common (14). Experimental studies in immunocompromised rabbits have shown that both human and rabbit HEV strains can establish chronic infection, supporting potential for zoonotic transmission (15). Although a single report from Germany described chronic HEV infection in an immunosuppressed patient harboring a strain closely related to HEV-3ra (16), definite evidence of human infection has not yet been established.

Diagnosis of chronic hepatitis E in immunocompromised hosts is challenging because serology is often unreliable, requiring molecular confirmation (17). Management generally involves reduction of immunosuppressive therapy, which clears the virus in only a subset of patients, while ribavirin has become the mainstay of treatment in persistent cases (18–20). Although ribavirin is effective in treating chronic HEV infection, it can cause side effects, such as hemolytic anemia, requiring careful monitoring (21).

Herein, we report two long-term kidney transplant recipients who presented with elevated liver enzymes during routine follow-up and were subsequently diagnosed with chronic HEV genotype 3 infection, including the first documented case involving HEV-3ra, alongside a review of the literature documenting cases of chronic HEV infection in kidney transplant recipients

Materials and methods

Samples

Blood and stool samples were collected from both kidney transplant recipients for HEV molecular detection at diagnosis, at treatment initiation, and at 1-, 2-, 3-, and 6-months during therapy, as well as 3 and 6 months after ribavirin discontinuation. In parallel, blood analyses included complete blood count as well as liver and renal function tests.

Sample preparation and RNA extraction for HEV detection

Blood samples were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min for plasma separation and stool samples were pre-treated with InhibitEx buffer from QIAamp Fast DNA stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Nucleic acid was extracted from 400 μl of plasma and stool samples using the QIAmp DSP Virus Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) in the EZ1 Advanced (Qiagen) with a 60 μl elution volume.

Real-time RT-PCR for HEV monitoring

For HEV monitoring extracts were screened individually using a broad-spectrum real-time RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) assay targeting the ORF3 region, using primers and a TaqMan probe as described previously (22). The RT-qPCR assays were performed using the iTaq Universal Probes One-Step Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, United States) with a final reaction volume of 20 μL, carried out on a CFX Connect Real-Time thermocycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, United States). The thermal profile began with reverse transcription at 50 °C for 10 min, followed by reverse transcriptase inactivation and initial cDNA denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min. Amplification was then conducted over 45 cycles, each including denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s and annealing/extension at 55 °C for 15 s. The detection limit of the assay is 500 copies/mL.

Nested RT-PCR for HEV genotyping

Hepatitis E virus genotyping was performed using a broad-spectrum nested RT-PCR assay targeting the RNA-dependent RNA-polymerase (RdRp) gene of the ORF1 region of the HEV genome (nt 331-334) using the outer primer set HEV-cs/HEV-cas (TCGCGCATCACMTTYTTCCARAA/GCCATGTTCCAGACDG TRTTCCA) and inner primer set HEV-csn/HEV-casn (TGTGCTCTGTTTGGCCCNTGGTTYCDG/CCAGGCTCACCR GARTGYTTCTTCC), spanning nt 4285–4616 (numbering according to genotype 3 strain Meng accession number AF082843), developed for detection of novel hepeviruses (23). For the first round, Qiagen One-Step RT-PCR kit (Qiagen®, Hilden, Germany) was used and for the second round, 5 μL of the first-round products were used as templates with GoTaq® (Promega, WI, United States), all according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The WHO PEI 6329/10 subgenotype 3a standard (accession number AB630970, provided by the Paul Ehrlich-Institute, Langen, Germany) was used as a positive control and RNase-free water as negative control. Amplification reactions, with the corresponding positive and negative controls (nuclease – free water), were conducted in Bio-Rad T100TM Thermal Cycler. The conditions for the first round were an initial reverse transcription (RT) step for 15 min at 45 °C followed by 3 min at 95 °C (enzyme activation, denaturation of template DNA), 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 50 °C for 15 s, and 72 °C for 2 s, with a final elongation at 72 °C for 10 min. The second round followed the same conditions, excluding the RT step.

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

Amplicons of the expected size that tested positive were purified using the GRS PCR & Gel Band Purification Kit (GriSP®). Following purification, bidirectional sequencing was performed with the Sanger method and appropriate internal specific primers for the target gene. The sequences were then aligned and compared to those in the NCBI (GenBank) nucleotide database, using the BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor v7.1.9 software package, version 2.1. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using MEGA version X software (24). The maximum-likelihood (ML) approach was used to infer this analysis (24, 25), and General Time Reversible model was used to estimate the maximum likelihood (ML) bootstrap values using 1,000 replicates. The General Time Reversible was determined by MEGA version X as the best replacement (24). Further typing was performed with the HEVnet genotyping tool to identify HEV genotypes/subgenotypes (26).

Results

The first patient was a 50-year-old male, 2 years post-kidney transplantation, who presented with elevated liver enzymes during routine follow-up. HEV infection was confirmed by RNA detection in blood, and chronic hepatitis E was assumed after persistent viremia despite reduction of immunosuppression. Ribavirin therapy was initiated, initially planned for 3 months, but extended to 6 months due to persistence of HEV RNA in stool after 2 months of therapy. Hemolysis during treatment required stepwise dose reductions, yet sustained virological clearance was achieved and maintained after therapy discontinuation.

The second patient was a 51-year-old male, 10 years post-transplantation, also diagnosed with HEV infection and chronic hepatitis E after unexplained elevations of aminotransferases and persistent viral replication after reduction of immunosuppression, respectively. Ribavirin was started at a dose adjusted according to renal function, later increased for tolerance, and was extended to 6 months after HEV RNA remained detectable in stool at month 2. Treatment was well-tolerated, and sustained clearance was confirmed after therapy.

The demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of the two kidney transplant recipients are summarized in Table 1, while Table 2 presents longitudinal laboratory follow-up findings, HEV RNA monitoring, and treatment outcomes.

TABLE 1

| Characteristics | Patient 1 | Patient 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | Male |

| Age (years old) | 50 | 51 |

| Year of transplant | 2021 | 2013 |

| Immunosuppressive regimen | Prednisolone 5 mg/day | Prednisolone 5 mg/day |

| Mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg 12/12 h | Mycophenolate mofetil 750 mg 12/12 h | |

| Tacrolimus 11 mg/day | Tacrolimus 5 mg/day | |

| Clinical presentation | Elevated liver enzymes | Elevated liver enzymes |

| AST/ALT 90/57 U/L | AST/ALT 100/73 U/L | |

| Onset of hepatitis | November 2023 | October 2023 |

| HEV RNA+(blood) | HEV RNA+(blood) | |

| Treatment adjustment | Tacrolimus reduction to 7.5 mg/day | Tacrolimus reduction to 4.5 mg/day |

| Evolution | December 2023 | November 2023 |

| HEV RNA+(blood, stool) | HEV RNA+(blood, stool) | |

| Hepatis A immunity | Yes | Yes |

| Hepatitis B carrier | No (vaccinated) | No (vaccinated) |

| Hepatitis C serology | Negative | Negative |

Demographic and clinical characteristics of hepatitis E virus (HEV)-3 infected kidney transplant patients.

AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase.

TABLE 2

| Characteristics | Patient 1 | Patient 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment start | December 2023 Ribavirin | December 2023 Ribavirin |

| Initial dose | 1,000 mg/day | 200 mg/day (renal adjustment) |

| Dose adjustment | 800 mg/day (hemolysis) | 400 mg/day (tolerance) |

| Further adjustment | 600 mg/day (hemolysis) | – |

| Month 0 | HEV RNA+(blood, stool) | HEV RNA+(blood, stool) |

| Month 1 | HEV RNA–(blood, stool) | HEV RNA–(blood, stool) |

| Month 2 | HEV RNA+(stool only) | HEV RNA+(stool only) |

| Month 3 | HEV RNA–(blood, stool) | HEV RNA–(blood, stool) |

| Month 6 | HEV RNA–(blood, stool) | HEV RNA–(blood, stool) |

| Month 3 post-treatment | HEV RNA–(blood, stool) | HEV RNA–(blood, stool) |

| Month 6 post-treatment | HEV RNA–(blood, stool) | HEV RNA–(blood, stool) |

| Adverse events | Hemolysis (Hb nadir 9.7 g/dL) | None |

| Outcome | Sustained virological clearance | Sustained virological clearance |

Laboratory follow-up, hepatitis E virus (HEV) detection and treatment outcomes.

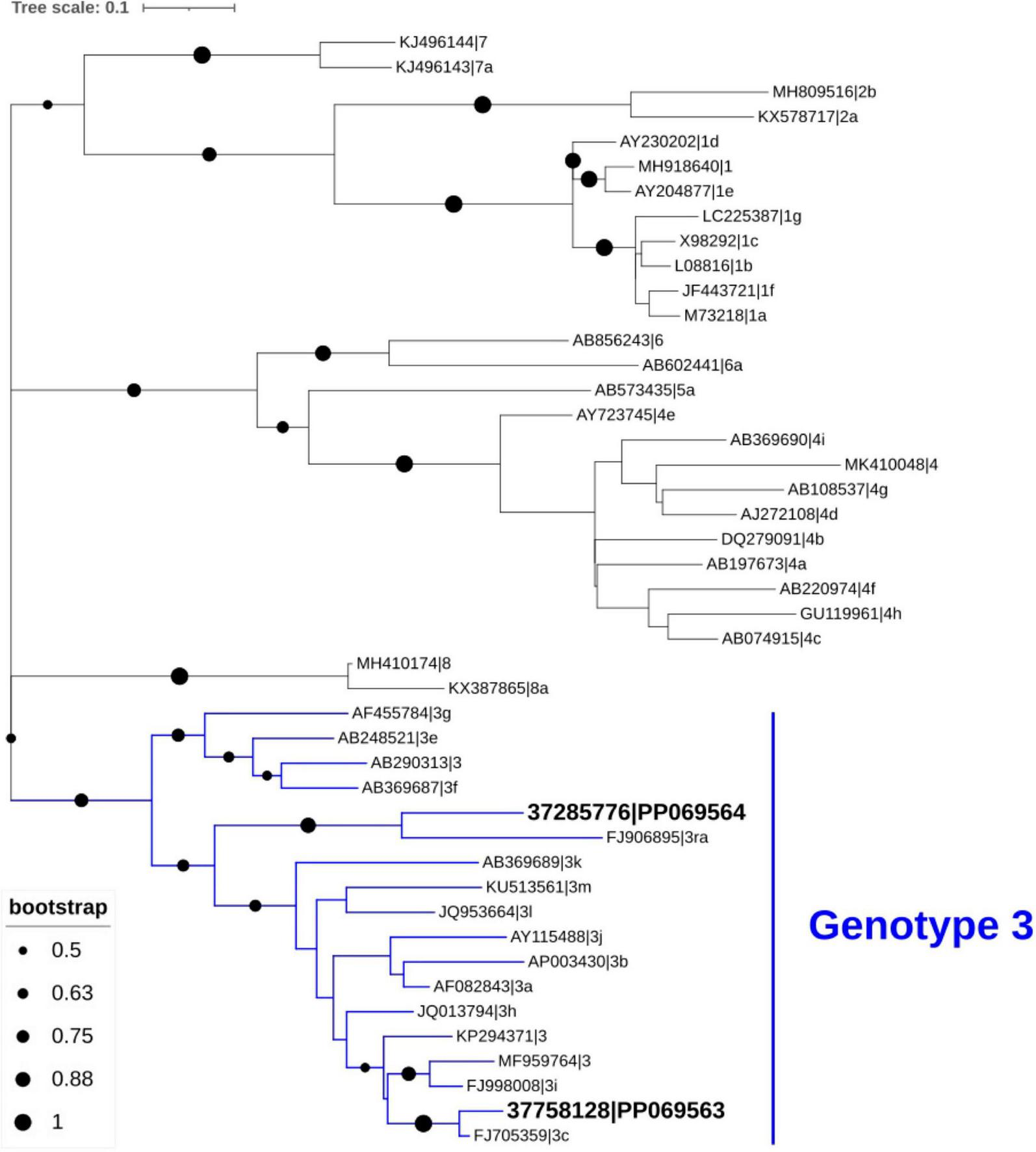

Phylogenetic analysis of HEV sequences obtained from stool samples collected at month 2 from the two kidney transplant recipients revealed clustering within genotype HEV-3, specifically subgenotypes c and ra (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

Phylogenetic analysis of hepatitis E virus (HEV) sequences identified in stool samples from the two patients. Genotypic clustering of these sequences (GenBank database accession number PP069563 and PP069564) confirmed their classification as subtypes 3c and 3ra. The phylogenetic tree was inferred using MEGA X and visualized with the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL), based on 45 HEV nucleotide sequences, including 43 reference strains representing various genotypes obtained from GenBank.

Discussion

The present report describes two renal transplant recipients who developed chronic hepatitis E infection during post-transplant follow-up, occurring 2 and 10 years after transplantation, respectively. Both patients were diagnosed after investigation of abnormal liver function tests, in line with institutional protocol consistent with international clinical practice guidelines (27, 28). Initial reduction of immunosuppressive therapy was insufficient to achieve viral clearance, and ribavirin was required for 6 months. One patient required dose adjustment according to renal function, while the other developed hemolytic anemia after 1 month of therapy, which stabilized after ribavirin dose reduction. These cases illustrate the clinical challenges of balancing antiviral efficacy with hematologic toxicity in the renal transplant population.

To contextualize our findings and critically evaluate the appropriateness of our clinical approach, we conducted a review of the published literature on chronic HEV infection in kidney transplant recipients (Supplementary Table 1) (29–35). This analysis aimed to compare clinical presentations, therapeutic interventions, and outcomes across reported cases, thereby allowing assessment of concordance with existing evidence while also identifying areas where current knowledge remains limited. In this framework, our findings are largely consistent with prior reports. HEV infection in kidney transplant recipients is usually clinically silent, without jaundice, and associated with only modest ALT elevations, typically in the range of 100–300 IU/L. This pattern mirrors findings from prospective studies showing that nearly 60% of solid organ transplant recipients infected with HEV-3 progress to chronic infection (36). Consistent with previous data, both our patients received tacrolimus-based immunosuppression, which has been associated with a higher risk of viral persistence (37).

Natural history data further confirm the risk of rapid fibrosis as progressive liver disease is common, with approximately 10% of chronically HEV infected transplant recipients developing cirrhosis within 3–5 years, a rate faster than that observed in chronic HBV or HCV (36, 37). Early reports described progression to cirrhosis in less than 2 years (38), and more recent series have confirmed accelerated fibrinogenesis in this setting (39). Although such progression was not observed in our two patients during follow-up, these data highlight the potential severity of chronic HEV infection in renal transplant recipients and reinforce the need for systematic HEV surveillance to enable early diagnosis and timely treatment before advanced liver disease develops .

Therapeutic responses in our two cases also align with the published experience. Reduction of immunosuppression alone has been shown to achieve spontaneous clearance in about one-third of patients, particularly when T-cell-targeting agents are minimized (37, 40). However, the majority require ribavirin, which achieves sustained virological response in more than 80% of cases (21). Hematological toxicity is common, particularly hemolytic anemia, often necessitating dose modification (41), as occurred in Patient 1, yet virological clearance was ultimately achieved. Importantly, in our series ribavirin therapy was initiated only after approximately 1 month after diagnosis, once it became evident that immunosuppression reduction alone was insufficient to achieve viral clearance. This delay was also partly due to logistical barriers, including difficulties in the importation of ribavirin, which postponed timely initiation of treatment. Such real-world constraints highlight that treatment delays may contribute to viral persistence and should be considered when interpreting outcomes. Pegylated interferon has occasionally been used as salvage treatment but remains contraindicated in most transplant settings due to the risk of acute rejection (42).

Although chronic HEV infection is conventionally defined by the persistence of HEV RNA in blood or stool for at least 3 months (20), both patients in our series exhibited continued viremia after reduction of immunosuppression, indicating sustained viral replication. Because spontaneous viral clearance after this point is rarely observed in immunosuppressed individuals, ribavirin therapy was initiated without delay. Formal chronicity was subsequently confirmed during longitudinal follow-up according to the standard 3-month definition. This approach aligns with current clinical practice, where early persistence of viremia after immunosuppression reduction is considered a strong predictor of chronic evolution and warrants timely antiviral treatment to prevent progressive liver injury (36, 37).

The present study departs from existing literature in several noteworthy respects, particularly regarding the subgenotype detected and the inferred transmission route. To our knowledge, this is the first documented case of chronic HEV-3 subtype 3ra in a solid organ transplant recipient. Previous publications have described infection with HEV-3a, 3b, and 3c (39, 41), and sporadically with HEV-4 in East Asia (43–45). Other subtypes such as 3e, 3f, and rare recombinant variants like 3hi have been described in human and zoonotic reservoirs but not as a cause of chronic infection in kidney transplant recipients (11, 46, 47). Of particular relevance, subtype 3ra has been primarily reported in rabbits as a zoonotic reservoir, with phylogenetic analysis demonstrating close genetic clustering between rabbit-derived strains and human isolates (48). While this supports the pathogenic potential of HEV-3ra, especially under immunosuppression, documented cases in renal transplant recipients remains unconfirmed. However, given the close genetic relationship between HEV-3ra and human HEV-3, and the zoonotic nature of HEV, it represents a plausible risk — particularly in regions where rabbit meat consumption or exposure is common (49). While donor-derived HEV infections have been reported (50), the long interval since kidney transplantation makes this route unlikely in our patients, supporting autochthonous food-borne exposure as the most plausible source and consistent with predominant HEV-3 epidemiology in Europe.

Beyond rabbit HEV, increasing attention has been directed toward other zoonotic hepatotropic virus, particularly rat HEV (Rocahepevirus ratti). The first human infection was reported in Hong Kong in 2018, where rHEV presented with persistent hepatitis in a liver transplant recipient (51). Subsequent reports from Europe and North America have described severe acute hepatitis in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals (52). Of particular concern, chronic rHEV infection can occur in in solid organ transplant recipients, mimicking the clinical and pathological profile of chronic HEV infection (53). Recognition of rHEV as a hepatotropic human pathogen expands the known diversity of the Hepeviridae family and underscores the need for molecular surveillance capable of distinguishing Orthohepevirus A (HEV genotypes 1–4) from potential emerging hepatotropic virus.

In summary, our findings not only reinforce the established features of chronic HEV infection in solid organ transplant recipients but also expand the current knowledge by documenting the first case of chronic HEV-3ra infection in a renal transplant recipient. The identification of 3ra not only broadens the spectrum of HEV variants known to persisting under immunosuppression but also underscores the zoonotic dimension of HEV transmission. Collectively, these findings emphasize the need for of systematic virological surveillance, judicious adjustment of immunosuppression, timely initiation of ribavirin therapy, and routine viral sequencing to guide clinical practice and epidemiological understanding in transplant medicine.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of University Hospital Center of São João. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

EM: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MA: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SS: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. AP: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SC: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SR: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SS-S: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. MN: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. JM: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. LS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the patients who donated blood and stool for use in this study. Sérgio Santos-Silva thanks Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) for the financial support of his Ph.D. work under the scholarship 2021.09461. BD contract through the Maria de Sousa-2021 program.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1705331/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Nimgaonkar I Ding Q Schwartz RE Ploss A . Hepatitis E virus: advances and challenges.Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2018) 15:96–110. 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.150

2.

Hakim MS Wang W Bramer WM Geng J Huang F de Man RA et al The global burden of hepatitis E outbreaks: a systematic review. Liver Int. (2017) 37:19–31. 10.1111/liv.13237

3.

Brayne AB Dearlove BL Lester JS Kosakovsky Pond SL Frost SDW . Genotype-specific evolution of hepatitis E Virus.J Virol. (2017) 91:e02241-16. 10.1128/JVI.02241-16

4.

Kamar N Izopet J Rostaing L . Hepatitis E virus infection.Curr Opin Gastroenterol. (2013) 29:271–8. 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32835ff238

5.

Murali AR Kotwal V Chawla S . Chronic hepatitis E: A brief review.World J Hepatol. (2015) 7:2194–201. 10.4254/wjh.v7.i19.2194

6.

Thakur V Ratho RK Kumar S Saxena SK Bora I Thakur P . Viral Hepatitis E and Chronicity: a growing public health concern.Front Microbiol. (2020) 11:577339. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.577339

7.

Ahmed R Nasheri N . Animal reservoirs for hepatitis E virus within the Paslahepevirus genus.Vet Microbiol. (2023) 278:109618. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2022.109618

8.

Kupke P Kupke M Borgmann S Kandulski A Hitzenbichler F Menzel J et al Hepatitis E virus infection in immunosuppressed patients and its clinical manifestations. Dig Liver Dis. (2025) 57:378–84. 10.1016/j.dld.2024.06.020

9.

Abravanel F Lhomme S Chapuy-Regaud S Mansuy JM Muscari F Sallusto F et al Hepatitis E virus reinfections in solid-organ-transplant recipients can evolve into chronic infections. J Infect Dis. (2014) 209:1900–6. 10.1093/infdis/jiu032

10.

Lhomme S Top S Bertagnoli S Dubois M Guerin JL Izopet J . Wildlife Reservoir for Hepatitis E Virus, Southwestern France.Emerg Infect Dis. (2015) 21:1224–6. 10.3201/eid2107.141909

11.

Smith DB Izopet J Nicot F Simmonds P Jameel S Meng XJ et al Update: proposed reference sequences for subtypes of hepatitis E virus (species Orthohepevirus A). J Gen Virol. (2020) 101:692–8. 10.1099/jgv.0.001435

12.

Lhomme S Dubois M Abravanel F Top S Bertagnoli S Izopet J et al Risk of zoonotic transmission of HEV from rabbits. J Clin Virol. (2013) 58:357–62. 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.02.006

13.

Santos-Silva S Dudnyk Y Shkromada O Nascimento MSJ Gonçalves HMR Van der Poel WHM et al Rabbit Hepatitis E Virus, Ukraine, 2024. Emerg Infect Dis. (2025) 31:870–3. 10.3201/eid3104.250074

14.

Baylis SA O’Flaherty N Burke L Hogema B Corman VM . Identification of rabbit hepatitis E virus (HEV) and novel HEV clade in Irish blood donors.J Hepatol. (2022) 77:870–2. 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.04.015

15.

Ma H Zheng L Liu Y Zhao C Harrison TJ Ma Y et al Experimental infection of rabbits with rabbit and genotypes 1 and 4 hepatitis E viruses. PLoS One. (2010) 5:e9160. 10.1371/journal.pone.0009160

16.

Klink P Harms D Altmann B Dörffel Y Morgera U Zander S et al Molecular characterisation of a rabbit Hepatitis E Virus strain detected in a chronically HEV-infected individual from Germany. One Health. (2023) 16:100528. 10.1016/j.onehlt.2023.100528

17.

Takakusagi S Kakizaki S Takagi H . The diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment of chronic hepatitis E virus infection-a condition affecting immunocompromised patients.Microorganisms. (2023) 11:1303. 10.3390/microorganisms11051303

18.

Kamar N Del Bello A Abravanel F Pan Q Izopet J . Unmet needs for the treatment of chronic hepatitis E virus infection in immunocompromised patients.Viruses. (2022) 14:2116. 10.3390/v14102116

19.

Goel A Aggarwal R . Hepatitis E: epidemiology, clinical course, prevention, and treatment.Gastroenterol Clin North Am. (2020) 49:315–30. 10.1016/j.gtc.2020.01.011

20.

European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on hepatitis E virus infection. J Hepatol. (2018) 68:1256–71. 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.005

21.

Kamar N Abravanel F Behrendt P Hofmann J Pageaux GP Barbet C et al Ribavirin for hepatitis E virus infection after organ transplantation: a large european retrospective multicenter study. Clin Infect Dis. (2020) 71:1204–11. 10.1093/cid/ciz953

22.

Jothikumar N Cromeans TL Robertson BH Meng XJ Hill VR . A broadly reactive one-step real-time RT-PCR assay for rapid and sensitive detection of hepatitis E virus.J Virol Methods. (2006) 131:65–71. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.07.004

23.

Johne R Plenge-Bönig A Hess M Ulrich RG Reetz J Schielke A . Detection of a novel hepatitis E-like virus in faeces of wild rats using a nested broad-spectrum RT-PCR.J Gen Virol. (2010) 91(Pt 3):750–8. 10.1099/vir.0.016584-0

24.

Kumar S Stecher G Li M Knyaz C Tamura K . MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms.Mol Biol Evol. (2018) 35:1547–9. 10.1093/molbev/msy096

25.

Tamura K . Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions when there are strong transition-transversion and G+C-content biases.Mol Biol Evol. (1992) 9:678–87. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040752

26.

Mulder AC Kroneman A Franz E Vennema H Tulen AD Takkinen J et al HEVnet: a One Health, collaborative, interdisciplinary network and sequence data repository for enhanced hepatitis E virus molecular typing, characterisation and epidemiological investigations. Euro Surveill. (2019) 24:1800407. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.10.1800407

27.

Avery RK . Infectious disease following kidney transplant: Core Curriculum 2010.Am J Kidney Dis. (2010) 55:755–71. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.12.029

28.

Faba OR Boissier R Budde K Figueiredo A Hevia V García EL et al European association of urology guidelines on renal transplantation: update 2024. Eur Urol Focus. (2024) 11:365–73. 10.1016/j.euf.2024.10.010

29.

Meyrier A Yiu V Gao R Mulroy S . Hepatitis in a renal transplant patient-beyond the usual.Clin Kidney J. (2012) 5:170–2. 10.1093/ckj/sfs012

30.

Halleux D Kanaan N Kabamba B Thomas I Hassoun Z . Hepatitis E virus: an underdiagnosed cause of chronic hepatitis in renal transplant recipients.Transpl Infect Dis. (2012) 14:99–102. 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2011.00677.x

31.

Gruz F Cleres M Loredo D Fernández MG Raffa S Yantorno S et al [Hepatitis E: an infrequent virus or an unfrecuently investigated agent?]. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam. (2013) 43:143–5.

32.

Breda F Cochicho J Mesquita JR Bento A Oliveira RP Louro E et al First report of chronic hepatitis E in renal transplant recipients in Portugal. J Infect Dev Ctries. (2014) 8:1639–42. 10.3855/jidc.4637

33.

Bouts AH Schriemer PJ Zaaijer HL . Chronic hepatitis E resolved by reduced immunosuppression in pediatric kidney transplant patients.Pediatrics. (2015) 135:e1075–8. 10.1542/peds.2014-3790

34.

Wang B Harms D Hofmann J Ciardo D Kneubühl A Bock CT . Identification of a novel hepatitis E virus genotype 3 strain isolated from a chronic hepatitis E virus infection in a kidney transplant recipient in Switzerland.Genome Announc. (2017) 5:e00345-17. 10.1128/genomeA.00345-17

35.

van Wezel EM de Bruijne J Damman K Bijmolen M van den Berg AP Verschuuren EAM et al Sofosbuvir add-on to ribavirin treatment for chronic hepatitis E virus infection in solid organ transplant recipients does not result in sustained virological response. Open Forum Infect Dis. (2019) 6:ofz346. 10.1093/ofid/ofz346

36.

Izopet J Tremeaux P Marion O Migueres M Capelli N Chapuy-Regaud S et al Hepatitis E virus infections in Europe. J Clin Virol. (2019) 120:20–6. 10.1016/j.jcv.2019.09.004

37.

Kamar N Garrouste C Haagsma EB Garrigue V Pischke S Chauvet C et al Factors associated with chronic hepatitis in patients with hepatitis E virus infection who have received solid organ transplants. Gastroenterology. (2011) 140:1481–9. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.050

38.

Gérolami R Moal V Colson P . Chronic hepatitis E with cirrhosis in a kidney-transplant recipient.N Engl J Med. (2008) 358:859–60. 10.1056/NEJMc0708687

39.

Moal V Legris T Burtey S Morange S Purgus R Dussol B et al Infection with hepatitis E virus in kidney transplant recipients in southeastern France. J Med Virol. (2013) 85:462–71. 10.1002/jmv.23469

40.

Izopet J Kamar N . [Hepatitis E: from zoonotic transmission to chronic infection in immunosuppressed patients].Med Sci. (2008) 24:1023–5. 10.1051/medsci/200824121023

41.

Panning M Basho K Fahrner A Neumann-Haefelin C . Chronic hepatitis E after kidney transplantation with an antibody response suggestive of reinfection: a case report.BMC Infect Dis. (2019) 19:675. 10.1186/s12879-019-4307-6

42.

Ollivier-Hourmand I Lebedel L Lecouf A Allaire M Nguyen TTN Lier C et al Pegylated interferon may be considered in chronic viral hepatitis E resistant to ribavirin in kidney transplant recipients. BMC Infect Dis. (2020) 20:522. 10.1186/s12879-020-05212-2

43.

Wang Y Chen G Pan Q Zhao J . Chronic hepatitis E in a renal transplant recipient: the first report of genotype 4 hepatitis E virus caused chronic infection in organ recipient.Gastroenterology. (2018) 154:1199–201. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.12.028

44.

Sridhar S Chan JFW Yap DYH Teng JLL Huang C Yip CCY et al Genotype 4 hepatitis E virus is a cause of chronic hepatitis in renal transplant recipients in Hong Kong. J Viral Hepat. (2018) 25:209–13. 10.1111/jvh.12799

45.

Owada Y Oshiro Y Inagaki Y Harada H Fujiyama N Kawagishi N et al A nationwide survey of hepatitis E virus infection and chronic hepatitis in heart and kidney transplant recipients in Japan. Transplantation. (2020) 104:437–44. 10.1097/TP.0000000000002801

46.

Lhomme S Migueres M Abravanel F Marion O Kamar N Izopet J . Hepatitis E Virus: How it escapes host innate immunity.Vaccines. (2020) 8:422. 10.3390/vaccines8030422

47.

Abravanel F Vignon C Mercier A Gaumery JB Biron A Filisetti C et al Large-scale HEV genotype 3 outbreak on New Caledonia Island. Hepatology. (2025) 81:1343–52. 10.1097/HEP.0000000000001081

48.

Abravanel F Lhomme S El Costa H Schvartz B Peron JM Kamar N et al Rabbit Hepatitis E Virus Infections in Humans, France. Emerg Infect Dis. (2017) 23:1191–3. 10.3201/eid2307.170318

49.

He Q Zhang F Shu J Li S Liang Z Du M et al Immunocompromised rabbit model of chronic HEV reveals liver fibrosis and distinct efficacy of different vaccination strategies. Hepatology. (2022) 76:788–802. 10.1002/hep.32455

50.

Solignac J Boschi C Pernin V Fouilloux V Motte A Aherfi S et al The question of screening organ donors for hepatitis e virus: a case report of transmission by kidney transplantation in France and a review of the literature. Virol J. (2024) 21:136. 10.1186/s12985-024-02401-2

51.

Sridhar S Yip CCY Wu S Cai J Zhang AJ Leung KH et al Rat Hepatitis E Virus as Cause of Persistent Hepatitis after Liver Transplant. Emerg Infect Dis. (2018) 24:2241–50. 10.3201/eid2412.180937

52.

Andonov A Robbins M Borlang J Cao J Hatchette T Stueck A et al Rat Hepatitis E virus linked to severe acute hepatitis in an immunocompetent patient. J Infect Dis. (2019) 220:951–5. 10.1093/infdis/jiz025

53.

Casares-Jimenez M Rivero-Juarez A Lopez-Lopez P Montos ML Espinosa N Ulrich RG . Rat hepatitis E virus (Rocahepevirus ratti) in people living with HIV.Emerg Microbes Infect. (2024) 13:2295389. 10.1080/22221751.2023.2295389

Summary

Keywords

HEV, chronic hepatitis E, immunosuppression, kidney transplant recipient, ribavirin

Citation

Matias EF, Azevedo M, Sampaio S, Pinho AT, Conde S, Rebelo S, Santos-Silva S, Nascimento MSJ, Mesquita JR and Santos L (2025) Expanding the spectrum of chronic hepatitis E in kidney transplantation: first report of HEV-3ra infection and review of literature. Front. Med. 12:1705331. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1705331

Received

14 September 2025

Revised

07 November 2025

Accepted

19 November 2025

Published

08 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Jorge Andrade Sierra, University of Guadalajara, Mexico

Reviewed by

Vikram Thakur, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, United States

Gergana Zahmanova, Plovdiv University “Paisii Hilendarski,” Bulgaria

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Matias, Azevedo, Sampaio, Pinho, Conde, Rebelo, Santos-Silva, Nascimento, Mesquita and Santos.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Emanuel F. Matias, ematias@med.up.pt

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.