Abstract

Background:

Re-expansion pulmonary edema (RPE) represents a rare but potentially fatal complication that can occur subsequent to pneumothorax drainage or pleural effusion. Currently, there is a limited understanding of its underlying pathogenesis and associated risk factors. Co-infection with Mycoplasma pneumoniae and influenza A (H1N1) virus, although rare, may exacerbate lung injury and complicate clinical prognoses.

Case presentation:

Herein, we report a case of a 20-year-old male with no prior significant medical history. The patient presented with fever and chest tightness and was subsequently diagnosed with H1N1 influenza, Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia, and right-sided massive spontaneous pneumothorax. Despite the implementation of early closed thoracic drainage with preventive measures against RPE, the patient developed RPE and refractory pneumothorax, ultimately requiring thoracoscopic surgical intervention. Notably, invasive mechanical ventilation was not required, and the patient achieved a full recovery following intensive care management.

Discussion:

This case underscores the intricate pathophysiological interplay between viral and atypical bacterial co-infection. These interactions contribute to the fragility of the lung parenchyma, facilitate the development of pneumothorax, impede the healing process, and potentially elevate the risk of RPE. Notably, even in young patients who are not ventilated and have no pre-existing lung disease, severe pulmonary complications can emerge rapidly in the setting of mixed infections.

Conclusion:

Clinicians should remain a high level of vigilance for refractory pneumothorax and RPE (recurrent pneumothorax with empyema, assuming this is the correct expansion; if not, replace accordingly) in patients presenting with complicated pulmonary infections. Special attention should be directed toward young patients who were previously in good health and have a relatively short disease duration. Meticulous drainage strategies, close surveillance, and early contemplation of surgical intervention are of utmost importance for optimizing patient outcomes. There is a pressing need for further high-quality research to refine prevention guidelines and enhance the management of RPE in intricate clinical scenarios.

1 Introduction

Re-expansion pulmonary edema (RPE) is a rare but potentially fatal complication. It most frequently occurs subsequent to procedures including closed thoracic drainage, thoracentesis, and thoracic mass surgery (1). Although numerous studies have shown that the incidence of RPE following closed thoracic drainage or thoracentesis is less than 1%, respiratory failure due to RPE remains exceptionally rare, with a reported mortality rate reaching up to 20% (2–4). Due to its low incidence and the dearth of high-quality clinical investigations, research regarding the incidence, risk factors, and pathophysiology of RPE is circumscribed, and its exact mechanisms remain elusive.

Since the influenza 2009 pandemic, influenza A (H1N1) has emerged as a paramount global public health concern. It is accountable for hundreds of thousands of annual deaths (5–7). Influenza outbreaks not only impose substantial economic burdens but also pose significant threats to global health security. Secondary infections have been identified as a major determinant of mortality in patients with influenza pneumonia (8, 9). Although Mycoplasma pneumoniae (M. pneumoniae) infections have become increasingly prevalent worldwide in recent years (10–12). However, co - infection involving H1N1 and M. pneumoniae remains relatively infrequent, with a reported co-infection rate of only 2.94% (13). Notwithstanding this low incidence, such co - infections typically manifest with more severe clinical features and are associated with elevated mortality rates.

Notably, pneumothorax, a known complication of pulmonary infections, has not been previously reported in the context of H1N1 co-infected with M. pneumoniae. Herein, we report a rare case of a young adult who was first diagnosed at our hospital with H1N1 and M. pneumoniae pneumonia complicated by a large right-sided pneumothorax. Following closed thoracic drainage, the patient developed PRE. The refractory pneumothorax was eventually resolved through thoracic surgery. In addition to presenting this rare and complex case, we conduct a brief literature review to emphasize the significance of comprehensive evaluation, meticulous clinical decision - making, and proactive strategies for preventing fatal RPE in complex clinical scenarios.

2 Case presentation

A 20-year-old male, with no prior significant medical history, presented to the emergency department (ED) of our hospital at 23:51. He reported having had a fever for 1 day and experiencing chest tightness for 1 h. One day earlier, the patient had onset of fever, reaching a maximum temperature of 39 °C. This was accompanied by a series of symptoms including throat itching, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, cough with sputum production, generalized myalgia, fatigue, dizziness, headache, and intermittent upper abdominal pain. He denied nausea, vomiting, visual or speech abnormalities, chest pain, dyspnea, diarrhea, or urinary symptoms. The patient had self-medicated with ibuprofen and traditional Chinese medicine (Pudilan), yet without any alleviation of symptoms. Approximately 1 h before presentation, the patient developed chest tightness and discomfort, which led to his visit. Since the onset of symptoms, he reported a poor appetite, while his bowel and bladder functions remained normal.

2.1 Physical examination

The patient’s body temperature measured 39.0 °C, heart rate was 79 beats per minute, respiratory rate was 20 breaths per minute, blood pressure was 109/61 mmHg, and oxygen saturation (SpO2) was 94% while breathing room air. During the examination, the patient was alert, oriented, and cooperative. The respiratory effort appeared normal, showing no pharyngeal congestion or tonsillar hypertrophy. Lung auscultation indicated asymmetrical breath sounds, with absent breath sounds over the right lung field and no audible crackles or wheezes. The cardiac examination yielded unremarkable findings, presenting a regular rhythm and no murmurs. The abdomen was soft, non-tender, without rebound tenderness or muscle guarding. There was no evidence of lower limb edema.

2.2 Laboratory and imaging investigations

Chest CT revealed a large right-sided pneumothorax with a small amount of pleural effusion and right lung atelectasis (Figure 1A). No abnormalities were noted in the liver, gallbladder, pancreas, spleen, kidneys, or adrenal glands. Arterial blood gas analysis showed: pH 7.464, PaCO2 32.1 mmHg, PaO2 74 mmHg, base excess (BE) 0, HCO3– 23 mmol/L, and potassium 3.6 mmol/L. Fingerstick blood glucose was 6.7 mmol/L. Laboratory tests showed hemoglobin 130 g/L, platelet count 148 × 109/L, white blood cell count 4.79 × 109/L, neutrophil percentage 65.3%, and monocyte percentage 13.3%. Coagulation profile and biochemistry tests were within normal limits. Mycoplasma pneumoniae IgM antibody was positive. Influenza A antigen test was positive. The nucleic acid test results for 13 respiratory infection-related viruses showed positive for influenza A virus, influenza A H1N1, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae, while adenovirus, bocavirus, rhinovirus, parainfluenza virus, Chlamydia, metapneumovirus, influenza B virus, influenza A H3N2, coronavirus, and respiratory syncytial virus tested negative. The quantitative nucleic acid test for human cytomegalovirus, real-time fluorescence detection of EB virus DNA, Aspergillus galactomannan test, and fungal 1,3-β-D-glucan test all returned negative results. Pre-transfusion infectious disease screening (HBV, HCV, syphilis, HIV) was negative.

FIGURE 1

Serial chest CT images demonstrating disease progression with H1N1 and Mycoplasma pneumoniae co-infection. (A) Initial chest CT showing a massive right-sided pneumothorax with near-complete collapse of the right lung and minimal pleural effusion. (B) Chest CT performed after closed thoracic drainage, showing partial re-expansion of the right lung, persistent pneumothorax (approximately 40% compression), diffuse ground-glass opacities, patchy consolidations consistent with PRE, and subcutaneous emphysema in the right chest wall, axilla, and neck. (C) Follow-up chest CT after several days of continuous negative pressure drainage, demonstrating persistent massive pneumothorax, right lung atelectasis, scattered subcutaneous emphysema, and signs of pneumonia with pulmonary edema.

The initial diagnosis included: (1) right-sided spontaneous pneumothorax; (2) atelectasis; (3) pneumonia; (4) Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection; and (5) Influenza A infection.

2.3 Clinical course and management

The patient was started on supplemental oxygen therapy. For fever management, physical cooling was combined with ibuprofen. Additionally, oral oseltamivir and intravenous levofloxacin were administered. At 02:40 on hospital day 2, bedside closed thoracic drainage was performed under local anesthesia. No intraoperative complications occurred during the procedure. After the operation, the chest tube was clamped for 20 min and then unclamped. A satisfactory water-seal fluctuation was observed.

At 03:30, the patient developed frequent coughing, respiratory distress, chest tightness, and profuse sweating, with a progressive decline in oxygen saturation. Lung auscultation revealed diminished breath sounds over the right lung and wet crackles. A diagnosis of pleural reaction and RPE was considered. The management strategy involved transitioning from nasal cannula to face mask oxygen therapy, reclamping the chest tube, administering an intravenous infusion of 5% dextrose, and administration of intravenous furosemide (20 mg) and dexamethasone (5 mg). Peripheral oxygen saturation fluctuated between 75% and 85%. Chest CT (Figure 1B) showed right-sided pneumothorax and pleural effusion with chest tube in situ, approximately 40% right lung compression, subcutaneous emphysema in the right chest wall, axilla, and neck, along with scattered ground-glass opacities and patchy consolidations in the right lung.

Non-invasive mechanical ventilation was initiated with the ventilation mode of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP). Resulting in an improvement in oxygen saturation to greater than 95%. Following obtained consent from the patient and his parents, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) at 05:10.

In the ICU, the patient continued on non-invasive ventilation and underwent continuous negative-pressure thoracic drainage, its ventilation mode remains CPAP. On hospital day 3, he transitioned back to nasal cannula oxygen while maintaining continuous negative-pressure drainage. Repeat chest CT on hospital day 5 (Figure 1C) revealed a persistent large right-sided pneumothorax with a small amount of effusion, subcutaneous emphysema, right lung atelectasis, and signs of pneumonia and pulmonary edema.

Despite comprehensive supportive care measures, the patient still presented with persistent pneumothorax after being weaned from mechanical ventilation. Based on the joint recommendations from the thoracic surgeon and ICU physician, and due to concerns from both the patient and his family regarding the efficacy of medical management, the decision was made to proceed with surgical intervention. On hospital day 8, he underwent single-port video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) and pleurodesis under general anesthesia.

2.4 Outcome and follow-up

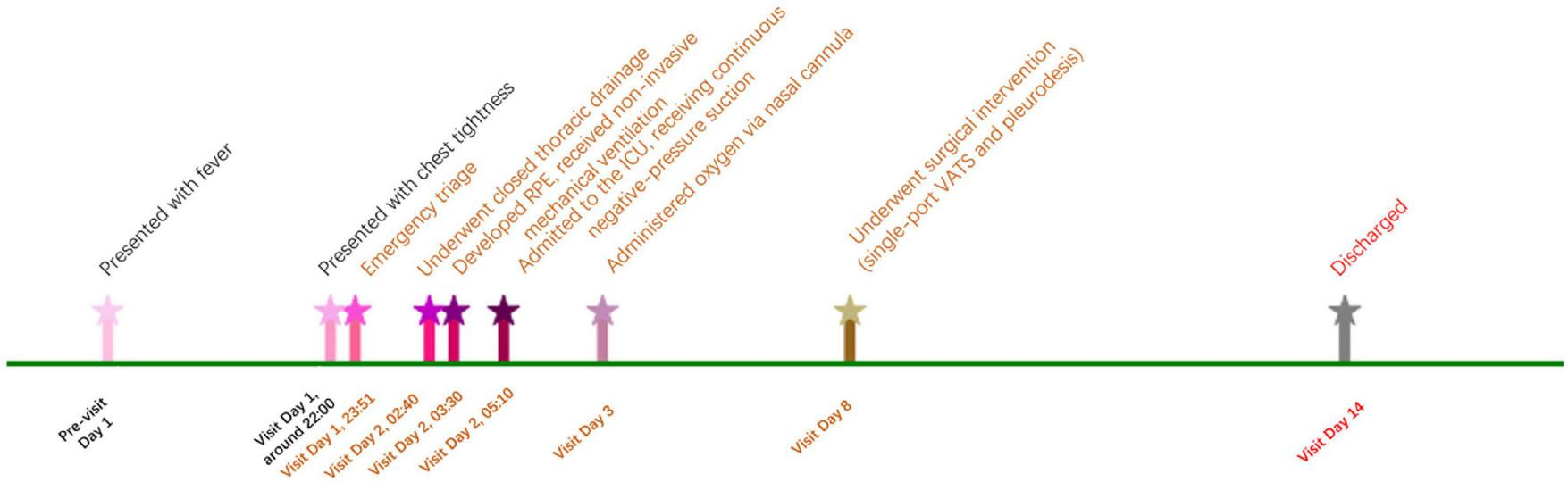

Postoperatively, the patient had an uneventful recovery and was discharged on hospital day 14. The major events and management timeline of the case is presented in Figure 2. One-month follow-up confirmed complete recovery. Recently, we conducted a follow-up telephone call with the patient. The patient reported having a follow-up chest X-ray approximately 6 months after the surgery, the results of which were unremarkable.

FIGURE 2

Major events and management timeline of the case.

3 Discussion

This case describes a rare and complex clinical scenario involving a previously healthy young male. Within 1 day of symptom onset, he developed spontaneous pneumothorax as a consequence of H1N1 influenza and Mycoplasma pneumoniae co-infection. Despite prompt diagnosis and timely closed thoracic drainage with precautionary measures aimed at minimizing the risk of RPE, the patient subsequently developed this serious complication. Notably, the pneumothorax was refractory to continuous negative-pressure drainage and ultimately required surgical intervention. Fortunately, the patient recovered without the need for invasive mechanical ventilation and was discharged without long-term sequelae. The management of this case strictly adhered to the recommendations of the British Thoracic Society Guideline for pleural disease (2023) (14). Specifically, non-invasive diagnostic and therapeutic options were given precedence; continuous negative pressure chest drainage was employed; and when clinical improvement was insufficient, timely thoracoscopic surgery with pleurodesis was carried out, among other congruent interventions.

We believe this case is unique and warrants further contemplation. The simultaneous occurrence of refractory pneumothorax and PRE in a young male with no prior health issues, who had not undergone mechanical ventilation and had a short disease course, is extremely rare in clinical practice. This is particularly true for a young patient experiencing his first episode of pneumothorax, who still required surgical intervention despite aggressive and systematic treatment. Could there be a distinct underlying pathophysiological mechanism at play? Did the co-infection with Mycoplasma pneumoniae and H1N1 influenza significantly influence the progression of his condition?

Co-infection with Mycoplasma pneumoniae and H1N1 influenza virus is uncommon, but it may have contributed to the development of pneumothorax in this patient and hindered its resolution. While both pathogens are individually known to cause pneumonia, limited research has examined their synergistic effects on lung architecture and function (13). Bacterial superinfection is a well-documented factor that exacerbates influenza severity and contributes significantly to mortality (8, 15, 16). It is therefore plausible that co-infection in this case increased lung parenchymal fragility, promoting the development of pneumothorax and complicating recovery.

The concurrent action of H1N1 and Mycoplasma exacerbates damage to epithelial cells and disrupts the tight junctions among cells (e.g., ZO-1), thereby leading to the impairment of the lung barrier function (17, 18). Coinfection suppresses the type I interferon (IFN) response, activates the inflammasome and associated pathways, and concurrently triggers the massive secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β). This forms a “cytokine storm,” causing severe immunopathological damage (18–21). H1N1 and Mycoplasma jointly initiate PANoptosis (panoramic programmed cell death), a complex and intense form of cell death. This process results in the release of a substantial amount of inflammatory substances and exacerbates tissue damage. For instance, it involves the rupture of the cell membrane mediated by the NINJ1 protein and the release of inflammatory factors (19, 20). The influenza virus can commandeer the host’s purine metabolism pathway to fulfill the resource demands for its rapid replication. This alteration in the metabolic environment might be exploited by Mycoplasma to jointly exacerbate inflammation. Examples include the activation of the purine salvage pathway mediated by purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP) and the activation of the APRT-AICAR-AMPK signaling axis (22).

Although pneumothorax is a recognized complication of pneumonia, it generally occurs in patients requiring mechanical ventilation or those with severe underlying disease. Its occurrence in a previously healthy, non-intubated young adult, as observed in this case, is exceptionally rare (23–25). Based on current research reports, we hypothesize that the possible mechanism is that H1N1 influenza and Mycoplasma pneumoniae co-infection can induce thick mucus plugging, surfactant dysfunction, and alveolar rupture through elevated intrapulmonary pressures and reduced lung compliance. This process ultimately triggers the onset of pneumothorax. As the mechanical properties of the lung deteriorate, further predisposing to complications such as refractory pneumothorax (23, 26–29).

Re-expansion pulmonary edema is a rare but serious complication that can follow rapid lung re-expansion after thoracic drainage. Its pathogenesis involves a combination of ischemia-reperfusion injury, oxidative stress, increased capillary permeability, elevated hydrostatic pressure, and impaired lymphatic clearance (30–33). Risk factors identified in previous studies include the extent and duration of lung collapse and a history of smoking (34). In this case, the patient exhibited none of the classic risk factors except for a large pneumothorax, with postoperative imaging suggesting approximately 40% lung compression. Despite gradual and controlled re-expansion via clamped drainage, RPE still occurred, underscoring the unpredictable nature of this complication, even when preventive strategies are employed.

Guidelines currently recommend limiting drainage volumes to under 1500 mL and maintaining pleural pressures above –20 cm H2O during thoracic interventions to mitigate RPE risk (35–38). However, these strategies are mainly applicable to pleural effusion and are difficult to implement in pneumothorax, where air volume cannot be easily quantified. Alternative techniques, such as the use of fine-bore catheters or intermittent decompression via three-way stopcocks, have been proposed to moderate re-expansion and reduce the likelihood of RPE (9, 39).

This case highlights the importance of heightened vigilance for RPE and refractory pneumothorax in patients with complex viral infections. It also underscores the need for individualized drainage strategies and enhanced monitoring protocols in high-risk cases. Future studies should focus on refining diagnostic thresholds, evaluating preventive measures, and establishing evidence-based management guidelines. Moreover, the integration of artificial intelligence and quantitative risk stratification tools may support earlier identification of susceptible patients and enable more tailored therapeutic approaches.

4 Conclusion

This case highlights a rare but severe instance of spontaneous pneumothorax complicated by RPE in a previously healthy young adult with H1N1 and Mycoplasma pneumoniae co-infection. The dual infection likely compromised lung integrity, contributing to refractory pneumothorax and RPE despite early intervention. Clinicians should remain vigilant for RPE even in low-risk, non-ventilated patients with severe or mixed infections, particular attention should be paid to young patients who were previously healthy and have a short disease course. This underscores the need for tailored drainage strategies, better preventive protocols, and further research to guide RPE management in high-risk scenarios.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The work was carried out in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) and approved by the Ethics Committee on Biomedical Research, West China Hospital of Sichuan University. The research was conducted in accordance with local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from all patient(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report.

Author contributions

HW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LP: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. WQ: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. YH: Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declared financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by the Foundation of Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province (Grant No. 2023NSFSC1472).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Cantey E Walter J Corbridge T Barsuk J . Complications of thoracentesis: incidence, risk factors, and strategies for prevention.Curr Opin Pulm Med. (2016) 22:378–85. 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000285

2.

Lee S Hwang J Lim M Son J Kim D . Is severe re-expansion pulmonary edema still a lethal complication of closed thoracostomy or thoracic surgery?Ann Transl Med. (2019) 7:98. 10.21037/atm.2019.01.55

3.

Ault M Rosen B Scher J Feinglass J Barsuk J . Thoracentesis outcomes: a 12-year experience.Thorax. (2015) 70:127–32. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206114

4.

Sakellaridis T Panagiotou I Arsenoglou A Kaselouris K Piyis A . Re-expansion pulmonary edema in a patient with total pneumothorax: a hazardous outcome.Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2012) 60:614–7. 10.1007/s11748-012-0067-6

5.

Dunning J Thwaites R Openshaw P . Seasonal and pandemic influenza: 100 years of progress, still much to learn.Mucosal Immunol. (2020) 13:566–73. 10.1038/s41385-020-0287-5

6.

Rolfes M Foppa I Garg S. Estimated Influenza Illnesses, Medical Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths Averted by Vaccination in the United States. Atlanta: CDC;(2019)

7.

Paget J Spreeuwenberg P Charu V Taylor R Iuliano A Bresee J et al Global mortality associated with seasonal influenza epidemics: new burden estimates and predictors from the GLaMOR Project. J Glob Health. (2019) 9:020421. 10.7189/jogh.09.020421

8.

Arranz-Herrero J Presa J Rius-Rocabert S Utrero-Rico A Arranz-Arija JÁ Lalueza A et al Determinants of poor clinical outcome in patients with influenza pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. (2023) 131:173–9. 10.1016/j.ijid.2023.04.003

9.

Beumer M Koch R van Beuningen D OudeLashof A van de Veerdonk F Kolwijck E et al Influenza virus and factors that are associated with ICU admission, pulmonary co-infections and ICU mortality. J Crit Care. (2018) 50:59–65. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.11.013

10.

Garzoni C Bernasconi E Zehnder C Malossa S Merlani G Bongiovanni M . Unexpected increase of severe Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in adults in Southern Switzerland.Clin Microbiol Infect. (2024) 30:953–4. 10.1016/j.cmi.2024.03.008

11.

Yan C Xue G Zhao H Feng Y Cui J Yuan J . Current status of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in China.World J Pediatr. (2024) 20:1–4. 10.1007/s12519-023-00783-x

12.

Sun Y Li P Jin R Liang Y Yuan J Lu Z et al Characterizing the epidemiology of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections in China in 2022-2024: a nationwide cross-sectional study of over 1.6 million cases. Emerg Microbes Infect. (2025) 14:2482703. 10.1080/22221751.2025.2482703

13.

Zhou Y Wang J Chen W Shen N Tao Y Zhao R et al Impact of viral coinfection and macrolide-resistant mycoplasma infection in children with refractory Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia. BMC Infect Dis. (2020) 20:633. 10.1186/s12879-020-05356-1

14.

Roberts M Rahman N Maskell N Bibby A Blyth K Corcoran J et al British thoracic society guideline for pleural disease. Thorax. (2023) 78:s1–42. 10.1136/thorax-2022-219784

15.

Blyth C Webb S Kok J Dwyer D van Hal S Foo H et al The impact of bacterial and viral co-infection in severe influenza. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. (2013) 7:168–76. 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2012.00360.x

16.

Gill J Sheng Z Ely S Guinee D Beasley M Suh J et al Pulmonary pathologic findings of fatal 2009 pandemic influenza A/H1N1 viral infections. Arch Pathol Lab Med. (2010) 134:235–43. 10.5858/134.2.235

17.

Gu S Xiao W Yu Z Xiao J Sun M Zhang L et al Single-cell RNA-seq reveals the immune response of Co-infection with streptococcus pneumoniae after influenza A virus by a lung-on-chip: the molecular structure and mechanism of tight junction protein ZO-1. Int J Biol Macromol. (2025) 306:141815. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.141815

18.

Deol P Miura T . Respiratory viral coinfections: interactions, mechanisms and clinical implications.Nat Rev Microbiol. (2025) 23:757–70. 10.1038/s41579-025-01225-3

19.

Xu Y Zheng Y Liu Y Wei C Ren J Zuo W et al Ninjurin-1 mediates cell lysis and detrimental inflammation of PANoptosis during influenza A virus infection. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2025) 10:307. 10.1038/s41392-025-02391-9

20.

Zheng Y He D Zuo W Wang W Wu K Wu H et al Influenza A virus dissemination and infection leads to tissue resident cell injury and dysfunction in viral sepsis. EBioMedicine. (2025) 116:105738. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2025.105738

21.

Liu J Lai C Hsueh P . Resurgence of human metapneumovirus in the post-COVID-19 era: pathogenesis, epidemiological shifts, clinical impact, and future challenges.Lancet Infect Dis. (2025) 25:e705–21. 10.1016/S1473-3099(25)00240-3

22.

Yue Y Li Q Chen C Yang J Song W Zhou C et al Purine nucleoside phosphorylase dominates Influenza A virus replication and host hyperinflammation through purine salvage. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2025) 10:191. 10.1038/s41392-025-02272-1

23.

Chandna S Raj K Agrawal A Nanda S Jyotheeswara Pillai K Bhagat U et al Prevalence and patient risk factors for pneumothorax in COVID-19 and in influenza pneumonia: a nationwide comparative analysis. J Thorac Dis. (2024) 16:3593–605. 10.21037/jtd-23-1454

24.

Chandna S Colombo J Agrawal A Raj K Bajaj D Bhasin S et al Pneumothorax in intubated patients with COVID-19: a case series. Cureus. (2022) 14:e31270. 10.7759/cureus.31270

25.

Zahornacký O Porubčin Š Rovňáková A Jarčuška P . Delayed spontaneous pneumothorax in a previously healthy nonventilated COVID-19 patient.Prague Med Rep. (2022) 123:279–86. 10.14712/23362936.2022.26

26.

Li H Cheng J Li N Li Y Zhang H . Critical influenza (H1N1) pneumonia: imaging manifestations and histopathological findings.Chin Med J. (2012) 125:2109–14. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.2012.12.006

27.

Liu J Zheng X Tong Q Li W Wang B Sutter K et al Overlapping and discrete aspects of the pathology and pathogenesis of the emerging human pathogenic coronaviruses SARS-CoV. MERS-CoV, and 2019-nCoV. J Med Virol. (2020) 92:491–4. 10.1002/jmv.25709

28.

Swierzy M Helmig M Ismail M Rückert J Walles T Neudecker J . [Pneumothorax].Zentralbl Chir. (2014) 139:S69–86. 10.1055/s-0034-1383029

29.

Xu Z Shi L Wang Y Zhang J Huang L Zhang C et al Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. (2020) 8:420–2. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X

30.

Kepka S Lemaitre L Marx T Bilbault P Desmettre TA . common gesture with a rare but potentially severe complication: re-expansion pulmonary edema following chest tube drainage.Respir Med Case Rep. (2019) 27:100838. 10.1016/j.rmcr.2019.100838

31.

Cusumano G La Via L Terminella A Sorbello M . Re-expansion pulmonary edema as a life-threatening complication in massive, long-standing pneumothorax: a case series and literature review.J Clin Med. (2024) 13:2667. 10.3390/jcm13092667

32.

Gumus S Yucel O Gamsizkan M Eken A Deniz O Tozkoparan E et al The role of oxidative stress and effect of alpha-lipoic acid in reexpansion pulmonary edema - an experimental study. Arch Med Sci. (2010) 6:848–53. 10.5114/aoms.2010.19290

33.

Sue R Matthay M Ware L . Hydrostatic mechanisms may contribute to the pathogenesis of human re-expansion pulmonary edema.Intensive Care Med. (2004) 30:1921–6. 10.1007/s00134-004-2379-1

34.

Willim H Munthe E Vanto Y Sani A . Risk factors for re-expansion pulmonary edema following chest tube drainage in patients with spontaneous pneumothorax: a systematic review and meta-analysis.J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. (2024) 16:1–7. 10.34172/jcvtr.32871

35.

Havelock T Teoh R Laws D Gleeson F . Pleural procedures and thoracic ultrasound: british thoracic society pleural disease guideline 2010.Thorax. (2010) 65:ii61–76. 10.1136/thx.2010.137026

36.

Feller-Kopman D Berkowitz D Boiselle P Ernst A . Large-volume thoracentesis and the risk of reexpansion pulmonary edema.Ann Thorac Surg. (2007) 84:1656–61. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.06.038

37.

Lin Y Yu Y . Reexpansion pulmonary edema after large-volume thoracentesis.Ann Thorac Surg. (2011) 92:1550–1. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.06.042

38.

Feller-Kopman D Walkey A Berkowitz D Ernst A . The relationship of pleural pressure to symptom development during therapeutic thoracentesis.Chest. (2006) 129:1556–60. 10.1378/chest.129.6.1556

39.

Chen C Chen W Ho C . Management and prevention of re-expansion pulmonary edema after tube thoracostomy for prolonged massive pneumothorax.Chest. (2010) 138:224A. 10.1378/chest.10314

Summary

Keywords

re-expansion pulmonary edema, pneumothorax, influenza A (H1N1), Mycoplasma pneumoniae , exacerbate lung injury

Citation

Wang H, Peng L, Qian W and He Y (2026) Case Report: Re-expansion pulmonary edema following a pneumothorax drainage in a patient with H1N1 and Mycoplasma pneumoniae co-infection. Front. Med. 12:1707288. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1707288

Received

17 September 2025

Revised

16 November 2025

Accepted

27 November 2025

Published

05 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Dorin Dragoş, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Romania

Reviewed by

Dorin Dragoş, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Romania

Ondrej Zahornacky, University of Pavol Jozef Šafárik, Slovakia

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Wang, Peng, Qian and He.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yarong He, heyarong@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.