- 1Key Laboratory of Anesthesia and Analgesia Application Technology, Department of Anesthesiology and Clinical Research Center for Anesthesia and Perioperative Medicine, Huzhou Central Hospital, The Fifth School of Clinical Medicine of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Huzhou, Zhejiang, China

- 2Huzhou Central Hospital, Affiliated Central Hospital Huzhou University, Huzhou, Zhejiang, China

- 3Affiliated Huzhou Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Huzhou, Zhejiang, China

- 4Department of Education and Training, Huzhou Central Hospital, The Fifth School of Clinical Medicine of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Huzhou, Zhejiang, China

- 5Huzhou Key Laboratory of Basic Research and Clinical Translation for Neuromodulation, Huzhou Central Hospital, The Fifth School of Clinical Medicine of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Huzhou, Zhejiang, China

Postoperative gastrointestinal dysfunction (POGD) is a prevalent and clinically significant complication following surgical procedures. It adversely impacts patient comfort, prolongs postoperative hospitalization duration, and increases the risk of perioperative complications and unplanned readmissions, thereby contributing to higher healthcare costs. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) has emerged as a promising neuromodulatory intervention. As a non-invasive technique, it offers several advantages, including ease of administration, a favorable safety profile, and high patient acceptability. This narrative review outlines the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying POGD, the anatomical basis of the vagus nerve, the technical parameters of taVNS, and its therapeutic mechanisms in managing postoperative gastrointestinal disturbances. The objective is to support the development of a comprehensive treatment approach for patients with POGD, promoting accelerated recovery.

Introduction

Postoperative gastrointestinal dysfunction (POGD), commonly known as postoperative ileus (POI), is a common complication following surgical procedures. The incidence of POGD after abdominal surgery ranges from 10% to 30% (1). POGD is characterized by symptoms including nausea, vomiting, abdominal tenderness and distension, absence of normal bowel sounds, and delayed passage of flatus or stool (2). This condition adversely affects patient comfort, prolongs hospitalization, and increases the risk of perioperative complications and readmission, thereby contributing to elevated healthcare costs (3, 4). In recent years, various strategies have been developed to enhance postoperative gastrointestinal recovery, such as administration of alvimopan, adoption of minimally invasive surgical techniques, application of electroacupuncture stimulation (5), consumption of coffee-based beverages (6), intraoperative use of dexmedetomidine (7), chewing gum therapy, intravenous lidocaine infusion (8), and early initiation of enteral nutrition. Despite these advances, there remains a significant need for further improvement in the management of POGD. Therefore, it is essential to continue investigating effective interventions to reduce postoperative gastrointestinal impairment.

The primary objective of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) is to provide a non-invasive therapeutic modality through electrical stimulation of the auricular branch of the vagus nerve (9). Over the past two decades, taVNS has evolved into a significant focus of investigation in basic science, clinical research, and translational medicine. It has increasingly been recognized as a viable alternative to pharmacological treatments for a range of disorders, including epilepsy, depression, cardiovascular conditions, and gastrointestinal diseases (10).

As a non-invasive neuromodulation technique, taVNS demonstrates significant therapeutic potential for POGD. This narrative review aims to clarify the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying POGD, the anatomical basis of the vagus nerve, the technical parameters of taVNS, and its therapeutic mechanisms in mitigating postoperative gastrointestinal complications. The primary objective is to provide a comprehensive reference for clinical application and to support the integration of taVNS into standardized postoperative rehabilitation protocols.

Methods

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in the PubMed database to identify English-language articles without restrictions on publication year. The search strategy was based on a combination of keywords, including “vagus nerve stimulation,” “transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation,” “postoperative gastrointestinal dysfunction,” and “postoperative ileus.” All study designs were eligible for inclusion in this review, such as systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, descriptive and analytical studies, and narrative reviews.

Pathophysiological mechanisms underlying POGD

The etiology, duration, and severity of POGD are not yet fully understood. These factors are intricately associated with multiple physiological mechanisms, including spinal-gut sympathetic reflexes, sympathetic hyperactivity, inflammatory mediators, opioid administration, electrolyte disturbances, as well as anesthetic and surgical techniques. During laparotomy and abdominal surgery, activation of the sympathetic pathway and inhibitory non-adrenergic vagally mediated pathways has been consistently observed, contributing to gastrointestinal hypomotility intraoperatively and in the immediate postoperative period (11). Surgical incision of the abdominal wall and entry into the peritoneal cavity stimulate spinal afferent fibers, which synapse in the spinal cord and initiate an inhibitory cascade involving prevertebral adrenergic neurons, ultimately suppressing gastrointestinal motility (12). Furthermore, intense visceral afferent stimulation during manipulation of the intestinal loops activates supraspinal centers, leading to the recruitment of hypothalamic and pontine-medullary nuclei (12). This results in the engagement of an inhibitory non-adrenergic pathway via the vagus nerve, which reduces gut motility through the release of nitric oxide (NO) and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) (11).

The involvement of inflammatory mechanisms plays a critical role in the sustained and clinically significant impairment of gastrointestinal motility (13). Following surgical trauma and intestinal manipulation, the outer muscular layer mounts an inflammatory response mediated by a diverse array of immune cells, including macrophages, dendritic cells, mast cells, monocytes, and neutrophils (2). Among these, muscularis macrophages serve as key regulators of gastrointestinal homeostasis and are critically involved in the pathogenesis of motility disorders (14). Surgical manipulation activates muscularis macrophages, triggering an intracellular inflammatory cascade characterized by the upregulation of multiple transcription factors—such as NF-κB, STAT3, p38-MAPK, and early growth response protein 1—which subsequently drive the expression of pro-inflammatory genes (15–17). Consequently, the release of chemokines and cytokines—such as interleukin (IL)-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)—as well as kinetically active substances including NO and prostaglandins, is triggered (15, 18–20). During intestinal surgery, mast cells undergo degranulation and release mediators that promote local infiltration within the intestinal wall, thereby disrupting normal intestinal motility (21). Furthermore, reactive intestinal glial cells, neurons, smooth muscle cells, enteroendocrine cells, epithelial cells, and the microbiota present in the intestinal lumen collectively contribute to the pathogenesis of POGD. Enteric glial cells play a critical role in modulating neural circuit activity within the enteric nervous system—often referred to as the guts “little brain”—and are essential for maintaining normal motility. Surgical stress, excessive mechanical manipulation, ischemia/reperfusion injury, infections, and bacterial toxins can induce the transformation of enteric glial cells into a reactive phenotype, resulting in enteric gliosis. These glial responses contribute to neuroinflammation and enteric neuropathy, which clinically manifest as impaired motility, diarrhea, increased intestinal permeability, and abdominal or visceral pain (22).

The gut microbiota plays a crucial role in maintaining intestinal homeostasis. Exposure to surgical stressors—such as anesthesia, perioperative antibiotic administration, and invasive surgical procedures—induces significant alterations in the composition and functional activity of the gut microbial community. In particular, severe physiological trauma has been shown to markedly affect both the abundance and metabolic functionality of the gut microbiota. Gastrointestinal surgery increases intestinal permeability and impairs the integrity of the intestinal barrier, thereby promoting dysbiosis and facilitating bacterial translocation (23). The gut microbiota and its metabolites modulate intestinal motility through multiple mechanisms: (1) induction of dendritic cells to produce IL-12, which activates T helper type 1 (Th1) cells to secrete interferons (IFNs), subsequently stimulating mast cells and macrophages to release pro-inflammatory mediators such as NO, TNF, and IL-1β; (2) inhibition of tryptophan hydroxylase 1 (TPH1)-mediated synthesis of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) in enterochromaffin cells, where 5-HT regulates the release of neurotransmitters including substance P; (3) direct suppression of neuronal surface receptors, such as Toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and TLR4; and (4) inhibition of neuronal nuclear receptors, such as the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR), leading to reduced transcription of key neurotransmitter-related genes (24).

Anatomical basis of the auricular branch of the vagus nerve

The vagus nerve, the tenth cranial nerve, is the longest and most extensively distributed of all cranial nerves. As a mixed nerve, it consists of approximately 20% efferent fibers and 80% afferent fibers, thereby integrating both sensory and motor functions (25). Afferent sensory fibers convey somatic and visceral sensory information to the brainstem, while efferent visceral motor fibers modulate neurogenic, myogenic, and endocrine activities in target organs25. The vagus nerve mediates bidirectional communication between the central nervous system and multiple major anatomical structures, including the pharynx, larynx, trachea, heart, aorta, lungs, and the entire gastrointestinal tract—encompassing the esophagus, stomach, liver, pancreas, and spleen (26).

The anatomical structure of the external ear consists primarily of eight components: the helix, antihelix, triangular fossa, scapha, concha (divided into the cavum conchae and cymba conchae), tragus, antitragus, and the earlobe (27). Of particular note, the concha is the only superficial region where the auricular branch of the vagus nerve is distributed, rendering it an ideal site for transcutaneous electrical stimulation (28, 29). Human functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have shown that stimulation of the auricular branch of the vagus nerve induces significant activation in the “classical” central vagal projection areas, including the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS), locus coeruleus (LC), spinal trigeminal nucleus (STN), parabrachial nucleus, dorsal raphe, periaqueductal gray, amygdala, insula, nucleus accumbens, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, and paracentral lobule (30). In contrast, decreased activity has been observed in the hippocampus and hypothalamus (30). The dorsal motor nucleus (DMN) functions as the primary efferent center for central regulation of visceral parasympathetic activity and receives direct input from the NTS (31). These centrally integrated signals are subsequently relayed to peripheral organs innervated by the vagus nerve, leading to the release of neurotransmitters and modulation of multiple organ functions (27).

Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation

taVNS is an innovative, non-invasive neuromodulation technique that targets the auricular branch of the vagus nerve. Compared with invasive vagus nerve stimulation, this method is characterized by its favorable safety profile and high tolerability, with only mild and transient adverse effects—such as otalgia, headache, and paresthesia—reported in the literature (32). In the ongoing discussion regarding the optimal stimulation target for taVNS, current research primarily focuses on safety and efficacy (32). A systematic review reported an overall adverse event rate of 3.6% (20 out of 562 participants), with the most common events including ear discomfort, adhesive allergy, tinnitus, and insomnia (33). Given the traditional understanding that the efferent fibers of the vagus nerve innervating the heart are predominantly located on the right side, left-ear-only taVNS is generally considered safe in most studies. Nevertheless, evidence suggests that bilateral or right-sided stimulation does not lead to significant adverse effects (34). Stimulation parameters—such as optimal intensity, pulse width, waveform, and frequency—may vary across different populations and require further investigation.

Potential mechanisms of taVNS on POGD

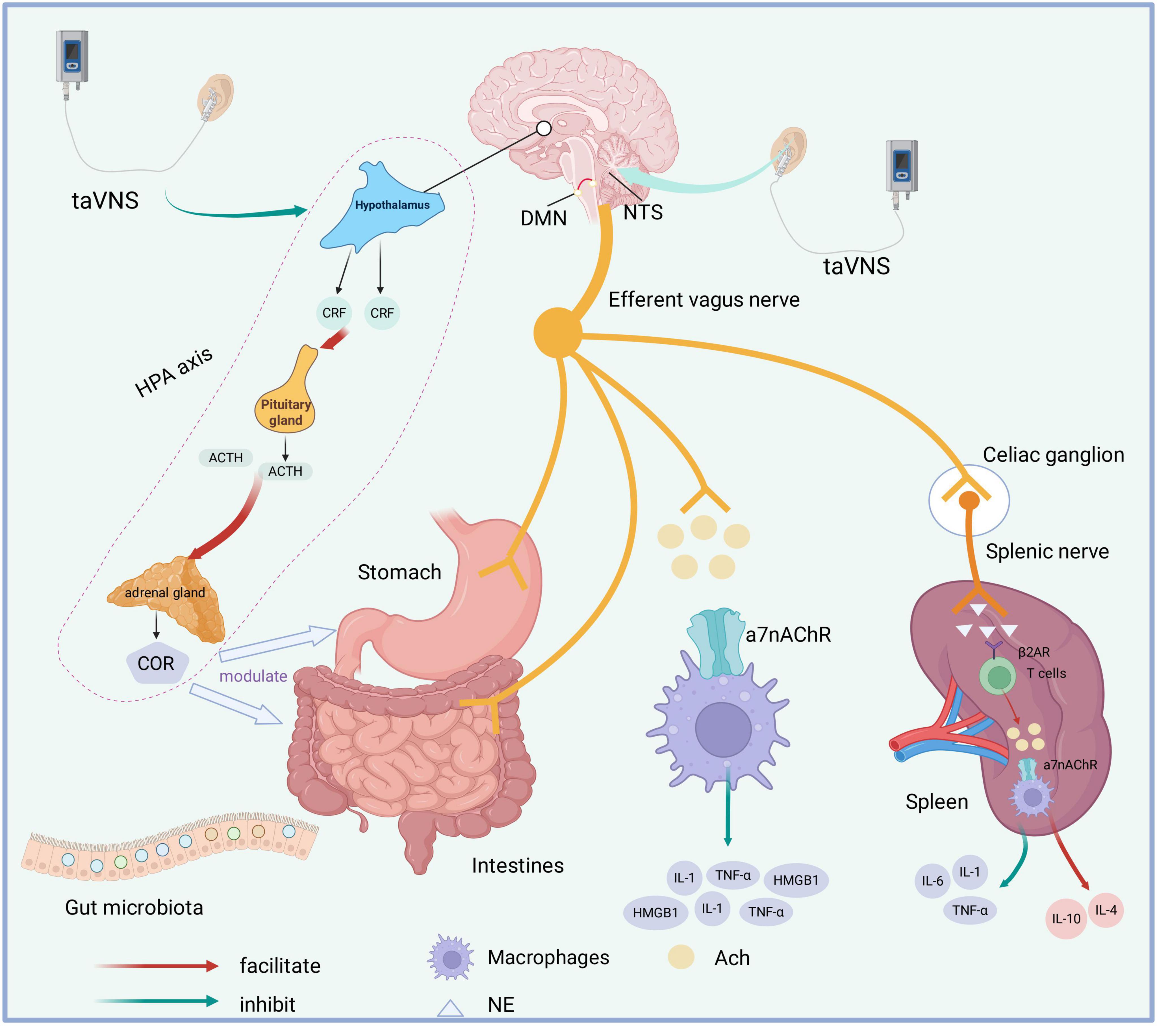

taVNS may improve POGD through multiple mechanisms, including activation of the vagus nerve, modulation of inflammatory responses, and regulation of neuroendocrine activity and gut microbiota (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Potential mechanisms of taVNS on POGD. TaVNS induces activation of NTS and DMN. Through the efferent pathway of the vagus nerve, it may directly modulate gastrointestinal motility and secretion, improve intestinal microbiota composition, and activate both the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway and splenic nerve afferent pathways. TaVNS inhibits HPA axis hyperactivity. DMN, dorsal motor nucleus; NTS, nucleus tractus solitarius; taVNS, transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation; POGD, postoperative gastrointestinal dysfunction; α7nAChR, nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α7 subunit; β2AR, β2-adrenergic receptor; ACh, acetylcholine; IL, interleukin; NE, norepinephrine; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; CRH, corticotropin-releasing factor; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; HPA axis, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis; HMGB1, high mobility group box 1;COR, cortisol.

taVNS facilitates gastrointestinal regulation

taVNS delivers electrical stimulation to the auricular branches of the vagus nerve, thereby activating afferent fibers. The generated signal is transmitted via the NTS to the DMN of the vagus nerve, leading to enhanced activity of efferent pathways. This mechanism significantly increases parasympathetic tone and promotes gastrointestinal motility and secretory function. In a study conducted on healthy volunteers, cold stimulation was shown to reduce the percentage of normal gastric slow waves and suppress vagal activity; however, this impairment was subsequently ameliorated by taVNS treatment (35). taVNS has been demonstrated to enhance vagal activity, improve gastric accommodation, and increase the proportion of normal gastric slow waves in patients with functional dyspepsia (FD) (36). Furthermore, non-invasive auricular vagus nerve stimulation has been found to accelerate colonic and whole-gut transit times and restore enteric neural function through central and vagal efferent pathways, effectively alleviating constipation symptoms in a rodent model of opioid-induced constipation (OIC) (37).

taVNS modulates neuroendocrine function

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis constitutes a central component of the neuroendocrine system, essential for regulating stress responses, immune function, and metabolic homeostasis. Under stressful conditions, such as those experienced during abdominal surgery and associated pain, corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) neurons—predominantly located in the parvocellular region of the paraventricular nucleus (PVN)—are activated (38). This activation leads to the release of CRF, which stimulates the anterior pituitary gland to secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). In turn, ACTH promotes cortisol production in the adrenal cortex and facilitates adrenaline release from the adrenal medulla (39). Furthermore, CRF signaling pathways in both the central nervous system and the gastrointestinal tract are critically involved in mediating stress-induced changes in gastrointestinal motility (40). Intravenous administration of CRF has been demonstrated to induce both paracellular and transcellular intestinal barrier dysfunction. taVNS has been shown to reduce paracellular permeability in the small intestine, thereby improving intestinal barrier integrity. Furthermore, taVNS effectively suppresses hyperactivity of the HPA axis (41). Elevated cortisol levels are associated with alterations in gut microbiota composition and increased intestinal permeability, which may promote systemic inflammation and contribute to central nervous system dysfunction and related disorders (42). A study investigating the antidepressant-like effects of three different frequencies of taVNS in rats subjected to chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS) revealed that 20 Hz taVNS significantly reduced plasma corticosterone and ACTH levels, leading to downregulation of HPA axis activity (43). In a FD rat model, taVNS has also been found to attenuate HPA axis hyperactivation (44).

taVNS modulates immune function

In 2002, Tracey introduced the concept of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway (CAP), a mechanism through which the parasympathetic nervous system modulates inflammatory responses via efferent vagus nerve signaling (45). Activation of the CAP is primarily mediated by the interaction between acetylcholine (ACh) and α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (α7nAChR) expressed on macrophages (46), leading to the suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokine release, includingTNF-α, IL-1β, and high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1). Although the vagus nerve does not innervate gut-resident macrophages directly, it communicates with enteric neurons expressing neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), VIP, and choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), which are located in the muscularis externa in close proximity to α7nAChR-expressing macrophages (47). In a murine model of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced endotoxemia, taVNS at 15 Hz was shown to attenuate inflammation by activating α7nAChR and reducing TNF-α and IL-1β levels (48). Moreover, taVNS has been demonstrated to alleviate oxidative stress and inhibit mitochondrial apoptosis in a 1,2-dimethylhydrazine (DMH)-induced colon cancer model (49). Furthermore, taVNS upregulates the CAP, as evidenced by increased expression of α7nAChR and decreased expression of nuclear factor kappa B p65 (NF-κB p65), TNF-α, and HMGB1 at both protein and mRNA levels (49).

A substantial body of research has consistently demonstrated that neural stimulation activates splenic sympathetic nerve fibers, resulting in the release of norepinephrine. This neurotransmitter subsequently binds to β2-adrenergic receptors on acetylcholine-producing T cells, thereby promoting the secretion of Ach (50). The released ACh then interacts with α7nAChR expressed on splenic macrophages, leading to effective suppression of TNF-α production by these immune cells.

taVNS alleviates gut microbiota dysbiosis

The human gut microbiota harbors trillions of microorganisms that play a critical role in modulating both local and systemic immune responses (51). In the context of ischemic stroke, taVNS has been demonstrated to attenuate the systemic inflammatory response following cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Furthermore, taVNS ameliorates gut microbiota dysbiosis and strengthens the integrity of both the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and intestinal barrier by regulating intestinal microbial imbalances and inhibiting mast cell degranulation, thereby reducing translocation of LPS from the gut (21). In a murine model of constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-C), taVNS significantly decreased the abdominal withdrawal reflex (AWR) score relative to sham stimulation, indicating effective alleviation of visceral hyperalgesia (52). Additionally, taVNS restored the abundance of Lactobacillus and increased that of Bifidobacterium at the genus level. It also enhanced the population of c-kit-positive interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) in the myenteric plexus region in IBS-C mice (53). A single-center randomized controlled trial on the effects of taVNS in patients with IBS-C demonstrated significant increases in Bifidobacterium levels and concentrations of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including acetic, butyric, and propionic acids, following four weeks of treatment. Furthermore, taVNS was associated with reduced levels of tryptophan-derived metabolites, such as 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid and L-tryptophan (53). Bifidobacterium has been shown to upregulate the activity of suppressive regulatory T cells, maintain intestinal barrier integrity, modulate dendritic cell and macrophage functions, and attenuate intestinal Th2 and Th17 immune responses (54).

taVNS for the treatment of gastrointestinal dysfunction

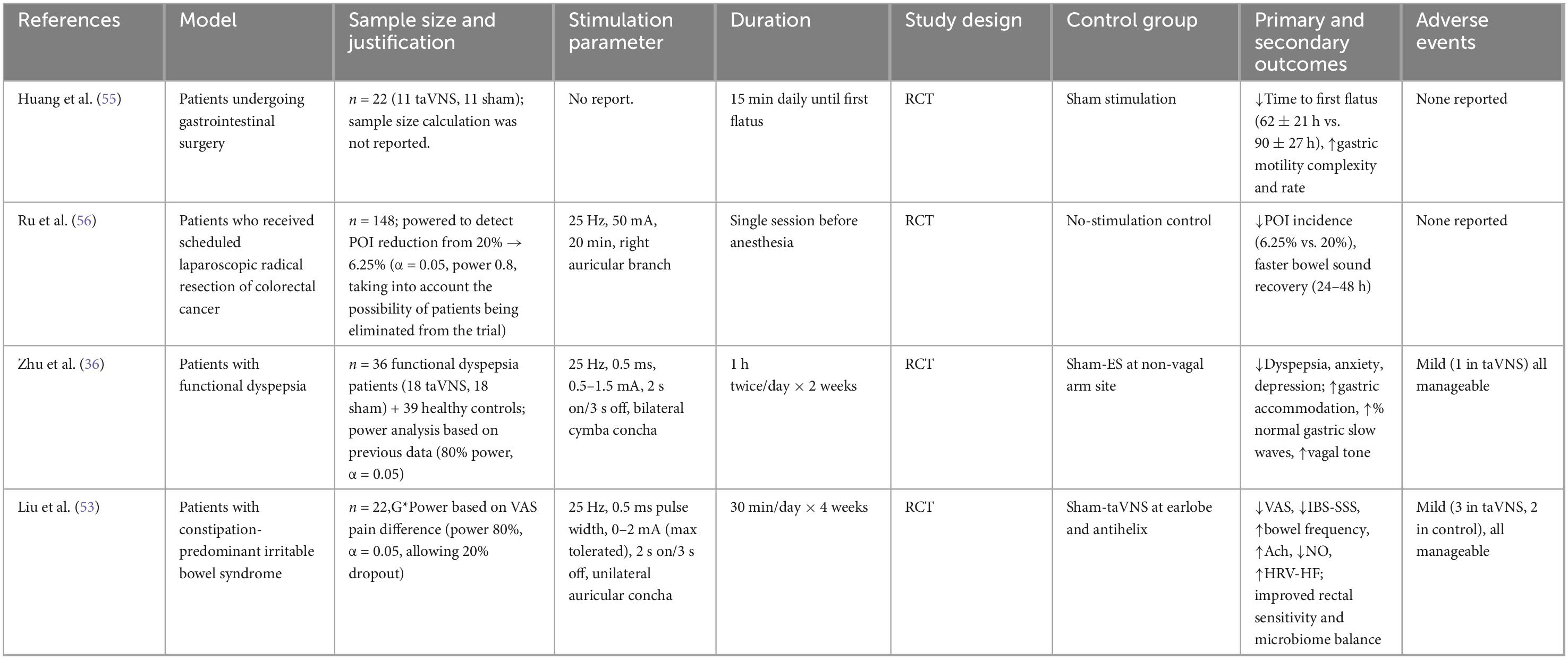

In recent years, numerous clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of taVNS in treating gastrointestinal dysfunction, as summarized in Table 1. Recent studies demonstrate that taVNS effectively improves gastrointestinal motility and symptoms across disorders such as FD, IBS-C, and POI. By enhancing vagal efferent activity and restoring gut–brain axis balance, taVNS accelerates recovery, normalizes gastric rhythms, and alleviates discomfort (36, 53, 55, 56). Importantly, all studies reported excellent safety, with no serious adverse events and only mild, transient local discomfort. Collectively, these findings support taVNS as a clinically meaningful and well-tolerated intervention capable of improving gastrointestinal function through modulation of autonomic and enteric neural pathways, warranting further large-scale, long-term trials to confirm its therapeutic efficacy and optimize stimulation parameters.

Table 1. Summary of clinical trials on transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) for gastrointestinal dysfunction.

Other methods for managing POGD

Electroacupuncture

Electroacupuncture is a contemporary clinical therapeutic approach that integrates traditional acupuncture techniques with the precise delivery of electrical stimulation, allowing for standardized and quantifiable control of stimulation parameters such as frequency and intensity. Electroacupuncture has been shown to effectively reduce postoperative nausea and vomiting, accelerate the time to first flatus and defecation, and alleviate postoperative gastrointestinal dysfunction (5, 57, 58). Electroacupuncture is invasive and involves risks such as local pain, bleeding and infection. Due to the differences in acupuncture culture, its application and promotion in other countries have been restricted.

Dexmedetomidine

Dexmedetomidine, a selective agonist of alpha2-adrenergic receptors, is often employed as an anesthesia adjunct during the perioperative stage. This is because it possesses anti-inflammatory characteristics, offers stress-reducing advantages, and exerts a beneficial impact on the vagus nerve. A multicenter clinical trial the administration of intraoperative dexmedetomidine reduced the time to first flatus, time to first feces, and length of stay after abdominal surgery without affecting the I-FEED score (7). The adverse effects of dexmedetomidine are primarily confined to hemodynamic alterations, including bradycardia, transient hypertension, and hypotension. There was no significant difference in these adverse events between the 2 groups (7). A systematic review and meta-analysis suggested that perioperative administration of dexmedetomidine can facilitate the recovery of gastrointestinal function and shorten the length of hospital stay for patients after abdominal surgery (59). However, the optimal dose and timing of dexmedetomidine need further investigation.

Chewing gum

Chewing gum can stimulate the vagus nerve in the head and neck region, promote gastrointestinal motility, and reduce the transmission of sympathetic neural signals (60). Concurrently, it enhances the secretion of saliva and pancreatic juice (60). Multiple meta-analysis results have shown that chewing gum can reduce postoperative nausea and vomiting, shorten the time for the first defecation and flatus, and accelerate the recovery of gastrointestinal function (60–62). Using chewing gum as an auxiliary measure in routine postoperative care to promote the recovery of the gastrointestinal tract after surgery requires more high-quality clinical research.

Intravenous lidocaine

Lidocaine is a local anesthetic agent known for its anti-inflammatory and tissue-protective properties. It has been administered intravenously as an adjunct in general anesthesia across various surgical procedures, demonstrating efficacy in reducing early postoperative pain scores and decreasing opioid consumption. Some single-center randomized controlled trials have shown that intravenous administration of lidocaine during the perioperative period can lead to faster recovery of intestinal function, reduced pain, and shorter hospital stay (63–65). However, the results of a multicenter randomized study showed that perioperative administration of lidocaine did not improve the recovery of intestinal function within 72 h (8). Based on this, the current evidence does not support the use of conventional intravenous lidocaine to accelerate postoperative gastrointestinal recovery.

Coffee-based beverage

Following laparoscopic gynecological surgery, coffee consumption was associated with a reduced time to first flatus, earlier time to first bowel movement, and shorter time to tolerance of solid food, thereby promoting the recovery of gastrointestinal function (66). During a cesarean section, the consumption of coffee can also facilitate the recovery of gastrointestinal functions (67). A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials revealed that consuming coffee following surgery was associated with a reduced time to first bowel movement after elective colorectal procedures (68). However, the optimal dosage of coffee, whether it contains caffeine or not, as well as the impact of other chemical components in coffee on the recovery of gastrointestinal function still require further exploration.

Alvimopan

In 2008, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved alvimopan, an oral, peripherally acting opioid μ-receptor antagonist, for the acceleration of gastrointestinal recovery in patients undergoing intestinal resection surgery (69). Alvimopan has the most consistent benefit for open bowel resections but is costly and not universally indicated.

Discussion and conclusion

Current limitations in clinical application

At present, the application of taVNS in POGD is still in its early exploratory stages. Although taVNS has shown potential therapeutic value for gastrointestinal dysfunction, its clinical application faces several challenges. Firstly, Mechanistic clarity vs clinical translation. Although there is a satisfactory explanation for the vagus nerve regulation at the mechanism level, the conversion of these physiological changes into meaningful clinical outcomes still requires validation in large-scale surgical samples. Second, the evidence of the research and the quality issues. Published studies are few, typically small, and heterogeneous in terms of surgical populations, the timing of stimulation, and co-interventions. Third, the scope of the research subjects is rather limited. The majority of existing studies concentrate on elective abdominal procedures among relatively healthy adult populations. However, there remains a paucity of evidence regarding high-risk patient groups—such as individuals with frailty or severe cardiopulmonary comorbidities—as well as emergency surgeries and non-abdominal operations where POGD still occurs, including spinal surgeries. Fourth, within the framework of the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) program, interventions such as early enteral feeding, multimodal analgesia, regional anesthesia, and early mobilization have been shown to significantly influence gastrointestinal function recovery. Inconsistent application or inadequate reporting of these components may confound the assessment of the independent effect of taVNS. Fifth, safety characterization and device considerations. Reported adverse events are usually mild (local irritation, lightheadedness), but data in patients with implanted cardiac devices, significant bradyarrhythmias, or skin disorders around the ear are limited.

Feasibility in perioperative settings

Applying taVNS in the perioperative context holds promise but also presents practical considerations:

1. Timing of intervention: There is a question of when to apply stimulation — pre-operative, intraoperative, early postoperative.

2. Integration with standard perioperative care: taVNS should be incorporated into established analgesic protocols, ERAS pathways, and routine patient monitoring procedures. It is essential to provide healthcare personnel with comprehensive training on proper electrode placement—targeting the auricular branch of the vagus nerve—and on the ongoing assessment of device functionality to ensure treatment efficacy and patient safety.

3. Device logistics and patient state: During equipment transportation and patient management, post-operative patients may present with dressings, attached monitoring leads, or symptoms such as pain or sedation. These factors can influence the placement of ear electrodes, as well as patient compliance and comfort. Additionally, it is essential to monitor for stimulation-related adverse reactions, including bradycardia and hypotension.

4. Workflow and cost-effectiveness: To achieve the promotion, this intervention measure must not excessively prolong the work flow during the surgery, nor require expensive equipment.

5. Patient selection: Identifying which patients (type of surgery, risk of POGD) are most likely to benefit is key.

Standardization challenges

Standardized treatment protocols are lacking. key stimulation parameters—such as frequency, intensity, and duration—have not been systematically established, warranting rigorous optimization to improve therapeutic outcomes.

Frequency: In the existing literature, the stimulation frequencies employed in taVNS exhibit considerable variability, ranging from 1 to 30 HZ. To establish a standardized frequency range for clinical application, further research is required, as variations in frequency may significantly influence treatment efficacy and patient tolerance.

Intensity: Numerous studies employ the “perceivable yet comfortable” paradigm, calibrating stimulation intensity according to individual sensory thresholds. However, inter-individual variability among patients and fluctuations during the treatment process may influence the consistency of this approach. Consequently, there is a need for a more standardized methodology to measure and adjust stimulation intensity, ensuring reproducible outcomes while minimizing discomfort or overstimulation.

Duration: The duration of sessions and the timing of stimulation also differ between studies. There is no relevant literature available that specifies the appropriate timing or duration for applying the stimulus.

Conclusion

As a non-invasive neuromodulation technique, taVNS has shown promising potential in the treatment of gastrointestinal dysfunction. It may improve postoperative gastrointestinal function through multiple mechanisms, including activation of the vagus nerve, modulation of inflammatory responses, and regulation of neuroendocrine activity and gut microbiota. However, existing research remains preliminary, and further exploration of its underlying mechanisms, as well as well-designed, high-quality clinical trials, is required to support its broader clinical implementation.

Author contributions

LZ: Writing – original draft. QZ: Writing – original draft. XY: Writing – original draft. YCa: Writing – original draft. YCh: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. ZL: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. YS: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. KF: Writing – original draft, Data curation. ML: Writing – original draft, Methodology. LQ: Writing – original draft, Methodology. YW: Methodology, Writing – original draft. CD: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. YR: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JW: Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. HL: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This trial has received partial support from grants provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC8257050478, NSFC82171227, and NSFC81300957 to HL), the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (LY22H090019 to HL), the Science and Technology Special Program of Huzhou (2024GZ05 to HL), the open project fund of the Key Laboratory for NeuroInformation of Ministry of Education (202311KFY00102), the Zhejiang Province cerebrovascular disease diagnosis and treatment of traditional Chinese medicine multidisciplinary innovation team project, and the “Integration of Medicine, Industry and information” Collaborative Innovation Center Fund of Yangtze Delta Region Institute (Huzhou), University of Electronic Science and Technology of China- Huzhou Central Hospital.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to our anesthetic colleagues for their invaluable support and assistance to complete the review.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Xue J, Xu Z, Wang Q, Hou H, Wei L, Zhang J, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for prevention and treatment of postoperative gastrointestinal disorder with Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine (2023). J Evid Based Med. (2024) 17:207–23. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12587

2. Mazzotta E, Villalobos-Hernandez EC, Fiorda-Diaz J, Harzman A, Christofi FL. Postoperative ileus and postoperative gastrointestinal tract dysfunction: pathogenic mechanisms and novel treatment strategies beyond colorectal enhanced recovery after surgery protocols. Front Pharmacol. (2020) 11:583422. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.583422

3. Asgeirsson T, El-Badawi KI, Mahmood A, Barletta J, Luchtefeld M, Senagore AJ. Postoperative ileus: it costs more than you expect. J Am Coll Surg. (2010) 210:228–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.09.028

4. Delaney CP, Senagore AJ, Viscusi ER, Wolff BG, Fort J, Du W, et al. Postoperative upper and lower gastrointestinal recovery and gastrointestinal morbidity in patients undergoing bowel resection: pooled analysis of placebo data from 3 randomized controlled trials. Am J Surg. (2006) 191:315–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.10.026

5. Wang Y, Yang JW, Yan SY, Lu Y, Han JG, Pei W, et al. Electroacupuncture vs Sham electroacupuncture in the treatment of postoperative ileus after laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer: a multicenter, randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. (2023) 158:20–7. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2022.5674

6. Kane TD, Tubog TD, Schmidt JR. The use of coffee to decrease the incidence of postoperative ileus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Perianesth Nurs. (2020) 35:171–7.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2019.07.004.

7. Lu Y, Fang PP, Yu YQ, Cheng XQ, Feng XM, Wong GTC, et al. Effect of intraoperative dexmedetomidine on recovery of gastrointestinal function after abdominal surgery in older adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. (2021) 4:e2128886. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.28886

8. Paterson H, Vadiveloo T, Innes K, Balfour A, Atter M, Stoddart A, et al. Intravenous lidocaine for gut function recovery in colonic surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2025) 333:39–48. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.23898

9. Chen M, Yu L, Ouyang F, Liu Q, Wang Z, Wang S, et al. The right side or left side of noninvasive transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation: based on conventional wisdom or scientific evidence? Int J Cardiol. (2015) 187:44–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.351

10. Wang Y, Li SY, Wang D, Wu MZ, He JK, Zhang JL, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation: from concept to application. Neurosci Bull. (2021) 37:853–62. doi: 10.1007/s12264-020-00619-y

11. Boeckxstaens GE, Hirsch DP, Kodde A, Moojen TM, Blackshaw A, Tytgat GN, et al. Activation of an adrenergic and vagally-mediated NANC pathway in surgery-induced fundic relaxation in the rat. Neurogastroenterol Motil. (1999) 11:467–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.1999.00172.x

12. Boeckxstaens GE, de Jonge WJ. Neuroimmune mechanisms in postoperative ileus. Gut. (2009) 58:1300–11. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.169250

13. Hussain Z, Park H. Inflammation and Impaired Gut Physiology in Post-operative Ileus: mechanisms and the Treatment Options. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. (2022) 28:517–30. doi: 10.5056/jnm22100

14. De Schepper S, Stakenborg N, Matteoli G, Verheijden S, Boeckxstaens GE. Muscularis macrophages: key players in intestinal homeostasis and disease. Cell Immunol. (2018) 330:142–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2017.12.009

15. Yang NN, Yang JW, Ye Y, Huang J, Wang L, Wang Y, et al. Electroacupuncture ameliorates intestinal inflammation by activating α7nAChR-mediated JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway in postoperative ileus. Theranostics. (2021) 11:4078–89. doi: 10.7150/thno.52574

16. Liu T, Xu M, Shi Z, Li M, Wang R, Shi Y, et al. Shenhuang plaster ameliorates the Inflammation of postoperative ileus through inhibiting PI3K/Akt/NF-κB pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. (2022) 156:113922. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113922

17. Wehner S, Straesser S, Vilz TO, Pantelis D, Sielecki T, de la Cruz VF, et al. Inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway as prophylaxis of postoperative ileus in mice. Gastroenterology. (2009) 136:619–29. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.017

18. Docsa T, Bhattarai D, Sipos A, Wade CE, Cox CS, Uray K. CXCL1 is upregulated during the development of ileus resulting in decreased intestinal contractile activity. Neurogastroenterol Motil. (2020) 32:e13757. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13757

19. van Beekum CJ, Willis MA, von Websky MW, Sommer NP, Kalff JC, Wehner S, et al. Electrical vagus nerve stimulation as a prophylaxis for SIRS and postoperative ileus. Auton Neurosci. (2021) 235:102857. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102857

20. Bessard A, Cardaillac C, Oullier T, Cenac N, Rolli-Derkinderen M, Neunlist M, et al. Alterations of prostanoid expression and intestinal epithelial barrier functions in ileus. J Surg Res. (2024) 296:165–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2023.12.018

21. Wang Y, Tan Q, Pan M, Yu J, Wu S, Tu W, et al. Minimally invasive vagus nerve stimulation modulates mast cell degranulation via the microbiota-gut-brain axis to ameliorate blood-brain barrier and intestinal barrier damage following ischemic stroke. Int Immunopharmacol. (2024) 132:112030. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2024.112030

22. Linan-Rico A, Ochoa-Cortes F, Schneider R, Christofi FL. Mini-review: enteric glial cell reactions to inflammation and potential therapeutic implications for GI diseases, motility disorders, and abdominal pain. Neurosci Lett. (2023) 812:137395. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2023.137395

23. Reddy BS, Gatt M, Sowdi R, MacFie J. Surgical manipulation of the large intestine increases bacterial translocation in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. Colorectal Dis. (2006) 8:596–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.01024.x

24. Ma T, Xue X, Tian H, Zhou X, Wang J, Zhao Z, et al. Effect of the gut microbiota and their metabolites on postoperative intestinal motility and its underlying mechanisms. J Transl Med. (2023) 21:349. doi: 10.1186/s12967-023-04215-2

25. Berthoud HR, Neuhuber WL. Functional and chemical anatomy of the afferent vagal system. Auton Neurosci. (2000) 85:1–17. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(00)00215-0

26. Zou N, Zhou Q, Zhang Y, Xin C, Wang Y, Claire-Marie R, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation as a novel therapy connecting the central and peripheral systems: a review. Int J Surg. (2024) 110:4993–5006. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000001592

27. Butt MF, Albusoda A, Farmer AD, Aziz Q. The anatomical basis for transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation. J Anat. (2020) 236:588–611. doi: 10.1111/joa.13122

28. Kaniusas E, Kampusch S, Tittgemeyer M, Panetsos F, Gines RF, Papa M, et al. Current directions in the auricular vagus nerve stimulation ii - an engineering perspective. Front Neurosci. (2019) 13:772. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00772

29. Yakunina N, Kim SS, Nam EC. Optimization of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation using functional MRI. Neuromodulation. (2017) 20:290–300. doi: 10.1111/ner.12541

30. Frangos E, Ellrich J, Komisaruk BR. Non-invasive access to the vagus nerve central projections via electrical stimulation of the external Ear: fmri evidence in humans. Brain Stimul. (2015) 8:624–36. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2014.11.018

31. Rogers RC, Kita H, Butcher LL, Novin D. Afferent projections to the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. Brain Res Bull. (1980) 5:365–73. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(80)80006-2

32. Kim AY, Marduy A, de Melo PS, Gianlorenco AC, Kim CK, Choi H, et al. Safety of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:22055. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-25864-1

33. Veldman F, Hawinkels K, Keszthelyi D. Efficacy of vagus nerve stimulation in gastrointestinal disorders: a systematic review. Gastroenterol Rep. (2025) 13:goaf009. doi: 10.1093/gastro/goaf009

34. Yap JYY, Keatch C, Lambert E, Woods W, Stoddart PR, Kameneva T. Critical review of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation: challenges for translation to clinical practice. Front Neurosci. (2020) 14:284. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00284

35. Zhu Y, Xu F, Sun C, Xu W, Li M, Gong Y, et al. Noninvasive transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation improves gastric slow waves impaired by cold stress in healthy subjects. Neuromodulation. (2023) 26:1851–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neurom.2022.03.010

36. Zhu Y, Xu F, Lu D, Rong P, Cheng J, Li M, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagal nerve stimulation improves functional dyspepsia by enhancing vagal efferent activity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. (2021) 320:G700–11. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00426.2020

37. Zhang Y, Lu T, Meng Y, Maisiyiti A, Dong Y, Li S, et al. Auricular vagal nerve stimulation improves constipation by enhancing colon motility via the central-vagal efferent pathway in opioid-induced constipated rats. Neuromodulation. (2021) 24:1258–68. doi: 10.1111/ner.13406

38. Rivest S, Lacroix S, Vallières L, Nadeau S, Zhang J, Laflamme N. How the blood talks to the brain parenchyma and the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus during systemic inflammatory and infectious stimuli. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. (2000) 223:22–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1373.2000.22304.x

39. Hosoi T, Okuma Y, Nomura Y. Electrical stimulation of afferent vagus nerve induces IL-1beta expression in the brain and activates HPA axis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. (2000) 279:R141–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.1.R141

40. Taché Y, Bonaz B. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptors and stress-related alterations of gut motor function. J Clin Invest. (2007) 117:33–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI30085

41. Mogilevski T, Rosella S, Aziz Q, Gibson PR. Transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation protects against stress-induced intestinal barrier dysfunction in healthy adults. Neurogastroenterol Motil. (2022) 34:e14382. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14382

42. Mangiola F, Ianiro G, Franceschi F, Fagiuoli S, Gasbarrini G, Gasbarrini A. Gut microbiota in autism and mood disorders. World J Gastroenterol. (2016) 22:361–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i1.361

43. Li S, Wang Y, Gao G, Guo X, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation at 20 Hz improves depression-like behaviors and down-regulates the hyperactivity of HPA Axis in chronic unpredictable mild stress model rats. Front Neurosci. (2020) 14:680. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00680

44. Hou L, Rong P, Yang Y, Fang J, Wang J, Wang Y, et al. Auricular vagus nerve stimulation improves visceral hypersensitivity and gastric motility and depression-like behaviors via vago-vagal pathway in a rat model of functional dyspepsia. Brain Sci. (2023) 13:253. doi: 10.3390/brainsci13020253

45. Alen NV. The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway in humans: state-of-the-art review and future directions. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2022) 136:104622. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104622

46. Matteoli G, Gomez-Pinilla PJ, Nemethova A, Di Giovangiulio M, Cailotto C, van Bree SH, et al. A distinct vagal anti-inflammatory pathway modulates intestinal muscularis resident macrophages independent of the spleen. Gut. (2014) 63:938–48. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304676

47. Cailotto C, Gomez-Pinilla PJ, Costes LM, van der Vliet J, Di Giovangiulio M, Némethova A, et al. Neuro-anatomical evidence indicating indirect modulation of macrophages by vagal efferents in the intestine but not in the spleen. PLoS One. (2014) 9:e87785. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087785

48. Go YY, Ju WM, Lee CM, Chae SW, Song JJ. Different transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation parameters modulate the anti-inflammatory effects on lipopolysaccharide-induced acute inflammation in mice. Biomedicines. (2022) 10:247. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10020247

49. Rawat JK, Roy S, Singh M, Guatam S, Yadav RK, Ansari MN, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation regulates the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway to counteract 1, 2-dimethylhydrazine induced colon carcinogenesis in albino wistar rats. Front Pharmacol. (2019) 10:353. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00353

50. Olofsson PS, Katz DA, Rosas-Ballina M, Levine YA, Ochani M, Valdés-Ferrer SI, et al. α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7nAChR) expression in bone marrow-derived non-T cells is required for the inflammatory reflex. Mol Med. (2012) 18:539–43. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00405

51. Wang J, Zhu N, Su X, Gao Y, Yang R. Gut-microbiota-derived metabolites maintain gut and systemic immune homeostasis. Cells. (2023) 12:793. doi: 10.3390/cells12050793

52. Liu J, Dai Q, Qu T, Ma J, Lv C, Wang H, et al. Ameliorating effects of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on a mouse model of constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Neurobiol Dis. (2024) 193:106440. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2024.106440

53. Liu J, Lv C, Yin M, Zhu M, Wang B, Tian J, et al. Efficacy and safety of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation in patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a single-center. Single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. (2024) 120:2139–53. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000003257

54. Gavzy SJ, Kensiski A, Lee ZL, Mongodin EF, Ma B, Bromberg JS. Bifidobacterium mechanisms of immune modulation and tolerance. Gut Microbes. (2023) 15:2291164. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2023.2291164

55. Huang CH, Wu CH, Chan RH, Chen CH, Lin BW, Lin CK. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation accelerates postoperative ileus recovery by enhancing gastric motility complexity: a clinical study. Brain Stimul. (2025) 18:1091–3. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2025.05.002

56. Ru O, Jin X, Qu L, Long D, Liu M, Cheng L, et al. Low-intensity transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation reduces postoperative ileus after laparoscopic radical resection of colorectal cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Minerva Anestesiol. (2023) 89:149–56. doi: 10.23736/S0375-9393.22.16735-0

57. Chen HT, Hung KC, Huang YT, Wu JY, Hsing CH, Lin CM, et al. Efficacy of electroacupuncture in improving postoperative ileus in patients receiving colorectal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. (2024) 110:1113–25. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000848

58. Zhou T, Hou H, Cairen Z, Wang Y, Wang P, Ge L, et al. Comparative effectiveness of acupoint stimulation for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting after general anesthesia: a network meta-analysis of randomized trials. Int J Surg. (2025) 111:1330–47. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000001976

59. Liu Y, Liang H, Sun Y, Liu W, Ye L, He W, et al. Effect of perioperative dexmedetomidine on recovery of postoperative gastrointestinal function in patients with general anesthesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Anesthesiol. (2024) 24:479. doi: 10.1186/s12871-024-02868-0

60. Li C, Nair A, Zhu XM, Leung M, Leung G, Catapano J, et al. The effects of gum chewing in the postoperative-period: a systematic review and meta-analysis. ANZ J Surg. (2025) 95:1320–8. doi: 10.1111/ans.70238

61. Lew SL, Cheng LJ, Yap SY, Liaw YQ, Park J, Lau ST. Effect of chewing gum on clinical outcomes and postoperative recovery in adult patients after gastrointestinal surgery: an umbrella review. Int J Surg. (2025) 111:3481–93. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000002332

62. Douligeris A, Diakosavvas M, Kathopoulis N, Kypriotis K, Mortaki A, Angelou K, et al. The effect of postoperative gum chewing on gastrointestinal function following laparoscopic gynecological surgery. a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. (2023) 30:783–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2023.06.015

63. Sun Y, Li T, Wang N, Yun Y, Gan TJ. Perioperative systemic lidocaine for postoperative analgesia and recovery after abdominal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Dis Colon Rectum. (2012) 55:1183–94. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318259bcd8

64. Zhang L, Wei P, Wang H, Zhang Y, Wang H, Xu Y, et al. Effect of perioperative lidocaine application on inflammatory factors, immune function, and quality of early postoperative recovery in patients undergoing video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Med Res. (2025) 30:1072. doi: 10.1186/s40001-025-03119-9

65. Xu JF, Du MC, Chen Y, Hu Y, Long X, Jiang JJ, et al. Intravenous lidocaine enhances the efficacy of ondansetron and dexamethasone in postoperative vomiting prophylaxis among high-risk children. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:30168. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-16367-w

66. Gungorduk K, Paskal EK, Demirayak G, Köseoğlu SB, Akbaba E, Ozdemir IA. Coffee consumption for recovery of intestinal function after laparoscopic gynecological surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Surg. (2020) 82:130–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.08.016

67. Tüzmen HD, Yüksel H, Yazar M, Sayar S, Horasanlı JE. The effect of coffee consumption on postoperative pain and bowel motility following cesarean section: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. (2025) 314:114723. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2025.114723

68. Zhu J, Xu W, Sun Q, Geng J, Yu Y, Zhao Z. Effect of coffee consumption on postoperative ileus after colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastroenterol Res Pract. (2022) 2022:8029600. doi: 10.1155/2022/8029600

Keywords: postoperative gastrointestinal dysfunction, postoperative ileus, transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation, vagus nerve, pathophysiological mechanisms

Citation: Zhang L, Zhang Q, Yin X, Cao Y, Chen Y, Li Z, Shen Y, Fan K, Liu M, Qian L, Wang Y, Dai C, Ren Y, Wei J and Liu H (2025) Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation as an innovative approach for managing perioperative gastrointestinal dysfunction: a narrative review. Front. Med. 12:1719275. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1719275

Received: 15 October 2025; Revised: 12 November 2025; Accepted: 17 November 2025;

Published: 03 December 2025.

Edited by:

Diansan Su, Zhejiang University, ChinaReviewed by:

Yangzi Zhu, Xuzhou Central Hospital, ChinaMaisiyiti Alimujiang, People’s Hospital of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China

Copyright © 2025 Zhang, Zhang, Yin, Cao, Chen, Li, Shen, Fan, Liu, Qian, Wang, Dai, Ren, Wei and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jingqiu Wei, NjQ5MzkxNjEzQHFxLmNvbQ==; He Liu, bGgxMjEwNjFAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Ling Zhang

Ling Zhang Qin Zhang

Qin Zhang Xuefeng Yin1,2,3†

Xuefeng Yin1,2,3† Keyu Fan

Keyu Fan He Liu

He Liu