Abstract

Background:

Drug–food interactions (DFIs) can significantly affect therapeutic efficacy and patient safety. However, there is limited evidence regarding healthcare professionals’ knowledge and practices concerning DFIs, particularly in Saudi Arabia. This study aimed to evaluate the awareness, counseling practices, and perceived barriers among healthcare professionals regarding DFIs, with a focus on cultural and educational dimensions.

Methods:

A cross-sectional survey was conducted among 385 healthcare professionals in Saudi Arabia using a structured self-administered questionnaire. The survey assessed knowledge of DFIs, sources of information, counseling behavior, reporting practices, and the perceived need for additional training. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize findings.

Results:

A total of 231 respondents (60.0%) demonstrated limited knowledge regarding DFI mechanisms. More than half (51.4%) reported receiving no formal instruction on DFIs, and 146 participants (37.9%) relied primarily on informal sources. Only 164 professionals (42.6%) indicated that they routinely counseled patients about DFIs involving traditional foods or herbal products. Notably, only 73 participants (19.0%) had ever reported a DFI-related adverse event. These patterns suggest possible deficiencies in current curricular content, continuing professional education, and cultural alignment of counseling practices.

Conclusion:

The findings indicate potential gaps in healthcare professionals’ preparedness to manage DFIs effectively, particularly in relation to traditional food practices and pharmacovigilance. Tentatively, this may reflect shortcomings in both undergraduate curricula and post-graduate training programs. There may be value in integrating culturally sensitive DFI training into pharmacy and medical education, supported by continuing professional development initiatives. National guidelines tailored to local dietary contexts and patient beliefs could also enhance the quality of DFI-related counseling and reporting.

Introduction

Understanding drug–food interactions (DFIs) is essential to optimizing therapeutic outcomes and ensuring medication safety. DFIs can alter drug absorption, metabolism, and overall efficacy, potentially leading to therapeutic failures or adverse reactions. Comprehensive knowledge of DFIs is required among healthcare professionals, particularly pharmacists, physicians, and nurses, to ensure effective management and prevention of such interactions. Practical strategies, such as adjusting the timing of drug administration relative to meals, have been shown to reduce the likelihood of clinically significant interactions (1, 2).

The prevalence and clinical consequences of DFIs are well documented. For example, dietary fiber-rich foods have been shown to interfere with the absorption of levothyroxine, resulting in sub-therapeutic responses and poor disease control (3). Similarly, variations in the intake of omega-3 fatty acids can modify the pharmacological effects of warfarin, highlighting the importance of dietary consistency in patients receiving anticoagulant therapy (4). Such examples demonstrate the practical importance of DFI awareness for both healthcare providers and patients.

Globally, the integration of drug–food interaction (DFI) education into healthcare curricula has been recognized as a crucial step toward improving medication safety and therapeutic outcomes. Systematic reviews and comparative studies have indicated that structured DFI education, tailored to pharmacists, physicians, and other healthcare professionals, enhances clinical decision-making and patient counseling skills (5–8). Despite this, international analyses have revealed considerable variation in the inclusion and depth of DFI-related content across medical, pharmacy, and nursing programs (9, 10). Evidence also shows that healthcare providers frequently underestimate the impact of dietary components on drug efficacy and safety, highlighting the need for educational reform and continuing professional development in this area (11–13). Collectively, these findings underscore the global call for standardized DFI modules and practical training integrated into undergraduate curricula and CPD programs to equip healthcare professionals with the knowledge and counseling competencies necessary for optimal patient care (14–16).

Despite growing evidence, awareness of DFIs among healthcare professionals remains inconsistent across practice settings. Studies suggest that many practitioners possess limited knowledge of the clinical significance of DFIs or the mechanisms through which food components influence drug bioavailability (2, 17). Educational interventions targeting these knowledge gaps have proven effective in enhancing DFI-related competencies and improving medication safety outcomes. Therefore, incorporating DFI education into undergraduate curricula and continuing professional development programs is crucial to ensuring that healthcare professionals are well prepared to counsel patients appropriately (18).

Knowledge retention and practical application may be strengthened through the adoption of innovative educational strategies in healthcare training programs. Problem-based learning and case-based discussions can help students and professionals apply DFI concepts to real-world clinical scenarios. Additionally, simulation-based training and interactive digital modules have demonstrated effectiveness in improving comprehension and decision-making related to medication–food interactions (19, 20). Such approaches not only improve knowledge but also foster critical thinking and communication skills essential for patient counseling.

As the understanding of pharmacotherapy continues to evolve, the need to educate healthcare professionals about DFIs becomes increasingly urgent. A well-informed workforce can significantly reduce preventable medication errors, enhance therapeutic efficacy, and contribute to safer patient care practices. Strengthening DFI education within professional curricula and clinical training frameworks represents a vital step toward improving public health outcomes and advancing medication safety (21).

Therefore, this study aimed to assess the knowledge, counseling practices, and educational gaps related to drug–food interactions among healthcare professionals in Saudi Arabia. Specifically, it sought to evaluate healthcare providers’ understanding of common DFIs, identify demographic and professional predictors associated with knowledge levels, and explore the need for enhanced educational strategies to strengthen safe medication practices within the Saudi healthcare context.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

A cross-sectional study was conducted between October 2024 and January 2025 to assess the knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) of healthcare professionals (HCPs) in Saudi Arabia regarding drug–food interactions (DFIs). The study employed a structured, self-administered online questionnaire distributed across five major geographic regions: North, South, East, West, and Central Saudi Arabia.

Study population and sampling

The target population included licensed pharmacists, physicians, and nurses practicing in Saudi Arabia. Eligible participants were required to have at least 1 year of clinical experience and to provide informed consent prior to participation. Medical students, interns, unlicensed individuals, or those unwilling to participate were excluded.

Sample size calculation was performed using the Raosoft sample size calculator with a 95% confidence level, 5% margin of error, and an assumed response distribution of 50%, yielding a required sample of 385 respondents. A multistage stratified sampling technique was utilized. In the first stage, healthcare facilities were selected across the five geographic regions. In the second stage, participants were recruited using systematic random sampling from those facilities.

Instrument development and validation

The survey instrument was developed following an extensive literature review and expert panel consultation. It consisted of six sections: demographic data, self-assessment of DFI familiarity, knowledge of DFIs, knowledge of medication timing, attitudes toward DFIs, and DFI-related practices.

Content validity was assessed by a panel of clinical pharmacy and pharmacology experts. A pilot test involving 20 healthcare professionals was conducted to assess clarity and feasibility; data from the pilot were excluded from the final analysis. Internal consistency was acceptable, with Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.78 for knowledge, 0.72 for attitudes, and 0.82 for practices.

Data collection

The final survey was hosted on Microsoft Forms and distributed electronically via professional networks and social media platforms. Data were collected anonymously over a 3-month period (15 October 2024 to 15 January 2025). Participation was voluntary, and responses were de-identified prior to analysis.

Scoring of outcomes

Knowledge of DFIs was assessed using nine true/false/don’t know items, with one point awarded per correct answer (range: 0–9). Knowledge of medication timing was assessed using seven items (range: 0–7). Attitude scores were calculated from four statements using a 3-point Likert scale (disagree = 1, unsure = 2, agree = 3), with a total score range of 4–12. Practice scores were based on five items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (never = 1 to always = 5), producing a total score range of 5–25.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using R software (version 4.4.2) and RStudio (version 2024.9.1.394). Descriptive statistics included medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for non-normally distributed continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test.

Inferential analysis was conducted using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (for dichotomous variables) and the Kruskal–Wallis test (for variables with > 2 categories). Variables with a p-value < 0.05 in bivariate analysis were included in multivariable linear regression models to identify independent predictors of knowledge, attitude, and practice scores. Regression coefficients (β), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p-values were reported. All tests were two-sided, with a significance threshold set at p < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia (Approval No. HAPO-02-K-012-2025-01-2450). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations, and the study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained electronically from all participants prior to data submission. Data confidentiality and participant anonymity were maintained throughout the study.

Results

Demographic characteristics and self-perceptions on knowledge and practice of DFIs

A total of 385 participants were included in this cross-sectional study. Most respondents were aged between 30 and 39 years (46.8%), followed by those aged 22–29 years (37.1%). The sample consisted of 59.2% males and 40.8% females. Most participants were pharmacists (63.4%), followed by senior pharmacists (9.6%) and general practitioners (7.3%). The majority (88.6%) obtained their highest degree in Saudi Arabia. Regarding professional experience, 44.9% had more than 10 years of experience, while 29.1% had 1–5 years. The primary work settings were hospitals (40.9%) and pharmacies (40.4%). The southern region had the highest representation in the workplace (36.6%), followed by the western region (25.7%) and the central region (13.2%). Regarding familiarity with DFIs, 63.6% reported being somewhat familiar, and 31.2% indicated being very familiar. Most participants (68.3%) received formal training in DFIs during their undergraduate or graduate studies. DFIs were occasionally encountered by 54.8% of the respondents, and 64.9% reported being somewhat confident in identifying clinically significant DFIs (Table 1).

TABLE 1

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 22–29 years | 143 (37.1%) |

| 30–39 years | 180 (46.8%) |

| 40–49 years | 58 (15.1%) |

| 50–59 years | 3 (0.8%) |

| Above 60 years | 1 (0.3%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 228 (59.2%) |

| Female | 157 (40.8%) |

| Professional job | |

| Medical consultant | 6 (1.6%) |

| Medical specialist | 5 (1.3%) |

| General practitioner | 28 (7.3%) |

| Medical resident | 11 (2.9%) |

| Consultant pharmacist | 12 (3.1%) |

| Senior pharmacist | 37 (9.6%) |

| Pharmacist | 244 (63.4%) |

| Nurse | 24 (6.2%) |

| Others | 18 (4.7%) |

| Country of the highest degree | |

| From Saudi Arabia | 341 (88.6%) |

| Outside of Saudi Arabia | 44 (11.4%) |

| Years of experience in the current profession | |

| <1 year | 42 (10.9%) |

| 1–5 Years | 112 (29.1%) |

| 6–10 Years | 58 (15.1%) |

| More than 10 years | 173 (44.9%) |

| Primary place of work* | |

| Hospital | 157 (40.9%) |

| Clinic | 11 (2.9%) |

| Hospital pharmacy | 155 (40.4%) |

| Community pharmacy | 45 (11.7%) |

| Others | 16 (4.2%) |

| Region of the workplace | |

| Northern region | 49 (12.7%) |

| Southern region | 141 (36.6%) |

| Eastern region | 45 (11.7%) |

| Western region | 99 (25.7%) |

| Central region | 51 (13.2%) |

| Familiarity with drug-food interactions | |

| Very familiar | 120 (31.2%) |

| Somewhat familiar | 245 (63.6%) |

| Not familiar | 20 (5.2%) |

| Ever received formal training on drug-food interactions | |

| No | 93 (24.2%) |

| Yes, during undergraduate/graduate studies | 263 (68.3%) |

| Yes, through professional development programs | 29 (7.5%) |

| Frequency of encountering drug-food interactions in practice | |

| Never | 25 (6.5%) |

| Rarely | 104 (27.0%) |

| Occasionally | 211 (54.8%) |

| Frequently | 45 (11.7%) |

| Confidence in identifying clinically significant drug-food interactions | |

| Not confident | 34 (8.8%) |

| Somewhat confident | 250 (64.9%) |

| Very confident | 101 (26.2%) |

Demographic characteristics and self-perceptions on knowledge and practice of drug-food interactions.

n (%); *The variable had one missing record.

Description of the scores of different domains

Participants had a median score of 6.0 out of 9.0 (IQR = 4.0–8.0) for knowledge regarding DFIs. For knowledge of the best timing of drug intake, the median score was 5.0 out of 7.0 (IQR = 4.0–6.0). Details of the knowledge scores are summarized in Table 2. Attitudes toward DFIs had a median score of 10.0 out of 12.0 (IQR = 10.0–12.0). The median score for practices related to DFIs was 17.0 out of 25.0 (IQR = 14.0–20.0).

TABLE 2

| Characteristic | Median (Q1–Q3) | Mean ± SD | Min-Max | N of items |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge regarding drug-food interactions | 6.0 (4.0–8.0) | 5.6 ± 2.4 | 0.0–9.0 | 9 |

| Knowledge regarding the best timing of drug intake | 5.0 (4.0–6.0) | 4.6 ± 1.6 | 0.0–7.0 | 7 |

| Attitudes toward drug-food interactions | 10.0 (10.0–12.0) | 10.4 ± 1.4 | 5.0–12.0 | 4 |

| Practice of drug-food interactions | 17.0 (14.0–20.0) | 16.7 ± 4.4 | 5.0–25.0 | 5 |

Description of the scores of different domains.

SD, standard deviation.

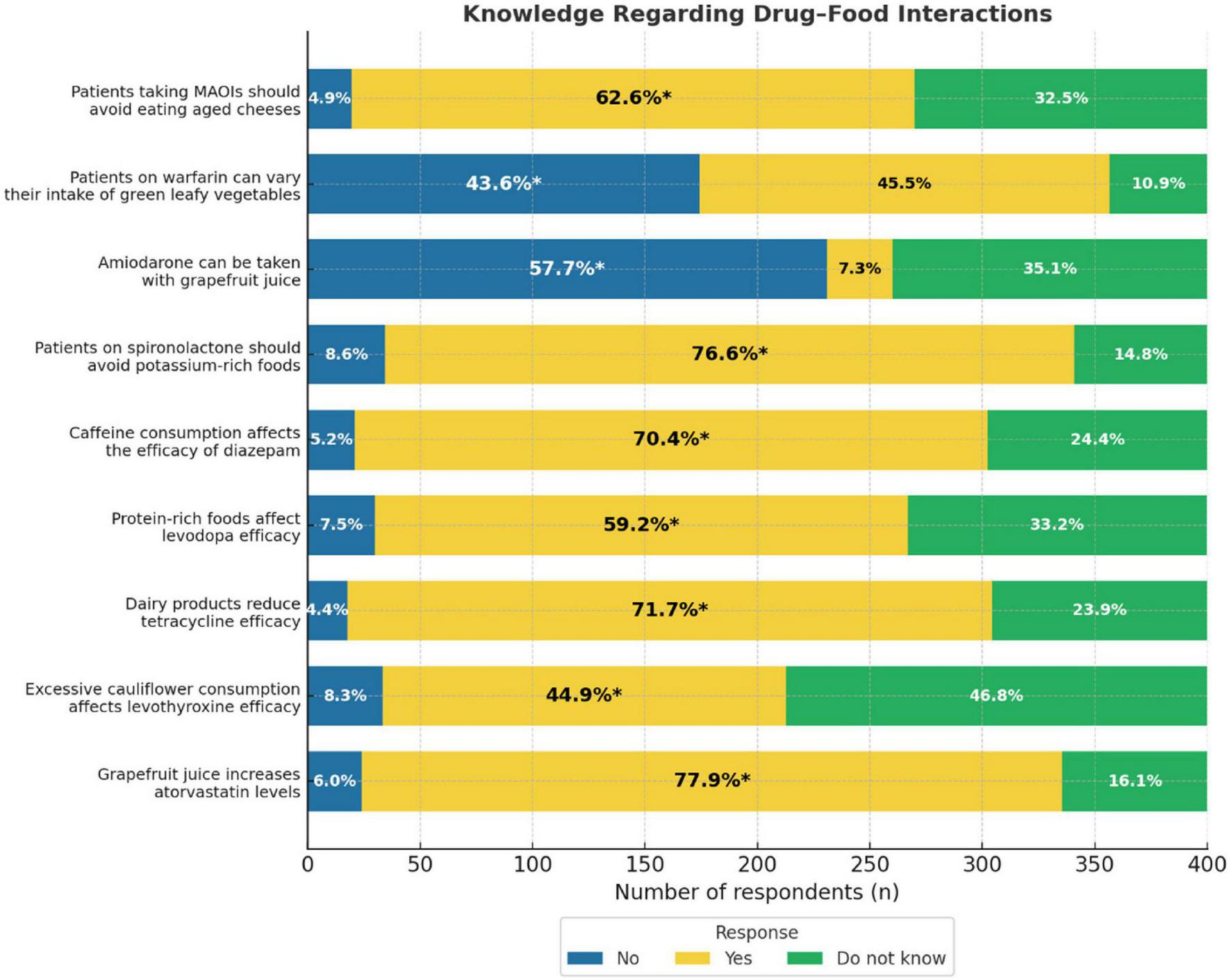

Knowledge regarding DFIs

Several key DFIs were correctly identified by the majority of participants. Specifically, 77.9% correctly reported that grapefruit juice increased atorvastatin levels, and 76.6% recognized that patients on spironolactone should avoid potassium-rich foods. Furthermore, 71.7% were aware that dairy products can reduce the efficacy of tetracyclines, and 70.4% acknowledged that caffeine can affect the effectiveness of diazepam. Correct responses were also recorded for interactions involving protein-rich foods and levodopa (59.2%) and MAOIs with aged cheeses (62.6%). However, only 44.9% correctly identified that excessive consumption of cauliflower affected the efficacy of levothyroxine. Notably, 57.7% of the participants correctly stated that amiodarone should not be taken with grapefruit juice, and 43.6% correctly indicated that patients on warfarin should not freely vary their intake of green leafy vegetables (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

Knowledge regarding drug-food interactions bar graph. It represents the percentage of respondents’ awareness of drug-food interactions for MAOIs, warfarin, amiodarone, spironolactone, diazepam, levodopa, tetracycline, levothyroxine, and atorvastatin. Three response categories: No, Yes, Do not know. Percentages inside each bar indicate the proportion of respondents selecting each option, with an asterisk (*) marking the correct answer.

Factors and predictors of high scores of general knowledge regarding DFIs

Compared with medical consultants, nurses had significantly lower general knowledge scores (β = −2.09, 95% CI = −4.04 to −0.15, p = 0.036). Participants working in clinics scored significantly lower than those working in hospitals (β = −2.27, 95% CI = −3.63, −0.91, p = 0.001). Participants who reported being “somewhat familiar” (β = −0.94, 95% CI, −1.51 to −0.37, p = 0.001) or “not familiar” (β = −2.04, 95% CI, −3.26 to −0.82, p = 0.001) with DFIs had lower knowledge scores than those who were “very familiar.” Those who received DFI training during undergraduate or graduate studies had higher scores than those who did not (β = 0.68, 95% CI, 0.11–1.25, p = 0.019). Compared to participants who never encountered DFIs in practice, those who rarely (β = 1.18, 95% CI, 0.20–2.16, p = 0.019) and occasionally (β = 0.99, 95% CI, 0.03–1.96, p = 0.044) encountered them had significantly higher knowledge scores (Table 3).

TABLE 3

| Variable | Inferential analysis | Multivariable regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | P-value | Beta | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age | 0.003 | ||||

| 22–29 years | 7.0 (5.0, 8.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| 30–39 years | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | –0.45 | –0.98, 0.08 | 0.096 | |

| 40–49 years | 5.0 (3.0, 7.0) | –0.30 | –1.02, 0.43 | 0.424 | |

| 50 years or more | 5.0 (3.0, 7.5) | 0.46 | –1.63, 2.54 | 0.669 | |

| Gender | 0.001 | ||||

| Male | 6.0 (3.0, 7.5) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 6.0 (5.0, 8.0) | 0.36 | –0.12, 0.85 | 0.139 | |

| Professional job | < 0.001 | ||||

| Medical consultant | 6.0 (5.0, 8.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Medical specialist | 4.0 (4.0, 6.0) | –0.32 | –2.83, 2.18 | 0.800 | |

| General practitioner | 5.5 (2.5, 8.0) | –0.66 | –2.60, 1.28 | 0.505 | |

| Medical resident | 8.0 (2.0, 8.0) | –1.09 | –3.23, 1.05 | 0.319 | |

| Consultant pharmacist | 7.0 (6.0, 8.0) | 0.32 | –1.81, 2.45 | 0.770 | |

| Senior pharmacist | 7.0 (6.0, 8.0) | 0.65 | –1.27, 2.57 | 0.506 | |

| Pharmacist | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | –0.19 | –2.03, 1.66 | 0.844 | |

| Nurse | 3.0 (1.0, 5.0) | –2.09 | –4.04, –0.15 | 0.036 | |

| Others | 4.5 (4.0, 6.0) | –0.79 | –2.84, 1.26 | 0.451 | |

| Country of the highest degree | 0.934 | ||||

| From Saudi Arabia | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | ||||

| Outside of Saudi Arabia | 6.5 (4.0, 7.5) | ||||

| Years of experience in the current profession | 0.069 | ||||

| <1 year | 7.0 (6.0, 8.0) | ||||

| 1–5 years | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | ||||

| 6–10 years | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | ||||

| More than 10 years | 6.0 (3.0, 8.0) | ||||

| Primary place of work | < 0.001 | ||||

| Hospital | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Clinic | 2.0 (0.0, 5.0) | –2.27 | –3.63, –0.91 | 0.001 | |

| Hospital pharmacy | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | –0.19 | –0.74, 0.36 | 0.498 | |

| Community pharmacy | 7.0 (6.0, 8.0) | 0.82 | –0.01, 1.64 | 0.053 | |

| Others | 5.5 (3.0, 6.0) | –1.06 | –2.16, 0.04 | 0.061 | |

| Region of the workplace | 0.002 | ||||

| Northern region | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Southern region | 5.0 (3.0, 7.0) | –0.16 | –0.86, 0.55 | 0.661 | |

| Eastern region | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | 0.04 | –0.82, 0.90 | 0.929 | |

| Western region | 6.0 (5.0, 8.0) | 0.20 | –0.54, 0.95 | 0.589 | |

| Central region | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | –0.15 | –0.98, 0.68 | 0.720 | |

| Familiarity with drug-food interactions | < 0.001 | ||||

| Very familiar | 8.0 (6.0, 8.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Somewhat familiar | 6.0 (4.0, 7.0) | –0.94 | –1.51, –0.37 | 0.001 | |

| Not familiar | 2.0 (1.0, 5.0) | –2.04 | –3.26, –0.82 | 0.001 | |

| Ever received formal training on drug-food interactions | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 5.0 (2.0, 7.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes, during undergraduate/graduate studies | 7.0 (5.0, 8.0) | 0.68 | 0.11, 1.25 | 0.019 | |

| Yes, through professional development programs | 5.0 (3.0, 7.0) | 0.33 | –0.62, 1.29 | 0.494 | |

| Frequency of encountering drug-food interactions in practice | < 0.001 | ||||

| Never | 4.0 (0.0, 6.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Rarely | 6.0 (4.0, 7.5) | 1.18 | 0.20, 2.16 | 0.019 | |

| Occasionally | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | 0.99 | 0.03, 1.96 | 0.044 | |

| Frequently | 7.0 (5.0, 8.0) | 0.98 | –0.14, 2.09 | 0.086 | |

| Confidence in identifying clinically significant drug-food interactions | < 0.001 | ||||

| Not confident | 5.0 (2.0, 6.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Somewhat confident | 6.0 (4.0, 7.0) | 0.03 | –0.82, 0.89 | 0.939 | |

| Very confident | 8.0 (6.0, 8.0) | 0.99 | –0.02, 2.00 | 0.056 | |

Factors and predictors of high general knowledge scores regarding drug-food interactions.

IQR, interquartile range. Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test; Wilcoxon rank sum test. CI, Confidence Interval.

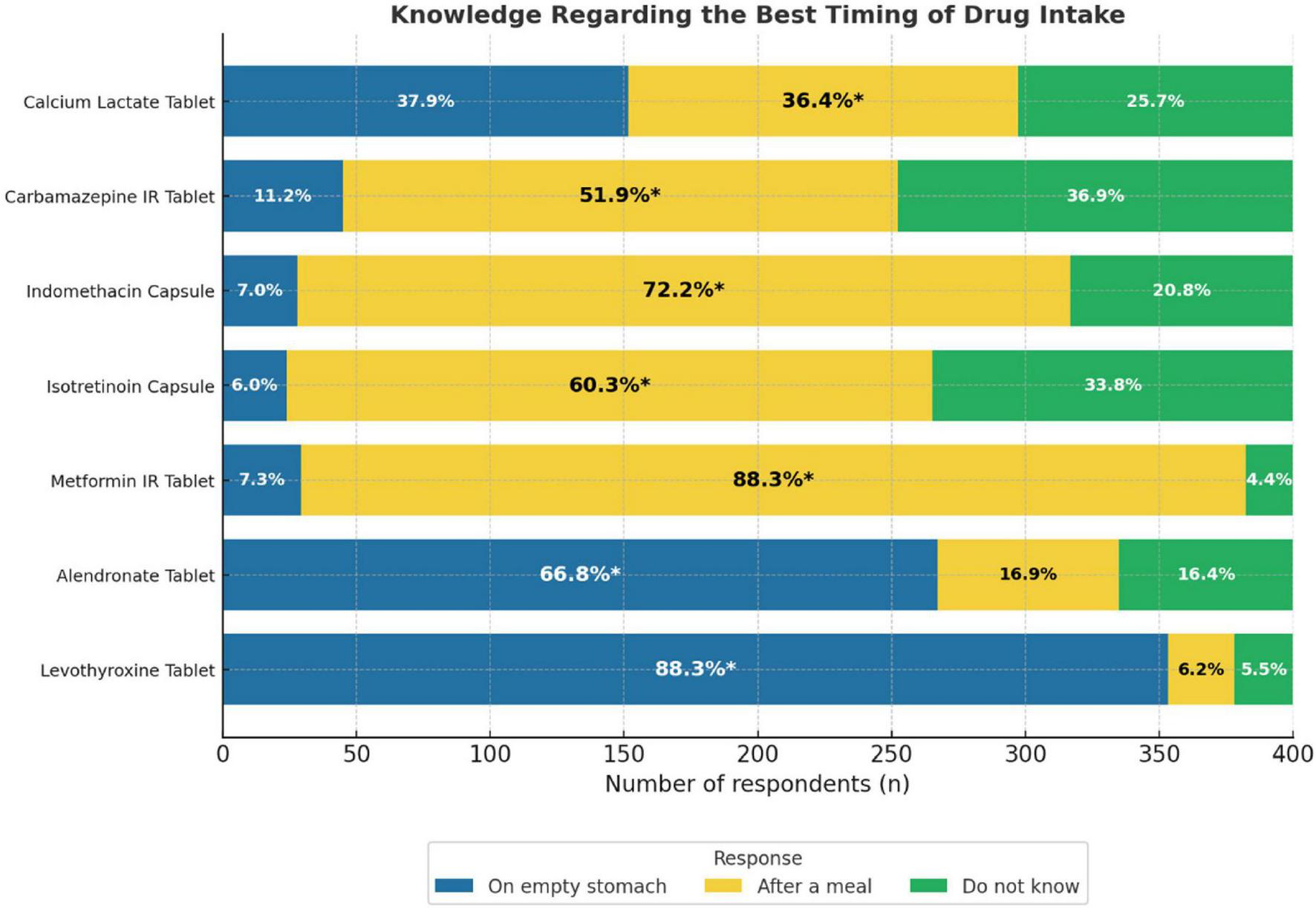

Knowledge regarding the best timing of drug intake

Most participants demonstrated a good knowledge of the appropriate timing of drug administration. The correct timing was most frequently identified for levothyroxine tablets and metformin Immediate Release (IR) tablets, with 88.3% of respondents selecting “on an empty stomach” and “after a meal,” respectively. Similarly, 72.2% correctly indicated that indomethacin capsules should be taken after a meal, and 66.8% identified that the correct timing for alendronate tablets was on an empty stomach. The correct responses were lower for isotretinoin capsules (60.3%) and carbamazepine IR tablets (51.9%). For calcium lactate, 36.4% correctly selected “after a meal,” while 37.9% incorrectly selected “on an empty stomach” (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2

Knowledge regarding the best timing of drug bar graph. It is showing the responses for seven drugs: Calcium Lactate, Carbamazepine IR, Indomethacin, Isotretinoin, Metformin IR, Alendronate, and Levothyroxine Tablets. Responses are divided into three categories: “On empty stomach,” “After a meal,” and “Do not know.” Percentages inside each bar indicate the proportion of respondents selecting each option, with an asterisk (*) marking the correct answer.

Factors and predictors of high knowledge scores regarding the best timing of drug intake

Significantly higher knowledge scores regarding the best timing of drug intake were observed among female participants compared with males (β = 0.37, 95% CI, 0.03–0.71, p = 0.032). Compared to those working in hospitals, participants working in hospital pharmacies had slightly lower scores (β = −0.41, 95% CI, −0.82 to 0.00, p = 0.049). Additionally, participants who reported not being familiar with DFIs had significantly lower scores than those who were very familiar (β = −1.20, 95% CI, −2.12 to −0.28, p = 0.011) (Table 4).

TABLE 4

| Variable | Inferential analysis | Multivariable regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | P-value | Beta | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age | 0.371 | ||||

| 22–29 years | 5.0 (3.0, 6.0) | ||||

| 30–39 years | 5.0 (4.0, 6.0) | ||||

| 40–49 years | 5.0 (3.0, 6.0) | ||||

| 50 years or more | 3.5 (3.0, 5.0) | ||||

| Gender | 0.007 | ||||

| Male | 5.0 (3.0, 6.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 5.0 (4.0, 6.0) | 0.37 | 0.03, 0.71 | 0.032 | |

| Professional job | 0.011 | ||||

| Medical consultant | 4.5 (4.0, 6.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Medical specialist | 4.0 (4.0, 6.0) | 0.67 | –1.22, 2.56 | 0.485 | |

| General practitioner | 5.0 (3.0, 6.0) | –0.03 | –1.49, 1.44 | 0.973 | |

| Medical resident | 6.0 (4.0, 6.0) | 0.37 | –1.25, 1.98 | 0.658 | |

| Consultant pharmacist | 5.5 (2.5, 6.0) | –0.12 | –1.74, 1.50 | 0.883 | |

| Senior pharmacist | 5.0 (4.0, 6.0) | 0.82 | –0.63, 2.27 | 0.269 | |

| Pharmacist | 5.0 (4.0, 6.0) | 0.69 | –0.70, 2.07 | 0.332 | |

| Nurse | 4.0 (2.0, 5.0) | –0.70 | –2.16, 0.77 | 0.352 | |

| Others | 3.0 (3.0, 5.0) | –0.12 | –1.67, 1.42 | 0.874 | |

| Country of the highest degree | 0.052 | ||||

| From Saudi Arabia | 5.0 (4.0, 6.0) | ||||

| Outside of Saudi Arabia | 4.0 (3.0, 6.0) | ||||

| Years of experience in the current profession | 0.139 | ||||

| < 1 year | 5.0 (3.0, 6.0) | ||||

| 1–5 years | 5.0 (3.0, 6.0) | ||||

| 6–10 years | 5.0 (4.0, 6.0) | ||||

| More than 10 years | 5.0 (4.0, 6.0) | ||||

| Primary place of work | 0.024 | ||||

| Hospital | 5.0 (4.0, 6.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Clinic | 4.0 (2.0, 5.0) | –0.80 | –1.83, 0.22 | 0.126 | |

| Hospital pharmacy | 5.0 (4.0, 6.0) | –0.41 | –0.82, 0.00 | 0.049 | |

| Community pharmacy | 5.0 (4.0, 6.0) | –0.04 | –0.61, 0.53 | 0.893 | |

| Others | 4.0 (3.0, 5.0) | –0.83 | –1.66, 0.00 | 0.051 | |

| Region of the workplace | 0.234 | ||||

| Northern region | 6.0 (4.0, 6.0) | ||||

| Southern region | 4.0 (3.0, 6.0) | ||||

| Eastern region | 5.0 (4.0, 6.0) | ||||

| Western region | 5.0 (3.0, 6.0) | ||||

| Central region | 5.0 (4.0, 6.0) | ||||

| Familiarity with drug-food interactions | < 0.001 | ||||

| Very familiar | 6.0 (5.0, 6.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Somewhat familiar | 4.0 (3.0, 6.0) | –0.31 | –0.74, 0.11 | 0.149 | |

| Not familiar | 3.0 (1.5, 5.0) | –1.20 | –2.12, –0.28 | 0.011 | |

| Ever received formal training on drug-food interactions | 0.015 | ||||

| No | 4.0 (3.0, 6.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes, during undergraduate/graduate studies | 5.0 (4.0, 6.0) | 0.18 | –0.24, 0.61 | 0.402 | |

| Yes, through professional development programs | 4.0 (3.0, 6.0) | 0.03 | –0.69, 0.75 | 0.936 | |

| Frequency of encountering drug-food interactions in practice | < 0.001 | ||||

| Never | 4.0 (2.0, 5.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Rarely | 4.0 (3.0, 6.0) | 0.44 | –0.30, 1.18 | 0.248 | |

| Occasionally | 5.0 (4.0, 6.0) | 0.73 | 0.00, 1.46 | 0.052 | |

| Frequently | 5.0 (4.0, 6.0) | 0.39 | –0.45, 1.24 | 0.360 | |

| Confidence in identifying clinically significant drug-food interactions | < 0.001 | ||||

| Not confident | 4.0 (3.0, 5.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Somewhat confident | 5.0 (3.0, 6.0) | –0.08 | –0.72, 0.57 | 0.820 | |

| Very confident | 6.0 (4.0, 6.0) | 0.42 | –0.34, 1.18 | 0.281 | |

Factors and predictors of high knowledge scores regarding the best timing of drug intake.

IQR, interquartile range; CI, Confidence Interval.Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test; Wilcoxon rank sum test.

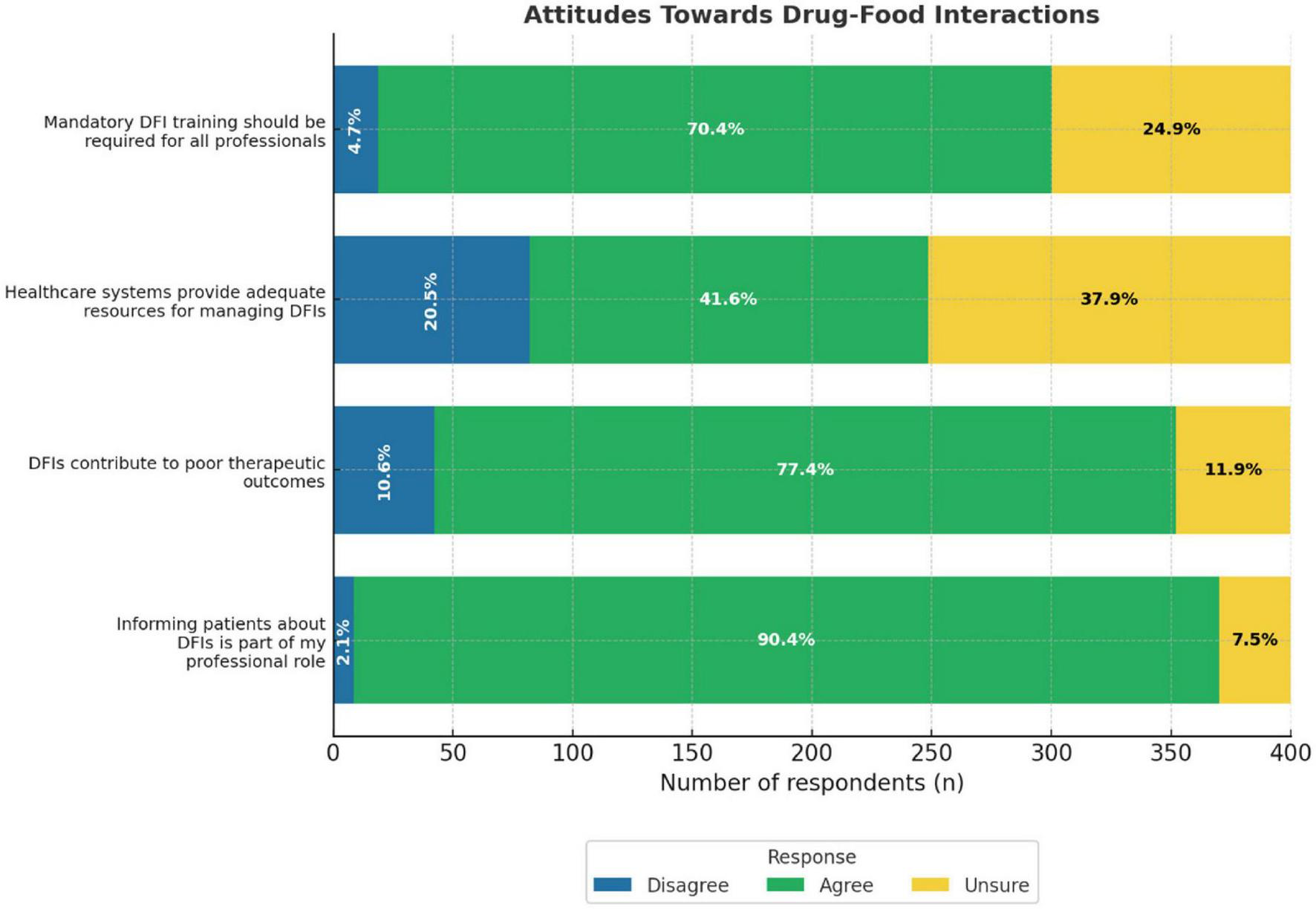

Attitudes toward DFIs

The majority of participants demonstrated positive attitudes toward DFIs. Most notably, 90.4% agreed that informing patients about DFIs was part of their professional role. Similarly, 77.4% of patients agreed that DFIs contributed to poor therapeutic outcomes. Additionally, 70.4% of the participants supported the notion that mandatory training on DFIs is necessary for all HCPs. By contrast, only 41.6% agreed that the healthcare system provides adequate resources for managing DFIs, indicating a perceived gap in institutional support (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3

Attitudes towards drug-food interactions bar chart. It shows the responses from healthcare professionals who disagreed, were unsure, or agreed with each statement. The statments include mandatory DFI training, healthcare resources, DFI impact on outcomes, and informing patients.

Factors and predictors of high scores of attitudes toward DFIs

Female participants had significantly more positive attitudes toward DFIs than male participants (β = 0.35, 95% CI = 0.06–0.64, p = 0.017). Compared to those who were very familiar with DFIs, somewhat familiar participants had lower attitude scores (β = −0.50, 95% CI = −0.84 to −0.15, p = 0.005). Participants who rarely (beta = 0.88, 95% CI, 0.28–1.48, p = 0.004), occasionally (β = 1.34, 95% CI, 0.75–1.93, p < 0.001), or frequently (β = 1.04, 95% CI, 0.35–1.73, p = 0.003) encountered DFIs in practice had significantly higher attitude scores than those who never experienced them (Table 5).

TABLE 5

| Variable | Inferential analysis | Multivariable regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | P-value | Beta | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age | 0.005 | ||||

| 22–29 years | 11.0 (10.0, 12.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| 30–39 years | 11.0 (10.0, 12.0) | 0.08 | –0.22, 0.38 | 0.609 | |

| 40–49 years | 10.0 (10.0, 10.0) | –0.41 | –0.83, 0.01 | 0.055 | |

| 50 years or more | 10.0 (10.0, 11.0) | –0.10 | –1.38, 1.19 | 0.884 | |

| Gender | < 0.001 | ||||

| Male | 10.0 (10.0, 11.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 11.0 (10.0, 12.0) | 0.35 | 0.06, 0.64 | 0.017 | |

| Professional job | 0.372 | ||||

| Medical consultant | 11.0 (10.0, 12.0) | ||||

| Medical specialist | 11.0 (10.0, 11.0) | ||||

| General practitioner | 11.0 (10.5, 12.0) | ||||

| Medical resident | 11.0 (10.0, 12.0) | ||||

| Consultant pharmacist | 11.5 (10.0, 12.0) | ||||

| Senior pharmacist | 11.0 (10.0, 11.0) | ||||

| Pharmacist | 10.0 (10.0, 12.0) | ||||

| Nurse | 10.0 (10.0, 11.0) | ||||

| Others | 11.0 (9.0, 12.0) | ||||

| Country of the highest degree | 0.573 | ||||

| From Saudi Arabia | 10.0 (10.0, 12.0) | ||||

| Outside of Saudi Arabia | 10.0 (10.0, 11.0) | ||||

| Years of experience in the current profession | 0.484 | ||||

| <1 year | 10.0 (9.0, 11.0) | ||||

| 1–5 years | 10.0 (10.0, 12.0) | ||||

| 6–10 years | 10.5 (10.0, 12.0) | ||||

| More than 10 years | 10.0 (10.0, 12.0) | ||||

| Primary place of work | 0.295 | ||||

| Hospital | 11.0 (10.0, 12.0) | ||||

| Clinic | 10.0 (8.0, 11.0) | ||||

| Hospital pharmacy | 10.0 (10.0, 12.0) | ||||

| Community pharmacy | 11.0 (10.0, 12.0) | ||||

| 10.0 (8.0, 11.0) | |||||

| Region of the workplace | 0.063 | ||||

| Northern region | 10.0 (10.0, 12.0) | ||||

| Southern region | 10.0 (10.0, 12.0) | ||||

| Eastern region | 11.0 (10.0, 12.0) | ||||

| Western region | 11.0 (10.0, 11.0) | ||||

| Central region | 10.0 (10.0, 12.0) | ||||

| Familiarity with drug-food interactions | < 0.001 | ||||

| Very familiar | 11.0 (10.0, 12.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Somewhat familiar | 10.0 (10.0, 11.0) | –0.50 | –0.84, –0.15 | 0.005 | |

| Not familiar | 9.0 (8.0, 12.0) | –0.71 | –1.44, 0.02 | 0.059 | |

| Ever received formal training on drug-food interactions | 0.007 | ||||

| No | 10.0 (8.0, 11.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes, during undergraduate/graduate studies | 11.0 (10.0, 12.0) | 0.11 | –0.24, 0.46 | 0.532 | |

| Yes, through professional development programs | 11.0 (10.0, 12.0) | 0.01 | –0.55, 0.56 | 0.981 | |

| Frequency of encountering drug-food interactions in practice | < 0.001 | ||||

| Never | 9.0 (8.0, 10.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Rarely | 10.0 (9.0, 11.0) | 0.88 | 0.28, 1.48 | 0.004 | |

| Occasionally | 11.0 (10.0, 12.0) | 1.34 | 0.75, 1.93 | < 0.001 | |

| Frequently | 10.0 (10.0, 12.0) | 1.04 | 0.35, 1.73 | 0.003 | |

| Confidence in identifying clinically significant drug-food interactions | 0.010 | ||||

| Not confident | 10.0 (8.0, 11.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Somewhat confident | 10.0 (10.0, 12.0) | 0.01 | –0.52, 0.54 | 0.981 | |

| Very confident | 11.0 (10.0, 12.0) | –0.22 | –0.85, 0.41 | 0.489 | |

Factors and predictors of high scores of attitudes toward drug-food interactions.

IQR, interquartile range; CI, Confidence Interval. Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test; Wilcoxon rank sum test.

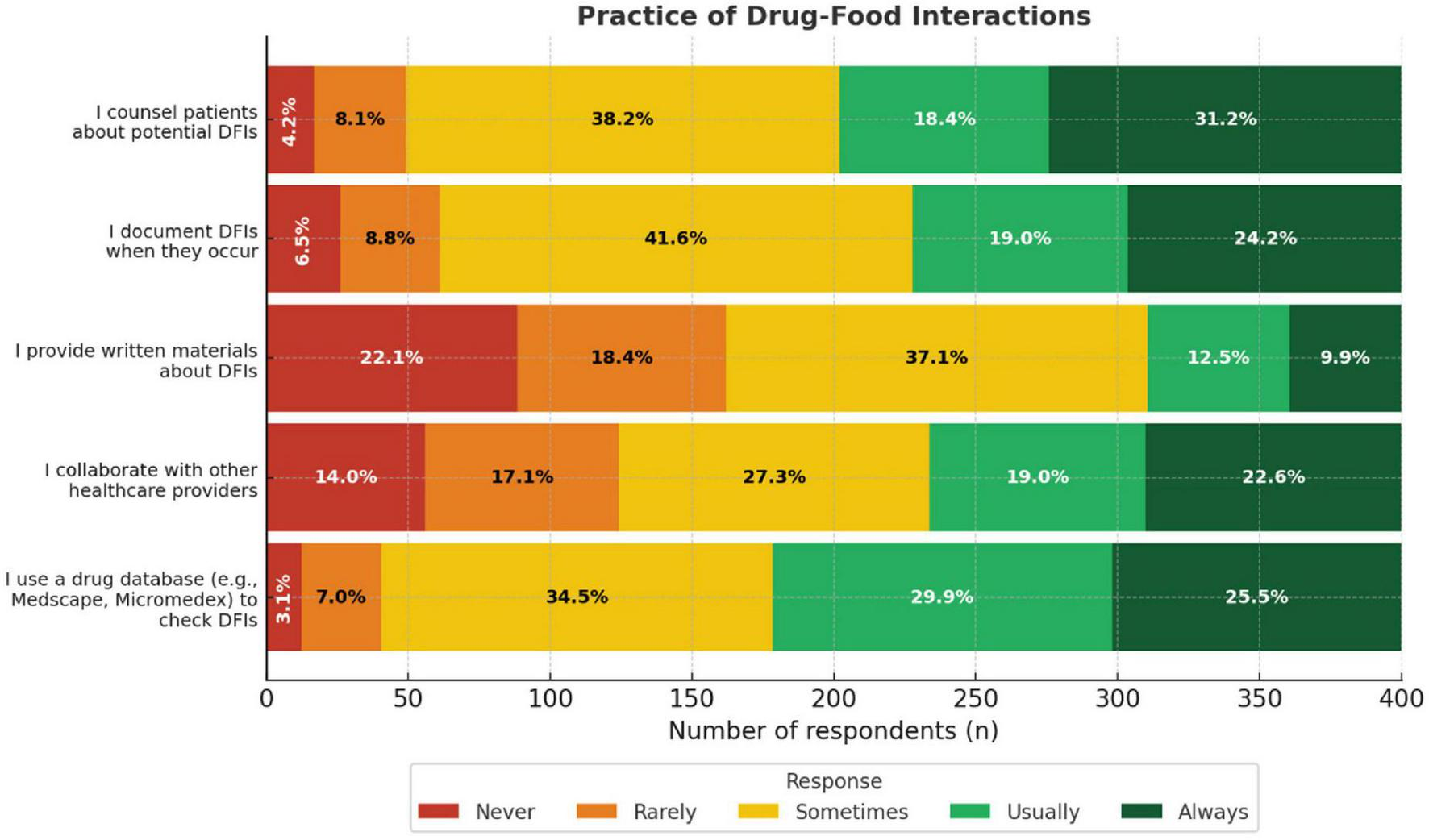

Practice of DFIs

A total of 55.4% of the participants reported that they usually or always counsel patients about potential DFIs. Similarly, 41.6% indicated that they usually or always documented DFIs when they occurred. Drug databases were commonly used to check for interactions, with 49.6% reporting frequent use. Collaboration with other HCPs on DFI management was reported by 43.2% of participants, while only 22.4% reported that they usually or always provided written materials about DFIs to patients (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4

Practice of drug-food interactions encounters among healthcare providers bar chart. It shows the percentage of respondents who answered “Never,” “Rarely,” “Sometimes,” “Usually,” or “Always” for each practice Categories include using a drug database, collaborating with healthcare providers, providing written materials, documenting, and counseling patients about potential interactions.

Factors and predictors of high scores of practices of DFIs

Compared to medical consultants, higher practice scores were observed among medical specialists (β = 5.09, 95% CI, 0.21–9.96, p = 0.042), general practitioners (β = 4.27, 95% CI, 0.46–8.08, p = 0.029), medical residents (β = 5.43, 95% CI, 1.20–9.66, p = 0.012), consultant pharmacists (β = 6.96, 95% CI, 2.73–11.2, p = 0.001), senior pharmacists (β = 5.40, 95% CI, 1.65–9.16, p = 0.005), pharmacists (β = 7.35, 95% CI, 3.77–10.9, p < 0.001), nurses (β = 5.48, 95% CI, 1.61–9.35, p = 0.006), and those classified as “others” (β = 5.59, 95% CI, 1.56–9.62, p = 0.007). Participants who were somewhat familiar with DFIs had lower scores than those who were very familiar (β = −2.33, 95% CI, −3.45 to −1.22, p < 0.001). Compared to those who never encountered DFIs, higher practice scores were reported by participants who rarely (β = 2.51, 95% CI, 0.58–4.44, p = 0.011), occasionally (β = 2.73, 95% CI, 0.83– 4.62, p = 0.005), and frequently (β = 3.09, 95% CI, 0.89–5.30, p = 0.006) encountered them. Those who reported being somewhat confident (β = 2.12, 95% CI, 0.42–3.82, p = 0.015) or very confident (β = 2.71, 95% CI, 0.73–4.68, p = 0.008) in identifying clinically significant DFIs also had significantly higher practice scores than those who were not confident (Table 6).

TABLE 6

| Variable | Inferential analysis | Multivariable regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | P-value | Beta | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Age | 0.605 | ||||

| 22–29 years | 17.0 (14.0, 20.0) | ||||

| 30–39 years | 17.0 (14.0, 20.0) | ||||

| 40–49 years | 16.0 (13.0, 19.0) | ||||

| 50 years or more | 14.5 (13.5, 18.5) | ||||

| Gender | 0.811 | ||||

| Male | 17.0 (14.0, 20.0) | ||||

| Female | 17.0 (14.0, 19.0) | ||||

| Professional job | < 0.001 | ||||

| Medical consultant | 11.5 (10.0, 12.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Medical specialist | 11.0 (10.0, 22.0) | 5.09 | 0.21, 9.96 | 0.042 | |

| General practitioner | 15.0 (13.0, 18.0) | 4.27 | 0.46, 8.08 | 0.029 | |

| Medical resident | 15.0 (14.0, 19.0) | 5.43 | 1.20, 9.66 | 0.012 | |

| Consultant pharmacist | 17.0 (16.0, 22.0) | 6.96 | 2.73, 11.2 | 0.001 | |

| Senior pharmacist | 17.0 (14.0, 20.0) | 5.40 | 1.65, 9.16 | 0.005 | |

| Pharmacist | 17.0 (15.0, 20.0) | 7.35 | 3.77, 10.9 | < 0.001 | |

| Nurse | 14.5 (12.5, 17.0) | 5.48 | 1.61, 9.35 | 0.006 | |

| Others | 15.5 (13.0, 17.0) | 5.59 | 1.56, 9.62 | 0.007 | |

| Country of the highest degree | 0.452 | ||||

| From Saudi Arabia | 16.0 (14.0, 20.0) | ||||

| Outside of Saudi Arabia | 17.0 (14.5, 20.0) | ||||

| Years of experience in the current profession | 0.961 | ||||

| < 1 Year | 17.0 (13.0, 20.0) | ||||

| 1–5 Years | 16.5 (14.0, 19.5) | ||||

| 6–10 Years | 16.0 (14.0, 20.0) | ||||

| More than 10 years | 16.0 (14.0, 20.0) | ||||

| Primary place of work | 0.168 | ||||

| Hospital | 16.0 (13.0, 19.0) | ||||

| Clinic | 17.0 (14.0, 22.0) | ||||

| Hospital pharmacy | 17.0 (15.0, 19.0) | ||||

| Community pharmacy | 17.0 (15.0, 20.0) | ||||

| Others | 14.0 (9.5, 19.5) | ||||

| Region of the workplace | 0.109 | ||||

| Northern region | 17.0 (15.0, 19.0) | ||||

| Southern region | 16.0 (13.0, 20.0) | ||||

| Eastern region | 18.0 (15.0, 21.0) | ||||

| Western region | 17.0 (14.0, 20.0) | ||||

| Central region | 15.0 (13.0, 18.0) | ||||

| Familiarity with drug-food interactions | < 0.001 | ||||

| Very familiar | 19.0 (16.0, 22.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Somewhat familiar | 15.0 (13.0, 19.0) | –2.33 | –3.45, –1.22 | < 0.001 | |

| Not familiar | 15.5 (10.0, 20.0) | –1.04 | –3.41, 1.32 | 0.388 | |

| Ever received formal training on drug-food interactions | 0.010 | ||||

| No | 16.0 (12.0, 18.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes, during undergraduate/graduate studies | 17.0 (15.0, 20.0) | 0.42 | –0.68, 1.53 | 0.454 | |

| Yes, through professional development programs | 16.0 (12.0, 19.0) | 0.87 | –1.02, 2.75 | 0.367 | |

| Frequency of encountering drug-food interactions in practice | < 0.001 | ||||

| Never | 13.0 (10.0, 16.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Rarely | 16.0 (12.0, 20.0) | 2.51 | 0.58, 4.44 | 0.011 | |

| Occasionally | 17.0 (15.0, 19.0) | 2.73 | 0.83, 4.62 | 0.005 | |

| Frequently | 18.0 (15.0, 21.0) | 3.09 | 0.89, 5.30 | 0.006 | |

| Confidence in identifying clinically significant drug-food interactions | < 0.001 | ||||

| Not confident | 14.5 (9.0, 17.0) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Somewhat confident | 16.0 (14.0, 20.0) | 2.12 | 0.42, 3.82 | 0.015 | |

| Very confident | 18.0 (15.0, 21.0) | 2.71 | 0.73, 4.68 | 0.008 | |

Factors and predictors of high scores of practice of drug-food interactions.

IQR: interquartile range; CI, Confidence Interval. Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test; Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Discussion

Substantial deficiencies in healthcare professionals’ knowledge and practices concerning drug–food interactions were revealed (DFIs), particularly within the context of pharmacy practice in Saudi Arabia. Among the 385 participants, 231 (60.0%) demonstrated limited awareness of DFI mechanisms. This indicates a broader shortfall in education and training, possibly due to limited curricular coverage of DFIs and insufficient continuing professional development opportunities. Comparable deficits have been reported regionally, as community pharmacists in Palestine struggled to identify common DFIs despite recognizing their clinical relevance, and similar limitations were observed among healthcare workers in Ethiopia (22, 23). Collectively, these patterns reflect a systemic educational challenge across the Middle East and Africa that warrants comprehensive reform.

The lack of structured education emerges as a plausible explanation for these knowledge gaps. In this study, 198 participants (51.4%) reported never receiving formal instruction on DFIs, while 146 (37.9%) indicated that their knowledge was primarily acquired informally. These results align with international evidence highlighting insufficient curricular integration of DFI topics within pharmacy education (24, 25). Similar concerns have been raised in Malaysia and Poland, where inadequate DFI instruction contributes to knowledge gaps and medication errors (26, 27). The importance of embedding DFI content into pharmacy curricula to enhance awareness and practical counseling skills is underscored by these educational deficiencies.

Counseling practices also appear to be influenced by educational background. Only 164 respondents (42.6%) reported routinely discussing DFIs related to traditional foods or herbal remedies with patients. This pattern mirrors international findings showing that, while pharmacists generally recognize their responsibility to counsel patients, many lack sufficient confidence or depth of knowledge to provide culturally sensitive advice (28, 29). Moreover, reliance on unverified online resources for DFI information—reported in other community pharmacy studies—raises concerns about the accuracy and safety of patient counseling (30, 31). These findings highlight the need for structured, evidence-based counseling frameworks that integrate both clinical and cultural knowledge.

Underreporting of DFI-related adverse events represents another critical issue. In this study, only 73 participants (19.0%) had ever submitted a pharmacovigilance report. This aligns with previous research documenting low levels of reporting among Saudi healthcare professionals, often linked to limited awareness of reporting systems and uncertainty regarding procedures (32, 33). Regionally, Alshammari et al. and Garashi et al. noted that underdeveloped pharmacovigilance infrastructure and training deficiencies remain major barriers, while Alzubiedi et al. reported that the COVID-19 pandemic further disrupted reporting processes (34–36). Addressing these gaps through education, standardized reporting protocols, and integration of DFI-specific examples in training programs could improve the safety surveillance system and reporting culture.

Building on these findings, pharmacy curricula in Saudi Arabia may not adequately address the complexities of DFIs. The high proportion of participants lacking formal DFI instruction reinforces the need for curricular reform. Existing programs across the MENA region prioritize biomedical and regulatory content while neglecting applied patient-facing competencies such as counseling and communication (25, 26). Simulation-based learning, cultural case studies, and integration of traditional medicine examples into pharmacotherapy teaching could bridge this gap and prepare students for real-world counseling.

Internationally, pharmacy education models in high-income countries have successfully incorporated interprofessional learning and cultural competence modules (27, 37). Adapting these frameworks to the Saudi context could enhance patient-centered education while respecting local dietary and cultural practices. Cultural alignment is particularly crucial, as pharmacists working in regions with prevalent traditional herbal use must tailor counseling to patients’ dietary customs to improve adherence and trust (38, 39). Regional calls for culturally contextualized DFI counseling guidelines further support this approach (40).

Continuing professional development (CPD) offers a practical mechanism to address knowledge retention and practice gaps post-graduation. CPD participation has been shown to enhance pharmacist competence and confidence in areas such as dietary counseling and adverse event reporting (41, 42). Effective CPD should be grounded in local dietary habits and patient communication norms to ensure relevance and sustainability. Research suggests that structured CPD initiatives directly improve professional performance, particularly when aligned with competency-based standards (43, 44). Integrating mandatory, DFI-specific modules into existing CPD frameworks could therefore enhance the ability of pharmacists to manage complex medication regimens safely.

Cultural competence and interprofessional collaboration represent vital dimensions of safe medication practice. Studies emphasize that pharmacists’ understanding of patients’ cultural and dietary patterns significantly affects counseling quality and patient adherence (45–47). Collaborative learning models, including interprofessional education (IPE), foster shared responsibility among healthcare providers, reducing the likelihood of DFI-related errors (22). Integrating cultural competence and interprofessional training within pharmacy curricula ensures that healthcare professionals can navigate complex interactions involving traditional diets, supplements, and prescribed medications effectively (38, 39).

While these findings provide valuable insights, several limitations should be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design limits causal inference, and self-reported data may be subject to recall and social desirability bias, especially concerning counseling behaviors. The convenience sampling approach constrains generalizability, and the study did not assess participants’ personal cultural beliefs or traditional medicine practices, which may influence DFI counseling performance. Additionally, although participants were recruited from all major Saudi regions using a stratified approach, regional representation was uneven, with a higher proportion of respondents from the Southern region (36.6%). This imbalance may reflect differential response rates and could introduce non-response bias, meaning that the findings may be more reflective of the Southern region’s healthcare professionals than of the entire national population. Future studies should consider proportional stratification or weighting to achieve a more balanced representation across regions.

Collectively, the results suggest that pharmacy education and professional training in Saudi Arabia would benefit from explicit instruction on DFI identification, management, and culturally competent counseling. Integrating case-based and simulation learning, pharmacovigilance modules, and patient communication exercises can strengthen applied knowledge and skills. Expanding CPD programs to include DFI-specific content and incorporating culturally relevant examples would further reinforce pharmacist readiness. At the policy level, developing national DFI counseling guidelines and reporting protocols under the Saudi Commission for Health Specialties (SCFHS) could standardize practice and align with Vision 2030’s commitment to healthcare excellence. Future research should adopt mixed-methods designs to explore how traditional beliefs and cultural factors influence DFI counseling, ultimately informing evidence-based educational interventions and safer pharmacotherapy practices.

Conclusion

This study identified significant gaps in healthcare professionals’ knowledge and counseling practices regarding drug–food interactions (DFIs) in Saudi Arabia. The findings highlight the need for structured educational reform and continuous professional development focusing on DFI management, pharmacovigilance, and culturally competent counseling. Applied knowledge and patient communication may be strengthened through the integration of simulation-based learning, pharmacovigilance training, and case-based instruction into pharmacy curricula, together with tailored CPD programs. Strengthening healthcare provider competency in these areas will ultimately enhance medication safety, patient adherence, and overall therapeutic outcomes.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AS: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Resources, Visualization. SW: Investigation, Supervision, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology. MA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all the healthcare professionals who participated in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. ChatGPT (OpenAI) was used solely for language editing and formatting assistance. All analytical decisions, data interpretation, and final text were reviewed and verified by the author prior to submission, in accordance with journal policy.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

CI, Confidence Interval; CPD, Continuing Professional Development; CYP450, Cytochrome P450; DFI, Drug–Food Interaction; HCP, Healthcare Professional; IQR, Interquartile Range; IR, Immediate Release; KAP, Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices; AOI, Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitor; Q1, Q3, First Quartile, Third Quartile; SD, Standard Deviation.

References

1.

Petric D. Drug Interactions and Drug Interaction Checkers. San Francisco, CA: Academia;(2021), 10.20935/AL3530

2.

Mahlknecht A Krisch L Nestler N Bauer U Letz N Zenz D et al Impact of training and structured medication review on medication appropriateness and patient-related outcomes in nursing homes: results from the interventional study InTherAKT. BMC Geriatr. (2019) 19:257. 10.1186/s12877-019-1263-3

3.

Osuala E Tlou B Ojewole E . Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards drug-food interactions among patients at public hospitals in eThekwini, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.Afr Health Sci. (2022) 22:681–90. 10.4314/ahs.v22i1.79

4.

Riaz Mk . Potential drug-drug interactions and strategies for their detection and prevention.Farmacia. (2019) 67:572–9. 10.31925/farmacia.2019.4.3

5.

Boullata J Hudson L . Drug-nutrient interactions: a broad view with implications for practice.J Acad Nutr Diet. (2012) 112:506–17. 10.1016/j.jada.2011.09.002

6.

Boullata J . Drug and nutrition interactions: not just food for thought.J Clin Pharm Ther. (2013) 38:269–71. 10.1111/jcpt.12075

7.

Sciarra T Ciccotti M Aiello P Minosi P Munzi D Buccolieri C et al Polypharmacy and nutraceuticals in veterans: pros and Cons. Front Pharmacol. (2019) 10:994. 10.3389/fphar.2019.00994

8.

Anderson J Fox J . Potential food-drug interactions in long-term care.J Gerontol Nurs. (2012) 38:38–46. 10.3928/00989134-20120307-04

9.

Paśko P Rodacki T Domagała-Rodacka R Owczarek D . A short review of drug-food interactions of medicines treating overactive bladder syndrome.Int J Clin Pharm. (2016) 38:1350–6. 10.1007/s11096-016-0383-5

10.

Gezmen-Karadağ M Çelik E Kadayifçi FZ Yeşildemir Ö Öztürk YE Ağagündüz D . Role of food-drug interactions in neurological and psychological diseases.Acta Neurobiol Exp. (Wars) (2018) 78:187–97. Available online at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30295676

11.

Choi J Ko C . Food and drug interactions.J Lifestyle Med. (2017) 7:1–9. 10.15280/jlm.2017.7.1.1

12.

Deng J Zhu X Chen Z Fan C Kwan H Wong C et al A review of food-drug interactions on oral drug absorption. Drugs. (2017) 77:1833–55. 10.1007/s40265-017-0832-z

13.

Sajid S Sultana R Masaratunnisa M Naaz S Adil M . A questionnaire study of food – drug interactions to assess knowledge of people from diverse backgrounds.Asian J Med Heal. (2017) 5:1–9. 10.9734/AJMAH/2017/33682

14.

Briguglio M Hrelia S Malaguti M Serpe L Canaparo R Dell’Osso B et al Food bioactive compounds and their interference in drug pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profiles. Pharmaceutics. (2018) 10:277. 10.3390/pharmaceutics10040277

15.

Ghezzi-Kopel K . Cochrane interactive learning.J Med Libr Assoc. [Internet] (2018) 106:577–9.

16.

Harnik S Ungar B Loebstein R Ben-Horin S . A Gastroenterologist’s guide to drug interactions of small molecules for inflammatory bowel disease.United Eur Gastroenterol J. (2024) 12:627–37. 10.1002/ueg2.12559

17.

Quesnelle K Zaveri N Schneid S Blumer J Szarek J Kruidering M et al Design of a foundational sciences curriculum: applying the ICAP framework to pharmacology education in integrated medical curricula. Pharmacol Res Perspect. (2021) 9:e00762. 10.1002/prp2.762

18.

Mussina A Smagulova G Veklenko G Tleumagambetova B Seitmaganbetova N Zhaubatyrova A et al Effect of an educational intervention on the number potential drug-drug interactions. Saudi Pharm J. (2019) 27:717–23. 10.1016/j.jsps.2019.04.007

19.

Edar A Tongco A Arizalita B Baldomar L Leon N Manlimos J et al Teaching strategies in simulator-based courses: basis for faculty development program. JPAIR Institutional Res. (2024) 22:112–29. 10.7719/irj.v22i1.885

20.

Kim K Xie N Hammersmith L Berrocal Y Roni M . Impact of virtual reality on pharmacology education: a pilot study.Cureus. (2023) 15:e43411. 10.7759/cureus.43411

21.

Pravitasari E Pamungkas GA . The influence of information services and educational strategies on the public’s understanding of drugs.J World Sci. (2023) 2:1123–9. 10.58344/jws.v2i7.345

22.

Degefu N Getachew M Amare F . Knowledge of drug-food interactions among healthcare professionals working in public hospitals in ethiopia.J Multidiscip Healthc. (2022) 15:2635–45.

23.

Abualhasan M Tahan S Nassar R Damere M Salameh H Zyoud H . Pharmacists’ knowledge of drug food administration and their appropriate patient counseling a cross-sectional study from Palestine.J Health Popul Nutr. (2023) 42:99. 10.1186/s41043-023-00444-9

24.

Zaidi S Mgarry R Alsanea A Almutairi S Alsinnari Y Alsobaei S et al A questionnaire-based survey to assess the level of knowledge and awareness about drug-food interactions among general public in Western Saudi Arabia. Pharmacy. (2021) 9:76. 10.3390/pharmacy9020076

25.

Abdollahi M Salehi S Taherzadeh Z Eslami S . Survey of adherence to time standards to prevent food and drug interaction in the hospitalized patients.J Res Heal. (2018) 8:85–92. 10.29252/acadpub.jrh.8.1.85

26.

Jelińska M Białek A Czerwonka M Skrajnowska D Stawarska A Bobrowska-Korczak B . Knowledge of food-drug interactions among medical university students.Nutrients. (2024) 16:2425. 10.3390/nu16152425

27.

Khong J Tuan Mahmood T Tan S Voo J Wong S . Knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) on food-drug interaction (FDI) among pharmacists working in government health facilities in Sabah, Malaysia.PLoS One. (2024) 19:e0304974. 10.1371/journal.pone.0304974

28.

Yılmaz Z Sancar M Okuyan B Yeşildağ O İzzettin FV . Impact of verbal and web-based patient education programs driven by clinical pharmacist on the adherence and illness perception of hypertensive patients.Indian J Pharm Educ Res. (2020) 54:s695–704. 10.5530/ijper.54.3s.170

29.

Bhattad P Pacifico L . Empowering patients: promoting patient education and health literacy.Cureus. (2022) 14:e27336. 10.7759/cureus.27336

30.

Soon H Geppetti P Lupi C Kho B . Medication Safety. In: DonaldsonLRicciardiWSheridanSTartagliaReditors. Textbook of Patient Safety and Clinical Risk Management.Cham, CH: Springer (2020). 10.1007/978-3-030-59403-9_31

31.

Aydinli A Cerit K . An analysis of the psychometric properties of the medication safety competence scale in Turkish.BMC Nurs. (2024) 23:578. 10.1186/s12912-024-02240-0

32.

Abu Farha R Abu Hammour K Rizik M Aljanabi R Alsakran L . Effect of educational intervention on healthcare providers knowledge and perception towards pharmacovigilance: a tertiary teaching hospital experience.Saudi Pharm J. (2018) 26:611–6. 10.1016/j.jsps.2018.03.002

33.

Abdulrasool Z . The development of a pharmacovigilance system in Bahrain.Saudi Pharm J. (2022) 30:825–41. 10.1016/j.jsps.2022.03.009

34.

Garashi H Steinke D Schafheutle EIA . Systematic review of pharmacovigilance systems in developing countries using the WHO pharmacovigilance indicators.Ther Innov Regul Sci. (2022) 56:717–43. 10.1007/s43441-022-00415-y

35.

Alshammari T Mendi N Alenzi K Alsowaida Y . Pharmacovigilance systems in Arab countries: overview of 22 Arab countries.Drug Saf. (2019) 42:849–68. 10.1007/s40264-019-00807-4

36.

Al-Zubiedi S Younus M Al-Khalidi S Ekilo M Alshammari T . Pharmacovigilance regulatory actions by national pharmacovigilance centers in Arab countries following COVID-19 pandemic.Expert Opin Drug Saf. (2024) 22:165–74. 10.1080/14740338.2022.2108398

37.

Ana-Maria P Oana R Georgescu C Nicoleta M Liliana M Rosca S et al Food-drug interactions - a short review of the particularities of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics molecular stage correlations. J Pharm Negat Results. (2022):98–102. 10.47750/pnr.2022.13.S09.011

38.

Karagöz M Karadağ M Yıldıran H Ok M . Developing a food and drug interaction knowledge scale for health care professionals: a validity and reliability study.Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilim Derg. (2022) 13:48–59. 10.22312/sdusbed.1033924

39.

Thiab S Barakat M Al-Qudah R Abutaima R Jamal R Riby P . The perception of Jordanian population towards concomitant administration of food, beverages and herbs with drugs and their possible interactions: a cross-sectional study.Int J Clin Pract. (2021) 75:e13780. 10.1111/ijcp.13780

40.

Kemaloğlu M Kemaloğlu E . Examining the food label reading habits and attitudes towards healthy nutrition among healthcare professionals: a cross-sectional study.Turkish J Heal Sci Life. (2024) 3:113–20. 10.56150/tjhsl.1445060

41.

Gebregzabher E Tesfaye F Cheneke W Negesso A Kedida G . Continuing professional development (CPD) training needs assessment for medical laboratory professionals in Ethiopia.Hum Resour Health. (2022) 21:47. 10.1186/s12960-023-00837-1

42.

Darwish R Ammar K Rumman A Jaddoua S . Perception of the importance of continuing professional development among pharmacists in a middle east country: a cross-sectional study.PLoS One. (2023) 18:e0283984. 10.1371/journal.pone.0283984

43.

Wheeler J Chisholm-Burns M . The benefit of continuing professional development for continuing pharmacy education.Am J Pharm Educ. (2018) 82:6461. 10.5688/ajpe6461

44.

Wallace S May S . Assessing and enhancing quality through outcomes-based continuing professional development (CPD): a review of current practice.Vet Rec. (2016) 179:515–20. 10.1136/vr.103862

45.

Singla N Jindal A Mahapatra D . Role of pharmacist in nutrition management-the unexplored path.Indian J Pharm Pract. (2023) 16:83–8. 10.5530/ijopp.16.2.14

46.

Putri AE Ma’wa J Habibie Bahar MA . Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of hospital pharmacists regarding clinically relevant drug interactions: A multi-center regional survey in Indonesia.Pharmacia. (2024) 71:1–9.

47.

Osuala E Tlou B Ojewole E . Assessment of knowledge of drug-food interactions among healthcare professionals in public sector hospitals in eThekwini, KwaZulu-Natal.PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0259402. 10.1371/journal.pone.0259402

Summary

Keywords

drug–food interactions, pharmacist counseling, cultural competency, pharmacovigilance, healthcare education

Citation

Shalali A, Wali SM and Aldurdunji MM (2025) Knowledge, counseling practices, and educational gaps related to drug–food interactions among healthcare professionals in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Front. Med. 12:1719936. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1719936

Received

07 October 2025

Revised

30 October 2025

Accepted

25 November 2025

Published

16 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Zhiyao He, Sichuan University, China

Reviewed by

Nabil Albaser, Al-Razi University, Yemen

Abeer Abdelkader, Minia University, Egypt

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Shalali, Wali and Aldurdunji.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohammed M. Aldurdunji, mmdurdunji@uqu.edu.sa

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.