Abstract

Objective:

Cystatin C (CysC), as a crucial and sensitive indicator for renal function, has gradually drawn attention for its role in diabetic complications. This study aims to investigate the association between serum CysC levels and diabetic retinopathy (DR).

Method:

This cross-sectional study enrolled 818 individuals with type 2 diabetes, including 227 DR patients and 591 patients without DR. All subjects underwent detailed clinical evaluations, including blood glucose, lipid, renal function indicators, and fundus examinations. Logistic regression analyses were applied to assess the correlation between CysC and DR.

Results:

The serum CysC levels in DR patients was significantly higher than those of the controls (p < 0.001). Besides, CysC was negatively correlated with fasting glucose (r = −0.080), TC (r = −0.090), HDL-C (r = −0.107), and albumin (r = −0.222) (all p < 0.05). Compared to the 1st tertile of CysC, the prevalence of DR was increased in the 3rd CysC tertile (OR = 2.14, 95%CI: 1.20–3.82, p = 0.01). This association was more obvious in patients with a long duration of diabetes exceeding 10 years or in non-elderly patients.

Conclusion:

Patients with higher serum CysC levels have an elevated risk of DR in the T2DM population. Future large-scale studies should explore the potential mechanism of CysC in DR and evaluate its potential as a therapeutic target.

1 Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is currently one of the most severe and prevalent chronic diseases. Diabetic retinopathy (DR), a major microvascular complication of T2DM, is the leading cause of vision loss among working-age populations worldwide (1). Epidemiological data shows that in 2020, over 103 million diabetic patients worldwide suffered from DR. It is estimated that by 2045, this number will increase to 160 million (2). Compared to other major causes of blindness, DR was the only disease whose age-standardized prevalence did not decline during the period from 1990 to 2020 (3). In addition to affecting vision, DR is linked to heightened risks of depression and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (4–7). Therefore, identifying modifiable risk factors for DR at an early stage is essential for its prevention and treatment.

Cystatin C (CysC), a sensitive and effective indicator for renal function, is a lysosomal cysteine proteinases inhibitor generated by all nucleated cells (8). High levels of CysC are closely related to oxidative stress, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction. Additionally, an increase in CysC concentration may enhance the suppression of cysteine proteases, potentially contributing to the onset and progression of microvascular and macrovascular diseases (3). In addition to being associated with kidney diseases, patients with higher CysC levels also have a greater risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all-cause mortality (9).

Recent studies have indicated a strong association between CysC and the risk of diabetes and its complications (10). A retrospective study showed that compared with the control group, the levels of CysC in patients with diabetes remained unchanged, while the levels of CysC in patients with DR increased (11). He et al. (12) reported that the serum CysC level was correlated with the severity of DR and can predict DR that poses a threat to vision. Besides, Kim et al. (13) found that the serum CysC level was independently associated with the prevalence of DR and coronary heart disease in a group of Korean T2DM patients without nephropathy. Moreover, several studies have shown that CysC can serve as a specific biomarker for patients with DR (11, 14, 15). Xiong et al. (16) revealed that elevated CysC levels is tightly correlated with microvascular rarefaction in optic disc and macular regions, as well as diminished retinal neural layers among diabetic subjects. Besides, CysC was a crucial and independent predictor of peripheral arterial stiffness among T2DM subjects with chronic kidney disease (17). However, prior studies involved participants with a broad spectrum of kidney functions, which means the link between CysC and DR might be influenced by factors related to kidney issues. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore the relationship between higher serum CysC levels and the risk of DR in T2DM patients with normal renal function.

2 Methods

2.1 Study participants

This cross-sectional study included 818 subjects in the Department of Endocrinology and Ophthalmology of Chongming Branch, Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine between March 2020 and November 2024. Patients aged ≥18 years diagnosed with T2DM according to Chinese Diabetes Society criteria were included. Exclusion criteria were as follows: non-T2DM patients; patients with hyperthyroidism, patients with incomplete information, patients with renal dysfunction (serum creatine >1.3 mg/dL, urine albumin excretion rate ≥30 mg/day, or estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/min/1.73m2); patients with diabetic acute complications, and severe or recurrent hypoglycemic events; patients with malignant tumors, psychiatric disorders, infections, or other organ failures; and patients with glaucoma, previous vitreous surgery, or cataract. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chongming Branch, Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital (Approval Number: SHSYCM-IEC-1.0/25-YF/04).

2.2 Data collection

Clinical data were obtained from the electronic medical records, including age, sex, height, weight, smoking and drinking status, duration of diabetes, medical history and usage of insulin. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight divided by height squared. Smoking refers to a self-reported history of smoking or currently smoking. Hypertension refers to a resting blood pressure of 140 mmHg systolic or 90 mmHg diastolic or higher on repeated measurements, or the use of antihypertensive medications (18). Laboratory tests include CysC, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), fasting blood glucose (FBG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), total cholesterol (TC), albumin, and serum creatinine were measured using an automatic biochemical analyzer in the hospital’s medical laboratory according to the routine procedures.

All participants underwent a standardized clinical examination. DR was evaluated by trained ophthalmologists according to the presence of one or more of the following indicators: retinal microvascular abnormalities, hard exudates, microaneurysm formation, venous beading, retinal neovascularization, intraretinal hemorrhage, fibrous proliferation, cotton-wool spots, and macular edema. The control group had no manifestations or clinical history of DR, and imaging studies confirmed the absence of DR.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Unless stated otherwise, quantitative data were shown as mean ± standard, while qualitative variables were expressed as numbers and percentages. Group differences were assessed using Student’s t-test or chi-square tests. Spearman correlation analysis was performed to determine the correlation between CysC and metabolic indicators. The relationship between CysC and DR prevalence was analyzed using three multivariable logistic regression models: (1) Model 1: unadjusted; (2) Model 2: adjusted for age, sex, smoking, drinking, and hypertension; (3) Model 3: further adjustments for other parameters includes BMI, diabetic duration, insulin therapy, HbA1c, albumin, and serum creatinine. Data analyses were conducted using SPSS 26.0 and GraphPad Prism 9.0. Statistical significance was set as p < 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 Baseline characteristics of the cohort

A total of 818 participants were included, of whom 591 were controls and 227 had DR. The average age was 61.5 ± 10.9 years, 533 (63.8%) were male, and the mean CysC levels were 0.89 ± 0.21 mg/L. The percentage of subjects with hypertension and usage of insulin in DR subjects were significantly higher than that of in controls (p < 0.05). They were also more prone to having a higher index of BMI and a longer duration of diabetes. Moreover, DR subjects exhibited higher levels of HbA1c, serum creatinine, and CysC, but lower albumin levels (Table 1).

Table 1

| Variables | All (n = 818) | CON (n = 591) | DR (n = 227) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 61.5 ± 10.9 | 61.5 ± 11.3 | 61.6 ± 10.0 | 0.983 |

| Male, % | 533 (63.8) | 383 (64.8) | 139 (61.2) | 0.341 |

| Smoking, % | 272 (33.3) | 202 (34.2) | 70 (31.0) | 0.376 |

| Drinking, % | 139 (17.0) | 104 (17.6) | 35 (15.5) | 0.467 |

| Hypertension, % | 486 (59.4) | 336 (56.7) | 151 (66.5) | 0.010 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.3 ± 3.3 | 24.1 ± 3.3 | 24.7 ± 3.4 | 0.025 |

| Diabetic duration, years | 11.1 ± 7.3 | 10.1 ± 7.4 | 13.8 ± 6.5 | <0.001 |

| Insulin therapy, % | 436 (53.3) | 279 (47.2) | 157 (69.2) | <0.001 |

| Fasting glucose, mmol/L | 7.7 ± 2.4 | 7.6 ± 2.3 | 7.9 ± 2.7 | 0.108 |

| HbA1c, % | 8.9 ± 2.2 | 8.7 ± 2.2 | 9.2 ± 1.9 | 0.012 |

| TG, mg/dL | 170.1 ± 134.2 | 169.2 ± 135.1 | 172.7 ± 132.1 | 0.738 |

| TC, mg/dL | 170.1 ± 42.8 | 169.1 ± 40.5 | 172.8 ± 48.4 | 0.308 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | 41.8 ± 11.2 | 41.8 ± 11.1 | 41.9 ± 11.6 | 0.872 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 108.2 ± 38.8 | 107.2 ± 36.6 | 110.9 ± 44.1 | 0.254 |

| Albumin, g/L | 38.7 ± 3.8 | 39.0 ± 3.7 | 37.7 ± 3.6 | <0.001 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 0.81 ± 0.20 | 0.79 ± 0.19 | 0.84 ± 0.22 | 0.008 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73m2 | 101.4 ± 60.46 | 103.7 ± 69.0 | 95.5 ± 27.2 | 0.083 |

| CysC, mg/L | 0.89 ± 0.21 | 0.86 ± 0.20 | 0.96 ± 0.23 | <0.001 |

Baseline characteristics of the cohort.

The values represent the mean ± standard deviation.

BMI, body mass index; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; TG, triglycerides; TC, total cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rates; CysC, cystatin C.

3.2 Correlation between CysC and metabolic indicators

The CysC values negatively correlated with FBG (r = −0.080, Figure 1A), TC (r = −0.090), HDL-C (r = −0.107), and albumin (r = −0.222, Figure 1B) (all p < 0.05). Moreover, there was a positive correlation between CysC and serum creatinine (r = 0.577, p < 0.001, Figure 1C) (Table 2 and Figure 1D).

Figure 1

Association between serum CysC levels and metabolic indicators. (A) The correlation between CysC and FBG. (B) The correlation between CysC and albumin. (C) The correlation between CysC and serum creatinine. (D) Correlation results displayed as heat maps.

Table 2

| Variables | r | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Fasting glucose | −0.080 | 0.023 |

| HbA1c | −0.051 | 0.169 |

| TG | 0.035 | 0.319 |

| TC | −0.090 | 0.010 |

| HDL-C | −0.107 | 0.002 |

| LDL-C | −0.063 | 0.073 |

| Albumin | −0.222 | <0.001 |

| Serum creatinine | 0.577 | <0.001 |

Correlation of CysC and metabolic indicators.

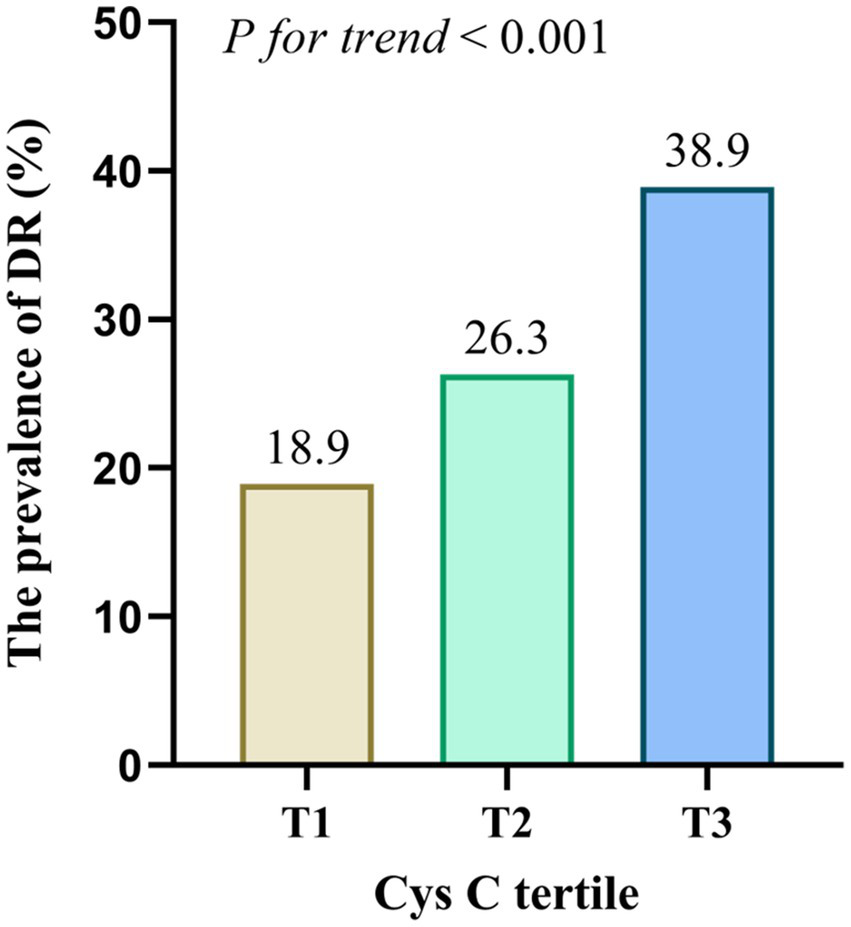

3.3 Association between the CysC and DR

Participants were categorized into three groups based on the tertiles of CysC levels: T1 (≤0.78 mg/L), T2 (0.79–0.95 mg/L), and T3 (≥0.96 mg/L). The percentage of DR prevalence were 18.9, 26.3, and 38.9% in the T1, T2, and T3 group, respectively (pfor trend < 0.001, Figure 2). To further determine whether CysC was promising as a predictor of DR, three multivariable logistic regression analysis were performed. When taking the T1 tertile of CysC as a reference, the prevalence of DR was increased in another two groups, with the odds ratio (OR) [95% confidence interval (CI)] were 1.53 (1.03–2.29) for T2 and 2.74 (1.86–4.03) for T3 (all p < 0.05, Table 3). Besides, the association remains statistically significant after the adjustment of age, sex, smoking, and drinking, and hypertension (Model 2). Moreover, a slightly higher risk was observed in the highest CysC tertile after adjustments for Model 2 variables and BMI, diabetic duration, insulin therapy, HbA1c, albumin, and serum creatinine (OR = 2.14, 95%CI: 1.20–3.82, p = 0.01).

Figure 2

Prevalence of DR across the CysC tertiles. The prevalence of DR was increased in T2 and T3 groups compared to T1 group (p < 0.001).

Table 3

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| T1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| T2 | 1.53 (1.03–2.29) | 0.037 | 1.71 (1.13–2.60) | 0.011 | 1.53 (0.95–2.49) | 0.083 |

| T3 | 2.74 (1.86–4.03) | <0.001 | 3.35 (2.19–5.12) | <0.001 | 2.14 (1.20–3.82) | 0.010 |

| p for trend | <0.001 | 0.008 | ||||

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of CysC for DR.

Model 1: unadjusted.

Model 2: adjusted for age, sex, smoking, drinking, and hypertension.

Model 3: adjusted for age, sex, smoking, drinking, hypertension, BMI, diabetic duration, insulin therapy, HbA1c, albumin, and serum creatinine.

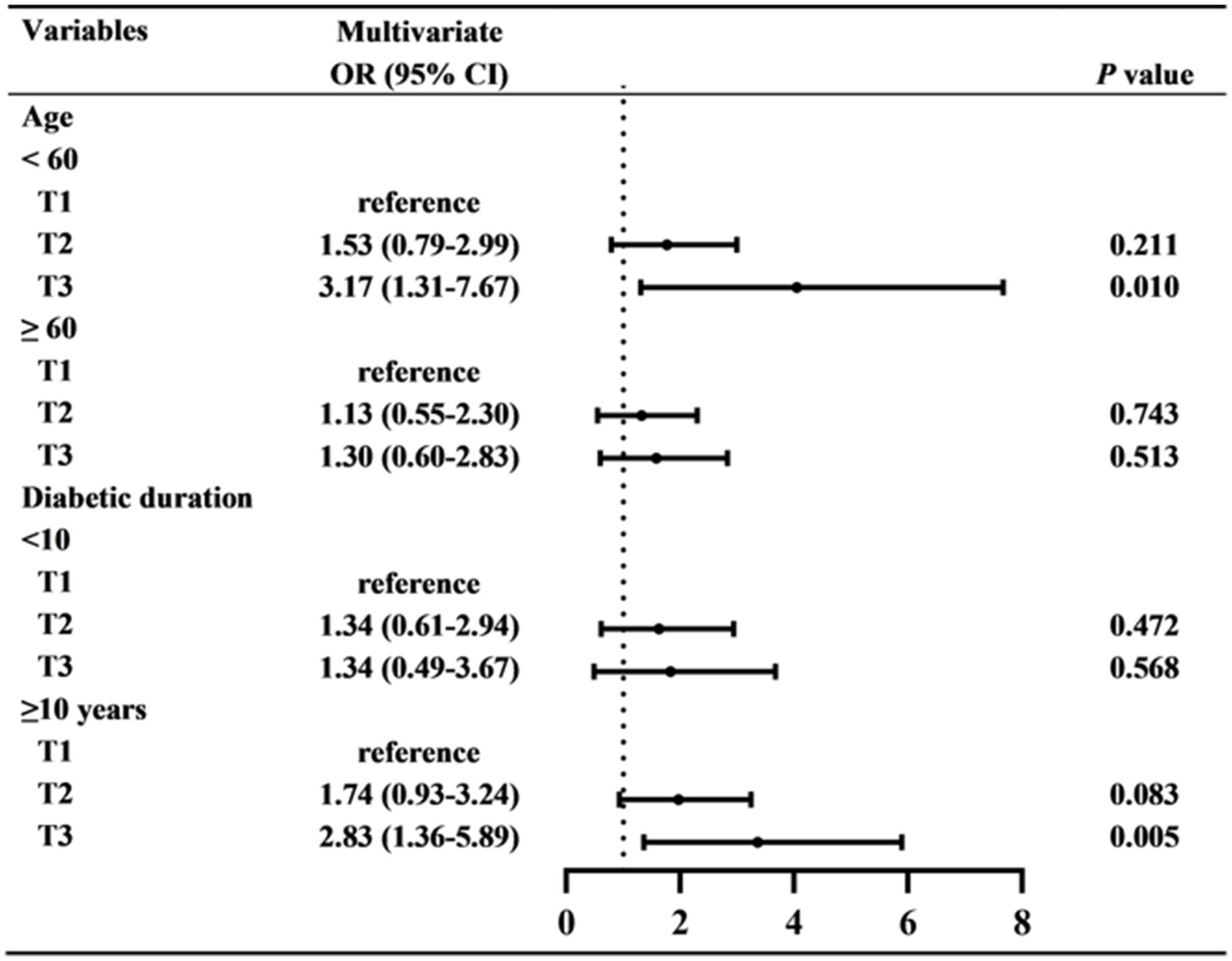

3.4 Sensitivity analysis

Subsequently, subgroup analyses were used to further investigate the relationship between CysC and DR (Figure 3). It has been found that higher serum CysC values were related to the prevalence of DR in patients aged below 60 years (OR = 3.17, 95%CI: 1.31–7.67, p = 0.010) and diabetic duration more than 10 years (OR = 2.83, 95%CI: 1.36–5.89, p = 0.005). However, for patients aged over 60 years and diabetic duration below 10 years, higher CysC did not indicate a greater risk of DR.

Figure 3

The relationship between CysC and DR in subgroups. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were used in subgroups based on age (<60 OR ≥60 years), and diabetic duration (<10 OR ≥10 years).

4 Discussion

DR is a severe microvascular complication of diabetes mellitus, posing a significant threat to the vision of patients. The pathogenesis of DR is intricate, with multiple contributing factors and mechanisms, including oxidative stress, inflammation, metabolic disorders caused by long-term hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, and endothelial dysfunction (19). It is of great clinical significance to identify efficient and sensitive biomarkers for DR that can be used for early diagnosis, disease progression monitoring, and prognosis assessment. This study revealed that the value of cystatin C was correlated with FBG, TC, HDL-C, and albumin, but not with HbA1c, mainly consistent with previous findings (20). Another study found a positive correlation between CysC and HbA1c in in Korean Adults (21). Besides, Stankute et al. (22) reported that CysC was negatively associated with HbA1c and HDL. Moreover, the present study determined that higher serum CysC levels were associated with the risk of DR in T2DM patients with normal renal function. As a sensitive indicator for evaluating renal function, CysC testing is convenient and fast, which could be used as an effective and simple tool for DR risk assessment in clinical practice.

The positive correlations among CysC and cardiovascular outcomes and mortality have been confirmed in diverse populations, including general population with normal eGFR (23), chronic kidney disease patients (24), obstructive sleep apnea subjects (25), patients with metabolic syndrome (9), and patients with coronary heart disease (26). Furthermore, CysC has been pinpointed as a potential indicator for various diabetic complications, including early renal damage (22), peripheral artery disease (27), diabetic foot ulcers (28), diabetic peripheral neuropathy (29), and DR (11). A cross-sectional study among the Indian population revealed that CysC may emerged as a biomarker for screening sight-threatening DR (30). Our results were mainly consistent with previous studies, which have shown that CysC levels was markedly elevated in DR patients compared to the controls (11–13, 15, 30). He et al. (12) reported that the serum CysC level was correlated with the severity of DR and can predict DR that poses a threat to vision. Besides, Kim et al. (13) found that the serum CysC level was independently associated with the prevalence of DR and coronary heart disease in a group of Korean T2DM patients without nephropathy. However, the subjects recruited in previous studies had a broad spectrum of renal functions, the relationship between CysC and DR might be influenced by renal dysfunction-related confounding factors. The present study excluded patients with nephropathy to eliminate the confounding effect of declining renal function, which helps to make our results more convincing. In addition, this study found that CysC was correlated with fasting glucose, TC, HDL-C, and albumin. These factors have also been proven to be associated with DR prevalence. It has been reported that CysC was associated with dyslipidemia (20). A population-based study includes individuals without chronic kidney disease revealed that for every one standard deviation increase in serum CysC levels, the risk of dyslipidemia increased by 22% (31).

The fundamental mechanism for the relationship between CysC and DR has not been fully elucidated. One of the key mechanisms may be that CysC causes chronic inflammatory responses. CysC is mainly synthesized in the retinal pigment epithelium and secreted from the basal side (32). Multiple studies have revealed a significant linear correlation between CysC and the levels of classic inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), high-sensitivity CRP, and IL6 (32–35). Increased CRP levels are involved in the pathogenesis of DR. In the streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat models, overexpression of human CRP protein exacerbates diabetic-induced retinal leukocyte stasis and degranulated capillary formation. In retinal cell lines, human CRP protein treatment induces overexpression of reactive oxygen species and cell death. Moreover, CRP induced the upregulation of pro-inflammatory, pro-angiogenic, and pro-oxidative parameters by CD32 and NF-κB signaling pathways (36). There was a significant association between serum levels of CysC and oxidative stress index (37). CysC has been proven to be involved in macular degeneration, neovascularization, vascular integrity, inflammation, and neuronal degeneration (12). The pathophysiological alternations of DR include inflammation, optic neuropathy, macular edema, oxidative stress, and retinal neovascularization (38). The shared pathways between CysC and DR might partially clarify their strong connection.

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) participates in the regulation of endothelial cell proliferation, assembly, maintenance and survival (39). However, in the diabetic state, VEGF expression is upregulated, leading to deviation from its normal physiological function and triggering multiple pathological manifestations, such as enhanced endothelial permeability, angiogenesis, and activation of inflammatory mediators, which are essential in the development and pathophysiology of DR. Anti-VEGF antagonists are widely used for treating ocular diseases through intravitreal injection (40). A study on patients with systemic lupus erythematosus found that CysC was positively correlated with VEGF (41). Additionally, CysC participates in the regulation of VEGF secretion in the neurovascular units (42). The evidence indicates that VEGF might serve as a regulatory mechanism connecting CysC and DR. One of the typical characteristics of DR is endothelial cell dysfunction (43). The low reactive hyperemia index indicates more severe endothelial dysfunction. Kreslová et al. (44) found that CysC was independently correlated with a decreased reactive hyperemia index. After adjusting for confounding factors, increased level of CysC was an independent predictor for endothelial dysfunction.

Another important finding of this study is the presence of an age-related difference in the association between serum CysC levels and DR. Higher CysC levels were prominently correlated with DR in subjects aged <60 years, but not in older individuals. A study found that after the age of 50–60, the level of CysC begins to increase significantly. This upward trend may attributed to the gradual decline in renal function, as CysC is mainly cleared through filtration by the kidneys, and reduced renal function leads to its accumulation in the blood (45). Additionally, age is one of the essential risk factors for DR. The relationship between CysC and DR may be obscured by the influence of advanced age.

Although the study excluded patients with renal dysfunction, there are still some limitations. Firstly, the sample size of this study is relatively small, so it may not accurately represent the study population. Secondly, this study employed a cross-sectional design, which means it cannot establish a causal relationship between CysC and the risk of DR. Thirdly, the present study did not analyze the correlation between CysC and VEGF and inflammatory indicators. Further research is still needed to understand their roles in the relationship between CysC and DR. Moreover, more in-depth, prospective, and large-scale studies are required to elucidate the relationship between cystatin C and the distinct severity stages of DR, including non-proliferative DR (varying from mild to severe) and proliferative DR.

In conclusion, higher serum CysC levels in T2DM patients with normal renal function are closely related to DR. CysC may help identify high-risk individuals with DR among patients without kidney disease. Large-scale studies should determine the potential mechanism of the link between CysC and DR and investigate whether CysC-targeting therapy can halt disease initiation and progression.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chongming Branch, Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital (Approval Number: SHSYCM-IEC-1.0/25-YF/04). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because Informed consent was not required due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Author contributions

QG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. YX: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This project was supported by Research Fund of Anhui Institute of Translational Medicine (2022zhyx-C73).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Song P Yu J Chan KY Theodoratou E Rudan I . Prevalence, risk factors and burden of diabetic retinopathy in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. (2018) 8:010803. doi: 10.7189/jogh.08.010803

2.

Teo ZL Tham YC Yu M Chee ML Rim TH Cheung N et al . Global prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and projection of burden through 2045: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. (2021) 128:1580–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.04.027

3.

GBD 2019 Blindness and Vision Impairment Collaborators; Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study . Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: the right to sight: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob Health. (2021) 9:e144–60. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30489-7

4.

Gao S Liu X . Analysis of anxiety and depression status and their influencing factors in patients with diabetic retinopathy. World J Psychiatry. (2024) 14:1905–17. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v14.i12.1905

5.

Liu X Chang Y Li Y Liu Y Chen N Cui J . Association between cardiovascular health and retinopathy in US adults: from NHANES 2005–2008. Am J Ophthalmol. (2024) 266:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2024.05.019

6.

Kha R Kapucu Y Indrakumar M Burlutsky G Thiagalingam A Kovoor P et al . Diabetic retinopathy further increases risk of cardiovascular disease mortality in a high-risk cohort. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:4811. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-86559-x

7.

Modjtahedi BS Wu J Luong TQ Gandhi NK Fong DS Chen W . Severity of diabetic retinopathy and the risk of future cerebrovascular disease, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality. Ophthalmology. (2021) 128:1169–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.12.019

8.

Pottel H Delanaye P Cavalier E . Exploring renal function assessment: creatinine, cystatin C, and estimated glomerular filtration rate focused on the European Kidney Function Consortium Equation. Ann Lab Med. (2024) 44:135–43. doi: 10.3343/alm.2023.0237

9.

Song X Xiong L Guo T Chen X Zhang P Zhang X et al . Cystatin C is a predictor for long-term, all-cause, and cardiovascular mortality in US adults with metabolic syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2024) 109:2905–19. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgae225

10.

Yousefzadeh G Pezeshki S Gholamhosseinian A Nazemzadeh M Shokoohi M . Plasma cystatin-C and risk of developing gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr. (2014) 8:33–5. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2013.10.016

11.

Li Z Li J Zhong J Qu C Du M Tian H et al . Red blood cell count and cystatin C as the specific biomarkers for diabetic retinopathy from diabetes mellitus: a case-control study. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:29288. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-80797-1

12.

He R Shen J Zhao J Zeng H Li L Zhao J et al . High cystatin C levels predict severe retinopathy in type 2 diabetes patients. Eur J Epidemiol. (2013) 28:775–8. doi: 10.1007/s10654-013-9839-2

13.

Kim HJ Byun DW Suh K Yoo MH Park HK . Association between serum cystatin C and vascular complications in type 2 diabetes mellitus without nephropathy. Diabetes Metab J. (2018) 42:513–8. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2018.0006

14.

Ruan Y Zhang P Li X Jia X Yao D . Causal association between cystatin C and diabetic retinopathy: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. J Diabetes Investig. (2024) 15:1626–36. doi: 10.1111/jdi.14273

15.

Yang N Lu YF Yang X Jiang K Sang AM Wu HQ . Association between cystatin C and diabetic retinopathy among type 2 diabetic patients in China: a meta-analysis. Int J Ophthalmol. (2021) 14:1430–40. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2021.09.21

16.

Xiong K Zhang S Zhong P Zhu Z Chen Y Huang W et al . Serum cystatin C for risk stratification of prediabetes and diabetes populations. Diabetes Metab Syndr. (2023) 17:102882. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2023.102882

17.

Luo Y Wang Q Li H Lin W Yao J Zhang J et al . Serum cystatin C is associated with peripheral artery stiffness in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus combined with chronic kidney disease. Clin Biochem. (2023) 118:110593. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2023.110593

18.

Daviglus ML Talavera GA Avilés-Santa ML Allison M Cai J Criqui MH et al . Prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases among Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse backgrounds in the United States. JAMA. (2012) 308:1775–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14517

19.

Yue T Shi Y Luo S Weng J Wu Y Zheng X . The role of inflammation in immune system of diabetic retinopathy: molecular mechanisms, pathogenetic role and therapeutic implications. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:1055087. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1055087

20.

Dejenie TA Abebe EC Mengstie MA Seid MA Gebeyehu NA Adella GA et al . Dyslipidemia and serum cystatin C levels as biomarker of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Front Endocrinol. (2023) 14:1124367. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1124367

21.

Sim EH Lee HW Choi HJ Jeong DW Son SM Kang YH . The association of serum Cystatin C with glycosylated hemoglobin in Korean adults. Diabetes Metab J. (2016) 40:62–9. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2016.40.1.62

22.

Stankute I Radzeviciene L Monstaviciene A Dobrovolskiene R Danyte E Verkauskiene R . Serum cystatin C as a biomarker for early diabetic kidney disease and dyslipidemia in young type 1 diabetes patients. Medicina. (2022) 58:218. doi: 10.3390/medicina58020218

23.

Einwoegerer CF Domingueti CP . Association between increased levels of cystatin C and the development of cardiovascular events or mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arq Bras Cardiol. (2018) 111:796–807. doi: 10.5935/abc.20180171

24.

Shlipak MG Matsushita K Ärnlöv J Inker LA Katz R Polkinghorne KR et al . Cystatin C versus creatinine in determining risk based on kidney function. N Engl J Med. (2013) 369:932–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214234

25.

Li JH Gao YH Xue X Su XF Wang HH Lin JL et al . Association between serum cystatin C levels and long-term cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality in older patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Front Physiol. (2022) 13:934413. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.934413

26.

West M Kirby A Stewart RA Blankenberg S Sullivan D White HD et al . Circulating cystatin C is an independent risk marker for cardiovascular outcomes, development of renal impairment, and long-term mortality in patients with stable coronary heart disease: the LIPID study. J Am Heart Assoc. (2022) 11:e020745. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.020745

27.

Chen T Xiao S Chen Z Yang Y Yang B Liu N . Risk factors for peripheral artery disease and diabetic peripheral neuropathy among patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. (2024) 207:111079. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2023.111079

28.

Zhao J Deng W Zhang Y Zheng Y Zhou L Boey J et al . Association between serum cystatin C and diabetic foot ulceration in patients with type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study. J Diabetes Res. (2016) 2016:8029340. doi: 10.1155/2016/8029340

29.

Hu Y Liu F Shen J Zeng H Li L Zhao J et al . Association between serum cystatin C and diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a cross-sectional study of a Chinese type 2 diabetic population. Eur J Endocrinol. (2014) 171:641–8. doi: 10.1530/EJE-14-0381

30.

PramodKumar TA Sivaprasad S Venkatesan U Mohan V Anjana RM Unnikrishnan R et al . Role of cystatin C in the detection of sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy in Asian Indians with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complicat. (2023) 37:108545. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2023.108545

31.

Huang X Jiang X Wang L Liu Z Wu Y Gao P et al . Serum cystatin C and arterial stiffness in middle-aged and elderly adults without chronic kidney disease: a population-based study. Med Sci Monit. (2019) 25:9207–15. doi: 10.12659/MSM.916630

32.

Alizadeh P Smit-McBride Z Oltjen SL Hjelmeland LM . Regulation of cysteine cathepsin expression by oxidative stress in the retinal pigment epithelium/choroid of the mouse. Exp Eye Res. (2006) 83:679–87. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.03.009

33.

Shlipak MG Katz R Cushman M Sarnak MJ Stehman-Breen C Psaty BM et al . Cystatin-C and inflammatory markers in the ambulatory elderly. Am J Med. (2005) 118:1416. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.060

34.

Chew C Pemberton PW Husain AA Haque S Bruce IN . Serum cystatin C is independently associated with renal impairment and high sensitivity C-reactive protein in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. (2013) 31:251–5.

35.

Özdemir Başer Ö Göçmen AY Aydoğan Kırmızı D . The role of inflammation, oxidation and cystatin-C in the pathophysiology of polycystic ovary syndrome. Turk J Obstet Gynecol. (2022) 19:229–35. doi: 10.4274/tjod.galenos.2022.29498

36.

Qiu F Ma X Shin YH Chen J Chen Q Zhou K et al . Pathogenic role of human C-reactive protein in diabetic retinopathy. Clin Sci. (2020) 134:1613–29. doi: 10.1042/CS20200085

37.

Yalcin S Ulas T Eren MA Aydogan H Camuzcuoglu A Kucuk A et al . Relationship between oxidative stress parameters and cystatin C levels in patients with severe preeclampsia. Medicina. (2013) 49:118–23.

38.

Sinclair SH Schwartz S . Diabetic retinopathy: new concepts of screening, monitoring, and interventions. Surv Ophthalmol. (2024) 69:882–92. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2024.07.001

39.

Behl T Kotwani A . Exploring the various aspects of the pathological role of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in diabetic retinopathy. Pharmacol Res. (2015) 99:137–48. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.05.013

40.

Porta M Striglia E . Intravitreal anti-VEGF agents and cardiovascular risk. Intern Emerg Med. (2020) 15:199–210. doi: 10.1007/s11739-019-02253-7

41.

Gao D Shao J Jin W Xia X Qu Y . Correlations of serum cystatin C and hs-CRP with vascular endothelial cell injury in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Panminerva Med. (2018) 60:151–5. doi: 10.23736/S0031-0808.18.03466-3

42.

Zou J Chen Z Wei X Chen Z Fu Y Yang X et al . Cystatin C as a potential therapeutic mediator against Parkinson's disease via VEGF-induced angiogenesis and enhanced neuronal autophagy in neurovascular units. Cell Death Dis. (2017) 8:e2854. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.240

43.

Zhou Y Xuan Y Liu Y Zheng J Jiang X Zhang Y et al . Transcription factor FOXP1 mediates vascular endothelial dysfunction in diabetic retinopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. (2022) 260:3857–67. doi: 10.1007/s00417-022-05698-3

44.

Kreslová M Jehlička P Sýkorová A Rajdl D Klásková E Prokop P et al . Circulating serum cystatin C as an independent risk biomarker for vascular endothelial dysfunction in patients with COVID-19-associated multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C): a prospective observational study. Biomedicine. (2022) 10:2956. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10112956

45.

Fliser D Ritz E . Serum cystatin C concentration as a marker of renal dysfunction in the elderly. Am J Kidney Dis. (2001) 37:79–83. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.20628

Summary

Keywords

cystatin C, diabetes, diabetic retinopathy, T2DM, renal function

Citation

Gui Q, Jiang K and Xu Y (2025) Relationship between serum cystatin C and diabetic retinopathy in T2DM patients. Front. Med. 12:1725451. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1725451

Received

15 October 2025

Revised

02 November 2025

Accepted

04 November 2025

Published

17 November 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Livio Vitiello, Azienda Sanitaria Locale Salerno, Italy

Reviewed by

Ahmed Ezzat, Benha University, Egypt

Nadia AbdulKareem, Al Iraqia University College of Medicine, Iraq

Lamia Samir Ellaithy, National Research Centre (Egypt), Egypt

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Gui, Jiang and Xu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kunhua Jiang, houjiangzhuang@sina.com; Yuxin Xu, xuyuxin1168@sina.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.