Abstract

The granin gene family of neuropeptides functions as peptide neurotransmitters in the brain for the regulation of neural functions that regulate behaviors. Granins are involved in regulating cognition, memory, depression, aggression, stress, energy expenditure, inflammation, and related. Development of the human brain involves formation of synapses and their spectrum of neurotransmitters to establish neural connections that are required for brain functions. Therefore, the goal of this study was to analyze the gene expression profiles of the granin neurotransmitter genes during human brain development at prenatal, infancy, childhood, adolescence, and adult stages. Granin gene expression in brain development was assessed by quantitative RNA sequencing data from the Allen Human Brain Atlas resource. VGF (neurosecretory protein VGF) expression was significantly increased during development during the prenatal to childhood through adult stages in the anterior cingulate cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, inferolateral temporal cortex, orbital frontal cortex, posteroventral parietal cortex, primary somatosensory cortex, and primary visual cortex regions. SCG2 (secretogranin 2) expression was also significantly increased from prenatal to infancy through adult stages in anterior cingulate cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, inferolateral temporal cortex, orbital frontal cortex, posterior superior temporal cortex, posteroventral parietal cortex, primary somatosensory cortex, and primary visual cortex. A modest number of brain regions showed increased CHGA, CHGB, and SCG3 expression in the postnatal periods compared to the prenatal periods. Further, the SCG5, PCSK1N, and GNAS genes displayed minimal changes throughout development. Overall, these results demonstrate developmental upregulation of VGF and SCG2 genes, with lesser upregulation of CHGA, CHGB, and SCG3 genes, and almost no changes in SCG5, PCSK1N, and GNAS genes during development. These findings illustrate the differential regulation of granin genes during human brain development.

Introduction

The granin family of neuropeptides function as peptide neurotransmitters for cell–cell signaling in the brain that is essential for the regulation of brain functions, including memory, depression, aggression, stress, energy utilization, inflammation, and related. The granin gene family is composed of chromogranin A (CHGA), chromogranin B (CHGB), secretogranin II (SCG2, also known as chromogranin C), secretogranin III (SCG3, also known as 1B1075), secretogranin V (SCG5, also known as 7B2), and GNAS (SCG6, also known as secretogranin VI and NESP55), proSAAS (also known as PCSK1N), and VGF (also known as secretogranin VII) (Taupenot et al., 2003; Bartolomucci et al., 2011; Troger et al., 2017; Quinn et al., 2023; Weiss et al., 2000).

Granins are produced as neuropeptide precursor proteins that are routed to dense core secretory vesicles (DCSV) where such precursors undergo proteolytic processing to generate neuropeptides that are released to mediate cell–cell signaling in neurotransmission (Hook et al., 2018). The granins also facilitate DCSV biogenesis that is required for neuropeptide production (Bartolomucci et al., 2011). The secreted brain neuropeptides reach the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) where neuropeptides have been studied as biomarkers of brain health and neurological disease conditions (Higginbotham et al., 2020; Haque et al., 2023; Quinn et al., 2023).

Regulation of granin neuropeptides in brain disorders has been found to occur at diverse ages from young to adult years, shown by dysregulation of granins in schizophrenia (SZ) and traumatic brain injury (TBI) that occur at young through adult ages, and in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) that occur in older adults. In human SZ individuals, CHGB neuropeptides are reduced in brain hippocampus (Nowakowski et al., 2002); in SZ patient-derived induced neurons (iN) CHGB neuropeptides are reduced compared to control neurons (Podvin et al., 2024). In TBI mice, SCG2 was found to mediate blood–brain barrier dysfunction (Lin et al., 2024). In human AD brain and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), VGF and CHGA neuropeptides are downregulated and upregulated, respectively, compared to control brains (Higginbotham et al., 2020; Podvin et al., 2022; Quinn et al., 2023; Haque et al., 2023); moreover, reduced VGF neuropeptides correlate with cognitive impairment (Haque et al., 2023; Higginbotham et al., 2020). In PD subjects, granins were generally reduced in CSF (Rotunno et al., 2020).

Animal studies of granin gene knockout have demonstrated roles for granins in memory, depression, energy expenditure, tauopathy, angiogenesis, and related (Lin et al., 2015; Watson et al., 2009; Pereda et al., 2015; Jati et al., 2025; Dai et al., 2022). In AD animal models, VGF gene ablation impaired memory function (Lin et al., 2015), and knockout of the CHGA gene resulted in improved cognitive function and amelioration of tau neuropathology (Jati et al., 2025). VGF has been shown to regulate energy expenditure and fat storage in VGF gene knockout mice (Watson et al., 2009). Mice lacking the CHGB gene exhibit increased aggression and depressive behaviors (Pereda et al., 2015). Deletion of the SCG3 gene resulted in reduced severity of pathological angiogenesis in oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) (Dai et al., 2022).

Development of the human brain involves formation of the spectrum of granin neurotransmitters to establish neural signaling required for brain functions. The regulation of granins in brain disorders at young to adult ages raises the question of their developmental regulation of granin genes in human brain. Therefore, the goal of this study was to investigate the granin gene expression profiles in human brain development during the stages of the prenatal period to infancy, childhood, adolescence, and adult stages. Evaluation of granin gene expression in 16 human brain regions during development was achieved by analyzing quantitative Ref-seq data from the Allen Human Brain Atlas resource (Hawrylycz et al., 2012; Sunkin et al., 2013). Results illustrated differential upregulation of granin genes during human brain development, with VGF and SCG2 displaying the greatest prevalence of development upregulation among the brain regions studied.

Methods and procedures

Developmental expression of granin genes in human brain regions from the Allen human brain atlas resource

The Allen Human Brain Atlas resource for gene expression data (Hawrylycz et al., 2012; Sunkin et al., 2013) was utilized for analysis of granin gene expression levels during human brain development in 16 human brain regions during prenatal, infancy, childhood, adolescence, and young adult age periods. These data were achieved by the human brain development project of the Allen Brain Atlas that provides RNA sequencing data for quantitative gene expression of the 8 granin genes assessed in this study.

The Allen Human Brain Atlas collected postmortem human brain tissues at ages of early pre-natal, late prenatal, infancy, childhood, adolescence, and young adult. Ages for each developmental period is shown in Table 1. The brain tissue collection included males and females, with subjects having backgrounds of European, Asian, African American, Hispanic, and mixed cultures. The number of brain samples from each brain region, per developmental period, consisted of 4 to 12 samples from different subjects (males and females) that were determined by the Allen Human Brain Atlas program. It will be desirable in future studies to use large sample sizes per group and comparisons. Negative selection criteria included chromosomal abnormalities, maternal drug use, brain lesions, positive testing for hepatitis B or C, HIV, and neurological disorders.

Table 1

| Developmental stage | Age range | Number of brain samples |

|---|---|---|

| Early Prenatal | 8–18 weeks post-conception | 12 (7 males, 4 females) |

| Late Prenatal | 19–38 weeks post-conception | 8 (3 males, 5 females) |

| Infancy | 8–18 months | 5 (4 males, 1 female) |

| Childhood | 19 months to 11 years | 7 (4 males, 3 females) |

| Adolescence | 12–19 years | 4 (2 males, 2 females) |

| Young Adult | 20–40 years | 6 (3 males, 3 females) |

Developmental stages studied for granin gene expression in human brain.

The age ranges for each development stage are indicated. For each stage, 16 brain regions were assessed for granin gene expression levels.

Sixteen brain regions were analyzed, consisting of the amygdaloid complex, anterior cingulate cortex, cerebellar cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, inferolateral temporal cortex, mediodorsal nucleus of thalamus, orbital frontal cortex, posterior superior temporal cortex, posteroventral parietal cortex, primary auditory cortex, primary motor cortex, primary somatosensory cortex, primary visual cortex, striatum, and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex. Study of these brain regions was selected by the Allen Human Brain Atlas program because their development is essential for critical brain functions that include cognition, memory, executive function, language, motor movement, vision, emotion, social behavior, and olfaction (Table 2).

Table 2

| Brain Regions | Behavioral Functions | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognition | Memory | Executivefunction | Language | Motor | Vision | Emotion | Social behavior | Olfaction | References | |

| (a) Amygdaloid complex | Phelps and LeDoux (2005); Šimić et al. (2021) | |||||||||

| (b) Anterior Cingulate Cortex | Etkin et al. (2011); Shackman et al. (2011) | |||||||||

| (c) Cerebellar Cortex | Kandel et al. (1991) | |||||||||

| (d) Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex | Kandel et al. (1991); Miller and Cohen (2001) | |||||||||

| (e) Hippocampus | Lisman et al. (2018); Moscovitch et al. (2016) | |||||||||

| (f) Inferolateral Temporal Cortex | Patterson et al. (2007); Robinson and Rolls (2015) | |||||||||

| (g) Mediodorsal Nucleus of Thalamus | Wolff and Halassa (2024); Kandel et al. (1991) | |||||||||

| (h) Orbital Frontal Cortex | Rolls (2023) | |||||||||

| (i) Posterior Superior Temporal Cortex | Redcay (2008); Kandel et al. (1991) | |||||||||

| (j) Posteroventral Parietal Cortex | Squire et al. (2003); Sokolowski et al. (2023) | |||||||||

| (k) Primary Auditory Cortex | Squire et al. (2003); Weinberger (2015) | |||||||||

| (l) Primary Motor Cortex | Schieber (2001); Squire et al. (2003) | |||||||||

| (m) Primary Somato-sensory Cortex | Squire et al. (2003) Kandel et al. (1991) | |||||||||

| (n) Primary Visual Cortex | Boynton (2005); Kandel et al. (1991) | |||||||||

| (o) Striatum | Squire et al. (2003); O'Doherty (2004) | |||||||||

| (p) Ventrolateral Prefrontal Cortex | Badre and Wagner (2006); Blumenfeld and Ranganath (2007) | |||||||||

Behavioral functions of human brain regions investigated for granin gene expression.

Gene expression data were acquired by RNA-Seq analyses for the 16 brain regions, as described by the Allen Human Brain Atlas resource (Shen et al., 2012). Briefly, tissues were subjected to RNA extraction and polyA+ RNA was isolated using polyT-RNA magnetic beads. The purified polyA+ RNAs were quantitated and spike-in RNA mixes were added to normalize gene expression across samples. The polyA+ RNA was subjected to cDNA synthesis using reverse transcriptase and DNA polymerase I, combined with adenylation at 3′-ends, for DNA sequencing by the Illumina Genome Analyzer Iix. RNA-Seq data provided gene expression data expressed as RPKM, reads per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads. This RNA-Seq data was obtained from the Allen Brain Atlas resource1 for gene expression analysis of granin genes.

The average gene expression level for each granin gene (in units of RPKM) was calculated for the six developmental periods. In addition, the total granin gene expression, sum of the 8 granin genes, was calculated for each developmental period as the mean +/- standard error of the mean (s.e.m). Statistical analyses utilized the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test, the Dunn’s multiple comparison post hoc test, and two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc multiple comparisons test using GraphPad Prism. Statistical significance was assessed as p < 0.05.

Results

Strategy for granin gene expression analysis in human brain development by RNA-seq analyses

The granin genes of VGF, CHGA, CHGB, SCG2, SCG3, SCG5, PCSK1N (proSAAS), and GNAS encode proneuropeptide precursors that are converted to small neuropeptide transmitters by proteolysis (Figure 1). These granin genes are important for essential brain functions that include cognition, memory, executive function, language, movement, vision, emotion, social behavior, and olfaction (Table 2).

Figure 1

Granin genes encode neuropeptide transmitter precursor proteins. Granin gene expression in human brain during development to adult was conducted for the VGF, CHGA, SCG2, SCG3, SCG5, PCSK1N (proSAAS), and GNAS (NESP55) genes by RNA-seq analyses by the Allen Human Brain Atlas resource (Hawrylycz et al., 2012; Sunkin et al., 2013). Each granin gene encodes a neuropeptide precursor protein that undergoes proteolytic processing to generate small neuropeptide transmitters. Examples of neuropeptides generated from each translated granin protein are illustrated.

The expression levels of the granin genes VGF, CHGA, CHGB, SCG2, SCG3, SCG5, PCSK1N (proSAAS), and GNAS (Supplementary Table S1) in human brain were assessed during development from prenatal, to infancy, childhood, adolescence, and adult stages (Table 1) by RNA-seq analysis of 16 human brain regions (Figure 2). The data provided an extensive assessment of the 8 granin genes during development of the human brain.

Figure 2

RNA-Seq expression analyses of granin genes in human brain. Expression of the VGF, CHGA, CHGB, SCG2, SCG3, SCG5, PCSK1N (proSAAS), and GNAS (NESP55) genes were assessed by RNA-Seq analysis of 16 brain regions during developmental periods of prenatal, infancy, childhood, adolescence, and young adult stages. RNA-Seq data was obtained from the open resource program of the Allen Human Brain Atlas. Gene expression was quantitated as RPKM (reads per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads).

Total granin gene expression levels during development in human brain regions

Total granin gene expression was evaluated as the sum of each of the granin gene expression levels for six developmental stages from prenatal to infancy, childhood, adolescence, and young adult (Figure 3). The 16 human brain regions studied consisted of the amygdaloid complex, anterior cingulate cortex, cerebellar cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, inferolateral temporal cortex, mediodorsal nucleus of thalamus, orbital frontal cortex, posterior superior temporal cortex, posteroventral parietal cortex, primary auditory cortex, primary motor cortex, primary somatosensory cortex, primary visual cortex, striatum, and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex.

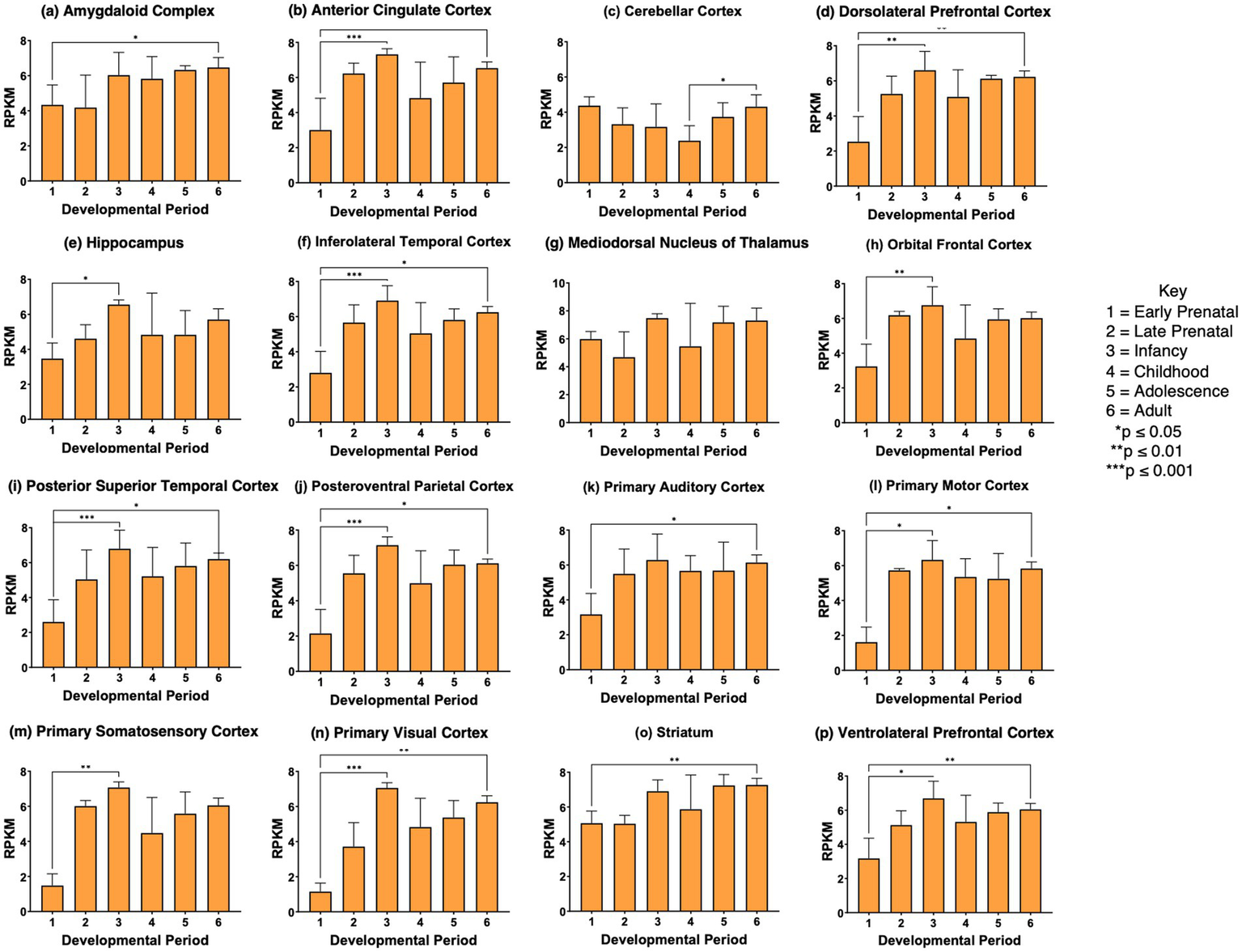

Figure 3

Total expression of granin genes during development in human brain. Total granin expression is expressed as the sum of the quantitative expression values for the 8 granin genes which are displayed as a portion of the total, with each granin expression level shown in a color-coded manner. Granin expression is indicated as RPKM in the 16 brain regions, consisting of (a) amygdaloid complex, (b) anterior cingulate cortex, (c) cerebellar cortex, (d) dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, (e) hippocampus, (f) inferolateral temporal cortex, (g) mediodorsal nucleus of thalamus, (h) orbital frontal cortex, (i) posterior superior temporal cortex, (j) posteroventral parietal cortex, (k) primary auditory cortex, (l) primary motor cortex, (m) primary somatosensory cortex, (n) primary visual cortex, (o) striatum, and (p) ventrolateral prefrontal cortex. Six development periods were studied consisting of (1) early prenatal, (2) late prenatal, (3) infancy, (4) childhood, (5) adolescence, and (6) young adult (shown as stages #1-6). Bar graphs show the total granin gene expression values as the average RPKM +/- s.e.m., with statistical significance (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001) assessed by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc multiple comparisons test.

The majority of the brain regions (14 regions shown in panels a-b, d-n, and p of Figure 3) displayed significant differences in total granin expression among the developmental stages from prenatal through young adult stages. A similar feature among these 14 brain regions was the finding that total granin expression increased from prenatal (early and late prenatal) to infancy stages, followed by a drop at the childhood compared to the infant stage, and then an increase was observed from childhood to adolescence and adult stages. These data suggest that increased granin gene expression from prenatal to infancy may represent the functional importance of these secretory vesicle proteins in brain development. Moreover, a second phase of increased total granin expression during childhood to adolescence to young adult stages (for brain regions shown in panels b, d, e-j, m, n, and p of Figure 3) may reflect involvement of granins in these regions for development during childhood to young adult.

However, two brain regions, striatum and cerebellar cortex, showed minimal changes in total granin expression during development. The striatum (panel o, Figure 3) displayed small differences in total granin expression at the early prenatal compared to infancy stage, and infancy compared to childhood and adolescent stages. The cerebellar cortex (panel c, Figure 3) showed no changes in total granin expression among the developmental stages.

These data also show that expression of the granin genes is maintained throughout development in the 16 human brain regions studied.

Relative expression of each granin gene during development

To evaluate the relative expression levels of each of the granins among the 16 brain regions at the 6 developmental stages, the percent of total granin expression was calculated for each granin and summarized (Table 3) based on detailed expression data in the brain regions among the developmental periods (Supplementary Table S1). The 8 granin genes each showed 3–20% levels of expression of the total granin expression levels. VGF, CHGA, and SCG2 genes displayed expression levels of 3–4 to 12–17% of total granins. Compared to all granins, VGF, CHGA, and SCG2 showed the lowest level of expression in several brain regions, including primary motor cortex and primary somatosensory cortex. CHGB and SCG3 showed a range of expression of 9–20% of total granins; CHGB showed the highest level of expression in cerebellar cortex at the childhood to young adult stages. SCG5, proSAAS, and GNAS displayed expression at 12–19% of total granins; high level expression of these granins occurred mainly in the prenatal stage. These data show the ranges of granins expressed during development among multiple brain regions.

Table 3

| Granin gene | Range of expression during development in 16 human brain regions |

|---|---|

| VGF | 4–12% |

| CHGA | 3–14% |

| CHGB | 9–20% |

| SCG2 | 3–17% |

| SCG3 | 10–17% |

| SCG5 | 12–17% |

| PCSK1N (proSAAS) | 13–18% |

| GNAS (NESP55) | 12–19% |

Ranges of granin gene expression during human brain development.

The range of expression values for each granin gene, among the 16 brain regions in 6 developmental periods (Supplementary Table S1) is shown as the percent of total granin gene expression.

Regulation of VGF, SCG2, and CHGA gene expression during development in human brain

The expression levels of the VGF, SCG2, and CHGA genes were each assessed for developmental regulation in the 16 brain regions. Significant regulation of these granin genes was observed during development.

VGF gene expression was significantly regulated during development in 12 of the 16 brain regions examined, shown in panels a-b, d-f, h-j, l-n, and p of Figure 4. VGF in these brain regions showed significant increases from the prenatal phase to the infancy stage. While this increase was observed in the primary auditory cortex, the values did not reach significance. During the stages of childhood to adolescence and young adult, no significant increase in VGF expression was observed. The young adult stage showed higher VGF expression than the prenatal stage in most brain regions (panels a, b, d, f, h-n, and p of Figure 4). These data demonstrate significant regulation of VGF during prenatal to infancy stages among the majority of brain regions studied.

Figure 4

VGF gene expression during development in human brain. Expression levels of the VGF gene in 16 brain regions are shown for (a) amygdaloid complex, (b) anterior cingulate cortex, (c) cerebellar cortex, (d) dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, (e) hippocampus, (f) inferolateral temporal cortex, (g) mediodorsal nucleus of thalamus, (h) orbital frontal cortex, (i) posterior superior temporal cortex, (j) posteroventral parietal cortex, (k) primary auditory cortex, (l) primary motor cortex, (m) primary somatosensory cortex, (n) primary visual cortex, (o) striatum, and (p) ventrolateral prefrontal cortex. Six development periods were studied consisting of (1) early prenatal, (2) late prenatal, (3) infancy, (4) childhood, (5) adolescence, and (6) young adult. Graphs show the average RPKM +/- s.e.m. for VGF expression, with statistical significance of (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001) assessed by Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison post hoc test.

SCG2 gene expression was significantly elevated during development from prenatal to infancy stages in 11 of the 16 regions (panels b, d, e, f, h-j, l, m, n, p of Figure 5). SCG2 showed higher expression at the young adult stage compared to the prenatal stage for 11 brain regions shown in panels a, b, d, f, i-l, m, n-p of Figure 5. These data show that in several brain regions, SCG2 expression increases from prenatal to infancy stages, as found for VGF in numerous brain regions. The increase in SCG2 expression at the young adult compared to the prenatal stage differs from VGF or CHGA changes during brain development.

Figure 5

SCG2 gene expression during development in human brain. Expression levels of the SCG2 gene in 16 brain regions are shown for (a) amygdaloid complex, (b) anterior cingulate cortex, (c) cerebellar cortex, (d) dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, (e) hippocampus, (f) inferolateral temporal cortex, (g) mediodorsal nucleus of thalamus, (h) orbital frontal cortex, (i) posterior superior temporal cortex, (j) posteroventral parietal cortex, (k) primary auditory cortex, (l) primary motor cortex, (m) primary somatosensory cortex, (n) primary visual cortex, (o) striatum, and (p) ventrolateral prefrontal cortex. Six development periods were studied consisting of (1) early prenatal, (2) late prenatal, (3) infancy, (4) childhood, (5) adolescence, and (6) young adult. Graphs show the average RPKM +/- s.e.m. for SCG2 expression, with statistical significance of (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001) assessed by Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison post hoc test.

CHGA gene expression showed significant increases in CHGA expression at the adolescence or young adult stages compared to the prenatal stages in several brain regions (panels d, h, i, k-n, and p of Figure 6). Also, cerebellar cortex CHGA expression at the prenatal stages (early and late prenatal) became decreased in the childhood stage by more than 75%; this decrease was not observed in other brain regions. These data show differences in the regulation of CHGA compared to VGF and SCG2 expression during development in human brain.

Figure 6

CHGA gene expression during development in human brain. Expression levels of the CHGA gene in 16 brain regions are shown for (a) amygdaloid complex, (b) anterior cingulate cortex, (c) cerebellar cortex, (d) dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, (e) hippocampus, (f) inferolateral temporal cortex, (g) mediodorsal nucleus of thalamus, (h) orbital frontal cortex, (i) posterior superior temporal cortex, (j) posteroventral parietal cortex, (k) primary auditory cortex, (l) primary motor cortex, (m) primary somatosensory cortex, (n) primary visual cortex, (o) striatum, and (p) ventrolateral prefrontal cortex. Six development periods were studied consisting of (1) early prenatal, (2) late prenatal, (3) infancy, (4) childhood, (5) adolescence, and (6) young adult. Graphs show the average RPKM +/- s.e.m. for SCG2 expression, with statistical significance of (*p<0.05 and **p<0.01) assessed by Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison post hoc test.

Modest regulation of CHGB and SCG3 genes, and minimal changes in SCG5, PCSK1N, and GNAS granin genes during brain development

The CHGB and SCG3 genes showed modest upregulation in several brain regions comparing prenatal to postnatal stages of infancy, childhood, adolescence, and adult (Figures 7 and 8). However, the SCG5, proSAAS, and GNAS genes showed essentially no regulation during development (Supplementary Figures S1–S3). These findings indicate differential regulation of granin genes in human brain during development.

Figure 7

CHGB gene expression during development in human brain. Expression levels of the CHGB gene in 16 brain regions are shown for (a) amygdaloid complex, (b) anterior cingulate cortex, (c) cerebellar cortex, (d) dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, (e) hippocampus, (f) inferolateral temporal cortex, (g) mediodorsal nucleus of thalamus, (h) orbital frontal cortex, (i) posterior superior temporal cortex, (j) posteroventral parietal cortex, (k) primary auditory cortex, (l) primary motor cortex, (m) primary somatosensory cortex, (n) primary visual cortex, (o) striatum, and (p) ventrolateral prefrontal cortex. Six development periods were studied consisting of (1) early prenatal, (2) late prenatal, (3) infancy, (4) childhood, (5) adolescence, and (6) young adult. Graphs show the average RPKM +/- s.e.m. for CHGB expression, with statistical significance of (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001) assessed by Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison post hoc test.

Figure 8

SCG3 gene expression during development in human brain. Expression levels of the SCG3 gene in 16 brain regions are shown for (a) amygdaloid complex, (b) anterior cingulate cortex, (c) cerebellar cortex, (d) dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, (e) hippocampus, (f) inferolateral temporal cortex, (g) mediodorsal nucleus of thalamus, (h) orbital frontal cortex, (i) posterior superior temporal cortex, (j) posteroventral parietal cortex, (k) primary auditory cortex, (l) primary motor cortex, (m) primary somatosensory cortex, (n) primary visual cortex, (o) striatum, and (p) ventrolateral prefrontal cortex. Six development periods were studied consisting of (1) early prenatal, (2) late prenatal, (3) infancy, (4) childhood, (5) adolescence, and (6) young adult. Graphs show the average RPKM +/- s.e.m. for SCG3 expression, with statistical significance of (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001) assessed by Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison post hoc test.

Overall findings: differential upregulation of VGF, SCG2, CHGA, CHGB, and SCG3 granin genes during human brain development

A schematic illustration (Figure 9A) shows the relative prevalence of significant upregulation of the VGF, SCG2, CHGA, CHGB, and SCG3 granin genes in 16 brain regions during transition from prenatal to postnatal periods of infancy, childhood, adolescence, and adult. The relative upregulation of these granin genes was calculated based on the number of significant paired comparisons of upregulation from the prenatal periods to the postnatal periods (Figure 9B). In contrast, the other granin genes of SCG5, PCSK1N, and GNAS showed almost no developmental regulation. VGF and SCG2 genes displayed the greatest prevalence of upregulation in human brain during development.

Figure 9

Summary of differential upregulation of VGF, SCG2, CHGA, CHGB, and SCG3 granin genes during human brain development. The relative upregulation of these granin genes is illustrated by the size of the gene name (a) based on the number of significant comparisons of upregulation from the prenatal periods to the postnatal periods (b). VGF, SCG2, CHGA, CHGB, and SCG3 showed significant upregulation during development in human brain (a). In contrast, the other granin genes of SCG5, PCSK1N, and GNAS showed almost no developmental regulation (b).

Discussion

The granin genes participate in brain cell–cell signaling as neuropeptide transmitters that are essential for brain functions. The goal of this study was to assess the hypothesis that expression of granin genes in human brain is regulated during the developmental stages of prenatal to infancy, childhood, adolescence, and adult. The expression of VGF was significantly increased from the prenatal to infancy stages in the anterior cingulate cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, inferolateral temporal cortex, orbital frontal cortex, posteroventral parietal cortex, primary somatosensory cortex, and primary visual cortex. SCG2 expression was also significantly increased from the prenatal to infancy stages, observed in the anterior cingulate cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, inferolateral temporal cortex, orbital frontal cortex, posterior superior temporal cortex, posteroventral parietal cortex, primary somatosensory cortex, and primary visual cortex. CHGA expression was more abundant at the young adult age compared to the prenatal stage. CHGB and SCG3 displayed minor changes in gene expression levels during development. The other SCG5, PCSK1N, and GNAS genes showed primarily no changes in expression during development of the human brain in the 16 regions studied. The overall relative upregulation of VGF, SCG2, with lesser upregulation of CHGA, CHGB, and SCG3, is schematically shown in Figure 9. These findings demonstrate that VGF and SCG2 display the greatest extent of upregulation among the granin genes from prenatal to postnatal to adult stages of development.

This study utilized the Allen Human Brain Atlas resource that provides expression data for all human genes in brain (Shen et al., 2012). The data are provided as an open resource to investigators. The developmental expression data, for prenatal to young adult stages, was obtained by RNA-seq analysis for 16 brain regions.

The rationale for investigating granin gene expression regulation during development is based on the important functions of granins in neuronal cell–cell signaling required for brain functions and behaviors. Animal studies of granin gene knockout have demonstrated roles for granins in memory, depression, energy expenditure, tauopathy, angiogenesis, and related (Lin et al., 2015; Watson et al., 2009; Pereda et al., 2015; Jati et al., 2025; Dai et al., 2022). Expression of granins provides diverse neuropeptide transmitters generated from the granin proteins by proteolytic processing, which provides a multitude of diverse neuropeptides. It is estimated that hundreds to thousands of neuropeptides are present in the brain, with novel neuropeptides being discovered in the field with advanced mass spectrometry technology (Hook and Bandeira, 2015; Romanova and Sweedler, 2015; Delaney and Li, 2019; Sauer et al., 2021; Anapindi et al., 2022; Fields et al., 2024).

The hypothesis for the regulation of granin genes during development in human brain regions has been addressed by this study. Results show that expression of selected granin genes are regulated during development from prenatal and infancy stages to childhood, adolescence, and adult periods. Furthermore, the regulation of granin expression occurs in specific brain regions. It will be important to assess the developmental neuropeptides and their biological functions that result from granin gene expression regulation in the multitude of human brain regions from young to adult and older ages.

Human brain disorders display dysregulated granin neuropeptides that include Alzheimer’s disease (Higginbotham et al., 2020; Podvin et al., 2022; Quinn et al., 2023; Haque et al., 2023), Parkinson’s disease (Rotunno et al., 2020), schizophrenia (Takahashi et al., 2006; Podvin et al., 2024), and other neurological and psychiatric disease conditions. It will be important to define the spectrum of regulated neuropeptides participating in human brain diseases to identify novel neuropeptide biomarkers and candidate targets for therapeutics discovery.

Of particular interest is expression of the VGF granin which was found by this study to display the largest degree of upregulation compared to the other granin genes during development of the human brain. In Alzheimer’s disease (AD) brain, significant decreases in VGF neuropeptides in the CSF (cerebrospinal fluid) have been found to be associated with cognitive decline (Haque et al., 2023). Furthermore, VGF neuropeptides are dysregulated in in AD brain along with other granin neuropeptides (Higginbotham et al., 2020; Podvin et al., 2022; Quinn et al., 2023; Haque et al., 2023). Overexpression of VGF has been shown to result in improved cognitive function (Lin et al., 2021). It will be important to investigate the functions of regulated VGF neuropeptides in AD.

The results of this study provide new insight into the developmental upregulation of the granin genes VGF, SCG2, CHGA, CHGB, and SCG3 during human brain development from prenatal to post-natal periods of infancy, childhood, adolescence, and adult. These data utilized gene expression data of the Allen Human Brain Atlas program that selected the samples from 16 brain regions from 6 developmental periods (Table 1). The numbers of samples per group varied from 4 to 12 samples that included males and females. A limitation of these data are the low numbers of samples per group. It will be beneficial in future studies to utilizes larger group sizes for evaluation of the significant developmental regulation of granin genes in human brain.

In conclusion, this investigation of the developmental regulation of granin genes in human brain demonstrated selected changes in expression of granins during prenatal to infancy and childhood stages, as well as development from childhood to adolescence and adult stages. Granin expression occurs throughout the brain at all stages of development. These findings provide a fundamental understanding of granin gene expression during human brain development that is essential for brain functions and behaviors throughout the decades of life.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human tissues were approved by institutional review board of the Allen Institute. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

LD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SP: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Software. VH: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by NIH grants R01NS109075 and RF1AG095193 awarded to VH for research on brain mechanisms of neuropeptide transmitters, including granins related to brain disorders.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Allen Human Brain Atlas for providing the gene expression data as a public resource.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnmol.2025.1666795/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

1

Anapindi K. D. B. Romanova E. V. Checco J. W. Sweedler J. V. (2022). Mass spectrometry approaches empowering neuropeptide discovery and therapeutics. Pharmacol. Rev.74, 662–679. doi: 10.1124/pharmrev.121.000423,

2

Badre D. Wagner A. D. (2006). Computational and neurobiological mechanisms underlying cognitive flexibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA103, 7186–7191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509550103,

3

Bartolomucci A. Possenti R. Mahata S. K. Fischer-Colbrie R. Loh Y. P. Salton S. R. (2011). The extended granin family: structure, function, and biomedical implications. Endocr. Rev.32, 755–797. doi: 10.1210/er.2010-0027,

4

Blumenfeld R. S. Ranganath C. (2007). Prefrontal cortex and long-term memory encoding: an integrative review of findings from neuropsychology and neuroimaging. Neuroscientist13, 280–291. doi: 10.1177/1073858407299290,

5

Boynton G. M. (2005). Imaging orientation selectivity: decoding conscious perception in V1. Nat. Neurosci.8, 541–542. doi: 10.1038/nn0505-541,

6

Dai C. Waduge P. Ji L. Huang C. He Y. Tian H. et al . (2022). Secretogranin III stringently regulates pathological but not physiological angiogenesis in oxygen-induced retinopathy. Cell. Mol. Life Sci.79:63. doi: 10.1007/s00018-021-04111-2,

7

DeLaney K. Li L. (2019). Data independent acquisition mass spectrometry method for improved Neuropeptidomic coverage in crustacean neural tissue extracts. Anal. Chem.91, 5150–5158. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b05734,

8

Etkin A. Egner T. Kalisch R. (2011). Emotional processing in anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex. Trends Cogn. Sci.15, 85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.11.004,

9

Fields L. Vu N. Q. Dang T. C. Yen H. C. Ma M. Wu W. et al . (2024). EndoGenius: optimized neuropeptide identification from mass spectrometry datasets. J. Proteome Res.23, 3041–3051. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.3c00758,

10

Haque R. Watson C. M. Liu J. Carter E. K. Duong D. M. Lah J. J. et al . (2023). A protein panel in cerebrospinal fluid for diagnostic and predictive assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Sci. Transl. Med.15:eadg4122. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adg4122,

11

Hawrylycz M. J. Lein E. S. Guillozet-Bongaarts A. L. Shen E. H. Ng L. Miller J. A. et al . (2012). An anatomically comprehensive atlas of the adult human brain transcriptome. Nature489, 391–399. doi: 10.1038/nature11405,

12

Higginbotham L. Ping L. Dammer E. B. Duong D. M. Zhou M. Gearing M. et al . (2020). Integrated proteomics reveals brain-based cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in asymptomatic and symptomatic Alzheimer's disease. Sci. Adv.6:eaaz9360. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz9360,

13

Hook V. Bandeira N. (2015). Neuropeptidomics mass spectrometry reveals signaling networks generated by distinct protease pathways in human systems. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom.26, 1970–1980. doi: 10.1007/s13361-015-1251-6,

14

Hook V. Lietz C. B. Podvin S. Cajka T. Fiehn O. (2018). Diversity of neuropeptide cell-cell signaling molecules generated by proteolytic processing revealed by Neuropeptidomics mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom.29, 807–816. doi: 10.1007/s13361-018-1914-1,

15

Jati S. Munoz-Mayorga D. Shahabi S. Tang K. Tao Y. Dickson D. W. et al . (2025). Chromogranin a deficiency attenuates tauopathy by altering epinephrine-alpha-adrenergic receptor signaling in PS19 mice. Nat. Commun.16:4703. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-59682-6,

16

Kandel E. R. Schwartz J. H. Jessell T. M. (1991). Principles of neural science. 4th Edn. New York: McGraw-Hill.

17

Lin W. J. Jiang C. Sadahiro M. Bozdagi O. Vulchanova L. Alberini C. M. et al . (2015). VGF and its C-terminal peptide TLQP-62 regulate memory formation in Hippocampus via a BDNF-TrkB-dependent mechanism. J. Neurosci.35, 10343–10356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0584-15.2015,

18

Lin W. J. Zhao Y. Li Z. Zheng S. Zou J. L. Warren N. A. et al . (2021). An increase in VGF expression through a rapid, transcription-independent, autofeedback mechanism improves cognitive function. Transl. Psychiatry11:383. doi: 10.1038/s41398-021-01489-2,

19

Lin C. Zhao P. Sun G. Liu N. Ji J. (2024). SCG2 mediates blood-brain barrier dysfunction and schizophrenia-like behaviors after traumatic brain injury. FASEB J.38:e70016. doi: 10.1096/fj.202401117R,

20

Lisman J. Buzsáki G. Eichenbaum H. Nadel L. Ranganath C. Redish A. D. (2018). Viewpoints: how the hippocampus contributes to memory, navigation and cognition. Nat. Neurosci.20, 1434–1447. doi: 10.1038/nn.4661

21

Miller E. K. Cohen J. D. (2001). An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci.24, 167–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167,

22

Moscovitch M. Cabeza R. Winocur G. Nadel L. (2016). Episodic memory and beyond: the Hippocampus and neocortex in transformation. Annu. Rev. Psychol.67, 105–134. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143733,

23

Nowakowski C. Kaufmann W. A. Adlassnig C. Maier H. Salimi K. Jellinger K. A. et al . (2002). Reduction of chromogranin B-like immunoreactivity in distinct subregions of the hippocampus from individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res.58, 43–53. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(01)00389-9,

24

O'Doherty J. P. (2004). Reward representations and reward-related learning in the human brain: insights from neuroimaging. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol.14, 769–776. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.10.016,

25

Patterson K. Nestor P. J. Rogers T. T. (2007). Where do you know what you know? The representation of semantic knowledge in the human brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.8, 976–987. doi: 10.1038/nrn2277,

26

Pereda D. Pardo M. R. Morales Y. Dominguez N. Arnau M. R. Borges R. (2015). Mice lacking chromogranins exhibit increased aggressive and depression-like behaviour. Behav. Brain Res.278, 98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.09.022,

27

Phelps E. A. LeDoux J. E. (2005). Contributions of the amygdala to emotion processing: from animal models to human behavior. Neuron48, 175–187. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.025,

28

Podvin S. Jiang Z. Boyarko B. Rossitto L. A. O'Donoghue A. Rissman R. A. et al . (2022). Dysregulation of neuropeptide and tau peptide signatures in human Alzheimer's disease brain. ACS Chem. Neurosci.13, 1992–2005. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.2c00222,

29

Podvin S. Jones J. Kang A. Goodman R. Reed P. Lietz C. B. et al . (2024). Human in neuronal model of schizophrenia displays dysregulation of chromogranin B and related neuropeptide transmitter signatures. Mol. Psychiatry29, 1440–1449. doi: 10.1038/s41380-024-02422-x,

30

Quinn J. P. Ethier E. C. Novielli A. Malone A. Ramirez C. E. Salloum L. et al . (2023). Cerebrospinal fluid and brain Proteoforms of the Granin neuropeptide family in Alzheimer's disease. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom.34, 649–667. doi: 10.1021/jasms.2c00341,

31

Redcay E. (2008). The superior temporal sulcus performs a common function for social and speech perception: implications for the emergence of autism. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.32, 123–142. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.06.004,

32

Robinson L. Rolls E. T. (2015). Invariant visual object recognition: biologically plausible approaches. Biol. Cybern.109, 505–535. doi: 10.1007/s00422-015-0658-2,

33

Rolls E. T. (2023). Emotion, motivation, decision-making, the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and the amygdala. Brain Struct. Funct.228, 1201–1257. doi: 10.1007/s00429-023-02644-9,

34

Romanova E. V. Sweedler J. V. (2015). Peptidomics for the discovery and characterization of neuropeptides and hormones. Trends Pharmacol. Sci.36, 579–586. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2015.05.009,

35

Rotunno M. S. Lane M. Zhang W. Wolf P. Oliva P. Viel C. et al . (2020). Cerebrospinal fluid proteomics implicates the granin family in Parkinson's disease. Sci. Rep.10:2479. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-59414-4,

36

Sauer C. S. Phetsanthad A. Riusech O. L. Li L. (2021). Developing mass spectrometry for the quantitative analysis of neuropeptides. Expert Rev. Proteomics18, 607–621. doi: 10.1080/14789450.2021.1967146,

37

Schieber M. H. (2001). Constraints on somatotopic organization in the primary motor cortex. J. Neurophysiol.86, 2125–2143. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.5.2125,

38

Shackman A. J. Salomons T. V. Slagter H. A. Fox A. S. Winter J. J. Davidson R. J. (2011). The integration of negative affect, pain and cognitive control in the cingulate cortex. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.12, 154–167. doi: 10.1038/nrn2994,

39

Shen E. H. Overly C. C. Jones A. R. (2012). The Allen human brain atlas: comprehensive gene expression mapping of the human brain. Trends Neurosci.35, 711–714. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.09.005,

40

Šimić G. Tkalčić M. Vukić V. Mulc D. Španić E. Šagud M. et al . (2021). Understanding emotions: origins and roles of the amygdala. Biomolecules11:823. doi: 10.3390/biom11060823,

41

Sokolowski H. M. Matejko A. A. Ansari D. (2023). The role of the angular gyrus in arithmetic processing: a literature review. Brain Struct. Funct.228, 293–304. doi: 10.1007/s00429-022-02594-8,

42

Squire L. R. Bloom F. E. McConnell S. K. Roberts J. L. Spitzer N. C. Zigmond M. J. (2003). Fundamental Neuroscience. 2nd Edn. San Diego: Academic Press.

43

Sunkin S. M. Ng L. Lau C. Dolbeare T. Gilbert T. L. Thompson C. L. et al . (2013). Allen brain atlas: an integrated spatio-temporal portal for exploring the central nervous system. Nucleic Acids Res.41, D996–D1008. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1042,

44

Takahashi N. Ishihara R. Saito S. Maemo N. Aoyama N. Ji X. et al . (2006). Association between chromogranin a gene polymorphism and schizophrenia in the Japanese population. Schizophr. Res.83, 179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.12.854,

45

Taupenot L. Harper K. L. O'Connor D. T. (2003). The chromogranin-secretogranin family. N. Engl. J. Med.348, 1134–1149. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021405,

46

Troger J. Theurl M. Kirchmair R. Pasqua T. Tota B. Angelone T. et al . (2017). Granin-derived peptides. Prog. Neurobiol.154, 37–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2017.04.003,

47

Watson E. Fargali S. Okamoto H. Sadahiro M. Gordon R. E. Chakraborty T. et al . (2009). Analysis of knockout mice suggests a role for VGF in the control of fat storage and energy expenditure. BMC Physiol.9:19. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-9-19,

48

Weinberger N. M. (2015). New perspectives on the auditory cortex: learning and memory. Handb. Clin. Neurol.129, 117–147. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-62630-1.00007-X

49

Weiss U. Ischia R. Eder S. Lovisetti-Scamihorn P. Bauer R. Fischer-Colbrie R. (2000). Neuroendocrine secretory protein 55 (NESP55): alternative splicing onto transcripts of the GNAS gene and posttranslational processing of a maternally expressed protein. Neuroendocrinology71, 177–186. doi: 10.1159/000054535,

50

Wolff M. Halassa M. M. (2024). The mediodorsal thalamus in executive control. Neuron112, 893–908. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2024.01.002,

Summary

Keywords

granins, neuropeptides, neurotransmitters, genes, human brain, development, VGF, CHGA

Citation

Demsey LL, Podvin S and Hook V (2025) Regulation of granin neuropeptide gene expression in human brain during development. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 18:1666795. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2025.1666795

Received

15 July 2025

Accepted

08 October 2025

Published

02 December 2025

Volume

18 - 2025

Edited by

Ivano Condò, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Italy

Reviewed by

Natasha Yefimenko, University of Barcelona, Spain

Norma Angélica Moy López, University of Colima, Mexico

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Demsey, Podvin and Hook.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vivian Hook, vhook@ucsd.edu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.