- 1Department of Biomedical Engineering, Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, NJ, United States

- 2Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, NJ, United States

Purpose: To investigate the potential protective effects of taurine supplementation against retinal degeneration in an animal model of mild dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

Methods: To test the effects of a taurine supplement in mild dry AMD, sodium iodate (NaIO3)-induced retinal degeneration model was used. Two administration methods, intraperitoneal (IP) and intravenous (IV), were used to deliver NaIO3 in pigmented Long Evans rats to generate mild and severe dry AMD, respectively. Structural abnormalities were evaluated in vivo using near-infrared (IR) reflectance fundus imaging and optical coherence tomography (OCT). Using the slow progressive mild AMD model, we investigated the neuroprotective effects of oral taurine supplementation (1.5% w/v in drinking water) against NaIO3-induced retinal degeneration over 20 weeks. In addition, a human Retinal Pigment Epithelium (RPE, hTERT-RPE1) cell culture model was used to directly assess taurine’s ability to protect against NaIO3-related oxidative stress.

Results: The high-dose IV model (80 mg/kg) exhibited extensive and severe retinal damage, with ONL thinning by 64.2% and total retinal thickness (TRT) by 47.6%, predominantly in the peripapillary region. In contrast, the lower-dose IP model (50 mg/kg) displayed milder, more gradual deterioration (outer nuclear layer (ONL) thinning by 19.4% and TRT by 11.5%). Oral taurine supplementation significantly preserved ONL and TRT in vivo and supported RPE-1 cell survival, proliferation, and motility, under NaIO3 conditions.

Conclusion: Taurine supplementation provided significant structural protection against NaIO3-induced damage both in vivo and in cell culture, demonstrating its potential as a therapeutic candidate for mitigating mild dry AMD progression.

1 Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is one of the leading causes of irreversible vision loss in the aging population worldwide. As of 2020, it was estimated to affect nearly 200 million individuals, with prevalence projected to rise to approximately 288 million by 2040 (1, 2). AMD is categorized into two forms: wet and dry AMD. The wet form, also called neovascular form, is characterized by choroidal neovascularization. The non-neovascular dry form is marked by progressive degeneration of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and photoreceptors (3, 4). The dry form is significantly more prevalent, accounting for approximately 85 – 90% of all AMD cases (5). Despite its high prevalence, therapeutic options for dry AMD remain limited. The Age-Related Eye Disease Studies (AREDS and AREDS2) have demonstrated that dietary supplementation with specific antioxidants such as vitamins C and E, zinc, lutein, and zeaxanthin can delay progression from intermediate to advanced stages of AMD (6). Recently, intravitreal therapies targeting the complement cascade, such as pegcetacoplan (a C3 inhibitor) and avacincaptad pegol (a C5 inhibitor), have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of geographic atrophy (GA), the late stage of dry AMD (7, 8). While these agents slow lesion growth by up to 20% in a dose-dependent manner, they do not restore visual function and require frequent administration (9). To date, there is no effective treatment available to prevent or reverse early-stage dry AMD. Pathologically, early and intermediate stages are characterized by RPE dysfunction, often revealing as drusen accumulation and pigmentary changes. In advanced stages such as GA, there is widespread RPE and photoreceptor loss accompanied by choriocapillaris atrophy (4). The RPE, a monolayer of specialized epithelial cells, is essential for maintaining photoreceptor integrity. It performs critical roles, including the phagocytosis of photoreceptor outer segments, nutrient transport, and participation in the visual cycle (10). Its degeneration disrupts retinal homeostasis and initiates secondary photoreceptor loss, ultimately leading to central vision impairment (11). Oxidative stress is recognized as a major contributor to RPE damage (12). The macula is particularly susceptible due to high oxygen consumption, continuous light exposure, and the abundance of polyunsaturated fatty acids (2, 13). These conditions, combined with aging and environmental insults, generate cumulative oxidative stress that drives RPE dysfunction and degeneration (2). Preclinical studies have demonstrated that oxidative damage reproduces key pathological features associated with dry AMD (4).

Given the central role of oxidative stress in AMD pathogenesis, antioxidant-based interventions have gained attention as potential therapeutic strategies. Taurine, a sulfur-containing β-amino acid, is the most abundant free amino acid in the retina and plays a critical role in maintaining normal retinal structure and function (14). It contributes to cellular osmoregulation, calcium homeostasis, membrane stabilization, and, importantly, oxidative stress defense (15–17). Taurine deficiency is known to cause photoreceptor degeneration and impaired visual function, as demonstrated in early studies involving taurine-deficient cats and rodents (18, 19). Recent studies demonstrate the neuroprotective potential of taurine in various models of retinal degeneration. Systemic taurine supplementation has been shown to reduce oxidative damage and inflammation, preserve photoreceptor survival, and improve visual responses in both chemically and genetically induced models of retinal degeneration (14, 20, 21). In a mouse model of N-methyl-N-nitrosourea (MNU)–induced retinopathy, daily administration of taurine (200 mg/kg) intravenously for 7 consecutive days before and after MNU delivery preserved cone photoreceptor populations, reduced apoptosis and oxidative stress, and improved visual function (20). Similarly, in dystrophic Royal College of Surgeons (RCS) rats with impaired RPE phagocytosis due to a MERTK mutation, taurine provided in drinking water (0.2 M) from postnatal day 21 to 45 resulted in greater photoreceptor survival, enhanced rod and cone responses, reduced microglial infiltration and glial reactivity, and improved phagocytic activity by the retinal pigment epithelium (22). These collective findings indicate that taurine may provide a promising neuroprotective strategy to slow or mitigate the progression of retinal degeneration. Additionally, in humans, oral taurine supplementation (100 mg/kg/day for two years) restored normal plasma taurine levels and stopped progression of retinal degeneration while improving vision in a child with SLC6A6-related inherited retinopathy, demonstrating its potential as a therapeutic strategy for similar disorders (23).

There is currently no animal model that fully recapitulates the progressive features of human dry AMD. Genetic models, such as RCS rats, primarily reflect monogenic causes of degeneration, whereas AMD arises from multifactorial genetic and environmental influences (24, 25). Among experimental systems, sodium iodate (NaIO3)–induced models are widely used due to their accessibility, reproducibility, and ability to selectively target the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). NaIO3 promotes intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress amplification, and RPE cell death through apoptosis, necroptosis, or necrosis in a dose-dependent manner (26–30). Additional toxicity arises from interactions with melanin, generating glyoxylate and inhibiting key metabolic enzymes (30). Loss of RPE integrity subsequently compromises photoreceptor survival, manifesting as thinning of the outer nuclear layer, while associated immune activation, including complement pathways and microglial infiltration, further propagates retinal inflammation and degeneration (26, 31).

Previous studies have demonstrated that NaIO3 injection in rodents induces a spectrum of retinal damage, ranging from localized RPE disruption to widespread geographic atrophy-like lesions (4). However, the effects of NaIO3 vary across studies, influenced by factors such as the administered dose, route of delivery, animal strain, and age. These factors significantly influence the severity and distribution of retinal lesions. In C57BL/6J mice, intravenous administration of NaIO3 resulted in dose-dependent structural alterations: 10–20 mg/kg caused no detectable long-term retinal thinning by OCT, 30 mg/kg induced moderate structural degeneration with visible thinning of the RPE and outer retina, and doses ≥ 40 mg/kg produced extensive retinal atrophy characterized by pronounced disruption and thinning across multiple retinal layers (4). A previous study in Sprague-Dawley rats demonstrated intravenous delivery of 40 mg/kg NaIO3 produced degenerative lesions in the outer retina, while higher doses resulted in more acute damage (32).

This study investigated the potential of taurine to protect against retinal degeneration associated with oxidative stress. In vitro, we examined whether taurine could preserve the viability, proliferative capacity, and regenerative potential of cultured human RPE cells following NaIO3-induced oxidative stress. In vivo, we assessed whether prolonged oral taurine supplementation could mitigate structural retinal damage in a pigmented rat model of mild dry AMD.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Animal preparation

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Stevens Institute of Technology (Protocol #2022-002). Experimental protocols adhered to the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Male Long-Evans rats (225–275 g; Charles River Laboratories, Fairfield, NJ, USA) were housed under standard laboratory conditions with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and given ad libitum access to food and water. Prior to all procedures and imaging sessions, rats were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of ketamine hydrochloride (80 mg/kg; Dechra Veterinary Products, Overland Park, KS, USA) and xylazine (10 mg/kg; Cronus Pharma LLC, East Brunswick, NJ, USA). Topical anesthesia of the cornea was achieved using proparacaine hydrochloride ophthalmic drops (Alcon Laboratories Inc., Fort Worth, TX, USA). Pupillary dilation was induced using topical phenylephrine and atropine eye drops (both from Lifestar Pharma LLC, Mahwah, NJ, USA). To maintain physiological conditions during the experiments, animals were placed on a heated stage to sustain core body temperature at approximately 37°C.

2.2 Experimental design and sodium iodate-induced retinal degeneration

Sodium iodate (Thermo Scientific Chemicals, Waltham, MA, USA) was freshly prepared at a concentration of 1% (w/v) in sterile saline immediately before administration. To evaluate the impact of NaIO3 dose and route of administration on retinal degeneration severity and progression, six rats were randomly assigned to the following groups: (1) Healthy Control Group, sterile saline treatment administered intraperitoneally; (2) Gradual mild AMD Group, received intraperitoneal (IP) injection of 50 mg/kg NaIO3; and (3) Rapid severe AMD Group, received intravenous (IV) injection of 80 mg/kg NaIO3 via the lateral tail vein. The mild AMD model, induced via IP injection of NaIO3, was subsequently used to assess the therapeutic efficacy of oral taurine supplementation.

2.3 Assessment of taurine protection effect

2.3.1 Cell culture and taurine treatments

Human retinal pigment epithelial cells (hTERT-RPE1; ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in a 1:1 mixture of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium and Ham’s F-12 (DMEM/F-12), supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. Cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. For experiments, cells were seeded and grown to approximately 50–70% confluence before treatment. Taurine (2 mM; Thermo Scientific Chemicals) was added to the culture medium 24 hours prior to sodium iodate exposure to allow cellular uptake. Cells were divided into three groups: an untreated control group, a group exposed to 2 mM NaIO3, and a group co-treated with 2 mM NaIO3 and 2 mM taurine. The selection of 2 mM NaIO3 was to induce a sublethal level of oxidative stress in human RPE cell lines that is optimal for evaluating cytoprotective interventions (33).

2.3.2 Cell proliferation assay

To monitor cell growth over time, cells were seeded at equal densities and allowed to adhere overnight. Cell counts were recorded over a 7-day period using an automated cell counter (Luna II, Logos Biosystems, Annandale, VA, USA). This assay was used to assess the impact of NaIO3 and taurine on RPE cell proliferation.

2.3.3 Propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry

Cell viability and death were further evaluated using PI staining. Treated cells were harvested, washed with PBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and incubated with 5 μg/mL propidium iodide for 30 minutes at room temperature. Samples were analyzed using an Attune NxT flow cytometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Viable cells excluded PI and were considered PI-negative, whereas non-viable cells took up the dye and were recorded as PI-positive.

2.3.4 Wound healing assay

To assess regenerative capacity following injury, RPE cells were cultured to full confluence and treated with taurine, with or without NaIO3. A linear scratch was introduced using a sterile 10 μL pipette tip. Following PBS washing to remove detached cells, treatment-containing media were reapplied. Wound closure was monitored for 24 hours using time-lapse live-cell microscopy (BioTek Lionheart FX, Winooski, VT, USA). Images were analyzed using ImageJ software, and wound closure was quantified by comparing the remaining wound area at each time point to the initial wound size (34).

2.3.5 Taurine treatment in animal study

Taurine was administered in drinking water at a concentration of 1.5% (w/v), following previously established dosing protocols (35). Four rats were assigned to the taurine treatment group. Half of these animals began taurine supplementation two weeks prior to NaIO3 injection, while the remaining half initiated taurine treatment two weeks after NaIO3 administration. As both pre- and post-treatment subgroups demonstrated comparable retinal outcomes, they were combined into a single taurine treatment group for analysis.

2.4 Retinal imaging and quantification

Retinal structural assessment was performed using a confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope (cSLO) equipped with optical coherence tomography (OCT) (SPECTRALIS; Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany). Imaging was conducted biweekly starting at baseline (prior to NaIO3 injection) and continued for 6 weeks in the dose- and route-dependent NaIO3-induced retinal degeneration study (Section 2.2), and for 20 weeks in the oral taurine treatment efficacy study (Section 2.3.5), following the respective experimental design. Retinal thickness was evaluated on OCT scans using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). For each eye, 14–20 measurements of the outer nuclear layer (ONL) and total retinal thickness (TRT) were obtained from each side of the optic disc. These measurements were averaged per eye, and group means were calculated across all eyes under the same experimental condition.

2.5 Statistical analysis

All quantitative data are reported as mean ± standard deviation of the mean (SD). Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism software. Differences in cell behavior were assessed using one-way ANOVA that was used for comparison among three groups, followed by the Holm–Sidak post hoc test for multiple comparisons. Unpaired t-tests were employed for comparisons between the control and test group. For comparisons between the control and individual treatment groups at specific time points, multiple unpaired t-tests were conducted. Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons was utilized to compare differences in normalized retinal thickness after taurine administration. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05, and significance was indicated in graphical data using asterisks.

3 Results

3.1 Taurine preserves human RPE cell viability and regeneration under oxidative stress

To evaluate the protective effect of taurine against NaIO3-induced toxicity, a series of in vitro assays were conducted using cultured human retinal pigment epithelial (hTERT-RPE1 cell line). Flow cytometry analysis of propidium iodide staining demonstrated that exposure to 2 mM NaIO3 resulted in approximately 78.5 ± 3.0% cell death, as determined by propidium iodide staining followed by flow cytometry analysis (Figures 1A, B). Co-treatment with 2 mM taurine markedly reduced cell death to 21.9 ± 2.8%, indicating a substantial cytoprotective effect.

Figure 1. (A, B) Flow cytometry analysis of propidium iodide signal inferring cell death, (C) Cell proliferation data over seven days, (D) Quantification of wound closure percentage 24 hours post-scratch injury, (E) Representative images of scratch assays at 0 and 24 hours across treatment groups. Error bars are standard deviation. *statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Exposure of RPE cells to 2 mM sodium iodate markedly reduced their proliferation capacity, indicating that NaIO3 inhibits RPE cell division (Figure 1C). However, co-treatment with 2 mM taurine effectively rescued this inhibitory effect, restoring cell growth to levels comparable to untreated controls. This suggests that taurine mitigates NaIO3-induced suppression of cell proliferation. In wound healing assays, NaIO3 significantly impaired the regenerative ability of the RPE monolayer, as shown by delayed wound closure following mechanical injury. In contrast, taurine treatment markedly improved the rate of wound closure after NaIO3 insult from 69.6 ± 3.2% to 86.6 ± 1.1% and restored regenerative capacity (Figures 1D, E), indicating preservation of epithelial repair mechanisms. These functional assessments demonstrate that exposure of RPE cells to NaIO3 disrupts survival, proliferation and regeneration of RPE cells and highlight taurine’s cytoprotective effects to support RPE cell viability under oxidative stress.

3.2 Comparative retinal degeneration in mild and severe dry AMD models

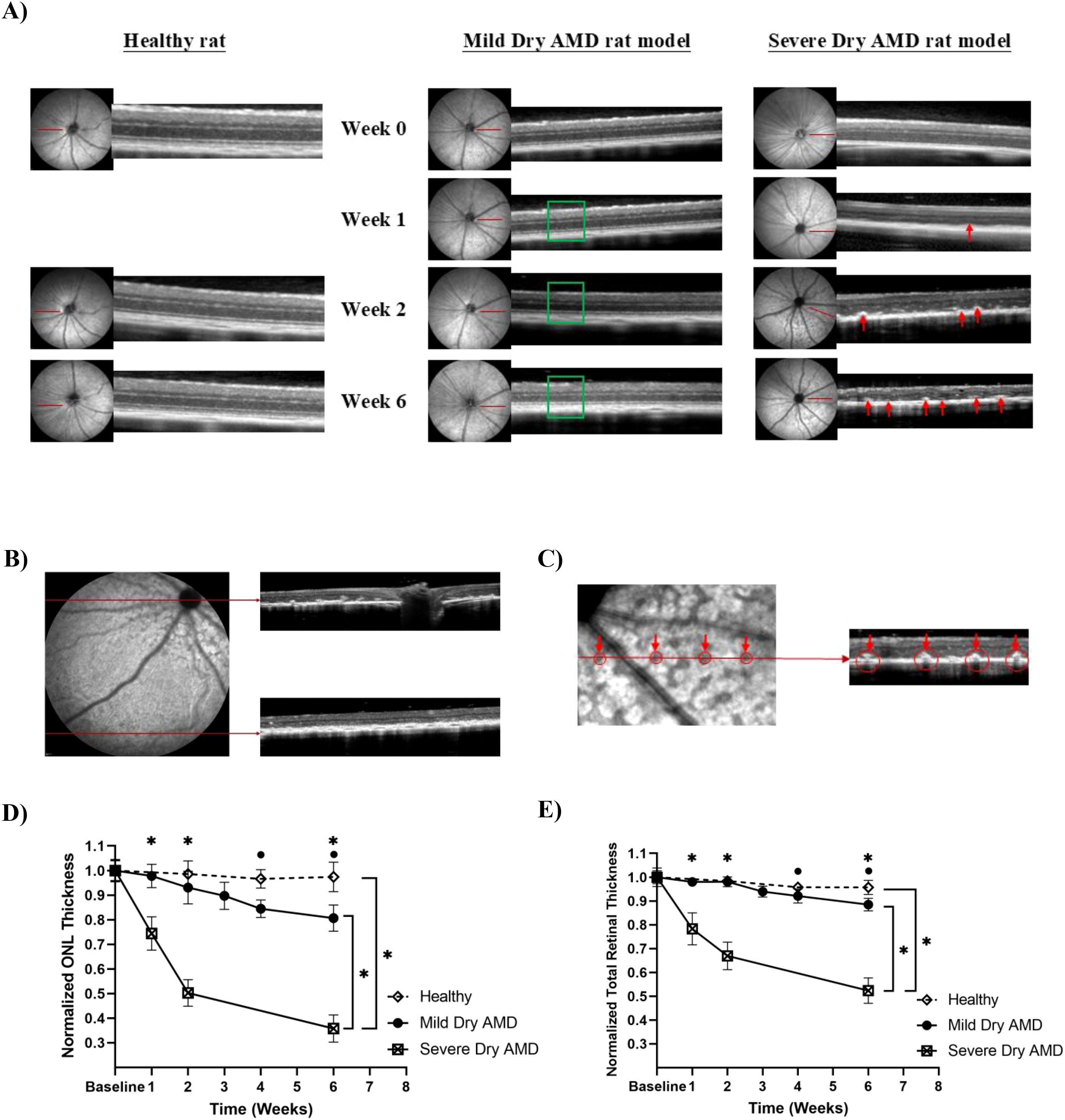

To investigate how sodium iodate (NaIO3) dose and administration route influence the onset and severity of retinal degeneration, two models of dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD) were developed in Long-Evans rats. A lower-dose intraperitoneal (IP) model using 50 mg/kg NaIO3 (low-dose IP) was used to mimic slow progressive mild degeneration, while a high-dose intravenous (IV) model using 80 mg/kg NaIO3 (high-dose IV) was designed to replicate advanced dry AMD. Infrared (IR) reflectance fundus imaging captured pronounced differences in disease progression between the two models. Dark patches in the IR images represent localized RPE atrophy and melanin loss (36). Rats in the low-dose IP group did not exhibit such dark regions throughout the observation period (Figure 2A). In contrast, in the high-dose IV group, extensive dark patches were evident as early as one week after NaIO3 injection (Figure 2A). These dark patches were localized predominantly around the optic nerve head and gradually became less prominent toward the periphery, as shown in the IR image in Figure 2B. OCT imaging revealed additional structural differences. While rats in the low-dose IP group exhibited normal retinal structure without hyperreflective abnormalities (green box), those in the high-dose IV group displayed dome-shaped hyperreflective foci between the outer nuclear layer (ONL) and the photoreceptor segments as early as week 1 (red arrows) (Figure 2A). They result from increased scattering by cellular retinal structural disorganization at this region and intensified over time (37). Notably, the distribution of these hyperreflective lesions mirrored the regional pattern of IR abnormalities, being most prominent around the optic nerve head and less evident toward the periphery (Figure 2B). These lesions were associated with thinning of the ONL, disorganization of the photoreceptor outer segments, and progressive loss of total retinal thickness (32). Quantitative analysis showed that the rats in the low-dose IP group exhibited a more moderate reduction in ONL thickness of 19.4 ± 5.3% compared to 64.2 ± 5.5% in the high-dose IV group by week six (Figure 2D). Similarly, total retinal thickness (TRT) decreased by 11.5 ± 2.6% in the low-dose IP group, while the high-dose IV group showed a severe decline of 47.6 ± 5.4% (Figure 2E). No considerable changes were observed in the ONL (< 2.6%) or TRT (< 4.3%) of the healthy control group throughout the experiment. Figure 2C further illustrates the spatial correspondence between planar dark areas on IR reflectance imaging and focal hyperreflective lesions in OCT cross-sections. Red arrows in the IR images indicate localized signal loss along the scan line, while matching arrows in the OCT images highlight hyperreflective regions that align anatomically with the IR findings. This colocalization supports a consistent association between reflectance abnormalities and structural changes in the retina, particularly involving RPE atrophy and photoreceptor layer disorganization. Based on the current findings, the low-dose IP group was used to test the oral taurine neuroprotective effects.

Figure 2. (A) The IR reflectance for the sodium iodate-induced mild and severe dry AMD rat model, and the cross-sectional OCT images showing the appearance of retinal layers from a representative experimental animal. The green box highlights the preserved retinal structure without hyperreflective abnormalities, whereas the red arrows indicate dome-shaped hyperreflective foci between the ONL and photoreceptor segments, representing early degenerative changes observed at week 1 and progressing over time, (B) Spatial pattern of retinal degeneration highlighting regional variability in susceptibility to oxidative damage, with the peripapillary zone showing greater degeneration compared to the peripheral retina, (C) Dark blots in IR reflectance images are correlated to the degenerative profiles in OCT images, (D, E) Normalized ONL and total retinal thickness measurements for mild and severe dry AMD rat model. Error bars are standard deviation. *statistically significant (p < 0.05).

3.3 Oral taurine supplementation preserves retinal structure in a rat model of mild dry AMD

In vivo experiments were carried out to assess the structural preservation of the retina following oral taurine supplementation in rats exposed to 50 mg/kg intraperitoneal NaIO3. Two taurine administration schedules were evaluated: one beginning two weeks prior to NaIO3 injection (pre-treatment) and one beginning two weeks after injection (post-treatment). No significant difference was observed between these two regimens in terms of TRT (p = 0.15) and ONL (p = 0.55) preservation (Figures 3A, B). Longitudinal retinal measurements showed that both pre- and post- oral taurine significantly mitigated ONL thinning compared to the untreated control group. Specifically, ONL thickness reduction was 17.7 ± 4.5% in the pre-treated group and 17.4 ± 4.8% in the post-treated group, compared to 36.1 ± 3.7% in the untreated degeneration group (Figure 3A). TRT was similarly preserved, exhibiting reductions of 9.6 ± 3.3% (pre-treated) and 6.3 ± 4.0% (post-treated) whereas the untreated group demonstrated a 17.7 ± 2.1% reduction (Figure 3B). These data indicate that oral taurine mitigated NaIO3-induced retinal thinning, mainly ONL layer, and preserved structural integrity of the retinal layers under oxidative stress conditions.

Figure 3. (A, B) Normalized ONL and total retinal thickness measurements for the untreated control group (n = 3 rats) versus oral taurine pre- (n = 2 rats) and post-treatment (n = 2 rats) groups. Statistical differences were determined using Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons (p < 0.05). Error bars are standard deviation. *statistically significant (p < 0.05). *statistically significant (p < 0.05).

4 Discussion

This study evaluated the neuroprotective potential of oral taurine supplementation, a compound known for its antioxidant and membrane-stabilizing properties. By assessing the extent of retinal preservation in taurine-treated animals under mild conditions modeling slow progressive dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD), this work provides insights into its therapeutic utility under oxidative stress conditions for slowing or mitigating dry AMD progression. To establish an appropriate model for assessing taurine’s therapeutic effects, we investigated the retinal effects of sodium iodate (NaIO3) administration in a pigmented rodent model to establish and differentiate between mild and severe phenotypes of dry AMD. By employing two distinct dosing regimens, we aimed to control the progression of RPE and photoreceptor degeneration.

To explore taurine’s direct cytoprotective effects in vitro, we first examined its impact on human RPE cells exposed to NaIO3 (Figure 1). Taurine treatment maintained cellular viability under NaIO3-induced cytotoxic stress, suggesting a substantial capacity to enhance RPE resilience. While oxidative stress was not directly assessed in this study, the observed protective effects align with NaIO3’s known mechanism of toxicity, which primarily involves oxidative and mitochondrial damage to RPE cells. Taurine’s cytoprotective actions have been extensively documented and are attributed to several complementary pathways, including modulation of intracellular calcium homeostasis, maintenance of mitochondrial membrane potential, and suppression of caspase-dependent apoptosis (38, 39). Importantly, taurine scavenges hypochlorous acid, a potent oxidant produced by neutrophils, forming taurine chloramine, a less reactive compound that exerts both antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects (40, 41). Additionally, taurine mitigates mitochondrial superoxide generation, thereby reducing one of the major intracellular sources of reactive oxygen species (42).

Moreover, our results show the preservation of cell proliferation and wound healing capacity in taurine-treated RPE cultures, which suggests that taurine not only prevents cytotoxicity but also actively supports cellular regenerative functions. Taurine-treated cells maintained growth rates comparable to untreated controls, indicating sustained mitotic activity even under insult. In addition, taurine significantly improved wound closure in scratch assays, reflecting enhanced cell migration and monolayer repair. Previous reports showed that taurine promotes proliferation in human and rabbit RPE cells (43), supporting its role in cellular renewal. Therefore, the improved cell viability and migration observed in our study following taurine treatment are consistent with a generalized cytoprotective response, involving but not limited to antioxidant mechanisms.

Building on these in vitro findings, we next established and compared two distinct NaIO3-induced retinal degeneration models in pigmented rats to evaluate how the severity of retinal degeneration influences the appearance of dry AMD-like pathology and to identify an appropriate model for assessing taurine’s in vivo protective potential. Only male rats were used to provide a consistent baseline for evaluation by avoiding variability related to hormonal cycles and estrogen-associated antioxidant effects (44, 45). Future studies should investigate sex as a biological variable, since previous reports showed that sex-specific differences in NaIO3 susceptibility (46, 47).

The method of NaIO3 delivery has a critical influence on the extent and rate of retinal injury. Consistent with earlier findings, intraperitoneal (IP) injection results in slower systemic absorption and milder toxicity, whereas intravenous (IV) administration produces a rapid increase in plasma concentration and more severe, widespread damage (32). Therefore, we used 50 mg/kg IP NaIO3 to model gradual mild retinal degeneration and 80 mg/kg IV NaIO3 to mimic more rapid severe disease. Evidence of RPE atrophy was supported by persistent dark regions on near- IR fundus imaging, resulting from melanin depletion that contributes to IR reflectivity (Figure 2A) (36). OCT imaging further revealed early signs of outer retinal disruption, including hyperreflective foci and disorganization in the outer nuclear layer and photoreceptor segments, consistent with localized cell damage. NaIO3 mainly exerts selective toxicity toward RPE, leading to RPE cell loss and atrophy (48). As a result, it can no longer perform its normal functions in maintaining photoreceptor health through phagocytosis of photoreceptor outer segments, nutrient transport, and oxidative stress regulation. This leads to secondary damage in the photoreceptors through disorganization of the photoreceptor layer and progressive thinning of the ONL, which contains the photoreceptor nuclei. As the injury progressed, these alterations evolved into more pronounced structural changes, including retinal thinning and disruption of the photoreceptor integrity, aligning with the degenerative trajectory observed in advanced dry AMD. This interpretation is consistent with established mechanisms described in previous studies, providing contextual support for the observed findings.

The spatial pattern of retinal degeneration, seen as dark patches in IR images and hyperreflective lesions in OCT scans, reflects regional differences in sensitivity to oxidative stress. Greater damage was observed in the peripapillary region compared to the peripheral retina, suggesting this central zone is more vulnerable to NaIO3-induced injury (Figure 2B). This pattern corresponds to higher metabolic and oxygen demand near the optic nerve head, prompting central retinal regions to greater ROS accumulation as reported in previous study (49). Regional variations in antioxidant enzyme activity may also contribute, as human retinal studies have shown lower catalase and glutathione peroxidase activity in the macula compared to peripheral regions, suggesting that zones with lower antioxidant capacity are less prepared to neutralize ROS and hence are more susceptible to oxidative insult (50).

A clear correspondence between the planar dark areas observed in IR imaging and dome-shaped hyperreflective lesions in OCT (Figure 2C) highlights the link between imaging abnormalities and underlying structural damage within the retina. Regions of reduced IR reflectivity are commonly associated with RPE atrophy and melanin loss. These areas align closely with localized disruptions in the photoreceptor layer, suggesting that damage to the RPE compromises the health and stability of the overlying photoreceptors. In contrast, the low-dose IP model exhibited preserved retinal architecture and normal IR reflectivity, highlighting the critical role of dose and administration route in determining disease severity and progression.

Longitudinal OCT analysis demonstrated distinct thinning trajectories between the IV and IP NaIO3 models (Figure 2D). The high-dose IV model showed rapid ONL and total retinal thickness (TRT) loss reflecting acute RPE destruction and widespread photoreceptor death. The gradual thinning observed in the low-dose IP model reflected a more chronic process, representative of slow progressive mild AMD (26). ONL thinning appeared earlier and progressed faster than overall TRT reduction, supporting its role as an early biomarker of photoreceptor degeneration. The more pronounced TRT decline in the IV model suggests damage extended into inner retinal layers, likely due to extensive RPE loss and secondary degeneration across multiple layers, driven by severe NaIO3-induced oxidative stress (4). Conversely, the slower rate of TRT decline in the lower-dose IP group suggests that inner retinal layers were less affected, as lower NaIO3 doses primarily affect the RPE and outer retina, while inner retinal layers demonstrate greater preservation due to being both functionally less dependent on RPE support and anatomically more distant from the site of toxicity (4). Previous studies confirm that extensive NaIO3 injury affects not only photoreceptors but also inner retinal neurons, including dopaminergic amacrine and retinal ganglion cells, through caspase and calpain activation (28). The structural deterioration in our IV model is consistent with these reports, demonstrating system-wide degeneration, whereas the IP model better represents a manageable oxidative stress level suitable for therapeutic testing.

The route-dependent variation in damage severity can be explained by pharmacokinetics. Intravenous administration produces a sharp plasma spike and immediate retinal exposure, resulting in rapid oxidative insult, while intraperitoneal delivery produces lower peak concentrations and slower systemic distribution (32, 51). Moreover, IV NaIO3 doses above 50 mg/kg have been linked to hepatic and renal injury (32). This highlights the importance of dose selection and route of administration for minimizing systemic effects and improving the ocular outcome assessments.

Following establishment of the slow progressive IP model, taurine’s protective efficacy was evaluated under these milder retinal degeneration conditions. In vivo, oral taurine supplementation mitigated ONL and TRT thinning in rats subjected to NaIO3-induced stress. Although specific oxidative markers were not quantified, the preserved retinal architecture is consistent with taurine’s antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, and membrane-stabilizing properties. The outcome agrees with previous reports showing that taurine supplementation preserves photoreceptor structure and synaptic organization in other various models of retinal degeneration, including RCS rats and MNU-exposed mice (20, 22). These studies collectively support the view that taurine’s beneficial effects arise through antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, and synapse-preserving mechanisms. Our structural findings are consistent with the broader evidence base supporting the cytoprotective role of taurine.

In conclusion, this study highlights the therapeutic potential of taurine in protecting against retinal degeneration, particularly under conditions that mimic slow progressive dry AMD. Using a mild NaIO3-induced model in pigmented rats, taurine supplementation preserved retinal structure and demonstrated cytoprotective effects consistent with resistance to oxidative damage, thus highlighting taurine as a potential candidate for further investigation in retinal degeneration therapy. While the current findings primarily reflect anatomical preservation, future studies incorporating functional assessments and long-term treatment paradigms will be essential to fully explain taurine’s therapeutic potential.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies on humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because only commercially available established cell lines were used. The animal study was approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, NJ, USA. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

MA: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TP: Data curation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. AM: Writing – review & editing. FT: Writing – review & editing. MM: Writing – review & editing. MI: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. JK-M: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Wong WL, Su X, Li X, Cheung CMG, Klein R, Cheng C-Y, et al. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Global Health. (2014) 2:e106–16. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70145-1

2. Maurya M, Bora K, Blomfield AK, Pavlovich MC, Huang S, Liu C-H, et al. Oxidative stress in retinal pigment epithelium degeneration: From pathogenesis to therapeutic targets in dry age-related macular degeneration. Neural Regenerat Res. (2023) 18:2173–81. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.369098

3. Bandello F, Sacconi R, Querques L, Corbelli E, Cicinelli MV, and Querques G. Recent advances in the management of dry age-related macular degeneration: a review. F1000Research. (2017) 6:245. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.10664.1

4. Koster C, van den Hurk KT, Ten Brink JB, Lewallen CF, Stanzel BV, Bharti K, et al. Sodium-iodate injection can replicate retinal degenerative disease stages in pigmented mice and rats: Non-invasive follow-up using OCT and ERG. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23:2918. doi: 10.3390/ijms23062918

5. Schultz NM, Bhardwaj S, Barclay C, Gaspar L, and Schwartz J. Global burden of dry age-related macular degeneration: a targeted literature review. Clin Ther. (2021) 43:1792–818. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2021.08.011

6. Gorusupudi A, Nelson K, and Bernstein PS. The age-related eye disease 2 study: micronutrients in the treatment of macular degeneration. Adv Nutr. (2017) 8:40–53. doi: 10.3945/an.116.013177

7. Liao DS, Grossi FV, El Mehdi D, Gerber MR, Brown DM, Heier JS, et al. Complement C3 inhibitor pegcetacoplan for geographic atrophy secondary to age-related macular degeneration: a randomized phase 2 trial. Ophthalmology. (2020) 127:186–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2019.07.011

8. Danzig CJ, Khanani AM, and Loewenstein A. C5 inhibitor avacincaptad pegol treatment for geographic atrophy: A comprehensive review. Immunotherapy. (2024) 16:779–90. doi: 10.1080/1750743X.2024.2368342

9. Cruz-Pimentel M and Wu L. Complement inhibitors for advanced dry age-related macular degeneration (geographic atrophy): some light at the end of the tunnel? J Clin Med. (2023) 12:5131. doi: 10.3390/jcm12155131

10. Wang S, Li W, Chen M, Cao Y, Lu W, and Li X. The retinal pigment epithelium: functions and roles in ocular diseases. Fundam Res. (2023) 4:1710–18. doi: 10.1016/j.fmre.2023.08.011

11. Wang K, Liu Y, Li S, Zhao N, Qin F, Tao Y, et al. Unveiling the therapeutic potential and mechanisms of stanniocalcin-1 in retinal degeneration. Survey Ophthalmol. (2024) 70:106–20. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2024.08.001

12. Datta S, Cano M, Ebrahimi K, Wang L, and Handa JT. The impact of oxidative stress and inflammation on RPE degeneration in non-neovascular AMD. Prog Retinal eye Res. (2017) 60:201–18. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2017.03.002

13. Chaudhuri M, Hassan Y, Vemana PPSB, Pattanashetty MSB, Abdin ZU, Siddiqui HF, et al. Age-related macular degeneration: an exponentially emerging imminent threat of visual impairment and irreversible blindness. Cureus. (2023) 15:e39624. doi: 10.7759/cureus.39624

14. Froger N, Moutsimilli L, Cadetti L, Jammoul F, Wang Q-P, Fan Y, et al. Taurine: the comeback of a neutraceutical in the prevention of retinal degenerations. Prog Retinal eye Res. (2014) 41:44–63. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2014.03.001

15. Pasantes-Morales H and Cruz C. Taurine: a physiological stabilizer of photoreceptor membranes. Prog Clin Biol Res. (1985) 179:371–81.

16. El Idrissi A and Trenkner E. Growth factors and taurine protect against excitotoxicity by stabilizing calcium homeostasis and energy metabolism. J Neurosci. (1999) 19:9459–68. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09459.1999

17. Schaffer S, Takahashi K, and Azuma J. Role of osmoregulation in the actions of taurine. Amino Acids. (2000) 19:527–46. doi: 10.1007/s007260070004

18. Schmidt SY. (1981). Taurine in retinas of taurine-deficient cats and RCS rats. The Effects of Taurine on Excitable Tissues, in: Proceedings of the 21st Annual AN Richards Symposium of the Physiological Society of Philadelphia, Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, April 23–24, 1979, Berlin, Germany: Springer Nature.

19. Heller-Stilb B, van Roeyen C, Rascher K, Hartwig H-G, Huth A, Seeliger MW, et al. Disruption of the taurine transporter gene (taut) leads to retinal degeneration in mice. FASEB J. (2002) 16:1–18. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0691fje

20. Tao Y, He M, Yang Q, Ma Z, Qu Y, Chen W, et al. Systemic taurine treatment provides neuroprotection against retinal photoreceptor degeneration and visual function impairments. Drug Design Dev Ther. (2019) 13:2689. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S194169

21. Lee D and Smith LE. Therapeutic effects of taurine and histidine supplementation in retinal diseases. Life. (2024) 14:1566. doi: 10.3390/life14121566

22. Martínez-Vacas A, Di Pierdomenico J, Gallego-Ortega A, Valiente-Soriano FJ, Vidal-Sanz M, Picaud S, et al. Systemic taurine treatment affords functional and morphological neuroprotection of photoreceptors and restores retinal pigment epithelium function in RCS rats. Redox Biol. (2022) 57:102506. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2022.102506

23. Ansar M, Ranza E, Shetty M, Paracha SA, Azam M, Kern I, et al. Taurine treatment of retinal degeneration and cardiomyopathy in a consanguineous family with SLC6A6 taurine transporter deficiency. Hum Mol Genet. (2020) 29:618–23. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddz303

24. Stradiotto E, Allegrini D, Fossati G, Raimondi R, Sorrentino T, Tripepi D, et al. Genetic aspects of age-related macular degeneration and their therapeutic potential. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23:13280. doi: 10.3390/ijms232113280

25. Bhumika NS and Bora PS. Genetic insights into age-related macular degeneration. Biomedicines. (1479) 12:1479. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines12071479

26. Kannan R and Hinton DR. Sodium iodate induced retinal degeneration: new insights from an old model. Neural Regenerat Res. (2014) 9:2044–5. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.147927

27. Zhou P, Kannan R, Spee C, Sreekumar PG, Dou G, and Hinton DR. Protection of retina by αB crystallin in sodium iodate induced retinal degeneration. PloS One. (2014) 9:e98275. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098275

28. Balmer J, Zulliger R, Roberti S, and Enzmann V. Retinal cell death caused by sodium iodate involves multiple caspase-dependent and caspase-independent cell-death pathways. Int J Mol Sci. (2015) 16:15086–103. doi: 10.3390/ijms160715086

29. Hanus J, Anderson C, Sarraf D, Ma J, and Wang S. Retinal pigment epithelial cell necroptosis in response to sodium iodate. Cell Death Discov. (2016) 2:1–9. doi: 10.1038/cddiscovery.2016.54

30. Espitia-Arias MD, de la Villa P, Paleo-García V, Germain F, and Milla-Navarro S. Oxidative model of retinal neurodegeneration induced by sodium iodate: morphofunctional assessment of the visual pathway. Antioxidants. (2023) 12:1594. doi: 10.3390/antiox12081594

31. Enzbrenner A, Zulliger R, Biber J, Pousa AMQ, Schäfer N, Stucki C, et al. Sodium iodate-induced degeneration results in local complement changes and inflammatory processes in murine retina. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:9218. doi: 10.3390/ijms22179218

32. Yang Y, Ng TK, Ye C, Yip YW, Law K, Chan S-O, et al. Assessing sodium iodate–induced outer retinal changes in rats using confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy and optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Visual Sci. (2014) 55:1696–705. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12477

33. Kolko M, Vohra R, van der Burght BW, Poulsen K, and Nissen MH. Calcium-independent phospholipase A2, group VIA, is critical for RPE cell survival. Mol Vision. (2014) 20:511.

34. Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. (2012) 9:676–82. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019

35. Militante J and Lombardini JB. Age-related retinal degeneration in animal models of aging: possible involvement of taurine deficiency and oxidative stress. Neurochemical Research. (2004) 29:151–60.

36. Zhao J, Kim HJ, and Sparrow JR. Multimodal fundus imaging of sodium iodate-treated mice informs RPE susceptibility and origins of increased fundus autofluorescence. Invest Ophthalmol Visual Sci. (2017) 58:2152–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.17-21557

37. Durlu YK and Canbek S. Posterior segment findings in a patient with a CDHR1 biallelic pathogenic variant. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. (2024) 36:102228. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2024.102228

38. Foos TM and Wu J-Y. The role of taurine in the central nervous system and the modulation of intracellular calcium homeostasis. Neurochem Res. (2002) 27:21–6. doi: 10.1023/A:1014890219513

39. Castelli V, Paladini A, d’Angelo M, Allegretti M, Mantelli F, Brandolini L, et al. Taurine and oxidative stress in retinal health and disease. CNS Neurosci Ther. (2021) 27:403–12. doi: 10.1111/cns.13610

40. Marcinkiewicz J, Grabowska A, Bereta J, and Stelmaszynska T. Taurine chloramine, a product of activated neutrophils, inhibits in vitro the generation of nitric oxide and other macrophage inflammatory mediators. J Leucocyte Biol. (1995) 58:667–74. doi: 10.1002/jlb.58.6.667

41. Kim C and Cha Y-N. Taurine chloramine produced from taurine under inflammation provides anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective effects. Amino Acids. (2014) 46:89–100. doi: 10.1007/s00726-013-1545-6

42. Jong CJ, Azuma J, and Schaffer S. Mechanism underlying the antioxidant activity of taurine: prevention of mitochondrial oxidant production. Amino Acids. (2012) 42:2223–32. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-0962-7

43. Gabrielian K, Wang H-M, Ogden TE, and Ryan SJ. In vitro stimulation of retinal pigment epithelium proliferation by taurine. Curr eye Res. (1992) 11:481–7. doi: 10.3109/02713689209001804

44. Bhavnani BR, Cecutti A, Gerulath A, Woolever AC, and Berco M. Comparison of the antioxidant effects of equine estrogens, red wine components, vitamin E, and probucol on low-density lipoprotein oxidation in postmenopausal women. Menopause. (2018) 25:1214–23.

45. Feskanich D, Cho E, Schaumberg DA, Colditz GA, and Hankinson SE. Menopausal and reproductive factors and risk of age-related macular degeneration. Archives of Ophthalmology. (2008) 126:519–24.

46. Schnabolk G, Obert E, Banda NK, and Rohrer B. Systemic inflammation by collagen-induced arthritis affects the progression of age-related macular degeneration differently in two mouse models of the disease. Invest Ophthalmol Visual Sci. (2020) 61:11–1. doi: 10.1167/iovs.61.14.11

47. Yang X, Rai U, Chung J-Y, and Esumi N. Fine tuning of an oxidative stress model with sodium iodate revealed protective effect of NF-κB inhibition and sex-specific difference in susceptibility of the retinal pigment epithelium. Antioxidants. (2021) 11:103. doi: 10.3390/antiox11010103

48. Machalińska A, Lubiński W, Kłos P, Kawa M, Baumert B, Penkala K, et al. Sodium iodate selectively injuries the posterior pole of the retina in a dose-dependent manner: morphological and electrophysiological study. Neurochem Res. (2010) 35:1819–27. doi: 10.1007/s11064-010-0248-6

49. De Vera Mudry MC, Kronenberg S, and S.-i. Komatsu and GD. Blinded by the light: retinal phototoxicity in the context of safety studies. Toxicol Pathol. (2013) 41:813–25. doi: 10.1177/0192623312469308

50. De La Paz MA, Zhang J, and Fridovich I. Antioxidant enzymes of the human retina: effect of age on enzyme activity of macula and periphery. Curr eye Res. (1996) 15:273–8. doi: 10.3109/02713689609007621

Keywords: dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD), sodium iodate, taurine, oxidative stress, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), retinal thickness

Citation: Attia M, Pavlovic T, Muliawan A, Tuya F, Mihalatos M, Iwanicki M and Kang-Mieler J (2025) Therapeutic potential of taurine in a pigmented rat model of age-related macular degeneration. Front. Ophthalmol. 5:1701761. doi: 10.3389/fopht.2025.1701761

Received: 09 September 2025; Accepted: 14 November 2025; Revised: 01 November 2025;

Published: 01 December 2025.

Edited by:

Lucia Gozzo, University of Catania, ItalyReviewed by:

Jeffrey Boatright, Emory University, United StatesShaojun Wang, People’s Liberation Army General Hospital, China

Copyright © 2025 Attia, Pavlovic, Muliawan, Tuya, Mihalatos, Iwanicki and Kang-Mieler. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jennifer Kang-Mieler, amthbmdtaWVAc3RldmVucy5lZHU=

Mohammed Attia

Mohammed Attia Tonja Pavlovic2

Tonja Pavlovic2 Marcin Iwanicki

Marcin Iwanicki