Abstract

Purpose:

To investigate the microbial profiles in the retina and RPE/choroid, and how they respond to retinal injury.

Methods:

Adult C57BL/6J mice were subjected to retinal laser burns using a photocoagulator. One and 24h later, the retina and RPE/choroid were collected under strict sterile conditions and processed for 16S rRNA paired-end sequencing (2×250). The data were analyzed using R software, GraphPad Prism, OmicShare, and Wekemo Bioincloud.

Results:

Microbiota were detected in the retina and RPE/choroid under normal physiological conditions. The alpha diversity was higher in the retina than in the RPE/choroid. All retinal microbiotas at the phylum level and 12 out of 14 at the genus level were shared with those of RPE/choroid. The top phyla were Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria. Retinal laser injury reduced the alpha diversity but did not affect beta diversity. In the RPE/choroid, the abundance of Actinomyces and Roseburia decreased, and the abundance of Lactobacillus increased significantly after laser injury. The abundance of Sphingomonas in the retina decreased, and the abundance of Faecalibacterium and Bifidobacterium increased (P<0.05) after laser injury in the retina. Faecalibacterium and Bifidobacterium are positively linked to Th17/IL-17 signaling and RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathways, as well as antigen processing and presentation.

Conclusions:

The neuroretina and RPE/choroid have diverse microbiomes under normal conditions. Their richness and evenness are relatively stable in the retina compared to those in the RPE/choroid. Retinal laser injury enriches Faecalibacterium and Bifidobacterium in ocular tissues, and these microbiotas may participate in retinal wound healing through modulating inflammation.

1 Introduction

The human body harbors trillions of commensal bacteria that have coevolved with the host, constituting a functionally integrated ecosystem that is now under active investigation (1). Gut dysbiosis, characterized by altered microbial diversity and richness, drives the pathogenesis of metabolic disorders, autoimmunity, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegeneration (2–5). Growing evidence links gut dysbiosis to ocular pathologies, including age-related macular degeneration (AMD), uveitis, diabetic retinopathy (DR), and glaucoma (6–9). For instance, fecal samples from AMD patients exhibit enrichment of Anaerotruncus, Oscillibacter, Ruminococcus torques, and Eubacterium ventriosum (10), and a higher ratio of Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (11). In primary open-angle glaucoma, increased abundance of Prevotellaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, and Escherichia coli established causal links to optic neurodegeneration (12). Beyond the gut, next-generation sequencing has revealed microbial communities on the ocular surface and within intraocular tissues (13). Dysbiosis of these communities has been linked to keratitis (14, 15), dry eye disease (16), and keratoconus (13). Mechanistically, microbiota imbalance may contribute to the pathogenesis of human disease through modulating immune response either systemically or locally within the disease tissue (17–19).

Apart from the body surface (skin and mucosal surfaces), microbes have also been detected in body fluids, including blood (20, 21), cerebrospinal fluid (22, 23), and intraocular fluid (24) from healthy and diseased individuals. Emerging evidence suggests that microbes also exist inside the tissues, such as the brain, in people with Alzheimer’s disease (25), the retina of WT and diabetic (Akita) mice (26), the placenta (27), and the breast tissue (28, 29). The mammalian eye has long been considered an immune-privileged organ, anatomically and functionally protected from microbial colonization by physical barriers, i.e., the blood-retinal barrier (BRB) and local immune regulatory mechanisms (30). However, emerging evidence challenges this dogma, suggesting that even highly specialized tissues, such as the retina, may harbor microbial communities (26). The intraocular microbiome may modulate retinal immune response and participate in disease development (31, 32). We previously reported that retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells and vascular endothelial cells express high levels of an antimicrobial peptide (AMP), lysozyme, which may protect the retina from blood-borne pathogens (33, 34). The concept of a tissue-associated microbiome has transformed our understanding of immune regulation, metabolic homeostasis, and disease susceptibility in organs such as the gut, skin, and lung (35–39). Yet, the presence and role of microbial populations in the retina and choroid and their responses to retinal injury remain largely unexplored.

Understanding whether a local microbiome exists in the posterior eye segment and its potential function is of considerable significance. The retina and choroid are highly vascularized and metabolically active tissues that maintain a delicate balance between immune tolerance and activation. Perturbations in this balance are implicated in major blinding diseases such as AMD and DR. If local microbial populations contribute to immune homeostasis or metabolic signaling, their alteration could represent a previously unrecognized driver of retinal pathology.

Here, we characterized the microbial profiles in the retina and RPE/choroid using 16S rRNA sequencing and further investigated their response to retinal laser injury. We found that both tissues harbor diverse microbiomes under normal conditions, and that the microbial profile is rapidly altered after injury.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Animals

C57BL/6J mice (6–8 weeks of age) were purchased from SJA Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. (Changsha, Hunan, China), housed under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions with a 12/12 h light-dark cycle and libitum access to standard chow and water. All experimental protocols complied with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and received ethical approval from the Animal Care and Use Committee of AIER Eye Institute (Approval ID: AEI20230048).

2.2 Induction of retina injury

We used retinal laser burns as a retinal injury model. The animals were anesthetized with isoflurane using an inhalation system. Induction was performed with 3–4% isoflurane in oxygen, followed by maintenance at 1.5–2% isoflurane. The depth of anesthesia was monitored throughout the procedure. Pupils were dilated with 0.5% tropicamide/phenylephrine (Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). Ocular surface hydration was maintained with carboxymethylcellulose sodium (Allergan Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Dublin, Ireland). Four laser burns (200 mW, 100 ms, 60 μm spot) were applied 2 optic disc diameters away from the optic nerve head using a 532-nm photocoagulator (Topcon, Tokyo, Japan) as detailed in previous studies (40–42).

2.3 Tissue collection for 16S rRNA analysis

At the end of the experiment, animals were euthanized using a carbon dioxide (CO2) chamber, followed by cervical dislocation to confirm death, in accordance with institutional and international ethical guidelines. Retina and RPE/choroid were collected from normal non-lasered, 1h, and 24h post-laser injury mice (n = 8 mice per group). Mice that underwent anesthesia without retinal injury served as controls. All procedures were performed under Class II biosafety cabinet conditions. The eyeballs were enucleated under sterile conditions and treated immediately with 10% betadine for 3 min, followed by thorough washes with 70% ethanol and irrigation with sterile saline. Sterile cotton swabs were utilized to sample the globe surface before and after the globe cleaning procedure for 16S rRNA analysis as procedure controls. The globes were dissected with autoclaved instruments. The anterior segment was removed, and the retina and RPE/choroid were collected using sterile forceps, placed into nuclease-free vials, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −800C for 16S rRNA sequencing. Additionally, 10% betadine, 70% ethanol, sterile saline, and lysis buffer were subjected to 16S rRNA sequencing as extraction and PCR amplification controls. Mixtures of the known bacteria Akkermansia muciniphila and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii were used as positive controls.

2.4 DNA extraction and polymerase chain reaction amplification

Genomic DNA isolation was performed using the QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Cat: 51504, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. For microbial community profiling, the V3-V4 hypervariable segments of bacterial 16S rRNA genes were amplified with universal primers 341F: CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG and 806R: GGACTACHVGGGTATCTAAT incorporated with sample-specific barcodes (8-nt length). The PCR products were purified (Axygen Biosciences, Silicon Valley, USA), and quantified fluorometrically (QuantiFluor-ST, Promega, Madison, USA). Equimolar concentrations of purified amplicons were combined with Illumina-based paired-end sequencing (250 bp read length). The raw reads from the mouse retina and RPE/choroid have been deposited in the NCBI SRA database (access code PRJNA1158449).

2.5 Bioinformatics and statistical analysis of 16S-rRNA sequencing data

Sequence data underwent stringent quality control, excluding reads with >10% ambiguous bases (N) or <80% high-quality bases (Q≥20). Paired-end reads were assembled into preliminary tags via FLASH (v1.2.11; 10bp overlap threshold, 2% mismatch tolerance). Subsequent noise reduction was performed using QIIME (v1.9.1) to obtain refined sequences. For Amplicon Sequence Variant (ASV) construction, demultiplexed raw data (demux plugin) underwent adapter trimming (cutadapt) before DADA2-based processing (quality filtering, denoising, read merging, and chimera elimination). Taxonomic classification was executed in QIIME2 with reference to SILVA (16S/18S) and UNITE (ITS) databases. Taxon abundances were computed via custom Perl scripts and rendered graphically in SVG format.

2.6 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted in GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA), with significance thresholds set at p<0.05. Microbial alpha diversity was evaluated via six ecological metrics (species richness estimators: Chao1/ACE; diversity indices: Shannon/Simpson; sequencing depth: Good-coverage) processed through QIIME2, with subsequent visualizations created in R. Beta diversity patterns were examined through PCoA based on Jaccard and unweighted UniFrac distance matrices, complemented with functional prediction via PICRUSt2, all implemented within the R environment.

For graphical representations, comparative analyses (bar plots, Venn diagrams) and microbial abundance heatmaps were constructed using OmicShare’s web-based tools (https://www.omicshare.com/tools). Interaction networks were modeled via Wekemo Bioincloud (https://www.bioincloud.tech). Non-parametric comparisons across groups were conducted using the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s post-hoc correction. Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± SD.

3 Results

3.1 Microbial composition in the retina and RPE/choroid under normal conditions

Microbial 16S rRNA (V3-V4) high-throughput sequencing revealed the presence of numerous microbial taxa in the retina and RPE/choroid (n = 8). Rarefaction curves indicated adequate sequencing depth for microbial diversity capture (Supplementary Figure S1A). 16S DNA agarose gel electrophoresis showed clear DNA products from the retina and RPE/choroidal samples in all groups (Supplementary Figure S1B). The control samples, including sterile cotton swabs sampled before and after cleaning the global surface, lysis buffer, 10% betadine, sterile saline, and ethanol used for cleaning the global, did not show any bands in agarose gel electrophoresis (Supplementary Figure S1B). The results suggest that the microbial taxa detected in the retina and RPE/choroid were not due to contamination from sample preparations.

Under normal conditions, a total of 7 and 8 phyla and 14 and 18 genera were identified from the retina and RPE/choroid, respectively. The top three phyla were Proteobacteria (relative abundances: retina = 34.9%, RPE/choroid = 30.5%), Firmicutes (relative abundances: retina = 30.2%, RPE/choroid = 27.7%), and Actinobacteria (relative abundances: retina = 20.4%, RPE/choroid = 19.4%) (Figures 1A, B). The top three genera were Sphingomonas, Faecalibacterium, and Collinsella in the retina (relative abundance: 29.7%, 6.0%, 5.7%), Sphingomonas, Bifidobacterium, and Akkermansia in the RPE/choroid (relative abundance: 25.7%, 7.2%, 6.3%) (Figures 1C, D).

Figure 1

Taxonomic profiling and diversity metrics in healthy retina and RPE/choroid. (A, B) Bar plot depicting the taxonomic composition at the phylum level in the retina (A) and RPE/choroid (B). (C, D) Bar plot depicting the taxonomic composition at the genus level in the retina (C) and RPE/choroid (D). Microbial taxa were determined using the criteria of presence in >50% of the samples and an average abundance above 1% across all samples. n=8. (E) Box plots showing the α-diversity, specifically, the Chao1, se.Ace, and Shannon indices in different samples. Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. (F) PCoA elucidates the similarities and differences between different healthy samples. (G, H) The number of unique or shared microbiota at the level of phylum (G) and genus (H) between two healthy tissues. Overlapping areas show the number of shared microbiotas.

Although the retina exhibits higher alpha diversity (Chao1/se.Ace index) than the RPE/choroid (Figure 1E), the difference is not statistically significant, indicating potentially a greater microbial community resilience. The beta diversity showed no significant difference between the two tissues (Figure 1F), suggesting similar overall taxonomic composition. Indeed, all retinal microbiotas at the phylum level (Figure 1G) and 12 out of 14 at the genus level (Figure 1H) are shared with those of RPE/choroid. The shared microbiotas at the genus level include Sphingomonas, Faecalibacterium, Bifidobacterium, Unkn. Clostridia(c), Akkermansia, Blautia, Bacteroides, Clostridium, Unkn. Eubacteriales(o), Unkn. Actinobacteria(p), Methylobacterium, and Unkn. Bacteroidaceae(f). The relative abundance of these shared microbiotas did not differ between the retina and the RPE/choroid.

Our results suggest the presence of microbiota in RPE/choroid and the neuronal retina, and the microbial composition is similar between the two tissues.

3.2 Retinal injury alters microbial profiles and composition

To understand the microbial response to retinal injury, we profiled microbiota in the retina and RPE/choroid at 1h and 24h post-injury using 16S rRNA sequencing (Figure 2A). The α-diversity of the retinal samples showed no significant changes after laser injury compared with the sham-operated group (Figure 2B). Interestingly, the se.Chao1 index revealed a significant increase in α-diversity in RPE/choroid samples at 24h compared to 1h post-laser injury (Figure 2C). The β-diversity showed no significant differences in the retina and RPE/choroid at different times after laser injury (Figures 2D, E). Our results suggest that retinal laser injury had a limited impact on the richness and evenness of intraocular microbiota within 24 h.

Figure 2

Distribution of microbiota in the retina and RPE/choroid following retinal laser injury. (A) Diagram showing the experimental design. Mice were treated with retinal laser burns. Retina and RPE/choroid were collected at 1h and 24h later. The difference of α-diversity in the retina (B) and RPE/choroid (C) at different times post-laser injury. *p<0.05, n=8. Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. Retinal laser injury-induced PCoA changes in the retina (D) and RPE/choroid (E) at different times post-laser injury.

The taxonomy of each tissue at different times was assessed independently at the phylum and genus levels. At the phylum level, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Verrucomicrobia were enriched in all tissues (Figures 3A, B). The abundance of Actinobacteria was significantly increased in the retina at 24h compared to 1h post-laser injury (p = 0.04, Figure 3C). No significant change was detected in the RPE/choroid.

Figure 3

Alterations in the composition and relative abundance of tissue microbiota after retinal injury. Top 10 Taxonomic distributions of bacteria at the phylum level in the retina (A) and RPE/choroid (B) at different times after retinal injury. (C) Heatmaps showing altered microbiota in the retina at different times post-retinal injury at the phylum level. Taxonomic distributions of bacteria at the genus level in the retina (D) and RPE/choroid (E) at different times after retinal injury. (F) Shifts at the genus-level microbiota in the RPE/choroid at different times after retinal injury.

At the genus level, the retina and RPE/choroid exhibited a high abundance of Sphingomonas, Faecalibacterium, and Bifidobacterium (Figures 3D, E). The abundance of Sphingomonas decreased over time after laser injury (Figures 3D, E). In the RPE/choroid, the abundance of Actinomyces and Roseburia decreased, while Lactobacillus increased significantly after laser injury (Figure 3F). No significant change was detected in the retina.

Next, we examined the shared and unique microbiota at different timepoints from the same tissue (present in at least 50% of the samples and average abundance ≥ 1%). A total of 7 phyla and 19 genera were identified in the retina. All phyla (Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Verrucomicrobia, Cyanobacteria, and Unkn. Bacteria(k)) and 8 (Bifidobacterium, Faecalibacterium, Collinsella, Blautia, Akkermansia, Sphingomonas, Unkn. Clostridia(c), and Unkn. Bacteria(k)) out of 19 genera were shared by samples from different times (Figures 4A, B). Three genera (Unkn. Alphaproteobacteria(c), Acetilactobacillus, Lachnoclostridium) exclusively present in the retinas from 1h post-laser injury (Figure 4B), suggesting a rapid microbial alteration.

Figure 4

The shared and unique microbiota in the retina and RPE/choroid with/without retinal laser injury. (A-D) Venn analysis of the shared microbiota at different times. Overlapping areas show the number of shared microbiotas. (A, B) The number of shared or unique microbiota at the level of phylum (A) and genus (B) in the retina at different times. (C, D) The number of shared or unique microbiota at the level of phylum (C) and genus (D) in RPE/choroid at different times. (E-H) Venn analysis of the shared microbiota at different tissues. (E-F) The number of shared or unique microbiota in the level of phylum between retina and RPE/choroid at 1h (E) and 24h (F) post-retinal laser injury. (G-H) The number of shared or unique microbiota at the genus level between retina and RPE/choroid at 1h (G) and 24h (H) post-retinal laser injury.

Eight phyla and 23 genera were detected in the RPE/choroid. Six phyla (Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Verrucomicrobia, and Cyanobacteria) and 8 genera (Sphingomonas, Bifidobacterium, Akkermansia, Faecalibacterium, Clostridium, Unkn. Clostridia(c), Unkn. Bacteroidaceae(f), and Prevotella) were shared by samples from different times (Figures 4C, D). One (Methylobacterium) and 4 (Lactobacillus, Collinsella, Ruminococcus, Unkn. Cyanobacteria(c)) were unique to 1h and 24h samples, respectively (Figures 4C, D).

We further identified 6 shared microbiotas (Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Cyanobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Verrucomicrobia, and Actinobacteria) between the retina and RPE/choroid at the phylum level (Figures 4E, F) at 1h and 24h post-retinal injury. At the genus level, we identified 6 shared microbiotas (Bifidobacterium, Faecalibacterium, Akkermansia, Prevotella, Sphingomonas, Unkn. Clostridia(c)) at 1h post-retinal injury and 9 shared microbiotas (Bifidobacterium, Faecalibacterium, Collinsella, Blautia, Akkermansia, Unkn. Clostridia(c), Prevotella, and Sphingomonas) at 24h (Figures 4G, H). The number of shared microbiotas in the two tissues significantly decreased after retinal injury at the genus level (Figures 4E–H, compared with those under normal conditions, Figures 1E, F).

The presence of numerous shared microbiotas between the retina and RPE/choroid and at different times after laser injury indicates potential functional and compositional interdependence across these ocular regions under different conditions.

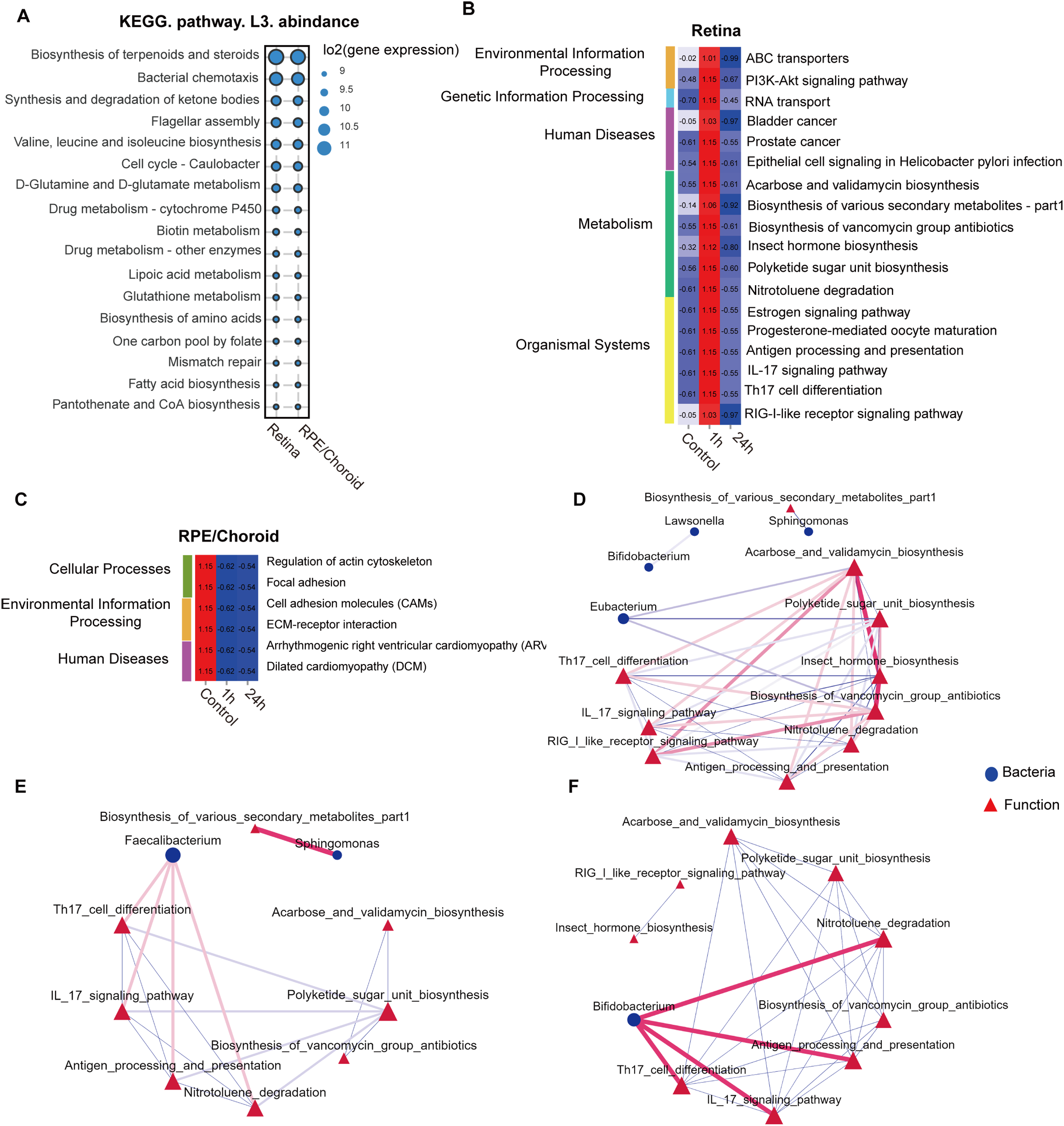

3.3 Predicted pathways of microbiome with and without retinal laser injury

To understand the biological significance of the retinal and RPE/choroidal microbiota, we employed the PICRUSt2 platform to predict microbial functions. KEGG level 3 analysis revealed that, under normal conditions, pathways related to biosynthesis of terpenoids and steroids and bacterial chemotaxis were enriched in both retina and RPE/choroid (Figure 5A). At 1h post-laser injury, 18 pathways were significantly upregulated in the retina, including 6 metabolism pathways and 4 immune system-related pathways (antigen processing and presentation; IL-17 signaling pathway; RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway; Th17 cell differentiation) (Figure 5B). In contrast, six pathways were significantly downregulated in the RPE/choroid after injury (Figure 5C), encompassing functional associations with environmental and genetic information processing, human diseases, metabolism, organismal systems, and cellular processes (Figures 5B, C).

Figure 5

Retinal injury-induced changes in the predicted microbiota functional pathways. (A) Top 15 average abundance of KEGG level-3 pathways in the retina, RPE/choroid and feces under normal conditions. KEGG level-3 pathways at different times in the retina (B) and RPE/choroid (C). (D-F) Network analysis of the link of bacteria communities (top 30 genera) with the predicted pathways in the retina under normal conditions (D), 1h (E), and 24h after retinal laser injury (F). The red line between nodes indicates a positive correlation, and the blue line between nodes indicates a negative correlation. The size of the nodes represents the degree of a genus of bacteria or KEGG-level 3 pathways.

Network analysis revealed that Eubacterium exhibited negative correlations with the biosynthesis of acarbose, validamycin, polyketide sugar unit, and vancomycin group antibiotics under normal conditions. Notably, acarbose/validamycin and vancomycin group antibiotics were positively associated with Th17 cell differentiation, IL-17 signaling, RIG-like-receptor signaling, and antigen processing/presentation (Figure 5D). Sphingomonas, which was detected in all tissues (Figure 1) and decreased following retinal injury (Figure 3), was negatively correlated with biosynthesis of various secondary metabolites under normal conditions; however, these associations became positive 1h after laser injury (Figures 5D, E). In addition, Faecalibacterium and Bifidobacterium, both abundant in the retina and RPE/choroid irrespective of injury, demonstrated positive associations with Th17 cell differentiation, IL-17 signaling pathway, antigen processing and presentation, and nitrotoluene degradation at both 1h and 24h after laser injury (Figures 5E, F).

Our results suggest that the intraocular microbiota might contribute to retinal health and disease by regulating the biosynthesis and degradation of molecules essential for tissue metabolism and immune function.

4 Discussion

Compelling evidence suggests that gut/mucus/skin microbiomes can affect human health by modulating systemic or tissue-level inflammation through metabolic products or by generating a plasma microbiome. The plasma microbiome can directly modulate circulating immune cell activation or migrate into tissues, altering the tissue microenvironment. In this study, we demonstrated the existence of microbiota in healthy retina and RPE/choroid. Many taxa are shared by the two tissues, suggesting potential functional and compositional connections across these regions. Pathway prediction revealed a potential contribution of microbiota to ocular health by maintaining metabolic balance (e.g., amino acid biosynthesis). We found that retinal laser injury altered the ocular microbial profile, and these changes can result in the upregulation of pathways associated with the biosynthesis of sugar molecules, antibiotics, and molecules related to immune function.

Previously, Deng et al. showed that aqueous humor from healthy donors harbors a unique microbiome with diverse compositions and functions (24). The authors further showed that the bacteria could be visualized by transmission electron microscopy and cultured in anaerobic conditions (24), suggesting the existence of live symbiotic bacteria inside the aqueous compartment of the human eye. Here, we detected diverse microbial compositions in the mouse retina and RPE/choroid under normal physiological conditions by 16S rRNA sequencing. We tried to culture the microbiota without any success. The top three phyla were Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria. Our results are in line with previous studies, whereby the authors reported the presence of a similar microbial signature in healthy mouse retina (26, 43). We found that the retina has higher microbial alpha diversity, indicating a stable microbial ecosystem. We previously showed that RPE cells (key cells of the outer BRB) express a variety of antimicrobial peptides (33, 34), which could restrict the entry of microorganisms from the blood circulation or the choroid into the retina. The relatively stable retinal microbial ecosystem may be related to BRB antimicrobial function and its immune-privileged nature.

Exactly how the symbiotic bacteria enter the eye remains elusive. Microbiota and their components can be carried by immune cells, such as neutrophils (44), macrophages (45) and monocytes (46) in free form from the blood or body surface (e.g., skin, mucosa, and gastrointestinal tract) to tissues, impacting local immune reactions and disease development (24, 47). Certain bacteria may also reside within autophagosomes in phagocytes and migrate to various body sites (47). Additionally, microorganisms may reside in neurons. For example, the herpes simplex virus can establish latency in the host trigeminal ganglion by remaining dormant and can be periodically reactivated under stress or immunosuppressive conditions (48). Under disease conditions, live bacteria can translocate from the gut to the eye and contribute to retinal degeneration (43). Nonetheless, the microbial beta diversity between the retina and RPE/choroid is similar, and most of the retinal taxonomic composition is shared with the RPE/choroid. This suggests that the retinal microbiome may originate from the RPE/choroid.

Upon retinal injury, the composition of the retina and RPE/choroidal microbiota changed rapidly and significantly (Figure 3). We recently reported that retinal injury could induce rapid changes in the gut, including altered gut microbial composition, disrupted gut epithelial barrier function, and circulating innate immune cell activation (49). This “retina-gut” axis can then feed back to the retinal wound healing process through the “gut-retina” axis (49). We found that laser injury increased the abundance of retinal Actinobacteria (Figure 3), which was significantly reduced in the gut after laser injury in our previous study (49). The laser-induced leaky gut may affect the circulating microbiome, which can then enter the RPE/choroid and retina through the damaged ocular barrier in the laser-treated eyes. These changes may modulate innate immune cell activation and contribute to retinal wound healing.

The biological significance of the ocular microbiome in retinal health remains elusive. Members of the Actinobacteria phylum, particularly Bifidobacterium spp., can synthesize the short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) exhibiting immunomodulatory effects (50–52). Lactobacillus were the dominant genus in the luteolin, which could alleviate DSS-induced colitis in rats (53). The abundance of ocular Actinobacteria and Lactobacillus increased after laser injury (Figure 3F), and both are crucially involved in immune regulation. Previous studies reported a significant reduction in their abundance in chronic conditions, such as type 2 diabetes (54) and obesity (55), and this reduction is believed to play a role in disease progression. The laser-induced alteration of the microbiota may be the body’s attempt to repair retinal injury. This is supported by our functional analysis, which shows that the altered microbiota affects the biosynthesis of antibiotics, the PI3K-Akt signaling, and immune-related pathways such as Th17/IL-17 signaling, RIG-I-like receptor signaling, and antigen processing and presentation (Figure 5B). The predicted immune-related pathways are linked with Faecalibacterium and Bifidobacterium (Figures 5E, F), which were increased after retinal injury. Faecalibacterium (i.e., Faecalibacterium prausnitzii) has therapeutic potential in multiple diseases, including colitis (56), tumor (57), and atherosclerosis (58). They may participate in retinal wound healing through immune regulation.

Our results challenge the traditional assumption of ocular sterility by demonstrating the presence of microbiota in the retina and RPE/choroid, and their dynamic changes in disease conditions. The ocular tissue microbiome may be an additional player in the pathophysiology of retinal diseases. Further studies will be needed to determine the specific microbial profiles in each retinal disease condition. Such information will not only help uncover disease mechanisms but also develop personalized therapies (e.g., probiotics or antimicrobial peptides).

This study has several limitations. First, 16S rRNA sequencing of retina and RPE/choroidal microbiota constrained taxonomic resolution and precluded functional or quantitative microbial assessment. Second, despite extensive culturing attempts, retinal microbial viability remains undetermined. Third, the observed microbial shifts were not functionally validated. Further shotgun metagenomics may help identify species and strain-level microbes and reveal the functional potential of the microbiota. Finally, while sex differences in certain retinal diseases are well-documented (59–61) we used only males in the study. Whether the microbiota in female mice responds differently to retinal injury remains to be elucidated. Future studies will include female mice and human samples to enhance translational relevance and assess sex-specific microbiome responses. Furthermore, additional investigations are needed to elucidate the pathophysiological significance of retinal and RPE/choroidal microbiome in ocular disorders.

5 Conclusions

In summary, our study shows that the microbiome constitutes the retinal and RPE/choroidal ecosystem under normal physiological conditions, where it may contribute to the biosynthesis and metabolism of molecules essential for ocular homeostasis. Upon retinal injury, the microbial composition changes rapidly. These shifts might modulate retinal metabolism and intraocular immune response, thereby participating in retinal wound healing, although experimental evidence will be needed to establish the causality. A deeper understanding of the composition and function of intraocular microbiota across various disease states will help to develop better strategies to prevent or treat sight-threatening retinal diseases.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Animal Care and Use Committee of AIER Eye Institute. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

XC: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JQ: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. CY: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft. JL: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. XY: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. WD: Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft. HX: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. Supported by Science Research Foundation of Aier Eye Hospital Group (AIM2301D02), Hunan Provincial Innovation Platform and Specialist Program of Foreign Experts Fund (2022WZ1023), Hunan Provincial Natural Science Fund (2023JJ70047), Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2025JJ90270); Science Research Foundation of Aier Eye Hospital Group (AMF2501D03).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fopht.2025.1719090/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1Data quality control (A) Rarefaction curves (Sobs index) of the gut microbiota. (B) 16S DNA agarose gel electrophoresis of all samples. RH: retina tissue under normal condition; R1: 1h after laser injury (retina); R24: 24h after laser injury (retina); CH: RPE/choroid tissue under normal condition; C1: 1h after laser injury (RPE/choroid); C24: 24h after laser injury (RPE/choroid); 1-3:sterile cotton swabs sampled from the globe surface before cleaning procedure; 4-5,17:sterile cotton swabs sampled from the globe surface after cleaning procedure; 6-7: lysis buffer; 8-10: 10% betadine; 11-13: sterile saline; 14-16: 70% ethanol. 18-20: positive control.

Abbreviations

AMD, Age-related macular degeneration; AMP, Antimicrobial Peptide; ASV, Amplicon Sequence Variant; PCoA, Principal Coordinate Analysis; RIG-I-like receptor, Retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors; RPE, Retinal pigment epithelial.

References

1

Baquero F Nombela C . The microbiome as a human organ. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2012) 18 Suppl 4:2–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03916.x.

2

Zhang Y Wang T Wan Z Bai J Xue Y Dai R et al . Alterations of the intestinal microbiota in age-related macular degeneration. Front Microbiol. (2023) 14:1069325. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1069325

3

Parker A Romano S Ansorge R Aboelnour A Le Gall G Savva GM et al . Fecal microbiota transfer between young and aged mice reverses hallmarks of the aging gut, eye, and brain. Microbiome. (2022) 10:68. doi: 10.1186/s40168-022-01243-w

4

Huang L Hong Y Fu X Tan H Chen Y Wang Y et al . The role of the microbiota in glaucoma. Mol Aspects Med. (2023) 94:101221. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2023.101221

5

Erny D Hrabe de Angelis AL Jaitin D Wieghofer P Staszewski O David E et al . Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat Neurosci. (2015) 18:965–77. doi: 10.1038/nn.4030

6

Xue W Li JJ Zou Y Zou B Wei L . Microbiota and ocular diseases. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2021) 11:759333. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.759333

7

Ye Z Zhang N Wu C Zhang X Wang Q Huang X et al . A metagenomic study of the gut microbiome in Behcet’s disease. Microbiome. (2018) 6:135. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0520-6

8

Campagnoli LIM Varesi A Barbieri A Marchesi N Pascale A . Targeting the gut-eye axis: an emerging strategy to face ocular diseases. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:13338. doi: 10.3390/ijms241713338

9

Zhang H Mo Y . The gut-retina axis: a new perspective in the prevention and treatment of diabetic retinopathy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2023) 14:1205846. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1205846

10

Zysset-Burri DC Keller I Berger LE Largiader CR Wittwer M Wolf S et al . Associations of the intestinal microbiome with the complement system in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. NPJ Genom Med. (2020) 5:34. doi: 10.1038/s41525-020-00141-0

11

Xue W Peng P Wen X Meng H Qin Y Deng T et al . Metagenomic sequencing analysis identifies cross-cohort gut microbial signatures associated with age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Visual Sci. (2023) 64:11. doi: 10.1167/iovs.64.5.11

12

Krilis M Fry L Ngo P Goldberg I . The gut microbiome and primary open angle glaucoma: Evidence for a ‘gut-glaucoma’ axis? Eur J Ophthalmol. (2024) 34:924–30. doi: 10.1177/11206721231219147

13

Rocha-de-Lossada C Mazzotta C Gabrielli F Papa FT Gomez-Huertas C Garcia-Lopez C et al . Ocular surface microbiota in naive keratoconus: A multicenter validation study. J Clin Med. (2023) 12:6354. doi: 10.3390/jcm12196354

14

Borroni D Bonzano C Sanchez-Gonzalez JM Rachwani-Anil R Zamorano-Martin F Pereza-Nieves J et al . Shotgun metagenomic sequencing in culture negative microbial keratitis. Eur J Ophthalmol. (2023) 33:1589–95. doi: 10.1177/11206721221149077

15

Schiano-Lomoriello D Abicca I Contento L Gabrielli F Alfonsi C Di Pietro F et al . Infectious keratitis: characterization of microbial diversity through species richness and shannon diversity index. Biomolecules. (2024) 14:389. doi: 10.3390/biom14040389

16

Moon J Yoon CH Choi SH Kim MK . Can gut microbiota affect dry eye syndrome? Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:8443. doi: 10.3390/ijms21228443

17

Kawano Y Edwards M Huang Y Bilate AM Araujo LP Tanoue T et al . Microbiota imbalance induced by dietary sugar disrupts immune-mediated protection from metabolic syndrome. Cell. (2022) 185:3501–19 e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.08.005

18

Yan F Zhang Q Shi K Zhang Y Zhu B Bi Y et al . Gut microbiota dysbiosis with hepatitis B virus liver disease and association with immune response. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2023) 13:1152987. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1152987

19

Honarpisheh P Bryan RM McCullough LD . Aging microbiota-gut-brain axis in stroke risk and outcome. Circ Res. (2022) 130:1112–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.122.319983

20

Panaiotov S Hodzhev Y Tsafarova B Tolchkov V Kalfin R . Culturable and non-culturable blood microbiota of healthy individuals. Microorganisms. (2021) 9:1464. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9071464

21

Manfredo Vieira S Hiltensperger M Kumar V Zegarra-Ruiz D Dehner C Khan N et al . Translocation of a gut pathobiont drives autoimmunity in mice and humans. Science. (2018) 359:1156–61. doi: 10.1126/science.aar7201

22

Pandey S Whitlock KB Test MR Hodor P Pope CE Limbrick DD Jr. et al . Characterization of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) microbiota at the time of initial surgical intervention for children with hydrocephalus. PloS One. (2023) 18:e0280682. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0280682

23

Ghose C Ly M Schwanemann LK Shin JH Atab K Barr JJ et al . The virome of cerebrospinal fluid: viruses where we once thought there were none. Front Microbiol. (2019) 10:2061. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02061

24

Deng Y Ge X Li Y Zou B Wen X Chen W et al . Identification of an intraocular microbiota. Cell Discov. (2021) 7:13. doi: 10.1038/s41421-021-00245-6

25

Zhao C Kuraji R Ye C Gao L Radaic A Kamarajan P et al . Nisin a probiotic bacteriocin mitigates brain microbiome dysbiosis and Alzheimer’s disease-like neuroinflammation triggered by periodontal disease. J Neuroinflamm. (2023) 20:228. doi: 10.1186/s12974-023-02915-6

26

Prasad R Asare-Bediko B Harbour A Floyd JL Chakraborty D Duan Y et al . Microbial signatures in the rodent eyes with retinal dysfunction and diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2022) 63:5. doi: 10.1167/iovs.63.1.5

27

Pelzer E Gomez-Arango LF Barrett HL Nitert MD . Review: Maternal health and the placental microbiome. Placenta. (2017) 54:30–7. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2016.12.003

28

Zhu J Wu J Liang Z Mo C Qi T Liang S et al . Interactions between the breast tissue microbiota and host gene regulation in nonpuerperal mastitis. Microbes Infect. (2022) 24:104904. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2021.104904

29

Papakonstantinou A Nuciforo P Borrell M Zamora E Pimentel I Saura C et al . The conundrum of breast cancer and microbiome - A comprehensive review of the current evidence. Cancer Treat Rev. (2022) 111:102470. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2022.102470

30

Forrester JV Xu H . Good news-bad news: the Yin and Yang of immune privilege in the eye. Front Immunol. (2012) 3:338. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00338

31

Xu H Chen M . Immune response in retinal degenerative diseases - Time to rethink? Prog Neurobiol. (2022) 219:102350.

32

Xu H Rao NA . Grand challenges in ocular inflammatory diseases. Front Ophthalmol (Lausanne). (2022) 2:756689. doi: 10.3389/fopht.2022.756689

33

Liu J Yi C Ming W Tang M Tang X Luo C et al . Retinal pigment epithelial cells express antimicrobial peptide lysozyme - A novel mechanism of innate immune defense of the blood-retina barrier. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2021) 62:21. doi: 10.1167/iovs.62.7.21

34

Liu J Yi C Qi J Cui X Yuan X Deng W et al . Senescence alters antimicrobial peptide expression and induces amyloid-beta production in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Aging Cell. (2025) 24:e70161. doi: 10.1111/acel.70161

35

Ananthakrishnan AN Whelan K Allegretti JR Sokol H . Diet and microbiome-directed therapy 2.0 for IBD. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2025) 23:406–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.05.049

36

Danne C Skerniskyte J Marteyn B Sokol H . Neutrophils: from IBD to the gut microbiota. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2024) 21:184–97. doi: 10.1038/s41575-023-00871-3

37

Chen Y Knight R Gallo RL . Evolving approaches to profiling the microbiome in skin disease. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1151527. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1151527

38

Natalini JG Singh S Segal LN . The dynamic lung microbiome in health and disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. (2023) 21:222–35. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00821-x

39

Wang L Cai Y Garssen J Henricks PAJ Folkerts G Braber S . The bidirectional gut-lung axis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2023) 207:1145–60. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202206-1066TR

40

Badia A Duarri A Salas A Rosell J Ramis J Gusta MF et al . Repeated topical administration of 3 nm cerium oxide nanoparticles reverts disease atrophic phenotype and arrests neovascular degeneration in AMD mouse models. ACS Nano. (2023) 17:910. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.2c05447

41

Zhao M Xie W Hein TW Kuo L Rosa RH Jr. Laser-induced choroidal neovascularization in rats. Methods Mol Biol. (2021) 2319:77–85. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-1480-8_9

42

Lambert V Lecomte J Hansen S Blacher S Gonzalez ML Struman I et al . Laser-induced choroidal neovascularization model to study age-related macular degeneration in mice. Nat Protoc. (2013) 8:2197–211. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.135

43

Peng S Li JJ Song W Li Y Zeng L Liang Q et al . CRB1-associated retinal degeneration is dependent on bacterial translocation from the gut. Cell. (2024) 187:1387–401 e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.01.040

44

Voyich JM Braughton KR Sturdevant DE Whitney AR Said-Salim B Porcella SF et al . Insights into mechanisms used by Staphylococcus aureus to avoid destruction by human neutrophils. J Immunol. (2005) 175:3907–19. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3907

45

Kubica M Guzik K Koziel J Zarebski M Richter W Gajkowska B et al . A potential new pathway for Staphylococcus aureus dissemination: the silent survival of S. aureus phagocytosed by human monocyte-derived macrophages. PloS One. (2008) 3:e1409. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001409

46

Schlesinger LS . Entry of Mycobacterium tuberculosis into mononuclear phagocytes. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. (1996) 215:71–96.

47

O’Keeffe KM Wilk MM Leech JM Murphy AG Laabei M Monk IR et al . Manipulation of autophagy in phagocytes facilitates staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection. Infect Immun. (2015) 83:3445–57. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00358-15

48

Patil CD Suryawanshi RK Kapoor D Shukla D . Postinfection metabolic reprogramming of the murine trigeminal ganglion limits herpes simplex virus-1 replication. mBio. (2022) 13:e0219422. doi: 10.1128/mbio.02194-22

49

Cui X Yi C Liu J Qi J Deng W Yuan X et al . The gut microbial system responds to retinal injury and modulates the outcomes by regulating innate immune activation. Invest Ophthalmol Visual Sci. (2025) 66:6. doi: 10.1167/iovs.66.9.6

50

Chen N Wu J Wang J Piri N Chen F Xiao T et al . Short chain fatty acids inhibit endotoxin-induced uveitis and inflammatory responses of retinal astrocytes. Exp eye Res. (2021) 206:108520. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2021.108520

51

Hu J Wang C Huang X Yi S Pan S Zhang Y et al . Gut microbiota-mediated secondary bile acids regulate dendritic cells to attenuate autoimmune uveitis through TGR5 signaling. Cell Rep. (2021) 36:109726. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109726

52

Fukuda S Toh H Taylor TD Ohno H Hattori M . Acetate-producing bifidobacteria protect the host from enteropathogenic infection via carbohydrate transporters. Gut Microbes. (2012) 3:449–54. doi: 10.4161/gmic.21214

53

Li B Du P Du Y Zhao D Cai Y Yang Q et al . Luteolin alleviates inflammation and modulates gut microbiota in ulcerative colitis rats. Life Sci. (2021) 269:119008. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.119008

54

Zhao S Yan Q Xu W Zhang J . Gut microbiome in diabetic retinopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Microb Pathog. (2024) 189:106590. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2024.106590

55

Chen Y Xie C Lei Y Ye D Wang L Xiong F et al . Theabrownin from Qingzhuan tea prevents high-fat diet-induced MASLD via regulating intestinal microbiota. BioMed Pharmacother. (2024) 174:116582. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2024.116582

56

Mohebali N Weigel M Hain T Sutel M Bull J Kreikemeyer B et al . Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Bacteroides faecis and Roseburia intestinalis attenuate clinical symptoms of experimental colitis by regulating Treg/Th17 cell balance and intestinal barrier integrity. BioMed Pharmacother. (2023) 167:115568. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115568

57

Gao Y Xu P Sun D Jiang Y Lin XL Han T et al . Faecalibacterium prausnitzii abrogates intestinal toxicity and promotes tumor immunity to increase the efficacy of dual CTLA4 and PD-1 checkpoint blockade. Cancer Res. (2023) 83:3710–25. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-23-0605

58

Yang HT Jiang ZH Yang Y Wu TT Zheng YY Ma YT et al . Faecalibacterium prausnitzii as a potential Antiatherosclerotic microbe. Cell Commun Signal. (2024) 22:54. doi: 10.1186/s12964-023-01464-y

59

Tillmann A Ceklic L Dysli C Munk MR . Gender differences in retinal diseases: A review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. (2024) 52:317–33. doi: 10.1111/ceo.14364

60

Mokhtarpour K Yadegar A Mohammadi F Aghayan SN Seyedi SA Rabizadeh S et al . Impact of gender on chronic complications in participants with type 2 diabetes: evidence from a cross-sectional study. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. (2024) 7:e488. doi: 10.1002/edm2.488

61

Hanumunthadu D Van Dijk EHC Gangakhedkar S Goud A Cheung CMG Cherfan D et al . Gender variation in central serous chorioretinopathy. Eye (Lond). (2018) 32:1703–9. doi: 10.1038/s41433-018-0163-7

Summary

Keywords

inflammation, wound healing, Faecalibacterium , Bifidobacterium , neuroretina

Citation

Cui X, Qi J, Yi C, Liu J, Yuan X-L, Deng W and Xu H (2025) The microbiome exists in the neuroretina and choroid in normal conditions and responds rapidly to retinal injury. Front. Ophthalmol. 5:1719090. doi: 10.3389/fopht.2025.1719090

Received

05 October 2025

Revised

17 November 2025

Accepted

21 November 2025

Published

09 December 2025

Volume

5 - 2025

Edited by

Jiyang Cai, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, United States

Reviewed by

Davide Borroni, Riga Stradiņš University, Latvia

Sneha Singh, Wayne State University, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Cui, Qi, Yi, Liu, Yuan, Deng and Xu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Heping Xu, xuheping@aierchina.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.