Abstract

Aging is a natural aspect of mammalian life. Although cellular mortality is inevitable, various diseases can hasten the aging process, resulting in abnormal or premature senescence. As cells age, they experience distinctive morphological and biochemical shifts, compromising their functions. Research has illuminated that cellular senescence coincides with significant alterations in the microRNA (miRNA) expression profile. Notably, a subset of aging-associated miRNAs, originally encoded by nuclear DNA, relocate to mitochondria, manifesting a mitochondria-specific presence. Additionally, mitochondria themselves house miRNAs encoded by mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). These mitochondria-residing miRNAs, collectively referred to as mitochondrial miRNAs (mitomiRs), have been shown to influence mtDNA transcription and protein synthesis, thereby impacting mitochondrial functionality and cellular behavior. Recent studies suggest that mitomiRs serve as critical sensors for cellular senescence, exerting control over mitochondrial homeostasis and influencing metabolic reprogramming, redox equilibrium, apoptosis, mitophagy, and calcium homeostasis-all processes intimately connected to senescence. This review synthesizes current findings on mitomiRs, their mitochondrial targets, and functions, while also exploring their involvement in cellular aging. Our goal is to shed light on the potential molecular mechanisms by which mitomiRs contribute to the aging process.

Introduction

Tissue and organ aging significantly contributes to a myriad of diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders, diabetes, and cancer (de Magalhães, 2013). Cellular senescence underpins this aging process, hence unlocking the mysteries of cellular senescence may hold the key to thwarting degenerative diseases.

Telomere attrition is acknowledged as an intrinsic trigger of cellular senescence, where the inevitable shortening of telomeres due to each round of cell division precipitates chromosomal instability and consequent cell cycle arrest (Hewitt et al., 2012; Williams et al., 2017; Liu, 2022). Hyperglycemic conditions have been implicated in hastening senescence in proximal tubular cells by instigating telomere reduction and activating the p53-p21-Rb signaling axis (Verzola et al., 2008; Cao et al., 2018). Similarly, oxidative stress, inducing persistent DNA damage and reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation, serves as another catalyst for cellular senescence (Kornienko et al., 2019). Hyperoxia exposure, for example, has been shown to induce DNA damage and activate senescence pathways in rat nucleus pulposus cells (Feng et al., 2017). Metabolic aberrations, such as insulin resistance and impaired glucose transport, are also associated with senescence. Age-related declines in glucose uptake and transporter expression in neuronal cells underscore this link (Jiang et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2022). Moreover, epigenetic modifications, encompassing DNA and histone alterations and noncoding RNA (ncRNA) profile changes, are central to aging and age-related pathologies (Hou et al., 2014; Fan et al., 2020; Killaars et al., 2020). Inhibition of DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), for instance, has been found to induce senescence in multipotent stem cells and elevate aging markers (So et al., 2011).

Notably, ncRNAs, particularly microRNAs (miRNAs), are emerging as significant regulators of cellular senescence (Kim et al., 2021; Lee and Bae, 2022). These small, single-stranded ncRNAs orchestrate gene expression post-transcriptionally (Tétreault and De Guire, 2013; Duarte et al., 2015). mitomiRs, whether encoded by nuclear or mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), are distinguished by their mitochondrial regulation, influencing metabolism and redox reactions (Guerra-Assunção and Enright, 2012; Bandiera et al., 2013; Bianchessi et al., 2015; Fan et al., 2019). Research into the mitomiR-senescence relationship is at the vanguard of cell fate determination studies. MitomiRs profoundly impact cellular senescence (Giuliani et al., 2017; Giuliani et al., 2018). Akin to their nuclear and cytoplasmic counterparts, they regulate protein expression by targeting the 3′ untranslated regions (3′-UTR) of mitochondrial mRNA (Das et al., 2012). Certain mitomiRs have been shown to exert either prooxidant or antioxidant effects in cells, regulate 16S rRNA processing, and affect bioenergetic status, with implications for tumorigenesis and progression (Bai et al., 2011; Aschrafi et al., 2012; Das et al., 2012; Sripada et al., 2017). This review aggregates and discusses findings from the PubMed database (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), probing the mechanisms by which mitomiRs mediate cellular senescence through their regulatory roles in mitochondrial function.

Cellular senescence and tissue aging

Cellular senescence is a cornerstone of tissue aging, implicated in the deterioration of vital tissue structures crucial for normal function (Campisi, 2013). Furthermore, conditions of premature aging are marked by an increase in senescent cells, inflammatory cells, and trans-differentiated cells (Chen et al., 2015; Baker et al., 2016). Understanding the internal factors that influence cellular senescence and the consequent degeneration of tissues and organs is of paramount importance. Senescent cells enter an irreversible state of growth cessation. They typically exhibit a change in size, adopting a smoother and larger morphology compared to proliferating cells, and form senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (Narita et al., 2003). Despite their arrested growth, these cells remain metabolically active and are capable of secreting a wide array of bioactive substances such as growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and proteases. This phenomenon is referred to as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) (Shay and Roninson, 2004; Acosta et al., 2013; Calcinotto et al., 2019). Another hallmark of cellular senescence is the reduced expression of proteins that are critical to the electron transport chain (ETC), a change whose role as either a cause or a consequence of aging is currently debated (Gerasymchuk et al., 2020).

Prevailing research suggests that mechanisms like telomere shortening, activation of tumor suppressor pathways, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction are key initiators of cellular senescence (Williams et al., 2017). Senescence is heralded by the attrition of telomere sequences and damage to the T-loop, triggering the DNA damage response (DDR) to double-strand breaks (Gavia-García et al., 2021). A wealth of studies support the notion that both telomere impairment and the subsequent activation of DDR signaling pathways can hasten cellular aging (White et al., 2015; Koh et al., 2020; Assis et al., 2022). In light of recent findings, the relationship between mitochondrial function and cellular senescence is garnering significant attention (Harman, 1956; Gao et al., 2022). Mitochondria are not only the cell’s energy generators but also act as critical centers for both anabolic and catabolic metabolic processes. For cells to maintain their normal functions, a stable and continuous mitochondrial response is essential, demanding precisely orchestrated biogenesis and the meticulous expression of RNAs and proteins sourced from both nuclear and mitochondrial genomes. Errors in the transport, assembly, or targeting of these mitochondrial components can lead to detrimental effects on cellular homeostasis (Wasilewski et al., 2017).

Function of mitochondria

Mitochondria, the powerhouse organelles of the cell, are encapsulated by two distinct membranes (Duarte et al., 2014). The matrix within each mitochondrion is a hub brimming with ions, enzymes, metabolites, and crucial nucleic acids, containing its own DNA (approximately 16 kb) and RNA molecules (Choudhury and Singh, 2017). These organelles are instrumental in orchestrating a multitude of cellular functions, including cell death, autophagy, metabolic pathways, and the aging process (Weber and Reichert, 2010; Pan et al., 2011). Among their various roles, the regulation of energy metabolism is the most extensively researched. The process of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) is central to the mitochondria’s role as an energy converter, involving the synthesis of adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-the cell’s energy currency-through a sequential transfer of electrons via large protein complexes anchored in the inner mitochondrial membrane. During this intricate process, oxygen is consumed, setting up an electrochemical gradient that ultimately powers ATP synthesis. This electron transfer is facilitated by a cascade of redox-active complexes, known as complexes I through IV, which culminate in the reduction of oxygen to water (van der Bliek et al., 2017). An additional, critical function of mitochondrial respiration is the generation of ROS, which, while playing vital signaling roles at physiological levels, can become harmful in excess (Thannickal and Fanburg, 2000; Schumacker et al., 2014). These ROS can act as signaling molecules, inducing the expression and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Notably, this interplay between inflammatory mediators and ROS can reciprocally influence mitochondrial architecture and function, potentially establishing a detrimental feedback loop that contributes to disease pathogenesis and accelerates the aging process (Thannickal and Fanburg, 2000; Wiegman et al., 2015; Prakash et al., 2017).

Biogenesis of miRNA

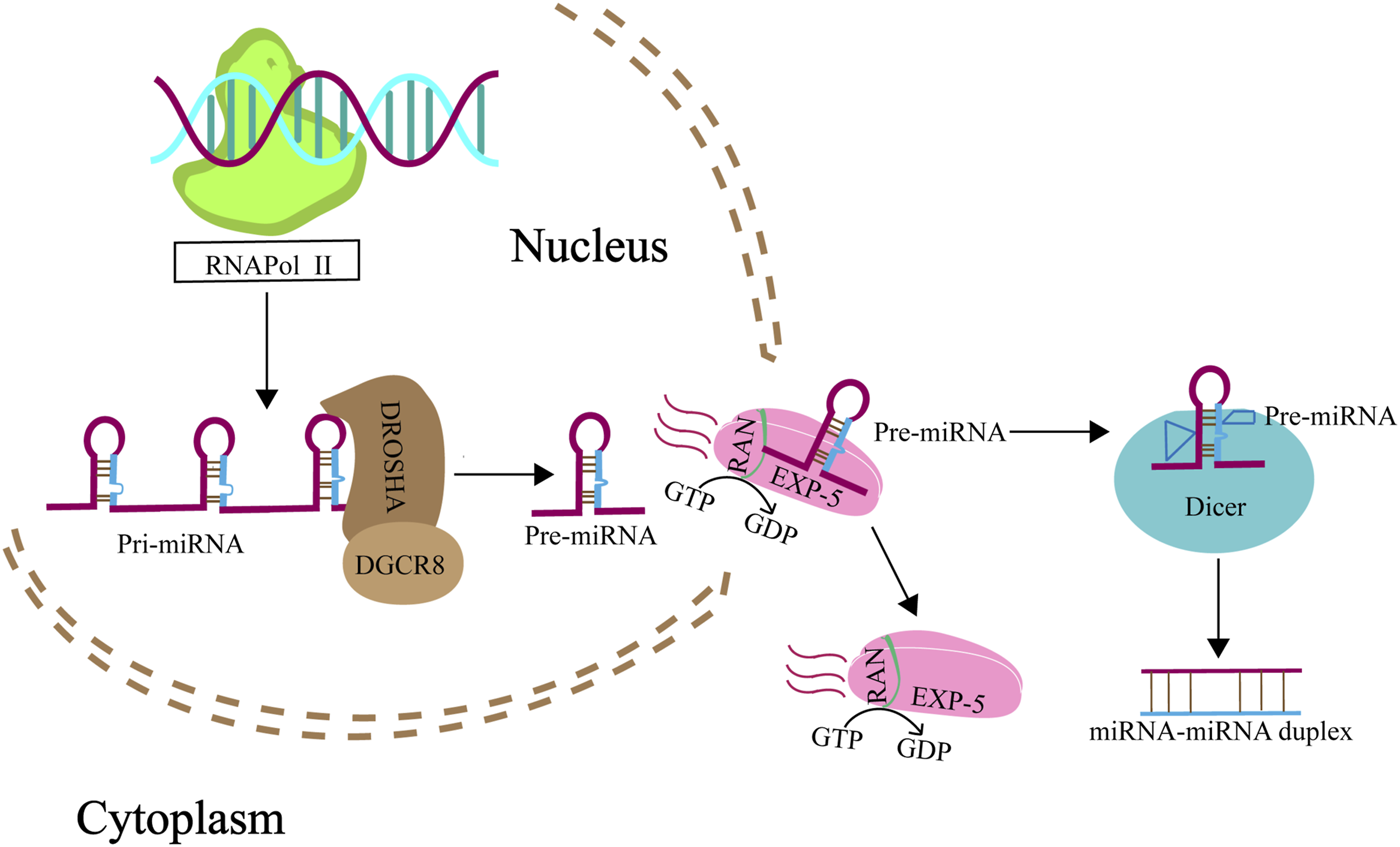

miRNAs are single-stranded, noncoding RNAs ranging from 19 to 24 nucleotides in length, acting as pivotal regulators of gene expression at the post-transcriptional level. They modulate gene expression by binding to complementary sequences within the 3′ untranslated regions (3′UTR) of target mRNAs, leading to mRNA degradation or inhibition of translation (Bartel, 2004). The biosynthesis of miRNAs is a complex process involving several enzymatic steps within both the nucleus and the cytoplasm (Figure 1) (Ha and Kim, 2014; Lin and Gregory, 2015). Typically, miRNA (non-mitomiR) biogeesis begins in the nucleus with the transcription of a primary-miRNA (pri-miRNA) from the DNA. This pri-miRNA is then processed by the Microprocessor complex, which consists of ribonuclease III enzyme (RNaseIII) and the DiGeorge syndrome chromosomal region 8 (DROSHA/DGCR8) enzyme, resulting in a precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA). This pre-miRNA is subsequently transported to the cytoplasm by the nuclear export factor exportin 5 in complex with the GTP-binding nuclear protein RAN-GTP. Once in the cytoplasm, the pre-miRNA is further cleaved by another RNase III enzyme, Dicer, to produce a double-stranded, mature miRNA (Srinivasan and Das, 2015).

FIGURE 1

Biogenesis of miRNA. Genes that give rise to miRNAs are transcribed by RNA polymerase II from the noncoding RNA regions of the genome, yielding pri-miRNAs. These pri-miRNAs are then intricately processed into pre-miRNAs through the concerted action of the nuclear RNaseIII Drosha, and its partnering RNA-binding protein, DGCR8. Subsequently, pre-miRNAs are shuttled from the nucleus to the cytoplasm by exportin 5 in association with RanGTP (A GTP-binding nuclear protein), passing through the nuclear pore complexes. Once in the cytoplasm, these pre-miRNAs encounter Dicer, another RNase III enzyme, which meticulously cleaves them into mature miRNA duplexes.

Transportation of miRNA into mitochondria

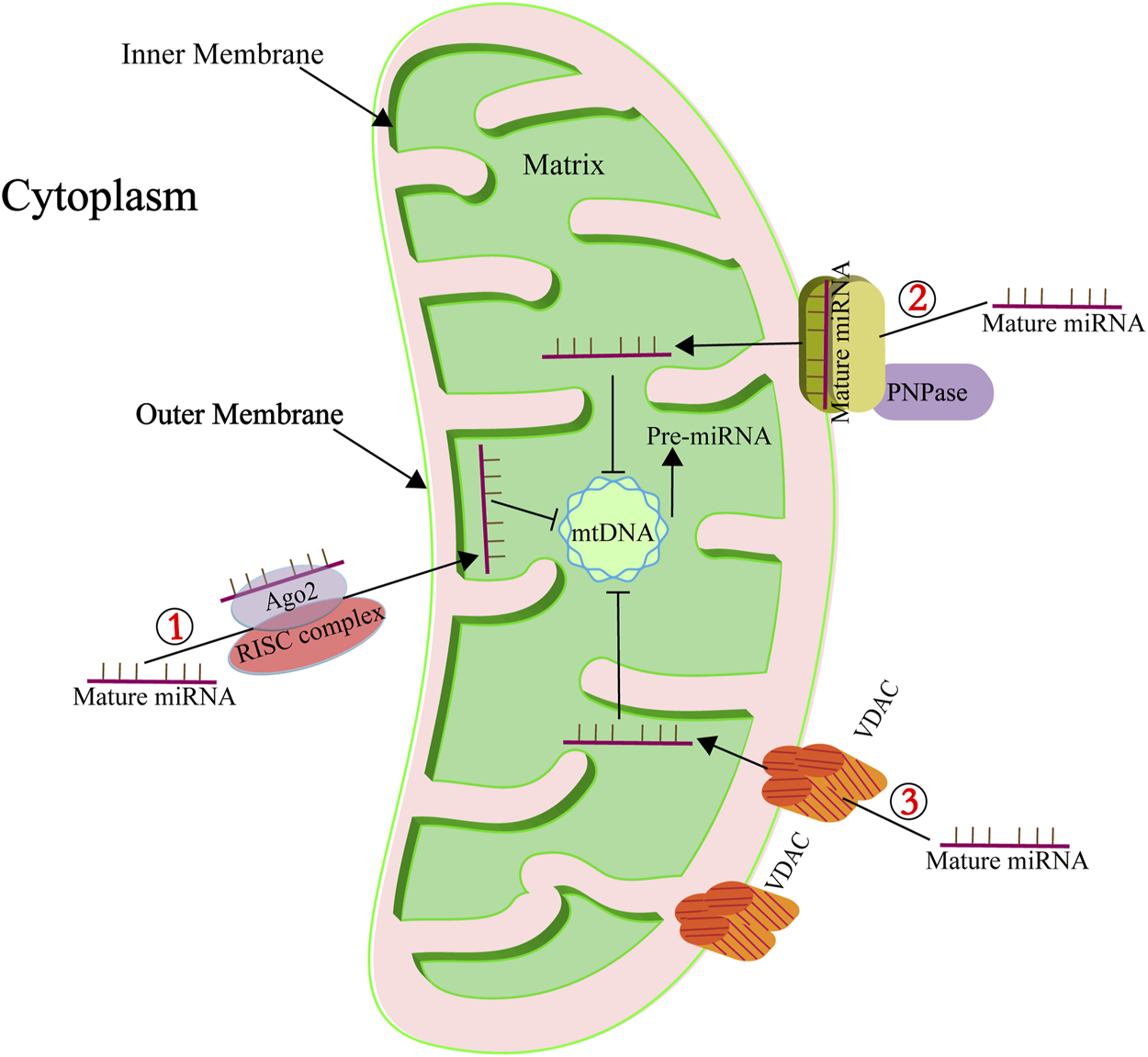

miRNAs have been detected within mitochondria (Lung et al., 2006; Chan et al., 2009; Kren et al., 2009; Bian et al., 2010; Favaro et al., 2010; Barrey et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2011; Shinde and Bhadra, 2015; Fan et al., 2019), and a particular subset, termed mitomiRs, are known to finely regulate mitochondrial functions (Li et al., 2012). These mitomiRs, predominantly encoded by the nuclear genome, are imported into mitochondria to modulate the expression of mRNAs originating from the mitochondrial genome. Table 1 provides a comprehensive list of these nuclear-derived mitomiRs and their mitochondrial roles. The precise mechanisms facilitating miRNA import into mitochondria remain elusive, but several proteins have been implicated in this complex transport process, as depicted in Figure 2. One of the key proteins is Argonaute2 (Ago2), which is ubiquitously present in mitochondria across various cell types. Research indicates a pivotal role for miRNA-Ago2 interactions in the mitochondrial translocation of mitomiRs (Fasanaro et al., 2008; Latronico and Condorelli, 2012; Meloni et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2015). For instance, Zhang et al. (2014) demonstrated that miR-1, which is upregulated during myogenesis, can effectively penetrate mitochondria by forming a complex with Ago2, thereby enhancing the translation of mitochondrial-encoded transcripts. Gohel et al. (2021) investigated the role of mitochondrial miRNAs in the pathogenesis of Fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS). In their study, miR-320a was found to associate with Ago2 in HEK293 cells exhibiting expanded CGG repeats, with a notable enrichment of this complex within the mitochondrial matrix. The miRNA-Ago2 complex associates with the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and can be shuttled into mitochondria via the coordinated action of the sorting and assembly machinery (SAM50), translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane 20 (TOM20), and translocase of the inner mitochondrial membrane (TIM) (Jusic et al., 2020). Another significant player is polynucleotide phosphorylase (PNPase), located at the inner mitochondrial membrane and projecting into the intermembrane space. PNPase has been identified as a crucial component in miRNA mitochondrial import. Wang et al. found that disrupting the PNPase gene (pnpt1) perturbs mitochondrial morphology and function in murine hepatic cells, partly by impeding RNA imports that govern the transcription and translation of ETC proteins (Wang et al., 2010). Shepherd et al. (2017) further elucidated that PNPase overexpression in HL-1 cardiomyocytes correlates with increased mitochondrial miRNA-378 levels, underscoring its role in miRNA transport. The voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) constitutes another potential conduit for miRNA import. As a highly conserved and predominant protein in the mitochondrial outer membrane, VDAC is hypothesized to facilitate the translocation of small noncoding RNAs into mitochondria. While Salinas et al. (2006) have shown that plant mitochondrial VDAC can bind to tRNA and mediate its import in vitro, its involvement in miRNA transport remains to be thoroughly investigated, indicating an exciting direction for future research (Colombini, 1980; Das et al., 2008; Bandiera et al., 2013; Macgregor-Das and Das, 2018a).

TABLE 1

| mitomiRs | Target genes | Cell/tissue | Modulation of mitomiR | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-1 | mt-COX1, mt-ND1 | C2C12 cells | ↑ | Enhance protein synthesis and ATP production | Zhang et al. (2014) |

| miR-21-5p | mt-CYTB, mt-ND1 | Spontaneous hypertensive rats, human muscular cells | ↑ or ↓ | Enhance Cytb translation in mitochondria | Barrey et al. (2011),Li et al. (2016) |

| miR-146a-5p | mt-ND1, mt-ND2, mt-ND4, mt-ND5, mt-ND6, mt-ATP8 | 206ρ cells | ↑ | — | Dasgupta et al. (2015),Giuliani et al. (2017) |

| miR-151a-5p | mt-CYTB | Severe asthenozoospermia | ↑ | Regulate ATP production through targeting Cytb | Zhou et al. (2015) |

| miR-181-c | mt-COX1, mt-COX2 | Rat cardiomyocytes | ↑ | Increase ROS generation, causing ETC, complex IV remodeling | Das et al. (2012),Das et al. (2014) |

| miR-378 | mt-ATP6 | HL-1 cells | ↑ | Decrease the functionality of ATP synthase | Jagannathan et al. (2015) |

| miR-762 | mt-ND2 | Mouse cardiomyocytes | ↓ | Improve OXPHOS efficiency (ADP/oxygen) | Yan et al. (2019) |

| miR-2392 | mt-ND4, mt-CYTB, mt-COX1 | TSCC cells, CAL-27 cells | ↓ | Downregulate OXPHOS and upregulate glycolysis | Fan et al. (2019) |

| miR-5787 | mt-COX3 | TSCC cells | ↓ | Attenuate OXPHOS and enhance glycolysis | Chen et al. (2019) |

| miR-92a | mt-CYTB | db/db mice heart | ↓ | — | Li et al. (2019a) |

| let-7b-5p, miR-34b-5p, let-7c-5p, miR-324-3p, miR-324-5p, miR-454-3p | mt-COX1, mt-COX2, mt-ATP6, mt-ATP8, mt-ND5, mt-ND6 | Human primary myoblast | ↓ | — | Barrey et al. (2011) |

| miR-15a, miR-196a, miR-296-3p | mt-ND2, mt-ND4, mt-ND4L, mt-ND5, mt- ATP6 | RAS-STCs | ↑ | Impair mitochondrial structure and function in swine STCs | Farahani et al. (2020) |

Nuclear-encoded mitomiRs and their functional roles in mitochondria.

↑, increase; ↓, decrease. ATP, adenosine-triphosphate; ADP, adenosine -diphosphate; ROS, reactive oxygen species; OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation; ETC, electron transport chain; RAS, renal artery stenosis; STCs, scattered tubular-like cells; TSCC, tongue squamous cell carcinoma; COX, cytochrome c oxidase subunit. CYTB, cytochrome B. ND, NADH, dehydrogenase.

The italicized text represents gene names.

FIGURE 2

Key mediators of miRNA mitochondrial import. ① Highlights the role of Ago2 in the subcellular distribution and transport of mitomiRs. Ago2, known for its RNase activity, functions as a crucial component of the RISC. ② Denotes the involvement of PNPase in the transportation of mitomiRs. PNPase is adept at recognizing specific structural features of housekeeping ncRNAs, facilitating their correct folding, passage through the mitochondrial membrane, and eventual reacquisition of their native conformation within the mitochondrial matrix. ③ Points to the role of the pore-forming protein VDAC in ncRNA transport. To date, VDAC’s role in RNA import is supported by a singular study indicating its involvement in the translocation of tRNA into mitochondria (Salinas et al., 2006).

mitomiRs that are transcribed from the mitochondrial genome

Emerging research has unveiled a complex landscape of noncoding RNA within mitochondria, including the discovery of novel mitomiRs that target the UTRs of mitochondrial genes (Lung et al., 2006; Villegas et al., 2007; Burzio et al., 2009; Mercer et al., 2011; Rackham et al., 2011; Smalheiser et al., 2011). Reports suggest that miR-1974, miR-1977, and miR-1978 may be transcribed directly from mtDNA (Bandiera et al., 2011; Barrey et al., 2011; Sripada et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2017). Supporting this notion, the sequences of certain pre-miRNAs and mature miRNAs-such as pre-miR-let7 and pre-miR-302a, which have been identified in human muscle mitochondria-show alignment with the mitochondrial genome, hinting at the possibility of intramitochondrial mitomiR biosynthesis (Barrey et al., 2011; Murri and El Azzouzi, 2018; Kussainova et al., 2022). However, the verification of these mitomiRs as products of mitochondrial gene transcription remains elusive. The lack of canonical miRNA processing enzymes-Drosha, DGCR8, and Dicer-within mitochondria presents a hurdle in confirming the mitochondrial origin of these miRNAs (Macgregor-Das and Das, 2018b). Table 2 compiles a list of mitomiRs that are postulated to be transcribed from the mitochondrial genome. The existence and functions of these miRNAs are primarily predicted using bioinformatics tools like TargetScan, MiRanda, and miRBase, with most awaiting experimental confirmation of their roles.

TABLE 2

| mitomiR | miRNA hosting genes | Location on mtDNA | Cells | Validation status | Functional confirmation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa-miR-1974 | mt-ND6/mt-TRNE, mt-ND5, mt-CYTB, mt-ND4, mt-ATP6 mt-ND1, mt-TRNS2/mt-TRNL | 14,675–14,697 | Hela cells | Validated | Unknown | Bandiera et al. (2011),Sripada et al. (2012) |

| hsa-miR-1977 | mt-ND4, mt-TRNN, mt-TRNP, mt-ND2, mt-RNR2, mt-ND5, mt-TRNL2 | 5,693–5,714 | Hela cells | Predicted | Unknown | Bandiera et al. (2011),Sripada et al. (2012) |

| hsa-miR-1978 | mt-ND1, mt-COX2, mt-COX1 | 654–674 | Hela cells | Predicted | Unknown | Bandiera et al. (2011),Sripada et al. (2012) |

| hsa-miR-4485 | mt-16S rRNA | 2,562–2,582 | HEK293, Hela and MCF7 | Validated | Unclear | Sripada et al. (2012),Sripada et al. (2017),Farfan et al. (2021) |

| hsa-miR-4461 | mt-ND4L | 10,690–10,712 | HEK293, Hela | Predicted | Unknown | Sripada et al. (2012) |

| hsa-miR-4463 | mt-ND5 | 13,050–13,068 | HEK293, Hela | Predicted | Unknown | Sripada et al. (2012) |

| hsa-miR-4484 | mt-L-ORF | 5,749–5,766 | HEK293, Hela | Predicted | Unknown | Sripada et al. (2012) |

| hsa-miR-mit-1 | mt-COX1 | 6,715–6,735 | Human skeletal muscle myoblast cells | Predicted | Unknown | Shinde and Bhadra (2015) |

| hsa-miR-mit-2 | mt-ATP8 | 8,454–8,472 | Human skeletal muscle myoblast cells | Predicted | Unknown | Shinde and Bhadra (2015) |

| hsa-miR-mit-3 | mt-ATP6 | 9,186–9,207 | Human skeletal muscle myoblast cells | Predicted | Unknown | Shinde and Bhadra (2015) |

| hsa-miR-mit-4 | mt-ND4L | 10,832–10,851 | Human skeletal muscle myoblast cells | Predicted | Unknown | Shinde and Bhadra (2015) |

| hsa-miR-mit-5 | mt-ND2 | 5,094–5,115 | Human skeletal muscle myoblast cells | Predicted | Unknown | Shinde and Bhadra (2015) |

| hsa-miR-mit-6 | mt-16S rRNA | 2,406-2,426 | Human skeletal muscle myoblast cells | Predicted | Unknown | Shinde and Bhadra (2015) |

List of mitomiRs identified through bioinformatics prediction.

The italicized text represents gene names.

Mitochondrial-related miRNAs and aging

Mitochondrial dysfunction and cellular senescence

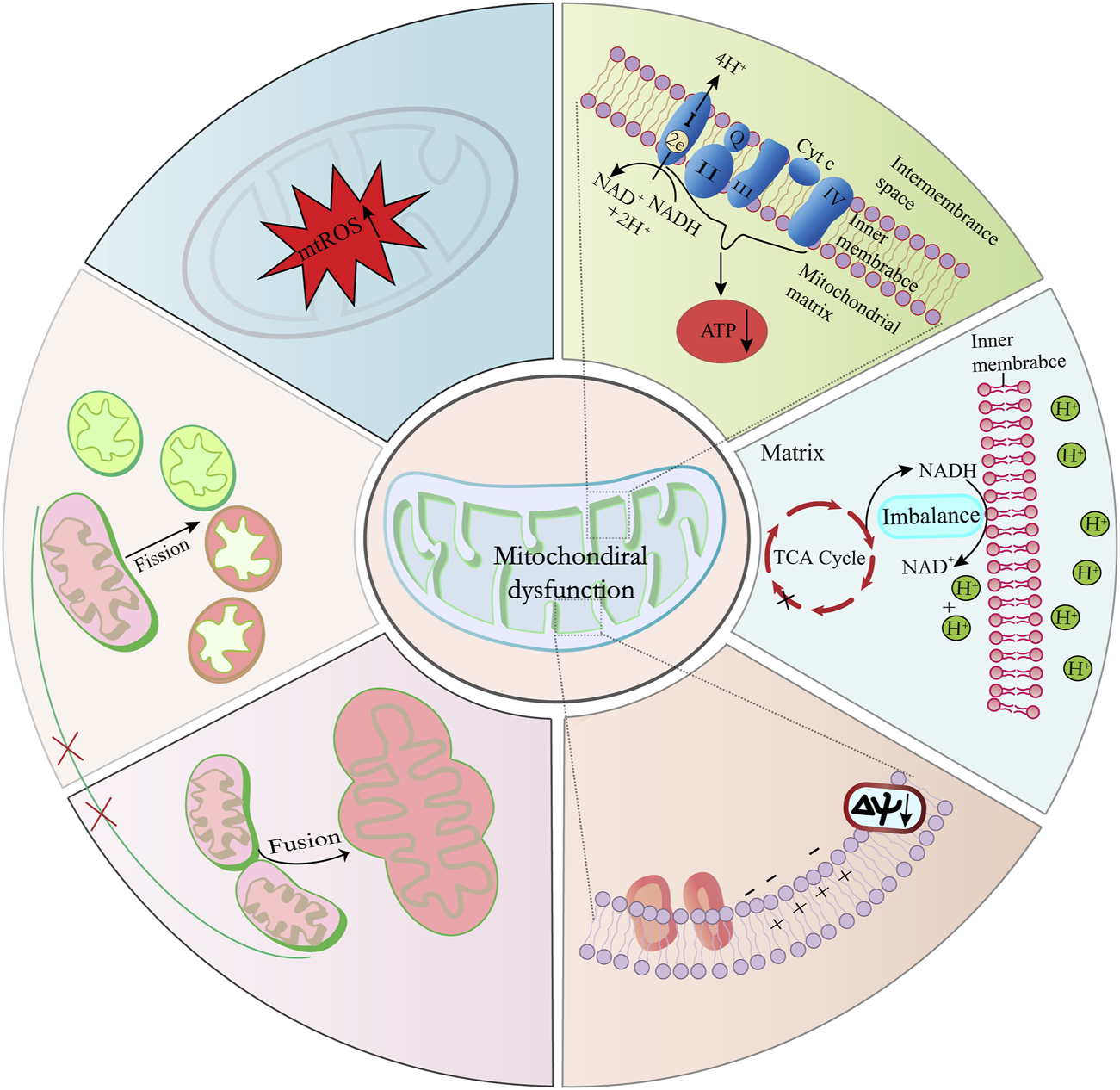

Mitochondrial dysfunction is increasingly recognized as a catalyst for accelerated aging and a contributor to age-related diseases (Sastre et al., 2000; Trifunovic et al., 2004). This dysfunction manifests through a spectrum of features, including: 1) diminished activity of ETC complexes; 2) disrupted NAD+/NADH balance; 3) an upset in the delicate equilibrium between mitochondrial fission and fusion processes; 4) elevated mitochondrial-reactive oxygen species (mtROS) production; and 5) compromised mitochondrial membrane potential alongside changes in mitochondrial permeability (refer to Figure 3). These dysfunctions coalesce to impair mitochondrial ATP production, a deficit that becomes particularly evident in the mitochondria of aged skeletal muscle, cardiac, and adipose tissues (Peterson et al., 2012; Boengler et al., 2017). The resulting disrupted energy metabolism, particularly the altered NAD+/NADH ratio, has a profound impact, not only on mitochondrial efficiency but also on cellular health, as it has been implicated in triggering cellular senescence (Stein and Imai, 2014; Wiley et al., 2016; Bakalova et al., 2022; Miwa et al., 2022).

FIGURE 3

Key factors contributing to mitochondrial dysfunction and cellular senescence. Imbalances in the mitochondrial NAD+/NADH ratio, elevated ROS levels, and diminished ETC, complex activities are primary contributors to mitochondrial dysfunction. Furthermore, disturbances in the equilibrium of mitochondrial division and fusion processes result in structural and functional alterations of mitochondria.

Maintaining a functional mitochondrial network through balanced fission and fusion is critical for mitochondrial integrity and function, thereby preventing damage accumulation and coordinating with autophagy for quality control (Ham and Raju, 2017). The importance of these processes is highlighted by findings such as those of Li X. et al. (2019), who observed that fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) deficiency can induce mitochondrial fusion and senescence in human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs). Conversely, Rana et al. (2017) reported that enhancing dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1)-dependent mitochondrial fission could extend the healthy lifespan in Drosophila Moreover, Yamamoto-Imoto et al. (2022) elucidated the interplay between cellular senescence and autophagy in renal aging, demonstrating that the transcription factor Mondo A might safeguard against senescence by promoting autophagy and preserving mitochondrial homeostasis.

Mitochondrial dysfunction is implicated in various metabolic disorders, and it’s particularly noted for its role in the aging process. One critical way mitochondria contribute to aging is through the heightened production of ROS. Normally, ROS generation is balanced with its neutralization within the body. However, when this balance is disturbed, and ROS production becomes excessive, it can overwhelm cellular antioxidant defenses. This imbalance leads to oxidative stress, which can precipitate premature aging and damage to tissues and organs (Chiang et al., 2020; Marí et al., 2020; Sreedhar et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2021). Intriguing research by Zhu et al. (2022) has revealed that interleukin-13 (IL-13) treatment may prompt cellular aging in submandibular gland-C6 cells. They propose a mechanism where IL-13 elevates levels of phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (p-STAT6) and mtROS. Concurrently, it diminishes the mitochondrial membrane potential and the production of ATP, alongside reducing both the expression and activity of superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2), an essential mitochondrial antioxidant enzyme (Zhu et al., 2022). Moreover, Springo et al. (2015) have shown that mtROS production is naturally increased in the smooth muscle cells of aged mice under hypertensive conditions. Therefore, targeted repair or enhancement of the cellular antioxidant system is an effective approach to reducing mitochondrial oxidative damage and delaying cellular aging. Park et al. (2013) have observed that supplementing the diet of elderly dogs with astaxanthin leads to increased ATP production, enhanced mitochondrial mass, and heightened activity of cytochrome c oxidoreductase, along with a reduction in mtROS production in leukocytes. These effects collectively may enhance mitochondrial functionality and mitigate oxidative damage to cellular DNA and proteins (Park et al., 2013). Glutathione (GSH) is crucial in shielding cells from damage induced by oxidative stress. Dysfunctional glutathione mechanisms are associated with the onset of numerous diseases as part of the aging process. An elevation in ROS levels, a reduction in GSH reserves, disruption of intracellular oxidoreductases, or diminished thioredoxin activity can all result in an imbalance between cellular ROS and GSH, subsequently leading to cellular aging (Liu et al., 2022). Ryan et al. (2010) have reported that resveratrol elevates GSH levels and boosts the activity of manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) and catalase. MnSOD, which is situated within the mitochondrial matrix, plays a pivotal role in safeguarding mitochondria against oxidative damage. Furthermore, resveratrol reduces the production of oxidants and mitigates oxidative damage in the gastrocnemius muscles of both young adult and aged mice engaged in exercise (Ryan et al., 2010).

Mitochondrial-localized miRNAs and their impact on mitochondrial dysfunction

The presence of miRNAs within the mitochondria endows them with the ability to modulate mitochondrial functions, thereby enriching our comprehension of miRNA characteristics and their influence on cellular destiny. Research into mitomiR-mediated mitochondrial regulation is prevalent, particularly in age-associated diseases, including cancers (Giuliani et al., 2017; John et al., 2020; Singh and Storey, 2021; Erturk et al., 2022; Kuthethur et al., 2022; Rivera et al., 2023). Liao et al. (2022) elucidated that mitomiR-1285 induces mitochondrial dysfunction and mitophagy in jejunal epithelial cells exposed to copper by promoting mtROS accumulation and reducing mitochondrial membrane potential. They also established that mitomiR-1285 targets isocitrate dehydrogenase [NADP (+)] 2 (IDH2), exacerbating copper-induced mitochondrial damage by repressing IDH2 via its 3′UTR (Liao et al., 2022). Kuthethur and colleagues uncovered 13 mitomiRs encoded by the mitochondrial genome, noting variations in expression across different breast cancer cell lines. Among these, mitomiR-5-5p was markedly upregulated in all examined cell lines, with mt-COX1 and mt-COX2 identified as its targets (Kuthethur et al., 2022). In tongue squamous cell carcinoma, overexpression of mitomiR-2392 was shown to selectively inhibit mtDNA transcription, significantly reducing the expression of ND4, COX1, and CYTB, which in turn suppresses OXPHOS (Fan et al., 2019). Shu et al. (2018) noted a decrease in miR-107 levels in mice with AD-like symptoms. Meanwhile, other studies by John et al. (2020) and Rech et al. (2019) have demonstrated that decreased miR-107 levels can lead to mitochondrial dysregulation, characterized by reductions in mitochondrial membrane potential and ETC activity (Shu et al., 2018; Rech et al., 2019; John et al., 2020). Ahn et al. (2021) discovered miR-494-3p in the mitochondria of retinal pigmented epithelial cells, where it plays a role in regulating mitochondrial function. Depletion of miR-494-3p led to a decline in ATP production and mitochondrial membrane potential, with mitochondrially encoded cytochrome c oxidase subunit 3 (mt-COX3) mRNA proposed as a likely target of miR-494-3p (Rehmsmeier et al., 2004; Ahn et al., 2021). Further investigations indicated that miR-15a, miR-196a, and miR-296-3p, residing in the mitochondria of scattered tubular-like cells, partake in the post-transcriptional governance of genes integral to mitochondrial function. Predictive analyses suggest these miRNAs target mitochondrial DNA to downregulate mt-ND2, mt-ND4, mt-ND4L, mt-ND5, and mt-ATP6, impairing mitochondrial integrity and activity (Farahani et al., 2020). Collectively, these studies suggest that mitomiRs predominantly influence mitochondrial function by affecting various aspects of metabolic pathways, such as the TCA cycle and the ETC. Mechanistically, mitomiRs may suppress protein synthesis by targeting mRNAs within mitochondria via their 3′UTRs, akin to their action in the cytoplasm. To date, there is no evidence to suggest that mitomiRs operate distinctively from other miRNAs.

Role of mitochondrial-related miRNAs in aging

Extensive research has illuminated the association between variations in mitomiRs and cellular aging. These variations in mitomiRs can lead to the accumulation of mtROS, activation of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway, inflammation, and alterations in mitochondrial dynamics-all pivotal in driving cellular senescence.

Mitochondrial complex I dysfunctions resulting in mtROS production are recognized as a key aging hallmark (Murphy, 2009; Ugalde et al., 2010). For instance, Lang et al. (2016) discovered that miR-15b levels diminish during senescence in human dermal fibroblasts, which is induced by ultraviolet or gamma irradiation. They found that miR-15b inhibition upregulated SIRT4 expression, heightening mtROS generation, lowering mitochondrial membrane potential, and altering the expression of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes and the SASP components (Lang et al., 2016). Das et al. (2012) highlighted how miR-181c, encoded by nuclear DNA, migrates into mitochondria, suppressing mt-COX1 and triggering mitochondrial dysfunction in rat ventricular myocytes. This led to restructured respiratory complex IV, increased mtROS, and induced myocardial dysfunction (Das et al., 2012; Das et al., 2017). Moreover, delivering miR-181c into rat hearts impeded exercise capacity and provoked heart failure symptoms (Das et al., 2014).

Oxidative stress, a major aging contributor, damages mitochondria, generating excessive mtROS, triggering cellular damage, and prompting apoptotic pathways. Sripada et al. (2017) showcased miR-4485’s involvement in regulating mitochondrial functions, demonstrating its direct interaction with mitochondrial 16S rRNA. This interaction impacted pre-rRNA processing and protein synthesis, which in turn modulated mitochondrial complex I activity, ATP, ROS levels, and induced apoptosis in cancer cells (Sripada et al., 2017). The expression of mitomiRs like miR-181a, −34a, and −146a, has been found to increase and localize within mitochondria in senescent endothelial cells, regulating apoptosis sensitivity by modulating Bcl-2 and activating caspases (Giuliani et al., 2018).

Senescent cells contribute to the acceleration of inflammaging by secreting proinflammatory factors, which plays a critical role in fostering the onset of prevalent diseases associated with aging. Giuliani et al. (2017) dicussed the potential influence of mitomiRs on senescent cells’ energetic, oxidative, and inflammatory status, with specific attention to mitomiRs like let-7b, miR-1, and miR-146a-5p. Among these, miR-146a is particularly noteworthy for its association with inflammation-mediated aging, although not all studies have confirmed its translocation to mitochondria (Giuliani et al., 2017). Research by Wang et al. (2015) has shed light on the behavior of miR-146a in the context of a rat traumatic brain injury model, where a significant compartmental shift of miR-146a from mitochondria to the cytoplasm was observed alongside other mitochondria-enriched miRNAs. This redistribution is intricately linked to trauma-induced alterations in mitochondrial bioenergetics and the regulation of inflammatory markers. Their further studies illustrated that the targeted delivery of miR-146a via nanoparticles markedly reduces the production of inflammatory mediators both in vitro and in vivo (Wang et al., 2015; Wang WX. et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2021). Through bioinformatics analysis, Rippo et al. (2014) discussed the role of inflammation-related mitomiRs in human “inflame-aging” and predicted that miR-181a, miR-34a, and miR-146a might regulate mitochondrial function and inflammation during cellular aging by modulating Bcl-2 family members (Rippo et al., 2014). Li et al. (2010) found that the upregulation of miR-146a could curb the production of inflammatory mediators in senescent cells, thus limiting their harmful impact on surrounding tissues (Li et al., 2010). Similarly, Olivieri et al. (2013) and Ong et al. (2018) demonstrated that an increase in miR-146a is linked with inflammatory senescence in various cell types, including human fibroblasts, trabecular meshwork cells, and endothelial cells (Olivieri et al., 2013; Ong et al., 2018).

Mitochondrial dynamics are crucial for maintaining cellular integrity and play a pivotal role in regulating senescence and related cellular processes. The critical balance of mitochondrial fusion and fission is primarily controlled by essential proteins like mitofusin-1 (MFN1), MFN2, optic atrophy 1 (OPA1), and mitochondrial fission factor (MFF) (Ni et al., 2015). Numerous studies indicate that mitochondria-related miRNAs modulate these proteins, thereby influencing mitochondrial function. Mu et al. provided evidence that miR-20b negatively influences the expression of MFN1 and MFN2, the principal mediators of mitochondrial fusion (Mu et al., 2021). Bucha et al. demonstrated in a model of Huntington’s disease that miR-214 directly targets MFN2, with its upregulation leading to decreased MFN2 levels, thus disturbing the mitochondrial fusion-fission balance, resulting in impaired fusion and increased fragmentation (Bucha et al., 2015). In their work, Lang et al. (2017) showed that enhancing SIRT4 expression via miR-15b inhibition leads to elevated levels of L-OPA1, thereby fostering mitochondrial fusion (Lang et al., 2017). Conversely, Lee et al. (2017) identified that miR-200a-3p binds MFF mRNA, reducing MFF expression, which in turn promotes mitochondrial elongation and influences overall mitochondrial dynamics. Goljanek-Whysall et al. (2020) highlighted the role of miR-181a as a regulator of mitochondrial dynamics, particularly during the aging of skeletal muscle. They demonstrated that in aged mice, miR-181a administration increased the expression of mitochondrial genes such as COX1 and ND-1, while a decline in miR-181a with age correlated with an accumulation of autophagy-related proteins and the presence of dysfunctional mitochondria (Goljanek-Whysall et al., 2020).

Conclusion and perspectives

Previous research on mitochondria has primarily focused on their role in energy provision and metabolic regulation. However, the latest findings suggest that mitochondria also serve as critical sites for cellular signal transduction and information exchange. The cross-talk and information network between the nucleus, cytoplasm, and mitochondria significantly influence vital cellular processes such as survival, apoptosis, differentiation, and aging.

Recent studies have shown that under certain conditions, such as disease or stress, noncoding RNAs, especially miRNAs, are abnormally enriched in mitochondria (Wang X. et al., 2017; Carden et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2021; Yan et al., 2021). This suggests that these mitochondria-enriched miRNAs play a crucial role in regulating mitochondrial behavior, which could significantly affect cellular functions, including drug resistance, inflammation, and aging.

miRNAs are small regulatory molecules that are abundant and diverse within cells. They are relatively easy to transcribe, synthesize, transport, and degrade. These characteristics make miRNAs well-suited for shuttling between the nucleus and mitochondria, transferring signals, and flexibly performing regulatory functions within mitochondria. The study of miRNA functions within the nucleus and cytoplasm is vast. However, research into mitomiRs has emerged as a new hot topic in recent years. Elucidating the molecular mechanisms of mitomiR regulation of mitochondrial behavior can expand our understanding of miRNA functions and more deeply clarify the connections between miRNA functions and diseases.

Nevertheless, research on mitomiRs is still in its infancy, with few reports published. Integrating current literature on mitochondrial-related miRNAs and mitomiRs, we identify several unclear aspects: 1) the molecular mechanisms and driving forces behind the translocation of mitomiRs into mitochondria; 2) the varieties and amounts of mitomiRs transcribed by mtDNA; 3) how mitomiR profiles change during biological events and their impact on mitochondrial behaviors; and 5) the significance and influence of mitochondrial-cytoplasmic-nuclear communication. These areas are gaps that future researchers will need to fill.

The study of mitomiRs is undoubtedly more challenging than that of nuclear and cytoplasmic miRNAs. This difficulty is due, in part, to the lack of efficient techniques to edit genetic material in mitochondria, which poses obstacles to the study of mitochondrial genetics and epigenetics. Although next-generation sequencing technology has become widely used, there is still a lack of experience in the bioinformatic analysis of mitomiRs. Furthermore, during our research group’s investigations into mitomiRs, we have found that isolating relatively pure mitomiRs is not an easy task. This could be another barrier to understanding the biological functions of mitomiRs.

In summary, in this article, we review the currently discovered mitochondrial-related miRNAs and their impact on mitochondria and cellular function, particularly regarding cellular aging. We hope this review will attract more researchers to focus on the investigation of mitochondrial-related miRNAs and develop their potential applications in disease diagnosis and treatment in the future.

Statements

Author contributions

LL: Writing–original draft, Data curation, Investigation. XA: Data curation, Writing–review and editing. YX: Data curation, Writing–review and editing. XS: Writing–review and editing, Supervision. SL: Writing–review and editing, Supervision. YW: Data curation, Writing–review and editing. WS: Data curation, Supervision, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing–review and editing. DY: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Project administration, Supervision, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported in part by Jilin International Collaboration Grant (20220402066GH to DY).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Glossary

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| mtDNA | Mitochondrial DNA |

| mitomiR | Mitochondrial miRNA |

| ncRNA | non-coding RNA |

| 3′-UTR | 3′ untranslated regions |

| SASP | Senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| DDR | DNA damage response |

| D-loop | Displacement loop |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| DROSHA/DGCR8 | DiGeorge syndrome chromosomal region 8 |

| RANGTP | A GTP-binding nuclear protein |

| RNaseIII | Ribonuclease III enzyme |

| Ago2 | Argonaute2 |

| FXTAS | Fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome |

| RISC | RNA-induced silencing complex |

| SAM50 | Sorting and assembly complex |

| TOM20 | Translocase of the outer mitochondrial membrane 20 |

| TIM | Translocase of the inner mitochondrial membrane |

| PNPase | Polynucleotide phosphorylase |

| VDAC | Voltage-dependent anion channel |

| ADP | Adenosine-diphosphate |

| CYTB | Cytochrome B |

| ND | NADH dehydrogenase |

| RAS | Renal artery stenosis |

| COX | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit |

| ETC | Electron transport chain |

| OXPHOS | Oxidative phosphorylation |

| FGF21 | Fibroblast growth factor 21 |

| hMSCs | Human Mesenchymal stem cell |

| OPA1 | Optic atrophy 1 |

| Drp1 | Dynamin-related protein |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| IL-13 | Interleukin-13 |

| p-STAT6 | Phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of Transcription 6 |

| IDH2 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase [NADP (+)] 2 |

| mt-COX3 | Mitochondrially encoded cytochrome c oxidase subunit 3 |

| STCs | Scattered tubular-like cells |

| mtROS | Mitochondrial-reactive oxygen species |

| SOD2 | Superoxide dismutase 2 |

| TSCC | Tongue squamous cell carcinoma |

| MnSOD | Manganese superoxide dismutase |

| MFN1 | Mitofusin-1 |

| MFF | Mitochondrial fission factor |

References

1

AcostaJ. C.BanitoA.WuestefeldT.GeorgilisA.JanichP.MortonJ. P.et al (2013). A complex secretory program orchestrated by the inflammasome controls paracrine senescence. Nat. Cell Biol.15 (8), 978–990. 10.1038/ncb2784

2

AhnJ. Y.DattaS.BandeiraE.CanoM.MallickE.RaiU.et al (2021). Release of extracellular vesicle miR-494-3p by ARPE-19 cells with impaired mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj.1865 (4), 129598. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2020.129598

3

AschrafiA.KarA. N.Natera-NaranjoO.MacGibenyM. A.GioioA. E.KaplanB. B. (2012). MicroRNA-338 regulates the axonal expression of multiple nuclear-encoded mitochondrial mRNAs encoding subunits of the oxidative phosphorylation machinery. Cell Mol. Life Sci.69 (23), 4017–4027. 10.1007/s00018-012-1064-8

4

AssisV.de Sousa NetoI. V.RibeiroF. M.de Cassia MarquetiR.FrancoO. L.da Silva AguiarS.et al (2022). The emerging role of the aging process and exercise training on the crosstalk between gut microbiota and telomere length. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health19 (13), 7810. 10.3390/ijerph19137810

5

BaiX. Y.MaY.DingR.FuB.ShiS.ChenX. M. (2011). miR-335 and miR-34a Promote renal senescence by suppressing mitochondrial antioxidative enzymes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol.22 (7), 1252–1261. 10.1681/ASN.2010040367

6

BakalovaR.AokiI.ZhelevZ.HigashiT. (2022). Cellular redox imbalance on the crossroad between mitochondrial dysfunction, senescence, and proliferation. Redox Biol.53, 102337. 10.1016/j.redox.2022.102337

7

BakerD. J.ChildsB. G.DurikM.WijersM. E.SiebenC. J.ZhongJ.et al (2016). Naturally occurring p16(Ink4a)-positive cells shorten healthy lifespan. Nature530 (7589), 184–189. 10.1038/nature16932

8

BandieraS.MatégotR.GirardM.DemongeotJ.Henrion-CaudeA. (2013). MitomiRs delineating the intracellular localization of microRNAs at mitochondria. Free Radic. Biol. Med.64, 12–19. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.06.013

9

BandieraS.RubergS.GirardM.CagnardN.HaneinS.ChretienD.et al (2011). Nuclear outsourcing of RNA interference components to human mitochondria. PLoS One6 (6), e20746. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020746

10

BarreyE.Saint-AuretG.BonnamyB.DamasD.BoyerO.GidrolX. (2011). Pre-microRNA and mature microRNA in human mitochondria. PLoS One6 (5), e20220. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020220

11

BartelD. P. (2004). MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell116 (2), 281–297. 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5

12

BianZ.LiL. M.TangR.HouD. X.ChenX.ZhangC. Y.et al (2010). Identification of mouse liver mitochondria-associated miRNAs and their potential biological functions. Cell Res.20 (9), 1076–1078. 10.1038/cr.2010.119

13

BianchessiV.BadiI.BertolottiM.NigroP.D'AlessandraY.CapogrossiM. C.et al (2015). The mitochondrial lncRNA ASncmtRNA-2 is induced in aging and replicative senescence in Endothelial Cells. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol.81, 62–70. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.01.012

14

BoenglerK.KosiolM.MayrM.SchulzR.RohrbachS. (2017). Mitochondria and ageing: role in heart, skeletal muscle and adipose tissue. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle8 (3), 349–369. 10.1002/jcsm.12178

15

BuchaS.MukhopadhyayD.BhattacharyyaN. P. (2015). Regulation of mitochondrial morphology and cell cycle by microRNA-214 targeting Mitofusin2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.465 (4), 797–802. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.08.090

16

BurzioV. A.VillotaC.VillegasJ.LandererE.BoccardoE.VillaL. L.et al (2009). Expression of a family of noncoding mitochondrial RNAs distinguishes normal from cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.106 (23), 9430–9434. 10.1073/pnas.0903086106

17

CalcinottoA.KohliJ.ZagatoE.PellegriniL.DemariaM.AlimontiA. (2019). Cellular senescence: aging, cancer, and injury. Physiol. Rev.99 (2), 1047–1078. 10.1152/physrev.00020.2018

18

CampisiJ. (2013). Aging, cellular senescence, and cancer. Annu. Rev. Physiol.75, 685–705. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183653

19

CaoD. W.JiangC. M.WanC.ZhangM.ZhangQ. Y.ZhaoM.et al (2018). Upregulation of MiR-126 delays the senescence of human glomerular mesangial cells induced by high glucose via telomere-p53-p21-Rb signaling pathway. Curr. Med. Sci.38 (5), 758–764. 10.1007/s11596-018-1942-x

20

CardenT.SinghB.MoogaV.BajpaiP.SinghK. K. (2017). Epigenetic modification of miR-663 controls mitochondria-to-nucleus retrograde signaling and tumor progression. J. Biol. Chem.292 (50), 20694–20706. 10.1074/jbc.M117.797001

21

ChanS. Y.ZhangY. Y.HemannC.MahoneyC. E.ZweierJ. L.LoscalzoJ. (2009). MicroRNA-210 controls mitochondrial metabolism during hypoxia by repressing the iron-sulfur cluster assembly proteins ISCU1/2. Cell Metab.10 (4), 273–284. 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.08.015

22

ChenR.ZhangK.ChenH.ZhaoX.WangJ.LiL.et al (2015). Telomerase deficiency causes alveolar stem cell senescence-associated low-grade inflammation in lungs. J. Biol. Chem.290 (52), 30813–30829. 10.1074/jbc.M115.681619

23

ChenW.WangP.LuY.JinT.LeiX.LiuM.et al (2019). Decreased expression of mitochondrial miR-5787 contributes to chemoresistance by reprogramming glucose metabolism and inhibiting MT-CO3 translation. Theranostics9 (20), 5739–5754. 10.7150/thno.37556

24

ChiangJ. L.ShuklaP.PagidasK.AhmedN. S.KarriS.GunnD. D.et al (2020). Mitochondria in ovarian aging and reproductive longevity. Ageing Res. Rev.63, 101168. 10.1016/j.arr.2020.101168

25

ChoudhuryA. R.SinghK. K. (2017). Mitochondrial determinants of cancer health disparities. Semin. Cancer Biol.47, 125–146. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.05.001

26

ColombiniM. (1980). Structure and mode of action of a voltage dependent anion-selective channel (VDAC) located in the outer mitochondrial membrane. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci.341, 552–563. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1980.tb47198.x

27

DasS.BedjaD.CampbellN.DunkerlyB.ChennaV.MaitraA.et al (2014). miR-181c regulates the mitochondrial genome, bioenergetics, and propensity for heart failure in vivo. PLoS One9 (5), e96820. 10.1371/journal.pone.0096820

28

DasS.FerlitoM.KentO. A.Fox-TalbotK.WangR.LiuD.et al (2012). Nuclear miRNA regulates the mitochondrial genome in the heart. Circ. Res.110 (12), 1596–1603. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.267732

29

DasS.KohrM.Dunkerly-EyringB.LeeD. I.BedjaD.KentO. A.et al (2017). Divergent effects of miR-181 family members on myocardial function through protective cytosolic and detrimental mitochondrial microRNA targets. J. Am. Heart Assoc.6 (3), e004694. 10.1161/JAHA.116.004694

30

DasS.WongR.RajapakseN.MurphyE.SteenbergenC. (2008). Glycogen synthase kinase 3 inhibition slows mitochondrial adenine nucleotide transport and regulates voltage-dependent anion channel phosphorylation. Circ. Res.103 (9), 983–991. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.178970

31

DasguptaN.PengY.TanZ.CiraoloG.WangD.LiR. (2015). miRNAs in mtDNA-less cell mitochondria. Cell Death Discov.1, 15004. 10.1038/cddiscovery.2015.4

32

de MagalhãesJ. P. (2013). How ageing processes influence cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer13 (5), 357–365. 10.1038/nrc3497

33

DuarteF. V.PalmeiraC. M.RoloA. P. (2014). The role of microRNAs in mitochondria: small players acting wide. Genes (Basel)5 (4), 865–886. 10.3390/genes5040865

34

DuarteF. V.PalmeiraC. M.RoloA. P. (2015). The emerging role of MitomiRs in the pathophysiology of human disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol.888, 123–154. 10.1007/978-3-319-22671-2_8

35

ErturkE.Enes OnurO.AkgunO.TunaG.YildizY.AriF. (2022). Mitochondrial miRNAs (MitomiRs): their potential roles in breast and other cancers. Mitochondrion66, 74–81. 10.1016/j.mito.2022.08.002

36

FanS.TianT.ChenW.LvX.LeiX.ZhangH.et al (2019). Mitochondrial miRNA determines chemoresistance by reprogramming metabolism and regulating mitochondrial transcription. Cancer Res.79 (6), 1069–1084. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-2505

37

FanT.MengX.SunC.YangX.ChenG.LiW.et al (2020). Genome-wide DNA methylation profile analysis in thoracic ossification of the ligamentum flavum. J. Cell Mol. Med.24 (15), 8753–8762. 10.1111/jcmm.15509

38

FarahaniR. A.ZhuX. Y.TangH.JordanK. L.LermanL. O.EirinA. (2020). Renal ischemia alters expression of mitochondria-related genes and impairs mitochondrial structure and function in swine scattered tubular-like cells. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol.319 (1), F19–f28. 10.1152/ajprenal.00120.2020

39

FarfanN.SanhuezaN.BrionesM.BurzioL. O.BurzioV. A. (2021). Antisense noncoding mitochondrial RNA-2 gives rise to miR-4485-3p by Dicer processing in vitro. Biol. Res.54 (1), 33. 10.1186/s40659-021-00356-0

40

FasanaroP.D'AlessandraY.Di StefanoV.MelchionnaR.RomaniS.PompilioG.et al (2008). MicroRNA-210 modulates endothelial cell response to hypoxia and inhibits the receptor tyrosine kinase ligand Ephrin-A3. J. Biol. Chem.283 (23), 15878–15883. 10.1074/jbc.M800731200

41

FavaroE.RamachandranA.McCormickR.GeeH.BlancherC.CrosbyM.et al (2010). MicroRNA-210 regulates mitochondrial free radical response to hypoxia and krebs cycle in cancer cells by targeting iron sulfur cluster protein ISCU. PLoS One5 (4), e10345. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010345

42

FengC.ZhangY.YangM.LanM.LiuH.HuangB.et al (2017). Oxygen-sensing Nox4 generates genotoxic ROS to induce premature senescence of nucleus pulposus cells through MAPK and NF-κB pathways. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev.2017, 7426458. 10.1155/2017/7426458

43

GaoX.YuX.ZhangC.WangY.SunY.SunH.et al (2022). Telomeres and mitochondrial metabolism: implications for cellular senescence and age-related diseases. Stem Cell Rev. Rep.18, 2315–2327. 10.1007/s12015-022-10370-8

44

Gavia-GarcíaG.Rosado-PérezJ.Arista-UgaldeT. L.Aguiñiga-SánchezI.Santiago-OsorioE.Mendoza-NúñezV. M. (2021). Telomere length and oxidative stress and its relation with metabolic syndrome components in the aging. Biol. (Basel).10 (4), 253. 10.3390/biology10040253

45

GerasymchukM.CherkasovaV.KovalchukO.KovalchukI. (2020). The role of microRNAs in organismal and skin aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21 (15), 5281. 10.3390/ijms21155281

46

GiulianiA.CirilliI.PrattichizzoF.MensàE.FulgenziG.SabbatinelliJ.et al (2018). The mitomiR/Bcl-2 axis affects mitochondrial function and autophagic vacuole formation in senescent endothelial cells. Aging (Albany NY)10 (10), 2855–2873. 10.18632/aging.101591

47

GiulianiA.PrattichizzoF.MicolucciL.CerielloA.ProcopioA. D.RippoM. R. (2017). Mitochondrial (dys) function in inflammaging: do MitomiRs influence the energetic, oxidative, and inflammatory status of senescent cells?Mediat. Inflamm.2017, 2309034. 10.1155/2017/2309034

48

GohelD.SripadaL.PrajapatiP.CurrimF.RoyM.SinghK.et al (2021). Expression of expanded FMR1-CGG repeats alters mitochondrial miRNAs and modulates mitochondrial functions and cell death in cellular model of FXTAS. Free Radic. Biol. Med.165, 100–110. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.01.038

49

Goljanek-WhysallK.Soriano-ArroquiaA.McCormickR.ChindaC.McDonaghB. (2020). miR-181a regulates p62/SQSTM1, parkin, and protein DJ-1 promoting mitochondrial dynamics in skeletal muscle aging. Aging Cell19 (4), e13140. 10.1111/acel.13140

50

Guerra-AssunçãoJ. A.EnrightA. J. (2012). Large-scale analysis of microRNA evolution. BMC Genomics13, 218. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-218

51

HaM.KimV. N. (2014). Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.15 (8), 509–524. 10.1038/nrm3838

52

HamP. B.3rdRajuR. (2017). Mitochondrial function in hypoxic ischemic injury and influence of aging. Prog. Neurobiol.157, 92–116. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2016.06.006

53

HarmanD. (1956). Aging: a theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J. Gerontol.11 (3), 298–300. 10.1093/geronj/11.3.298

54

HewittG.JurkD.MarquesF. D.Correia-MeloC.HardyT.GackowskaA.et al (2012). Telomeres are favoured targets of a persistent DNA damage response in ageing and stress-induced senescence. Nat. Commun.3, 708. 10.1038/ncomms1708

55

HouX. F.FanD. W.SunC. G.ChenZ. Q. (2014). Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2-induced ossification of the ligamentum flavum in rats and the associated global modification of histone H3. J. Neurosurg. Spine21 (3), 334–341. 10.3171/2014.4.SPINE13319

56

HuangL.MolletS.SouquereS.Le RoyF.Ernoult-LangeM.PierronG.et al (2011). Mitochondria associate with P-bodies and modulate microRNA-mediated RNA interference. J. Biol. Chem.286 (27), 24219–24230. 10.1074/jbc.M111.240259

57

JagannathanR.ThapaD.NicholsC. E.ShepherdD. L.StrickerJ. C.CrostonT. L.et al (2015). Translational regulation of the mitochondrial genome following redistribution of mitochondrial MicroRNA in the diabetic heart. Circ. Cardiovasc Genet.8 (6), 785–802. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.115.001067

58

JiangT.YinF.YaoJ.BrintonR. D.CadenasE. (2013). Lipoic acid restores age-associated impairment of brain energy metabolism through the modulation of Akt/JNK signaling and PGC1α transcriptional pathway. Aging Cell12 (6), 1021–1031. 10.1111/acel.12127

59

JohnA.KubosumiA.ReddyP. H. (2020). Mitochondrial MicroRNAs in aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Cells9 (6), 1345. 10.3390/cells9061345

60

JusicA.DevauxY.EU-CardioRNA COST Action CA17129 (2020). Mitochondrial noncoding RNA-regulatory network in cardiovascular disease. Basic Res. Cardiol.115 (3), 23. 10.1007/s00395-020-0783-5

61

KillaarsA. R.WalkerC. J.AnsethK. S. (2020). Nuclear mechanosensing controls MSC osteogenic potential through HDAC epigenetic remodeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.117 (35), 21258–21266. 10.1073/pnas.2006765117

62

KimK. M.NohJ. H.AbdelmohsenK.GorospeM. (2017). Mitochondrial noncoding RNA transport. BMB Rep.50 (4), 164–174. 10.5483/bmbrep.2017.50.4.013

63

KimY.JiH.ChoE.ParkN. H.HwangK.ParkW.et al (2021). nc886, a non-coding RNA, is a new biomarker and epigenetic mediator of cellular senescence in fibroblasts. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22 (24), 13673. 10.3390/ijms222413673

64

KohS. H.ChoiS. H.JeongJ. H.JangJ. W.ParkK. W.KimE. J.et al (2020). Telomere shortening reflecting physical aging is associated with cognitive decline and dementia conversion in mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease. Aging (Albany NY)12 (5), 4407–4423. 10.18632/aging.102893

65

KornienkoJ. S.SmirnovaI. S.PugovkinaN. A.IvanovaJ. S.ShilinaM. A.GrinchukT. M.et al (2019). High doses of synthetic antioxidants induce premature senescence in cultivated mesenchymal stem cells. Sci. Rep.9 (1), 1296. 10.1038/s41598-018-37972-y

66

KrenB. T.WongP. Y.SarverA.ZhangX.ZengY.SteerC. J. (2009). MicroRNAs identified in highly purified liver-derived mitochondria may play a role in apoptosis. RNA Biol.6 (1), 65–72. 10.4161/rna.6.1.7534

67

KussainovaA.BulgakovaO.AripovaA.KhalidZ.BersimbaevR.IzzottiA. (2022). The role of mitochondrial miRNAs in the development of radon-induced lung cancer. Biomedicines10 (2), 428. 10.3390/biomedicines10020428

68

KuthethurR.ShuklaV.MallyaS.AdigaD.KabekkoduS. P.RamachandraL.et al (2022). Expression analysis and function of mitochondrial genome-encoded microRNAs. J. Cell Sci.135 (8), jcs258937. 10.1242/jcs.258937

69

LangA.AnandR.Altinoluk-HambüchenS.EzzahoiniH.StefanskiA.IramA.et al (2017). SIRT4 interacts with OPA1 and regulates mitochondrial quality control and mitophagy. Aging (Albany NY)9 (10), 2163–2189. 10.18632/aging.101307

70

LangA.Grether-BeckS.SinghM.KuckF.JakobS.KefalasA.et al (2016). MicroRNA-15b regulates mitochondrial ROS production and the senescence-associated secretory phenotype through sirtuin 4/SIRT4. Aging (Albany NY)8 (3), 484–505. 10.18632/aging.100905

71

LatronicoM. V.CondorelliG. (2012). The might of microRNA in mitochondria. Circ. Res.110 (12), 1540–1542. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.271312

72

LeeH.TakH.ParkS. J.JoY. K.ChoD. H.LeeE. K. (2017). microRNA-200a-3p enhances mitochondrial elongation by targeting mitochondrial fission factor. BMB Rep.50 (4), 214–219. 10.5483/bmbrep.2017.50.4.006

73

LeeY.BaeY. S. (2022). Long non-coding RNA KCNQ1OT1 regulates protein kinase CK2 via miR-760 in senescence and calorie restriction. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23 (3), 1888. 10.3390/ijms23031888

74

LiG.LunaC.QiuJ.EpsteinD. L.GonzalezP. (2010). Modulation of inflammatory markers by miR-146a during replicative senescence in trabecular meshwork cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci.51 (6), 2976–2985. 10.1167/iovs.09-4874

75

LiH.DaiB.FanJ.ChenC.NieX.YinZ.et al (2019a). The different roles of miRNA-92a-2-5p and let-7b-5p in mitochondrial translation in db/db mice. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids17, 424–435. 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.06.013

76

LiH.ZhangX.WangF.ZhouL.YinZ.FanJ.et al (2016). MicroRNA-21 lowers blood pressure in spontaneous hypertensive rats by upregulating mitochondrial translation. Circulation134 (10), 734–751. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023926

77

LiP.JiaoJ.GaoG.PrabhakarB. S. (2012). Control of mitochondrial activity by miRNAs. J. Cell Biochem.113 (4), 1104–1110. 10.1002/jcb.24004

78

LiX.HongY.HeH.JiangG.YouW.LiangX.et al (2019b). FGF21 mediates mesenchymal stem cell senescence via regulation of mitochondrial dynamics. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev.2019, 4915149. 10.1155/2019/4915149

79

LiaoJ.LiQ.HuZ.YuW.ZhangK.MaF.et al (2022). Mitochondrial miR-1285 regulates copper-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and mitophagy by impairing IDH2 in pig jejunal epithelial cells. J. Hazard Mater422, 126899. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126899

80

LinS.GregoryR. I. (2015). MicroRNA biogenesis pathways in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer15 (6), 321–333. 10.1038/nrc3932

81

LiuR. M. (2022). Aging, cellular senescence, and alzheimer's disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23 (4), 1989. 10.3390/ijms23041989

82

LiuT.SunL.ZhangY.WangY.ZhengJ. (2022). Imbalanced GSH/ROS and sequential cell death. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol.36 (1), e22942. 10.1002/jbt.22942

83

LungB.ZemannA.MadejM. J.SchuelkeM.TechritzS.RufS.et al (2006). Identification of small non-coding RNAs from mitochondria and chloroplasts. Nucleic Acids Res.34 (14), 3842–3852. 10.1093/nar/gkl448

84

Macgregor-DasA. M.DasS. (2018a). A microRNA’s journey to the center of the mitochondria. Am. J. Physiology-Heart Circulatory Physiology315 (2), H206–H15. 10.1152/ajpheart.00714.2017

85

Macgregor-DasA. M.DasS. (2018b). A microRNA's journey to the center of the mitochondria. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol.315 (2), H206–h15. 10.1152/ajpheart.00714.2017

86

MaríM.de GregorioE.de DiosC.Roca-AgujetasV.CucarullB.TutusausA.et al (2020). Mitochondrial glutathione: recent insights and role in disease. Antioxidants (Basel)9 (10), 909. 10.3390/antiox9100909

87

MeloniM.MarchettiM.GarnerK.LittlejohnsB.Sala-NewbyG.XenophontosN.et al (2013). Local inhibition of microRNA-24 improves reparative angiogenesis and left ventricle remodeling and function in mice with myocardial infarction. Mol. Ther.21 (7), 1390–1402. 10.1038/mt.2013.89

88

MercerT. R.NephS.DingerM. E.CrawfordJ.SmithM. A.ShearwoodA. M.et al (2011). The human mitochondrial transcriptome. Cell146 (4), 645–658. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.051

89

MiwaS.KashyapS.ChiniE.von ZglinickiT. (2022). Mitochondrial dysfunction in cell senescence and aging. J. Clin. Invest.132 (13), e158447. 10.1172/JCI158447

90

MuG.DengY.LuZ.LiX.ChenY. (2021). miR-20b suppresses mitochondrial dysfunction-mediated apoptosis to alleviate hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury by directly targeting MFN1 and MFN2. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai).53 (2), 220–228. 10.1093/abbs/gmaa161

91

MurphyM. P. (2009). How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem. J.417 (1), 1–13. 10.1042/BJ20081386

92

MurriM.El AzzouziH. (2018). MicroRNAs as regulators of mitochondrial dysfunction and obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol.315 (2), H291–H302. 10.1152/ajpheart.00691.2017

93

NaritaM.NũnezS.HeardE.NaritaM.LinA. W.HearnS. A.et al (2003). Rb-mediated heterochromatin formation and silencing of E2F target genes during cellular senescence. Cell113 (6), 703–716. 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00401-x

94

NiH. M.WilliamsJ. A.DingW. X. (2015). Mitochondrial dynamics and mitochondrial quality control. Redox Biol.4, 6–13. 10.1016/j.redox.2014.11.006

95

OlivieriF.LazzariniR.RecchioniR.MarcheselliF.RippoM. R.Di NuzzoS.et al (2013). MiR-146a as marker of senescence-associated pro-inflammatory status in cells involved in vascular remodelling. Age (Dordr)35 (4), 1157–1172. 10.1007/s11357-012-9440-8

96

OngS. M.HadadiE.DangT. M.YeapW. H.TanC. T.NgT. P.et al (2018). The pro-inflammatory phenotype of the human non-classical monocyte subset is attributed to senescence. Cell Death Dis.9 (3), 266. 10.1038/s41419-018-0327-1

97

PanS.RyuS. Y.SheuS. S. (2011). Distinctive characteristics and functions of multiple mitochondrial Ca2+ influx mechanisms. Sci. China Life Sci.54 (8), 763–769. 10.1007/s11427-011-4203-9

98

ParkJ. S.MathisonB. D.HayekM. G.ZhangJ.ReinhartG. A.ChewB. P. (2013). Astaxanthin modulates age-associated mitochondrial dysfunction in healthy dogs. J. Anim. Sci.91 (1), 268–275. 10.2527/jas.2012-5341

99

PetersonC. M.JohannsenD. L.RavussinE. (2012). Skeletal muscle mitochondria and aging: a review. J. Aging Res.2012, 194821. 10.1155/2012/194821

100

PrakashY. S.PabelickC. M.SieckG. C. (2017). Mitochondrial dysfunction in airway disease. Chest152 (3), 618–626. 10.1016/j.chest.2017.03.020

101

RackhamO.ShearwoodA. M.MercerT. R.DaviesS. M.MattickJ. S.FilipovskaA. (2011). Long noncoding RNAs are generated from the mitochondrial genome and regulated by nuclear-encoded proteins. Rna17 (12), 2085–2093. 10.1261/rna.029405.111

102

RanaA.OliveiraM. P.KhamouiA. V.AparicioR.ReraM.RossiterH. B.et al (2017). Promoting Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission in midlife prolongs healthy lifespan of Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Commun.8 (1), 448. 10.1038/s41467-017-00525-4

103

RechM.KuhnA. R.LumensJ.CaraiP.van LeeuwenR.VerhesenW.et al (2019). AntagomiR-103 and -107 treatment affects cardiac function and metabolism. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids14, 424–437. 10.1016/j.omtn.2018.12.010

104

RehmsmeierM.SteffenP.HochsmannM.GiegerichR. (2004). Fast and effective prediction of microRNA/target duplexes. Rna10 (10), 1507–1517. 10.1261/rna.5248604

105

RippoM. R.OlivieriF.MonsurròV.PrattichizzoF.AlbertiniM. C.ProcopioA. D. (2014). MitomiRs in human inflamm-aging: a hypothesis involving miR-181a, miR-34a and miR-146a. Exp. Gerontol.56, 154–163. 10.1016/j.exger.2014.03.002

106

RiveraJ.GangwaniL.KumarS. (2023). Mitochondria localized microRNAs: an unexplored miRNA niche in alzheimer's disease and aging. Cells12 (5), 742. 10.3390/cells12050742

107

RyanM. J.JacksonJ. R.HaoY.WilliamsonC. L.DabkowskiE. R.HollanderJ. M.et al (2010). Suppression of oxidative stress by resveratrol after isometric contractions in gastrocnemius muscles of aged mice. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci.65 (8), 815–831. 10.1093/gerona/glq080

108

SalinasT.DuchêneA. M.DelageL.NilssonS.GlaserE.ZaepfelM.et al (2006). The voltage-dependent anion channel, a major component of the tRNA import machinery in plant mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.103 (48), 18362–18367. 10.1073/pnas.0606449103

109

SastreJ.PallardóF. V.García de la AsunciónJ.ViñaJ. (2000). Mitochondria, oxidative stress and aging. Free Radic. Res.32 (3), 189–198. 10.1080/10715760000300201

110

SchumackerP. T.GillespieM. N.NakahiraK.ChoiA. M.CrouserE. D.PiantadosiC. A.et al (2014). Mitochondria in lung biology and pathology: more than just a powerhouse. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol.306 (11), L962–L974. 10.1152/ajplung.00073.2014

111

ShayJ. W.RoninsonI. B. (2004). Hallmarks of senescence in carcinogenesis and cancer therapy. Oncogene23 (16), 2919–2933. 10.1038/sj.onc.1207518

112

ShepherdD. L.HathawayQ. A.PintiM. V.NicholsC. E.DurrA. J.SreekumarS.et al (2017). Exploring the mitochondrial microRNA import pathway through Polynucleotide Phosphorylase (PNPase). J. Mol. Cell Cardiol.110, 15–25. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2017.06.012

113

ShindeS.BhadraU. (2015). A complex genome-microRNA interplay in human mitochondria. Biomed. Res. Int.2015, 206382. 10.1155/2015/206382

114

ShuB.ZhangX.DuG.FuQ.HuangL. (2018). MicroRNA-107 prevents amyloid-β-induced neurotoxicity and memory impairment in mice. Int. J. Mol. Med.41 (3), 1665–1672. 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3339

115

SinghG.StoreyK. B. (2021). MicroRNA cues from nature: a roadmap to decipher and combat challenges in human health and disease?Cells10 (12), 3374. 10.3390/cells10123374

116

SmalheiserN. R.LugliG.ThimmapuramJ.CookE. H.LarsonJ. (2011). Mitochondrial small RNAs that are up-regulated in hippocampus during olfactory discrimination training in mice. Mitochondrion11 (6), 994–995. 10.1016/j.mito.2011.08.014

117

SoA. Y.JungJ. W.LeeS.KimH. S.KangK. S. (2011). DNA methyltransferase controls stem cell aging by regulating BMI1 and EZH2 through microRNAs. PLoS One6 (5), e19503. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019503

118

SpringoZ.TarantiniS.TothP.TucsekZ.KollerA.SonntagW. E.et al (2015). Aging exacerbates pressure-induced mitochondrial oxidative stress in mouse cerebral arteries. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci.70 (11), 1355–1359. 10.1093/gerona/glu244

119

SreedharA.Aguilera-AguirreL.SinghK. K. (2020). Mitochondria in skin health, aging, and disease. Cell Death Dis.11 (6), 444. 10.1038/s41419-020-2649-z

120

SrinivasanH.DasS. (2015). Mitochondrial miRNA (MitomiR): a new player in cardiovascular health. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol.93 (10), 855–861. 10.1139/cjpp-2014-0500

121

SripadaL.SinghK.LipatovaA. V.SinghA.PrajapatiP.TomarD.et al (2017). hsa-miR-4485 regulates mitochondrial functions and inhibits the tumorigenicity of breast cancer cells. J. Mol. Med. Berl.95 (6), 641–651. 10.1007/s00109-017-1517-5

122

SripadaL.TomarD.PrajapatiP.SinghR.SinghA. K.SinghR. (2012). Systematic analysis of small RNAs associated with human mitochondria by deep sequencing: detailed analysis of mitochondrial associated miRNA. PLoS One7 (9), e44873. 10.1371/journal.pone.0044873

123

SteinL. R.ImaiS. (2014). Specific ablation of Nampt in adult neural stem cells recapitulates their functional defects during aging. Embo J.33 (12), 1321–1340. 10.1002/embj.201386917

124

TétreaultN.De GuireV. (2013). miRNAs: their discovery, biogenesis and mechanism of action. Clin. Biochem.46 (10-11), 842–845. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2013.02.009

125

ThannickalV. J.FanburgB. L. (2000). Reactive oxygen species in cell signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol.279 (6), L1005–L1028. 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.6.L1005

126

TrifunovicA.WredenbergA.FalkenbergM.SpelbrinkJ. N.RovioA. T.BruderC. E.et al (2004). Premature ageing in mice expressing defective mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Nature429 (6990), 417–423. 10.1038/nature02517

127

UgaldeA. P.OrdóñezG. R.QuirósP. M.PuenteX. S.López-OtínC. (2010). Metalloproteases and the degradome. Methods Mol. Biol.622, 3–29. 10.1007/978-1-60327-299-5_1

128

van der BliekA. M.SedenskyM. M.MorganP. G. (2017). Cell biology of the mitochondrion. Genetics207 (3), 843–871. 10.1534/genetics.117.300262

129

VerzolaD.GandolfoM. T.GaetaniG.FerrarisA.MangeriniR.FerrarioF.et al (2008). Accelerated senescence in the kidneys of patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol.295 (5), F1563–F1573. 10.1152/ajprenal.90302.2008

130

VillegasJ.BurzioV.VillotaC.LandererE.MartinezR.SantanderM.et al (2007). Expression of a novel non-coding mitochondrial RNA in human proliferating cells. Nucleic Acids Res.35 (21), 7336–7347. 10.1093/nar/gkm863

131

WangG.ChenH. W.OktayY.ZhangJ.AllenE. L.SmithG. M.et al (2010). PNPASE regulates RNA import into mitochondria. Cell142 (3), 456–467. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.035

132

WangQ.DuanL.LiX.WangY.GuoW.GuanF.et al (2022). Glucose metabolism, neural cell senescence and alzheimer's disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23 (8), 4351. 10.3390/ijms23084351

133

WangW. X.PrajapatiP.VekariaH. J.SpryM.CloudA. L.SullivanP. G.et al (2021). Temporal changes in inflammatory mitochondria-enriched microRNAs following traumatic brain injury and effects of miR-146a nanoparticle delivery. Neural Regen. Res.16 (3), 514–522. 10.4103/1673-5374.293149

134

WangW. X.SullivanP. G.SpringerJ. E. (2017a). Mitochondria and microRNA crosstalk in traumatic brain injury. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry73, 104–108. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2016.02.011

135

WangW. X.VisavadiyaN. P.PandyaJ. D.NelsonP. T.SullivanP. G.SpringerJ. E. (2015). Mitochondria-associated microRNAs in rat hippocampus following traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol.265, 84–93. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.12.018

136

WangX.SongC.ZhouX.HanX.LiJ.WangZ.et al (2017b). Mitochondria associated MicroRNA expression profiling of heart failure. Biomed. Res. Int.2017, 4042509. 10.1155/2017/4042509

137

WasilewskiM.ChojnackaK.ChacinskaA. (2017). Protein trafficking at the crossroads to mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res.1864 (1), 125–137. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.10.019

138

WeberT. A.ReichertA. S. (2010). Impaired quality control of mitochondria: aging from a new perspective. Exp. Gerontol.45 (7-8), 503–511. 10.1016/j.exger.2010.03.018

139

WhiteR. R.MilhollandB.de BruinA.CurranS.LabergeR. M.van SteegH.et al (2015). Controlled induction of DNA double-strand breaks in the mouse liver induces features of tissue ageing. Nat. Commun.6, 6790. 10.1038/ncomms7790

140

WiegmanC. H.MichaeloudesC.HajiG.NarangP.ClarkeC. J.RussellK. E.et al (2015). Oxidative stress-induced mitochondrial dysfunction drives inflammation and airway smooth muscle remodeling in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol.136 (3), 769–780. 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.01.046

141

WileyC. D.VelardeM. C.LecotP.LiuS.SarnoskiE. A.FreundA.et al (2016). Mitochondrial dysfunction induces senescence with a distinct secretory phenotype. Cell Metab.23 (2), 303–314. 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.11.011

142

WilliamsJ.SmithF.KumarS.VijayanM.ReddyP. H. (2017). Are microRNAs true sensors of ageing and cellular senescence?Ageing Res. Rev.35, 350–363. 10.1016/j.arr.2016.11.008

143

Yamamoto-ImotoH.MinamiS.ShiodaT.YamashitaY.SakaiS.MaedaS.et al (2022). Age-associated decline of MondoA drives cellular senescence through impaired autophagy and mitochondrial homeostasis. Cell Rep.38 (9), 110444. 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110444

144

YanK.AnT.ZhaiM.HuangY.WangQ.WangY.et al (2019). Mitochondrial miR-762 regulates apoptosis and myocardial infarction by impairing ND2. Cell Death Dis.10 (7), 500. 10.1038/s41419-019-1734-7

145

YanL. R.WangA.LvZ.YuanY.XuQ. (2021). Mitochondria-related core genes and TF-miRNA-hub mrDEGs network in breast cancer. Biosci. Rep.41 (1). 10.1042/BSR20203481

146

ZhangX.ZuoX.YangB.LiZ.XueY.ZhouY.et al (2014). MicroRNA directly enhances mitochondrial translation during muscle differentiation. Cell158 (3), 607–619. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.047

147

ZhouR.WangR.QinY.JiJ.XuM.WuW.et al (2015). Mitochondria-related miR-151a-5p reduces cellular ATP production by targeting CYTB in asthenozoospermia. Sci. Rep.5, 17743. 10.1038/srep17743

148

ZhouX. Y.ZhangJ.LiY.ChenY. X.WuX. M.LiX.et al (2021). Advanced oxidation protein products induce G1/G0-phase arrest in ovarian granulosa cells via the ROS-JNK/p38 MAPK-p21 pathway in premature ovarian insufficiency. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev.2021, 6634718. 10.1155/2021/6634718

149

ZhuM.MinS.MaoX.ZhouY.ZhangY.LiW.et al (2022). Interleukin-13 promotes cellular senescence through inducing mitochondrial dysfunction in IgG4-related sialadenitis. Int. J. Oral Sci.14 (1), 29. 10.1038/s41368-022-00180-6

Summary

Keywords

cellular senescence, mitochondria, epigenetics, noncoding RNA, mitomiRs

Citation

Luo L, An X, Xiao Y, Sun X, Li S, Wang Y, Sun W and Yu D (2024) Mitochondrial-related microRNAs and their roles in cellular senescence. Front. Physiol. 14:1279548. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2023.1279548

Received

18 August 2023

Accepted

13 December 2023

Published

05 January 2024

Volume

14 - 2023

Edited by

Nazzareno Capitanio, University of Foggia, Italy

Reviewed by

Rui Song, Loma Linda University, United States

Germaine Escames, University of Granada, Spain

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Luo, An, Xiao, Sun, Li, Wang, Sun and Yu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Weixia Sun, sunwx@jlu.edu.cn; Dehai Yu, yudehai@jlu.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.