- Northeastern University, Shenyang, China

Background: Accurate localization and segmentation of polyp lesions in colonoscopic images are crucial for the early diagnosis of colorectal cancer and treatment planning. However, endoscopic imaging is often affected by noise interference. This includes issues like uneven illumination, mucosal reflections, and motion artifacts. To mitigate the impact of such interference on segmentation performance, it is essential to integrate multi-scale feature analysis effectively. Features at different scales capture distinct aspects of image information. Yet, existing methods typically rely on simple feature summation or concatenation. These methods lack the capability for adaptive fusion across scales.

Methods: To address these limitations, this paper proposes AFCNet—an Adaptive Fusion Composite Attention Convolutional Neural Network. AFCNet is designed to improve robustness against noise interference and enhance multi-scale feature fusion for polyp segmentation. The key innovations of AFCNet include: (1) integrating depthwise separable convolution with attention mechanisms in a multi-branch architecture. This allows for the simultaneous extraction of fine details and salient features. (2) Constructing a dynamic multi-scale feature pyramid with learnable weight allocation for adaptive cross-scale fusion.

Results: Extensive experiments on five public datasets (ClinicDB, Kvasir-SEG, etc.) demonstrate that AFCNet achieves state-of-the-art performance, with improvements of up to 3.73

Conclusion: AFCNet is a novel polyp segmentation network that leverages convolutional attention and adaptive multi-scale feature fusion, delivering exceptional generalization and adaptability.

1 Introduction

Colorectal cancer is a common malignant tumor with an increasing incidence rate, posing a serious threat to human health. Therefore, the prevention of colorectal cancer has become an important focus of medical research. Studies have shown that polyps are often precancerous lesions in colorectal cancer. Early detection and removal of colorectal polyps is one of the most effective methods for reducing the incidence of colorectal cancer and improving cure rates (Jia et al., 2019). Physicians rely on screening tools such as colonoscopy for the diagnosis of colon cancer. However, in clinical practice, small polyps may be missed by the naked eye, potentially delaying timely treatment (Zimmermann-Fraedrich et al., 2019). Automatic and precise polyp segmentation can assist doctors in precisely locating polyp regions within the colon (Guo et al., 2020), enhancing diagnostic accuracy and reducing the likelihood of oversight. Therefore, polyp segmentation plays a crucial role in the early diagnosis of colorectal cancer.

Due to the complex shapes and varying sizes of polyps, effectively fusing multi-scale features is crucial for significantly enhancing the model’s segmentation performance. Deep learning-based techniques have driven advancements in colon polyp segmentation. Convolutional neural network (CNN)-based approaches, such as U-Net (Ronneberger et al., 2015) and its variants, including UNet++ (Zhou et al., 2019) and Unet3+ (Huang et al., 2020), improve performance through nested skip connections. However, these methods are inadequately modeling long-range dependencies and rely on relatively simple integration strategies for fusing features from different scales. As a result, they may introduce noise from low-level information, and high-level features can blur the boundary details preserved in low-level features.

Transformer-based approaches (e.g., Polyp-pvt (Dong et al., 2021), MSRAformer (Wu et al., 2022), and SSFormer (Wang et al., 2022)) demonstrate superior feature extraction capabilities, but still face two challenges: (a) insufficient attention to the importance of features during the decoding process, and (b) suboptimal integration of information across different scales. Recently, researchers have proposed hybrid methods that combine CNNs and Transformers to leverage the strengths of both (Peng et al., 2024). However, existing approaches have not fully considered the potential multi-scale features within the same layer and the issue of semantic mismatch between features that are far apart in the hierarchy.

This paper proposes a U-shaped polyp segmentation network architecture based on convolutional attention and multi-scale feature adaptive fusion. Extensive experiments demonstrate that our method outperforms existing polyp segmentation approaches in both segmentation accuracy and generalizability across five colorectal polyp datasets. The paper makes two key contributions: (1) A new Multi-scale Depth-wise Convolutional Attention Module (MDCA): the MDCA module consists of a depth-separable convolutional and multi-branching network, which extracts multi-scale features within the layer and enhances the focus and utilization of important features. (2) A new Multi-scale Adaptive Feature Fusion Module (MAFF), which consists of a multi-scale cross-fusion network and an Adaptive Multi-Scale Feature Harmonization (AMFH) module. The multi-scale cross-fusion network enables smooth transmission of feature information across semantic hierarchies through a progressive feature fusion approach. Additionally, the adaptive multi-scale feature coordination module provides a flexible way to integrate and strengthen feature information at different levels.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 systematically reviews the related research work in the field of polyp segmentation and analyses the advantages and shortcomings of the existing methods. Section 3 comprehensively describes the network architecture design of AFCNet, and thoroughly analyses the implementation principles and technological breakthroughs of the three core modules, namely, MDCA, MAFF and UFR. Section 4 describes the experimental setup in detail, including dataset configuration, evaluation indexes and comparative experimental design, and analyses the results quantitatively and qualitatively. Finally, Section 5 gives the conclusions of this paper.

2 Related work

2.1 Polyp segmentation network

Traditional segmentation algorithms such as Otsu’s method (Vala and Baxi, 2013), Region Growing (Pohle and Toennies, 2001), Snake (Bresson et al., 2007) and other methods are sensitive to noise and image quality. Additionally, setting and adjusting their parameters is difficult, and they often provide insufficient segmentation accuracy and fail to capture fine details. Consequently, these methods yield low segmentation accuracy for polyps. In contrast, deep learning methods can automatically learn complex image features, handle noise more robustly, and eliminate the need for manual parameter tuning (Ahamed et al., 2024b).

Thus, deep learning methods provide more accurate and robust segmentation results in many application scenarios Ahamed et al. (2023a). With the development of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), especially with the introduction of U-Net (Ronneberger et al., 2015), many models inspired by this architecture have shown promising results in the field of medical image segmentation. UNet reduces the resolution of an image through a series of convolutional and pooling layers to capture the contextual information of the image. It then gradually restores the resolution using upsampling and convolution operations, effectively combining low- and high-resolution features to enable precise pixel-level segmentation. EU-Net Patel et al. (2021) enhances semantic information by introducing a global context module for extracting key features. ACSNet (Zhang et al., 2020) modifies the skip connections in U-Net into a local context extraction module and adds a global information extraction module. CENet (Gu et al., 2019) uses a ResNet pre-trained model as an encoder for feature extraction, fused with a context extraction module. It relies on Dense Cavity Convolutional Block (DAC module) and Residual Multi-Kernel Pooling (RMP module) to capture more abstract features and preserve spatial information, leading to improved medical image segmentation performance.

Although CNN has been successful in the field of polyp segmentation, it has limitations in acquiring contextual remote information. Transformer, as a powerful image-understanding method, makes up for this deficiency well and is rapidly developing in the field of polyp segmentation. Polyp-pvt (Dong et al., 2021) the first to introduce the Transformer as a feature encoder for polyp segmentation. It integrates high-level semantic and positional information through cascading fusion modules and similarity aggregation modules, effectively suppressing noise in the feature representations. DuAT (Tang et al., 2023), a dual-fusion Transformer network, employs a global-to-local spatial aggregation module to combine global and local spatial features, thereby enabling precise localization of polyps of varying sizes. In addition, it employs a selective boundary aggregation module to fuse the edge information at the bottom layer with the semantic information at the top layer. SSFormer (Wang et al., 2022) combines Segformer (Xie et al., 2021) and Pyramid Vision Transformer as an encoder and introduces a new progressive local decoder to emphasize the local features and alleviate the problem of distraction. TransNetR (Jha et al., 2024) combines the residual network with the Transformer. The combination shows good real-time processing speed and multi-center generalization capability.

2.2 Attention mechanism

By precisely focusing on key regions of an image, the attention mechanism enables deep learning models to identify polyps more efficiently and accurately, particularly in colonoscopy images. Att-UNet (Lian et al., 2018) integrates Attention into UNet and applies it to medical images, and for the first time, incorporates Soft Attention into a CNN network for medical imaging. DCRNet (Yin et al., 2022) proposes a positional attention module to capture pixel-level contextual information. PraNet (Fan et al., 2020) aggregates high-level features using a parallel partial decoder, exploits boundary cues using a reverse attention module, and establishes relationships between regions and boundary. MultiResUNet (Ahamed et al., 2024a) extracts features at different scales through multi-resolution convolutional blocks, and uses attention guidance to enhance focus on polyp regions, significantly improving the segmentation performance of colorectal polyps. CaraNet (Lou et al., 2022) combines axial reverse attention and channel feature pyramid (CFP) modules to improve the segmentation performance of small medical targets. MSRF-NET (Srivastava et al., 2021) uses a dual-scale dense fusion block to exchange multi-scale features with different receptive fields. It maintains the resolution and propagates high-level and low-level features for more accurate segmentation outcomes.

ResNest (Zhang et al., 2022) is an innovative architecture that combines the Residual Network (ResNet) with a split-attention mechanism, and has demonstrated excellent performance in semantic segmentation. By introducing the split-attention module—which effectively integrates grouped convolution with attention mechanisms—ResNeSt enables the network to more effectively capture and utilize both spatial and channel-wise features, while maintaining computational efficiency. However, its application in the field of polyp segmentation has not been explored in depth. In this paper, ResNeSt is employed as an advanced CNN backbone to assess its potential in polyp segmentation tasks and to evaluate the effectiveness and generalizability of the proposed modules.

2.3 Feature fusion

Due to the complex shapes and varying sizes of polyps, effectively fusing multi-scale features can significantly enhance the model’s segmentation performance. DCRNet (Yin et al., 2022) achieves feature enhancement by embedding a contextual relationship matrix and then achieves relationship fusion by region cross-batch memory. MSNet (Zhao et al., 2021) introduces a phase reduction unit to extract differential features between adjacent layers and employs a pyramid structure with varying receptive fields to capture multi-scale information. CFA-Net (Zhou et al., 2023) uses a hierarchical strategy to incorporate edge features into a two-stream segmentation network while using a cross-layer feature fusion module to fuse neighboring features across different levels. Work such as PPNet (Hu et al., 2023) and PolypSeg (Zhong et al., 2020) apply attention mechanisms to enhance feature fusion between the top and bottom layers. Gating mechanisms have also proven effective for feature fusion, as demonstrated by Gated Fully Fusion (Li et al., 2020) and BANet (Lu et al., 2022), which selectively integrate multi-level features through gated fusion. Collectively, these works demonstrate that efficiently fusing and utilizing extracted features is a promising method in polyp segmentation.

3 Methods

In this section, we provide a detailed overview of the architecture of the AFCNet network and its constituent modules. Firstly, the overall structure of the network is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The AFCNet network framework consists of four key parts. The processing pipeline flows from the Encoder Network, to the MDCA, then to the MAFF, and finally to the UFR.

We then describe each component in detail, including the Multi-Scale Depth-wise Convolution Attention Module (MDCA module), the Multi-Scale Adaptive Feature Fusion module (MAFF), and the Upsampling Feature Retrospective Module (UFR).

3.1 Network architecture

The AFCNet we designed follows the classical encoder-decoder architecture. For the encoding part of the model, we employ the traditional CNN network Res2Net50 as the backbone. We use the first three layers of high-level features extracted from the backbone network. Suppose our input polyp segmentation image is

After subsequent enhancement of features by MDCA, the features

3.2 Multi-scale depth-wise convolution attention module

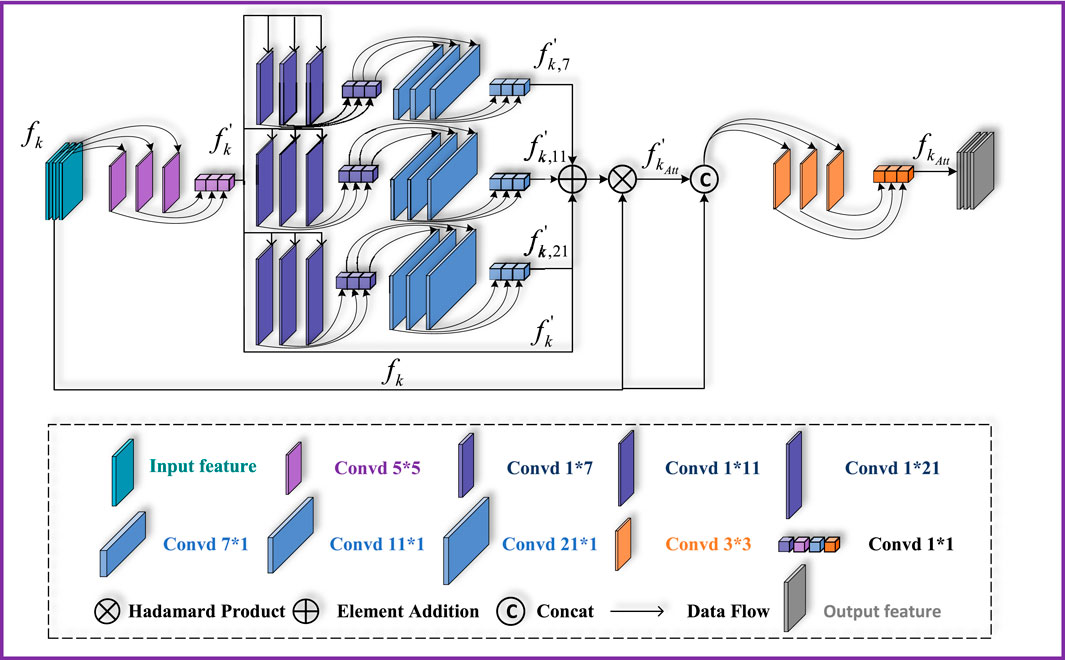

In order to extract more important feature information from different layers, the MDCA module is designed in this paper. This module consists of a multi-branch parallel network and a multi-scale deep convolutional attention mechanism. This module first integrates feature information from multiple receptive fields within each layer, ensuring that the output of each layer simultaneously captures detailed, local contextual, and global semantic information. By introducing an internal multi-scale feature extraction and fusion module prior to inter-level feature fusion, the representation quality and richness of single-layer features are greatly enhanced. This design establishes a progressive fusion paradigm—first optimizing the internal structure and then coordinating external relationships—allowing the network to achieve smoother and more controllable feature evolution from local details to global semantics. Ultimately, this improves both the accuracy of complex boundary segmentation and the model’s generalization ability.

As shown in Figure 2, the features

Figure 2. Structure of the MDCA module. It consists mainly of depth-wise separable convolution and a multi-branch depth-wise dilated convolution structure.

Where

where

3.3 Multi-scale Adaptive Feature Fusion Module

Due to the low contrast between polyps and surrounding tissues in some polyp endoscopic images, features extracted by traditional methods may have difficulty in distinguishing subtle differences between polyps and normal tissues. To fully leverage features at different scales and enhance the richness of feature representation, we propose a Multi-scale Adaptive Feature Fusion (MAFF) module. This method introduces a progressive, hierarchical feature fusion approach. As illustrated in Figure 1, this model establishes a series of intermediate representations between feature layers with significant semantic gaps, using them to guide the information flow with finer granularity between layers. This ensures a smooth transition from spatial details to semantic concepts, helping to alleviate the feature mismatch problem between different semantic levels.

MAFF consists of two main components: a multi-scale fusion cross-network and an Adaptive Multi-scale Feature Harmonization module. The multi-scale fusion cross-network realizes dynamic interaction and complementarity between different scale features through its unique structure, providing a basis for the model to capture rich, multi-level information. At the core of MAFF is the Adaptive Multi-Scale Feature Harmonization module, which comprises two distinct operations: a feature addition unit and a feature subtraction unit. Feature addition is a commonly used feature enhancement algorithm in the image domain, and in our module, the common information present in different levels of features is highlighted by performing addition operations on the features at different levels. The opposite feature subtraction unit is able to highlight the differences in information between features at different levels. In order to fully fuse these two complementary feature information, we introduce a trainable weighting ratio parameter,

The MAFF module receives inputs

This process can be mathematically expressed in Equations 12–14:

where

We then put the aligned features into the AMFH (Adaptive Multi-scale Feature Harmonization) module. AMFH fuses two different features by feature addition and subtraction in order to efficiently capture the complementary information between different layers of features, highlight the subtle differences between them, and strengthen the module’s sensitivity to edges, textures, and other key visual details. We then enable the module to dynamically balance the effects of addition and subtraction operations on the final feature representation by introducing an adaptive weighting mechanism. This adaptivity is based on the unique properties of the input features and their contextual information, and the optimization of the weights is performed automatically. With the adaptive adjustment of the weights of addition and subtraction operations, the AMFH module takes full advantage of the complementary strengths of these two operations to produce feature representations that are rich and fine-grained. We use

where

3.4 Upsampling Feature Retrospective Module

After obtaining the fused features, in order to dynamically adjust the amount of information fused in each scale so as to realize more effective information integration, reduce spatial distortion, and enhance the semantic expression of the features in multi-scale feature fusion. We have designed the Up-sampling Feature Retrospective Module (UFR) based on the idea of the Gate Recurrent Unit (GRU). As shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Upsampling Feature Retrospective Module structure. It consisits Update gate unit, reset gate unit and dense connections,the module uses a bilinear interpolation method to upsample features.

In the gated loop unit, the gating mechanism is used to control the flow of information through the sequence model. We input different levels of features into the UFR module, respectively. The UFR module consists of an update gate module and a reset gate module, as well as a dense connection, which performs correlation enhancement of the different levels of features through update gates and reset gates. We set the two inputs of the module to be two neighboring features of different levels: X and Y. Then the update gates and the reset gates are computed by the following Equations 17–20:

where

In our module, we up-sample the bottom layer features by using linear interpolation so as to align with the dimensions of the top layer features. We define the above computational process as the

where

4 Experiment, result and discussion

In this section, we provide detailed descriptions of our experiments, including the datasets used and the experimental results. This includes comparisons with 11 widely used methods as benchmarks, along with ablation studies and generalization experiments to validate the effectiveness of our approach.

4.1 Experiment

4.1.1 Dataset

According to the (Mei et al., 2023), we selected five publicly available datasets commonly used in the field of polyp segmentation: Kvasir-SEG, CVC-ClinicDB, CVC-ColonDB, CVC-300, and ETIS.

Kvasir-SEG (Jha et al., 2020): It is an open-access dataset of gastrointestinal polyp images and the corresponding segmentation masks, manually annotated and verified by an experienced gastroenterologist. It contains 1,000 polyp images and their corresponding ground truth from the Kvasir-SEG Dataset v2. The resolution of the images contained in Kvasir-SEG varies from 332 × 487 to 1920 × 1,072 pixels.

CVC-ClinicDB (Bernal et al., 2015): CVC-ClinicDB is a database of frames extracted from colonoscopy videos. These frames contain several examples of polyps. The CVC-ClinicDB dataset contains 612 images cut from 25 colonoscopy videos with an image size of 384

CVC-ColonDB (Tajbakhsh et al., 2015): The CVC-ColonDB dataset consists of 380 images cut from 15 colonoscopy videos with an image size of 574

ETIS (Silva et al., 2014): ETIS contains 196 images cut from 34 colonoscopy videos with the image size of 1,225

CVC-300 (Vázquez et al., 2017): includes 60 colonoscopy images with a resolution of 500

To evaluate the segmentation performance of the method, we conducted experiments on two polyp segmentation datasets, Kvasir-SEG and CVC-ClinicDB. For each dataset, we randomly divided it into two subsets: 90

4.1.2 Training setup and experimental metrics

All of our experimental models are implemented under pytorch 2.0.0 and trained for 200 epochs on an RTX4090 graphics card with 24G of memory. Throughout the training regimen, we use four basic data augmentation techniques, random rotations, horizontal flips, vertical flips, and coarse masking, to enhance the model’s robustness to variations in the input data. And we use an Adam optimiser with the learning rate of 1e-4 and use the ReduceLROnPlateau learning rate scheduler. In our experiments, four separate experiments are conducted for each model, using four fixed random seeds: 42, 8, 36, and 120. The hyperparameters used in experiments are illustrated in Table 2. In the paper, all experimental data in the tables, unless otherwise specified, are the averages of these four experiments, with the variance calculated.

We combine cross-entropy loss and Dice loss as our assessment metrics for the loss function. To validate the effectiveness of our model, we have selected five metrics to evaluate the model’s performance from multiple perspectives: Dice Similarity Coefficient (Dice), Intersection over Union of polyp (IoUp), recall, Accuracy (ACC), and True Negative Ratio (TNR). Let FN, FP, TN, and TP denote false negatives, false positives, true negatives, and true positives, respectively. By definition, Dice, IoUp, recall, ACC, and TNR can be calculated by following Equations 25–29:

Generally, a superior segmentation method has larger values of Dice and IoUp.

4.2 Result

4.2.1 Comparisons with state-of-the-art methods

To ensure an objective comparison, all the tested methods are selected from open-source works. Specifically, we select the following networks including Unet++ (Zhou et al., 2019), Unet3+ (Huang et al., 2020), Attention-UNet (Lian et al., 2018) (AttUNet), Context Encoder Network (Gu et al., 2019) (CENet), Local Global Interaction Network (Liu et al., 2023) (LGINet), Multi-scale Subtraction Network (Zhao et al., 2021) (MSNet), Duplex Contextual Relation Network (Yin et al., 2022) (DCRNet), Dual-Aggregation Transformer Network (Tang et al., 2023) (DuAT), Polyp-pvt (Dong et al., 2021), Transformer-based Residual Network (Jha et al., 2024) (TransNetR), Context axial reverse attention network (CaraNet) (Lou et al., 2022), as 11 state-of-the-art segmentation methods for comparison. To verify the validity of the correction, we performed a t-test between the state-of-the-art AFCNet and the three models that worked best in the other comparison experiments and calculated the p-value.

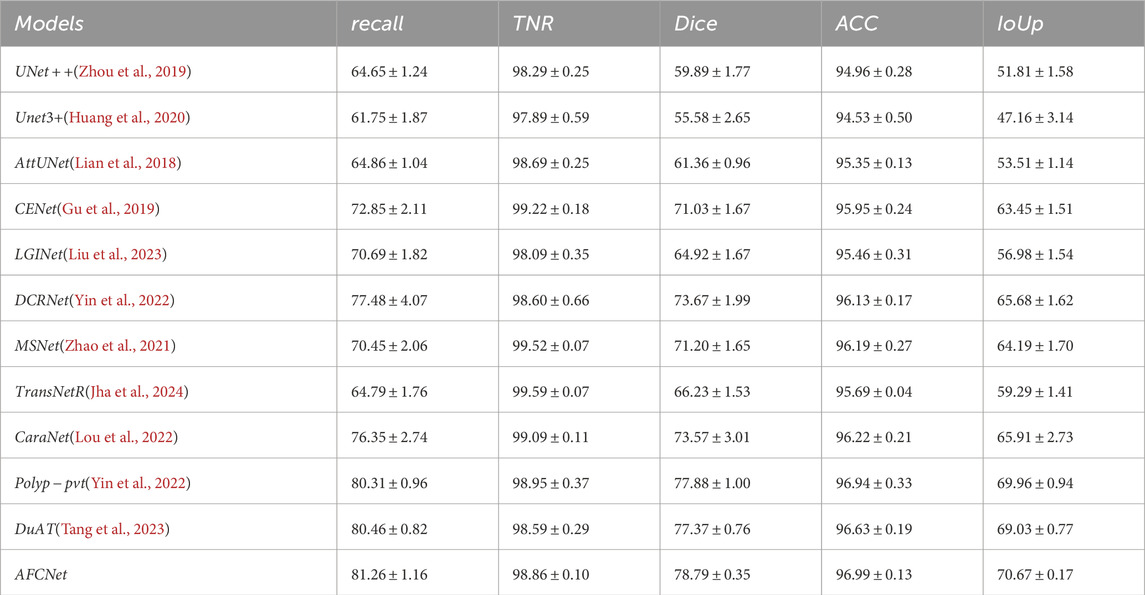

Specifically, the results in Table 3 show that our model achieved performance improvements of at least 1.72

Table 3. Comparison of our designed model AFCNet with currently popular methods on the CVC-ClinicDB dataset.([In %] and “

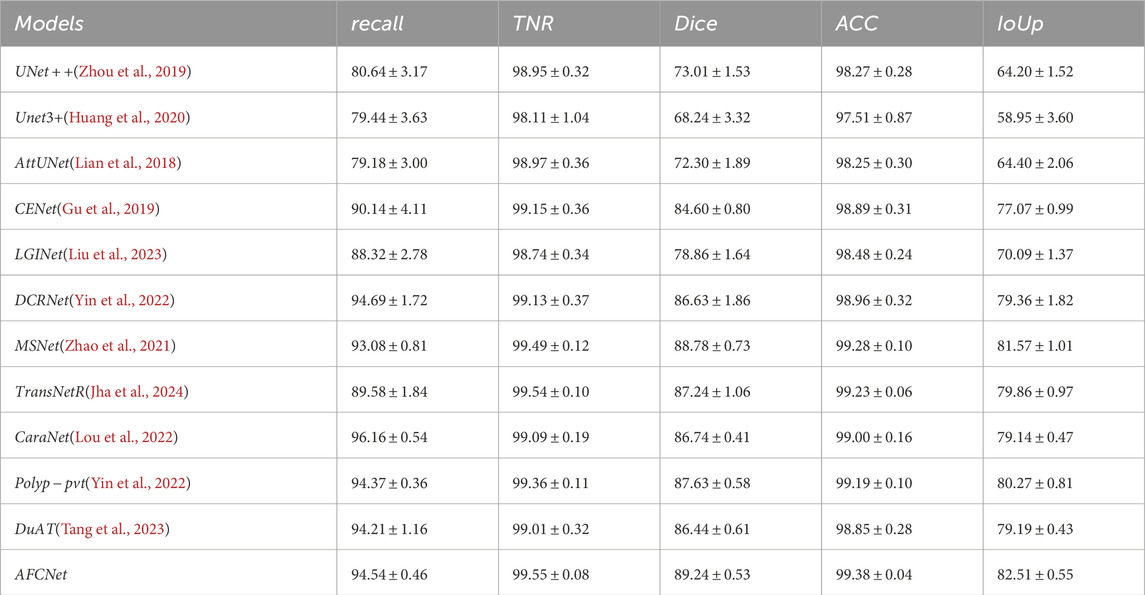

As shown in Table 4, AFCNet also demonstrated better performance on the Kvasir-SEG dataset, achieving improvements of 0.57

Table 4. Comparison of our designed model AFCNet with currently popular methods on the Kvasir-SEG dataset.([In %] and “

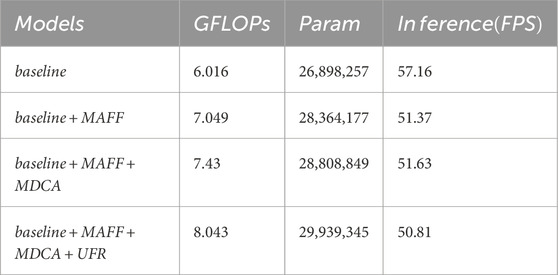

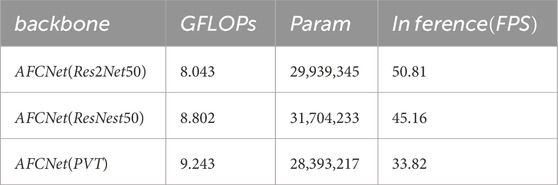

Table 5. Computational efficiency comparison of AFCNet with different backbone networks. The table shows the computational complexity (GFLOPs), number of parameters, and inference speed (frames per second) for each configuration.

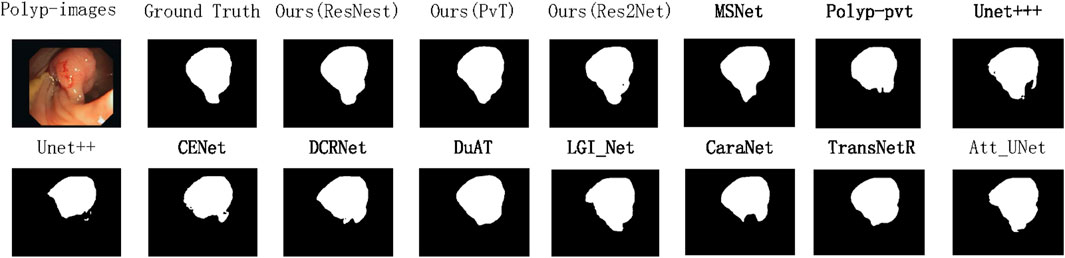

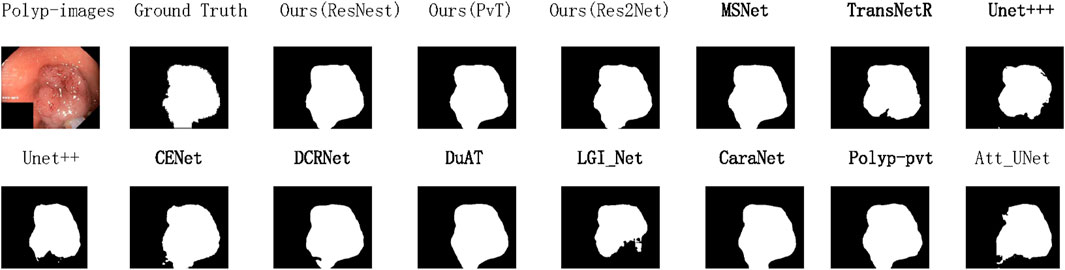

To demonstrate the state-of-the-art performance of our model, Figure 4 presents the variation curves of two key metrics (IoU and Dice) when using different backbone networks as the encoder. The results are categorized into two main groups: CNN-based backbones and Transformer-based backbones. For each category, we include performance curves of our model along with two state-of-the-art models using the same backbone technology and the baseline model for comparison. The curves clearly show that our model achieves optimal performance regardless of the backbone architecture. Based on previous experimental findings, our model demonstrates the best results when employing PVT as the backbone network. Therefore, for the data generalization experiments, we directly use the PVT-based configuration to compare with other models, as shown in Figures 5, 6. The polyps in the selected images exhibit characteristics such as irregular shapes, the presence of bubbles, and complex backgrounds.

Figure 4. Change curves for the two KPIs when modeled using different backbones as encoders, as well as for the baseline model and two advanced models using the corresponding backbones on CVC-ClinicDB dataset.

Figure 5. Qualitative results are used to compare the ground truth, our three methods, and eleven state-of-the-art methods on CVC-ClinicDB datasets.

Figure 6. Qualitative results are used to compare the ground truth, our three methods, and eleven state-of-the-art methods on Kvasir-SEG datasets.

To further evaluate the computational efficiency, we conducted comprehensive analyses on three backbone variants of AFCNet (Res2Net50, ResNest50, and PVT). As shown in Table 5, we systematically measured and compared several key metrics including parameter counts, computational complexity (GFLOPs), and inference speed (FPS) on GPU platforms. Additionally, we specifically analyzed the computational overhead of key components (MDCA, MAFF, and UFR modules) in Table 6. The experimental results demonstrate that while these modules introduce certain computational costs, they maintain an excellent balance between performance improvement and computational expense. These supplementary experiments not only validate AFCNet’s superiority in segmentation accuracy but also confirm its clinical applicability in terms of computational efficiency.

4.2.2 Generalisability experiments

The generalization ability of Computer-Aided Diagnosis (CAD) systems is crucial in clinical applications. To validate the generalization ability of AFCNet, we followed the experimental methodology of PraNet (Fan et al., 2020). We selected 550 images from CVC ClinicDB and 900 images from Kvasir, forming a training set of 1,450 images. To verify the network’s generalization performance, we used the entire ETIS, CVC ColonDB, and CVC-300 datasets as unseen data for testing. As shown in Table 7, Tables 8, 9, relative to the current popular networks, AFCNet improves Dice by 3.73

Table 7. Comparison of our designed model AFCNet with currently popular methods on the CVC-ColonDB dataset.([In %] and “

Table 8. Comparison of our designed model AFCNet with currently popular methods on the ETIS dataset.([In %] and “

Table 9. Comparison of our designed model AFCNet with currently popular methods on the CVC-300 dataset. ([In %] and “

4.2.3 Ablation experiments

To systematically validate the effectiveness of each module, we designed a dual ablation study scheme:

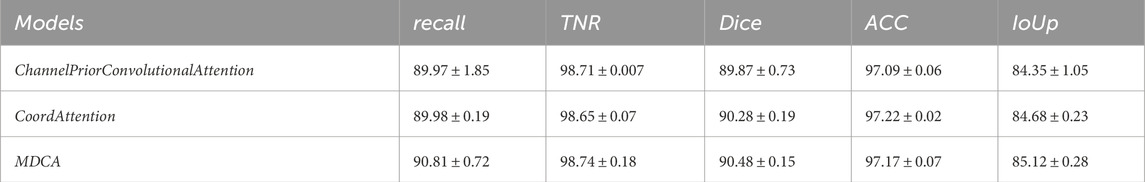

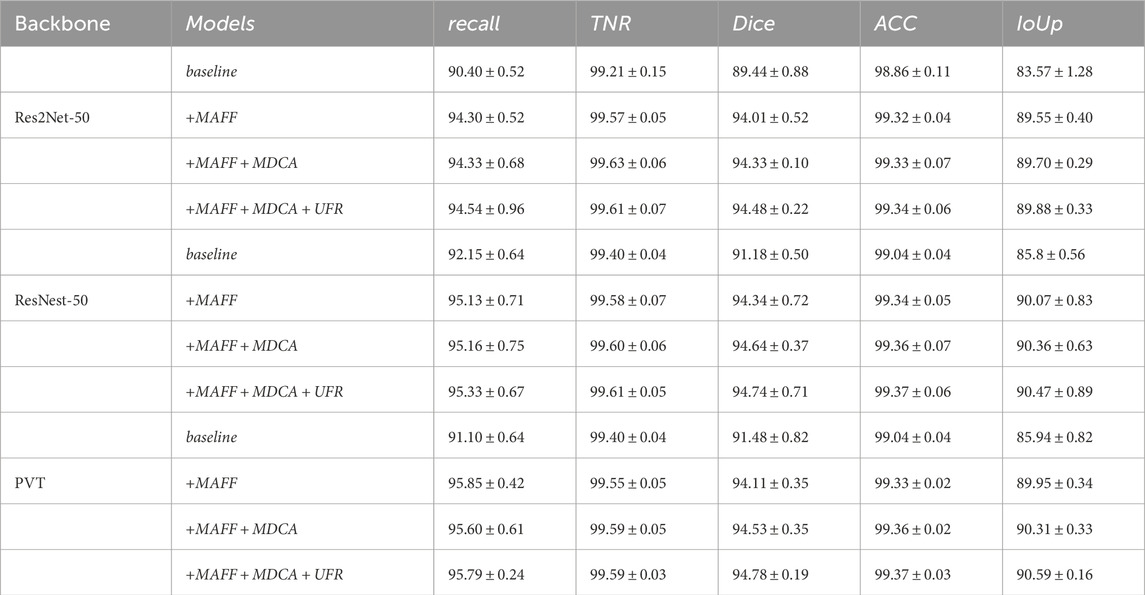

We systematically integrated all proposed modules into three backbone networks (Res2Net50, ResNest50, and PvT2) to validate the architecture’s overall compatibility. All experiments were performed on the CVC-ClinicDB and Kvasir-SEG datasets. While preserving the complete hierarchical structure of the feature extraction backbone, we initially removed all modules to maintain only the basic U-shaped encoder-decoder framework, then sequentially incorporated the MAFF module, MDCA module, and UFR module. To specifically verify the effectiveness of the MAFF module’s structure, we conducted simplified ablation studies on the Res2Net50 backbone network followed by comprehensive experimental analysis. The results illustrated in Tables 10–13 are all obtained when Res2Net50 is backbone network.

Table 10. Ablation study of MAFF module variants on the ClinicDB dataset. ([In %] and “

Table 11. Ablation study of MAFF module variants on the Kvasir-SEG dataset. ([In %] and “

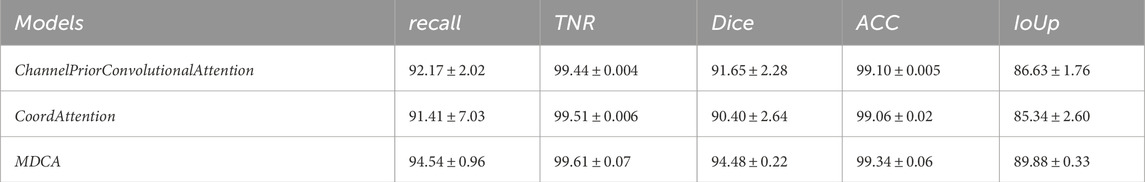

Table 12. Performance comparison of segmentation using MDCA, CPCA, and CoordAttention on CVC-CLinicDB dataset. ([In %] and “

Table 13. Performance comparison of segmentation using MDCA, CPCA, and CoordAttention on the CVC-CLinicDB dataset. ([In %] and “

4.2.3.1 Effectiveness of MAFF module

In order to verify the effectiveness of the MAFF module in the model, we input the multilayer features extracted from the backbone network directly into the MAFF module and then up-sampled them directly. As can be seen from Table 14, all the metrics of the model with the addition of the MAFF module are significantly better than the baseline model, both on different datasets and different backbone network architectures. This is because the MAFF module is able to dynamically balance the impact of the two feature fusion methods on the final feature representation through the trainable parameters, thus making the two methods complementary to each other.

Table 14. Ablation study for the various modules with different backbone on the Kvasir-SEG dataset. ([In %] and “

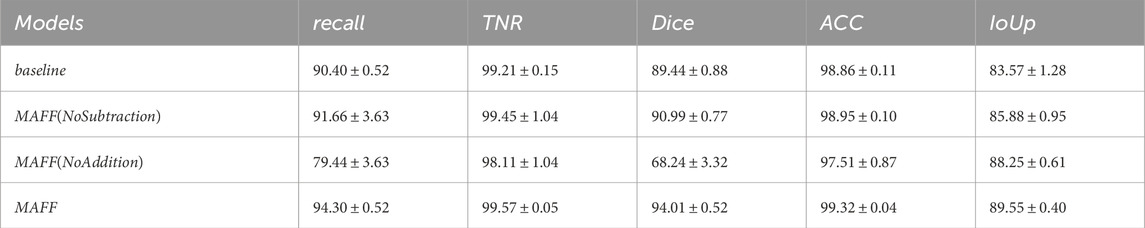

The MAFF module is validated as an effective multi-scale feature fusion method. In addition to this basic ablation experiment, in order to explore the structural validity of the MAFF module, we conducted systematic ablation experiments comparing three configurations: (1) the baseline model without MAFF, (2) MAFF with only additive units, and (3) MAFF with only subtractive units. The experimental results from Tables 10, 11 show that the full MAFF module significantly outperforms the variant model in all evaluation metrics (ClinicDB dataset: 4.57

4.2.3.2 Effectiveness of the MDCA module

After the model is added to the MDCA module, as shown in Tables 14, 15, the segmentation ability of the model has a more obvious improvement, which indicates that the important information in the image can be well extracted by our MDCA module, this is because the convolution with different orientations and sizes can capture a wider range of feature information, and is more sensitive to the targets with complex shapes, and can also be used with the MAFF module’s fusion mechanism, thus enhancing the model’s ability to represent image details and context.

Table 15. Ablation study for the various modules with different backbone on Kvasir-SEG dataset. ([In %] and “

To validate the effectiveness of the MDCA module in multi-scale feature extraction, we designed a comparative experiment. In this experiment, while keeping the network structure unchanged, the MDCA module was replaced with the CPCA and CoordAttention modules for performance comparison. As shown in Tables 12, 13, the experimental results demonstrate that MDCA outperforms the competing methods in polyp boundary segmentation accuracy. This highlights the superiority of our design for complex medical image segmentation tasks.

4.2.3.3 Effectiveness of the UFR module

The UFR module filters the information in the up-sampling stage through the gating mechanism, and in terms of the model effect, Tables 14, 15 demonstrates that the UFR can filter and fuse the fused features very well, so as to optimize the segmentation capability of the model in a stable manner.

4.3 Discussion

The proposed architecture in this paper is an end-to-end processing framework, meaning that image analysis is completed within a single framework (Biju et al., 2024). An alternative approach employs a step-by-step construction of deep learning models, such as preprocessing the image before performing the analysis (Qian et al., 2020; Vijayalakshmi and Sasithradevi, 2024). Both methods have their advantages. End-to-end deep learning models reduce the complexity of intermediate steps and make more efficient use of computational and memory resources. Step-by-step deep learning models, on the other hand, offer better interpretability, task flexibility, and advantages in modular expansion. Future research could focus on further integrating the strengths of both paradigms to develop hybrid systems that are flexible and robust.

This work was trained and tested on an RTX 4090 GPU, a type of hardware that is still not feasible to deploy on many resource-constrained embedded platforms. Therefore, another important issue for future research is how to effectively improve the execution efficiency of polyp segmentation methods, in order to further reduce their operational costs and enhance real-time performance. Compression techniques, such as quantization and pruning (Frantar et al., 2022), along with the use of lightweight architectures (Ahamed et al., 2023b; Ahamed et al., 2025), can help reduce model size by exploiting the sparsity of effective model parameters. However, relying on a single model attribute for performance optimization has its limitations. A more comprehensive approach that integrates multiple optimization strategies is likely to yield better results. For example, in PowerInfer (Song et al., 2024), the authors successfully combined the model’s sparsity with the challenge of efficiently deploying the model across heterogeneous resources, achieving significant performance improvements. Our future work will also focus on exploring hybrid techniques for model optimization.

5 Conclusion

This paper proposes a novel polyp segmentation network, AFCNet. It is based on convolutional attention and adaptive multi-scale feature fusion. In the feature extraction and enhancement stage, the MDCA module captures broader contextual information from images. At the same time, it increases the weights of important features. By simplifying the deepest layer features in the backbone network, a more efficient architecture is achieved. During the feature fusion stage, the MAFF module integrates features from different layers. It dynamically balances multiple fusion strategies. This process continuously improves the model’s ability to capture both global and detailed information. Therefore, superior multi-scale feature fusion performance is achieved. In the upsampling stage, the UFR module filters and guides the final fused features. In the experimental section, we compare our method with 11 state-of-the-art polyp segmentation approaches. We also evaluate the module’s generalizability by integrating it with different backbone networks. The results demonstrate that our method achieves the best performance. It also maintains excellent generalization and adaptability.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

BJ: Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft. YZ: Writing – review and editing. QN: Investigation, Software, Writing – review and editing. LQ: Writing – review and editing. WQ: Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work is partially supported by the Key Research and Development Program of LiaoNing Province (No.2024JH2/102500076), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (N25BJD013).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahamed M. F., Hossain M. M., Nahiduzzaman M., Islam M. R., Islam M. R., Ahsan M., et al. (2023a). A review on brain tumor segmentation based on deep learning methods with federated learning techniques. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 110, 102313. doi:10.1016/j.compmedimag.2023.102313

Ahamed M. F., Syfullah M. K., Sarkar O., Islam M. T., Nahiduzzaman M., Islam M. R., et al. (2023b). Irv2-net: a deep learning framework for enhanced polyp segmentation performance integrating inceptionresnetv2 and unet architecture with test time augmentation techniques. Sensors 23, 7724. doi:10.3390/s23187724

Ahamed M. F., Islam M. R., Nahiduzzaman M., Chowdhury M. E., Alqahtani A., Murugappan M. (2024a). Automated colorectal polyps detection from endoscopic images using multiresunet framework with attention guided segmentation. Human-Centric Intell. Syst. 4, 299–315. doi:10.1007/s44230-024-00067-1

Ahamed M. F., Islam M. R., Nahiduzzaman M., Karim M. J., Ayari M. A., Khandakar A. (2024b). Automated detection of colorectal polyp utilizing deep learning methods with explainable ai. IEEE Access 12, 78074–78100. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3402818

Ahamed M. F., Shafi F. B., Nahiduzzaman M., Ayari M. A., Khandakar A. (2025). Interpretable deep learning architecture for gastrointestinal disease detection: a tri-stage approach with pca and xai. Comput. Biol. Med. 185, 109503. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.109503

Bernal J., Sánchez F. J., Fernández-Esparrach G., Gil D., Rodríguez C., Vilariño F. (2015). Wm-dova maps for accurate polyp highlighting in colonoscopy: validation vs. saliency maps from physicians. Comput. Medical Imaging Graphics 43, 99–111. doi:10.1016/j.compmedimag.2015.02.007

Biju J., Mathew R. S., Poulose A. (2024). “Revolutionizing endoscopic diagnostics: a comparative study of dc-unet and mc-unet. 2024 International Conference on Brain Computer Interface and Healthcare Technologies (iCon-BCIHT), Thiruvananthapuram, India, 19-20 December 2024 (IEEE), 11–16.

Bresson X., Esedoḡlu S., Vandergheynst P., Thiran J.-P., Osher S. (2007). Fast global minimization of the active contour/snake model. J. Math. Imaging Vision 28, 151–167. doi:10.1007/s10851-007-0002-0

Dong B., Wang W., Fan D.-P., Li J., Fu H., Shao L. (2021). Polyp-pvt: polyp segmentation with pyramid vision transformers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.06932

Fan D.-P., Ji G.-P., Zhou T., Chen G., Fu H., Shen J., et al. (2020). “Pranet: parallel reverse attention network for polyp segmentation,” in International conference on medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention (Springer), 263–273.

Frantar E., Ashkboos S., Hoefler T., Alistarh D. (2022). Gptq: accurate post-training quantization for generative pre-trained transformers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.17323

Gu Z., Cheng J., Fu H., Zhou K., Hao H., Zhao Y., et al. (2019). Ce-net: context encoder network for 2d medical image segmentation. IEEE Transactions Medical Imaging 38, 2281–2292. doi:10.1109/TMI.2019.2903562

Guo X., Yang C., Liu Y., Yuan Y. (2020). Learn to threshold: thresholdnet with confidence-guided manifold mixup for polyp segmentation. IEEE Transactions Medical Imaging 40, 1134–1146. doi:10.1109/TMI.2020.3046843

Hu K., Chen W., Sun Y., Hu X., Zhou Q., Zheng Z. (2023). Ppnet: pyramid pooling based network for polyp segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 160, 107028. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.107028

Huang H., Lin L., Tong R., Hu H., Zhang Q., Iwamoto Y., et al. (2020). “Unet 3+: a full-scale connected unet for medical image segmentation,” in ICASSP 2020-2020 IEEE international conference on acoustics, speech and signal processing (ICASSP) (IEEE), 1055–1059.

Jha D., Smedsrud P. H., Riegler M. A., Halvorsen P., De Lange T., Johansen D., et al. (2020). “Kvasir-seg: a segmented polyp dataset,” in MultiMedia Modeling: 26th International Conference, MMM 2020, Daejeon, South Korea, January 5–8, 2020 (Springer), 451–462.

Jha D., Tomar N. K., Sharma V., Bagci U. (2024). “Transnetr: transformer-based residual network for polyp segmentation with multi-center out-of-distribution testing,” in Medical imaging with deep learning (PMLR), 1372–1384.

Jia X., Xing X., Yuan Y., Xing L., Meng M. Q.-H. (2019). Wireless capsule endoscopy: a new tool for cancer screening in the colon with deep-learning-based polyp recognition. Proc. IEEE 108, 178–197. doi:10.1109/jproc.2019.2950506

Li X., Zhao H., Han L., Tong Y., Tan S., Yang K. (2020). Gated fully fusion for semantic segmentation. Proc. AAAI Conference Artificial Intelligence 34, 11418–11425. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i07.6805

Lian S., Luo Z., Zhong Z., Lin X., Su S., Li S. (2018). Attention guided u-net for accurate iris segmentation. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 56, 296–304. doi:10.1016/j.jvcir.2018.10.001

Liu L., Li Y., Wu Y., Ren L., Wang G. (2023). Lgi net: enhancing local-global information interaction for medical image segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 167, 107627. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.107627

Lou A., Guan S., Ko H., Loew M. H. (2022). Caranet: context axial reverse attention network for segmentation of small medical objects. Med. Imaging 2022 Image Process. (SPIE) 12032, 81–92.

Lu L., Zhou X., Chen S., Chen Z., Yu J., Tang H., et al. (2022). “Boundary-aware polyp segmentation network,” in Chinese conference on pattern recognition and computer vision (PRCV) (Springer), 66–77.

Mei J., Zhou T., Huang K., Zhang Y., Zhou Y., Wu Y., et al. (2023). A survey on deep learning for polyp segmentation: techniques, challenges and future trends. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.18373

Patel K., Bur A. M., Wang G. (2021). “Enhanced u-net: a feature enhancement network for polyp segmentation,” in 2021 18th conference on robots and vision (CRV) (IEEE), 181–188.

Peng C., Qian Z., Wang K., Zhang L., Luo Q., Bi Z., et al. (2024). Mugennet: a novel combined convolution neural network and transformer network with application in colonic polyp image segmentation. Sensors 24, 7473. doi:10.3390/s24237473

Pohle R., Toennies K. D. (2001). Segmentation of medical images using adaptive region growing. Med. Imaging 2001 Image Process. (SPIE) 4322, 1337–1346. doi:10.1117/12.431013

Qian Z., Lv Y., Lv D., Gu H., Wang K., Zhang W., et al. (2020). A new approach to polyp detection by pre-processing of images and enhanced faster r-cnn. IEEE Sensors J. 21, 11374–11381. doi:10.1109/jsen.2020.3036005

Ronneberger O., Fischer P., Brox T. (2015). “U-net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation,” in Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th international conference, Munich, Germany, October 5-9, 2015 (Springer), 234–241.

Silva J., Histace A., Romain O., Dray X., Granado B. (2014). Toward embedded detection of polyps in wce images for early diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Int. Journal Computer Assisted Radiology Surgery 9, 283–293. doi:10.1007/s11548-013-0926-3

Song P., Li J., Fan H. (2022). Attention based multi-scale parallel network for polyp segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 146, 105476. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105476

Song Y., Mi Z., Xie H., Chen H. (2024). “Powerinfer: fast large language model serving with a consumer-grade gpu,” in Proceedings of the ACM SIGOPS 30th symposium on operating systems principles, 590–606.

Srivastava A., Jha D., Chanda S., Pal U., Johansen H. D., Johansen D., et al. (2021). Msrf-net: a multi-scale residual fusion network for biomedical image segmentation. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 26, 2252–2263. doi:10.1109/jbhi.2021.3138024

Tajbakhsh N., Gurudu S. R., Liang J. (2015). Automated polyp detection in colonoscopy videos using shape and context information. IEEE Transactions Medical Imaging 35, 630–644. doi:10.1109/TMI.2015.2487997

Tang F., Xu Z., Huang Q., Wang J., Hou X., Su J., et al. (2023). “Duat: dual-aggregation transformer network for medical image segmentation,” in Chinese conference on pattern recognition and computer vision (PRCV) (Springer), 343–356.

Vala H. J., Baxi A. (2013). “A review on otsu image segmentation algorithm,” in International journal of advanced research in computer engineering and technology (IJARCET), 2, 387–389.

Vázquez D., Bernal J., Sánchez F. J., Fernández-Esparrach G., López A. M., Romero A., et al. (2017). A benchmark for endoluminal scene segmentation of colonoscopy images. J. Healthcare Engineering 2017, 4037190. doi:10.1155/2017/4037190

Vijayalakshmi M., Sasithradevi A. (2024). A comprehensive review on deep learning architecture for pre-processing of underwater images. SN Comput. Sci. 5, 472. doi:10.1007/s42979-024-02847-9

Wang J., Huang Q., Tang F., Meng J., Su J., Song S. (2022). “Stepwise feature fusion: local guides global,” in International conference on medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention (Springer), 110–120.

Wu C., Long C., Li S., Yang J., Jiang F., Zhou R. (2022). Msraformer: multiscale spatial reverse attention network for polyp segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 151, 106274. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.106274

Xie E., Wang W., Yu Z., Anandkumar A., Alvarez J. M., Luo P. (2021). Segformer: simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. Adv. Neural Information Processing Systems 34, 12077–12090.

Yin Z., Liang K., Ma Z., Guo J. (2022). “Duplex contextual relation network for polyp segmentation,” in 2022 IEEE 19th international symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBI), Location: Kolkata, India, 28-31 March 2022 (IEEE), 1–5.

Zhang R., Li G., Li Z., Cui S., Qian D., Yu Y. (2020). “Adaptive context selection for polyp segmentation,” in Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2020: 23rd International Conference, Lima, Peru, October 4–8, 2020 (Springer), 253–262.

Zhang H., Wu C., Zhang Z., Zhu Y., Lin H., Zhang Z., et al. (2022). “Resnest: split-attention networks,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19-20 June 2022 (IEEE), 2736–2746.

Zhao X., Zhang L., Lu H. (2021). “Automatic polyp segmentation via multi-scale subtraction network,” in Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2021: 24th International Conference, Strasbourg, France, September 27–October 1, 2021 (Springer), 120–130.

Zhong J., Wang W., Wu H., Wen Z., Qin J. (2020). “Polypseg: an efficient context-aware network for polyp segmentation from colonoscopy videos,” in Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2020: 23rd International Conference, Lima, Peru, October 4–8, 2020 (Springer), 285–294.

Zhou Z., Rahman Siddiquee M. M., Tajbakhsh N., Liang J. (2018). “Unet++: a nested u-net architecture for medical image segmentation,” in International workshop on deep learning in medical image analysis (Springer), 3–11.

Zhou Z., Siddiquee M. M. R., Tajbakhsh N., Liang J. (2019). Unet++: redesigning skip connections to exploit multiscale features in image segmentation. IEEE Transactions Medical Imaging 39, 1856–1867. doi:10.1109/TMI.2019.2959609

Zhou T., Zhou Y., He K., Gong C., Yang J., Fu H., et al. (2023). Cross-level feature aggregation network for polyp segmentation. Pattern Recognit. 140, 109555. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2023.109555

Keywords: adaptive feature fusion, convolutional attention, depth-wise separable convolution, gating units, polyp segmentation

Citation: Jin B, Zhang Y, Nie Q, Qi L and Qian W (2026) An adaptive fusion of composite attention convolutional neural network for polyp image segmentation. Front. Physiol. 16:1678403. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2025.1678403

Received: 02 August 2025; Accepted: 05 December 2025;

Published: 07 January 2026.

Edited by:

Camilla Scapicchio, National Institute of Nuclear Physics of Pisa, ItalyReviewed by:

Alwin Poulose, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Thiruvananthapuram, IndiaW.J. Zhang, University of Saskatchewan, Canada

Jing Zhang, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, United States

Copyright © 2026 Jin, Zhang, Nie, Qi and Qian. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yi Zhang, emhhbmd5aUBtYWlsLm5ldS5lZHUuY24=

Bojiao Jin

Bojiao Jin Yi Zhang

Yi Zhang Lin Qi

Lin Qi