- 1Faculty of Sports Science, Ningbo University, Ningbo, China

- 2Department of Sports Science, Faculty of Physical Education, Sports, and Health, Srinakharinwirot University, Bangkok, Thailand

- 3Department of Physical Education, Ningbo University of Technology, Ningbo, China

Objective: This meta-analysis aimed to systematically evaluate the effects of post-activation potentiation enhancement (PAPE) on jump performance and explore its optimal induction strategies.

Methods: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the influence of PAPE training on jump performance were retrieved from Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and EBSCO. Literature screening was conducted using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool. Quality assessment and statistical analyses were performed using RevMan 5.4 software, while sensitivity analysis and funnel plots were employed to evaluate result stability and publication bias.

Results: A total of 22 RCTs involving 468 participants were included. The meta-analysis demonstrated that PAPE significantly improved jump performance [SMD = 1.36, 95% CI (0.89, 1.83), P < 0.0001]. Subgroup analysis indicated that exercise intensity might be a source of heterogeneity across studies.The largest effect sizes with statistical significance were observed in the following subgroups: exercise mode (Back squat) [SMD = 2.85, 95% CI (0.98, 4.73), P = 0.003], gender (Male) [SMD = 1.53, 95% CI (0.92, 2.14), P < 0.0001], outcome extracted (Counter movement jump) [SMD = 1.34, 95% CI (0.86, 1.81), P < 0.0001], exercise intensity (Moderate Intensity) [SMD = 2.46, 95% CI (1.71, 3.22), P < 0.0001], and rest interval (3–7 min) [SMD = 1.47, 95% CI (0.79, 2.14), P < 0.0001].

Conclusion: PAPE may serve as a potentially effective strategy for enhancing jumping performance under appropriate conditions. In exercises aimed at improving jumping performance, back squats and medium-intensity induction appear to yield the most pronounced benefits. A 3–7 min recovery interval works best, though adjustments should be made based on individual exercise factors.

Systematic Review Registration: http://inplasy.com, identifier INPLASY202430008.

1 Introduction

Jumping performance is a critical core athletic indicator in multiple competitive sports and recreational physical activities (Bazanov et al., 2019). Its level not only directly determines athletes’ competitive rankings and tactical execution efficiency but also serves as a key benchmark for evaluating lower limb explosive strength, neuromuscular coordination, and functional movement capacity (Wang et al., 2021). With the advancement of evidence-based sports training, optimizing jumping performance through non-invasive, time-efficient intervention strategies has become a frontier focus in sports physiology and exercise training science (Batista et al., 2011). Post-activation potentiation enhancement (PAPE) is defined as a transient physiological phenomenon wherein short-duration, high-intensity preconditioning stimuli induce acute improvements in subsequent explosive motor performance (Masagca, 2024). Due to its advantages of no additional training load burden and rapid neuromuscular optimization, PAPE has emerged as a promising strategy for enhancing jumping performance, providing crucial theoretical support for designing pre-competition warm-up protocols and in-season training microcycles in jumping-dominant sports (Yu et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2023).

The physiological mechanisms underlying PAPE primarily involve enhanced calcium ion release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (Ishii et al., 2023), improved actin-myosin cross-bridge cycling efficiency (Mckiel et al., 2024), upregulated α-motor neuron excitability (Dos et al., 2023), and increased muscle-tendon unit stiffness (Wang et al., 2023). However, the magnitude and sustainability of PAPE effects are highly dependent on the design of preconditioning stimuli (Liu et al., 2024). Despite extensive empirical research on PAPE-induced jumping performance improvements (Cui et al., 2024), existing studies exhibit substantial heterogeneity in intervention outcomes, primarily attributed to inconsistent manipulation of key variables: load intensity (30%–100% 1RM), load volume (3–10 repetitions), recovery time (2–20 min), and subject characteristics (e.g., training experience, muscle fiber type distribution) (Yu et al., 2024). Current mainstream PAPE induction methods include loaded resistance exercises (e.g., back squats, Romanian deadlifts), explosive plyometric movements (e.g., medicine ball throws, drop jumps) (Li et al., 2024), and isometric contractions (e.g., static squat holds, hip thrusts) (Terbalyan et al., 2025). These methods differ significantly in neuromuscular activation patterns (e.g., rate of force development, RFD; electromyographic amplitude, EMG) and metabolic responses (e.g., lactate accumulation, oxygen consumption) (Beattie et al., 2014), but their differential effects on specific jumping metrics (vertical jump height, VJ; counter movement jump, CMJ; peak power) remain poorly characterized.

Scientific warm-up protocols are well-documented to mitigate injury risk and enhance acute athletic performance (Zhou et al., 2024). Integrating PAPE into warm-up procedures to shorten pre-competition preparation time and optimize high-intensity exercise capacity has important theoretical and practical implications for competitive sports (Ewertowska et al., 2023). However, three critical research gaps persist in the current literature: (1) no consensus has been reached on which PAPE induction method yields the most robust and consistent improvements in jumping performance, particularly across different jumping types (e.g., CMJ); (2) the interaction between induction method and recovery time—i.e., whether different methods require distinct recovery windows to exert optimal PAPE effects—has not been systematically investigated; and (3) few studies have quantified the influence of individual characteristics (e.g., baseline strength level) on PAPE responsiveness across different induction methods.

To address these gaps, this study aims to: (1) Systematically compare the acute effects of different PAPE induction methods across varying rest interval durations on the explosive jumping performance of healthy young adults, including CMJ height, standing long jump distance, and vertical jump peak power; (2) identify the optimal recovery time window for each induction method to maximize jumping performance improvements; and (3) explore the moderating role of baseline lower limb strength on PAPE responsiveness. The findings of this study are expected to provide evidence-based theoretical support and practical guidelines for athletes, coaches, and sports scientists to select individualized, efficient PAPE induction strategies, thereby advancing the scientificization of training and competition in jumping-related sports.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Search strategy

A systematic literature search was performed across four electronic databases: Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and EBSCO, following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Schmidt et al., 2019). The search period covered the inception of each database to 1 May 2025, yielding a total of 1909 initial records. The PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) framework was strictly applied to design the search strategy: Population = healthy individuals; Intervention = PAPE induction methods; Comparison = alternative intervention or no intervention; Outcome = jump performance indicators. English search terms were optimized for consistency and comprehensiveness as follows: (“PAPE” OR “Post-activation potentiation” OR “Post activation potentiation”) AND (“Jump performance” OR “Jump” OR “Vertical jump” OR “Jump height” OR “CMJ” OR “Countermovement jump” OR “Squat jump”) AND (“Randomized controlled trial” OR “RCT”).

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

2.2.1 Inclusion criteria

Study Design: Published studies investigating the effects of post-activation potentiation enhancement induction methods on jump performance indicators.

Participants: Healthy individuals aged ≤45 years (all were undergraduate students or athletes specializing in football, track and field, and other sports).

Intervention: The experimental group must receive PAPE-related exercises with clear documentation of exercise type, repetitions, sets, and intensity.

Control Group: The control group should either undergo alternative training methods or no training intervention.

Outcome Measures: Studies must report quantitative data on jump height (cm), including but not limited to counter movement jump (CMJ) height, squat jump height, and vertical jump height.

Accessibility: Full-text articles published in peer-reviewed journals.

2.2.2 Exclusion criteria

Study Design: Non-randomized controlled trials, observational studies, review articles, or case reports.

Unrelated Interventions: Studies that do not involve post-activation potentiation enhancement research or focus on non-jump performance indicators.

Ineligible Populations: Studies involving participants with chronic diseases or animal models.

Insufficient Outcomes: Research lacking quantitative data on jump performance.

Duplicate or Inaccessible Data: Duplicate publications, studies with incomplete data, or unavailable full texts.

2.3 Data extraction

All retrieved records were imported into EndNote software for de-duplication and management. Two independent researchers (J.W. and Y.Z.) screened the titles, abstracts, and full texts sequentially based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved through discussion, negotiation, or adjudication by a third researcher. The process of literature screening and inclusion is illustrated in Figure 1. Ultimately, a total of 22 articles were included in the analysis.

Two researchers extracted data from the eligible literature using a customized data extraction form, which primarily included the following information:

1. General information: First author and year of publication.

2. Sample characteristics: Study participants, gender, age, and sample size of the experimental group.

3. Experimental characteristics: Intervention protocols for the experimental group, including training methods, number of sets, frequency, and training intensity.

4. Outcome measure: Jump height.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using RevMan 5.4 software (Page et al., 2021). The standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were selected as the effect sizes for pooling combined effect magnitudes. The Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool was employed to evaluate the quality of the included studies (Higgins and Altman, 2007). Prior to conducting the comprehensive meta-analysis, a heterogeneity test was performed first. Homogeneity testing (Q-test, with a significance level of α = 0.1) was used for the heterogeneity assessment. The value of I2 ranges from 0% to 100%. When I2 > 50% and p < α, significant heterogeneity was considered to exist, and a random-effects model was selected for the meta-analysis. In contrast, a fixed-effects model was adopted. Subgroup analysis was conducted to address heterogeneity, and STATA 16.0 software was used for sensitivity analysis to examine the stability of the results. A funnel plot was utilized to verify the presence of publication bias.

3 Results

3.1 Study characteristics

A total of 22 publications were included in this study. All of these publications were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), involving 468 subjects of mixed genders, with ages ranging from 11 to 43 years. The basic characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1.

3.2 Study quality assessment

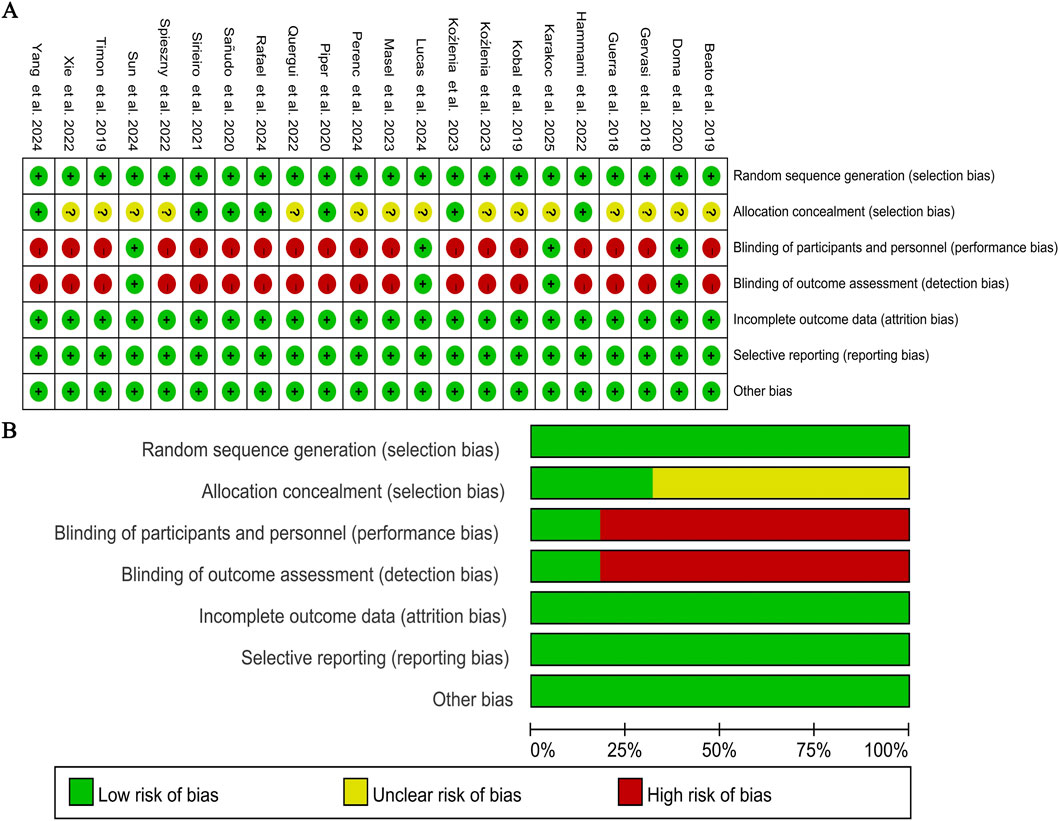

The methodological quality of the included RCTs was independently evaluated by two researchers (J.W. and Y.Z.) using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. Review Manager 5.4 software was used to assess seven key domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias (Figures 2A,B). Among the included studies, 15 failed to clearly state whether allocation staff strictly followed the random allocation process. Additionally, 18 had a high risk of bias in blinding, as participants signed informed consent forms before the experiment.

Figure 2. Methodological quality graph and summary of the included studies: (A) Risk of bias summary; (B) Risk of bias graph.

3.3 Jumping ability

A total of 22 studies reported the relationship between PAPE induction methods and jumping performance, involving 468 subjects in aggregate. Heterogeneity testing indicated I2 = 51% > 50%, and the Q-test yielded p = 0.003, suggesting substantial heterogeneity among the included studies. A random-effects model was therefore applied for meta-analysis (Figure 3). The results showed a combined effect size SMD = 1.36, which was statistically significant (Z = 5.70, P < 0.0001), indicating that appropriate PAPE induction protocols can improve subjects’ jumping performance compared with the control group.

3.4 Subgroup analysis

Based on the heterogeneity characteristics observed in this study, we speculate that the heterogeneity may originate from exercise mode, gender, outcome extracted, exercise intensity, and rest interval (Table 2).

In the exercise mode subgroup, the Back squat, Squat, and Running groups all showed homogeneity (I2 = 0%), while compared with the overall combined effect size (I2 = 51%), the Isometric back (I2 = 58%) and Jumping (I2 = 81%) subgroups exhibited higher heterogeneity, indicating substantial heterogeneity among studies within these two subgroups. Back squat yielded the largest effect size, which was statistically significant (SMD = 2.85, P = 0.003 < 0.01), suggesting that this activation method is more conducive to improving jumping performance.

In the gender subgroup, the heterogeneity values for the three groups were 56%, 52%, and 48%, respectively. Compared with the overall combined effect (I2 = 51%), both the male and female subgroups demonstrated higher heterogeneity. The male subgroup showed the largest effect size (SMD = 1.53, P < 0.0001), indicating that males may be more responsive to PAPE induction methods aimed at enhancing jumping performance.

In the outcome extracted subgroup, the heterogeneity values for the three groups were 53%, 42%, and 44%, respectively. Compared with the overall combined effect (I2 = 51%), the CMJ subgroup exhibited higher heterogeneity and also demonstrated the largest effect size (SMD = 1.34, P = 0.003 < 0.01), indicating that PAPE induction exercises can significantly improve subjects’ CMJ performance.

In the exercise intensity subgroup, the heterogeneity values for the low-, medium-, and high-intensity groups were 0%, 33%, and 39%, respectively, all of which were lower than the overall combined effect (I2 = 51%). This suggests that varying exercise intensities may be one of the sources of heterogeneity. The medium-intensity group yielded the largest effect size, which was statistically significant (SMD = 2.46, P < 0.0001), indicating that PAPE induced by medium-intensity exercise can significantly enhance subjects’ jumping performance.

In the rest interval subgroup, the heterogeneity values for the three groups were 42%, 68%, and 0%, respectively. Compared with the overall combined effect (I2 = 51%), the 3∼7 min subgroup showed higher heterogeneity and also produced the largest effect size (SMD = 1.34, P = 0.003 < 0.01), suggesting that a rest interval of 3∼7 min following PAPE induction can significantly improve subjects’ jumping performance.

3.5 Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was conducted using the leave-one-out method to evaluate the heterogeneity of the included studies.

As shown in Table 3, the pooled effect size of PAPE on jumping performance was [SMD = 1.36, 95% CI (0.89, 1.83), p < 0.0001]. After sequentially removing individual studies, the pooled SMD ranged from 1.08 to 1.61, and the heterogeneity index I2 varied between 29% and 53%. Specifically, after excluding the studies by Doma et al. (2020), Hammami et al. (2022), and Spieszny et al. (2022), the heterogeneity decreased to 47%, 29%, and 43%, respectively. All results remained statistically significant (p < 0.01). No single study threatened the overall meta-analysis results, indicating that the findings of this study are relatively stable.

3.6 Publication bias

This study constructed funnel plots for each subgroup to assess potential publication bias. As shown in Figure 4, the funnel plots exhibited an approximately symmetrical shape. Egger’s test was further conducted on these funnel plots, and the results showed that the p-values for all subgroups were greater than 0.05, indicating no significant publication bias among the included studies.

Figure 4. Funnel plots of jumping ability: (A) Combine funnel chart; (B) Exercise mode; (C) Gender; (D) Outcome extracted; (E) Exercise intensity; (F) Rest interval.

4 Discussion

4.1 The effect of PAPE on jumping ability

This study investigated the effects of different PAPE induction methods on jumping performance through a meta-analysis, incorporating a total of 22 studies involving 468 subjects. Random-effects model analysis revealed a pooled effect size of SMD = 1.36 (p < 0.0001), indicating that PAPE induction can significantly improve jumping performance. The enhancement of jumping ability primarily relies on neural adaptive changes, optimization of muscular mechanical properties, and improved energy utilization efficiency (Aeles et al., 2018). PAPE acts through multiple pathways on these mechanisms to further enhance explosive performance.

From the perspective of neuromuscular function, jumping performance is closely related to neural drive capacity, motor unit recruitment rate and synchronization, as well as muscle fiber contraction characteristics (Odetti et al., 2015). PAPE induction activates high-threshold motor neurons through high-intensity preconditioning stimuli, increasing spinal excitability and descending drive signals, thereby optimizing muscle activation efficiency (Hamada et al., 2000). Studies have shown that phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chains can enhance calcium ion (Ca2+) sensitivity within the sarcoplasm, accelerate cross-bridge cycling rate, and consequently improve the RFD—a key mechanical factor determining jump height (Daniel et al., 2023). Research also indicates that muscles under PAPE conditions can more effectively utilize elastic potential energy, enhancing stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) efficiency (Al et al., 2025), which is particularly critical for continuous and reactive jumping performance.

Furthermore, PAPE induction exhibits a selective activation effect on type II muscle fibers. Following high-intensity conditioning contractions, the recruitment threshold of fast-twitch fibers is temporarily lowered, making them more readily mobilized in subsequent explosive activities, thereby contributing to greater power and force output (Monteiro-Oliveira et al., 2022). Appropriate PAPE induction can optimize signal transduction at the neuromuscular junction, increasing the discharge frequency of motor units per unit time, which significantly improves jump height and take-off velocity (Pourmoghaddam et al., 2016).

The results of this study demonstrate a high degree of consistency, indicating that PAPE, as a training strategy, possesses strong generalizability and can be applied to different populations and various sports contexts. Future research should focus on clarifying the interactions between different induction protocols and individual characteristics (such as muscle fiber type, training experience, and genetic background), and further utilize techniques such as EMG and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to elucidate the central and peripheral mechanisms of PAPE.

4.2 Moderating factors of PAPE in enhancing jumping performance

The PAPE effect is regulated by multiple factors. For instance, although both loaded back squats and drop jumps can be used as PAPE induction methods, their neural adaptation patterns and fatigue-potentiation balance points differ, potentially leading to varying effects on different types of jumps such as CMJ, SJ, or Drop Jump (Ohta et al., 2013). Furthermore, the optimal rest interval duration is often influenced by an individual’s strength level and recovery capacity: untrained individuals may experience PAPE benefits masked by fatigue accumulation, whereas elite athletes can more effectively utilize shorter time windows to achieve neuromuscular enhancement (Boullosa et al., 2018).

This study identified substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 51%, p = 0.003), indicating that the PAPE effect is modulated by multiple factors. To further investigate this, subgroup analyses were conducted based on exercise mode, gender, outcome extracted, exercise intensity, and rest interval, thereby providing deeper insights into the influencing factors of the PAPE effect.

4.2.1 Exercise mode

From the perspective of induction methods, the effect sizes produced by different PAPE induction protocols exhibit distinct differences. Maximal voluntary contractions (MVC) and heavy resistance training (>85% 1RM) typically elicit stronger neural adaptations and myosin light chain phosphorylation, thereby demonstrating more prominent effects in enhancing vertical jump performance such as CMJ and SJ (Garbisu-Hualde and Santos-Concejero, 2021). In contrast, ballistic training (e.g., drop jumps, loaded jumps) offers unique advantages in improving stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) efficiency and reactive jump capacity due to its closer resemblance to sport-specific movement patterns (Wilk et al., 2020). This finding aligns with the “movement specificity principle” proposed by Wilk et al., which suggests that the transfer effect of PAPE is more significant when the induction exercise closely matches the biomechanical and neuromuscular control patterns of the target movement (Chambon et al., 2010).

4.2.2 Gender

The effect size for males (SMD = 1.41) was slightly higher than that for females (SMD = 1.19), though the between-group difference did not reach statistical significance. This trend may be related to muscle volume, hormonal environment, and muscle fiber type composition. Existing studies indicate that individuals with higher androgen levels typically possess a greater proportion of fast-twitch fibers and stronger neural drive capacity, which may contribute to more effective expression of power gains during PAPE induction (Daniel et al., 2023). Nevertheless, females can still achieve significant benefits through appropriately designed PAPE protocols, demonstrating that PAPE is an effective strategy applicable to both genders. However, potential influences such as hormonal fluctuations and strength levels should be considered when designing individualized programs.

4.2.3 Outcome extracted

Different jump test metrics exhibit varying sensitivity to PAPE. The highest pooled effect size was observed for CMJ (SMD = 1.48), while Drop Jump showed a relatively lower response (SMD = 1.21). CMJ performance is highly dependent on voluntary force production capacity and the RFD, making it more sensitive to enhancements in neural drive. In contrast, Drop Jump relies more on SSC efficiency and tendon stiffness, and its response may be influenced by the degree of specificity between the induction method and the sport-specific movement pattern (Ratamess et al., 2009).

CMJ jump height, as a valid metric for assessing the PAPE effect, is commonly quantified using the following formula (Cleary and Cook, 2020):

A value greater than 100 indicates the presence of PAPE. Among the studies incorporating CMJ jump height, all 22 studies reported positive effect sizes (SMD = 1.34). Thus, this study further validates the optimizing effect of PAPE induction on CMJ performance, supporting the view proposed.

4.2.4 Exercise intensity

Based on physiological and loading indicators such as percentage of maximum heart rate (%HRmax), blood lactate concentration (mmol/L) (Weigelin and Jessen, 1981), and percentage of one-repetition maximum (%1RM) (Karvonen and Vuorimaa, 1988), this study categorized exercise intensity into low-, medium-, and high-intensity subgroups (Table 4). Analysis revealed that the heterogeneity values for the low-, medium-, and high-intensity subgroups were 0%, 33%, and 39%, respectively, all lower than the overall heterogeneity (I2 = 51%), indicating that exercise intensity is a significant moderating factor contributing to the variability in results across studies. Notably, the medium-intensity subgroup demonstrated the largest effect size (SMD = 2.46, p < 0.0001), significantly outperforming both the low- and high-intensity subgroups. This suggests that PAPE induction implemented within this intensity range is most effective for enhancing jumping performance.

On one hand, this intensity (e.g., 80% 1RM) is sufficient to activate high-threshold type II muscle fibers, inducing adequate myosin light chain phosphorylation (Ayesta et al., 2006), which enhances calcium ion sensitivity and cross-bridge cycling rate, thereby providing the necessary neurophysiological foundation for explosive performance (Julian et al., 2021). On the other hand, compared to higher intensities (>85% 1RM), medium-load induction generates substantially less metabolic stress and central fatigue, allowing fatigue components to dissipate more rapidly. Consequently, the PAPE effect can be more fully expressed during the recovery period.

Although higher-intensity loads can theoretically induce stronger neural excitation and physiological stress, they simultaneously lead to more pronounced fatigue accumulation, often resulting in the “fatigue-masking effect” dominating and thereby reducing the net benefit of PAPE (Sabag et al., 2018). In contrast, low-intensity stimuli (<70% 1RM) are unable to effectively recruit fast-twitch muscle fibers or trigger sufficient molecular signaling responses, making it difficult to produce meaningful potentiation effects.

Therefore, in practice, it is recommended to use medium intensity (75%–85% 1RM) as the preferred range for PAPE induction. At the same time, individual adjustments should be made based on population characteristics and sport-specific demands, supplemented by real-time monitoring and personalized regulation using physiological indicators such as blood lactate and heart rate variability. This approach aims to maximize the enhancement effect of PAPE on jumping performance.

4.2.5 Rest interval

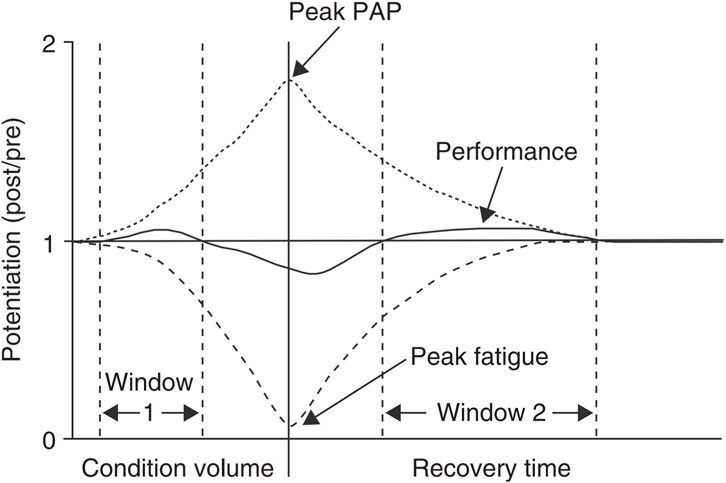

Rest interval is a critical temporal factor modulating PAPE benefits, directly influencing the balance between fatigue recovery and potentiation effects. This study indicates that 3–7 min represents the overall optimal recovery window (SMD = 1.47). Shorter intervals (<3 min) may allow fatigue to dominate, resulting in non-significant or even diminished performance improvements. Intervals exceeding 5 min lead to a gradual decline in neural excitability and calcium sensitivity, causing the PAPE effect to diminish. These findings are highly consistent with the previously proposed “fatigue enhancement two-phase theory” (Tillin and Bishop, 2009).

Under appropriate induction intensity, the PAPE effect may exhibit two distinct windows: the first occurs immediately to 2 min post-high-intensity loading, when neural excitability is elevated but fatigue has not fully dissipated (Figure 5). Subsequently, during the 3–7 min period, as the phosphagen system recovers and metabolic byproducts are cleared, fatigue decreases rapidly, allowing the PAPE effect to again dominate and form a more stable and pronounced second window of enhancement.

Figure 5. PAPE and fatigue model (Tillin and Bishop, 2009).

It is noteworthy that the optimal rest interval also varies with individual training status and induction load. Elite athletes, owing to faster phosphagen resynthesis and superior neural inhibitory control, may enter the PAPE-dominant phase within shorter intervals (e.g., 2–3 min) (Dobbs et al., 2018). In contrast, less-trained individuals or those using very high-intensity induction (e.g., >90% 1RM) often require longer intervals (4–6 min) to maximize the potentiation effect due to greater accumulation of fatigue metabolites (Daniel et al., 2023). Therefore, in practical training, rest intervals should be individualized based on both personal characteristics and induction intensity. Real-time monitoring of vertical jump performance or use of portable EMG devices to identify the optimal force production window can further enable precise exploitation of the PAPE effect.

4.3 Heterogeneity and methodological bias: key findings and implications

Moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 51%, p = 0.003) was observed for the effect of PAPE on jumping performance via random-effects modeling, partially explained by exercise intensity (0%–39% subgroup heterogeneity; moderate intensity: SMD = 2.46), movement mode (consistent with the specificity principle), rest interval (optimal 3–7 min), and outcome measures (CMJ more sensitive than SJ). Unaccounted variability may relate to unreported factors (e.g., training status, muscle fiber type) and inconsistent intervention protocols (e.g., repetition counts, movement standardization). Egger’s tests, and trim-and-fill analysis while sensitivity analysis validated result robustness. Heterogeneity highlights the necessity of personalized PAPE protocols, and rigorous bias mitigation (random-effects modeling, subgroup analyses) enhances conclusion credibility; future research should standardize induction protocols, incorporate additional moderators (e.g., age, training experience), to address remaining limitations.

4.4 Study limitations

In the quality assessment of the included studies, a considerable proportion exhibited a high risk of bias in the implementation of blinding, which often stems from practical and ethical constraints in human experiments. Additionally, the diversity among subjects in terms of training background, physical fitness level, and demographic characteristics, as well as variations in PAPE induction protocols—such as exercise modality, intensity, load volume, and rest intervals—contributed to significant heterogeneity in the results, thereby limiting the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, the lack of direct physiological indicators—such as EMG and blood lactate measurements—in the existing studies restricted an in-depth interpretation of the mechanisms underlying the PAPE effect. Future research should focus on standardizing intervention protocols, enhancing physiological monitoring, and implementing subgroup analyses based on subject characteristics, along with to assess cumulative adaptive effects beyond acute potentiation.

5 Conclusion

PAPE may serve as a potentially effective strategy for enhancing jumping performance under appropriate conditions. In exercises aimed at improving jumping performance, back squats and medium-intensity induction appear to yield the most pronounced benefits. A 3–7 min recovery interval works best, though adjustments should be made based on individual exercise factors.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Author contributions

YZ: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft. XZ: Formal Analysis, Project administration, Writing – review and editing. JW: Investigation, Software, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aeles J., Lichtwark G. A., Peeters D., Delecluse C., Jonkers I., Vanwanseele B. (2018). Effect of a prehop on the muscle-tendon interaction during vertical jumps. Am. Physiological Soc. 124 (5), 1203–1211. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00462.2017

Al K. M., Ambussaidi A., Al Busafi M., Al-Hadabi B., Haj S. R., Bouhlel E., et al. (2025). Acute effect of post activation potentiation enhancement using drop jumps on repeated sprints combined with vertical jumps in young handball players. Sage Publ. 29 (2), 147–154. doi:10.3233/IES-203185

Ayestarán E. G., González Badillo J. J., Izquierdo M. (2006). Moderate volume of high relative training intensity produces greater strength gains compared with low and high volumes in competitive weightlifters. J. Strength and Cond. Res. 20 (1), 73–81. doi:10.1519/R-16284.1

Batista A. B., Roschel H., Barroso R., Ugrinowitsch C., Tricoli V. (2011). Influence of strength training background on postactivation potentiation enhancement response. J. Strength Cond. Res. 25 (9), 2496–2502. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e318200181b

Bazanov B., Pedak K., Rannama I. (2019). Relationship between musculoskeletal state and vertical jump ability of young basketball players. Universidad de Alicante. Área Educ. Física Deporte 14 (4), S724–S731. doi:10.14198/JHSE.2019.14.PROC4.33

Beato M., Bigby A. E. J., De Keijzer K. L., Nakamura F. Y., Coratella G., McErlain-Naylor S. A. (2019). Post-activation potentiation enhancement effect of eccentric overload and traditional weightlifting exercise on jumping and sprinting performance in male athletes. PLoS One 14 (9), e0222466. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0222466

Beattie K., Kenny I. C., Lyons M., Carson B. P. (2014). The effect of strength training on performance in endurance athletes. Sports Med. 44 (6), 845–865. doi:10.1007/s40279-014-0157-y

Boullosa D., Rosso S. D., Behm D. G., Foster C. (2018). Post-activation potentiation enhancement (pape) in endurance sports: a review. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 18 (5), 595–610. doi:10.1080/17461391.2018.1438519

Chambon C., Duteil D., Vignaud A., Ferry A., Messaddeq N., Malivindi R., et al. (2010). Myocytic androgen receptor controls the strength but not the mass of limb muscles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107 (32), 14327–14332. doi:10.1073/pnas.1009536107

Chaves L. G., Anita Mendes Sá S., Nobre Pinheiro B., Godinho I., Casanova F., Reis V. M., et al. (2024). Comparison between warm-up protocols in post-activation potentiation enhancement enhancement (papee) of sprint and vertical jump performance in a female futsal team. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 96 (3), 455–462. doi:10.1080/02701367.2024.2434142

Chen Y., Su Q., Yang J., Li G., Zhang S., Lv Y., et al. (2023). Effects of rest interval and training intensity on jumping performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis investigating post-activation performance enhancement. Front. Physiol. 14, 1202789. doi:10.3389/fphys.2023.1202789

Cleary C. J., Cook S. B. (2020). Postactivation potentiation enhancement in blood flow-restricted complex training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 34 (4), 905–910. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003497

Cui W., Chen Y., Wang D. (2024). Research on the effect of post-activation potentiation enhancement under different velocity loss thresholds on boxer’s punching ability. Front. Physiol. 15, 1429550. doi:10.3389/fphys.2024.1429550

Daniel D., Jernej P., Bas V. H., Kozinc Ž., Šarabon N. (2023). The relationship between elastography-based muscle properties and vertical jump performance, countermovement utilization ratio, and rate of force development. Eur. J. Appl. Physiology 123 (8), 1789–1800. doi:10.1007/s00421-023-05191-7

Dobbs W. C., Tolusso D. V., Fedewa M. V., Esco M. R. (2018). Effect of postactivation potentiation enhancement on explosive vertical jump: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Strength Cond. Res. 33 (7), 2009–2018. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002750

Doma K., Leicht A. S., Boullosa D., Woods C. T. (2020). Lunge exercises with blood-flow restriction induces post-activation potentiation enhancement and improves vertical jump performance. Eur. J. Appl. Physiology 120 (3), 687–695. doi:10.1007/s00421-020-04308-6

Dos S. D., Boullosa D., Moura P. V., Jesus M. D., Sousa F. M. S., Badicu G., et al. (2023). Post-activation performance enhancement effect of drop jump on long jump performance during competition. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 16993. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-44075-w

Ewertowska P., Świtała K., Grzyb W., Urbański R., Aschenbrenner P., Krzysztofik M. (2023). Effects of whole-body vibration warm-up on subsequent jumping and running performance. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 7411. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-34707-6

Garbisu-Hualde A., Santos-Concejero J. (2021). Post-activation potentiation enhancement in strength training: a systematic review of the scientific literature. J. Hum. Kinet. 78 (1), 141–150. doi:10.2478/hukin-2021-0034

Gervasi M., Calavalle A. R., Amatori S., Grassi E., Benelli P., Sestili P., et al. (2018). Post-activation potentiation enhancement increases recruitment of fast twitch fibers: a potential practical application in runners. J. Hum. Kinet. 65 (1), 69–78. doi:10.2478/hukin-2018-0021

Guerra M. A., Jr., Caldas L. C., De Souza H. L., Vitzel K. F., Cholewa J. M., Duncan M. J., et al. (2018). The acute effects of plyometric and sled towing stimuli with and without caffeine ingestion on vertical jump performance in professional soccer players. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 15 (1), 51. doi:10.1186/s12970-018-0258-3

Hamada T., Sale D. G., Macdougall J. D. (2000). Postactivation potentiation enhancement in endurance-trained male athletes. Med. and Sci. Sports and Exerc. 32 (2), 403–411. doi:10.1097/00005768-200002000-00022

Hammami R., Ben Ayed K., Abidi M., Werfelli H., Ajailia A., Selmi W., et al. (2022). Acute effects of maximal versus submaximal hurdle jump exercises on measures of balance, reactive strength, vertical jump performance and leg stiffness in youth volleyball players. Front. Physiology 13, 1–984947. doi:10.3389/fphys.2022.984947

Higgins J., Altman D. (2007). Quality evaluation of included studies: new suggestions for data extraction forms. Chin. J. Evidence-Based Med. (1), 61. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1672-2531.2007.01.010

Ishii T., Sasada S., Komiyama T. (2023). Post-contraction potentiation can react inversely to post-activation potentiation enhancement depending on the test contraction force. Neurosci. Lett. 801 (000), 6. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2023.137132

Julian V., Costa D., Omalley G., Metz L., Fillon A., Miguet M., et al. (2021). Bone response to high-intensity interval training versus moderate-intensity continuous training in adolescents with obesity. Obes. Facts 15 (1), 46–54. doi:10.1159/000519271

Karakoç B., Eken Ö., Kurtoğlu A., Arslan O., Eken İ., Elkholi S. M. (2025). Time-of-day effects on post-activation potentiation enhancement protocols: effects of different tension loads on agility and vertical jump performance in judokas. Med. Kaunas. 61 (3), 426. doi:10.3390/medicina61030426

Karvonen J., Vuorimaa T. (1988). Heart rate and exercise intensity during sports activities. Sports Med. 5 (5), 303–311. doi:10.2165/00007256-198805050-00002

Kobal R., Pereira L. A., Kitamura K., Paulo A. C., Ramos H. A., Carmo E. C., et al. (2019). Post-activation potentiation enhancement: is there an optimal training volume and intensity to induce improvements in vertical jump ability in highly-trained subjects? J. Hum. Kinet. 69, 239–247. doi:10.2478/hukin-2019-0016

Koźlenia D., Domaradzki J. (2023a). The sex effects on changes in jump performance following an isometric back squat conditioning activity in trained adults. Front. Physiology 14, 1–1156636. doi:10.3389/fphys.2023.1156636

Koźlenia D., Domaradzki J. (2023b). The effectiveness of isometric protocols using an external load or voluntary effort on jump height enhancement in trained females. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 13535. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-40912-0

Li J., Soh K. G., Loh S. P. (2024). The impact of post-activation potentiation on explosive vertical jump after intermittent time: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 17213. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-67995-7

Liu H., Jiang L., Wang J. (2024). The effects of blood flow restriction training on post activation potentiation enhancement and upper limb muscle activation: a meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 15, 1395283. doi:10.3389/fphys.2024.1395283

Masagca R. C. (2024). Jump squat as ergogenic aid through post-activation potentiation enhancement on horizontal and vertical jumping performance of untrained collegiate students. Sportis. Sci. J. Sch. Sport, Phys. Educ. Psychomotricity 11 (1), 1–34. doi:10.17979/sportis.2025.11.1.11148

Masel S., Maciejczyk M. (2023). Post-activation effects of accommodating resistance and different rest intervals on vertical jump performance in strength trained males. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabilitation 15 (1), 65. doi:10.1186/s13102-023-00670-y

Mckiel A., Woods S. R., Faragher M., Taylor G., Vandenboom R., Falk B. (2024). Optimization of post-activation potentiation enhancement in girls and women. Eur. J. Appl. Physiology 24 (9), 124. doi:10.1007/s00421-024-05475-6

Monteiro-Oliveira B. B., Coelho-Oliveira A. C., Paineiras-Domingos L. L., Sonza A., Sá-Caputo D. d.C. d., Bernardo-Filho M. (2022). Use of surface electromyography to evaluate effects of whole-body vibration exercises on neuromuscular activation and muscle strength in the elderly: a systematic review. J. Disabil. Rehabilitation 44 (24), 7368–7377. doi:10.1080/09638288.2021.1994030

Moré C. R., Moré R. A. S., Boullosa D., Dellagrana R. A. (2023). Influence of intensity on post-running jump potentiation in recreational runners vs. physically active individuals. J. Hum. Kinet. 90, 137–150. doi:10.5114/jhk/172268

Odetti P., Monacelli F., Storace D., Melero-Romero C., Rodríguez-Rosell D., Fernandez-Garcia J. (2015). The effects of aquatic plyometric training on repeated jumps, drop jumps and muscle damage. Int. J. Sports Med. 39 (10), 764–772. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1398574

Ohta Y., Takahashi K., Matsubayashi T. (2013). Possibility of intrinsic muscle contractile properties in force summation and postactivation potentiation enhancement as indices of maximal muscle strength and muscle fatigue. Muscle and Nerve 47 (6), 894–902. doi:10.1002/mus.23674

Ouergui I., Delleli S., Messaoudi H., Chtourou H., Bouassida A., Bouhlel E., et al. (2022). Acute effects of different activity types and work-to-rest ratio on post-activation performance enhancement in young male and female taekwondo athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 (3), 1764. doi:10.3390/ijerph19031764

Page M. J., McKenzie J. E., Bossuyt P. M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T. C., Mulrow C. D., et al. (2021). The prisma 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. Engl. Ed. 74 (9), 790–799. doi:10.1016/j.rec.2021.07.010

Perenc D., Stastny P., Urbański R., Krzysztofik M. (2025). Acute effects of supramaximal loaded back squat activation on countermovement jump performance, muscle mechanical properties, and skin surface temperature in powerlifters. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 25 (1), e12245. doi:10.1002/ejsc.12245

Piper A. D., Joubert D. P., Jones E. J., Whitehead M. T. (2020). Comparison of post-activation potentiating stimuli on jump and sprint performance. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 13 (4), 539–553. doi:10.70252/RPEZ7761

Pourmoghaddam A., Dettmer M., O’Connor D. P., Paloski W. H., Layne C. S. (2016). Measuring multiple neuromuscular activation using emg - a generalizability analysis. J. Biomed. Technol. 61 (6), 595–605. doi:10.1515/bmt-2015-0037

Ratamess N., Alvar B. A., Evetoch T. K., Housh T. J., Kibler W. B., Kraemer W. J. (2009). Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults [acsm position stand]. Med. and Sci. Sports and Exerc. 41, 687–708. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181915670

Sabag A., Najafi A., Michael S., Esgin T., Halaki M., Hackett D. (2018). The compatibility of concurrent high intensity interval training and resistance training for muscular strength and hypertrophy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sports Sci. 36 (21), 2472–2483. doi:10.1080/02640414.2018.1464636

Sañudo B., de Hoyo M., Haff G. G., Muñoz-López A. (2020). Influence of strength level on the acute post-activation performance enhancement following flywheel and free weight resistance training. Sensors (Basel) 20 (24), 7156. doi:10.3390/s20247156

Schmidt L., Shokraneh F., Steinhausen K., Adams C. E. (2019). Introducing raptor: revman parsing tool for reviewers. Syst. Rev. 8 (1), 151. doi:10.1186/s13643-019-1070-0

Sirieiro P., Nasser I., Dobbs W. C., Willardson J. M., Miranda H. (2021). The effect of set configuration and load on post-activation potentiation enhancement on vertical jump in athletes. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 14 (4), 902–911. doi:10.70252/CCLW6758

Spieszny M., Trybulski R., Biel P., Zając A., Krzysztofik M. (2022). Post-isometric back squat performance enhancement of squat and countermovement jump. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 (19), 12720. doi:10.3390/ijerph191912720

Sun S., Yu Y., Niu Y., Ren M., Wang J., Zhang M. (2024). Post-activation performance enhancement of flywheel and traditional squats on vertical jump under individualized recovery time. Front. Physiology 15, 1–1443899. doi:10.3389/fphys.2024.1443899

Terbalyan A., Skotniczny K., Krzysztofik M., Chycki J., Kasparov V., Roczniok R. (2025). Effect of post-activation performance enhancement in combat sports: a systematic review and meta-analysis-part i: general performance indicators. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol 10 (1), 88. doi:10.3390/jfmk10010088

Tillin N. A., Bishop D. (2009). Factors modulating post-activation potentiation enhancement and its effect on performance of subsequent explosive activities. Sports Med. 39 (2), 147–166. doi:10.2165/00007256-200939020-00004

Timon R., Allemano S., Camacho-Cardeñosa M., Camacho-Cardeñosa A., Martinez-Guardado I., Olcina G. (2019). Post-activation potentiation enhancement on squat jump following two different protocols: traditional vs. inertial flywheel. J. Hum. Kinet. 69, 271–281. doi:10.2478/hukin-2019-0017

Wang I. L., Chen Y. M., Zhang K. K., Li Y. G., Su Y., Wu C., et al. (2021). Influences of different drop height training on lower extremity kinematics and stiffness during repetitive drop jump. Appl. Bionics Biomechanics 2021 (2), 1–9. doi:10.1155/2021/5551199

Wang J., Liu H., Jiang L. (2023). The effects of blood flow restriction training on pape and lower limb muscle activation: a meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 14, 1243302. doi:10.3389/fphys.2023.1243302

Weigelin E., Jessen K. (1981). Onset of blood lactate accumulation and marathon running performance. Int. J. Sports Med. 2 (1), 23–26. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1034579

Wilk M., Krzysztofik M., Filip A., Szkudlarek A., Lockie R. G., Zajac A. (2020). Does post-activation performance enhancement occur during the bench press exercise under blood flow restriction? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 (11), 3752. doi:10.3390/ijerph17113752

Xie H., Zhang W., Chen X., He J., Lu J., Gao Y., et al. (2022). Flywheel eccentric overload exercises versus barbell half squats for basketball players: which is better for induction of post-activation performance enhancement? PLoS One 17 (11), e0277432. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0277432

Yang C., Shi L., Lu Y., Wu H., Yu D. (2024). Post-activation performance enhancement of countermovement jump after drop jump versus squat jump exercises in elite rhythmic gymnasts. J. Sports Sci. Med. 23 (1), 611–618. doi:10.52082/jssm.2024.611

Yu W., Feng D., Zhong Y., Luo X., Xu Q., Yu J. (2024). Examining the influence of warm-up static and dynamic stretching, as well as post-activation potentiation effects, on the acute enhancement of gymnastic performance: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Sports Sci. Med. 23 (1), 156–176. doi:10.52082/jssm.2024.156

Keywords: back squat, jumping ability, meta-analysis, post-activation potentiation enhancement, rest interval

Citation: Zhou Y, Zhang X and Wang J (2026) Post-activation potentiation enhancement induction strategies with different rest intervals on jump performance: a meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 16:1696129. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2025.1696129

Received: 31 August 2025; Accepted: 23 December 2025;

Published: 15 January 2026.

Edited by:

Chansol Hurr, Jeonbuk National University, Republic of KoreaReviewed by:

Mário Cunha Espada, Instituto Politecnico de Setubal (IPS), PortugalEzgi Ayaz, Nisantasi University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2026 Zhou, Zhang and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ying Zhou, eWluZ3pob3UwNjY2QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Ying Zhou1,2*

Ying Zhou1,2* Jian Wang

Jian Wang