- 1The Second Clinical Medical College, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China

- 2Dongguan Institute of Hepatobiliary Diseases, Dongguan Nancheng Hospital, Dongguan, China

- 3The First School of Clinical Medicine, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China

- 4Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Digital Medicine and Biomechanics and Guangdong Engineering Research Center for Translation of Medical 3D Printing Application and National Virtual and Reality Experimental Education Center for Medical Morphology (Southern Medical University) and National Key Discipline of Human Anatomy, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China

- 5School of Health Management, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China

- 6School of Basic Medical Sciences, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China

- 7Department of Ultrasound Medicine, Xiangyang Central Hospital, Hubei University of Arts and Science, Xiangyang, China

With the advancement of minimally invasive techniques and the reevaluation of surgical indications, gallbladder-preserving cholecystolithotomy is anticipated to serve as an alternative to cholecystectomy in specific cases. The choice of surgical incision is critical for optimizing gallbladder function preservation, which is a pivotal factor influencing the prognosis of gallbladder-preserving cholecystolithotomy. Consequently, a comprehensive understanding of the distribution of microstructures, including gallbladder blood vessels and nerves, is of substantial significance. For this study, we selected the gallbladders of healthy four-year-old children as our subjects. Gallbladder specimens were dehydrated, paraffin-embedded, and serially sectioned into hundreds of 4-μm-thick slices. Sections were selectively stained with distinct protocols—hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and anti-tyrosine hydroxylase immunohistochemical staining—followed by sequential numbering. Digitized sections were reconstructed into three-dimensional models (3D) using computational software. The resultant 3D gallbladder models achieved a resolution threshold of <20 μm, enabling visualization of microvascular and neural structures. Independent and integrated analyses of the modeled cystic arteries, veins, and sympathetic neural networks revealed two superficial arterial trunks and one deep branch originating from the superficial division of the cystic artery, with their interactive patterns defining nutrient-supplying territories. Further mapping of microvascular and neural trajectories within the digital models identified a minimally function-disruptive surgical incision site, diverging from conventional fundal incision approaches for gallstone extraction. This approach offers a 3D visualization framework to enhance pathological slice interpretation—thereby facilitating histopathological diagnosis—and is proposed as a novel surgical route for gallbladder-preserving cholelithotomy.

1 Introduction

Gallstones are among the most prevalent gastrointestinal diseases worldwide (Portincasa et al., 2006), and cholecystectomy is regarded as the standard surgical treatment for this condition (Qu et al., 2020). A critical step in the procedure is the identification and ligation of the cystic artery within Calot’s triangle (Abdalla et al., 2013). However, as our understanding of gallbladder function deepens and the incidence of gallbladder diseases in younger populations rises, cholecystectomy may not universally apply as a solution (Sicklick et al., 2005). In specific cases, gallbladder-preserving cholelithotomy may provide a more favorable prognosis (Tang et al., 2024).

Consequently, we are dedicated to investigating the optimal approach for gallbladder-preserving cholelithotomy, focusing on avoiding significant blood vessels and nerves to minimize damage to the gallbladder and enhance the preservation of its function. Specifically, preservation of the intact vascular supply prevents intraoperative hemorrhage and ischemic necrosis (Pes et al., 2023), while sparing the autonomic neural network maintains gallbladder contractility, thereby reducing the risk of biliary stasis and subsequent stone recurrence (Housset et al., 2016; Venneman and van Erpecum, 2010). To achieve this goal, it is essential to construct a three-dimensional physiological model of the gallbladder and to develop a comprehensive understanding of the cystic artery’s course, the internal structure of the gallbladder, and the distribution and vascular density of its branches (Krishnamurthy et al., 1981; Schiewe et al., 2025).

Current technologies for constructing 3D gallbladder models primarily encompass radiological imaging (ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)) (Morgan et al., 2018; Martins et al., 2025), tissue optical clearing, and digitized section-based 3D reconstruction—each with distinct functional applications (Martins et al., 2025; Ye et al., 2023). Advantages of radiological models include rapid spatial distribution mapping, which is particularly effective for detecting anatomical variations; low cost; and intraoperative augmented reality (AR) navigation capability for optimal surgical pathway selection (Zhao et al., 2022). However, limitations include insufficient resolution for visualizing microvascular trajectories. Although computed tomographic angiography (CTA) partially displays vasculature (Yang et al., 2014), contrast agent constraints restrict visualization to main trunks and partial branches (Rojo Ríos et al., 2023). Tissue optical clearing also faces inherent limitations such as antibody permeability dependency, prolonged processing (1–2 months/sample) (Kiemen et al., 2023), and unstable imaging outcomes. Cost escalates significantly with increased sample volume, hindering human organ studies.

In contrast, three-dimensional reconstruction technology based on digital slices is not constrained by tissue characteristics. This versatility has been demonstrated in previous studies visualizing the spatial heterogeneity of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (Kiemen et al., 2022), the intricate bile canaliculi and sinusoidal networks in the liver (Segovia-Miranda et al., 2019), and the microvascular architecture of the brain (Gijtenbeek et al., 2005). Beyond enabling precise spatial localization of microstructures, this technology also permits flexible adjustment of slice thickness according to research requirements, thereby optimizing the resolution of gallbladder microstructures. In this study, we aimed to reconcile high-precision vascular visualization with cost-efficiency by adopting digitized sectioning integrated with high-resolution scanning, which resulted in a gallbladder model with a resolution of 4 μm (Figure 1). Utilizing this model, we quantitatively analyzed the neurovascular distribution to propose optimal surgical incisions that minimize damage to the gallbladder’s critical blood vessels and nerves.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Gallbladder tissue section preparation

Gallbladder specimens were procured from a 4-year-old female victim of accidental death with no documented pathology. Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 48 h, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, treated with 1:1 anhydrous ethanol-xylene mixture for 15 min, cleared in xylene I (15 min) and xylene II (15 min) to achieve transparency, and infiltrated with xylene-paraffin mixture (1:1) for 15 min. Complete infiltration was ensured by immersion in paraffin I (65 °C, 1 h), paraffin II (65 °C, 21 h), and paraffin III (65 °C, 1 h). After cooling, serial sections were cut at 4-μm thickness.

To achieve simultaneous visualization of distinct anatomical systems within the same spatial coordinate system while maintaining cost-efficiency, a strategic grouping approach was employed. A total of 224 serial sections were divided into two interleaved sets—Set 1: odd-numbered sections (1, 3, 5,...) and Set 2: even-numbered sections (2, 4, 6,...). This alternating arrangement leveraged the spatial continuity of adjacent slices to minimize alignment errors during 3D reconstruction. Set 1 was subjected to conventional H&E staining to delineate vascular morphology, while Set 2 underwent immunohistochemistry (IHC) using anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) antibody (ab137869, Abcam, 1:200) to specifically target sympathetic nerves. All stained sections were mounted with neutral gum.

2.2 Digitalization of gallbladder sections

To achieve spatial correspondence across the serial sections, automated image registration was performed using the SimpleITK library in Python (Figure 2). An intensity-based rigid registration algorithm was employed, utilizing Mean Squares as the similarity metric and a Regular Step Gradient Descent optimizer. The transformation was constrained to 2D translation (rigid transformation) to correct positional offsets (tx, ty) while strictly preserving the original rotation and scale of the tissue structures. The central section (#112) served as the initial reference, and registration propagated bidirectionally through the stack. Registration quality was automatically monitored using the correlation coefficient, ensuring robust alignment without the observer variability associated with manual landmark placement.

Figure 2. (A) Schematic illustration of the image registration workflow. (B) Comparison of pre- and post-registration alignment. The post-registration images demonstrate significantly improved structural continuity and spatial consistency.

2.3 Construction of digital gallbladder models

Following the previously described protocols, pediatric gallbladder specimens were subjected to sequential fixation, embedding, sectioning, H&E/TH-IHC staining, and digitization. Subsequently, 3D segmentation and reconstruction were performed using Mimics 21 (Materialise, Belgium).

Digitized images were imported into Mimics and spatially calibrated (Software readout 60.05 mm = Physical truth 1600 μm; pixel size: 0.0266 mm) to ensure dimensional accuracy. Given the complex morphology and varying contrast of the microvasculature, a manual segmentation protocol was employed to ensure topological precision. To maintain consistency, the segmentation environment was standardized: image contrast was enhanced using a fixed window/level setting, and segmentation was executed slice-by-slice using a pixel-perfect brush tool (1–3 pixels diameter) under high magnification.

Upon completion of segmentation, 3D models were generated. To minimize global construction variability and observer bias inherent in manual protocols, a “segmented calculation and summation” strategy was applied. Furthermore, the reproducibility of this manual construction was rigorously validated. As detailed in Table 1, repeated morphometric measurements (n = 3) of the inner and outer diameters at standardized landmarks demonstrated minimal variability (Standard Deviation <10% of the mean diameter), confirming the robustness of the manual delineation process.

2.4 Sample processing for transmission electron microscopy

Gallbladder samples underwent primary fixation in 2.5% glutaraldehyde/0.1M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0, ≥4 h) followed by three 15-min buffer rinses. For secondary fixation, 1% OsO4 in identical buffer (1–2 h) was used, with subsequent rinses. Dehydration progressed through graded ethanol (30%, 50%, 70%, 80%; 15 min/step) and acetone (90%, 95%; 15 min/step) series, culminating in two 20-min absolute acetone incubations. Resin infiltration was initiated in 1:1 acetone/Spurr resin (1 h, RT), transitioned to a 1:3 mixture (3 h), followed by pure resin (overnight). Samples were polymerized in molds (70 °C, ≥9 h), sectioned at 70–90 nm (Leica EM UC7), dual-stained with uranyl acetate (10 min) and lead citrate (5–10 min), and imaged on a Hitachi H-7800 transmission electron microscope (TEM) (80–100 kV).

2.5 Specimen casting

Arterial perfusion was initiated with 25 mL of low-viscosity red acrylic resin (Zidan et al., 2020) injected through the celiac trunk. Upon resin outflow from the superior mesenteric artery, the inferior mesenteric arterial cannula was clamped. Perfusion continued until filling of transverse colic/gastroepiploic/cystic arteries and hepatic speckling, followed by 30-min stabilization. High-viscosity resin was supplemented into celiac and superior mesenteric arteries (20 mL each). Specimens were polymerized at 40 °C for 24 h. For biliary perfusion, 25 mL green resin was utilized via the cystic duct until gallbladder/hepatic duct distension. Specimens in anatomical position underwent corrosion in 37% HCl (3–4 days), followed by high-pressure water rinsing, 1% ammonia neutralization (24 h), 5%–10% H2O2 bleaching (24 h), and thorough washing with water.

2.6 Comparative analysis of vasculature density in left-right gallbladder regions

A reference line bisecting each segmented section along the longitudinal axis was delineated. Images were batch-imported into Adobe Photoshop CC 2019 (Adobe Inc., USA). Using the Slice Tool, sections were divided along reference lines into left/right halves via: Slice Tool → Right-click → Divide Slice → Vertically, Number of Slices: 2. Slices were then exported as individual TIFF files. Files were batch-processed in ImageJ v1.53 (NIH), and vasculature density was quantified. Given that the left and right regions were derived from the same tissue section, statistical significance was assessed using a Paired t-test (α = 0.05) to account for the matched nature of the samples. Data visualization was performed using GraphPad Prism v10.1.2 (GraphPad Software, USA).

2.7 Quantification of gallbladder vascular diameters

Quantification of gallbladder vascular diameters was performed in accordance with (Łabętowicz et al., 2025; Thiyagarajah et al., 2025). Vascular locations were identified on 2D sections by cross-referencing the reconstructed 3D gallbladder model. Five measurement points were systematically selected per vessel. Lumen and external diameters were measured at designated points using Mimics’ integrated measurement tools, with triplicate measurements per point averaged. For cross-sections, lumen area was measured for radius calculation via Equation 1. Longitudinal sections permitted direct measurement of the diameter. Scaled dimensions were derived using embedded scale bars. Data visualization was performed in GraphPad Prism v10.1.2 (GraphPad Software, USA).

3 Results

3.1 Trajectories of principal gallbladder vasculature

Through H&E staining and tyrosine hydroxylase immunohistochemistry (TH-IHC) for sympathetic nerve specificity, arteries, veins, and sympathetic nerves were annotated using Mimics software. H&E staining distinguished arteries by their circular luminal profiles, contrasting with the collapsed or irregularly elliptical venous structures consistently observed in adjacent vascular pairs (Figure 3a). Three-dimensional reconstructions delineated the vascular and neural distributions (Figure 3b), revealing superficial cystic artery branches bifurcating into α- and β-arteries traversing the gallbladder sides. The α-artery demonstrated extensive branching and anastomosed with the deep γ-branch, establishing nutrient-supplying collaterals. A single dominant δ-vein paralleled the α-artery toward the fundus. Sympathetic nerves exhibited a diffuse distribution without fasciculated bundles and were predominantly localized in the neck and body regions.

Figure 3. (a) H&E staining and immunohistochemistry (IHC) identification of arteries, veins, and nerves in gallbladder sections. (b) Spatial distribution of vasculature and neural networks in the digital gallbladder model. (c) Quantification of the diameter of pericholecystic main vascular trunks.

Quantitative morphometric analysis at five standardized points along the longitudinal axis revealed distinct dimensional hierarchies (Table 1). The α-artery served as the dominant arterial trunk, tapering from a proximal outer diameter of 325.2 ± 14.3 μm to a distal 143.3 ± 5.1 μm. The β-artery was comparatively smaller, with a proximal outer diameter of 280.1 ± 8.5 μm. The deep γ-branch represented the finest vascular structure identified, exhibiting a minimum outer diameter of 110.0 ± 37.1 μm (Point 4) and an inner diameter as narrow as 46.2 ± 7.0 μm at the distal tip (Point 5). The δ-vein showed a caliber comparable to the α-artery, with a proximal outer diameter of 333.1 ± 14.4 μm (Figure 3c).

3.2 Visualization of microscopic gallbladder structures

Dye perfusion of gallbladder specimens revealed numerous micro vessels distributed peripherally, with densely aligned arteriovenous pairs and extensive intervascular anastomoses (Figure 4a). Conventional gallbladder-preserving cholelithotomy via fundal incision risks inadvertent transection of microvasculature and functional nerves (Tan et al., 2013). Limitations of traditional dye perfusion include restricted penetration due to high viscosity, which impairs visualization of sub-20-μm vessels, and lack of quantitative digital analysis. Three-dimensional reconstructions using Mimics software delineated microvascular and sympathetic neural networks (Figure 4b), with fusion of topologically correlated models enhancing spatial relationship comprehension. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) at ×2,000 magnification further enabled visualization of murine gallbladder microvasculature (Figure 4c), achieving superior vascular discrimination comparable to H&E staining at the histological level. To precisely delineate the spatial topology of the neurovascular network, the reconstructed 3D digital model was processed to generate a vascular skeleton map (Figure 4d). This skeletonization filtered out volumetric noise, clearly highlighting the main arterial trajectories, particularly the course of the β-artery along the medial aspect. Based on this topology, a specific ‘safety window’ was identified on the medial aspect of the gallbladder body (facing the stomach). To strictly preserve the blood supply, the optimal surgical incision was strategically designated just distal (superior) to the trajectory of the β-artery. By placing the incision in this specific medial avascular zone, the procedure effectively avoids the β-artery while ensuring safe access near the hepatic margin.

Figure 4. (a) Macroscopic view of the arteriovenous-perfused gallbladder specimen. (b) Three-dimensional reconstruction of micro-arteries, micro-veins, and sympathetic nerves. (c) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of intramural microvasculature. (d) Vascular skeleton map highlighting the major vascular trunks and the proposed optimal surgical incision within the medial avascular safety zone.

3.3 Optimal surgical approach assessment for calculous gallbladders

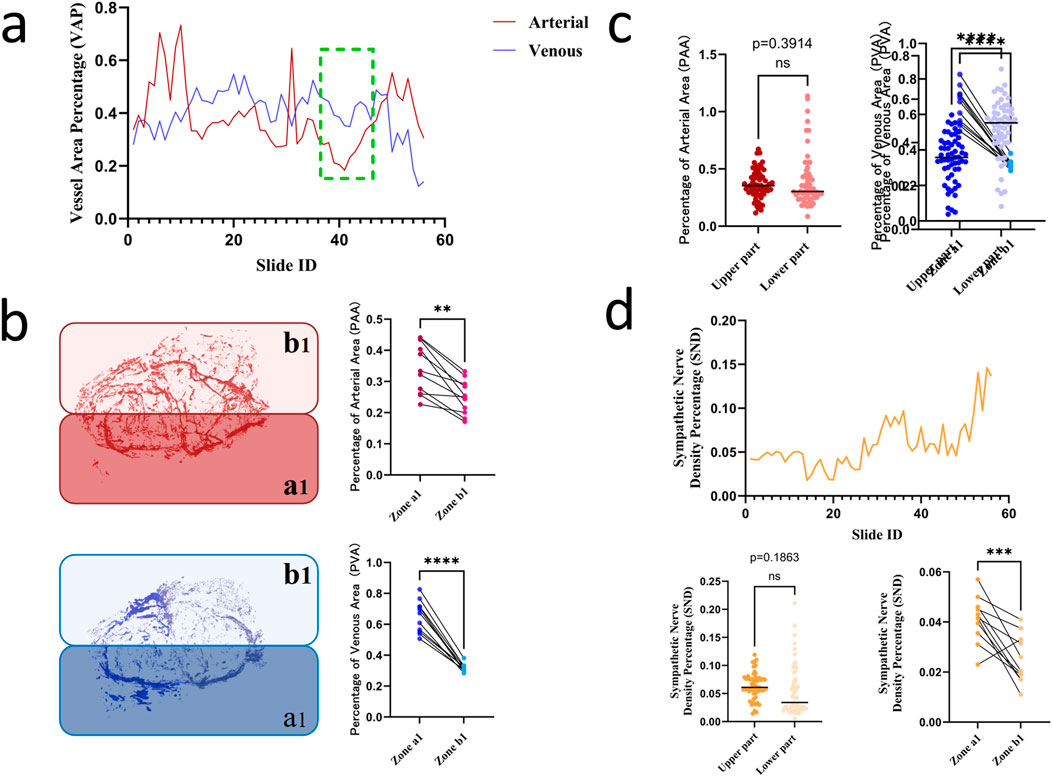

Following arterial/venous annotation in Mimics, the venous density per section was quantified (Table 2). The results revealed that sections 36–46 exhibited minimal vascular density (Figure 5a), with the arterial area fraction nadir at 0.1835%, indicating reduced hemorrhagic risk for incisions in this zone. This section range was subdivided into the following hemigallbladder regions: α-artery territory as a1 and β-artery territory as b1. Regional density analysis demonstrated significantly higher vascularity in a1 than in b1 (P < 0.005; Figure 5b). Vertical partitioning showed comparable arterial density (P = 0.3914), but significantly lower venous density in superior versus inferior segments (P < 0.0001; Figure 5c), indicating that superior incisions minimize vascular compromise. Quantification of tyrosine hydroxylase-positive nerves (Figure 5d) revealed denser sympathetic innervation in superior sections, predominantly associated with the deep γ-branch, while the b1 territory exhibited relatively lower neural density.

Table 2. Percentage distribution of arterial and venous densities in gallbladder H&E-stained sections.

Figure 5. (a) Optimal incision level across gallbladder sections; (b) Comparative vascular density in a1 versus b1 territories (P < 0.005); (c) Comparison of vascular density between superior and inferior segments (arteries P = 0.3914, veins P < 0.0001); (d) Quantification of sympathetic nerve density.

4 Discussion

While Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy (LC) remains the gold standard for gallstone disease, it is not without long-term sequelae. A prospective multicenter study (Wennmacker et al., 2017) indicates that up to 41% of patients may experience persistent abdominal symptoms following organ removal. This concern is particularly amplified in pediatric populations—such as the 4-year-old donor in our study—where organ preservation is prioritized to support long-term development. Regarding the comparison with radical resection, recent comprehensive clinical analyses regarding pediatric cholelithiasis and surgical outcomes (Akhtar-Danesh et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2025) indicate that for selected patients, preserving strategies should be carefully weighed against cholecystectomy. In this context, our anatomical study aims to provide a precise safety map to further optimize this organ-preserving approach by minimizing neurovascular injury.

Conventional clinical focus centers on the cystic artery and its variants (e.g., duplicated arteries) (Zhu et al., 2023) in cholecystectomy contexts. In contrast, this study prioritizes mapping pericholecystic and intramural vascular patterns to optimize surgical approaches for gallbladder-preserving cholelithotomy (GPC). Digital modeling revealed that the pericholecystic arterial architecture comprises a deep branch (γ) and bifurcated superficial branches, namely, the right α-artery and left β-artery. Notably, the γ-branch anastomoses with the α-artery, while the δ-vein courses parallel to the α-artery. Sympathetic nerves exhibit diffuse intramural distribution, with denser clustering in the neck and body regions.

Statistical analyses of vascular and neural densities across gallbladder sections identified the superior aspect and left-sided b1-territory as low-vascularity zones, with concomitantly reduced sympathetic innervation in the b1-territory. The branched architecture of the α-artery and its anastomosis with the deep γ-branch denote structural dominance over the β-artery, validating the b1-superior quadrant as the optimal incision site to minimize iatrogenic injury in gallbladder-preserving procedures.

Synthesizing these findings, we strongly recommend a left-biased longitudinal incision along the gallbladder-hepatic interface. This approach leverages proximity to the minimally branched β-artery to reduce major vasculature injury risk, while the inherent low microvascular density minimizes collateral damage. Furthermore, concomitant neural preservation maintains physiological contractile function (Zhang et al., 2014). Critically, maximal distance from the deep γ-branch further mitigates iatrogenic trauma, ensuring unimpaired nutrient delivery to the gallbladder parenchyma post procedure, thereby enhancing postprocedural recovery of contractile and absorptive functions (Zhang et al., 2017).

In contrast to our strategy, our topological analysis indicates that conventional fundal incisions traverse the anastomosis zone between the deep γ-branch and α-artery, thereby posing a significant risk of disrupting this vascular network. This vascular compromise could theoretically impair local perfusion, potentially affecting postoperative recovery. Consequently, our perspective advocates for an incision placement that respects this vascular anatomy, diverging from conventional gallbladder-preserving cholelithotomy utilizing fundal incisions (Costamagna et al., 2002). Concurrently, we pioneer a novel application methodology regarding the serial section-based modeling framework applicable to pathological tissues. This approach significantly enhances the delineation of tissue invasion patterns and spatial distribution profiles (Zhang et al., 2020), thereby refining pathological diagnostics with superior precision (Tan et al., 2016).

Future investigations should use electron microscopy to capture microscopic gallbladder vasculature, enabling construction of higher-fidelity digital gallbladder models. Advancing artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, particularly deep learning applications (Zhang et al., 2023), will significantly enhance identification efficiency for vascular and neural structures.

5 Limitations

Several limitations of this study must be acknowledged to avoid clinical overgeneralization. First, the 3D reconstruction was based on a single specimen from a healthy 4-year-old donor. While this provided a pristine, non-fibrotic baseline for mapping native neurovascular topology, it does not account for age-dependent vascular remodeling or inter-individual anatomical variations prevalent in the adult population. Second, the absence of pathological changes—such as chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and gallstone burden—limits the direct translatability of our findings to clinical cases where tissue architecture may be significantly distorted. Consequently, the neurovascular ‘safety zones’ identified herein should be interpreted as anatomical recommendations based on ideal topology rather than absolute surgical rules. Future studies incorporating adult cadaveric specimens and pathological samples are essential to validate the robustness of this incision strategy across diverse patient cohorts.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Southern Medical University (approval number [2023]18). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

XL: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. XY: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. PY: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. HW: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. TF: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. ZX: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. QJ: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. ZL: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. SP: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. TH: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. XF: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. YL: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. YW: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. JO: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review and editing. JD: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. SW: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant number 2022YFF1202600) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 31370994).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; PFA, paraformaldehyde; IHC, immunohistochemistry; SEM, Scanning electron microscopy; GPC, gallbladder-preserving cholelithotomy.

References

Abdalla S., Pierre S., Ellis H. (2013). Calot's triangle. Clin. Anat. 26, 493–501. doi:10.1002/ca.22170

Akhtar-Danesh G. G., Doumouras A. G., Bos C., Flageole H., Hong D. (2018). Factors associated with outcomes and costs after pediatric laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JAMA Surg. 153, 551–557. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5461

Costamagna G., Tringali A., Shah S. K., Mutignani M., Zuccalà G., Perri V. (2002). Long-term follow-up of patients after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis, and risk factors for recurrence, Endoscopy, 34:273–279. doi:10.1055/s-2002-23632

Gijtenbeek J. M., Wesseling P., Maass C., Burgers L., van der Laak J. A. (2005). Three-dimensional reconstruction of tumor microvasculature: simultaneous visualization of multiple components in paraffin-embedded tissue, Angiogenesis 8:297–305. doi:10.1007/s10456-005-9019-4

Housset C., Chrétien Y., Debray D., Chignard N. (2016). Functions of the gallbladder. Compr. Physiol. 6, 1549–1577. doi:10.1002/cphy.c150050

Kiemen A. L., Braxton A. M., Grahn M. P., Han K. S., Babu J. M., Reichel R., et al. (2022). CODA: quantitative 3D reconstruction of large tissues at cellular resolution. Nat. Methods 19, 1490–1499. doi:10.1038/s41592-022-01650-9

Kiemen A. L., Damanakis A. I., Braxton A. M., He J., Laheru D., Fishman E. K., et al. (2023). Tissue clearing and 3D reconstruction of digitized, serially sectioned slides provide novel insights into pancreatic cancer. Med 4, 75–91. doi:10.1016/j.medj.2022.11.009

Krishnamurthy G. T., Bobba V. R., Kingston E. (1981). Radionuclide ejection fraction: a technique for quantitative analysis of motor function of the human gallbladder. Gastroenterology 80, 482–490. doi:10.1016/0016-5085(81)90009-3

Łabętowicz P., Zielinska N., Pilewski D., Olewnik Ł., Ruzik K. (2025). New clinical view on the relationship between the diameter of the deep femoral artery and sex: index δ-Anatomical and radiological study biomedicines 13. Biomedicines 13, 1428. doi:10.3390/biomedicines13061428

Martins M. R. P., Alves J. A., Melo M. M., Caldas J. V. J., Araujo Júnior E., Szejnfeld P. S. O., et al. (2025). Prenatal diagnosis of Phrygian cap gallbladder: two- and three-dimensional ultrasound. Magnetic Reson. Imaging, Three-Dimensional Reconstr. J Med Ultrasound 33, 73–76. doi:10.4103/jmu.jmu_109_23

Morgan M. R., Broder J. S., Dahl J. J., Herickhoff C. D. (2018). Versatile low-cost volumetric 3-D ultrasound platform for existing clinical 2-D systems. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 37, 2248–2256. doi:10.1109/tmi.2018.2821901

Pesce A., Fabbri N., Feo C. V. (2023). Vascular injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an often-overlooked complication. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 15, 338–345. doi:10.4240/wjgs.v15.i3.338

Portincasa P., Moschetta A., Palasciano G. (2006). Cholesterol gallstone disease. Lancet 368, 230–239. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(06)69044-2

Qu Q., Chen W., Liu X., Wang W., Hong T., Liu W., et al. (2020). Role of gallbladder-preserving surgery in the treatment of gallstone diseases in young and middle-aged patients in China: results of a 10-year prospective. Study Surg. 167, 283–289. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2019.09.001

Rojo Ríos D., Ramírez Z. G., Soler Laguía M., Kilroy D., Martínez Gomariz F., Sánchez Collado C., et al. (2023). Creation of three-dimensional anatomical vascular and biliary models for the study of the feline liver (Felis silvestris catus L.): a comparative CT, volume rendering (vr), cast and 3D printing. Study Anim. (Basel) 13. doi:10.3390/ani13101573

Schiewe J. A., Miranda L. H. G., Romano R. M., Romano M. A. (2025). Anatomic variations of the cystic artery during cholecystectomies: is it important for the surgeon to know? Arq. Bras. Cir. Dig. 38, e1880. doi:10.1590/0102-67202025000011e1880

Segovia-Miranda F., Morales-Navarrete H., Kücken M., Moser V., Seifert S., Repnik U., et al. (2019). Three-dimensional spatially resolved geometrical and functional models of human liver tissue reveal new aspects of NAFLD progression. Nat. Med. 25, 1885–1893. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0660-7

Sicklick J. K., Camp M. S., Lillemoe K. D., Melton G. B., Yeo C. J., Campbell K. A., et al. (2005). Surgical management of bile duct injuries sustained during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: perioperative results in 200 patients. Ann. Surg. 241, 786–792. ; discussion 793-785. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000161029.27410.71

Sun R., Ge L., Dong L., Shi R., Yan Z., Liu S., et al. (2025). Pediatric cholelithiasis: a comprehensive analysis of clinical characteristics and surgical treatment strategies, Transl. Pediatr. 14:2546–2560. doi:10.21037/tp-2025-367

Tan Y. Y., Zhao G., Wang D., Wang J. M., Tang J. R., Ji Z. L. (2013). A new strategy of minimally invasive surgery for cholecystolithiasis: calculi removal and gallbladder preservation. Dig. Surg. 30, 466–471. doi:10.1159/000357823

Tan T., Qu Y. W., Shu J., Liu M. L., Zhang L., Liu H. F. (2016). Diagnostic value of high-resolution micro-endoscopy for the classification of Colon polyps. World J. Gastroenterol. 22, 1869–1876. doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i5.1869

Tang R., Zhou C. X., Yang Y., Bian J., Meng L. X., Wei D. C., et al. (2024). Gallbladder preserving cholelithotomy in children with hereditary spherocytosis complicated by gallstones: a single-center retrospective study, Front. Pediatr. 12:1457927. doi:10.3389/fped.2024.1457927

Thiyagarajah N., Witek A., Davison M., Butler R., Erdemir A., Tsiang J., et al. (2025). Histological analysis of intracranial cerebral arteries for elastin thickness, wall thickness, and vessel diameters: an atlas for computational modeling and a proposed predictive multivariable model of elastin thickness. J. Clin. Med. 14, 4320. doi:10.3390/jcm14124320

Venneman N. G., van Erpecum K. J. (2010). Pathogenesis of gallstones. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 39, 171–183. vii. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2010.02.010

Wennmacker S., Lamberts M., Gerritsen J., Roukema J. A., Westert G., Drenth J., et al. (2017). Consistency of patient-reported outcomes after cholecystectomy and their implications on current surgical practice: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Surg. Endosc. 31, 215–224. doi:10.1007/s00464-016-4959-x

Yang J., Fang C., Fan Y., Peng G., Xiang N., Zhu W., et al. (2014). Construction of a three-dimensional visualization model of arteries supplying the extrahepatic bile duct based on submillimeter CT data. Nan Fang. Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 34, 945–949. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1673-4254.2014.07.06

Ye Y. Q., Liang Q., Li E. Z., Gong J. L., Fan J. M., Wang P. (2023). 3D reconstruction of a gallbladder duplication to guide LC: a case report and literature review. Med. Baltim. 102, e33054. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000033054

Zhang Z. M., Liu Z., Liu L. M., Zhang C., Yu H. W., Wan B. J., et al. (2017). Therapeutic experience of 289 elderly patients with biliary diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 23, 2424–2434. doi:10.3748/wjg.v23.i13.2424

Zhang Z. H., Qin C. K., Wu S. D., Xu J., Cui X. P., Wang Z. Y., et al. (2014). Roles of sphincter of oddi motility and serum vasoactive intestinal peptide, gastrin and cholecystokinin octapeptide. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 4730–4736. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i16.4730

Zhang J., Yao K., Liu P., Liu Z., Han T., Zhao Z., et al. (2020). A radiomics model for preoperative prediction of brain invasion in meningioma non-invasively based on MRI: a multicentre study. EBioMedicine 58, 102933. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102933

Zhang X., Li W., Gao C., Yang Y., Chang K. (2023). Hyperspectral pathology image classification using dimension-driven multi-path attention residual network. Expert Syst. Appl. 230, 120615. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.120615

Zhao Y., Chen T., Wang H., Xue Q., Guo W., Ding G., et al. (2022). Influence of three-dimensional visual reconstruction technology combined with virtual surgical planning of CTA images on precise resection of liver cancer in hepatobiliary. Surg. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022, 4376654. doi:10.1155/2022/4376654

Zhu A. Y., Seyfi D., Sandroussi C., Abeysinghe J. D. (2023). Aberrant vascular anatomy during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a case report of double cystic artery crsls 10. 10. doi:10.4293/crsls.2023.00038

Keywords: gallstones, minimally invasive surgery, precision slicing, surgical approach, three-dimensional reconstruction, vascular distribution

Citation: Li X, Ye X, Yang P, Wu H, Fan T, Xiao Z, Jiang Q, Lin Z, Peng S, Huang T, Feng X, Liang Y, Wang Y, Ouyang J, Dai J and Wang S (2026) Digital modeling of the gallbladder for revealing microanatomical features and optimizing surgical approaches in gallbladder-preserving cholelithotomy. Front. Physiol. 16:1710325. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2025.1710325

Received: 22 September 2025; Accepted: 30 December 2025;

Published: 14 January 2026.

Edited by:

Christina Maria Pabelick, Mayo Clinic, United StatesReviewed by:

Sungin Lee, Chungbuk National University, Republic of KoreaParamate Horkaew, Suranaree University of Technology, Thailand

Copyright © 2026 Li, Ye, Yang, Wu, Fan, Xiao, Jiang, Lin, Peng, Huang, Feng, Liang, Wang, Ouyang, Dai and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yu Wang, MTIwNzBAaGJ1YXMuZWR1LmNu; Jun Ouyang, am91eWFuZ0BzbXUuZWR1LmNu; Jingxing Dai, ZGFpanhAc211LmVkdS5jbg==, ZGFpangyMDEzQDE2My5jb20=; Sangui Wang, d3Nnd2t5c0AxNjMuY29t

†ORCID: Tingyu Fan, orcid.org/0000-0002-2985-8823; Jun Ouyang, orcid.org/0000-0002-8475-3696; Jingxing Dai, orcid.org/0000-0002-9339-9174

‡These authors have contributed equally to this work

Xiangtian Li1‡

Xiangtian Li1‡ Peng Yang

Peng Yang Jingxing Dai

Jingxing Dai