- 1Immunorheumatology Research Laboratory, IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Milan, Italy

- 2Department of Pharmacy, Section of Medicinal Chemistry, University of Genova, Genova, Italy

- 3Department of Cardiology, Istituto Auxologico Italiano IRCCS, Milan, Italy

- 4Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Milano-Bicocca, Milan, Italy

- 5Dipartimento di Scienze Cliniche e di Comunità, Dipartimento di Eccellenza 2023-2027, University of Milan, Milan, Italy

Hypertension stands as one of the most significant preventable risk factors for cardiovascular disease, which is the leading cause of mortality worldwide. There is a disturbing gap, in preclinical research, between simplified cell culture and complex in vivo models. To contribute to bridge this gap, we have developed a simplified but realistic in vitro dynamic model of hypertension allowing the discrimination between mechanical pressure effects and Angiotensin II’s pharmacological action. We utilized an advanced bioreactor system capable of producing adjustable flow rates to culture human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC). This system allows for the investigation of the possible effects of Angiotensin II and/or an increase in intraluminal pressure (via the Live-Pa pressure-actuation device) exerted directly upon the HUVEC monolayer without simulating transmural pressure. Key hypertension-associated inflammatory markers, such as NF-kB, p38MAPK, Interleukins (IL)-6/8, and Endothelin-1 (ET-1), were subsequently assessed. Angiotensin II induced HUVEC NF-kB and p38MAPK phosphorylation, and elevated IL-6 and ET-1 secretion, with a trend in IL-8 increase. Live-Pa alone enhanced NF-kB and p38MAPK and influenced cytokine/chemokine secretion. Combined stimuli significantly augmented the inflammatory parameters as compared to unstimulated cells, suggesting a synergistic effect between chemical and mechanical stimuli. Overall, these in vitro results demonstrate both key consistencies (e.g., NF-kB and p38MAPK activation) and specific distinctions (e.g., no significant IL-6 increase in Live-Pa-exposed versus control HUVEC) when compared to published data from hypertensive versus normotensive animal models. The proposed advanced in vitro model may successfully reproduce some features of vascular function in hypertension and simulate hemodynamic conditions by controlled flow with adjustable pressure parameters. Crucially, this system allows discrimination between mechanical blood pressure effects and Angiotensin II’s pharmacological action on the endothelium, paving the way for understanding pathophysiological mechanisms and developing new therapies. Established methods make it possible that studies on cultured endothelial cells will be better comparable to the results of in vivo studies, thus directly supporting the 3Rs framework—Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement—which is essential for high-standard and ethical research.

1 Introduction

Hypertension stands as one the most significant preventable risk factor for cardiovascular disease, which is the leading cause of mortality worldwide. This chronic condition affects several hundred millions of people globally and often develops progressively over years before manifesting serious health complications (Danaei et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2017). One of the main challenges is to understand the intricate network of biochemical connections underlying the pathophysiological mechanisms responsible for this risky condition. Therefore, targeted investigation are required to unmask key functional mechanisms and pathways behind hypertension. In the last decade, extensive studies have confirmed what had been increasingly evident: inflammation is an essential player in the development and progression of the hypertensive condition. Animal models and clinical studies have established connections between hypertension and activation of both innate and adaptive immune systems, which can cause systemic damage (Shi et al., 2010; Singh et al., 2014; Tracey, 2014; Santisteban et al., 2015; Calvillo et al., 2019; Youwakim and Girouard, 2021; Pugh and Dhaun, 2021; Hengel et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2023; Aboukhater et al., 2023; Guzik et al., 2024; Nguyen et al., 2024; Zubcevic et al., 2014; Carnevale et al., 2014; Harrison, 2014). In vitro and in vivo experimental research must investigate the interconnected pathways that regulate pressure responses, as disruptions in these networks can lead to various disorders, including abnormal blood pressure levels (Calvillo et al., 2019; Zubcevic et al., 2014; Kapoor et al., 2016).

With such a complex network to study, basic research faces methodological challenges: animal models provide comprehensive but overly complex systems with multiple interacting variables, while traditional in vitro cell cultures are too simplistic, lacking physiological conditions and intercellular communication. Despite limitations in isolating specific pathways, animal experiments still dominate hypertension research (Cook et al., 2001; Healey et al., 2003; Mitchell et al., 2007; Cook and Re, 2012; Lerman et al., 2019); therefore, advanced in vitro systems are needed to bridge the gap between simple cell cultures and animal experiments, while better replicating physiological conditions without multiple organ system interference (Vozzi et al., 2011; Ucciferri et al., 2014; Marchesi et al., 2020). These tools align with the 3Rs framework (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) (MacArthur, 2018).

Some in vitro dynamic models have been developed to mimic at least to some degree the in vivo endothelial environment. The fundamental principles for constructing adjustable shear stress flow chambers, critical for generating the flow regimes, have recently been established (Fallon et al., 2022). The use of human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) monolayers subjected to pulsatile perfusion to construct simplified vascular models in bioreactors is a recognized approach in vascular tissue engineering (Helms et al., 2021). Furthermore, the influence of shear rate on inflammatory responses, such as adhesion molecule expression, in microfluidic in vitro models has been demonstrated (Rotenberg et al., 2012), with prior work also examining the combined effects of pulsatile wall shear stress and tensile hoop strain in HUVEC (Breen et al., 2010).

The current study aimed to develop an advanced bioreactor dynamic model connectible to a peristaltic pump which reproduces mechanical flow-dependent shear stress, and to test the Live-Pa device able to increase the intraluminal pressure directly on the HUVEC monolayer. Such model mirrors physiological conditions that the endothelium, a key initiator and sensor of hemodynamic forces, experiences in living organs (Vozzi et al., 2011; Vernazza et al., 2021). Furthermore, this system should allow the controlled exposure of the cells to soluble mediators, such as Angiotensin II (ANG II), a peptide hormone causing vasoconstriction, blood pressure increase and direct chronic inflammatory effects on vascular cells, thereby enabling the distinction between mechanical blood pressure effects and pharmacological actions. This setup might favour the understanding of the mechanisms leading to hypertension and developing of new therapies.

Several inflammatory factors were published in the literature as significantly associated with hypertensive condition. Among them, Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB), p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinases (p38 MAPK), Interleukin-8 (IL-8) and Interleukin-6 (IL-6), were found to be overexpressed in animal model of hypertension and increased in serum of hypertensive patients (Calvillo et al., 2019; Ju et al., 2003; Dai et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017; Tanase et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2020; Mohammed et al., 2022; Song et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2006; Basson et al., 2015; Geng et al., 2019). Accordingly, we investigated these inflammatory mediators in our model. We also evaluated Endothelin-1 (ET-1) as a potent vasoconstrictor peptide, focusing on its critical role as a major product of vascular endothelial cells, which is known to be increased in several experimental models of hypertension (Mohammed et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2023; Xue et al., 2022; Schiffrin, 1999).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Modular dynamic multi-compartmental cell culture system

The modular dynamic device, developed by IVtech (IVTech Srl, Ospedaletto, PI, Italy), allows 2D or 3D cell culturing both in static and dynamic conditions. This system provides two different transparent 24 well plate-like culture chambers (bioreactors): Live-Box (LB) type 1 and type 2. LB1 is equipped with a removable glass slide supporting cell monolayer or 3D constructs and a flow inlet and outlet for the perfusion of culture media. LB2 allows the modelling of physiological barriers in vitro through a porous selective membrane (specific for each cell type) housed in a removable holder. It also has two flow inlets and outlets. In our study, we employed only LB1 for culturing endothelial cells (ECs) in 2D conditions.

A peristaltic pump (Live-Flow, IVTech) connected to bioreactors and reservoirs applies an adjustable flow rate (range 100–450 μL/min) mimicking blood flow circulation (Figure 1A). The current model primarily addresses the effects of flow (shear stress) and pressure exerted directly upon the monolayer. Currently, the model applies a horizontal flow, whose pressure acts on the monolayer without crossing it (i.e., not mimicking transmural pressure). The immediate focus of this model is to consider the blood vessel as a simple conduit, without examining phenomena of extravasation. The shear stress (

Figure 1. Setting. Dynamic in-vitro culture system. Original photos of the equipment and colorimetric map of the shear stress distribution: (A)- the peristaltic pump (Live Flow) able to perform an adjustable flow rate (100–450 μl/min) is connected both to bioreactor and reservoir mimicking blood flow circulation (left). Details of the LB1 (right, up) and magnification of the HUVEC monolayer inside the LB1 (right, bottom) are shown. (B)- colorimetric map of the shear stress distribution with wall shear stress magnitude diagrams. Up: the map illustrates the distribution of shear stress across the surface of the slide inside the LB1. The velocity is also indicated along the streamlines. Bottom: Shear stress distribution. The graph illustrates the shear stress distribution across the diameter of the LB1 slide, measured in the direction perpendicular to the inlet-outlet axis. The x-axis represents the slide’s length in tenths of a millimetre, and the y-axis shows the shear stress measured in Pascals (1 Pa = 10 dyne/cm2). (C) - Dynamic device with Live Pa (left); the LB1connected to Live-Pa with the black piston inducing pressure increase (center); and the dynamic device equipped with two LB1 and Live-Pa inside the incubator (right).

Where µ is the dynamic viscosity of the fluid and dv/dz represents the velocity gradient across the channel’s cross-section.

This formula, accounting for the specific geometry and flow profile, was calculated automatically by the numerical simulation software, Simflow, used to generate the colorimetric map of the shear stress distribution (Figure 1B).

The device may be implemented by a pressure modulator, Live-Pa, which allows to increase the hydrodynamic pressure with a motorized piston reducing the lumen of the outlet tube of a chamber and increasing the pressure like a disease scenario (e.g., hypertension) (Figure 1C).

The Live-Pa applies pressure to cells in the bioreactor subjected to flow, which can be varied from 101.3 to 151.1 to 202.6 Pascal, corresponding to 0.75, 1.13, and 1.52 mmHg, respectively. Live-Pa offers the capability to increase the pressure incrementally by 50%, 100%, or 200%. A 50% increase was selected in our study to better model human hypertension, where such an increase is often compatible with the clinical condition. The crucial parameter is the ratio between the applied overpressure and the basal pressure of the system, rather than the absolute pressure value itself. This model is scaled in relation to the physiological in vivo reality; therefore, there is no direct 1:1 correspondence between the specific values used in the model and the actual values measured in vivo, as well as there isn't a direct 1:1 mapping between the model’s biological structures and those found in vivo. The change in velocity is localized to the segment of the tubing undergoing Live-Pa compression downstream the bioreactor. As we were operating within a closed-loop system, the peristaltic pump imposed a constant flow, overriding any transient, localized velocity changes that might occur due to compression in a different part of the circuit.

Endothelial monolayer in LB1 is shown in Figure (Figure 1A).

2.2 Cells

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were purchased from Promocell (Heidelberg, Germany) and grown in the provided Endothelial Cell Growth Medium Ready-to-use (Promocell) in humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Confluent cells were detached with specific Detachkit-30 (Promocell), and 80.000 cells in 2 mL of complete medium were seeded in 24 well/plate and 200,000 cells in 20 µL in LB1. These cell numbers were used in all the investigated conditions to avoid any experimental variability.

Four hrs later, 2 mL of complete medium were added in LB1 and cells were cultured in static state for further 24 h to reach the confluence.

Parallel experiments were performed in the presence of 100 μL/min of flow for further 24 h to mimic dynamic environment.

Confluent HUVEC cells were subjected to two distinct stimuli, applied individually or in combination. The pharmacological stimulus consisted of ANG II at a concentration of 1,000 nM (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, United States, catalog number A9525), which was applied for a total duration of 24 h under both static and dynamic flow conditions. The ANG II dose and exposure regimen were determined based on relevant literature (Marchesi et al., 2020; Deng et al., 2015), evaluating the effect of the molecule on the expression of several immune factors in HUVECs and other cardiovascular cells. The mechanical stimulus by Live-Pa device, applied an acute 50% pressure increase to the circuit. This mechanical stress was maintained for a specific duration of 2 h, either alone or combined with ANG II.

Cells were incubated with LPS (1 μg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number L4516) or medium alone for 24 h in the conditions described above, as experimental controls.

HUVEC morphology and uniform monolayer preservation were evaluated by inverted microscopy (Olympus CKX53, EP50, Shinyuku, Tokio, Japan) in all the experimental settings (Figure 1A).

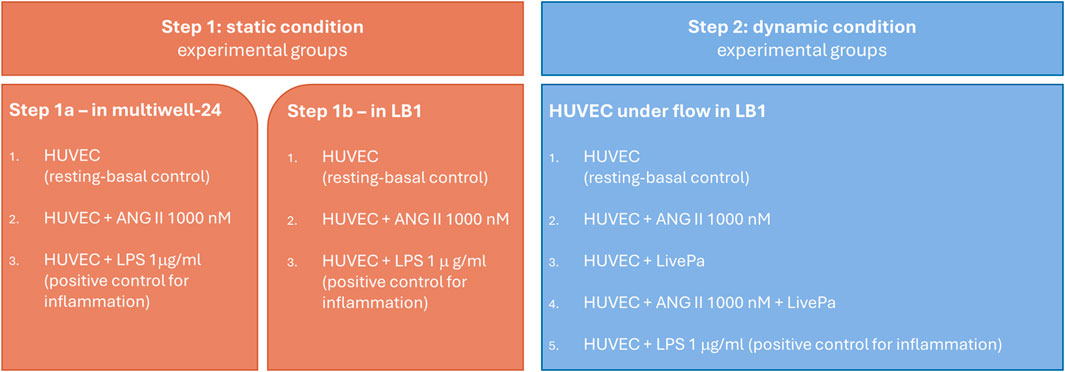

The detailed experimental design is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Experimental Design. Human vein umbilical endothelial cell (HUVEC) cultures in static (step 1) and dynamic conditions (step 2). Confluent cells were treated with ANG II for 24 h in both conditions. In step 2, 50% pressure increase was applied by Live-Pa to the circuit for 2 h, alone or in combination with ANG II.

2.3 Evaluation of NF-kB and p38MAPK activation

The activation (phosphorylation) rate of NF-κB) and p38MAPK was assessed in HUVEC seeded in LB1 incubated with ANG II (1,000 nM) for 24 h both in static and dynamic conditions, in the presence or absence of Live-Pa (2 h) by Western blotting. Control cultures were treated with LPS (1 μg/mL) or medium alone.

Total proteins were isolated using RIPA Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, United States, catalog number BK9806S) added with 1% Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog number P8340) and protein concentration was measured using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, catalog number 23227).

Proteins (10 μg/lane) along with a molecular weight ladder (ThermoFisher Scientific, catalog number #SM1841) were fractionated by NuPAGE BIS-TRIS by 4%–12% SDS-polyacrylamide pre-cast gel electrophoresis (ThermoFisher Scientific, catalog number NP0321BOX) and transferred to nitrocellulose using iBlot 3 Transfer Stacks Nitrocellulose (ThermoFisher Scientific, catalog number IB33002).

The membranes were blocked for 2 h at room temperature (RT) in PBS/0.05% Tween 20 (PT) (Cell Signaling Technology) containing 5% non-fat dry milk (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, United States) and incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-human NFκB (1:1,000 in PT plus 5% BSA, Cell Signaling Technology, catalog number #8242) or anti-human phosphorylated NFκB (pNFκB, 1:1,000 in PT plus 5% BSA, Cell Signaling Technology, catalog number #3039) or anti-human p38MAPK (1:1,000 in PT plus 5% BSA, Cell Signaling Technology, catalog number #9212) or anti-human phosphorylated p38MAPK (pp38MAPK, 1:1,000 in PT plus 5% BSA, Cell Signaling Technology, catalog number #9211) After three washes, the membranes were incubated for 1 h at RT in PT/5% non-fat dry milk plus HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5000, Cell Signaling Technology, catalog number #7074) and developed using ECL (Westar Supernova, Cyanagen, Bologna, IT, catalog number XLS3,0100). Signals were detected using radiographic films (Kodak, Rochester, NY, United States). The ImageJ software (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, US) was used to analyze and quantify gels. Results were expressed as the ratio of phosphorylated to non-phosphorylated forms, normalized to the respective control.

To identify the protein of interest when the exposure time was too short to impress the X-ray film, its position was identified by a protein ladder transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane from the SDS-polyacrylamide pre-cast gel (Liang et al., 2013) (Supplementary Figure S1).

2.4 Measurement of inflammatory mediators secretion

Supernatants were collected at the end of each experiment and frozen at −20 °C for further analyses. The selected mediators IL-6 and IL-8 were measured using the automated microfluidic analyzer ELLA (Bio-Techne, Minneapolis, MN, United States, Simple plex Cartridge kit, catalog number 356322). ELLA-SimplePlex technology allows biomarkers to be quantified in 25 µL of supernatants in a multiplex format, with extremely high reproducibility. This system uses cartridges pre-loaded with everything necessary for biomarker quantification, including the calibration curve. To perform the assay, the sample was diluted in the provided buffer and loaded into the cartridge, for ELLA analysis. The concentrations of each analyte (pg/ml, mean of three reading) were obtained from the specific calibration curve using the system’s software.

Minimum detectable level for IL-6 is 0.7 pg/mL (range 0.7–2.652 pg/mL) and for IL-8 is 0.08 pg/mL (range 0.19–1.8 pg/mL). ET-1 was quantified by commercial Kit ELISA (Bio-Techne, catalog number DET100), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A standard curve was generated by plotting the mean absorbance for each standard on the y-axis against the concentration on the x-axis. The data were linearized by plotting the log of the ET-1 concentration versus the log of the optical density (OD). The sample concentration was calculated interpolating OD values in the standard curve ranging from 0 pg/mL to 25 pg/mL.

The minimum detectable dose of ET-1 is 0.031(range 0.031–0.207 pg/mL).

The sample concentration obtained from the two different systems was multiplied by a factor 7 corresponding to the total volume circulating in the device.

2.5 Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were shown as mean and standard error (SEM). The Mann-Whitney test was used for comparisons of quantitative variables between two groups. Due to the exploratory nature of the study, no comparison of multiple tests was applied. All the analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 5.01. Statistical significance was set at the 0.05 level. All P-values were two-sided.

3 Results

3.1 Intracellular signaling pathways

LPS (1 μg/mL) strongly activated both NFkB and p38 MAPK phosphorylation in HUVEC seeded in LB1, under static and dynamic conditions, compared to the culture medium alone (Figures 3A,B). These observations confirm the functional validation and biological responsiveness of the device, as they are consistent with those obtained using traditional in vitro plates (Wang et al., 2023; Raschi et al., 2003; Cai et al., 2021), specifically demonstrating that our system accurately captures the LPS-induced activation of key inflammatory signaling pathways.

Figure 3. Intra-cellular signaling pathways in unstimulated or LPS-stimulated HUVEC seeded in LB1, cultured in static or dynamic conditions. NFkB (A) and p38MAPK (B) phosphorylation after stimulation with LPS (1 μg/mL). Endothelial cells seeded in LB1 for 24 h were incubated with LPS or medium alone both in static and under flow for further 24 h, as experimental control. Results are expressed as the ratio of phosphorylated to non-phosphorylated form, normalized to the respective control and evaluated using Image J software. Western Blotting images are representative of a single experiment. Histograms represent mean of three independent experiments. pNFkB: phosphorylated NFkB; p38MAPK: phosphorylated p38MAPK.

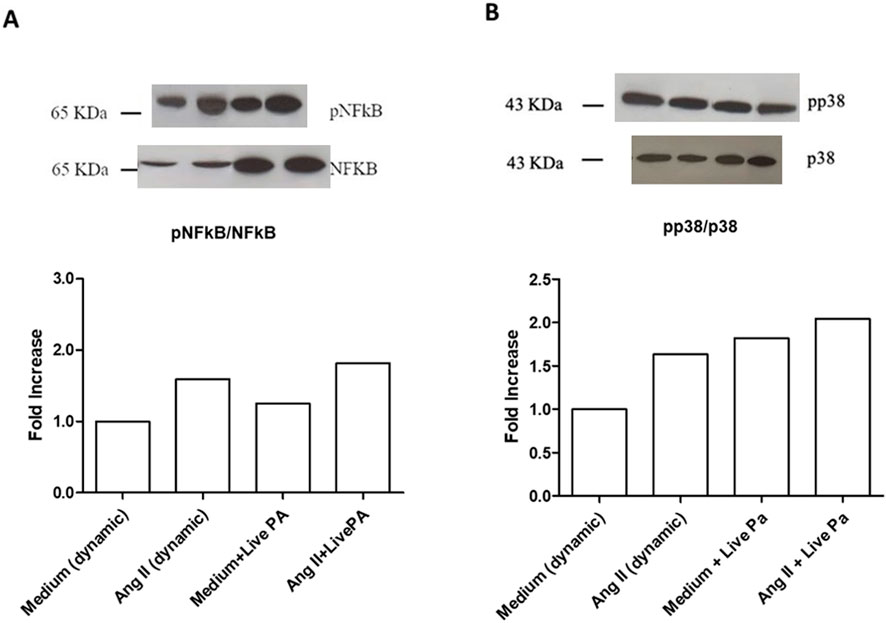

Treatment with ANG II (1,000 nM) for 24 h induced high phosphorylation of NFkB in static conditions and under flow (Figure 4A). The same effect was observed for p38 MAPK phosphorylation in both dynamic and static milieu (Figure 4B). When Live-Pa was applied to the circuit for 2 h, the activation rate of the intracellular signaling pathways (NFkB and p38 MAPK) was upregulated with respect to the medium alone (Figures 5A,B). No differences were observed in NFkB phosphorylation levels between the ANG II/Live-Pa combination and ANG II alone, while an increase in p38 MAPK activation was detected in the cells treated with ANG II in combination with Live-Pa versus ANG II alone (Figures 5A,B).

Figure 4. Intra-cellular signaling pathways in unstimulated or Angiotensin II-stimulated HUVEC seeded in LB1, cultured in static or dynamic conditions. NFkB (A) and p38MAPK (B) phosphorylation after stimulation with ANG II (1,000 nM). Endothelial cells seeded in LB1 for 24 h were incubated with Angiotensin II or medium alone both in static and under flow for further 24 h. Results are expressed as the ratio of phosphorylated to non-phosphorylated form, normalized to the respective control and evaluated using Image J software. Western Blotting images are representative of a single experiment. Histograms represent mean of three independent experiments. pNFkB: phosphorylated NFkB; p38MAPK: phosphorylated p38MAPK.

Figure 5. Intra-cellular signaling pathways in HUVEC seeded in LB1, cultured in static or dynamic conditions, unstimulated or stimulated with Angiotensin II and Live-PA, individually or in combination. NFkB (A) and p38MAPK (B) phosphorylation after stimulation with ANG II (1,000 nM) alone or in combination with Live-Pa. Endothelial cells seeded in LB1 for 24 h were stimulated with ANG II under flow for 24 h. Live-Pa was applied for further 2 h in the presence of medium or ANG II. Results are expressed as the ratio of phosphorylated to non-phosphorylated form, normalized to the dynamic control and evaluated using Image J software. Western Blotting images are representative of a single experiment. Histograms represent mean of three independent experiments. pNFkB: phosphorylated NFkB; p38MAPK: phosphorylated p38MAPK.

3.2 Cytokine and chemokine secretion

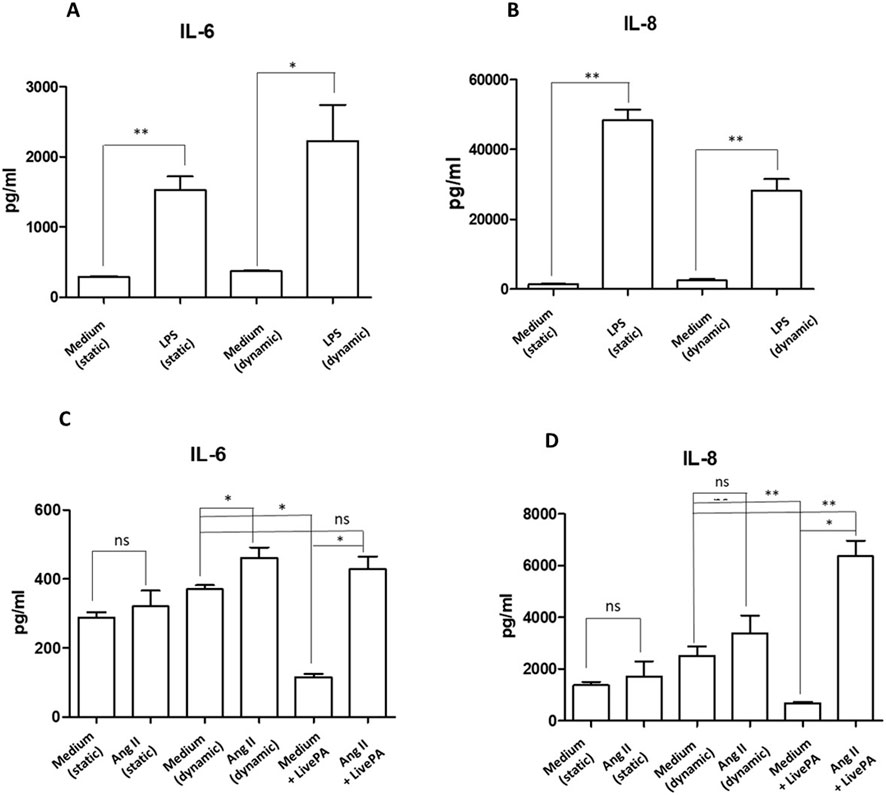

Endothelial cells treated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 24 h resulted in a significant increase of the cytokine IL-6 secretion both in static and dynamic conditions (Figure 6A). Similarly, IL-8 levels were significantly upregulated in LPS treated cells in both conditions (Figure 6B). These findings are consistent with results observed when endothelial cells are cultured and stimulated with LPS in traditional plates, confirming the validity of the multicompartmental system as an advanced culture model (Wang et al., 2023; Raschi et al., 2003; Cai et al., 2021; Li et al., 2006).

Figure 6. Cytokine secretion. IL-6 (A) and IL-8 (B) protein levels in supernatants from HUVEC resting or stimulated with LPS (1 μg/mL) both in static and under flow for 24 h, as positive experimental control. Histograms represent mean +standard error of the mean (SEM). *p < 0.05 **p < 0.01 versus respective controls (static or dynamic medium). IL-6 (C) and IL-8 (D) protein levels in supernatants from HUVEC resting or stimulated with ANG II (1,000 nM) and Live-Pa, individually or in combination. Endothelial cells seeded in LB1 for 24 h were stimulated with ANG II (1,000 nM) under flow for 24 h. Live-Pa was applied for further 2 h in the presence of medium or ANG II. (Histograms represent mean +standard error of the mean (SEM) *p < 0.05 vs. medium + Live-Pa. **p < 0.01 versus medium (dynamic).

Exposure to ANG II (1,000 nM) for 24 h led to a slight increase in IL-6 levels in the supernatants collected from LB1 under static conditions. When flow was applied, cytokine levels were significantly up-regulated. Moreover, mechanical stimulation with Live-Pa for 2 h in combination with ANG II significantly enhanced IL-6 secretion compared to Live-Pa alone, but induced a slight increase versus control (medium) (Figure 6C).

Treatment with ANG II for 24 h caused a mild increase in chemokine IL-8 secretion both in static and dynamic environments. Conversely, when the Live-Pa device was applied in combination with ANG II treatment, significantly higher IL-8 levels were observed (Figure 6D).

3.3 Endothelin I release

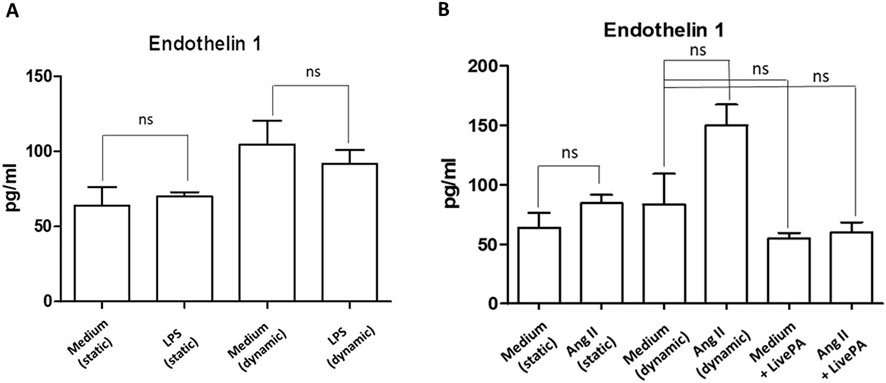

When treated with LPS (1 μg/mL), in both static and dynamic conditions, Endothelin I levels did not change (Figure 7A). Treatment with ANG II (1,000 nM) induced a more evident upregulation of the investigated protein in the dynamic environment compared to the static one, even if it was not statistically significant. When Live-Pa was added to the circuit, a downregulation of Endothelin I levels was observed, compared to ANG II alone (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. Endothelin I secretion. (A) Endothelin I secretion in HUVEC seeded in LB1, cultured in static or dynamic conditions, and unstimulated or stimulated with LPS (1 μg/mL), as positive experimental control. Histograms represent mean +standard error of the mean (SEM). (B) Endothelin I secretion in HUVEC seeded in LB1, cultured in static or dynamic conditions, resting or in the presence of ANG II (1,000 nM) and Live-Pa, individually or in combination. Endothelial cells seeded in LB1 for 24 h were stimulated with ANG II (1,000 nM) under flow for 24 h. Live-Pa was applied for further 2 h in the presence of medium or ANG II. Histograms represent mean +standard error of the mean (SEM).

4 Discussion

This study reports a new advanced in vitro approach utilizing a millifluidic platform to reproduce and investigate the early signaling features of hypertensive stress. The specific focus is on the individual and combined effects of mechanical stress and ANG II on endothelial NF-kB and p38 MAPK activation, and associated inflammatory cytokine release (IL-6 and IL-8). To investigate the early molecular signaling events and acute activation of the two pathways triggered by the combined hemodynamic and biochemical stress, we intentionally applied a short 2-h mechanical stimulus. Such acute stress should highlight the initial endothelial response to hypertensive stress in our system.

The critical innovation lies in incorporating controlled flow with adjustable pressure parameters, which enables simulation of the hemodynamic conditions seen in hypertensive states and reproduces certain features of inflammation, a recognized hallmark of the condition. Accordingly, over the past two decades, research has increasingly revealed a clear connection between inflammation and hypertension, with evidence from both human patients and animal studies demonstrating that inflammation plays several crucial roles in how hypertension develops and progresses (Calvillo et al., 2019; Ju et al., 2003; Dai et al., 2016; Basson et al., 2015; Park et al., 2007; Bao et al., 2007; Luft, 2001; Ruiz-Ortega et al., 1998; Dornas et al., 2017; Luo et al., 2015; Miguel-Carrasco et al., 2010; Hammer et al., 2017; Winklewski et al., 2015; Benigni et al., 2010; Harrison et al., 2011; Marvar et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2015; Martynowicz et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2022; Patrick et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2011).

Based on data in the literature, NF-kB, p38MAPK, IL-8 and IL-6 appear significantly associated with hypertensive condition. Published studies strongly highlights the pronounced difference in inflammatory cytokine levels as well as in pro-inflammatory transcription factors and signalling pathways between spontaneously hypertensive and normotensive rats, further confirming the critical role of inflammation in the pathophysiology of hypertension. In details, NF-κB, a key intracellular inflammatory signal protein whose expression is elevated in arterial vascular cells during hypertension, regulates oxidative stress, angiogenesis, and apoptosis, while p38 MAPK controls cell differentiation and apoptosis. Both pathways are increased in hypertensive rats’ vessels respect to normotensive control animals (Calvillo et al., 2019; Ju et al., 2003; Dai et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017; Basson et al., 2015; Duansak and Schmid-Schönbein, 2013). The IL-8 chemokine and the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 are overexpressed in hypertension, with IL-6 promoting ANG II-induced hypertension (Calvillo et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2020; Mohammed et al., 2022; Song et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2006; Geng et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2015; Martynowicz et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2011; Dusi et al., 2016).

In our study, these markers were measured in HUVEC subjected to the consequences of mechanical blood pressure increase and the pharmacological action of ANG II. The two different stimuli were applied individually or in combination, in order to discriminate between a mechanical pressure-increase impact and the biochemical effects of ANG II. NF-kB and p38-MAPK activation increased, particularly after Live-Pa/ANG II combined exposure, confirming their in vitro roles as players in the hypertensive state. This effect was consistent with the trends observed in vessels from SHR vs. normotensive Wistar Kyoto rats (WKY) in in-vivo studies (Duansak and Schmid-Schönbein, 2013; Bhatt et al., 2014; Luo et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2015; Hanson et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2019). Similarly, IL-8 secretion after hypertensive stimuli had more than doubled after the combined treatment, compared to control medium. These results mirror observations from basal measurements in hypertensive animal vessels compared to the WKY ones (Kim et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2011), and suggest that our millifluidic model successfully captures key early activation of signaling pathways characteristic of hypertensive stimuli in the vasculature. In our in vitro model IL-6 showed only a slight (10%) increase after HUVEC exposure to Live-Pa/ANG II combined treatment compared to control cultures. These results evidence a key difference from in-vivo observations in hypertensive animals, in which circulating IL-6 is higher when compared to normotensive rats (Geng et al., 2019; Li et al., 2011). This discrepancy likely stems from the absence of paracrine amplification; in fact, high IL-6 levels in in-vivo hypertension have been shown to be mediated by the infiltration and activation of immune cells, such as T lymphocytes, which are the main source of the massive systemic IL-6 increase and are missing in our 2D monoculture (Senchenkova et al., 2019).

When mechanical and biochemical stimuli were applied separately, an interesting observation emerged: the secretion of inflammatory cytokines IL-8 and IL-6 under stimulation with Live-Pa alone was significantly lower than in the control flow condition. While our model is observational and cannot provide definitive mechanistic insight, the transient nature of the mechanical stimulus bears a certain resemblance to the physiological blood pressure elevation experienced during physical exercise. The resulting increased oxygen demand stimulates the heart to increase its rate, with a physiological rise in blood pressure as a normal adaptation to physical exertion. Data in literature suggesting an association between exercise and anti-inflammatory effects may offer a plausible explanation, though unproven, for the observed reduction in cytokine secretion under Live-Pa alone (Briones and Touyz, 2009; Dorneles et al., 2016). On the other hand, ANG II treatment alone caused significant inflammatory activation, evidenced by both significantly increased phosphorylation of NF-κB and p38-MAPK at the cellular level and enhanced IL-8 content, which is consistent with literature findings (Guo et al., 2006; Nabah et al., 2004) and supports the efficiency of our model.

When we investigated ET-1, a potent vasoconstrictor peptide, the molecule showed an endothelin-independent pattern after exposure of HUVEC to Live-Pa + ANG II, similarly to what has been described in SHR animals (Schiffrin, 1999).

The ET-1 behaviour observed in our model is highly significant, as the endothelin axis is centrally involved in the vascular pathology of hypertension. Our in vitro platform might provide mechanistic insight into how isolated or combined hemodynamic and biochemical stimuli modulate this potent vasoconstrictor at the level of the endothelium. This early mechanism is crucial, given that ET-1 and its related pathways are known to drive cardiac and vascular remodeling in hypertension, representing a potential target for novel therapeutic strategies (Gaydarski et al., 2025). In a broader translational context, by specifically examining ET-1 and other inflammatory markers, the output of our system can potentially contribute to the understanding of early biochemical steps that lead to systemic consequences of hypertension, such as organ-specific remodeling and functional deterioration observed in key targets (e.g., the kidney) (Gaydarski et al., 2024).

Collectively, our findings point toward a synergistic pro-inflammatory effect between chemical and mechanical stimuli on endothelial cells, and support the potential of our dynamic multi-compartmental cell culture system to model specific, early signaling features of in-vivo hypertensive stress.

Moreover, allowing the identification of potential critical mechanisms at endothelium level, our advanced dynamic platform might offer a valuable screening tool for investigating known and newly developed anti-hypertensive molecules.

5 Future perspectives

We are going to test potential protective effects of a consolidated privileged scaffolds in medicinal chemistry (core structures of bioactive compounds), as pyrazole, imidazopyrazole derivatives (Meta et al., 2017; Selvatici et al., 2013; Lusardi et al., 2022) and others (Alfei et al., 2022). These molecules were previously identified as inhibitors or modulator of hypertension-related inflammatory factors, as p38MAPK, NFkB signalling and cytokine production.

From a pharmacological perspective, our dynamic system with Live-Pa could serve as a platform for developing and characterizing new therapeutic molecules for hypertension-related inflammation. This advanced dynamic in vitro model could reduce animal use and costs while providing an alternative method for detecting adverse effects in initial pharmacological screening. Future applications will also include a more complex multi-compartmental dynamic model in which cells from different organs and systems, including the immune system, may interact (Bodio et al., 2024).

6 Study limitations

We took into account other factors known to play a role in hypertension, i.e. IL-17, (Calvillo et al., 2019; Harrison, 2014; Robles-Vera et al., 2021; Guo et al., 2015; Madhur et al., 2010), VEGF (Advani et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2018) and CXCL12 (Calvillo et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2018; Masson et al., 2015). However, these mediators were undetectable by ELISA in our experimental conditions (data not shown), possibly owing to their low secretion levels and/or high dilution in the flow circuit. To overcome this bias, we might concentrate the culture supernatants and/or employ high sensitivity assays. A further limitation concerns the use of HUVEC, which do not necessarily represent the microcirculation, which undoubtedly plays a relevant role in hypertension development as well as in the macrocirculation (Laurent et al., 2022). Finally, our study was purposefully designed to be purely exploratory and hypothesis-generating, rather than a primary, confirmatory hypothesis test. Our proof-of-concept analysis was focused on evaluating the performance of the platform and its efficiency in mimicking in vivo hypertensive conditions. In this context, choosing not to apply a multi-group correction is a recognized methodological approach.

Future studies are being planned to confirm these results and extend the research to different vascular cells (i.e. microcirculation endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells), also implementing the complexity of our multifluidic system.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the ZENODO repository [DOI 10.5281/zenodo.17191714].

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies on humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because only commercially available established cell lines were used.

Author contributions

ER: Data curation, Writing - review and editing, Formal Analysis, Writing - original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization. CaB: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Conceptualization, Writing - review and editing, Methodology, Writing - original draft. ChB: Writing - original draft, Data curation, Writing - review and editing, Formal Analysis, Conceptualization. GP: Formal Analysis, Conceptualization, Writing - review and editing, Data curation, Writing - original draft. PM: Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing - review and editing, Formal Analysis, Writing - original draft. MB: Writing - review and editing, Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Data curation, Writing - original draft. LC: Funding acquisition, Resources, Formal Analysis, Writing - review and editing, Data curation, Supervision, Writing - original draft, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by Alan and Helene Goldberg program (former CAAT Grant) under grant Project #2023-02 (https://caat.jhsph.edu/alan-and-helene-goldberg-in-vitro-toxicology-grants/), and by Global 3Rs Award 2022 granted to LC (https://www.aaalac.org/awards/global-3rs-winners/).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Benedetta Mercuriali for graphic design assistance and figure preparation.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author PM declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Large Language Model (LLM) trained by Google, with knowledge access and data updated until October 2025 for the purposes of text rephrasing, grammar checking and creating conceptual figures based on text descriptions. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2025.1724932/full#supplementary-material

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S1 | Image of uncropped blots.

SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE S1 | Excel file with reference details of studies reporting the baseline differences in the levels of inflammatory markers NF-kB, p38MAPK, Interleukins (IL)-6/8, between SHR and WKY blood vessels.

References

Aboukhater D., Morad B., Nasrallah N., Nasser S. A., Sahebkar A., Kobeissy F., et al. (2023). Inflammation and hypertension: underlying mechanisms and emerging understandings. J. Cell. Physiology 238, 1148–1159. doi:10.1002/jcp.31019

Advani A., Kelly D. J., Advani S. L., Cox A. J., Thai K., Zhang Y., et al. (2007). Role of VEGF in maintaining renal structure and function under normotensive and hypertensive conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 14448–14453. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703577104

Alfei S., Caviglia D., Zorzoli A., Marimpietri D., Spallarossa A., Lusardi M., et al. (2022). Potent and broad-spectrum bactericidal activity of a nanotechnologically manipulated novel pyrazole. Biomedicines 10, 907. doi:10.3390/biomedicines10040907

Bao W., Behm D. J., Nerurkar S. S., Ao Z., Bentley R., Mirabile R. C., et al. (2007). Effects of p38 MAPK inhibitor on angiotensin II-dependent hypertension, organ damage, and superoxide anion production. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 49, 362–368. doi:10.1097/FJC.0b013e318046f34a

Basson J. J., De Las Fuentes L., Rao D. C. (2015). Single nucleotide polymorphism–single nucleotide polymorphism interactions among inflammation genes in the genetic architecture of blood pressure in the framingham heart study. Am. J. Hypertens. 28, 248–255. doi:10.1093/ajh/hpu132

Benigni A., Cassis P., Remuzzi G. (2010). Angiotensin II revisited: new roles in inflammation, immunology and aging. EMBO Mol. Med. 2, 247–257. doi:10.1002/emmm.201000080

Bhatt S. R., Lokhandwala M. F., Banday A. A. (2014). Vascular oxidative stress upregulates angiotensin II type I receptors via mechanisms involving nuclear factor kappa B. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. (New York, N. Y. 1993) 36, 367–373. doi:10.3109/10641963.2014.943402

Bodio C., Milesi A., Lonati P. A., Chighizola C. B., Mauro A., Pradotto L. G., et al. (2024). Fibroblasts and endothelial cells in three-dimensional models: a new tool for addressing the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis as a prototype of fibrotic vasculopathies. IJMS 25, 2780. doi:10.3390/ijms25052780

Breen L. T., McHugh P. E., Murphy B. P. (2010). HUVEC ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 synthesis in response to potentially athero-prone and athero-protective mechanical and nicotine chemical stimuli. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 38, 1880–1892. doi:10.1007/s10439-010-9959-8

Briones A. M., Touyz R. M. (2009). Moderate exercise decreases inflammation and oxidative stress in hypertension: but what are the mechanisms? Hypertension 54, 1206–1208. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.136622

Cai G.-L., Yang Z.-X., Guo D.-Y., Hu C.-B., Yan M.-L., Yan J. (2021). Macrophages enhance lipopolysaccharide induced apoptosis via Ang1 and NF-κB pathways in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Sci. Rep. 11, 2918. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-82531-7

Calvillo L., Gironacci M. M., Crotti L., Meroni P. L., Parati G. (2019). Neuroimmune crosstalk in the pathophysiology of hypertension. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 16, 476–490. doi:10.1038/s41569-019-0178-1

Carnevale D., Pallante F., Fardella V., Fardella S., Iacobucci R., Federici M., et al. (2014). The angiogenic factor PlGF mediates a neuroimmune interaction in the spleen to allow the onset of hypertension. Immunity 41, 737–752. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2014.11.002

Chen M., Chen Z.-W., Long Z.-J., Wang J.-T., Wang Y.-J., Liu J.-L. (2015). Protective effects of Sapindus saponins in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 21, 36–42. doi:10.1007/s11655-013-1464-0

Cook J. L., Re R. N. (2012). Review: lessons from in vitro studies and a related intracellular angiotensin II transgenic mouse model. Am. J. Physiology-Regulatory, Integr. Comp. Physiology 302, R482–R493. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00493.2011

Cook J. L., Zhang Z., Re R. N. (2001). In vitro evidence for an intracellular site of angiotensin action. Circulation Res. 89, 1138–1146. doi:10.1161/hh2401.101270

Dai H., Hu W., Jiang L., Li L., Gaung X., Xiao Z. (2016). p38 MAPK inhibition improves synaptic plasticity and memory in angiotensin II-dependent hypertensive mice. Sci. Rep. 6, 27600. doi:10.1038/srep27600

Danaei G., Ding E. L., Mozaffarian D., Taylor B., Rehm J., Murray C. J. L., et al. (2009). The preventable causes of death in the United States: comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors. PLoS Med. 6, e1000058. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000058

Deng B., Fang F., Yang T., Yu Z., Zhang B., Xie X. (2015). Ghrelin inhibits angii-induced expression of TNF-α, IL-8, MCP-1 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 8, 579–588.

Dornas W. C., Cardoso L. M., Silva M., Machado N. L. S., Chianca D. A., Alzamora A. C., et al. (2017). Oxidative stress causes hypertension and activation of nuclear factor-κB after high-fructose and salt treatments. Sci. Rep. 7, 46051. doi:10.1038/srep46051

Dorneles G. P., Haddad D. O., Fagundes V. O., Vargas B. K., Kloecker A., Romão P. R. T., et al. (2016). High intensity interval exercise decreases IL-8 and enhances the immunomodulatory cytokine interleukin-10 in lean and overweight–obese individuals. Cytokine 77, 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2015.10.003

Duansak N., Schmid-Schönbein G. W. (2013). The oxygen free radicals control MMP-9 and transcription factors expression in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Microvasc. Res. 90, 154–161. doi:10.1016/j.mvr.2013.09.003

Dusi V., Ghidoni A., Ravera A., De Ferrari G. M., Calvillo L. (2016). Chemokines and heart disease: a network connecting cardiovascular biology to immune and autonomic nervous systems. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 5902947. doi:10.1155/2016/5902947

Fallon M. E., Mathews R., Hinds M. T. (2022). In vitro flow chamber design for the study of endothelial cell (Patho)Physiology. J. Biomechanical Eng. 144, 020801. doi:10.1115/1.4051765

Gaydarski L., Dimitrova I. N., Stanchev S., Iliev A., Kotov G., Kirkov V., et al. (2024). Unraveling the complex molecular interplay and vascular adaptive changes in hypertension-induced kidney disease. Biomedicines 12, 1723. doi:10.3390/biomedicines12081723

Gaydarski L., Petrova K., Stanchev S., Pelinkov D., Iliev A., Dimitrova I. N., et al. (2025). Morphometric and molecular interplay in hypertension-induced cardiac remodeling with an emphasis on the potential therapeutic implications. IJMS 26, 4022. doi:10.3390/ijms26094022

Geng J., Zhao Z., Yang L., Zhang M., Liu X. (2019). Protein Kinase D was involved in vascular remodeling in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 41, 299–306. doi:10.1080/10641963.2018.1469647

Guo R. W., Yang L. X., Li M. Q., Liu B., Wang X. M. (2006). Angiotensin II induces NF-κB activation in HUVEC via the p38MAPK pathway. Peptides 27, 3269–3275. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2006.08.014

Guo Z., Sun H., Zhang H., Zhang Y. (2015). Anti-hypertensive and renoprotective effects of berberine in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 37, 332–339. doi:10.3109/10641963.2014.972560

Guzik T. J., Nosalski R., Maffia P., Drummond G. R. (2024). Immune and inflammatory mechanisms in hypertension. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 21, 396–416. doi:10.1038/s41569-023-00964-1

Hammer A., Stegbauer J., Linker R. A. (2017). Macrophages in neuroinflammation: role of the renin-angiotensin-system. Pflugers Archiv Eur. J. Physiology 469, 431–444. doi:10.1007/s00424-017-1942-x

Hanson M. G., Taylor C. G., Wu Y., Anderson H. D., Zahradka P. (2016). Lentil consumption reduces resistance artery remodeling and restores arterial compliance in the spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 37, 30–38. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.07.014

Harrison D. G. (2014). The immune system in hypertension. Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. 125, 130–140. doi:10.1152/advan.00063.2013

Harrison D. G., Guzik T. J., Lob H. E., Madhur M. S., Marvar P. J., Thabet S. R., et al. (2011). Inflammation, immunity, and hypertension. Hypertension 57, 132–140. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.163576

Healey C., Forgione P., Lounsbury K. M., Corrow K., Osler T., Ricci M. A., et al. (2003). A new in vitro model of venous hypertension: the effect of pressure on dermal fibroblasts. J. Vasc. Surg. 38, 1099–1105. doi:10.1016/S0741-5214(03)00556-1

Helms F., Lau S., Aper T., Zippusch S., Klingenberg M., Haverich A., et al. (2021). A 3-Layered bioartificial blood vessel with physiological Wall architecture generated by mechanical stimulation. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 49, 2066–2079. doi:10.1007/s10439-021-02728-9

Hengel F. E., Benitah J.-P., Wenzel U. O. (2022). Mosaic theory revised: inflammation and salt play central roles in arterial hypertension. Cell Mol. Immunol. 19, 561–576. doi:10.1038/s41423-022-00851-8

Ju H., Behm D. J., Nerurkar S., Eybye M. E., Haimbach R. E., Olzinski A. R., et al. (2003). p38 MAPK inhibitors ameliorate target organ damage in hypertension: part 1. p38 MAPK-dependent endothelial dysfunction and hypertension. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 307, 932–938. doi:10.1124/jpet.103.057422

Kapoor K., Bhandare A. M., Nedoboy P. E., Mohammed S., Farnham M. M. J., Pilowsky P. M. (2016). Dynamic changes in the relationship of microglia to cardiovascular neurons in response to increases and decreases in blood pressure. Neuroscience 329, 12–29. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.04.044

Kim H. Y., Choi J. H., Kang Y. J., Park S. Y., Choi H. C., Kim H. S. (2011). Reparixin, an inhibitor of CXCR1 and CXCR2 receptor activation, attenuates blood pressure and hypertension-related mediators expression in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Biol. and Pharm. Bull. 34, 120–127. doi:10.1248/bpb.34.120

Kim H. Y., Cha H. J., Choi J. H., Kang Y. J., Park S. Y., Kim H. S. (2015). CCL5 inhibits elevation of blood pressure and expression of hypertensive mediators in developing hypertension state spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Bacteriol. Virol. 45, 138. doi:10.4167/jbv.2015.45.2.138

Kim H. Y., Hong M. H., Yoon J. J., Kim D. S., Na S. W., Jang Y. J., et al. (2020). Protective effect of Vitis labrusca leaves extract on cardiovascular dysfunction through HMGB1-TLR4-NFκB signaling in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Nutrients 12, 3096. doi:10.3390/nu12103096

Laurent S., Agabiti-Rosei C., Bruno R. M., Rizzoni D. (2022). Microcirculation and macrocirculation in hypertension: a dangerous cross-link? Hypertension 79, 479–490. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.17962

Lee D. L., Sturgis L. C., Labazi H., Osborne J. B., Fleming C., Pollock J. S., et al. (2006). Angiotensin II hypertension is attenuated in interleukin-6 knockout mice. Am. J. Physiology-Heart Circulatory Physiology 290, H935–H940. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00708.2005

Lerman L. O., Kurtz T. W., Touyz R. M., Ellison D. H., Chade A. R., Crowley S. D., et al. (2019). Animal models of hypertension: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Hypertension 73, e87–e120. doi:10.1161/HYP.0000000000000090

Li Y., Du B., Pan J., Chen D., Liu D. (2006). Up-regulation interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 by activated protein C in lipopolysaccharide-treated human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 7, 899–905. doi:10.1631/jzus.2006.B0899

Li D. J., Evans R. G., Yang Z. W., Song S. W., Wang P., Ma X. J., et al. (2011). Dysfunction of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway mediates organ damage in hypertension. Hypertension 57, 298–307. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.160077

Liang W., Mason A. J., Lam J. K. W. (2013). Western blot evaluation of siRNA delivery by pH-Responsive peptides. In: Methods Mol. Biol. 986. 73–87. doi:10.1007/978-1-62703-311-4_5

Liu T., Zhang L., Joo D., Sun S.-C. (2017). NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2, e17023. doi:10.1038/sigtrans.2017.23

Liu X., Chen L., Zhang Y., Wu X., Zhao Y., Wu X., et al. (2018). Associations between polymorphisms of the CXCL12 and CNNM2 gene and hypertension risk: a case-control study. Gene 675, 185–190. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2018.06.107

Luft F. C. (2001). Angiotensin, inflammation, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 3, 61–67. doi:10.1007/s11906-001-0082-y

Luo H., Wang X., Wang J., Chen C., Wang N., Xu Z., et al. (2015). Chronic NF-κB blockade improves renal angiotensin II type 1 receptor functions and reduces blood pressure in Zucker diabetic rats. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 14, 76. doi:10.1186/s12933-015-0239-7

Luo M., Cao C., Niebauer J., Yan J., Ma X., Chang Q., et al. (2021). Effects of different intensities of continuous training on vascular inflammation and oxidative stress in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 25, 8522–8536. doi:10.1111/jcmm.16813

Lusardi M., Profumo A., Rotolo C., Iervasi E., Rosano C., Spallarossa A., et al. (2022). Regioselective synthesis, structural characterization, and antiproliferative activity of novel tetra-substituted phenylaminopyrazole derivatives. Molecules 27, 5814. doi:10.3390/molecules27185814

MacArthur C. J. (2018). The 3Rs in research: a contemporary approach to replacement, reduction and refinement. Br. J. Nutr. 120, S1–S7. doi:10.1017/S0007114517002227

Madhur M. S., Lob H. E., McCann L. A., Iwakura Y., Blinder Y., Guzik T. J., et al. (2010). Interleukin 17 promotes angiotensin II–Induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. Hypertension 55, 500–507. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.145094

Marchesi N., Barbieri A., Fahmideh F., Govoni S., Ghidoni A., Parati G., et al. (2020). Use of dual-flow bioreactor to develop a simplified model of nervous-cardiovascular systems crosstalk: a preliminary assessment. PLoS ONE 15, 1–16. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0242627

Martynowicz H., Janus A., Nowacki D., Mazur G. (2014). The role of chemokines in hypertension. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 23, 319–325. doi:10.17219/acem/37123

Marvar P. J., Lob H., Vinh A., Zarreen F., Harrison D. G. (2011). The central nervous system and inflammation in hypertension. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 11, 156–161. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2010.12.001

Masson G. S., Nair A. R., Silva Soares P. P., Michelini L. C., Francis J. (2015). Aerobic training normalizes autonomic dysfunction, HMGB1 content, microglia activation and inflammation in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of SHR. Am. J. Physiology Heart Circulatory Physiology 309, H1115–H1122. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00349.2015

Meta E., Brullo C., Sidibe A., Imhof B. A., Bruno O. (2017). Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of new pyrazolyl-ureas and imidazopyrazolecarboxamides able to interfere with MAPK and PI3K upstream signaling involved in the angiogenesis. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 133, 24–35. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.03.066

Miguel-Carrasco J. L., Zambrano S., Blanca A. J., Mate A., Vázquez C. M. (2010). Captopril reduces cardiac inflammatory markers in spontaneously hypertensive rats by inactivation of NF-kB. J. Inflamm. 7, 21. doi:10.1186/1476-9255-7-21

Mitchell B. M., Wallerath T., Förstermann U. (2007). Animal models of hypertension. Methods Molecular Medicine 139, 105–111. doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-571-8_6

Mohammed S. A. D., Liu H., Baldi S., Chen P., Lu F., Liu S. (2022). GJD modulates cardiac/Vascular inflammation and decreases blood pressure in hypertensive rats. Mediat. Inflamm. 2022, 1–19. doi:10.1155/2022/7345116

Nabah Y. N. A., Mateo T., Estellés R., Mata M., Zagorski J., Sarau H., et al. (2004). Angiotensin II induces neutrophil accumulation in vivo through generation and release of CXC chemokines. Circulation 110, 3581–3586. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000148824.93600.F3

Nguyen B. A., Alexander M. R., Harrison D. G. (2024). Immune mechanisms in the pathophysiology of hypertension. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 20, 530–540. doi:10.1038/s41581-024-00838-w

Park J.-K., Fischer R., Dechend R., Shagdarsuren E., Gapeljuk A., Wellner M., et al. (2007). p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibition ameliorates angiotensin II–Induced target organ damage. Hypertension 49, 481–489. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000256831.33459.ea

Patrick D. M., Van Beusecum J. P., Kirabo A. (2021). The role of inflammation in hypertension: novel concepts. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 19, 92–98. doi:10.1016/j.cophys.2020.09.016

Pugh D., Dhaun N. (2021). Hypertension and vascular inflammation: another piece of the genetic puzzle. Hypertension 77, 190–192. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.16420

Raschi E., Testoni C., Bosisio D., Borghi M. O., Koike T., Mantovani A., et al. (2003). Role of the MyD88 transduction signaling pathway in endothelial activation by antiphospholipid antibodies. Blood 101, 3495–3500. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-08-2349

Robles-Vera I., de la Visitación N., Toral M., Sánchez M., Gómez-Guzmán M., Jiménez R., et al. (2021). Mycophenolate mediated remodeling of gut microbiota and improvement of gut-brain axis in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Biomedecine and Pharmacother. 135, 111189. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2020.111189

Rotenberg M. Y., Ruvinov E., Armoza A., Cohen S. (2012). A multi-shear perfusion bioreactor for investigating shear stress effects in endothelial cell constructs. Lab. Chip 12, 2696–2703. doi:10.1039/c2lc40144d

Ruiz-Ortega M., Bustos C., Hernández-Presa M. A., Lorenzo O., Plaza J. J., Egido J. (1998). Angiotensin II participates in mononuclear cell recruitment in experimental immune complex nephritis through nuclear factor-kappa B activation and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 synthesis. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950 161, 430–439.

Santisteban M. M., Ahmari N., Carvajal J. M., Zingler M. B., Qi Y., Kim S., et al. (2015). Involvement of bone marrow cells and neuroinflammation in hypertension. Circulation Res. 117, 178–191. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.305853

Schiffrin E. L. (1999). Role of Endothelin-1 in hypertension. Hypertension 34, 876–881. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.34.4.876

Selvatici R., Brullo C., Bruno O., Spisani S. (2013). Differential inhibition of signaling pathways by two new imidazo-pyrazoles molecules in fMLF-OMe- and IL8-stimulated human neutrophil. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 718, 428–434. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.07.045

Senchenkova E. Y., Russell J., Yildirim A., Granger D. N., Gavins F. N. E. (2019). Novel role of T cells and IL-6 (Interleukin-6) in angiotensin II–Induced microvascular dysfunction. Hypertension 73, 829–838. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12286

Shi P., Diez-Freire C., Jun J. Y., Qi Y., Katovich M. J., Li Q., et al. (2010). Brain microglial cytokines in neurogenic hypertension. Hypertension 56, 297–303. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.150409

Singh M. V., Chapleau M. W., Harwani S. C., Abboud F. M. (2014). The immune system and hypertension. Immunol. Res. 59, 243–253. doi:10.1007/s12026-014-8548-6

Song T., Zhou M., Li W., Lv M., Zheng L., Zhao M. (2022). The anti-inflammatory effect of vasoactive peptides from soybean protein hydrolysates by mediating serum extracellular vesicles-derived miRNA-19b/CYLD/TRAF6 axis in the vascular microenvironment of SHRs. Food Res. Int. 160, 111742. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111742

Tanase D. M., Gosav E. M., Radu S., Ouatu A., Rezus C., Ciocoiu M., et al. (2019). Arterial hypertension and interleukins: potential therapeutic target or future diagnostic marker? Int. J. Hypertens. 2019, 1–17. doi:10.1155/2019/3159283

Tracey K. J. (2014). Hypertension: an immune disorder? Immunity 41, 673–674. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2014.11.007

Ucciferri N., Sbrana T., Ahluwalia A. (2014). Allometric scaling and cell ratios in multi-organ in vitro models of human metabolism. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2, 1–10. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2014.00074

Vernazza S., Tirendi S., Passalacqua M., Piacente F., Scarfì S., Oddone F., et al. (2021). An innovative in vitro open-angle glaucoma model (IVOM) shows changes induced by increased ocular pressure and oxidative stress. IJMS 22, 12129. doi:10.3390/ijms222212129

Vozzi F., Mazzei D., Vinci B., Vozzi G., Sbrana T., Ricotti L., et al. (2011). A flexible bioreactor system for constructing in vitro tissue and organ models. Biotech and Bioeng. 108, 2129–2140. doi:10.1002/bit.23164

Wang J., Zhang J., Ding X., Wang Y., Li Z., Zhao W., et al. (2018). Differential microRNA expression profiles and bioinformatics analysis between young and aging spontaneously hypertensive rats. Int. J. Mol. Med. 41, 1584–1594. doi:10.3892/ijmm.2018.3370

Wang M., Feng J., Zhou D., Wang J. (2023). Bacterial lipopolysaccharide-induced endothelial activation and dysfunction: a new predictive and therapeutic paradigm for sepsis. Eur. J. Med. Res. 28, 339. doi:10.1186/s40001-023-01301-5

Winklewski P. J., Radkowski M., Wszedybyl-Winklewska M., Demkow U. (2015). Brain inflammation and hypertension: the chicken or the egg? J. Neuroinflammation 12, 85. doi:10.1186/s12974-015-0306-8

Xu J.-P., Zeng R.-X., Zhang Y.-Z., Lin S.-S., Tan J.-W., Zhu H.-Y., et al. (2023). Systemic inflammation markers and the prevalence of hypertension: a NHANES cross-sectional study. Hypertens. Res. 46, 1009–1019. doi:10.1038/s41440-023-01195-0

Xue Y., Li X., Wang Z., Lv Q. (2022). Cilostazol regulates the expressions of endothelin-1 and endothelial nitric oxide synthase via activation of the p38 MAPK signaling pathway in HUVECs. Biomed. Rep. 17, 77. doi:10.3892/br.2022.1560

Youwakim J., Girouard H. (2021). Inflammation: a mediator between hypertension and neurodegenerative diseases. Am. J. Hypertens. 34, 1014–1030. doi:10.1093/ajh/hpab094

Zhang L., Zhang Y., Wu Y., Yu J., Zhang Y., Zeng F., et al. (2019). Role of the balance of Akt and MAPK pathways in the exercise-regulated phenotype switching in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 5690. doi:10.3390/ijms20225690

Zhang Z., Zhao L., Zhou X., Meng X., Zhou X. (2022). Role of inflammation, immunity, and oxidative stress in hypertension: new insights and potential therapeutic targets. Front. Immunol. 13, 1098725. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.1098725

Zhang P., Li D., Zhu J., Hu J. (2023). Antihypertensive effects of Pleurospermum lindleyanum aqueous extract in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 308, 116261. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2023.116261

Zhou B., Bentham J., Di Cesare M., Bixby H., Danaei G., Cowan M. J., et al. (2017). Worldwide trends in blood pressure from 1975 to 2015: a pooled analysis of 1479 population-based measurement studies with 19·1 million participants. Lancet 389, 37–55. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31919-5

Keywords: human umbilical vein endothelial cells, hypertension, bioreactor, Live-Pa, Angiotensin II, dynamic culture, millifluidic in-vitro technology, 3Rs

Citation: Raschi E, Bodio C, Brullo C, Parati G, Meroni PL, Borghi MO and Calvillo L (2026) Direct simulation of hypertensive stress on endothelial cells: a streamlined model of in-vitro-hypertension. Front. Physiol. 16:1724932. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2025.1724932

Received: 14 October 2025; Accepted: 09 December 2025;

Published: 14 January 2026.

Edited by:

James Todd Pearson, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center (Japan), JapanReviewed by:

Lyubomir Gaydarski, Medical University Sofia, BulgariaAdriana Gonzalez-Villalva, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico

Copyright © 2026 Raschi, Bodio, Brullo, Parati, Meroni, Borghi and Calvillo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Laura Calvillo, bC5jYWx2aWxsb0BhdXhvbG9naWNvLml0

†ORCID: Laura Calvillo, orcid.org/0000-0002-5151-8243

‡These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

§These authors have contributed equally to this work and share last authorship

Elena Raschi

Elena Raschi Caterina Bodio

Caterina Bodio Chiara Brullo

Chiara Brullo Gianfranco Parati

Gianfranco Parati Pier Luigi Meroni

Pier Luigi Meroni Maria Orietta Borghi

Maria Orietta Borghi Laura Calvillo

Laura Calvillo