- Department of Physics and Astronomy, California State University, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Background: Calcium (Ca) leak from the sarcoplasmic reticulum contributes to cardiac arrhythmias, yet the structural mechanisms regulating spontaneous Ca release from ryanodine receptor type 2 (RyR2) clusters remain poorly understood.

Methods: We developed a computational model in which each RyR2 channel comprises four interacting subunits embedded within spatially organized clusters. This framework captures both cooperative gating within individual channels and coupling between neighboring channels.

Results: Our simulations reveal that spontaneous Ca spark timing depends exponentially on RyR2 cluster structural integrity. This exponential sensitivity means that modest disruptions in cluster structure, such as partial fragmentation, can increase spontaneous Ca spark frequency by 100–1,000 fold.

Conclusions: Cluster structural integrity provides a powerful control mechanism for Ca leak and represents a promising therapeutic target for restoring Ca homeostasis in cardiac myocytes.

Introduction

Calcium (Ca) signaling is fundamental to cardiac muscle contraction, with tightly regulated intracellular Ca release essential for effective excitation-contraction coupling (Bers, 2002). The RyR2, a large Ca release channel located on the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) membrane, plays a central role in this process. RyR2 is activated through calcium-induced calcium release (CICR), in which a small influx of Ca via L-type Ca channels (LCCs) during the cardiac action potential triggers a much larger release of Ca from the SR. Recent advances in super-resolution imaging techniques, have provided unprecedented insight into the spatial organization of RyR2 within cardiomyocytes (Sheard et al., 2022; Hurley et al., 2023; Mesa et al., 2022; Baddeley et al., 2009; Kolstad et al., 2018; Soeller and Jayasinghe, 2018; Jayasinghe et al., 2009) These methods have revealed that RyR2 channels form distinct, heterogeneous clusters whose size, density, and arrangement are critical determinants of Ca signaling dynamics. This detailed structural information now provides a framework for investigating how the organization of RyR2 clusters contributes to normal cardiac physiology, and how its disruption may lead to arrhythmogenesis (Fowler and Zissimopoulos, 2022; Waddell et al., 2023; Macquaide et al., 2015; Dixon, 2022; Benitah et al., 2021; Chen-Izu et al., 2007).

New imaging techniques have revealed that RyR2 clusters are not static structures, but instead show dynamic organization that can change significantly in disease (Kolstad et al., 2018; Waddell et al., 2023; Hiess et al., 2018). In healthy cardiomyocytes, RyR2 channels are arranged in compact organized clusters at dyads. In disease, however, this organization becomes disrupted. A common observation is cluster fragmentation, where large RyR2 assemblies break into smaller, irregularly shaped groupings. This reduces the number of channels per cluster and alters their spatial arrangement, with important consequences for Ca signaling. In an elegant study Sheard et al. (2022) used enhanced expansion microscopy to visualize this remodeling in three dimensions, revealing that fragmented RyR2 clusters often exhibit a frayed appearance. In these clusters, RyR2 channels remain partially anchored near the center of the cluster, where a structural protein called junctophilin-2 (JPH2) helps tether them to the membrane, but many RyRs extend outward in a disorganized, loosely connected pattern. This “fraying” suggests a loss of structural integrity in the regions where JPH2 is absent, marking the early breakdown of the tightly organized release sites essential for normal Ca signaling. In heart failure, similar changes are observed. Super-resolution imaging studies, such as those by Kolstad et al. (2018), have shown that RyR2 clusters become dispersed, forming smaller and more loosely organized sub-clusters. Also, in persistent atrial fibrillation, Macquaide et al. (2015) demonstrated that RyR2 cluster fragmentation results in more numerous, closely spaced clusters within Ca release units, accompanied by a greater than 50% increase in spontaneous Ca spark frequency. These structural changes are closely linked to key functional defects in heart failure, including elevated diastolic Ca leak, reduced contractile strength, and a greater risk of arrhythmias (Benitah et al., 2021; Ai et al., 2005; Marx and Marks, 2013).

Computational models have provided important insights into how RyR2 spatial organization affects calcium signaling. Recent studies have demonstrated that RyR2 interactions via Ca diffusion are critical for coordinating calcium release (Cannell et al., 2013), with network connectivity affecting whole-cell calcium oscillations (Gao et al., 2023) and cluster geometry influencing calcium spark properties (Iaparov et al., 2021; Li et al., 2025). These findings establish that spatial effects operate through multiple mechanisms, particularly diffusive calcium coupling between channels. However, existing models have not incorporated direct subunit coupling between adjacent RyR2 channels within clusters. Such coupling arises from the physical contacts between neighboring channels revealed by cryo-EM studies (Cabra et al., 2016) and represents a distinct mechanism through which cluster connectivity may regulate calcium release. In this study, we model a cluster of RyR2 channels as an array of interacting tetramers. Each RyR2 channel is composed of four subunits, and channels within the cluster are arranged with specific geometrical contacts that reflect their structural organization. We analyze the stochastic dynamics of this system to determine how the arrangement of neighboring channels influences the behavior of the cluster. Our focus is to understand how cluster architecture controls the timing of spontaneous Ca sparks. A central finding is that, at resting Ca concentrations, the frequency of spontaneous Ca sparks is exponentially sensitive to the structural integrity of the cluster. In this regime, small changes in arrangement, such as increased spacing, reduced connectivity, or fragmentation into sub-clusters, can increase the frequency of spontaneous Ca sparks by several orders of magnitude. This result highlights the crucial role of intact cluster architecture in maintaining coordinated channel closure at rest. We further show that frayed clusters are particularly vulnerable, since small peripheral groups of RyR2s can recruit larger assemblies through diffusive Ca coupling. Together, these results identify cluster architecture as a dominant control mechanism for Ca leak under diastolic conditions, linking cluster integrity to pathological Ca handling.

Methods

Computational model of RyR2 tetramer

The RyR2 channel is a tetramer composed of four identical subunits that gate a shared central pore. Structural studies show that these subunits are tightly packed and physically interact at their interfaces (Cabra et al., 2016; Woll and Van Petegem, 2022). Motivated by these observations and by our earlier modeling work (Greene et al., 2023), we describe a simplified RyR2 model in which each subunit can exist in one of two conformational states. A central assumption of the model is that adjacent subunits interact energetically, such that conformational mismatches are penalized. In particular, if a subunit transitions from closed to open while its neighbors remain closed, the resulting mismatch produces an energetic cost. This is implemented by modifying the transition rate so that the opening rate of a closed subunit is reduced by a multiplicative factor when neighbors are closed and increased when neighbors are open. An additional assumption is that a channel is considered functionally open when three or more subunits are in the open state. This requirement was established in our previous study (Greene et al., 2023), where we demonstrated that RyR2 channels must exhibit cooperative gating to remain reliably shut at diastolic Ca concentrations. Without this constraint, channels cannot maintain stable closure during rest.

To apply this model, we represent the RyR2 channel as four subunits labeled

where

Here,

Computational model of an RyR2 cluster

Recent Cryo-EM imaging studies due to Cabra et al. (2016) reveals that RyR2 channels physically interact at their interfaces through specific molecular contacts between adjacent channels. Their high-resolution structural analysis identifies two distinct types of inter-channel arrangements: an “adjoining” configuration (Figure 1A) and an “oblique” configuration (Figure 1B). In the adjoining arrangement, channels are aligned in regular rows and columns, with horizontal neighbors coupling through their edge-to-edge contacts. In the oblique arrangement (Figure 1B), channels adopt a staggered geometry with interactions between subunits 1–3 and 2–4 only. Cabra et al. observed that native RyR2 clusters typically form disordered structures that represent combinations of these two geometric arrangements rather than uniform arrays of a single type. To model these experimentally observed arrangements, we will consider cluster models based on both interaction types.

Figure 1. Architecture of RyR2 clusters. (A) Adjoining configuration. RyR2 tetramers are positioned in a side-by-side array, with neighboring channels aligned in rows and columns. In this arrangement, adjacent channels make contact along their lateral surfaces, consistent with the “side-by-side” geometry observed in cardiac cells. (B) Oblique configuration. RyR2 tetramers are connected in an alternating “checkerboard” pattern. This arrangement corresponds to the oblique interaction identified in structural studies, where subunits from diagonally offset channels (Bers, 2002; Sheard et al., 2022; Hurley et al., 2023; Sheard et al., 2022; Hurley et al., 2023; Mesa et al., 2022) form the interface.

To model heterogeneous arrays, we denote

where

To model inter-RyR2 interactions within a cluster, we arrange RyR2 channels either with the oblique or adjoining configurations shown in Figure 1. Each channel occupies a grid position labeled by coordinates

Model of Ca regulation of RyR2 cluster dynamics

Super-resolution imaging studies reveal that RyR2 cluster sizes span a wide range. The most recent work by Hou et al. (2015) reports many small clusters containing roughly 20–50 channels (spanning approximately 150–250 nm in diameter), while earlier studies by Galice et al. (2018) observed larger aggregates that could extend to several hundred RyR2s, with typical averages closer to 50–100 channels (spanning approximately 250–350 nm in diameter). Although the absolute estimates vary across techniques, the consistent finding is that ventricular myocytes contain a heterogeneous population of clusters, ranging from solitary channels and small groups to large assemblies. The functional behaviour of these clusters is strongly shaped by Ca diffusion in the narrow dyadic cleft. Ca diffuses rapidly in the cytosol, with an effective diffusion coefficient in the range

Since diffusion is much faster than channel gating, we invoke the rapid diffusion approximation, which assumes Ca is uniform within the dyad. Under this approximation, the local Ca concentration is given by

where

To determine the transition rates in our model, we assume first-order kinetics with respect to cytosolic Ca. Specifically, the forward rate for subunit opening is given by

Stochastic simulation algorithm

The Gillespie algorithm is implemented as a stochastic simulation method to model the exact temporal evolution of RyR2 channel gating within clusters (Gillespie, 2007). At each time step, the algorithm calculates the total reaction rate across all subunits in the system based on their current states and local coupling environments. The time to the next reaction is drawn from an exponential distribution with parameter equal to the total rate, ensuring proper stochastic timing. A specific reaction is then selected using weighted random selection proportional to individual subunit rates, after which the chosen subunit transitions between closed and open states. This process continues iteratively, with the system state analyzed after each reaction to count the number of open channels.

Results

Measuring the timing of a spontaneous Ca spark

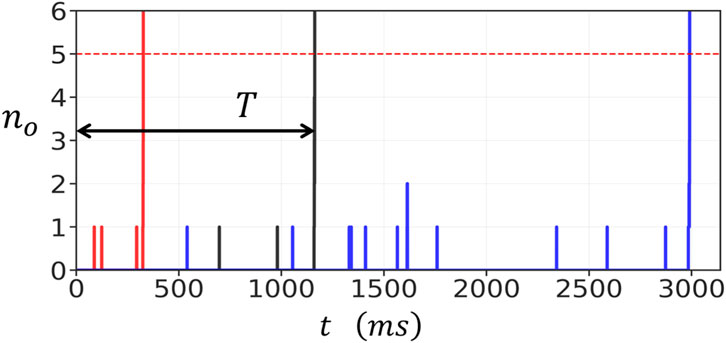

To study the stochastic dynamics of RyR2 clusters, we first simulated the time evolution of a

Figure 2. Stochastic activation of a

The rapid increase in

Control of spontaneous spark timing by diastolic Ca and cluster coupling

We next investigated how the mean waiting time

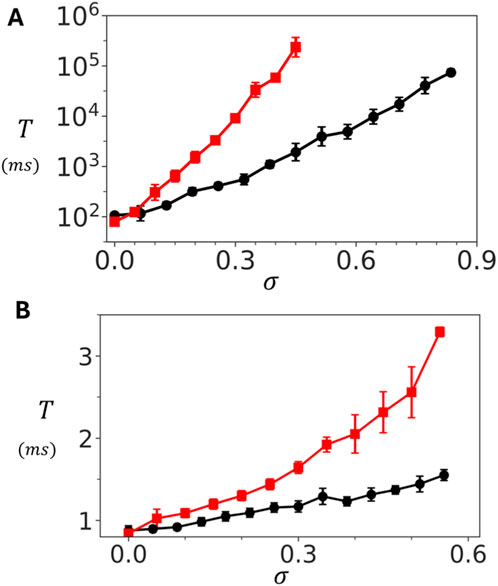

Figure 3. Dependence of spontaneous spark timing on diastolic Ca

To further explore the role of coupling, we examined the dependence of

Figure 4. Dependence of spontaneous Ca spark timing on inter-subunit coupling strength. (A) Dependence of

Modeling heterogeneous clusters

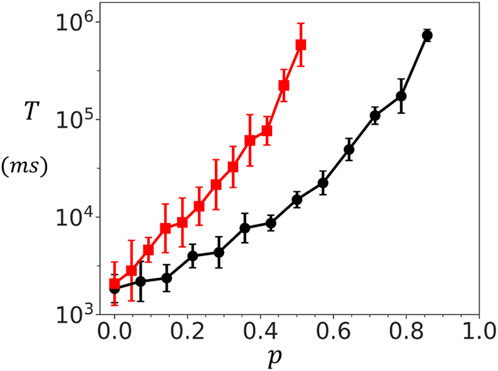

Experimental studies have revealed that RyR2 clusters undergo fractionation and lose their structural integrity in diseased states. To investigate the functional consequences of cluster fractionation, we developed a computational model that simulates the progressive disruption of RyR2 cluster connectivity. Our approach implements stochastic bond breaking between adjacent RyR2 channels within the cluster. Specifically, we assign a probability

Figure 5. Dependence of spontaneous spark timing on cluster connectivity. Mean waiting time

Experimental studies reveal that RyR2 clusters within the junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum exhibit highly heterogeneous spatial arrangements. To investigate how this structural diversity affects functional properties, we have also developed a preferential attachment growth model that generates realistic cluster morphologies. The preferential attachment algorithm sequentially places RyR2 channels on a two-dimensional lattice. For each new channel placement, the probability of selecting an empty site

Figure 6A demonstrates the range of cluster structures generated by varying the clustering parameter

Figure 6. Spark timing in heterogeneous clusters. (A) Representative cluster morphologies generated by varying the clustering parameter

Discussion

Inter-subunit coupling controls cluster response to Ca

In this study, we developed a computational model of an RyR2 cluster in which each channel is composed of four interacting subunits, with channels arranged in a configuration consistent with structures observed in cryo-EM and super-resolution imaging. Our goal was to understand how inter-subunit cooperativity influences Ca leak in cardiac cells. The first result of the model is that the cluster exhibits a sharp contrast in behavior across different Ca concentration regimes. At Ca concentrations larger than

Ca leak is exponentially sensitive to RyR2 cluster integrity

Experimental evidence from cryo-EM and super-resolution microscopy shows that RyR2 clusters in cardiac cells are highly irregular, forming heterogeneous structures rather than perfect lattices. To examine how this heterogeneity shapes Ca signaling, we extended our modeling framework to include disordered cluster geometries and systematically varied their structural integrity. In one approach, we introduced a coupling parameter

Ca leak in heart failure is dependent on RyR2 structural integrity

Recent high-resolution imaging studies have revealed that RyR2 clusters lose their structural integrity in heart failure, with important functional consequences for Ca handling. Sheard et al. (2022) used enhanced expansion microscopy to demonstrate that RyR2 clusters in failing myocytes frequently exhibit a frayed appearance, where small groups of channels detach from the main cluster, particularly in regions depleted of the structural protein junctophilin-2. Similarly, Kolstad et al. (2018) showed that post-infarction heart failure is characterized by RyR2 cluster dispersion and fragmentation, resulting in smaller, more numerous cluster fragments with reduced inter-channel connectivity. Our computational modelling provides a mechanistic explanation for why these structural changes change the Ca leak rate. The key insight from our model is that spontaneous Ca spark frequency exhibits exponential sensitivity to cluster structural integrity. Mechanistically, intact inter-subunit coupling within the cluster provides stabilizing interactions that maintain channels in the closed state during diastole through cooperative inhibition. When coupling is weakened by fragmentation, this stabilizing effect is lost, making the cluster far more susceptible to stochastic activation. The key new insight in this study is that this relationship is exponential, and explains why even modest cluster remodeling, such as partial fragmentation or fraying, can produce the orders of magnitude increases in diastolic Ca leak observed in heart failure. Thus, cluster architectural integrity emerges as a critical control mechanism that drives Ca leak.

The role of diffusion in RyR2 cluster dynamics

Ca diffusion plays a crucial role in determining the functional coupling between RyR2 channels within the dyadic cleft. With a diffusion coefficient of approximately

Cluster integrity as a therapeutic target

The exponential sensitivity of Ca leak to RyR2 coupling revealed in our study carries significant therapeutic implications. Because spark frequency rises exponentially as coupling weakens, even subtle structural disruptions can translate into exponentially large increases in spontaneous Ca release frequency. This nonlinearity also works in the opposite direction, so that modest improvements in cluster integrity could produce dramatic reductions in Ca leak. These results shows that structural stability itself is a valuable therapeutic target. Strategies that preserve or restore RyR2 subunit coupling, such as enhancing the stabilizing action of accessory proteins like FKBP12.6 (Wehrens et al., 2003), offer a direct way to reinforce this stability. Other proteins that regulate RyR2 positioning or inter-channel contacts could likewise be harnessed to maintain cluster integrity (Reynol et al., 2016). Such approaches differ fundamentally from traditional interventions aimed at modifying channel gating kinetics or expression levels, which may have limited efficacy if the underlying cluster architecture remains compromised. By identifying inter-subunit coupling as a central determinant of spontaneous Ca release, our study highlights a specific and tunable structural feature of the RyR2 complex that could be targeted to suppress pathological Ca leak.

Model limitations

Our model has several important limitations. First, we do not incorporate the complex regulatory mechanisms known to modulate RyR2 gating in cardiac myocytes, including inhibition by physiological Mg concentrations and modulation by regulatory proteins such as CaMKII, calmodulin, and FKBP12.6 (Marx and Marks, 2013; Walweel and Laver, 2015; Zahradníková et al., 2025; Rokita and Anderson, 2012). These factors will alter the spark waiting times. However, they are unlikely to eliminate the exponential dependence on cluster connectivity that emerges from cooperative gating between channels. Second, we model RyR2 clusters using idealized geometric arrangements of either pure oblique or pure adjoining configurations, whereas native clusters in cardiac cells exhibit heterogeneous combinations of both interaction types. Our results indicate that mixed geometries will yield intermediate waiting times, with the precise value depending on the relative proportion of each interaction type. However, because both pure configurations exhibit exponential sensitivity to coupling strength and connectivity, we expect this relationship to persist regardless of geometric details. Third, our framework does not include channel inactivation, SR Ca depletion, or competing Ca clearance mechanisms such as the sodium calcium exchanger and the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca ATPase (SERCA). These processes determine spark termination and recovery. However, they occur on timescales much shorter than the diastolic waiting times we investigate and therefore do not affect the spark initiation dynamics that are the focus of this study. While future work incorporating more detailed RyR2 kinetics and realistic cluster geometries will refine quantitative predictions, the central finding that spontaneous Ca spark frequency is exponentially sensitive to cluster structural integrity follows directly from the cooperativity between RyR2 channels and should remain robust.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. YS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Investigation, Software.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (Award Number: 1R16GM153647-01 to YS) and the National Science Foundation (Award Number: 2320846 to YS). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank these agencies for their generous support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI was used to check grammar and sentence construction.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ai X., Curran J. W., Shannon T. R., Bers D. M., Pogwizd S. M. (2005). Ca2+/calmodulin–dependent protein kinase modulates cardiac ryanodine receptor phosphorylation and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in heart failure. Circulation Research 97 (12), 1314–1322. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000194329.41863.89

Asfaw M., Alvarez-Lacalle E., Shiferaw Y. (2013). The timing statistics of spontaneous calcium release in cardiac myocytes. PLoS One 8 (5), e62967. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062967

Baddeley D., Jayasinghe I., Lam L., Rossberger S., Cannell M. B., Soeller C. (2009). Optical single-channel resolution imaging of the ryanodine receptor distribution in rat cardiac myocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106 (52), 22275–22280. doi:10.1073/pnas.0908971106

Benitah J.-P., Perrier R., Mercadier J.-J., Pereira L., Gómez A. M. (2021). RyR2 and calcium release in heart failure. Front. Physiology 12, 734210. doi:10.3389/fphys.2021.734210

Bers D. M. (2002). Cardiac excitation–contraction coupling. Nature 415 (6868), 198–205. doi:10.1038/415198a

Bers D. M., Peskoff A. (1991). Diffusion around a cardiac calcium channel and the role of surface bound calcium. Biophysical Journal 59 (3), 703–721. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82284-6

Cabra V., Murayama T., Samsó M. (2016). Ultrastructural analysis of self-associated RyR2s. Biophysical Journal 110 (12), 2651–2662. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2016.05.013

Cannell M. B., Kong C., Imtiaz M., Laver D. R. (2013). Control of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release by stochastic RyR gating within a 3D model of the cardiac dyad and importance of induction decay for CICR termination. Biophysical Journal 104 (10), 2149–2159. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2013.03.058

Chen-Izu Y., Ward C. W., Stark W., Banyasz T., Sumandea M. P., Balke C. W., et al. (2007). Phosphorylation of RyR2 and shortening of RyR2 cluster spacing in spontaneously hypertensive rat with heart failure. Am. J. Physiology-Heart Circulatory Physiology 293 (4), H2409–H2417. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00562.2007

Dixon R. E. (2022). Nanoscale organization, regulation, and dynamic reorganization of cardiac calcium channels. Front. Physiology 12, 810408. doi:10.3389/fphys.2021.810408

Fowler E. D., Zissimopoulos S. (2022). Molecular, subcellular, and arrhythmogenic mechanisms in genetic RyR2 disease. Biomolecules 12 (8), 1030. doi:10.3390/biom12081030

Galice S., Xie Y., Yang Y., Sato D., Bers D. M. (2018). Size matters: ryanodine receptor cluster size affects arrhythmogenic sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7 (13), e008724. doi:10.1161/JAHA.118.008724

Gao Z.-X., Li T.-T., Jiang H.-Y., He J. (2023). Calcium oscillation on homogeneous and heterogeneous networks of ryanodine receptor. Phys. Rev. E 107 (2), 024402. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.107.024402

Gillespie D. T. (2007). Stochastic simulation of chemical kinetics. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 58 (1), 35–55. doi:10.1146/annurev.physchem.58.032806.104637

Greene D. A., Luchko T., Shiferaw Y. (2023). The role of subunit cooperativity on ryanodine receptor 2 calcium signaling. Biophysical J. 122 (1), 215–229. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2022.11.008

Hiess F., Detampel P., Nolla-Colomer C., Vallmitjana A., Ganguly A., Amrein M., et al. (2018). Dynamic and irregular distribution of RyR2 clusters in the periphery of live ventricular myocytes. Biophysical Journal 114 (2), 343–354. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2017.11.026

Hou Y., Jayasinghe I., Crossman D. J., Baddeley D., Soeller C. (2015). Nanoscale analysis of ryanodine receptor clusters in dyadic couplings of rat cardiac myocytes. J. Molecular Cellular Cardiology 80, 45–55. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.12.013

Hurley M. E., White E., Sheard T. M., Steele D., Jayasinghe I. (2023). Correlative super-resolution analysis of cardiac calcium sparks and their molecular origins in health and disease. Open Biol. 13 (5), 230045. doi:10.1098/rsob.230045

Iaparov B. I., Zahradnik I., Moskvin A. S., Zahradníková A. (2021). In silico simulations reveal that RYR distribution affects the dynamics of calcium release in cardiac myocytes. J. General Physiology 153 (4), e202012685. doi:10.1085/jgp.202012685

Jayasinghe I., Cannell M. B., Soeller C. (2009). Organization of ryanodine receptors, transverse tubules, and sodium-calcium exchanger in rat myocytes. Biophysical J. 97 (10), 2664–2673. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2009.08.036

Kolstad T. R., van den Brink J., MacQuaide N., Lunde P. K., Frisk M., Aronsen J. M., et al. (2018). Ryanodine receptor dispersion disrupts Ca2+ release in failing cardiac myocytes. Elife 7, e39427. doi:10.7554/eLife.39427

Langer G., Peskoff A. (1996). Calcium concentration and movement in the diadic cleft space of the cardiac ventricular cell. Biophysical Journal 70 (3), 1169–1182. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79677-7

Laver D., Baynes T., Dulhunty A. (1997). Magnesium inhibition of ryanodine-receptor calcium channels: evidence for two independent mechanisms. J. Membrane Biology 156 (3), 213–229. doi:10.1007/s002329900202

Li T.-T., Gao Z.-X., Ding Z.-M., Jiang H.-Y., He J. (2025). Formation and regulation of calcium sparks on a nonlinear spatial network of ryanodine receptors. Chaos An Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 35 (2), 023120. doi:10.1063/5.0250817

Macquaide N., Tuan H.-T. M., Hotta J.-i., Sempels W., Lenaerts I., Holemans P., et al. (2015). Ryanodine receptor cluster fragmentation and redistribution in persistent atrial fibrillation enhance calcium release. Cardiovasc. Research 108 (3), 387–398. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvv231

Marx S. O., Marks A. R. (2013). Dysfunctional ryanodine receptors in the heart: new insights into complex cardiovascular diseases. J. Molecular Cellular Cardiology 58, 225–231. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.03.005

Mesa M. H., van den Brink J., Louch W. E., McCabe K. J., Rangamani P. (2022). Nanoscale organization of ryanodine receptor distribution and phosphorylation pattern determines the dynamics of calcium sparks. Biophysical J. 121 (3), 378a. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2021.11.865

Mukherjee S., Thomas N. L., Williams A. J. (2012). A mechanistic description of gating of the human cardiac ryanodine receptor in a regulated minimal environment. J. General Physiology 140 (2), 139–158. doi:10.1085/jgp.201110706

Reynolds J. O., Quick A. P., Wang Q., Beavers D. L., Philippen L. E., Showell J., et al. (2016). Junctophilin-2 gene therapy rescues heart failure by normalizing RyR2-mediated Ca2+ release. Int. Journal Cardiology 225, 371–380. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.10.021

Rokita A. G., Anderson M. E. (2012). New therapeutic targets in cardiology: Arrhythmias and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII). Circulation 126 (17), 2125–2139. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.124990

Sheard T. M., Hurley M. E., Smith A. J., Colyer J., White E., Jayasinghe I. (2022). Three-dimensional visualization of the cardiac ryanodine receptor clusters and the molecular-scale fraying of dyads. Philosophical Trans. R. Soc. B 377 (1864), 20210316. doi:10.1098/rstb.2021.0316

Shen X., van den Brink J., Bergan-Dahl A., Kolstad T. R., Norden E. S., Hou Y., et al. (2022). Prolonged β-adrenergic stimulation disperses ryanodine receptor clusters in cardiomyocytes and has implications for heart failure. Elife 11, e77725. doi:10.7554/eLife.77725

Soeller C., Jayasinghe I. D. (2018). “Quantitative super-resolution microscopy of cardiomyocytes,” in Microscopy of the heart (Springer), 37–73.

Swietach P., Spitzer K. W., Vaughan-Jones R. D. (2010). Modeling calcium waves in cardiac myocytes: importance of calcium diffusion. Front. Bioscience (Landmark Edition) 15, 661–680. doi:10.2741/3639

Waddell H. M., Mereacre V., Alvarado F. J., Munro M. L. (2023). Clustering properties of the cardiac ryanodine receptor in health and heart failure. J. Molecular Cellular Cardiology 185, 38–49. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2023.10.012

Walweel K., Laver D. (2015). Mechanisms of SR calcium release in healthy and failing human hearts. Biophys. Reviews 7 (1), 33–41. doi:10.1007/s12551-014-0152-4

Wehrens X. H., Lehnart S. E., Huang F., Vest J. A., Reiken S. R., Mohler P. J., et al. (2003). FKBP12. 6 deficiency and defective calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) function linked to exercise-induced sudden cardiac death. Cell 113 (7), 829–840. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00434-3

Woll K. A., Van Petegem F. (2022). Calcium-release channels: structure and function of IP3 receptors and ryanodine receptors. Physiol. Rev. 102 (1), 209–268. doi:10.1152/physrev.00033.2020

Xu L., Meissner G. (2004). Mechanism of calmodulin inhibition of cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor). Biophysical Journal 86 (2), 797–804. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74155-7

Keywords: RyR2, calcium release channel, cardiac arhythmias, channel cluster, spontaneous release

Citation: Noren A and Shiferaw Y (2025) Structural integrity of RyR2 clusters controls cardiac calcium leak. Front. Physiol. 16:1731863. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2025.1731863

Received: 24 October 2025; Accepted: 25 November 2025;

Published: 09 December 2025.

Edited by:

Sean Michael Wilson, Loma Linda University, United StatesReviewed by:

D. George Stephenson, La Trobe University, AustraliaJun He, Nanjing Normal University, China

Copyright © 2025 Noren and Shiferaw. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yohannes Shiferaw, eXNoaWZlcmF3QGNzdW4uZWR1

Andrew Noren

Andrew Noren Yohannes Shiferaw

Yohannes Shiferaw