- School of Educational Science, Jiangsu Second Normal University, Nanjing, China

Purpose: To investigate the effects of different dosages of exercise on anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents.

Methods: The present study screened randomized controlled trials (RCTs) from PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and Cochrane Library databases. According to the suggestions of American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM), all included studies were categorised into a high and a low/uncertain adherence group. The random-effects model was adopted in the meta-analysis. Subgroup analyses were also conducted to explore the differences in outcomes.

Results: A total of 27 RCTs including 2022 participants were extracted and included for analysis. The results indicated that exercise interventions may have an anxiolytic effect in youth (SMD = −0.36, 95% CI: −0.58 to −0.15, p = 0.0009). According to the ACSM, 13 studies were classified into high adherence group, and 14 studies were classified into low/uncertain adherence group. Subgroup analysis showed that the anxiety reduction was significantly larger in high ACSM adherence group (SMD = −0.67, 95% CI: −1.10 to −0.23, p = 0.002) than in low/uncertain ACSM adherence group (SMD = −0.13, 95% CI: −0.33 to 0.07, p = 0.21). Furthermore, exercise interventions longer than 11 weeks showed significantly greater effects than those shorter than 11 weeks. Only interventions delivered at least three times per week and incorporating combined exercise modalities exerted anxiolytic effects. Moreover, exercise interventions significantly reduced anxiety symptoms in populations with physical illnesses.

Conclusion: The meta-analysis demonstrated that exercise interventions showed significant anxiolytic effects in children and adolescents. Moreover, the anxiety reduction in the high ACSM adherence group was significantly larger than that in the low/uncertain ACSM adherence group.

1 Introduction

Anxiety is an emotion featuring the dimensions of apprehension and somatic symptoms of tension (American Psychological Association, 2025). In terms of prevalence, anxiety is a frequently encountered mental health problem which tends to correlate with lower academic performance (Mazzone et al., 2007), diminished quality of life and social functioning among younger populations (Haller et al., 2014; Leichsenring and Leweke, 2017). In our review, the age of children and adolescents was set at 6–18 years old, according to the World Health Organization (2020). Therefore, anxiety should be identified early and promptly treated in this age group (Asselmann and Beesdo-Baum, 2015; Hill et al., 2016).

Currently, mainstream interventions for anxiety include psychological therapy and pharmacotherapy (Craske and Stein, 2016). As cognitive behavioral therapy, a commonly used form of psychological therapy, has several limitations such as high cost of treatment (Marciniak et al., 2005) and long waiting time before treatment (Chartier-Otis et al., 2010). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are the mainstay in pharmacotherapy, which are often linked to a variety of adverse effects including metabolic effects, dependence and withdrawal reactions (Baldwin et al., 2005; Taylor et al., 2012; Bandelow et al., 2015). In addition, the social stigma of both psychological and pharmacological treatments are often responsible for deterring individuals from seeking help (Curcio and Corboy, 2020).

Due to the limitations of mainstream treatments for anxiety, exercise has gradually attracted attention as an intervention with no social stigma and low cost (Pascoe et al., 2020). A meta-analysis showed that interventions involving exercise significantly reduce anxiety in college students, and aerobic exercise has the greatest effect (Lin and Gao, 2023). Other meta-analyses also explored whether mind–body exercise could decrease anxiety levels in different populations (So et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2024). When exploring exercise’s anxiolytic effects in patients with clinical anxiety, it was found that aerobic exercise markedly reduced anxiety levels, and the programs of higher intensity outperformed those of lower intensity (Aylett et al., 2018). As for intervention involving exercise in adolescents, there were two meta-analyses. The study found that exercise moderately reduces anxiety in the population (Carter et al., 2021), while the other one found that resistance training reduces anxiety in adolescents (Marinelli et al., 2024). The previous meta-analyses have extended the age limit to 25–26 years (Carter et al., 2021; Marinelli et al., 2024), which may consequently obscure developmental heterogeneity and make inferences under children and adolescents. Further, in the absence of evidence-based exercise dose framework, it is not clear how the exercise dose is related to alleviation of anxiety in this population.

To address these gaps, we conducted a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials involving participants that are under the age of 18 years and the exercise dose is categorized according to the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) guidelines (Garber et al., 2011). Furthermore, based on the suggestions of the ACSM, we divided the included studies into a high and a low/uncertain adherence group and compared their respective effects on anxiety in children and adolescents. This study explores how different exercise dosages impact anxiety symptoms, thereby supplying critical evidence to inform the development of exercise intervention approaches in diminishing anxiety among children and adolescents.

2 Methods

This meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and has been registered in PROSPERO (CRD420251175738).

2.1 Search strategy

PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and Cochrane databases were searched from inception to 30 August 2025 without language limits. The strategy was constructed according to the PICOS format and included four concept blocks connected with the Boolean operator AND: (1) population (children OR adolescents), (2) intervention (exercise OR physical activity OR sport), (3) outcome (anxiety OR anxiety disorder), and (4) study design (randomized OR randomized controlled trial OR RCT). MeSH and free-text terms were employed; the synonyms that comprise each block will be joined with the operator OR. The full search strategy is given in Supplementary Appendix S1.

2.2 Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria: (1) individuals under the age of 18; (2) an experimental group engaging in any form of exercise; (3) a control condition that included waitlist, no treatment, control group with no exercise intervention, and treatment (physical activity) as usual; (4) anxiety symptoms assessed with validated and standardised psychological scales; (5) randomized controlled trial (RCT) design, including cluster RCTs; and (6) no language restriction.

Exclusion criteria: (1) individuals aged over 18 years; (2) non-randomized controlled trials (non-RCTs); (3) studies lacking available data on outcome indicators; and (4) unpublished or grey literature.

Two researchers independently screened studies by reviewing titles and abstracts. Subsequently, full texts were assessed to establish their eligibility to be included in the meta-analysis. Disagreement was solved by discussion.

2.3 Data synthesis and analysis

Two researchers independently extracted information from included studies based on specific inclusion criteria. First author, country, health status, age, sample, type of intervention, control condition, and outcome measures were extracted. After the extraction of the data, the extent of exercise dose and adherence were rated individually by each researcher and the intervention elements were coded based on the ACSM domains (cardiorespiratory, resistance, and flexibility exercise) (Garber et al., 2011). Interventions expressly recommending two or more ACSM domains were categorized as combined exercise and further sub-categorized into cardiorespiratory-flexibility, resistance-flexibility, cardiorespiratory-resistance, and all three components; disagreements were resolved through discussion. In line with previous meta-analyses (Fang et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2024), we scored the compliance of each RCT on a 0–2 scale for frequency, intensity/workload and duration of cardiorespiratory, resistance and flexibility exercises (2 = completely compliant, 1 = uncertain, 0 = non-compliant). The proportion of exercise doses meeting ACSM recommendations was then calculated for each study. Studies achieving adherence rates of ≥75% to the ACSM-recommended doses were categorized as high adherence, while those with rates <75% were classified as low/uncertain adherence (Table 1).

2.4 Statistical analysis

Multi-arm trials were narrowed to one arm of the single exercise meeting the ACSM dose to prevent a possibility of duplicating the shared control group, and yield one contrast of intervention versus control. The scores of anxiety measured post-intervention were also extracted and then analysed using Review Manager 5.4. The effect size was expressed as SMD, with its 95% confidence interval (CI). According to the ACSM compliance criteria, studies included in this analysis were divided into a high adherence group (compliance rate ≥75%) and a low/uncertain adherence group (compliance rate <75%). Given heterogeneity in the characteristics of exercise interventions, which include length, frequency, and duration, a random-effects model was used in the meta-analysis. To assess potential publication bias, funnel plots were constructed, and Begg’s rank correlation test and Egger’s linear regression test were performed to evaluate the symmetry of the funnel plots.

2.5 Quality appraisal

Following the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins et al., 2011), two researchers conducted independent assessments of the risk of bias (ROB) across random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other bias, each of which was categorized into low, unclear, and high risk.

3 Results

3.1 Selection results

The study selection process was shown in Figure 1, a total of 5,386 articles were retrieved from PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and Cochrane Library databases. After removing duplicate records, 4,316 studies remained. 109 articles were selected for further evaluation following the screening of titles and abstracts. After reviewing the full texts, 27 studies were included in the meta-analysis.

3.2 Study characteristics

This study included 27 randomized controlled trials with 2022 participants: 1,083 in experimental groups and 939 in control groups (Table 2). Regarding participant characteristics, 12 studies involved healthy populations, 8 studies focused on participants diagnosed with physical illnesses (i.e., obesity, type 1 diabetes, and irritable bowel syndrome), and 7 studies targeted individuals with mental illnesses (i.e., anorexia nervosa, ADHD, depression, and autism spectrum disorder). All included studies employed exercise interventions: 6 cardiorespiratory, 10 flexibility, and 11 combined exercise (cardiorespiratory-resistance n = 2; cardiorespiratory-flexibility n = 2; resistance-flexibility n = 1; all three components n = 6). Ranging from 3 to 24 weeks, the interventions were conducted 1 to 7 times weekly, with each session lasting 10–90 min. As for the control group conditions: 9 studies involved a no intervention control, 5 studies used a waitlist control, 7 studies employed non-exercise interventions, and 6 studies implemented treatment as usual. In addition, only four of the 27 RCTs assessed cortisol (Nazari et al., 2020; Rodrigues et al., 2021; Gehricke et al., 2022; Heidarianpour et al., 2023), with a significant post-intervention reduction reported in one study (Heidarianpour et al., 2023).

3.3 Risk of bias

Concerning generation of random sequences, 16 studies that clearly described the methods were classified as low risk. The remaining 11 only mentioned randomization without specifying the method, hence were rated unclear risk. Three studies that explicitly described the allocation concealment method were deemed low risk; the rest that lacked relevant details were deemed unclear risk. Considering that exercise interventions possess specific features, blinding participants and personnel was infeasible, thus all studies were rated high risk. Six studies specifically reported implementing blinding of outcome assessment and were deemed low risk, and the rest were deemed unclear risk. 19 studies provided adequate descriptions of incomplete outcome data and were categorized as low risk, and the remaining ones were deemed unclear risk. Regarding selective reporting, all studies were classified as low risk. Three studies were deemed unclear risk regarding other bias, and the others rated low risk (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Results of cochrane risk of bias tool. Combined percentage risk of bias in each risk domain for all included trials (top).Risk of bias summaries for all exercise trials (bottom).

3.4 Compliance with the ACSM recommendations

In accordance with ACSM guidelines, 13 studies demonstrated an exercise adherence rate of ≥75%, meeting the criteria for high adherence, while 14 studies had an adherence rate of <75%, which were classified as low or uncertain adherence (Table 3). This discrepancy was primarily due to either a lack of detailed descriptions regarding the exercise dosage or the use of parameters that did not align with the ACSM guidelines.

3.5 Meta-analysis

Figure 3 shows that exercise interventions may may reduce anxiety in youth (SMD = −0.36, 95% CI: −0.58 to −0.15, p = 0.0009, I2 = 79%). To identify potential effect modifiers, we fitted meta-regression on baseline anxiety score, mean age and proportion of boys. None of the covariates significantly predicted between-study heterogeneity: baseline anxiety (β = −0.005, 95% CI: −0.019 to 0.01, p = 0.532), mean age (β = 0.021, 95% CI: −0.077 to 0.12, p = 0.67) or proportion of boys (β = 1.059, 95% CI: −0.105 to 2.223, p = 0.075) (Supplementary Appendix S2).

Subgroup analysis revealed that anxiety reduction was significantly larger in high ACSM adherence group (SMD = −0.67, 95% CI: −1.10 to −0.23, p = 0.002. I2 = 84%) than in low/uncertain ACSM adherence group (SMD = −0.13, 95% CI: −0.33 to 0.07, p = 0.21, I2 = 64%) (Figure 4). Sensitivity analyses at 70% and 60% ACSM-adherence thresholds (two additional subgroup analyses) produced directionally consistent pooled estimates favouring exercise, while the between-subgroup interaction was significant at 70% (p = 0.03) but not at 60% (p = 0.11), indicating that the anxiolytic advantage is confined to trials achieving ≥70% compliance with ACSM guidelines and supporting the 75% threshold used in the primary analysis (Supplementary Appendixs S3, S4).

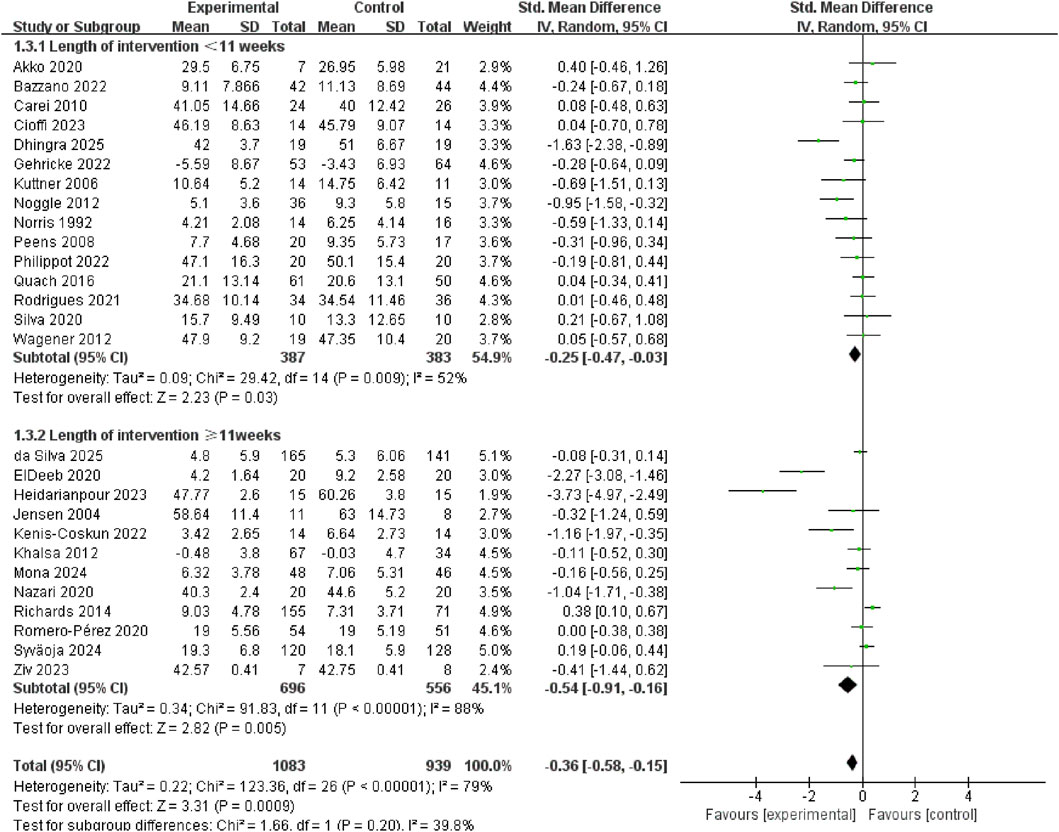

Exercise interventions longer than 11 weeks (SMD = −0.54, 95% CI: −0.91 to −0.16, p = 0.005, I2 = 88%) exerted greater anxiolytic effects in youth than interventions shorter than 11 weeks (SMD = −0.25, 95% CI: −0.47 to −0.03, p = 0.03, I2 = 52%) (Figure 5).

Compared with interventions conducted less than 3 times/week (SMD = −0.10, 95% CI: −0.26 to 0.05, p = 0.20, I2 = 41%), those conducted at least 3 times/week (SMD = −0.76, 95% CI: −1.28 to −0.25, p = 0.004, I2 = 88%) showed significantly greater anxiolytic effects in youth (Figure 6).

Exercise modalities were classified as cardiorespiratory, flexibility or combined exercise. Compared with cardiorespiratory exercise (SMD = 0.05, 95% CI: −0.28 to 0.38, p = 0.78, I2 = 44%) and flexibility exercise (SMD = −0.18, 95% CI: −0.36 to −0.00, p = 0.05, I2 = 14%), combined exercise modalities produced larger anxiolytic effects in children and adolescents (SMD = −0.76, 95% CI: −1.20 to −0.32, p = 0.0008, I2 = 89%) (Figure 7).

To identify which specific combination of exercise components drives the anxiolytic benefit, we performed a subgroup analysis of the four subtypes of the combined exercise. The results revealed that significant reductions in anxiety were confined to resistance-flexibility (SMD = −2.27, 95% CI: −3.08 to −1.46, p < 0.00001) and all three components (SMD = −0.63, 95% CI: −1.16 to −0.11, p = 0.02, I2 = 87%). In contrast, cardiorespiratory-resistance (SMD= −0.39, 95% CI: −1.59 to 0.82, p = 0.53, I2 = 91%) and cardiorespiratory-flexibility (SMD = −0.73, 95% CI: −2.53 to 1.07, p = 0.43, I2 = 90%) did not reach statistical significance (Figure 8). Sensitivity analysis showed the pooled effect remained significant and directionally consistent after sequentially removing any single study (Supplementary Appendix S5).

Exercise significantly reduced anxiety symptoms in populations with physical illnesses (SMD = −1.05, 95% CI: −1.75 to −0.35, p = 0.003, I2 = 88%); no significant anxiolytic effects were observed in healthy populations (SMD = −0.04, 95% CI: −0.22 to 0.13, p = 0.64, I2 = 54%) or in individuals with mental illnesses (SMD = −0.35, 95% CI: −0.76 to 0.06, p = 0.09, I2 = 61%) (Figure 9).

Egger’s test and Begg’s test (p < 0.01) detected the publication bias, however, this bias did not affect the overall results showed by trim-and-fill analysis (Figure 10).

4 Discussion

This meta-analysis demonstrated that exercise interventions showed significant anxiolytic effects in children and adolescents. Moreover, the anxiety reduction was significantly larger in high ACSM adherence group compared with that in low/uncertain ACSM adherence group. Additionally, interventions lasting longer than 11 weeks were more effective than those of shorter length. Only exercise performed more than three times per week and combined exercise modalities exerted significant anxiolytic effects. Furthermore, exercise interventions were found to significantly reduce anxiety symptoms among individuals with physical illnesses.

Exercise significantly reduced anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents, consistent with meta-analyses in young adults (Carter et al., 2021; Marinelli et al., 2024). In our review, 4 of the 27 trials performed the measurement of cortisol, and only one of them found significant post-intervention reduction (Heidarianpour et al., 2023). Previous studies indicate that exercise can suppress hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis hyperactivity and regulate the release of neurotransmitters which could be translated into reduced anxiety symptoms (Fichter and Pirke, 1986; Anderson & Shivakumar, 2013; Mikkelsen et al., 2017). These mechanisms are theoretical and were not directly examined in the trials we included. Exercise may also enhance self-efficacy and improve psychological adaptation (Bodin and Martinsen, 2004). By repeatedly experiencing the sensations of fear or worry, individuals increase their familiarization with these feelings, which produces a habituation response, a mechanism similar to that underlying exposure therapy for clinical anxiety disorders (Broman-Fulks et al., 2004; Parker et al., 2018). This hypothesis remains to be further verified.

According to the ACSM guidelines, we categorized the selected studies into high and low/uncertain adherence groups (Garber et al., 2011). In line with previous studies, our two groups contained similar exercise modalities in this meta-analysis (Cui et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2024). This analytical approach reduced the possible confounding effect caused by primary exercise modalities of ACSM compliance. A previous meta-analysis suggested that high ACSM-compliant exercise can alleviate depression in hemodialysis patients (Fang et al., 2024). Our result also indicated that exercise intervention that follows ACSM-recommended dosage can bring a significantly positive effect on reducing anxiety among children and adolescents. Therefore, in the future exercise intervention studies should follow ACSM-recommended dosage to report parameters and increase the consistency and comparability among studies.

Exercise length, frequency and modality may also influence the anxiolytic effects of physical exercise in children and adolescents. In terms of exercise length, our results demonstrated that both shorter (<11 weeks) and longer (≥11 weeks) interventions significantly alleviated anxiety symptoms in youth, and longer interventions showed better effects. In terms of exercise frequency, only the exercise interventions conducted more than 3 times per week could significantly reduce anxiety symptoms. Previous studies also indicated that different doses of exercise would exert different anxiolytic effects on college students (Ji et al., 2022; Margulis et al., 2023). Only interventions conducted longer than 8 weeks and more than 3 times/week would exert anxiolytic effects on college students (Lin and Gao, 2023). In terms of exercise modalities, the combined exercise modalities showed more anxiolytic effects. Previous study found that different exercise modalities would produce distinct effects on anxiety among adults (LeBouthillier and Asmundson, 2017). Specifically, aerobic training would reduce the psychological distress and anxiety level, while resistance exercise would heighten the sensitivity to anxiety symptoms and improve the tolerance of psychological distress (LeBouthillier and Asmundson, 2017). By integrating physical activity with mental concentration and relaxation practice, yoga and qigong would also reduce anxiety (Li et al., 2020). Moreover, significant anxiolytic effects were only observed in resistance-flexibility (one study) and all three components (cardiorespiratory, resistance, and flexibility) exercise. Neither cardiorespiratory-flexibility nor the widely advocated cardiorespiratory-resistance was found to be statistically significant, though each of the estimates was based on less than three trials and should be regarded as being preliminary. The superior efficacy of all three components (cardiorespiratory, resistance, and flexibility) exercise may reflect additive psychophysiological adaptations, enhanced parasympathetic modulation and self-efficacy. However, the limited data for any two-component combination prevents a conclusive ranking. Future studies should compare the effects of different combined exercise protocols on anxiety in children and adolescents.

Consistent with previous studies (Long and Vanstavel, 1995; Carter et al., 2021), our meta-analysis found that exercise can decrease anxiety symptoms among patients with physical illnesses. Cortisol data extracted from the eligible trials suggest that in obese girls with central precocious puberty, exercise reduced body fat and produced a sustained cortisol reduction that accompanied lower anxiety scores, indicating reversal of obesity driven HPA axis overactivity (Heidarianpour et al., 2023). In contrast, a similar psychological benefit was achieved in youths with type 1 diabetes without any additional decrease in cortisol (Nazari et al., 2020), which suggests regulation of glycaemic and autonomic systems, but not glucocorticoid inhibition. Future RCTs should combine anxiety measurements with biomarkers to elucidate these conflicting directions and prescription of precision exercises in pediatric endocrine and obesity clinics. Exercise did not significantly reduce anxiety in healthy youth or in those with mental illnesses. The failure to detect an anxiolytic effect should be interpreted cautiously. First, the scales used in most trials were developed to screen rather than to detect subtle changes, so they may lack the sensitivity needed for participants with low levels (Quach et al., 2016; Aumer and Vögele, 2025). Second, because of small samples and low event rates, the meta-analysis had insufficient power to detect small-to-moderate effects. Third, baseline heterogeneity may have obscured true effects. Healthy youth frequently presented a floor effect (Ensari et al., 2015), but those with mental illness exhibited more dispersion as a baseline which may have resulted into the underestimation of the actual effect. Thus, the absence of a significant effect in these subgroups reflects methodological constraints rather than definitive inefficacy.

There are several limitations. First, the included studies exhibited considerable heterogeneity, and the exercise dosage was not properly reported. The lack of clear definitions may have compromised the accuracy of adherence classification against ACSM guidelines. Second, because exercise interventions have unique characteristics, participant blinding was impossible, potentially biasing the results. Third, most studies assessed anxiety symptoms with self-report questionnaires, which are susceptible to both adolescent cognitive development and social-desirability bias. Fourth, objective anxiety-related biomarkers were rarely collected, which limited insight into underlying mechanisms. Fifth, insufficient detail on group separation and limited monitoring of intervention fidelity in school-based cluster trials raise the possibility of between-group contamination. Finally, the absence of uniform diagnostic criteria for anxiety, whether based on symptom cut-offs, screening questionnaires or clinician diagnosis, which limits the generalizability and cross-study comparability of findings.

Despite these limitations, this study nonetheless provides valuable implications for clinical practice. This meta-analysis not only reveals that exercise dosage is an important component of treating anxiety in children and adolescents but also facilitates the development of standardized exercise prescriptions in pediatrics, child psychiatry, and child rehabilitation. In addition, the results support using combined physical and psychological interventions for managing chronic illness in youth and using exercise-based therapy as a supportive treatment for common mental disorders.

5 Conclusion

This meta-analysis demonstrates that exercise interventions produce significant anxiolytic effects in children and adolescents, with larger benefits when programmes closely adhere to ACSM guidelines. Specifically, interventions lasting more than 11 weeks, delivered at least three times per week, and combined exercise modalities yield greater anxiety reduction, underscoring prescriptions readily applicable in school physical education or paediatric mental healthcare. Nevertheless, marked methodological heterogeneity and incomplete reporting of frequency, intensity, time and type hinder precise dose determination and restrict the certainty of any dose–response conclusion. Future research should adopt a standardized framework and explicit reporting standards to establish the optimal anxiolytic exercise dose.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JX: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. QH: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Validation, Writing – review and editing. BJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by the Jiangsu Provincial Educational Science Planning Project (C/2023/01/51).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2025.1744254/full#supplementary-material

References

Akko D. P., Koutsandréou F., Murillo-Rodríguez E., Wegner M., Budde H. (2020). The effects of an exercise training on steroid hormones in preadolescent children - a moderator for enhanced cognition? Physiol. Behav. 227, 113168. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.113168

American Psychological Association (2025). Anxiety. Available online at: https://www.apa.org/topics/anxiety (Accessed, 2025).

Anderson E., Shivakumar G. (2013). Effects of exercise and physical activity on anxiety. Front. Psychiatry 4, 27. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00027

Asselmann E., Beesdo-Baum K. (2015). Predictors of the course of anxiety disorders in adolescents and young adults. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 17 (2), 7. doi:10.1007/s11920-014-0543-z

Aumer T., Vögele C. (2025). Anxiety reducing effects of physical activity in adolescents and young adults revisiting the evidence. Eur. J. Health Psychol. 32 (2), 102–119. doi:10.1027/2512-8442/a000168

Aylett E., Small N., Bower P. (2018). Exercise in the treatment of clinical anxiety in general practice - a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 18 (1), 559. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3313-5

Baldwin D. S., Anderson I. M., Nutt D. J., Bandelow B., Bond A., Davidson J. R. T., et al. (2005). Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders: recommendations from the British association for psychopharmacology. J. Psychopharmacol. 19 (6), 567–596. doi:10.1177/0269881105059253

Bandelow B., Reitt M., Roever C., Michaelis S., Goerlich Y., Wedekind D. (2015). Efficacy of treatments for anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 30 (4), 183–192. doi:10.1097/yic.0000000000000078

Bazzano A. N., Sun Y., Chavez-Gray V., Akintimehin T., Gustat J., Barrera D., et al. (2022). Effect of yoga and mindfulness intervention on symptoms of anxiety and depression in young adolescents attending middle school: a pragmatic community-based cluster randomized controlled trial in a racially diverse urban setting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 (19), 12076. doi:10.3390/ijerph191912076

Bodin T., Martinsen E. W. (2004). Mood and self-efficacy during acute exercise in clinical depression. A randomized, controlled study. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 26 (4), 623–633. doi:10.1123/jsep.26.4.623

Broman-Fulks J. J., Berman M. E., Rabian B. A., Webster M. J. (2004). Effects of aerobic exercise on anxiety sensitivity. Behav. Res. Ther. 42 (2), 125–136. doi:10.1016/s0005-7967(03)00103-7

Carei T. R., Fyfe-Johnson A. L., Breuner C. C., Brown M. A. (2010). Randomized controlled clinical trial of yoga in the treatment of eating disorders. J. Adolesc. Health 46 (4), 346–351. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.007

Carter T., Pascoe M., Bastounis A., Morres I. D., Callaghan P., Parker A. G. (2021). The effect of physical activity on anxiety in children and young people: a systematic review and Meta -analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 285, 10–21. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.026

Chartier-Otis M., Perreault M., Belanger C. (2010). Determinants of barriers to treatment for anxiety disorders. Psychiatr. Q. 81 (2), 127–138. doi:10.1007/s11126-010-9123-5

Cioffi R., Lubetzky A. V. (2023). BOXVR versus guided YouTube boxing for stress, anxiety, and cognitive performance in adolescents: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Games Health J. 12 (3), 259–268. doi:10.1089/g4h.2022.0202

Craske M. G., Stein M. B. (2016). Anxiety. Lancet 388 (10063), 3048–3059. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)30381-6

Cui W., Li D., Jiang Y., Gao Y. (2023). Effects of exercise based on ACSM recommendations on bone mineral density in individuals with osteoporosis: a systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Front. Physiol. 14, 1181327. doi:10.3389/fphys.2023.1181327

Curcio C., Corboy D. (2020). Stigma and anxiety disorders: a systematic review. Stigma Health 5 (2), 125–137. doi:10.1037/sah0000183

da Silva J. M., Castilho Dos Santos G., de Oliveira Barbosa R., de Souza Silva T. M., Correa R. C., da Costa B. G. G., et al. (2025). Effects of a school-based physical activity intervention on mental health indicators in a sample of Brazilian adolescents: a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 25 (1), 539. doi:10.1186/s12889-025-21620-y

Dhingra A., Gupta A., Aditi (2025). Effect of aerobic training on anxiety, activities of daily living and visual motor skills performance in children with autism: a randomised controlled trial. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 19 (2), SC06–SC11. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2025/73346.20624

ElDeeb A. M., Atta H. K., Osman D. A. (2020). Effect of whole body vibration versus resistive exercise on premenstrual symptoms in adolescents with premenstrual syndrome. Bull. Fac. Phys. Ther. 25 (1), 1–6. doi:10.1186/s43161-020-00002-y

Ensari I., Greenlee T. A., Motl R. W., Petruzzello S. J. (2015). Meta-analysis of acute exercise effects on state anxiety: an update of randomized controlled trials over the past 25 years. Depress. Anxiety 32 (8), 624–634. doi:10.1002/da.22370

Fang Y., Xiaoling B., Huan L., Yaping G., Binying Z., Man W., et al. (2024). Effects of exercise dose based on the ACSM recommendations on depression in hemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Physiol. 15, 1513746. doi:10.3389/fphys.2024.1513746

Fichter M. M., Pirke K. M. (1986). Effect of experimental and pathological weight loss upon the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 11 (3), 295–305. doi:10.1016/0306-4530(86)90015-6

Garber C. E., Blissmer B., Deschenes M. R., Franklin B. A., Lamonte M. J., Lee I. M., et al. (2011). Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 43 (7), 1334–1359. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb

Gehricke J. G., Lowery L. A., Alejo S. D., Dawson M., Chan J., Parker R. A., et al. (2022). The effects of a physical exercise program, LEGOR and minecraft activities on anxiety in underserved children with autism spectrum disorder. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 97, 102005. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2022.102005

Haller H., Cramer H., Lauche R., Gass F., Dobos G. J. (2014). The prevalence and burden of subthreshold generalized anxiety disorder: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 14, 128. doi:10.1186/1471-244x-14-128

Heidarianpour A., Shokri E., Sadeghian E., Cheraghi F., Razavi Z. (2023). Combined training in addition to cortisol reduction can improve the mental health of girls with precocious puberty and obesity. Front. Pediatr. 11, 1241744. doi:10.3389/fped.2023.1241744

Higgins J. P. T., Altman D. G., Gotzsche P. C., Juni P., Moher D., Oxman A. D., et al. (2011). The cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ-British Med. J. 343, d5928. doi:10.1136/bmj.d5928

Hill C., Waite P., Creswell C. (2016). Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Paediatr. Child. Health 26 (12), 548–553. doi:10.1016/j.paed.2016.08.007

Jensen P. S., Kenny D. T. (2004). The effects of yoga on the attention and behavior of boys with Attention-Deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). J. Atten. Disord. 7 (4), 205–216. doi:10.1177/108705470400700403

Ji C. X., Yang J., Lin L., Chen S. (2022). Physical exercise ameliorates anxiety, depression and sleep quality in college students: experimental evidence from exercise intensity and frequency. Behav. Sci. 12 (3), 61. doi:10.3390/bs12030061

Kenis-Coskun Ö., Aksoy A. N., Kumaş E. N., Yılmaz A., Güven E., Ayaz H. H., et al. (2022). The effect of telerehabilitation on quality of life, anxiety, and depression in children with cystic fibrosis and caregivers: a single-blind randomized trial. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 57 (5), 1262–1271. doi:10.1002/ppul.25860

Khalsa S. B., Hickey-Schultz L., Cohen D., Steiner N., Cope S. (2012). Evaluation of the mental health benefits of yoga in a secondary school: a preliminary randomized controlled trial. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 39 (1), 80–90. doi:10.1007/s11414-011-9249-8

Kuttner L., Chambers C. T., Hardial J., Israel D. M., Jacobson K., Evans K. (2006). A randomized trial of yoga for adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome. Pain Res. Manag. 11 (4), 217–223. doi:10.1155/2006/731628

LeBouthillier D. M., Asmundson G. J. G. (2017). The efficacy of aerobic exercise and resistance training as transdiagnostic interventions for anxiety-related disorders and constructs: a randomized controlled trial. J. Anxiety Disord. 52, 43–52. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.09.005

Leichsenring F., Leweke F. (2017). Social anxiety disorder. N. Engl. J. Med. 376 (23), 2255–2264. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1614701

Li Z. M., Liu S. J., Wang L., Smith L. (2020). Mind-body exercise for anxiety and depression in COPD patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 (1), 22. doi:10.3390/ijerph17010022

Lin Y. R., Gao W. (2023). The effects of physical exercise on anxiety symptoms of college students: a meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 14, 1136900. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1136900

Lin X., Zheng J. X., Zhang Q., Li Y. F. (2024). The effects of mind body exercise on anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 26, 100587. doi:10.1016/j.mhpa.2024.100587

Long B. C., Vanstavel R. (1995). Effects of exercise training on anxiety: a meta-analysis. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 7 (2), 167–189. doi:10.1080/10413209508406963

Marciniak M. D., Lage M. J., Dunayevich E., Russell J. M., Bowman L., Landbloom R. P., et al. (2005). The cost of treating anxiety: the medical and demographic correlates that impact total medical costs. Depress. Anxiety 21 (4), 178–184. doi:10.1002/da.20074

Margulis A., Andrews K., He Z. H., Chen W. Y. (2023). The effects of different types of physical activities on stress and anxiety in college students. Curr. Psychol. 42 (7), 5385–5391. doi:10.1007/s12144-021-01881-7

Marinelli R., Parker A. G., Levinger I., Bourke M., Patten R., Woessner M. N. (2024). Resistance training and combined resistance and aerobic training as a treatment of depression and anxiety symptoms in young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Early Interv. Psychiatry 18 (8), 585–598. doi:10.1111/eip.13528

Mazzone L., Ducci F., Scoto M. C., Passaniti E., D'Arrigo V. G., Vitiello B. (2007). The role of anxiety symptoms in school performance in a community sample of children and adolescents. BMC Public Health 7, 347. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-347

Mikkelsen K., Stojanovska L., Polenakovic M., Bosevski M., Apostolopoulos V. (2017). Exercise and mental health. Maturitas 106, 48–56. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.09.003

Mona M., Kumari S., Anand N., Sharma M. (2024). Safe use of screen time among adolescents: a randomized controlled study of the efficacy of yoga. Cureus 16 (10), e71335. doi:10.7759/cureus.71335

Nazari M., Shabani R., Dalili S. (2020). The effect of concurrent resistance-aerobic training on serum cortisol level, anxiety, and quality of life in pediatric type 1 diabetes. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 33 (5), 599–604. doi:10.1515/jpem-2019-0526

Noggle J. J., Steiner N. J., Minami T., Khalsa S. B. (2012). Benefits of yoga for psychosocial well-being in a US high school curriculum: a preliminary randomized controlled trial. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 33 (3), 193–201. doi:10.1097/DBP.0b013e31824afdc4

Norris R., Carroll D., Cochrane R. (1992). The effects of physical activity and exercise training on psychological stress and well-being in an adolescent population. J. Psychosom. Res. 36 (1), 55–65. doi:10.1016/0022-3999(92)90114-h

Parker Z. J., Waller G., Duhne P. G. S., Dawson J. (2018). The role of exposure in treatment of anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 18 (1), 111–141. Available online at: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000498522300009.

Pascoe M., Bailey A. P., Craike M., Carter T., Patten R., Stepto N., et al. (2020). Physical activity and exercise in youth mental health promotion: a scoping review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 6 (1), e000677. doi:10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000677

Peens A., Pienaar A. E., Nienaber A. W. (2008). The effect of different intervention programmes on the self-concept and motor proficiency of 7- to 9-year-old children with DCD. Child. Care Health Dev. 34 (3), 316–328. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2007.00803.x

Philippot A., Dubois V., Lambrechts K., Grogna D., Robert A., Jonckheer U., et al. (2022). Impact of physical exercise on depression and anxiety in adolescent inpatients: a randomized controlled trial. J. Affect. Disord. 301, 145–153. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.011

Quach D., Mano K. E. J., Alexander K. (2016). A randomized controlled trial examining the effect of mindfulness meditation on working memory capacity in adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 58 (5), 489–496. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.024

Richards J., Foster C., Townsend N., Bauman A. (2014). Physical fitness and mental health impact of a sport-for-development intervention in a post-conflict setting: randomised controlled trial nested within an observational study of adolescents in Gulu, Uganda. BMC Public Health 14, 619. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-619

Rodrigues J. M., Matos L. C., Francisco N., Dias A., Azevedo J., Machado J. (2021). Assessment of qigong effects on anxiety of high-school students: a randomized controlled trial. Adv. Mind Body Med. 35 (3), 10–19. Available online at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34237025/.

Romero-Pérez E. M., González-Bernal J. J., Soto-Cámara R., González-Santos J., Tánori-Tapia J. M., Rodríguez-Fernández P., et al. (2020). Influence of a physical exercise program in the anxiety and depression in children with obesity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 (13), 4655. doi:10.3390/ijerph17134655

Silva L. A. D., Doyenart R., Henrique Salvan P., Rodrigues W., Felipe Lopes J., Gomes K., et al. (2020). Swimming training improves mental health parameters, cognition and motor coordination in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 30 (5), 584–592. doi:10.1080/09603123.2019.1612041

So W. W. Y., Lu E. Y. Q., Cheung W. M., Tsang H. W. H. (2020). Comparing mindful and non-mindful exercises on alleviating anxiety symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 (22), 8692. doi:10.3390/ijerph17228692

Syväoja H. J., Sneck S., Kukko T., Asunta P., Räsänen P., Viholainen H., et al. (2024). Effects of physically active maths lessons on children's maths performance and maths-related affective factors: multi-arm cluster randomized controlled trial. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 94 (3), 839–861. doi:10.1111/bjep.12684

Taylor S., Abramowitz J. S., McKay D. (2012). Non-adherence and non-response in the treatment of anxiety disorders. J. Anxiety Disord. 26 (5), 583–589. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.02.010

Wagener T. L., Fedele D. A., Mignogna M. R., Hester C. N., Gillaspy S. R. (2012). Psychological effects of dance-based group exergaming in obese adolescents. Pediatr. Obes. 7 (5), e68–e74. doi:10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00065.x

World Health Organization (2020). Adolescent health. Available online at: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/health-topics/adolescent-health (Accessed, 2025).

Zhao X., Li J., Xue C., Li Y., Lu T. (2024). Effects of exercise dose based on the ACSM recommendations on patients with post-stroke cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Front. Physiol. 15, 1364632. doi:10.3389/fphys.2024.1364632

Keywords: adolescents, anxiety, children, exercise, meta-analysis

Citation: Xian J, Hu Q and Jiang B (2026) Effects of exercise based on ACSM recommendations on anxiety in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Physiol. 16:1744254. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2025.1744254

Received: 11 November 2025; Accepted: 29 December 2025;

Published: 14 January 2026.

Edited by:

Pedro Forte, Higher Institute of Educational Sciences of the Douro, PortugalReviewed by:

Li Wang, Shanghai Ocean University, ChinaRafael Peixoto, Instituto Superior de Ciências Educativas, Portugal

Copyright © 2026 Xian, Hu and Jiang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bo Jiang, amlhbmdiQGpzc251LmVkdS5jbg==

Jinhua Xian

Jinhua Xian Bo Jiang

Bo Jiang