- 1National University of Physical Education and Sport of Ukraine, Kyiv, Ukraine

- 2Shandong Sport University, Jinan, China

Objectives: This systematic review and meta-analysis examined the effects of plyometric training (PT) on the physical fitness of adolescent team-sport athletes.

Methods: We systematically searched the PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Embase databases. The methodological quality of the studies was evaluated using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (ROB-2). Meta-analyses were conducted using RevMan 5.4 and STATA 15.0.

Results: A total of 31 studies involving 1,033 athletes (906 males and 127 females) were ultimately included. PT improved jump performance, including countermovement jump (ES = 0.89), countermovement jump with arms (ES = 1.00), squat jump (ES = 0.48), and standing long jump (ES = 1.10). PT also improved linear sprint over ≤10-m (ES = −0.59), 20-m (ES = −0.42), and 30-m (ES = −0.97), and improved change-of-direction (ES = −0.73).

Conclusion: Plyometric training can significantly improve the jumping performance, linear sprint and change-of-direction in adolescent team-sport athletes. Athletes aged 16–18.99 years may show larger improvements, and interventions lasting ≥8 to <10 weeks may be associated with more consistent gains, particularly for Countermovement Jump, SJ, ≤10-m linear sprint, and 20-m linear sprint. In contrast, increasing the total number of jumps was not consistently associated with greater training effects.

Systematic Review Registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, identifier CRD420251034889.

1 Introduction

Team sports such as football, basketball, handball, and volleyball are high-intensity intermittent sports (Stølen et al., 2005; Duncan et al., 2006; Ziv and Lidor, 2009; Abdelkrim et al., 2010), requiring athletes to repeatedly perform high-intensity explosive movements such as jumping, sprinting, sudden stops, and changes of direction, and high-intensity physical contact during the game (Ostojic et al., 2006; Faude et al., 2012; Passos et al., 2017; Taylor et al., 2017). Excellent physical fitness, such as strength, speed, and change of direction, is essential for executing explosive movements and for athletes to maintain peak performance and success in high-level competitions (Stølen et al., 2005; Ostojic et al., 2006; Wagner et al., 2014; Mancha-Triguero et al., 2019). During the critical period of neuromuscular development in adolescence, targeted physical training can not only effectively improve physical fitness, such as strength, speed, and agility, but also lay the foundation for an athletic career (Moran J. et al., 2017; Moran J. J. et al., 2017; Radnor et al., 2018). Jumping ability, speed, and change of direction are the basis for assessing athletic potential and future development into high-level athletes during the talent selection process for adolescents (Burgess and Naughton, 2010; Unnithan et al., 2012; Han et al., 2023; Kelly, 2023; Sanpasitt et al., 2023). Therefore, designing effective physical training methods for teenagers is very important.

Traditional resistance training, plyometric training (PT), compound training, and sprint training are commonly used effective training methods for improving physical fitness (MacDonald et al., 2012; Morris et al., 2022). Numerous studies have demonstrated that, compared with traditional resistance training, plyometric training may provide greater improvements in explosive power, sprint speed, and change-of-direction (Rædergård et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2025). PT utilizes the physiological advantages of stretch-shortening cycles (SSC), it employs a muscle contraction pattern characterized by a rapid eccentric pre-stretch followed by a rapid concentric contraction (Lloyd et al., 2011; Davies et al., 2015). This muscle contraction pattern is closer to the explosive movement patterns of jumping and sprinting in team sports such as basketball, football, and handball, thus improving performance in actual sports (Slimani et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2024). This improvement is primarily achieved through long-term training, leading to various adaptive mechanisms such as muscle fiber hypertrophy, enhanced motor unit recruitment, increased tendon stiffness, and improved intramuscular and intermuscular coordination (Komi, 2003; Fouré et al., 2010; Taube et al., 2012; Chu and Myer, 2013).

Numerous meta-analyses of PT have confirmed its effectiveness in improving jumping performance, linear sprinting, and change-of-direction. These studies either included both adults and adolescents or only included general adolescents, rather than trained adolescent athletes (de Villarreal et al., 2012; Oxfeldt et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2023a; Sun et al., 2025). Existing evidence suggests that untrained adolescents, due to their lower baseline fitness levels, show greater improvement than trained adolescents (Behm et al., 2017). Furthermore, adolescents are in a critical stage of growth and development, and their neuromuscular systems, hormonal and metabolic levels, and recovery and adaptation abilities differ from those of adults (Lloyd et al., 2015).Therefore, applying evidence from adults or untrained adolescents to guide PT programming in adolescent team-sport athletes may not yield optimal training adaptations.

Existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses have summarized the effects of PT in the adolescent population, but they mostly focus on specific groups and do not cover all the outcome indicators comprehensively (Chen et al., 2023b; Chen et al., 2024). Currently, there is a lack of a systematic evaluation that targets adolescent team sport athletes and integrates key physical fitness indicators such as jumping, different distances of linear sprints, and change-of-direction. Therefore, this meta-analysis aims to explore the impact of PT on the physical fitness of adolescent team athletes and to conduct moderating-variable analyses, including age, gender, training program, and training volume, to investigate the potential influence of these factors on the effectiveness of training. The aim is to establish an evidence base for the scientific development of safe and efficient PT programs for adolescent team sports.

2 Methods

This meta-analysis and systematic review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Moher et al., 2009). It was registered in PROSPERO under the registration number CRD420251034889.

2.1 Information sources and search strategy

A comprehensive search was conducted across the Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, and Embase databases. The initial search was conducted on 23 April 2025, and was updated on 6 November 2025. Database searches used keywords combined with MeSH terms. Search terms included: “Stretch-Shortening Exercise” OR “Stretch Shortening Cycle” OR “plyometric training” OR plyometric OR plyometrics OR “jump training” OR “jump exercise” OR “ballistic training” OR “drop jump” OR “depth jump” AND “basketball” OR “soccer” OR “football” OR “handball” OR “volleyball” OR “rugby” OR “team sport”. The search was limited to titles and abstracts, with no restrictions applied to publication region, year, or language. We also searched PROSPERO and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews for relevant protocols to determine whether they had been published.

2.2 Eligibility criteria

Eligibility criteria were defined according to the PICOS framework and are summarized in Table 1. The age range followed the World Health Organization definition of adolescents (10–19 years) (Organization, 2023).

2.3 Selection process

Duplicate references were identified and removed by one reviewer (FZ) using EndNote 21 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA). Two researchers (FZ and YL) then independently screened titles, abstracts, and full texts against the predefined criteria.

2.4 Data extraction

Basic information of the literature was extracted independently by one author (FZ), including: (1) author and publication year; (2) age and gender of the subjects; (3) sample size; (4) sport and athlete level; (5) intervention measures; (6) training duration, training frequency, and training volume; and (7) outcome indicators. The results were reviewed by a second author (YL). We first attempted to obtain missing or unclear data by directly emailing the corresponding authors. All discrepancies between reviewers were then resolved through discussion. For any persisting disagreements, a final decision was made by a designated senior reviewer (LS). To avoid overestimating the sample size, if a control group in a study is compared with multiple experimental groups, the sample size of the control group should be divided by the number of comparisons for allocation. Biological maturity information was extracted and summarized descriptively, with emphasis on the reported maturity metrics. Athlete level was reclassified in a standardized manner using the McKay Participant Classification Framework (PCF; Tier 0–5) (McKay et al., 2021). When multiple COD tests were reported in a study, only the longest test time was included in the analysis, defined as the COD protocol with the greatest total test distance or the highest number of directional changes.

2.5 Risk of bias assessment and certainty of evidence

Two assessors (FZ and JL) independently assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane RoB 2.0 tool. The assessment covered five domains: (D1) Randomisation process, (D2) deviations from intended interventions, (D3) missing outcome data, (D4) measurement of the outcome, and (D5) selection of the reported result. Judgements were made for each domain and overall, as low risk, some concerns, or high risk. The certainty of evidence for each primary outcome was assessed using the GRADE approach. As all included studies were randomized controlled trials, certainty started at high and was downgraded when applicable across the following domains: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and other considerations (e.g., publication bias). The overall certainty for each outcome was rated as high, moderate, low, or very low (Guyatt et al., 2011). Disagreements were resolved by discussion, with arbitration by a third assessor when necessary.

2.6 Statistical analysis

The meta-analyses were conducted using Review Manager V.5.4.0 and Stata 15.0. A total of eight meta-analyses were performed: (1) CMJ, (2) CMJA, (3) SJ, (4) SLJ, (5) ≤10-m linear sprint, (6) 20-m linear sprint, (7) 30-m linear sprint, (8) COD. A meta-analysis was conducted when at least three independent studies reported the same outcome measure (Borenstein et al., 2021). The effect size (ES) is represented by Hedge’s g and calculated by the mean and standard deviation of each dependent variable before and after training. For time-based outcomes, negative effect sizes represent improvements in performance. Given the expected between-study differences in participants, training programmes, and testing protocols, a random-effects model was used to pool effect sizes. Pooled effects are presented as Hedges’g with 95% confidence intervals (Deeks et al., 2019). The effect size is explained by the following criteria: trivial (<0.2), small (0.2-0.6), moderate (>0.6-1.2), large (>1.2-2.0), very large (>2.0-4.0), and extremely large (>4.0) (Hopkins et al., 2009). Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using the I2 statistic, categorized as low (<25%), moderate (25%–75%), or high (>75%) (Higgins and Thompson, 2002). Egger’s test was used to assess publication bias. When publication bias was detected, the trim-and-fill method was used (Duval and Tweedie, 2000). Sensitivity analysis was employed to ensure the robustness of the meta-analysis results. p < 0.05 was set as the threshold for statistical significance.

To explore potential sources of heterogeneity, subgroup analyses and meta-regression analyses were conducted. Age, training duration, and total number of jumps were taken as moderating variables. Specifically, age groups followed the WHO age-based developmental stage classification described in: 10–12.99 (pre-PHV), 13–15.99 (mid-PHV), and 16–18.99 years (post-PHV), which reflects chronological age rather than directly assessed maturity. The training duration and the total number of jumps lack standardized classifications. To ensure the subgroup analysis has sufficient statistical power, we grouped them according to the distributions observed in the included studies. Meta-regression analysis was conducted when at least 10 studies reported the same outcomes (Cumpston et al., 2019).

3 Results

3.1 Study selection

A preliminary literature search yielded 5,407 articles. After deleting duplicate literature, an initial screening was performed based on the title and abstract, followed by downloading and reading the full text. Finally, 31 studies met the inclusion criteria (Sankey et al., 2008; Sedano et al., 2011; Ozbar et al., 2014; Zribi et al., 2014; Attene et al., 2015; Hammami et al., 2016; Asadi et al., 2018; Hernández et al., 2018; Ramirez-Campillo et al., 2018; Fathi et al., 2019; Jlid et al., 2019; Meszler and Váczi, 2019; Ramirez-Campillo et al., 2019; Drouzas et al., 2020; Negra et al., 2020; Ramirez-Campillo et al., 2020a; Ramirez-Campillo et al., 2020b; Vera-Assaoka et al., 2020; de Villarreal et al., 2021; Noutsos et al., 2021; Padrón-Cabo et al., 2021; Palma-Muñoz et al., 2021; Paes et al., 2022; Gaamouri et al., 2023; Aztarain-Cardiel et al., 2024; BOGIATZIDIS et al., 2024; Haghighi et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2024; Sammoud et al., 2024; Türkarslan and Deliceoglu, 2024; Öztürk et al., 2025). The complete literature screening process is summarized in Figure 1.

3.2 Characteristics of participants and interventions

Characteristics of study participants and intervention protocols are detailed in Table 2.

3.2.1 Sample size

Thirty-one articles included a total of 1,033 participants (127 females, 906 males), with individual studies ranging from 15 to 76 participants. This comprised 247 basketball players, 667 footballers, 61 handball players, 40 volleyball players, and 18 rugby players.

3.2.2 Sex

Twenty-five studies included male participants, five studies included female participants, and one study included both.

3.2.3 Biological maturity

Eight studies used maturity offset, seven used Tanner staging, and sixteen did not report maturity-related information.

3.2.4 Playing level

Based on the McKay Participant Classification Framework, most included studies involved developmental-level athletes, while a smaller number examined national-level players.

3.2.5 Training duration

The studies ranged in duration from 6 to 12 weeks, with only one lasting 16 weeks.

3.2.6 Training frequency

Twenty-eight studies employed twice-weekly training. Two studies employed a once-weekly frequency. Only one study reported a frequency of three times a week.

3.2.7 Session duration

Twenty-four studies indicated single-session lengths varying from 15 to 60 min.

3.2.8 Training volume (total number of jumps)

The number of jumps in a single session was between 24 and 220. The total number of jumps ranged from 512 to 2,880.

3.2.9 Intervention methods

Twenty studies combined horizontal and vertical PT. Eight studies employed vertical PT. Two studies included only horizontal PT. One study reported both vertical and horizontal PT.

3.2.10 Seasonal training timing

Twenty-three studies reported implementing training programs during the season, while six studies reported pre-season implementation. Three studies did not report this information.

3.3 Risk of bias assessment and certainty of evidence

Detailed results of the bias risk assessment for each area and overall are presented in Figures 2, 3. The primary sources of risk of bias were “randomization process” and “deviation from the intended intervention”, as it is challenging to blind participants and assessors in sports training. Only six studies explicitly described the randomization process (Hernández et al., 2018; Fathi et al., 2019; Ramirez-Campillo et al., 2020a; Ramirez-Campillo et al., 2020b; Liu et al., 2024; Sammoud et al., 2024). Only two studies were rated as having a low risk of bias in the domain of deviations from the intended interventions (Attene et al., 2015; Palma-Muñoz et al., 2021). For the primary outcome, the GRADE evidence quality level is low or very low (see Table 3). Downgrading was mainly due to risk of bias, inconsistency, and imprecision, with suspected publication bias for several outcomes.

3.4 Meta-analysis results

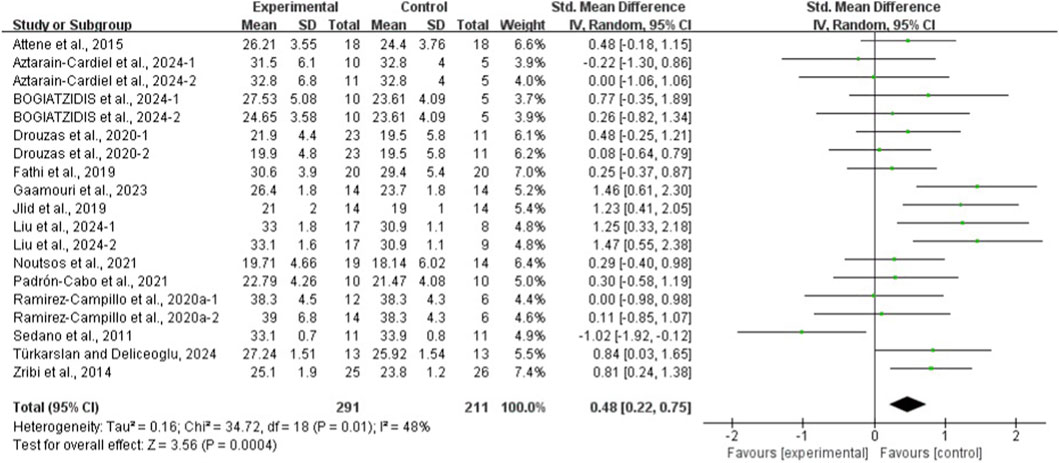

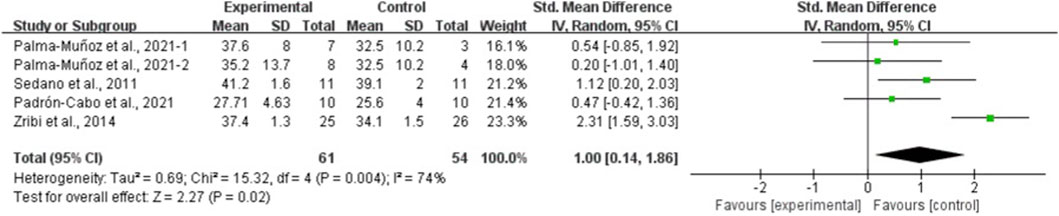

The results of the eight meta-analyses are presented in Table 4, and the corresponding forest plots are provided in Figures 4–11.

Table 4. Synthesis of results across included studies regarding the effects of plyometric training on physical fitness measures.

Figure 4. Forest plot of the effect of plyometric training on CMJ in adolescent team-sport athletes.

Figure 6. Forest plot of the effect of plyometric training on CMJA in adolescent team-sport athletes.

Figure 7. Forest plot of the effect of plyometric training on SLJ in adolescent team-sport athletes.

Figure 8. Forest plot of the effect of plyometric training on ≤10-m linear sprint in adolescent team-sport athletes.

![Forest plot depicting the standardized mean differences with 95% confidence intervals for multiple studies comparing experimental and control groups. The overall effect size is -0.42 with a 95% CI of [-0.63, -0.21]. The plot shows heterogeneity statistics with Tau-squared of 0.09, Chi-squared of 35.59, degrees of freedom 24, and a P-value of 0.06, indicating moderate heterogeneity. The test for overall effect is significant with Z = 3.91 (P < 0.0001). The diamond symbol represents the pooled overall effect size, favoring the experimental condition.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1760239/fphys-17-1760239-HTML/image_m/fphys-17-1760239-g009.jpg)

Figure 9. Forest plot of the effect of plyometric training on 20-m linear sprint in adolescent team-sport athletes.

Figure 10. Forest plot of the effect of plyometric training on 30-m linear sprint in adolescent team-sport athletes.

Figure 11. Forest plot of the effect of plyometric training on COD in adolescent team-sport athletes.

PT significantly improved jump performance (CMJ: ES = 0.89, 95% CI: 0.59–1.19, I2 = 75%; CMJA: ES = 1.00, 95% CI: 0.14–1.86, I2 = 74%; SJ: ES = 0.48, 95% CI: 0.22–0.75, I2 = 48%; SLJ: ES = 1.10, 95% CI: 0.62–1.58, I2 = 62%). For time-based outcomes, PT also improved linear sprint performance (≤10 m: ES = −0.59, 95% CI: −0.87 to −0.32, I2 = 49%; 20 m: ES = −0.42, 95% CI: −0.63 to −0.21, I2 = 33%; 30 m: ES = −0.97, 95% CI: −1.68 to −0.26, I2 = 59%) and COD (ES = −0.73, 95% CI: −1.02 to −0.45, I2 = 60%).

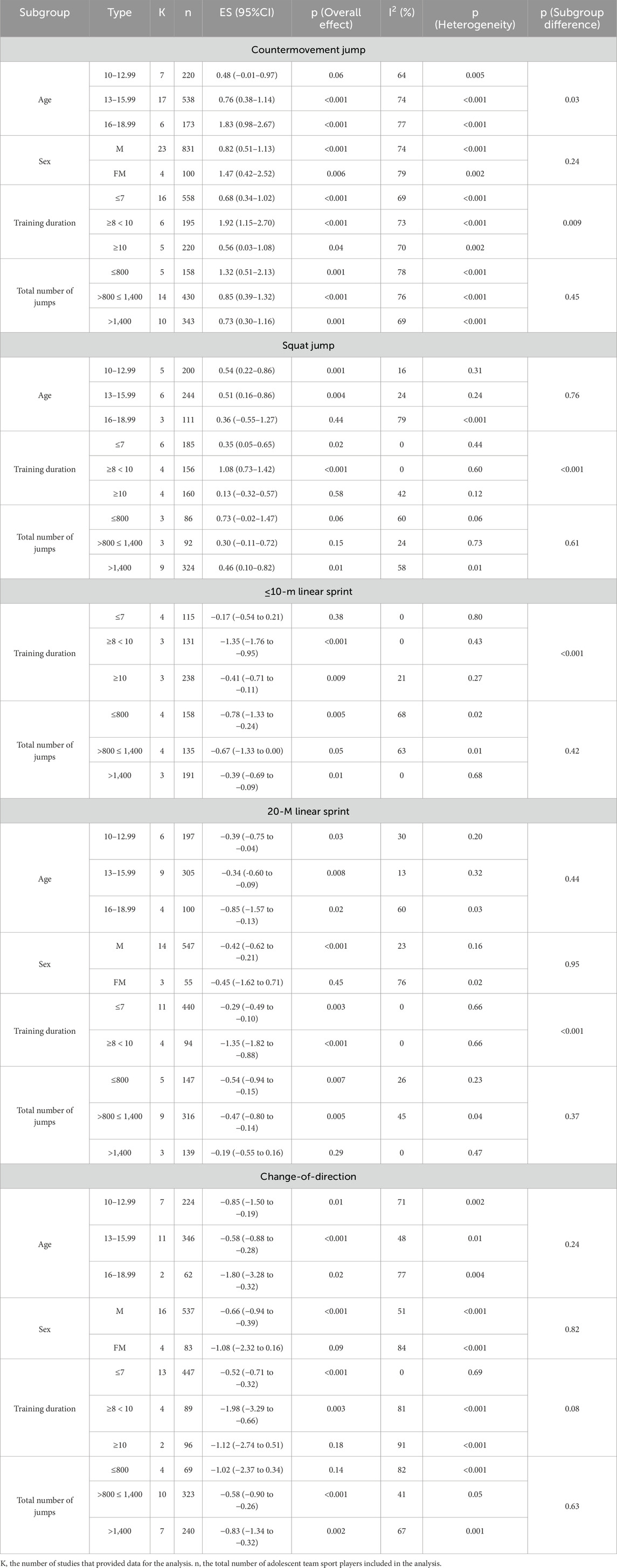

3.5 Additional analyses

A total of 17 subgroup analyses were conducted (Table 5). For CMJ, significant between-subgroup differences were observed for age (p = 0.04) and training duration (p = 0.009), with the largest improvements in athletes aged 16–18.99 years and in programmes lasting ≥8 to <10 weeks. For SJ, significant between-subgroup differences were observed for training duration (p < 0.001), with the largest improvement in programmes lasting ≥8 to <10 weeks. Similarly, for the ≤10-m and 20-m linear sprints, training duration showed significant between-subgroup differences (p < 0.001), with the greatest improvements in programmes lasting ≥8 to <10 weeks. Detailed information on the pooled effect size, heterogeneity, and the number of included studies for each subgroup can be found in Table 5.

When there were at least 10 studies for the same outcome measure, age, training duration, and training volume (total number of jumps) were used as covariates in a meta-regression analysis (see Table 6). The results indicated that age was significantly associated with improvements in CMJ (β = 0.211, p = 0.026), ≤10-m linear sprint (β = −0.119, p = 0.031), 20-m linear sprint (β = −0.117, p = 0.023), and COD (β = −0.163, p = 0.048). Training duration was significantly associated with improvements in 20-m linear sprint time (β = −0.206, p = 0.034). The total number of jumps was significantly associated with improvements in the SJ, although the magnitude of the association was small (β = −0.00048, p = 0.049).

Table 6. Multivariate meta-regression for training variables to predict plyometric training effects.

3.6 Publication bias and sensitivity analyses

Publication bias was assessed only for outcomes with ≥10 studies. Therefore, Egger tests were performed for five outcomes (see Table 4). CMJ and COD showed a risk of publication bias. By using the trim-and-fill method for adjustment, the results' significance remained unchanged, indicating that publication bias did not significantly affect the effect size.

Sensitivity analyses indicated that the pooled ES was robust for CMJ, SJ, SLJ, all sprint outcomes, and COD, whereas the pooled ES for CMJA was sensitive to omission of individual studies (Supplementary Figures S1–S8).

4 Discussion

Overall, this systematic review and meta-analysis indicates that plyometric training (PT) can enhance the jumping, linear sprint, and change of direction (COD) performance of adolescent team sport athletes. However, there is moderate to high heterogeneity in multiple outcome measures, and the certainty of evidence is generally low to very low. Therefore, the results of subgroup analysis and meta-regression should be interpreted with caution and regarded as exploratory findings, which are not sufficient to form definitive conclusions.

4.1 Jump performance

The meta-analysis showed that PT can effectively improve jump performance in youth team-sport athletes. Specifically, PT significantly improved CMJ (ES = 0.89), CMJA (ES = 1.00), and SLJ (ES = 1.10), whereas the improvement in SJ (ES = 0.48) was smaller but still statistically significant. CMJA results should be interpreted cautiously because they were not robust in sensitivity analyses.

Notably, the improvement in CMJ was clearly larger than that in SJ, suggesting that PT may be more sensitive for jumps involving a countermovement. This may be related to the relatively long pause at the bottom position of the SJ (three to five s). Such a pause may reduce the use of elastic energy stored during the eccentric phase, forcing the movement to rely mainly on concentric contraction, and thereby limiting the contribution of the SSC (MacDougall and Sale, 2014; Stojanović et al., 2017). Improvements in jump performance following PT may be related to structural and neuromuscular adaptations, such as muscle fiber hypertrophy and improved tendon collagen properties, which increase tendon stiffness (Pääsuke et al., 2001; Shepstone et al., 2005), enhance the rapid recruitment of high-threshold motor units, improve central nervous system excitability and reflex control, and strengthen intermuscular and intramuscular coordination (Markovic and Mikulic, 2010; Seiberl et al., 2021).

Regarding potential moderators, subgroup and meta-regression analyses suggested that age and training duration may be associated with the CMJ training effect. The subgroup aged 16–18.99 years showed a greater improvement in CMJ performance (ES = 1.83, p = 0.04), and meta-regression similarly demonstrated a significant association between age and CMJ improvement (β = 0.211, p = 0.026). Importantly, the subgroup and meta-regression results were consistent, suggesting that age may be associated with PT responsiveness. A reasonable explanation is that in older adolescent athletes, a more mature central nervous system and higher levels of testosterone and growth hormone may promote structural and neuromuscular adaptations (Moran J. J. et al., 2017; Radnor et al., 2018; Ramirez-Campillo et al., 2023). In contrast, in younger athletes, lower hormone levels may limit structural adaptations, and their improvements are more related to neuromuscular optimization (Tumkur Anil Kumar et al., 2021). However, because age was used as a proxy rather than directly assessed biological maturity, this interpretation should be considered cautiously.

For training duration, CMJ showed a larger improvement in programmes lasting ≥8 to <10 weeks (ES = 1.92, p = 0.009), and the SJ duration subgroup showed a similar trend (ES = 1.08, p < 0.001). Taken together, the current evidence indicates that programmes lasting ≥8 to <10 weeks may yield clearer improvements in jump performance, without showing that “longer is always better.” The meta-regression indicated a very small negative correlation between the total number of jumps and SJ improvement (β = −0.00048, p = 0.049), which has limited practical significance and should be interpreted with caution. However, the current evidence is insufficient to support the idea that increasing the total number of jumps leads to better training outcomes. One possible explanation is that, because the neuromuscular system of adolescents is still developing, excessive training volume may lead to central nervous system fatigue and high energy expenditure, resulting in impaired neural regulation and the accumulation of metabolic stress. These factors may compromise explosive performance and increase the risk of sports-related injuries (Cairns, 2006; Schoenfeld, 2010; Enoka and Duchateau, 2016). In contrast, appropriately prescribed training duration and volume may facilitate the restoration of energy reserves and muscle tissue repair following high-intensity training, thereby promoting supercompensation (Şahin et al., 2022; Luo et al., 2025). Notably, rapid growth around peak height velocity (PHV) may be associated with a further increase in injury risk (Faigenbaum et al., 2009; Luke et al., 2011). Therefore, greater emphasis should be placed on balancing training load and recovery during this stage.

4.2 Linear sprinting

The meta-analysis showed that plyometric training (PT) can significantly improve linear sprint performance in adolescent team-sport athletes. PT significantly improved ≤10-m (ES = −0.59), 20-m (ES = −0.42), and 30-m sprint performance (ES = −0.97). In practical terms, adding PT to regular sport-specific training may benefit both short-distance acceleration and longer-distance sprint performance. PT may enhance sprint performance through improved neural drive and neuromuscular coordination, increased lower-limb stiffness, and improved rapid force production, which together may reduce ground contact time and increase step frequency (Ross et al., 2001; Mackala and Fostiak, 2015; Tomalka et al., 2020).

Regarding potential moderators, subgroup analysis indicated that for ≤10-m sprint, programmes lasting ≥8 to <10 weeks produced larger improvements (ES = −1.35), with significant between-subgroup differences compared with ≤7 weeks and ≥10 weeks (p < 0.001). A similar pattern was also observed for 20 m sprint (ES = −1.35, p < 0.001). These findings suggest that a duration of ≥8 to <10 weeks may be more favorable for sprint improvements, but this should not be interpreted as a definitive “optimal” training duration. A reasonable explanation is that shorter programmes may provide insufficient accumulated stimulus, whereas longer programmes may involve excessive SSC loading, which may reduce tendon stiffness and make muscle fatigue and a neuromuscular adaptation plateau more likely, thereby compromising recovery (Komi, 2000; Nicol et al., 2006).

For age-related effects, meta-regression showed that age was associated with the training effect for both ≤10-m and 20-m sprints (≤10-m: β = −0.118, p = 0.031; 20-m: β = −0.117, p = 0.023), suggesting that older athletes may achieve larger improvements. With growth and development, progressive central nervous system maturation and hormonal changes may facilitate structural and neuromuscular adaptations (Lloyd and Oliver, 2013; Radnor et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2022); meanwhile, increases in lower-limb length may optimize the stride length–frequency combination and translate more effectively into sprint performance (Asadi et al., 2018). In addition, older athletes typically have longer trained experience, more stable neuromuscular control, and more consistent sprint technique, which may facilitate the translation of PT stimuli into sprint gains (Fort-Vanmeerhaeghe et al., 2016). In terms of the total number of jumps, the current evidence is insufficient to support the claim that simply increasing the total number of jumps can lead to better sprint training results. Further research is needed to verify this.

4.3 Agility (change-of-direction)

The meta-analysis demonstrated that plyometric training (PT) significantly improves change-of-direction (COD) performance in adolescent team-sport athletes, with a moderate overall effect size (ES = −0.73). Good COD is essential in team sports such as basketball, football, and handball, as it is closely related to offensive and defensive actions, the creation of scoring opportunities, and may be associated with reduced injury risk. These findings indicate that incorporating PT into regular sport-specific training may enhance COD and contribute to improved overall sport performance.

During COD tasks, athletes are required to rapidly transition between deceleration and re-acceleration, a process that fundamentally relies on eccentric–concentric muscle actions and the stretch–shortening cycle (SSC) of the lower-limb musculature (Sheppard and Young, 2006; Chaabene et al., 2018). PT imposes substantial inertial and eccentric braking loads during the deceleration phase, which may enhance eccentric strength and neural drive, improve inter- and intramuscular coordination, increase SSC efficiency, and enhance balance and joint stability (Markovic and Mikulic, 2010; Granacher et al., 2015; Chaabene et al., 2018; Jimenez-Iglesias et al., 2024). Collectively, these adaptations may facilitate faster deceleration control and more efficient re-acceleration, ultimately leading to improvements in COD performance.

Regarding potential moderators, age-based subgroup analyses did not reach statistical significance; however, meta-regression indicated that age may be associated with the COD training effect (β = −0.163, p = 0.048), suggesting that training responses may differ across age groups. With respect to training duration, no significant differences were observed between subgroups, although meta-regression revealed a borderline trend (β = −0.282, p = 0.050). In terms of the total number of jumps, the current evidence does not support achieving greater improvements in COD performance simply by increasing the total number of jumps.

4.4 Study limitations

Several limitations of this study should be considered when interpreting the results. The risk of bias assessment revealed that most included studies were assessed to have “some concerns” or a “high risk” of bias, primarily in the “randomization process” and “deviation from the intended interventions”, as it is challenging to blind participants and assessors in sports training. Furthermore, the GRADE quality of evidence indicated that the quality of evidence for the outcome indicators was mainly low to very low. These limitations may bias estimates of the impact of PT on the physical fitness of adolescent team athletes. Only five of the included studies focused on female adolescents, limiting the applicability of the findings to female adolescent sports teams. Therefore, more research on female adolescents is needed in the future. The information on biological maturity was insufficient and inconsistent (8 articles for PHV, seven articles for Tanner, and 16 articles did not report), and the types of maturity indicators were not uniform, which limited the further examination of the differences in the maturity stages. Although this study used the WHO age-based developmental stages for age grouping, this grouping does not represent the directly measured biological maturity and may mask the impact of true maturity differences on training adaptation. Finally, the information on ground contact time was insufficiently reported: most studies did not provide quantifiable ground contact time data or unified monitoring methods, and some only made qualitative descriptions such as “quick landing”. Safety reporting was a major limitation of the evidence base. As adverse events were rarely reported, safety outcomes could not be synthesized, and PT safety remains uncertain in this population.

4.5 Practical applications

PT is a feasible and effective training method for enhancing the jumping, sprinting and COD abilities of youth team sports athletes. A training program conducted twice a week for a duration of ≥8 weeks to <10 weeks can lead to more stable improvements in multiple physical performance indicators. In practical training, the focus of the training should not merely be on achieving a high total number of jumps, but should be adjusted individually based on the athlete’s developmental stage, training experience, recovery status and season workload.

5 Conclusion

Plyometric training improves jumping, linear sprint, and change-of-direction performance in adolescent team-sport athletes. Age may moderate the training response, with athletes aged 16–18.99 years showing larger improvements in CMJ, ≤10-m linear sprint, 20-m linear sprint and COD. Interventions lasting ≥8 to <10 weeks were associated with more consistent gains, particularly for CMJ, ≤10-m linear sprint, and 20-m linear sprint. The available evidence does not indicate that simply increasing total number of jumps is consistently associated with greater performance gains.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

FZ: Writing – review and editing, Validation, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Methodology. YL: Writing – review and editing, Investigation, Validation, Data curation. JL: Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization, Validation, Data curation. OY: Validation, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. LS: Supervision, Writing – review and editing, Investigation, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2026.1760239/full#supplementary-material

References

Abdelkrim N. B., Castagna C., Jabri I., Battikh T., El Fazaa S., El Ati J. (2010). Activity profile and physiological requirements of junior elite basketball players in relation to aerobic-anaerobic fitness. J. Strength and Cond. Res. 24 (9), 2330–2342. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e381c1

Asadi A., Ramirez-Campillo R., Arazi H., Sáez de Villarreal E. (2018). The effects of maturation on jumping ability and sprint adaptations to plyometric training in youth soccer players. J. Sports Sciences 36 (21), 2405–2411. doi:10.1080/02640414.2018.1459151

Attene G., Iuliano E., Di Cagno A., Calcagno G., Moalla W., Aquino G., et al. (2015). Improving neuromuscular performance in young basketball players: plyometric vs. technique training. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 55 (1-2), 1–8.

Aztarain-Cardiel K., Garatachea N., Pareja-Blanco F. (2024). Effects of plyometric training volume on physical performance in youth basketball players. J. Strength and Cond. Res. 38 (7), 1275–1279. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000004779

Behm D. G., Young J. D., Whitten J. H., Reid J. C., Quigley P. J., Low J., et al. (2017). Effectiveness of traditional strength vs. power training on muscle strength, power and speed with youth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Physiology 8, 423. doi:10.3389/fphys.2017.00423

Bogiatzidis E., Ispyrlidis I., Gourgoulis V., Bogiatzidis A., Smilios I. (2024). Effects of vertical versus horizontal plyometric training on adolescent soccer players' physical performance. Trends Sport Sci. 31 (2). doi:10.23829/TSS.2024.31.2-3

Borenstein M., Hedges L. V., Higgins J. P., Rothstein H. R. (2021). Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons.

Burgess D. J., Naughton G. A. (2010). Talent development in adolescent team sports: a review. Int. Journal Sports Physiology Performance 5 (1), 103–116. doi:10.1123/ijspp.5.1.103

Cairns S. P. (2006). Lactic acid and exercise performance: culprit or friend? Sports Medicine 36 (4), 279–291. doi:10.2165/00007256-200636040-00001

Chaabene H., Prieske O., Negra Y., Granacher U. (2018). Change of direction speed: toward a strength training approach with accentuated eccentric muscle actions. Sports Medicine 48 (8), 1773–1779. doi:10.1007/s40279-018-0907-3

Chen L., Huang Z., Xie L., He J., Ji H., Huang W., et al. (2023a). Maximizing plyometric training for adolescents: a meta-analysis of ground contact frequency and overall intervention time on jumping ability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Reports 13 (1), 21222. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-48274-3

Chen L., Zhang Z., Huang Z., Yang Q., Gao C., Ji H., et al. (2023b). Meta-analysis of the effects of plyometric training on lower limb explosive strength in adolescent athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20 (3), 1849. doi:10.3390/ijerph20031849

Chen L., Yan R., Xie L., Zhang Z., Zhang W., Wang H. (2024). Maturation-specific enhancements in lower extremity explosive strength following plyometric training in adolescent soccer players: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 10 (12), e33063. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e33063

Cumpston M., Li T., Page M. J., Chandler J., Welch V. A., Higgins J. P., et al. (2019). Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews 2019 (10), ED000142. doi:10.1002/14651858.ED000142

Davies G., Riemann B. L., Manske R. (2015). Current concepts of plyometric exercise. Int. Journal Sports Physical Therapy 10 (6), 760–786.

de Villarreal E. S., Requena B., Cronin J. B. (2012). The effects of plyometric training on sprint performance: a meta-analysis. J. Strength and Cond. Res. 26 (2), 575–584. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e318220fd03

de Villarreal E. S., Molina J. G., de Castro-Maqueda G., Gutiérrez-Manzanedo J. V. (2021). Effects of plyometric, strength and change of direction training on high-school basketball player’s physical fitness. J. Hum. Kinet. 78, 175–186. doi:10.2478/hukin-2021-0036

Deeks J. J., Higgins J. P., Altman D. G., Group C. S. M. (2019). Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. Cochrane Handbook Systematic Reviews Interventions, 241–284. doi:10.1002/9781119536604.ch10

Drouzas V., Katsikas C., Zafeiridis A., Jamurtas A. Z., Bogdanis G. C. (2020). Unilateral plyometric training is superior to volume-matched bilateral training for improving strength, speed and power of lower limbs in preadolescent soccer athletes. J. Human Kinetics 74, 161–176. doi:10.2478/hukin-2020-0022

Duncan M., Woodfield L., Al-Nakeeb Y. (2006). Anthropometric and physiological characteristics of junior elite volleyball players. Br. Journal Sports Medicine 40 (7), 649–651. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2005.021998

Duval S., Tweedie R. (2000). Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 56 (2), 455–463. doi:10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x

Enoka R. M., Duchateau J. (2016). Translating fatigue to human performance. Med. Science Sports Exercise 48 (11), 2228–2238. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000000929

Faigenbaum A. D., Kraemer W. J., Blimkie C. J., Jeffreys I., Micheli L. J., Nitka M., et al. (2009). Youth resistance training: updated position statement paper from the national strength and conditioning association. J. Strength and Cond. Res. 23, S60–S79. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31819df407

Fathi A., Hammami R., Moran J., Borji R., Sahli S., Rebai H. (2019). Effect of a 16-week combined strength and plyometric training program followed by a detraining period on athletic performance in pubertal volleyball players. J. Strength and Cond. Res. 33 (8), 2117–2127. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002461

Faude O., Koch T., Meyer T. (2012). Straight sprinting is the most frequent action in goal situations in professional football. J. Sports Sciences 30 (7), 625–631. doi:10.1080/02640414.2012.665940

Fort-Vanmeerhaeghe A., Romero-Rodriguez D., Lloyd R. S., Kushner A., Myer G. D. (2016). Integrative neuromuscular training in youth athletes. Part II: strategies to prevent injuries and improve performance. Strength and Cond. J. 38 (4), 9–27. doi:10.1519/ssc.0000000000000234

Fouré A., Nordez A., Cornu C. (2010). Plyometric training effects on Achilles tendon stiffness and dissipative properties. J. Applied Physiology 109 (3), 849–854. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01150.2009

Gaamouri N., Hammami M., Cherni Y., Rosemann T., Knechtle B., Chelly M. S., et al. (2023). The effects of 10-week plyometric training program on athletic performance in youth female handball players. Front. Sports Active Living 5, 1193026. doi:10.3389/fspor.2023.1193026

Granacher U., Prieske O., Majewski M., Büsch D., Muehlbauer T. (2015). The role of instability with plyometric training in sub-elite adolescent soccer players. Int. Journal Sports Medicine 36 (05), 386–394. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1395519

Guyatt G., Oxman A. D., Akl E. A., Kunz R., Vist G., Brozek J., et al. (2011). GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction—Grade evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J. Clinical Epidemiology 64 (4), 383–394. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026

Haghighi A. H., Hosseini S. B., Askari R., Shahrabadi H., Ramirez-Campillo R. (2024). Effects of plyometric compared to high-intensity interval training on youth female basketball player’s athletic performance. Sport Sci. Health 20 (1), 211–220. doi:10.1007/s11332-023-01096-2

Hammami M., Negra Y., Aouadi R., Shephard R. J., Chelly M. S. (2016). Effects of an in-season plyometric training program on repeated change of direction and sprint performance in the junior soccer player. J. Strength and Cond. Res. 30 (12), 3312–3320. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001470

Han M., Gómez-Ruano M.-A., Calvo A. L., Calvo J. L. (2023). Basketball talent identification: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the anthropometric, physiological and physical performance factors. Front. Sports Act. Living 5, 1264872. doi:10.3389/fspor.2023.1264872

Hernández S., Ramirez-Campillo R., Álvarez C., Sanchez-Sanchez J., Moran J., Pereira L. A., et al. (2018). Effects of plyometric training on neuromuscular performance in youth basketball players: a pilot study on the influence of drill randomization. J. Sports Science and Medicine 17 (3), 372–378.

Higgins J. P., Thompson S. G. (2002). Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics Medicine 21 (11), 1539–1558. doi:10.1002/sim.1186

Hopkins W., Marshall S., Batterham A., Hanin J. (2009). Progressive statistics for studies in sports medicine and exercise science. Medicine+ Sci. Sports+ Exerc. 41 (1), 3–13. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818cb278

Jimenez-Iglesias J., Owen A. L., Cruz-Leon C., Campos-Vázquez M. A., Sanchez-Parente S., Gonzalo-Skok O., et al. (2024). Improving change of direction in male football players through plyometric training: a systematic review. Sport Sci. Health 20 (4), 1131–1152. doi:10.1007/s11332-024-01230-8

Jlid M. C., Racil G., Coquart J., Paillard T., Bisciotti G. N., Chamari K. (2019). Multidirectional plyometric training: very efficient way to improve vertical jump performance, change of direction performance and dynamic postural control in young soccer players. Front. Physiology 10, 1462. doi:10.3389/fphys.2019.01462

Kelly A. (2023). Talent identification and development in youth soccer: a guide for researchers and practitioners. Abingdon, United Kingdom: Taylor and Francis.

Komi P. V. (2000). Stretch-shortening cycle: a powerful model to study normal and fatigued muscle. J. Biomechanics 33 (10), 1197–1206. doi:10.1016/s0021-9290(00)00064-6

Liu G., Wang X., Xu Q. (2024). Microdosing plyometric training enhances jumping performance, reactive strength index, and acceleration among youth soccer players: a randomized controlled study design. J. Sports Sci. and Med. 23 (2), 342–350. doi:10.52082/jssm.2024.342

Lloyd R. S., Oliver J. (2013). Strength and conditioning for young athletes. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis.

Lloyd R. S., Meyers R. W., Oliver J. L. (2011). The natural development and trainability of plyometric ability during childhood. Strength and Cond. J. 33 (2), 23–32. doi:10.1519/ssc.0b013e3182093a27

Lloyd R. S., Oliver J. L., Faigenbaum A. D., Howard R., Croix M. B. D. S., Williams C. A., et al. (2015). Long-term athletic development-part 1: a pathway for all youth. J. Strength and Cond. Res. 29 (5), 1439–1450. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000756

Luke A., Lazaro R. M., Bergeron M. F., Keyser L., Benjamin H., Brenner J., et al. (2011). Sports-related injuries in youth athletes: is overscheduling a risk factor? Clin. Journal Sport Medicine 21 (4), 307–314. doi:10.1097/JSM.0b013e3182218f71

Luo H., Zhu X., Nasharuddin N. A., Kamalden T. F. T., Xiang C. (2025). Effects of strength and plyometric training on vertical jump, Linear sprint, and change-of-direction speed in female adolescent team sport athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sports Sci. and Med. 24 (2), 406–452. doi:10.52082/jssm.2025.406

MacDonald C. J., Lamont H. S., Garner J. C. (2012). A comparison of the effects of 6 weeks of traditional resistance training, plyometric training, and complex training on measures of strength and anthropometrics. J. Strength and Cond. Res. 26 (2), 422–431. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e318220df79

Mackala K., Fostiak M. (2015). Acute effects of plyometric intervention—Performance improvement and related changes in sprinting gait variability. J. Strength and Cond. Res. 29 (7), 1956–1965. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000853

Mancha-Triguero D., García-Rubio J., Calleja-González J., Ibáñez S. J. (2019). Physical fitness in basketball players: a systematic review. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 59 (10.23736), S0022–S4707. doi:10.23736/s0022-4707.19.09180-1

Markovic G., Mikulic P. (2010). Neuro-musculoskeletal and performance adaptations to lower-extremity plyometric training. Sports Medicine 40 (10), 859–895. doi:10.2165/11318370-000000000-00000

McKay A. K., Stellingwerff T., Smith E. S., Martin D. T., Mujika I., Goosey-Tolfrey V. L., et al. (2021). Defining training and performance caliber: a participant classification framework. Int. Journal Sports Physiology Performance 17 (2), 317–331. doi:10.1123/ijspp.2021-0451

Meszler B., Váczi M. (2019). Effects of short-term in-season plyometric training in adolescent female basketball players. Physiol. International 106 (2), 168–179. doi:10.1556/2060.106.2019.14

Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Bmj 339, b2535. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2535

Moran J., Sandercock G. R., Ramírez-Campillo R., Meylan C., Collison J., Parry D. A. (2017a). A meta-analysis of maturation-related variation in adolescent boy athletes’ adaptations to short-term resistance training. J. Sports Sciences 35 (11), 1041–1051. doi:10.1080/02640414.2016.1209306

Moran J. J., Sandercock G. R., Ramirez-Campillo R., Meylan C. M., Collison J. A., Parry D. A. (2017b). Age-related variation in male youth athletes' countermovement jump after plyometric training: a meta-analysis of controlled trials. J. Strength and Cond. Res. 31 (2), 552–565. doi:10.1519/jsc.0000000000001444

Morris S. J., Oliver J. L., Pedley J. S., Haff G. G., Lloyd R. S. (2022). Comparison of weightlifting, traditional resistance training and plyometrics on strength, power and speed: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Sports Medicine 52 (7), 1533–1554. doi:10.1007/s40279-021-01627-2

Negra Y., Chaabene H., Fernandez-Fernandez J., Sammoud S., Bouguezzi R., Prieske O., et al. (2020). Short-term plyometric jump training improves repeated-sprint ability in prepuberal male soccer players. J. Strength and Cond. Res. 34 (11), 3241–3249. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002703

Nicol C., Avela J., Komi P. V. (2006). The stretch-shortening cycle: a model to study naturally occurring neuromuscular fatigue. Sports Medicine 36 (11), 977–999. doi:10.2165/00007256-200636110-00004

Noutsos S., Meletakos P., Athanasiou P., Tavlaridis A., Bayios I. (2021). Effect of plyometric training on performance parameters in young handball players. Gazzetta Medica Ital. 180 (10), 568–574. doi:10.23736/s0393-3660.21.04588-5

Organization W. H. (2023). Global Accelerated Action for the Health of Adolescents (AA-HA!): guidance to support country implementation. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Ostojic S. M., Mazic S., Dikic N. (2006). Profiling in basketball: physical and physiological characteristics of elite players. J. Strength and Cond. Res. 20 (4), 740–744. doi:10.1519/R-15944.1

Oxfeldt M., Overgaard K., Hvid L. G., Dalgas U. (2019). Effects of plyometric training on jumping, sprint performance, and lower body muscle strength in healthy adults: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Scand. Journal Medicine and Science Sports 29 (10), 1453–1465. doi:10.1111/sms.13487

Ozbar N., Ates S., Agopyan A. (2014). The effect of 8-week plyometric training on leg power, jump and sprint performance in female soccer players. J. Strength and Cond. Res. 28 (10), 2888–2894. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000541

Öztürk B., Adıgüzel N. S., Koç M., Karaçam A., Canlı U., Engin H., et al. (2025). Cluster set vs. traditional set in plyometric training: effect on the athletic performance of youth football players. Appl. Sci. 15 (3), 1282. doi:10.3390/app15031282

Pääsuke M., Ereline J., Gapeyeva H. (2001). Knee extensor muscle strength and vertical jumping performance characteristics in pre-and post-pubertal boys. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 13 (1), 60–69. doi:10.1123/pes.13.1.60

Padrón-Cabo A., Lorenzo-Martínez M., Pérez-Ferreirós A., Costa P. B., Rey E. (2021). Effects of plyometric training with agility ladder on physical fitness in youth soccer players. Int. J. Sports Med. 42 (10), 896–904. doi:10.1055/a-1308-3316

Paes P. P., Correia G. A. F., Damasceno V. D. O., Lucena E. V. R., Alexandre I. G., Da Silva L. R., et al. (2022). Effect of plyometric training on sprint and change of direction speed in young basketball athletes. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 22 (2), 305–310. doi:10.7752/jpes.2022.02039

Palma-Muñoz I., Ramírez-Campillo R., Azocar-Gallardo J., Álvarez C., Asadi A., Moran J., et al. (2021). Effects of progressed and nonprogressed volume-based overload plyometric training on components of physical fitness and body composition variables in youth male basketball players. J. Strength and Cond. Res. 35 (6), 1642–1649. doi:10.1519/jsc.0000000000002950

Passos P., Araújo D., Volossovitch A. (2017). Performance analysis in team sports. London, UK: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group.

Rædergård H. G., Falch H. N., Tillaar R. v.d. (2020). 'Effects of strength vs. plyometric training on change of direction performance in experienced soccer players. Sports 8 (11), 144. doi:10.3390/sports8110144

Radnor J. M., Oliver J. L., Waugh C. M., Myer G. D., Moore I. S., Lloyd R. S. (2018). The influence of growth and maturation on stretch-shortening cycle function in youth. Sports Med. 48 (1), 57–71. doi:10.1007/s40279-017-0785-0

Ramirez-Campillo R., Alvarez C., García-Pinillos F., Sanchez-Sanchez J., Yanci J., Castillo D., et al. (2018). Optimal reactive strength index: is it an accurate variable to optimize plyometric training effects on measures of physical fitness in young soccer players? J. Strength and Cond. Res. 32 (4), 885–893. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002467

Ramirez-Campillo R., Alvarez C., García-Pinillos F., Gentil P., Moran J., Pereira L. A., et al. (2019). Effects of plyometric training on physical performance of young male soccer players: potential effects of different drop jump heights. Pediatr. Exercise Science 31 (3), 306–313. doi:10.1123/pes.2018-0207

Ramirez-Campillo R., Álvarez C., García-Pinillos F., García-Ramos A., Loturco I., Chaabene H., et al. (2020a). Effects of combined surfaces vs. single-surface plyometric training on soccer players' physical fitness. J. Strength and Cond. Res. 34 (9), 2644–2653. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002929

Ramirez-Campillo R., Alvarez C., Gentil P., Loturco I., Sanchez-Sanchez J., Izquierdo M., et al. (2020b). Sequencing effects of plyometric training applied before or after regular soccer training on measures of physical fitness in young players. J. Strength and Cond. Res. 34 (7), 1959–1966. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002525

Ramirez-Campillo R., Sortwell A., Moran J., Afonso J., Clemente F. M., Lloyd R. S., et al. (2023). Plyometric-jump training effects on physical fitness and sport-specific performance according to maturity: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Sports Medicine-Open 9 (1), 23. doi:10.1186/s40798-023-00568-6

Ross A., Leveritt M., Riek S. (2001). Neural influences on sprint running: training adaptations and acute responses. Sports Medicine 31 (6), 409–425. doi:10.2165/00007256-200131060-00002

Şahin F. B., Kafkas A. Ş., Kafkas M. E., Taşkapan M. Ç., Jones A. M. (2022). The effect of active vs passive recovery and use of compression garments following a single bout of muscle-damaging exercise. Isokinet. Exerc. Sci. 30 (2), 117–126. doi:10.3233/ies-210155

Sammoud S., Negra Y., Bouguezzi R., Ramirez-Campillo R., Moran J., Bishop C., et al. (2024). Effects of plyometric jump training on measures of physical fitness and lower-limb asymmetries in prepubertal male soccer players: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabilitation 16 (1), 37. doi:10.1186/s13102-024-00821-9

Sankey S. P., Jones P. A., Bampouras T. (2008). Effects of two plyometric training programmes of different intensity on vertical jump performance in high school athletes. Serbian Journal Sports Sciences 2 (4), 123–130.

Sanpasitt C., Yongtawee A., Noikhammueang T., Likhitworasak D., Woo M. (2023). Anthropometric and physiological predictors of soccer skills in youth soccer players. Phys. Educ. Theory Methodol. 23 (5), 678–685. doi:10.17309/tmfv.2023.5.04

Schoenfeld B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. J. Strength and Cond. Res. 24 (10), 2857–2872. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e840f3

Sedano S., Matheu A., Redondo J., Cuadrado G. (2011). Effects of plyometric training on explosive strength, acceleration capacity and kicking speed in young elite soccer players. J. Sports Medicine Physical Fitness 51 (1), 50–58.

Seiberl W., Hahn D., Power G. A., Fletcher J. R., Siebert T. (2021). The stretch-shortening cycle of active muscle and muscle-tendon complex: what, why and how it increases muscle performance?. Front. Physiol. 12. doi:10.3389/fphys.2021.693141

Sheppard J. M., Young W. B. (2006). Agility literature review: classifications, training and testing. J. Sports Sciences 24 (9), 919–932. doi:10.1080/02640410500457109

Shepstone T. N., Tang J. E., Dallaire S., Schuenke M. D., Staron R. S., Phillips S. M. (2005). Short-term high-vs. Low-velocity isokinetic lengthening training results in greater hypertrophy of the elbow flexors in young men. J. Applied Physiology 98 (5), 1768–1776. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01027.2004

Silva A. F., Ramirez-Campillo R., Ceylan H. İ., Sarmento H., Clemente F. M. (2022). Effects of maturation stage on sprinting speed adaptations to plyometric jump training in youth male team sports players: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Access Journal Sports Medicine 13, 41–54. doi:10.2147/OAJSM.S283662

Slimani M., Chamari K., Miarka B., Del Vecchio F. B., Cheour F. (2016). Effects of plyometric training on physical fitness in team sport athletes: a systematic review. J. Human Kinetics 53, 231–247. doi:10.1515/hukin-2016-0026

Stojanović E., Ristić V., McMaster D. T., Milanović Z. (2017). Effect of plyometric training on vertical jump performance in female athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 47 (5), 975–986. doi:10.1007/s40279-016-0634-6

Stølen T., Chamari K., Castagna C., Wisløff U. (2005). Physiology of soccer: an update. Sports Medicine 35 (6), 501–536. doi:10.2165/00007256-200535060-00004

Sun J., Sun J., Shaharudin S., Zhang Q. (2025). Effects of plyometrics training on lower limb strength, power, agility, and body composition in athletically trained adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 34146. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-10652-4

Taube W., Leukel C., Gollhofer A. (2012). How neurons make us jump: the neural control of stretch-shortening cycle movements. Exerc. Sport Sciences Reviews 40 (2), 106–115. doi:10.1097/JES.0b013e31824138da

Taylor J. B., Wright A. A., Dischiavi S. L., Townsend M. A., Marmon A. R. (2017). Activity demands during multi-directional team sports: a systematic review. Sports Medicine 47 (12), 2533–2551. doi:10.1007/s40279-017-0772-5

Tomalka A., Weidner S., Hahn D., Seiberl W., Siebert T. (2020). Cross-bridges and sarcomeric non-cross-bridge structures contribute to increased work in stretch-shortening cycles. Front. Physiology 11, 921. doi:10.3389/fphys.2020.00921

Tumkur Anil Kumar N., Oliver J. L., Lloyd R. S., Pedley J. S., Radnor J. M. (2021). The influence of growth, maturation and resistance training on muscle-tendon and neuromuscular adaptations: a narrative review. Sports 9 (5), 59. doi:10.3390/sports9050059

Türkarslan B., Deliceoglu G. (2024). The effect of plyometric training program on agility, jumping, and speed performance in young soccer players. Pedagogy Phys. Cult. Sports 28 (2), 116–123. doi:10.15561/26649837.2024.0205

Unnithan V., White J., Georgiou A., Iga J., Drust B. (2012). Talent identification in youth soccer. J. Sports Sciences 30 (15), 1719–1726. doi:10.1080/02640414.2012.731515

Vera-Assaoka T., Ramirez-Campillo R., Alvarez C., Garcia-Pinillos F., Moran J., Gentil P., et al. (2020). Effects of maturation on physical fitness adaptations to plyometric drop jump training in male youth soccer players. J. Strength and Cond. Res. 34 (10), 2760–2768. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000003151

Wagner H., Finkenzeller T., Würth S., Von Duvillard S. P. (2014). Individual and team performance in team-handball: a review. J. Sports Science and Medicine 13 (4), 808–816.

Wang X., Zhang K., bin Samsudin S., bin Hassan M. Z., bin Yaakob S. S. N., Dong D. (2024). Effects of plyometric training on physical fitness attributes in handball players: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sports Science and Medicine 23 (1), 177–195. doi:10.52082/jssm.2024.177

Ziv G., Lidor R. (2009). Physical characteristics, physiological attributes, and on-court performances of handball players: a review. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 9 (6), 375–386. doi:10.1080/17461390903038470

Zribi A., Zouch M., Chaari H., Bouajina E., Nasr H. B., Zaouali M., et al. (2014). Short-term lower-body plyometric training improves whole-body BMC, bone metabolic markers, and physical fitness in early pubertal male basketball players. Pediatr. Exercise Science 26 (1), 22–32. doi:10.1123/pes.2013-0053

Keywords: adolescents, athletic performance, physical fitness, plyometric training, team sports

Citation: Zhang F, Liu Y, Liu J, Yeremenko O and Shi L (2026) The effects of plyometric training on physical fitness in adolescent team sports: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 17:1760239. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2026.1760239

Received: 03 December 2025; Accepted: 06 January 2026;

Published: 21 January 2026.

Edited by:

Souhail Hermassi, Qatar University, QatarReviewed by:

Thomas Jones, Northumbria University, United KingdomLunxin Chen, Central China Normal University, China

Copyright © 2026 Zhang, Liu, Liu, Yeremenko and Shi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lei Shi, c2hpbGVpMDAwOTIzQDE2My5jb20=

Fengming Zhang

Fengming Zhang Yang Liu1

Yang Liu1