- 1 Center of Environmental Intelligence, VinUniversity, Hanoi, Vietnam

- 2 Faculty of Mathematics and Informatics, Hanoi University of Science and Technology, Hanoi, Vietnam

- 3 College of Engineering and Computer Science, VinUniversity, Hanoi, Vietnam

Introduction: High-resolution satellite imagery is essential for environmental monitoring, land-use assessment, and disaster management, particularly in Southeast Asia—a region marked by ecological diversity, rapid urbanization, and climate vulnerability. However, the limited spatial resolution of several key spectral bands in widely used platforms such as Sentinel-2 constrains fine-scale analysis, especially in resource-limited contexts.

Methods: To overcome these limitations, we develop an enhanced deep learning–based super-resolution framework that extends the DSen2 architecture through two dedicated components: a High-Pass Frequency (HPF) enhancement layer designed to better recover fine spatial details, and a Channel Attention (CA) mechanism that adaptively prioritizes the most informative spectral bands. The model is trained and evaluated on a geographically diverse Sentinel-2 dataset covering 30 regions across Vietnam, serving as a representative case study for Southeast Asian landscapes.

Results: Quantitative evaluation using Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) shows that the proposed framework consistently outperforms bicubic interpolation and the original DSen2 model. The most substantial improvements are observed in the red-edge and shortwave infrared (SWIR) bands, which are critical for vegetation and land-surface analysis.

Discussion: The performance gains achieved by the proposed model translate into more accurate and operationally useful high-resolution imagery for downstream applications, including vegetation health monitoring, water resource assessment, and urban change detection. Overall, the method provides a scalable and computationally efficient approach for enhancing Sentinel-2 data quality, with Vietnam serving as a practical benchmark for broader deployment across Southeast Asia.

1 Introduction

Satellite remote sensing has become a cornerstone of environmental monitoring and geospatial analysis, providing a synoptic, scalable, and cost-effective means to observe changes in land cover, climate, and resource distribution. In Southeast Asia—a region characterized by dense vegetation, fragmented landscapes, dynamic hydrological systems, and rapid urbanization, such technologies are especially critical for addressing challenges in agricultural productivity, forest conservation, water management, and disaster preparedness.

Among available platforms, the Sentinel-2 Earth observation mission, part of the European Space Agency’s Copernicus program, stands out as one of the most accessible and versatile systems for regional-scale assessment. Sentinel-2 provides 13 multispectral bands at spatial resolutions of 10 m, 20 m, and 60 m, with a revisit frequency of approximately 5 days. This combination of spectral richness and temporal density makes it highly suitable for operational applications requiring frequent and multi-spectral coverage. However, a key limitation lies in the inconsistent spatial resolution across its bands. While visible and near-infrared bands (B2, B3, B4, B8) are captured at 10 m, critical bands for vegetation monitoring (B5–B7), land moisture estimation (B11–B12), and atmospheric analysis (B1, B9) are only available at 20 or 60 m. This spatial disparity complicates integrated spectral analyses and reduces the effectiveness of data-driven environmental monitoring at finer scales.

The challenge is particularly acute in countries such as Vietnam, where ecological complexity—ranging from highland forests and riverine deltas to coastal wetlands—requires high-resolution observation, yet access to commercial high-resolution imagery is limited by cost and infrastructure barriers. Consequently, there is an urgent need for scalable, learning-based approaches that can enhance the spatial resolution of freely available multispectral satellite data such as Sentinel-2.

Deep learning has demonstrated strong potential in this domain, particularly through Single-Image Super-Resolution (SISR) models. Architectures based on deep residual networks (Wagner et al., 2019; Liebel and Korner, 2016) and generative adversarial frameworks (Salgueiro Romero et al., 2020) have shown the ability to reconstruct fine spatial details from low-resolution inputs. However, SISR methods often struggle to generalize across highly diverse landscapes and may introduce synthetic artifacts in the absence of physical priorities or when spectral complexity is high. Alternatively, Multi-Image Super-Resolution (MISR) techniques exploit temporal redundancy or multi-angle acquisitions (Kawulok et al., 2021; Bordone Molini et al., 2020; Valsesia and Magli, 2022; Deudon et al., 2020; Rifat Arefin et al., 2020; Salvetti et al., 2020), but their effectiveness is limited by cloud cover, inconsistent revisit intervals, and image misalignment—challenges that are especially pronounced in tropical regions.

Another limitation of many existing approaches is the uniform treatment of spectral bands, despite the heterogeneous information content across wavelengths. Red-edge and shortwave infrared (SWIR) bands, for instance, provide critical insights into vegetation stress and soil moisture, yet they are often underutilized in conventional super-resolution frameworks. This lack of spectral adaptivity and insufficient preservation of spatial detail restricts the applicability of current models in complex environments such as Southeast Asia.

To address these challenges, we propose a novel super-resolution framework that extends the DSen2 architecture (Lanaras et al., 2018), a state-of-the-art deep learning model designed for Sentinel-2 imagery. Two key enhancements are introduced: a High-Pass Frequency (HPF) module that emphasizes and preserves fine-grained spatial structures, and a Channel Attention (CA) mechanism, inspired by squeeze-and-excitation networks (Hu et al., 2018a), which adaptively weights spectral channels according to their contextual relevance. Together, these modules enable the model to more effectively recover object boundaries, textures, and spectral nuances essential for land-based applications.

To validate the proposed approach, we constructed a geographically and ecologically diverse dataset of Sentinel-2 imagery from 30 regions across Vietnam, covering a broad range of terrain types, vegetation structures, and climatic conditions. The model was trained and evaluated on this dataset, and its performance was benchmarked against bicubic interpolation and the original DSen2 model using Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) metrics. Results show consistent improvements across all target bands, with particularly strong gains in the red-edge and SWIR regions that are critical for vegetation and moisture analysis.

The contributions of this work lie not only in advancing the technical architecture of Sentinel-2 super-resolution but also in demonstrating its practical potential for scalable deployment across Southeast Asia. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work on deep super-resolution and attention mechanisms; Section 3 describes the dataset and the proposed architecture, including the integration of HPF and CA modules; Section 4 presents the experimental setup, results, and comparative evaluations; and Section 5 concludes the paper with a summary and future research directions.

2 Related work

The enhancement of satellite imagery through super-resolution (SR) techniques has received significant attention in recent years, particularly in the context of Earth observation missions such as Sentinel-2. Broadly, SR methods for remote sensing can be categorized into three groups: single-image super-resolution (SISR), multi-image super-resolution (MISR), and hybrid approaches that integrate attention mechanisms or fusion strategies to improve feature representation.

2.1 Single-image super-resolution (SISR)

SISR methods aim to reconstruct a high-resolution (HR) image from a single low-resolution (LR) input. Early convolutional neural network (CNN) models such as SRCNN and VDSR demonstrated the potential of deep learning for this task, with subsequent residual learning strategies (e.g., EDSR and its multispectral adaptation for Sentinel-2 (Wagner et al., 2019; Liebel and Korner, 2016)) further improving performance by emphasizing high-frequency components. Generative adversarial networks (GANs) have also been applied to SISR, with models such as SRGAN and its variants (Salgueiro Romero et al., 2020) producing sharper textures and more realistic details. However, SISR approaches inherently rely on limited spatial context, which often leads to synthetic artifacts and degraded accuracy in structurally complex or information-scarce regions.

2.2 Multi-image super-resolution (MISR)

To overcome these limitations, MISR approaches leverage temporal or cross-sensor redundancy to improve reconstruction quality. These methods combine information from multiple co-registered LR images acquired at different times or spectral bands, thereby reducing uncertainty and enhancing spatial detail. CNN-based frameworks such as those by Kawulok et al. (Kawulok et al., 2021) and DeepSUM++ (Bordone Molini et al., 2020) exploit temporal sequences to learn robust spatial patterns. Other techniques, such as those by Valsesia and Magli. (2022), incorporate permutation invariance to effectively handle unordered inputs. HighRes-Net (Deudon et al., 2020) demonstrates recursive temporal fusion, while RNN-based models (Rifat Arefin et al., 2020) aggregate latent representations to process variable-length input sequences. These approaches have achieved notable results on benchmarks such as Proba-V. In addition, residual attention-based models (e.g., Salvetti et al. (2020) highlight the benefits of selectively emphasizing salient features during multi-frame aggregation.

2.3 Spectral-domain fusion

Beyond temporal fusion, spectral-domain fusion has become an important strategy, particularly in pan-sharpening and hyperspectral–multispectral integration. Several studies (Yang et al., 2022; Sara et al., 2021) have developed deep learning frameworks to merge hyperspectral (HS) and multispectral (MS) data, thereby enhancing both spatial and spectral resolution. Methods such as Pannet (Yang et al., 2017) and deep pan-sharpening networks (Huang et al., 2015) employ high-resolution panchromatic imagery to guide the upsampling of MS data, achieving improved spectral fidelity and spatial accuracy. More recently, hybrid approaches have combined temporal and spectral fusion to exploit complementary information across modalities (Tarasiewicz et al., 2023).

2.4 Attention mechanisms

A major advancement in deep SR has been the introduction of attention mechanisms, which allow networks to adaptively focus on the most informative features. Originally developed for image captioning (Xu et al., 2015), attention has since been widely adopted in computer vision. Channel attention mechanisms, such as the Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) blocks by Hu et al. (2018a), assign per-channel importance via global average pooling and bottleneck MLPs, enabling networks to selectively emphasize meaningful spectral features. Spatial attention mechanisms (Hu et al., 2018b; Park et al., 2018; Fu et al., 2019) refine feature maps by focusing on relevant regions, while combined spatial–channel attention, as implemented in RCAN (Zhang et al., 2018), has proven highly effective for SR tasks by enabling deep residual networks to selectively process high-value features.

2.5 Gaps in existing work

Despite these advances, the application of attention-based super-resolution to Sentinel-2 imagery remains relatively limited. Most existing models are trained on globally curated datasets with insufficient representation of ecologically complex and data-sparse regions such as Vietnam. Moreover, the joint integration of attention mechanisms with frequency-domain enhancement—specifically high-pass filtering—within a unified SR framework for multispectral remote sensing has not been systematically explored.

2.6 Our contribution

This study builds on these insights by extending the DSen2 model (Lanaras et al., 2018) with two complementary modules: a Channel Attention (CA) mechanism to improve spectral adaptivity, and a High-Pass Frequency (HPF) module to enhance spatial detail preservation. Together, these innovations address both spectral selectivity and spatial fidelity in a single-image SR context, enabling more accurate reconstruction of 20 m Sentinel-2 bands at 10 m resolution and supporting finer-scale environmental analysis where access to commercial high-resolution imagery is limited.

3 Methods

This section presents the methodology, which consists of two main components: (1) the construction of a geographically diverse and ecologically representative Sentinel-2 dataset covering Vietnam, and (2) the development of an enhanced deep neural network architecture for multispectral image super-resolution. The framework extends the DSen2 backbone (Lanaras et al., 2018) by integrating high-pass frequency (HPF) enhancement and channel attention (CA) mechanisms, thereby improving spatial detail recovery and spectral consistency.

3.1 Dataset

To train and evaluate the framework, we created a large-scale dataset using Sentinel-2 Level-1C imagery obtained from the ESA Copernicus Open Access Hub. Thirty spatially disjoint regions across Vietnam were selected to capture a wide range of terrain types, ecological zones, and climatic conditions, including mountainous northern areas, the central highlands, coastal plains, and the Mekong Delta. This diversity ensures that the dataset reflects both natural ecosystems and human-modified landscapes, making it suitable for assessing model generalizability.

Each region spans approximately 110 × 110 km2, with acquisitions collected between January 2023 and January 2024. Sentinel-2 provides 13 multispectral bands at three native resolutions: 10 m (B2, B3, B4, B8), 20 m (B5–B7, B8A, B11, B12), and 60 m (B1, B9). Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of selected regions.

Figure 1. Example Sentinel-2 imagery from 30 regions across Vietnam used for training and validation. The sites span diverse landscapes, including mountains, highlands, coastal plains, and the Mekong Delta, ensuring ecological and geographic diversity for model evaluation.

The imagery was segmented into 32 × 32 patches, resulting in 168,000 training samples and 16,800 validation samples. Nine additional regions were held out as an independent test set to evaluate performance under previously unseen geographic and ecological conditions. Preprocessing included cloud masking, bilinear interpolation for band alignment, and reflectance normalization. Importantly, the train–test split ensures no geographic overlap, avoiding spatial leakage and providing a rigorous evaluation setting.

3.2 Proposed model

The proposed architecture builds upon the DSen2 model (Lanaras et al., 2018), which uses deep residual learning to upscale lower-resolution bands with guidance from higher-resolution counterparts. We extend this baseline with two modules: a High-Pass Frequency (HPF) block that emphasizes fine spatial structures, and a Channel Attention (CA) mechanism that adaptively weights spectral information. The overall architecture is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. DSen2 architecture for upscaling 20 m Sentinel-2 bands to 10 m. The 20 m inputs are upsampled and concatenated with 10 m bands, then processed through convolution, ReLU, and multiple residual blocks. A final convolution and residual addition generate the super-resolved outputs.

3.3 DSen2 backbone

DSen2 employs a two-stage residual learning process. First, the 20 m bands are upsampled to 10 m using spatial guidance from the 10 m bands. Second, the 60 m bands are upsampled to 10 m using features from all resolutions. The design is derived from EDSR (Lim et al., 2017), removing batch normalization for more efficient residual learning.

Formally, for 2× upsampling:

The transformation is learned through:

Similarly, for 6× upsampling from 60 m bands:

where

3.4 High-pass frequency enhancement

Super-resolution models often struggle with reconstructing high-frequency details such as object edges, fine textures, and thin structures. To address this, we introduce a high-pass filtering layer that isolates and amplifies the spatial frequency components responsible for these features. By suppressing the low-frequency background information and enhancing rapid intensity changes, high-pass filtering helps the model focus on edges and fine patterns. This allows the network to better preserve structural details that are typically lost in standard reconstruction processes.

The HPF module operates by computing the residual between the input image and a smoothed version of itself (e.g., via Gaussian or low-pass filtering). This isolates detail-rich regions such as boundaries between vegetation types, urban features, and water bodies. By injecting this high-frequency signal into the residual blocks, the network is guided to preserve and enhance spatial details that would otherwise be lost during upsampling.

As depicted in Figure 2, the HPF module is integrated early into the pipeline, enabling frequency-aware learning from the outset of training. This improves the network’s ability to reconstruct intricate structures such as river boundaries, agricultural plots, and building edges—features that are especially important in heterogeneous regions like Vietnam.

3.5 Channel attention mechanism

Multispectral data exhibits significant variation in the information content and relevance of each spectral band. For example, red-edge bands are critical for vegetation classification, while SWIR bands contribute to soil and moisture analysis. To exploit this variability, we embed a channel attention mechanism into each residual block of the network.

The fundamental concept of channel attention is to enable the model to assign varying levels of importance to different feature channels, rather than treating them uniformly in the generation of output feature maps (as shown in Figure 3). Specifically, the mechanism adaptively emphasizes channels that contain more discriminative or informative representations, while suppressing those that contribute less. This process is often described as a “squeeze-and-excitation” operation, wherein the information is first aggregated to capture the relative significance of each channel and then selectively reweighted to enhance the most relevant ones.

Figure 3. Channel Attention (CA) layer. Global average pooling (AvgPool) compresses the input feature map into a channel descriptor, which is passed through a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) to generate channel-wise attention weights.

Inspired by the squeeze-and-excitation architecture (Hu et al., 2018a), the module first applies global average pooling to condense spatial information into a 1D descriptor vector across channels. This is followed by a bottleneck fully connected network with non-linear activation, which outputs channel-wise weights after sigmoid activation. These weights are then used to re-scale the input features by emphasizing informative channels and attenuating less relevant ones.

Mathematically, for an input feature map

where GAP denotes global average pooling, W 1 and W 2 are trainable matrices, and σ is the sigmoid function.

The reweighted feature map is then computed as

In conclusion, the proposed framework extends DSen2 by jointly integrating frequency-domain enhancement (HPF) and spectral adaptivity (CA) within a residual learning structure. These innovations enable the model to recover sharp textures and emphasize the most informative bands, thereby producing high-fidelity reconstructions from lower-resolution Sentinel-2 imagery. Coupled with a geographically diverse dataset (Figure 1), the method is designed to generalize across heterogeneous landscapes, with particular effectiveness in ecologically and structurally complex regions such as Vietnam.

4 Experimental results

4.1 Implementation details

The proposed super-resolution framework is implemented in PyTorch, chosen for its flexibility in designing custom deep learning architectures and its robust support for GPU-accelerated training. Both training and inference are performed on a high-performance computing system equipped with two NVIDIA RTX A5000 GPUs, each with 24 GB of VRAM, which enables efficient handling of large-scale datasets and deep neural networks without memory bottlenecks. This setup allows for parallelized computation, reducing training time while supporting extensive hyperparameter tuning and ablation studies.

4.2 Dataset handling and patch generation

The dataset used for model development consists of 30 Sentinel-2 scenes across Vietnam, selected to capture a wide spectrum of land cover types, ecological zones, and atmospheric conditions. To prepare the data for training, each full-size Sentinel-2 scene is segmented into smaller, non-overlapping image patches of 32 × 32 pixels extracted from the 20 m bands. This patch-based strategy ensures manageable input sizes for the network while increasing the number of training samples, thereby improving convergence stability and computational efficiency. In total, 168,000 patches are used for training and 16,800 patches for validation, as summarized in Table 1. The approach also promotes better generalization, as the network is exposed to diverse local structures and spectral variations.

4.3 Model architecture and integration of enhancements

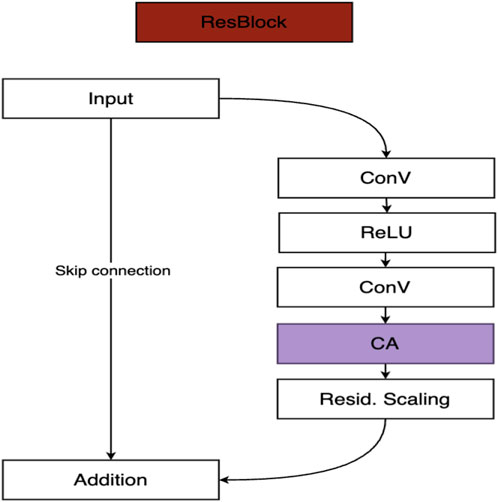

The proposed network extends the baseline DSen2 architecture (Lanaras et al., 2018) by embedding two complementary modules: a High-Pass Frequency (HPF) filtering layer and a Channel Attention (CA) mechanism. These modules are integrated within the residual blocks of the backbone, forming an enhanced ResBlock structure, as illustrated in Figure 4. Together, they enable the model to more effectively recover fine spatial structures while adaptively weighing spectral information.

Figure 4. Proposed ResBlock architecture. The block consists of two convolutional layers with ReLU activation, followed by a Channel Attention (CA) module and residual scaling. A skip connection enables residual learning, preserving low-frequency information while enhancing high-frequency details.

The HPF module is designed to extract and emphasize high-frequency spatial components such as edges, fine textures, and object boundaries. These features are often lost during conventional upsampling, leading to oversmoothed reconstructions. By isolating and amplifying rapid intensity variations, the HPF module ensures that the network maintains sharper boundaries and finer structural details—an essential capability for accurately representing heterogeneous landscapes in Sentinel-2 imagery.

The Channel Attention module, on the other hand, addresses the unequal contribution of different spectral bands. Implemented via a global pooling and weighting strategy, it computes channel-wise importance scores that allow the model to adaptively emphasize the most informative spectral channels while attenuating less relevant ones. This adaptivity is particularly critical in multispectral remote sensing, where red-edge bands contribute strongly to vegetation monitoring and SWIR bands provide vital information on soil moisture and mineral content. By dynamically prioritizing such channels, the CA module enhances both spectral fidelity and task-specific relevance.

Together, these architectural enhancements align spatial and spectral modeling within a unified residual learning framework, enabling the network to generate sharper, more context-aware super-resolved outputs compared to the original DSen2 design.

4.4 Training configuration

The model was trained using Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) with a momentum parameter of 0.9 to stabilize updates and accelerate convergence. The initial learning rate was set to 1 × 10−4 and adjusted dynamically through a step-based scheduling strategy: whenever the validation loss failed to decrease for five consecutive epochs, the learning rate was reduced by a factor of two. This adaptive scheduling ensured steady convergence while preventing stagnation during later training stages.

Training was performed with a batch size of 128, utilizing both GPUs in parallel to maximize throughput and efficiency. The full training process ran for approximately 150 epochs, completing in under 24 h on the dual-GPU system.

To enhance model robustness and mitigate overfitting, on-the-fly data augmentation was applied. Augmentation operations included random horizontal and vertical flips, random rotations, and brightness/contrast adjustments, which increased sample diversity and improved the model’s ability to generalize across heterogeneous landscapes.

4.5 Loss function and evaluation strategy

The model was trained using the Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss, selected for its consistency with the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) metric employed during evaluation. MSE was computed separately for each spectral band and then averaged across all bands, ensuring that the loss function accurately reflected overall reconstruction quality while maintaining sensitivity to band-specific variations.

For evaluation on full-size Sentinel-2 tiles, we adopted a sliding window strategy to super-resolve the images. Overlapping patches were reconstructed and then stitched together using weighted averaging, which effectively reduced boundary discontinuities and edge artifacts.

Performance was benchmarked against two baselines: bicubic interpolation, representing a non-learning standard, and the original DSen2 model, representing a state-of-the-art deep learning baseline. Comparative results and detailed analysis of the proposed framework against these methods are presented in Section 4.3.

4.6 Evaluation metric

To quantitatively evaluate the performance of the proposed super-resolution framework, we employed the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) as the primary metric. RMSE is widely adopted in remote sensing and image reconstruction tasks because it is directly interpretable in the physical domain of reflectance values and is highly sensitive to pixel-level differences between predicted and reference high-resolution images.

Given a predicted image

This metric captures the average magnitude of reconstruction error per pixel. It is computed independently for each spectral band, with lower RMSE values indicating higher reconstruction accuracy and better preservation of both spatial and spectral details.

In line with prior work on Sentinel-2 super-resolution (e.g., DSen2 (Lanaras et al., 2018)), we report RMSE at two levels:

Per-band RMSE: to assess reconstruction fidelity of individual spectral channels.

Average RMSE across bands: to summarize overall model performance.

All evaluations were conducted on the held-out test set consisting of nine full Sentinel-2 scenes. To mitigate boundary artifacts and ensure fairness in comparison, a sliding window strategy with overlapping patches was used during testing, and overlapping predictions were merged using weighted averaging.

Although alternative evaluation metrics such as Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and the Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM) are often used in computer vision tasks, they are less common in remote sensing. PSNR is closely related to RMSE and mainly emphasizes global pixel fidelity, while SSIM captures perceptual quality and structural similarity. However, both are less directly interpretable in the context of multispectral data, where the absolute magnitude of error per spectral band is critical for downstream quantitative applications (e.g., vegetation indices, moisture retrieval). For this reason, RMSE was chosen as the primary evaluation metric to ensure consistency with prior work and practical relevance to Earth observation tasks.

4.7 Comparison with baseline methods

Table 2 summarizes the RMSE values for bicubic interpolation, DSen2, and the proposed variants across the 20 m Sentinel-2 bands. The results reveal substantial performance differences, underscoring both the limitations of interpolation-based methods and the effectiveness of the proposed enhancements.

Table 2. Per-band RMSE values for 2× upsampling. Results are averaged over all test images, evaluated with 40 m input and 20 m output resolution. Best results are highlighted in bold.

4.8 Bicubic interpolation

Bicubic interpolation performs the weakest, with an average RMSE of 131.48, nearly four times higher than any learning-based method. Errors are consistently large across all bands, especially in B7 (143.82) and B8a (157.50), which are sensitive to fine structural details such as vegetation edges and urban boundaries. These results highlight the fundamental limitations of interpolation-based approaches, which fail to recover high-frequency content and instead generate oversmoothed reconstructions that obscure critical spatial and spectral information.

4.9 DSen2

In contrast, DSen2 achieves a dramatic improvement, reducing the average RMSE to 34.70. Its strongest performance is observed in the red-edge bands B5 (23.25) and B6 (30.65), confirming its ability to effectively reconstruct features relevant to vegetation monitoring. However, the model struggles in B8a, B11, and B12, where RMSE values exceed 38.0. These spectral ranges are strongly influenced by atmospheric effects and sub-pixel heterogeneity. Since DSen2 treats all channels equally, it lacks the ability to prioritize more informative bands, limiting its effectiveness in these challenging regions.

4.10 Ablation variants

The ablation experiments demonstrate that neither module alone is sufficient to surpass DSen2.

• HPF-only variant: Achieves an average RMSE of 34.94, slightly worse than DSen2. While it improves edge sharpness in some cases, it also amplifies noise, particularly in B6, B8a, and B12.

• CA-only variant: Obtains an average RMSE of 34.85, showing improvements in B6 and B7 but worse results in B8a and B11. Channel reweighting alone improves spectral adaptivity but fails to adequately recover high-frequency spatial structures, sometimes suppressing important edge features.

These findings indicate that the modules complement one another: HPF enhances structural detail, while CA ensures spectral adaptivity.

The Proposed Method: Advancing DSen2 with HPF and Channel Attention.

The full proposed model combines the High-Pass Frequency (HPF) module with the Channel Attention (CA) mechanism, thereby addressing two complementary limitations of existing super-resolution approaches: the inability to fully preserve fine spatial details and the lack of adaptivity across spectral bands. By integrating both modules within the residual learning framework of DSen2, the proposed architecture achieves superior reconstruction accuracy, with an average RMSE of 32.95, the lowest among all tested methods.

Performance gains are observed across most bands, with particularly notable improvements in regions critical for environmental applications:

• B6 (red-edge, vegetation monitoring): RMSE decreases from 30.65 (DSen2) to 28.60, improving sensitivity to subtle variations in canopy structure and vegetation health.

• B12 (SWIR, soil and moisture analysis): RMSE decreases from 38.97 (DSen2) to 36.00, enhancing the model’s ability to capture soil moisture gradients and water content variability.

• Overall average: Reduced from 34.70 (DSen2) to 32.95, reflecting consistent improvements across diverse spectral ranges.

While the absolute reductions in RMSE may seem numerically modest, their significance lies in the high-dimensional and application-driven nature of multispectral super-resolution. In practice, even small improvements at the sub-pixel level can strongly influence downstream analyses such as:

Land-cover classification, where sharper boundaries between vegetation types, urban areas, and water bodies improve accuracy.

Object segmentation, where fine details such as field boundaries or narrow rivers are better preserved.

Biophysical variable retrieval, where accurate reconstruction of red-edge and SWIR bands enhances the reliability of vegetation indices, canopy water content estimation, and soil characterization.

Visual inspections, presented in Figures 5, 6, further reinforce these findings. The proposed model produces sharper spatial structures, clearer boundaries, and fewer artifacts compared to bicubic interpolation and other variants. For instance, riverbanks, agricultural plots, and built-up areas appear more distinct, confirming that the integration of HPF and CA effectively balances structural fidelity with spectral adaptivity.

Figure 5. Visual comparison of the proposed model and bicubic interpolation on bands B6 and B12 in Vietnam region. The first row shows the comparison in the B6 band, while the second row presents the comparison in the B12 band. In Figure 5 the proposed model (second column) reconstructs sharper spatial structures, with well-defined river boundaries and more distinct bright features. In contrast, bicubic interpolation (third column) retains overall large-scale structures but fails to recover smooth transitions and fine details. Figures 6, 7 show absolute error maps for band B6 (top) and band B12 (bottom) comparing the proposed model and bicubic interpolation in the Vietnam and Siberia regions, respectively.

Figure 6. Absolute error maps for band B6 (top) and band B12 (bottom) in the Vietnam region. The left column shows the error maps for the super-resolution (SR) model, while the right column shows those for bicubic interpolation.

The improvements achieved here highlight an important observation: HPF and CA are complementary rather than redundant. HPF enhances edge sharpness and recovers high-frequency spatial information that convolutional layers tend to suppress, while CA adaptively reweights spectral channels, ensuring that critical bands such as red-edge and SWIR are prioritized in the reconstruction. Only when combined do these mechanisms yield consistent improvements across both spatial and spectral domains.

In summary, the proposed enhancements advance the DSen2 architecture by explicitly addressing its two major limitations. The resulting framework achieves higher accuracy, stronger structural fidelity, and improved spectral consistency across diverse Sentinel-2 bands. This positions the model as not only a technical improvement over existing baselines but also a practical tool for real-world remote sensing applications, particularly in resource-limited settings where access to commercial high-resolution imagery remains restricted.

4.11 Interpretability and practical implications

Beyond quantitative improvements, the proposed framework has strong implications for real-world applications. Enhanced reconstruction accuracy translates into more reliable inputs for environmental monitoring, land cover mapping, and precision agriculture. This is particularly valuable in Vietnam and other regions where access to high-resolution commercial imagery is limited.

• Agriculture: Sharper delineation of field boundaries in red-edge bands (B6, B7) improves crop segmentation and yield estimation.

• Forestry: Improved reconstruction of SWIR bands (B11, B12) enhances canopy moisture detection, supporting fire risk assessment and forest health monitoring.

• Urban studies: Enhanced texture recovery improves the distinction between built-up structures and surrounding vegetation, aiding urban sprawl analysis and land-use planning.

A key advantage of the proposed approach lies in its generalizability. By relying on adaptive spectral weighting and frequency-aware feature extraction, rather than handcrafted features or scene-specific priors, the framework demonstrates robustness across diverse landscapes, geographies, and seasonal conditions. This adaptability makes it well-suited for integration into operational Earth observation pipelines where scalability and transferability are essential.

4.12 Visual performance analysis

The visual comparisons in Figures 5–7 provide qualitative evidence that complements the quantitative improvements reported earlier. In Figure 5, the proposed super-resolution model produces sharper and more coherent spatial structures in both B6 and B12, with clearer delineation of river boundaries and more distinct representation of bright regions. By contrast, bicubic interpolation fails to recover fine details, leading to oversmoothed textures and blurred spatial transitions.

Figure 7. Absolute error maps for band B6 (top) and band B12 (bottom) in the Siberia region. The left column shows the error maps for the super-resolution (SR) model, while the right column shows those for bicubic interpolation.

Figures 6, 7 further substantiate these findings through absolute error maps generated for two representative regions (Vietnam and Siberia). In both cases, the proposed model (left panels) achieves lower and more uniformly distributed errors across the entire scene, with notable improvements along edges, textured surfaces, and heterogeneous land-cover areas. In contrast, bicubic interpolation (right panels) introduces larger, localized errors, particularly around boundaries and high-frequency structures, where its lack of spatial adaptivity is most evident.

Taken together, these visualizations confirm that the proposed framework is more effective at preserving fine spatial details and high-frequency information while maintaining spectral consistency across different bands and geographic contexts. Combined with the ablation study results, this provides strong evidence of the robustness and generalizability of the proposed approach to diverse landscapes and spectral characteristics.

The results in Figures 6, 7 show that the proposed super-resolution (SR) model (left) produces lower and more uniformly distributed errors, with sharper boundaries and finer structural details. In contrast, bicubic interpolation (right) introduces larger errors, particularly along edges and in textured regions. These results highlight the superiority of the SR model in preserving high-frequency information.

5 Conclusion

This study presented an enhanced deep learning framework for super-resolving Sentinel-2 imagery, tailored to the heterogeneous landscapes of Vietnam. Building upon the DSen2 architecture, two targeted modules were introduced: a High-Pass Frequency (HPF) layer to strengthen the reconstruction of fine spatial details, and a Channel Attention (CA) mechanism to enable adaptive spectral weighting across bands.

Extensive experiments on data from 30 regions across Vietnam demonstrated that the proposed model consistently outperforms both bicubic interpolation and the original DSen2 baseline. The improvements, although numerically modest in terms of RMSE, are most pronounced in the red-edge and SWIR bands, which are critical for vegetation monitoring, soil moisture analysis, and urban mapping. These gains translate into meaningful benefits for downstream applications where sub-pixel accuracy can significantly influence classification, segmentation, and biophysical variable retrieval.

The proposed framework highlights the value of explicitly modeling both spatial frequencies and spectral relevance, providing a scalable and computationally efficient solution to enhance the usability of freely available Sentinel-2 imagery in data-constrained contexts. Its demonstrated performance positions it as a promising tool for environmental monitoring, land-use assessment, and precision agriculture in regions with limited access to very-high-resolution satellite products.

Nonetheless, this study acknowledges certain limitations. The robustness of the model under extreme atmospheric conditions, highly heterogeneous terrains, or sparsely vegetated regions has not been fully examined, which may affect its generalizability across diverse ecological contexts. Future work will therefore focus on extending the framework to multi-temporal and multi-sensor data, while rigorously testing its performance under challenging environmental conditions. In addition, operational deployments across Southeast Asia will be pursued to further validate its practical utility and scalability in real-world monitoring systems.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1Hbi7a7P01akg2wyNWy6s2svEf5pO58zA?usp=drive_link.

Author contributions

KN-V: Methodology, Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft. BB-Q: Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review and editing. NK: Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Formal Analysis, Methodology.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work is sponsored by VinUniversity under Grant No. VUNI.CEI.FS_0004.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Center for Environmental Intelligence (CEI) at VinUniversity for their invaluable support and resources. This work greatly benefited from the expertise and facilities provided by CEI, which were instrumental in conducting our research. We appreciate their dedication to advancing environmental intelligence and fostering innovative research collaborations.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bordone Molini, A., Valsesia, D., Fracastoro, G., and Magli, E. (2020). Deep- SUM++: Non-local deep neural network for super-resolution of Unreg-istered multitemporal images. 609, 612. doi:10.1109/igarss39084.2020.9324418

Deudon, M., Kalaitzis, A., Goytom, I., Arefin, M. R., Lin, Z., Sankaran, K., et al. (2020). Highres-net: Re- cursive fusion for multi-frame super-resolution of satellite imagery.

Fu, J., Liu, J., Tian, H., Li, Y., Bao, Y., Fang, Z., et al. (2019). “Dual attention network for scene segmentation,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 3141–3149. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2019.00326

Hu, J., Shen, L., and Sun, G. (2018a). “Squeeze-and-excitation networks,” in 2018 IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 7132–7141.

Hu, J., Shen, L., Albanie, S., Sun, G., and Vedaldi, A. (2018b). “Gather-excite: exploiting feature context in convolutional neural networks,” in Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS’18). Red Hook, NY, United States: Curran Associates Inc. 9423–9433.

Huang, W., Xiao, L., Wei, Z., Liu, H., and Tang, S. (2015). A new pan-sharpening method with deep neural networks. IEEE Geoscience Remote Sens. Lett. 12 (5), 1037–1041. doi:10.1109/lgrs.2014.2376034

Kawulok, M., Tarasiewicz, T., Nalepa, J., Tyrna, D., and Kostrzewa, D. (2021). “Deep learning for multiple-image super-resolution of sentinel-2 data,” in 2021 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium IGARSS, 3885–3888.

Lanaras, C., Bioucas-Dias, J., Galliani, S., Baltsavias, E., and Schindler, K. (2018). Super-resolution of sentinel-2 images: learning a globally applicable deep neural network. ISPRS J. Photogrammetry Remote Sens. 146, 305–319. doi:10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2018.09.018

Liebel, L., and Korner, M. (2016). Single-Image Super resolution for multispectral remote sensing data using convolutional neural networks. ISPRS - Int. Archives Photogrammetry, Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 41B3, 883–890. doi:10.5194/isprsarchives-xli-b3-883-2016

Lim, B., Son, S., Kim, H., Nah, S., and Mu Lee, K. (2017). “Enhanced deep residual networks for single image super-resolution,” in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops, 136–144.

Rifat Arefin, M., Michalski, V., St-Charles, P.-L., Kalaitzis, A., Kim, S., Kahou, S. E., et al. (2020). “Multi-image super-resolution for remote sensing using deep recurrent networks,” in 2020 IEEE/CVF conference on Com-puter vision and pattern recognition workshops (CVPRW), 816–825.

Salgueiro Romero, L., Marcello, J., and Vilaplana, V. (2020). Super-resolution of sentinel-2 imagery using generative adversarial networks. Remote Sens. 12 (15), 2424. doi:10.3390/rs12152424

Salvetti, F., Mazzia, V., Khaliq, A., and Chiaberge, M. (2020). Multi-image super resolution of remotely sensed images using residual attention deep neural networks. Remote Sens. 12, 2207. doi:10.3390/rs12142207

Sara, D., Mandava, A. K., Kumar, A., Duela, S., and Jude, A. (2021). Hyperspectral and multispectral image fusion techniques for high resolution applications: a review. Earth Sci. Inf. 14, 1685–1705. doi:10.1007/s12145-021-00621-6

Tarasiewicz, T., Nalepa, J., Farrugia, R. A., Valentino, G., Chen, M., Briffa, J. A., et al. (2023). Multitemporal and multispectral data fusion for super-resolution of sentinel-2 images. IEEE Trans. Geoscience Remote Sens. 61, 1–19. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2023.3311622

Valsesia, D., and Magli, E. (2022). Permutation invariance and uncertainty in multitemporal image super-resolution. IEEE Trans. Geoscience Remote Sens. 60, 1–12. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2021.3130673

Wagner, L., Liebel, L., and Korner, M. (2019). “Deep residual learning for single-image super-resolution of multi-spectral satellite imagery,” ISISPRS annals of the photogrammetry, remote sensing and spatial information Science-sPRS annals of the photogrammetry. Remote Sens. Spatial Informa- Tion Sci. IV-2/W7, 189–196. doi:10.5194/isprs-annals-iv-2-w7-189-2019

Xu, K., Ba, J., Kiros, R., Cho, K., Courville, A., Salakhudinov, R., et al. (2015). “Show, attend and tell: neural image caption generation with visual attention,” in Proceedings of the 32nd international conference on machine learning. 37 of proceedings of machine learning research. Editors F. Bach, and D. Blei (Lille, France: PMLR), 2048–2057.

Yang, J., Fu, X., Hu, Y., Huang, Y., Ding, X., and Paisley, J. (2017). “Pannet: a deep network architecture for pan-sharpening,” in 2017 IEEE international conference on computer vision (ICCV), 1753–1761.

Yang, J., Xiao, L., Zhao, Y.-Q., and Chan, J. C.-W. (2022). Variational regularization network with attentive deep prior for hyperspectral–multispectral im-age fusion. IEEE Trans. Geoscience Remote Sens. 60, 1–17. doi:10.1109/tgrs.2021.3080697

Keywords: super-resolution, Sentinel-2, channel attention, high-frequency features, multispectral imagery, deep learning, environmental monitoring

Citation: Nguyen-Vi K, Bui-Quoc B and Kamel N (2025) Deep learning-based Sentinel-2 super-resolution via channel attention and high-frequency feature enhancement. Front. Remote Sens. 6:1644460. doi: 10.3389/frsen.2025.1644460

Received: 13 June 2025; Accepted: 17 November 2025;

Published: 01 December 2025.

Edited by:

Sartajvir Singh, Chandigarh University, IndiaReviewed by:

Obed Fynn, University of Energy and Natural Resources, GhanaLiu Yi, State Grid Electric Power Engineering Research Institute Co., Ltd., China

Copyright © 2025 Nguyen-Vi, Bui-Quoc and Kamel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nidal Kamel, bmlkYWwua0B2aW51bmkuZWR1LnZu

Khang Nguyen-Vi

Khang Nguyen-Vi Bao Bui-Quoc

Bao Bui-Quoc Nidal Kamel

Nidal Kamel