- 1School of Health and Social Care, Edinburgh Napier University, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

- 2College of Leadership and Public Service, Lipscomb University, Nashville, United States

The wellbeing of astronauts on long-duration space missions is critical to current and future mission success. It is equally important that those who support astronauts, pre-mission, during the mission, and post-mission, are thriving as well. Therefore, this interpretative phenomenological analysis study examines how a selection of NASA leaders perceive a phenomenon, awe, along with related resilience practices, as supporting their wellbeing in both their professional work and personal lives. The results reveal that awe-narrative interviews can support them professionally while also enhancing their overall wellbeing. Awe narratives have the ability to serve as a gateway to other resilience practices, including cognitive reappraisal, finding meaning and purpose in life, gratitude, hope and optimism, and social connectedness. These results suggest the awe narrative-based interventions can offer both an evidence-based and practical way to benefit NASA personnel, as well as other professionals working in high-pressure and stressful environments.

Introduction

The mental health of astronauts has been examined in the literature and presented as a constant concern for space missions (Arone et al., 2021; Kanas, 1998; Landon et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2016). However, there has been minimal empirical research related to the various NASA healthcare and other professionals in leadership roles who are responsible for astronauts pre-mission, during missions, and in post-missions recovery (Thompson, 2023a). This is particularly concerning, as research has shown that suicide, mental health conditions, and burnout (Dawar et al., 2021; Lanocha, 2021; NIOSH, 2024; Petrie et al., 2019) are significant issues among mental health professionals and researchers (Hall, 2023; Hazell et al., 2021; Nicholls et al., 2022). This study builds on a previous study (Thompson, 2023a), which found that the experiences of awe, when viewed as a gateway to other resilience practices, can support the resilience and overall wellbeing of NASA leaders and medical professionals. The current narrative psychology study expands on this previous study that involved a single participant, by utilizing interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) to examine the role that awe narratives can have with additional NASA leadership participants (n = 7). Narrative medicine and narrative therapy practices also informed the study, including the development of a semi-structured interview intervention and the subsequent data analysis, to ensure the humanity and dignity of each participant remained a focus throughout the process. This is consistent with IPA, as it explores how individuals understand and makes sense of a phenomenon (Smith and Osborn, 2004; Smith and Nizza, 2022). For this study, awe is the initial thread, or phenomenon, being examined while it also explores how this awe narrative intervention can also illuminate other resilience practices weaving an interconnected tapestry of overall wellbeing professionally and personally that includes cognitive reappraisal, finding meaning and purpose in life, gratitude, hope and optimism, and social connectedness.

This paper first examines the literature on awe and resilience related to this study, and then details the narrative psychology methodological framework that supported the examination of how awe narratives and related resilience practices can support these NASA leaders. Next, and consistent with IPA research (Smith and Nizza, 2022), the findings and discussion are presented together identifying the themes that emerged. Finally, the paper concludes with detailing the limitations and future opportunities that can expand on these findings.

Awe

Awe has been described as a complex, primarily positive emotion experienced in the presence of something or someone extraordinary that challenges an individual’s thinking (Stellar, 2021; Thompson and Jensen, 2023; Thompson, 2025a). Common contexts in which awe is experienced include nature and space, the arts, accomplishments (one’s own and others’), spirituality, and in the presence of others (Bai et al., 2017; Chen and Mongrain, 2020; Chirico et al., 2017; Cuzzolino, 2021; Danvers and Shiota, 2017; Shiota et al., 2007; Sturm et al., 2020; Yaden et al., 2018). While these categories are broad, recent research has revealed the complexity of awe by identifying nine categories, along with 20 sub-categories (Thompson, 2023b).

In their seminal work on awe, Keltner and Haidt (2003) explained there are two elements to awe experiences, a sense of vastness and a need for accommodation, or a need for a new mental schema due to the vastness. As awe continues to be explored through diverse empirical methodologies, our understanding of awe continues to evolve. In context of the current study, this includes the notion that awe experiences are not limited to solely extraordinary moments in life, but can also be experienced in everyday, ordinary moments (Keltner, 2023; Graziosi and Yaden, 2019; Schneider, 2009; Shiota, 2021; Thompson, 2022a; Thompson, 2023b).

Developing and sharing awe narratives has been shown to serve as a gateway to many resilience practices and to initiate an upward spiral of wellbeing (Lutz et al., 2015; Monroy and Keltner, 2023; Tabibnia, 2020; Stellar et al., 2018; Sturm, et al., 2020). Recent work by Shoshani and Hen (2025) explored the use of eliciting awe through virtual reality to support the resilience of children and adolescents affected by war; Kaur Dhillon (2025) proposed that integrating awe experiences such as in nature and the arts can build resilience; Chang et al. (2024), examined the relationship between psychological resilience and awe; and Chen et al. (2025), demonstrated that awe experiences can increase resilience and wellbeing. Additionally, other recent studies established the relationship between awe and other specific contributors to resilience including awe boosting optimism (Pan and Jiang, 2024) and self-compassion (Yuan et al., 2025), and awe being supportive of having meaning in life (Yuan et al., 2024).

The author’s previous qualitative work examined the relationship between both awe narratives serving as a resilience practice as well as awe narratives being a potential gateway to other resilience practices. This includes with conflict resolution professionals (Thompson et al., 2022); in policing generally (Thompson, 2023c), with hostage negotiators (Thompson and Jensen, 2023), investigators (Thompson, 2023d), and with leadership (Thompson, 2022c; Thompson, 2024); medicine and healthcare (Thompson, 2023a); and other diverse audiences (Thompson, 2022a; Thompson, 2022b; Thompson, 2023b). Related to the current study, many of the previously mentioned publications by the author specifically explored how awe narratives can be utilized to enhance both an individual’s professional skills and support their personal wellbeing.

Resilience

Resilience is defined in various ways but can broadly be understood in three parts: planning for, enduring, and recovering from adverse and stressful life moments; seeking support services when facing challenges; and cultivating positive life experiences (Thompson et al., 2022; Thompson, 2023b; Thompson, 2025a). A diverse set of resilience practices is needed throughout life to not just cope but to thrive (Bonanno, 2005; Bonanno, 2021; Thompson, 2020). Related to the previously provided definition of resilience and its three elements, this paper supports the notion that resilience is not a fixed personality trait and instead, it can be continually cultivated throughout and individual’s life (Cicchetti, 2010; Masten, 2001; Southwick et al., 2014; Yates et al., 2015). Within the context of this study, prominent resilience researchers, Rachel Yehuda and Anne S. Masten, both have emphasized the importance of proactively practicing resilience (Southwick et al., 2014).

In this study, key resilience practices include engaging in cognitive reappraisal (Riepenhausen et al., 2022; Southwick and Charney, 2018), finding meaning and purpose in life (Aten, 2021; Ostafin and Proulx, 2020), practicing gratitude (Emmons, 2010; Wilson, 2016), fostering hope and optimism (Reivich and Shatté, 2003; Vos et al., 2021), and cultivating social connections (Britt et al., 2021; Suttie, 2017). The American Psychological Association (APA) publication on building resilience, through the support of a vast array of expert contributors, detail similar practices, or as they refer to them as strategies, to support the on-going development of resilience (APA, 2020).

Methodological framework

Narrative psychology provided the framework for this study to examine the role of awe among NASA leaders. Narrative psychology is a broad qualitative methodological approach involving scientific analysis of how individuals reflect on, share, and are shaped by stories (Polkinghorne, 1995; Wong and Breheny, 2018). A person’s reality is created through the story they craft, which also helps them make sense of life events (McAdams, 2001; Morioka and Nomura, 2021; Thompson, 2025a; Thompson, 2025b; Thompson and Launer, 2025). These life stories are not fixed; instead, they are ever-evolving and adaptable, shaping how the past is recalled, how one lives in the present moment, and how the future is envisioned (Dingfelder, 2011; Hill, 2022; Hunt, 2023; Rutledge, 2016; Thompson, 2025a). The notion that “stories are science” is supported by the researcher’s role in examining the sensemaking processes of individuals and groups while also identifying emerging themes (Hunt, 2023; Thompson, 2025a).

Within the narrative psychology framework, three specific approaches were utilized in this study: interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA), narrative-based medicine, and narrative therapy. IPA aims to understand an individual’s experience of a phenomenon–awe, in this study–and then allows the researcher to interpret the data and establish themes across multiple individuals’ accounts (Creswell, 2007; Smith et al., 2009; van Manen, 1990). IPA prioritizes the depth and richness of data; therefore, large samples sizes are not necessary to establish rigor (Smith and Osborn, 2004; Smith and Nizza, 2022). Importantly, the results and findings in IPA studies are indicative of the specific group being studied and are not universal claims. IPA reinforces the notion that stories are science, especially through the role of the researcher. Known as the hermeneutic circle (Frechette et al., 2020), the researcher’s own experience with the phenomenon supports their capacity to analyze the data, resulting in meaningful themes (Smith et al., 2009). Importantly, IPA does not reduce individual voices to flattened categories; instead, it honors the uniqueness and dignity of each participant. This study reflects that by presenting individual accounts and in-depth comments that highlight the humanity behind each theme. While IPA served as the primary methodological approach, narrative analysis offered supplemental guidance by focusing on how individuals make meaning of their lives and experiences within social contexts (Josselson and Hammack, 2021).

Narrative medicine, also referred to as narrative-based medicine (NBM), is a humane approach to medical practice in which the clinician absorbs, interprets, and acts upon the stories of others (Charon, 2001; DasGupta, 2008; Launer, 2022). Though originally developed for physicians, NBM has since been adapted for use by other medical and healthcare professionals and in a variety of professional contexts (Launer, 2018; Thompson and Launer, 2025). In this study, and much like IPA, NBM ensures that the humanity and dignity of the individual remain central (Centor, 2007; Launer, 2016; Loy and Kowalsky, 2024; Thompson, 2025a; Zaharias, 2018). Just as a good physician treats the disease, while a great one treats the person who has the disease (Lanoche, 2021), this study aimed to illuminate the individual humanity of NASA healthcare and other leaders, whose personal stories led to the emergence of shared themes. As Dr. Rita Charon observes, “there is a life in its unity that cannot be seen in its parts, yet one must see the parts in order to see the whole” (Charon, 2016, p. 180). Moreover, NBM helped ensure that the motivation behind the interview questions, and the subsequent writing of this paper, was grounded in curiosity (Launer, 2018), rather than a predetermined set of expected answers or themes. This complements the inductive approach to IPA (and narrative inquiry), wherein data are collected with openness, rather than restricted to preconceived frameworks designed to make findings “fit” (Smith and Osborn, 2003; Smith and Nizza, 2022). As Dr. John Launer elaborates, rather than asking “what is really going on?”, the curious researcher asks “How are people giving an account of their experiences?” (Launer, 2018, p. 3). He further explains, again, in line with IPA, that the emerging story is continually being woven, much like a tapestry.

Narrative therapy practices supported, guided, and informed each stage of the study, including the formulation and delivery of the interview questions. Although the study was not designed as a therapeutic or clinical intervention, the act of sharing one’s story with an interested and empathetic listener can have a positive, therapeutic effect (Atkinson, 2002; Murray and Sergeant, 2011). Typically, individuals engage in narrative therapy to address a problem or negative life experiences (Hill, 2022; Morgan, 2000; White and Epston, 1990). However, in this study, narrative therapy techniques and practices were applied to elicit stories about positive moments in NASA leaders’ professional and personal lives. Engaging in this type of reflective practice can have numerous benefits, including countering and reducing work-place burnout by promoting hope and optimism (Varma, 2025).

These techniques included fostering a sense of agency, re-authoring or re-storying, both core skills used in narrative therapy (Carr, 2000; Hill, 2022; White, 1995), and creating space for stories to “breathe” (Frank, 2010; Launer, 2024; Thompson, 2025b), allowing for thick descriptions (Morgan, 2000) of awe-related moments to emerge. From this perspective, the researcher also took the role of “co-author” (Gibson and Heyman, 2014; Thompson, 2025a). Adapting this term from narrative therapy, the research as a co-author collaborates with the participants by guiding them in exploring how awe has influenced their lives. This was initially done by strategically designing the semi-structured questions that also explored related resilience practices. This metaphorical role as co-author supported the NASA leaders to re-author, or re-story, their experiences to tell their stories in a way that highlights their strengths, abilities, and values (Hill, 2022).

In this context, a sense of agency refers to the participants’ recognition of how their own actions contributed to a broader sense of hope and purpose (Adler, 2012; Gibson and Heyman, 2014; Hill, 2022). Re-storying and re-authoring allowed participants reinterpret seemingly ordinary moments of their lives as extraordinary and awe-inspiring (Graziosi and Yaden, 2019; Schneider, 2009; Thompson, 2023b).

The researcher’s role as a co-author further enabled participants to move beyond surface-level responses to the guiding questions. Instead of offering quick or apathetic answers, they were encouraged to pause, reflect, and search for personal meaning in their responses. This often resulted in deeper, richer narratives in which each answer built upon the next, interconnecting and forming a metaphorical tapestry that illustrated awe’s role as a gateway to other resilience practices. This approach is consistent with NBM’s process of narrative crafting (Gray, 2025; Launer, 2018; Lazarus, 2024; Narrative-Based Medicine Lab, n.d.; Nash et al., 2023; Pollock, 2001; Thompson, 2025b).

This study focused on awe stories due to the previous research that established the relationship between awe-based narratives and resilience through interview-based, non-therapeutic interventions (Thompson, 2023a; 2023b; Thompson and Jensen, 2023; Thompson, 2024). More broadly, the development of life stories has been associated with key resilience practices, including cognitive reappraisal, finding meaning and purpose in life, gratitude, hope and optimism, and social connectedness (De Vivo, 2024; Hou, 2023; McAdams and McLean, 2013; Regan et al., 2023; Rutledge, 2016).

Methods

The narrative literature demonstrates that life stories do not merely explain one’s life; they actively shape it, crafting how the past is recalled, how the present is experienced, and how the future is envisioned. The study builds on a previous investigation of NASA leadership (Thompson, 2023a) by further exploring how awe-specific narratives may serve as gateways to resilience practices and contribute to an upward spiral of wellbeing across professional and personal domains.

The current study followed the same methodological process and maintained the same institutional review board approval as the earlier study, which involved a single NASA healthcare leader (Thompson, 2023a), as well as another study that used awe narratives with police hostage negotiators (Thompson and Jensen, 2023).

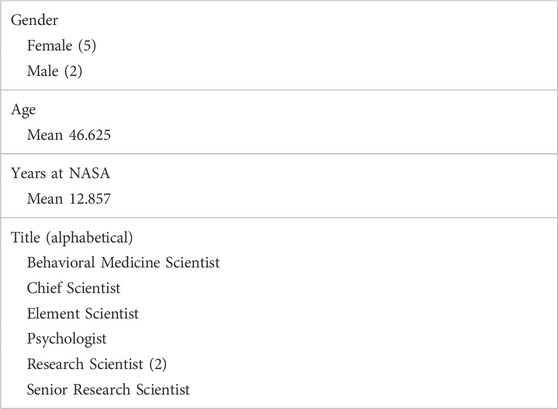

This study excluded the previously published data on the single NASA leader and includes the data from seven additional NASA leaders. Table 1 presents the demographic information of these participants.

Individual, semi-structured interviews were conducted and recorded via Zoom, then transcribed. The digital data files were password-protected and accessible only to the researcher-author. Each interview consisted of approximately 19 questions and lasted about 1 hour. A digital follow-up survey was also administered to gain further insight from the participants, including reflections on their experience of participating in the study. Following the same process as in previous studies (Thompson, 2023a; Thompson and Jensen, 2023), and consistent with both IPA (Smith et al., 2009; Smith and Nizza, 2022) and narrative analysis (Butina, 2015; Josselson and Hammack, 2021), the researcher took notes during the interviews, reviewed the transcripts multiple times, drawing on prior experience researching the phenomenon of awe and analyzing narratives, identified emergent themes.

Results and discussion

Consistent with IPA, this study aimed to explore a phenomenon, in this case, awe (Smith and Nizza, 2022). More precisely, rather than formulating a traditional research question (Smith et al., 2009), the study sought to examine how awe-based narratives might serve as gateways to other resilience practices, contribute to an upward spiral of wellbeing, and support the work of those involved. Given the unique leadership roles of the NASA participants, the potential impact of the findings extends beyond the individuals themselves to those they influence professionally. Importantly, the study’s design was intentional in seeking to provide an intervention that is not only evidence-based but also practical.

Consistent with IPA research, the results and discussion are presented together to create a coherent narrative (Bonner and Friedman, 2011; Cuzzolino, 2021; Smith and Osborn, 2003; Smith et al., 2009; Thompson et al., 2022; Thompson and Jensen, 2023). This approach illustrates how awe is woven throughout each theme and how the themes themselves are interconnected. Moreover, awe is not only a gateway to other resilience practices, but, together with these practices, forms a tapestry, where each element is interwoven into a new “whole”, as described earlier by Dr. Charon. While theme development is a central feature of narrative methodologies such as IPA, the humanity and dignity of each participant remain at the forefront in this section, preventing the findings from being reduced to a broad “sum of the parts.” Each theme is therefore illustrated and supported by individual participant comments and narratives.

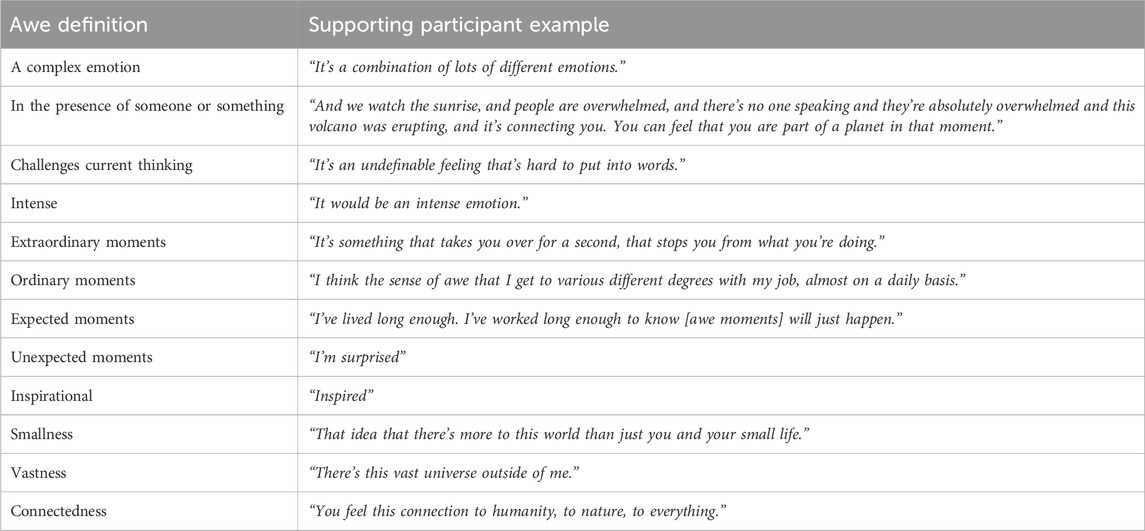

The results and discussion begin with how participants described the phenomenon of awe and the impact the awe narrative interviews had. Table 2 presents examples of how their definitions and descriptions of awe support and expanded upon the definition used in this study: awe is a complex emotion experienced in the presence of someone or something extraordinary that challenges our thinking. Awe experiences are often intense and may arise during both ordinary and extraordinary moments, whether anticipated or surprising. Awe can also be inspirational and evoke a sense of smallness, vastness, and connectedness, to others, to nature, and to the universe.

While Table 2 illustrates the “parts” of awe that contribute to the overall definition, the “whole”—as Dr. Charon described, the richness of IPA is further highlighted by the following thick description of awe shared by one participant:

“Awe, to me, is a combination of a lot of different emotions. People call it a single emotion, but to me, it's a mixture. It's a sense of deep appreciation, but also wonderment of making you think and making you have a sense of perspective, both for yourself, but also those around you.

That it is being in the moment in a very ultimate way, but also very forward thinking, in a sense, of just really, really appreciating what’s in front of you at that moment, but also what’s in front of you going forward, what we can expect to be there. Typically, I would define it as a positive emotion, but I would also define it as an activating emotion.

It is something that makes your heart flutter a little bit, gets your autonomic system going a little bit, but in a good way, not in a fearful or upset kind of way. It is more in an alertness, but alertness to the beauty of something or the positive experience of something.”

This narrative, shared by a NASA leader, underscores the complexity of awe and highlights its immediate and enduring positive effects, shaping thoughts, emotions, and behavior both in the moment and in the future.

To assess the efficacy of the awe narrative intervention, participants were asked, both during the interview and in the post-interview survey, whether (1) they had previously considered awe’s potential role in their professional work and (2) more broadly, whether they perceived value in engaging this kind of reflection. Participant responses revealed both surprise at awe’s relevance and a deep respect for its influence, especially in terms of initiating an upward spiral of positive wellbeing:

“I had not previously connected the term ‘awe,’ but it makes so much sense. I just felt inspired, like it always feel inspiring. But to me, feeling inspired, as I said when you asked me to define it, is being filled with awe. Yeah. It makes complete sense that awe would be associated with my feelings.

When I go back into the field, I’m always so happy to be there. And sometimes, I go through this period before I have to pack up and go into the field, because I’m packing up not just for me. I’m packing up for everybody. I’m making sure they’re ready. And we’ve got all this stuff that hopefully you never have to crack open in the case of emergency, ready to go.

And then sometimes, I get to this point where I'm like, ‘god damn, I'm so tired. I do not want to go. I do not want to be away from my kids and [my spouse].’ But then I'd go, and then something just remarkable happens, and it can be the smallest thing, but I then realize, ‘Oh yeah. Right. I love this. This is me … Right?’ It's all that. It comes flooding back.”

“Definitely I have [thought about awe’s role], and it's actually a huge piece of what we do as Behavioral Health Scientists here at NASA. For so long, both in the behavioral health field in general, but also particularly at NASA, the focus has been purely on pathology. It's purely been on the negative of what are all the things that can go wrong, and how they go wrong? But the flip side of that is: what are all the things that go well or right, and how do they go right?

And I think that’s still a problem in the field of psychology in general. There’s a movement towards positive psychology and resilience and post traumatic growth and all of those kinds of topics… there’s a movement here now at NASA to start really looking at those factors.”

While there are distinct differences in the two responses, collectively they demonstrate how even a brief reflection prompted by an awe-related question can potentially have a perceived significant impact. These responses reveal awe’s value as a standalone positive contributor, capable of initiating an upward spiral of wellbeing while also serving as a gateway to other resilience attributes.

The next response further support the notion that the awe narrative interview intervention can be both valuable and meaningful for participants, prompting reflection on the past while also serving as motivation for the future:

“I do not think I've ever thought about it specifically in that way, so, yeah, I really appreciate that. I think now, hopefully, I'll see it with new eyes again, especially the juxtaposition here on site between the ordinary things on the planet, like deer and squirrels, sitting right next to these giant rockets. And I do get to drive by the mission control building pretty regularly.

So, I think there’s a psychological term, hedonic adaptation, when you get used to something, you do not appreciate it as much, unless you’re kind of consciously doing that gratitude exercise, really staying in touch with that. So yeah, hopefully this will encourage me to start doing more of that and really appreciating it.

I just really appreciate being more thoughtful about this. I think it is brought it more to the forefront of my mind, and I think I’m going to do a lot more thinking about it. So yeah, I appreciate that a lot.”

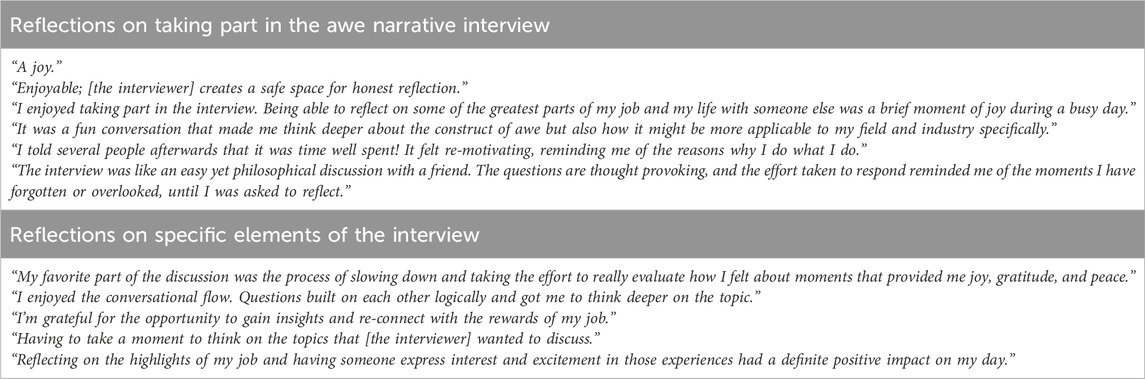

Table 3 provides an overview of the participant feedback collected via the post-interview survey, where participants shared reflections on what it was like to take part in the interview. They were also asked whether anything specific stood out to them or was particularly meaningful about participating in the interview and the overall awe-focused study.

Collectively, the participants expressed finding value in the awe narrative interviews. Once again, the gateway and tapestry metaphors between awe and other resilience practices were revealed through these reflections, specifically, cognitive reappraisal, gratitude, hope and optimism, meaning and purpose in their work, and social connectedness. Each of these themes emerged repeatedly throughout the interviews and are further explored in the sections that follow.

Themes

The capacity of awe narratives to serve as gateways to other resilience practices, as previously noted, does not occur in isolation. These practices and attributes are often interconnected, reinforcing the tapestry metaphor. From this perspective, the following five resilience skills emerged as primary themes in the data: cognitive reappraisal, gratitude, hope and optimism, meaning and purpose in life, and social connectedness. These themes contribute to upward spirals of wellbeing and, importantly, have been shown in previous research to counter negative downward spirals such as depression, anxiety, burnout and cynicism, and to serve as protective factors against suicide (Hooker et al., 2020; O’Higgins et al., 2022; Southwick et al., 2021; Thompson et al., 2022). The thick descriptions of individual participant narratives included in this section illustrate these themes in resilience, often blending multiple resilience dimensions together, consistent with existing research on the transformative potential of awe narratives (Bonner and Friedman, 2011; Hlava et al., 2023; Thompson, 2022a; 2022b; 2023a; 2023b; 2024; Yaden et al., 2018).

Although it is beyond the scope of this study, prior research suggests that the benefits of awe narrative practices are not limited to reflecting on or sharing one’s own experiences; similar positive effects may also occur when individuals are exposed to the awe stories of others (Thompson, 2025a).

Cognitive reappraisal

Cognitive reappraisal typically involves examining a negative or neutral moment and discerning something positive or meaningful within it (Hanson and Hanson, 2018; Southwick and Charney, 2018; Thompson, 2025a). In this study, cognitive reappraisal also occurred when participants reflected on seemingly ordinary moments that, once prompted, revealed deeper significance:

“I feel pretty cool. I will say sometimes your job is your job and some days you’re just kind of like, oh gosh, I got to do this again. Or, oh, I have to write this report, whatever. Then I step back and I [realize], I'm writing about people going to Mars. I need to remember that in the greater context, like yes, I have to do this reference list, which takes some time, but it's all to serve this really cool thing. It helps to remind yourself that it's pretty cool to do what we do. Doing things like this, doing interviews, I do a lot of guest lectures or invited talks to different groups. That will kind of help remind me seeing others' perspective. I'm like, oh, this stuff is kind of cool. But it's like the same slides I've looked at a hundred times, but to them, they're like, oh wow. They have all these questions about it. I'm like, oh, okay. People care.”

The participant further explained this reappraisal approach and how participating in the study enhanced their ability to remain motivated going forward:

“I have recognized myself sort of experiencing it. When those occasions happen where you find some profound awe kind of occurring, I am mindful enough to recognize it, but I do not sit there and think about deliberately thinking about it.

Of course, talking to you today, it’ll make me more aware of it in the future. It is kind of like a queuing mechanism, right? It is like you start feeling that feeling, and then you’re like, ‘Oh, this is what we talked about.’ And so, you recognize it and perhaps hopefully you understand it on a more profound level.”

Cognitive reappraisal of ordinary moments, both in professional and personal life, can reveal how experiences initially perceived as mundane may, in fact, be imbued with awe. This process not only reinforces awe as a resilience mechanism but also overlaps with other themes such as gratitude.

Gratitude

A sense of gratitude and appreciation can emerge both as an outcome of cognitive reappraisal and as a resilience practice in its own right. Gratitude has frequently been linked to enhanced resilience, and is often a key feature within awe narratives (Emmons, 2010; Emmons and Mishra, 2011; Thompson and Drew, 2020; Thompson, 2023a). Many participants reflected throughout their interviews that they felt grateful, not only for their work but also for their co-workers and their personal lives. The following NASA leader shared how gratitude can be experienced in diverse ways, both professionally and outside of work:

“I think, on a daily basis, I probably really lose touch with [what I do for living]. It's fun to talk to people who really think that this so cool. To me, this is a typical Wednesday.

I'm so grateful to be back at the office, because just driving onsite, you go through the gates at Johnson Space Center … you come on and you see the giant rockets. We've got the Saturn V greeting us right at the front gate, so that definitely sets the tone for the day.

And then there’s a SpaceX rocket that has flown and it is sitting out there. And then on the other side, there’s the Saturn V and a bunch of other rockets kind of strewn about.

And the Longhorn Project, we have lots of environmental, collaborative programs around here. So, there’s Longhorn cattle out there. And then when you drive offsite, there’s a whole lot of deer. We’ve got a lot of wildlife that kind of took over during the pandemic. The deer were walking down the sidewalks and looking in the windows.

I love seeing that again.”

Gratitude practices, especially writing down things one is grateful for, are widely recognized practices for enhancing resilience (Thompson and Drew, 2020). One NASA leader explained the impact of this daily habit, both in their role as a mental health professional and for personal reflection:

“As a daily practice, being a true psychologist, this is something that I used to have my patients do, I just keep a little moleskin notebook kind of thing–one of those little notebooks. And every day, at the end of the day, I just write down one thing that I'm grateful for that day.

No matter how big or small, just one thing. It was like the sun was shining at my lunch break and that was a great moment. And I just call it the gratitude journal, but it is makes me reflect on the day and say, okay, it could have been the worst day in the world, but what was the one little thing that I can pick out that was like, cool.”

This narrative illustrates how, like awe, gratitude does not have to stem from grand or extraordinary experiences. It can also arise from small, everyday moments, when approached with a particular mindset and perspective.

Hope and optimism

Practicing gratitude often entails reflecting on present and past experiences, while hope and optimism can be viewed as a form of future gratitude—the anticipation and belief that positive experiences are possible and will occur (Thompson, 2022a). Hope and optimism involve not only cultivating this mindset but also taking actions to bring about desired outcomes. Optimism can be learned (Meevissen et al., 2011), it is associated with workplace satisfaction (Youssef and Luthans, 2007), and it contributes to a generally positive outlook on life (Usán Supervía et al., 2020).

Cultivating hope and optimism is both an individual and collective endeavor. The following NASA leader illustrate how their work contributes to future success, not only their own but also that of others:

“It's more than just a paycheck. A paycheck's got to be there, do not get me wrong… I happen to be in a place where we put people in space… and to do things that people love to do.

I’m trying to train our next-generation so I can watch them be successful and share the joy of seeing what they get to do for us.”

Another participant reflection from another NASA leader, like many of the shared narratives, incorporates several resilience practices, including how having hope and optimism in their current work contributes to significant milestone moments in the future that extend beyond their individual contribution:

“I think awe helps you appreciate where we're going to, that it's not going to be this mission that is only defined on a word document somewhere forever. Someday, somebody's going to get on top of this rocket and they're going to the moon or they're going to Mars, and we've got to get them ready for that … It moves it from the theoretical to the real and helps to remind you what you're working towards.”

As demonstrated in these stories shared by NASA leaders, hope and optimism can be connected to present-moment motivation, where they can have the ability to effectively counter burnout and cynicism in a positive way. Furthermore, hope and optimism are closely interwoven with meaning and purpose in life, both in the present and looking forward, and this relationship is explored further in the next section.

Meaning and purpose in life

Having meaning and purpose in life can be cultivated through exploring awe narratives (Thompson, 2025). Meaning and purpose in life (henceforth referred to as MPiL as first mentioned by Thompson, et al., 2022) refers to an individual’s sense that their life has significance, that they are contributing to something positive for themselves and others, that they are pursuing worthy goals, and that there is a sense of order or coherence in their life (Thompson et al., 2022). The following participant stories illustrate these elements:

“I work with ISS astronauts… just thinking about being a NASA [mental health professional], it's very meaningful. I feel like it's a rewarding career. I've stayed [many] years, I always just feel most rewarded when I feel like I can help people achieve their goals.”

Possessing MPiL has been shown to help counter professional burnout and cynicism (Hooker, et al., 2020; Lanocha, 2021; O’Higgins et al., 2022; Southwick et al., 2021), and the following stories from two different participants further support this:

“You have to celebrate the small wins and the big moments, or else the little things will nickel and dime you–death by a thousand paper cuts. So, I try to recognize that we have an immense amount of opportunity to see some amazing things and to experience that and to point people in the right direction. And so, I think it helps me stay motivated, and it helps me motivate the others that I help mentor and lead in the group.”

“For me [awe] seems to be more the bigger things, because it forces me to step out of the mundane tasks and reevaluate, or gain a new perspective.”

Importantly, MPiL extends beyond professional roles. NASA leaders repeatedly emphasized the importance of work-life balance and described how they contribute to a NASA culture that promotes this balance:

“I also work with a lot of other psychologists and behavioral health people. When any member of our team is out of office, we truly treat them as out of office. We never text them. ‘After hours’ is a bad word around here. That kind of stuff. Just to try and support each other in those boundaries and really make that a cultural thing for us–that it's not just one person fighting against the current. We take care of each other. It’s been really nice.”

“Our team has been really good about respecting that 40 hours is 40 hours.”

While participants consistently explained how their NASA work supports their MPiL, they also recognized that their identity and purpose extended beyond the significant work they do:

“I like to do things where we just are with the family. That is so enjoyable … And I'm very lucky because I have a partner who's committed to this too, to be really present for each other and for the kids.”

Many of the participants expressed that their MPiL is directly connected to the teams they are part of, and that their role as leaders includes cultivating MPiL collectively. The following story illustrates this, while the next section further explores social connectedness, both professionally and personally:

“From work, I love that moment when a team comes together, like that absolute moment where you realize that people are not speaking past each other. They're building on each other. They trust each other. They are laughing with each other, but not in a way which is distracting. It's productive. And they are driving forward and they're doing it in a way which you know will build towards something and that there's actions that will build to more actions and that they're going to close this, whatever it is they're working on, out in such a creative, innovative way.

That moment, when that happens, is like pure magic to me. I cannot even.…It is unreal. It is the best. And I’m like, ‘This is possible.’”

Creating a positive culture and enjoyable work environment supports both individual and collective MPiL, and it is something this leader specifically emphasized:

“We are really good about creating the environment that we preach. We really take care of all our interpersonal relationships, our individual wellbeing. We check in with people. We let people have vacations. There's not that toxic work environment. Our lab is actually super healthy that way. And I think part of it is the selection, like we have made sure we choose people that also honor that stuff. That's a huge part of it.”

Social connectedness

Social connectedness, when viewed from a resilience wellbeing lens, can support an individual professionally and personally (CDC Social Connection, 2024; Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010). Previous research has shown that feeling socially connected to others is a frequent theme in awe narratives, and that a similar sense of connection can arise even when individuals are merely exposed to the awe narratives of others (Allen, 2018; Piff et al., 2015; Thompson 2025a). The following narratives from this study further underscore the importance of social connectedness in various forms:

“I think the sense of awe that I get to various different degrees with my job, almost on a daily basis, I run into something that's like, ‘Whoa, that's super cool.’ Or that person is just so incredible, I'm in awe of their ability or their thinking style or something like that. And that kind of awe, to me, is always the perspective of: this is so much bigger than myself or so much bigger than my job, that this is for a purpose, a bigger purpose in life, and it's not just for me, it's for everybody.”

“I think everything is the people. It comes down to the people. And the team care, I think that is so important.”

“Maintaining connectedness to nature and humanity is important and really critical.”

The comments above highlights that social connectedness is not limited to human relationships, it can be experienced through a sense of unity with the natural world. Mentorship, both being mentored and serving as a mentor, was also frequently mentioned as a crucial form of social connectedness among the NASA leaders:

“There's been mentors along the way. There were definitely people who helped, I mean, every step of the way.”

“It's the people that saw me for who I am and who believed in me … ”

“[I was] mentored by one of the astronauts who was leading that [space suit] work and he really showed me the big picture. I think [mentors are] critical. When you're young, especially and probably in any industry really. And you're trying to figure out what it is that you want to do, and where do you fit in?”

“[Having a mentor is] pretty huge, and it does not have to be like super formal mentorship.”

“I care a lot. I'm constantly trying to foster the environment that we preach should exist with the astronaut crews.”

In this next story, a NASA leader described how the value of social connectedness extends into their everyday personal life:

“Family meals, when the kids are behaved and eating their food and we do not have to harass them the whole time … when we're all just like hanging out at the breakfast table or dinner table, I just really enjoy that. They just tell me their silly little stories or this morning they're making fart jokes so that's fun.”

This reflection is a poignant reminder that although these individuals are contributing to high-stakes missions, including those in the future to the Moon and Mars, they, and their families, are very much like everyone else—their children, like many others, find humor in flatulence jokes. Notably, this story also underscores the individual humanity behind each of the thousands of people working to ensure the safety and success of astronauts and their space missions.

The specific impact of awe

Considering this study utilized awe experiences as the phenomenon being examined, the interview included exploring how awe specifically has impacted their professional and personal lives. The following stories exhibit how the awe-prompt questions allowed the participants to reflect on the significance awe had in different moments related to their NASA work:

“I feel like I'm constantly in awe of [the Earth-based analog astronauts] too. And maybe it's more just impressed, but in awe that they're able and willing to do that. They sacrifice months of their lives, and they get thrown in.”

“[Awe] keeps me motivated. I know it's there. I know it will happen.

I just do not know when. And I know I cannot live for it because if you do, then you get lost and you forget to be disciplined and methodical and buttoned down.

But I know now, I’ve lived long enough. I’ve worked long enough to know [awe moments] will just happen. And when they do, I’ll be so lucky to be around for them.”

“I think those moments of awe and the appreciation that they give you for either the work you're doing, the job that you're in, the goals you're working towards, they act as motivators.”

The narrative approach also provided NASA leaders the opportunity to reflect on awe moments in their personal lives, revealing how those experiences continue to influence them:

“I remember watching my [spouse] walk down the aisle at our wedding and having this amazing sense of this feeling like they chose me, like, how did this happen? I've always struggled with feeling worth or value, and knowing that they chose me, was one of those moments that brought me to tears and I cannot ever really forget.”

“You see stuff that you just, you just go, ‘Wow, this is so much bigger. Earth is so much bigger than us.’ And that we're just a tiny little blip in the middle of all this cool stuff and millions of years of geology and planetary formation and all that kind of stuff is just… There was a moment, actually, when I went to one of the national parks and you can actually see the stratified layers of sandstone, and just physically touch it and go like, ‘I'm physically touching millions of years ago.‘”

Additional awe themes

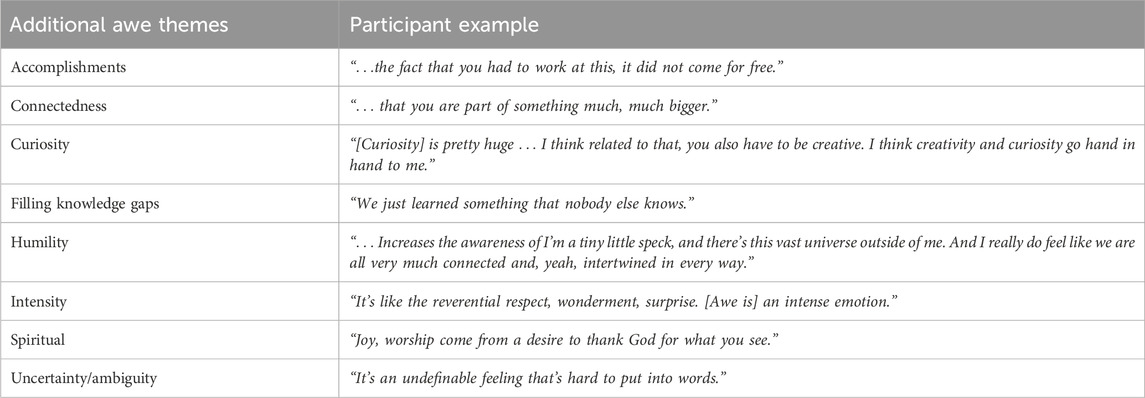

The previous section identified, through the analysis of the data utilizing IPA, the leading themes that emerged. Additional resilience themes were also present and are consistent with the previous awe narrative NASA leadership study (Thompson, 2023a) and the other related studies (see Thompson, 2025). Table 4 identifies these themes, each supported by a participant comment.

Social connectedness and being in the company of others is a well-established category of awe and was once again demonstrated as a theme in this study, consistent with previous research (Sturm et al., 2020). However, recent awe research has also identified being alone as a “new” awe category (Thompson, 2023b). Participants explained how their awe moments occurred when they were by themselves:

“I just love the water. I'd take pictures of the beach and just be there by myself.”

“[On nature eliciting awe] I think it's the vast expanse. And it just, it really, I feel connected to the larger than myself, I guess. That sounds cliché, but. There's also [a place near where they live] and it is literally in the middle of nowhere. And it's just very, I mean, I do not know if most people would find it beautiful, but it's just in this stark, empty, vast space, I find beauty in that as well. There's no people for miles and miles and miles.”

“[Sunrise] is the quietest time and that's what I appreciate about it. Not many people are up moving, it's a very still personal moment with the world. Really, I think that helps energy wise recharge me so that when everything's going to start pulling, I'm ready to go. That is a very special time every day for me, sunrise.”

While these NASA leaders are engaged important work that extends beyond our planet, their humanity is evident throughout their reflections. Although being alone is a considered a newly identified awe category, the following example, aligned with the well-established awe category of nature, further illuminates the participants’ deep emotional connection to the world around them:

“I was walking my dog. When he went to the park, he was running around. And I was listening to the eucalyptus trees bouncing off each other. That was brilliant. It was so brilliant … That's a moment of absolute awe. I'm still surprised at how beautiful that is.”

Finally, this study aimed to provide a safe space for awe reflections, where the research process would allow the story to “breathe” (Frank, 2010), and provide participants to craft their narratives meaningfully. The tapestry of awe is woven by illuminating the humanity of individual NASA leaders, revealing resilience threads that support their own wellbeing. Yet these threads are not limited to them. As previously discussed, much of their work, especially as leaders, is focused on supporting others: the astronauts on current and future missions, the public, their families, and, lastly, themselves. The following participant reflection honors their individual humanity and dignity while also contributing to an upward spiral of wellbeing reaches far beyond themselves, and eventually, beyond this planet.

“It's amazing. Honestly, I never expected it to be my career path, but now that I've found it and fallen into it, it's exactly where I wanted to be. It's exactly where I need to be. It's the perfect fit. It's like I should have been here all along. It's so meaningful and it's so engaging and it keeps me on my toes. I'm constantly learning, it keeps me humble of all the things I do not know, but at the same time, it makes you want to do better. And there's a clear purpose behind the research that we do that we have very clear gaps and goals to get someplace.

There’s an end goal in mind and so, it is very mission oriented in that sense, but it is fulfilling, in a way, because most of the time around here, especially in my department, we have a big poster that’s a common poster that you’ll see of every active astronaut and we keep that around because that’s who we’re doing this for. Those are the folks that we’re supporting. That’s the reason why we’re doing this.

And that, yeah, we, as humanity want to get to Mars and do the cool stuff and all that, but we’re really doing it for the people involved. The safety and wellbeing of those crew members.

And I think that actually really helps put it into perspective–exactly why we do what we do. And when we have the hard days and the long hours, sometimes, we try not to, we try to take a healthy balance, but there are a few long days, that you have that perspective to look back on of this is why I'm doing it, this is where I'm contributing, this is the betterment of us as a people, that kind of sense behind it. And I think that's what's really unique about NASA … we're going to explore it for the betterment of humanity kind of feeling. To some degree, that's why a lot of people end up here, and I think definitely, myself included.”

Future implications and limitations

This study has supported and advanced previous findings on awe narrative-related themes, making a unique contribution to both awe research and to phenomenological and narrative methodologies. That withstanding, the study is not without limitations. Firstly, while the sample size is consistent with other IPA studies and recommendations (Smith and Osborn, 2004; Smith et al., 2009; Smith and Nizza, 2022), it is important to state that these findings are unique to the group studied and are not intended to be indicative of, or necessarily applicable to, a wider audience. While not the intention or within the scope of this study, a larger sample and broader examination of awe narratives with leaders, especially with NASA and other high-stress, high-pressure professionals, could provide additional empirical evidence to support individuals in their important work.

Next, these findings are indicative of the specific moment in time they participated in the study. Additional research can expand on these findings by conducting interview interventions at intervals (e.g., every 3 months) while incorporating quantitative measures to assess impact on both professional and personal wellbeing in a mixed-methods design. Considering awe is a complex emotion, it is necessary to continue researching it using diverse qualitative and quantitative methodologies.

Conclusion

Narrative research has demonstrated its potential to support the wellbeing of the individual, as well as those exposed to their stories. This study advances previous research by showing that awe narratives can serve as an evidenced-based, practical, non-therapeutic intervention to support the public and, in particular, NASA leaders, including healthcare professionals, not only in potentially strengthening their professional skills but also in enhancing their personal lives.

These findings are promising by demonstrating that awe-based narratives can act as a gateway to other resilience practices such as cognitive reappraisal, gratitude, hope and optimism, meaning and purpose in life, and social connectedness. In doing so, they offer an opportunity to enhance both professional leadership abilities and overall mental health. The presence of these resilience themes is evidenced through individual participant stories, in which their humanity and dignity are not reduced to generalized categories. Instead, each participant’s experience is honored by including narrative evidence to support each theme. These themes can be explored outside this specific group of NASA leaders with the possibilities to further examine this with others, such as with astronauts as part of their space missions (pre, during, and after) as well as analog environments, both which present exciting future opportunities.

The complex nature of awe is further revealed through these narratives, which show that awe, and the resilience practices it connects with, does not occur in isolation. Rather, the stories reveal an intertwined tapestry, in which, for the purposes of this study, awe can be that first thread.

Finally, this last story from a NASA leader serves as a reminder that the awe narratives we craft can shape our lives by offering us an opportunity to reflect on what we have to be grateful for, to recognize what has been accomplished, to find meaning and purpose in our lives, to invigorates hope and optimism by knowing we are building a positive future for ourselves and others, and to acknowledging our significant social connections:

“[Awe is] when I creep up to the top deck of our ship in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, and I stand there and I'm by myself, and I know there's not going to be anybody else out there. And it's just all the sounds, all the smells. Everything is overwhelming. I am surprised by the moment because I did not know that I could feel like that anymore. And yet, every time I go into the field, or even in what would be described as mundane situations on a day-to-day basis, there are these moments that I am overwhelmed and I am inspired. And, I love it. That's awe.”

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board, Lipscomb University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adler, J. M. (2012). Living into the story: agency and coherence in a longitudinal study of narrative identity development and mental health over the course of psychotherapy. J. Personality Soc. Psychol. 102 (2), 367–389. doi:10.1037/a0025289

Allen, S (2018). The science of awe [white paper]. Greater good science center at UC Berkeley), Available online at: https://ggsc.berkeley.edu/images/uploads/GGSC-JTF_White_Paper-Awe_FINAL.pdf (Accessed September 27, 2025).

American Psychological Association (APA) (2020). Building your resilience. Available online at: https://www.apa.org/topics/resilience/building-your-resilience (Accessed September 27, 2025).

Arone, A., Ivaldi, T., Loganovsky, K., Palermo, S., Parra, E., Flamini, W., et al. (2021). The burden of space exploration on the mental health of astronauts: a narrative review. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 18 (5), 237–246. doi:10.36131/cnfioritieditore20210502

Aten, J. D. (2021). The impact of human purpose on resiliency. Psychol. Today. Available online at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/hope-resilience/202103/the-impact-of-human-purpose-on-resiliency (Accessed September 27, 2025).

Atkinson, R. (2002). “The life story interview,” in Handbook of interview research: context and methods. Editors J. F. Gubrium, and J. A. Holstein (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications).

Bai, Y., Maruskin, L. A., Chen, S., Gordon, A. M., Stellar, J. E., McNeil, G. D., et al. (2017). Awe, the diminished self, and collective engagement: universals and cultural variations in the small self. J. Personality Soc. Psychol. 113 (2), 185–209. doi:10.1037/pspa0000087

Bonanno, G. A. (2005). Resilience in the face of potential trauma. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 14 (3), 135–138. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00347.x

Bonanno, G. A. (2021). The resilience paradox. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 12 (1), 1942642. doi:10.1080/20008198.2021.1942642

Bonner, E. T., and Friedman, H. L. (2011). A conceptual clarification of the experience of awe: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Humanist. Psychol. 39 (3), 222–235. doi:10.1080/08873267.2011.593372

Britt, T. W., Adler, A. B., and Fynes, J. (2021). Perceived resilience and social connection as predictors of adjustment following occupational adversity. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 26 (4), 339–349. doi:10.1037/ocp0000286

Butina, M. (2015). A narrative approach to qualitative inquiry. Clin. Laboratory Sci. 28 (3), 190–196. doi:10.29074/ascls.28.3.190

Carr, A. (2000). “Michael White's narrative therapy,” in Clinical Psychology in Ireland, Volume 4. Family therapy theory, practice, and research. Editor A. Carr (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press), 15–38.

CDC Social Connection (2024). Improving social connections. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/social-connectedness/improving/index.html (Accessed September 27, 2025).

Centor, R. M. (2007). To be a great physician, you must understand the whole story. Medscape General Med. 9 (1), 59. Available online at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1924990/ (Accessed September 27, 2025).

Chang, B., Huang, J., and Fang, J. (2024). The awe promotes prosocial behavior: the mediating role of psychological resilience. Curr. Psychol. 43, 36933–36943. doi:10.1007/s12144-024-07123-w

Charon, R. (2001). The patient-physician relationship. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA 286 (15), 1897–1902. doi:10.1001/jama.286.15.1897

Charon, R. (2016). “A framework for teaching close reading,” in The principles and practice of narrative medicine. Editors R. Charon, S. DasGupta, N. Hermann, C. Irvine, R. R. Marcus, and E. R. Colón (New York, NY: Oxford Academic), 180–207. doi:10.1093/med/9780199360192.001.0001

Chen, S. K., and Mongrain, M. (2020). Awe and the interconnected self. J. Posit. Psychol. 16 (6), 770–778. doi:10.1080/17439760.2020.1818808

Chen, Y., Hu, F., Xiao, Q., and Liu, Z. (2025). The shock of Awe experience to our soul is more directly on cognitive well-being than affective well-being. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 10619. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-95435-7

Chirico, A., Cipresso, P., Yaden, D. B., Biassoni, F., Riva, G., and Gaggioli, A. (2017). Effectiveness of immersive videos in inducing awe: an experimental study. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 1218. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-01242-0

Cicchetti, D. (2010). Resilience under conditions of extreme stress: a multilevel perspective. World Psychiatry 9 (3), 145–154. doi:10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00297.x

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cuzzolino, M. P. (2021). “The awe is in the process”: the nature and impact of professional scientists’ experiences of awe. Sci. Educ. 105, 681–706. doi:10.1002/sce.21625

Danvers, A. F., and Shiota, M. N. (2017). Going off script: effects of awe on memory for script typical and -irrelevant narrative detail. Emotion 17 (6), 938–952. doi:10.1037/emo0000277

DasGupta, S. (2008). Narrative humility. Lancet 371 (9617), 980–981. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(08)60440-7

Dawar, R., Estelamari, R., Kunal, G., Deukwoo, K., and Penedo, F. J. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on well-being and work-related burnout among healthcare workers at an academic center. J. Clin. Oncol. 39 (15), 11019. doi:10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.11019

De Vivo, I. (2024). The new science of optimism and longevity. The MIT Press Reader. Available online at: https://thereader.mitpress.mit.edu/the-new-science-of-optimism-and-longevity/ (Accessed September 27, 2025).

Dingfelder, S. F. (2011). Our stories, ourselves. Monit. Psychol. 42 (1), 42. Available online at: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2011/01/stories (Accessed September 27, 2025).

Emmons, R. (2010). Why gratitude is good. Greater Good. Available online at: https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/why_gratitude_is_good.

Emmons, R. A., and Mishra, A. (2011). “Why gratitude enhances well-being: what we know, what we need to know,” in Designing positive psychology: taking stock and moving forward. Editors K. M. Sheldon, T. B. Kashdan, and M. F. Steger (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 248–262. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195373585.003.0016

Frank, A. W. (2010). Letting stories breathe: a Socio-narratology. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Frechette, J., Bitzas, V., Aubry, M., Kilpatrick, K., and Lavoie-Tremblay, M. (2020). Capturing lived experience: methodological considerations for interpretive phenomenological inquiry. Int. J. Qual. Methods 19, 1609406920907254–12. doi:10.1177/1609406920907254

Gibson, N., and Heyman, I. (2014). “Narrative therapy,” in Social work – an introduction. Editors J. Lishman, C. Yuill, and J. Brannan (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications), 308–319.

Gray, D. P. (2025). Learning the craft - general practice stories. J. R. Soc. Med. 118 (4), 121–125. doi:10.1177/01410768251317087

Graziosi, M., and Yaden, D. (2019). Interpersonal awe: exploring the social domain of awe elicitors. J. Posit. Psychol. 16, 263–271. doi:10.1080/17439760.2019.1689422

Hall, S. (2023). A mental-health crisis is gripping science - toxic research culture is to blame. Nature 617 (7962), 666–668. doi:10.1038/d41586-023-01708-4

Hanson, R., and Hanson, F. (2018). Resilient: how to grow an unshakeable core of calm, strength, and happiness. New York, NY: Harmony.

Hazell, C. M., Niven, J. E., Chapman, L., Roberts, P. E., Cartwright-Hatton, S., Valeix, S., et al. (2021). Nationwide assessment of the mental health of UK Doctoral Researchers. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 8, 305. doi:10.1057/s41599-021-00983-8

Hill, J. (2022). The narrative therapy workbook: deconstruct your story, challenge unhealthy beliefs, and reclaim your life. Oakland, CA: Calisto.

Hlava, P., Elfers, J., McGregor, D. C., Arreguin, S., and Sharpe, F. (2023). From wonder to transformation: the lived experience of profound awe. J. Humanist. Psychol. 1–12. doi:10.1177/00221678231211972

Hooker, S. A., Post, R. E., and Sherman, M. D. (2020). Awareness of meaning in life is protective against burnout among family physicians: a CERA study. Fam. Med. 52 (1), 11–16. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.562297

Hou, J. Z. (2023). “Sharing is caring”: participatory storytelling and community building on social Media amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Behav. Sci. doi:10.1177/00027642231164040

Hunt, N. (2023). Applied narrative psychology. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Josselson, R., and Hammack, P. L. (2021). Essentials of narrative analysis. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Josselson, R. (2011). “Bet you think this song is about you”: whose narrative is it in narrative research? Narrat. Matters 1 (1), 33–51.

Kanas, N. (1998). Psychosocial issues affecting crews during long-duration international space missions. Acta Astronaut. 42 (1-8), 339–361. doi:10.1016/S0094-5765(98)00130-1

Kaur Dhillon, J. (2025). The impact of awe and transcendence experience on mental resilience. Int. J. Innovative Sci. Res. Technol. 10 (6), 672–684. doi:10.38124/ijisrt/25jun368

Keltner, D. (2023). Awe: the new science of everyday wonder and how it can transform your life. New York, NY: Penguin Press.

Keltner, D., and Haidt, J. (2003). Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cogn. Emot. 17, 297–314. doi:10.1080/02699930302297

Landon, L. B., Marquez, J. J., and Salas, E. (2023). Human factors in spaceflight: new progress on a long journey. Hum. Factors 65 (6), 973–976. doi:10.1177/00187208231170276

Lanocha, N. (2021). Lessons in stories: why narrative medicine has a role in pediatric Palliative care training. Children 8 (5), 321. doi:10.3390/children8050321

Launer, J. (2016). Conversations inviting change: narrative practice in health care. MedicinaNarrativa.eu. Available online at: https://www.medicinanarrativa.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/John-Launer-Explanation-conversation-inviting-change.pdf (Accessed September 27, 2025).

Launer, J. (2018). Narrative-Based practice in health and social care. 2nd Ed. Oxfordshire, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Launer, J. (2024). John Launer: letting patients’ stories breathe. BJM 384, q83. doi:10.1136/bmj.q83

Lazarus, A. (2024). Escaping the tyranny of academic writing for the narrative. Healthc. Adm. Leadersh. and Manag. J. 2 (2), 79–81. doi:10.55834/halmj.6350431734

Liu, Q., Zhou, R., Zhao, X., Chen, X., and Chen, S. (2016). Acclimation during space flight: effects on human emotion. Mil. Med. Res. 3, 15. doi:10.1186/s40779-016-0084-3

Loy, M., and Kowalsky, R. (2024). Narrative medicine: the power of shared stories to enhance inclusive clinical care, clinician well-being, and medical education. Perm. J. 28 (2), 93–101. doi:10.7812/TPP/23.116

Lutz, A., Jha, A. P., Dunne, J. D., and Saron, C. D. (2015). Investigating the phenomenological matrix of mindfulness-related practices from a neurocognitive perspective. Am. Psychol. 70 (7), 632–658. doi:10.1037/a0039585

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic. Resilience processes in development. Am. Psychol. 56 (3), 227–238. doi:10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227

McAdams, D. P. (2001). The psychology of life stories. Rev. General Psychol. 5 (2), 100–122. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.5.2.100

McAdams, D. P., and McLean, K. C. (2013). Narrative identity. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 22 (3), 233–238. doi:10.1177/0963721413475622

Meevissen, Y. M., Peters, M. L., and Alberts, H. J. (2011). Become more optimistic by imagining a best possible self: effects of a two week intervention. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 42 (3), 371–378. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2011.02.012

Monroy, M., and Keltner, D. (2023). Awe as a pathway to mental and physical health. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 18 (2), 309–320. doi:10.1177/17456916221094856

Morgan, A. (2000). What is narrative therapy? An easy-to-read introduction. Adelaide, Australia: Dulwich Centre Publications.

Morioka, M., and Nomura, H. (2021). Editorial: narrative-based approaches in psychological research and practice. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 63 (4), 231–238. doi:10.1111/jpr.12382

Murray, M., and Sargeant, S. (2011). “Narrative psychology,” in Qualitative research in mental health and psychotherapy: a guide for students and practitioners. Editors D. Harper, and A. R. Thompson (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley and Sons).

Narrative-Based Medicine Lab (n.d.). Customized program topics and Speakers. Available online at: https://narrativebasedmedicine.ca/customized-program/topics-speakers/ (Accessed September 27, 2025).

Nash, W., Erondu, M., and Childress, A. (2023). Expanding narrative medicine through the collaborative construction and compelling performance of stories. J. Med. Humanit. 44 (2), 207–225. doi:10.1007/s10912-022-09779-6

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) (2024). Risk factors for stress and burnout. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/healthcare/risk-factors/stress-burnout.html (Accessed September 27, 2025).

Nicholls, H., Nicholls, M., Tekin, S., Lamb, D., and Billings, J. (2022). The impact of working in academia on researchers’ mental health and well-being: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. PloS one 17 (5), e0268890. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0268890

O'Higgins, M., Rojas, L. A., Echeverria, I., Roselló-Jiménez, L., Benito, A., and Haro, G. (2022). Burnout, psychopathology and purpose in life in healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health 10, 926328. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.926328

Ostafin, B. D., and Proulx, T. (2020). Meaning in life and resilience to stressors. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping 33 (6), 603–622. doi:10.1080/10615806.2020.1800655

Pan, X., and Jiang, T. (2024). A tale of self-transcendence: awe fosters optimism. J. Posit. Psychol. 20, 616–630. doi:10.1080/17439760.2024.2394458

Petrie, K., Crawford, J., Baker, S. T. E., Dean, K., Robinson, J., Veness, B. G., et al. (2019). Interventions to reduce symptoms of common mental disorders and suicidal ideation in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 6 (3), 225–234. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30509-1

Piff, P. K., Dietze, P., Feinberg, M., Stancato, D. M., and Keltner, D. (2015). Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior. J. Personality Soc. Psychol. 108 (6), 883–899. doi:10.1037/pspi0000018

Polkinghorne, D. E. (1995). Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 8 (1), 5–23. doi:10.1080/0951839950080103

Pollock, D. (2001). “Physician autobiography: narrative and the social history of medicine,” in Narrative and the cultural construction of illness and healing. Editors C. Mattingly, and L. C. Garro (Oakland, CA: University of California Press).

Regan, A., Walsh, L. C., and Lyubomirsky, S. (2023). Are some ways of expressing gratitude more beneficial than others? Results from a randomized controlled experiment. Affect. Sci. 4, 72–81. doi:10.1007/s42761-022-00160-3

Reivich, K., and Shatté, A. (2003). The resilience factor: 7 keys to finding your inner strength and overcoming life’s hurdles. New York, NY: Harmony.

Riepenhausen, A., Wackerhagen, C., Reppmann, Z. C., Deter, H.-C., Kalisch, R., Veer, I. M., et al. (2022). Positive cognitive reappraisal in stress resilience, mental health, and well-being: a comprehensive systematic review. Emot. Rev. 14 (4), 310–331. doi:10.1177/17540739221114642

Rutledge, P. (2016). “Everything is story: telling stories and positive psychology,” in Exploring positive psychology: the science of happiness and well-being. Editors E. M. Gregory, and P. B. Rutledge (London, United Kingdom: Bloomsbury). Available online at: https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/exploring-positive-psychology-9781610699396/.

Schneider, K. J. (2009). Awakening to awe: personal stories of profound transformation Inc. Lanham, MD: Jason Aronson.

Shiota, M. N. (2021). Awe, wonder, and the human mind. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1501 (1), 85–89. doi:10.1111/nyas.14588

Shiota, M. N., Keltner, D., and Mossman, A. (2007). The nature of awe: elicitors, appraisals, and effects on self-concept. Cognition Emot. 21 (5), 944–963. doi:10.1080/02699930600923668

Shoshani, A., and Hen, R. (2025). Enhancing mental health and resilience in war-affected youth: the impact of virtual reality-induced awe experiences. Comput. Hum. Behav. 171, 108707. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2025.108707

Smith, J. A., and Nizza, I. E. (2022). Essentials of interpretative phenomenological analysis. American Psychological Association. Washington, DC: Sage.

Smith, J. A., and Osborn, M. (2003). “Interpretative phenomenological analysis,” in Qualitative psychology: a practical guide to research methods. Editor J. A. Smith (London, United Kingdom: Sage), 51–80.

Smith, J. A., and Osborn, M. (2004). “Interpretative phenomenological analysis,” in Doing social psychology research. Editor G. M. Breakwell (Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing), 229–254.

Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., and Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method, and research. London, United Kingdom: Sage.

Southwick, S. M., and Charney, D. S. (2018). Resilience: the science of mastering life’s greatest challenges. 2nd ed. Cambridge. Available online at: http://assets.cambridge.org/97805211/95638/copyright/9780521195638_copyright_info.pdf.

Southwick, S. M., Bonanno, G. A., Masten, A. S., Panter-Brick, C., and Yehuda, R. (2014). Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. Eur. J. psychotraumatology 5, 25338. doi:10.3402/ejpt.v5.25338

Southwick, S., Wisneski, L., and Starck, P. (2021). Rediscovering meaning and purpose: an approach to burnout in the time of COVID-19 and beyond. Am. J. Med. 134 (9), 1065–1067. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2021.04.020

Stellar, J. E. (2021). Awe helps us remember why it is important to forget the self. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1501 (1), 81–84. doi:10.1111/nyas.14577

Stellar, J. E., Gordon, A., Anderson, C. L., Piff, P. K., McNeil, G. D., and Keltner, D. (2018). Awe and humility. J. Personality Soc. Psychol. 114 (2), 258–269. doi:10.1037/pspi0000109

Sturm, V. E., Datta, S., Roy, A. R. K., Sible, I. J., Kosik, E. L., Veziris, C. R., et al. (2020). Big smile, small self: awe walks promote prosocial positive emotions in older adults. Emotion 22, 1044–1058. doi:10.1037/emo0000876

Suttie, J. (2017). Four ways social support makes you more resilient. Greater Good. Available online at: https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/four_ways_social_support_makes_you_more_resilient (Accessed September 27, 2025).

Tabibnia, G. (2020). An affective neuroscience model of boosting resilience in adults. Neurosci. and Biobehav. Rev. 115, 321–350. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.05.005

Thompson, J. (2020). Warr;or21: a 21-day practice for resilience and mental health. Research Triangle Park, NC: Lulu Press.

Thompson, J. (2022a). Enhancing resilience: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of the Awe Project. J. Community Saf. Well-Being 7 (3), 93–110. doi:10.35502/jcswb.265

Thompson, J. (2022b). Awe narratives: a mindfulness practice to enhance resilience and wellbeing. Front. Psychol. Posit. Psychol. 13, 840944. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.840944

Thompson, J. (2022c). Awe: Helping leaders address modern policing problems. J. Community Saf. Well-Being 7 (2), 53–58. doi:10.35502/jcswb.239

Thompson, J. (2023a). NASA resilience and leadership: examining the phenomenon of awe. Front. Psychol. 14, 1158437. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1158437

Thompson, J. (2023b). Narrative Health: examining the relationship between the phenomenon of awe and resilience and well-being. J. Community Saf. Well-Being 8 (2), 85–98. doi:10.35502/jcswb.321

Thompson, J. (2023c). Police well-being interventions: using awe narratives to promote resilience: this article is related directly to the First European Conference on Law Enforcement and Public Health (LEPH) held in Umea, Sweden in May 2023. J. Community Saf. Well-Being 8 (4), 197–204. doi:10.35502/jcswb.337

Thompson, J. (2023d). Experiencing awe: an innovative approach to enhance investigations and wellness. The IACP Police Chief Magazine. Available online at: https://www.policechiefmagazine.org/experiencing-awe/ (Accessed September 27, 2025).

Thompson, J. (2024). New Zealand police leadership: a goal-focused and human-centered approach. The IACP Police Chief Magazine. Available online at: https://www.policechiefmagazine.org/nz-police-leadership/?ref=e87398455e045b5f79f566eaaa5afb3c (Accessed September 27, 2025).

Thompson, J. (2025a). Narrative psychology: examining the science of awe stories in fostering resilience and wellbeing. Thesis (PhD Doctorate). Scotland: Edinburgh Napier, University, School of Health and Social Care. Edinburgh.

Thompson, J. (2025b). Why we “craft“ the significance of narratives in aerospace healthcare and beyond. Space Education and Strategic Applications in press.

Thompson, J., and Drew, J. M. (2020). Warr;or21: a 21-day program to enhance first responder resilience and mental health. Front. Psychol. 11, 2078. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02078

Thompson, J., and Jensen, E. (2023). Hostage negotiator resilience: a phenomenological study of awe. Front. Psychology. 14, 1122447. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1122447

Thompson, J., and Launer, J. (2025). Illuminating humanity: narrative medicine practices for crisis negotiators. J. Police Crim. Psychol. doi:10.1007/s11896-025-09756-4

Thompson, J., Grubb, A. R., Ebner, N., Chirico, A., and Pizzolante, M. (2022). Increasing crisis hostage negotiator effectiveness: embracing awe and other resilience practices. Cardozo J. Confl. Resolut. 23 (3), 615–685. Available online at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/60a5863870f56068b0f097cd/t/62c5bb989716c4185529716a/1657125784611/CAC309_crop.pdf (Accessed September 27, 2025).

Usán Supervía, P., Salavera Bordás, C., and Murillo Lorente, V. (2020). Exploring the psychological effects of optimism on life satisfaction in Students: the mediating role of goal orientations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17 (21), 7887. doi:10.3390/ijerph17217887

Van Manen (1990). Research lived experience: human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. Albany, NY: Suny Press.

Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Cukrowicz, K. C., Braithwaite, S. R., Selby, E. A., and Joiner, T. E. (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol. Rev. 117 (2), 575–600. doi:10.1037/a0018697