- 1Bert S. Turner Department of Construction Management, College of Engineering, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, United States

- 2Planetary Science Laboratory, Department of Geology & Geophysics, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, United States

- 3Learning Analytics and Educational Technology, School of Education, College of Human Sciences & Education, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, United States

- 4Division of Computer Science & Engineering, College of Engineering, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, United States

- 5Virtual Production and Immersive Media, School of Theatre and School of Art, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, United States

Creating sustainable habitats on the Moon and Mars requires converging advances in construction technologies, human-robot collaboration (HRC), and workforce development. This paper synthesizes insights from a transdisciplinary workshop that focuses on three main themes: (1) trust-calibrated HRC systems for latency-laden and safety-critical tasks; (2) construction technology for extraterrestrial applications, for example, those challenges of dust mitigation, in-situ resource utilization (ISRU), and planetary protection; and (3) immersive and AI-assisted training that incorporates the necessary knowledge, skills, and abilities for the future-ready workforce. Participants involved in this transdisciplinary workshop identified regolith-based additive manufacturing, high-fidelity HRC testbeds, adaptive extended-reality (XR) training, and modular energy opportunities as near-term priorities. This study presents a converging roadmap that focuses on a series of prioritized, scalable steps over 1–15 years, incorporating technology, human, and ethical considerations to inform endeavors like the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Artemis Program and the European Space Agency (ESA) Moon Village concept. The framework positions extraterrestrial construction as a socio-technical endeavor by providing actionable steps toward sustainable extraterrestrial habitation.

Introduction

As humanity moves closer to establishing a permanent presence beyond Earth, designing and constructing safe, reliable, and scalable habitats will be among the biggest challenges of the 21st century. Designing, constructing, and maintaining habitats on the Moon and Mars is no longer in the realm of science fiction; in fact, many countries are currently involved in international programs to advance the development of extraterrestrial habitats. For example, NASA’s Artemis program is focused on returning humans to the lunar surface and establishing a sustainable base camp on the Moon by the end of this decade (Clinton Jr, 2025; NASA, 2021), and ESA’s Moon Village vision envisions an international multi-purpose settlement to support everything from science and industry to exploration and discovery (Wörner, 2016; Athanasopoulos, 2019). Similarly, China’s CNSA, in partnership with Roscosmos, has proposed the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) as a long-term multinational base (CNSA & Roscosmos, 2021; Xu et al., 2022), while India’s ISRO has demonstrated critical lunar landing and surface exploration capabilities with Chandrayaan-3, paving the way for future ISRU and habitat-focused missions (Indian Space Research Organisation, 2023). Japan’s JAXA continues to advance its Smart Lander for Investigating Moon (SLIM) and related programs to support sustainable lunar activities (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, 2024), and South Korea has successfully placed its Korea Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter (Danuri) into lunar orbit, providing essential reconnaissance data for future construction and resource utilization (Song et al., 2023; Korea Aerospace Research Institute, n.d.). Emerging actors in the Middle East are also investing in extraterrestrial exploration: the UAE’s Rashid Rover program contributes to lunar surface science and technology demonstration (Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Centre, n.d.), while Israel’s Beresheet mission, despite its crash landing, showcased the country’s growing capabilities in planetary exploration (NASA, 2019). Taken together, these initiatives clarify that extraterrestrial construction is not a peripheral activity but a core enabler of human expansion into deep space.

Constructing beyond the Earth requires reimagining construction technologies in environments where extreme temperature variation, either in microgravitational or reduced gravity contexts, high-energy radiation, and abrasive regolith material properties are the norm. Recent studies have underscored the role that in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) plays in reducing launch costs and associated mission risk by being able to produce structural materials on-site, using regolith to produce sulfur-based concrete and binders (Sacksteder and Sanders, 2007; Cesaretti et al., 2014; Tute and Goulas, 2024). Additive manufacturing, or “3D printing,” has been revealed to be a critical enabler of this vision, permitting the automated fabrication of shelters, landing pads, and radiation-shielding berms, with limited input from people (Khoshnevis et al., 2016; Netti and Bisharat, 2023; Banijamali et al., 2025). Projects such as ICON’s work with NASA’s Artemis Base Camp and ESA’s investigations of regolith sintering provide evidence at a relevant scale for the feasibility of these regolith-based construction technologies. Autonomous and semi-autonomous robotic systems, such as multi-agent excavation teams (e.g., NASA CraterGrader and similar robotic graders) and inspection robots, perform the essential functions to prepare and maintain extraterrestrial environments (Lee et al., 2023; Thangavelautham et al., 2017).

As robotic autonomy improves, human oversight and human-robot collaboration (HRC) will remain irreplaceable. Researchers have argued that humans’ critical roles include anomaly detection, making accurate judgments in unstructured environments, and assessing and managing risk in complex, safety-critical work (Xiao et al., 2025; Jafari et al., 2024; Sheridan, 2016). The need for HRC is compounded by human cognitive and operational limitations due to factors such as latency-laden teleoperation, notably in situations where direct human supervision requires extensive communication delays, such as on Mars, which may have delays between 21–23 min (Chappell et al., 2024). Suppose robotic autonomy plans are executed in a noticeably less robust manner. In that case, they may fail to meet trust-calibration with HRC adaptation—defined here as the adjustment of roles, responsibilities, and control between humans and robots based on context and operational workload—which ultimately dictates mission priorities as a whole. Suppose HRC processes are not designed with human-robot interactive dynamics in mind. In that case, the opportunity cost is inefficiency across multiple levels of the task hierarchy—for example, from strategic mission planning to operational execution—or even mission failure in high-stakes situations (e.g., outfitting a human habitat, lander assembly, or regolith excavation).

The human element involves more than just operations; it also includes the preparation of a future-ready workforce. We will need new skillsets that connect construction management to planetary sciences, robotics, systems engineering, and human factors for extraterrestrial construction. Research looking across analog missions, including Mars-500, NASA’s NEEMO underwater simulations, and the HI-SEAS habitat, illustrates the psychological fortitude, teamwork, and flexibility needed for long-duration activities in extreme environments with limited access to outside resources (Pagel and Choukèr, 2016; De la Torre et al., 2024). Recent research shows that using immersive extended-reality (XR) platforms and AI-enabled adaptive learning systems can improve technical competency and cognitive flexibility for training (Jeelani et al., 2017; Wang and Huang, 2025). However, despite these advancements, training pipelines for extraterrestrial construction are underdeveloped with limited integration among training for technical skills, psychosocial readiness, and interdisciplinary literacy.

Finally, construction activities in space may also face challenges related to ethics and regulatory structures, specifically about planetary protection. Current Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) guidelines (Kminek et al., 2020) were developed primarily to avoid samples being cross-contaminated with microscopic life originating from Earth (which presupposes the aim of observing the sample—or region—in a preserved context primarily for scientific missions) and not necessarily with the expectation of large-scale construction demands, like land excavation, material preparation, and initiating permanent human settlements (Kminek et al., 2022). While the goals of scientific discovery and extraterrestrial construction can coexist, we identify a need to modify existing protocols for what is an acceptable and safe form of development for extraterrestrial and terrestrial infrastructure, which also considers the different scaling conventions across differing nation-states.

In this context, there is an immediate need for effective transdisciplinary collaboration to combine technological advancement, human-robot collaboration, workforce development, and policy into a singular plan. Unlike multi- or interdisciplinary approaches, which focus on parallel or integrative academic perspectives, a transdisciplinary approach extends beyond disciplinary boundaries to incorporate industry, regulatory, and societal stakeholders in shaping solutions. This project responds to this need by applying a transdisciplinary workshop designed to critically engage with these themes, synthesize expert opinions, and develop actionable plans to advance extraterrestrial construction as a socio-technical system. The workshop identified three connected pillars:

1. Human-Robot Collaboration (HRC): Building trust-calibrated, adaptable frameworks for latency-laden and safety-critical construction tasks.

2. Extraterrestrial Construction Challenges: Prioritizing hazard mitigation, ISRU workflows, energy strategies, and planetary protection for sustainable habitats.

3. Future Workforce Training: Designing immersive, AI-driven, and resilience-oriented educational models to prepare a “future-ready” workforce for extraterrestrial construction, with training focused on developing technical competencies (e.g., robotics operations, ISRU processes, habitat assembly), as well as cognitive and psychosocial skills (e.g., adaptability, teamwork, and decision-making under uncertainty).

By integrating these pillars into a multi-phase roadmap, this study seeks to provide researchers, policymakers, and space agencies with practical guidance for shaping the next-generation of extraterrestrial construction initiatives.

Methodology

This study employed the Delphi Technique through a transdisciplinary workshop specifically designed to examine extraterrestrial design and operations. The Delphi Technique is a structured, iterative process used to gather expert consensus through multiple rounds of discussion and feedback, particularly effective for exploring complex, emerging topics (Linstone and Turoff, 1975; Stitt-Gohdes and Crews, 2004; Jafari et al., 2019; Hohmann et al., 2025).

The workshop adhered to established scholarly workshop conventions (Ørngreen and Levinsen, 2017), balancing sufficient structure with flexibility to allow participants to engage deeply with the multifaceted issues. By integrating a diverse group of academic and professional experts, the format enabled meaningful knowledge exchange and collaborative problem-solving relevant to the challenges facing extraterrestrial construction.

The workshop employed a multi-layered design consistent with Delphi principles. It began with expert panels organized by thematic areas, followed by facilitated question-and-answer sessions and breakout discussions to encourage detailed exploration. Subsequently, participants synthesized expert knowledge, evaluated current technologies, identified critical gaps, and collaboratively developed prioritized recommendations for research and deployment. This iterative process fostered convergence towards actionable strategic plans for advancing extraterrestrial construction as a socio-technical system.

The workshop was co-organized by the co-authors and hosted at Louisiana State University on 6 June 2025. The main goal of the workshop was to exchange and compile information to serve as a baseline for future collaborations and to establish a converging roadmap based on the previously described transdisciplinary framework to create sustainable habitats on the Moon and Mars. Experts were invited to present and provide feedback on three core subjects:

1. Human-Robot Collaboration (HRC) in Construction: This panel led by Drs. Carol Menassa at the University of Michigan, Reza Akhavian at San Diego State University and Masoud Gheirsari from the University of Florida; explored interactions between humans and robots, emphasizing psychological dimensions such as trust calibration in robotic systems, error detection mechanisms, real-time risk management, and the design of effective protocols for collaborative autonomy. Academic and industry experts critically evaluated the state of current technologies, drawing attention to both their potential and their limitations for extraterrestrial applications.

2. Future Extraterrestrial Construction: This panel led by Drs. Christopher Carr from Georgia Institute of Technology and Patrick Suermann from Texas A&M University examined construction-specific challenges unique to lunar and Martian environments. Discussions addressed hazard prioritization (e.g., regolith dust, radiation, and seismic risks), innovative use of in-situ resources such as regolith-based additive manufacturing, sustainable energy strategies including geothermal systems (Zhang et al., 2021; Soni et al., 2024), and the development of decision-making frameworks tailored to the operational realities of extraterrestrial construction. Participants also critically engaged with planetary protection measures, recognizing extraterrestrial building activities’ ethical and regulatory implications.

3. Future Workforce Training: This panel led by Drs. Maya Georgiva at the New School, Shinhee Jeong at the University of Texas at Tyler, and Sean Hauze at San Diego State University; focused on identifying essential skills and competencies for the future extraterrestrial workforce. Panelists explored immersive simulation methodologies, adaptive AI-driven learning systems, scenario-based education, and psychological resilience training, emphasizing the importance of integrating these tools into transdisciplinary education programs to prepare a “future-ready” construction workforce.

All eight participants were intentionally chosen to ensure broad transdisciplinary expertise and ongoing interest in research areas that directly intersect with the themes examined in the workshop. This set of expertise allowed the workshop to provide a broad representation of perspectives around the technical considerations and work challenges associated with robotic construction while giving strong representation to the cognitive and psychosocial factors that underpin HRC.

The morning sessions began with structured thematic panels, utilizing multiple short presentations by relevant experts, followed by moderated Q&A, facilitating a cross-pollination of ideas amongst participants. The afternoon breakout sessions transitioned to facilitated discussions, where participants engaged in brainstorming, scenario planning, and discussions to identify major challenges, knowledge gaps, and future research needs. The day concluded with strategic planning sessions aimed at co-creating an approach for enhancing extraterrestrial construction and corresponding future workforce development.

We collected data using multiple complementary methods. In-depth documentation of the experts’ perspectives was accomplished through structured, facilitated panel presentations and moderated expert discussions. Facilitated break-out sessions allowed attendees the ability to engage in interactive exercises that generated a ranked set of priorities for hazards, training needs, and research questions. Strategic discussions contributed to a synthesis of these insights into a multi-phased, actionable roadmap. Audio was recorded for all of the sessions, and in addition, independent observers took detailed field notes providing rich documentation of the discussion that took place. Products that originated from the breakout sessions, which included a completed hazard ranking template with marked ranking as well as competency matrices, were digitized for future analysis. The qualitative data were thematically analyzed based on Braun and Clarke’s (2006) guidance for thematic analysis. Two researchers independently coded the workshop transcripts, field notes, and artifacts and identified themes in HRC, construction issues, and workforce development. Any differences in the coding process were resolved collaboratively, maintaining analytical rigor.

Results and discussions

The workshop provided interrelated insights covering HRC, challenges in building on extraterrestrial locales, and workforce training demands. These insights represented the variation based on the participants’ level of expertise and the urgency behind addressing these challenges in the near-term context of lunar and Martian missions. Significantly, these insights were not a list of unconnected observations, but a cohesive vision of how these areas must come together for extraterrestrial construction in a sustainable, safe, and scientifically relevant way.

Human-robot interaction: trust, adaptability, and cognitive load

In their first panel, participants repeatedly conveyed that extraterrestrial construction will not, and perhaps cannot, be conducted in complete autonomy. Instead, it will rely on high-stakes HRC, where human oversight, trust calibration, and adaptability in decision-making will be equally critical to precision in robotic performance. This reflects decades of theoretical and empirical literature on human-automation teaming, which has consistently shown that uncalibrated trust (over- or under-trust) merely degrades performance and safety (Lee and See, 2004; Campagna and Rehm, 2025).

During discussions, participants uncovered a persistent tension between potential autonomic processes, the demands imposed by the processes themselves, and the cognitive demands placed on human operators.

A significant priority identified within cognitive load management was teleoperation during extraterrestrial construction, wherein operators may be required to supervise multiple interrelated semi-autonomous systems and procedures from a remote-control center. This may lead to cognitive overload, which may increase the risk of task failure. This issue becomes more pronounced during teleoperation through latency, such as for missions to Mars that have a round-trip delay in excess of 20 min. If the broader literature on teleoperation through deep-space analogs may be applied, under latency, operator cognitive load would increase while situational awareness would decrease, resulting in increased operator errors (Chappell et al., 2024). To lessen these issues, the participants called for a layered framework of autonomy that adapts to task complexity and operator state. In this framework, lower layers of autonomy manage routine and repetitive operations, intermediate layers adapt procedures in response to environmental changes, and higher layers escalate ambiguities or safety-critical events to human operators. This structure mirrors Sheridan’s (2016) adaptive automation concept and aligns with NASA’s evolving autonomy-in-supervision models in Artemis missions, where routine autonomy is balanced with human oversight at critical junctures.

Extraterrestrial construction: hazards, ISRU, and planetary protection

The discussion for the second panel focused on the special geotechnical, operational, and ethical challenges generated by building off-world.

Dust hazards (e.g., every fine (finer than 20 microns), charged regolith particle or fine silt in the Wentworth scale (Slabic et al., 2024) for extraterrestrial terrains that can damage equipment, permeate habitats, and damage health) were identified as the most overlooked but possibly mission-critical threat. This concern represents data from Apollo missions indicating that lunar dust caused extensive abrasion of extra-vehicular activity (EVA) suits, seals, and tools, as referenced in current publications by NASA’s lunar surface innovation consortium, emphasizing that dust mitigation could be the make-or-break factor for long-duration surface operations (Werkheiser et al., 2022; Freeman, 2024).

Also emphasized were the combined threats of thermal extremes and radiation, with discussion suggesting early-faced infrastructure should first focus on shielding and energy buffers before beginning to build habitats. This aligns with NASA plans for Artemis Base Camp, which advocates “infrastructure-first” (Clinton Jr, 2025; NASA, 2021) by prioritizing the regolith shielding berm every time, and developing a subsurface for habitation to reduce the risk of cosmic radiation and temperature changes.

The notion of in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) captured much of the conversation. Regolith-based additive manufacturing, particularly with sulfur concrete or geopolymer binders, has the potential to be a scalable means of reducing payload mass by up to 90% (Sacksteder and Sanders, 2007; Cesaretti et al., 2014; Banijamali et al., 2025). Other participants acknowledged that these materials are structurally acceptable as well as workable with current robotic fabrication techniques, especially contour crafting (Khoshnevis et al., 2016; Netti and Bisharat, 2023; Netti, 2025). Still, participants emphasized that a more consistent taxonomy of extraterrestrial construction processes is needed so that another type of breakdown does not prevent Mission Control from communicating with other projects as it did with the Mars Climate Orbiter failure; that mission was lost because of disparate units and protocols (NASA Mars Climate Orbiter Mishap Investigation Board, 1999).

There was an added ethical component that influenced these discussions. Many members recognized that COSPAR’s current planetary protection guidelines were satisfactory for science missions, but not necessarily applicable to operational construction and habitation scenarios. Delegates suggested that any mission-specific modifications should restore some of the operational flow to the construction and habitat effort, to account for the scientific integrity of the planetary exploration mission (Kminek et al., 2022).

Workforce training: beyond technical skills

The third panel shifted the conversation from technologies to their users and surfaced major gaps in current training pipelines. Participants claimed that extraterrestrial construction will need a new kind of professional, someone who is equally fluent in robotics, systems thinking, and emotional resilience. The idea of “future-ready” workers resonates with Jafari et al. (2024), who were calling for “human-robot collaboration” competencies to be integrated in construction education.

Immersive extended-reality (XR) environments were presented as impactful ways to develop these skills. XR platforms can simulate reduced-gravity assembly, emergency protocols, or long-duration workflows, whilst providing emotionally engaging and repeatable simulations of these unique environments. Such simulations, already in use, for example, in construction safety training (Jeelani et al., 2017; Dodoo et al., 2025), may be adapted to prepare crews to address the physical and psychological demands of extraterrestrial missions.

Additionally, participants endorsed AI-driven adaptive learning platforms, which automatically adjust content difficulty, involve learners in real time, and this model has improved cognitive adaptability in high-complexity environments such as aviation and healthcare (Wen et al., 2025). While participants acknowledged the importance of technical proficiency, they stressed that it alone is inadequate; effective preparation for extraterrestrial construction also requires emotional resilience, purposeful engagement, and interdisciplinary literacy. Participants suggested employing narrative-based training—placing learners into mission-relevant scenarios involving storytelling—to promote meaning-making and psychological endurance. This method aligns with analog missions’ principles seen in HI-SEAS and NEEMO, where narrative framing/attention and purpose-driven tasks are useful in increasing the cohesion and resilience of crews in isolation.

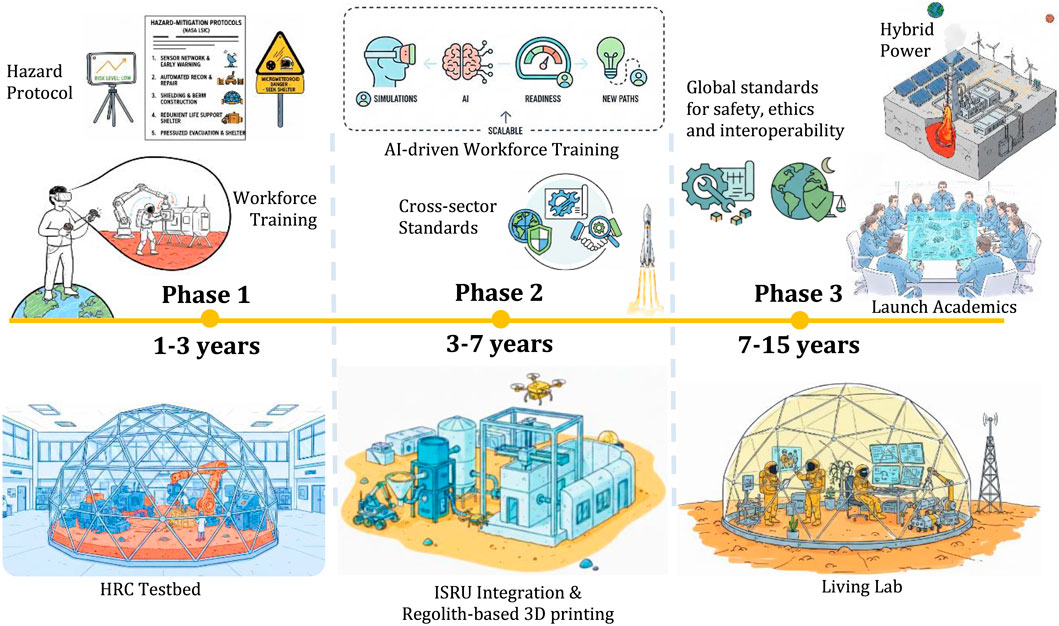

Converging roadmap

Discussions at the workshop culminated in the design of a converging roadmap for developing extraterrestrial construction, workforce development, and HRC. Instead of considering these areas individually, participants recognized that in order to make meaningful progress, we need to consider them as pillars of an interdependent system: both technical advances in construction and developing HRC frameworks and workforce development need to happen together. This approach matches the orientation of prior and emerging international exploration programs, including the NASA Artemis program, the Moon-to-Mars strategies, and the ESA Moon Village model of collaboration and phased development of capabilities (Clinton Jr, 2025; NASA, 2021; Athanasopoulos, 2019; Wörner, 2016).

Phase 1: immediate priorities (1–3 years)

The participants identify an immediate priority to build the infrastructure (technological and human) to enable scalable construction beyond Earth. The first step is to develop high-fidelity HRC “testbeds” that will allow test crews to experience the psychological and human factors of working in a construction setting in remote environments with latency. Testbeds need to account for both communication latency, regolith handling, and dynamic scheduling of tasks, as well as personnel and safety-critical actions, enabling operators to rehearse their workflows in mimetic contexts that approximate lunar or Martian construction work. The participants recommend using XR prototypes for workforce training to supplement testbed development. These immersive frameworks will allow operators to train for the teleoperation skill sets, situational awareness development, and emergency preparedness protocols, thereby developing knowledge of complicated workflows that will be employed in other environments prior to in-field deployment. Emphasizing simulation training is reminiscent of NASA’s current use of Virtual Reality Training Environments (VRTE) in training Artemis astronauts, but can be expanded to the broader construction and engineering crews that will work in construction settings beyond Earth. Lastly, the group recommends as a priority developing best practice protocols to mitigate hazards, especially with regard to dust abrasion, radiation shielding, and thermal buffering. These protocols should be clearly defined in the initial phases of the deep-space Artemis missions and utilize the foundation of NASA’s Lunar Surface Innovation Consortium’s work to ensure that mitigation protocols are tested and executed under mission-relevant conditions (Werkheiser et al., 2022; Freeman, 2024).

Phase 2: mid-term integration (3–7 years)

This phase is focused on operationalizing the technologies and frameworks that were piloted in Phase 1. Central to this phase is integrating in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) into modular construction workflows to advance the transitive development of regolith-based additive manufacturing from laboratory opportunities to field-deployable systems. Participants stress the substantial potential of geopolymer and sulfur-concrete technologies as they can eliminate payloads dependent on Earth and provide possible structurally sound cases for early habitats and landing pads. In parallel, AI-driven adaptive training ecosystems should be scaled to incorporate performance analytics to customize learning pathways and dynamically measure operator readiness. The adaptive systems will develop data-driven feedback loops while re-evaluating the training content due to crew performance and previous actions and decisions made in simulations and real-world operations. This phase will also develop planetary protection protocols to achieve the goal of scientific integrity without sacrificing the practicality of building infrastructure. Participants emphasize that the existing COSPAR guidelines (Kminek et al., 2020) are based on robotic exploration, which will need to evolve since they do not justify allowing large-scale excavation, processing, and construction without human settlement. Importantly, but not specifically required, both human and robotic missions can be executed in Phase 2 alongside cross-sector partnerships to integrate space agencies, construction technology companies, and academic research centers in developing common interoperable standards for robotic platforms, training ecosystems, and construction taxonomies. These partnerships will create a shared operational framework, reducing risks of redundancy and incompatibility across international programs.

Phase 3: long-term sustainability (7–15 years)

This phase of the roadmap consists of a clear change from demonstrating capabilities to institutionalizing capabilities and scaling. Several participants anticipate the development of transdisciplinary academies combining construction management, planetary sciences, robotics, and human factors that will essentially be a pipeline for future-ready professionals who will practice through a program that will be embedded in a system (e.g., the cultivation of expertise in extraterrestrial construction would be systematic rather than ad hoc). At the technical level, operationalizing geothermal energy strategies and hybrid power systems will increase resilience during the long lunar nights and Martian dust storms. Hybrid power systems would complement solar-based power systems, and together, these diverse strategies will position humans to lessen their susceptibility to environmental variability and meet the energy demands of an expanding settlement. In addition to the recommendations for research and development, this stage will require the development and articulation of global standards for extraterrestrial construction and include safety protocols, ethics, and interoperability requirements. Ideally, these standards will be established by consortia of nations following the guidelines organized by COSPAR principles (Kminek et al., 2020), allowing for oversight of the rapid market commercialization and expansion of off-Earth construction before ethics and scientific oversight can keep pace. The participants also propose the establishment of “living laboratories” on the Moon or in terrestrial analog environments, as well as semi-permanent research locations. Constant testing environment opportunities for construction and robotic workflows, as well as opportunities for psychosocial training, will lead to more thoughtful consideration of how a permanent presence on the Moon or Mars will link research to architecting the long-term mission.

Importantly, every phase connects across the technical, human, and ethical dimensions (see Figure 1). For instance, trust-calibrated HRC frameworks cannot come to fruition without shared advancement in workforce training and adaptive education. Likewise, ISRU-enabled construction requires ongoing innovation through materials science, as well as a systems-level regulatory and ethical rethinking of planetary protection. These interdependencies highlight the importance of systems thinking for understanding extraterrestrial construction research and policy; in essence, advancements in one area are reliant on concurrent advancements across the others. The roadmap describes a multi-phase, actionable framework for approaches to be guided by, in support of internationally sustainable, equitable, and scientifically verifiable extraterrestrial habitation - through embedding training, ethics, and human-robot integration within the technological development cycle.

Figure 1. Converging roadmap for developing extraterrestrial construction, workforce development, and HRC.

Conclusion

The present study emphasizes that sustainable construction practices beyond Earth are not just an engineering problem, but instead a socio-technical problem that necessitates co-evolutionary processes involving advanced technologies, HRC systems, and worker preparations. The transdisciplinary workshop demonstrated a few immediate priorities: the phasing threats posed by regolith dust and radiation; HRC systems calibrated for trust; scaling ISRU for construction projects; and building immersive, adaptive training in workforce preparation systems.

The converging roadmap produced through this process provides a phased, actionable plan to advance off-world construction opportunities. It establishes immediate priorities for deploying high-fidelity HRC testbeds, extended-reality (XR) training prototypes, and enhancements to hazard mitigation protocols for missions like Artemis III. It provides defined mid-term priorities toward integrating ISRU workflows, scaling AI-directed adaptive learning ecosystems, and adjusting planetary protection best practices to govern a balance of infrastructure pragmatics and scientific integrity. Long-term priorities include institutionalizing transdisciplinary training academies, operation of hybrid energy systems (including geothermal strategies), and formalizing a common understanding of global standards for safe, ethical, and interoperable construction off of Earth.

These implications are considerable for policymakers, space agencies, academic institutions, and industry professionals. For policymakers, the roadmap highlights the importance of amending planetary protection regulations in order to advance large-scale construction programs without losing their scientific objectives. For space agencies like NASA and ESA, the findings indicate the need for coordinated cross-sector partnerships to develop interoperable standards for construction technologies and training programs. For academics and professionals in industry, the findings indicate the need to develop forward-thinking curricula that encompass technical, cognitive, and psychosocial competency in response to future living conditions in extraterrestrial environments.

In conclusion, developing extraterrestrial construction requires a systems-thinking framework that recognizes the interconnections between robotic self-management, human factors, and ethical consideration—rather than addressing them as independent problems. This study provides a framework for constructing extraterrestrial settlements that are technically viable, sustainably operational, and ethically defensible by situating training, ethics, and human-robot integration into the technological development cycle. As global efforts to create a human expedition on the Moon and Mars become prominent, these recommendations provide a pragmatic path for quality, policy, and practice routing research towards safe, resilient, and scientifically important off-world habitats.

Future research directions

Future research should pursue a converging program that treats extraterrestrial construction, human-robot collaboration (HRC), and workforce development as mutually dependent pillars rather than parallel tracks. This system view—consistent with Artemis, Moon-to-Mars, and ESA’s Moon Village concepts (Clinton Jr, 2025; NASA, 2021; Athanasopoulos, 2019; Wörner, 2016)—prioritizes joint technical–human–ethical progress. Specifically, the research goals include: (1) establishing trust-calibrated HRC frameworks (Lee and See, 2004; Campagna and Rehm, 2025); (2) building latency-aware operations concepts (Chappell et al., 2024); (3) quantifying regolith and environment-driven risk (Werkheiser et al., 2022; Freeman, 2024); and (4) embedding training, ethics, and safety into the technology lifecycle (Jeelani et al., 2017; Dodoo et al., 2025). Research designs should emphasize traceable metrics, open benchmarks, and interoperable standards so that results can transfer across agencies, nations, and industry partners. These research goals and expected outcomes are intentionally foundational, laying the groundwork for each phase and staying tightly aligned with the converging roadmap.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AJ: Writing – original draft. CG-B: Writing – review and editing. YQ: Writing – review and editing. AW: Writing – review and editing. YZ: Writing – review and editing. JJ: Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The seed funding for this research project is provided by the 2024 Louisiana State University Provost’s Fund for Innovation in Research and the 2023 PFIR Phase III for LSU’s GANGOTRI Mars mission conceptualization.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants of the 6 June 2025, transdisciplinary workshop for their valuable insights and contributions, as well as Louisiana State University for hosting the event.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. ChatGPT was used for editing and grammar check.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Athanasopoulos, H. K. (2019). The moon village and space 4.0: the ‘open concept’as a new way of doing space? Space Policy 49, 101323. doi:10.1016/j.spacepol.2019.05.001

Banijamali, K., Giwa, I., Fiske, M., and Kazemian, A. (2025). Planetary robotic construction on the moon and Mars using waterless sulfur-regolith printing materials. ASCE Comput. Civ. Eng. doi:10.2139/ssrn.5207409

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3 (2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Campagna, G., and Rehm, M. (2025). A systematic review of trust assessments in human–robot interaction. ACM Trans. Human-Robot Interact. 14 (2), 1–35. doi:10.1145/3706123

Cesaretti, G., Dini, E., De Kestelier, X., Colla, V., and Pambaguian, L. (2014). Building components for an outpost on the lunar soil by means of a novel 3D printing technology. Acta Astronaut. 93, 430–450. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2013.07.034

Chappell, M. B., Chai, P. R. P., and Rucker, M. A. (2024). Mars communications disruption and delay. Available online at: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20230012950.

China National Space Administration (CNSA) Roscosmos State Corporation for Space Activities (2021). International lunar research station (ILRS) guide for partnership (V1.0). United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs. Beijing, China: CNSA HQ. Available online at: https://www.unoosa.org/documents/pdf/copuos/2021/AM_3._China_ILRS_Guide_for_Partnership_V1.0Presented_by_Ms.Hui_JIANG.pdf.

Clinton Jr, R. G. (2025). “Space manufacturing and extraterrestrial construction: how did we get here? Where are we? Where should we be going? The challenge: establish the foundation for mission readiness,” in DARPA NOM4D phase 3 kick-off meeting. Available online at: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20250000801/downloads/V3_ISM_ETCONSTR_CLINTON_FINAL%20DARPA_NOM4D_P3_KO.pdf.

De la Torre, G. G., Groemer, G., Diaz-Artiles, A., Pattyn, N., Van Cutsem, J., Musilova, M., et al. (2024). Space analogs and behavioral health performance research: review and recommendations checklist from ESA topical team. npj Microgravity 10, Article 98. doi:10.1038/s41526-024-00437-w

Dodoo, J. E., Al-Samarraie, H., Alzahrani, A. I., and Tang, T. (2025). XR and workers’ safety in high-risk industries: a comprehensive review. Saf. Sci. 185, 106804. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2025.106804

Freeman, R. H. (2024). “Lunar operations: on the standardization of lunar dust mitigation technical capabilities and practices,” in AIAA SCITECH 2024 forum, 1554. doi:10.2514/6.2024-1554

Hohmann, E., Beaufils, P., Beiderbeck, D., Chahla, J., Geeslin, A., Hasan, S., et al. (2025). Guidelines for designing and conducting Delphi consensus studies: an expert consensus Delphi study. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 41, 4208–4224.e10. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2025.03.038

Indian Space Research Organisation (2023). Chandrayaan-3 mission overview. Available online at: https://www.isro.gov.in/Chandrayaan3.html.

Jafari, A., Valentin, V., and Bogus, S. (2019). Identification of social sustainability criteria in building energy retrofit projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 145 (2), 04018136. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0001610

Jafari, A., Zhu, Y., Karunatillake, S., Qian, J., Jeong, S., Kazemian, A., et al. (2024). “Envisioning extraterrestrial construction and the future construction workforce: a collective perspective,” in 41st international symposium on automation and robotics in construction (ISARC 2024). Lille. Available online at: https://www.iaarc.org/publications/fulltext/071_ISARC_2024_Paper_248.pdf.

Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (2024). Conclusion of lunar activities of the smart lander for investigating moon (SLIM). Available online at: https://global.jaxa.jp/press/2024/08/20240826-1_e.html.

Jeelani, I., Han, K., and Albert, A. (2017). “Development of immersive personalized training environment for construction workers,” in Computing in civil engineering 2017: Sensing, simulation, and visualization. Editors K. Y. Lin, N. ElGohary, and P. Tang (American Society of Civil Engineers), 407–415. doi:10.1061/9780784480830.050

Khoshnevis, B., Yuan, X., Zahiri, B., Zhang, J., and Xia, B. (2016). Construction by contour crafting using sulfur concrete with planetary applications. Rapid Prototyp. J. 22 (5), 848–856. doi:10.1108/RPJ-11-2015-0165

Kminek, G., Hedman, N., Ammannito, E., Deshevaya, E., Doran, P., Grasset, O., et al. (2020). COSPAR policy on planetary protection. Space Res. Today 208, 10–22. doi:10.1016/j.srt.2020.07.009

Kminek, G., Benardini, J. N., Brenker, F. E., Brooks, T., Burton, A. S., Dhaniyala, S., et al. (2022). COSPAR sample safety assessment framework (SSAF). Astrobiology 22 (S1), S186–S216. doi:10.1089/ast.2022.0017

Korea Aerospace Research Institute (n.d.). Danuri (KPLO). Available online at: https://kari.re.kr/eng/contents/194.

Lee, J. D., and See, K. A. (2004). Trust in automation: designing for appropriate reliance. Hum. Factors 46 (1), 50–80. doi:10.1518/hfes.46.1.50_30392

Lee, R., Younes, B., Pletta, A., Harrington, J., Wong, R. Q., and Whittaker, W. R. (2023). CraterGrader: autonomous robotic terrain manipulation for lunar site preparation and earthmoving. arXiv. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2311.01697

H. A. Linstone, and M. Turoff (1975). The Delphi method: techniques and applications (Addison-Wesley).

Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Centre (n.d.). Rashid rover — emirates lunar mission. Available online at: https://www.mbrsc.ae/rashid-rover/.

NASA Mars Climate Orbiter Mishap Investigation Board (1999). Phase I report: mars climate orbiter mishap investigation board. Pasadena, CA: NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (2019). Beresheet impact site spotted. Available online at: https://www.nasa.gov/missions/beresheet-impact-site-spotted/.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration, NASA (2021). NASA’s plan for sustained lunar exploration and development. Washington, DC: NASA HQ. Available online at: https://www.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/a_sustained_lunar_presence_nspc_report4220final.pdf.

Netti, V. (2025). Planetary construction with ISRU on moon and Mars: scalability and automation of the construction processes. Available online at: https://tesidottorato.depositolegale.it/handle/20.500.14242/193075.

Netti, V., and Bisharat, T. (2023). “A review of additive manufacturing technologies for planetary construction,” in Earth and space 2022: space exploration, utilization, engineering, and construction in extreme environments (American Society of Civil Engineers), 893–903. doi:10.1061/9780784484470.075

Ørngreen, R., and Levinsen, K. T. (2017). Workshops as a research methodology. Electron. J. E-Learning 15 (1), 70–81. Available online at: https://vbn.aau.dk/en/publications/workshops-as-a-research-methodology/.

Pagel, J. I., and Choukèr, A. (2016). Effects of isolation and confinement on humans—implications for manned space explorations. J. Appl. Physiology 120 (12), 1449–1457. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00928.2015

Sacksteder, K. R., and Sanders, G. B. (2007). In-situ resource utilization for lunar and Mars exploration. 45th AIAA Aerosp. Sci. Meet. doi:10.2514/6.2007-345

Sheridan, T. B. (2016). Human–robot interaction: status and challenges. Hum. Factors 58 (4), 525–532. doi:10.1177/0018720816644364

Slabic, A., Gruener, J. E., Kovtun, R. N., Rickman, D. L., Sibille, L., Oravec, H. A., et al. (2024). Lunar regolith simulant user's guide: revision A. Washington, DC: NASA HQ. Available online at: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20240011783/downloads/Lunar_Regolith_Simulant_Users_Guide_Rev_A_28OCT.pdf.

Song, Y.-J., Bang, J., Bae, J., and Hong, S. (2023). Lunar orbit acquisition of the Korea pathfinder lunar orbiter: design reference vs actual flight results. Acta Astronaut. 213, 336–343. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2023.09.021

Soni, N., Singh, P. K., Mallick, S., Pandey, Y., Tiwari, S., Mishra, A., et al. (2024). Advancing sustainable energy: exploring new frontiers and opportunities in the green transition. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 8 (10), 2400160. doi:10.1002/adsu.202400160

Stitt-Gohdes, W. L., and Crews, T. B. (2004). The Delphi technique: a research strategy for career and technical education. J. Career Tech. Educ. 20 (2), 55–67. doi:10.21061/jcte.v20i2.636

Thangavelautham, J., Law, K., Fu, T., Abu El Samid, N., Smith, A. D. S., and D’Eleuterio, G. M. T. (2017). Autonomous multirobot excavation for lunar applications. arXiv Preprint. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1701.01657

Tute, R. M., and Goulas, A. (2024). Mechanical behaviour of sulphur-based Martian regolith concrete processed under CO2-rich conditions. Icarus 417, 116134. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2024.116134

Wang, D., and Huang, X. (2025). Transforming education through artificial intelligence and immersive technologies: enhancing learning experiences. Interact. Learn. Environ. 33, 4546–4565. doi:10.1080/10494820.2025.2465451

Wen, S., Middleton, M., Ping, S., Chawla, N. N., Wu, G., Feest, B. S., et al. (2025). AdaptiveCoPilot: design and testing of a NeuroAdaptive LLM cockpit guidance system in both novice and expert pilots. arXiv. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2501.04156

Werkheiser, N., Desai, P., and Galica, C. A. (2022). “NASA lunar surface innovation initiative: ensuring a cohesive, executable strategy for technology,” in The international astronautical congress. Available online at: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20220013228.

Wörner, J. (2016). “Moon village,” in ESA TV exchange. Vienna, Austria: Vienna University of Technology.

Xiao, X., Zhu, H., Liang, J., Tong, J., and Wang, H. (2025). A comprehensive review of human error in risk-informed decision making: integrating human reliability assessment, artificial intelligence, and human performance models. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2507.01017. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2507.01017

Xu, L., Li, H., Pei, Z., Zou, Y., and Wang, C. (2022). A brief introduction to the international lunar research station program and the interstellar express mission. Chin. J. Space Sci. 42 (4), 511–513. doi:10.11728/cjss2022.04.yg28

Keywords: extraterrestrial construction, human-robot collaboration, workforce training, immersive simulation, space habitats

Citation: Jafari A, Gary-Bicas CE, Qian Y, Webb AM, Zhu Y and Jamerson J (2025) Building beyond earth: a roadmap for human-robot collaboration and workforce development in extraterrestrial construction. Front. Space Technol. 6:1701442. doi: 10.3389/frspt.2025.1701442

Received: 10 October 2025; Accepted: 24 November 2025;

Published: 10 December 2025.

Edited by:

Xiaofeng Wu, The University of Sydney, AustraliaReviewed by:

Angel Flores Abad, The University of Texas at El Paso, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Jafari, Gary-Bicas, Qian, Webb, Zhu and Jamerson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Amirhosein Jafari, YWphZmFyaTFAbHN1LmVkdQ==

Amirhosein Jafari

Amirhosein Jafari Carlos E. Gary-Bicas

Carlos E. Gary-Bicas Yufeng Qian

Yufeng Qian Andrew M. Webb

Andrew M. Webb Yimin Zhu

Yimin Zhu Jason Jamerson5

Jason Jamerson5