- 1Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States

- 2Department of Internal Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States

- 3Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States

The majority (55%) of the world’s population lives in urban environments. Of relevance to global mental health, the rapid growth in urban populations around the world and the attendant risks coincide with the presence of the largest population of adolescents the global community has seen to date. Recent reviews on the effects of the urban environment on mental health report a greater risk of depression, anxiety, and some psychotic disorders among urban dwellers. Increased risk for mental disorders is associated with concentrated poverty, low social capital, social segregation, and other social and environmental adversities that occur more frequently in cities. To address these problems, urban adolescent mental health requires attention from decision makers as well as advocates who seek to establish sustainable cities. We examine opportunities to increase the prominence of urban adolescent mental health on the global health and development agenda using Shiffman and Smith’s framework for policy priorities, and we explore approaches to increasing its relevance for urban health and development policy communities. We conclude with suggestions for expanding the community of actors who guide the field and bridging the fields of mental health and urban development to meet urban adolescent mental health needs.

Introduction

The United Nations (UN) New Urban Agenda (NUA) was adopted in Quito, Ecuador in 2016 at the UN Conference on Housing and Sustainable Development (Habitat III) (1). The Agenda’s writers envisioned a future for cities in which all city dwellers “without discrimination of any kind are able to inhabit and produce just, safe, healthy, accessible, affordable, resilient and sustainable cities and human settlements to foster prosperity and quality of life for all (1).” The document embraces the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and other relevant frameworks for development, climate change, and poverty reduction (2), and it is timely. As of 2018, 55% of the global population lived in cities, and 1 in 8 urban residents lived in a city with more than 10 million people (3). Cities offer greater opportunities for wealth, employment, social freedoms, and education but inequality is increasingly one of the hallmarks of large cities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries (4). Rapidly urbanizing cities in lower income countries struggle with insufficient urban services, from water and sanitation to healthcare and housing, but the sufficiency of these services can vary considerably within cities at any income level (4). When infrastructural resources are scarce, cities accumulate additional vulnerabilities, e.g., to climate change, to natural disasters, and the effects are most devastating for the poorest residents. In these conditions, poor mental health is one of many negative outcomes, but one of the most disabling for young people.

An estimated 13%–15% of adolescents (10–19 year olds) in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) live with a mental disorder (5), and depression and anxiety are among the 10 leading causes of disability for children and adolescents globally (6). In the current context of global urbanization, history’s largest population of adolescents is transitioning into adulthood (7, 8). Around 1.2 billion adolescents between the ages of 10 and 19 constitute 16% of the world’s population (8). The majority of these young people live in Asia, and though less numerous in total numbers, adolescents make up 23% of the Africa region’s population (8). These two continents account for 90% of expected urban growth of the coming decades (3). Adolescents who live in cities are exposed to the risks and benefits of urban life during this dynamic and sensitive period of social and neurodevelopment and to the consequent mental health outcomes.

Generally, urbanicity increases risk for psychosis (9–11), anxiety disorders (12), and depression (12). Social isolation, neighborhood poverty, and discrimination also contribute to poor mental health (13). Despite the morbidity associated with mental disorders, neither treatment nor mental health promotion for adolescents has achieved global public health priority. Financing to address these services is distressingly low. From 2007 to 2015, around $190 million of Development Assistance in Child and Adolescent mental health was invested, which amounts to about 0.01% of development assistance for health (14). Fifteen years ago, Sclar et al. (2005) pointed to the growing population of urban adolescents and the dearth of research regarding their health needs (15). As the global community seeks to achieve targets for sustainable development that could address these needs, the time is right for articulating how diverse constituencies can meet shared goals, such as for adolescent mental health and urban sustainability (16, 17).

Urban sustainability, as defined by urban planners and envisioned by the NUA, should enable cities to better meet the mental health needs of young people. It’s goal is to “promote and facilitate the long-term well-being of people and the planet through efficient use and management of resources while improving a city’s livability, through social amenities, economic opportunity and health, and enabling the city to integrate well with local, regional and global ecosystems (18).” The guiding principles of the New Urban Agenda support this goal (Box 1). The World Health Organization (WHO) argues that healthy citizens are the most important asset of any city, and that “a health lens” should inform the NUA (19). We propose that full implementation of the NUA could, if properly directed, create environments that yield improved mental health for urban adolescents globally, primarily by reducing upstream or “distal” risk factors for mental disorders (16). Consequently, as decision-makers achieve their agreed upon priorities (e.g., meeting targets for the SDGs and NUA) they could also facilitate urban adolescent mental health and wellbeing.

Box 1. Principles of the New Urban Agenda (1).

1. Leave no one behind, by ending poverty in all its forms and dimensions, including the eradication of extreme poverty, by ensuring equal rights and opportunities, socioeconomic and cultural diversity, and integration in the urban space, by enhancing liveability, education, food security and nutrition, health and well-being, including by ending the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria, by promoting safety and eliminating discrimination and all forms of violence, by ensuring public participation—providing safe and equal access for all, and by providing equal access for all to physical and social infrastructure and basic services, as well as adequate and affordable housing;

2. Ensure sustainable and inclusive urban economies by leveraging the agglomeration benefits of well-planned urbanization, including high productivity, competitiveness and innovation, by promoting full and productive employment and decent work for all, by ensuring the creation of decent jobs and equal access for all to economic and productive resources and opportunities and by preventing land speculation, promoting secure land tenure and managing urban shrinking, where appropriate;

3. Ensure environmental sustainability by promoting clean energy and sustainable use of land and resources in urban development, by protecting ecosystems and biodiversity, including adopting healthy lifestyles in harmony with nature, by promoting sustainable consumption and production patterns, by building urban resilience, by reducing disaster risks and by mitigating and adapting to climate change.

The implementation of a comprehensive agenda requires prioritization and negotiation around which aspects will be fully implemented and resourced. Raising the profile of activities relevant to adolescent mental health may require specific strategies. In this Perspective, we apply Shiffman and Smith’s criteria for the determinants of political priority to urban adolescent mental health in the global context, in order to identify opportunities for expanding cross-sector engagement to support and prioritize adolescent mental health (20). Briefly, Shiffman and Smith assert that global health initiatives are more likely to receive political priority when four foundational factors support each other: (1) coherent internal framing of ideas as well as external framing of the ideas that resonate with leaders; (2) issue characteristics that are amenable to credible indicators, objective measurement of severity, and effective interventions; (3) favorable political contexts that allow actors to influence decision makers or governance structures that enable collective action; and (4) strong and unified actor power (20).

Exploring Factors for Collective Action

Ideas: Summarizing the Internal Frame

Shiffman and Smith (2007) identify the framing of ideas about an issue as a key component of successful collective action, noting that “any issue can be framed in several ways….Some frames resonate more than others, and different frames appeal to different audiences (20).” Coherent internal framing among key actors in a given field enables the clear communication of priorities of the field to external stakeholders and facilitates unified mobilization of the field. A long history of research on adolescent development and mental health brought together in recent impactful publications demonstrates a coherent internal framing with validity for high-, middle-, and low-income settings (7, 21). Key elements of this consistent internal framing are that (1) adolescence is a dynamic period of neurodevelopment during which young people acquire higher-level cognitive, emotional, and social skills for functioning and expanded interactions beyond the home (7, 22, 23); (2) adolescence provides a meaningful opportunity to remediate insults from early life while setting healthy trajectories for adult life, and, consequently, for the next generation (21); and (3) central to adolescents’ health and wellbeing are their interactions with the physical environment, the social context, and the people in these environments (23).

Ideas: Options for External Framing

The “external frame,” is the way an issue is portrayed to policymakers and the public (20). We present four ways of framing adolescent mental health that intersect with the principles of the New Urban Agenda: a social justice frame, an economic frame, an urban design and intersectoral governance frame, and a security frame.

Adolescents are dying from preventable causes associated with their mental health, and they have a right to mental health care. Suicide is the second leading killer of older adolescents (24), and the prevalence of self-harm and suicidal behaviors is as high as 15%–31% and 3%–4.7%, respectively, among adolescents in LMICs (25). Self-harm elevates risk of future suicide 30–100 fold (26, 27). The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Declaration of the Rights of the Child, which include the rights to health, education, and freedom from neglect, codify adolescents’ rights to treatment of mental illness and promotion of mental health (28, 29). Using a human rights lens broadly appeals to the global community (30), which may be important for adolescent mental health advocates, and could serve a unifying purpose as they seek to influence health, education, and urban planning sectors. As Shiffman and Smith show in their case study of the successful elevation of maternal health on the global agenda, a social justice frame added urgency to the issue and spoke to the public, in addition to content experts, which helped build support (30).

“Investments in adolescent health and wellbeing [including mental health] bring a triple dividend of benefits now, into future adult life, and for the next generation of children” (7), and investments in urban neighborhoods are an investment in adolescents. Indirect investments through poverty reduction strategies that increase access to quality education, food security, and mental health services should improve adolescent mental health while also supporting the principles of urban sustainability. Concentrated poverty in urban neighborhoods contributes to poor mental health outcomes (e.g., hopelessness, anxiety, and depression) (31, 32). Direct investments in urban mental health services compound benefits as treatment of mental illness has been shown to improve economic outcomes (33). Highlighting the economic costs of poor mental health or benefits of promoting mental health and averting or treating mental illness may speak to policymakers’ needs to seek significant returns on investment and reduce spending over the long-term (34).

Data from South Africa (35), Kenya (36), as well as India, Nigeria, South Africa, and China (37) show that even as urban communities await the implementation of successful poverty reduction strategies or investments in health and education, other factors can support adolescent mental health. Intersectoral urban polices and thoughtful urban design create additional paths to adolescent mental health. Social protection policies that reduce maltreatment and improve parental caregiving quality, and community structures that permit quality peer relationships can support resilience for children with multiple stressors (35). Cultivating friendly home environments, ensuring parental presence in the home, and supporting parental monitoring can reduce behavioral risk even in the most distressed settings, such as informal settlements (36). Community design that enhances neighborhood social support and connection could promote adolescent mental health in some African and Asian contexts (37). Locally accessible economic opportunities that provide resources to adult female carers could be of particular benefit to adolescent girls (37).

A security frame may have less broad appeal, but particular salience for leaders in urban environments racked by youth violence or terrorism. Violence can be both a cause and consequence of poor mental health. Social cohesion, low social control, high neighborhood disorder, and violent victimization or fears of it are associated with adverse adolescent mental health outcomes in high-income countries (11, 31, 32, 38). Growing up in areas with high violence and low social support has been associated with use of negative psychological coping mechanisms, such as acting out or aggressive behavior (39, 40). In communities affected by violence and poverty, considerable international resources are being devoted to the prevention of radicalization (41, 42) and many of these efforts target adolescents (43). A recent report by the UN Development Program used qualitative interviews with people in Africa who were recruited to violent extremist groups to better understand what drew them to those groups (43). Respondents noted that unhappiness in childhood and poor parental support contributed to their participation in extremist groups, and the UNDP called for programming to support healthy parenting, outreach to high risk youth, and initiatives to promote staying in school (43). Anti-radicalization programs may bring unprecedented resources, but come with the ethical complexity of working within defense budgets. Youth mental health advocates should avoid the stigmatizing and dehumanizing framing of adolescents as potential threats to security, but may be valuable voices in efforts to prevent violence and radicalization by strengthening family and educational systems.

Issue Characteristics

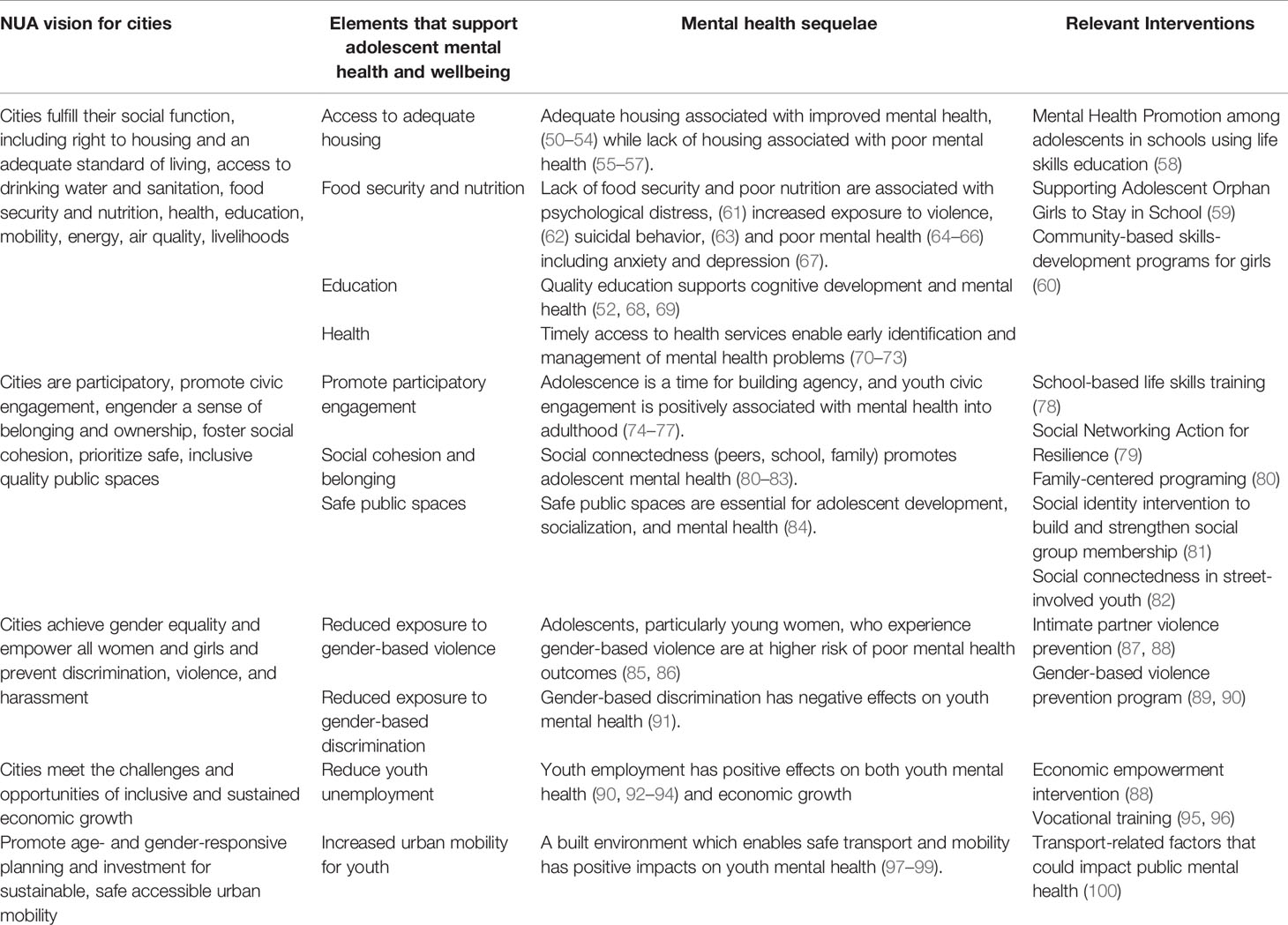

The perceived severity of an issue, the availability of credible indicators, and the perceived effectiveness of solutions also determine its political priority (20). Challenges for the perceived severity of child and adolescent mental health problems in LMICs include a small, albeit growing, evidence base, limited awareness of youth mental health issues, and scarce human resources to address these issues (44). In the absence of specialists, clarity of identification and diagnosis create additional challenges to ascertaining illness. However, data do exist to demonstrate the high prevalence of self-injurious and suicidal behaviors among adolescents in LMICs—markers of severity. The Global Burden of Disease studies play a valuable role in providing credible indicators for mental disorders by estimating the prevalence and the disease burden of adolescent mental disorders in HICs and LMICs (6, 45–47). UNICEF’s initiative, Measurement of Mental Health among Adolescents at the Population Level (MMAP) seeks to validate instruments in diverse cultural contexts (48). The Lancet Commission on adolescent health and wellbeing now tracks 12 indicators for progress in adolescent health and wellbeing (7, 49). These capture disability adjusted life years for communicable, maternal, and nutritional disorders; injury and violence; and non-communicable diseases, including mental and substance use disorders (7, 49). They also track health risks, such as smoking, binge drinking and obesity as well as social determinants of health (i.e., educational attainment, birth rates, marriage age, the proportion of older adolescents and youth who are not in employment, education or training (NEET) (49). Such indicators can also serve as milestones for achieving urban sustainability. Importantly, feasible, effective interventions for implementation in urban settings can address risks for poor mental health (Table 1).

Table 1 The New Urban Agenda and elements that support adolescent mental health: mental health sequelae and interventions.

Actor Power

The ideas, evidence and framing of urban adolescent mental health needs can only be meaningful when conveyed and sustained by an influential group of actors and institutions—the policy community (101). For global mental health and adolescent health, this community continues to grow in size and diversity. These actors have helped to create and support a set of rules, norms and strategies within and across organizations that help promote portrayals (or framing) of adolescent health and wellbeing (101, 102). The launch of WHO’s Global Accelerated Action for the Health of Adolescents (AA-HA)!, the Global Strategy for Women’s Children’s and Adolescents’ Health, and the Lancet Commission on adolescent health and wellbeing (7), and UNICEF’s and other multilateral interests in the intersections of gender, mental health, and adolescence (103), reflect the increasing prominence of adolescent health on the global health agenda and the action of the policy community. Guiding institutions in global mental health (e.g., the World Health Organization, the Lancet Commission on Global Mental Health and Sustainable Development) also highlight adolescent mental health as priority (17).

Importantly, additional actors have joined the policy community. The voices of people with lived experience of mental health conditions are present. Youth advocates have also joined the community (https://globalmentalhealthcommission.org/youth-campaign/). There remain critical missing voices. A majority of the published research we identified on urban adolescent mental health focused on young people in distressed communities in HICs and LMICs. These youth represent a resource for engagement in advocacy for urban mental health. The New Urban Agenda identifies youth engagement and capacity development as explicit goals (1), and there is preliminary evidence that involvement in collective action can promote youth development among adolescents in some contexts (74). Global platforms like citiesRISE, which value intersectoral collaboration along with youth mobilization and leadership for progress in adolescent mental health, could help to bridge these policy communities (104).

In order to bridge relevant communities, the global mental health community and child and adolescent advocates need to learn the language of urban sustainability and generate knowledge relevant to both sectors. Universities, which often support and foster interdisciplinary collaborations, may be ideal settings for engaging young people and bridging urban design, mental health, climate, public health, and other relevant constituencies. New publications and recent textbooks (105) are also establishing this field as a discipline (https://www.urbandesignmentalhealth.com/), which will help to strengthen the evidence generated from new collaborative efforts.

Policy Contexts

Shiffman and Smith argue that one route to political priority in global health is to take advantage of policy windows, i.e., political moments that present opportunities for advocates to influence decision makers (20). The NUA and the SDG’s provide such opportunities for advocates of urban adolescent mental health. Many non-health SDGs are associated with distal determinants of poor mental health and achieving certain SDG targets could provide particular benefit for urban adolescents, given the relationships among environment, social experience and mental health outcomes (16). Together, these documents provide a platform for integrating adolescent mental health within urban development.

While international agreements are vital, domestic policy windows provide opportunities for small steps toward integration of adolescent mental health into the broader health and development agenda. Zimbabwe’s Ministry of Health and Child Care recently formed a Mental Health Research Task Force to set national research priorities and better coordinate and publicize research (106). While the Task Force includes a diverse set of researchers and practitioners, including some with an interest in child and adolescent mental health, it includes no one who focuses on urban planning or city development. Especially at the outset of the taskforce, there are opportunities to advocate for the inclusion of new perspectives. Finding opportunities to incorporate voices of mental health specialists into urban planning conversations and urban planners into mental health conversations may help advance adolescent urban mental health in local or national policies and priorities.

In addition to policy windows, Shiffman and Smith draw attention to global governance structures (norms and institutions), which can both facilitate and impede collective action. Responsibility for adolescent mental health in an urban environment spans numerous areas of government, including ministries of health, urban planning, and criminal justice institutions. This fragmentation of responsibility can lead to “buck passing”, in which every institution believes that the problem is the responsibility of another institution, and thus no institution takes definitive action (30, 107). Advocates face the challenge of uniting these institutions around common commitments and projects to promote adolescent wellbeing. Conversely, the benefit of having multiple institutions involved is that there is potential for pooling of resources toward a common goal (108). While it does not focus on adolescents, one model of successful cross-sectoral collaboration between health and urban planning is the Research Initiative for Cities and Health (RICHE) network, an interdisciplinary group based out of University of Cape Town that has set priorities for and works to promote urban health research in Africa (109, 110).

How and whether decision makers seize policy windows to promote action for mental health is also influenced by the cultural context. In settings where tremendous social stigma is attached to mental disorders and where structural stigma relegates mental health issues to low priority, identifying and vocally advocating for those portions of other agendas (like the NUA or SDG 11) that can enhance mental health outcomes becomes even more important.

Other Considerations

We have outlined how Shiffman and Smith’s criteria–the framing of ideas, engaging an enlarged policy community, using evidence to shape the messages, and taking advantage of the current political context, i.e., countries’ desires to achieve the SDGs—can contribute to prioritization of actions that simultaneously support adolescent mental health and action for urban sustainability (20). Shiffman notes that these factors lack a theoretical basis, but the importance of ideas and how they are portrayed, as well as the strength of the institutions the policy community forms, become more salient factors of influence through some theoretical lenses (101). Perspectives of mental health advocates in an LMIC setting support the importance of coordinating a shared message among many stakeholders, active engagement with decision makers, and effectively communicating messages (111).

Conclusions

Chisholm and colleagues showed that investment in mental health in LMICs yields a significant return (112). Investment in adolescent mental health is particularly advantageous. Adolescence is a critical stage of development, and the contexts in which adolescents live help shape their ability to contribute fully to society socially, economically, and intellectually. Importantly, the actions to achieve these ends can be integrated with other efforts. Just as integrating mental health into broader health care efforts is critical for achieving good outcomes for most health conditions, (113, 114), what we know about urban adolescent mental health can inform implementation of the New Urban Agenda. In order for this to occur, relevant decision-makers must recognize the value and importance of actions that support adolescents in urban contexts. Progress toward translating strategies to action that successfully influences decision makers will depend on meaningful alliances across sectors and disciplines, careful understanding of political leaders’ concerns in local contexts (101), and the ability to thoughtfully and nimbly respond to these.

Author Contributions

PC developed the concept of the manuscript. LM, TC, HJ, and PC reviewed relevant literature, and wrote sections of the manuscript. PC and HJ wrote the final draft. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

PC was supported in part by a contract with the Global Development Incubator for research coordination activities with citiesRISE.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

3. United Nations. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision, key facts. New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2018).

4. UN Habitat. Urbanization and Development: Emerging Futures. In: World Cities Report 2016. Nairobi, Kenya: UN-Habitat (2016).

5. IHME. GBD Results Tool, Global Health Data Exchange, September 1, 2019, Global Burden of Disease 2017 data for 10-19 year olds, low- and middle-income countries, mental and substance use disorders, prevalence (%). Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) (2017). Accessed Nov 13, 2019.

6. Reiner RC Jr., Olsen HE, Ikeda CT, Echko MM, Ballestreros KE, Manguerra H, et al. Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors in Child and Adolescent Health, 1990 to 2017: Findings From the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors 2017 Study. JAMA Pediatr (2019) 173(6):e190337. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0337

7. Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, Ross DA, Afifi R, Allen NB, et al. Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet (2016) 387(10036):2423–78 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1.

9. Vassos E, Pedersen CB, Murray RM, Collier DA, Lewis CM. Meta-analysis of the association of urbanicity with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull (2012) 38(6):1118–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1

10. Pedersen CB, Mortensen PB. Evidence of a dose-response relationship between urbanicity during upbringing and schizophrenia risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry (2001) 58(11):1039–46. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs096

11. Newbury J, Arseneault L, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Odgers CL, Fisher HL. Why Are Children in Urban Neighborhoods at Increased Risk for Psychotic Symptoms? Findings From a UK Longitudinal Cohort Study. Schizophr Bull (2016) 42(6):1372–83. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs096

12. Peen J, Schoevers RA, Beekman AT, Dekker J. The current status of urban-rural differences in psychiatric disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand (2010) 121(2):84–93. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.11.1039

13. Gruebner O, Rapp MA, Adli M, Kluge U, Galea S, Heinz A. Cities and Mental Health. DtschArzteblInt (2017) 114(8):121–7. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw052

14. Lu C, Li Z, Patel V. Global child and adolescent mental health: The orphan of development assistance for health. PloS Med (2018) 15(3):e1002524. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01438.x

15. Sclar ED, Garau P, Carolini G. The 21st century health challenge of slums and cities. Lancet (2005) 365(9462):901–3. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0121

16. Lund C, Brooke-Sumner C, Baingana F, Baron EC, Breuer E, Chandra P, et al. Social determinants of mental disorders and the Sustainable Development Goals: a systematic review of reviews. Lancet Psychiatry (2018) 5(4):357–69. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002524

17. Patel V, Shekhar SS, Lund C, Thornicroft G, Baingana F, Bolton P, et al. The Lancet Commission on Global Mental Health & Sustainable Development. Lancet (2018). 392(10157):1553–98. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71049-7

18. Newman P. Sustainability and cities: Extending the metabolism model. Landscape UrbanPlann (1999) 44:219–26. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30060-9

19. WHO. Health as the pulse of the New Urban Agenda: United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development, Quito. Geneva: World Health Organization (2016). doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31612-X

20. Shiffman J, Smith S. Generation of political priority for global health initiatives: a framework and case study of maternal mortality. Lancet (2007) 370(9595):1370–9. doi: 10.1016/S0169-2046(99)00009-2

21. Bundy DAP, De Silva N, Horton S, Pattion G, Schultz L, Jamison DT, et al. Child and adolescent health and development: realizing neglected potential. In: Bundy DAP, et al, editors. Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition, Child and Adolescent Health and Development. Washingon, DC: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank (2017). p. 1–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61579-7

22. Bundy DAP, de Silva N, Horton S, Patton GC, Schultz L, Jamison DT. Investment in child and adolescent health and development: key messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd Edition. Lancet (2018) 391(10121):687–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61579-7

23. Call KT, Riedel AA, Hein K, McLoyd V, Petersen A, Kipke M. Adolescent health and well-being in the twenty-first century: a global perspective. J Res Adolescence (2002) 12(1):69–98. doi: 10.1596/978-1-4648-0423-6_ch1

24. WHO. Suicide in the world: Global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization (2019). doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.00025

25. Aggarwal S, Patton G, Reavley N, Sreenivasan SA, Berk M. Youth self-harm in low- and middle-income countries: Systematic review of the risk and protective factors. Int J Soc Psychiatry (2017) 63(4):359–75. doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.00025

26. Cooper J, Kapur N, Webb R, Lawlor M, Guthrie E, Mackway-Jones K, et al. Suicide after deliberate self-harm: a 4-year cohort study. Am J Psychiatry (2005) 162:297–303. doi: 10.1177/0020764017700175

27. Hawton K, Bergen H, Cooper J, Turnbull P, Waters K, Ness J, et al. Suicide following selfharm: findings from the multicentre study of self-harm in England, 2000–2012. J Affect Disord (2015) 175:147–51. doi: 10.1177/0020764017700175

28. United Nations General Assembly. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Paris: United Nations (1948). doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.297

29. United Nations General Assembly. (1959). Declaration of the Rights of the Child. United Nations. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.062

30. Smith SL, Shiffman J. Setting the global health agenda: the influence of advocates and ideas on political priority for maternal and newborn survival. Soc Sci Med (2016) 166:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.08.013

31. Hurd NM, Stoddard SA, Zimmerman MA. Neighborhoods, social support, and african american adolescents’ mental health outcomes: a multilevel path analysis. Child Dev (2013) 84(3):858–74. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.08.013

32. Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science (1997) 277(5328):918–24. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.08.013

33. Lund C, De Silva M, Plagerson S, Cooper S, Chisholm D, Das J, et al. Poverty and mental disorders: breaking the cycle in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet (2011) 378:1502–14. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12018

34. Jack H, Stein A, Newton CR, Hofman KJ. Expanding access to mental health care: a missing ingredient. Lancet GlobHealth (2014) 2(4):e183–4. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918

35. Collishaw S, Gardner F, Lawrence Aber J, Cluver L. Predictors of Mental Health Resilience in Children who Have Been Parentally Bereaved by AIDS in Urban South Africa. J Abnorm Child Psychol (2016) 44(4):719–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60754-X

36. Ndugwa RP, Kabiru CW, Cleland J, Beguy D, Egondi T, Zulu EM, et al. Adolescent problem behavior in Nairobi’s informal settlements: applying problem behavior theory in sub-Saharan Africa. J UrbanHealth (2011) 88 Suppl 2:S298–317. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70029-4

37. Cheng Y, Li X, Lou C, Sonenstein FL, Kalamar A, Jejeebhoy S, et al. The association between social support and mental health among vulnerable adolescents in five cities: findings from the study of the well-being of adolescents in vulnerable environments. J Adolesc Health (2014) 55(6 Suppl):S31–8. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0068-x

38. Dupere V, Leventhal T, Vitaro F. Neighborhood processes, self-efficacy, and adolescent mental health. J Health Soc Behav (2012) 53(2):183–98. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9462-4

39. Dempsey M. Negative coping as mediator in the relation between violence and outcomes: Inner-city African American youth. Am J Orthopsychiatry (2002) 72(1):102–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.020

40. Richards MH, Larson R, Miller BV, Luo Z, Sims B, Parrella DP, et al. Risky and protective contexts and exposure to violence in urban African American young adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol (2004) 33(1):138–48. doi: 10.1177/0022146512442676

41. Weine S. Building community resilience to violent extremism. Georgetown J Int Affairs (2013) 14:81. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.72.1.102

42. Feddes AR, Mann L, Doosje B. Increasing self-esteem and empathy to prevent violent radicalization: a longitudinal quantitative evaluation of a resilience training focused on adolescents with a dual identity. J Appl Soc Psychol (2015) 45(7):400–11. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_13

43. UNDP. Journey to extremism in Africa: drivers, incentives and the tipping point for recruitment. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme (2017). doi: 10.1111/jasp.12307

44. Patel V, Flisher AJ, Nikapota A, Malhotra S, et al. Promoting child and adolescent mental health in low and middle income countries. J Child Psychol Psychiatry (2008) 49(3):313–34. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12307

45. GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet (2017) 390(10100):1211–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01824.x

46. Vos T, Flaxman A, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet (2012) 380:2163–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01824.x

47. Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter A, Ferrari AK, Erskine HE, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet (2013) S0140-6736(13):61611–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6

48. UNICEF. (2019). Measurement of mental health among adolescents at the population level (MMAP). UNICEF, September 5, 2019.

49. Azzopardi PS, Hearps SJC, Francis KL, Kennedy EC, Mokdad AH, Kassebaum NJ, et al. Progress in adolescent health and wellbeing: tracking 12 headline indicators for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016. Lancet (2019) 393(10176):1101–18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32427-9

50. Crisanti AS, Duran D, Greene RN, Reno J, Luna-Anderson C, Altschul DB. A longitudinal analysis of peer-delivered permanent supportive housing: Impact of housing on mental and overall health in an ethnically diverse population. Psychol Serv (2017) 14(2):141–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32427-9

51. Gewirtz AH. Promoting children’s mental health in family supportive housing: a community-university partnership for formerly homeless children and families. J PrimPrev (2007) 28(3-4):359–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32427-9

52. World Health Organization and Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. Social determinants of mental health. Geneva: World Health Organization (2014). doi: 10.1037/ser0000135

53. Nguyen QC, Rehkopf DH, Schmidt NM, Osypuk TL. Heterogeneous Effects of Housing Vouchers on the Mental Health of US Adolescents. Am J Public Health (2016) 106(4):755–62. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0102-z

54. Schmidt NM, Glymour MM, Osypuk TL. Housing mobility and adolescent mental health: The role of substance use, social networks, and family mental health in the Moving to Opportunity Study. SSM Popul Health (2017) 3:318–25. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.303006

55. Butler AM, Kowalkowski M, Jones HA, Raphael JL. The relationship of reported neighborhood conditions with child mental health. Acad Pediatr (2012) 12(6):523–31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.303006

56. Barnes AJ, Gilbertson J, Chatterjee D. Emotional Health Among Youth Experiencing Family Homelessness. Pediatrics (2018) 141(4):e20171767. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.03.004

57. Blencowe H, Lee AC, Cousens S, Bahalim A, Narwal R, Zhong N, et al. Preterm birth-associated neurodevelopmental impairment estimates at regional and global levels for 2010. Pediatr Res (2013) 74(S1):17–34. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2012.06.005

58. Srikala B, Kishore KK. Empowering adolescents with life skills education in schools - School mental health program: Does it work? Indian J Psychiatry (2010) 52(4):344–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1767

59. Hallfors D, Rusakaniko S, Iritani B, Mapfumo J, Halpern C. Supporting Adolescent Orphan Girls to Stay in School as HIV Risk Prevention: Evidence From a Randomized Controlled Trial in Zimbabwe. Am J Public Health (2011) 101(6):1082–8. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.204

60. Amin S, Ahmed J, Saha J, Hossain I, Haque E. (2016). Delaying child marriage through community-based skills-development programs for girls: results from a randomized controlled study in rural Bangladesh. New York and Dhaka, Bangladesh: Population Council. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.74310

61. Friel S, Berry H, Dinh H, O'Brien L, Walls HL. The impact of drought on the association between food security and mental health in a nationally representative Australian sample. BMC Public Health (2014) 14:1102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300042

62. Chilton MM, Rabinowich JR, Woolf NH. Very low food security in the USA is linked with exposure to violence. Public Health Nutr (2014) 17(1):73–82. doi: 10.31899/pgy9.1009

63. Shayo FK, Lawala PS. Does food insecurity link to suicidal behaviors among in-school adolescents? Findings from the low-income country of sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Psychiatry (2019) 19(1):227. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1102

64. Zahra J, Ford T, Jodrell D. Cross-sectional survey of daily junk food consumption, irregular eating, mental and physical health and parenting style of British secondary school children. Child Care Health Dev (2014) 40(4):481–91. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013000281

65. Whitsett D, Sherman MF, Kotchick BA. Household Food Insecurity in Early Adolescence and Risk of Subsequent Behavior Problems: Does a Connection Persist Over Time? J Pediatr Psychol (2019) 44(4):478–89. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2212-6

66. Shankar P, Chung R, Frank DA. Association of Food Insecurity with Children’s Behavioral, Emotional, and Academic Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J Dev Behav Pediatr (2017) 38(2):135–50. doi: 10.1111/cch.12068

67. Rani D, Singh JK, Acharya D, Paudel R, Lee K, Singh SP. Household Food Insecurity and Mental Health Among Teenage Girls Living in Urban Slums in Varanasi, India: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2018) 15(8):E1585. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsy088

68. Gao Q, Li H, Zou H, Cross W, Bian R, Liu Y. The mental health of children of migrant workers in Beijing: the protective role of public school attendance. Scand J Psychol (2015) 56(4):384–90. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000383

69. Borghans L, Golsteyn BH, Zölitz U. School Quality and the Development of Cognitive Skills between Age Four and Six. PloS One (2015) 10(7):e0129700. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15081585

70. Chuah FLH, Haldane VE, Cervero-Liceras F, Ong SE, Sigfrid LA, Murphy G, et al. Interventions and approaches to integrating HIV and mental health services: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan (2017) 32(suppl_4):iv27–47. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12232

71. Reardon T, Harvey K, Baranowska M, O'Brien D, Smith L, Creswell C. What do parents perceive are the barriers and facilitators to accessing psychological treatment for mental health problems in children and adolescents? A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry (2017) 26(6):623–47. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129700

72. Fawzi MC, Betancourt TS, Marcelin L, Klopner M, Munir K, Muriel AC, et al. Depression and post-traumatic stress disorder among Haitian immigrant students: implications for access to mental health services and educational programming. BMC Public Health (2009) 9:482. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czw169

73. Bains RM, Diallo AF. Mental Health Services in School-Based Health Centers: Systematic Review. J Sch Nurs (2016) 32(1):8–19. doi: 10.1007/s00787-016-0930-6

74. Kirshner B, Ginwright S. Youth organizing as a developmental context for African American and Latino adolescents. Child Dev Perspect (2012) 6(3):288–94. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-482

75. Ballard PJ, Hoyt LT, Pachucki MC. Impacts of Adolescent and Young Adult Civic Engagement on Health and Socioeconomic Status in Adulthood. Child Dev (2019) 90(4):1138–54. doi: 10.1177/1059840515590607

76. Landstedt E, Almquist YB, Eriksson M, Hammarstrom A. Disentangling the directions of associations between structural social capital and mental health: Longitudinal analyses of gender, civic engagement and depressive symptoms. Soc Sci Med (2016) 163:135–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00243.x

77. Brydsten A, Rostila M, Dunlavy A. Social integration and mental health - a decomposition approach to mental health inequalities between the foreign-born and native-born in Sweden. Int J Equity Health (2019) 18(1):48. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12998

78. Jegannathan B, Dahlblom K, Kullgren G. Outcome of a school-based intervention to promote life-skills among young people in Cambodia. Asian J Psychiatr (2014) 9:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.07.005

79. Jenkins EK, Bungay V, Patterson A, Saewyc EM, Johnson JL. Assessing the impacts and outcomes of youth driven mental health promotion: a mixed-methods assessment of the Social Networking Action for Resilience study. J Adolesc (2018) 67:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12939-019-0950-1

80. Thurman TR, Nice J, Luckett B, Visser M. Can family-centered programing mitigate HIV risk factors among orphaned and vulnerable adolescents? Results from a pilot study in South Africa. AIDS Care (2018) 30(9):1135–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2014.01.011

81. Haslam C, Cruwys T, Haslam SA, Dingle G, Chang MX. Groups 4 health: evidence that a social-identity intervention that builds and strengthens social group membership improves mental health. J Affect Disord (2016) 194:188–95. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.05.009

82. McCay E, Quesnel S, Langley J, Beanlands H, Cooper L, Blidner R, et al. A relationship-based intervention to improve social connectedness in street-involved youth: a pilot study. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs (2011) 24(4):208–15. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2018.1455957

83. Olowokere AE, Okanlawon FA. The effects of a school-based psychosocial intervention on resilience and health outcomes among vulnerable children. J Sch Nurs (2014) 30(3):206–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.010

84. McCay L, Bremer I, Endale T, Jannati M, Jihyun Yi. Urban Design and Mental Health. In: Okkels N, Kristiansen C, Povl M-J, editors. Mental Health and Illness in the City. Mental Health and Illness Worldwide. Singapore: Springer (2017). doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2011.00301.x

85. Decker MR, Peitzmeier S, Olumide A, Acharya R, Ojengbede O, Covarrubias L, et al. Prevalence and Health Impact of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-partner Sexual Violence Among Female Adolescents Aged 15-19 Years in Vulnerable Urban Environments: A Multi-Country Study. J Adolesc Health (2014) 55(6 Suppl):S58–67. doi: 10.1177/1059840513501557

86. Kapungu C, Petroni S. Understanding and Tackling the Gendered Drivers of Poor Adolescent Mental Health. Washington, DC: International Center for Research on Women (2017). doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-0752-1_12-1

87. Soleiman Ekhtiari Y, Shojaeizadeh D, Rahimi Foroushani A, Ghofranipour F, Ahmadi B. The Effect of an Intervention Based on the PRECEDE- PROCEED Model on Preventive Behaviors of Domestic Violence Among Iranian High School Girls. Iran Red Crescent Med J (2013) 15(1):21–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.022

88. Jewkes R, Gibbs A, Jama-Shai N, Willan S, Misselhorn A, Mushinga M, et al. Stepping Stones and Creating Futures intervention: shortened interrupted time series evaluation of a behavioural and structural health promotion and violence prevention intervention for young people in informal settlements in Durban, South Africa. BMC Public Health (2014) 14(1):1325. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.3517

89. Cholera R, Gaynes BN, Pence BW, Bassett J, Qangule N, Macphail C, et al. Validity of the patient health questionnaire-9 to screen for depression in a high-HIV burden primary healthcare clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. J Affect Disord (2014) 167:160–6. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.3517

90. Ashburn K, Kerner B, Ojamuge D, Lundgren R. Evaluation of the Responsible, Engaged, and Loving (REAL) Fathers Initiative on Physical Child Punishment and Intimate Partner Violence in Northern Uganda. Prev Sci (2017) 18(7):854–64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1325

91. Nelson SE, Wilson K. The mental health of Indigenous peoples in Canada: a critical review of research. Soc Sci Med (2017) 176:93–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.06.003

92. Gutierrez-Garcia RA, Benjet C, Borges G, Mendez Rios E, Medina-Mora ME. NEET adolescents grown up: eight-year longitudinal follow-up of education, employment and mental health from adolescence to early adulthood in Mexico City. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry (2017) 26(12):1459–69. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0713-9

93. Rodwell L, Romaniuk H, Nilsen W, Carlin JB, Lee KJ. Adolescent mental health and behavioural predictors of being NEET: a prospective study of young adults not in employment, education, or training. Psychol Med (2018) 48(5):861–71. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.021

94. Vancea M, Utzet M. How unemployment and precarious employment affect the health of young people: A scoping study on social determinants. Scand J Public Health (2017) 45(1):73–84. doi: 10.1007/s00787-017-1004-0

95. Rotheram-Borus MJ, Lightfoot M, Kasirye R, Desmond K. Vocational training with HIV prevention for Ugandan youth. AIDS Behav (2012) 16(5):1133–7. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717002434

96. Dunbar MS, Kang Dufour MS, Lambdin B, Mudekunye-Mahaka I, Nhamo D, Padian NS. The SHAZ! project: results from a pilot randomized trial of a structural intervention to prevent HIV among adolescent women in Zimbabwe. PloS One (2014) 9(11):e113621. doi: 10.1177/1403494816679555

97. Giles-Corti B, Kelty SF, Zubrick SR, Villanueva KP. Encouraging walking for transport and physical activity in children and adolescents: how important is the built environment? Sports Med (2009) 39(12):995–1009. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0007-y

98. Vallee J, Cadot E, Roustit C, Parizot I, Chauvin P. The role of daily mobility in mental health inequalities: the interactive influence of activity space and neighbourhood of residence on depression. Soc Sci Med (2011) 73(8):1133–44. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113621

99. Melis G, Gelormino E, Marra G, Ferracin E, Costa G. The Effects of the Urban Built Environment on Mental Health: A Cohort Study in a Large Northern Italian City. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2015) 12(11):14898–915. doi: 10.2165/11319620-000000000-00000

100. McCay L, Abassi A, Abu-Lebdeh G, Adam Z, Audrey S, Barnett A, et al. Scoping assessment of transport design targets to improve public mental health. J Urban Des. Ment Health (2017) 3(8).

101. Shiffman J. A social explanation for the rise and fall of global health issues. Bull World Health Organ (2009) 87(8):608–13. doi: 10.3390/ijerph121114898

102. Ostrom E. Institutional rational choice: an assessment of the institutional analysis and development framework. In: Sabatier P, editor. Theories of the policy process. Boulder, CO: Westview Press (2007). p. 21–65. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.060749

103. Kapungu C, Petroni S, Allen NB, Brumana L, Collins PY, De Silva M, et al. Gendered influences on adolescent mental health in low-income and middle-income countries: recommendations from an expert convening. Lancet Child Adolesc Health (2018) 2(2):85–6. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.060749

104. Sinha M, Collins P, Herrman H. Collective action for young people’s mental health: the citiesRISE experience. World Psychiatry (2019) 18(1):114–5. doi: 10.4324/9780367274689-2

105. Bhugra D, Ventriglio A, Castaldelli-Maia J, McCay L. Urban Mental Health. Oxford Cultural Psychiatry Series. Oxford: Oxford University Press (2019). doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(17)30152-9

106. Jack H. (2019). Ministry of Health and Child Care, Department of Mental Health Services, Mental Health Research Task Force Meeting, 2 February 2019.

107. Carpenter RC. Setting the advocacy agenda: Theorizing issue emergence and nonemergence in transnational advocacy networks. Int Stud Q (2007) 51(1):99–120. doi: 10.1093/med/9780198804949.001.0001

108. Colombini M, et al. Factors shaping political priorities for violence against women-mitigation policies in Sri Lanka. BMC Int Health Hum Rights (2018) 18(1):22. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2478.2007.00441.x

109. Oni T, Smit W, Matzopoulos R, Hunter Adams J, Pentecost M, Rother HA, et al. Urban Health Research in Africa: Themes and Priority Research Questions. J Urban Health (2016) 93(4):722–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2478.2007.00441.x

110. Vearey J, Luginaah I, Magitta NF, Shilla DJ, Oni T. Urban health in Africa: a critical global public health priority. BMC Public Health (2019) 19(1):340. doi: 10.1186/s12914-018-0161-7

111. Hann K, Pearson H, Campbell D, Sesay D, Eaton J. Factors for success in mental health advocacy. Global Health Action (2015) 8:28791–1. doi: 10.1007/s11524-016-0050-0

112. Chisholm D, Sweeny K, Sheehan P, Rasmussen B, Smit F, Cuijpers P, et al. Scaling-up treatment of depression and anxiety: a global return on investment analysis. Lancet Psychiatry (2016) 3(5):415–24. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6674-8

113. Collins PY, Insel TR, Chockalingam A, Daar A, Maddox YT. Grand challenges in global mental health: integration in research, policy, and practice. PloS Med (2013) 10(4):e1001434. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.28791

Keywords: adolescents, urban health, mental health, sustainable cities, global development, social determinants, sustainable development goals, health policy

Citation: Murphy LE, Jack HE, Concepcion TL and Collins PY (2020) Integrating Urban Adolescent Mental Health Into Urban Sustainability Collective Action: An Application of Shiffman & Smith’s Framework for Global Health Prioritization. Front. Psychiatry 11:44. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00044

Received: 10 June 2019; Accepted: 17 January 2020;

Published: 20 February 2020.

Edited by:

Manasi Kumar, University of Nairobi, KenyaReviewed by:

Franz Gatzweiler, Institute of Urban Environment (CAS), ChinaMaria Francesca Moro, University of Cagliari, Italy

Copyright © 2020 Murphy, Jack, Concepcion and Collins. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Pamela Y. Collins, pyc1@uw.edu

Lauren E. Murphy

Lauren E. Murphy Helen E. Jack

Helen E. Jack Tessa L. Concepcion3

Tessa L. Concepcion3 Pamela Y. Collins

Pamela Y. Collins