- 1Centre for Sustainable Animal Stewardship, Division of Animals in Science and Society, Department of Population Health Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands

- 2Division of Farm Animal Health, Department of Population Health Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands

- 3Department of Public Administration and Sociology, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, Netherlands

- 4Division of Companion Animal Health, Department of Clinical Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands

Farm animal veterinarians are often involved in on-farm end-of-life (EoL) decisions and questions concerning euthanasia. These decisions can be challenging for the veterinarian, particularly if the interests of the animal and owner conflict. Moreover, the challenge is related to fundamental assumptions about roles and responsibilities veterinarians ascribe to themselves in EoL situations. Getting insight into what roles and responsibilities veterinarians perceive in these situations is important to understand the challenges veterinarians face and to explore ways to enable them to manage such situations. Existing literature and professional guidelines do not provide sufficient clarity and guidance in terms of the role conception and responsibilities of veterinarians in on-farm EoL situations. The objective of the current qualitative study was to better understand the views of farm animal veterinarians in the Netherlands regarding their roles and responsibilities associated with on-farm EoL situations. In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with 19 farm animal veterinarians. In terms of roles in EoL situations, our analysis shows that 1) seven roles can be distinguished based on the interviews, 2) two contextual dimensions influence role perception: a) the stage in which a veterinarian gets involved at the end of an animal’s life and b) the question of whose interests should be taken into consideration and how to prioritize (conflicting) interests by a veterinarian, 3) veterinarians enact a number of the identified roles and the combination of roles varies between individuals and 4) the individual veterinarian changes between roles depending on contextual aspects. In terms of responsibilities in EoL situations, analyses show that 1) individual veterinarians perceive a combination of five identified responsibilities, and 2) the perception of responsibilities relates predominantly to specific animal sectors. This insight into the roles and responsibility perceptions of veterinarians facilitates understanding the challenges veterinarians face in on-farm EoL situations and creates a starting point for how veterinarians can be supported to deal with potential conflicts of interest. These insights could also be valuable in the training of future veterinarians and lifelong learning of veterinarians as it provides a starting point to reflect on, and discuss, one’s role and responsibility in EoL situations.

1 Introduction

When a farm animal raised for production is ill or injured to the extent that recovery is unlikely, transport and slaughter of the animal are out of the question. Consequently, end-of-life (EoL) decisions and questions concerning euthanasia will arise. The decision to end an animal’s life often comes with various questions for animal owners1 (Meijboom and Stassen, 2016). One can think of questions regarding matters such as valid indications, the preferred method, requirements regarding the executioner, timing, emotional bonding, and economics. In on-farm situations, these questions are even more prominent than in the contexts of animal slaughter or disease control, because in the Netherlands there is less regulation and consequently more professional freedom for the veterinarian. (Council Regulation (EC) No 1099/2009 on the protection of animals at the time of killing, 2009).

Farm animal veterinarians play a role in on-farm EoL situations in the decision-making process of the animal owner and/or in the act of ending an animal’s life. In this paper, ‘ending of an animal’s life’ is used to cover situations of killing ill or injured animals. This excludes on-farm killing for reasons of disease control or the production of animal products. This focus entails euthanasia as well as the humane killing of animals. We are aware of the conceptual complexity of both terms (McMahan, 2002; Yeates, 2010; Fawcett, 2013; Kasperbauer and Sandøe, 2015; Cholbi, 2017) and that it is debated whether all forms of humane killing constitute ‘euthanasia’. The term ‘euthanasia’ is used in this paper to refer to both killing an animal in the interest of the animal as well as the humane killing of an animal when not truly in its interest. We do so because the participants of the current study used the concept of euthanasia in a broad way that includes situations in which animals are killed for reasons other than their own interests.

In these EoL situations, veterinarians are confronted with the (presumed) interests of the animal and those of the animal owner. Serving the interests of both the animal and the animal owner can be challenging for the veterinarian, especially when these interests conflict (Dürnberger, 2020a; Shaw and Lagoni, 2007; Yeates, 2013; Sandøe et al., 2016; Kipperman et al., 2018). Moreover, animals are considered the legal property of an animal owner in Western jurisdictions (Burgerlijk Wetboek Boek 3, 1992). As a result, the final decision-making power in an EoL situation is in the hands of the animal owner. This further complicates an EoL situation for the veterinarian when an animal owner does not adhere to the veterinarian’s recommendation. The challenge is more comprehensive than dealing with conflicts, it is related to fundamental assumptions about role and responsibility perception in EoL situations. At this fundamental level, there seems to be a diversity of views that starts with the profound question raised by Rollin: does the veterinarian owe primary allegiance to the animal or the owner (Rollin, 2006)? Therefore, getting further insight on what roles and responsibilities veterinarians ascribe to themselves in EoL situations is important to understand the challenges they are confronted with and to explore ways to enable them to handle such situations.

Different roles among farm animal veterinarians have been reported. In a qualitative online survey, Dürnberger researched situations that were experienced as morally challenging in the professional lives of farm animal veterinarians. Six roles and self-understandings were identified: ‘advocates of the animals’, ‘entrepreneur’, ‘social worker’, ‘part of agriculture’, ‘colleagues, supervisors, employees and competitors’, and ‘private person’(Dürnberger, 2020a). This study provides helpful insights into the multiple roles farm animal veterinarians see for themselves, however, whether farm animal veterinarians actually ascribe these roles in on-farm EoL situations is not yet known.

Next to the views of farm animal veterinarians themselves, different views in society exist on what can be reasonably expected from a veterinarian in on-farm EoL situations. Consider the situation of a calf with a broken limb. Some people might expect a veterinarian to advocate for the treatment of the calf, whereas others think the veterinarian should strive for ending the calf’s life. Depending on one’s own perspective on this case example, one might consider the role of the veterinarian differently. (Morgan and McDonald, 2007; Kipperman et al., 2018; Rollin, 2011; Yeates, 2010)

Despite the limited literature on the roles and responsibilities of farm animal veterinarians in on-farm EoL situations, one could argue that the code of professional conduct is a relevant entry point (Koninklijke Nederlandse Maatschappij voor Diergeneeskunde, 2010). In the Dutch ‘Code voor de Dierenarts’ professional standards and responsibilities are set out for individual veterinarians. Regarding the ending of animal lives, article 2.3 of the ‘Code voor de Dierenarts’ states

Veterinarians provide first aid and/or pain relief to animals in distress to the best of their ability. This also applies to wild animals or animals whose owner is unknown. To prevent serious and hopeless suffering, it may be necessary to euthanize the animal in a responsible manner. Such emergency veterinary assistance will be immediately notified to the owner and/or keeper of the animal, to the extent known. (Koninklijke Nederlandse Maatschappij voor Diergeneeskunde, 2010)

Article 2.3 does not provide specific guidance. When suffering is defined as serious and hopeless, for example, remains unspecified. Moreover, the code provides limited information as article 2.3 is the only article about the ending of animal lives. Guidance on the role and responsibility of the veterinarian is minimal as information on, for example, situations in which the animal owner disagrees with the ending of the animal’s life is not included. The Dutch code of professional conduct is therefore inconclusive about how veterinarians should fulfill their responsibilities and what their roles should be in different EoL situations.

Concluding, existing literature and the Dutch code of professional conduct only partially help to clarify what the roles and responsibilities of farm animal veterinarians are in on-farm EoL situations. The code of conduct does not provide sufficient clarity and guidance to understand the challenges veterinarians face in end-of-life situations and to support veterinarians in handling the related conflicts of interest. As a consequence, veterinarians in practice are left wondering what their roles and responsibilities should be and how to fulfill them. Therefore, it is relevant to explore the perceptions of farm animal veterinarians regarding their roles and their views on responsibilities in on-farm EoL situations. The objective of the current qualitative study was to better understand the views of farm animal veterinarians in the Netherlands regarding their roles and responsibilities associated with on-farm EoL situations.

2 Materials and methods

The character of the current study is explorative and results in a two-step approach. Our first step is to document the diversity of roles and responsibilities farm animal veterinarians perceive. We define a role as a position a person sees for him/herself in a specific situation, accompanied by specific behavior. Underlying such a position, specific perceptions of responsibility are grounded. We define responsibility as a conviction a person perceives. The interplay between a role and a responsibility is that a perceived responsibility incites a person to enact one or more roles. In other words, the perceived responsibility is the grounded conviction and the roles form an expression of that underlying conviction. As a result of our first step, we describe an overview of the perceived roles and responsibilities of farm animal veterinarians.

The roles a person enacts can be influenced by context, therefore, in our second step we explore the relevant contextual aspects related to the roles farm animal veterinarians perceive. By identifying these contextual aspects, we make explicit what characterizes the identified roles. Making this characterization explicit can be particularly helpful to uncover the origins of the challenges veterinarians face in end-of-life situations. Consequently, the characterization helps to understand the factors that should be taken into account when supporting veterinarians.

2.1 Study design

In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted by the first author with Dutch farm animal veterinarians between June and October 2021. As a veterinary graduate, the interviewer has experience as a veterinary student with the practices explored in the current research project. The recruitment criteria for the inclusion of participants were that the individuals worked in the Netherlands as farm animal veterinarians in a non-referral clinic of which the caseload consisted mainly of the healthcare of ruminants and small ruminants, pigs, poultry, or a combination of these species. These three animal sectors were chosen as most farm animal veterinarians in the Netherlands work in these sectors. Consequently, farm animal veterinarians working in numerous animal sectors were surveyed and compared. The selection of participants in this study aimed to achieve a participant pool that 1) varies in years of working experience, 2) is geographically spread throughout the Netherlands, and 3) has an approximate 50/50 ratio between male and female veterinarians. Purposive sampling via the snowball method was used to select the participants (Polkinghorne, 2005). As a result, a mixed group of participants was selected including a minority from the professional network of the authors and a majority from the network of the participants. Eligible participants were contacted personally by the first author. After the initial contact, participants were invited through email. In this email, participants received background information about the research project, research goals, and data collection in a letter of information, accompanied by an informed consent form. In the supplementary materials, we included the informed consent form (Supplementary material 1), the information letter (Supplementary material 2), and interview guide section A (Supplementary material 3). These materials are translated from Dutch to English and slightly edited for readability. The number of veterinarians interviewed was determined by theme saturation. (Guest et al., 2006).

2.2 Contextual background

In the Netherlands, future veterinarians are educated at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of Utrecht University. The educational program consists of a three-year generic bachelor, followed by a three-year master’s program in which the students devote themselves to the healthcare of one of three disciplines: companion animals, horses, or farm animals. In addition, each student participates in a clinical rotation period in the healthcare of the other two disciplines. As a result, students have general knowledge of all disciplines and more specialized knowledge of the discipline to which they have devoted themselves. Besides training in veterinary core competencies, animal welfare, veterinary public health, and the training of ‘soft skills’ such as veterinary ethics and communication are addressed specifically. Veterinary graduates have a general qualification and are legally allowed to provide care to all species.

Most farm animal graduates work in a species-specific practice with either ruminants and small ruminants, pigs, or poultry. Some of them combine this with veterinary care for horses or companion animals. The Dutch farming context is characterized by little direct official control by governmental organizations. Many food safety and welfare controls are performed by private quality control systems. In their day-to-day work, farm animal veterinarians visit farms regularly. Based on the national law and sectoral agreements of the ‘Stichting Geborgde Dierenarts’, each farm has a contract with one veterinarian (Regulation (EU) 2019/6 of the European Parliament and of the Council on veterinary medicinal products and repealing Directive 2001/82/EC, 2018; Stichting Geborgde Dierenarts, 2022). Based on this contract, that specific veterinarian is appointed to visit the farm for matters of animal health, public health, and food safety. The frequency of visits is officially regulated. Most farms are visited at least once every four weeks (pigs), once every twelve weeks (dairy), and once every production cycle (poultry). Veterinarians visit most farmers more frequently for reasons such as (acute) health problems, to monitor animal health in high-risk periods such as the weaning period or to monitor fertility. Regarding on-farm killing, Council Regulation (EC) No 1099/2009 on the protection of animals at time of killing is applicable. Article 7 states: ‘Killing and related operations shall only be carried out by persons with the appropriate level of competence to do so without causing the animals any avoidable pain, distress or suffering’ (Council Regulation (EC) No 1099/2009 on the protection of animals at the time of killing, 2009). In practice, this means that not only veterinarians but also competent animal owners perform the act to end an animal’s life.

Next to the legal and practical context, farm animal veterinarians may experience the influence of changing societal views on animals and human-animal interactions. A study by the Dutch Council on Animal Affairs (Council on Animal Affairs, 2019) shows that public perceptions regarding animals are changing and that animal welfare is widely recognized as an important concern in how to relate to animals. It is plausible that this growing public awareness influences the status of veterinarians as one of the stakeholders involved in the care of animals. Consequently, veterinarians may experience that their roles and actions on a farm are evaluated more critically.

2.3 Interview structure and data management

The interviews were all held in person at a location of choice by the interviewee to create an open and safe environment. Before the interview, the interviewer introduced herself and informed the interviewee about the interview structure and the informed consent form. The interviewer explicitly asked if any questions should be addressed before the start of the interview. Additionally, the interviewee’s approval for recording the interview was requested. Interviewees received a digital copy of their signed informed consent form. With the oral and written consent of the interviewee, the interview started using open-ended questions from the interview guide. The interview questions were not made available to the interviewees before their interview. Interviewees shared their ideas and thoughts and were not guided toward answers by the use of, for example, a list of potential answer options. The interview guide focused on three main subjects including 1) the role and responsibilities of the veterinarian in EoL situations, 2) the considerations veterinarians take into account in the decision-making process in EoL situations and 3) the barriers experienced by veterinarians in the performance of and decision-making process towards euthanasia. Due to the amount of data and the importance of the first subject of the study, this paper focuses on the roles and responsibilities of the veterinarian in EoL situations. The second and third subjects will be discussed in future work.

The length of the interviews varied between 45 and 120 minutes. Audio files were transcribed using Amberscript™ (Version August 2021, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). All transcripts were reviewed by ED to ensure quality and accuracy. Any information in the transcripts which related to a specific person or veterinary practice was replaced by non-identifiable descriptors (e.g. ‘colleague’ or ‘veterinary practice’).

2.4 Data analysis

Transcripts were explored for themes using template analysis in NVivo™ qualitative analysis software (Version Release 1.5.1). Template analysis is a form of thematic analysis in which the use of hierarchical coding is emphasized but balances a highly structured process of analyzing textual data with the flexibility to adjust to the needs of a study (Brooks et al., 2015). A coding template was developed to explore the transcripts. To define an initial coding template, open coding was used by three of the authors to create codes based on a subset of the transcripts. During an iterative reflective process between the authors, the created codes were revised and refined based on subsequent transcripts. After this iterative reflective process, the finalized coding template was applied to the full data set.

Using the finalized coding template, the interview data were analyzed to characterize patterns and diversity of responses. As a result, abstractions of the roles and responsibilities mentioned by the interviewees were formulated, see Overview 1 in the results section. Additionally, dimensions underlying the identified roles were defined based on the patterns in the interview data.

2.5 Ethical approval

This research project was reviewed and approved by the Science-Geosciences Ethics Review Board (SG ERB) of Utrecht University on May 28th, 2021, subject ERB Review DGK S-21552.

3 Results

3.1 Demographics

Nineteen Dutch farm animal veterinarians participated, ten males and nine females. Seven of the participants worked with ruminants and small ruminants, eight participants worked with pigs, and four participants worked with poultry. Five of the participants worked partly with companion animals or horses. Six veterinarians had less than five years of working experience, four had five up to 10 years of experience, another four had ten to fifteen years of experience, and five had more than fifteen years of experience.

3.2 Thematic template

The final thematic template comprised seven roles and five responsibilities that interviewees ascribed to themselves (Overview 1). In the following section, the results will be presented by quotes. All quotes were translated from Dutch to English and slightly edited for readability. Direct quotes from veterinarians are in italics. Additional words inserted by the authors to clarify the meaning of the quotations are placed between square brackets. Filler words were replaced by a set of three periods in the quotation. Quotes are referred to by an abbreviation of the species to which the veterinarian is devoted, Pi for pigs, Po for poultry, and Ru for ruminants, and a sequential number to identify the individual interviewee but still retain anonymity (e.g. Pi5 = the fifth pig veterinarian interviewed).

Overview 1 Final thematic template

Role description

a. Advisor

b. Animal advocate

c. Decision-maker

d. Educator

e. Counselor

f. Surveillant

g. Executioner

Responsibilities

a. Discussing EoL

b. Good veterinary daily practice

c. Safeguarding animal welfare

d. Surveillance

e. Service

3.3 Roles of the veterinarian

In section 3.3.1 we present an overview of the conceptualization of the perceived roles described by the interviewees, followed in section 3.3.2 by the patterns we discovered in the data regarding the interviewees’ roles. In section 3.3.3 we introduce the contextual aspects that underlie the described roles. In section 3.3.4 we describe how changes in these underlying contextual aspects relate to the roles of veterinarians.

3.3.1 Description of roles

Regarding the role of a veterinarian in EoL situations, seven roles were identified 1) advisor, 2) animal advocate, 3) decision-maker, 4) educator, 5) counselor, 6) surveillant, and 7) executioner. Based on the interview data, a role conceptualization is composed for each of the identified roles.

An advisor is characterized as a veterinarian who provides advice to the animal owner in the decision-making process by balancing multiple interests. The animal owner is the one who is deciding in the end. The veterinarian values the considerations of the animal owner and respects the interdependence of the veterinarian’s and owner’s responsibility, as Pi5 narrates: “My role is mainly advising. I don’t want to adopt the role of the animal owner. I try to give direction, but the animal owner must decide in the end. [ … ] I propose and ask permission to euthanize animals.”

The animal advocate is dedicated to the (presumed) interest of the animal and is committed to motivating the animal owner to put the animal’s interest above other interests. A veterinarian describes this role as follows: “I am not a great world saver, but I think that we are ultimately animal advocates, so those animals cannot decide at which farm they live. If I could choose on which farm they would live, I could distribute them easily but that is not possible. So then we need to optimize the conditions in which they live in such a way that we get the best out of it.” (Ru7)

In the role of decision-maker, the veterinarian is authorized to make a decision on behalf of the owner in EoL situations. The veterinarian is allowed to select animals for diagnostic purposes or in case an animal is eligible for euthanasia from the veterinarian’s perspective as an interviewee states: “With some of my farmers, I have an agreement that I can perform it [euthanasia] without consultation of the owner, so they trust me blindly to make a good choice. In case I doubt, they know I will come to them to discuss what to do.” (Pi7)

Sharing knowledge, discussing patients, and providing training skills are part of the role of educator. Veterinarians who take this role focus on the one hand on educating animal owners on how to select the right animals, at the right moment and on the other hand on how to end the lives of these animals by the use of a proper method. As Po1 narrates: “One person is more experienced, more skilled than the other. So sometimes you visit a farm and then there is a new employee or a younger poultry farmer who has clearly never received proper instruction or who does not have sufficient experience. [ … ] I have no problem doing it [euthanasia] myself, but then it must be as quick and effective as possible, so then it is my role to actually educate those people to do it in a proper way themselves.” Regarding the selection of animals in the role of educator, Po2 elaborates: “That [euthanasia by the animal owner] comes with some education on how to select animals. The timing is in that perspective also relevant as some animals may be in a bad condition right now, but some may end up in a bad condition in a few days.”

In the role of counselor, a veterinarian focuses on the social-emotional needs of the animal owner. An interviewee described it as follows: “I know that there are more emotions involved as I am aware that these people do not keep this cow to gain more milk […, but] as a companion animal, for its ‘retirement’. Then I think ‘we should not end this life abruptly, we have more options’.”(Ru7)

Where the role of educator focuses on the education of the animal owner by sharing knowledge and providing training of skills, the role of surveillant covers monitoring how the animal owner puts the knowledge and skills into practice in an EoL situation. Monitoring the decision-making process and performance of euthanasia by others than the veterinarian is the main focus of a surveillant, as Po2 describes: “Farmers euthanize animals themselves, so you have to keep an eye on if they do that in the right way.”(Po2)

The role of executioner consists exclusively of the act of ending an animal’s life lege artis2, such as the following interviewee points to: “I should be able to do it properly at all times, I think. So I ensure that I always have the needed equipment with me.”(Pi4) Veterinarians indicate that performing the act lege artis was essential to avoid unnecessary suffering or stress for the animal.

3.3.2 Role patterns

Each interviewee ascribed a combination of the above-mentioned roles to themselves, ranging from two up to four roles. Regarding interviewees’ characteristics, no relationship is seen between role description and sex or years of work experience. The majority of the interviewees recognized themselves in the role of advisor. The role of animal advocate and executioner were mentioned by half of the interviewees. The role of counselor was described least frequently.

The roles of decision-maker, educator, and surveillant were only described by veterinarians working with pigs or with poultry. The responsibility of the animal owner to end an animal’s life when needed turned out to be of relevance for the veterinarian in these roles. As the quote of Pi7 in the description of the role of decision-maker shows, a delegation of the animal owner’s responsibility to the veterinarian is a very relevant aspect of the decision-maker’s role. In the role of educator and surveillant, veterinarians focus on the decision-making process and the act of ending an animal’s life by others than the veterinarian respectively, such as the animal owner or caretakers at a farm. Veterinarians describe the relevance of the animal owner as they are, from the perspective of the veterinarian, responsible to euthanize animals whenever needed. Therefore, educators provide relevant information on killing methods, discuss decision-making and selection of animals, and train others to become competent. Surveillants on the other hand mention that their role is to monitor if the correct animals are euthanized properly at the right moment by animal owners.

3.3.3 Dimensions

In the data, we discovered contextual aspects that underlie the described roles. In this section, we present these contextual aspects as two dimensions. These dimensions help to explicate how the described roles relate to each other.

The first dimension that follows from the interview data is the stage in which a veterinarian gets involved at the end of an animal’s life. In the interviews, the involvement of veterinarians ranges from being involved in the entire decision-making process up to the situation in which the veterinarian is only involved in the act of ending the life of an animal itself. When veterinarians are involved in the decision-making process, they indicate that they enact the roles of advisor, animal advocate, decision-maker, and counselor. When veterinarians perform the act to end an animal’s life they define their role as executioner. In between these two endpoints of the continuum, veterinarians identified the roles of educator and surveillant that relate to both the decision-making process and to the act of ending an animal’s life. In these roles, veterinarians are involved in EoL situations by sharing knowledge, discussing patients, providing technical skills, and monitoring how animal owners use this in handling EoL situations.

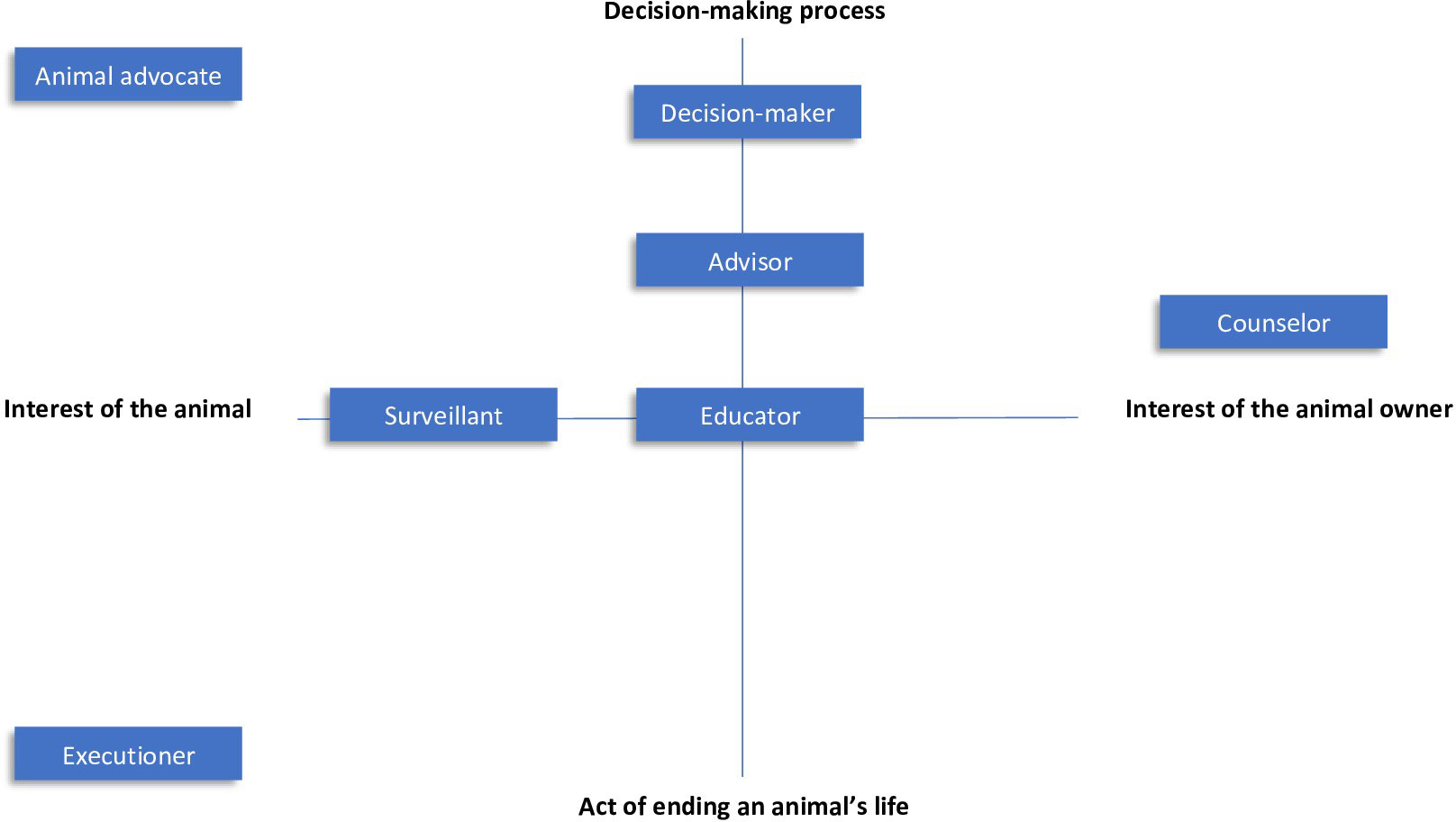

The second dimension that is identified based on the interview data is the question of whose interests should be taken into consideration and how to prioritize (conflicting) interests by a veterinarian As mentioned in the introduction, in EoL situations various interests are at stake (Yeates, 2013; Sandøe et al., 2016). Accordingly, the data show that these interests relate to the animal patient or the animal owner. Depending on which interests are taken into consideration and how these are prioritized, the roles of the interviewees can be positioned on a continuum between animal interest based and owner-related interests. On the one endpoint of this dimension, the role of animal advocate and executioner are identified. In these roles, the (presumed) interests of the animal prevail in either the decision-making process or in the performance of the procedure to end the animal’s life. On the other endpoint, the role of counselor is mentioned. In this role, the interest of the animal owner prevails. In between these endpoints, the roles of advisor, educator, decision-maker, and surveillant are identified. In these roles, the interests of both the animal and the animal owner are taken into consideration. The (presumed) interests of the animal prevail slightly in the role of surveillant, while the roles of advisor and educator have a neutral position. Figure 1. presents an overview of the roles positioned on the continuums of two dimensions.

Figure 1 An overview of the roles veterinarians perceive in EoL situations. Underlying these roles are two contextual dimensions. On the vertical axis is the stage in which a veterinarian gets involved at the end of animal’s life, and on the horizontal axis are the interests taken into consideration and prioritized by the veterinarian.

3.3.4 Changing roles

The interview data show that veterinarians change between roles in EoL situations, e.g. veterinarians shift from the role of advisor to that of animal advocate. These changes are related to the underlying contextual dimensions in terms of the stage of involvement of the veterinarian or the way the interests at stake are prioritized. Veterinarians indicate that changing roles is not a ‘deliberate choice’, but more a ‘natural’ adjustment strongly influenced by the identified contextual aspects such as discussed in the above section.

An example in which the influence of these contextual aspects becomes clear is the relevance of the bond between the animal owner and the animal for veterinarians. Veterinarians shared three cases in which they changed roles based on the bond between the animal owner and the animal. First, veterinarians mentioned that they adjust the procedure of ending an animal’s life depending on the bond of the animal owner and the animal: “If a cow has a special meaning to the farmer or his family, for example, because the cow is named after his daughter, I know I have to euthanize her differently [in how the procedure is performed, not in the medication used]. I don’t believe that either my standard procedure or this adjusted procedure makes any difference for the cow. Though for the farmer it is important as there are more emotions at stake.”(Ru7) The role of counselor became prominent as the veterinarian adjusted the procedure by devoting more attention to the emotional needs of the animal owner. In the former example, validation of the animal owner’s decision could be a very relevant aspect of the emotional support provided by the veterinarian as described in previous literature regarding companion animal owners. (Littlewood et al., 2021).

Second, veterinarians are involved in the healthcare of animals kept as companions which they usually see on professional farms. One can think of pigs, goats, or chickens. Veterinarians indicated that the role of counselor is becomes more prominent in such a situation due to the bond between the animal and the owner: “…with owners who keep animals a hobby you must now and then take a more guiding role. They really ask you what you would do and expect you to guide them in the decision-making. With farmers that is not the case, they ask your advice but they don’t ask you to steer.”(Pi1)

Last, some of the interviewees work in a practice in which they also provide healthcare for horses or companion animals. For these veterinarians, the role of counselor is very relevant as one of the interviewees narrates: “My role is way more important in the companion animal practice. For the animal itself, there is no difference as I always try to do it [ending the animal’s life] in the best way. For the animal owners, however, I can make a difference. I can help them in the decision-making process, and help them to determine the best moment. With dairy cows that is rarely the case, that is mostly already decided when I come to the farm and then I try to perform the procedure in a proper way for the cow and not necessarily for the farmer.”(Ru5)

3.4 Responsibilities of the veterinarian

In section 3.4.1 we present an overview of the conceptualization of the perceived responsibilities described by the interviewees. The patterns we discovered in the data regarding the interviewees’ perceived responsibilities will be described in section 3.4.2.

3.4.1 Description of perceived responsibilities

After analyses of the interview data, five responsibilities concerning EoL situations were identified 1) discussing EoL, 2) good veterinary daily practice, 3) safeguarding animal welfare, 4) surveillance, and 5) providing service. Based on the interview data, a conceptualization is composed for each of the identified responsibilities.

The responsibility of discussing EoL refers to veterinarians who feel the need to open the discussion and address EoL-related questions and concerns, e.g. the use of undesirable killing methods or animals in need of acute care, as referred to by Pi3: “you notice that some farmers are very consistent and take good care of it, but there is also a group who almost doesn’t seem to care at all. Then it is a subject I discuss a couple of times, however not necessarily every visit.” The responsibility of discussing EoL is interlinked with the responsibility of safeguarding animal welfare, as animal welfare concerns can be part of the discussion between the veterinarian and the animal owner. Also, other matters such as financial considerations and personal convictions that potentially affect EoL-related questions and concerns can be discussed.

Veterinarians share various aspects related to EoL situations that we conceptualize as a responsibility towards good veterinary daily practice. First, this is presented as a responsibility to have up-to-date medical knowledge, as described by Ru6 “I need to keep myself up to date about treatment options and how to diagnose [a disease] correct, that is a major responsibility in my opinion.”. Second, they mention the need for an appropriate level of competence in killing methods, as Ru1 points out “It is really a responsibility to perform it [euthanasia] in a very proper way.”. Interviewees indicate that being competent in killing methods is relevant in two ways. On the one hand, when a veterinarian is experienced in performing a specific method, it remains relevant that every time a method is used it is performed most properly. On the other hand, when a veterinarian is less experienced in performing a specific method, it is necessary to achieve an appropriate level of competence. Last, knowledge of and working according to legislation and regulations is seen as part of their responsibility.

In the interviews, veterinarians mentioned their responsibility to safeguard animal welfare as the reason to protect animals from disease or injuries. The primary emphasis of the interviewees is on the basic health and functioning of animals (Fraser, 2008), as Ru4 narrates: “Animal welfare is a top priority [of my responsibilities]. Anything you can do about that, you must do and that is also with a more rational or sober attitude. If we talk about dairy cattle, you are not able to put a cow on a pillow for example, but you can make sure it doesn’t stay on the grids.”(Ru4)

This perception of animal welfare is remarkable because, in literature, animal welfare is defined broader than safeguarding the basic health and functioning of an animal (Carenzi and Verga, 2009; Ohl and van der Staay, 2012; Mellor et al., 2020). One aspect that is emphasized in these definitions is ‘affective states’ (Fraser and Weary, 2004). One can think of the positive or negative experiences of states like pain, distress, and pleasure. Another aspect that is highlighted is the ability to live a reasonably natural life. The ability to carry out natural behavior and to have natural elements in their environment are emphasized (Fraser and Weary, 2004). This broader perspective on animal welfare is not reflected in the way the interviewed farm animal veterinarians discussed animal welfare as one of their responsibilities during the interviews.

The responsibility of surveillance refers to the duty of monitoring the decision-making process and the performance of euthanasia by others than the veterinarian. As an example: “… it is especially towards the farmer, as they do it [the act of ending an animal’s life] in my absence, which actually means that they do not necessarily kill animals every day, but they do keep an eye on if it needs to be done. And they [farmers or animal caretakers at farms], if needed, do euthanize these animals. That is I think my responsibility as a veterinarian in poultry. That they [farmers or animal caretakers at farms] kill the right animals at the right moment in the right way.”(Po2)

Veterinarians address that it is their responsibility to provide a service when it comes to EoL situations. This service can be the act of ending an animal’s life itself or it refers to making this act financially accessible for animal owners, such as described by one of the interviewees: “I inform them that we use a reduced rate, because there is often a financial component in why they don’t call us, or not that easy, in-between visits. We, therefore, reduced the rate, to lower that barrier a little.”(Pi3)

3.4.2 Patterns in interviewees’ perceived responsibilities

Each interviewee identified multiple perceived responsibilities, ranging from two up to four. Veterinarians shared their perceived responsibilities independently of their roles. The analyses of the data show that specific responsibilities are not exclusively mentioned in combination with a specific role, e.g. the responsibility of safeguarding animal welfare was not exclusively mentioned by animal advocates. Regarding interviewees’ characteristics, no relationship is seen between the described responsibilities and sex or years of work experience.

Good veterinary daily practice was the most frequently described responsibility. Interviewees referred to either 1) sufficient knowledge on subjects like animal health, killing methods, and legislation or 2) an appropriate level of competence to perform the act of ending an animal’s life properly. Half of the interviewees mentioned safeguarding animal welfare as one of their responsibilities. The majority of veterinarians working with pigs and ruminants mentioned animal welfare explicitly. Poultry veterinarians mentioned animal welfare not explicitly but more implicit. The following example quote is illustrative: “… such as an animal in a separation pen of which you know that they will never get better, you need to euthanize them. You need to be proactive on that point. Very often this is neglected and left to the farmer. I think it is your responsibility as a veterinarian to pay attention to it.”(Po4)

The responsibilities discussing EoL, service, and surveillance were mentioned less frequently. Veterinarians working with pigs shared most often that they see it as their responsibility to discuss questions and concerns in EoL situations. Service was perceived as one of their responsibilities by some of the interviewees. On the one hand, some of the veterinarians working with ruminants referred to the act of ending an animal’s life itself as a service. On the other hand, making their service to end an animal’s life financially accessible for animal owners was mentioned by some veterinarians working with pigs. Surveillance was identified as a responsibility by all poultry veterinarians and the minority of the veterinarians working with pigs.

4 Discussion

The current paper aims to better understand the views of Dutch farm animal veterinarians regarding their roles and responsibilities with regard to on-farm EoL situations. The analyses of qualitative data reveals in terms of roles that 1) seven roles can be distinguished, 2) two contextual dimensions which influence role perception were identified, 3) veterinarians enact a number of the identified roles and the combination of roles varies between individuals and 4) the individual veterinarian changes between roles depending on contextual aspects. In terms of responsibilities, the data show that 1) individual veterinarians perceive a combination of responsibilities when it comes to EoL situations, and 2) the perception of responsibilities relates predominantly to specific animal sectors.

4.1 The conceptual background of the perceived roles of farm animal veterinarians

Our first key finding is that farm animal veterinarians describe a variety of roles for themselves when it comes to EoL situations. In previous literature, multiple roles for the veterinarian have been identified (Dürnberger, 2020a; Dürnberger, 2020b; Morgan, 2009). However, the roles do not specifically focus on on-farm EoL situations. The present study adds to this gap in the literature and reveals a variety of roles when focusing on EoL situations.

When we relate our findings to the field of EoL situations in human medicine there are relevant similarities. This especially holds for cases in which the patient, like animals, cannot actively participate in the decision-making process and when there is a physician-surrogate relationship. Examples are EoL situations in the case of care for newborns or the intensive care setting in which relatives have to represent the patient (White et al., 2010; Tucker Edmonds et al., 2016). Despite the similarities with the veterinary context, the identified role of physicians and those of veterinarians differ in scope and content. The identified roles of surveillant or educator, in which the veterinarian educates or monitors animal owners in EoL decision-making and euthanasia performance, are absent in the context of EoL decisions in human medicine. This can partly be explained by differences in the legal context. Where national law in some countries – only under strict conditions - legalizes that physicians can end the life of a human (Wet betreffende de euthanasie, 2002; Wet toetsing levensbeëindiging op verzoek en hulp bij zelfdoding, 2021), legislation concerning the killing of animals is less strictly regulated and only requires an appropriate level of competence (Council Regulation (EC) No 1099/2009 on the protection of animals at the time of killing, 2009). Consequently, not only veterinarians but any competent person is allowed to end animal lives. These legal differences could explain the additional roles identified by farm animal veterinarians when it comes to the ending of animal lives by others than the veterinarian.

This situation of multiple actors who are involved at the end of an animal’s life links to our second key finding: two contextual dimensions that underlie the observed variety of roles. The short comparison shows how the position of the veterinarian is complicated by the fact that they have to deal with the interests of both humans and animals, as described in the second dimension: the question of whose interests should be taken into consideration and how to prioritize (conflicting) interests by a veterinarian. While it is assumed that human physicians are advocates for their patients, whether and how the interest of animals should be taken into account by veterinarians is less clear. This links to debate on the moral status of animals and the implications for the veterinary practice (Carruthers, 1994; Rollin, 2011b). This debate includes many positions ranging from those who deny any moral status to animals to the position that animals and humans have equal moral status. For most of the interviewed veterinarians, animals have moral standing and as a result they take their interests into consideration in decisions at the end of life. This, however only serves as a starting point, but does not yet result in guidance on how to prioritize conflicting interests.

Dealing with human and animal interests is also influenced by the bond between animal and animal owner. As an example, some animals are recognized as individuals such as cows that are identified with a name rather than a number only. Other animals, such as broilers, are kept in large groups and have a uniform appearance that makes recognizing and bonding with an individual animal quite hard. These differences in the human-animal bond affect the extent to which one takes the interests at stake into consideration. Finally, the (in)ability to communicate with an animal about its interests can complicate the extent to which one can include the animal in the decision when one would want to.

4.2 The dynamics of roles

A third key finding was that veterinarians enact a number of the identified roles and that the combination of roles varies between individuals. The results show that two aspects predominantly contribute to differences between individuals. First, beliefs, motives, and experiences may differ between veterinarians. This includes one’s personal perspective on animals, the position of the owner, and one’s own role perception. These personal beliefs, motives, and experiences may lead to a preference in the enactment of particular roles. As an example, someone for whom animal welfare is the motive to be a veterinarian could have a preference for the role of animal advocate. Second, beliefs, motives, and experiences of clients contribute to differences in the roles enacted by veterinarians. In some regions of the Netherlands, for example, animal owners adhere to reformed orthodox Christian belief that supports religious objections against ending an animal’s life. Consequently, veterinarians that are consulted by these owners may enact other roles than veterinarians that are consulted by owners without these convictions. This difference in clientele may contribute to interpersonal differences in roles.

The differences among veterinarians show that there is a level of autonomy for individuals to fulfill their roles. One way of interpreting interpersonal differences is that veterinarians enjoy a large amount of trust from animal owners and society. Without trust, there would probably be stricter regulations and, as a result, less variety in the roles veterinarians can fulfill. Another way of interpreting these differences is that clarity about the professional framework is lacking. The lack of clarity could find its origin at the start of veterinarians’ careers, i.e. that the knowledge and experience gained during their education is not sufficient for the veterinarians’ work in practice.

Dickinson (2019) found that almost all veterinary medicine schools in the United States (US) and United Kingdom (UK) included EoL topics in their curriculum. The average number of teaching hours devoted to EoL was 7 in the US and 21 in the UK (Dickinson, 2019). Addressing students’ feelings regarding death and dying early and throughout the curriculum was recommended to further improve the training of veterinary students. Regarding euthanasia-related technical skills, Cooney et al. (2021) discovered that the average number of teaching hours devoted to these skills was limited to 2.8. More advanced training in euthanasia techniques is recommended to prepare students for practice (Cooney et al., 2021). Based on these findings, it seems important to critically review the Dutch veterinary curriculum on the extent to which the curriculum is devoted to EoL situations.

This leads to our fourth key finding: the individual veterinarian changes between roles depending on contextual aspects. When there is a change in one or both of the underlying dimensions, a change in the role a veterinarian adopts can be identified. This changing of roles is a ‘natural’ adjustment rather than a ‘deliberate choice’ as the interviewees described. Contextual factors relating to the animal or the animal owner strongly influenced changing roles according to the interviewees.

The enactment of multiple roles in EoL situations is previously reported and in some studies even recommended. Lagoni et al. advocate that veterinarians use the educating, supporting, guiding, and facilitating role besides the role as a medical expert in the context of client support (Lagoni et al., 1994). By balancing these roles, veterinarians can usually effectively help clients grieve. Moreover, studies on clients’ experience with EoL decision-making report that animal owners have different preferences for the role of their veterinarian (Christiansen et al., 2015; Littlewood et al., 2021). This finding emphasizes that the adaptability of veterinarians in their role is helpful in the interaction between the veterinarian and different owners during EoL decision-making.

The adaptability of veterinarians in their role can help them in handling EoL situations. When a veterinarian experiences handling an EoL situation as constructive or satisfying, this could benefit the veterinarian’s job satisfaction and sense of accomplishment (Morris, 2012). It can also happen that a veterinarian is unable or unwilling to adapt their role when handling an EoL situation. For instance, when there is a conflict of interest between the interest of the animal owner and the (presumed) interests of the animal. In such a situation, a veterinarian’s adaptability may reach its limits of what is possible or acceptable to the veterinarian. Experiencing such a situation can be stressful and could lead to emotional strain and moral distress (Batchelor and McKeegan, 2012; Moses et al., 2018). In this perspective, it is noteworthy that the second dimension we identified includes the (presumed) interests of the animal owner and the animal. The interest of the veterinarian him- or herself was rarely mentioned. This is notable as one can imagine that the veterinarian’s own motives and beliefs may be relevant as well in defining what the ‘right’ role of the veterinarian should be.

4.3 The perceived responsibilities of farm animal veterinarians

Our first key finding in terms of responsibilities is that individual veterinarians perceive a combination of responsibilities when it comes to EoL situations. Five responsibilities were identified after analyses of interview data 1) discussing EoL, 2) good veterinary daily practice, 3) safeguarding animal welfare, 4) surveillance, and 5) providing service. The responsibilities mentioned appear to be most relevant to the interviewees, which does not necessarily mean that they do not recognize additional responsibilities or that they consider other responsibilities as irrelevant.

Guidelines developed by the veterinary profession can help to further discuss the first key finding. In these codes of professional conduct, the general professional standards and responsibilities are set out. Since we interviewed Dutch veterinarians, we start with the Dutch ‘Code voor de Dierenarts’. However, in this code limited information is provided regarding EoL situations (Koninklijke Nederlandse Maatschappij voor Diergeneeskunde, 2010). Therefore, we also examined other codes of professional conduct. From these professional guidelines, we recognize a wide range of responsibilities ascribed to veterinarians, ranging from responsibilities to animals, clients, colleagues, the veterinary profession, and the public (Canadian Veterinary Medical Association, 2004; American Veterinary Medical Association, 2020 (revised 2018); Koninklijke Nederlandse Maatschappij voor Diergeneeskunde, 2010; Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, 2019; Federation of Veterinarians in Europe, 2019). It would be valuable if, as in these codes of professional conduct, more information on EoL situations would be included in the Dutch code with the help of clinicians and academics with expertise in, for example, veterinary ethics.

The veterinarian’s responsibility for safeguarding animal welfare and good veterinary daily practice were predominant in our data. Accordingly, the responsibility of the veterinarian toward the interest of the animal in terms of animal welfare is emphasized in professional guidelines. An illustrative example from the European Veterinary Code of Conduct is the following: ‘In urgent cases where there are no available means to prevent excessive suffering of the animal(s), veterinarians should consider euthanasia even without the owner’s permission. When taking such a decision veterinarians should consider all possible treatments to the best of their knowledge assuming full responsibility’ (Federation of Veterinarians in Europe, 2019). These guidelines provide high-level guidance, however, professional judgment by the veterinarian is still required as the guidelines are not conclusive about how veterinarians should fulfill their responsibilities and what their role should be in EoL situations.

Although in law, ending animal lives is not solely an act of veterinarians, variation is seen between professional guidelines in being explicit about the responsibility of veterinarians in case others end the life of an animal. Some guidelines only point out that others can carry out the act of ending an animal’s life (Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, 2019), whereas other guidelines explicitly prescribe a responsibility for the veterinarian to train others in the decision-making process and skills (American Veterinary Medical Association, 2020). This variation could indicate different views of veterinary professions on the ending of animal lives by others than the veterinarian.

This leads to our second key finding: the perception of responsibilities relates predominantly to specific animal sectors, such as poultry or ruminant practice. Where the responsibilities of good veterinary daily practice and animal welfare were identified by veterinarians of all farm animal sectors, the responsibilities discussing EoL, surveillance, and service were predominantly mentioned in specific sectors. This indicates that each sector has sector-specific dynamics when it comes to EoL situations that affect the responsibilities a veterinarian perceives.

In the Dutch poultry sector, for example, on-farm killing is mostly performed by the owner. Likewise, in case of piglets most pig farmers perform the act to end the life of weak and diseased animals. This could explain why the poultry and pig interviewees indicated perceiving surveillance as their responsibility. Regarding sows and finisher pigs, owners may need to request an additional visit in case they want their veterinarian to end the animal’s life in between regular visits. The related costs for such a visit could be a barrier for an owner to consult the veterinarian. This could be a reason why pig veterinarians also indicate that it is their responsibility to provide a service by making such a visit financially accessible. Moreover, it could explain why pig veterinarians mentioned discussing EoL as a responsibility. By discussing EoL, veterinarians may better understand what could hold an owner back to reach out in an EoL situation. These insights could help the veterinarian to better support the owner in EoL situations.

Previous literature on the dairy and pig sectors describes what the role of animal caretakers and owners is in EoL situations according to veterinarians (Edwards-Callaway et al., 2020; Wagner et al., 2020). It appeared that caretakers and owners were predominantly the ones who decide in EoL situations. Accordingly, caretakers and owners performed euthanasia in most cases. Veterinarians indicated that they perceive it as their responsibility to train those involved in on-farm euthanasia and assist with developing euthanasia protocols. These findings correspond partly with our data, as interviewees working in the poultry sector identified surveillance as their responsibility as well as a minority of the interviewees working in the pig sector. A difference is seen regarding the findings of the dairy sector, as some of the interviewees in the current study perceived service as their responsibility rather than surveillance. The fact that the lives of dairy cows on Dutch farms are ended by a veterinarian in case this is needed could explain this finding. We suggest that this difference in findings may be explained by differences in sector-specific dynamics, such as the involvement of the owner.

4.4 Linking roles and responsibilities

Our data analyses showed that there was more variety in perceived roles than in perceived responsibilities. We hypothesize that farm animal veterinarians share common ground regarding responsibilities, though the operationalization of these responsibilities in their roles differs. As an example, two veterinarians perceive animal welfare as their responsibility in an EoL situation. It can occur that one veterinarian enacts the role of animal advocate to fulfill the perceived responsibility, whereas the other veterinarian may enact the role of advisor. Although the two veterinarians enact a different role, they both enact these roles to fulfill their perceived responsibility for animal welfare.

4.5 Limitations and future research

Due to the use of specific inclusion criteria and theme saturation to determine the number of interviewees, the current study probably does not cover all potential views on the research question. The generalizability of these findings is, therefore, limited. Additionally, the inclusion of interviewees who were willing to participate, and who therefore may have given answers that they thought the interviewer wanted to hear may have led to data bias. Last, due to the use of the snowball method, the interviewer knew a minority of the interviewees which may have contributed to a data bias.

An interesting direction for future research would be to check and complement the identified roles and responsibilities in an observational study. Additionally, it would be of interest to extend the current research to explore whether farm animal veterinarians experience any obstacles regarding their roles and responsibilities in EoL situations. Moreover, a comparative study among veterinarians dedicated to companion animals or horses would gain an interesting insight into how these veterinarians perceive their roles and responsibilities. Also, research on the perspectives of owners regarding the role and responsibilities of the veterinarian in EoL situations would be interesting, to gain insight into how these perspectives fit with those of the veterinarians. Finally, it is remarkable that in the current data animal welfare is mentioned in a rather limited and function-based interpretation. It is difficult to evaluate this finding because we focused on the end of life which is only one part of the veterinary practice. Our results may thus not provide the full picture of the veterinarians’ view on moral matters including animal welfare. Therefore, it would be relevant to further elaborate on this in future research.

5 Conclusion

The objective of the current qualitative study was to better understand the views of farm animal veterinarians in the Netherlands regarding their roles and responsibilities associated with on-farm EoL situations. Our findings reveal that farm animal veterinarians define seven roles when it comes to EoL situations. Veterinarians enact a number of these roles and the combination of roles varies among veterinarians. Underlying the variety of roles, two contextual dimensions help to better understand how and why individual veterinarians change between roles. Moreover, our findings show that farm animal veterinarians perceive a combination of five responsibilities in EoL situations. Between veterinarians, variation is seen in the responsibilities they perceive, which can be related to the specific animal sector in which the veterinarian works.

These insights help to better understand the role and responsibility perceptions of farm animal veterinarians, which is valuable in two ways. First, it facilitates understanding of the challenges veterinarians face in EoL situations. Secondly, it creates a starting point for how veterinarians can be supported to deal with potential conflicts of interests and related emotional strain and moral distress. Therefore, we see the potential to use the results of the current study in the training of future veterinarians and in the lifelong learning of veterinarians. The gained insights can enable these (future) professionals to reflect on, and discuss, their roles and responsibilities in EoL situations. Courses of the Dutch curriculum in which this could be incorporated are the elective course on euthanasia of animals and the courses on animal ethics and communication. Moreover, reflection and discussion on the roles and responsibilities of the veterinary professional could be done during clinical rotations. As a result, (future) veterinarians have the opportunity to reflect on what they think their roles and responsibilities should be in a clinical setting before they become involved in an EoL situation as a veterinary graduate. Once they are involved in a comparable situation, veterinarians may feel more competent to manage the situation instead of being caught off guard.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Science-Geosciences Ethics Review Board (SG ERB) of Utrecht University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

ED: conceptualization, data collection, formal analysis, writing–original draft. FM and FK: conceptualization, formal analysis, writing-review, and editing. TT, JH, and TR: conceptualization, writing-review, and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded by the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of Utrecht University.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of all farm animal veterinarians who participated in this study. Furthermore, we thank the valuable comments by the reviewers.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fanim.2022.949080/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary material 1 | Informed consent form. The form is translated from Dutch to English and slightly edited for readability.

Supplementary material 2 | Information letter. The letter is translated from Dutch to English and slightly edited for readability. The letter includes background information about the study, the goal of the study, the study design and structure, and the data management.

Supplementary material 3 | Interview guide section A. The interview guide is translated from Dutch to English and slightly edited for readability.

Footnotes

- ^ In this research, we use the term ‘animal owner(s)’ to refer to both animal owner(s) and animal caretaker(s).

- ^ Lege artis refers to performance of an act in the correct way

References

American Veterinary Medical Association (2020). AVMA guidelines for the euthanasia of animals. 2020 edition (Schaumburg: Illinois: AVMA).

Batchelor C., McKeegan D. (2012). Survey of the frequency and perceived stressfulness of ethical dilemmas encountered in UK veterinary practice. Veterinary Rec. 170 (1), 19–19. doi: 10.1136/vr.100262

Brooks J., McCluskey S., Turley E., King N. (2015). The utility of template analysis in qualitative psychology research. Qual. Res. Psychol. 12, 202–222. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2014.955224

Burgerlijk Wetboek Boek 3 (1992) Burgerlijk wetboek boek 3. Available at: https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0005291/2021-07-01 (Accessed 10 May 2022).

Canadian Veterinary Medical Association (2004). Canadian Veterinary oath (Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Veterinary Medical Association).

Carenzi C., Verga M. (2009). Animal welfare: review of the scientific concept and definition. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 8 (sup 1), 21–30. doi: 10.4081/ijas.2009.s1.21

Cholbi M. (2017). “The euthanasia of companion animals,” in Pets and people: The ethics of our relationships with companion animals. Ed. Overall C. (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 264–278.

Christiansen S., Kreistensen A., Lassen J., Sandøe P. (2015). Veterinarians’ role in clients’ decision-making regarding seriously ill companion animal patients. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica 58 (1), 1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13028-016-0211-x

Cooney K., Dickinson G. E., Hoffmann H. (2021). Euthanasia education in veterinary schools in the united states. J. Veterinary Med. Educ. 48 (6), 706–709. doi: 10.3138/jvme-2020-0050

Council on Animal Affairs (2019) The state of the animal in the netherlands. Available at: https://english.rda.nl/publications/publications/2020/08/05/the-state-of-the-animal-in-the-netherlands (Accessed 11 07 2022).

Council Regulation (EC) No 1099/2009 on the protection of animals at the time of killing (2009) Council regulation (ec) no 1099/2009 on the protection of animals at the time of killing. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ:L:2009:303:TOC (Accessed 10 May 2022).

Dickinson G. (2019). US And UK veterinary medicine schools: emphasis on end-of-life issues. Mortality 24 (1), 61–71. doi: 10.1080/13576275.2017.1396970

Dürnberger C. (2020a). Am I actually a veterinarian or an economist? understanding the moral challenges for farm veterinarians in Germany on the basis of a qualitative online survey. Res. Veterinary Sci. 133, 246–250. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2020.09.029

Dürnberger C. (2020b). I Would like to, but I can’t. an online survey on the moral challenges of German farm veterinarians. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 33 (3), 447–460. doi: 10.1007/s10806-020-09833-0

Edwards-Callaway L., Cramer M.C., Roman-Muniz I.N., Stallones L., Thompson S., Ennis S., et al. (2020). Preliminary exploration of swine veterinarian perspectives of on-farm euthanasia. Animals 10 (10), 1919. doi: 10.3390/ani10101919

Fawcett A. (2013). “Euthanasia and morally justifiable killing in a veterinary clinical context,” in Animal death. Eds. Johnston J., Probyn-Rapsey F. (Sydney: Sydney University Press), 205–220.

Federation of Veterinarians in Europe (2019) European Veterinary code of conduct. Available at: https://fve.org/cms/wp-content/uploads/FVE_Code_of_Conduct_2019_R1_WEB.pdf (Accessed 10 May 2022).

Fraser D. (2008). Understanding animal welfare. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica 50 (1), 1–7. doi: 10.1186/1751-0147-50-S1-S1

Fraser D., Weary D. (2004). “Quality of life for farm animals: linking science, ethics and animal welfare,” in The well-being of farm animals: challenges and solutions. Eds. Benson G., Rollin B. (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.), 39–60.

Guest G., Bunce A., Johnson L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? an experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18 (1), 59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903

Kasperbauer T., Sandøe P. (2015). “Killing as a welfare issue,” in The ethics of killing animals. Ed. Garner T.V. a. R. (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 17–31.

Kipperman B., Morris P., Rollin B. (2018). Ethical dilemmas encountered by small animal veterinarians: characterisation, responses, consequences and beliefs regarding euthanasia. Veterinary Rec. 182 (19), 548–548. doi: 10.1136/vr.104619

Koninklijke Nederlandse Maatschappij voor Diergeneeskunde (2010). Code voor de dierenarts (Houten, The Netherlands: KNMvD).

Lagoni L., Hetts S., Butler C. (1994). The human-animal bond and grief (Philadelphia: Pa.: W.B. Saunders Company).

Littlewood K., Beausoleil N., Stafford K., Stephens C. (2021). What would you do?”: how cat owners make end-of-life decisions and implications for veterinary-client interactions. Animals 11 (4), 1114. doi: 10.3390/ani11041114

McMahan J. (2002). The ethics of killing: Problems at the margins of life (New York: Oxford University Press).

Stassen E. N., Meijboom F. L. B. (2016). The End of Animal Life: A Start for Ethical Debate : Ethical and Societal Considerations on Killing Animals. Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen, The Netherlands. doi: 10.3920/978-90-8686-808-7

Mellor D., Beausoleil N.J., Littlewood K.E., McLean A.N., McGreevy P.D., Jones B., et al. (2020). The 2020 five domains model: Including human–animal interactions in assessments of animal welfare. Animals 10 (10), 1870. doi: 10.3390/ani10101870

Morgan C. A. (2009). “Veterinarians’ views regarding their professional role,” in Stepping up to the plate: animal welfare, veterinarians, and ethical conflicts. Ed. Morgan C. A. (Vancouver: University of British Columbia), 95–123.

Morgan C. A., McDonald M. (2007). Ethical dilemmas in veterinary medicine. Veterinary Clinics North America: Small Anim. Pract. 37 (1), 165–179. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2006.09.008

Morris P. (2012). Blue juice: euthanasia in veterinary medicine (Philadelphia: Temple University Press).

Moses L., Malowney M., Wesely Boyd J. (2018). Ethical conflict and moral distress in veterinary practice: A survey of north American veterinarians. J. veterinary Internal Med. 32 (6), 2115–2122. doi: 10.1111/jvim.15315

Ohl F., van der Staay F. (2012). Animal welfare: At the interface between science and society. Veterinary J. 192 (1), 13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2011.05.019

Polkinghorne D. (2005). Language and meaning: Data collection in qualitative research. J. Couns. Psychol. 52, 137–145. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.137

Regulation (EU) 2019/6 of the European Parliament and of the Council on veterinary medicinal products and repealing Directive 2001/82/EC (2018) Regulation (eu) 2019/6 of the european parliament and of the council on veterinary medicinal products and repealing directive 2001/82/ec. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32019R0006&from=EN (Accessed 11 07 2022).

Rollin B. (2006). An introduction to veterinary medical ethics: theory and cases. 2nd ed (Iowa: Iowa State University Press).

Rollin B. (2011a). Animal rights as a mainstream phenomenon. Animals 1 (1), 102–115. doi: 10.3390/ani1010102

Rollin B. (2011b). Euthanasia, moral stress, and chronic illness in veterinary medicine. Veterinary Clinics: Small Anim. Pract. 41 (3), 651–659. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2011.03.005

Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (2019). Code of professional conduct for veterinary surgeons (London: Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons).

Sandøe P., Corr S., Palmer C. (2016). “Treating sick animals and end-of-life issues,” in Companion animal ethics (New York, NY, USA: Wiley-Blackwell).

Shaw J., Lagoni L. (2007). End-of-life communication in veterinary medicine: delivering bad news and euthanasia decision making. Veterinary clinics: small Anim. Pract. 37 (1), 95–108. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2006.09.010

Stichting Geborgde Dierenarts (2022) Stichting geborgde dierenarts. Available at: https://www.geborgdedierenarts.nl/ (Accessed 11 07 2022).

Tucker Edmonds B., McKenzie F., Panoch J. E., White D. B., Barnato A. E. (2016). A pilot study of neonatologists’ decision-making roles in delivery room resuscitation counseling for periviable births. AJOB empirical bioethics 7 (3), 175–182. doi: 10.1080/23294515.2015.1085460

Wagner B. K., Cramer M. C., Fowler H. N., Varnell H. L., Dietsch A. M., Proudfoot K. L, et al. (2020). Determination of dairy cattle euthanasia criteria and analysis of barriers to humane euthanasia in the united states: The veterinarian perspective. Animals 10 (6), 1051. doi: 10.3390/ani10061051

Wet betreffende de euthanasie (2002) Wet betreffende de euthanasie. Available at: https://www.ejustice.just.fgov.be/cgi_loi/change_lg.pl?language=nl&la=N&cn=2002052837&table_name=wet (Accessed 10 May 2022).

Wet toetsing levensbeëindiging op verzoek en hulp bij zelfdoding (2021) Wet toetsing levensbeëindiging op verzoek en hulp bij zelfdoding. Available at: https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0012410/2021-10-01 (Accessed 10 May 2022).

White D. B., Malvar G., Karr J., Lo B., Curtis J. R. (2010). Expanding the paradigm of the physician’s role in surrogate decision-making: an empirically derived framework. Crit. Care Med. 38 (3), 743. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c58842

Yeates J. (2010). Ethical aspects of euthanasia of owned animals. Practice 32 (2), 71. doi: 10.1136/inp.c516

Keywords: end-of-life situations, euthanasia, farm animal veterinarians, qualitative research, veterinary medical ethics

Citation: Deelen E, Meijboom FLB, Tobias TJ, Koster F, Hesselink J-W and Rodenburg TB (2022) The views of farm animal veterinarians about their roles and responsibilities associated with on-farm end-of-life situations. Front. Anim. Sci. 3:949080. doi: 10.3389/fanim.2022.949080

Received: 20 May 2022; Accepted: 08 August 2022;

Published: 02 September 2022.

Edited by:

Irene Camerlink, Polish Academy of Sciences (PAN), PolandReviewed by:

Gabriela Olmos Antillón, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SwedenBarry Kipperman, University of California, Davis, United States

Christian Dürnberger, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, Austria

Copyright © 2022 Deelen, Meijboom, Tobias, Koster, Hesselink and Rodenburg. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ellen Deelen, ZS5kZWVsZW5AdXUubmw=

Ellen Deelen

Ellen Deelen Franck L. B. Meijboom

Franck L. B. Meijboom Tijs J. Tobias

Tijs J. Tobias Ferry Koster

Ferry Koster Jan-Willem Hesselink4

Jan-Willem Hesselink4 T. Bas Rodenburg

T. Bas Rodenburg